Abstract

A growing body of research indicates that the big five personality scale is the most widely used tool for assessing personality traits. Translating and validating this scale in different languages is important to understand personality across diverse cultures. However, there is a lack of a reliable tool to measure big five personality in the Ethiopian context. The overarching purpose of this study was to develop and validate a psychometrically robust Amharic version of the Big Five personality scale that is culturally appropriate for the Ethiopian context. This study employed a cross-sectional survey design to gather data from 476 university students (Female = 232 and Male = 244) who were randomly selected from Ambo University. To analyse the data, the entire sample was divided randomly into two equal-sized groups for exploratory factor analysis (EFA, N = 238) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA, N = 238). The findings from both EFA and CFA provided strong support for a Big Five Personality model (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) that displayed significant correlations. Furthermore, the Amharic version of the scale demonstrated improved compatibility with the collected data, exhibiting excellent psychometric properties in terms of content validity and construct validity and satisfactory internal consistency. In general, the findings suggest that the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale has the potential to be effectively utilized within the Amharic-speaking communities in Ethiopia. Thus, the Amharic version of the scale can be considered as a viable option for assessing personality traits in the specific cultural and linguistic context of Ethiopia.

Introduction

Research has consistently found that personality influences various aspects of peoples’ lives: their job performance (Judge et al., Citation2013), work engagement (Young et al., Citation2018), academic performance (Poropat, Citation2009), mental health (Strickhouser et al., Citation2017), life satisfaction (Anglim et al., Citation2020), adjustment (Ward et al., Citation2004), and intercultural competence (Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, Citation2013). Consequently, the development of theories, assessment tools and models of personality have attracted several scholars’ attention (Konstabel et al., Citation2012; Maalouf et al., Citation2022; Meng et al., Citation2021; Ward et al., Citation2004).

Personality is conceptualised as the relatively enduring patterns of thought, feeling, and behaviour that reflect the predisposition to respond in certain ways under certain circumstances (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992a; Roberts, Citation2009). Others also considered personality as a system of distinctive characteristics and developmentally dynamic procedures that influence psychological functioning of every individual (Goldberg, Citation1999). In general, personality can be understood as a series of individual attributes that are stable over time, gives subjects a sense of identity, integrity, and uniqueness, and provides them with a certain regularity in their behaviours (Caprara & Cervone, Citation2000; Robles-Haydar et al., Citation2022). Recognizing and considering personality is significant for knowing and directing people in their specific contexts. In this regard, one of the most influential, widely used and theoretically accepted model in the area of personality assessment is the Big Five Personality Scale (B5P), similarly known as the five-factor model (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992a; De Raad & Mlacic, Citation2015; Laros et al., Citation2018; McCrae, Citation2011; Oliveira, Citation2019).

The Big-Five Personality Model is the most widely adopted and a comprehensive model describing individual personality traits in terms of five factors; openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992b, John et al., Citation2008, Meng et al., Citation2021). The openness subscale reflects individuals’ intellectual curiosity, tolerance for divergent ideas and appreciation for arts (Simkin et al., Citation2012) while conscientiousness is related to impulse control and determination in goal achievement (Caprara et al., Citation1993). On the other hand, the extraversion dimension indicates the ability to make friends and experience positive emotions whereas agreeableness is related to empathy and warmth in interpersonal relationships (Caprara et al., Citation1993). The neuroticism dimension reflects the tendency to experience negative emotions (Cassaretto, Citation2009).

It should be noted that various personality scales [e.g., Costa and McCrae (Citation1992a) NEO personality Inventory (240-items), Costa and McCrae (Citation1992b) NEO-FFI (60-items), John and Srivastava (Citation1999) big five inventory (44-items)] have been developed and validated. However, these scales have large number of items that may expose respondents to negative reactions such as fatigue and boredom, refusal to respond to all items, and random response (Burisch, Citation1984). On the other hand, several scholars have recently developed shorter scales based on the big five personality model. These include: Rammstedt and John (Citation2007) 10-item scale, Donnellan et al. (Citation2006) 20-item scale, Gosling et al. (Citation2003) 10-item scale and Konstabel et al. (Citation2012) 30-item scale. Often these shortened personality scales have certain psychometric limitations with their internal consistency reliability and content validity (Crede et al., 2012; Konstabel et al., Citation2012). Besides, they lack the cross-cultural support that the long version previously enjoyed (Toyomoto et al., Citation2022). It should be noted that personality scales that are too long or too short have their own limitations (Zhang et al., Citation2019) and it is important to develop instruments that are neither too long nor too short.

In recent decades, there has been a significant increase in empirical research (e.g., Robles-Haydar et al., Citation2022; Veloso et al., 2021) focusing on instruments related to the measurement of Big Five Personality traits. This growing body of evidence has shed light on the development and advancement of these assessment tools. Certainly, given that an individual’s socially valued behaviours as well as maladaptive behaviours are influenced by their personality traits, the utilization of measures that assess this crucial parameter would prove highly beneficial in both personality-related research and intervention practices (Mezquita et al., Citation2019; Neslihan et al., Citation2010). Hence, Konstabel et al. (Citation2012) 30-item big five personality scale was adapted and validated for Ethiopian university students.

Based on the Big-Five Personality Model the majority of previous studies adapting this scale were conducted in English speaking communities. However, there is an increasing interest in other eco-cultural contexts to validate the scale. As empirical evidence has shown, the big five personality scale has been translated and adapted into numerous languages in different countries including Colombia (Robles-Haydar et al., Citation2022), China (Meng et al., Citation2021), Portugal (Oliveira, Citation2019), France (Combaluzier et al., Citation2016), Argentina (Cupani et al., Citation2020; Cupani & Ruarte, 2008), Brazil (Laros et al., Citation2018), Malaysia (Ong, 2014), Japan (Toyomoto et al., Citation2022), Spain (Mezquita et al., Citation2019) and Turkiye (Morsunbul, Citation2014; Neslihan et al., Citation2010). Although the scale has been extensively used in western and some Asian countries, we do not have an instrument which helps to measure big five personality traits of young adults in the Ethiopian context. Therefore, to comprehend young adults’ personality trait in the Ethiopian context, translating the Big Five Personality Scale to Amharic language and validating it for use in Ethiopia is essential. Moreover, the widely used Big Five Personality Scale was developed and validated in Western countries where the individualistic cultural and theoretical orientation is dominant.

On the other hand, studies conducted in some non-western countries have developed personality scales customized to their eco-cultural context (Cheung et al., Citation1996; Wang & Cui, Citation2004), whereas others have used the existing scale without first validating it for local use. Still others have modified the scale developed in western countries and validated it for use in their context (Yao & Liang, Citation2010; Zheng et al., Citation2008). Even though, most versions of the Big Five Personality Scale have returned similar factor structure and high internal consistencies, some language validations, expressly, those from developing communities like Ethiopia, have either failed to support the Big Five personality structure, or have had to undergo substantial amendments of the scale items in order to achieve suitable fit and reasonable stability and reliability results.

While some non-western studies (e.g., Laros et al., Citation2018; Namikawa et al., Citation2012; Oliveira, Citation2019) managed to maintain a comparable factor structure to the original Big Five Personality Scale, they faced criticism due to low factor loadings, low factor correlations, and low reliability coefficients. Because of cultural variations between young adult university students across cultures and/or countries, varied measures of Big Five Personality Scale that narrow eco-cultural differences are needed. This points to the need for developing a new scale or adapting an already existing scale that best fits the Ethiopian context. Therefore, validating an Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale will play significant role in tapering the gap in the measurement of the big five personality in Ethiopia because such measure does not exist in Ethiopia to the best of our knowledge. Translating the big five personality scale to Amharic language and validating it for use in the Ethiopian context is of paramount importance for several reasons. First and foremost, such a study will narrow the gap mentioned above regarding the absence of any scale developed or adapted and validated for use in the Ethiopian context. Second, validating the big five personality scale in the Ethiopian context will also provide further evidence as to whether the Big Five Personality has cross-cultural validity. Third, this study can also provide evidence as to whether the Big Five Personality Model can be useful to study personality in Ethiopia where communities are dominantly collectivist rather than individualistic.

Moreover, this study can serve as a stepping stone in adapting a culturally suitable measure in the area of personality for future researchers in the Ethiopian context. Hence, the purpose of the present study is to translate and validate the Amharic version of Konstabel et al. (Citation2012) Big Five Personality Scale for use with university students in the Ethiopian context. This particular instrument was selected for several reasons. Firstly, it was recently identified as a highly suitable option for constructing a comprehensive personality scale. It strikes a balance between being neither too short nor too long, making it an ideal choice. Secondly, when the instrument was tested in four different languages (Estonian, Finnish, English, and German), its principal component structure closely resembled that of its original longer version. This indicates that the instrument’s underlying structure is consistent across different languages. Lastly, the instrument demonstrated strong internal consistency across all four languages, with reliability coefficients exceeding .89. In summary, these factors make the instrument a reliable and effective tool for measuring personality traits and adapting to Ethiopian context.

More specifically, the study has the following objectives:

To translate the original Big Five Personality Scale, English version (30-items) into Amharic language,

To examine the psychometric properties (i.e., content validity, factor structure, fitness indices, construct validity and internal consistency) of the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale in a sample of Ethiopian university students.

Method

Study design

In the current validation study, a cross-sectional research design was employed to collect, analyse, and interpret the data. This design was chosen because it allows researchers to gather data from a selected population at a specific point in time.

Participants

The target population of the present study was 3rd year and above students at Ambo University. Ambo University is located in Ambo town, 114 kilometres west of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia with a student population of about 18,458 (M = 10,182 and F = 8,276). The students in this university are highly diversified in terms of ethnicity and religious affiliation. Sample size was determined based on the assumptions of factor analysis (i.e., EFA & CFA). For the purpose of instrument validation, various scholars (e.g., Bell, Citation2010; Comrey & Lee, Citation1992; Hair et al., Citation2006a; Citation2014) suggested that the minimum sample has to have participants at least five times the observed number of variables (5:1 ratio) being analysed. Assuming that larger sample size is better, 8:1 ratio was considered. Hence, students who met the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate; a) domestic university students, b) those students who are currently enrolled in 3rd year (or above) undergraduate regular programme and c) and those who are willing to participate.

Consequently, to ensure representative of the sample 550 participants (M = 283 and F = 267) were recruited from Ambo University using stratified random sampling techniques. However, the final data analysis was conducted only for 476 (M = 244 and Fe = 232 aged between 18 to 30 years (mean age= 22.35 and SD = 2.989) accounting about 86.55% of the participants who appropriately and correctly responded to all items. The reason for using stratified random sampling method was to ensure proportional representation of students in terms of their sex and department. Out of the 476 selected, the majority of the study participants belongs to the Oromo ethnic group (n = 189, 39.7%) followed by Amhara (n = 157, 33.0%), Sidama (n = 30, 6.3%), Tigre (n = 23, 4.6%) and others (n = 77, 16.18%). In relation to the respondents’ religion a large number of participants are Orthodox Christians (n = 203, 42.6%) followed by Protestant Christians (n = 186, 39.1%) and Muslims (n = 74, 15.5%). In contrast, a considerably larger proportion of the study participants (n = 379, 79.4%) came from households with married biological parents, indicating an intact family structure. Conversely, approximately one-fifth of the students (n = 98, 20.6%) belonged to family units that did not include two married biological parents, indicating a non-intact family structure.

Instrument

The present validation study instrument involves two parts. The first section includes items that ask for participants’ demographic characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity, religions, language, family structure, and department. In the second part, items of Konstable et al.’s (2012) short version Big Five Personality Scale (30- items) were presented. This scale was conceptualized in five different characteristics of person’s personality and each item rated on a 5- point scale (ranging from 1= Strong Disagreement to 5= Strong Agreement). These are: Openness (6 items) - an appreciation for and willingness to engage with new experience and ideas(e.g., I love novelty and variety), conscientiousness (6- items)- a tendency toward organization and thoughtfulness(e.g., I want everything to be in its right place), Extraversion (6- items) - an outward focused and tendency toward being outgoing(e.g., I crave new experiences and excitement), Agreeableness (6-items)- a general attitude of compassion, caring, and cooperation with others(e.g., I am honest and sincere in every situation), and Neuroticism (6-items)- inclination toward anxiety, moodiness, and preoccupation(e.g., I do things that I regret later). We adapted this scale into the Ethiopian context because it is short and easy to understand by the respondents.

To determine individuals’ dominant personality traits, their mean scores were calculated across the five subscales: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. This provided insights into their overall character and behavioural patterns. Scoring high in each subscale indicates a predisposition towards the corresponding Big Five Personality type. It is important to recognize that individuals may possess more than one type of personality simultaneously, allowing for the possibility of multiple dominant traits. The short (30-item) version of Big Five Personality Scale is appropriate for university students, who are in a developmental period otherwise known as young adulthood/late adolescence. The original version of the instrument validated with Estonian, Finland, English and German youth has very good reliability (i.e., [Openness, α = 0.79], [conscientiousness, α = 0.82], [extraversion α = 0.84], [agreeableness, α = 0.74], and [neuroticism, α = 0.87]) and criterion, convergent and discriminant validity results.

Procedures

During instrument translation and data collection appropriate procedures were followed. First, content validity of the original English version of the scale was assessed with a group of eight experts following the suggestion of Lawshe (Citation1975). The content validity assessment results showed that among the 30 items of the big five personality scale all items have a content validity ratio (CVR) score over the acceptable threshold (i.e., 0.75) with 0.93 content validity index (CVI). Finally, based on the comments and suggestions forwarded by the group of experts essential modifications were made and all 30 items of the scale were retained.

Second, following content validity assessment the translation of the measures from its original English version into Amharic language was carried out by language experts. Translation of the scale from the source language to Amharic was executed through the forward and backward translation protocol recommended by various scholars (e.g., Guillemin et al., Citation1993; ITC, Citation2010). Based on these, two independent bilingual professionals (for whom Amharic is their mother tongue and who are proficient in English) translated the questionnaires into Amharic language (forward translation). In order to retain a single Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale, with the mediator of the first author, a reconciliation meeting was conducted by the two forward translators. In this meeting, the two forward translators with the mediator of the first author came together and carried out a sentence by sentence revision and comparison of the items which resulted in a single agreed on forward translated scale. Then, to ensure the semantic equivalence of the Amharic version with the English version, backward translation was done by a single independent bilingual (Amharic native speaker and proficient in English) professional who did not know about the original version of the scale. We found no significant difference between the backward translated and the original versions, demonstrating that the translated items had very similar meanings as the items in the original English version.

Third, pre-testing of the translated instrument was done with 20 Amharic speaking students of Ambo University. In the cognitive debriefing process, participants were asked to give their general impression/understanding on the clarity of the items, the relevance of the content to their context, the comprehensiveness of the instruction, and the capability to fill it on their own pace. Accordingly, anything judged as unclear were assessed, evaluated and modified by the experts and further psychometric tests were computed See items of both the original and the Amharic versions of the scale in Appendix A (supplementary materials).

Lastly, support letter was secured from the School of Psychology, Addis Ababa University and presented to Ambo University detailing the first author’s identity, title and purpose of the study. After reviewing the letter of support, director of the research ethical review Board of Ambo University gave permission to conduct the study. Hence, target participants were identified and oriented about the purpose of the study, and then we requested their verbal consent. Once we secured their informed verbal consent, they were given orientation as to how to fill in the questionnaire. Then the scale was distributed to each participant. Upon the respondent’s completion of the self-administered questionnaire, the completed copies of the scale were collected and checked to see if they were properly completed.

Methods of data analysis

Data analysis was done using IBM SPSS 26.0 with AMOS. To identify the underlying factorial structure, nature of relationship between factors and the fitness of the model to the data a two-step method [i.e., exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)] was used. Before data analysis, evaluation of data accuracy was done via randomly selected input of 20% of the total copies of the questionnaire and all are judged good. With regard to EFA, the following criteria were used; eigenvalue (≥1), explained variance (≥ 60%), KMO (>0.60), Bartlett’s test of Sphericity (P < 0.05), factor loadings (>0.40), factor correlation matrix (>0.30) and the theoretical five-factor model. Further, actual eigenvalues > criteria values from Monte Carlo PCA for Parallel analysis and exclusion of cross loading items >0.40 in at least two factors were used as criteria. In the present study, due to the assumption of factorial independence we used principal component extraction method with varimax rotation.

For CFA, absolute and incremental fit indices indicators with maximum likelihood (ML) method were used. Accordingly, the model was evaluated through goodness of fit indices indicators. These fit indices and their cut-off values were; CMIN/DF (<5), AGFI (>0.90), GFI (>0.09), NFI (>0.90), CFI (>0.90) and RMSEA (<0.08). However, based on the assumption that both alternative fit indices and the commonly used fit indices adequately capture the desired aspects of model fit, we have chosen to exclude the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) from our data analysis. According to Hair et al. (Citation2006a), if any 3 – 4 of the Goodness-of-Fit indices are within the threshold, then fitness of the entire model is regarded as acceptable. On the other hand, convergent validity of the scale was evaluated via comparing the values of composite reliability (CR) with the values of average variance extracted (AVE). The discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the average variance extracted (AVE) with the values of the maximum shared squared variance (MSV) and average shared squared variance (ASV). Also discriminant validity was estimated by the square root of the average variance extracted for each subscale with the correlation coefficients of other subscales. Reliability analysis was done using cronbach’s alpha value, in which, α > 0.7 is suitable and verified that the items are adequate enough in assessing the constructs of the scales. Finally, the total sample (N = 476) was randomly split into two equal-sized groups, to use one for EFA (n = 238) and the other for CFA (n = 238), in which, EFA was computed with the first half-sample followed by CFA with the second half sample. The subsamples did not significantly differ in terms of age, gender, ethnic composition, religious affiliation or study discipline.

Results

In the present validation study data were collected from 476 (Female= 232 and male = 244) randomly selected Ambo University students, who properly and fully completed all items in the scale. The mean age of the study participants was 22.35 years with a standard deviation of 2.989 ().

Table 1. Summary of sampled study participants’ demographic characteristics (N = 476).

Results of the exploratory factor analysis

Before running EFA, its assumptions (i.e., correlation matrix, sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity) were checked. Accordingly inspection of the correlation matrix indicated that most of the items coefficients were ≥ 0.3. The result of KMO was = 0.844, exceeding the minimum threshold values of 0.60 and verifying that the sample size used in this study was adequate for exploratory factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 4094.781, df = 435, p < 0.001) where it supported the factorability of the correlation matrix.

EFA was computed using principal component analysis and Varimax rotation with Kaisar normalization in which absolute value of standardized factor loading > 0.40 was set to run factor extraction. Initially, this analysis showed a total of eight (8) factor structures with Eigen values above 1.00 and total variance explained 58.16%. However, examination of scree plot and Monte Carlo PCA for Parallel that could compare the actual eigenvalues with its corresponding criterion values showed five (5) factor solutions accounting for 47.46% of the total variance. In this regard, factor 1 (Extraversion) accounted for 20.107%, factor 2 (Neuroticism) 11.144%, Factor 3 (Conscientiousness) 6.696%, factor 4 (Openness) 5.413% and factor 5 (Agreeableness) 4.102%.

As shown in below, the rotation solution revealed the presence of five structures with a number of strong loading and all items were substantially loading on only one factor. Accordingly, factor 1 (Extraversion) includes items 9, 8, 11, 7, 13, 10 and 12. Factor 2 (Neuroticism) includes items 4, 3, 2, 5, 1 and 6. Factor 3 (Conscientiousness) includes items 27, 28, 25, 29, 26, 24, and 30. Factor 4 (Openness) includes items 20, 16, 18, 17, 19, 14, and 15 while factor 5 (Agreeableness) includes items 22, 23, and 21. This verified that a five factor solution derived from the total variance explained was the best component for the big five personality scale (Amharic version) in the Ethiopian context.

Table 2. Rotated results of the EFA on the Amharic version of the big five personality scale.

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis

Following the EFA, CFA was computed on the data collected from the second half sample (n = 238). Furthermore, the basic assumptions of CFA were checked for each scale and were found to be tenable. In this regard, the factor structure of the Big Five Personality Scale (Amharic version) retained was evaluated with CFA via robust estimation methods and maximum likelihood evaluation of model fit indices. Fit was examined via widely used practical indices recommended by several scholars (e.g., Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013, Byrne, Citation2006, Hair eta al., Citation2006a). These include and should be the chi-square (CMIN < 5), the goodness of fit index (GFI > 0.90), the adjusted goodness of fit (AGFI > 0.90), the normed fit index (NFI > 0.90), the comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08).

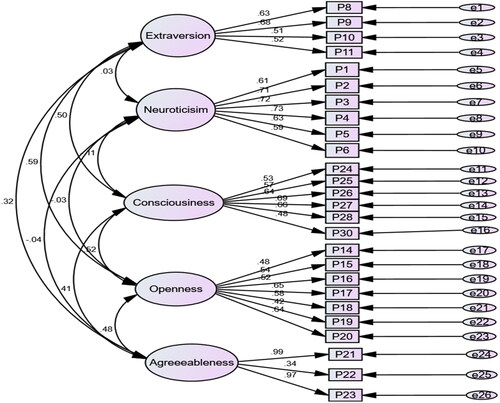

Evidence obtained in our study revealed that the fit indices of the initial Amharic version big five personality scale was done on 30 items, with χ2 (CMIN) = 981.912, CMIN/DF = 2.486, GFI= .883, AGFI=.862, CFI=.881 and RMSEA=.056. In this initial model all fit indices except CMIN/DF and RMSEA did not meet the model fit criteria (see below). This indicated that refinement of the model was required to bring the model indices to an acceptable level. Hence, four items (P7, P12, P13 and P29) with low factor loadings and having large standardized residual covariance (>2.58) with other items were deleted from the model (). Hence, the modified Big Five Personality Scale (Amharic version) with 26 items better fit the data. This verified that the big five personality scale (Amharic version) with 26 items best fits the purpose of measuring personality of Ethiopian young adult university students

Table 3. Result of CFA for the original and refined Amharic version Big Five Personality Scale.

Below is the figure of the refined confirmatory factor analysis results of the Amharic version big five personality scale – Amharic version (with 26 items).

Convergent and discriminant validity

As displayed in , convergent and discriminant validity of the big five personality scale (Amharic version) was evaluated. With regard to convergent validity, average variance explained (AVE) is higher than 0.5. Additionally, all composite reliability (CR) values of the five-factor model were found to be higher than 0.7. The value of CR of each factor was greater than the values of AVE. This implies that the big five personality scale (Amharic version) has good convergent validity. With respect to discriminant validity of the scale, the values of AVE for all big five factors were higher than the values of MSV and ASV. Moreover, the square root of AVE of each of the five factors (or dimensions) was found to be greater than the correlation coefficient with the other dimensions. This shows that the model has good construct validity (see ).

Table 4. Convergent and Discriminant Validity of the Scale using CR, AVE, MSV, ASV, Square Root of AVE and the Correlation between the Big Five Personality Subscales-Amharic Version.

Reliability of the Big Five Personality Scale – Amharic version

below displays the Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the big five personality subscales or dimensions (Amharic version). The results show that the Cronbach alpha coefficients for all five subscales or dimensions are above the acceptable threshold value (>0.70). The estimated internal consistency for the Big Five Personality Scale – Amharic version were; extraversion (α=.832), neuroticism (α=.865), conscientiousness (α=.863), openness (α = 885), and agreeableness (α = 772). This attests that the big five personality scale – Amharic version has very good and acceptable internal consistency in the Ethiopian context.

Table 5. Reliability coefficient for the Big Five Personality Scale (Amharic version) after EFA and CFA.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to translate Konstable et al.’s (2012) Big Five Personality (30-item) Scale to Amharic and validate it for use with Ethiopian emerging adults at Ambo University. The present study is unique in its endeavour to compare and contrast the psychometric properties of the 30-item Big Five Personality Scale in a distinct eco-cultural context. The EFA outcome demonstrated that each of the 30 items in the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale exhibited robust loading, surpassing the threshold of 0.54. The loadings indicate a substantial and meaningful relationship between each item and its underlying factor. The results of the study confirmed that the five-factor solution (extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, openness, and agreeableness) derived from the total variance explained was replicated effectively within the Ethiopian eco-cultural context. This suggests that the Big Five Personality Model, as represented by these five factors, is relevant and meaningful in understanding personality traits among individuals in Ethiopia. The replication of these factors in the Ethiopian context provides support for the cross-cultural applicability of the Big Five Personality model. This supports the theoretical robustness of the five-factor structure of the Big Five personality model, similar to the original version proposed by Konstable et al. (2012) and further supported by Alhosin and Abdul (Citation2018).

The findings of this study are consistent with multiple pieces of evidence obtained in various settings as demonstrated by João (2017), Toyomoto et al. (Citation2022), and Veloso (2021). Despite variations in the number of items within each construct across different cultures, the findings of this study remained consistent with other research conducted elsewhere (Carciofo et al., Citation2016; De Bruin et al., Citation2022; Harrun et al., Citation2023). The differences in the number of items may be attributed to eco-cultural differences, sample characteristics, and/or disparities in translation.

The initial findings from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which were confirmed through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), did not yield satisfactory fit indices for the Amharic version of the Big Five personality scale. This finding is not surprising, as previous studies (Harrun et al., Citation2023; Hopwood & Donnellan, Citation2010) have consistently shown that the big five personality model does not fare well when assessed using confirmatory factor analysis. To put it differently, these studies have consistently found that the Big Five Personality Scale does not demonstrate strong support when subjected to confirmatory factor analysis. To improve the model, we employed a robust ML alternative approach to refine it. In this process, we identified four items (P7, P12, P13, and P29) that exhibited low factor loadings and high standardized residual covariance (>2.58) with other items. Further, it was observed that these four items exhibited poor psychometric properties (i.e., low item-total correlations, low reliability and low factor loading). This implies that these items were not adequately measuring the intended constructs of the personality scale in the Amharic speaking communities. Hence, to improve the overall psychometric properties of the Amharic version and enhance its accuracy in measuring the five personality traits these four items were removed from the analysis. After removing the four identified items, the fit indices of the model indicated a strong correspondence between the hypothesized model and the collected data. This is evidenced by the improved fit indices, as presented in , which demonstrated a close alignment between the proposed model and the observed data.

Although the removal of the four items led to improvements in the five theoretical factors of the Big Five Personality Scale, it is important to note that the findings of the present study suggest that the original structure of the big five personality scale in English did not yield similar results. These findings suggest that the 26-item Amharic version of the big five personality scale has demonstrated appropriate structural validity within the Ethiopian context. In other words, the adapted version of the scale has shown to be valid and reliable for assessing personality traits in the Ethiopian youth population. The slight differences observed in the current study may be attributed to the fact that certain items within similar scales can elicit different responses in different languages. This phenomenon has been noted in various previous studies (Garrashi et al., Citation2022, Citation2023; Gurven et al., Citation2013; Laajaj et al., Citation2019; Takawira & Renier, Citation2023). These studies have highlighted the impact of language on individuals’ interpretation and response to specific items, which can contribute to variations in measurement outcomes across different linguistic and cultural contexts. Because the original version of the CFA was not utilized in our study, we are unable to make direct comparisons between the fit indices of our research and those of previous studies. In other words, we cannot assess how well our model fits the data in relation to the models used in earlier investigations.

However, our findings were consistent with previous research conducted in diverse contexts, supporting the existence of a Five-Factor Structure. This congruence was observed in many studies (e.g., Carciofo et al., Citation2016; De Bruin et al., Citation2022; Harrun et al., Citation2023). These findings provide evidence for the robustness of the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale for use with university students in Ethiopia. Furthermore, the findings of the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the collected data strongly supported the hypothesized model, indicating excellent convergent and discriminant validity. Additionally, an assessment of the internal consistency of the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale revealed high levels of reliability across all factors, falling within a very good and acceptable range. Although the values of internal consistency are sensitive to the number of items, the reliability values of the present study were consistent with various earlier studies (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Oliveira, Citation2019).

By and large, the results of this study provide additional evidence for the short Five-Factor Personality Scales proposed by Konstable et al. (2012) and their potential use in diverse cultural contexts. Despite being one of the most prominent and extensively studied models in personality research, the Big Five Personality Scale has not been adapted or explored within the context of Ethiopia in general and the Amharic speaking communities in particular. In Ethiopia, despite the lack of extensive prior research on the Big Five Personality Scale, there has been a significant upsurge in interest to adapt or develop scales linked to this model. The researchers recognized that their study marked the first endeavour to validate the Big Five Personality Scale specifically for Ethiopian university students and demonstrate encouraging positive psychometric properties that support the suitability of this instrument within the Ethiopian eco-cultural context. This study effectively validated the Western individualized-oriented Big Five personality Scale for Ethiopian youth, providing evidence for its applicability in the Ethiopian context.

It is important to acknowledge that this study has certain limitations. A notable limitation of this study was that the respondents were exclusively youth from a single public university, making it challenging to generalize the findings to the entire population of Ethiopian youth. Therefore, future studies should aim to include participants from various public and private universities in Ethiopia. This broader sample would likely yield more robust psychometric properties for the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale.

Conclusion and recommendation

Although there are some limitations to the study, the results revealed that the Amharic version of the Big Five Personality Scale with its five-factor structure was valid and reliable for use with Ethiopian university students. Besides, the results of this study confirmed that the Big Five Personality Scale (Amharic version) has a very good construct validity, convergent validity and internal consistency. Therefore, the 26-item Big Five Personality Scale (Amharic version) upholds very good psychometric properties and best fit to the data, which lead to the conclusion that it is a valid tool measuring personality traits of Ethiopian university students. Based on the findings of this study, it is crucial to emphasize the validation of the Big Five personality Model in a new cultural context. Furthermore, in this era of accelerated cultural diversity and the virtual age, it is imperative to emphasize that the use and significance of instruments like the Big Five Personality Scale cannot be overstated. Therefore, in order to develop a comprehensive and robust Big Five Personality Scale, it is necessary to conduct additional studies in different socio-cultural contexts.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ambo University, Institute of Education and Behavioural Study and Department of Psychology (Ref. no. AU/Psy/Eth Co/011/2022). All participants voluntarily participated in the study and provide verbal informed consent.

Supportive material.docx

Download MS Word (29.6 KB)Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to all individuals who directly and indirectly contributed to the completion of this study.

Data availability

The dataset produced and evaluated in this research can be obtained upon reasonable inquiry from the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

The authors stated that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose in relation to this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tessema Amente

Tessema Amente is a doctoral candidate at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, specialising in applied developmental psychology. He has authored more than six publications that have stimulated additional research in the domains of behavioural sciences, psychology, and education. His areas of interest in research are family dynamics, child developmental disorders, intercultural intelligence, teenage personality development, and the factors that influence these areas. Tessema is well-known in Ethiopia for giving internally displaced communities and returnees training in life skills, psychological first aid, and mental health. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Seleshi Zeleke

Seleshi Zeleke is an Associate Professor in the School of Psychology, Addis Ababa University. His research interests are in the areas of Educational Psychology (e.g., students’ academic achievement, student assessment, parenting styles, mathematical cognition, etc.) and Special Needs Education (e.g., developmental disability, inclusive education, etc.). He has produced many research reports, a book chapter and more than 20 journal articles. E-mail: [email protected]

References

- Ahmed, M. Abdel-Khalek, Jerome, Carson., Aayshiya, Patel., & Aishath, Shahama. (2022). The Big Five Personality Traits as predictors of life satisfaction in Egyptian college students. Nordic Psychology, 75(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2022.2065341

- Alhison, A. O., & Abdullah, A. H. (2018). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Big Five Personality Factors (CFA-BFPF). British Journal of Education, Learning and Development Psychology, 1(1), 29–36. www.abjournals.org

- Anglim, J., Horwood, S., Smillie, L., Marrero, R., & Wood, J. (2020). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 279–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000226

- Bell, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modelling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar- Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioural research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Burisch, M. (1984). Approaches to personality inventory construction: a comparison of merits. American Psychologist, 39(3), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.3.214

- Byrne, B. (2006). Structural equation modelling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Perugini, M. (1993). The “big five questionnaire”; A new questionnaire to assess the five factor model. Personality and Individual Differences, 15(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90218-r

- Caprara, G. V., & Cervone, D. (2000). Personality: Determinants, dynamics, and potentials. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812767

- Carciofo, R., Yang, J., Song, N., Du, F., & Zhang, K. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of Chinese language 44-item and 10-item Big Five personality inventories, including correlations with chronotype, mindfulness and mind wandering. PloS One, 11(2), e0149963. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149963

- Cassaretto, M. (2009). Relación entre las cinco grandes dimensiones de la personalidad y el afrontamiento en estudiantes pre-universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Universidad Nacional Mayor De.

- Cheung, F., Leung, K., Fan, R., Song, W.-Z., Zhang, J., & Zhang, J.-P. (1996). Development of the Chinese personality assessment inventory (CPAI). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022196272003

- Combaluzier, S., Gouvernet, B., Menant, F., & Rezrazim, A. (2016). Validation d’une version franc, aise dela Forme brève de l’inventaire des troubles dela personnalité pour le DSM-5 (PID-5 BF) de Krueger. Encéphale. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2016.07.006

- Comrey Andrew, L., & Lee, Howard, B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. Psychology in Press. P(1-442). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315827506.

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. (1992b). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory. Psychological Assessment Resources. Differ, 35, 1285–1292.

- Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1992a). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(6), 653–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I

- Credé, M., Harms, P., Niehorster, S., & Gaye-Valentine, A. (2012). An evaluation of the consequences of using short measures of the Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 874–888. PMID: 22352328. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027403

- Cupani, M., Morán, V. E., Ghío, F. B., Azpilicueta, A. E., & Garrido, S. J. (2020). Psychometric Evaluation of the Big Five Questionnaire for Children (BFQ-C): A Rasch Model Approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(9), 2472–2486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01752-y

- De Bruin, G. P., Taylor, N., & Zanfirescu, ȘA. (2022). Measuring the Big Five personality factors in South African adolescents: Psychometric properties of the Basic Traits Inventory. African Journal of Psychological Assessment, 4(0), a85. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajopa.v4i0.85

- De Raad, B., & Mlacic, B. (2015). The lexical foundation of the big five factor model. In T. Widiger (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the five factor model. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199352487.013.12

- Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

- Garrashi, H. H., Barelds, D. P. H., & De Raad, B. (2023). A psychometric evaluation of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) in an Eastern Africa population. Measurement Instruments for the Social Sciences, 5, e11207. https://doi.org/10.5964/miss.11207

- Garrashi, H. H., De Raad, B., & Barelds, D. P. H. (2022). Personality in Swahili culture: A psycholexical approach to trait structure in a language deprived of typical trait descriptive adjectives [Manuscript in Press].

- Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. De Fruyt, & F. Ostendorf (Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe (vol. 7, pp. 7–28). Tilburg University Press.

- Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

- Guillemin, F., Bombardier, C., & Beaton, D. (1993). Cross cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 46(12), 1417–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n

- Gurven, M., von Rueden, C., Massenkoff, M., Kaplan, H., & Vie, M. L. (2013). How universal is the Big Five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030841

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson New. International edition.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Structural equation modelling: An introduction, multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Harrun, H., Garrashi, Dick, P. H., Barelds., & B., De Raad. (2023). A Psychometric Evaluation of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) in an Eastern Africa Population. Measurement instrument for social science. Psych Open GOLD, 5, e11207. https://doi.org/10.5964/miss.11207

- Hopwood, C. J., & Donnellan, M. B. (2010). How should the internal structure of personality inventories be evaluated? Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 14(3), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310361240

- International Test Commission. (2010). International Test Commission guidelines for translating and adapting tests. Recuperadoem 24 julho 2018, de http://www. intestcom.org/upload/sitefi les/40.pdf

- John, O., Naumann, L., & Soto, C. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). The Guilford Press.

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five Trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). Guilford Press.

- Judge, T. A., Rodell, J. B., Klinger, R. L., Simon, L. S., & Crawford, E. R. (2013). Hierarchical representations of the five-factor model of personality in predicting job performance: integrating three organizing frameworks with two theoretical perspectives. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 875–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033901

- Konstabel, K., Lönnqvist, J., Walkowitz, G., Konstabel, K., & Verkasalo, M. (2012). The ‘Short Five’ (S5); Measuring Personality Traits using Comprehensive Single Items. European Journal of Personality, 26(1)·, 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.813

- Laajaj, R., Macours, K., Hernandez, D. A. P., Arias, O., Gosling, S. D., Potter, J., Rubio-Codina, M., & Vakis, R. (2019). Challenges to capture the big five personality traits in non-weird populations. Science Advances, 5(7), eaaw5226. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw5226

- Laros, J. A., Peres, A. J., de Andrade, J. M., & Passos, M. F. (2018). Validity evidence of two short scales measuring the Big Five personality factors. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 31(32). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-018-0111-2

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

- Maalouf, E., Hallit, S., & Obeid, S. (2022). Personality traits and quality of life among Lebanese medical students: any mediating effect of emotional intelligence? A path analysis approach. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00739-2

- McCrae, R. R. (2011). Personality theories for the 21st century. Teaching of Psychology, 38(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311411785

- Meng, Y., Yu, B., Li, C., & Lan, Y. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the organization big five scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 781369. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781369

- Mezquita, L., Bravo, A. J, Morizot, J., Pilatti, A., Pearson, M. R, Ibáñez, M. I, & Ortet, G. (2019) Cross-cultural examination of the Big Five Personality Trait Short Questionnaire: Measurement invariance testing and associations with mental health. PLoS ONE 14(12): e0226223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226223

- Morsunbul, U. (2014). The validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of Quick Big Five Personality Test. The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 27(4), 316–322.

- Namikawa, T., Tani, I., Wakita, T., Kumagai, R., Nakane, A., & Noguchi, H. (2012). Development of a short form of the Japanese big- five scale, and a test of its reliability and validity. Shinrigaku kenkyu: The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 83(2), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.83.91

- Neslihan, G. K., Turk, D., & Aysel, E. C. (2010). A study to adapt the big five inventory to Turkish. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2(2010), 2357–2359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.336

- Oliveira, J. P. (2019). Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the mini-IPIP five-factor model personality scale. Journal of Current Psychology, 38(2), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9625-5

- Onge, C. H. (2014). Validity and reliability of the big five personality traits scale in Malaysia. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 5(4), 309–333.

- Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

- Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

- Roberts, B. W. (2009). Back to the future: personality and assessment and personality development. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.015

- Robles-Haydar, C. A., Amar-Amar, J., & Martínez-González, M. B. (2022). Validation of the Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ-C), short version, in Colombian adolescents. Salud Mental, 45(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2022.00

- Simkin, H., Etchezahar, E., & Ungaretti, J. (2012). Personalidady Autoestima desde el Modeloy lateoría delos Cinco Factores. Hologramática, 7(17), 171–193. Retrieved from http://psicologiasocial.sociales.uba.ar/wp-content/.

- Strickhouser, J. E., Zell, E., & Krizan, Z. (2017). Does personality predict health and well-being? A meta synthesis. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 36(8), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000475

- Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Takawira, M. N., & Renier, S. (2023). The cross-cultural structural validity of the big five personality inventory (BFI-10) in a South African sample. African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.51415/ajims.v5i1.1028

- Toyomoto, R., Sakata, M., Yoshida, K., Luo, Y., Nakagami, Y., Iwami, T., Aoki, S., Irie, T., Sakano, Y., Suga, H., Sumi, M., Ichikawa, H., Watanabe, T., Tajika, A., Uwatoko, T., Sahker, E., & Furukawa, T. A. (2022). Validation of the Japanese big five scale short form in a university student sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 862646. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.862646

- Van der Zee, K., & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2013). Culture shock or challenge? The role of personality as a determinant of intercultural competence. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(6), 928–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113493138

- Veloso Gouveia, V., de Carvalho Rodrigues Araújo, R., Vasconcelos de Oliveira, I. C., Pereira Gonçalves, M., Milfont, T., Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., Santos, W., De Medeiros, E. D., Silva Soares, A. K., Pereira Monteiro, R., Moura de Andrade, J., Medeiros Cavalcanti, T., Da Silva Nascimento, B., & Gouveia, R. (2021). A short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-20): Evidence on construct validity. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 55(1), e1312. https://doi.org/10.30849/ripijp.v55i1.1312

- Wang, D., & Cui, H. (2004). Reliabilities and validities of the Chinese personality scale. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 36, 347–358.

- Ward, C., Leong, C., & Low, M. (2004). Personality and sojourner adjustment an exploration of the big five and the cultural fit proposition. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022103260719

- Yao, R., & Liang, L. (2010). Analysis of the application of simplified neo-ffi to undergraduates. Chin. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18, 457–459. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2010.04.024

- Young, H., Glerum, D., Wang, W., & Joseph, D. (2018). Who are the most engaged at work? A meta-analysis of personality and employee engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1330–1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2303

- Zhang, X., Wang, M.-C., He, L., Jie, L., & Deng, J. (2019). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory-15. PloS One, 14(8), e0221621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221621

- Zheng, L., Goldberg, L. R., Zheng, Y., Zhao, Y., Tang, Y., & Liu, L. (2008). Reliability and concurrent validation of the IPIP big-five factor markers in China: Consistencies in factor structure between internet-obtained heterosexual and homosexual samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(7), 649–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.07.009.