Abstract

The urban landscape and the image of the city by which the observers judge about a city remain as the mental image of a city in the mind of a man The urban landscape is capable of depicting the historical events of urban society. The favorable urban landscape has always been different from different people’s perspectives and the use of different approaches to summarize the perspectives of people in a practical and correct way has always been a concern of researchers in this field. This study attempted to explain the ideas and perspectives of the target population (including university professors, experts, consulting engineers, and urban managers) using the differential semantics technique. In so doing, a qualitative research design was used to explore the features of an appropriate urban landscape for the city of Tehran through differential semantics. The questionnaire was designed based on three main dimensions: evaluative, power, and activity, which were measured on a seven-point differential semantics scale. The participants were asked to select the images which are closest to the urban landscape of Tehran. Results showed that two pictures were selected as the ideal landscape of Tehran in the future.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Urban environments are determinants of the health of residents. Under such circumstances, the adoption of environmental planning is essential for promoting the health of citizens. Applying healthy city criteria through designing urban spaces and can lead to the general health of citizens. Cities gradually become closer to smart cities by crossing agricultural and industrial relations into smart and virtual cities, and evolving from virtual cities to smart cities urbanization patterns have evolved. In planning cities, citizens can play significant roles in collecting data and information from the surface of the city by sensors and smart devices on a variety of issues, such as traffic. City planners also need to listen to the voices of citizens. In smart cities, people, their behaviors and activities should be placed on the context and planning axis. Many countries in the world have moved towards the solutions of the virtual world to solve their urban problems and to motivate their citizens to participate in social life.

1. Introduction

The concept of landscape was coined in Europe in the 15th century (Berque, Citation2013). Indeed, the landscape is the exact sample of the duality between humans and the universe, nature and culture, subject and object, which were, set up by modern absolute reason (Alehashemi et al., Citation2017). As Keshtkaran (Keshtkaran, Citation2017) argues, researchers’ studies on the landscape through the objective or subjective approaches are rooted in Cartesian dualism. Therefore, several efforts have been made to fill this gap. Some recent philosophers such as Hegel Husserl and Heidegger have broken the bipolar structure of phenomena into objective or subjective by introducing existentialism and phenomenology. As stated by Mahan and Mansouri (Citation2017),

Heidegger proposes a topological model for thinking about the relationship between people and the landscape as a matter of the “thereness” of the self-disclosure of being in and of the world. The scope of the definition of landscape and the complexity of its concept and the interaction of the human with the environment in this vast area led the researchers to use different approaches in their researches. However, as Keshtkaran (Keshtkaran, Citation2017) believes, “researchers are trying to reduce the gap between objectivity and subjectivity and study paradigm with a holistic approach, which is evident in their definitions” (p. 142). Mander and Antrop argue that the landscape is the main issue of regional geography. The European Landscape Convention (ELC) defines landscape as “an area, as perceived by people, which character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors”. It has also been argued that understanding and analyzing the term of landscape chiefly refer to national or cultural units (e.g., Hokema & and, Citation2015; Stobbelaar & Pedroli, Citation2011). Simpson et al. (Citation2001) point out that landscapes are cultural assets for all of the people or “Landscape is shaped by mental attitudes and that a proper understanding of landscapes must rest upon the historical recovery of ideologies”(Baker and Biger, Citation2006).

A review of the related literature also shows that the use of the term landscape in science is relatively new. Very recently, the landscape has been used to refer to not only a subjective experience, which has perspective, artistic, aesthetical, and existential meaning, but also a phenomenon, which is analyzed and described by scientific methods. While acknowledging that it is dynamic and constantly changing, Antrop (Citation2005b) identified four forces that lead to landscape change: a) accessibility, b) urbanization, c) globalization, and d) calamities.

Lynch separated meaning form and examined the role it plays in the physical qualities associated with identity and structure. Through mental mapping, he sought to identify aspects of the environment that leave a strong image in the viewer’s mind. The aggregation of individual images defines the public or city image. Through this research, Lynch deduced five key physical elements: landmarks, nodes, paths, edges, and districts (Lynch, Citation1960). In addition, Hokema (Hokema & and, Citation2015) in his research to investigating a common understanding of landscape explains which major image of people from the landscape is related to some terms, which included nature, beauty, country, city, and garden.

Landscapes are believed to be combinations of cultural and natural phenomena (Steiner, Citation2014). It is also believed that cities are a product of cultural adaptation (Paknezad & Latifi, Steiner, Citation2014). Steiner (Citation2014) also believes that landscape perspectives at different “scales from the site to the region can help us appreciate urban nature and, therefore, design and plan more appropriate and safer urban communities. As landscapes differ from place to place so too should the perspective be adjusted” (p. 2). Nevertheless, the basic elements that comprise landscape are alike in different places. In other words, there are geologic, hydrologic, climatic, biologic, natural, and cultural processes that need to be taken into account by urban planners. It is also known that the natural landscape has been greatly affected by urbanization as a complex and multidimensional phenomenon with its ecological, spatial, economic, cultural, and social aspects (Arnaiz-Schmitz et al., Citation2018; Huu et al., Citation2018; Klug, Citation2012; Oteros-Rozas et al., Citation2014; Sack, Citation2013; Zoderer et al., Citation2016). Despite the significance of landscape as a cultural and natural phenomenon in economic and social challenges, and the significant role of the urban planners and inhabitants of a city in landscape design, no one has yet asked for the inhabitants’ perspectives of a good landscape design for a city in which they live.

1.1. Review of the literature

Numerous studies have been undertaken in the field of urban landscape explanation and urban landscape evolution. Among these researches, one can refer to Lynch’s (Citation1960) research on a city’s landscape. He divides the landscape into five factors: paths, nodes, edges, signs, and domains. He has also suggested that perceptional, physical, and functional factors are important in the urban landscape (Rezazadeh, Citation2016). Pakzad (Citation2006) also argues that the urban landscape is something objective and the subjective landscape has no meaning other than something felt heartedly. In the same vein, it is also believed that the visual, physical, spatial, identical, and environmental dimensions and characteristics of the neighborhoods and urban areas constitute the whole urban landscape. Mansouri (Alehashemi et al., Citation2017) also views the urban landscape as a member of an urban society. That is why he believes that it is not possible to make a distinction between objectivity and subjectivity in the definition of the urban landscape and does not believe that the city landscape is objectivity independent of human beings. Bell (Citation2003) analyzed the landscape of the city in a book (Landscape, Pattern, Perception, Process) and believed that landscape is a part of the environment in which people reside and it is understood through our perceptions (Bell, Citation2003). Nasser (1390), while trying to define the position of the urban landscape in human-environment interactions and defining its subjective and objective dimensions, tried to identify the citizens’ views and perceptions about the favorite landscape.

In fact, Landscape is a term that tends to gather meanings, from various disciplines with wide insights (Doevendans et al., Citation2007; Kaplan, Citation2009). That is, the landscape is a subject of interest in the social sciences, natural sciences, the arts, and humanities. According to these definitions, communities, legislators, industries, public stakeholders, users, etc. are the groups involved in landscapes, which while requesting various needs from landscapes, simultaneously contribute to landscapes (Jones et al., Citation2017). In line with these definitions, it can be argued that the landscape is a multi-layered phenomenon, which includes a various subjective, objective, individual and collective issues (Crow et al., Citation2006; Hunziker et al., Citation2007; Nassauer, Citation2011; Naveh, Citation2007). In this view, Lörzing (Citation2001) proposed four layers of relationships between man and environment: intervention (the landscape is what we make); b) knowledge (landscape as associated with facts we know); c) perception—the landscape is what we see, and d) interpretation—the landscape which we believe. This complexity is because of the extensive meaning of landscape obvious in numerous studies (Antrop & Van Eetvelde, Citation2017; Widgren, Citation2004; Winchester et al., Citation2013; Wylie, Citation2009).

Jones et al. (Citation2017) believe that urban landscapes are produced through the combination of material forms and subjective human experience. Drawing on the concept of atmosphere, they argue that the human experience of urban spaces drives alterations to the built environment. They also believe that atmospheres are created through the combination of human activity, individual emotional responses, and subjective perceptions of built forms. These atmospheres, though unique to the individual, can also create a shared feeling of the place.

Vaughan et al. (Citation2005) have given some senses of how different demographic groups might be viewed within space syntax by exploring poor urban connectivity as a predictor of urban deprivation. There are indeed several elements in urban landscape such as natural and artificial elements, people’s perception and mentality of the spaces, urban spaces, events that occur, time, culture, history, identity, holy matters, and signs that are recalled. Physical and environmental elements are directly perceived by human senses. Physical contact certainly has a positive effect on the health of the city space users (Philip & Emma, Citation2014). In the same vein, a great number of studies have been undertaken to analyze the factors affecting urban landscape and the memories which form the landscapes. Norman (Citation2011) also argues that the landscapes may be perceived through human’s activities, actions, and perceptions.

Wu et al. (Citation2013) mention, in simple way that the landscape ecology is identical with urban landscape ecology. More specifically, it is the science of studying and improving the relationship between urban landscape pattern and Ecological processes for achieving urban sustainability. They proposed three key components: urbanization patterns, urbanization impacts, urban sustainability. In this regard, Muderere et al. (2018 as cited in Paknejad & Latifi, 2018) investigated the related Literature and researches between 1986 to 2016 and extracted the most frequently terms in the urban landscape ecology researches, which included landscape ecology, landscape structure, landscape change, and biodiversity.

Soltani et al. (Citation2013) believes that the multi-layer characteristic of urban development allows the researcher to study the city as a combination of innumerable stories and can be effectively helping us in studying and repeating culture. Furthermore, Kincaid (Citation2005) argued that urban development is the reflection of memories, whether lost or retained. He elaborated on the relationship between memory, reconstruction, and city history and stated that urban memories originate from the story of people’s age (Kincaid, Citation2005). According to the Council of Europe, there are three systems within the landscape, which integrate social values, heritage values -both natural and cultural- and economic value. The areas of the city considerably vary based on the strength of their properties. Areas of very strong character usually have distinctive and prominent names, and other areas of lesser importance usually carry names that are related to their historical origin (Lynch, Citation1960; Paknejad & Latifi, Citation2018).

Despite the unparalleled importance and value of Lynch’s theory, criticism has been leveled against it; however, it has been followed and completed by various individuals. Appleyard’s investigation of the city of Sidadgoyana is one of these. In this study, Appleyard examined the city in terms of the socio-functional characteristics and characteristics of the environment in which the city is formed through individuals’ mental images. What environment is and how it is formed, the important group differences between people in terms of tastes and theories, as well as the identification of variables that explain this difference are the outcomes of Appleyard’s research of image landscape. Through quantitative research and compiling 200 signs, he mentioned the following features effective for remembering signs.

Among Iranian landscape architects, architects such as Shakibaee, Taqvaee, and Feyzi, have reffered to constituting elements of landscape and its dimensions. They have considered quantitative and qualitative aspects of landscape. Feyzi (Citation2010) writes that experts have offered a variety of definitions and approaches about the term landscape, but all of these definitions are relatively common in certain properties such as flexibility, objectivity. Feyzi and Khak Zand (Citation2008) offer a diagram of the general approaches to landscape and point out three human, natural (animate), and physical (inanimate) aspects of landscape.

Taqvaee (Citation2012) defines landscape as a relationship between natural and cultural patterns, constituent processes, and humans’ perception of the beauty of this complex. Moreover, Tagvaei (Citation2008) believes that landscape is a set of perceptual manifestations, cultural and philosophical arenas, and a context incorporating various kinds of shapes, patterns, wildlife species, and many natural creatures.

Gohari, Behbahanib, and Salehi (Gohari et al., Citation2015) attempted to identify elements and signs in urban landscape design that are associated with collective memories and to determine the extent of their impact on maintainability and consolidation of the cultural integrity and attachment to residential areas and urban spaces. In order to answer research questions, a landscape analysis method based on subjective perceptions was selected. The population of the study included 30 residents of the district aged 30 or above. The respondents were presented with the obtained elements, as well as six pictures in order to score them based on their subjective perception. Questionnaire data were analyzed and elements that affect subjective perceptions in the urban landscape were identified. They found that gardens, old buildings, and streets of Shemiran that have embraced many memories over time had the greatest effect on people’s mentality about urban landscape evocativeness. Such signs cause people to care more about what happens to urban landscapes. They also concluded that:

Shared memories in a specific place make people prefer that landscape to other ones when they recall those memories. In contrast, when collective memories fade over time, people feel less attached to the specific place, which makes them relocate their residence area since the memorable elements have gradually disappeared. Therefore, including elements in a landscape that brings most positive influences on mentalities over time would help protection, as well as emergence of spaces that are originating from people and their collective memories. (p. 45)

Manhan and Mansouri (Mahan & Mansouri, Citation2017) concluded that landscape in definitions has always relied on two main elements, the elimination of any of them results in an incomplete understanding of the landscape. “The first one is the environment which encompasses human beings and the second one is the human being who enters it in order to understand it and create a connection between them and creates images in his mind with the lapse of time. They also concluded it is necessary to know that landscape is an alive and dynamic existence that is influenced by human beings and their relationship with the environment. Furthermore, they believed that in an exalted deduction landscape is a phenomenon that is achieved through our simultaneous understanding of the environment and an interpretation of mind; in fact, the landscape is an objective- subjective phenomenon that is sometimes separated into objective and subjective aspects in order to study it more easily.

1.2. Purpose of the study

The present study aims at evaluating Tehran current city shape on urban composition and exploring appropriate future shape of Tehran from the participants’ perspectives using a a semantic differential scale. More particularly, this study evalustes the future of this city shape in terms of three dimensions of evaluative, power, and activity.

2. Method

To undertake the study, the researchers used a descriptive-analytic study. Through library research, the scholars’ ideas and perceptions have been systematically reviewed to develop the theoretical framework of the study. Then, a differential semantics scale was developed and used for collecting data which aimed at exploring an appropriate landscape for Tehran city. The questionnaire was developed based on three dimensions: evaluative, power, and activity. The main purpose of the questionnaire was to see how the participants expect the landscape of the city to be. The pictures were distributed among the participants. Each picture was accompanied by some attributes which evaluated the above mentioned three dimensions (Attributes classified in the evaluative dimension included regular-irregular, identified- unidentified, homogeneous-heterogeneous, and artifact-natural; attributes categorized in the power dimension include classical—romantic, modern—traditional, tall—short, and iconic—contextual, and finally varied -uniform and polymorphic—monochrome attributes were included under the category of activity). Then, a list of people whose views and perceptions were assumed to be influential and vital in formulating and designing the preliminary landscape of Tehran was prepared. Finally, the target participants including university professors, experts, consulting engineers who have drawn detailed plans for the 22 districts of Tehran, city officials and managers in various municipal departments, organizations and affiliated companies such as the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, technical and executive agencies, and parliamentarians received the questionnaire. Only 59 respondents answered and returned the questionnaire. Therefore, the exact sample size consisted of 59 participants who were selected through purposive sampling.

2.1. Differential sematics technique

A psychologist named Charles Osgood in 1957, to measure the connotative meaning or emotional meaning of words, invented the differential semantics technique. Initially, this technique was used to study people’s views about personality, phenomena, and objects in psychology, but because of the capability of the technique, it can also be used to measure people’s views on “urban landscape features” (HEISE, Citation1967). By examining thousands of adjectives in the Thesaurus dictionary, Osgood found that all the attributes used to describe a person or an object can be categorized into three dimensions. He called this three-dimensional space “the semantics space”(HEISE, Citation1967). The three dimensions used to describe peoples’ perspectives about anything include evaluative dimension (consisting of adjectives like good-bad, pleasant-unpleasant, kind-cruel; power dimension (such adjectives like powerless-powerful, thin-thick, soft-hard), the dimension of activity (including adjectives like passive-active, slow- fast, cold-hot, See ).

The three dimensions of differential semantics form a three-dimensional graph. The semantics space or emotional space shown in the is the coordinate point of origin in that space, indicating a neutral feeling.

Research has proven that these three dimensions of emotional meaning are universal:

Steps for developing a differential semantic scale:

First, it is necessary to identify traits that are related to a phenomenon through a pilot study.

Identify the opposite adjectives

Put the adjectice at either side of a seven-pint ruler

Ask the people to evaluate the variable in the question based on the opposite adjectives

Present the results on a three dimentional graph

3. Results and discussion

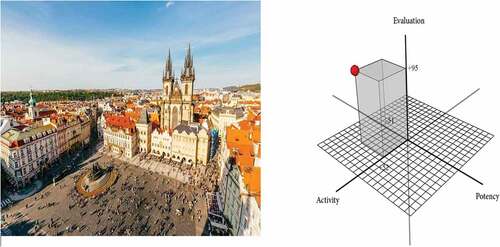

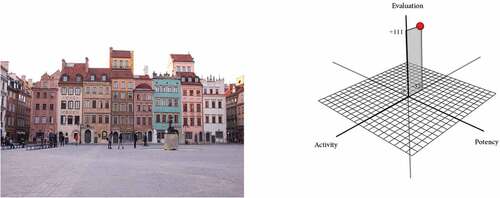

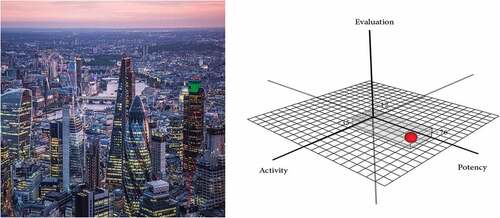

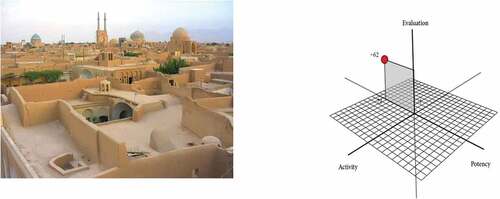

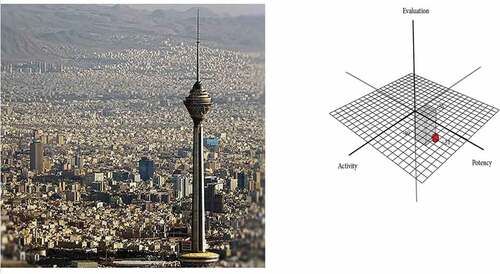

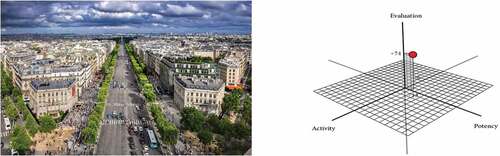

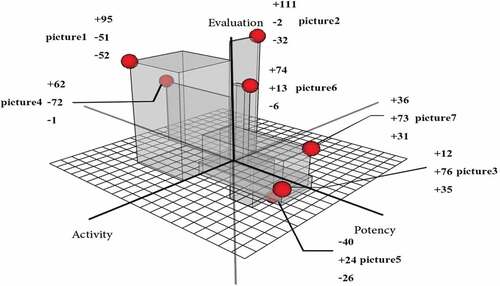

show the results for the question that asked the participants to choose among the 8 presented pictures the ones which they think, are the most appropriate for the future of Tehran’s urban landscape. The suggested images are as follows. The suggested pictures are as follows.

Table 1. Three dimentional emotional meaning of phenomena

Table 2. Frequencies of pictures selected as resemblance of Tehran’s urban landscape in future

As can be seen in , the majority of respondents chose Option 8, suggesting that 22.2% believed that the desired Tehran’s urban landscape in the future is similar to none of the presented pictures. Results also show that pictures 1 and 4 were chosen by 14.8 percent of the participants. Pictures 2 and 6 were chosen by 12.3 percent of the participants. Picture 3 was selected by 11.1 percent of the respondents. However, 8.6 and 3.7 percent of the participants, respectively only selected pictures 7 and 5. To analyze the collected data presented in the above table and graph, the differential semantics technique, which can be used for investigating the participants’ views about Tehran’s urban landscape, was used. In so doing, the eight pictures mentioned above were distributed among a group of experts. The participants evaluated each picture using one of the two adjectives through a 7 point scale (−3, −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3). As an example, the most desired picture was given +3, while −3 was given to the least desired picture which looks likes the future of the urban landscape of Tehran. Results are presented in the following

Table 3. Opposite attributes for evalustion

The results of the evaluation for each picture were plotted on a three-dimensional graph (evaluative, power, and activity dimensions). Attributes classified in the evaluative dimension included regular-irregular, with identity -without identity, homogeneous-heterogeneous, and artifact-natural; attributes categorized in the power dimension include classical—romantic, modern—traditional, short—tall, and iconic—contextual, and finally diverse -uniform and polymorphic—monochrome attributes were included under the category of activity

presents an urban landscape in which the evaluative dimension is the most powerful (evaluative = +95). That is, the urban landscape is regular and homogenous, it has an identity, and its artificial elements are more than its natural elements. Whereas, the figure indicates that it has the least significance in terms of activity dimension (activity = +52). The power dimension is also rated as a week (power = −51). It means that the urban landscape is romantic, traditional, short, and contextual with no skyscrapers. Indeed, through looking at this picture a viewer can identify the identity which it shows and recognizes the structure as regular.

The analysis of the EPA diagram shows that in , the evaluative dimension differs from the other two dimensions (evaluative dimension = +111), i.e, the city has a regular, uniform, and homogenous landscape. Like , its power dimension is somehow neutral, i.e., it is uniform (power = −2), and its activity dimension is negative (activity = −32).

was selected by 11.1 percent of the participants and the EPA diagram shows that the landscape of such a picture has the highest power (power dimension = +76). That is, the urban landscape is modern, classic, tall, and iconic and it seems that the activity dimension looks like a polychromic and varied urban. However, its evaluative dimension is very week (evaluative = +12). Despite its week evaluative dimension, its landscape is somehow regular, homogenous, and artificial.

Analysis of EPA diagram of indicates that the evaluation dimension is more powerful in this image (evaluation dimension = +62), as in , the power dimension is very week. (Power dimension = −72). With regard to activity dimension, it shows that the activity dimension of the image is somehow neutral (activity = −1). That is, it is neither varied nor uniform and neither polychrome nor monochrome. In sum, the evaluative dimension of this image is very tall, but its power dimension is negative. The only difference is that the activity dimension in one image is neutral but in the other picture is rather tall (+52).

had the lowest frequency (3.7%). According to the EPA diagram of this image (No. 5), such a city landscape is considered irrelevant, highly irregular, unidentified, heterogeneous, and normal (evaluative dimension = - 40). Regarding its activity dimension, it can be inferred that the city has a monochrome urban landscape (Activity dimension = −26). However, it can be seen in that its power dimension is positive (power = 24) indicating that it a relatively modern, classical, tall, and iconic.

The EPA diagram of shows that the urban landscape character of this image is dominant. That is, it has a regular urban landscape with identity, homogeneity, and more artifacts, while power is lower but lower than. The next view is a negative activity. As seen in , while its power dimension is the lowest, but its’ activity dimension is negative,i.e., the urban landscape is more monochrome.

This picture was selected by 8.6 percent of the participants. Its EPA figure shows that such a city has a landscape with high power (power dimension = +73),i.e., it is very modern, tall, classic, and iconic. It also has approximately equal evaluative and activity dimensions (evaluative dimension = +36, activity dimension = +31), i.e., the landscape is identified, regular, homogenous, synthesized, varied, and polychrome.

Through comparing the three-dimensional EPA diagrams of the pictures and the selection frequency of each picture, it can be concluded that is more proportionate to the three dimensions of evaluation, activity, and power, although it has the least frequency, and both pictures 1 and 4 with the highest frequency have specific qualities and characteristics of an urban landscape. As mentioned earlier, the next selected pictures are 2 and 6. Therefore, it can be concluded that the selection of pictures 2 and 6 at one level reflects the urban landscape that is regular, identified, homogeneous, and artificial(synthesized), and it is almost modern, classical, high, and iconic while being very uniform and monochrome.

4. Conclusions

The urban landscape, as one of the key elements of each city texture, can be effective in meeting some of the individuals’ needs. The landscape, on the one hand, cannot be summarized solely in the texture because it also contains both quality and meaning. The landscape of each city is the output of its realities. Therefore, it can not be considered as an abstract phenomenon, because we understand it through the text and the senses and perceive it through a phenomenological and semiotic relation. Therefore, landscape a phenomenon perceived through both our perception of the environment and subjective interpretation. Indeed, it is a subjective-objective phenomenon. An appropriate, well-organized, and systematic urban landscape creates a pleasant feeling of living in the urban environment and is one of the key factors in the relationship between the city and the citizen. When the urban landscape is plagued by confusion and anonymity, this feeling is also transmitted to citizens and presented as urban abnormal behaviors in the urban environment, and, on the other hand, disrupts the rational relationship between the citizens and the city.

In this paper, the three dimensions of evaluative, power, activity through using the differential semantic technique, and certain attributes were analyzed, weighted, and presented in the graphs. Through analyzing the EPA of the pictures suggested for the future landscape of Tehran, it can be inferred that the present landscape of Tehran is not preferred by the selected participants and there is no agreement among the participants’ perceptions about the favorite landscape. However, based on their ideas, it can be concluded that it is necessary to accept a contextual architecture in urban landscape design along with the issues of regularity and homogeneity as well as contextualization and objective perception of the contextual message based on cultural, social, historical, climatic and contextual backgrounds. It is also necessary to pay attention to emotional issues and dimensions of the landscape. Having no interest in modernity and tall buildings is another issue emphasized through differential semantic techniques. The superiority of space over mass through omitting the humanistic scales is another issue that is perceived from the selected pictures. Moreover, a return to the architectural origins of contextualism and ecology in Tehran’s future urban landscape is of much significance. Furthermore, more colorful natural attractions of the buildings created by human beings are viewed, and human landscapes have features such as rhythm, symmetry, etc. However, it is necessary to mention that the ideas of the experts are based on their scientific and technical knowledge. Therefore, urban experts and managers must guide the new developments in the urban landscape along with the views of citizens and users of urban spaces. They also need to assess the citizens’ perceptions about their favorite urban landscape and to take into account the aesthetic and functional perspectives of the synthesized urban environment. In the same vein, they have to identify and analyze parameters such as visual corridors, street views, visual communications, identity, and security areas. Finally, to present an appropriate urban landscape for Tehran city, the following suggestions are made:

•Laying emphasis on the aesthetic values with regard to the past, present, and future identities

•Achieving physical integration with a future based identity with regard to different social, economic, and cultural dimensions

•Preserving and enhancing functional aspects due to the formation of human and humanistic phenomena interacting with the urban landscape

•Receiving citizens’ maps and mental images of the city at different times, and

•Investigating and identifying the audience, their wishes and expectations and taking them into consideration at all stages of the urban landscap.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gholamreza Latifi

Gholamreza Latifi is associate professor at department of urban and regional planning, faculty of social sciences, at Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. He has published many papers in national and international journals. He is also chief editor of several journals on urban planning which are published in Persian, He has attended several conferences. Now, he is vice chancellor of the university. He has also supervised many Ph.D. dissertations.

Navid Paknezad is PhD student of urban planning at Department of Urban Planning, Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qazvin Branch, Islamic Azad University, Qazvin, Iran.

References

- Alehashemi, A., Mansouri, S. A., & Barati, N. (2017). “Urban infrastructures and the necessity of changing their definition and planning Landscape infrastructure; a new concept for urban infrastructures in 21st century. The Monthly Scientific Journal of Bagh- E Nazar, 13(43), 5–15.

- Antrop, M. (2005b). Why landscapes of the past are important for future. Landscape and Urban Planning, 70(1–2), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.002

- Antrop, M., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2017). Landscape Perspectives: The Holistic Nature of Landscape. Springer.

- Arnaiz-Schmitz, C., Schmitz, M., Herrero-Jáuregui, C., Gutiérrez-Angonese, J., Pineda, F., & Montes, C. (2018). Identifying socio-ecological networks in rural-urban gradients: Diagnosis of a changing cultural landscape. Science of the Total Environment, 612, 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.215

- Baker, A.R.H., & Biger, G. (2006). Ideology and landscape in historical perspective: essays on the meanings of some places in the past. Cambride University Press.

- Bell, S. (2003). Landscape: Pattern, Perception, Process. Translated to Persian by Amin Zadeh, B. University of Tehran.

- Berque, A. (2013). Thinking through landscape. Routledge.

- Crow, T., Brown, T., & De Young, R. (2006). The Riverside and Berwyn experience: Contrasts in landscape structure, perceptions of the urban landscape, and their effects on people. Landscape and Urban Planning, 75(3–4), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.04.002

- Doevendans, K., Lörzing, H., & Schram, A. (2007). From modernist landscapes to New Nature: Planning of rural utopias in the Netherlands. Landscape Research, 32(3), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390701318270

- Feyzi, M. (2010). Urban landscape: Comparative evaluation of three concepts in cities. Manzar, (9)1, 14–15.

- Feyzi, M., & Khak Zand, M. (2008). Design process in urban landscape, past and present. Bagh- e Nazar, 9(2), 65–80.

- Gohari, A., Bebahani, H. M., & Salehi, A. (2015). Urban-historical landscape analysis on the basis of mental perceptions case study: Tajrish neighborhood. Space Ontology International Journal, 4(15), 39–48.

- HEISE, D. (1967). The Semantic Differential and Attitude Research. University of Wisconsin.

- Hokema, D. (2015). Landscape is everywhere, the construction of landscape by US-American laypersons. In D. Bruns, O. Kühne, A. Schönwald, & S. Theile, (Eds.), Landscape Culture - Culturing Landscapes, the Differentiated Construction of Landscapes (69–80). Springer VS.

- Hunziker, M., Buchecker, M., & Hartig, T. (2007). Space and place–Two aspects of the human- landscape relationship. In F. Kienast, O. Wildi, & S. Ghosh (Eds.), A changing world (pp. 47–62). Springer.

- Huu, L. H., Ballatore, T. J., Irvine, K. N., Nguyen, T. H. D., Truong, T. C. T., & Yoshihisa, S. (2018). Socio-geographic indicators to evaluate landscape cultural ecosystem services: A case of Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Ecosystem Services, 31, 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.11.003

- Jones, P., Isakjee, A., Jam, C., Lorne, C., & Warren, S. (2017). Urban landscapes and the atmosphere of place: Exploring subjective experience in the study of urban form. Environmental Sciences 6(1), 111-122 Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319302593.

- Kaplan, A. (2009). Landscape architecture’s commitment to landscape concept: A missing link? Journal of Landscape Architecture, 4(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2009.9723413

- Keshtkaran, R. (2017). Urban landscape: A review of key concepts and main purposes. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 8(2), 141–168.

- Keshtkaran, R., Habibi, A., & Sharif, H. (2017). Aesthetic preferences for visual quality of urban landscape in derak high-rise buildings (Shiraz). Journal of Sustainable Development, 10(5), 94. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v10n5p94

- Kincaid, A. (2005). Memory and the city: Urban renewal and literary memoirs in contemporary Dublin. College Literature, 32(2), 16–43. https://doi.org/10.1353/lit.2005.0029

- Klug, H. (2012). An integrated holistic transdisciplinary landscape planning concept after the Leitbild approach. Ecological Indicators, 23(4), 616–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.05.019

- Lorzing, H. (2001). The nature of landscape: a personal quest.

- Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the City. The MIT Press.

- Mahan, A., & Mansouri, S. A. (2017). The study of landscape concept with an emphasis on the views of authorities of various disciplines. The Monthly Scientific Journal of Bagh- E Nazar, 14(47), 17–28.

- Nassauer, J. I. (2011). Care and stewardship: From home to planet. Landscape and Urban Planning, 100(4), 321–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.02.022

- Naveh, Z. (2007). Landscape ecology and sustainability. Landscape Ecology, 22(10), 1437–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-007-9171-x

- Norman, B. (2011). Regional environmental governance: Interdisciplinary perspectives, theoretical issues, comparative designs (REGov). Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 14, 193–202.

- Oteros-Rozas, E., Martín-López, B., González, J. A., Plieninger, T., López, C. A., & Montes, C. (2014). Socio-cultural valuation of ecosystem services in a transhumance social-ecological network. Regional Environmental Change, 14(4), 1269–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0571-y

- Pakinejad, N., & Latifi, G. (2018). Explaining and evaluating the effects of environmental components on the formation of behavioral patterns in urban spaces (from theory to practice: The Tajrish field study). Bagh Nazar Journal, 15(69), 51–66.

- Pakzad, J. (2006). The theoretical foundation and process of urban design. Tehran, Iran: Shahidi. [in Persian]

- Philip, B., & Emma, S. (2014). The power of perceptions: Exploring the role of urban design in cycling behaviours and healthy ageing. Transportation Research Procedia, 4, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2014.11.006

- Rezazadeh, R. (2016). Principles and standards of urban landscape. Research project at Urban and Architectural Research and Research Center.

- Sack, C. (2013). Landscape architecture and novel ecosystems: Ecological restoration in an expanded field. Ecological Processes, 2(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/2192-1709-2-35

- Simpson, I. A., Dugmore, A. J., Thomson, A., & Vésteinsson, O. (2001). Crossing the thresholds: Human ecology and historical patterns of landscape degradation. Catena, 42(2–4), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(00)00137-5

- Soltani, A., Zargari, M., Ebrahim, N., & Ahmad, A. (2013). Formation, reinforcement, and durability of memory in uirban spaces, Case Study: Shahid Cahmran Area of Shiraz. Residence and Rural Environment Quarterly, 141(1), 87–98.

- Steiner, F. (2014). Urban landscape perspectives. Land, 3(1), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.3390/land3010342

- Stobbelaar, D. J., & Pedroli, B. (2011). Perspectives on landscape identity: A conceptual challenge. Landscape Research, 36(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2011.564860

- Tagvaei, S.H. (2008). Tacit knowledge and deep Ecology; A Hermeneutic approach to the concept of environmental tacit knowledge in landscape architecture. Environmental Sciences 6(1), 111–122.

- Taqvaee, H. (2012). Landscape architecture: An introduction to definitions and theoretical basis. Shahid Beheshti University.

- Vaughan, L., Clark, D. L. C., Sahbaz, O., & Haklay, M. (2005). Space and exclusion: Does urban morphology play a part in social deprivation? Area, 37(4), 402–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00651.x

- Widgren, M. (2004). Can landscapes be read? In H. Palang, H. Sooväli, M. Antrop, & G. Setten (Eds.), European rural landscapes: Persistence and change in a globalising environment (pp. 455–465). Springer.

- Winchester, H. P., Kong, L., & Dunn, K. (2013). Landscapes: Ways of imagining the world. London.

- Wu, J., He, C., Huang, G., & Yu, D. (2013). Urban landscape ecology: Past, present, and future. In B. Fu & K. B. Jones (Eds.), Landscape ecology for sustainable environment and culture (pp. 37–53). Springer.

- Wylie, J. (2009). Landscape, absence and the geographies of love. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 34(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00351.x

- Zoderer, B. M., Stanghellini, P. S. L., Tasser, E., Walde, J., Wieser, H., & Tappeiner, U. (2016). Exploring socio-cultural values of ecosystem service categories in the Central Alps: The influence of socio-demographic factors and landscape type”. Regional Environmental Change, 16(7), 2033–2044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0922-y