?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The outbreak of Corona Virus (COVID-19) in the 4th quarter of year 2019 at Wuhan city of China, and its rapid spread across the world necessitated the introduction of travel restriction policies by the federal and state governments of Nigeria. This was to help curtail the spread of the deadly disease. This study examined the travel behaviour of flouting commuters in Makurdi metropolis amidst the travel restriction policy during the lockdown period. About 496 questionnaires were administered to commuters travelling within the 16 km radius metropolis. Essential factors captured in the questionnaire included modal split and trip purposes as affected by socio-demographic characteristics of commuters such as; age, gender, marital status, level of education, etc. The findings of the study revealed that there was no statistically significant level of dependence of commuters’ socio-demographic characteristics on modal split and trip destinations at 5% level of significance using contingency tables. The trend revealed that there were no obvious influential changes in the travel behaviour of commuters in Makurdi metropolis amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. It was recommended that concerned authorities should create more awareness about the outbreak of pandemics to help instil fear in commuters and discourage travelling to prevent wide spread. Also, distribution of palliatives to households during lockdown periods to enable them cope with the situation as they remain indoors, and deployment of law enforcement agents to streets and highways to stop commuters from travelling during lockdown periods to minimise the spread of communicable diseases were recommended.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The investigation of travel behaviour in Makurdi metropolis amidst the travel restriction policy by the federal and state governments in Nigeria due to the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic is essential to transport experts, town planners, economists, health workers and policy makers. Our study emphasised on mode choice and trip purposes during the lockdown period as affected by socio-demographic characteristics of the flouting commuters. Findings of the study revealed that there was no significant level of dependence of commuters’ socio-demographic characteristics on mode choice and trip destination. This trend showed that there were no obvious influential changes in the travel behaviour of commuters in Makurdi metropolis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, concerned authorities were urged to create more awareness on the effects of pandemics to help instil fear in commuters and discourage travelling during epidemics to prevent wide spread, provision of palliatives to households during lockdown periods and deployment of law enforcement agents to streets and highways to stop commuters from travelling.

1. Introduction

The understanding of people’s movement, goods, ideas and information around metropolitan areas is very important for human existence and social development, as well as behavioural interventions, which trigger economic and socio-cultural growth of the area (Adnan et al., Citation2019; Gudmundsson et al., Citation2016; Veternik & Gogola, Citation2017). An essential aspect of human fulfilment in every society is a measure of free movement or efficient transport system (Adeke et al., Citation2018; Bashingi et al., Citation2019; Ceder, Citation2007; Schiller et al., Citation2010). The measure of activity-based travel behaviour in cities is easily reflected by the number of home-based and non-home-based trips, total distance travelled per trip, types of destinations and mode choices used (Adnan et al., Citation2019; Malavenda et al., Citation2020). Life generally becomes unconducive and unbearable when healthy people cannot move from one place to another. This therefore implies that the recent travel ban and movement restriction policies enacted by world leaders to curtail the spread of Corona Virus (COVID-19) pandemic have significant impact on human coexistence (World Bank Group, Citation2020). These policies have restrained many human activities within states, thus affected every facet of human endeavour such as business, social life, administrative, educational, etc. (Mogaji, Citation2020; Veternik & Gogola, Citation2017; Yezli & Khan, Citation2020). Due to this ugly situation, many people embarked on teleworking, the act of working from home using electronic gadgets thereby denying workers physical interaction with colleagues (Bhuiyan et al., Citation2020; Mogaji, Citation2020; Shergold et al., Citation2015; Zalite & Zvirbule, Citation2020).

The need to study human dynamics which influence peoples’ travel behaviour is due to its correlation with the performance of transport systems and policy interventions (Adnan et al., Citation2019; Chinazzi et al., Citation2020; Jain & Tiwari, Citation2019; Malavenda et al., Citation2020; Mogaji, Citation2020). This calls for attention from town planners, transport engineers and economist, etc. whose responsibilities include to investigate, plan and develop cities and systems with sufficient facilities that can carter for the needs of city dwellers as social intervention or for public health response actions (Chinazzi et al., Citation2020).

Travel behaviour is a function of commuters’ social demographic characteristics and the built environment or land use policies (Etminani-Ghasrodashti & Ardeshiri, Citation2015; Jain & Tiwari, Citation2019; Mogaji, Citation2020; Veternik & Gogola, Citation2017), such characteristics include the level of education, age, household size, gender, car ownership, marital status, etc. (Malavenda et al., Citation2020; Ortuzar et al., Citation2011). The benefits of travelling include education, business, recreation, health and wealth; while transport service providers on the other hand generate revenue to boost the economy, hence travelling is very essential in an economic conscious society (Adnan et al., Citation2019; Bashingi et al., Citation2019; Veternik & Gogola, Citation2017; World Bank Group, Citation2020).

In spite of its numerous benefits, travelling exposes commuters to different forms of hazards ranging from the effects of air pollutants such as; Nitrogen oxide (NOx), Carbon oxide (COx), Sulphur oxide (SOx), small particles (PMx), etc. emitted from automobile tail pipes distributed within the environment (Tipaldi et al., Citation2020). Disease contraction and injury or fatal accidents are also other forms of negative externalities associated with travelling that are hurtful to commuters (World Health Organisation (WHO), Citation2005; Ojo & Awokola, Citation2012; Mmom & Essiet, Citation2014; Flugel et al., Citation2019; Adnan et al., Citation2019).

In most low- and medium-income countries, the use of public transport system in practice necessitate sharing of common space among commuters. This promotes staying together within confined spaces usually about 10 m2 or less in buses or trains where passengers sit less than 0.5 m apart, with people whose health status are usually unknown in most cases. This is risky as the likelihood of disease transmission vis-a-vis contraction among passengers becomes very high (Mogaji, Citation2020; Tipaldi et al., Citation2020; Yezli & Khan, Citation2020). Also, accidents are sudden events that are hardly predicted correctly, though could be envisage based on some common pointers or journey attributes. Sustainable transport policies attempt to address such challenges to ensure smooth and healthy movement of people around metropolitan areas. Therefore, the planning and development of public transport system requires the analysis of commuters behavioural attributes (Malavenda et al., Citation2020). The most sensitive attributes that influence travel behaviour in terms of modal split and trip destination or purpose include, travel time or distance, available mode and fare or attractiveness in terms of comfort and safety (Adnan et al., Citation2019; Chen & Li, Citation2017: Mogaji, Citation2020; Ortuzar et al., Citation2011). The consideration of essential travel behaviour attributes is important in developing public transport policies or work plan for intervention by concerned authorities (Jain & Tiwari, Citation2019: Mogaji, Citation2020).

The outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, an infectious disease in the 4th quarter of year 2019 at the city of Wuhan, China has put the entire world at disarray and stand still in some parts (De Vos, Citation2020). The pandemic has spread rapidly across nations killing people at geometric rate (World Bank Group, Citation2020). According to Okunlola et al. (Citation2020), the psychological effect of the pandemic on the general public is in multiple folds due to their misconceptions about its spread and effects. This situation led to the adoption of impromptu travel restriction policies by government authorities which affected air, land and water travel behaviour across the world due to associated “physical distancing” rule, a policy that even transport modellers never anticipated in the past and was not incorporated in transport modelling (Moslem et al., Citation2020). This scenario influences to a great extent the general conception of commuters’ mode choice which ideally depended on their socioeconomic characteristics and relative attractiveness and availability (Ortuzar et al., Citation2011).

Due to the spread of the pandemic, policy makers in all nations of the world restricted movement of people from one place to another be it by air, land or water (Mogaji, Citation2020). Though the lockdown had devastating effect on human existence in terms of acquiring some basic needs such as food, medication, finance, etc., it was aimed at minimising the risk of contracting the infectious disease from infected travellers. Medical experts stated that any person not infected with COVID-19 disease has high risk of contracting it when he or she comes in contact with and infected person or by staying near the victim when he/she sneezes, coughs, touches his or her eyes, mouth and nose, etc. This therefore requires physical distancing, the use of disinfectants on surfaces and hand washing using soap (Gossling et al., Citation2020; Hotle et al., Citation2020; Okunlola et al., Citation2020). The policy of physical distancing as declared worldwide entailed that people stay at reasonable distances of at least 0.5–2.0 m away from each other, be it family members, fellow friends and associates, colleagues, etc. in public places (Tipaldi et al., Citation2020). The policy promulgated into the “stay at home” rule aimed at preventing people from mingling with others so as to help minimise the spread of the COVID-19 disease significantly. The actualisation of this new travel policy involved the deployment of security agents to guarantee full implementation and compliance. Though, an investigation of the impact of COVID-19 on travel behaviour in terms of travel delay, fuel consumption and emission of pollutant at a microscopic level during the pandemic season revealed significant reduction in travel demand, which was proportional to reduced level of pollution, congestion and delay (Mogaji, Citation2020; Du et al. Citation2020).

Akin other parts of the world, in order to curtail the spread of the pandemic in Makurdi the capital city of Benue state, the state government like every other state in Nigeria made proclamations on the restriction of movement around the state and public gatherings in learning and administrative institutions, worship centres, markets, etc. This included interstate, intrastate and town shuttles through the “stay at home” safety policy. Though the stay at home policy was common to most cities of the world as a major strategy to minimise spread of the disease to some extent (Gossling et al., Citation2020), the desire to satisfy basic needs of most citizens of Makurdi metropolis necessitated flouting the rule, as they trooped out in large numbers on daily bases to obtain some basic utilities such as food stuffs, toiletries, drugs, call and data units, etc. or carryout other essential businesses and administrative functions. Though the travel restriction policy in Makurdi metropolis excluded health workers, security agents, food vendors, men on special duties, and telecommunication personnel who were allowed to discharge their duties uninterruptedly, other dwellers of the metropolis were expected to remain at home within a certain period. Most institutions were locked down to help reduce the chances of contracting or spreading the disease (Hotle et al., Citation2020). This travel ban was not accepted in good fate by some Makurdi dwellers. In spite of the continues publicity on the negative impact of COVID-19 as published by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), people insisted on short distance travel, basically to obtain essential needs or carry out some duties. This act was highly against the will of local authorities, who took several preventive steps as some arrests were made to help curb the ugly act instantly within the metropolis. As at the end of March 2020 during our field work, the NCDC had declared 139 confirmed cases, 9 discharged and 2 deaths in Nigeria with Lagos state and Abuja Federal Capital Territory (FCT) taking the lead (Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), Citation2020).

This study could not find previous studies on travel behaviour in the metropolitan area of Makurdi, and there has never been a policy of such on travel restriction for comparison and inferences. It therefore required the use of basic attributes to avoid complications (Excel & Rietveld, Citation2001), and the adoption of microscopic analysis of travel behaviour as witness in previous studies which yielded recommended results (Pratico et al., Citation2012; Du et al., Citation2020). Only few commuters who flouted the travel restriction rules were assessed, hence no determination of representative sample size using standard methods (Okunlola et al., Citation2020).

The aim of the study was to investigate the level of compliance and travel behaviour of commuters within Makurdi metropolis in response to the travel restriction policy. Objectives of the study included; to investigate commuters’ modal split and the distribution of trip purposes, to investigate the dependence of commuters social demographic characteristics on travel behaviour. The methodological structure of the study is presented in ;

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area

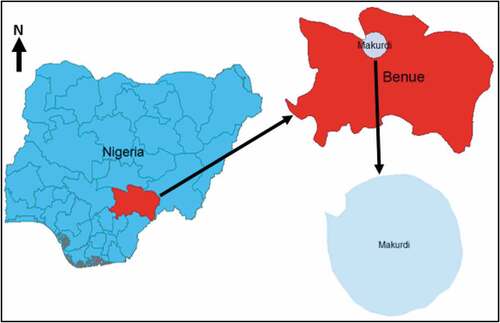

Makurdi metropolis is the capital city of Benue state, in the North-central geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It is the centre of social, administrative, educational, cultural and commercial activities in Benue state. The city lays within 16 km radius area which falls within N7°37ʹ60”N to 7°50ʹ20”N and 8°19ʹ30”E to E8°40ʹ20”E coordinates. Human population residing in the metropolis is estimated at 500,797 persons (NPC, Citation2006). An extract map of Makurdi metropolis is shown in ;

At the time of this study, the available mode choices in Makurdi metropolis included; minibuses, taxies, tricycles (locally known as Keke Napep), motorcycles (also known as Okada), private cars and walking. Based on land use policies in the metropolis, major trip attraction centres included; worship centres, academic institutions, administrative centres and markets. Others included hospitals, shopping malls, pubs, sporting and recreational centres, house-to-house visitation by friends and associates, while essential workers embarked on trips to banks, offices, hotels, etc. for home-based trips in the cosmopolitan city.

2.2. Data collection and analysis

Though there was no strict movement ban but a partial curfew in Makurdi from 7:00 pm to 6:00 am, the fear of contracting the disease compelled most commuters to adhere to the “stay at home rule”. Only few persons seen as flouters of the rule became the targeted respondents of the study, since all streets were almost deserted. Research questionnaires were designed and administered to 530 respondents found moving around the metropolis at the third week after the outbreak of the disease in Nigeria, only 496 were retuned. Respondents were contacted at public places such as; sport centres, pub, supermarkets, banks, hospitals, open markets and on-streets. Analysis of results involved percentage distribution of social demographic characteristics across mode choices and trip destinations, and the use of Chi-square statistical test to examine the dependence of commuters’ social demographic characteristics on modal split and trip destinations at 5% level of significance.

3. Results and discussion

The average performance of modes in Makurdi metropolis is presented in ;

Table 1. Mode performance attributes

Unlike in traffic networks of developed countries characterised by designated stops for public transport modes, Makurdi metropolis operates a poorly designed system without designated stops for passengers to alight on modes (Adeke et al. Citation2019). Public transport modes in Makurdi pick up and alight passengers randomly along the roads on demand as they cruise around the metropolis. This practice makes estimation of representative values for travel attributes such as fare and travel time have wide margin of errors.

The percentage distribution of commuters’ social demographic characteristics and modal split in Makurdi metropolis is presented in ;

Table 2. Participants’ characteristics and modal split

reveals that modes with high demand included walking, minibuses and okada at 25.0, 24.4 and 23.59%, respectively, while those with low demand included Keke Napep, private cars and taxies at 11.09, 15.12 and 0.60%, respectively. Since mobility was key factor for promoting the spread of COVID-19 disease (Gossling et al., Citation2020; Hendrickson & Rilett, Citation2020), and some trip attraction points were totally locked down, most commuters preferred walking as a micromobility mode and to isolate themselves from other persons for short distance travels (Moslem et al., Citation2020). Because a before COVID-19 study was not carried out by this research or any other previous study for Makurdi metropolis, the above modal split serves as the benchmark for this analysis.

Commuters within the age range of 15–45 years constituted 79.23% of the total respondents that flouted the stay at home rule more than the teenagers and the aged persons. This was attributed to the relatively high engagement of adults in social activities and juvenile effects (Zwerts et al., Citation2010), compared to the unlikely willingness to travel by the elderly persons aged above 45 years who were said to be more prone to attack by COVID-19 disease (Soltani et al., Citation2012; Hu et al., Citation2013; Somenahalli & Shipton, Citation2013; Jirgba et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, the idle teenagers, due to school and office lockdown did not embark on long distance trips, hence used the walk mode more frequently (Bajracharya & Shrestha, Citation2017), which guaranteed social distancing rule as specified by COVID-19 operational guidelines (Koehl, Citation2020; Okunlola et al., Citation2020).

The activity-based modal split was influenced by the corresponding level of education of commuters who had attained at least low level of education based on their sensitivity to utility difference threshold as reported in Pan and Zuo (Citation2020). There was relatively low demand for taxi, which is commonly used by visitors who in most cases were not familiar with the metropolitan city or needed private cruising. Therefore, the poor demand for taxi further justified the restriction of interstate travel policy. More female commuters embarked on trips using minibuses more often than their male counterparts; this agreed with findings of Bajracharya and Shrestha (Citation2017), though the mode choice exposed them to the risk of contracting the disease—no physical distancing (Mogaji, Citation2020; Yezli & Khan, Citation2020). Furthermore, the choice of reducing bus standard capacity to help achieve social distancing among passengers was practically absurd due to its associated cost of maintenance by the owners (Koehl, Citation2020), hence was ignored.

The married commuters used the commonest public transport modes, the okada and minibuses at 15.73 and 12.70%, respectively; while the unmarried used walking as well as the minibuses at 16.33 and 11.69%, respectively. This even distribution was attributed to the desire to attend social functions, going for shopping, spotting events and the pub within the neighbourhood (Yezli & Khan, Citation2020). Household sizes with greater than 15 persons did not embark on many trips as compared to those with smaller sizes. The common mode used by households included okada, minibuses and walking, as well as private cars and the Keke Napep. This travel pattern was attributed to the essential needs for short distance travel which does not require motorised system.

The distribution of commuters’ social demographic characteristics and trip distribution patterns in Makurdi metropolis is presented in ;

Table 3. Participants’ characteristics and trip distribution

reveals that shopping, others and pub destinations attracted relatively high trips at 41.73, 25.00 and 15.93%, respectively, compared to hospitals, games, visitation at 2.02, 7.66 and 7.66%, respectively. The high demand for shopping trips was basically for food stuffs; trips to the pub or eatery for drink or food were somewhat high since most people considered the lockdown period as conventional break from work (Yezli & Khan, Citation2020). Other destinations such as the bank, offices and hotels attracted most of the essential work force that had permission to travel within the metropolis. There was approximately equal percentage distribution of trip destination across social demographic classes of level of education. Most single female commuters’ travelled for shopping (or as vendors) and other activities. This travel pattern was attributed to the need to visit the groceries and other utility shops for basic needs. On the other hand, the pub attracted relatively high number of male commuters who went out for refreshment and relaxation with friends. Also, the study revealed that relatively high number of unmarried commuters travelled to various destinations compared to the married folks, except for shopping. This was due to the desire to obtain food stuff, basic utilities and other essential functions at the office, church, hospitals, etc.

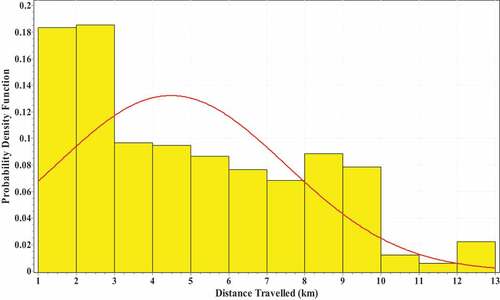

The distribution of travel distances covered by commuters is presented in . The histogram and distribution curve which skewed to the left indicated relatively high number of short distance trips measuring between 0 and 3 km within the metropolis. This was attributed to the unwillingness for long distance travel and social interactions among friends within neighbourhoods (Moslem et al., Citation2020; Yezli & Khan, Citation2020).

reveals the estimated average travelled distance at 4.5 km approximately with range and standard deviation of 12 and 3.0 km, respectively; which indicated high level of variances among trip lengths within the 16 km square radius of the metropolis. Other trips measuring between 3–10 km and 10–13 km had relatively low and lowest frequencies, respectively. This trend of trips distribution was attributed to the fear of contracting COVID-19 disease by commuters thereby avoiding long distance journeys in attempt to obey the stay at home rule as also observed in Yezli and Khan (Citation2020).

Results of the categorical analysis using contingency tables to examine dependencies of commuters’ social demographic characteristics on modal split and trip purposes are presented in , respectively.

Table 4. Statistical test of dependence between social demographic characteristics and modal split

Table 5. Statistical test of dependence between social demographic characteristics and trip destinations

Though there were variations between variables, reveal that there was no statistically significant dependence of commuters’ social demographic characteristics on modal split and trip destinations at 5% level of significance. The high range of p-values from 0.005 for a two tailed test indicated a strong disagreement with the conception hypothesis that; there is dependence between commuters’ socio demographic characteristics and the available mode choices as well as trip destinations. This trend revealed that, there was no obvious influential change in travel behaviour of commuters in Makurdi metropolis.

4. Summary and conclusion

The outbreak of COVID-19 in the 4th quarter of year 2019 in Wuhan city of China and its rapid spread across the world necessitated the introduction of some travel restriction policies by the federal and state governments of Nigeria to help curtail the spread of the deadly disease. This study examined the travel behaviour of flouting commuters in Makurdi metropolis amidst the travel restriction policy in the month of March 2020. About 496 questionnaires were administered to commuters travelling within the 16 km radius of the metropolis. Essential factors captured in the questionnaire included modal split and trip purposes as affected by the social demographic characteristics of commuters. Findings of the study revealed that the available mode choices in Makurdi metropolis included; minibuses, taxies, keke napep, okada, private cars and walking. The common trip destinations identified by the study included, hospitals, shopping malls and open markets, pubs for restaurants and bars, sporting and recreational centres, visitation to friends and associates as well as banks, offices, hotels for essential workers that had official permission to travel freely within the metropolis. There was no statistically significant level of dependence of commuters’ socio-demographic characteristics on modal split and trip destinations. Though the standard representative sample size for Makurdi was not used for this analysis, this trend revealed that, there was no obvious influential change in travel behaviour of commuters in Makurdi metropolis amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on findings of this study, the following recommendations were made;

(i) Concerned authorities should intensify efforts on creating more awareness about COVID-19 (or outbreak of any pandemic) and its deadly effects to instil fear in commuters and discourage travelling during the lockdown period to prevent spreading.

(ii) The government should distribute palliatives to households during the lockdown period to enable people remain indoors, or prior to the lockdown, allow people to acquire sufficient stuffs that can keep them indoors within a defined period of lockdown policy.

(iii) Law enforcement agents should be posted to the streets and highways to stop commuters from traveling during lockdown (stay-at-home) period to minimise the spread of communicable diseases such as COVID-19.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

P. T. Adeke

Adeke Paul Terkumbur is a lecturer and researcher at the Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Agriculture Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. He obtained his Bachelor of Engineering (B.Eng.) degree in Civil Engineering from the Federal University of Agriculture Makurdi, Nigeria in 2010. He proceeded for a Master of Science (M.Sc.) degree in Transport Planning and Engineering at the Institute for Transport Studies (ITS), University of Leeds, United Kingdom. Adeke is presently pursuing his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree in Civil Engineering (Highway and Transportation Engineering option) at the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria. His research interests include, transport planning and policies, transport modelling and simulations, highway structural analysis and design, pavement management and applications of Artificial Intelligent (AI) techniques in the analysis of transport systems. His professional membership include; Council for the Regulation of Engineering in Nigeria (COREN), Nigeria Society of Engineers (NSE) and Nigerian Institution of Civil Engineers (NICE).

References

- Adeke, P. T., Atoo, A. A., & Joel, E. (2018) A policy framework for efficient and sustainable road transport system to boost synergy between urban and rural settlements in developing countries: A case of Nigeria, 1st International Civil Eng. Conf. (ICEC 2018), Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria, 1( 1), 22–14.

- Adeke, P. T., Inalegwu, O. J., & Girgba, K. (2019). Prediction of bus travel time on urban routes without designated bus stops in Makurdi Town. Arid Zone Journal of Engineering, Technology and Environment, 15(2), 402–417. https://www.azojete.com.ng/index.php/azojete/article/view/83

- Adnan, M., Ahmed, S., Shakshuki, E. M., & Yasar, A. (2019). Determinants of Pro-environmental Activity-travel behaviour using GPS-based application and SEM Approach, The 10th International Conference on Emerging Ubiquitous Systems and Pervasive Networks, November 4 – 7, 2019, Coimbra, Portugal. 160, 109–117. Elsevier B. V., Netherlands.

- Koehl, A. (2020). Urban transport and COVID-19: Challenges and prospects in low- and middle–income countries. Cities and Health, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1791410

- Bajracharya, A. R., & Shrestha, S. (2017). Analyzing influence of socio-demographic factors on travel behavior of employees, A case study of Kathmandu metropolitan city. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 6(7), 111–119. https://www.ijstr.org/final-print/july2017/Analyzing-Influence-Of-Socio-demographic-Factors-On-Travel-Behavior-Of-Employees-A-Case-Study-Of-Kathmandu-Metropolitan-City-Nepal.pdf

- Bashingi, N., Hassan, M. M., & Das, K. D. (2019). Information communication technologies for travel in Southern African Cities. In L. Mohammad & R. A. El-Hakim (Eds.), Sustainable Issues in Transportation Engineering (pp. 114–127). Proceedings of the 3rd GeoMEast International Congress and Exhibition, Egypt 2019 on Sustainable Civil Infrastructures – The Official International Congress of the Soil-Structure Interaction Group in Egypt (SSIGE), Sustainable Civil Infrastructures. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34187-9_9

- Bhuiyan, M. A. A., Rifaat, S. M., Tay, R., & De Barros, A. (2020). Influence of community design and sociodemographic characteristics on teleworking. Sustainability, 12(14), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145781

- Ceder, A. (2007). Public transit planning and operation; theory, modelling and practice. Elsevier.

- Chen, J., & Li, S. (2017). Mode choice model for public transport with categorized latent variables. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2017(ID), 7861945. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7861945

- Chinazzi, M., Davis, J. T., Ajelli, M., Gioannini, C., Litvinova, M., Merler, S., Piontti, A. P., Mu, K., Rossi, L., Sun, K., Viboud, C., Xiong, X., Yu, H., Halloran, M. E., Longini, J. M., Jr., & Vespignani, A. (2020). The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. Science, 368(6489), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757

- De Vos, J. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behaviour. Transportation Research – Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5 (2020), 1–8.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100121

- Du, J., Rakha, H. A., Filali, F. and Eldardiry, H. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic impact on traffic system delay, fuel consumption and emissions. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology, 10(2), 184 – 196.

- Du, J., Rakha, H. A., Filali, F., & Eldardiry, H. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic impacts on traffic system delay, fuel consumption and emissions. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology, 10(2), 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtst.2020.11.003

- Essiet, U., & Mmom, P. C. (2014). Spatio-Temporal Variations in Urban Vehicular Emissions in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development, 7(4), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n4p272

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., & Ardeshiri, M. (2015). Modelling travel behaviour by the structural relationships between lifestyles, built environment and non-working trips. Transport Research Part A, 78, 506–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2015.06.016

- Excel, N. J. A., & Rietveld, P. (2001). Public transport strikes and traveller behaviour. Transport Policy, 8(4), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-070X(01)00022-1

- Flugel, S., Fearnley, N., & Killi, M. (2019). investigating observed and unobserved variation in the probability of ‘not travel’ as a behavioural response to restrictive policies. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 77(2019), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.10.008

- Gossling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gudmundsson, H., Hall, P. R., Marsden, G., & Zietsman, J. (2016). Sustainable transportation; indicators, frameworks, and performance management. Springer.

- Hendrickson, C., & Rilett, L. R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and transportation engineering. Journal of Transport Engineering, Part A: Systems, 146(7), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1061/JTEPBS.0000418

- Hotle, S., Murray-Tuite, P., & Singh, K. (2020). Influenza risk perception and travel-related health protection behavior in the US: Insights for the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 5(2020), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100127

- Hu, X., Wang, J., & Wang, L. (2013). Understanding the Travel Behavior of elderly people in the developing country: A case study of Changchun, China. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 96(2013), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.099

- Illesanmi, O., & Afolabi, A. (2020). Time to move from vertical to horizontal approach in our COVID-19 response in Nigeria. SciMedicine Journal, 2(2), 28–29. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-3

- Jain, D., & Tiwari, G. (2019). Explaining travel behaviour with limited socio-economic data: Case study of Vishakhapatnam, India. Travel Behaviour and Society, 15(2019), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.12.001

- Jirgba, K., Adeleke, O. O. & Adeke, P. T. (2020). Evaluation of the Accessibility of Public Transport Facilities by Physically Challenged Commuters in Ilorin Town, Nigeria, Arid Zone Journal of Engineering, Technology and Environment, 16(4), 651 – 662. https://azojete.com.ng/index.php/azojete/article/view/366

- Jirgba, K., Adeleke, O. O., & Adeke, P. T. (2020). Evaluation of the accessibility of public transport facilities by physically challenged commuters in Ilorin Town, Nigeria. Arid Zone Journal of Engineering, Technology and Environment, 16(4), 651–662. https://azojete.com.ng/index.php/azojete/article/view/366

- Malavenda, G. A., Musolino, G., Rindone, C., & Vitetta, A. (2020). Residential Location, Mobility, and Travel Time: A pilot study in a small-size Italian Metropolitan Area. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 2020(2020), 8827466. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8827466

- Mogaji, E. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on transportation in Lagos, Nigeria. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 6(2020), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100154

- Moslem, S., Campisi, T., Szmelter-Jarosz, A., Duleba, S., Md Nahiduzzaman, K., & Tesoriere, G. (2020). Best-worst method for modelling mobility choice after COVID-19: Evidence from Italy. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology, 12(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176824

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) (2020). Report on COVID-19, www.covid19.ncdc.gov.ng, Date: 31st March, 2020.

- NPC. (2006). National population commission, federal republic of Nigeria Official Gazette (Vol. 94, pp. 24). Nigeria.

- Ojo, O. O. S., & Awokola, O. S. (2012). Investigation of air pollution from automobiles at intersections on some selected major roads in Ogbomoso, South Western Nigeria. Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, 1(4), 31–35. http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jmce/papers/vol1-issue4/E0143135.pdf

- Okunlola, M. A., Lamptey, E., Senkyire, E. K., Serwaa, D., & Aki, B. D. (2020). Perceived myths and misconceptions about the novel COVID-19 Outbreak. SciMedicine Journal, 2(3), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-0203-1

- Ortuzar, J., De, D., & Willumsen, L. G. (2011). Modelling Transport (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Pan, X., & Zuo, Z. (2020). Exploring the role of utility-difference threshold in choice behavior: An empirical case study of bus service choice. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology, 9(2), 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijtst.2019.12.001

- Pratico, F. G., Vaiana, R., & Gallelli, V. (2012). Transport and Traffic Management by micro simulation models: Operational use and performance of roundabout. Urban Transport XVIII. WIT Transaction on the Built Environment, 128, 383–394. https://doi.org/10.2495/UT120331

- Schiller, P. L., Bruun, E. C., & Kenworthy, J. R. (2010). An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation – Policy Planning and Implementation. Earthscan.

- Shergold, I., Lyons, G., & Hubers, C. (2015). Future mobility in an ageing society – where are we heading? Journal of Transport and Health, 2(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2014.10.005

- Soltani, S. H. K., Sham, M., Awang, M., & Yaman, R. (2012). Accessibility for disabled in public transportation terminal, Asia Pacific International Conference on Environment-Behaviour Studies, Salamis Bay Conti Resort Hotel, Famagusta, North Cyprus, 7 – 9 December 2011.

- Somenahalli, S., & Shipton, M. (2013). Examining the distribution of the elderly and accessibility to essential services, 2nd conference of transportation research group of India. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 104, 942–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.189

- Tipaldi, M. A., Lucertini, E., Orgera, G., Zolovkins, A., Lauirno, F., Ronconi, E., Pisano, A., La Salandra, P. C., Laghi, A., & Rossi, M. (2020). How to manage the COVID-19 diffusion in the angiography suite: Experiences and results of an italian interventional radiology unit. SciMedicine Journal, 2(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-02-SI-1

- Veternik, M., & Gogola, M. (2017). Examining of correlation between demographic development of population and their travel behaviour. International Scientific Conference on Sustainable, Modern and Safe Transport, 192(2017), 929–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.06.160

- World Bank Group. (2020). Assessing the economic Impact of COVID-19 and Policy responses in Sub-saharan Africa – an analysis of issues shaping Africa’s economic feature (Vol. 21, pp. 2020). Washington DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1568-3

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2005). Air quality guidelines global update. Druckpartner Moser, Germany.

- Yezli, S., & Khan, A. (2020). COVID-19 social distancing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Bold measures in the face of political, economic, social and religious challenges. Travel Medicine and Infectious Diseases, 37(2020), 1 - 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101692

- Zalite, G. G., & Zvirbule, A. (2020). Digital readiness and competitiveness of the EU Higher education institutions: The COVID-19 pandemic impact. Emerging Science Journal, 4(4), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2020-01232

- Zwerts, E., Allaert, G., Janssense, D., Wets, G., & Witlox, F. (2010). How children view their travel behaviour: A case study from Flanders (Belgium). Journal of Transport Geography, 18(6), 702–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.10.002