Abstract

Service-learning methodology is designed to combine student learning with service to society, promoting project-based learning and establishing a fruitful interrelationship between both academic and social spheres. This teaching method is neither frequently employed on technical degrees nor particularly on civil engineering degrees, even though these degree courses open the door to professions with a strong vocation for public service. In this study, a project is reported that involved students following the third-year (sixth-semester) course in “Construction Methods” on the Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering, at the University of Burgos (Spain). A set of projects was proposed to solve small infrastructural shortcomings identified through surveys within various neighbourhoods of the city of Burgos (Spain), which were developed in cooperation with the residents. The results were very positive in many areas: the students acquired knowledge from various points of view and the neighbours appreciated the surveys and the urban planning on offer. In addition, the students’ academic results significantly improved, as well as their perceptions of the degree and their future professional careers.

1. Introduction

Service-learning methodology can be defined as an educational strategy in which training activities are combined and complemented with service to society. According to Cress (Cress, Citation2005), service-learning can also be defined as a form of education that matches a tangible need in a community with students participating in a learning experience. It is a fairly recent teaching strategy, the first works on which date back to the 1970s (Dolen et al., Citation1978; H.T. Cooper, Citation1977; Noley, Citation1977; Sigmon, Citation1974). Within the first stage of development, it is worth highlighting the work of Robert L. Sigmon (Sigmon, Citation1979), who defined service-learning as an experiential educational approach based on “reciprocal learning”. Sigmon suggested that learning arises from service activities and, in consequence, both the provider of the service and the recipients “learn” from the experience. According to Sigmon, service-learning can only take place when service providers and recipients both benefit from the activity.

Sigmon identified different teaching activities according to their weight in learning and service (Sigmon, Citation1994). Thus, for example, volunteer work or community service are learning activities in which service takes precedence over learning. In contrast, learning is more prominent than service during internship programs and field education (Bowie & Cassim, Citation2016).

The service-learning methodology combines student learning with service to society and promotes project-based learning. In addition, it favours a fruitful interrelation between academic and social spheres. However, it is a more comprehensive teaching methodology than project-based learning, as the latter does not necessarily involve doing useful work for the community, whereas the service-learning methodology does (Frank et al., Citation2003; Hung et al., Citation2012; Kokotsaki et al., Citation2016; Land & Greene, Citation2000).

To date, a large number of service-learning experiences have been reported. A substantial number describe teaching experiences at universities and other Higher Education institutions. However, it should be noted that a relevant number of them have taken place at secondary schools (Baecher & Chung, Citation2020; Baldwin et al., Citation2007; Camus et al., Citation2022; Carrington & Saggers, Citation2008; Chan et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Conner, Citation2010; Domange & Carson, Citation2008; Hullender et al., Citation2015; J.R. Cooper, Citation2014; Kenneth et al., Citation2022).

In most experimental degrees (like architecture, engineering and medical-related degrees, among others), the number of service-learning experiences is lower. This is especially relevant, since the interaction between students and their society is at its most intense in these degrees. It is worth highlighting some particularly interesting experiences in medical schools (Brush et al., Citation2006; Buckner et al., Citation2010; Cashman & Seifer, Citation2008; Seif et al., Citation2014; Seifer, Citation1998), in which students offered patient care services through service-learning projects.

In the field of engineering, relatively few teaching experiences have been reported on the use of this methodology (Bielefeldt et al., Citation2010; Borgi & Zitomer, Citation2008; Brush et al., Citation2006; Huff et al., Citation2016; Seifer, Citation1998; Shelby et al., Citation2013; Tsang et al., Citation2001). The first publications date back to the 1990s and most focused on the description of experiences based on the implementation of engineering projects for society and, in some cases, for developing countries.

Within the field of engineering, it is worth highlighting the EPICS (Engineering Projects in Community Service) teaching program developed at Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN, USA) that began in 1995 (Coyle et al., Citation2005; Jamieson et al., Citation2001; Oakes et al., Citation2000). In this program, engineering students were awarded academic credits for developing long-term and long-range projects that solved problems for local community organizations. Each project work team was formed of students studying for different degrees, such as Electrical, Computer, Mechanical, Civil, Aerospace, Industrial and Materials Engineering as well as from Computer Science, Chemistry, Sociology, Nursing, Visual Design, English, and Education. The work team included students from different courses (from freshman to senior) and the duration of the projects was up to 3 years, which is sufficient to develop projects with social and academic impact, as well as favouring deeper interrelations between students from different degrees and academic years.

This teaching program has allowed the development of many works of great pedagogical interest (Oakes et al., Citation2019; Oakes & Zoltowski, Citation2014; Qian et al., Citation2012) and has served as inspiration for many other works around the world (Kirsch, Citation2018; Lo, Chan et al., Citation2019; Lo, Ip et al., Citation2019; Naik et al., Citation2020; Scherrer & Sharpe, Citation2020; Vandersteen, Citation2011; Williams & Figueiredo, Citation2014).

A very important reference in the field of service-learning in engineering is Hong Kong Polytechnic University, which since 2010 has adopted service-learning as an institutional strategy, even having a service-learning and leadership office. Since then it has carried out a large number of service-learning projects in many different locations (Hong Kong, Mainland China, Taiwan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Kyrgyzstan and Rwanda, among others; Camus et al., Citation2022; Chan et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Kenneth et al., Citation2022).

Within the more particular field of civil engineering, it is notable that an especially low number of teaching experiences have been published (apart from the ones mentioned above), although it is an area of engineering with strong involvement in society (Dewoolkar et al., Citation2009, Citation2011; El-Adaway et al., Citation2015). The first papers were published at the start of the 21st century and most of them have focused on the development of construction and civil engineering projects.

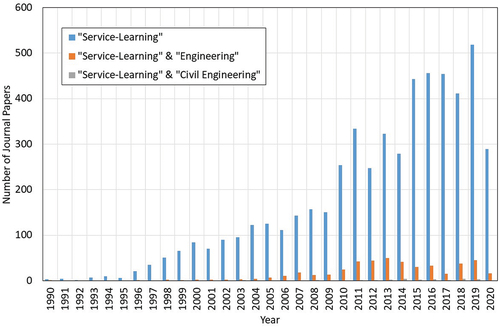

shows the number of publications since 1990 related to service-learning methodology, both in general and in the field of engineering and civil engineering. The data were taken from the ISI Web of Knowledge.

The bibliometric study revealed that 8.5% of the papers published in JCR indexed journals were labelled as “Engineering”, among which only 5.0% were labelled as “Civil Engineering”, which represents only 0.4% of the total number of papers published in JCR indexed journals.

However, service-learning methodology is particularly useful and positive in civil engineering degrees, both for undergraduate and master’s students. The skills and knowledge that students acquire have strong practical applications. In general, students following the last two years of an undergraduate degree and students studying for the master’s degree have already acquired sufficient technical knowledge to implement simple actions in their environment. On the contrary, their experience is weaker in aspects related to the identification of real problems and interaction with users of infrastructures, among others. Nevertheless, students are expected to acquire these skills during their stay at university, as underlined in the subject teaching guides.

Service-learning methodology is implemented through the development of brief civil-engineering projects in a neighbourhood, which are intended to satisfy the felt needs of residents.

Students can acquire a large variety of transversal skills through service-learning projects, which are essential for their future professional performance. Among them, it is worth highlighting some instrumental skills, such as capabilities for analysis and synthesis, information management, and decision-making. They also allow the development of personal skills, such as teamwork, interpersonal relationship skills and ethical commitments, among others. In addition, these projects enable the acquisition or enhancement of some systematic skills, such as autonomous learning, adaptation to new situations, creativity and awareness of environmental issues (Kenneth et al., Citation2022).

The main goal of this project is to explore the teaching potential of the service-learning methodology on the Degree of Civil Engineering. Some analysis is also offered of how the project can help to improve the motivation of students and societal perceptions of civil engineers.

The structure of this paper is as follows: an overall description of the service-learning project and the methodology is presented in Section 2; the descriptions of the projects that the students prepared can be found in Section 3; the assessments are discussed in Section 4; the impact of each project is discussed in Section 5; and, finally, the conclusions are presented in Section 6.

2. Overall description of the service-learning project and methodology

The Service-Learning project described here was titled “Sustainable structures and constructions that improve life in the neighbourhoods of the city of Burgos (Spain)”. It was developed as part of the subject “Construction Methods”, taught during the sixth semester of the Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering at the University of Burgos (Spain). The main goal of this subject is to provide expertise to the students on the different construction procedures that are commonly used in civil engineering, as well as the technology applied to each one. Additionally, in this subject, students are taught to choose the most appropriate construction solution for each situation, from both a technical and an economic point of view and both in construction and at the project level.

By the sixth semester of the course, students have already gained sufficient technical knowledge for planning small-scale construction projects, having studied some subjects relating to construction technology, such as Reinforced Concrete, Steel Structures, Road Engineering, Hydraulics, etc.

The aim of this project was to integrate students and to involve them in technical projects with the fundamental goal of identifying where civil infrastructure could be improved and to plan those improvements within neighbourhoods and districts of Burgos whose past urban development had very different needs from those of today. The project lasted four months.

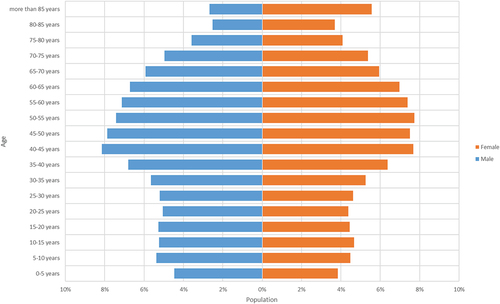

Burgos is a medium-sized city (with a population of 175,821 inhabitants in 2019, see, Figure ), located in the north of Spain, in the Autonomous Community of Castilla and León. It is also a compact city, with a population density of 1,642.27 inhabitants per km2 (4,253.46 inhabitants per sq. mi) in 2019 (source: National Statistics Institute of Spain).

The population of Burgos is principally adults. The mean age of the population, 43 years for men and 47 years for women, is 45 years old. The most prevalent age range of both men and women is between 40–45 years (). The older population is mainly concentrated in the most central neighbourhoods of the city, while the younger population is concentrated in the suburbs. The city’s population pyramid has changed a lot over recent years, as have the needs for the facilities and the services that they demand, which is aligned with the extrinsic purpose of the project: to identify civil infrastructure needs within the neighbourhoods and the districts of the city of Burgos.

A total of 16 students participated in this project. Each group was divided into four groups of four students and each group had to develop and to plan a constructive project addressing some urban development needs within the four districts of the city of Burgos.

The investment cost was limited to €100,000.00 per constructive project, so that the students could plan creative solutions, especially valuing their relevance to the needs of the neighbourhood, sustainable construction and creativity.

From a training point of view, this project seeks to instil values of Social Responsibility among students linked to construction and urban planning, as well as values associated with environmental protection and the efficient use of resources (including public resources). On the other hand, another of the priority lines of the project is the interaction between students and social agents most directly involved in the neighbourhoods, in such a way that symbiosis is established between the technical capacities of the former and the social needs of the latter. Furthermore, this interaction improves the perception of the public service work of the University of Burgos.

The specific objectives of the project from the point of view of service to society were as follows:

Identify the urban infrastructure needs within the neighbourhood. To do so, students were expected to hold meetings with local agents (NGOs, neighbourhood associations, etc.) to gather information. They also had to administer surveys to the residents of the neighbourhood to obtain information on their needs.

Write a technical report demonstrating three possible proposals for action, including a short description of each one and an initial budget. This document should include a short cost-benefit analysis and an assessment of each action that is proposed.

Development of a small-scale construction project to address the solution that was finally selected from among the three above-mentioned proposals for action.

Once selected, the project was finally presented to fellow students.

For the development of the project, the students were encouraged to obtain relevant information from public bodies and institutions, as well as through neighbourhood surveys or interviews with social agents, such as neighbourhood associations, NGOs and religious institutions, etc.

shows the survey that the students administered to neighbours and local agents within each district:

Table 1. Survey designed by the students and administered to neighbours and social agents within each neighbourhood

The service-learning project approach affords an opportunity for students to work on the following skills and capabilities:

Identification of problems and proposed solutions.

Teamwork.

Interaction with social agents, to gather information and to satisfy their needs.

Use of technical knowledge to solve real problems.

Public presentation and discussion of the project, so that the students can develop their capability for summarization in the presentation.

Development of social responsibility and public service values, which are essential for a civil engineer.

Use of environmental and economic efficiency criteria in projects, prioritizing recycling and reuse, as well as introducing the basic principles of the circular economy.

3. Description of the project

A detailed description follows of each project that the students developed in the form of civil-engineering plans.

3.1. Project 1: surface level car parking close to Burgos castle

The first project was focused on District I (North District) of the city of Burgos. This district includes the city centre and an area with the most emblematic buildings of the city and with high levels of tourism, such as Burgos Cathedral, the Plaza Mayor [main square], the Museum of Human Evolution and the Castle viewing point. This district is home to many older people and has other newer residential neighbourhoods with larger populations of younger people.

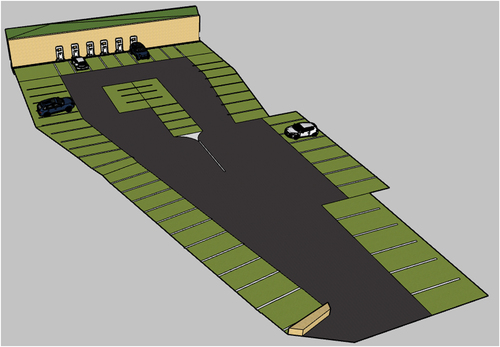

One of the most relevant weaknesses that residents mentioned in the surveys was the lack of surface parking, especially in the neighbourhood near the Castle. It is a neighbourhood of old houses that have no parking lots and there is also increasing demand for parking from tourists, visitors and neighbours as well ().

The construction project was focused on the design of a surface parking lot, with parking for 70 vehicles. Its plan included specific spaces with recharging points for electric vehicles.

The project included the design of the electrical and lighting installations, etc., as well as the complete urbanization of the parking lot and some boundaries (i.e., walls).

3.2. Project 2: intergenerational park

The second project concerned service provision within District II (West District) of the city of Burgos. A district that hosts some of the most important facilities in the city of Burgos, such as the University of Burgos, the Monastery of Las Huelgas Reales, and Parral Park (the largest urban green space in the city). It is a neighbourhood in expansion, with important new residential areas and, therefore, with significant numbers of children. However, it hardly has any outdoor parks for them. There is also a significant population of older people.

Neighbours specifically demanded playgrounds for both children and for the elderly where grandparents can perform outdoor physiotherapy exercises adapted to their age and, at the same time, can watch over their grandchildren playing in the children’s playground.

The project was focused on the design of an intergenerational park located within Parral Park, with two adjoining areas, one for children and another for the elderly, and some common facilities, such as benches and water fountains.

It included the design of the water facilities, lighting, etc., as well as the complete urbanization of both recreational areas ().

3.3. Project 3: Actions at bus stops and raised pedestrian crossings

The activities of the third project were in District III (Eastern District) of the city of Burgos. It is the most populous district in the city, housing almost one-third of the total population of the city. In addition, it is a neighbourhood with a high population density. Mobility in this district is difficult and pedestrian and vehicle circulation and coexistence can also be arduous. In this sense, residents have, for several years now, been demanding small improvement actions to refine the coexistence between road traffic and pedestrians ().

The results of the surveys administered to residents emphasized a need for improvements to some bus stops and the implementation of raised pedestrian crossings, assuring pedestrian safety, and facilitating the use of public transport.

The project focused on the design of two actions. The first one was to improve the functionality of some bus stops, removing some parking spaces and modifying the sidewalk to give direct access to buses, without obstacles. The second one was the design of four raised pedestrian crossings in other streets of the neighbourhood, to improve the safety of pedestrians when crossing and to serve as traffic-calming measures on these streets.

3.4 Project 4: bike-lane on the railway boulevard

The fourth project was focused on District IV (South District) of the city of Burgos. It is a district that has undergone a vital transformation over recent years, following the closure of a railroad shunting yard and the city’s main train station. A few years ago, the railroad was diverted to run outside the city, constructing a new train station on the outskirts and freeing up large lots of urban land for the development of new residential areas. In addition, the old railroad has been converted into a boulevard, with lanes for private vehicles, taxis, buses, and wide sidewalks. Recently created urban areas and old neighbourhoods coexist in the district ().

One of the demands of this neighbourhood is the possibility of having a bike lane that, in addition, connects with the network of bike lanes within the city.

The project was focused on the design of a section of the bike lane on the boulevard, using part of the wide space for pedestrians. The design of the section was approximately 1 km in length.

4. Assessment

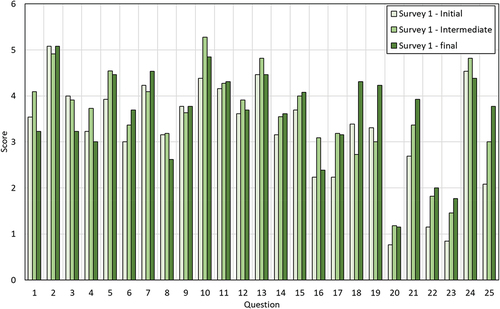

One of the essential aspects of this service-learning project is to evaluate its impact, both on the students and on the neighbours and their districts. Two surveys were first administered to all participating students, in order to evaluate the way in which the project had influenced them. The first survey consisted of 25 questions of a general scope, related to their perceptions of the degree in Civil Engineering, the subject (Construction Methods) and the profession (Civil Engineering). Of these, the first 17 were directly related to the degree and the subject, while the last eight were related to the profession. The second survey, with a total of 14 questions, was focused on their perceptions of this service-learning project.

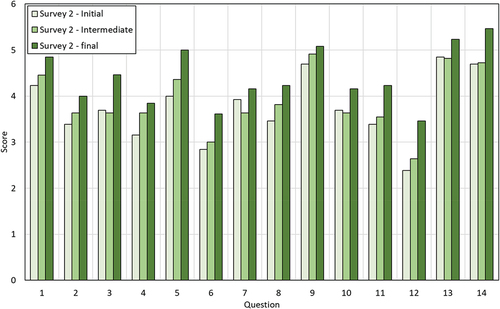

The questions were composed in accordance with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004). The same two surveys were repeated three times: the first one on the first day of class, once the project had been presented to the students; the second one mid-way through the course, and the third one after the end of project. The time interval between surveys was two months. In this way, it was possible to determine how the perceptions of the degree, the subject and the profession had changed among students and to ascertain the degree of satisfaction and motivation that the project had generated. show both surveys.

Table 2. First survey

Table 3. Second survey

Some meetings with social agents of the city (Burgos City Council, NGOs, etc.) were held before and after the project, in order to analyze the impact of this service-learning project on society and jobs. Once the projects had been fully documented, Burgos City Council was informed and given the final project documentation, so that they could be publicized in the city. In addition, the projects were exhibited at the University of Burgos, so that both students and neighbours could view them ().

5. Discussion

A detailed analysis of the impact of this project is discussed below, both from the point of view of the students (from the perspective of their learning and training) and the neighbours (from the perspective of the service).

First, the results of the surveys administered to the students are shown in .

Next, show the main statistical parameters extracted from .

Table 4. Main statistical results of Survey 1

Table 5. Main statistical results of Survey 2

The results obtained in this service-learning project were very satisfactory. First, the results of Survey 1 revealed an improvement in the perception of the degree, the subject, and the profession, which was up 10.3 % in the case of the intermediate survey and 11.3% in the case of the final survey. A particular analysis of the perception of the degree and the subject (questions 1 to 17) revealed somewhat less improvement, reaching only 3.7% at the end of the semester. However, a strong improvement in the perception of the profession can be observed among the students, which was 13.8% in the intermediate survey and 36.1% at the end. The service-learning project therefore facilitated student understanding and appreciation of the public service dimension of the profession.

Student responses to the second set of questions (questions 18–25) not only depended on this service-learning project and on how the subject (Construction Methods) was taught, but they also depended on many other external factors. In this sense, this educational project significantly helped to improve perceptions of the profession that the students had chosen. This fact shows that, in general terms, traditional teaching methodologies, commonly used in civil engineering schools, are not sufficient to promote the spirit of public service that is, without a doubt, integral to the civil engineering profession.

The results of Survey 2 showed very satisfactory acceptance of this project among the students. The perception has always been very positive (Survey 2 has higher average values than Survey 1, in all cases). Furthermore, students perceptions have improved over time, with an improvement in the perception of 4.0% in the case of the intermediate survey and 17.9% in the case of the final survey.

At the end of the course, a debate was held between the students and the teachers responsible for the course, so that the students could give their opinion on the service-learning project developed. It was an interesting and enriching experience, as it provided very useful information for future projects.

One of the most interesting conclusions of the discussion was that the students received the project in a satisfactory way and improved their perception of the degree, the subject and the profession. The students clearly stated that this is an activity that interests them, and that it should be implemented in more subjects. The opinions expressed by the students in the discussion were very much in line with the results of the surveys.

On the other hand, it has been observed during the course that students have been more motivated with the subject than in previous years. Students worked more actively during the lessons, asked more questions, showed more interest in the subjects, etc. On quite a few occasions, students asked questions directly related to their project. From an academic point of view, students’ grades were better than in previous years.

On the other hand, the warm reception of the project among neighbours was palpable. The public, through the meetings with those responsible for the project, verified that the work was in harmony with the needs of the neighbourhood and that the plans offered acceptable solutions to the problems that had been detected. The neighbours felt part of the project and their interactions with the students were very enriching for both parties. They recognized the social endeavours of the University and the strong public service vocation of the degree in civil engineering. In turn, Burgos City Council showed interest in the project plans and has undertaken to consider their inclusion in future urban actions.

The main limitation of this work is that the number of students who could participate was small, because the subject “Construction Methods” of the Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering at the University of Burgos (Spain) has a low number of students. Therefore, the results obtained are not statistically robust. However, this fact has the advantage that it has been possible to carry out a very detailed monitoring of each of the works and of each of the students.

6. Conclusions

A teaching experience at the University of Burgos (Burgos, Spain) has been reported on the implementation of the service-learning methodology as part of a civil-engineering degree subject.

This teaching experience was part of the “Construction Methods” subject, in the third year, sixth semester, of the degree in Civil Engineering. At this time, the students have acquired sufficient technical knowledge to be able to develop and plan small construction projects.

The project involved the planning of four proposed actions (i.e., specific projects) in four neighbourhoods of the city of Burgos. Among the activities to be developed by the students, they were expected to interact with the neighbours and the social agents of each district, in order to identify their needs. They then planned some small construction projects (adapted to their technical capacities) that responded to the felt needs of the neighbours.

The experience has been very positive for both parties. For the students, within the scope of their learning and training, the projects have allowed them to work on some competencies that are neither usually nor regularly developed in the classroom, such as the ability to manage information, decision-making, skills in interpersonal relationships, ethical commitment, creativity and sensitivity towards environmental issues. The results of the surveys administered to the students during the project have clearly shown improved perceptions of the degree, the subject and, above all, their professional future as civil engineers.

Within the scope of service, the teaching experience has also been very positive for the neighbourhoods. The image of the University and the profession of civil engineering among residents has been improved. The projects have also been very positively valued. In this sense, Burgos City Council has acknowledged receipt of the project plans with interest, expressing a commitment to their inclusion in future urban actions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baecher, L., & Chung, S. (2020). Transformative professional development for in-service teachers through international service-learning. Teacher Development, 24(1), 33–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2019.1682033

- Baldwin, S. C., Buchanan, A. M., & Rudisill, M. E. (2007). What teacher candidates learned about diversity, social justice, and themselves from service-learning experiences. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(4), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487107305259

- Bielefeldt, A. R., Paterson, K. G., & Swan, C. W. (2010). Measuring the value added from service learning in project-based engineering education. International Journal of Engineering Education, 26(3), 535–546.

- Borgi, J. P., & Zitomer, D. H. (2008). Dual-team model for international service learning in engineering: Remote solar water pumping in Guatemala. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 134(2), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(2008)134:2(178)

- Bowie, A., & Cassim, F. (2016). Linking classroom and community: A theoretical alignment of service learning and a human-centered design methodology in contemporary communication design education”. Education as Change, 20(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2016/556

- Brush, D. R., Markert, R. J., & Lazarus, C. J. (2006). The relationship between service learning and medical student academic and professional outcomes. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 18(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1801_3

- Buckner, A. V., Ndjakani, Y. D., Banks, B., & Blumenthal, D. S. (2010). Using service-learning to teach community health: the Morehouse school of medicine community health course. Academic Medicine, 85(10), 1645–1651. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f08348

- Camus, R. M., Ngai, G., Kwan, K. P., & Chan, S. C. F. (2022). Transforming teaching: service-learning’s impact on faculty. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 26(2), 49–63.

- Carrington, S., & Saggers, B. (2008). Service-learning informing the development of an inclusive ethical framework for beginning teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(3), 795–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.09.006

- Cashman, S. B., & Seifer, S. D. (2008). Service-learning - An integral part of undergraduate public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(3), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.012

- Chan, S. C. F., Ngai, G., & Kwan, K. P. (2019). Mandatory service learning at university: Do less-inclined students learn from it? Active Learning in Higher Education, 20(3), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417742019

- Chan, S. C. F., Ngai, G., Yau, J. H. Y., & Kwan, K. P. (2021). Impact of international service-learning on students’ global citizenship and intercultural development. International Journal of Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement, 9(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.37333/001c.31305

- Conner, J. O. (2010). Learning to unlearn: How a service-learning project can help teacher candidates to reframe urban students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1170–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.02.001

- Cooper, H. T. (1977). Service-Learning through internships and research for state government. New Directions for Higher Education, 18(18), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.36919771806

- Cooper, J. R. (2014). Ten years in the trenches: Faculty perspectives on sustaining service-learning. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913513721

- Coyle, E., Jamieson, L., & Oakes, W. (2005). EPICS: engineering projects in community service. International Journal of Engineering Education, 21, 1–13.

- Cress, C. M. (2005). “What is service-learning?” in learning through service: a student guidebook for service-learning across disciplines (pp. 716). (716). (C. M. Cress, P. J. Collier, & V. L. Reitenauer, edited by). Stylus.

- Dewoolkar, M. M., George, L., Hayden, N. J., & Rizzo, D. M. (2009). Vertical integration of service-learning into civil and environmental engineering curricula. International Journal of Engineering Education, 25(6), 1257–1269.

- Dewoolkar, M. M., Porter, D., & Hayden, N. J. (2011). Service-learning in engineering education and heritage. International Journal of Architectural Heritage, 5(6), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583051003792864

- Dolen, C. A., Smith, J. S., & Edens, M. I. (1978). Service learning: A bridge between the university and the community. Volunteer Administration, 11(1), 7–12.

- Domange, E., & Carson, R. L. (2008). Preparing culturally competent teachers: Service-learning and physical education teacher education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27(3), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.27.3.347

- El-Adaway, I., Pierrakos, O., & Truax, D. (2015). Sustainable construction education using problem-based learning and service-learning pedagogies. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 141(2), 05014002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000208

- Frank, M., Lavy, I., & Elata, D. (2003). Implementing the project-based learning approach in an academic engineering course. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 13(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026192113732

- Huff, J. L., Zoltowski, C. B., & Oakes, W. C. (2016). Preparing engineers for the workplace through service learning: perceptions of EPICS alumni. Journal of Engineering Education, 105(1), 43–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20107

- Hullender, R., Hinck, S., Wood-Nartker, J., Burton, T., & Bowlby, S. (2015). Evidences of transformative learning in service-learning reflections. Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 15(4), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v15i4.13432

- Hung, C. M., Hwang, G. J., & Huang, I. (2012). A project-based digital storytelling approach for improving students’ learning motivation, problem-solving competence and learning achievement. Educational Technology & Society, 15(4), 368–379.

- Jamieson, L., Oakes, W., & Coyle, E. (2001). “EPICS: Documenting service-learning to meet EC 2000”. 31st Annual Frontiers in Education Conference. Impact on Engineering and Science Education. Conference Proceedings (Cat. No. 01CH37193), 1, T2A–1.

- Kenneth, W. K. L., Ngai, G., Chan, S. C. F., & Kwan, K. P. (2022). How students’ motivation and learning experience affect their service-learning outcomes: a structural equation modeling analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 825902. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.825902

- Kirsch, N. (2018). Service learning in engineering education. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 17(2), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2018.022511244

- Kokotsaki, D., Menzies, V., & Wiggins, A. (2016). Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improving Schools, 19(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480216659733

- Land, S. M., & Greene, B. A. (2000). Project-based learning with the world wide web: A qualitative study of resource integration. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02313485

- Lo, K. W., Chan, S., Ngai, G., Kalenzi, J., Sindayehaba, P., & Habiyaremye, I. (2019). “From beneficiary to community leader: capacity building through a renewable energy project in Rwanda”. 2019 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), pp. 1–7.

- Lo, K. W., Ip, A. K., Lau, C. K., Wong, W. S., Ngai, G., & Chan, S. (2019). Integrating majors and non-majors in an international engineering service-learning programme: course design, student assessments and learning outcomes. In D. T. L. Shek, G. Ngai, & S. C. F. Chan (Eds.), Service-learning for youth leadership. quality of life in Asia (Vol. v, pp. 12). Springer.

- Naik, S., Bandi, S., & Mahajan, H. (2020). Introducing service learning to under graduate engineering students through EPICS. Procedia Computer Science, 172, 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.05.090

- Noley, S. (1977). Service-Learning from the agency’s perspective. New Directions for Higher Education, 18(18), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.36919771810

- Oakes, W. C., Coyle, E. J., & Jamieson, L. H. (2000). “EPICS: a model of service learning in the engineering curriculum” Proceedings, ASEE Conference and Exhibition, Session 3630, 5.281, 1–14.

- Oakes, W. C., Khalifah, S., Sigworth, C., Fuchs, P., & Lefebvre, A. (2019). EWB-USA and EPICS: academic credit, community impact, and student learning. International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering, Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship, 14(3), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.24908/ijsle.v14i3.13199

- Oakes, W., & Zoltowski, C. (2014). “Using community engagement to teach engineering and computing”. 2014 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) Proceedings, v. 1–3.

- Qian, C., Zoltowski, C., & Oakes, W. (2012). “Collaborating interaction design into engineering projects in community service (EPICS)”. 2012 Frontiers in Education Conference Proceedings, v. 1–6.

- Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2004). UWES. Utrecht work engagement scale. In Occupational health psychology unit. Utrecht University 60 .

- Scherrer, C. R., & Sharpe, J. (2020). Service learning versus traditional project-based learning: a comparison study in a first year industrial and systems engineering course. International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering, Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.24908/ijsle.v15i1.13569

- Seif, G., Coker-Bolt, P., Kraft, S., Gonsalves, W., Simpson, K., & Johnson, E. (2014). The development of clinical reasoning and interprofessional behaviors: Service-learning at a student-run free clinic. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(6), 559–564. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.921899

- Seifer, S. D. (1998). Service-learning: Community-campus partnerships for health professions education. Academic Medicine, 73(3), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199803000-00015

- Shelby, R., Ansari, F., Patten, E., Pruitt, L., Walker, G., & Wang, J. (2013). Implementation of leadership and service learning in a first-year engineering course enhances professional skills. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29(1), 85–98.

- Sigmon, R. L. (1974). Service-Learning in North-Carolina. New Directions for Higher Education, 6(6), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.36919740605

- Sigmon, R. L. (1979). Service-learning: three principles. Synergist. National Center for Service-Learning, ACTION, 8(1), 9–11.

- Sigmon, R. L. (1994 Council of Independient Colleges). . Seving to learn, learning to serve. Linking service with learning. Council for Independent Colleges Report.

- Tsang, E., Van Haneghan, J., Johnson, B., Newman, E. J., & Van Eck, S. (2001). A report on service-learning and engineering design: Service-learning’s effect on students learning engineering design in ‘Introduction to Mechanical Engineering’. International Journal of Engineering Education, 17(1), 30–39.

- Vandersteen, J. (2011). Adaptive Engineering. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 31(2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610396694

- Williams, B., & Figueiredo, J. (2014). From academia to start-up: a case study with implications for engineering education. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog, 4(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v4i1.3236