?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study complemented the debate for a better outdoor residential experience but gave a perspective from a developing country, using Ewet housing estate in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria, as a case study. Combining field observation with a questionnaire, data obtained from 150 houses was analysed using descriptive statistics complemented with regression analysis. The results showed that over 60% of the houses were of high quality, however, they were overshadowed by the surrounding lacklustre open space areas. The visual quality of the organisation of the landscape elements had a very strong positive relationship with contribution to amenity value of the neighbourhood. Preference for outdoor activities with recreation, motivation to beautify the premises, and to have a good setting for the house all appeared as positive factors of poor quality development of a residential site. Non-availability of good site design/lack of specification by the housing authority for site development, and inadequate space and site problems, were found to be the major constraints affecting residential site development. The awareness factor had a strong positive relationship with the quality of site development. The study concluded by suggesting a conceptual foundation for improving the process and quality of residential site development in developing countries.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study complemented the debate for a better outdoor residential experience but gave a perspective from a developing country, using Ewet housing estate in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria, as a case study. Combining field observation with a questionnaire, data obtained from 150 houses was analysed. The results showed that over 60% of the houses were of high quality, however, they were overshadowed by the surrounding lacklustre open space areas. Preference for outdoor activities with recreation, motivation to beautify the premises, and to have a good setting for the house all appeared as positive factors of poor quality development of a residential site. Non-availability of good site design/lack of specification by the housing authority for site development, and inadequate space and site problems constituted the major constraints affecting residential site development. The study concluded with a conceptual foundation for improving the process and quality of residential site development in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Housing is one of the most essential human necessities. Its value has impacted the gross domestic product (GDP) of some advanced economies (Anthony, Citation2022: Chien & Liu, Citation2022) and is a major source of employment and satisfaction for citizens in developing countries (Adabre et al., Citation2022). This may not be unconnected to the reason successive housing policies in developing countries in Asia (Wakely, Citation2022), Africa (Odoyi & Riekkinen, Citation2022) and Europe (Shahab et al., Citation2021) have centred on how their citizens can have unrestricted access to a qualitative housing environment. The quality of housing environment, as one of the key elements of housing, has been recognised to have a substantial influence on the well-being of residents, their living standard and productivity, as well as environment sustainability (Coley et al., Citation2013; Li & Wu, Citation2013; Tao, Citation2015). In the same vein, another study (Yip et al., Citation2017) found that both the house and the environment in which it is located have a direct influence on human life. This suggests that as much attention is given to the house in a residential setting, the same should be given to its immediate environment—the outdoor space.

Already, several studies have given different views on the importance of outdoor space in residential housing settings. For example, Fogh and Saransi (Citation2014) claimed that incorporating a residential outdoor oriented approach into an architectural scheme can be a very beneficial step towards the systematic design of housing. Designs that include high-quality outdoor areas within homes can improve both the housing and the quality of life of the residents (Burton et al., Citation2014). Likewise, it has been reported that housing conditions, including outdoor space, have an impact on a person’s health (Olukolajo et al., Citation2013). The social class of residents is greatly influenced by the general residential environment, the quality of the housing stock, and the neighbourhood (Ilesanmi, Citation2012).

Besides, outdoor space is a crucial component of every neighbourhood, community, and urban design; as a result, outdoor space design is a crucial component of every building design (Gray, Citation2013). Ashley (Citation2021, January 21) claimed that a perfect home has four vital constituents: high-quality design, a healthy environment, high-quality construction, and a sense of community. This demonstrates how leveraging communal space is an essential tactic for creating housing products.

It has also been argued that the outdoor environment is just as important as the indoor environment (Coolen & Meesters, Citation2012). When private residential outdoor areas are incorporated into the interior living areas of a home, they could be viewed as “outer rooms” (Gray, Citation2013). This sounds plausible, as these outdoor areas, as perceived by another author (Farida, Citation2013), are a natural extension of the indoors. Outer spaces, according to Afon and Adebara (Citation2019), are essential components of the city and they have a significant impact on sustainable urban growth. Even though good quality spaces bring a sense of comfort and safety, outdoor areas also serve as neat, adequately-maintained spaces for a variety of social undertakings, as expressed by multiple authors (Farr, Citation2011; Hadavi et al., Citation2015; Kaźmierczak, Citation2013; Li & Wu, Citation2013). Despite the numerous works of literature stressing the importance of high-quality housing and a comfortable residential environment, it appears that adequate attention has not been paid to certain distinct and subjective characteristics associated with homeowners and their lifestyles.

The immediate environment surrounding any housing site is the framework within which a house situates and this influences homeowners’ lifestyle. The quality components of the external framework depict a cozy residential quarter that makes and promotes a healthy residential lifestyle and living standard. It is worthy to note that outdoor residential space has been linked to certain subjective peculiarities such as people’s attachment and choices in many perspectives (Eusuf et al., Citation2014; Farida, Citation2013; Lai et al., Citation2014; Y. Li et al., Citation2021; Mohamed et al., Citation2014; Ramyar et al., Citation2019). However, the complex nature of homeowners is seen in the subjectivity of their choices, preferences, differences in the design and composition of housing, cultural idiosyncrasies and experiences, and location. This creates the need for a wider understanding of outdoor residential site development.

Previous reports have stated many factors that contribute to an undesirable housing environment. They include, among other factors, the poor attitude and uncoordinated activities of some planning consultants and planning authorities. Furthermore, the attitude of some home owners towards the development of their residential sites plays a vital role in the emerging character of the housing environment. Many home owners give little attention to the quality of the outdoor treatment of their homes as a key factor in the appreciation of the house’s value.

Another factor that may affect housing appreciation is the inability of governments in developing countries to meet citizens’ expectations of quality housing environments. Expectedly, many housing programmes of the government have been chastised for failing to meet housing adequacy (Mukhija, Citation2004). In certain developing countries like Nigeria, the government’s interest in providing effective housing programmes is not well understood. In another view, inadequate monitoring and evaluation of housing policy execution have facilitated failed housing programmes in the country, as referenced in the 1991 Nigerian National Housing Policy (Federal Republic of Nigeria, Citation1991). This position has been buttressed by a study (Obashoro-John, Citation2002) that reported that, due to the lack of effective programme evaluation in Nigeria, examining the actual housing programmes in the country is thorny.

From the foregoing, and in corroboration with Ibem et al. (Citation2015), it can be extrapolated that evaluation research pertaining to outdoor residential space in public housing in Nigeria as a developing country is inadequate and as extant studies (Ibem & Aduwo, Citation2013; Jiboye, Citation2010; Olatubara & Fatoye, Citation2007) gave more concerns to the design and construction of housing units than their outdoor environments. Interestingly, Nigeria, being the biggest black nation among the developing countries, has received a level of attention in the study of some aspects of housing programmes and outdoor residential space (Akeju & Andrew, Citation2007; Ibem et al., Citation2013; Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015; Jegede et al., Citation2020; Jiboye, Citation2010; Mohit & Iyanda, Citation2016; Offia et al., 2013; Oswald et al., Citation2003), but most of the studies focused on the south-west geopolitical zone of the country and some treated outdoor space at a superficial level. Some shortcomings that bear upon the focus, usefulness and coverage of the results for factual decisions on the performance of public housing programmes in this country exist.

Particularly, inadequate concern has been given to the outdoor residential space experience in public housing in other parts of the country. The implication is that housing policies drafted based on the recommendations from existing studies would not be comprehensive enough to give a holistic view to housing issues in the country. Even though the largest number of public housing estates is found in the south-west part of Nigeria, as evident in a collection of literature from that part, it is worthy to note that so many public housing estates have sprung up in the past few decades in other parts of the country. And it is worthy to note that different outdoor spaces produce different quality ratings due to differences in location, design features, and functional considerations in relation to homeowners’ idiosyncrasies (Canan et al., Citation2019), which is in alignment with Verissimo’s () view of domestic outdoor space as a complex system.

In another perspective, the peculiarities of homeowners’ behaviours and choices are affected by the lifestyle, beliefs, identity and culture of the location of their housing estate. This has been discussed in recent studies (Clark et al., Citation2021; Junot, Citation2022). This implies that different housing estates are exposed to varied environmental circumstances and residential experiences, thereby making them unique in their nature. This is certainly vital for the provision of hard evidence upon which factual decisions on the performance of public housing programmes can be founded. As a result, an interest in extending the knowledge base of residential outdoor experience in the south-south geopolitical region of Nigeria would contribute to the development of more comprehensive housing policies in not just Nigeria, but other developing countries.

In this light, the present study aims at complementing the debate for a better outdoor residential experience but gives a viewpoint from a housing estate in a developing country, using Ewet housing estate in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria, as a case study. The first objective of this study is to examine the aesthetical and functional character of the residential outdoor space in Ewet housing estate. Particularly, as a contribution to the literature, this objective will help in determining the quality of the outdoor space in terms of its usefulness (functional quality), both in design and construction, and its beauty (visual quality). The examination will be based on how they complement the house, the organisation of the landscape elements, and organisation of usable spaces. Apart from expressing the functional and aesthetic character of a typical residential site in Nigeria, this objective will help in establishing the relationship between organisation of the landscape elements and their contributions to the housing environment.

The second objective is to identify the constraints that affect quality site development in Ewet housing estate. This objective will contribute to the literature by relating homeowners’ preferred outdoor activities within their premises. Their perception of outdoor space area, and the factors which motivate and constrain residential site development will be established. The homeowners’ awareness of quality housing environment will also be assessed as an important factor.

The third objective is to develop conceptual foundation for improved process and quality of residential site development. This will be based on the results of the first two objectives. It is believed that the recommendations from this study will be relevant to architects, urban planners, housing developers, environmental managers, and perhaps policy makers for the further development and improvement of other public housing estates in Nigeria and other developing countries towards achieving a better residential outdoor space experience.

The paper is structured as follows in the remaining sections: It will review the relevant literature pertaining to the place of the residential site in the housing environment. Expectedly, this will establish what a residential site is and its place in the overall look of the housing environment where it is located, as well as relate it to the homeowners. The review will also cover housing and residential outdoor space quality, and residential outdoor space experience and quality of life. This will be followed by the methodological aspects of the study. The paper continues with the results and discussions of major findings, and ends with a conclusion.

2. Literature review

2.1. The place of the residential site in the housing environment

Apart from displaying an attractiveness that complements the house, a residential site can also provide a pleasant outdoor experience for the residents, their visitors, as well as passersby. It can affect the physiological and psychological needs of the residents (Lai et al., Citation2014). From several sources (Eusuf et al., Citation2014; Huang, Citation2006; Jamaludin et al., Citation2014; Mohamed et al., Citation2014; Penteado, Citation2021; Støa et al., Citation2016; Zhang & Lawson, Citation2009), the residential site is viewed as an important aspect of the housing environment. Significantly, as a setting for the house, it provides the surroundings within which the architecture of the house is situated. In addition, as the location for outdoor living, it serves as an exterior extension of the functions of the interior space of the house, where meeting people, recreation, gardening, or simply relaxing or playing are all activities that can take place on the residential site.

From another perspective (Burton et al., Citation2014), residential site is termed residential outdoor space, domestic outdoor space and private outdoor space. It is seen as a space meant for socialization, as well as an urban space with familiarity and close proximity to home. It is mostly used by and accessible to residents at home. It is used for the reawakening of the home users in multiple conditions, such as a healing ground for residences with illness. It could be used for restoring the mind and body and the overall well-being of the home users.

According to Gray (Citation2013), private outdoor space is an area that is only used by the residents of a home. It is also argued that since the primary function of outdoor spaces around buildings is to provide enough lighting, ventilation, and circulation, citizens all over the world passionately seek this type of outdoor space due to its many benefits (Afon & Adebara, Citation2019). Furthermore, from the view of Cooper-Marcus (Citation2010), private outdoor spaces are outdoor areas on a small plot of land that are only accessible by the owners and invited guests. Residences’ outdoor areas are a vital component of the house and an expansion of the living area. These areas are “interaction spaces, social arenas, and the most valued urban open space because of their familiarity and closeness to homes; this makes them more accessible and usable by home residents,” according to an existing study (Huang, Citation2006).

Private residential outdoor areas act as barriers between adjacent homes. It offers room for keeping pets and air space for safety. It supports residents’ health and well-being by promoting mental and physical healing and calm. Residents can get away from the strain and interruptions of city life, work, and family. Additionally, it facilitates a quicker recovery from surgery or a medical disorder (Gray, Citation2013). According to other studies (Afon & Adebara, Citation2019; Coolen & Meesters, Citation2012), outdoor spaces are important because they give occupants solitude, quiet, safety, and security. These spaces are also of great value to homes because they give kids a secure and comfy place to play and represent people’s identities and status.

2.2. Housing and residential outdoor space quality

Improvements in housing are based on assessments of its quality, which in turn help to improve the occupants’ quality of life (Opoko et al., Citation2016). According to Amao (Citation2012), the physical condition of housing and the facilities and services that engender comfortable living in a particular place are some examples of elements that affect housing quality. Although quality is a composite indicator, it varies based on user groups and situations (formal/informal housing, urban/rural, developed/developing nations; Ilesanmi, Citation2012).

Housing quality is a dynamic, multifaceted notion that meets not just engineering standards but social, and behavioural standards (Fabos, Citation1979, as cited in Opoko et al., Citation2016). According to Adeoye (Citation2016) and Olowu et al. (Citation2019), there are a number of criteria that have been identified as indicators of quality in the evaluation of residential developments, including aesthetics, ornamentation, sanitation, drainage, age of the building, access to basic housing facilities, burglary, spatial adequacy, noise level within the neighbourhood, sewage and waste disposal, air pollution, and ease of movement, among others. Housing quality indicators, including those for privacy, identity/uniqueness, comfort, taste, accessibility and direction, aesthetics, crime prevention, connection and flexibility, territoriality, security, and safety, are frequently employed in the construction industry (Adedeji, Citation2006; Afon & Adebara, Citation2019).

Some studies in Nigeria assessed the residential satisfaction of public housing as a whole. For example, Adewale et al. (Citation2015) compared the level of satisfaction of different age groups in the residential neighbourhoods in Oke Foko, Ibadan, Nigeria. The result of the study indicated that neighbourhood satisfaction was significantly influenced by age. It was found that greater dissatisfaction was recorded by the younger residents in the neighbourhoods. Among the recommendations from the study for increased satisfaction was improved physical appearance of the environment by the local government and the residents.

Ibem and Alagbe (Citation2015) conducted an investigation on the dimensions of housing adequacy for residents of public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria. The result indicated that the housing situation was inadequate. The study recommended that greater consideration be given to the ambient conditions of building interiors, utilities, security and neighbourhood facilities, as well as privacy and the sizes of main activity areas in the housing environment in the design of public housing projects.

Ardoin et al. (Citation2020) evaluated the condition of neighbourhood facilities in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. The results indicated that accessibility, adequacy and physical condition of recreational open spaces are significant predictors of satisfaction with public housing. The research recommended that public housing as well as its neighbourhood facilities should be effectively planned and implemented within the framework of the public housing delivery system in Nigeria. This aligns with previous research (Suk Kweon et al., Citation2010) that indicated that the way landscaped open spaces are planned could lead to the improvement of residents’ well-being and enhanced neighbourhood satisfaction. This is also similar to another study (Rashid et al., Citation2013) that indicated an association between the incorporation of natural and green areas in neighbourhoods and residents’ satisfaction.

Particularly on outdoor space experience, a study (Lai et al., Citation2014) identified the variables that affect how well outdoor spaces are designed. Functionality, ease of use, safety, the auditory environment, aesthetics, and air quality are a few of the considerations. Criteria including comfort, planning, landscape design, built-structure design, visual structure, outdoor livability, and level of outdoor activity are used to evaluate the quality of outdoor spaces (Hafiz, Citation2002). Residential quality standards in open areas, according to Fogh and Saransi (Citation2014), connect to issues like security, tranquility, privacy, solitude, and nature. According to Mohamed et al. (Citation2014), the following factors contribute to the poor quality of residential outdoor environments: inadequate security, a lack of or insufficient parking spaces, low-quality construction materials, and poor upkeep. As reported by Burton et al. (Citation2014), the following are barriers to outdoor spaces’ maximum use quality: inadequate maintenance, unattractiveness, a lack of seclusion, and safety.

2.3. Residential outdoor space experience and quality of life

Clean, well-maintained areas that are easily accessible for people to carry out a variety of activities are considered good-quality places. These areas draw users because they foster a sense of security and comfort that promotes happiness and good health. On the other hand, poorly planned and inadequately-maintained places can provide unsightly conditions, which in turn encourage antisocial behavior.

According to Lovett and Chi (Citation2015), it is important to take neighbourhood settings into account when developing outdoor areas in order to foster a sense of place and identity. The quality of outdoor spaces has an impact on people’s quality of life in terms of leisure time, recreation, and contact with nature. A view of trees and grass in an urban context or a wilderness setting has three consistent, positive impacts on people: it lessens mental tiredness (Berto, Citation2014), reduces stress and stress-related arousal (Bratman et al., Citation2012), and improves mood (Thompson et al., Citation2011).

According to several studies (Farr, Citation2011; Hadavi et al., Citation2015; Kaźmierczak, Citation2013; Li & Wu, Citation2013), interaction with nature improves neighbourhood quality of life, family harmony, public health, and levels of violence and crime in inner cities.

According to the uniqueness of outdoor spaces, Karuppannan and Sivam (Citation2013) hypothesised that kids, the elderly, and housewives prefer to use them for a variety of activities, such as walking, running, cycling, trekking, and playing sports and games. The impact of the environment on quality of life is correlated with the physical attributes of the environment and its close proximity to humans in all spheres. A well-designed residential environment improves social interactions by fostering face-to-face, brief-duration outdoor conversations and greetings (Gehl, Citation2011). The outdoor space can be a venue for reciprocal communication and social cognition (Peters et al., Citation2010).

To avoid distorting norms and values, social image-ability, and neighbourhood’s identity of the community, the uniqueness of place should be taken into consideration when building outdoor areas (Scarborough et al., Citation2010; ,). Referring to Tuan (Citation2013), there is an emotional need for people to have a connection to a location. For instance, citizens in the Middle East and the West believe that identity is a component of urban and neighbourhood architecture and have linked the loss of place identity and symbols to the residential environment (Brugger et al., Citation2011; Chiodelli, Citation2012; Kallus & Kolodney, Citation2010; Lewicka, Citation2011). In the same vein, some authors reported home users’ satisfaction with residential outdoor spaces in a study in Ilesha, Nigeria (Yussuf et al., Citation2019). The study indicated that users preferred the comfort, privacy, security and quality of air in outdoor spaces.

As harnessed from the literature reviewed, outdoor residential space provides an insight into the homeowner’s value system and documents their preferences with respect to their surroundings. As an expression of the values and tastes of the homeowner, the residential site can therefore mirror their thinking about the outdoor space around them. It contributes to the amenity value of the residential neighbourhood both in an aesthetic and functional manner. It gives physical, mental, and social protection and ameliorates the quality of life. It is also viewed as an investment. Tied together, the residential site can therefore provide an appropriate introduction of how the homeowner values their surroundings (functionality) and how the site contributes visually to the housing environment (aesthetics).

Unfortunately, in Nigeria, similar to other developing countries, concern for the outdoor environment, on the part of the officials of planning authorities or housing corporations and the homeowners themselves, is at an insignificant level. According to the empirical studies reviewed, many residential estates are dotted with magnificent buildings but their residential sites are marked by poor quality development and lack of maintenance. Also, the available reports expressed inconsistencies in homeowners’ appreciation, awareness and preference of the outdoor space in their housing setting. This strengthens the case for additional study in this area. It should also be noted that continuous assessment of the estates after occupancy gives a perspective on how functional and aesthetic the estates are, especially using the feedback from the end users (Ackley & Ukpong, Citation2019). The recommendations from the study would serve as adequate feedback for the improvement of the homeowners’ outdoor residential space experience.

3. Method

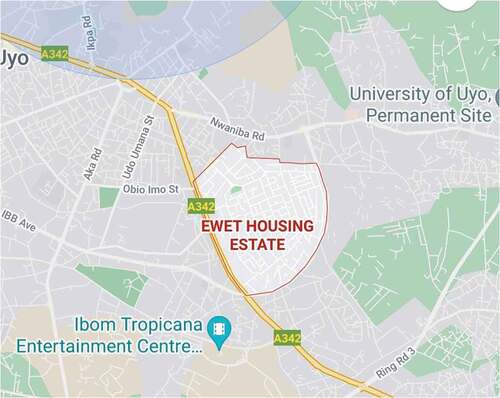

The study area, Uyo, is the capital city of Akwa Ibom State, located in south-south Nigeria. It shares similar characteristics in its housing situation with other towns in Nigeria. While the structure of the central area of the city remained homogenous with no noticeable differences in housing character, the new residential areas and estates at the outskirts varied in house quality and style. Today, the city’s morphology has been significantly altered for the construction of major landmarks such as Ibom Plaza, Victor Attah International Airport, E-library, 40,000-seat stadium, 5-star hotel with an ultra-modern golf resort, flyovers, the Ibom Tropicana entertainment centre, and 21-storey smart building. Ewet housing estate is shown using a red line on a map of a section of Uyo urban (see, Figure ). Ewet housing estate is surrounded by Nwaniba Road, Uruan Street, Oron Road, and Edet Akpan Avenue in Uyo urban.

Ewet housing estate illustrates the typical residential environment of many housing estates in the country, where quality houses are located in unsightly surroundings. A field survey by the authors has shown that more than 60% of the housing stock in the estate is made up of modern and palatial houses, built within the last three decades or so. From visual observation, it is evident that despite the current lull in other economic activities in the state, house construction within the estate has continued unabated, with well over 93% of the total land area already built. Over the last two decades, hotel establishments havebecome an added feature of the estate.

However, the estate represents the epitome of a lacklustre environment, having no access to basic infrastructural amenities (Adeagbo, Citation2000). The estate was founded in 1973 to provide housing for all categories of civil servants in the then Cross River State. Before the creation of Akwa Ibom State in 1987, this group was the main owner-occupiers. However, after the state’s creation, demand for plots in the estate was accelerated, paving the way for the original inhabitants, particularly the low-income group, to be systematically bought out by attractive offers. Today, Ewet housing estate, the first of the many estates in Uyo (Nwanekezie & Ezema, Citation2019), with a total land area of over 280 hectares, has become an exclusive area for the nouveau riche as politicians, former local government chairpersons, political office holders, and rich businesspersons own palatial houses within the estate.

Ewet housing estate is comparable in terms of status to first-class public housing estates in other states of the country, such as Lagos State (Junot, Citation2022), Adewale et al., Citation2015), and Ogun State (Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015). The estate is managed by a state government agency called Akwa Ibom Property and Investment Company (APICO). Even though the estate is mainly a residential area, some commercial (examples are hotels, recreational centres, eateries, and schools) and religious buildings abound with a good road network and proper drainage system. These were considerations for the choice of Ewet housing estates among other estates (Federal, Osongama, Akwa Ima, Aka Itiam, Akpasak, and Shelter Afrique housing estates) in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. The Ewet housing estate is labelled in units from unit A, B, C, to N (see, Table ), each carrying a different number of plots and different plot sizes. In total, there are 1287 plots on the estate.

Table 1. Distribution of plot sizes and houses in Ewet housing estate in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

The method adopted for the study was a combination of critical field observation with a structured questionnaire survey. The field observation, which is a similar method used in previous similar studies (Adabre et al., Citation2022; Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015), was done with the use of an observation schedule as a data gathering tool for experts’ utilization. This tool enabled the authors to document the expert’s view of the specific physical conditions of the housing estate sampled. The data gathered related to the functional and aesthetic quality of the outdoor space in the context of design and construction, beauty, maintenance tendency, security and visual protection, percentage of built-up area and access to the rear and side of the building. The second method used a structured questionnaire as the tool for data gathering. The questionnaire was examined to determine its strength. It was pretested with some residents of a nearby federal housing estate, Abak Road, Uyo. It was later modified to incorporate relevant suggestions for an improved research result. The questionnaire instrument was then put through face validation by three senior experts in the Department of Architecture at University of Uyo. A reliability coefficient of 0.81 was obtained using Cronbach Alpha.

The structured questionnaire, also used in previous studies (Adewale et al., Citation2015; Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015), was designed, based on the study objectives, to elicit information on the problems of residential site development as well as the homeowners’ appreciation, awareness and preferences for the outdoor environment. Under the appreciation, the inquiry centred on visual (aesthetic) and functional quality of the outdoor values in relation to the house, organisation of landscape elements, organisation of usable, and contribution to amenity value of neighbourhood. For awareness and outdoor preferences, the inquiry focused on factors of poor quality development of a residential site, preferred outdoor activities, perception of outdoor environment, motivation factors for residential site development, and awareness of quality environment.

The questionnaire was divided into two parts: part 1 asked (including a personal profile of the respondents), while part 2 inquired about their outdoor values. A total of 280 houses were selected from the 14 units in the estate, representing approximately, 22% of the total housing stock (see, Table ). Due to the uncooperative attitude of some homeowners, only 150 houses were finally surveyed with the help of five previously trained research assistants (on a voluntary basis) who were 400- level students from the department of architecture, University of Uyo, Uyo. In administering the questionnaire, a stratified random sampling technique was used. Each unit represented a stratum, while the houses were randomly selected. The questionnaire was distributed to the heads of household in the randomly selected houses. The homeowners were asked to give their personal profile and rate, on a 5-point Likert scale, their motivations, constraints, preference and awareness as factors in the development of their surroundings. The scale was based on Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. In analyzing the data, each of these ratings was assigned a weighted value, of which 5 was assigned to the highest weighted variable (Strongly Agree) and 1 to the least (Strongly Disagree). The strength of using weight value in this case comes from its application in a recent similar study (Adabre et al., Citation2022).

A total weight average (TWA) was calculated for each variable and was derived from the summation of product of the number of responses for the rating of each variable and the respective weight value for each rating (Afon, Citation2000). In a mathematical form, this is expressed in equation 1:

Where:

TWA = Summation of Weight Average of each of the questions

Xi = number of respondents choosing a particular rating (i)

Yi = the weight assigned a value (i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

A mean value (X) was then computed for each variable by dividing the TWA by the total number of respondents. A cutoff point was obtained by adding the weighting of the response categories and dividing by the number, which in this case amounted to 3.00. Any variable with a mean value of 3.00 and above was interpreted as a factor, while those with a mean below were considered non-factors (Uzoagulu, Citation1998). Simple regression analysis was used to determine the relationship among the various factors.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the respondents

The respondents’ socio-economic and demographic characteristics are expressed in Table . The result of the data analysis of those that participated in the survey (as shown in Table ) revealed that male respondents were 70% while female respondents were 30%. Under marital status, 74.7% were married, 20% were divorced and 5.3% were yet to be married. The active age population among the respondents was 80%, while 20% were inactive. Under religious affiliation, Christians were 92%, Moslems were 4%, Eckists were 2%, and others were 2%. Under occupation, politicians were 38.7%, civil servants were 24%, traders were 13.3%, retirees were 12%, farmers were 8% and students were 4%. In terms of education level, 80% had tertiary education and 20% had secondary education. Housing tenure comprised of owner occupiers and renters, with a response rate of about 55% and about 45%, respectively. The result also showed that 60% of the respondents had stayed in the estate for more than 10 years, 30% for 5–10 years and 10% for less than 5 years. Approximately 75% of the respondents earned between N100, 000 and N200, 000 per month, 20% earned less than N100, 000 and 5% earned more than N200, 000.

Table 2. Socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the respondents

4.2. Examination of a typical residential site character in Nigeria considering the aesthetical and functional requirements

Considering the aesthetic and functional requirements of a residential site, the specific conditions in the estate were examined in the light of available data from the field investigations as sought in the study’s first objective. While over 60% of the houses surveyed can be described as being of very high quality, both in design and construction, their beauty is, however, overshadowed by the surrounding poor, barren and lacklustre open space areas, which have benefited very little from good site design and maintenance.

Similar to previous studies in Turkey (Canan et al., Citation2019), and Italy (Martinelli et al., Citation2015), findings show that while each of the sites exhibits varying qualities depending on the effectiveness of its design, there are certain commonalities among them. Even though these findings are noteworthy, they will have to await a detailed consideration of countrywide reports before a definitive statement of findings can be made for the whole country.

In what may be seen as an attempt to achieve maximum protection and visual privacy, almost all the houses surveyed in the estate have fence walls, which are rather brutal, contributing little to the beauty of the enclosed houses and turning their back on the street. This result is similar to what was obtained in previous studies conducted in different parts of Nigeria, such as in Illesha (Yussuf et al., Citation2021), Akure (Ardoin et al., Citation2020) and Ogun State (Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015). Within the residential site, much of the plot is taken up by building mass, leaving less than 50% of the plot ratio as open space area for modest outdoor living or enjoyment by the homeowners. This inadequate outdoor space area within each plot size has severely limited its usefulness and visual quality.

The front yard of most residential sites is seen only as an engineered organisation of driveways and parking spaces without considering that it can fulfil these needs while also being an attractive environment to experience. Other usable outdoor spaces within the front yard for arrival, sitting, entertainment, eating, or recreation are generally lacking. Sure, some of these activities still take place, but under less-than-ideal circumstances. The challenge for most front yards is how to combine functional requirements with aesthetic considerations.

The backyard is often seen as nothing more than a space for gardening, working, or storage. In contrast to the front and back yards, most side yards in the estate served little use except to provide access around the side of the house. In most cases, they are wasted and leftover areas except for corner plots or those that have generous space on one or both sides of the house.

Perhaps the biggest problem with all the residential sites in the estate is that they lack spatial definition and landscape details, and therefore lack usefulness beyond providing a setting for the houses. In most cases, they are organized in such a manner that there is no reason to go outside of the houses. This is in alignment with a previous study (Farida, Citation2013) that reported a low rate of use of outdoor space because the design did not encourage such usefulness. This lack of usefulness has a telling effect on the residents’ satisfaction with the outdoor space and by extension, it affects their wellbeing, as posited by previous studies (Adewale et al., Citation2015; Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015; Suk Kweon et al., Citation2010).

To determine the relationship between the organisation of these landscape elements and their contributions to the housing environment, as represented in Table , a simple regression analysis was done. It was observed in Table that the visual quality of the organisation of these elements has a very strong positive relationship (correlation coefficient of 0.88) with their contribution to the amenity value of the neighbourhood.

Table 3. Observed organisation of outdoor space area in Ewet housing estate

Table 4. Relationship between visual quality of the organisation of landscape elements and contribution to amenity value of the neighbourhood

4.3. Factors of poor quality development of a residential site

The second objective of this study was to find out those factors that have tended to inhibit quality site development. A closer look at Table shows some interesting relationships. It was found that the homeowners’ preference for outdoor activities with recreation within their premises has a mean value of 4.08. This value, which in this study represents a positive factor, may be what has influenced the homeowners’ perception of their outdoor space area as a recreational outlet, with a mean value of 3.92.

The motivation to beautify the premises and to have a good setting for the house, appearing as positive factors with values of 3.98 and 3.77 respectively, does not appear to make any appreciable impact on the thinking of the homeowner to see their surroundings as an integral part of the entire residential development, as indicated by its showing as a non-factor with a value of 2.74. Rather, this poor perception seems to be affected by their inability to appreciate the outdoor area as a livable space or to consider it as important as the house itself, both of which appear as non-factors with values of 2.53 and 1.93, respectively.

Nonetheless, the homeowners see non-availability of good site design/lack of specification by the housing authority for site development, and inadequate space and site problems as the major constraints affecting residential site development, with values of 3.80 and 3.75, respectively.

The values obtained for the awareness variables are quite revealing. Apart from the variable “contact and exposure” appearing as a factor with a value of 3.97, others are seen as non-factors. Even as a factor in the study, this variable did not appear to influence the quality of the development of the outdoor space area in the estate. It is expected that the homeowners, having been exposed to beautiful surroundings, should carry with them a certain starry-eyed excitement over the possibility of championing in their residences, some of the impressiveness sensed from such contact and exposure. It is hardly probable that many of them are conscious of such impressions in any technical sense. The occurrence of other variables in the awareness category as non-factors may disguise the importance of awareness as a major factor in outdoor value, as will be explained later in this paper.

A regression analysis was done to determine the relationships among these factors in the outdoor space development. The awareness factor, as shown in Table , had a strong positive relationship with the quality of site development in the estate, with a correlation coefficient of 0.58. The awareness factor in predicting the quality of site development yielded a multiple regression of 0.58, a multiple R2 of 0.330. The result also showed that 33% of the variance in site quality development can be explained by the awareness factor. The table also shows that the analysis of variance for the multiple regression data produced an F-ratio of 74.4, which is significant at 0.05 level.

Table 5. Relationship between the awareness factor and quality of site development

As already noted, this relationship may be indicative of the presence of negative values obtained in the study for the variables “personal sensibility,” “family background” and “training,” which are known for their usually strong influence on awareness as a factor (Calder, Citation1981).

The homeowners’ poor perception of outdoors space areas is reflected in the positive relationship it has shown in the development of residential site, having a correlation coefficient of 0.904.

The homeowners’ perception in predicting site development motivation yielded a multiple R2 of 0.817 (see, Table ). The result also showed that about 82% of the variance in motivation for site development can be explained by homeowners’ perceptions. The table also shows that the analysis of variance for the linear regression data produced an F-ratio of 2661, which is significant at 0.05 level. This finding has been corroborated by an earlier study by Obashoro-John (Citation2002), which similarly indicated the inability of many homeowners to appreciate the value of outdoor environments. This is reflected in the unsatisfactory value in the overall quality of site development in the estate. However, Olotuah (Citation2009) reported a correlation between quality of life and the physical environment in which people live. In addition, socio-cultural factors and the economy relate to the quality of outdoor spaces (Adedeji, Citation2006). A similar study found little relationship between socioeconomic attributes, physical characteristics of outdoor spaces and residential outdoor space quality in Western Nigeria (Yussuf et al., Citation2019).

Table 6. Relationship between homeowners’ perception and site development motivation

The constraint factor in predicting site development motivation yielded a multiple R2 of 0.929, as shown in Table , with a correlation coefficient of 0.95. The result also showed that about 93% of the variance in site development motivation can be explained by the constraint factor. The table also shows that the analysis of variance for the multiple regression data produced an F-ratio of 3919, which is significant at 0.05 level.

Table 7. Relationship between the constraint factor and site development motivation

The result indicated that the constraint factor has a strong influence on this poor site development. The two items of constraints (non-availability of design and inadequate space and site problem) can, however be easily overcome by availability of expertise to provide purposeful design solutions to induce desired motivation toward open space development.

For now, it may be too hasty to say how directly or indirectly each of these factors influences the quality development of a residential site in a single study without corroborating other on-going studies elsewhere in the developing world. Moreover, one must be cautious of the statistical relationships found among these factors, as they may tend to disguise the discrepancies between the stated ideal and reality, portraying the complex relationships between environmental attitudes and environmental behavior (English & Mayfteld, Citation1970; Farida, Citation2013). This is a limitation of the study.

4.4. Conceptual foundation for improved process and quality of residential site environment

The next focus is the response to objective three of this study. This study has identified several disparate factors, that have an effect on the development of a residential site. Overall, the study found that caring for the outdoor space area appears to be dependent on the homeowners’ inability to recognise the value of the outdoor environment. A fuller understanding of this inability will, however, require an in-depth study of the social ecology of residential neighbourhoods as a forerunner in the context of the physical, socioeconomic and cultural evolution which Nigeria has passed through.

Individual attitudes toward their outdoor environment are typically linked to their awareness and appreciation of the environment’s natural and man-made values. Awareness of these values, which elicits responses, is partially the fruit of education, be it formal or experiential and partially due to personal sensibility. In this regard, studies have shown that one’s cultural background is a factor in the development of the scale of values for the environment (Ardoin et al., Citation2018; Calder, Citation1981; Zhan et al., Citation2018). Place identity, residential image and symbols are associated factors as observed by some authors (Brugger et al., Citation2011; Chiodelli, Citation2012; Kallus & Kolodney, Citation2010; Lewicka, Citation2011; Lovett & Chi, Citation2015).

Most literature dealing with environmental values has emphasised environmental education as a way of sensitising awareness and consciousness toward the environment (Ardoin et al., Citation2020, Citation2018; García-González et al., Citation2021; Otto & Pensini, Citation2017; Slimani et al., Citation2021; Tarsitano et al., Citation2021). While valuable, the approach has tended to disguise the wider conceptual issues involved in the development of environmental values. Unlike empirical knowledge about the environment as a whole, the development of environmental values has a long lineage or heritage among people, reflecting the changing views of their relationship to the environment (Adedeji, Citation2006; Afon & Adebara, Citation2019; English & Mayfteld, Citation1970: Fabos, Citation1979). A lineal survey of this evolution may illustrate not only the level to which these values are developed, but also the tradition in the society that they represent. Such history is essential for understanding a society’s current attitude toward the outdoor environment. For instance, in Western European thought, it goes back at least to the 18th century romanticism and the 19th century social and environmental reform movements, which crystallised in the environmental crisis of the late 1960s and the early 1970s. The lasting effect of this evolution is today represented by several bodies of environmental legislation, that are safeguarding the quality of environment in these western countries (Clark et al., Citation2021; Ganzleben & Kazmierczak, Citation2020; K. Li et al., Citation2016).

In Nigerian society as a developing nation, the concern for environmental values may be traced back to the olden days when caring for the residential environment was an adaptive approach to the traditional housing environment (Ola, Citation1984). Then there was the tendency to view landscape in terms of aesthetic and symbolic meaning. With this conception, the environment must have influenced the perception of people who strived to create an aesthetic appreciation of nature by caring for their surroundings. They grew flowering and fruiting plants, which continued to bloom and sent out a beautiful fragrance most of the year. These trees improve the outdoor microclimate and human thermal comfort (Zhao et al., Citation2018). Their perceptive organisation of their surroundings, though somewhat naive in the light of present-day understanding of aesthetic quality, illustrated a happy acceptance of outdoor values and an explicit concern for improving the quality of those surroundings. Falade (Citation1998) has noted that the colonial administration also provided the country with a legacy of suburban residential development, which was based on the garden city concept (Shadar & Maslovski, Citation2021; Souther, Citation2021). Garden city principles are based on providing a conducive natural environment with a green infrastructure network linked to biological diversity, life variability, and resilient climatic conditions.

However, the most significant disruption of this ancient capacity for outdoor values in the country may be explained by different patterns of urban development (Jagboro, Citation2000; Mabogunje, Citation1968). The rapid, uncontrolled growth of urban cities has had a tremendous impact on outdoor values because it represents a radical change in the attitude toward the environment (Brown et al., Citation2015; Ola, Citation1984; Oruwari, Citation2000; Penteado, Citation2021; Pietro et al., Citation2021; Uzoagulu, Citation1998). Such an approach has tended to contrast sharply with the old notion of bringing order to the outdoor spaces.

Today, much of the urban development in the country has proceeded with little or no concern for the physical form and visual appearance of the urban cities. Many millions of Nigerian urban dwellers live with and have to endure a barren bleakness created by this trend in urban development (Cooper-Marcus, Citation2010). The quality of both public and private environments, which holds the key to the quality of most urban and suburban areas, has seriously been impaired by the uncontrolled growth of these urban areas. In the case of a private environment, it is the quality of the residential sites, that is of paramount importance. The residential environment is frequently visually monotonous and contributes little to the residents’ quality of life (functionality). This has been reported in previous studies, most especially in the western part of Nigeria (Ardoin et al., Citation2020; Ibem & Alagbe, Citation2015). According to the studies, there has been insufficient attention paid to the outdoor architecture of the majority of residential environments in Nigeria (in comparison to the indoor space). This has a serious impact on residents’ well-being and neighbourhood satisfaction.

Moreover, the daily living conditions under these visual bareness and, in most cases, warren-like outdoor conditions are neither conducive to the development of outdoor values nor to the appreciative use of outdoor space areas. Many homeowners in the residential estates in Nigeria today are not far from being products of such living circumstances (Afon, Citation2000; Oruwari, Citation2000).

It is not surprising that caring for the outdoor space in the home seems like a difficult responsibility and does not come naturally. For example, many homeowners do not bother these days to plant flowering shrubs or trees anymore to promote leafy residential suburbs as a counterpoise to the increasing congestion and disorder of the city. This would have improved residents’ views of good scenes such as well-planned trees and grass, with its associated three consistent, positive impacts on people: lessening of mental tiredness (Berto, Citation2014), reduction of stress and stress-related arousal (Bratman et al., Citation2012), and improvement of mood (Thompson et al., Citation2011). In addition, according to several studies (Farr, Citation2011; Hadavi et al., Citation2015; Kaźmierczak, Citation2013; Li & Wu, Citation2013), interaction with nature improves neighbourhood quality of life, family harmony, public health, and levels of violence and crime in inner cities. On the contrary, sparing time to care for the surroundings is no longer part of personal and family tradition and responsibility in Nigeria. Largely, this complacency may have been transformed into a bureaucratic process, that asks for little concern for the residential site character.

When viewed against the backdrop of heavy capital outlay in the building of big and beautiful houses, as evident in Ewet housing estate, it is seen that money is not a constraint in residential site development. The problem may also be in alignment with the psychological and behavioural needs of the homeowner (Wang et al., Citation2016). In addition, it may also lie in the poor acceptance of outdoor values, as demonstrated by the failure to regard the outdoor space area as a livable part of the residential environment by both the housing corporations on the one hand, and the homeowners on the other hand.

Given the above situation, what needs to be done to achieve a quality residential environment is to evolve a process that will awaken the consciousness and sensibility of both public officials and homeowners to induce the desired attitudes toward its development. To do this, the first thing is to put in place an effective and efficient development control mechanism within the planning authorities and the housing corporations that will address the issues of visual character, building siting, circulation and open spaces in a housing development. This will entail creating a landscape unit in the planning section and engaging the services of professional landscape architects to develop concepts and specifications that will regulate the specific spatial character of the housing environment.

These development blueprints are necessary if an orderly interface in the development of residential environments is the desired goal. They should be prepared for incorporation into articles of protective covenants and restrictions guiding development within the housing estates. The development guidelines, which should be a combination of landscape easements, plot ratios and other basic landscape controls that are necessary to provide direction to the homeowner for his or her residential development. It should also ensure long-term development in a manner consistent with the housing authorities’ objectives as to type, quality, image and density of improvements.

To implement the above, residential site design for individual houses must be made part of the requirement for approval of building plans. Up until now, building plans for houses in Nigerian cities have reflected primarily the site layout and design of buildings. Their site designs and accompanying construction details are, in most cases, nonexistent. Individual housing units must comply with certain standards and building codes, which are made either by the planning authorities or by agencies responsible for the development and maintenance of the housing estates (Adeagbo, Citation2000). The agencies must see to the enforcement of such protective design covenants as set forth in the development document.

However, the homeowners may not readily appreciate this process, unless they are aware of the quality and functional implications of the wide gap between their lacklustre surroundings and the specified minimum standards of a housing environment, which are desirable. This awareness, which can only come through enlightenment and the enforcement of these minimum standards, will have a definite effect on acceptance and behavior. What is advocated here is a development process, that stimulates the interest and involvement of homeowners in achieving a decent housing environment. Residential outdoor space development needs to be seen as a decent housing environmental scheme that grows on the basis of vibrant factors such as function, aesthetics and economy (Ile, Citation2012). Given that a residential outdoor site is an extension of the living and useable spaces that are part of a home (Farida, Citation2013), it can be made to play a vital design role in reducing crime and improving the security of the place.

Finally, there is a dire need to inculcate in Nigerians and other citizens of other developing countries (especially home owners) the educational awareness of environmental perception and appreciation of their built environment in quality site selection and development; the treatment of residential outdoor space is as important as its indoor counterpart. This perception unfolds from home training and permeates all levels of the formal and non-formal educational systems. The parents, the classroom teachers, and lecturers in architecture and urban planning have the responsibility of disseminating the environmental educational awareness syndrome to pupils, students and the general public in the site selection and development exercise. This process forms the bedrock of the inculcation process, which must of necessity be institutionalised within our cultural milieu, otherwise, the much-anticipated dividend may be delayed.

5. Conclusion

This study has shown that residential site development, or lack thereof, is often a reflection of the acceptance of outdoor values. It depends a great deal, on how it is thought of as an extension of the interior space of the house and as a link between the house and the public open space. When those values are not defined in responsive, efficient and economic ways to give quality to the space, the residential site becomes inconsequential. This study complemented the debate for a better outdoor residential experience with a focus on developing countries. In this regard, Ewet housing estate in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria was examined as a case.

In terms of functionality and aesthetic examination of Ewet housing estate, the study found that while the houses were of high quality, they were overshadowed by the surrounding lacklustre open space areas with very little good site design and maintenance.

In addition, the homeowners’ preference for outdoor activities for recreation, the motivation to beautify the premises and have a good setting for the house appeared as factors of poor quality development of the residential site. The homeowners saw a lack of availability of good site design/lack of specification by the housing authority for site development, and inadequate space and site problems, as the major constraints affecting residential site development. A conceptual foundation was presented that can help improve the process and quality of residential site development.

The existing anarchistic system of open space development, in which many homeowners treat their residential surroundings as they please without paying attention to the aesthetic and functional requirements of the housing environment, can only contribute to the poor visual quality of the entire residential neighbourhood. Residential site design ought to display a thoughtful attention to quality appearance and details that create harmony with the desired image of the total housing development.

To improve the residential outdoor space experience in developing countries, both the controlling agencies and the homeowners must perceive issues relating to the housing environment. This should be viewed not in terms of controlling power and the right to private property, but rather, in terms of functional and aesthetic qualities of the residential estates in the countries. On one hand, the agencies should be ready to establish and enforce quality design, development and construction standards for the estates, which are their responsibilities. Proper staffing of the agencies with professionals with cognate experience in this field is also recommended. The homeowners, on the other hand, should see their residential sites as an integral part of the residential development that contributes to the amenity value of the housing environment.

Lastly, this study is limited since it focused on only one estate, as earlier stated (see Section 3.2). Further studies in other towns with different cultural atmospheres, scenarios and concepts will enrich the number and tell, from a different perspective, how the different factors already mentioned affect the quality development of a residential site in the developing countries. In addition, a larger sample size may suggest a different context in assessing outdoor value for a residential site. A comparison of different estates may also give an interesting perspective to the debate of improving the outdoor residential experience in developing countries.

Authors’ statement

(1) Edidiong UKPONG: Conceptualization, Software, Analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation.

(2) Utibe AKAH: Methodology, Data curation, Reviewing and Editing.

(3) Hafeez AGBABIAKA: Supervision, Reviewing and Editing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the students of Department of Architecture, University of Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria for the role of research assistants they played.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Edidiong Ukpong

Edidiong Ukpong The authors are experts in environmental evaluation, both indoor and outdoor. The corresponding author specialises in Daylighting, Sustainability, Indoor/Outdoor Environmental Quality, Architectural Education, and Urban Design. He is a practising architect in Nigeria, He is registered with the Architects Registration Council of Nigeria (ARCON) and the Nigerian Institute of Architects (NIA). In 2014, he received the Overall Best Candidate Award in NIA Professional Practice Examination. The second author specialises in Architectural Education, Sustainability, and Building Information Management. The third author specialises in Tourism and Recreation Planning, Housing and Environmental Studies. The authors have published papers in their respective areas of discipline. The current study is part of a larger study in Nigeria that aims at addressing the issues in environmental experience with particular focus on outdoor experience in public housing. It is the hope of the authors that this paper will be useful to governments, policymakers, outdoor designers such as architects, town planners, facility managers, and homeowners about issues of outdoor planning and end-users’ experience.

References

- Ackley, A., & Ukpong, E. (2019). Exploring post occupancy evaluation as a sustainable tool for assessing building performance in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering, 25(2), 71–25. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.sace.25.2.21176

- Adabre, M. A., Chan, A. P., Edwards, D. J., & Mensah, S. (2022). Evaluation of symmetries and asymmetries on barriers to sustainable housing in developing countries. Journal of Building Engineering, 50, 104174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104174

- Adeagbo, A. (2000). The physical planning process and housing development. In A. O. Bayo, F. A. Stevens, & O. Abiodun (Eds.), Effective housing in the 21st Century (pp. 23-29). The Environmental Forum, Federal University of Technology.

- Adedeji, Y. M. D. (2006). Outdoor space planning and landscape quality of religious centers in Akure, Nigeria. Inter-World Journal of Management and Development Studies, 2(1), 57–67.

- Adeoye, D. O. (2016). Challenges of urban housing quality: Insights and experiences of Akure, Nigeria. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 216, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.036

- Adewale, B. A., Taiwo, A. A., Izobo-Martins, O. O., & Ekhaese, E. N. (2015). Age of residents and satisfaction with the neighbourhood in Ibadan core area: A case study of Oke Foko. European Centre for Research Training and Development, 3(2), 52–61.

- Afon, A. O. (2000). Use of residents’ environmental quality indicator (EQI) data in core residential housing improvement. In A. O. Bayo, F. A. Stevens, & O. Abiodun (Eds.), Effective housing in the 21st Century (pp. 115-122). The Environmental Forum, Federal University of Technology.

- Afon, A. O., & Adebara, T. M. (2019). Socio-cultural usage of building setback as open space in the core residential area of Ota, Nigeria: Implications for physical planning. Proceedings of Environmental Design and Management International Conference “EDMIC 2019”, 308–319.

- Akeju, B., & Andrew, A. (2007). Challenges to providing affordable housing in Nigeria. 2nd Emerging Urban Africa International Conference on Housing Finance in Nigeria.

- Amao, F. L. (2012). Urbanization, housing quality and environmental degeneration in Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 5(16), 422–429. https://doi.org/10.5897/JGRP12.060

- Anthony, J. (2022). Housing affordability and economic growth. Housing Policy Debate, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2065328

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., & Gaillard, E. (2020). Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation, 241, 108224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224

- Ardoin, N. M., Bowers, A. W., Roth, N. W., & Holthuis, N. (2018). Environmental education and K-12 student outcomes: A review and analysis of research and analysis of research. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2017.1366155

- Ashley, B. P. (2021, January 21). Residential design quality research report. Hoare Lea. https://hoarelea.com

- Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: a literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral Sciences, 4(4), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4040394

- Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2012). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x

- Brown, R., Vanos, J., Kenny, N., & Lenzholzer, S. (2015). Designing urban parks that ameliorate the effects of climate change. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.006

- Brugger, A., Kaiser, F. G., & Roczen, N. (2011). One for All? Connectedness to nature, inclusion of nature, environmental identity, and implicit association with nature. European Psychologist, 16(4), 324. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000032

- Burton, E., Mitchell, L., & Griffin, A. (2014). Do garden matter? The role of residential outdoor space. In I’DGO publication, WISE (wellbeing in sustainable environment) (pp. 1-6). University of Warwick. https://www.idgo.ac.uk/useful_resources/Publications/WISE_MTP_brochure_FINAL.pdfchrome-

- Calder, W. (1981). Beyond the view (Revised) ed.). Inkata Press.

- Canan, F., Golasi, I., Ciancio, V., Coppi, M., & Salata, F. (2019). Outdoor thermal comfort conditions during summer in a cold semi-arid climate. A transversal field survey in Central Anatolia (Turkey). Building and Environment, 148, 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.11.008

- Chien, M., & Liu, S. (2022). The impacts of global liquidity on international housing prices. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-11-2021-0130

- Chiodelli, F. (2012). Planning illegality: The roots of unauthorised housing in Arab East Jerusalem. Cities, 29(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2011.07.008

- Clark, H. L., Buzatto, B. A., & Halse, S. A. (2021). A hotspot of arid zone subterranean biodiversity: The Robe Valley in Western Australia. Diversity, 13(10), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13100482

- Coley, R., Leventhal, T., Lynch, A. D., & Kull, M. (2013). Relations between housing characteristics and the well-being of low-income children and adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 49(9), 1775–1789. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031033

- Coolen, H., & Meesters, J. (2012). Private and public green spaces: Meaningful but different settings. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 27(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9246-5

- Cooper-Marcus, C. (2010). Shared outdoor space and community life. Place Journal, 15(2), 31–41. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5jz7d921

- English, P. A., & Mayfteld, R. C. (1970). Man, Space, and Environment. Oxford University Press.

- Eusuf, M. A., Mohit, M. A., Eusuf, M. M. R. S., & Ibrahim, M. (2014). Impact of outdoor environment to the quality of life. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 153, 639–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.096

- Fabos, J. G. (1979). Planning the total landscape: A guide to intelligent land use (Revised) ed.). West View Press.

- Fakere, A. A., & Duke-Henshaw, O. F. (2020). Assessment of user’s satisfaction with neighbourhood facilities in public housing estates in Akure, Nigeria. Facilities, 38(5), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1108/F-07-2019-0074

- Falade, J. (1998). Public acquisition of land for landscaping and open space management. Journal of Nigeria Institute of Town Planners, 11, 1–13.

- Farida, N. (2013). Effects of outdoor shared spaces on social interaction in a housing estate in Algeria. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 2(4), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2013.09.002

- Farr, D. (2011). Sustainable urbanism: Urban design with nature. John Wiley & Sons.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. (1991). National Housing Policy. Federal Government Press.

- Fogh, A. O., & Saransi, F. S. (2014). The role of open residential complexes and its impacts on peoples’ lives. Advanced Environmental Biology AENSI Journals, 8(16), 628–635.

- Ganzleben, C., & Kazmierczak, A. (2020). Leaving no one behind-understanding environmental inequality in Europe. Environmental Health, 19(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00600-2

- García-González, J. A., Palencia, S. G., & Sánchez Ondoño, I. (2021). Characterization of environmental education in Spanish Geography textbooks. Sustainability, 13(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031159

- Gehl, J. (2011). Life between buildings: Using public space. Island Press.

- Gray, K. (2013). Are outdoor spaces important? An investigation into the provision of outdoor space for medium density housing developments. [Master’s thesis] University of Otago.

- Hadavi, S., Kaplan, R., & Hunter, M. C. R. (2015). Environmental affordances: A practical approach for design of nearby outdoor settings in urban residential areas. Landscape and Urban Planning, 134, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.10.001

- Hafiz, R. (2002). Comfort and quality of indoor and outdoor spaces in semi-tropical humid city: An analysis of urban planning and design. R QUALITY/HAFIZ.PDF. http://p20017719.eng,ufjfibr/Public/AnaisEventoscientificos/PLEA_2002/4_COMFO

- Huang, S. L. (2006). A study of outdoor interactional spaces in high-rise housing. Landscape and Urban Planning, 78(3), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.07.008

- Ibem, E. O., & Aduwo, E. B. (2013). Assessment of residential satisfaction in public housing in Ogun State, Nigeria. Habitat International, 40(1), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.04.001

- Ibem, E. O., & Alagbe, O. A. (2015). Investigating dimensions of housing adequacy evaluation by residents in public housing: Factor analysis approach. Facilities, 33(7/8), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/F-02-2014-0017

- Ibem, E., Opoko, A. P., Adeboye, A. B., & Amole, D. (2013). Performance evaluation of residential buildings in public housing estates in Ogun State, Nigeria: Users‘ satisfaction perspective. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 2(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2013.02.001

- Ibem, E. O., Opoko, P. A., & Aduwo, E. B. (2015). Satisfaction with neighbourhood environments in public housing: Evidence from Ogun State, Nigeria. Social Indicators Research, 130(2), 733–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1188-y

- Ile, U. (2012). Compositional planning of residential outdoor space in courtyards. Architecture and Urban Planning, 6(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.7250/aup.2012.001

- Ilesanmi, A. O. (2012). Housing, neighbourhood quality and quality of life in public housing in Lagos, Nigeria. International Journal for Housing Science, 36(4), 231–240. https://ma3riifa.com/category/general-knowledge/

- Jagboro, O. (2000). Sustainable development and cost behavior of landscape elements in urban residential buildings in Lagos metropolis. In A. O. Bayo, F. A. Stevens, & O. Abiodun (Eds.), Effective housing in the 21st Century (pp. 96-100). The Environmental Forum, Federal University of Technology.

- Jamaludin, S. N., Hanita, N., & Mohamad, N. (2014). Designing conducive residential outdoor environment for community: Klang Valley, Malaysia. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 153, 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.070

- Jegede, F. O., Ibem, E. O., & Oluwatayo, A. A. (2020). The influence of location, planning and design features on residents’ satisfaction with security in public housing estates in Lagos, Nigeria. Urban Design International, 1997, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00141-7

- Jiboye, A. D. (2010). The correlates of public housing satisfaction in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 3(2), 17–28. https://www.scinapse.io/papers/2161134969

- Junot, A. (2022). Identification of factors that assure quality of residential environment, and their influences on place attachment in tropical and insular context, the case of Reunion Island. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 37(3), 1511–1535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09906-0

- Kallus, R., & Kolodney, Z. (2010). Politics of Urban Space in an Ethno-Nationally Contested City: Negotiating (Co)Existence in Wadi Nisnas. Journal of Urban Design, 15(3), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2010.487812

- Karuppannan, S., & Sivam, A. (2013). Comparative analysis of utilization of open space at neighbourhood level in three Asian cities: Singapore, Delhi and Kualalumpur. Urban Design International, 18(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2012.34

- Kaźmierczak, A. (2013). The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landscape and Urban Planning, 109(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.007

- Lai, D., Zhou, C., Huang, J., Jiang, Y., Long, Z., & Chen, Q. (2014). Outdoor space quality: A field study in an urban residential community in Central China. Energy and Buildings, 68(B), 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.02.0521

- Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207 230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

- Li, Y., Fan, S., Li, K., Zhang, Y., & Dong, L. (2021). Microclimate in an urban park and its influencing factors: A case study of Tiantan Park in Beijing, China. Urban Ecosystems, 24(4), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-020-01073-4

- Li, Z., & Wu, F. (2013). Residential Satisfaction in China’s Informal Settlements: A Case Study of Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Urban Geography, 34(7), 923–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.778694

- Li, K., Zhang, Y., & Zhao, L. (2016). Outdoor thermal comfort and activities in the urban residential community in a humid subtropical area of China. Energy and Buildings, 133, 498–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.10.013