Abstract

The influx of the Paris Accord on Climate Change and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development have reiterated the need to reconsider how extractive companies manage their supply chains and see how well they balance economic value, social equity and environmental friendliness, especially in the context of an emerging economy. The purpose of this article is to build a conceptual model that examines the relationship between sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) practises and firm performance (FP), as well as the mediating role of green performance (GP). A quantitative approach and survey design have been used to garner data from the extractive industry in Ghana. Our hypothesised relationships have been tested using the variance-based structural equation modelling (SEM) and Smart-PLS software version 3.3.1. The results have shown that SSCM practises such as green purchasing, reverse logistics, internal environment management and environmental corporation positively relate to FP. Our probing results have further shown that GP significantly mediates the relationship between SSCM practises and financial performance (FP). The practical implications of the article include the emergence of an integrated baseline model that explains the symbiotic relationships between SSCM practises, environmental factors and firms’ performance. Moreover, policymakers, practitioners and advocacy groups are able to identify sustainable factors that affect firms’ performance under safe environmental conditions in order to advance the adoption and realisation of sustainable consumption and production practises as well as climate mitigation actions within Ghana’s extractive industry, in accordance with sustainable development goals (SDGs) Twelve and Thirteen.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

The emergence of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Accord on Climate Change have reiterated the need to reassess supply chain management practices of extractive companies, and determine the extent to which such practices ensure harmony among environmental friendliness, social equity and economic value. In recent years, companies have increasingly integrated sustainability into their production and operations. The proportion of Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 companies that publish separate sustainability reports has increased significantly from 20% in 2011 to 82% in 2016. More than 90% of impacts on natural resources such as air, land and soil can be attributed to supply chain management. Moreover, the supply chain is responsible for more than 80% of greenhouse gas emissions from consumer goods (Genovese et al., Citation2017; Kähkönen et al., Citation2018; Wang & Dai, Citation2018; Tipu & Fantazy, Citation2018; Croom et al., Citation2018; Raza et al., Citation2021). Sustainability has become an important concept that encompasses various aspects of society, including the business environment. Magazine covers often feature alternative energy sources, concerns about climate change, and symbolic images of polar bears trapped in precarious ice sheets. The growing importance of sustainability is influenced by a number of factors, including the relationship between energy supply and demand, improved scientific understanding of climate change, and increased publicity for environmental and social initiatives by organisations. Managers are prioritising these issues because of the growing expectations of their stakeholders, such as customers, regulators, NGOs and employees (Pakdeechoho & Sukhotu, Citation2018; Sajjad et al., Citation2019; Ni & Sun, Citation2019; Amoah et al., Citation2021; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Possumah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021).

These stakeholders expect organisations to effectively address and manage environmental and social issues that affect their operations. Managers in sustainable supply chains have the potential to influence environmental and social outcomes either positively or negatively. Organisations can achieve this through a variety of methods, such as reverse logistics, green procurement, internal environmental management and environmental integration. Supply systems have been affected by sustainability concerns, environmental management practices and the circular economy of green supply systems. New ideas have begun to emerge in the literature, including concepts such as circular, green, flexible, responsible and sustainable supply chains. In addition, companies can use product life cycles to facilitate collaborative processes with customers and stakeholders and to achieve sustainable social goals (Amoah et al., Citation2021; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Possumah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021). The extractive industries produce three types of minerals – metals, industrial minerals and fuels – and are considered by all countries to be essential for maintaining and improving living standards (National Academy Press [NAP], 2002). This study is limited to extractive activities. Extractive largely encompasses the extraction of raw materials from the earth’s crust. It encompasses the entire life cycle, from extraction to production and disposal, and may include post-extractive land use. This requires the involvement of a range of stakeholders representing a broad spectrum of economic sectors and institutions that support the research and development sector. The development of new technologies benefits all key elements of the extractive industry, such as exploration, extraction (the actual recovery of material from the ground), processing, and related health, safety and environmental issues (NAP (National Academy Press), Citation2002; Appiah et al., Citation2022; Speczik et al., Citation2020; Mukhsin & Suryanto, Citation2022). To this end, the focus of this study is to reassess the sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) practices of the extractive industry with a focus on extractive.

Deducing from the natural-resource-based view (NRBV) theory and the stakeholder theory (ST), this article aims to develop a baseline model to explain the relationship between SSCM and firm performance (FP) with the mediating role of environmental performance (EP), which is proxied by green performance (GP). With this objective in mind, this article contributes immensely to the existing empirical and theoretical knowledge stock. Foremost, this article is among the very few to develop a contingent model to explain the relationship between SSCM practices, EP and FP, which is consistent with the NRBV theory, which stipulates that firms’ competitive advantage and profitability are dependent on their relationship with the natural environment, while the ST maintains that effective SSCM practices should integrate both primary and supplementary beneficiaries along their value chain for maximum effects. Therefore, it is argued in this article that environmental commitment is a driver of financial performance (FP) (Genovese et al., Citation2017; Kähkönen et al., Citation2018; Wang & Dai, Citation2018; Tipu & Fantazy, Citation2018; Ni & Sun, Citation2019; Mann & Kaur, Citation2019; Sajjad et al., Citation2019; Govindan et al., Citation2020; Raza et al., Citation2021). Second, this study contributes to theoretical development. The article has argued that the combined effects of NRBV theory and ST offer better predictive efficacy as compared to the efforts of the individual theories working in isolation. The integration of the two theories could lead to the development of a new hybrid theory with robust predictability in order to enhance decision-making in the context of extractive industries in emerging economies. Third, this article is among the very few to use the structural equation modelling (SEM) technique to predict environmental behaviour in relation to social equity, economic value or profitability, with a focus on extractive industries, using a cross-sectional survey data. We argue further that although previous studies have reported related findings, the mediating role of GP has not been significantly explored. Finally, this study is conducted in Ghana, where several environmental policies and regulations have been established to protect natural resources, while the actual impacts of these policies are yet to be felt. There is a need to address these knowledge gaps by answering the following questions:

What is the mediating role of GP in the relationship between SSCM practices and FP in the extractive sector?

To what extent do SSCM practices impact FP in the Ghanaian extractive sector?

To what extent does GP impact FP in the Ghanaian extractive sector?

The rest of the article has been reported as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical review, empirical review and hypotheses development; Section 3 presents the research methods; Section 4 presents analysis and discussions; and the final section presents the conclusions and implications of the study.

2. Theoretical review

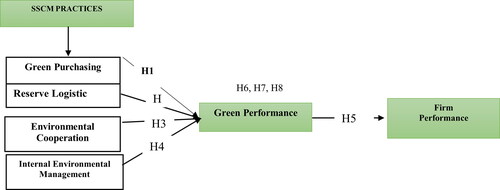

The NRBV and ST have been integrated for robust effect in this study. NRBV theory that stipulates that firms’ competitive advantage and profitability is dependent on its relationship with the natural environment, while the ST maintains that effective SSCM practices should integrate both primary and supplementary beneficiaries along its value chain for maximum effects. A company’s competitive advantage can be explained through pollution prevention, product sustainability and sustainable resource use (Odei, Citation2020). Stakeholder engagement allows for the inclusion of input from environmental organisations in product design and development (Hart & Dowell, Citation2011). However, as Hart and Dowell (Citation2011) note, there is less research on the factors that enable companies to gain a competitive advantage in product safety than in the environmental domain. This highlights the relationships that companies need to build with stakeholders to achieve their business goals (Votano et al., Citation2004); Banerjee et al. recognise that stakeholders are a source of business opportunities and are therefore encouraged to respond (Kassinis, Citation2012; Høgevold et al., Citation2016). We argue that NRBV and ST should be incorporated into a new integrated model explaining the relationship between SSCM practices and, FP. We also argued that an integrated model better explains the relationships described in this study than individual theories. Pagell and Shevchenko (Citation2014) argue that SSCM practices can further improve economic dynamics as well as social and environmental systems through collaborative and coordinated planning, organisation, monitoring and consider it as a process that creates trust and ensures true sustainability. According to Pagella and Wu (2009), SSCM entails the integration of social and environmental issues into organisational planning and practices to improve the social and GP of an organisation and its direct and indirect suppliers and customers, without compromising overall performance. Social and environmental impact assessment is, therefore, an essential component of supply chain management, as it requires comprehensive monitoring and evaluation of supply chain partners. The study is based on the integrated framework presented in .

2.1. Empirical review and hypotheses development

2.1.1. Green purchasing

The primary aim of green procurement is to mitigate negative environmental impacts in the processes of production and transportation by using durable, recyclable and reusable resources. Manufacturing enterprises that have included environmental methods into their procurement procedures have seen several benefits, including but not limited to cost reductions, enhanced public image, and less regulatory obligations. The act of purchasing is seen as a supplementary service to production in the endeavour to achieve a company’s business goals (Green et al., Citation1998). The main goals of the buying function are to optimise the acquisition of raw materials at the most favourable cost, improve customer happiness and increase the overall quality of the finished goods (Wisner et al., Citation2012). The practise of green buying is the deliberate choice of suppliers that provide goods and services that are ecologically sustainable (ElTayeb et al., Citation2010; Yang & Zhang, Citation2012). The primary goal of green procurement is to mitigate negative environmental impacts throughout the production and shipping processes by using durable, recyclable, and reusable products. The promotion of sustainability is closely linked to green buying, since the nature of goods and their influence on the environment are strongly interconnected (Miemczyk et al., Citation2012). Green purchase encompasses the procurement of goods or services that have minimum adverse effects on the environment. Additionally, it entails the demonstration of social responsibility and ethical concerns, all while maintaining price comparability. The concept of green purchasing pertains to the acquisition of ecologically sustainable resources in order to fulfil an organisation’s need for eco-friendly items (Sarkar, Citation2012). Green purchase is a strategic operational process that seeks to minimise waste generation and makes material selections in accordance with established environmental criteria. Green purchase as environmentally responsible purchasing, is the deliberate and strategic process of choosing and acquiring goods and services that successfully mitigate negative environmental impacts throughout all stages of their life cycle. This includes considerations such as manufacture, shipping, use, recycling and disposal. From the ongoing, the article proposes as follow:

H1: There is a significant and positive link between green purchasing and GP

2.1.2. Reverse logistic

Reverse logistics is the term used to describe the systematic administration and treatment of various items, such as equipment, goods, components, materials or complete technological systems with the purpose of recovering them. Reverse logistics refers to the logistical activities that are involved in the processes of recycling, waste management and the safe handling of hazardous materials. Additionally, it encompasses other operations pertaining to source reduction, recycling, material replacement, reuse and disposal (Stock, Citation1992). Pohlen and Theodore Farris (Citation1992) argued that reverse logistics entails systematic procedure of transporting products from end-users back to manufacturers within a distribution network, while adhering to marketing guidelines. The field of reverse logistics involves the thorough administration and proper disposal of waste materials, including both hazardous and non-hazardous substances, that originate from packaging and other goods. The concept of reverse distribution pertains to the occurrence whereby the movement of products and information deviates from the conventional direction of logistical operations. In their seminal work, Rogers and Tibben-Lembke (Citation1999) present an extensive elucidation of the concept of reverse logistics. This encompasses a thorough examination of the overarching goal and the multiple stages entailed in the effective management of the movement of raw materials, in-process inventory, finished goods, and related information from the point of consumption to the point of origin. The main objective of this method is to reclaim value or guarantee appropriate disposal. Reverse logistics is a term that encompasses the strategic management of the flow of raw materials, inventories in various stages of processing, and final products, from their original point of use or distribution, to a designated site of recovery or proper disposal. Based on the above, the following hypotheses are formulated in this study.

H2: There is significant and positive link between reverse logistic and GP

2.1.3. Environmental cooperation and GP

Environmental cooperation encompasses the concerted efforts and collaborative initiatives undertaken by governments throughout the globe with the aim of fostering sustainable global development. The concept of cooperation extends beyond the provision of one-sided assistance from wealthy countries to underdeveloped countries. The process is the establishment of mutually beneficial relationships aimed at improving the overall welfare of people on a global scale, especially in light of the increasing interconnectedness of nations. According to Conca (Citation2000), the establishment of environmental cooperation has the potential to act as a catalyst for the reduction of tensions, promotion of collaboration, facilitation of demilitarisation and ultimately, the nurturing of peace. The impact of environmental cooperation on peace may be both advantageous and disadvantageous. The lack of violence is considered a negative consequence; however, the integration of social groupings is seen as a beneficial outcome (Ide & Scheffran, Citation2014; Schoenfeld et al., Citation2015). The establishment of environmental cooperation has the ability to facilitate symbolic reconciliation across various social groups, which may ultimately result in a decrease in instances of violence over an extended period of time. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that the aforementioned impact may not manifest instantaneously, since it necessitates a significant amount of time to create enhanced symbolic relationships (Barquet et al., Citation2014). It is expected that environmental cooperation would result in reciprocal advantages and promote reconciliation by promoting cross-border communication and trust-building among governmental and non-governmental actors (Carius, Citation2006; Conca & Dabelko, Citation2002; Maas et al., Citation2013). The construction of sustainable peace may be facilitated by environmental cooperation, since it has the potential to rectify perceived disparities in the access and distribution of natural resources (Harwell, Citation2016; Kashwan, Citation2017). The ecological cooperation offers a promising strategy for promoting collaborative efforts across borders, beyond the confines of commercial relationships that are often characterised by limitations and divisions. Based on the above, the following hypotheses are formulated in this study.

H3: There is significant and positive link between environmental cooperation and GP

2.1.4. Internal environmental management

Internal environmental factors and its interconnection with the practise of green procurement. Internal EP pertains to the improvement of an organisation’s EP. The backing of top management plays a critical role in the improvement of EP (Sony, Citation2019). The internal environment pertains to the components inside an organisation that are susceptible to being affected by or exerting an effect on the organisation’s choices, actions and decisions. The aforementioned statement pertains to a constituent element within the wider context of the corporate milieu. Waterman et al. (Citation1980) claim that the internal climate of a company is a pivotal factor in attaining enhanced performance and effectively executing change initiatives. The internal environment pertains to the controllable factors inside an organisation that have a direct impact on its performance. The internal environment of an organisation comprises variables that are unique to the company and exert influence on its capacity to accomplish goals, formulate and implement a viable strategy, and ultimately enhance its performance (Ghani et al., Citation2010). The internal environment pertains to the controllable factors inside an organisation that have a direct impact on its performance. The determinants that contribute to a firm’s resources and capabilities include financial resources, information and knowledge, the firm’s capabilities, incentives, organisational demographics (such as size and inter-institutional links), the company’s objectives and goals, and workers’ talents. The strengths and weaknesses of a firm are influenced by internal environmental variables. The internal environment of an organisation encompasses a multitude of aspects that contribute to the establishment of a conducive atmosphere for the business to achieve its objectives (Tolbert & Hall, Citation2009; Pearce & Robinson, Citation2013; Zibarras & Coan, Citation2015). Based on the above, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H4: There is significant and positive link between internal environmental management and GP

2.1.5. Green performance and financial performance

The fourth research hypothesis predicts a relationship between GP and FP. The level of GP provides important information about environmental impact, environmental compliance and organisational structure (Veleva & Ellenbecker, Citation2000) and indicates the effectiveness and efficiency of a company’s GP (Chuang & Huang, Citation2018). GP is a company-wide process (Green Wave theme, Integrated Management Initiative) that contributes to the ability of employees to best fulfil the company’s values, goals and objectives (Wang, Citation2019). In addition, environmental sustainability includes using environmentally friendly ingredients in products, reducing pollution, reducing carbon emissions and waste, promoting energy conservation, increasing resource efficiency and reducing the use of environmentally harmful materials. As reported by Zhu et al. (Citation2010) and (Song et al., Citation2018), the concept of eco-efficiency refers to the amount of environmental damage caused by a firm’s activities, where less damage means higher eco-efficiency and vice versa. Previous studies (Wang & Sarkis, Citation2013; Pimenta & Ball, Citation2014; Croom et al., Citation2018) have confirmed the link between eco-efficiency and economic performance. In view of the arguments presented herein, the study hypothesises as follow:

H4: There is a significant and positive relationship between GP and FP

2.1.6. Environment (green) performance as a mediator

GP encompasses practices that relate to environmental policies and concerns of a company. It is seen as the commitment towards environmental responsibilities including companies’ commitment towards adopting International organisation for Standardisation (ISO, 14000) for effective environmental management. GP involves the interconnectivity between people, planet and profit. Within the broader context EP refers to, among other things, the use of renewable resources, improved energy and water efficiency, reduction of air and greenhouse gas emissions, increased reuse and recycling, and reduction of hazardous waste and toxic pollutants. GP encompasses the comprehensive assessment of an organisation’s environmental impact, which includes factors such as carbon emissions, waste generation, and natural resource utilisation. GP management involves assessing employees’ performance in the context of green management practices and providing feedback on their performance in this domain (Zibarras & Coan, Citation2015). The sustainable performance of an organisation refers to its ability to meet the needs and expectations of customers and other stakeholders consistently over a long period of time. This is accomplished through the implementation of efficient management practices, increased staff awareness within the organisation, and the utilisation of appropriate enhancements and innovations. From the argument herein, the article contend that GP creates sustainable platforms for the overall FP to flourish. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H5: GP has positive and significant relationship FP

H6-9: GP significantly mediates the link between SSCMP and FP

2.1.7. Effects of extractive activities

Mensah et al. (2015) studied the environmental impact of extractive. The study found that extractive, especially illegal artisanal extractive (Galamsey), destroys environmental resources such as water, soil, landscape, vegetation and ecosystems. The report states that the region’s major rivers are heavily polluted, partly due to illegal artisanal extractive and the land around the mines is degraded and eroding and has lost its potential as agricultural land. The destruction of essential soil organisms and the disruption of stable soil communities leads to a reduction in soil organic matter, macronutrients important for plant growth and fertility and soil fertility. In the long term, this will inevitably lead to food shortages in much of Ghana. Annan (Citation2024) assessed the impact of small-scale (artisanal) gold extractive and its socio-economic impact on the population in Ghana. The results showed that young people aged between 21 and 30 years were more likely to engage in illegal extractive. The influx of migrant workers has led to an increase in the cost of living, especially food prices and housing rents, fragmentation of communities and disruption of cultural values. There is evidence that farmland has been destroyed, affecting agriculture and food production. As a result, dug-out pits have become a breeding ground for mosquitoes and a death trap for people. The study therefore stresses that illegal logging should be formalised so that it can be strictly controlled and enforced. In addition, local people should be involved in policy-making and environmental issues to reduce the risk of land degradation. Some solutions are easy to implement, such as restoring soils and pasture on site, removing excess waste, proper waste management, controlling construction sites, replanting trees and protecting natural forests. To reduce the environmental impact of the extractive industry, extractive companies should consider the use of sustainable waste management facilities and practices. Where possible, arrangements should also be made to restore the local environment to a natural and habitable state after mine closure. Reducing costs and improving the efficiency of the extractive process will also contribute to reducing the negative environmental impacts of extractive.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Overview of Ghanaian extractive industry

The country has had a stable multi-party democracy for more than 20 years, and its relatively well-known and attractive mineral resources have attracted large investments in extractive. Extractive plays a key role in the country’s economy, with gold accounting for more than 90% of total economic output. Ghana ranks second among African countries and ninth in the world in terms of gold production. In 2011, gold extractive accounted for 38.3% of direct corporate revenues, 27.6% of government revenues, and 6% of GDP. Ghana’s economy is highly dependent on the extractive sector, which attracts more than 50% of foreign direct investment and accounts for more than a third of export earnings (Mensah et al., Citation2015; Annan et al., Citation2024). Extractive plays an important role in generating tax revenues, contributing to a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and supporting employment. Large-scale extractive employs 28,000 people, while gold, diamonds, sand and small-scale extractive employ over one million people. Ghana reached a historic milestone in gold production in 2011, producing 3.6 million ounces, an all-time hig (Abudu and Sai, Citation2020; Appiah, Possumah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah et al., Citation2022). This sector was chosen because extractive has a significant impact on the Ghanaian economy. Extractive is a long-term activity, and the importation and use of hazardous chemicals in extractive are closely linked to environmental and climate issues.

3.2. Research paradigm and design

This study used quantitative research methods to develop a contingent model to examine the relationship between SSCM practices, GP and FP in the extractive industry in Ghana. Previous studies (Appiah, Possumah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021) have shown that quantitative research methods are suitable for ontological research based on objectivism. This study utilises a quantitative research strategy that incorporates numerical models, statistical data, hypothesis testing and the objectivist paradigm (Saunders et al., Citation2012; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021). In terms of approach to theory development this article utilised deductive reasoning, where decision making start from specific hypothesis development based on existing theories and empirics before generalisations are made. This assumption is very consistent with the quantitative research approach and positivism paradigm.

3.3. Population and sampling procedures

The target population for the study comprises larger, medium and small-scale extractive companies in Ghana. The study specifically focused on extractive companies within the Ashanti, Bono, Ahafo, Western and Eastern Regions of Ghana. These five regions, account for over 70% of extractive activities in Ghana. Inclusion criteria used for the selection of participants include: (1) Companies which has been duly registered with traceable records with the Registrar General Department, (2) companies which have been in operation for 5 years and greater, (3) companies with appropriate permit from the Minerals Commission and (4) the company must be in the five regions selected for the study. The rule of ten (10) has been used to estimate the required sample size for the study as proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2014) particularly for studies involving SEM. In principle the total number of paths directed towards a latent variable in a model are multiple by 10 (e.g., 5*10 = 50). Using this technique 50 sample size would have been adequate for the study. Meanwhile, for robustness purpose 245 sample size has been used.

3.4. Data collection instrument

The instruments for the data collection have been adopted and improved from previous related studies. presents the name of the constructs, source and number of items. This article has used cross sectional technique. Large, medium and small companies often use this method to understand and analyse new trends, market needs, perceptions and attitudes (Saunders et al., Citation2012; Zikmund et al., Citation2012). Survey strategy has been used in previous studies particularly when (1) there is no access to secondary data, (2) for cost effectiveness purposes, (3) economics of time and (4) tendency to cover wider range of participants. Where possible, pre-validated scales were used to increase the reliability and validity of the measurements. Both online and face-to-face approaches were used. The online approach involved the used GOOGLE form which where shored with the target respondents through their emails. While the face to face were presented in sealed envelopes to the respondents and collected them later after several reminders were sent to the respondents. The effectiveness of the questionnaire instrument in saving both money and labour led to its eventual adoption. To address the problem of non-response, approximately 300 questionnaires were sent out to potential participants, of which 275 were subsequently returned. In order to obtain reliable results, all suspicious responses had to be removed from the original data. This strategy resulted in the elimination of forty-five (45) responses. After further verification, ten (10) responses were discarded because they were completed by undesirable participants. A total of 245 questionnaires were eventually retained and used for data analysis. The questionnaire was structured into two main sections covering the main themes and demographic profile. The main themes addressed in the survey were: SSCM practices, EP and economic performance in the Ghanaian extractive industry. In terms of demographic profile, geographical location, company type, company age and company size were considered. While a five-point Likert-type scale was used to measure the main themes, a categorical scale was used to measure the demographic information. The questionnaire was pre-tested with 20 randomly selected respondents from the Kumasi metropolis but the researchers found no significant problems with the instruments. The final questionnaire was structured into four sections. The first three sections focused on SSCM, GP and FP, respectively, while the last section focused on demographic questions.

Table 1. Name of constructs, sources and measurement scales.

3.5. Ethical consideration

This study involved human participation as ethical screening was duly followed. These included informed consent, respect for human rights, protection of participants from harm, anonymity and professional integrity. Respondents were free to decide on their participation. No participant was coerced to participate in the study. Participants’ rights and freedom were respected throughout the study. The researchers ensured that participants were not harmed during their participation in the study. The responses obtained were anonymous. Data are available upon request for further academic work.

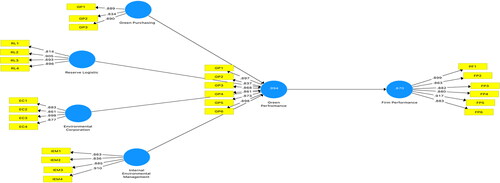

3.6. Data analysis techniques

Smart Partial Least Square (Smart-PLS version 3.3.1) was used to analyse cross-sectional data collected from extractive companies in Ghana. The analysis consisted of two phases. After assessing conceptual validity using convergent and discriminant validity, estimation of sample proportions and hypothesis testing were initiated (Hair et al., Citation2014). A SEM was constructed to evaluate the hypotheses. Structural validity was assessed in this study using convergent and discriminant validity. Structural validity refers to the extent to which a test designed to assess a particular structure (e.g. stability) accurately assesses that structure. Convergent validity is assessed using composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha. To test the hypotheses of the study, 500 bootstrap split samples were used to calculate T-scores and path coefficients. Hair et al. (Citation2014) introduced these methods for structure estimation. In 2014, Hair et al. proposed the use of SEM to study mediation. They argue that SEM is superior to other types of traditional regression analysis (first-generation analysis) because it allows the simultaneous study of multiple exogenous mediating variables and endogenous outcome variables. and provide further details on the measurement model and structural model.

4. Results

4.1. Profile of the firms’

As indicated in the demographic profile table (see Supplementary Appendix A) slightly below half (48.2%) of the participants indicated their firm size was 10–49, 24.5% indicated 50–99 firm size, 25.2% indicated 1–9 firm size and the least 2.1% indicated 100+. Moreover, 39.2% of the participants indicated their firms were aged between 10 and 14 years, 30.2% of the extractive firms were aged between 15 and 19 years, 20.0% of the firms were aged between 5 and 9 years, 5.3% were aged below 5 years and, the remaining 5.3% of the extractive firms were aged above 20 years. With regards to firms’ location, 44.5% of the extractive companies were located in the peri-urban areas, 30.6% indicated the rural areas and 24.9% in the urban areas. Furtherance, over half (63.3%) of the extractive companies in Ghana are Ghanaian owned and the remaining 36.7% are foreign owned. Concerning job designation, 20.8% of the participants indicated they were inventory officers, 18.4% indicated procurement officers, 17.1% indicated transport officers, 14.3% indicated supply chain officers, 12.7% indicated finance officers, 7.3% indicated other designation, 6.9% and 2.4% indicated they were CSR officers and accountant, respectively.

4.2. Descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

The results of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), including the composite means and standard deviations, are presented in . The descriptive results of the survey show that the mean of each composite indicator exceeded 4.0 and the respective standard deviations were less than 1. With some exceptions, the results indicate that a significant proportion of respondents agreed with most of the items in the questionnaire. Some assumptions are necessary for EFA. One possible criterion is that the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) score should be equal to or greater than 0.5. Bartlett’s overall test should yield statistically significant results. As shown in , the KMO test score was consistently greater than 0.50 for the structures. In addition, each of Bartlett’s sphericity tests was found to give statistically significant results (p value = 0.000), and the element loadings were found to be significantly above the recommended threshold of 0.60. The results of this study support the preliminary validity of the designs. Construct validity was assessed in this study by exaextractive convergent and discriminant validity, as shown in . Similar to stability assessment, construct validity refers to the extent to which a test accurately assesses the particular construct it is designed to assess.

Table 2. EFA on SSCM practices, green performance and FPs.

Table 3. Convergent validity.

4.3. Discriminant validity and convergent validity (construct validity of the model

Convergent validity is assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and Cronbach’s reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha and CR values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 in all cases. In the case of convergent validity, it should be assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and CR. To assess convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were calculated for the extracted data. The results showed that the AVE values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.5. Discriminant validity was assessed by two separate methods. The square root of the underestimated AVE value was used to assess discriminant validity. The square root of the AVE was found to be greater than the intraclass structural correlation value, as shown in . presents results on discriminant validity. Cross-validation was utilised to establish discriminant validity; in this process, greater weight was ascribed to each item in comparison to the other constructs. The results have indicated adequate degrees of convergent and discriminant validity, thereby implying their dependability. The MTMT values listed in , which are all less than 0.90, further support the variances’ discriminant validity. To evaluate multicollinearity, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was utilised. According to the findings, the composite VIF scores varied between 1.03 and 3.45, with each score falling below the critical value of five (5) as shown in . It appears from this result that multicollinearity has little impact on the model.

Table 4. Discriminant validity Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 5. HTMR criterion.

Table 6. Multicollinearity assessment using VIF test.

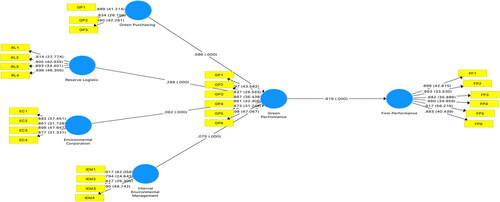

4.4. Path coefficient and hypotheses testing

The results presented in are divided into two parts. The part one focuses on the direct effects of the model while the part two focuses on the indirect effect of the model (mediating effects). As shown in , the models have stronger predictive power reaching between 67% and 99%. The Q-square values further confirm that the models have predictive relevance. The results show that environmental corporation has significant and positive effect on EP (beta = 0.62, p value = 0.000), while green purchasing also shows a significant and positive effect (beta = 0.586, p value = 0.000). Social sustainability does not show a significant effect on EP (beta = 0.116, p value = 0.000), internal environmental management shows a significant and positive effect on EP (beta = 0.075, p value = 0.000), reverse logistics has significant and positive effect on EP (beta = 0.075, p value = 0.000). Moreover, EP has significant effect on FP (beta = 0.075, p value = 0.000).

Table 7. Path coefficients and hypothesis testing.

Table 8. Construct crossvalidated redundancy (Q2 (=1-SSE/SSO), R-square (R2) and adjusted R-square.

In terms of mediating effects, reverse logistics was found to significantly mediate the relationship between FP and EP (beta = 0.236, p value = 0.000). In addition, the internal environment corporation was found to have a significant mediating effect on the relationship between FP and EP (beta = 0.061, p value = 0.000). Again, green purchasing was found to have a significant mediating effect on the relationship between FP and EP (beta = 0.479, p value = 0.000). Finally, environmental corporation was found to significantly mediate the relationship between FP and EP (beta = 0. 051, p value = 0.001). All the eight (8) hypotheses in the model have been supported. and , respectively, provide the R-square values and path – coefficients of the model.

5. Discussions

The influx of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Accord on Climate Change have reiterated the need to re-assess the supply chain management practices of extractive companies and determine the extent to which such practices ensure harmony among environmental friendliness, social equity and economic value. The term is generically used to indicate the integration of economic and environmental viable practices within a supply chain process or lifecycle, such as product development, material extraction, manufacturing, packaging, distribution, transportation, inventory consumption and reverse logistics and disposal (Lu et al., Citation2018; Machete, Citation2019; Miemczyk & Luzzini, Citation2019; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Mukhsin & Suryanto, Citation2022). The primary aim of SSCM in the context of the extractive industry is to maintain environmental, economic and social stability in order to ensure long-term sustainability in the sector (Pagell & Shevchenko, Citation2014; Hong et al., Citation2018; Sikhimbayev et al., Citation2019; Wang, Citation2019). To address this knowledge deficit, this article aims to develop a mediated model to explain the relationship between SSCM practices and FP with the mediating role of GP. The results have been presented in two folds. The first part presents the results on the direct effect without the mediating variable while the second part presents results on the indirect effect.

5.1. The relationships between SSCM practices, green performance (GP) and financial performance (FP)

The study has revealed that SSCM practices largely impact on GP and FP. The study has established that SSCM practices such as green purchase, reverse logistics, internal environment management and environmental corporation positively relate to FP. These results are partly consistent with previous findings. Currently, SSCM practices of the extractive companies should be regarded as dynamic capabilities to implement and apply sustainability in their management and procurement processes (Miemczyk & Luzzini, Citation2019; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Mukhsin & Suryanto, Citation2022). For example, previous research (Pagell & Wu, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2019) reported that some SSCM practices focus on actual sustainability in supply chains. In contrast, many other authors argue that SSCM is a practice that aims to maintain environmental, economic and social stability to ensure long-term sustainability (Miemczyk & Luzzini, Citation2019; Nagariya et al., Citation2021). It has been confirmed in this study that SSCM practices of companies develop customer and supplier relationships and business processes that cross organisational boundaries and are systematically integrated to achieve societal goals (Mukhsin & Suryanto, Citation2022). To this end, SSCM practices which is imbued with environmental commitment, social equity and economic value has potential of influencing GP and subsequently FP. The growing importance of sustainability is influenced by a number of factors, including the relationship between energy supply and demand, improved scientific understanding of climate change, and increased publicity for environmental and social initiatives by organisations. Managers are prioritising these issues because of the growing expectations of their stakeholders, such as customers, regulators, NGOs, and employees. These stakeholders expect organisations to effectively address and manage environmental and social issues that affect their operations. Managers in sustainable supply chains have the potential to influence environmental and social outcomes either positively or negatively. Organisations can achieve this through a variety of methods, such as reverse logistics, green procurement, internal environmental management and environmental integration.

5.2. Mediating role of GP on relationship between SSCM practices and FP

The survey results have revealed that GP largely mediate the dimensions of SSCM practices and FP. Specifically, the study has revealed that GP significantly mediate the relationship between environmental sustainability and FP. Again, the study has found that GP significantly mediate the relationship between economic sustainability and FP. These results agree with existing reports to a larger extent. Because GP provides important information on environmental impacts, environmental compliance and organisational structure (Gupta & Gupta, Citation2021), as well as information on the effectiveness and efficiency of a company’s GP. GP also deals with the extent to which employees participate in organisational processes (Green Wave theme, integrated management initiatives) to develop the capacity to best implement the organisation’s values, goals and objectives (Wang, Citation2019). Furthermore, environmental sustainability should therefore be seen as the impact of an organisation’s activities on the environment (Klassen & Whybark, Citation1999). Furthermore, environmental sustainability includes using environmentally friendly ingredients in products, reducing pollution, reducing carbon dioxide and waste, promoting energy conservation, using resources more efficiently and reducing the use of environmentally harmful materials (Zhu et al., Citation2010; Wang & Sarkis, Citation2013; Pimenta & Ball, Citation2014; Croom et al., Citation2018) and refers to the extent to which an organisation’s activities harm the environment; less harm means better GP and vice versa. The article has discovered and reaffirmed that extractive companies which invest strategically on environmental-related issues while creating economic values inspire greater green culture and performance. The GP will eventually yet financial benefits in the long run which is consistent with NRBV theory.

6. Conclusions and implications

In the world over, policymakers, practitioners, environmental advocacy groups and academicians have upscaled their commitment to ensuring a balance between people, planet and profit by encouraging sustainable consumption and production as enshrined in the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. In view of this, our article has reiterated the need to re-assess the supply chain management practices of extractive companies and determine the extent to which such practices ensure harmony among environmental friendliness, social equity and economic value. The study has established that SSCM practices such as green purchase, reverse logistics, internal environment management and environmental corporation positively relate to FP. Our indicative results have further shown that GP significantly mediates the relationship between SSCM practices and FP. The study concludes that SSCM practices drive EP and subsequently lead to overall performance. Thus, the growing importance of sustainability is influenced by a number of factors, including the relationship between energy supply and demand, improved scientific understanding of climate change, green purchasing, reverse logistics, internal environmental management and increased publicity for environmental and social initiatives by organisations. Managers are prioritising these issues because of the growing expectations of their stakeholders, such as customers, regulators, NGOs and employees (Pakdeechoho & Sukhotu, Citation2018; Sajjad et al., Citation2019; Ni & Sun, Citation2019; Amoah et al., Citation2021; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Possumah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021). The implications of these results have been presented in the next section.

6.1. Theoretical implications

The emerging theoretical contributions of the study include the development of an integrated model comprising NRBV and stakeholders’ theory called S-NRBV. The new integrated baseline model will explain the symbiotic relationship between SSCM practices and firms’ performance, with a focus on the extractive industry in Ghana, where such studies largely remain unexplored and ambiguous at best. Thus, the study successfully developed and tested a contingent model linking SSCM practices, GP and FP in the context of the extractive operational value chain. The ST in the integrated model explains the purpose of firm existence as well as value creation, while the NRBV is more concerned with the competitive advantage firms enjoy for choosing to embark on environmental sustainability practices. The study has recognised that GP indirectly intervenes with SSCM practices to exert significant influence on FP. Avalanches of prior studies (Miemczyk & Luzzini, Citation2019; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Mukhsin & Suryanto, Citation2022) suggest that SSCM is one of the gateways to ensuring that firms activities do not negatively impact the environment or social stability while tempting to create economic value.

6.2. Policy and practical implications

Meanwhile, the SSCM practices of the extractive industry have not received much empirical attention. SSCM practices are dynamic capabilities of companies that show how companies implement and apply sustainability in their management and procurement processes (Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Mukhsin & Suryanto, Citation2022). In other words, the relationship between SSCM practices is not directly felt, but the presence of GP enhances the relationship. Policymakers, practitioners and advocacy groups are able to identify sustainable factors that affect firms’ performance under safe environmental conditions in order to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns (SDG 12) and climate change (SDG13) in the Ghanaian extractive industry. Moreover, a study has revealed that the management of extractive companies should integrate SSCM practices in order to improve GP, which could subsequently lead to FP. The study has developed a more robust strategy for extractive companies to enhance their SSCM practices, renew their environmental commitment, and enhance their economic prospects in the long run. Again, the article further argued that the integrated model is better suited to enhance sustainable development than individual theories. The growing importance of sustainability is influenced by a number of factors, including the relationship between energy supply and demand, improved scientific understanding of climate change, and increased publicity for environmental and social initiatives by organisations. Managers are prioritising these issues because of the growing expectations of their stakeholders, such as customers, regulators, NGOs and employees. These stakeholders expect organisations to effectively address and manage environmental and social issues that affect their operations. Managers in sustainable supply chains have the potential to influence environmental and social outcomes either positively or negatively. Organisations can achieve this through a variety of methods, such as reverse logistics, green procurement, internal environmental management and environmental integration. Supply systems have been affected by sustainability concerns, environmental management practices and the circular economy of green supply systems. New ideas have begun to emerge in the literature, including concepts such as circular, green, flexible, responsible and sustainable supply chains (Pakdeechoho & Sukhotu, Citation2018; Sajjad et al., Citation2019; Ni & Sun, Citation2019; Amoah et al., Citation2021; Nagariya et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Possumah, et al., Citation2021; Appiah, Sedegah, et al., Citation2021).

6.3. Limitations and suggestion for future studies

Although the study has contributed tremendously to academic literature (theories and practices), there are a few limitations that need to be taken into consideration. This study focused on the extractive sector without segregating the companies into small, medium and large. Besides, this article employed a cross-sectional survey design, while longitudinal would have been more insightful. The sample size of 245 is still small given the size of the extractive sector in Ghana, including legitimate small-scale extractive groups. Inferring from the limitations above, there is a need to replicate this study in the future by focusing on one group or conducting a comparative study of two or more groups. Besides, a comparative study involving indigenous companies and multinational companies with regards to SSCM practices and environmental sustainability is highly recommended. Also, future studies should consider the possibility of conducting a nationwide survey since this study focused on some selected regions. Moreover, situational and contextual variables such as dynamic capability and leadership commitment should be employed in future studies as moderators to strengthen the relationship.

Author’s contribution

Michael Karikari Appiah: Conceptualisation Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation. Joseph Naah Dordaah: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Aloysius Sam: Writing – review & editing. Newman Amaning: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. All the Authors proofread and approved the final draft.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (64.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Authors agree to make data and materials supporting the results or analyses presented in their article available upon reasonable request.

Construct crossvalidated redundancy (Q2) and quality criteria (R2).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Karikari Appiah

Dr. Michael Karikari Appiah is a Lecturer at the Department of Sustainable Energy Resources. He is a prolific writer with good number of publications. His research interest include; sustainability, sustainable development, energy economics, renewable energy resources management, environmental management and green entrepreneurship.

Joseph Naah Dordaah

Mr. Joseph Naah Dordaah is postgraduate student at the coventry university branch in Ghana. His research interest include; Sustainable and Green Financing, sustainable corporate reporting and corporate social responsibilities.

Aloysius Sam

Dr. Aloysius Sam is a Senior Lecturer at the Kumasi Technical University in Kumasi, Ghana. His research interest include; sustainable and innovative building projects, Energy Efficient Building, sustainable development, and sustainable financing.

Newman Amaning

Newman Amaning is a Senior Lecturer at the Sunyani Technical University at the department of accountancy. His research interest include; Sustainable and Green Financing, sustainable corporate reporting and corporate social responsibilities.

References

- Abudu, H., & Sai, R. (2020). Exaextractive prospects and challenges of Ghana’s petroleum industry: A systematic review. Energy Reports, 6, 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2020.04.009

- Abu Seman, N. A., Govindan, K., Mardani, A., Zakuan, N., Mat Saman, M. Z., Hooker, R. E., & Ozkul, S. (2019). The mediating effect of green innovation on the relationship between green supply chain management and environmental performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 229, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.211

- Amoah, J., Jibril, A. B., Luki, B. N., Odei, M. A., & Yawson, C. (2021). Barriers of SMEs’ sustainability in sub-Saharan Africa: A pls-sem approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge, 9(1), 10–24. https://doi.org/10.37335/ijek.v9i1.129

- Annan, S. T. (2024). The Ban on Illegal Mining in Ghana: Environmental and Socio-Economic Effect on Local Communities. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 12, 153–162. https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.123009

- Appiah, M. K., Possumah, B. T., Ahmat, N., & Sanusi, N. A. (2021). Do industry forces affect small and medium enterprise’s investment in downstream oil and gas sector? Empirical evidence from Ghana. Journal of African Business, 22(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2020.1752599

- Appiah, M. K., Sedegah, D. D., & Akolaa, R. A. (2021). The implications of macroenvironmental forces. and SMEs investment behaviour in the wnergy sector: The role of supply chain resilience. Heliyon, 7(11), e08426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08426

- Appiah, M. K., Odei, S. A., Kumi-Amoah, G., & Yeboah, S. A. (2022). Modeling the impact of green supply chain practices on environmental performance: The mediating role of ecocentricity. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 13(4), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-03-2022-0095

- Barquet, K., Lujala, P., & Rød, J. K. (2014). Transboundary Conservation and Militarized Interstate Disputes. Political Geography, 42(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.05.003

- Carius, A. (2006). Environmental Peacemaking: Environmental cooperation as an instrument of crisis prevention and peace building: Condition for success and constraints. Adelphi.

- Chuang, S. P., & Huang, S. J. (2018). The effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on green performance and business competitiveness: The mediation of green information technology capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(4), 991–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3167-x

- Conca, K., & Dabelko, G. D. (2002). Environmental peacemaking. John Hopkins University Press.

- Conca, K. (2000). Environmental cooperation and international peace. In F. D. Paul and G. Nils Petter (Eds.), Environmental conflict. Westview Press.

- Croom, S., Vidal, N., Spetic, W., Marshall, D., & McCarthy, L. (2018). Impact of social sustainability orientation and supply chain practices on operational performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(12), 2344–2366. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-03-2017-0180

- ElTayeb, T. K., Zailani, S., & Jayaraman, K. (2010). The examination on the drivers for green purchasing adoption among EMS 14001 certified companies in Malaysia. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 21(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410381011014378

- Genovese, A., Acquaye, A. A., Figueroa, A., & Koh, S. L. (2017). Sustainable supply chain management and the transition towards a circular economy: Evidence and some applications. Omega, 66, 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2015.05.015

- Ghani, K. D., Nayan, S., Ghazali, S. A., & Shafie, L. A. (2010). Critical internal and external factors that affect firms’ strategic planning. Journal of Finance and Economics.

- Govindan, K., Rajeev, A., Padhi, S. S., & Pati, K. R. (2020). Supply chain sustainability and performance of firms: A meta-analysis of the literature. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 137, 101923, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.101923

- Green, K., Morton, B., & New, S. (1998). Green purchasing and supply policies: Do they improve companies’ environmental performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 3(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598549810215405

- Gupta, A. K., & Gupta, N. (2021). Environment practices mediating the environmental compliance and firm performance: An institutional theory perspective from emerging economies. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(3), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00266-w

- Hair, F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool for business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hart, S. L., & Dowell, G. (2011). Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1464–1479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310390219

- Harwell, E. (2016). Building momentum and constituencies for peace: The role of natural resources in transitional justice and peace building. In: C. Bruch, C. Muffett & C. Nichols (Eds.), Governance, natural resources, and post-conflict peace building (pp. 633–664). Earthscan.

- Høgevold, N. M., Svensson, G., Wagner, B., Varela, J. C. S., Ferro, C., & Padin, C. (2016). Influence of stakeholders and sources when implementing business sustainability practices. International Journal of Procurement Management, 9(2), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPM.2016.075261

- Hong, J., Zhang, Y., & Ding, M. (2018). Sustainable supply chain management practices, supply chain dynamic capabilities, and enterprise performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 3508–3519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.093

- Ide, T., & Scheffran, J. (2014). On climate, conflict andc: Suggestions for integrative cumulation of knowledge in the research on climate change and violent conflict. Global Change, Peace & Security, 26(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2014.924917

- Kähkönen, A. K., Lintukangas, K., & Hallikas, J. (2018). Sustainable supply management practices: Making a difference in a firm’s sustainability performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 23(6), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-01-2018-0036

- Kashwan, P. (2017). Inequality, democracy, and the environment: A cross-national analysis. Ecological Economics, 131, 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.018

- Kassinis, G. I. (2012). The value of managing stakeholders. Oxford University Press.

- Klassen, R. D., & Whybark, D. C. (1999). The impact of environmental technologies on manufacturing performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(6), 599–615. https://doi.org/10.5465/256982

- Lu, H., Potter, A., Sanchez Rodrigues, V., & Walker, H. (2018). Exploring sustainable supply chain management: A social network perspective. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 23(4), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-11-2016-0408

- Maas, A., Carius, A., & Wittich, A. (2013). From conflict to cooperation: Environmental cooperation as a tool for peace-building. In R. Floyd & R. A. Matthew (Eds.), Environmental security: Approaches and issues (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Machete, F. (2019). A review of the influence of municipal sustainable supply chain management on South Africa’s recycling performance. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 11(5), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2019.1571148

- Mann, S. J. B., & Kaur, H. (2019). Sustainable supply chain activities and FP: An Indian experience. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 24(1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972262919863189

- Mensah, A. K., Mahiri, I. O., Owusu, O., Mireku, O. D., Wireko, I., & Kissi, E. A. (2015). Environmental impacts of mining: a study of mining communities in Ghana. Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 3(3), 81–94.

- Miemczyk, J., & Luzzini, D. (2019). Achieving triple bottom line sustainability in supply chains: The role of environmental, social and risk assessment practices. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 39(2), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-06-2017-0334

- Miemczyk, J., Johnsen, T. E., & Macquet, M. (2012). Sustainable purchasing and supply management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17(5), 478–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211258564

- Muisyo, P. K., & Qin, S. (2021). Enhancing the FIRM’S green performance through green HRM: The moderating role of green innovation culture. Journal of Cleaner Production, 289(2021), Article 125720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125720

- Mukhsin, M., & Suryanto, T. (2022). The effect of sustainable supply chain management on company performance mediated by competitive advantage. Sustainability, 14(2), 818. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020818

- Nagariya, R., Kumar, D., & Kumar, I. (2021). Sustainable service supply chain management: From a systematic literature review to a conceptual framework for performance evaluation of service only supply chain. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 29(4), 1332–1361. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-01-2021-0040

- NAP (National Academy Press). (2002). Evolutionary and revolutionary technologies for extractive. National Academy Press ISBN 0-309-07340-5.

- Ni, W., & Sun, H. (2019). The effect of sustainable supply chain management on business performance: Implications for integrating the entire supply chain in the Chinese manufacturing sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 232, 1176–1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.384

- Odei, S. A. (2020). Does firms’ competitions spur innovations: Exploratory evidence from SMEs and large firms in a transition economy. Advances in Natural and Applied Sciences, 14(2), 211–216.

- Pagell, M., & Shevchenko, A. (2014). Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 50(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.1203710.1108/SCM-12-2013-0444

- Pagell, W., & Wu, Z. (2009). Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 examples. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45(2), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2009.03162.x

- Pakdeechoho, N., & Sukhotu, V. (2018). Sustainable supply chain collaboration: Incentives in emerging economies. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 29(2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-05-2017-0081

- Pearce, J. A., & Robinson, R. B. (2013). Strategic management, formulation, implementation and control. Salemba Empat.

- Pimenta, D. C. H., & Ball, D. P. (2014). Environmental and social sustainability practices across supply chain management – A systematic review. IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems, APMS 2014: Advances in Production Management Systems. Innovative and Knowledge-Based Production Management in a Global-Local World (pp. 213–221). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-44736-9_26

- Pohlen, T. L., & Theodore Farris, M. (1992). Reverse logistics in plastics recycling. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 22(7), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600039210022051

- Prayag, G., Chowdhury, M., Spector, S., & Orchiston, C. (2018). Organizational resilience and financial performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.06.006

- Raza, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Zhu, N., Hassan, Z., Gul, H., & Hussain, S. (2021). Sustainable supply management practices and sustainability performance: The dynamic capability perspective. SAGE Open, 11(1), 215824402110000. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211000046

- Rogers, D. S., & Tibben-Lembke, R. S. (1999). Going backwards: Reverse logistics trends and practices. Reverse Logistics Executive Council.

- Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2019). Managerial perspectives on drivers for and barriers to sustainable supply chain management implementation: Evidence from New Zealand. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(2), 592–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2389

- Sarkar, A. N. (2012). Green supply chain management: A potent tool for sustainability green marketing. Asia-Pasific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 8(4), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319510X13481911

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students (6th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Schoenfeld, S., Zohar, A., Alleson, I., Suleiman, O., & Sipos-Randor, G. (2015). A place of empathy in a fragile contentious landscape: Environmental peace building in the eastern Mediterranean. In F. McConnell, N. Megoran, & P. Williams (Eds.), Geographies of peace (pp. 171–193). I. B. Tauris.

- Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1699–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.04.020

- Sikhimbayev, M., Shugаiроvа, Z., Orynbassarova, Y., & Dzhazykbaeva, B. (2019). Readiness for changes among managers of extractive and metallurgy industry: A case of Kazakhstan. Economic Annals-XXI, 177(5–6), 101–113.

- Singh, A. K., Raza, S. A., Nakonieczny, J., Shahzad, U., & Anu. (2023). Role of financial inclusion, green innovation, and energy efficiency for environmental performance? Evidence from developed and emerging economies in the lens of sustainable development. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 64(18), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2022.12.008

- Song, M. L., Fisher, R., Wang, J. L., & Cui, L. B. (2018). Green performance evaluation with big data: Theories and methods. Annals of Operations Research, 270(1–2), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-016-2158-8

- Sony, M. (2019). Green supply chain management practices and digital technology: A qualitative study. Technology optimization and change management for successful digital supply chains. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7700-3.ch012

- Speczik, S., Pietrzela, A., & Zieliński, K. (2020). Documenting deep copper and silver deposits – investor’s criteria. GórnictwoOdkrywkowe, 1, 43–54.

- Stock, J. R. (1992). Reverse logistics. Council of Logistics Management.

- Tipu, S., & Fantazy, K. (2018). Exploring the relationships of strategic entrepreneurship and social capital to sustainable supply chain management and organizational performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67(9), 2046–2070. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-04-2017-0084

- Tolbert, P., & Hall, R. (2009). Organizations: Structures, processes, and outcomes. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Veleva, V., & Ellenbecker, M. (2000). A proposal for measuring business sustainability: Addressing shortcomings in existing frameworks. Greener Management International, 2000(31), 101–120.), https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.3062.2009.au.00010

- Votano, J. R., Parham, M., Hall, L. H., Kier, L. B., & Hall, L. M. (2004). Prediction of aqueous solubility based on large datasets using several QSPR models utilizing topological structure representation. Chemistry & Biodiversity, 1, 1829–1841. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.200490137

- Wagner, S. M., Grosse-Ruyken, T. P., & Erhun, F. (2012). The link between supply chain fit and financial performance of the firm. Journal of Operations Management, 30(4), 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.01.001

- Wang, C. H. (2019). How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 30(4), 666–683. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-09-2018-0314

- Wang, J., & Dai, J. (2018). Sustainable supply chain management practices and performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(1), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-12-2016-0540

- Wang, Z., & Sarkis, J. (2013). Investigating the relationship of sustainable supply chain management with corporate FP. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(8), 871–888. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2013-0033

- Waterman, R. H., Peters, T. J., & Phillips, J. R. (1980). Structure is not organization. Business Horizons, 23(3), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(80)90027-0

- Wisner, J. D., Tan, K. C., & Leong, G. K. (2012). Supply chain management: A balanced approach (3rd ed.). South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Yang, W., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Research on factors of green purchasing practices of Chinese. E3 Journal of Business Management and Economics, 3(5), 222–231.

- Zhu, Q., Geng, Y., Fujita, T., & Hashimoto, S. (2010). Green supply chain management in leading manufacturers: Case studies in Japanese large companies. Management Research Review, 33(4), 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171011030471

- Zibarras, L. D., & Coan, P. (2015). HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(16), 2121–2142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.97242

- Zikmund, W. G., Babin, J., Carr, J., & Griffin, M. (2012). Business research methods: With qualtrics printed access card. Cengage Learning.