Abstract

This study investigates the outcomes of reforms on the performance of the cotton sector in Ghana and Burkina Faso. These structural and policy reforms have been aimed at promoting competition and enhancing productivity, largely under the pressure of external donor agencies. The study draws on in-depth semi-structured interviews with stakeholders involved in different aspects of cotton value chains in the two countries. In particular, it elicits their perception of how reforms affected six domains (input credit systems, price determination and profit distribution, extension services, research and development, institutional and regulatory systems, and food security) related to the performance of the sector. This is complemented with the analysis of policy documents and annual cotton production statistics pre- and post-reform. Results indicate that reforms in Ghana and Burkina Faso took different directions, and subsequently, generated different outcomes to the six performance domains. Stakeholders in Ghana perceived predominantly negative outcomes, whereas Burkinabe stakeholders perceived both negative and positive outcomes. Regarding price determination for instance, Ghanaian respondents mentioned the lack of transparency in the seasonal price-setting system and the decline in government revenue and farmer profit as direct outcomes of reform actions. Burkinabe respondents cited the guaranteed minimum price, high profit-sharing among farmers, and the favorable price incentives as some positive outcomes of the reforms. The empirical information outlined in this study can be used to identify the positive and negative lessons learnt that can be relevant to stakeholders in the public and private sector, and efforts to help sustain the cotton sector in different parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Public Interest Statement

For millions of rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), cotton cultivation is an important source of livelihoods. Cotton is an integral element of some national economies and a vital element of poverty alleviation strategies. The cotton sector underwent policy and structural reforms in the early 1980s in several SSA countries. Ghana and Burkina Faso have been two of the countries that reformed drastically their cotton sectors, but with very different results. Interviews with multiple stakeholders involved in the cotton sector in the two countries suggest that the reforms had indeed very different outcomes that have deeply influenced the performance of the sector. Burkina Faso is perceived as a success story due to the good performance of the sector following the reforms, there are several challenges that remain. On the other hand, reforms in Ghana failed to improve the performance of the sector. It is important to learn from the divergent reform experiences of the two countries to inform reforms elsewhere. .

1. Introduction

Smallholder agriculture is perhaps the most significant socio-economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and is responsible for the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of households (AGRA, Citation2017; FAO, Citation2014). As a major industrial crop, cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) has played a prominent role in the national economy and rural livelihoods of various African countries for more than a century (Tschirley et al., Citation2010). Even before the colonization of the continent, households and communities cultivated cotton in smallholder settings using simple hand tools and animal traction on mixed cropping systems (Goreux, Citation2004). The system of cotton production changed significantly during the colonial period, with much of the cotton being grown on plantations to satisfy the needs of colonial governments (Kriger, Citation2006). After colonial rule ended, many newly independent SSA countries identified cotton as a critical crop to drive and boost socio-economic development, investing huge amounts of financial and human capital, and developing infrastructure to facilitate its production (Delpeuch & Leblois, Citation2014). In several countries, the cotton sector operated as monopolies.By providing free agricultural inputs catalyzed the development of well-organized cotton systems of production and marketing that incentivized many farmers to get involved in cotton cultivation (Kaminski, Headey, & Bernard, Citation2011).

Presently, cotton production is an important source of foreign exchange earnings and a major contributor to the gross domestic product (GDP) of multiple SSA countries including Burkina Faso, Mali, Benin, Zambia, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Chad (Baffes, Citation2007; Kaminski & Bambio, Citation2009; USDA, Citation2016). For millions of rural households, cotton cultivation remains an important source of livelihoods and sustained cash income, thus making it a vital crop in rural development and poverty alleviation strategies (Hussein, Citation2008). Studies across West Africa have also identified cotton cultivation as crucial in enabling smallholder farmers to enhance their food security (Solidaridad, Citation2016). For example involvement in cotton production can improve access to fertilizers through the credit schemes of cotton companies, and often serves as the sole entry crop for inorganic fertilizers into farming systems (de Graaff, Kessler, & Nibbering, Citation2011; Ripoche et al., Citation2015). However, other studies have contended that cotton competes with food crop production (thus increasing food insecurity) and causes loss of soil fertility (Lele, Van derWalle, & Gbetibouo, Citation1990; Moseley, Carney, & Becker, Citation2010).

The performance of the cotton sector and its contribution to national and rural economies varies between SSA sub-regions. The cotton sector in countries of West and Central Africa have shown continued growth for many years, while in countries of East and Southern Africa growth has been lower (Bassett, Citation2001; Boughton, Tschirley, Zulu, Ofico, & Marrule, Citation2003). Overall, the continent’s share of world cotton exports continues to rise, albeit still slowly (FAOSTAT, Citation2016).

Generally, cotton production in SSA is undertaken mainly by small farmers that cultivate cotton under rain-fed conditions in small land holdings (up to 1–2 ha), and is largely input-intensive (Abbott, Citation2013; Kaminski, Citation2007). The inability of rural farmers to access credit and purchase the necessary agricultural inputs has required strong government intervention through the establishment of state monopolies to regulate and control all sectors of production, especially following the colonial rule (Delpeuch & Leblois, Citation2014).

However in the early 1980s following a series of crises in public monopolies in the cotton sector due to both local and external shocks (i.e., political instabilities, decline in global cotton price), several producing countries in SSA, including those in West Africa, were forced to initiate reform programs (Peltzer & Röttger, Citation2013). These were often under the pressure and direction of international donors such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Berg, Citation1981). In Ghana and Burkina Faso, these reforms were expected to enhance the competitiveness of the sector, through market liberalization as a means of increasing the relative prices of agricultural products (Abbott, Citation2013; Fosu, Heerink, Ilboudo, Kuiper, & Kuyvenhoven, Citation1997). While the approach to (and the timeline of) reforms in the cotton sector has varied between SSA countries, most countries faced international pressure as part of the Structural Adjustment Programme of the 1980s (Delpeuch & Vandeplas, Citation2013).

Although these reforms boosted the performance of the cotton sector in some countries, other countries have seen only a modest improvement (or even a stagnation and continuing decline) due to various factors (Akiyama, Baffes, Larson, & Varangis, Citation2003; Goreux & Macrae, Citation2003). For example, in East and Southern Africa, some countries such as Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe that followed the reform agenda in the mid-1990s enjoyed varied outcomes (Poulton & Maro, Citation2009; Poulton & Tschirley, Citation2009). In West Africa, Francophone countries such as Burkina Faso, Benin, Mali, and Chad, which initiated reforms in the mid-1990s, have often been cited as good examples of reforms as the overall performance of the cotton sector improved (Vitale, Citation2018). Burkina Faso and Mali, for instance, have emerged as two of the most proactive countries in SSA, with regard to the use of biotechnology in the cotton sector (Vitale, Citation2018) and using cotton as an effective strategy to reduce rural poverty. In contrast, Anglophone countries such as Ghana and Nigeria initiated reforms in the 1980s that had the opposite effect, leading to the stagnation or even collapse of the cotton sector (Baffes, Citation2007; Delpeuch & Vandeplas, Citation2013).

However, the apparent success of reform programs in some countries of Western Africa such as Burkina Faso and Mali may have masked key challenges that can be overlooked. Understanding how reforms unfolded in different countries of West Africa and the perceptions of relevant stakeholders about their outcomes, can offer valuable lessons related to the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the cotton sector across SSA.

This study aims to investigate the perceptions of multiple stakeholders in Ghana and Burkina Faso regarding the outcomes of government-led reforms within the cotton sector on its performance and sustainability. We focus on these two countries as the reforms had radically different outcomes, with Burkina Faso considered a success story and Ghana a failure (see above). In this study, stakeholders are defined as individuals, groups, or organizations that can influence or be affected by a decision or policy within the sector (Tschirley et al., Citation2010). Following Tschirley et al. (Citation2010) we focus on the outcomes of cotton sector reforms on (a) input credit systems, (b) pricing determination and profit distribution, (c) extension services, (d) research and development, (e) institutional and regulatory systems, and (f) food security. By eliciting and understanding the perceptions of different stakeholders for outcomes across these six domains, we seek to answer three main questions:

What has been the nature and scope of reforms of the cotton sector in Ghana and Burkina Faso?

How do the relevant stakeholders perceive the outcomes of reforms on the overall productivity and performance of the cotton sector in the two countries?

Do stakeholders’ perceptions of the performance of the sector match up with secondary data about cotton productivity in the two countries?

Section 2 presents an overview of the nature and scope of cotton sector reforms in Ghana and Burkina Faso. Section 3 outlines the methodology and research design for the collection and analysis of primary and secondary data (including the expert interview process and participants). Section 4 presents the main stakeholder perceptions across the six domains introduced above, as elicited through the expert interviews. Section 5 synthesizes the elicited perceptions, and discusses their practical implications and the limitations of this study.

2. Cotton sector reforms in Ghana and Burkina Faso

2.1. Background

For the purpose of this paper, the definition of reforms follows Tschirley et al. (Citation2010), who understood reforms as deliberately chosen changes in the fundamental organization of a sector, and the related changes in the “rules of the game” under which stakeholders operate. The cotton sector has traditionally been managed in several countries of SSA (including Ghana and Burkina Faso), by vertically integrated, state-supported cotton companies (Theriault & Serra, Citation2014). These companies have largely operated under an input credit system by supplying under contract cotton farmers with production inputs such as cottonseeds, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and plowing services on credit; and then the farmers then sell their cotton to the same company for a guaranteed price (Theriault & Serra, Citation2014). This model has more recently given way to more competitive market-based models and hybrid systems in an effort to improve the sector’s productivity and performance (Teft, Citation2004; Tschirley et al., Citation2010). Ensuring a fair, balanced, and stable pricing system is key for sustaining and ensuring that cotton to can contribute to poverty eradication (IMF, Citation2003).

Governments in both Ghana and Burkina Faso faced similar pressures to reform their cotton sectors from the World Bank, generally as part of the Structural Adjustment Programmes of the 1980s (Peltzer & Röttger, Citation2013; Vitale, Citation2018). This was followed with recurring financial crises among cotton companies in the 1990s (Kaminski et al., Citation2011). Ghana initiated its policy and structural reforms in the mid-1980s and Burkina Faso in the early 1990s (Table ). The main structural and policy reforms in both countries were instituted under the direction of the World Bank and IMF, with the main rationale being that the liberalization of the cotton sector would improve its competitiveness (Oxfam, Citation2007).

Table 1. Timeline of major events related to cotton sector reforms in Ghana and Burkina Faso

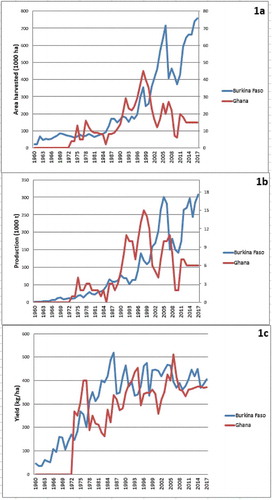

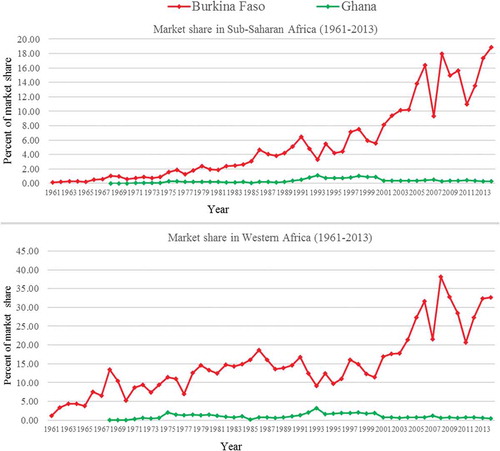

Figures and use data from the online databases of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAOSTAT) and the International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) to highlight key patterns in the cotton sector for the two countries before, during and after the reforms. Overall key indicators such as cotton area harvested (in hectares), production quantity (in tons), yield (in tons/hectare), and market share (percentage) show clear variation over time.

Figure 1. Key cotton production trends for Ghana and Burkina Faso: (a) area harvested, (b) production quantity, (c) yield. Sources: FAOSTAT (Citation2016), ICAC (Citation2016).

Figure 2. Market share of cotton production in Ghana and Burkina Faso: (a) percentage share of production in SSA; (b) percentage share of production in West Africa. Sources: FAOSTAT (Citation2016), ICAC (Citation2016).

In Ghana, there was a steady decline in the area harvested from the mid-1970s through the 1980s, and a marginal increase in the sector’s growth in the mid-1990s (Figure ). Area harvested in Burkina Faso increased progressively after the reforms of the 1990s (Figure ). Seed cotton production in Ghana increased minimally after the implementation of reforms in 1985, peaking at 38,000 tons in 1999, but could not be sustained, declining to around 2,500 tons in 2005 (Figure ) (MOFA, Citation2013). This corresponds positively with area harvested during the same period. The sector in Burkina Faso, on the other hand, enjoyed progressive growth after the implementation of reform programs (Figure ), with substantial growth in seed cotton production, especially in 1994 (54.34%), 1997 (69.33%), 2001 (85.86%), and 2008 (90.98%) (see Figure S2 in Supplementary Electronic Material). Both countries witnessed an increase in yield, corresponding directly to the area harvested, over the study period (Figure ).

However, the market share differed significantly for the two countries, the market share of Burkina Faso being higher than that of Ghana, despite some variation over time (Figure ). For example, in 2008, the cotton production of Burkina Faso accounted for 38.2% of the West Africa’s total, and 18.0% of SSA. In 2014, the regional share of Burkina Faso fell to 32.7%, but its continental share increased to 18.8%. In contrast, the market share of Ghana in West Africa has been consistently very low (less than 1%) and stagnant, with no recognizable increase in growth even after reforms in the sector. Ghana’s low market share can be attributed to deep-rooted challenges and constraints of cotton production including lack of credit, inadequate education and extension services, poor quality seed, late inputs deliver, inadequate labor (ICAC, Citation2008; MOFA, Citation2013) (see Section 4–5).

2.2. Cotton sector reforms in Ghana

The first stages of reforms involved in 1986 the replacement of the parastatal Cotton Development Board (CDB), which had been established in 1968, with the Ghana Cotton Company Limited (GCCL) (Table ). This action paved way for the deregulation of the sector, ushering in a competitive market-based model. The cotton sector subsequently became an attractive investment option for many private companies, and by the 1996–1997 season, more than 12 companies had entered the market The attractiveness of the sector during this period is attributed to the ease of entry facilitated by the availability of funding from the Agriculture Development Bank (ADB), and the favorable world lint prices between 1992 and 1997 (MOFA, Citation2013).

Under the new competitive market-based model, the cotton sector in Ghana experienced a period of boom followed by a period of rapid decline. The boom period occurred between the 1985–1986 and 1996–1997 seasons, when production rose from 956 to 24,953 tons (Figure ). This was largely due to increases in area harvested, from 409 ha to 28,712 ha, and the yields increasing from 504 kg/ha to 870 kg/ha (Figure ). This boom was fuelled by the availability of a local market (i.e. local textile companies that purchased cotton at prices between US$1620 and $2000 per ton), and direct government financial assistance in the form of cotton bonds that drastically reduced the interest burden on the companies. The subsequent period of decline spanned from the 1996–1997 to the 2010–2011 season. According to Ghana’s Ministry for Food and Agriculture (MOFA), this decline had three principal causes: (i) loss of the local market for lint due to the liberalization of the economy and the subsequent influx of cheap textile products, (ii) high cost of inputs in the open market, and (iii) high interest charged by banks to the companies entering the world export market at a time when prices were falling. These forces had highly unfavorable impacts to most companies, with many of them eventually divesting from the cotton sector (MOFA, Citation2013).

To address the decline, the government of Ghana introduced in 2000–2001 a zoning concept, under which the delineated cotton-growing areas were assigned to selected companies. This initiative was led by the Ministry of Food and Agriculture in conjunction with the Cotton Development Project 1 (CDP 1), and with the support of Agence Française de Développement (AFD), the French international development agency. Through this initiative three companies (i.e. Olam, Wienco, Armajaro and their partners) received government concessions to produce cotton in three zones: Upper West, North Central, and Southern North, respectively (MOFA, Citation2013). However, even after this policy intervention, some small-scale private companies that survived the bust of the sector, such as Intercontinental Farms and Plantation Development Ltd., continued their operations. However, despite some initial positive effects, the zoning could not prevent further decline, as by 2010 cotton production had dropped to a very low level of 2500 Mt of seed (MOFA, Citation2013).

In 2011, the government of Ghana, through the Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Ministry for Trade and Industry, and with donor support from the World Bank, embarked on an effort to revive Ghana’s cotton sector. This effort was dubbed the “White Gold Campaign” and was expected to benefit about 100,000 farmers.

2.3. Cotton sector reforms in Burkina Faso

In Burkina Faso, reforms were first considered in 1991 but faced strong opposition and suspicion from local and international stakeholders (Kaminski & Bambio, Citation2009). With little structural change in the existing system, the reforms took a rather gradual approach. Some form of privatization was initiated in 1992 through the Burkinabe Textile Fibers Company (SOFITEX), which is the main government parastatal in the sector (Table ). In 1998, the government reduced its stake in the cotton company by transferring 30% of its shares to a producer organization [National Union of Cotton Producers of Burkina Faso (UNPCB)], and 34% to Développement des Agro-Industries du Sud (DAGRIS). The state retains a 35% stake in SOFITEX, and private citizens hold the remaining 1%.

The second step of the reforms came in 1999 with the formation of a 12-member committee to coordinate the functions of SOFITEX and UNPCB. This included activities such as the determination of farmgate prices, selling prices of inputs, and management of the overall research and development program. The committee consisted of seven producers, three SOFITEX representatives, and two government representatives (Baffes, Citation2007).

The third step involved limited liberalization in 2004 to ease the monopoly of SOFITEX over the national cotton sector. In a similar fashion as Ghana (Section 2.2), the country was subdivided into three zones of cotton cultivation (SP-CPSA, Citation2004):

the western zone, operated by SOFITEX;

the central zone, operated by Burkina Faso entrepreneurs under the name Faso Coton;

the eastern zone, operated by DAGRIS under the title of SOCOMA (Cotton Company of the Gourma).

In 2006, an umbrella organization (Cotton Inter-Professional Association [AICB]) was created to coordinate the actions of all three cotton companies (Baffes, Citation2007).

According to Baffes (Citation2007), the reform process in Burkina Faso reflected the view that the free-riding risks of the cotton sector are high, especially with regard to the provision of inputs (and hence credit recovery) and research and extension services. Burkina Faso’s cotton market is presently structured into three regional monopsonies, with a main state-owned company that accounts for about 90% of cotton purchases and two private firms responsible for the remainder 10% of cotton purchases. During the decade that reforms occurred, cotton output in Burkina Faso increased nearly fourfold, from 64,000 tons in 1995 to almost 300,000 tons in 2005 (Figure ). Currently, cotton is one of the backbones of the Burkina Faso economy (Vitale, Citation2018).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research approach

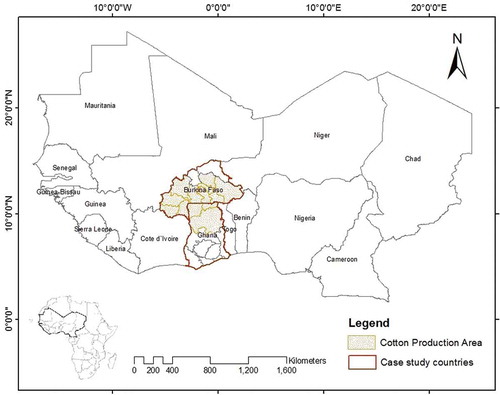

As outlined above, this study examines the outcomes of structural, institutional, and policy reforms on the performance of the cotton sector in Ghana and Burkina Faso (Figure ). The outcomes of the reforms in the cotton sectors of the two countries have been radically different, with the sector flourishing in Burkina Faso and practically collapsing in Ghana (Section 2). A comparative analysis of the experiences of the two countries can offer useful information about the effects of reforms in industrial crop systems. A series of factors can facilitate the comparative analysis between Ghana and Burkina Faso.

Figure 3. Map of Western Africa showing Ghana and Burkina Faso and cotton production zones, prepared by authors.

First, both countries have a long tradition of cotton production through smallholder-based models. Second, the two countries share a common border with their cotton production areas being located in similar agro-ecological zones (Sudan savanna and Guinea savanna). Actually, their cotton production areas are adjacent and have similar climatic conditions that are well suited for cotton cultivation (Section 3.2). Third, the two countries underwent similar reform trajectories at roughly the same period (Section 2). They faced similar external pressures from donors and pricing regimes from the international cotton markets. Fourth, while in both countries cotton production was an important element of rural livelihoods, there is extreme variation post-reform in the contribution of cotton to their national economies in terms of GDP and foreign exchange earnings.

3.2. Study area description

The cotton production zone in Ghana is predominately in the Guinea and Sudan savanna agro-ecological zones, which lie in three administrative regions: Northern, Upper West, and Upper East. These three regions cover approximately 41% of Ghana (Songsore, Citation2011). Cotton is cultivated to a lesser extent in a few communities in the transitional agro-ecological zones, within the Kintampo and Atebubu areas of the Brong Ahafo region (Asinyo, Frimpong, & Amankwah, Citation2015). Agriculture is the main livelihood activity for the predominantly rural population in the cotton-growing area relies of the country. Seasonal food insecurity is a major constraint to livelihood improvement in the three northern regions of Ghana (World Food Programme, Citation2009). Rainfall is unimodal and highly irregular in the cotton production zones, with mean annual rainfall ranging between 1000 and 1100 mm. Cotton production is almost entirely performed under rain-fed conditions, and undertaken through outgrower schemes. In such schemes, under contractual arrangements private cotton companies provide access to inputs (e.g. seeds, fertilizers) and offer markets for smallholder farmers. Family labor is extensively used, with usually larger households adopting cotton production due to its labor intensiveness (Lam, Boafo, Degefa, Gasparatos, & Saito, Citation2017). Simple farm implements such as hoes, axes, and donkey-drawn plows are the main tools used for cultivation. Tractor services for land preparation were previously offered to farmers, but this has ceased in recent years. The average farm size is 1–2 ha, with farmers rotating major staple food crops including maize, sorghum, millet, and legumes (e.g. Lam et al., Citation2017).

Cotton production in Burkina Faso takes place mainly in the Sudanian and Sudano-Guinean agro-ecological zones. The Sudanian zone was the traditional base of cotton production during the French colonial period, but production spread to the Sudano-Guinean zone to the south in the last three decades (Bassett, Citation2001). The average annual rainfall is 600–800 mm in the Sudanian zone, and 800–1100 mm in the Sudano-Guinean zone. The average cotton producer farms about 3.8 ha of cotton in Burkina Faso (Baquedano, Sanders, & Vitale, Citation2010), which is typically produced in a three-year rotation with cotton grown in the first year, followed by successive years of a cereal crop such as maize, sorghum, or millet (Vitale, Ouattarra, & Vognan, Citation2011).

In Burkina Faso, our fieldwork was conducted in three cotton regions (Bobo-Dioulasso, Hounde, and Ouagadougou). The first two regions belong to the SOFITEX area and the third is within the FASO COTON zone. In terms of cotton production, the region of Bobo-Dioulasso, although it consists only of Houet province, ranks first, providing 18% to 20% of SOFITEX’s production and representing 16% of the national total (Vitale et al., Citation2011). Bobo-Dioulasso is located in the heart of the old cotton basin, and its administrative center is quite close to SOFITEX’s headquarters. The Hounde region provides 18% of SOFITEX’s production of SOFITEX and 16% of the national total. This region houses the site where SOFITEX conducts seed multiplication for cotton producers. This site, created in 1958, is commonly called “Boni farm” and is used by the National Institute of Environment and Agricultural Research (INERA) cotton program for carrying out research and trials on cotton varieties, crop rotation, organic fertilizers, and other projects. Ouagadougou belongs to the central region of the country, which is within the FASO COTON cotton zone. This region represents about 5% of the area where cotton is grown in Burkina Faso.

3.3. Data collection

Primary data were collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders in cotton value chains in the two countries. Stakeholders were grouped into four main categories: (a) private sector (i.e. cotton companies), (b) government ministries and agencies, (c) research and development institutions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and (d) farmers and farmer groups. Stakeholders were selected after an initial literature review and institutional analysis of the cotton sector in the two countries (Table ). Easily identifiable stakeholders were purposely sampled at the onset of the study (Overton & Van Diermen, Citation2003), and a snowball sampling technique was used to reach out to other relevant cotton sector stakeholders (Creswell, Citation2014).

Table 2. Details of the stakeholders interviewed for the study

The interviews elicited stakeholders’ perceptions and knowledge about the nature and scope of the reforms in the cotton sector, and their perceived outcome on the industry’s performance and sustainability. Perception questions were asked in relation to the following six domains: (a) input credit systems, (b) pricing determination and profit distribution, (c) extension services, (d) research and development, (e) institutional and regulatory system, and (f) food security.

Data collection in Ghana was undertaken in November–December 2015 and April–May 2016. Data collection in Burkina Faso was undertaken in February–March 2016. All interviews were conducted face-to-face at locations selected by each respondent. All interviews were audio-recorded after receiving consent from each participant. In total 33 participants were interviewed in Ghana and 13 in Burkina Faso (Table ). Due to the lack of cotton farmers’ associations in Ghana, we conducted interviews with 10 individual cotton farmers in four active cotton-growing communities (Bullu, Zini, Chum, and Gwollu), all located in the Sissala West district of the Upper West region.

Secondary data was collected from official government policy and regulatory documents, and reports produced by agencies and organizations involved with the cotton sector. Annual national cotton production and performance data for both countries was obtained from the database of the Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics Division (FAOSTAT), and validated with data from the International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) (see Section 2.1).

3.4. Data analysis

Each interview was transcribed verbatim for further analysis following an inductive content analysis approach. The thematic analysis of interview transcripts allowed for the elicitation of the opinions and viewpoints of the various interviewed stakeholders. We elicited stakeholder perceptions for each of the six domains outlined in Section 3.3, using appropriate code words. To classify and analyse the transcripts of each interview we used the NVIVO qualitative data analysis computer software (version 11), developed by QSR International.

4. Results

4.1. Perceived outcomes on input credit systems

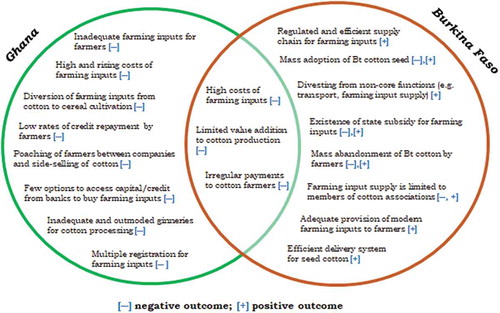

The input credit system is an important element of cotton value chains (Section 2.1). Its efficiency can be measured through the availability, quality, and quantity of inputs, and is integral to the expansion and sustainability of the cotton sector. Figure provides a summary of the outcomes that reforms had on the input credit system, as perceived by the respondents from Ghana and Burkina Faso (see also Table S1 in Supplementary Electronic Material for some direct quotes).

Overall, perceptions across the two countries varied considerably. Ghanaian stakeholders mentioned several issues that in their opinion have negatively affected input credit systems and as an extent the performance of the sector such as (a) inadequate inputs for farmers, (b) limited capital to buy inputs, and (c) expensive and rising costs of production inputs (Figure ). In contrast, Burkina Faso stakeholders discussed a mix of positive and negative. Some of the direct and indirect outcomes of the reform programs since the mid-1990s include the (a) well regulated and efficient inputs supply chain, (b) commercialization of Bt cotton (Bollgard II®), (c) existence of state subsidy, and (e) high costs of Bt cotton, among others (Figure ). The high costs of inputs and the limited value addition to cotton on the local market are the two main negative outcomes of cotton sector reforms that have been common to both countries (Figure ).

4.2. Perceived outcomes on price determination and profit distribution

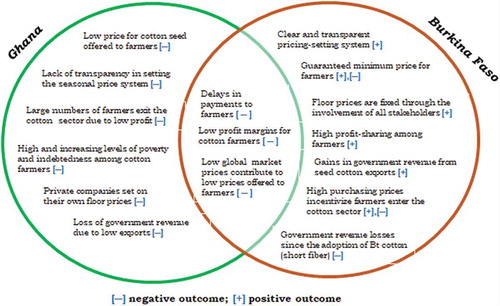

As discussed in Sections 1–2, cotton production provides a critical source of income and revenue for citizens and governments in SSA. Ensuring a fair, balanced, and stable pricing system in the cotton production system is a key element to sustain the sector and enable it to contribute to poverty eradication (Section 2). Figure summarizes stakeholder responses regarding the outcomes of reforms on price determination and profit distribution in the cotton sector of the two countries (see also Table S2 in Supplementary Electronic Material for some direct quotes).

Figure 5. Stakeholder perceptions of reform outcomes on price determination and profit distribution.

Stakeholders in Ghana brought up mainly negative outcomes of reforms related to the low price for cottonseed, lack of transparency in the seasonal price-setting system, and the decline in government revenue due to low export (Figure ). Stakeholders in Burkina Faso emphasized reform outcomes such as a guaranteed minimum price for farmers, high profit sharing among farmers, and favorable price incentives for farmers (Figure ). Delays in paying farmers and the negative effect of the low world market were common negative reform outcomes discussed across in both countries (Figure ).

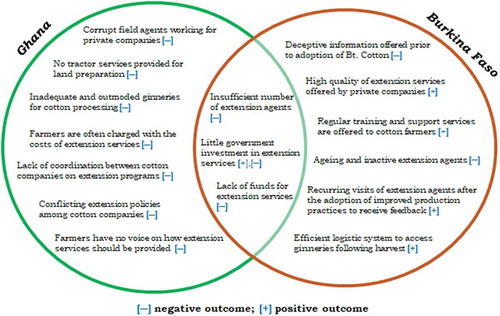

4.3. Perceived outcomes on extension services

Figure summarizes stakeholder perceptions about the outcomes of reforms on extension services in the cotton sector (see also Table S3 in Supplementary Electronic Material for some direct quotes). Ghana stakeholders perceived mostly negative outcomes from the implementation of reforms such as the corrupt field agents of private companies, the conflicting extension policies of cotton companies, and lack of farmer voice in extension services (Figure ). In Burkina Faso, on the other hand, stakeholders perceived more positive than negative outcomes. Among the main outcomes cited were the development of better-quality extension services, regular training and support services, a good transport/logistic system, and on the negative side aging extension agents (Figure ). The limited government investment in extension services was one of the common elements discussed by stakeholders in both countries (Figure ).

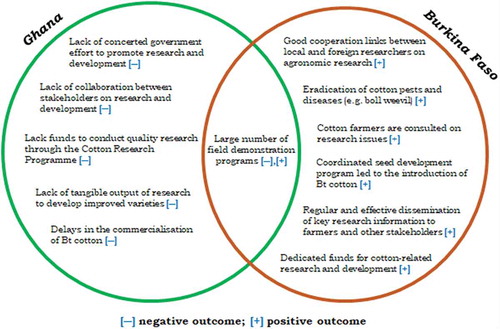

4.4. Perceived outcomes on research and development

Our survey of stakeholders in Ghana and Burkina Faso found variations at the country level about the outcomes of reforms on research and development (Figure ) (see also Table S4 in Supplementary Electronic Material for some direct quotes). Respondents in Ghana mentioned issues such as a lack of concerted government effort in research and development, delay in commercialization of Bt cotton, and lack of funds for the cotton research program as key outcomes of the reforms (Figure ). In Burkina Faso, stakeholders emphasized how the improvement of research programs in the broader agriculture sector has trickled down to the cotton sector (Figure ). Cooperation between local and foreign research institutes on agronomic issues, eradication of pests and diseases (e.g. boll weevil), consultation with producers on research issues, and dedicated funds for research and development were all mentioned as positive outcomes of reforms in for research and development in Burkina Faso’s cotton sector (Figure ).

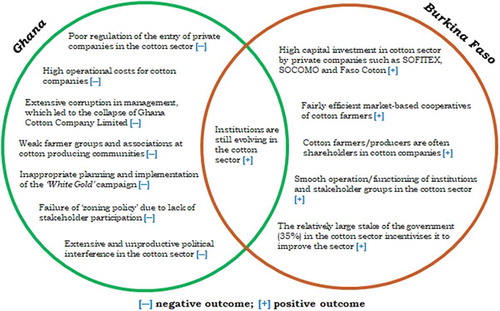

4.5. Perceived outcomes on institutional and regulatory systems

Improving the productivity and overall performance of the cotton sector requires a coordinated, participatory, integrated, and collaborative regulatory system across the value chain. Figure summarizes the main issues raised by stakeholders in Ghana and Burkina Faso with regard to the outcomes of reforms on institutional and regulatory systems (see also Table S5 in Supplementary Electronic Material for some direct quotes). According to respondents in Ghana, reform programs contributed to the weakening and collapse of the existing institutional framework for cotton sector management (Figure ). The lack of cooperative groups, corruption at the management level, politicization of entry licensing for private companies, and failure of zoning policy were among the negative highlighted outcomes of reforms (Figure ). On the other hand, in Burkina Faso, interviewees discussed mainly positive outcomes of reforms such as the high level of capital investment, the development of efficient market-based cooperatives and a powerful cotton producer association, and the careful involvement of the central government in managing the sector (Figure ).

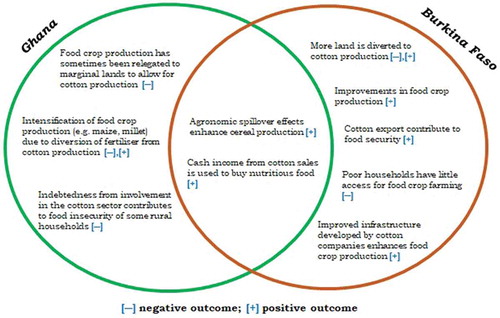

4.6. Perceived outcomes on food security

Figure summarizes stakeholder perceptions regarding the outcomes of cotton sector reforms on food security in the two countries (see also Table S6 in Supplementary Electronic Material for some direct quotes). Respondents in both countries brought up positive outcomes such as agronomic spillover that enhanced cereal production and the availability of extra income from cotton sales to buy food crops (Figure ). However, in Ghana, interviewees discussed some negative outcomes of the reforms such as the displacement of food crops to marginal lands, the intensification of food crop production (e.g. maize, millet), and yield reductions for food crops such as maize (Figure ). Respondents in Burkina Faso reported some positive outcomes such as using the inputs of cotton companies to improve cereal productivity (Figure ). Some respondents also emphasized that crop rotation practices allow cereals with superficial roots to benefit from the backward effects of the fertilizer used for cotton production, which results in greater food crop yields compared to non-cotton-producing areas.

5. Discussion

5.1. Synthesis of stakeholders perception of reform outcomes on national cotton sectors

Generally, our study suggests that the elicited stakeholder perceptions (Section 4) reflect quite well the actual performance of the cotton sector in Ghana and Burkina Faso following the implementation of reform programs (Sections 2.2–2.3). The multiple stakeholders consulted concretely discussed key linkages between reforms and performance, and shared both the main positive and negative outcomes on the six study domains (Sections 2.1, 3.3), based on their experience and knowledge.

In both Ghana and Burkina Faso, the liberalization of the cotton sector to pave way for private-sector investment was the first step toward halting the declining productivity and stagnating yields, and formed the key driver of structural and policy reforms (Goreux, Citation2004). Our results suggest that Ghanaian stakeholders perceived that the reform had largely negative outcomes across the six domains that were considered as proxies for the performance of the cotton sector (i.e. input credit systems, price and profit determination, extension services, research and development, institutional and regulatory systems, and food security). Interviewees in Burkina Faso, on the other hand, viewed the reforms as having had both positive and negative outcomes across these six domains and as an extent on the performance and sustainability of the sector (Vitale et al., Citation2011).

Dorward, Kydd, and Poulton (Citation2004) discussed the sustainability of input credit schemes for cotton sector productivity in SSA, which has been one of the prominent domains in our stakeholder interviews (Section 4.1). In Burkina Faso, before the reforms the factors of production were provided to farmers, initially free of charge and subsequently in the form of credit, under public monopolies (Kaminski, Headey, & Bernard, Citation2009b).

Our survey results in Ghana revealed that the input credit system in the cotton sector has been inefficient and collapsed rapidly since the sector’s liberalization, as has also been outlined in other studies (Asinyo et al., Citation2015; Howard et al., Citation2012). Many farmers left the cotton sector due to lack of access to sufficient agricultural inputs after liberalization in Ghana (Delpeuch & Vandeplas, Citation2013). Stakeholders in Ghana openly criticized the dysfunctional the credit system as a major reason for the declining performance of the sector. For example, interviews in the four cotton-producing communities in the Sissala West district found that farmers blamed cotton companies and extension workers for not providing them with adequate inputs. On the other hand, officials of the cotton companies accused the farmers of reducing both the planted cotton area and diverting inputs from cotton production to cereal production. However, there was a consistent perception between cotton company officials that farmers consider cotton as a secondary crop and not their main livelihood activity.

According to stakeholders in Burkina Faso, the reform programs have had both negative and positive outcomes for the input credit system (Figure ) (Table S1). Most of them agreed that although the central government reduced its participation in the provision of input services for the cotton sector since the 1990s, it still plays a key role in collaboration with the private sector. This seems to ensure a better access to agricultural inputs on credit and enable farmers to make repayments effectively. These stakeholder perceptions are consistent with insights reported in other studies across Francophone countries in West Africa (e.g. Baquedano et al., Citation2010; Kaminski, Citation2007). However, it should be mentioned that access to credit remains a key constraint for the adoption of cotton in the country (Porgo, Kuwornu, Zahonogo, Jatoe, & Egyir, Citation2018).

Considering that producer price-setting mechanisms were one of the key objectives of reform actions in the cotton sector (Section 2), it was anticipated that producers, especially farmers, would enjoy high cottonseed prices (Baffes, Citation2005, Citation2007; Goreux, Citation2004). Available information across SSA shows that producer prices are commonly determined at the beginning of the crop season based on an agreed-upon formula (Tschirley, Poulton, & Labaste, Citation2009).

Stakeholders in Ghana highlighted that the reforms had negative outcomes on the price-setting system. For example, all interviewed stakeholders acknowledged that price-fixing committees have failed at different times, partly because not all stakeholders are properly consulted, which results in high price competition (Figure ). Almost all interviewees across stakeholder groups asserted that even though a floor price is usually announced before the start of the farming season, it is not consistently observed as private companies offer different prices to farmers. The overall decline in the sector’s profitability in Ghana and the fact that the farmers suffer the most serious consequences was a common theme in most interviews. The majority of Ghanaian stakeholders emphasized the need for a functioning inter-professional body to coordinate seed cotton pricing in Ghana.

On the contrary, stakeholders in Burkina Faso appraised positively the reform outcomes on price setting and profit determination mechanisms. All stakeholders commented that the improved institutional and policy framework has enabled producers to enjoy a larger share of the profit from cotton production. Cotton farmers exert through the UNPCB strong influence on cotton pricing, which is determined at the beginning of the farming season (World Bank, Citation2004) (see also Table S2 in Supplementary Electronic Material). However, stakeholders in both countries discussed the delays in paying farmers and the negative effect of low world market prices on profits as challenges to be expected in the face of regular fluctuations in the global cotton market (see also Bassett, Citation2014).

Cotton is considered a very demanding crop in terms of labour and inputs when compared to other widely grown crops in SSA such as maize (Poulton et al., Citation2004). As a result, there is a need for regular and specialized advisory and extension services to ensure high productivity. Following the liberalization of the cotton sector, private companies would be expected to provide the needed extension and advisory services to farmers. However, our interviews in Ghana described a generally negative trend in the provision of such services from the private sector (Figure ) (see also Table S3 in Supplementary Electronic Material). According to most interviewees, although government-led agricultural extension activities were limited even before the implementation of reform programs, the extension services in the cotton sector deteriorated further after liberalization. The lack of coordination and the low capacity of private companies to offer effectively such services, have led to poor and contradictory extension to cotton farmers in Ghana (MOFA, Citation2013). Respondents from small-scale cotton companies and the Ministry of Food and Agriculture pointed that dishonest extension workers have engaged in malicious practices on their own or in conjunction with farmers. Such practices include the sale of cottonseeds (instead of giving it at no charge to the smallholder farmers), under-reporting of supply, and inaccurate weighing.

In contrast, respondents in Burkina Faso identified both positive and negative outcomes on extension services due to reforms. Most of the respondents viewed the reform of extension services as contributing to increasing production efficiency across the different cotton-growing regions. The successful commercial introduction of Bt cotton in 2008 was regularly cited as a positive outcome at the onset by interviewees. However the same stakeholders also highlighted their disappointment with the lack of adequate information on the actual impacts of Bt cotton prior to its full-scale introduction, which led the government to suspend the Bollgard II variety at the beginning of the 2016–2017 agricultural season (Sanou, Gheysen, Koulibaly, Roelofs, & Speelman, Citation2018) (see also Table S3 in Supplementary Electronic Material). The concern of the social, economic, and ecological impacts of adopting genetically modified cotton expressed by respondents has been in line with many other studies in different parts of the world (e.g. Arza, Goldberg, & Vazquez, Citation2013; Bennett, Morse, & Ismael, Citation2006; Fischer, Ekener-Petersen, Rydhmer, & Björnberg, Citation2015; Subramanian & Qaim, Citation2009).

The outcome of reforms on research and development within the cotton sector has varied widely in the two countries according to stakeholder perceptions (Figure ) (see Table S4 in Supplementary Electronic Material). All interviewed stakeholders in Ghana agreed that the performance of research and development activities within the national cotton sector has been unimpressive for several years. Interviewees from CSIR-SARI and MOFA highlighted that research and development in the sector has suffered, as the government has been the sole sponsor of research (but also unable to provide sufficient financial support), amidst the lack of meaningful contribution from cotton companies. The interviewed farmers were quick to blame the lack of research programs as the main reason for the delay in introducing improved cotton varieties.

Again, contrary to the situation in Ghana, stakeholder interviews in Burkina Faso pointed that research and development activities had improved significantly after the reforms (Figure ) (see also Table S4 in Supplementary Electronic Material). Most stakeholders highlighted the sustained government budget allocation for research, coupled with external financial assistance (e.g. from the French Agricultural Research Institute-CIRAD), as having played a key role in the introduction of new and improved varieties, and in dealing effectively with pests and diseases. Interviews with researchers from INERA, the main agricultural research agency in Burkina Faso, emphasized that the integrative nature of the sector offers opportunities to all stakeholders (e.g. cotton companies, farmers, government agencies, international researchers) to participate in decision-making, which has been critical in maintaining effective research and development programs in the country (see also Poulton & Tschirley, Citation2009).

There have been high levels of stakeholder dissatisfaction in Ghana regarding the outcomes of reforms on institutional and regulatory systems (Figure ) (see Table S5 in Supplementary Electronic Material), especially among individual farmers and private cotton companies. Most of these interviewees believed that the reforms had resulted in dysfunctional institutional structures, which contributed to the subsequent overall weakening of the sector. Stakeholders also raised multiple concerns about the politicization of the cotton sector by different governments, which caused an institutional vacuum for the sector. Multiple stakeholders cited the withdrawal of the government’s 30% stake in the industry following the collapse of the Ghana Cotton Company Limited (GCCL), and more recently, the “White Gold” campaign (see Section 2.2), as examples of the poor institutional and regulatory systems in the cotton sector. Another example of weak institutional and regulatory processes brought up by different stakeholders, was the zoning policy initiated by MOFA in conjunction with CDP 1, which had no legal support, and hence, could not be properly implemented (MOFA, Citation2013). Farmers expressed great concern about their lack of knowledge about the White Gold campaign, even though they are supposed to be the key stakeholders in the cotton sector (Section 2.2).

Stakeholder interviews in Burkina Faso disclosed that a functioning institutional and regulatory system has been one of the most significant outputs of the cotton reforms (Figure ) (see Table S5 in Supplementary Electronic Material). Interviewees indicated that reform had a positive outcome in both strengthening the association of cotton producers as well as the overall regulatory framework of the sector. Multiple stakeholders expressed that the careful and gradual implementation of reform programs had strengthened the involvement of cotton farmers in decision-making, as they are recognized to be the key stakeholders in the sector. Most interviewed stakeholders in Burkina Faso also indicated that the current regulatory framework facilitated an integrated decision-making structure, allowing the effective participation of all actors involved in the cotton sector. Some interviewees from UNPCB, however, mentioned that some failures in the current institutional and regulatory framework are to be blamed for the abandonment of Bt cotton, even after several years of field trials and its subsequent authorization of commercial production by the National Biosafety Agency (Dowd-Uribe, Citation2014).

Cotton is an industrial crop that can interact with food security in several ways (Fortucci, Citation2002; Solidaridad, Citation2016; Wiggins, Henley, & Keats, Citation2015). At the household level, cotton production can generate income that can be used to buy basic foodstuff and other goods, having a direct positive contribution to food access. On the other hand, cotton production can divert land within farms from food crop production to cotton production, possibly reducing the availability of food. Involvement in cotton production can increase access to agricultural inputs, allowing for the intensification of food crop production and having positive overall effects in food availability (e.g. Theriault & Tschirley, Citation2014). Understanding the combined effects of such multiple factors is important when assessing the local food security outcomes of industrial crop production, including cotton (Wiggins et al., Citation2015).

Stakeholder interviews in Ghana and Burkina Faso identified that the agronomic spillover from cotton production had positive local food security outcomes through enhancing and intensifying cereal production (Figure , Table S6 in Supplementary Electronic Material) (Theriault & Tschirley, Citation2014). At the same time, interviews suggest that the extra income from cotton sales could be used to buy staple crops, contributing significantly to sustaining food security in rural households (see Lam et al., Citation2017).

5.2. Linking stakeholder perceptions and national-level production data

In terms of its socioeconomic importance and poverty alleviation potential, cotton production remains a key agricultural activity and rural development strategy for several countries in SSA. This is despite the many challenges that the sector has faced in different parts of the continent across its value chain over the past half-century (Poulton & Tschirley, Citation2009). The analysis of national-level cotton productivity data for the study countries (Figure , , Figure S1-S3 in Supplementary Electronic Material) appear consistent with stakeholder perceptions on the performance of their cotton sector after the implementation of the reforms.

The national production data indicate that the performance of the cotton sector in Burkina Faso began to improve significantly after reforms were implemented, as highlighted by the continuous growth in area harvested, quantity produced, yield, and market share since the mid-1990s (Figures , , Figures S1–S3 in Supplementary Electronic Material). Other studies have also documented the improved performance of the Burkina Faso cotton sector after reforms were implemented (e.g. Bennett et al., Citation2006; Kaminski et al., Citation2009b; Vitale, Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2006). In Ghana, the cotton sector, apart from the two short-term booms of 1986 and 2011 (with annual growth rates of 306% and 185% respectively), the sector seems to have been on a terminal decline since its liberalization in 1985 (Asinyo et al., Citation2015) (see Figures , ; Figures S1–S3 in Supplementary Electronic Material).

In a nutshell, while Burkina Faso succeeded in achieving the fundamental goal of achieving a strong and robust cotton output through targeted reforms (as shown by the consistent growth since the reforms), the same thing cannot be said for Ghana. All of the six performance domains explored in this study (Section 4), appear to have been negatively affected after liberalization. In fact, the current state of that Ghanaian cotton sector can best be described as one of stagnation and vulnerability.

Our analysis suggest that the decline of Ghana’s cotton sector started at the onset of the reforms in 1985, and can be possibly explained as the combined effect of local (country-level) and external factors. Local-scale factors include the lack of a suitable policy environment, poor organization of the sector, lack of capital/investments, lack of professionalism among some stakeholders, and the absence of a dynamic cotton farmers’ association and/or cotton farmers’ cooperatives (MOFA, Citation2013). These have been complemented by agronomic constraints such as the inability to develop new improved cotton varieties, the availability of quality inputs, the prevalence of pests and diseases, poor soil quality, and the escalating effects of climate change (e.g. shortage of rainfall) in northern Ghana (Asinyo et al., Citation2015; Howard et al., 2012). Fluctuating global lint prices have further contributed to poor local market conditions, which have affected most SSA cotton-producing countries (Theriault, Serra, & Sterns, Citation2013), thereby making the sector unattractive for farmers in Ghana. Farmers interviewed in four cotton-growing communities indicated that pricing is the key driver of their participation in producing cotton in addition to staples like maize and yams, and that falling cotton prices are worsening their poverty and food insecurity conditions (see Table S2 in Supplementary Electronic Material).

On the other hand, Burkina Faso is considered as a success story of reforms in the cotton sector, considering the substantial productivity increases and the improvement of the overall performance of its cotton sector (Abbott, Citation2013; Delpeuch & Vandeplas, Citation2013; Kaminski et al., Citation2009b; Vitale, Citation2018; Vitale et al., Citation2011). All these studies highlight that the Burkina Faso cotton sector reform model is unique when compared to other experiences in SSA, in that it has generated strong returns for a large number of producers in the country. Kaminski, Headey, and Bernard (Citation2009a) underscored the gradual reform approach that was adopted by the Burkinabe government, with its strong focus on reinforcing its institutional and regulatory framework, thus ensuring effective market coordination along the cotton production value chain. Specifically, some of the factors that have been critical in improving the sector’s performance over the last two decades include the establishment of a national cotton union, the reallocation of responsibilities, and the involvement of cotton producers in decision-making (e.g., on shareholding and price-setting mechanisms) (Kaminski et al., Citation2009a; Sanou et al., Citation2018; Vitale, Citation2018).

5.3. Study limitations

The participants selected for this study were identified through an extensive institutional analysis, and subsequent snowballing during the initial interviews with key players in the sector. While the interviewed stakeholders were deemed as the most appropriate and qualified due to their deep knowledge of the sector (and participation in various capacities), the findings of the study must be interpreted with caution. First, the survey might not have captured the views of all relevant stakeholder groups due to practical challenges. For example, some identified respondents working for government agencies were not accessible for interviews during the data collection period. Moreover, despite our instructions at the beginning of the interviews, the views of the interviewed stakeholders might reflect their personal opinions and not necessarily the opinions of their organizations. Second, the stakeholder perception analysis method employed in this study relies entirely on the subjective examination of perceptions of reform outcomes. Thus, some of the results could be vulnerable to one-sided and biased responses on certain issues (e.g. issues related to the adoption of GMOs).

6. Conclusion and practical implications

The present study highlights the outcomes of reform actions in the cotton sector of Ghana and Burkina Faso drawing on stakeholders’ perceptions and national cotton production data. Our results, consistent with previous studies, and suggest that the cotton reforms in Ghana and Burkina Faso, although starting from similar points, took different directions, and subsequently, generated sharply different outcomes. Reforms appear to have significantly improved the performance of the cotton sector in Burkina Faso, whilst the situation in Ghana has been radically different. Stakeholder interviews in Ghana and Burkina Faso identified that the reforms had a mix of positive and negative outcomes on each of the six domains examined in this study, as summarized below:

Input-credit system: Stakeholders in Ghana asserted the inefficiency and near collapse of the system after the sector’s liberalization, which prompted many farmers to exit cotton production. In Burkina Faso, stakeholders perceived that farmers gained improved access to inputs and flexible repayment schemes even after the role of the central government in the sector became minimal following the reforms in the 1990s.

Pricing determination and profit distribution: Stakeholders from Ghana opined that the price-fixing mechanism failed woefully, as the prices negotiations were not inclusive, resulting in high price competition and low prices paid to farmers. Respondents from Burkina Faso, on the other hand, indicated that a direct outcome of the reforms was an inclusive, well-functioning and trusted price-setting system, which was a key reason in improving the performance of the sector.

Extension services: Interviewees from Ghana perceived that extension and advisory services have deteriorated further after the liberalization of the sector, due to poor coordination between the main relevant actors (i.e. government, companies, farmers), and the low capacity of private enterprises to provide effectively such services. In Burkina Faso, stakeholders expressed that the quality of extension services was not affected from reforms, contributing positively to increase production efficiency across the different cotton-growing regions. Ageing extension agents, however, were considered a major challenge presently facing the sector in the country.

Research and development: According to Ghanaian stakeholders, cotton-related research and development has been a low priority from both the public and private sector (including cotton companies). The lack of investment in research and development has been a major contributor to the failure to introduce new (and diversify current) cotton varieties. Stakeholders in Burkina Faso highlighted that a sustained government budget allocation for research, coupled with external financial and technical assistance, has played a major role in the introduction of high yielding, pest- and disease-resistant cotton varieties (including Bt cotton varieties such as Bolgard II).

Institutional and regulatory systems: Interviewees from Ghana perceived that the terminal decline of the national cotton sector has been partly due to the weak regulatory framework and frequent partisan politicization during the implementation of the reform measures. In Burkina Faso, respondents appeared more satisfied with the institutional and regulatory systems from the reform process, although inherent challenges were highlighted.

Food security: In both countries, stakeholders highlighted both the positive and the negative implications of reforms on food security. For instance, positive spillover from cotton production was mentioned as an example of the positive food security outcomes of reform actions. On the other hand, the shift of local farmers from food crops to cotton was identified as a possible risk, due to land and labour diversion from food crop production.

Considering the very different outcomes of reforms in Ghana and Burkina Faso, there are some lessons that can be learned in order to revitalize, improve and sustain the overall performance of the sector. Overall cotton production and productivity increased in Burkina Faso following the reforms, whereas the sector witnessed a terminal decline in Ghana. However, the reforms of the cotton sector in Burkina Faso cannot be considered as a complete success, as for example, several challenges were highlighted including institutional and marketing bottlenecks, and inadequate extension services. Still, the government of Ghana could learn from the experiences of Burkina Faso’s approach to reforms, in its attempt at revitalizing the Ghanaian cotton sector.

Competing interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

Ethical Standards

Informed consent was obtained from all stakeholder organizations and individual participants included in this study.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (290.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank various stakeholders and individuals involved in the cotton sector in Ghana and Burkina Faso who provided valuable advice and information during this study.

Supplementary material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed here https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1477541

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yaw Agyeman Boafo

This study was conducted as part of the research project “Food Security Impacts of Industrial Crop Expansion in Sub-Saharan Africa (FICESSA)”. FICESSA is a 3-year interdisciplinary project, funded by the Belmont Forum that aims to provide clear empirical evidence of how industrial crops such as sugarcane, jatropha, cotton, tobaccocompete for land with food crops in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the mechanisms through which this competition affect food security, whether in a positive or a negative way. FICESSA undertakes studies at multiple spatial scales using various analytical tools to study past dynamics and explore future scenarios.

References

- Abbott, P. (2013). Cocoa and cotton commodity chains in West Africa: Policy and institutional roles for smallholder market participation. In: Rebuilding West Africa’s Food Potential, A. Elbehri (ed.), FAO/IFAD. Retrieved April 24, 2018, from http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3222e/i3222e08.pdf

- AGRA. (2017). Africa agriculture status report: The business of smallholder agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa (Issue 5). Nairobi, Kenya: Author. Issue 1, No. 5.

- Akiyama, T., Baffes, J., Larson, D., & Varangis, P. (2003). Commodity market reform in Africa: Some recent experience. Economic Systems, 27(1), 83–115. doi:10.1016/S0939-3625(03)00018-9

- Arza, V., Goldberg, V., & Vazquez, C. (2013). Argentina: Dissemination of genetically modified cotton and its impact on the profitability of small-scale farmers in the Chaco province. CEPAL Review, 107, 127–143.

- Asinyo, B., Frimpong, C., & Amankwah, E. (2015). The state of cotton production in Northern Ghana. International Journal of Fiber and Textile Research, 5(4), 58–63.

- Baffes, J. (2005). The cotton problem. The World Bank Research Observer, 20(1), 109–144. doi:10.1093/wbro/lki004

- Baffes, J. (2007). Distortions to cotton sector incentives in West and Central Africa. Presented at the CSAE Conference Economic Development in Africa, March 19–20, Oxford, UK.

- Baquedano, F. G., Sanders, J. H., & Vitale, J. (2010). Increasing incomes of Malian cotton farmers: Is elimination of US subsidies the only solution? Agricultural System, 103, 418–432. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2010.03.013

- Bassett, T. (2001). The peasant cotton revolution in West Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, 1880–1995. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bassett, T. J. (2014). Capturing the margins: World market prices and cotton farmer incomes in West Africa. World Development, 59, 408–421. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.032

- Bennett, R., Morse, S., & Ismael, Y. (2006). The economic impact of genetically modified cotton on South African smallholders: Yield, profit and health effects. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(4), 662–677. doi:10.1080/00220380600682215

- Berg, E. (1981). Accelerated development in Sub-Saharan Africa: An agenda for action. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Boughton, D., Tschirley, D., Zulu, B., Ofico, A., & Marrule, H. (2003). Cotton sector policies and performance in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons behind the numbers in Mozambique and Zambia. Paper presented at the IAEA Annual Meeting, Durban, South Africa.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd.

- de Graaff, J., Kessler, A., & Nibbering, J. W. (2011). Agriculture and food security in selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa: Diversity in trends and opportunities. Food Security, 3(2), 195–213. doi:10.1007/s12571-011-0125-4

- Delpeuch, C., & Leblois, A. (2014). The elusive quest for supply response to cash-crop market reforms in Sub-Saharan Africa: The case of cotton. World Development, 64, 521–537. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.007

- Delpeuch, C., & Vandeplas, A. (2013). Revisiting the cotton problem—A comparative analysis of cotton reforms in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 42(C), 209–221. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.06.020

- Dorward, A., Kydd, J., & Poulton, C. (2004). Market and coordination failures in poor rural economies: Policy implications for agricultural and rural development. In AAAE Conference Shaping the Future of African Agriculture for Development: The Role of Social Scientists, Nairobi, Kenya, 6–8 December.

- Dowd-Uribe, B. (2014). Engineering yields and inequality? How institutions and agro-ecology shape Bt. Cotton outcomes in Burkina Faso. Geoforum, 53, 161–171. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.02.010

- FAO. (2014). State of food and agriculture in the African region and CAADP implementation with specific focus on smallholder farmers and family farming. Paper delivered at the FAO regional conference for Africa, Tunis, Tunisia, March 24–28, 2014.

- FAOSTAT. (2016). Food and agriculture organization statistical database. United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome. Retrieved December, 2016 http://faostat.fao.org/

- Fischer, K., Ekener-Petersen, E., Rydhmer, L., & Björnberg, K. (2015). Social impacts of GM crops in agriculture: A systematic literature review. Sustainability;, 7, 8598–8620. doi:10.3390/su7078598

- Fortucci, P. (2002). The contributions of cotton to economy and food security in developing countries, Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Rome, Italy.

- Fosu, K. Y., Heerink, N., Ilboudo, K. E., Kuiper, M., & Kuyvenhoven, A. (1997). Agricultural supply response and structural adjustment in Ghana and Burkina Faso — Estimates from macro-level time-series data. In W. K. Asenso-Okyere, G. Benneh, & W. Tims (Eds.), Sustainable food security in West Africa. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Goreux, L. (2004). Reforming the cotton sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa region working paper 47. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Goreux, L.M., & Macrae, J. (2003). Reforming the cotton sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Region Working Paper Series No. 47, The World Bank.

- Howard, E. K., Osei-Ntiri, K., & Osei-Poku, P. (2012). The non-performance of ghana cotton industry: eco-friendly cotton production technologies for sustainable development. International Journal Of Fiber and Textile Research, 2(4), 30–38.

- Hussein, K. (2008). Cotton in West and Central Africa: Role in the regional economy & livelihoods and potential to add value. In Common Fund for Commodities (ed.), Proceedings of the Symposium on Natural Fibres, FAO, Rome.

- ICAC. (2008). Ghana country report: State of cotton industry and prospects for the future in Ghana, 1–6. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from https://www.icac.org/meetings/plenary/67_ouagadougou/documents/country_reports/e_ghana1.pdf%5Cn

- ICAC. (2016). Cotton: World statistics: 2015/2016 Supply and use of cotton. Retrieved August 15, 2017, from https://www.icac.org/cotton_info/publications/miscellaneous/statistics_contents.pdf

- IMF. (2003). Mali: Enhanced Initiative for Highly Indebted Poor Countries, Completion Point Document, IMF country report 03/61. Washington DC: Author.

- Kaminski, J. (2007). Interlinked agreements and the institutional reform in the cotton sector of Burkina Faso. Working paper, Atelier de Recherche Quantitative Appliquée au Développement Économique. Toulouse, France: Toulouse School of Economics.

- Kaminski, J. (2009). Cotton dependence in Burkina Faso: constraints and opportunities for balanced growth. Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent, 107–124.

- Kaminski, J., & Bambio, Y. (2009). The cotton puzzle in Burkina Faso: Local realities versus official statements. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association, New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Kaminski, J., Headey, D., & Bernard, T. (2009a). Institutional reforms in the burkinabe cotton sector and its impacts on incomes and food security: 1996–2006. Discussion Paper (IFPRI, Washington, DC).

- Kaminski, J., Headey, D., & Bernard, T. (2009b). Navigating through Reforms: Cotton in Burkina Faso. In D.J. Spielman & R. Pandya-Lorch (Eds.), Millions Fed: Proven successes in agricultural development. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Kaminski, J., Headey, D., & Bernard, T. (2011). The Burkinabe cotton story 1992–2007: Sustainable success or Sub-Saharan mirage? World Development, 39(8), 1460–1475. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.12.003

- Kriger, C. E. (2006). Cloth in West African history. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Lam, R. D., Boafo, Y. A., Degefa, S., Gasparatos, A., & Saito, O. (2017). Assessing the food security outcomes of industrial crop expansion in smallholder settings : Insights from cotton production in Northern Ghana and sugarcane production in Central Ethiopia. Sustainability Science, 12(5), 677–693. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0449-x

- Lele, U., Van derWalle, N., & Gbetibouo, M. (1990). Cotton in Africa: An Analysis of Differences in Performance. Managing Agricultural Development in Africa, MADIA-report. Washington: The World Bank.

- MOFA. (2013). Study to prepare statutory texts for Ghanaian institutions for the management and regulation of the cotton sector. Final report by Ministry of Trade and Industry and Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Accra: Government of Ghana.

- Moseley, W. G., Carney, J., & Becker, L. (2010). Neoliberal policy, rural livelihoods, and urban food security in West Africa: A comparative study of the Gambia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Mali. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(13), 5774–5779. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905717107

- Overton, J., & Van Diermen, P. (2003). Using quantitative techniques. In R. Scheyvens & D. Storey (Eds.), Development fieldwork: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Oxfam. (2007). Pricing farmers out of cotton, Oxfam Briefing paper, March 2007. Oxford, UK.

- Peltzer, R., & Röttger, D. (2013). Cotton Sector Organisation Models and their Impact on Farmer’s Productivity and income (Discussion Paper 4/2013). Bonn: German Development Institute.

- Porgo, M., Kuwornu, J. K. M., Zahonogo, P., Jatoe, J. B. D., & Egyir, I. S. (2018). Credit constraints and cropland allocation decisions in rural Burkina Faso. Land Use Policy, 70, 666–674. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.053

- Poulton, C, Gibbon, P, Hanyani-Mlambo, B, Kydd, J, Maro, W, Larsen, M. N, & Zulu, B. (2004). Competition and coordination in liberalized african cotton market systems. World Development, 32(3), 519–536. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.10.003

- Poulton, C., & Maro, W. (2009). Comparative analysis of organization and performance of african cotton sectors: The cotton sector of Tanzania. World Bank Africa Region Working Paper Series 127, PRSP: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper, Document Prepared and Adopted by the Government of Mali, Bamako, May 29.

- Poulton, C., & Tschirley, D. (2009). A typology of african cotton sectors. In D. Tschirley, C. Poulton, & P. Labaste (Eds.), Organization and performance of cotton sectors in Africa: Learning from reform experience (pp. 45–61). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ripoche, A., Crétenet, M., Corbeels, M., Affholder, F., Naudin, K., Sissoko, F., & Tittonell, P. (2015). Cotton as an entry point for soil fertility maintenance and food crop productivity in Savannah agroecosystems-evidence from a long-term experiment in Southern Mali. Field Crops Research, 177, 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2015.02.013

- Sanou, E. I. R., Gheysen, G., Koulibaly, B., Roelofs, C., & Speelman, S. (2018). Farmers’ knowledge and opinions towards bollgard II®implementation in cotton production in Western Burkina Faso. New Biotechnology, 42, 33–41. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2018.01.005

- Solidaridad. (2016). Cotton and food security. Solidaridad Network. Retrieved April 15, 2018, from https://www.solidaridadnetwork.org/sites/solidaridadnetwork.org/files/publications/A5_brochure_Cotton%20and%20Food_20P_0612.pdf

- Songsore, J. (2011). Regional development in Ghana: The theory and reality. Accra: Woeli Publishing Services.

- SP-CPSA (Secrétariat Permanent de la Coordination des Politiques Sectorielles Agricole). (2004). Document de Stratégies de Développement Rural a l’Horizon 2015. Ouagadougou: Burkina Faso. SP-CPSA.

- Subramanian, A., & Qaim, M. (2009). Village-wide effects of agricultural biotechnology: The case of Bt Cotton in India. World Development, 37(1), 256–267. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.03.010

- Teft, J. (2004). Building on successes in african agriculture: Mali’s white revolution: Smallholder cotton from 1960 to 2003. Focus 12, 2. Washington DC.

- Theriault, V., & Serra, R. (2014). Institutional environment and technical efficiency: A stochastic frontier analysis of cotton producers in West Africa. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 65(2), 383–405. doi:10.1111/jage.2014.65.issue-2

- Theriault, V., Serra, R., & Sterns, J. A. (2013). Prices and Institutions in the Malian cotton sector: Determinants of supply. Agricultural Economics, 44(2), 161–174. doi:10.1111/agec.12001

- Theriault, V., & Tschirley, D. L. (2014). How institutions mediate the impact of cash cropping on food crop intensification: An application to cotton in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 64, 298–310. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.014

- Tschirley, D., Poulton, C., Gergely, N., Labaste, P., Baffes, J., Boughton, D., & Estur, G. (2010). Institutional diversity and performance in african cotton sectors. Development Policy Review, 28(2010), 295–323. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00485.x

- Tschirley, D., Poulton, C., & Labaste, P. (2009). Organization and performance of cotton sectors in Africa learning from reform experience. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- USDA. (2016). Cotton and product annual: 2016 west africa cotton and products update. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved April 16, 2017, from https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Cotton%20and%20Products%20Annual_Dakar_Senegal_4-6-2016.pdf

- Vitale, J. (2018). Economic importance of cotton in Burkina Faso. Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome, Italy. Retrieved April 20, 2018, fromhttp://www.fao.org/3/i8330en/I8330EN.pdf

- Vitale, J., Ouattarra, M., & Vognan, G. (2011). Enhancing sustainability of cotton production systems in West Africa: A summary of empirical evidence from Burkina Faso. Sustainability, 3(12), 1136–1169. doi:10.3390/su3081136

- Wiggins, S., Henley, G., & Keats, S. (2015) Competitive or complementary? Industrial crops and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Research reports and studies. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

- World Bank. (2004, May). Cotton cultivation in Burkina Faso a 30 year success story. Presented at a Global Exchange for Scaling Up Success Scaling Up Poverty Reduction: A Global Learning Process and Conference, Shanghai, China.

- World Bank. (2006). Strategies for cotton in West and Central Africa: Enhancing competitiveness in the Cotton-4 - Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Mali. Washington, DC: Author.

- World Food Programme. (2009). Ghana Comprehensive Food and Security and Vulnerability Analysis (CFSVA). World Food Programme, VAM Food Security Analysis. Retrieved December 9, 2015, from http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp201820.pdf