Abstract

Mungbean (Vigna radiata (L). Wilczek) is a hardy early-maturing legume that can be used as a catch crop in the wheat and rice systems of South and Central Asia. To facilitate increased production, this study surveyed 345 mungbean growers and 336 non-growers in areas of Pakistan and Uzbekistan where there is potential for expansion. Low seed quality, low farmer awareness of the effect of mungbean on soil fertility, and high labor costs are identified as common constraints. In Pakistan, pests and diseases are a major constraint while low market demand is particularly a problem for farmers in Uzbekistan. Farm households were found to have little knowledge of the health benefits from mungbean consumption. It is therefore a priority to give farmers access to quality seed of improved varieties and to combine this with value chain development in Uzbekistan while promoting the benefits of mungbean to soil quality, incomes and human nutrition.

Public Interest Statement

Mungbean is a short-maturity summer pulse that fits well in existing cropping systems in Pakistan and Uzbekistan. It has much potential to improve human nutrition and agricultural sustainability in both countries. However, the expansion of mungbean is constrained by several factors. This study shows that only a minority of farmers were aware that the cultivation of mungbean can improve soil fertility and increase the yield of the subsequent crop. Unavailability of good seed, damage from crop pests and diseases, uncertain weather conditions and shortage of labor are the main reasons for low productivity. Addressing these issues can unleash the potential of mungbean to contribute to human nutrition and agricultural sustainability.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Pulses are an important food crop worldwide, especially in South Asia where they are a major source of vegetable proteins and micronutrients including iron for poorer sections of the population (Nair et al., Citation2013). In South Asia (Bangladesh, India and Pakistan), the demand for pulses is increasing, but since the early 1960s crop area and production have not increased (FAO, Citation2016a). The success of high yielding rice and wheat varieties from the green revolution has been associated with a displacement of micronutrient-dense crops such as pulses, both in the agricultural systems and in people’s diets (Byerlee & White, Citation2000; Welch & Graham, Citation1999). However, the lack of growth in pulses production in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan has created economic opportunities for other countries such as Myanmar and the Central Asian countries to increase their production and export.

Nowadays, the growing of pulses in wheat and rice systems is widely recognized to help sustain the productivity of these staple grain systems (FAO, Citation2016b; Peoples et al., Citation2009). It is also in line with agricultural sector policies in South Asia, which emphasize crop diversification away from staple grain monoculture (Byerlee & White, Citation2000; Joshi, Gulati, Pratap, & Tewari, Citation2004; Rahman, Citation2009). Furthermore, it contributes to meeting South Asia’s contemporary nutritional challenges by providing an affordable source of micronutrients including iron (Nair et al., Citation2013; Pingali & Rosegrant, Citation1995; Welch & Graham, Citation1999).

Mungbean (Vigna radiata (L). Wilczek) is a pulse crop that is particularly attractive for farmers in South Asia because of its short duration and decent performance under adverse climatic conditions such as heat, drought and salinity (HanumanthaRao, Nair, & Nayyar, Citation2016). There is evidence that modern, early maturing mungbean varieties, which can be harvested in about 60 days after sowing, and with resistance to Cercospora leaf spot, powdery mildew and Mungbean yellow mosaic virus have been widely adopted in South Asia (Shanmugasundaram, Keatinge, & d’Arros Hughes, Citation2009) and have benefitted farm households in terms of income and nutrition (Ali et al. Citation1997; Weinberger, Citation2005). The short maturity of mungbean allows it to be used as a catch crop—a fast maturing crop that is grown between successive planting of a main crop (e.g. Joshi et al., Citation2014 for Nepal).

This study focuses on Pakistan and Uzbekistan as two countries with contrasting agricultural systems but both having much unexploited potential to expand mungbean production. In Pakistan, mungbean is grown on an estimated 127,500 ha (Government of Pakistan, Citation2015). Production is concentrated in southern Punjab with other major growing areas in Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh (Haqqani, Zahid, & Malik, Citation2000). In Uzbekistan, mungbean was produced on an estimated 18,000 ha in 2015 and is concentrated in the Fergana valley where it is grown after winter wheat harvesting and before cotton sowing. Two recent studies provide evidence that winter wheat–mungbean rotations are also feasible in the dry and relatively saline Aral Sea basin (Bobojonov et al., Citation2012; Bourgault et al., Citation2013). Thus, there is a potential to expand mungbean production in Uzbekistan without disrupting existing land use patterns, which is important as farmers have to fulfill state orders for cotton and wheat.

The objective of this study was to identify possible farm-level constraints to mungbean production in Pakistan and Uzbekistan to accelerate mungbean expansion. This was achieved through comparison of farmers’ knowledge, perceptions and practices between current mungbean growers and non-growers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Conceptual approach

This study applies concepts of knowledge, attitudes (or perceptions) and practices (KAP). A KAP assessment collects information on what people know, believe and do in relation to a particular topic—in this case mungbean production and consumption. The method originates from the field of social psychology and has been widely employed in health science (e.g. World Health Organization, Citation2008). Nowadays, the method is also widely used in agricultural science (e.g. Adam, Sindi, & Badstue, Citation2015; Schreinemachers et al., Citation2015). It is a quantitative method that uses a structured questionnaire to collect this information. Knowledge here refers to farmers’ understanding of mungbean production and consumption. Perceptions refer to farmers’ beliefs about the challenges and opportunities to mungbean production while practices refer to farmers’ actual behavior (decisions, actions) that demonstrates their knowledge and perceptions. To identify possible farm-level constraints as well as opportunities to mungbean expansion, we split our sample of farm households into households that did and did not grow mungbean in the past 12 months, henceforth denoted as growers and non-growers.

2.1.1. Knowledge

Farmers’ knowledge of the benefits of producing mungbean was recorded through an open-ended question with answers later categorized into income, food, fodder, soil fertility, yield of subsequent crop, other benefits or “don’t know.” The person in charge of meal preparation was asked to describe possible health benefits of eating mungbean.

2.1.2. Perceptions

Farm managers were asked about the perceived challenges or constraints to producing mungbean. This was an open-ended question that was coded into 21 possible answers. Growers were asked to identify the main pests and diseases that affected their mungbean production. This was recorded by giving the respondent a stack of colored photographs showing causal agents or damage symptoms of 23 common mungbean pests and diseases.

2.1.3. Practices

For growers and non-growers, we recorded cropping patterns for the past 12 months. For growers, we also recorded detailed information about production practices in mungbean, such as the source of seed, sowing method, weeding, and harvesting, pest management practices, labor use and other inputs, and outlets for selling the produce. We estimated crop yields, revenues and input costs. For growers and non-growers, we asked the person in charge of the household’s food preparation to list the different foods that the household consumed during the past 7 days to indicate whether children 1–15 years old and women 15–44 years old consumed it and to estimate the total quantity consumed.

2.2. Data

We sampled 681 farm households, 321 in Pakistan and 360 in Uzbekistan, from areas with potential for mungbean expansion as informed by local mungbean experts. In Pakistan, study areas included Sindh province (128 households) and the Pothwar region of Punjab province (131 households). In the past, mungbean and other pulses such as lentils were important in Pothwar region, but farmers stopped their cultivation because of problems with poor seed quality and pests and diseases. We also took a small sample of 62 mungbean growers from the traditional mungbean growing area in southern Punjab. In Uzbekistan, we took a sample of 200 farm households in Fergana valley (Andijan and Fergana regions) and a sample of 100 farm households in Tashkent region. We also selected 60 households from Karakalpakstan in the country’s west as there is potential to expand mungbean there, although agro-climatic conditions are harsher with drought and high salinity. In each location, the samples were equally divided between growers and non-growers.

From each region, two to three districts were selected where mungbean production was important. In Pakistan, this was based on secondary data and information provided by extension and research organizations. In Uzbekistan, information was derived from district-level offices of the Ministry of Agriculture and water user associations. From each district, villages (in Pakistan) or rural citizen councils (in Uzbekistan) were selected where mungbean was grown. Based on agro-ecology, market access and rainfall patterns, similar villages were selected where mungbean was not grown. The study included 46 villages in Pakistan and 30 rural citizen councils in Uzbekistan. From each village up to 10 mungbean growers or non-growers were selected. If there were more than 10 households growing mungbean, then we first created a list and randomly selected 10 households. In Pakistan, only smallholder farm households, defined as under 5 ha in size, were included.

The researchers approached the households and explained the purpose of the study. Households were informed that participation is voluntary and that all information would be kept confidential. Household heads were asked for their oral consent to be interviewed. The primary respondent was the person responsible for agricultural production and was usually a man. The secondary respondent was the person responsible for food preparation and was usually a woman.

Data were analyzed by calculating means for mungbean growers and non-growers. Significant differences in means were tested using an unpaired t-test for continuous variables and percentages and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Monetary values were converted to US dollars using the official 2015 exchange rate for Pakistan (The World Bank, Citation2016) and the market (unofficial) exchange rate for Uzbekistan.Footnote1 Land areas were converted to hectares.

3. Results and discussion

The average household sampled in Pakistan had nine persons and many households (45%) were joint family households, which may consist of parents, sons and daughters and their spouses and offspring (Table ). The average farm size in Pakistan was 3.5 ha, half of which was irrigated. Apart from winter wheat, which was cultivated by every household in the sample, farmers grew a diverse range of cash and subsistence crops throughout the year. Households that grow and that do not grow mungbean had similar characteristics in Pakistan.

Table 1. Sample farm household characteristics for Pakistan and Uzbekistan, in proportion of respondents, unless indicated otherwise, 2016

With an average size of 31 ha, the sample farms in Uzbekistan were much larger than in Pakistan. Farm households had six persons on average and all were nuclear type of households. All land was irrigated and farms were specialized in a small set of crops that always included wheat and frequently included cotton, potatoes and vegetables. Farms growing mungbean were on average much larger than farms not growing mungbean. This is because larger farmers were specialized in cotton and wheat, and mungbean tends to fit in a rotation of cotton and winter wheat. Smaller farmers, with a size of often less than 10 ha, were more often specialized in vegetables.

3.1. Production practices

In Uzbekistan, farmers used a 2-year rotation cycle of winter wheat—catch crop—cotton. Winter wheat is sown in October and harvested in May or June of the next year. Thereafter, farmers grow a short duration catch crop such as mungbean, potatoes, vegetables, melons or corn until autumn. The next year they sow cotton in April and harvest it from early September to early November. Mungbean growers in the sample harvested the crop from mid-September up to mid-October, on average 96 days after sowing. Early maturing varieties are important to avoid delays in the winter wheat sowing and to avoid frost damage to the mungbean crop. This pattern is roughly the same for the study sites in Fergana valley, Tashkent and Karakalpakstan.

In Pakistan, there were distinct regional differences in the period for growing mungbean. In southern Punjab, which is the crop’s traditional area, it was sown in early May (Bhakkar) to June (Layyah) and harvested in about 83 days in August. In Pothwar region, it was sown mostly in late June to early July and harvested from late September to early October and the average growing period was 93 days. Lastly, in Sindh it was sown from February to March and harvested in about 77 days in May. Some farmers in Sindh grew mungbean twice a year. Mungbean was grown as a catch crop replacing fallow in Sindh and does therefore not compete with other crops. However, in southern Punjab and Pothwar it is considered a full-season kharif (summer) crop and competes for farm resources with cotton, sugarcane and fodder crops in southern Punjab and with groundnut, fodder crops, sorghum and millet in Pothwar region of Punjab (Figure ). However, in Pothwar region, non-growers were found to fallow 64% of their land during the kharif following wheat-fallow rotation and the adoption of mungbean therefore does not need to reduce the area under other crops.

Figure 1. Land use during the kharif season in Pakistan’s Pothwar region among mungbean growers and non-growers.

In Pakistan, mungbean sowing is usually done by manually broadcasting of seed on a cleared field (Table ). In Pothwar region, about a quarter of the farmers sow it in a standing crop (groundnut, vegetables or fodder crops). Machine sowing in lines was common in southern Punjab where 61% of farmers practiced this. In terms of seed sources, about half of the farmers bought their seed from an open grain market while a quarter saved it from their previous harvest (Figure ). Only 2% bought seed from registered seed dealers or companies.

Table 2. Mungbean production practices in Pakistan and Uzbekistan, in proportion of respondents unless indicated otherwise, 2016

Figure 2. Mungbean seed sources as reported by growers in Pakistan, in percent of respondents, 2016.

Note: Pothwar region (n = 50), southern Punjab (n = 62) and Sindh province (n = 53).

Most Pakistani mungbean growers irrigated their crop twice, except in Pothwar region where all agriculture is rainfed. Mungbean harvesting was virtually all done by hand. Fields were harvested 1–6 times, as pods do not ripen simultaneously, with an average of 1.5 times harvesting per field. Threshing of the grains was done manually or by machine. In Uzbekistan, on the other hand, mungbean sowing, harvesting and threshing were mechanized to a large extent, though nearly half of the farmers harvested by scything plants by hand. Contrary to Pakistan, farmers in Uzbekistan harvested their field in one go.

In Pakistan, farmers collected the crop residues to feed it to farm animals or for selling. In Uzbekistan, farmers also collected the residues to feed their farm animals or used it as in-kind payment for hired farm labor. Therefore, in both countries crop residues, and the nutrients and organic matter contained therein, are rarely left in the field. Field experiments have shown that a rotation with legumes significantly enhances the yield of the subsequent crop (Ghosh et al., Citation2007; Namazov, Khalikov, & Khaitov, Citation2015; Peoples et al., Citation2009). However, such experiments often assume that crop residues are plowed into the field, while our study shows that all plant biomass, except plant roots, is removed from the field. The contribution of mungbean to soil quality enhancement may therefore not be as large as some previous studies have reported.

The average mungbean grower in the sample for Pakistan planted mungbean on 0.88 ha of land and obtained a crop yield of about 1.1 tons/ha (Table ). Crop yields were relatively low in Pothwar and high in southern Punjab. Most farmers (86%) sold some of their mungbean harvest, and the average farmer sold 45% of its harvested quantity. Mungbean can therefore be considered as a semi-subsistence crop in Pakistan. Farmers sold their beans to middlemen in their village or at the open grain market. The average selling price was 0.91 US dollar (USD) per kilogram and this generated cash revenues of about USD 393 per household.

Table 3. Mungbean area, yield and prices and selling practices in Pakistan and Uzbekistan, average per farm household, 2016

In Uzbekistan, the average planted area under mungbean was 3.9 ha and therefore much larger than in Pakistan. At 1.9 tons/ha, average yields were also substantially higher than in Pakistan. Of the harvested quantity, 94% was sold to middlemen or at the open grain market. This shows that mungbean is a cash crop for farmers in Uzbekistan. The crop generated USD 4,320 in revenues per household on average.

Data on the cost of inputs were collected for Pakistan, but not for Uzbekistan (Table ). The results show total revenues of about USD 655 per hectare against total costs of about USD 461. Land preparation and the opportunity cost of land accounted for 62% of total costs. The net profit margin was 193 USD/ha. Profit was highest in southern Punjab and Sindh and lowest in Pothwar region. In Pothwar region, mungbean is grown under rainfed conditions and most farmers apply neither fertilizers nor pesticides; mungbean yields are low as a result. We note that labor costs, including the opportunity costs of own family labor, were included in the variable costs. A benefit–cost ratio above unity suggests that mungbean production is profitable for the average farmer, even in Pothwar.

Table 4. Cost and returns to mungbean production by region in Pakistan, in USD per hectare, average per farm household, 2016

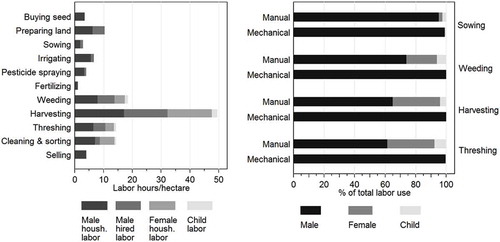

Detailed labor data were collected for Pakistan only. Labor time spent was 129 h per hectare on average. Harvesting, threshing and cleaning of the seeds accounted for 60% of total labor use, which shows that these tasks are very laborious (Figure ). The majority of the labor (76%) was male labor. It must, however, be noted that this question was generally answered by the male respondent and the contribution of female labor may therefore be underreported. Hiring outside labor was common for land preparation, weeding and harvesting, but only male labor was hired. Children contributed about 4.5 h, mostly for harvesting and threshing of the bean pods and cleaning of the grains. A small sample of farmers reported the use mechanization for sowing, weeding, harvesting and threshing. The right pane in Figure compares the relative contribution of men, women and children for tasks that can be mechanized. It suggests that the use of mechanization in mungbean production eliminates the use of female and child labor.

3.2. Consumption practices

The fact that mungbean farmers in Pakistan appear to be semi-subsistent while their counterparts in Uzbekistan appear to be commercial is due to the higher production (higher yield and larger area) in Uzbekistan. In fact, growers in both countries saved about 500 kg of mungbean per year for seed and own household consumption.

In both countries, mungbean is consumed equally by children and adult men and women, including women in reproductive age. Mungbean was not included in every meal or eaten every day, but on average households consumed 8.7 g/capita/day in Pakistan and 7.3 g/capita/day in Uzbekistan as estimated from a 7-day recall (Table ). We did not find a significant difference in mungbean consumption between growers and non-growers.

Table 5. Mungbean consumption by smallholder farmers in Pakistan and Uzbekistan, 2016

The contribution of mungbean to the households’ total dry pulse consumption was 45% in Pakistan and 17% in Uzbekistan. Other pulses consumed included mostly chickpea and lentils in Pakistan and chickpea and kidney beans in Uzbekistan. In Pakistan, most household prepare mungbean (in split-hulled form, called mung dhal) by boiling the beans with lentils and then stir-frying them with onion, garlic, tomato and spices and eaten as a sauce served with rice or bread. In Uzbekistan, the most common preparation is to boil mungbean in broth prepared from sliced onions, tomatoes, carrots and meat, after which rice or pasta is added to make a soup or porridge.

Mungbean is a common food in both countries, but the survey results show that women in charge of meal preparation had very limited knowledge about the nutritional benefits of eating mungbean. In Pakistan, 75% could not tell any nutritional benefit, 12% thought it was good for health but could not say why and 12% indicated that mungbean was good for digestion. Only 1% of the respondents mentioned mungbean as a source of protein. In Uzbekistan, none of the respondents linked mungbean to protein intake, though 12% told it was a source of energy.

3.3. Perceptions

Among the sampled farmers that did not grow mungbean in the past 12 months, 47% in Pakistan and 24% in Uzbekistan did grow the crop at some time in the past (Table ). The main benefits that non-growers associated with mungbean were food to eat (78%), animal fodder (45%), soil fertility (40%) and income (34%) in Pakistan. In Uzbekistan, 42% thought that it could generate income but 39% could not tell any benefit of mungbean. Only 10% of the non-growers in Uzbekistan thought that mungbean could fit in their current crop calendar. In Pakistan, 83% of non-growers thought that mungbean could fit in their crop calendar. Nonetheless, the great majority of non-growers in both countries said that they would be willing to try growing mungbean if provided with seed.

Table 6. Perceptions about mungbean among farmers that did not cultivate it, in proportion of respondents, 2016

Growers and non-growers mentioned a long list of constraints to mungbean production (Table ). The four most frequent problems mentioned by growers in Pakistan were plant diseases, insect pests, poor seed quality and low yields. These all point to the need for improved varieties with better resistance to biotic stresses. In Uzbekistan, the most frequently mentioned constraints were lack of market demand, poor seed quality, rain damage during pod ripening and low crop yields. These point at a wider range of challenges including the need for better varieties but also at the need to create better market opportunities through value chain development.

Table 7. Perceived constraints to mungbean production among growers and non-growers, in proportion of respondents, 2016

Figure shows pest and diseases as perceived by mungbean growers as identified from color photographs of common pests and damage symptoms. This also shows the importance of this issue for farmers in Pakistan. Insect pests such as pod borers and caterpillar were perceived as major pests by farmers in Pakistan. In Uzbekistan, growers identified much fewer pests and diseases, but among these they prioritized bean flies, weevils and urdbean leaf crinkle virus. Growers’ pest and disease identification might be quite different and less accurate than that of a trained expert, but it is nevertheless important information because farmers decide on a course of action based on what they think the problem is.

3.4. Turning constraints into opportunities

There is only a limited involvement of private seed companies in mungbean seed production, which is due to a combination of restrictive seed policies and difficulties in intellectual property rights protection related to open-pollinated crops. Public organizations such as the National Agricultural Research Centre in Pakistan and the Uzbek Research Institute of Plant Industry are dealing with breeding of improved varieties using breeding lines and genebank accessions from the World Vegetable Center’s international mungbean improvement program (Schafleitner et al., Citation2015), but there is a lack of a clear strategy on how to improve mungbean varieties for farmers in an effective and timely manner. Joshi et al. (Citation2014) described the use of client-oriented breeding including participatory varietal selection and the distribution of free seed samples for evaluation by farmers as an effective approach in Nepal. This is a potentially effective approach for Pakistan and Uzbekistan as it addresses the seed constraint and builds on non-growers’ interest to try and produce mungbean if provided with seeds. The World Vegetable Center is currently working with local organizations to test new varieties in mother–baby trials.

In Pakistan, the average mungbean yield is low at about 1 ton/ha, particularly in the wheat-fallow system of Pothwar region where mungbean is produced under rainfed conditions. Lack of water was the most frequently mentioned constraint by non-growers. Mungbean growers identified insect pests and plant diseases as their main constraint. This can be addressed through a combination of improved varieties and good agricultural practices including integrated pest management. The majority of non-growers (83%) thought that mungbean would actually fit in their current cropping calendar and would be willing to try it if provided with seed. In Pothwar region and Sindh province, mungbean competes with other crops for farm resources, but this is mostly for water and labor as there are ample amounts of land under fallow. Mechanization could contribute to solving labor shortages during harvesting and may reduce drudgery of farm work, especially for women and children. However, specific research would be needed to determine if this benefits women or implies a loss of income opportunities for them. Non-growers see mungbean as an important food crop, though virtually no farmers had knowledge about the nutritional benefits of the crop. It is therefore important to promote new varieties as package together with good agricultural practices but also nutritional information, which could stimulate demand and increase the benefit to human health.

In Uzbekistan, the main constraints to area expansion of mungbean as a catch crop are the perceived lack of market demand for the crop (and related low market prices), the lack of quality seed supplies and the risk of rain damage during pod ripening. Field trials conducted as part of this project also experienced problems with frost damage at the end of the season. Lack of market demand is potentially addressed through government promotion of export opportunities for mungbean, which should be possible given that legume prices in South Asia show a rising trend as supply falls short of demand. The promotion of mungbean to farmers will require more information about how to fit the crop into existing cropping calendars (as only 10% of the non-growers thinks it can fit), information about the financial gains of producing mungbean (as 42% of the non-growers does not think that it would be profitable), information about the contribution of mungbean to soil quality improvement and information about the benefits of mungbean consumption to human health (as none of the respondents was able to tell this).

4. Conclusion

There is a great potential to improve mungbean yield and production and to expand it as a catch crop in wheat systems of Pakistan and Uzbekistan. Exploiting this potential would require governments to address constraints in the supply of quality seeds in Pakistan and Uzbekistan and to improve the functioning of mungbean value chains in Uzbekistan. Governments, private sector and non-governmental organizations, with the support of foreign donors, could promote mungbean expansion through a combination of improved varieties and targeted information about production practices, financial costs and returns, and potential benefits to soil quality, crop yields and human nutrition so that farm managers make better-informed decisions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Arid Zone Research Institute, Bhakkar, the Pulses Program and Agricultural Economics Research Institute at NARC, the provincial extension departments in Pakistan, and farmers in both countries.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saima Rani

Saima Rani is Scientific Officer at the Agricultural Economics Research Institute, PARC National Agricultural Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan. She holds a M.Sc in Economics from International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Pepijn Schreinemachers is Lead Scientist—Impact Evaluation at the World Vegetable Center. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from the University of Bonn, Germany, and an MSc in Development Studies from Wageningen University, the Netherlands.

Bakhodir Kuziyev is Site Coordinator for the World Vegetable Center based in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. He holds an MS in Agricultural Economics from Missouri University, USA.

Notes

1. As reported by http://dollaruz.net/godovoj.html.

References

- Adam, R. I., Sindi, K., & Badstue, L. (2015). Farmers’ knowledge, perceptions and management of diseases affecting sweet potatoes in the Lake Victoria Zone region, Tanzania. Crop Protection, 72, 97–107. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.010

- Ali, M., Malik, I. A., Sabir, H. M., & Ahmad, B. (1997). The mungbean green revolution in Pakistan. Technical Bulletin No. 24, Shanhua: AVRDC.

- Bobojonov, I., Lamers, J. P. A., Djanibekov, N., Ibragimov, N., Begdullaeva, T., Ergashev, A.-K., & Kienzler, K., Eshchanov, R., Rakhimov, A., Ruzimov, J., Martius, C. (2012). Crop diversification in support of sustainable agriculture in Khorezm. In C. Martius, I. Rudenko, J. P. A. Lamers, P. L. G. Vlek, et al. (Eds.), Cotton, water, salts and soums: Economic and ecological restructuring in Khorezm, Uzbekistan (pp. 219–233). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Bourgault, M., Madramootoo, C. A., Webber, H. A., Dutilleul, P., Stulina, G., Horst, M. G., & Smith, D. L. (2013). Legume production and irrigation strategies in the aral sea basin: Yield, yield components, water relations and crop development of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and Mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek). Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 199(4), 241–252. doi:10.1111/jac.12016

- Byerlee, D., & White, R. (2000). Agricultural systems intensification and diversification through food legumes: Technological and policy options. In R. Knight (Eds.), Linking research and marketing opportunities for pulses in the 21st Century: Proceedings of the third international food legumes research conference, 31–46. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.31

- FAO. (2016a). FAOSTAT Database on production. Rome. FAO Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved December 9, 2016, from http://faostat.fao.org/site/339/default.aspx

- FAO. (2016b). Save and Grow in practice: Maize, rice, wheat. A guide to sustainable cereal production. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Ghosh, P. K., Bandyopadhyay, K. K., Wanjari, R. H., Manna, M. C., Misra, A. K., Mohanty, M., & Rao, A. S. (2007). Legume effect for enhancing productivity and nutrient use-efficiency in major cropping systems–An indian perspective: A review. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 30(1), 59–86. doi:10.1300/J064v30n01_07

- Government of Pakistan. (2015). Agricultural statistics of Pakistan 2014–2015. Islamabad: Ministry of Food Security and Agricultural Research.

- HanumanthaRao, B., Nair, R. M., & Nayyar, H. (2016). Salinity and high temperature tolerance in mungbean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] from a physiological perspective. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7, 957. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00957

- Haqqani, A. M., Zahid, M. A., & Malik, M. R. (2000). Legumes in Pakistan. In C. Johansen, J.M. Duxbury, S.M. Virmani, C.L.L. Gowda, S. Pande, P.K. Joshi (Eds.), Legumes in rice and wheat cropping systems of the indo-gangetic plain: Constraints and opportunities (pp. 98–128). Patancheru, Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics.

- Joshi, K. D., Khanal, N. P., Harris, D., Khanal, N. N., Sapkota, A., Khadka, K., … Witcombe, J. R. (2014). Regulatory reform of seed systems: Benefits and impacts from a mungbean case study in Nepal. Field Crops Research, 158, 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2013.12.011

- Joshi, P. K., Gulati, A., Pratap, S. B., & Tewari, L. (2004). Agriculture diversification in South Asia: Patterns, determinants and policy implications. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(24), 2457–2467.

- Nair, R. M., Yang, R. Y., Easdown, W. J., Thavarajah, D., Thavarajah, P., Hughes, J., & Keatinge, J. D. (2013). Biofortification of mungbean (Vigna radiata) as a whole food to enhance human health. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 93(8), 1805–1813. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6110

- Namazov, F. B., Khalikov, B. M., & Khaitov, B. B. (2015). The impact of short crop rotation and residues on soil fertility and cotton yield under arid condition. International Journal of Applied Agricultural Research, 10(2), 109–113.

- Peoples, M. B., Brockwell, J., Herridge, D. F., Rochester, I. J., Alves, B. J. R., Urquiaga, S., Boddey, R. M., Dakora, F.D., Bhattarai, S., Maskey, S.L., Sampet, C., Rerkasem, B., Khan, D.F., Hauggaard-Nielsen, H., Jensen, E.S. (2009). The contributions of nitrogen-fixing crop legumes to the productivity of agricultural systems. Symbiosis, 48(1–3), 1–17. doi:10.1007/BF03179980

- Pingali, P. L., & Rosegrant, M. W. (1995). Agricultural commercialization and diversification: Processes and policies. Food Policy, 20(3), 171–185. doi:10.1016/0306-9192(95)00012-4

- Rahman, S. (2009). Whether crop diversification is a desired strategy for agricultural growth in Bangladesh? Food Policy, 34(4), 340–349. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.02.004

- Schafleitner, R., Nair, R. M., Rathore, A., Wang, Y.-W., Lin, C.-Y., Chu, S.-H., … Ebert, A. W. (2015). The AVRDC – The World Vegetable Center mungbean (Vigna radiata) core and mini core collections. BMC Genomics, 16(1), 344. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1556-7

- Schreinemachers, P., Balasubramaniam, S., Boopathi, N. M., Ha, C. V., Kenyon, L., Praneetvatakul, S., … Wu, M.-H. (2015). Farmers’ perceptions and management of plant viruses in vegetables and legumes in tropical and subtropical Asia. Crop Protection, 75, 115–123. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2015.05.012

- Shanmugasundaram, S., Keatinge, J. D. H., & d’Arros Hughes, J. (2009). The mungbean transformation. diversifying crops, defeating malnutrition. In D. J. Spielman & R. Pandya-Lorch (Eds.), Millions fed: Proven successes in agricultural development (pp. 103–108). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Weinberger, K. (2005). Assessment of the nutritional impact of agricultural research: The case of mungbean in Pakistan. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 26(3), 287–294. doi:10.1177/156482650502600306

- Welch, R. M., & Graham, R. D. (1999). A new paradigm for world agriculture: Meeting human needs: Productive, sustainable, nutritious. Field Crops Research, 60(1–2), 1–10. doi:10.1016/S0378-4290(98)00129-4

- The World Bank. (2016). World development indicators. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved September 8, 2016, from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD

- World Health Organization. (2008). Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: A guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. Geneva: Author.