Abstract

Water hyacinth invasion and its associated effects have been reported to be a source of problems to riparian people, posing challenges to activities like fishing and farming along invaded waterbodies. Based on cross-sectional research with 55 farmers who were sampled using the snowballing sampling technique, this study assesses the effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming activities in the Jomoro District. Four communities along the River Tano and Tano Lagoon in the district were purposively selected for the study. Individual surveys and Focus Group Discussions were used as data collection methods to assess the situation. Among the problems posed by water hyacinth invasion to smallholder farming in the study area were the destruction of farm produce due to the blockade caused by water hyacinth on the water bodies, reduced profit from farm output and economic hardship. We recommend that interactive participation involving farmers, district and traditional authorities, and rural development agencies should be adopted to control the spread of the water hyacinth to a level where it will cease to impede the activities of the riparian people.

Public Interest Statement

Water hyacinth invasion threatens socio-economic activities in riparian communities in the Jomoro District of Ghana. This study assesses the effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming in communities along River Tano and Tano Lagoon in the Jomoro District, based on data gathered using snowballing non-probability sampling procedure. The study was inspired by the general absence of research in Ghana to explain the effects of water hyacinth invasion on farming activities. It was found that water hyacinth invasion of River Tano and Tano Lagoon led to the destruction of farm produce, increased travel time used to access farms and a consequent reduction in farmers’ income. Understanding these effects can improve programs and policies to addresses the water hyacinth menace. A study of water hyacinth invasion issues can also assist government and non-government organizations to assist communities and individuals whose livelihood activities have been affected by the invasion.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Renewed attention has recently been given to the importance of small-scale farming. A demonstrative example is seen in the proclaiming of 2014 as the International Year of Family Farms (Spoor, Citation2015). According to the theory of peasant economy by Alexander Chayanov, peasant farms are characterised by the employment of no hired wage labour, but mainly depend on the work of family members (American Economic Association, Citation1966). The general aspect of the theory which attracted contemporary attention was the potrayal of peasant farms as an economic form which differed from capitalist farming in an environment dominated by capitalism. Chayanov defined the peasant economy as one characterised by family labour and survival strategies which are different from those of capitalist enterprises (Teodor, Citation1986). It is claimed that peasant economy is going to play a critical role in the twenty-first century, both within the context of backward and advanced economies. The reason is that issues like climate change and world demography dynamics are putting the basic assumption of an industrially based economic progress to question (Belletti, Citation2015). The future of the world critically depends on peasant farmers because peasant agriculture provides the world with at least 70% of its food (Ploeg, Citation2017; Samberg, Gerber, Ramankutty, Herrero, & West, Citation2016; Spoor, Citation2015). Peasant farmers, therefore, play a central role in food security, income, agricultural production intended for industries and exports, employment and natural resource management (Fami, Samiee, & Sadati, Citation2009).

While the theoretical debates about the disappearance of peasant farming continue (Hilmi & Burbi, Citation2015; Ploeg, Citation2017), the contributions of peasant farmers have shown that the activity is formidable and quickly recovers from stebacks, thereby helping to stabilize, balance and enrich societies (Hilmi & Burbi, Citation2015). However, this mode of farming is faced with many challenges (Torero, Citation2011). Public policies toward the development of peasant farming are deficient, investments are lacking, and many of the smallholder farmers receive little to no support (Spoor, Citation2015). Environmental conditions such as climate change also have direct impact on production, since peasant farming mainly depends on climatic conditions like rainfall. Land productivity is also on a decline due to land degradation and physical processes like water erosion (Shalaby, Al-Zahrani, Baig, Straquadine, & Aldosari, Citation2011). These pose a direct threat not only to the livelihoods of peasant farmers but to food security, sustainability, overall economic development, etc. (Ploeg, Citation2008). In developing countries, this impact is particularly significant because agriculture constitutes employment and income sources for the majority of the population (Enete & Onyekuru, Citation2011). Coupled with the socio-economic and environmental challenges confronting some of the smallholder farmers along the River Tano and Tano Lagoon are the challenges posed by water hyacinth invasion of the two water bodies.

Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) is a well-known ornamental plant, found in water gardens and aquariums (Bhattacharya & Kumar, Citation2010). It is a perennial aquatic herb which belongs to the pickerelweed family Pontederiaceae (Gichuki, Omondi, Boera, Okorut, Matano, Jembe & Ofulla, Citation2012). Water hyacinth is recognised as one of the top 10 worst weeds in the world (Shanab, Shalaby, Lightfoot & El-Shemy, Citation2010), listed by law as a noxious weed in several African countries (Onyango & Ondeng, Citation2015). The plant is indigenous to Brazil, Amazon basin and Ecuador region (Patel, Citation2012). It was introduced as an ornamental species to adorn water bodies in many countries due to its pleasing appearance, but was later discovered to be an invasive species (Patel, Citation2012). It has proven to be a source of significant economic and ecological problems to many subtropical and tropical regions of the world (Jafari, Citation2010). Due to the blockade caused by water hyacinth on water bodies, it brings about high agricultural and economic loses (Borokini & Babalola, Citation2012) since farmers who cross invaded water bodies to access their farms cannot do so in the presence of the dense mats of the weeds.

In Africa, water bodies invaded by water hyacinth include Ologe Lagoon, Agbara and Badagry Creeks (all in Nigeria), River Niger (Mali), River Zambezi (Zambia) and the Nile River (Egypt) (Borokini & Babalola, Citation2012; Dagno, Lahlali, Diourte, & Haissam, Citation2012; Patel, Citation2012). In Ghana, the Volta and Tano Rivers have been invaded by water hyacinth (De Graft-Johnson, Blay, Nunoo, & Amankwah, Citation2010; Hauser, Wernand, Korangteng, Simpeney, & Sumani, Citation2014). This is partly due to the inflow of erosion run-off which carries plant nutrients from untreated wastewater, sewage, fertilized farmlands and decomposed plant and animal residues into water bodies (Hauser et al., Citation2014). In the peak season of water hyacinth invasion, movement of people on the Abby-Tano lagoon and the River Tano to carry out economic activities like farming and fishing almost becomes impossible due to the blockade created by the mats of the water hyacinth. The activities of boat operators along River Tano and Abby-Tano Lagoon also come to a halt. The lack of operations means that boat operators are unable to make adequate income in the peak season of the invasion and this affects their livelihood (Ghana News Agency, Citation2007). Water hyacinth invasion of the River Tano and Tano Lagoon thus poses as a negative externality which reduces the incomes of farmers, fishermen, boat operators and other categories of people whose livelihoods are tied to the two water bodies.

It has been indicated that water hyacinth was introduced into the River Tano and Abby-Tano Lagoon from a canal in La Cote d' Ivoire called Le Canal d' Assinie that joins the Abby-Tano Lagoon. The weeds were reported to have been introduced into the canal by expatriates who resided in hotels located along the canal. These foreigners used the water hyacinth in their flower pots and released the excess into the canal. Later, stolons of the weeds got stuck to boats which brought wares through the canal to communities located along River Tano and Abby-Tano Lagoon. According to Navaro and Phiri (Citation2000), water hyacinth was first detected in Ghana in 1984. However, the outbreak of water hyacinth in River Tano and Abby-Tano Lagoon was detected between 1987 and 1993 by the Jomoro District office of the Plants Protection and Regulatory Service Directorate (PPRSD), while the invasion became severe between 1994 and 1995. An initial release of weevils to help control the weeds in the two water bodies was made between March and April, 1994 (FAO, Citation1998). Water hyacinth grows at a rate of 2 ×105 hectares per year, spreading at an alarming rate with broad environmental tolerance (Zhang, Zhang & Barret, Citation2010). It is the most widespread and damaging aquatic plant species (Onyango & Ondeng, Citation2015). Therefore, despite the presence of other invasive species like hippo grass, water lettuce and water ferns in the study area (De Graft-Johnson, Citation1995; De Graft-Johnson et al., Citation2010); water hyacinth was selected as the object of interest in this study because it easily blocked access routes on the two water bodies.

An exploration of the literature on water hyacinth indicates that various researches have been conducted into the effects of water hyacinth on fish stock (Kateregga & Sterner, Citation2009; Waithaka, Citation2013), appropriate control measures of the water hyacinth (Jayan & Sathyanathan, Citation2012; Ray & Hill, Citation2013), its allelopathic effects (Shanab, Shalaby, Lightfoot, & El-Shemy, Citation2010) as well as the distribution and socio-economic importance of water hyacinth (Firehun, Struik, Lantinga, & Taye, Citation2014). In Ghana, there exists little documentation about the water hyacinth invasion (De Graft Johnson, Citation1995; De Graft-Johnson et al., Citation2010; Hauser et al., Citation2014; Annang, Citation2012). However, none of the existing researches in Ghana particularly focuses on the effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming. This study, therefore, assesses the effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming along River Tano and Tano Lagoon in Ghana. It examines how water hyacinth invasion of River Tano and Tano Lagoon negatively affects the activities of smallholder farmers who reside in communities along the two water bodies, the effects of the invasion on the incomes of farmers and how from the perspectives of the farmers, the invasion will affect their future living conditions.

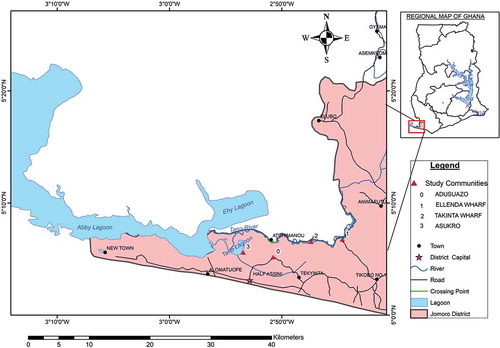

1.1. Profile of study area

The Jomoro District has an area extent of 1,344 km2. This comprises about 5.6% of the total land area of the Western Region of Ghana. The district lies between latitude 04°55´–05°15´N and longitude 02°15´—02°45´W (Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Citation2015). It has an extensive rainforest with high rainfall which falls in two wet seasons. Temperatures in the district are uniformly high throughout the year (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2014). The high rainfall and temperature favour food crop farming.

1.2. River Tano and Abby-Tano Lagoon

The Tano River Basin is one of the major south-western river basin systems of Ghana. It is located between latitudes 5°N and 7°40ʹ N and longitudes 2°00ʹW and 3°15ʹW. The Tano River is transboundary since the last 100 km of the downstream section of the river straddles the international boundary between Ghana and La Côte d’Ivoire before flowing into the Aby-Tano-Ehy lagoon system (Water Resources Commission, Citation2012).

The Abby-Tano Lagoon also lies in the south-western part of the Jomoro District. While the Abby Lagoon is approximately located between latitude 05°05ʹ18.1ʺ N and longitude 002°56ʹ42.8ʺ W, the Tano Lagoon lies approximately between latitude 05°05ʹ38.1ʺN and longitude 002°05ʹ30.9ʺW but both are interconnected to form a lagoon complex with the Ehy Lagoon in La Cote d’ Ivoire (Finlayson, Ntiamoa-Baidu, Tumbulto, & Storrs, Citation2000). The Abby-Tano Lagoon is transboundary between Ghana and La Côte d’Ivoire, but most of the lagoon system is located in La Côte d’Ivoire. It discharges into the sea in La Côte d’Ivoire (Water Resources Commission, Citation2012) at Assinie Manvea.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

The cross-sectional study design was adopted in the collection of data. Thus, the effects of water hyacinth invasion on the activities of smallholder farmers was studied only once in all the selected communities. Besides, data was collected from cross-sections of the populations of the selected communities (Kumar, Citation2011). The mixed method, which involved the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data from the field, was also used. According to Ganle, Afriye, and Segbefia (Citation2015), a strictly quantitative design such as a survey offers limited space to respondents. A partly qualitative research design that adopted interviews and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) as methods of data collection was therefore appropriate to provide information that augmented those gathered from the survey. Quantitative data collected in the study included respondents' responses about whether water hyacinth invasion of River Tano and Tano Lagoon had negatively affected their activities, the effects of the invasion on their incomes and their perceptions about how their future living conditions will be in the face of the invasion. Qualitative data, on the other hand, included direct quotes from respondents.

2.2. Sampling procedures

Non-probability sampling procedures were adopted in the selection of the study communities and respondents. In the first stage, four riparian communities close to the River Tano and Tano Lagoon were purposively selected for the study. According to the distance decay effect theory, as the distance between two localities increases, the level of interactions between them decline (Dempsey, Citation2012). It was therefore presumed that communities that were closer to the two water bodies had their activities being more negatively affected by the water hyacinth invasion. The selected communities, therefore, were Asukro along the Tano Lagoon, and Ellenda Wharf, Takinta Wharf and Adusuazo along the River Tano. Sequel to the selection of the communities, snowballing non-probability sampling procedure was used to select smallholder farmers whose activities had been affected by water hyacinth invasion in order to administer the questionnaires. In using the snowballing sampling technique, a network of smallholder farmers who worked along the River Tano and Tano Lagoon was used to select the respondents. From the start, a few smallholder farmers from the selected communities were sampled and the required data was collected from them. They were then asked to identify and direct the researcher to other smallholder farmers in the communities, and those farmers selected by them became a part of the sample. Data was then collected from them and then these people were asked to identify other farmers who became the basis of further data collection. This process continued until the required number was reached (Kumar, Citation2011). The snowballing sampling technique was adopted since the researcher did not have the records of farmers whose farming activities had been affected by water hyacinth invasion. In all, a total of 55 farmers were selected for the study. Out of that, there were five (5) from Asukro, two (2) from Takinta Wharf, three (3) from Ellenda Wharf and (45) from Adusuazo. This was based on their respective population sizes.

2.3. Data collection methods

In the quest to reproduce respondents’ views about the effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were employed to collect qualitative data from the farmers. Four FGDs were organised in two of the selected communities. They were Adusuazo along the River Tano and Asukro along the Tano Lagoon. Participants in the FGDs were grouped based on gender (men and women). This was to make sure respondents from each gender category freely contributed their views to the discussions without fear of intimidation from participants from the other gender identity. Each focus group had a membership range between eight and twelve. The limited numbers were to help in the effective management of the groups to yield fruitful discussions (Mumin, Gyasi, Segbefia, Forkuor, & Ganle, Citation2018).

The discussions were held in the local dialect (Nzema) of the study communities, so as to serve the linguistic need of the participants. They were also organised in enclosed places to prevent external interferences that could affect the process. Each discussion lasted for about 60 min. The discussions were facilitated by the researcher and a research assistant. The views of participants were recorded using an audio recorder after seeking their verbal consents. Information derived from the interviews and questionnaire administrations were supplemented with secondary data gathered from research papers, journal articles and e-materials.

2.4. Research instruments

The study made use of two main instruments in the data collection process. Open-ended interview guides were used in the focus group discussions while interviewer-administered questionnaires were used in collecting data from the 55 respondents. Both close and open questions were raised in the questionnaires. This was to give respondents the opportunity to adequately contribute descriptive and detailed information to the study since the close questions might have limited them in their quest to contribute viable information to the study.

2.5. Data analysis

The study made use of descriptive statistics including percentages, frequency tables and pie charts in statistical package for social sciences (SPSS, V 16.0) and Microsoft Excel to analyse quantitative data. On the other hand, some of the responses from the respondents were quoted directly in the analyses of qualitative data. The audio records taken during the FGDs were transcribed into English. An in-depth understanding of emerging patterns in the responses was developed after a thorough reading of the transcript. Information related to the objective of the study was then extracted and used to support quantitative data.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Effects of water hyacinth invasion on smallholder farming

3.1.1. Respondents’ perception about whether their farming activities had been negatively affected by water hyacinth invasion

The blockade created by water hyacinth in invaded waterways impedes the use of vessels, including canoes on such water bodies. The net effect is that people who commute on such water bodies to access their farms may have their activities coming to a halt. In this study, the authors first found out the extent of the effect of water hyacinth invasion on farming by analysing the number of farmers among the respondents whose activities had been negatively affected by the water hyacinth invasion. The results have been presented in Table .

Table 1. Number of farmers whose activities had been negatively affected by water hyacinth invasion in the Jomoro District.

Table indicates that a significant majority (92.7%) of the smallholder farmers in the study reported that their activities across River Tano and Tano Lagoon had been negatively affected by the water hyacinth invasion. The table indicates, for example, that all respondents from three of the communities reported the blockade created by the water hyacinth negatively affected their activities. This revealed the greatness of the effect of water hyacinth invasion among smallholder farmers in the study area. The large number of farmers who reported that water hyacinth invasion negatively affected their activities is a confirmation of Patel (Citation2012) that water hyacinth invasion generates public outcry.

3.2. Effects of water hyacinth invasion on farming activities

The authors sought to examine how water hyacinth invasion affected smallholder farmers in the study area. It was reported in the study that the blockade created on the Tano River and Tano Lagoon posed challenges to people who commuted on them to access their farms. A summary of the effects has been presented in Table .

Table 2. Effects of water hyacinth on smallholder farming in the Jomoro District.

The study revealed that the presence of water hyacinth in the River Tano and Tano Lagoon affected farming activities in diverse ways. The effects of the invasion have been discussed in the following subsections.

3.2.1. Destruction of farm produce

Table indicates that 81.8% of the farmers reported that the water hyacinth invasion led to the destruction of produce on their farms. They indicated that in the dry season (January to March), it became difficult for them to cross the River Tano and the Tano Lagoon to their farms since the invasion reached its peak in that period. This problem was mainly reported at Adusuazo where many farmers interviewed crossed the River Tano to their farms. The reduced frequency of farm visits led to the destruction of farm produce, including vegetables. In addition, when the water hyacinth covered the surface of the River Tano, farmers could not cross to weed their farms; while those with cocoa farms could not spray the cocoa trees. Once the farms became weedy, rodents fed on the foodstuffs and ripened cocoa pods while the younger cocoa plants did not grow well. The matured plants did not also bear much pods, leading to a reduction in the number of bags of cocoa harvested. Besides, when the cocoa pods were not sprayed, insects fed on the new buds and they decomposed. These reports affirm Javald (Citation2010), and Iderawumi and Friday (Citation2018) that weeds negatively affect plant growth by reducing tillering and shoot biomass and by competing with plants for space, light, nutrients and moisture which otherwise could have been utilised by plants. Weeds also suppress root biomass and reduce crop yield. The increased duration of weeds on farms also interfere with plant growth and development by reducing their maximum leaf area, height as well as their quality grades and the market value (price) that is offered for the affected farm produce, example cocoa grades 1:2:3 (Evans, Knezevic, Lindquist & Shapiro, Citation2003; Iderawumi & Friday, Citation2018). One farmer in this study commented on the effects of water hyacinth invasion on farm produce in the following words during a Focus Group Discussion:

“The water hyacinth prevents me from crossing to spray the cocoa farm. In the dry season, I cannot go to the farm to weed to help the cocoa plants grow well. In the rainy season when you weed, the weeds quickly grow. Sometimes too the farm is flooded and this prevents you from working. For about three months, I may not get the chance to visit the farm due to the blockade by the water hyacinth. Other crops like garden eggs, okro and tomatoes all get rotten on the farm” (A 35- year old farmer at Adusuazo; July, 2016).

It was reported in the study that cocoa farmers harvested their crops three or four times in a year, but the lowest quantity of harvest was always recorded in the dry season. However, even though the blockade by water hyacinth that led to the destruction of the cocoa pods may be a contributing factor, the climatic condition of the location may be partly responsible since in the dry season the area comes under the influence of the North-East Trade Winds, leading to heavy lost of moisture from the soil and high temperature which affect plant growth. Drought and heat stresses are physical environmental conditions that limit plant growth and sustainable agriculture throughout the world. When the humidity of the soil and relative air humidity are low coupled with high ambient temperature (Lipiec, Doussan, Nosalewicz & Kondracka, Citation2013), plants have low yield. It is reported that the combined effects of both heat and drought on the yield of many crops is stronger than the effects of any one of them (Dreesen, De Boeck, Janssens & Nijs, Citation2012; Rollins, Habte, Templer, Colby, Schmidt & von Korff, Citation2013).

Apart from farmers' inability to cross the two water bodies to harvest their produce, it also became difficult to prepare new lands to begin new cultivation. Meanwhile, it was reported that the fertile land in a community like Adusuazo was the one located along the Tano River. However, Zidana et al. (Citation2007) in their study of the factors influencing the cultivation of the Lilongwe and Linthipe River Banks in Malawi reported that household size, main occupation, education, market availability and land holding size were important factors influencing farmers to engage in river bank cultivation. The reports from the farmers reflect the findings of other studies that water hyacinth brings about loses to agriculture (Borokini & Babalola, Citation2012; Ndimele, Kumolu—Johnson, & Anetakhai, Citation2011; Patel, Citation2012; Shanab et al., Citation2010).

3.2.2. Increased travel time

Table indicates that 5.5% of the farmers reported that the water hyacinth invasion increased the length of time they used to access their farms. This happened when farmers had to use their hands to remove water hyacinth in their designated routes in order to pave way for their canoes. In a study conducted by Ogulande (Citation2002) also, 70% of the respondents reported that the presence of water hyacinth in waterways in the Ondo State made navigational routes risky. This was because paddling of canoes in the dense mats of the water hyacinth became a hectic task. The free movement of vessels was therefore impeded. One respondent in this study explained in the following words during an in-depth interview:

“I can use about 3 hours to travel to the farm instead of the normal 30 minutes because of the presence of the water hyacinth. I have to use my hands to remove the weeds to create path” (A 34-year old farmer at Ellenda Wharf; July, 2016).

3.2.3. Abandoning of farms

The blockade caused by water hyacinth had led to some farmers abandoning their farms across the Tano Lagoon (Figure ) as reported by three farmers from Asukro. This was mainly due to their inability to overcome the constraints imposed on their farming activities by the physical encvironment. Their strategy is in line with the basic assumption of the theory of peasant economy that smallholder farmers use survival strategies which differ from those adopted in capitalist farming. In capitalist farming which is characteristically marked by high profit and the use of advanced technology (Djurfeldt, Citation2016), this could have been easily overcome. The three farmers had relocated their farming activities to sections of the community where they did not need to cross the Tano Lagoon before accessing their farms. Similarly, in the study of Ogulande (Citation2002) in riverine areas in Ondo State (Nigeria), it was reported that due to water hyacinth invasion, people abandoned fishery activities for other menial jobs like smallholder farming and petty trading. Besides, from 1989 when water hyacinth infested the riverine areas in Ondo State, there was a gradual decrease of human population which cuts across the ages of people who were involved in fishing and its related activities. This was mainly due to the blockade of most of the waterways by water hycinth. The three respondents in this study were more resilient than some fisher folks in the Nduga village of the Lake Victorian Basin. A study by Kamau, Njogu, Kinyua, and Sessay (Citation2015), has indicated that water hyacinth invasion of the Lake Victoria rendered some fishermen jobless in the Nduga community along the lake. This led to an increase in crimes such as robbery among young men who were negatively affected by the water hyacinth invasion. Besides, others engaged in the intake of illicit brews and related substance abuse when water hyacinth invasion made them vulnerable and idle. However, factors like age and occupational differences may impact on how people respond to negative externalities from their environment. For example, while those in Nduga village were young men, those in Asukro were in their 50s. A man explained how he abandoned his farm in the following words during an in-depth interview:

“My wife and I used to have a coconut farm at Tweabo. By the time the coconuts were ready for collection, the water hyacinth had blocked the Tano Lagoon. Besides, we had vegetables farm with okro, eggplants, etc. We abandoned the vegetables farm because anytime the produce was ready for harvest, the water hyacinth blocked our access route, leading to their destruction. That is why we left the place. If the hippo grass and water hyacinth are controlled, I will return to that farm. The water hyacinth has really affected our finances. We could not recover the money invested in our vegetables farm at Tweabo” (A 50- year old farmer at Asukro; August, 2016).

Four (7.3%) farmers, however, reported that their activities were not directly affected by the water hyacinth invasion. This was because they permanently stayed in villages across the River Tano where they engaged in their farming activities. In the peak season of the invasion, they stayed in the villages to take care of their farms rather than staying at Adusuazo. However, these respondents were affected indirectly by the water hyacinth invasion in their quest to commute between their villages and Adusuazo to sell their farm produce. This confirms Waithaka (Citation2013), that water hyacinth invasion impedes transportation.

3.3. Effects of water hyacinth invasion on income

It is no doubt that the negative effects of water hyacinth invasion on farming activities along the River Tano and the Tano Lagoon will indirectly affect the incomes of farmers. Table presents a summary of the effects of water hyacinth invasion on farmers’ incomes.

Table 3. Effects of the water hyacinth invasion on the incomes of farmers in the Jomoro District.

Table indicates that a significant majority of the respondents reported the water hyacinth invasion brought about a reduction in their incomes. Spatially, Adusuazo recorded the highest percentage because of the large sample of farmers from the community. However, all the farmers interviewed from Takinta Wharf and Asukro reported their incomes decreased in the face of the water hyacinth invasion. According to Wortman and Lovell (Citation2013), environmental threats to agriculture do not only lead to food insecurity, but also results in limited resources availble to farmers. These resources include finance. The 14.5% farmers in this study who reported their incomes remained the same during the period of water hyacinth invasion included the 7.3% (Table ) who reported they were not affected by the invasion and others who had just begun their farming activities across the two water bodies. At Adusuazo, for example, there were farmers who reported their incomes were not affected because the cocoa farms they had across the River Tano were new and hence the plants had not started bearing pods.

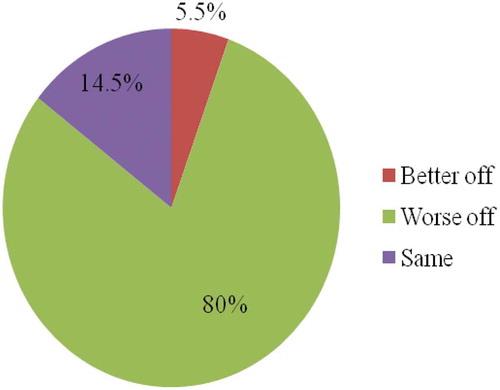

3.4. Foreseen living conditions due to water hyacinth invasion

Due to the highly negative effect of water hyacinth invasion on the incomes of farmers, the predictions they made about their future living conditions in the presence of the water hyacinth were correspondingly negative. The results of the analysis about how respondents perceived their future living conditions would be in the presence of the water hyacinth have been presented in Figure .

Figure shows that a significant majority (80%) of the smallholder farmers perceived that in the future their living conditions will be worse off if the water hyacinth continues to remain at a level where its coverage of the two water bodies will pose challenges to their farming activities. These farmers perceived that the blockade created by water hyacinth will continue to deny them access to their farms, which would lead to the destruction of their farm produce and consequent reduction in their incomes. Indeed, any negative environmental externality whether it is water hyacinth invasion, air pollution, water pollution or land degradation is a threat to the sustainability of agriculture (Wortman and Lovell, Citation2013). However, a few respondents reported that their living conditions will be better in the presence of the water hyacinth. Among these were respondents who reported their engagement in other livelihood activities such as trading and artisanship will enable them to cope with the effects of water hyacinth invasion on their farming activities. In spite of the negative effects of the invasion, these respondents were of the view that the incomes they generated from these livelihood activities were higher than those they derived from farming. Their ability to improve upon their living conditions in the future will, therefore, be largely influenced by the other livelihood activities rather than farming which was being threatened by water hyacinth invasion. Similarly, Thuo (Citation2010) reported that families in Nairobi who formerly depended on farming for food and income shifted their attention to non-farm activities due to declining agricultural opportunities. According to Adigun, Bamiro and Adedeji (Citation2015), farming alone cannot provide sufficient means of sustenance in most rural areas, thus many people engage in non-farm activities as a means of earning a living. This is partly due to the decline in agricultuaral productivity which is a result of unfavourable agro-climatic conditions (Rantso, Citation2016). Among respondents who indicated their living conditions will not change in the future were the 7.3% (Table ) farmers who reported the weeds had no impact on their farming activities. Others were also of the view that livelihood diversification would help sustain their current standard of living.

4. Summary, conclusion and recommendations

The study discussed the effects of water hyacinth invasion on the activities of smallholder farmers in riparian communities along River Tano and Tano Lagoon. The study discovered that water hyacinth invasion undermined farming activities especially in the dry season, from January to March, when the invasion reached its peak. The blockade by water hyacinth reduced the frequency at which people assessed their farms leading to the destruction of farm produce, reduced profit and in a few cases the abandoning of farms. There was, therefore, an inverse relationship between smallholder farming activities and water hyacinth invasion. When the amount of water hyacinth in the two water bodies increased, a blockade was created and that led to a reduction in farming activities across the water bodies. Since the farming communities along River Tano and Tano Lagoon depend largely on transportation on these water bodies to access the sources of their livelihood, their quest to sustain themselves economically should be easily made possible through interactive participatory management approach involving the farmers, district authorities, traditional leaders and rural development agencies to ensure the control of the water hyacinth. Smallholder farmers should be made to participate in joint analysis of the problems created by water hyacinth invasion and the possible solutions, with both the traditional and District Assembly authorities. This will lead to action plans and the strenghtening of existing local institutions whose mandate it is to address the water hyacinth invasion problem. When smallholder farmers take control and ownership over local decisions to curb the water hyacinth menace, they will have a stake in maintaining structures or practices laid down to address the problem. We also recommend that further studies should be carried out to quantify the economic effects of water hyacinth invasion on farming activities. This will help decision makers such as traditional and local government authorities to obtain solid information on the economic effects of water hyacinth infestation on farmers. Such information will then guide authorities in policy formulation and implementation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emmanuel Honlah

Emmanuel Honlah holds Bachelor of Arts in Geography and Rural Development (KNUST), Master of Arts in Environmental Management and Policy (University of Cape Coast) and Master of Philosophy in Geography and Rural Development (KNUST). His interest areas are Urban Geography, Environmental Management and Policy, and Rural Development. He focuses on the socio-economic effects of invasive species in riparian environments. He is particularly interested in the effects of water hyacinth invasion in the Jomoro District where the presence of the weeds in the River Tano and Abby-Tano Lagoon poses challenges to riparian people who rely on the two water bodies to make a living. How water hyacinth invasion affects the income and sustainability of farming work in the district is also studied. This study forms part of a larger research that assessed “Biofuel production from lignocellulosic materials” financed by DANIDA Fellowship Centre (2GBIONRG) and coordinated by the Technical University of Denmark.

References

- Adigun, B.T., Baimro, O.M., & Adedeji, I. A. (2015). Explaining poverty and inequality by income sources in rural Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IOSR-JHSS), Volume 20(Issue 3), 61–13. http://iosrjournals.org/iors-jhss/papers/Vol20-issue3/Version-5/K020356170.pdf

- American Economic Association. (1966). The theory of peasant economy. Homewood, Illinois: Richard D. Irwin Inc. Retrieved from https://growthecon.com/assets/papers/alexander_chayanov_the_theory_of_peasant_economy.pdf

- Annang, T. Y. (2012). Composition of the invasive macrophyte community in three river basins in the Okyeman area, Southern Ghana. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 20(3), 69–72.

- Belletti, M. (2015). The emerging role of the peasant economy at the end of the industrial age: Insights from Albania. Procedia Economics and Finance, 33, 78–89. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01695-0

- Bhattacharya, A., & Kumar, P. (2010). Water hyacinth as a potential bio-fuel crop. Electronic Journal of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 9(1), 112–122.

- Borokini, T. I., & Babalola, F. D. (2012). Management of invasive plant species in Nigeria through economic exploitation: Lessons from other countries. Management of Biological Invasions, 3(Issue 1), 45–55. doi:10.3391/mbi

- Dagno, K., Lahlali, R., Diourte, M., & Haissam, J. (2012). Fungi occurring on water hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes [Martius] Solms-Laubach) in Niger River in Mali and their evaluation as mycoherbicides. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management, 50, 25–32.

- De Graft Johnson, K. A. A. (1995). Integrated control of aquatic weeds In Ghana. In R. Charudattan, R. Labrada, T. D. Center, & C. Kelly-Begazo (Eds.), Strategies for water hyacinth control (pp. 28–44). Florida, FL: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations.

- De Graft-Johnson, K. A. A., Blay, J., Nunoo, F. K. E., & Amankwah, C. C. (2010). Biodiversity threats assessment of the Western region of Ghana. The Integrated Coastal and Fisheries Governance (ICFG) Initiative Ghana. Retrieved from http://:www.crc.uri.edu/Biodiversity_Threats_Assessment_Final_505.pdf, .

- Dempsey, C. (2012). Distance decay and its use in GIS. Retrieved from https://www.gislounge.com/distance-decay-and-its-use-in-gis/.

- Djurfeldt, G. (2016). Family and capital farming: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Retrieved from http://portal.research.lu.se/portal/files/1382864/Family_and_capitalist_farming_conceptual_and_historical_perspectives.pdf

- Dreesen, P. E., De Boeck, H. J., & Janssens, I. A. & Nijs, I. (2012). Summer heat and drought extremes trigger unexpected changes in productivity of a temperate annual/biannual plant community. Environ. Exp. Bot., 79, 21–30.

- Enete, A. A., & Onyekuru, A. N. (2011). Challenges of agricultural adaptation to climate change: Empirical evidence from Southeast Nigeria. TROPICULTURA, 29(4), 243–249. http://www.tropicultura.org/text/v29n4/243.pdf

- Evans, S.P., Knezevic, S.Z., Linquist, J.L., & Shapiro, C. A. (2003). Influence of nitrogen and duration of weed interference on corn growth and development. Weed Science, 51, 546–556.

- Fami, H. S., Samiee, A., & Sadati, S. A. (2009). An examination of challenges facing peasant farming system in Iran. World Applied Sciences Journal, 6(9), 1281–1286.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation)/Government Cooperative Programme. (1998). Integrated control of aquatic weeds project: findings and recommendation in ghana. Rome: Author

- Finlayson, C. M., Ntiamoa-Baidu, G. C., Tumbulto, Y., & Storrs, M. (2000). The hydrology of Keta and Songhor Lagoons: Implications for coastal wetland management in Ghana. Supervising Scientist Report 152. Supervising Scientist, Darwin.

- Firehun, Y., Struik, P. C., Lantinga, E. A., & Taye, T. (2014). Water Hyacinth in the rift valley water bodies of Ethiopia: Its distribution, socioeconomic importance and management. International Journal of Current Agricultural Research, 3(5), 67–075.

- Ganle, J. K., Afriye, K., & Segbefia, A. Y. (2015). Microcredit: Empowerment and disempowerment of rural women in Ghana. World Development, 66, 335–345. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.08.027

- Ghana News Agency (2007). Water hyacinth threatens marine life, restricts movements. . Retrieved from http://www.ghananewsagency.org/.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 population and housing census: District analytical report, Jomoro District. Accra, Ghana: Author.

- Hauser, L., Wernand, A., Korangteng, R., Simpeney, N., & Sumani, A. (2014). Water hyacinth in the lower Volta Region: Turning aquatic weeds from problem to sustainable opportunity by fostering local entrepreneurship.

- Hilmi, A., & Burbi, S. (2015). Peasant Farming, a buffer for human societies. Development, 58(2–3), 346–353. doi:10.1057/s41301-016-0035-z

- Iderawumi, A. M. (2018). Characteristics effects of weed on growth performance and yield of maize (zea mays). Biomedical Journal Of Scientific and Technical Research, Vol. 7(3), 7.

- Jafari, N. (2010). Ecological and socio-economic utilization of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes Mart. Solms). Journal of Applied Science and Environmental Management, 14, 43–49.

- Javald, A. (2010). Effect of six problematic weeds on growth and yield of wheat. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 42(4), 2461–2471.

- Jayan, P. R., & Sathyanathan, N. (2012). Aquatic weed classification, environmental effects and the management technologies for its effective control in Kerala, India. International Journal of Agricultural & Biological Engineering, 5(1), 76–91.

- Kamau, A.N., Kinyua, Njogu, P., & Sessay, M. (2015). Sustainability challenges and opportunities of generating biogas from water hyacinth in ndunga village, kenya. Responsible natural resource economy programme issue paper 005/2015. Retrieved from http://www.africaportal.org/documents/14234/Issue_paper_0052015.pdf

- Kateregga, E., & Sterner, T. (2009). Lake Victoria fish stocks and the effects of water hyacinth. The Journal of Environment and Development, 18, 62–78. doi:10.1177/1070496508329467

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Lipiec, J., Doussan, C., Nosalewicz, A., & Kondracka, K. (2013). Effect of drought and heat stresses on plant growth and yield: a review. International Agrophysics, 27, 463–477.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. (2015). The composite budget of the Jomoro District Assembly for the 2014 fiscal year. Accra, Ghana: Author.

- Mumin, A. A., Gyasi, R. M., Segbefia, Y. A., Forkuor, D., & Ganle, J. K. (2018). Internalised and social experiences of HIV induced stigma and discrimination in urban Ghana. Global Social Welfare : Research, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 1–13. doi:10.1007/s40609-018-0111-2

- Navarro, L., & Phiri, G. (2000). Water hyacinth in Africa and the Middle East: A survey of problems and solutions. Retrieved from http://www.idrc.ca/sites/default/files/openebooks/933-x/index_html

- Ndimele, P. E., Kumolu – Johnson, C. A., & Anetakhai, M. A. (2011). The Invasive macrophyte, water hyacinth {Eichhornia crassipes (Mart) Solm – Laubach: Pontedericeae}: Problems and prospects. Research Journal of Environmental Sciences, 5, 509–520. doi:10.3923/rjes.2011.509.520

- Ogulande, Y. (2002). Impact of water hyacinth on socio-economic activities: Ondo State as a case study. Retrieved from http://aquaticcommons.org/953/1/WH_175-183.pdf

- Omondi, Gichuki, J., Boera, R., Okorut, P., Matano, T., Jembe, A., & Ofulla, A. (2012). Water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes (Mart) Solms-Laubach dynamics and succession in the Nyanza Gulf of Lake Victoria (East Africa): Implications for water quality and biodiversity conservation. The Scientific World Journal, Volume 2012, 1–11. doi:10.1100/2012/106429

- Onyango, J.P., & Ondeng, M.A. (2015). The contribution of the multiple usage of water hyacinth on the economic development of riparian communities in dunga and kichinjio of kisumu central sub county, kenya. American Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, Vol 1(No. 3), 3.

- Patel, S. (2012). Threats, management and envisaged utilizations of aquatic weed Eichhornia Crassipes: An overview. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology, 11(3), 249–259. doi:10.1007/s11157-012-9289-4

- Ploeg, J. (2008). The new peasantries: Struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of globalization and empire. London: Earthscan.

- Ploeg, J. (2017). The importance of peasant agriculture: A neglected truth. Farewell address upon retiring as Professor of Transition Processes in Europe at Wageningen University & Research. Retrieved from edepot.wur.nl/403213.

- Rantso, T. A. (2016). The role of the non-farm sector in rural development in lesotho. J. of Modern African Studies, 54(2), 317–338.

- Ray, P., & Hill, M. P. (2013). Microbial agents for control of aquatic weeds and their role in integrated management. CAB Reviews, 8(014), 1–9. doi:10.1079/PAVSNNR20138014

- Rollins, J. A., Habte, E., Templer, S. E., Colby, T., & Schmidt, J., & von Korff, M. (2013). Leaf proteome alterations in the context of physiological and morphological responses to drought and heat stresses in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). J. Exp. Botany, 64(11), 3201–3212

- Samberg, L. H., Gerber, J. S., Ramankutty, N., Herrero, M., & West, P. C. (2016). Subnational distribution of average farm size and smallholder contributions to global food production. Environmental Research Letters, 11, 124010. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/124010

- Shalaby, M. Y., Al-Zahrani, K. H., Baig, M. B., Straquadine, G. S., & Aldosari, F. (2011). Threats and challenges to sustainable agriculture and rural development in Egypt: Implications for agricultural extension. The Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 21(3), 581-588.

- Shanab, S. M. M., Shalaby, E. A., Lightfoot, D. A., & El-Shemy, H. A. (2010). Allelopathic effects of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes). PloS one, 5(10), e13200. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013200

- Spoor, M. (2015). Rural development and the future of small-scale family farms. Rural transformations - Technical papers series #3. Retrieved from www.fao.org/3/a-i5153e.pdf.

- Teodor, S. (1986). Russia in the 1920s: Chayanov’s “Theory of Peasant Economy” and its place in the contemporary intellectual history. Retrieved from https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article40122

- Thuo, A.D.M. (2010). Community and social responses to land use transformations in the nairobi rural-urban Fringe, Kenya, Field Actions Science Reports Special Issue 1-Urban Agriculture. Retrieved from http://factsreports.revues.org/index435.html

- Torero, M. (2011). A framework for linking small farmers to markets’. Paper presented at the IFAD Conference on New Directions for Smallholder Agriculture, 24–25. Retrieved from http://www.ifad.org/events/agriculture/doc/papers/torero.pdf.

- Waithaka, E. (2013). Impacts of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) on the fishing communities of Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Journal of Biodiversity and Endangered Species Issue, 2(1), 108. doi:10.4172/2332–2543.1000108

- Water Resources Commission. (2012). Tano River basin-integrated water resources management plan. Accra: Author.

- Wortman, S. E., & Lovell, S. T. (2013). Environmental challenges threatening the growth of urban agriculture in the united states. Journal of Environmental Quality, 42(5), 1283–94. doi:10.2134/jeq.2013.01.0031

- Zhang Y., Zhang, D., & Barret, S. (2010). Genetic uniformity characterises the invasive spread of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), a clonal aquatic plant. Molecular Ecology, 19, 1774–1786.

- Zidana, A., Kaunda, E., Phiri, A., Khalil-Eldris, A., Matiya, G., & Jamu, D. (2007). Factors influencing cultivation of the Lilongwe and Linthipe River Banks in Malawi: A case study of Salima Disrict. Journal of Applied Sciences, 7(21), 3334–3335. doi:10.3923/jas.2007.3334.3337