Abstract

Urban farmers remain vulnerable and trapped in poverty due to urbanisation and food crop and input price volatility. However, studies on the causes and effects as well as coping strategies to the phenomena remain inconclusive amidst diminishing urban farmlands, as the focus has been on smallholders in rural areas. This paper examines the attitudes of urban farmers on the strategies adopted to cope with input and crop price fluctuations in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipality, Ghana. Data obtained from 380 respondents showed that four major factors influence the volatility of input prices: oil prices, exchange rates, cocoa producer prices and inflation. Farmers, however, had no coping strategies to these due to the limited control over them. Two key factors were noted to influence crop price fluctuation: natural and demand and supply factors. Farmers coped with food crop price fluctuations by: adding value to crops; farming in flood plains; diversifying income sources and shifting to cocoa cultivation. A shift to cocoa production and farming in flood plains was however revealed to have adverse environmental and ecological implications. The paper recommends the promotion of contractual farming to safeguard farmers against income falls; and the formulation of an environmental strategy which emphasises drought-resistant crop varieties with shorter gestation periods as well as promoting sustainable land and water management practices.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

We examined how urban smallholder farmers in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipality of Ghana are vulnerable to price changes (in terms of inputs and crops), and how they are able to cope with the changes. Our research has indicated that due to external nature of factors leading to changes in inputs’ prices; the vulnerable farmers were unable to put in place coping measures for that. But for changes in the prices of crops, the farmers cope through value addition, expansion of farmlands to flood plains, income diversification and a gradual shift to cocoa farming. Expansion of farming activities to flood plains comes with environmental consequences. Having observed the situation, we propose contractual farming, a formulation of environmental strategy and promotion of sustainable land and water management practices for the farmers to help concretise the coping mechanisms for positive outcomes.

Competing Interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Over the years, the rapid rate of urbanisation across the globe is increasingly threatening urban farming. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the situation is more intense, as urbanisation remains largely spontaneous and unplanned leading to the rise in urban slums (Potts, Citation2009; Satterthwaite, McGranahan, & Tacoli, Citation2010). Whilst this situation is depleting urban farming, it has also made urban communities more susceptible to floods due to climate change. Obviously, interventions are needed to promote urban farming, prominent amongst them is green infrastructure as an adaptation strategy to climate change. Green infrastructure is incrementally gaining popularity in the policy space as divergent development professionals and practitioners have recognised it as a way-out for concretising the resilience of the urban environment to the challenges of rapid population growth, climate change, biodiversity loss, energy, food and water security (see Pitman, Daniels, & Ely, Citation2015). In fact, there are evidences of the impacts of green infrastructure across the globe (for instance, in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso; Rosario in Argentina; Dumangas in Philippines; and New York in USA) through measurements of its effectiveness (see Bowler, Buyung-Ali, Knight, & Pullin, Citation2010; Natural England, Citation2013), and these have generally drawn a significant positive correlation between the implementation of green infrastructure, urban climates and the well-being of urban communities. Urban farming can thus, be promoted as green infrastructure, particularly in the Sub-Saharan region of Africa.

This is very urgent and necessary as urbanisation has undeniably, altered the urban environment and its functionality across the region. However, Davy (Citation2009) indicates that outcomes of such deliberate intervention depend on its management. In that, owing to the “supposed” expertise and knowledge of authorities on urban dynamics and their claim to protect the public interest(s); they influence land use planning, policies and designs to ensure socio-economic development. Past experiences have commonly revealed that interventions on urban policy, particularly in the developing regions, turned to have excluded issues on urban farming. As a result, urban farmlands in many countries have quickly diminished/reduced (Cohen & Garrett, Citation2009; Kerrey, Citation2012), despite the awakening food security concerns. Urbanisation should, however, not be an excuse for the reduction of urban farmlands of developing countries (including Sub-Saharan Africa), especially in the current phase where urban green infrastructure has presented itself as a novel adaptation intervention. In fact, cities in the developed countries which have subscribed to the provision and management of urban farmlands have experienced higher levels of urbanisation over the past 50 years vis-à-vis the experiences of the developing countries (Fox, Citation2012).

Farming is a major source of income and livelihood to many poor households in the global south, where it provides about 80% of food in most developing countries (Arias, Hallam, Krivonos, & Morrison, Citation2013). The Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO, Citation2011) thus asserts that growth in farming is important in ensuring food security. The critical roles of farming, therefore, underpins economic growth, poverty alleviation and reduction and sustainability of livelihoods (Byerlee, Janvry, & Sadoulet, Citation2010; Diao, Hazell, Resnick, & Thurlow, Citation2006). Notwithstanding these, farmers are among the world’s most disadvantaged and poor people (Altieri & Koohafkan, Citation2008) and yet is expected to pave way to ending poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa (Chomitz, Buys, de Luca, & Wertz-Kanounnikoff, Citation2007). Afenyo (Citation2008) however argues that it appears that efforts by governments and the development community to support (urban) farming in Sub-Saharan Africa are not yielding significant results.

Antonaci, Demeke, and Vezzani (Citation2014) indicate that farmers are exposed to several risks which affect them as both producers and consumers of food. These include climate variability, limited assets and investments, pest and disease infestations and price volatility which result in lower productivity (Kahan, Citation2013). Price fluctuations in agricultural inputs and outputs, in particular, are among the major risks that farmers have limited control over, mostly caused by variation in demand and supply (FAO et al., Citation2011). On this, Cantore (Citation2012) posits that farmers’ (specifically, smallholders) livelihoods are threatened over uncertainties in inputs and output prices, and this discourages farmers’ efforts to innovate and expand to reap benefits.

In most Sub-Saharan African countries, smallholder farmers, in particular, were exposed to extreme volatility in agricultural prices following the implementation of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the 1980s which abolished direct state involvement in agricultural markets (Ferris et al., Citation2014). The International Finance Corporation (Citation2013) further notes that the implementation of SAP led to the weakening of extension services which reduced farmers’ capacities and access to affordable inputs and lucrative commodity markets. Likewise, Arias et al. (Citation2013) state that SAP reduced productivity, as it constrained their ability to participate in well-integrated markets where prices are most favourable to expand activities. As a result, farmers were left to operate in poorly functioning informal markets where prices were most volatile.

Further, extreme price volatility for major food commodities and inputs which occurred between 2006 and 2008 impacted greatly on domestic markets of various countries and raised concerns of food insecurity. According to Barker et al. (Citation2008), about 75 million people had limited access to food due to high inputs and food prices within that period. Similarly, Hoyos and Medvedev (Citation2009) showed that about 155 million people became poor within the same era. Yet, the FAO (Citation2011) posits that periods of higher volatility in the prices of agricultural inputs and outputs still await in the future, given the ever-growing demand for food, biofuels and climate change, mostly due to urbanisation and population growth. The case of Sub-Saharan Africa is more critical, where the region experiences about 3% annual decline in per capita food production since 1990 (Khan et al., Citation2014), further raising price concerns.

Although the aim to end poverty and starvation dominates current global conventions, specifically, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the challenge is that most farmers who are at the heart of the aim to promote food security are extremely affected by price fluctuations which discourage their efforts. In the light of the global recommitments to agriculture, calls are being made wherever possible to invest in agriculture. Different results cannot, however, be expected if the same strategies are used. Unfortunately, most developing countries have had it difficult to insulate poor farmers from volatile prices (Donye & Ani, Citation2012; FAO et. al., Citation2011). In addition, recent agricultural policies appear to decouple production and agricultural prices leave farmers with no solid control over volatility in prices (Demeke, Kiermeier, Sow, & Antonaci, Citation2016). It, however, remains unclear how urban farmers, in particular, respond to/cope with this phenomenon in the global south amidst increasing urbanisation and associated challenges on urban farming.

In Ghana, increasing urbanisation has exerted immense pressure on the urban landscape leading to the reduction in farmlands, yield and prices. Wodon, Tsimpo, and Coulombe (Citation2008) show that food prices in Ghana for rice, maize and other cereals, in particular, increased by 20% to 30% between 2007 and 2008 which raised concerns about future prices of food and its impact on food security. Amanor‐Boadu (Citation2012) further showed that Ghana’s maize market did not escape the commodity price crisis that engulfed global commodity markets in the 2007 to 2010 period. The price range in the 2007/08 crop year, for example, was GH¢35.35Footnote1 (US¢8.02) per 100 kg compared to GH¢12.51 (US¢2.84) in the previous crop year and GH¢17.91 (US¢4.07) two crop years later. The turbulent year (2007/08) also posted the highest variability in market prices, with a standard deviation of GH¢11.76 (US¢2.67) and a coefficient of variation of 32.6%, the highest estimated in the last five crop years. Indeed, the variability in prices in all other crop years was in the single digit. Despite this low-price variability within each crop year, what was observed was that the mean price over the crop year has been trending upwards.

The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (Citation2014) indicates that approximately 47% of household expenditure is spent on food in Ghana. In relation to this, the FAO (Citation2011) argues that households who spend substantive part of their income on food often result in less nutritious food and sometimes shift spending away from education and health to supplement their food expenses under the influence of higher prices. It is, therefore, necessary for the management of food prices as it often induces inappropriate household behaviour. The FAO (Citation2011) also showed that about 240 million people in Africa became undernourished and lacked dietary diversification due to unstable prices of staples such as maize, cassava, rice, wheat, and plantain. Inferentially, as households in Ghana have similar staples, the unstable prices of these staples tend to have similar impacts. A study by Rapsomanikis and Sarris (Citation2008) also found that the income of households engaged in both cash and food crops were subject to significant fluctuations. These findings were obtained during a period when farmers in Ghana had adopted crop diversification strategies to mitigate the impacts of unstable prices. However, till date, little empirical findings exist on how urban farmers cope with these unstable prices.

Considering that fluctuations in prices affect all farmers, coupled with the fact that urbanisation has resulted in diminishing land sizes for urban farming/agriculture, urban farmers could be worse affected. Equally, of essence is that the sustainability of urban farming and the aim of ensuring food security as a whole is dependent on farmers’ ability to insulate themselves from the effects of price fluctuations. Additionally, farmers’ ability to escape poverty traps and ensure profitability of agriculture is highly determined by the extent to which they are able to cope with price shocks. With this, the aim of this study is to examine the perception of urban farmers on the causes, effects and indigenous coping strategies to the fluctuations in prices of inputs and food crops. Even though we know that environmental parameters associated with urban farming influence farmers’ vulnerability, the focus of our study is tacitly on price fluctuations and their influence on farmers’ vulnerability and subsequent coping mechanisms in that respect. We have paid attention to price fluctuations vis-à-vis farmers’ vulnerability in order to throw more light in that direction which has received very fragile focus in Ghana and the Sub-Saharan African region at large.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

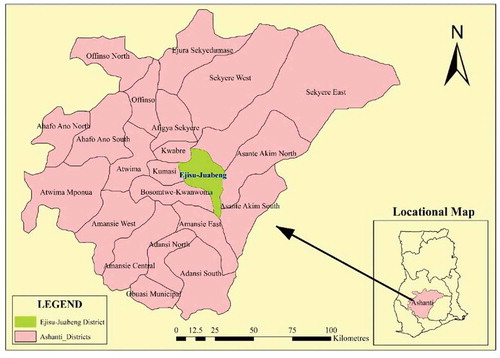

The study was undertaken in the Ejisu-Juaben Municipality in Ghana, occupying a land area of about 637km2. It is located at the central part of the Ashanti Region (Figure ) with Ejisu as its capital. The municipality lies on Latitudes 1° 15ʹN and 1° 45ʹN and Longitude 6° 15ʹW and 7° 00 W. It shares boundaries with six other districts: Sekyere East and Afigya Kwabre to the Northeast and Northwest, respectively; the Bosomtwe and Asante Akim South Districts to the South; the Asante Akim North to the East (all major agricultural districts) and the Kumasi Metropolis to the West. The Municipality has a relatively high population density of about 244km2 (as against 195 km2 in 2010 that made it rank sixth in the Region). This is because it has become a “dormitory” of the Kumasi Metropolis (which hosts the regional capital, Kumasi, the second major city in Ghana) as large number of people live in the Municipality but commute to Kumasi to work.

The Municipality had about 84 settlements out of which five were classified urban settlements in the year 2000. The five towns accounted for 30% of the total population. Over the last decade, however, the area has experienced increasing urbanisation, a phenomenon that has changed the typical rural District into a fast-growing peri-urban area. The current rural/urban divide is estimated at 52%:48%; and growing exponentially both in terms of spatial extent, economic activities and demography.

Even though the local economy is mainly agrarian, the share of urban agriculture is fast reducing owing to urbanisation and increasing land values for other land uses. Available data show rapid changes in land uses, where some land uses (particularly agriculture) are giving space to others (agricultural lands, in particular, have reduced by over 11% in the past five years (see Ejisu-Juaben Municipal Assembly (EJMA), Citation2014)). The urban share of agriculture has thus, reduced significantly over the last decade by 29%. As a result of the effects of the sprawl and population growth, the urban fabric and natural environment have been greatly altered. This situation has pushed many farmers away from using urban lands due to competition for space. Many of the farmers are therefore small-holder farmers (nearly 95% of them) (see EJMA, Citation2014).

The two main types of agriculture practices are crop farming (food and cash crops farming) and animal husbandry. The cash crop engaged in by farmers is cocoa since the crop strives well in the municipality. Again, since the price of cocoa is determined by government based on prevailing world market conditions, farmers are less vulnerable to price shocks compare to other crops. In cases where the price ceiling is not all that commensurate, farmers are able to exert pressure on government in succeeding years to set price a bit higher for gainful outcomes of their labour (see Kolavalli & Vigneri, Citation2011). The areas of land for cocoa production are predominantly between 10 and 20 acres; the small areas utilised have been influenced by the persistent rise in urbanisation which seems to be discordant to farming practices. Majority of farmers (more than 90%) are noted to be food crop farmers (EJMA, Citation2014). While about 87% engage agriculture full time or as part-time have their farms located within the Municipality, about 13% of farmers have their farms located outside the Municipal Area, due to increasing urban land rents.

Access to credit to buy agricultural inputs, pay for farm labour and to expand farms are also not only difficult to come by but are also very expensive if it is available (EJMA, Citation2014). The result is that most farmers are unable to maintain their farms well and this culminates in poor yields. The resultant effect has been instability in the share of urban lands for agriculture which has a potential effect on volatility in food crop and input prices which has several implications on farming households.

2.2. Research approach and data collection

2.2.1. Approach

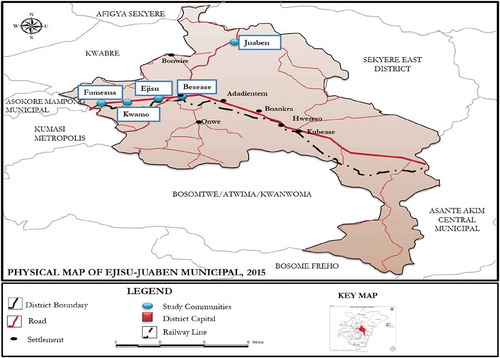

The current study adopts the cross-sectional methodology to address the research objectives. The survey approach was used to identify the small-holder urban farming households in the Municipality, and gather data on the causes and effects of food crop and input price fluctuations as well as strategies to cope with the phenomena. The study population comprised urban farming households in five purposively sampled major agricultural urban communities in the Municipality: Ejisu, Juaben, Kwamo, Fumesua and Besease (see Figure ). These towns form the major urban agricultural producing areas for food crops within the Municipality.

A sample of 370 farming households out of a total population of 9,427 households was used for the study at 95% confidence level and 5% error margin (white term). The sample size was proportionally distributed across the five communities (See Table ). The sample size was determined using the formula; n = N/1 + N (α)2 (see Miller & Brewer, Citation2003) where n is the sample size for the study population; N is the sample frame while α is the white term (α is the 5% white term). By computation, an “n” value (sample size) of 384 was determined, however, during the field survey, 370 farming households were available and qualified for interviews. This accounted for a completion rate of approximately 96%. The purposive and convenience sampling techniques were adopted to select and interview participants at the household level. This is because data was obtained from farming households based on their availability (convenience) and involvement in urban farming (purposive) in the study communities. Because the focus of the study was on crop farming in the Ejisu Municipality, urban farmers were selected based on the condition that they were engaged in crop farming (either full time or part time) in the urban areas of the municipality. With this, farming households that lived in the five selected urban communities but engaged in farming either in the rural areas of the municipality or in areas (both urban and rural) outside the geographical scope of the study were automatically excluded. The units of inquiry were heads of the sampled farming households. In the absence of the head, the next of kin was interviewed for the relevant data.

Table 1. Sampled farming households within the selected towns

2.2.2. Data collection tools and process

Semi-structured questionnaires, interview guides and observational checklists were used to elicit the required responses from respondents. The semi-structured questionnaire was used to obtain information from farming households through face-to-face interviews. It covered issues on the perception of the causes and effects of unstable input and food crop prices and the adopted coping strategies to the phenomenon and how effective the strategies have been.

Data collected from the primary respondents were triangulated with those obtained from heads of relevant institutions identified in the study area to render the findings more accurate and valid and superior to mono-method. The relevant departments/institutions interviewed were the Municipal Agricultural Development Unit (MADU) and the Municipal Planning Office/Unit. A total of 10 officials were purposively selected due to the mandated roles they are expected to play in developing the agricultural sector. In all, data was collected from 380 respondents made up of both households and local government officials at the municipality.

Additionally, focus group discussions (FGDs) were held to have a better understanding of the issues raised by farmers, particularly on the causes of price fluctuation, the coping strategies and their effectiveness in the Municipality. The average number of participants of the FGDs was eight, based on the work of Manoranjitham and Jacob (Citation2007) who argued that the optimal number of participants for focus group discussion should range between eight and ten. Five (5) FGDs were held for the farmers engaged in the study, with one (1) conducted in each of the five selected study communities that were part of the study sample.

Informed consent was first sought from participants. The rationale and need for the study, procedures involved rights of participants, confidentiality, voluntary participation and the right to dissociate at any time of the study without prejudice; were well explained to participants.

The primary data collection was undertaken between the 8th and 20th of August 2016. Subsequent follow-ups were undertaken to obtain additional data from the institutions and workers to render the findings more complete and accurate. The interviews were conducted at conducive settings with the assistance of two expert interviewers. The interviews were conducted in Twi,Footnote2 since all respondents were fluent in the language.

2.3. Analytical methods

The causes of fluctuation in input and food crop prices were obtained from both secondary and primary sources. A list of possible causes was generated under the two major themes (inputs and food crops). The results were analysed quantitatively (with the help of Microsoft Excel) by determining the proportion of farmers who attributed to specific causes under the two headings. The results were presented in simple frequencies and percentages. Where necessary, quotations (qualitative) were used to support the assertions made by respondents.

We further examined the coping strategies adopted by respondents to input and crop price fluctuation by asking farmers to list them. Based on the list, farmers were asked to indicate the effectiveness of the strategies by way of an ordinal scale, i.e. on a three-point Likert scale: 3—effective; 2—indifferent; 1—ineffective. Respondents were further asked to explain the reason for an assigned point to a given factor. Microsoft Excel was then used to generate the mean, standard deviation (S.D.) and co-efficient of variation to explain the responses given by the respondents. The coefficient of variation (C.V.) was used to measure the ratio of the standard deviation (S.D.) to the mean. By inference, distributions with a coefficient of variation to be less than 1 were considered to be of low-variance, whereas those higher than 1 were considered to be of high variance. Whilst quantitative data was generated and analysed through the help of Microsoft Excel, qualitative data (such as FGD data) was analysed manually based on themes to support the quantitative findings. All quotations in the research were directly transcribed from Twi to English after the field survey and grammatically arranged for analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Background of respondents

Agriculture in Africa and particularly Ghana is male-dominated. Similarly, the study showed that approximately 62% and 38% of the respondents were males and females, respectively. Investigation on the crop types produced by the smallholder farmers showed that about 38% cultivated cereals (specifically, maize), 33% in tuber crops, mainly cassava, plantain and cocoyam. About 17% and 12% cultivated cocoa and vegetables (specifically, pepper and garden eggs), respectively (see Table ). Approximately 23% of the farmers also kept livestock, although was not a major activity/practice. Female farmers were mainly into the production of vegetables (approximately 73%). The female dominance in vegetable was because vegetable farming was “easier” to cultivate and also lucrative when the product is marketed at the municipal market and in Kumasi. This is further explained by scholars who argue for the integration of female farmers into such markets (Bijman et al., Citation2007; International Finance Corporation, Citation2013). The survey further revealed that all respondents had attained some level of formal education (see Table ).

Table 2. Basic characteristics of respondents

Although most farmers (63%) had their farmlands within the urban areas, increasing urbanisation and sprawl have had an adverse impact on land sizes for agricultural activities, which have consequently affected production and earnings. This was confirmed by respondents where they have been approached by several developers to purchase portions of their lands for physical developments; mainly for commercial and residential purposes. Additionally, about 81% farmed for commercial purposes, indicating the significance of urban farming as a major source of livelihood. Discussions with the MADU revealed that the Municipality until recently, had vibrant urban agricultural system, where most urban households were engaged in various agricultural activities, either on commercial basis or subsistence (secondary occupation). Hence, the need to revitalise urban agriculture by investing in improved seed varieties and inputs to improve productivity, due to the rapid decline of urban farmlands.

Farmers purchased and used various agricultural inputs including fertilisers, farm implements, seedlings, agro-chemicals and hired labour. This buttresses arguments where concerns about food insecurity have been about price volatility in both academic and policy discourse (Barker et al., Citation2008; Cantore, Citation2012; Gilbert & Morgan, Citation2010). The FAO (Citation2011) notes that growing demand for food due to population growth, biofuel for energy and weather shocks, among others, primarily cause prices of agricultural inputs and food to be volatile due to distortion created in demand and supply for them. As a result, ineffective strategies to cope with such trends would adversely affect general wellbeing of farming households.

3.2. Farmers’ perceptions about the causes of input price fluctuations

Interview with farmers revealed four distinct factors that cause fluctuations in input prices; oil (petroleum) prices (indicated by 35% of the respondents), cocoa producer prices (11%), exchange rates (29%) and variability in the local currency (inflation) (25%). Specifically, the finding on inflation corroborates a similar finding by Cantore (Citation2012) who reported on fluctuating local currency as a major cause of input price fluctuations. Contrary to other studies where factors such as: unpredictable variations in supply and demand variables operating in agricultural markets (Gilbert &Morgan, Citation2010); rising incomes and demand for food and feed crops for biofuel production (Barker et al., Citation2008); were reported as major causes of input price fluctuations, this study found otherwise.

Approximately77% of the respondents reported that there were always upsurge variations in input prices rather than a decrease, which they argued had adverse implications on yield and productivity. This is however contrary to Demeke et al. (Citation2016) assertion that farmers (specifically, smallholders) in Africa irrespective of exposure to high input prices, produce lower outputs and have low productivities. The study further gathered that farmers were confronted with a persistent increase in input prices as a result of retailers who operate as monopolies in the input marketing channel in the study communities. Farmers faced with such a phenomenon remarked that:

Prices of farm inputs increase all the time due to retailers who have no competitors. They sell at high prices which make it difficult to buy more, but we have no option than to buy considering the municipal market is farther away.

This was confirmed through discussions with the MADU where agricultural input sellers took undue advantage of farmers by raising prices of inputs whenever there were cases of high inflation and/or high fuel prices and did not lower prices of inputs when there are reductions due to the assertion that;

…. the world is advancing and prices do not come down but rather go up or remain as they are....

Efforts by MADU to regulate input prices were largely ineffective as they were unable to regularly monitor sellers of farm inputs. The study showed that farmers who frequently purchased inputs such as seedlings and agro-chemicals mentioned changes in fuel prices as the main cause of input price fluctuations. A discussant during an FGD at Fumesua stated:

We are living at a time and in a country where fuel prices increase consistently. These inputs (seedlings and agrochemicals) are frequently purchased at every point especially during the planting and maintenance of the farm and as such changes in fuel prices affect its prices due to their transportation and production cost.

This finding is further explained by the widely accepted claim that oil prices drive the prices of commodities on both international and domestic markets (FAO, Citation2011). In a similar vein, inflation was reported by farmers as a major factor causing increases in input prices, where they stated that there was a persistent reduction in the purchasing value of the local currency or real income, and as such, the price of inputs increased with time.

Additionally, respondents who mentioned “exchange rates” as the cause of volatility in input prices asserted that such variations occurred due to differences in currencies used to trade on the international market, which was a macroeconomic phenomenon where they (farmers) had no control over. Again, due to the frequent depreciation of the local currency, farmers indicated that input prices become volatile when the local currency depreciate against the currency (notably the US dollar) on the international market. The argument by Hail et. al. (Citation2016) that international market prices of farm inputs drive domestic agricultural inputs’ price volatility holds true for this study. This had adverse effects on the “vulnerable” urban farmers. The foregoing suggests the extent of knowledge of urban farmers about trends in the global agricultural market, which is contrary to studies that farmers in developing countries, specifically, sub-Saharan Africa know little or nothing about practices and regulations regarding the sector (Groot & Van’t Hoof, Citation2016; Lunner-Kolstrup & Ssali, Citation2016; Rother, Citation2008), which further exacerbates their poverty situation.

Lastly, cocoa producer price as a cause of input price fluctuations was revealed to be largely tied to hire labour costs. It was revealed during all FGDs (by farmers who cultivate cocoa) that the cost of hired labour per acre of land was charged based on the price at which a bag of cocoa was sold (at GH¢200). However, due to fixed and stable price ceiling for cocoa by the government, volatility in labour costs was less experienced. Farmers further indicated a level of unidirectional relationship between cocoa producer price and price of farm implements. Prices of agricultural inputs/implements increased whenever cocoa producer prices increase but not vice versa. This was confirmed by the MADU and during an FGD at Ejisu:

over the past two years, the prices of all farm implements, irrespective of what crop you grow, increases whenever the government increase producer prices of cocoa. Sellers of the farm implements, most times, are of the view that because cocoa prices have gone up, farmers will get enough money and so they (sellers) should increase price of implements since they cannot be done away with

The foregoing shows farmers are often exploited and thus remain trapped in poverty and food insecurity. This is further explained by Diaz-Bonilla (Citation2016) that farmers’ profits (incentives to produce) and purchasing decisions and economic access to food are largely affected by price levels and its variability. On this, Huka, Ruoja, and Mchopa (Citation2014) suggest that high inputs costs have limited farmers’ ability to produce on large scale to gain higher profits in most Sub-Saharan African countries, specifically, urban areas. The FAO (Citation2011) finds this a threat to food security and livelihood.

3.3. Perception on causes of food crop price fluctuations

Demeke et al. (Citation2016) maintain that prices of agricultural products underline the survival of farmers. The prices obtained by farmers for their produce determine the profitability of agriculture and future investment decision towards food production. In this regard, fluctuations in the price of food crops result in indecision by farmers to invest in farming as they face high levels of uncertainty. For this reason, the study sets out to inquire from farmers the factors which result in fluctuations in the prices of food crops they cultivated.

It was identified that food crop price fluctuations were influenced by two key factors: natural (climate variability and seasonal nature of production); as well as demand and supply factors (specifically, the nature of crops grown and the lack of storage facility and technology). Farmers identified erratic rainfall pattern and long periods of drought, as prevailing climate variability risks result in price fluctuations. Farmers had no access to irrigable lands due to the unavailability of irrigation infrastructure and decreasing supply of urban farmlands.

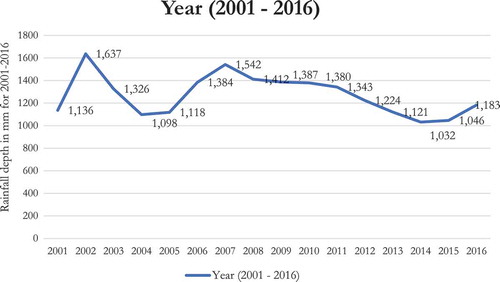

About 10% of the farmers indicated that climate variability was a major cause of price fluctuations, where changes in climatic conditions contributed much to determining the amount of harvest. Respondents explained that their farming activities were mainly rain-fed; as such, whenever the rains “delayed”, it adversely affected planting time as well as the quality and volume of harvest. Data on rainfall amount indicate that the rainfall pattern generally in Ghana is characterised by irregularity and therefore validate the interviewees’ observations. The rainfall pattern in the Municipality is similarly characterised by irregularity and variability in terms of timing of onset, duration and total amount. The limitation of the study was the lack of rainfall data for the Municipality. We, however, used rainfall data (in terms of volume and variability between 2001 and 2016) covering the entire Ashanti Region as a proxy to explain the rainfall pattern in the Municipality (see Figure ). The data showed that the rainfall pattern in the Ashanti Region has been erratic, where the Meteorological Service Department revealed that the rainfall volume for the Ashanti Region had declined by approximately 9% over the last decade.

Figure 3. Rainfall depth in mm (2001–2016) for Ashanti Region, Ghana.

Source: Meteorological Service Department, 2016.

Further investigation revealed that farmers mostly planted in the season when they were expectant of the rains. Farmers, however, asserted that:

We were caught by surprise last two years when we planted but the rains delayed. It greatly affected our output and revenue for that year because we had to hire extra hands and chemicals on the farm to keep the plants until the rains set in.

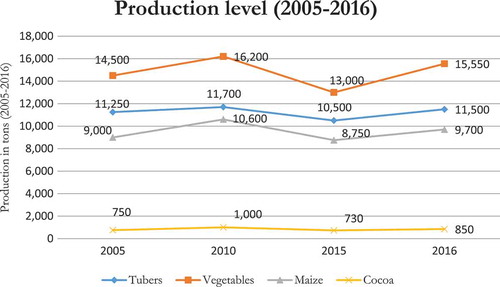

Data from MADU similarly showed variability/decrease in agricultural supply/yield due to unpredictability in rainfall (see Figure ).Footnote3 Hence, the difference in demand and supply for the crops at a time results in fluctuations in prices of crops. Furthermore, the drought period in the Municipality was revealed to peak in the months of November and December, which not only delay the planting seasons but also affect crop yield (about 41% reduction in yield), pricing and income (about 63% reduction in household income). These have implications for food security at the household levels. Although the adverse effects of climate variability on smallholder farmers have been extensively documented in available literature (Challinor, Wheeler, Garforth, Craufurd, & Kassam, Citation2007; Collier, Conway, & Venables, Citation2008; Cooper et al., Citation2008), its effect on food prices was revealed to be dire on urban farming households.

Figure 4. Production in tons (2005–2016) for Ashanti Region, Ghana.

Source: Municipal Agricultural Development Unit (MADU), 2016 (Modified).

Seasonal production was further pointed out by farmers (36%) as a cause of fluctuation in crop prices. We observed that farmers responded to the higher price of food crops by cultivating more of it in an attempt to earn higher incomes from sales. However, due to the seasonality in production, such mass production resulted in excess supply over demand at a time, a phenomenon well explained by classical economists. The MADU further indicated that the Municipality experiences excessive supply of root and tuber crops mostly between June and August, as well as vegetables and cereals (mainly maize) due to the seasonal nature of the crops. This results in fluctuations in crop prices. It was thus observed that prices changed along with the seasonal production of a particular crop since mass production drives prices lower, and the lean season causes prices to rise (Huka et al., Citation2014).

Furthermore, about 28% of the respondents remarked that the nature of the crop grown/produced was another cause of price fluctuations. Farmers mentioned that crop perishability drives the rise and fall of food crop prices over time. It was established that perishability of some crops especially tuber crops and vegetables coupled with the unavailability of better storage facilities and technology make it difficult to store during bumper harvest. Hence, farmers, therefore, become price takers as they are compelled to sell them off even when prices are low in order to avoid post-harvest losses. This according to Mwambi, Oduol, Mshenga, and Saidi (Citation2014) explains why most farmers often struggle to reap returns from their investments due to their limited access to improved facilities, technology and assets.

The foregoing indicates that similar to smallholder farmers in rural communities, urban farmers are confronted with intense challenges during price fluctuations especially when prices of produce drop on the market. FAO (Citation2011), observes smallholder farmers are reluctant to invest to raise productivity due to unpredictability in price changes. Davis (Citation2011) submits that price fluctuations deter smallholders from investing to increase productivity and production.

3.4. Effects of inputs and food crop price fluctuations on farmers

Price fluctuations have severe effects on farmers either as producers or net food buyers. In this regard, the study identified that inputs and food crop price fluctuation affect farmers in varied ways. All farmers indicated that inputs and food crop price fluctuations limit their adoption of modernised methods of farming as they could not afford to buy additional implements/inputs to specifically control pest and disease infestations. Farmers who cultivated fruit and tuber crops further pointed out that price fluctuations limit their ability to purchase improved inputs to use on farms. Maize farmers, in particular, disclosed that the cost of improved maize seedlings was highly expensive and considering that it cannot be re-planted, cause them to use “local” seeds which however have lower yield returns and cannot withstand pest and disease infestations. Additionally, farmers remarked that fertiliser prices were the most volatile and hence limit their ability to purchase and use on farms. It is on this basis that most farmers have lower harvests and are less competitive, indicated by the MADU and discussants during an FGD at Fumesua.

Secondly, it was observed that input and crop price fluctuations resulted in the fall of household incomes. Approximately 76% of the farmers stated that fluctuations (particularly a fall) in food crop prices on the agricultural markets resulted in drastic reduction in household income (about 63% lower), especially among cassava farmers due to the low demand for the crop. It was further observed that most cassava farmers sold produce at the farm gate where prices are mostly low due to the operation of middlemen. Bäckman and Sumelius (Citation2009) in explaining this posit that farmers face income losses whenever agricultural supply exceeds demand. The study confirms this finding as cassava and maize farmers reported most to income reductions as the main effects of price fluctuations. For this reason, most urban farmers also remain trapped in poverty.

Lastly, the study identified that farmers do not prefer to engage in large-scale commercial food crop production due to frequent decline in their prices. Farmers thus, stated that frequent decline in crop prices was a disincentive to engage in large-scale production due to risks of losing investments. Thus, farmers have become risk-averse and reluctant to invest in farming opportunities which could bring higher incomes. Supporting Fafchamps’ (Citation2009) claim that farmers’ fear to innovate and expand their farms cause them to remain subsistent and poor. All farmers expressed intentions to move into cocoa production due to the annual producer purchasing price ceiling and other incentives (free spraying and fertiliser) provided by the government. The study identified that about 60% of the sampled farmers have reduced land area for food crops to engage in cocoa production. Farmers remarked that they were in the process of switching completely into cocoa production and would only cultivate food crops on subsistence basis. This finding appears to explain the claim by MADU that production levels of food crops are declining. Farmers’ decision to switch into tree cropping, however, has implications for the attainment of food access and hunger-related SDG targets.

3.5. Coping strategies to input and food crop price fluctuations and their effectiveness

Albeit, farmers’ exposure to price fluctuations, respondents indicated that they lack formal training on how to manage price risks due to inadequate number and extension support/services. This was confirmed in an interview with the head of MADU who indicated that the Unit is unable to provide regular and timely extensions services due to financial constraints and absence of necessary logistics (vehicle and motor cycles) for officers. Regardless of this, the study identified that farmers’ deal with price volatility using their own “informal/indigenous” strategies. Farmers indicated that they had no means to cope with fluctuations with respect to input prices, as they had no control over the causes (oil prices, exchange rates, cocoa producer prices and inflation). However, from the study, five key strategies were adopted by farmers to cope with food crop price fluctuations.

First, farmers added value to crops (specifically by processing them into semi-finished or finished products) during periods when produce prices decline. Maize farmers, in particular, attested to the fact that they processed maize into ‘kenkey’Footnote4 or corn dough to obtain high returns than selling at its raw state when prices decline. Similarly, some cassava farmers processed harvested produce into gari (a popular West African food made from cassava tubers) which makes it easy to store for a comparatively longer period and also a means to obtaining a relatively high price, since gari attracts better price than the raw cassava. Farmers thus, resulted to value-adding activities such as agro-processing to prolong and sell produce at favourable prices (Gulati, Minot, Delgado, & Bora, Citation2007). Although this appeared to be common among some farmers, it tends to adversely affect poor farming households who could not switch from major staples. Hence, they result in taking less nutritious food when staples are unavailable. For this reason, the FAO (Citation2010) argues that unstable prices with food staples are detrimental to the poor as they lack dietary diversification. Hence, it is, therefore, necessary for the management of food crop prices as it mostly induces inappropriate household behaviour.

Secondly, the study identified that farmers diversified income sources to make up for falls in income. About 54% of the farmers, particularly women, indicated that they in addition to farming, engaged in palm oil and soap production. Petty retailing was also identified among the diversified livelihood strategies of farmers to generate additional income to support household income. Others kept livestock (such as sheep, goats and pigs) which they sold to raise additional income. Farmers indicated that these other activities served as a means of raising additional income to cover for losses whenever they were confronted with price shocks.

Additionally, farmers adopted mixed cropping in order not to risk losing out on price increase or losing investments in events of price falls. This according to them provided a safeguard against price fluctuations. Thus, as means of equally benefiting or minimising loses which resulted from eventual fluctuations in crop prices, they cultivate a number of crops on the same piece of land.

Global weather forecasts suggest that the erratic nature of the rainfall pattern will intensify. As this will compound the vulnerability of rain-fed agriculture in the study communities, farmers in the Municipality and Ghana, cannot be said to be resilient enough. Farmers in the Municipality were highly vulnerable to changes in the rainfall pattern. They had no access to irrigable lands due to the unavailability of irrigation infrastructure. They only coped by hoping that the weather will be favourable. Some took the risk of tilling wetlands for farming. Others migrated to other farming communities where the double rainfall regime was relatively favourable. Discussions with the Municipal Planning Department revealed that about 60% of economically active women in the Municipality migrate to Northern Nigeria between the months of November and April where the dry season is intense to undertake activities in the service and commerce sectors.

Some farmers coped with the variability in rainfall pattern by farming on flood plains. The lands are argued to be fertile due to the presence of alluvial soil deposited by the flood waters (Bullinger-Weber, Le Bayon, Claire, & Jean, Citation2007; Fuchs, Fischer, & Reverman, Citation2010). Such practices, however, disturb the natural environment. Premising on the finding that abundant supply of a particular produce causes a reduction in its price, farmers grow crops which are scarce before the planting season as a means of attracting high prices. Additionally, farmers sow earlier than the expected planting period in a manner which would allow them harvest and sell at better prices before most producers of similar crops harvest theirs to create surpluses which would distort the market price, thus resulting in fluctuations.

Finally, some farmers coped with the effects of crop price fluctuation on household income by cultivating cocoa. Given that food crops are subject to price falls, about 60% of the respondents had cultivated cocoa due to the producer purchasing price ceiling and other incentives provided by the government. This category of farmers was in the process of disengaging commercial food crop production. Farmers have thus, become risk-averse towards food crop production which could further exacerbate the threat to food availability and endanger food security. Several researchers have also argued on similar account on the surge of commercial tree agriculture as detrimental to physical and economic access to food in the future (Gilbert & Morgan, Citation2010; Giovannucci et al., Citation2012).

On the effectiveness of coping strategies, the study showed that farmers who “added value to crops” and “diversified income sources” as a coping strategy argued that the approaches were effective with mean values of 2.675 and 2.720, respectively (see Table ). The mean values fall close to the assigned Likert scale ‘3ʹ which shows the “effectiveness” of the variable. Interviews with some of the respondents revealed:

… I have always attempted to process the maize I harvest into flour for kenkey. It takes longer for it to go bad in that state. Although I do not sell at the same price (considerably better) as selling the harvested maize during high demands, processing it attracts food vendors who buy at a relatively better price.

during periods of price declines of food crops, I engage in retail trade to keep me busy until the next planting season. I know of some colleagues who go into livestock keeping, which to me is a bit expensive but it works for them.

Table 3. Effectiveness of coping strategies

Farmers who cultivated cocoa practiced mixed cropping and observation of production patterns of crops and planting seasons were however indifferent about the effectiveness of the strategies with mean values of 2.325, 1.775 and 2.250, respectively. The mean values fall close to the assigned Likert scale ‘2ʹ which shows the “indifference” of the variable. According to the farmers, engaging in mixed cropping reduced the volume and land sizes of the types of crops they produced which at some periods further reduced their incomes. Production levels have declined due to the unpredictable pattern of rainfall, and after harvesting when they expect to obtain incomes, demand sometimes turns to the downside of the crops considered. This contradicts findings of Rapsomanikis &Sarris (Citation2008) who identified mixed cropping as an efficient coping strategy for farmers against domestic price fluctuations in Ghana. Perhaps, during their study, rainfall patterns were quite predictable among farmers and declining demand was not entirely a challenge to the farmers. The dynamics have changed for urban farmers in Ejisu Juaben Municipality, thus, making mixed cropping which was once an efficient coping strategy, unsuitable for the cocoa farmers. Both Rapsomanikis and Sarris (Citation2008) study and this study considered the harvesting stage of crops cultivated as mixed cropping.

A farmer recounted that:

just last two planting seasons, when the price of plantain declined, I engaged in the cultivation of vegetables (pepper, garden eggs and tomatoes). The market for the vegetables was alarming and so had better prices for them. I did same thing just the last planting season and run at a loss because the demand for the vegetables was low compared to the plantain (which I did not cultivate much).

On production patterns, farmers asserted that:

it is generally very difficult to predict the rainfall pattern nowadays. You plant earlier, the rains fail. You plant later, the rain falls earlier…. we were caught by surprise last two years when we planted but the rains delayed. It greatly affected our output and revenue for that year because we had to hire extra hands and chemicals on the farm to keep the plants until the rains set in…. There have however been periods we have been successful and attained higher prices for our produce

Although most coping strategies were deemed effective, the shift to cocoa cultivation and faming on flood plains were noted to have an adverse environmental implication. The shift cocoa production has the potential of increasing the amount of work involved in clearing bushes and weeding, as well as resulting in the depletion of dense forest cover and changes in climatic conditions which is confirmed by other studies (Boni, Citation2005; IEC, Citation2013). Perera (Citation2001) further notes that clearing of land for tree crop production, such as cocoa destroys secondary forest cover. Also, farming in flood plains destroys the natural environment. For instance, the vegetation used as buffers to protect the water bodies is cleared which threaten their sustainability. Furthermore, the excessive and inappropriate use of agrochemicals for farming pollutes the water bodies and threatens aquatic lives.

4. Conclusion

Poverty is profound among farmers in Africa and specific to this study, urban areas in Ghana. Agricultural production is subject to several risks which affect productivity and traps farming households in poverty. Input and crop price volatility are among the many risks farmers barely have control over. Volatility in input and crop prices is caused by wide range of factors including economic, political, natural and ecological factors which have diversified effects on farmers. World food price volatility has negative impacts which result in undernourishment due to unstable prices of staple foods. The perception on causes and effects of price fluctuation thus has an important influence on the type and effectiveness of coping strategies to be put in place to improve wellbeing. The study on this premise sought to examine the perception of smallholder farmers on the causes and effects, and the strategies they adopt to cope with price fluctuations in inputs and food crops.

The study revealed that four major factors resulted in the volatility of input prices; oil prices, exchange rates, cocoa producer prices and inflation. Farmers, however, had no coping strategies to these because of limited or no control over them. It was revealed that farmers coped with food crop price fluctuations by: adding value to crops during periods when produce price decline; diversifying income sources by: engaging in livestock keeping, palm and soap production; adopting mixed cropping farming systems; farming in flood plains; and shifting away from food crop to cocoa production. These strategies according to farmers were largely effective as they aided them to gain additional income to supplement other household incomes. Some of them (shifting to cocoa production, and farming on flood plains) however had adverse environmental implications as they could result in the destruction of forest cover, pollution of water bodies due to the increased use of agro-chemicals. The capacity of farmers to manage these effects underline the sustainability of smallholder agriculture and food production as well as promoting food security.

Based on the above, the study recommends the formulation of an environmental strategy which should emphasise drought-resistant crop varieties with shorter gestation periods. This could be done by the crop research institutions such as the Council for Science and Industrial Research (CSIR) and faculties in the various universities which are into plant breeding. The farmers can thereby be introduced to the environmental strategy with the help of MADU, which serves as a decentralised public agricultural body to promote sustainable agricultural practices. There should also be conscious attempts to identify strategies for the establishment of reliable early warning systems to help farmers plan their activities with caution. These are intended to strengthen smallholder farmers’ resilience to the climate variability risks which result in price volatility and attendant effects. The study further recommends efforts to promote sustainable agricultural practices, specifically; promoting sustainable land and water management practices such as the zai and half-moon methods, stone banding and rain water harvesting; promoting the use of improved drought and disease resistant seeds and planting in the Municipality. MADU should further take conscious efforts to encourage the cultivation of vegetables (okra, tomatoes, garden eggs and green edible leafy vegetables) in the dry season as well as encouraging and protecting riparian vegetation in areas where favourable.

The study further calls for investment in research and development (R&D) on all indigenous strategies adopted by farmers to cope with input and food price. The MADU should as well conduct market analyses for the off-season/off-farm enterprises. The potential enterprises should be identified based on the communities’ comparative advantage. Investments into them should be carefully guided by the findings from market studies. Lastly, there is the need to facilitate the selection of crops based on communities’ capabilities and physical conditions to address the decline of prices due to bumper harvests of the same crops.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michael Osei Asibey

Michael Osei Asibey is a Ph.D. candidate, and a Graduate Teaching Assistant at the Department of Planning, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. Michael is an urban planning and development expert with specialization in urban agriculture, water and waste water treatment, water and sanitation and other issues relating to urban development.

Mohammed Abubakari

Mohammed Abubakari is an emerging global environmental researcher, with specific interest in environmental philospophy, ecological integrity and green governance, food security, climate change, resource politics, impact studies and community-based research. He assists IMANI Centre for Policy and Education, a top notch think tank in Ghana and Africa, in research.

Charles Peprah

Charles Peprah is a lecturer at the Department of Planning, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology with expertise in environment impact assessments, water and sanitation.

Notes

1. 1 cedi to 0.23 USD in 2008.

2. Twi is a language spoken by Akan, an ethnic group in Ghana, Twi has many dialects including the Akuapim Twi, the Fante Twi and the Ashanti Twi, which are all mutually intelligible. The people of Ejisu Juaben Municipality speak “Asante Twi” as a local language, and this happened to be the language used in collecting data from the respondents.

3. MADU could not provide quantitative data on yields of crops in the municipality for all years requested for (2001–2016). Again, manual calculations were done to convert production to common unit for comparison purposes.

4. Kenkey is a staple local dish prepared with maize flour, which is usually served with soup, pepper, stew or a source. It is similar to a sourdough dumpling from the Ga, Akan and Ewe inhabited regions of West Africa, Ghana.

References

- Afenyo, J. S. (2008). Making small scale farming work in Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fsn/docs/Making_Small_Scale_Farming_Work_in_SSA_-_By_Joy_S.__Afenyo.pdf

- Altieri, M., & Koohafkan, P. (2008). Enduring farms: Climate change, smallholders and traditional farming communities. In M. A. Altieri & P. Koohafkan, (Eds.), Penang, Malaysia: Third World Network.

- Amanor‐Boadu, V., (2012, April). Maize Price Trends in Ghana (2007‐2011). Monitoring, Evaluation and Technical Support Services (METSS)‐GhanaResearch and Issue Paper Series No. 01‐2012. Retrieved from https://www.agmanager.info/maize-price-trends-ghana-2007-2011 doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Antonaci, L., Demeke, M., & Vezzani, A., (2014). The challenges of managing agricultural price and production risks in sub-Saharan Africa. ESA Working Paper No. 14-09. Rome

- Arias, P., Hallam, D., Krivonos, E., & Morrison, J. (2013). Smallholder integration in changing food markets. Rome, Italy: Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO).

- Bäckman, S., & Sumelius, J. (2009). Identifying the driving forces behind price fluctuations and potential food crisis. Discussion Papers no. 35. Helsinki, Finland. Retrieved from http://www.mm.helsinki.fi/mmtal/julkaisut.html.

- Barker, J., Sedik, D., & Nagy, J. (2008). Food price fluctuations, policies and rural development in Europe and Central Asia. In J. Baker, D. Sadik, & J. G. Nagy, (Eds.), Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Bijman, J., Ton, G., & Maiti, C. K.(2007). Empowering smallholder farmers in markets national and international policy initiatives. ESFIM Working Paper 1. Wageningen: WUR

- Boni, S. (2005). Clearing the Ghanaian forest: Theories and practices of acquisition, transfer and utilisation of farming titles in the Sefwi-Akan area. Legon: Institute of African Studies.

- Bowler, D. E., Buyung-Ali, L., Knight, T. M., & Pullin, A. S. (2010). Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landscape and Urban Planning, 97(3), 147–20. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.05.006

- Bullinger-Weber, G., Le Bayon, R. C., Claire, G., & Jean, M. G. (2007). Influence of some physicochemical and biological parameters on soil structure formation in alluvial soils. European Journal of Soil Biology, 43, 57–70. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2006.05.003

- Byerlee, D., Janvry, A. D., & Sadoulet, E. (2010). Agriculture for development: Toward a new paradigm by keywords. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 1(1), 1–19.

- Cantore, N. (2012). Impact of the common agricultural policy on food price volatility for developing countries. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Challinor, A., Wheeler, T., Garforth, C., Craufurd, P., & Kassam, A. (2007). Assessing the vulnerability of food crop systems in Africa to climate change. Climatic Change, 83, 381–399. doi:10.1007/s10584-007-9249-0

- Chomitz, K. M., Buys, P., de Luca, T. S. T., & Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S. (2007). At loggerheads? Agricultural expansion, poverty reduction, and environment in the tropical forests. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Cohen, M., & Garrett, J. (2009). The food price crisis and urban food insecurity. London, UK: IIED.

- Collier, P., Conway, G., & Venables, T. (2008). Climate change and Africa. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24, 337–353. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn019

- Cooper, P. J. M., Dimes, J., Rao, K. P. C., Shapiro, B., Shefiraw, B., & Twomlow, S. (2008). Coping better with current climatic variability in the rain-fed farming systems of Sub-Saharan Africa: An essential first step in adapting to future climate change? Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 126(1–2), 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2008.01.007

- Davis, J. (2011). Agricultural price volatility and its impact on government and farmers: A few observations. OECD Agricultural Price Volatilities Conference: G20 Outreach (p. 18). Paris: UNCTAD, Special Unit on Commodities. Retrieved from http://www.unctad.info/en/Special-Unit-on-Commodities

- Davy, B. (2009). The poor and the land: Poverty, property and planning. The Town Planning Review, 80(30), 227-265.

- Demeke, M., Kiermeier, M., Sow, M., & Antonaci, L. (2016). Agriculture and food insecurity risk management in Africa: Concepts, lessons learned and review guidelines. Rome; Italy: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Diao, X., Hazell, P., Resnick, D., & Thurlow, J. (2006). The Role of Agriculture in Development: Implications for Sub-Saharan Africa No. 29, International Food Policy Reearch Institute, Washington, DC, USA.

- Diaz-Bonilla, E. (2016). Volatile volatility: Conceptual and measurement issues related to price trends and volatility. In M. Kalkuhl, J. von Braun, & M. Torero (Eds.), Food price volatility and its implications for food security and policy (pp. 35–57). Munich; Germany: Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland.

- Donye, A. O., & Ani, A. O. (2012). Risks and uncertainties in food production and their implications for extension work in Nigeria. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America, 3(9), 345–353. doi:10.5251/abjna.2012.3.9.345.353

- Ejisu-Juaben Municipal Assembly. (2014). 2014-2017 Metropolitan medium-term development plan. Ghana, Ejisu: Development Planning Unit. Ejisu-Juaben MunicipalAssembly.

- Fafchamps, M. (2009). Vulnerability, risk management, and agricultural development. Oxford; UK: CSAE WPS/2009-11.

- FAO,(2010). Price volatility in agricultural markets: Evidence, impact on food security and policy responses. Economic and Social Perspective-Policy Brief 12. Rome, Author. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/economic/es-policybriefs

- FAO. (2011). The state of food insecurity in the world: How does international price volatility affect domestic economies and food security? Rome; Italy: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

- FAO, IFAD, IMF, OCED, UNCTAD, WFP, The World Bank, The WTO, IFPRI &UN HLTF. 2011. Price volatility in food and agricultural markets: Policy responses. Rome: FAO. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/pricevolatilityinfoodandagriculturalmarketspolicyresponses.htm

- Ferris, S., Robbins, P., Best, R., Seville, D., Buxton, A., Shriver, J., & Wei, E., (2014). Linking smallholder farmers to markets and the implications for extension and advisory services. 4. Illinois, USA. Retrieved from: www.meas-extension.org

- Fox, S. (2012). Urbanisation as a global historical process: theory and evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 38(2), 285–310. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00493.x

- Fuchs, M., Fischer, M., & Reverman, R. (2010). Colluvial and Alluvial sediment archives temporally resolved by OSL dating: Implications for reconstructing soil erosion. Quaternary Geochronology, 5, 269–273. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2009.01.006

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). 2010 Population and housing census: District analytical report, Ejisu-Juaben municipality. Accra: Author.

- Gilbert, C. L., & Morgan, C. W. (2010). Food price volatility. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1554), 3023–3034. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0139

- Giovannucci, D., Scherr, S. J., Nierenberg, D., Hebebrand, C., Shapiro, J., Milder, J., & Wheeler, K. (2012). Food and Agriculture: The future of sustainability, A strategic input to the sustainable development in the 21st Century (SD21) project. New York. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2054838

- Groot, M. J., & Van’t Hoof, K. E. (2016). The hidden effects of dairy farming on public and environmental health in the Netherlands, India, Ethiopia, and Uganda, considering the use of antibiotics and other agro-chemicals. Front Public Health, 4, 12. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00012

- Gulati, A., Minot, N., Delgado, C. &., & Bora, S. (2007). Growth in high-value agriculture in Asia and the emergence of vertical links with farmers. In J. F. M. Swinnen (Ed.), Global Supply chains, standards and the poor: How the globalization of food systems and standards affects rural development and poverty (pp. 91–108). Oxford, England: CABI.

- Haile, G. M., Kalkuhl, M., & von Braun, J. (2016). Worldwide acreage and yield response to international price change and volatility: A dynamic panel data analysis for wheat, rice, corn and soybeans. In M. Kalkuhl, B. J. Von, & M. Torero (Eds.), Food price volatility and its implications for food security and policy (pp. 139–165). Munich; Germany: Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland.

- Hoyos, R., & Medvedev, D., (2009). Poverty effects of higher food prices: A global perspective. Policy Working Paper 4887. Washington, DC

- Huka, H., Ruoja, C., & Mchopa, A. (2014). Price fluctuation of agricultural products and its impact on small scale farmers development: Case analysis from Kilimanjaro Tanzania. European Journal of Business Management, 6(36), 155–161.

- IEC. (2013). Securing tomorrow’s energy today: Policy and regulations energy access for the poor. India: Author. Retrieved from http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-India/Lo/IEC/Energy_Access_for_the_Poor.pdf

- International Finance Corporation. (2013). Working with Smallholders. Washington, DC: IFC publication.

- Kahan, D. (2013) Managing risk in farming, Farm management extension guide. In S. Worth & A. Shepherd (Eds.), Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/uploads/media/3-ManagingRiskInternLores.pdf

- Kerry, C. (2012). Competing for land: The relationship between urban development and agriculture for lancaster and Seward Counties. An Undergraduate Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Environmental Studies Program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in Partial Fulfilment of Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Khan, Z. R., Midega, C. A. O., Pittchar, J. O., Murage, A. W., Birkett, M. A., Bruce, T. J. A., & Pickett, J. A. (2014). Achieving food security for one million sub-Saharan African poor through push-pull innovation by 2020. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1639), 20120284. doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0284

- Kolavalli, S., & Vigneri, M. (2011). Cocoa in Ghana: Shaping the success of an economy, Yes, Africa can: Success stories from a dynamic continent, 201-218, The World Bank. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/304221468001788072/930107812_201408252033945/additional/634310PUB0Yes0061512B09780821387450.pdf

- Lunner-Kolstrup, K., & Ssali, T. K. (2016). Awareness and need for Knowledge of health and safety among dairy farmers interviewed in Uganda. Frontiers in Public Health, 4(137), 1–10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00137

- Manoranjitham, S., & Jacob, S. K. (2007). Focus group discussion. Journal of the Nursing Association of India, 98(6), 125–127.

- Miller, R. L., & Brewer, J. D. (Eds.). (2003). The AZ of social research: A dictionary of key social science research concepts. UK: Sage.

- Mwambi, M. M., Oduol, J., Mshenga, P., & Saidi, M. (2014). Does contract farming improve smallholder income? The case of avocado farmers in Kenya. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 6(1), 2–20. doi:10.1108/JADEE-05-2013-0019

- Natural England. (2013). Green infrastructure: Valuation tools assessment. Natural England Commissioned Report NECR126. Retrieved from http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6264318517575680

- Perera, G. A. D. (2001). The secondary forest situation in Sri Lanka: A review. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 13(4), 768–785.

- Pitman, S. D., Daniels, C. B., & Ely, M. E. (2015). Green infrastructure as life support: Urban nature and climate change. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 139(1), 97–112. doi:10.1080/03721426.2015.1035219

- Potts, D. (2009). The slowing of sub-Saharan Africa’s urbanization: Evidence and implications for urban livelihoods. Environment and Urbanization, 21, 253–259. doi:10.1177/0956247809103026

- Rapsomanikis, G., & Sarris, A. (2008). Market integration and uncertainty: The impact of domestic and international commodity price volatility on agricultural income instability in Ghana, Vietnam, and Peru. Food Security: Indicators, Measurement, and the Impact of Trade Openness, 44(9), 1354–1381. doi:10.1080/00220380802265439

- Rother, H. A. (2008). South African farm workers’ interpretation of risk assessment data expressed as pictograms on pesticide labels. Environmental Research, 108, 419–427. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2008.07.005

- Satterthwaite, D., McGranahan, M., & Tacoli, C. (2010). Urbanization and its implications for food and farming. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 365, 2809–2820. doi:doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0136

- Wodon, Q., Tsimpo, C., & Coulombe, H., (2008). Assessing the potential impact on poverty of rising cereal prices. The World Bank. Human Development Network. Working Paper 4740