Abstract

Chickpea is a valued crop and provides nutritious food for an expanding world population and will become increasingly important with climate change. The nutritional value of chickpea in terms of nutrition and body health has been recently emphasized frequently by nutritionist in health and food area in many countries around the world. Production ranks third after beans with a mean annual production of over 11.5 million tons with most of the production centered in India. Land area devoted to chickpea has increased in recent years and now stands at an estimated 14.56 million hectares. Production per unit area has slowly but steadily increased since 1961 at about 6 kg/ha per annum. Over 2.3 million tons of chickpea enter world markets annually to supplement the needs of countries unable to meet demand through domestic production. Australia, Canada, and Argentina are leading exporters. Chickpea is comprised of Desi and Kabuli types. The Desi type is characterized by relatively small angular seeds with various coloring and sometimes spotted. The Kabuli type is characterized by larger seed sizes that are smoother and generally light colored. Dal is a major use for chickpea in South Asia while hummus is widely popular in many parts of the world. Research efforts at ICRISAT, ICARDA, and national programs have slowly but steadily increased yield potential of chickpea germplasm.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Chickpea is the most important cash and food security crop grown in the highlands of many countries over the world. It is produced both under rain fed and irrigated production systems. Despite its multifaceted importance, the productivity of chickpea generally in developing country is very low which is mostly associated among others with inappropriate agronomic practices, including the use of improper fertilizer rates, lack of market opportunity, and less efficient use of irrigation system. Hence, development of this review paper on the economic importance of chickpea is important to encourage newly emerging countries to produce more crop yield through providing current information on the global status of the chickpea crop production. Moreover, it is paramount necessary to boost the productivity of chickpea in regions producing this crop, thus the incomes and food security of the smallholder farmers in both developed and developing nations will be enhanced.

1. Introduction

Grain legumes play an important nutritional role in the diet of millions of people in the developing countries and are thus sometimes referred to as the poor man’s meat. Since legumes are vital sources of protein, calcium, iron, phosphorus, and other minerals, they form a significant part of the diet of vegetarians since the other food items they consume do not contain much protein (Latham, Citation1997). Legumes are multipurpose crops and are consumed either directly as food or in various processed forms or as feed in many farming systems (Kumara Charyulu & Deb, Citation2014). The legume crops are often grown as rotation crops with cereals because of their role in nitrogen fixation. However, over the past few decades, the yields and production of legume crops have been stagnant in the developing countries. Agricultural research and development efforts in many of these countries have concentrated on increasing cereal yields and production and lowering crop losses in order to achieve food security. Due to the diverse roles played by grain legume crops in farming systems and nutritional security, the research on legume crops will have significant impacts on nutritional security and soil fertility.

The recent rise in prices has led to an increase in demand for legumes worldwide through both income and population growth. The increasing demand for livestock feed in developing countries is a significant change in the demand structure. For instance, the significant demand of soybean in the bio-diesel industry due to the recent policies in Europe and the US has also contributed to the increase in the demand and prices of legumes as substitute crops. These factors indicate that, in the near future, there will be substantive shifts in the utilization patterns and price structure of grain legumes. However, pulses lag behind cereals in terms of area expansion and productivity gains. The main reason for this lag is that pulses are considered secondary to cereals in terms of consumer preferences and consequently, research activities focus more on cereals. Due to the high cereal productivity, pulses are being pushed to marginal areas of cultivation having low rainfall and poor soil fertility. Other reasons responsible for the lag include highly unstable prices of pulses due to high variability in their yield and high competition from cereal crops, such as rice and wheat, due to the government price support policy.

Approximately 6.5 billion people currently live on our planet, and by 2050, that number is projected to rise by almost 50% to over 9 billion. We will be increasingly faced with the demand to produce more food for more people with fewer resources, and we will need to draw more heavily on high quality crops to provide for this growing demand. Chickpea has a head start in this agricultural race. Chickpea is a good source of energy, protein, minerals, vitamins, fiber, and also contains potentially health-beneficial phytochemicals (Wood & Grusak, Citation2007). Chickpea is playing a leading role in food safety in the world by covering the deficit in proteins of daily food ration of Indian and African Sub Sahara populations. The designed chickpea-based infant follow-on formula meets the WHO/FAO requirements on complementary foods and also the EU regulations on follow-on formula with minimal addition of oils, minerals, and vitamins. It uses chickpea as a common source of carbohydrate and protein hence making it more economical and affordable for the developing countries without compromising the nutrition quality (Malunga et al., Citation2014). Opportunities in the major cropping regions depend on both reducing the crop risk and improving productivity (Redden & Berger, Citation2007). However, amongst pulse crops chickpea has consistently maintained a much more significant status, ranking second in area (15.3% of total) and third in production (15.42%).

Among pulses, chickpea is preferred to food legumes (Siddique et al., Citation2000) in some regions because of its multiple uses. Chickpea is considered to be unique because of its high level of protein content that accounts for almost 40% of its weight. Moreover, the grain chickpea legume crop has potential health benefits, which include reducing cardiovascular, diabetic, and cancer risks.

The main objective of this study is to analyze the global and regional trends in production, consumption, value, and trade of grain chickpea crop since 1961. The following regions are included for the trend analysis: South and South-East Asia (SSEA), Central and East Asia (CEA), Middle-East and North Africa (MENA), Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and Latin America and the Caribbean1 (LAC). Developed countries are included under the heading Developed World, which includes Europe, North and South America, and Australia, to enable a comparative analysis.

This study examines chickpea production, value, and trade on a global, regional, and country basis to determine trends in production and product availability through domestic and international export markets. World, regional, and country production, and demand data are reviewed to determine trends and future expectations for the chickpea crop and its importance in world trade. Data for this chapter were obtained from the FAOSTAT database provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Citation2019) that provides country and global estimates of crop production, area harvested, yields, exports, imports, and consumption since 1961. The data are used to identify trends in overall production, yields, value, and consumption of chickpea on a worldwide basis.

2. Material and methods

The secondary data available at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT) for the period of 1961–2017 was used in the study for the analysis of data. Hence, the accuracy of the results presented here are directly dependent on the FAO data source and the classifications therein. Despite the many limitations and weakness of the FAO data (Akibode & Maredia, Citation2012) on grain legumes, this report used the FAOSTAT as the primary source of time-series secondary data. This study focuses on the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) grain crop. Dry bean (Phaseolus spp.), dry broad bean (Vicia faba), chickpea (Cicer arietinum), dry cowpea (Vigna ungiculanta), pigeon pea (Cajanus cajun), lentil (Lens culinaris), and other pulses production status also included. In many developed and developing countries, these grain legumes have become the main component of farming systems and food of producers and consumers.

When the analysis was carried out for this study, the export and import data were available until 2016, and the production data were available till 2017 which was used for chickpea crop. Detailed production data were available in FAOSTAT for chickpea, dry bean, dry broad bean or fababean, dry cowpea, pigeon pea, and lentils that have been analyzed in this study. For all other crops, domestic availability (the sum of production and net trade, i.e., production + (export-imports)) has been calculated to serve as a proxy for demand. Simple statistical measures such as the mean and the compound annual growth rates (CAGRs) have been computed to analyze the trends. The availability of the crop differs from consumption with regard to stock variation from year to year, seed and wastage.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Grain chickpea crop area, yield and production: global context

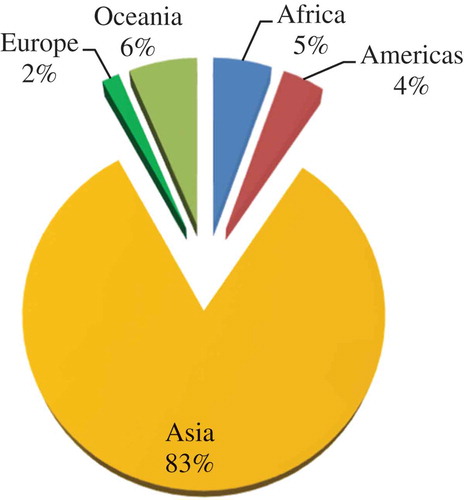

Since 1961, the global production of the entire grain legume crops, namely chickpea, pigeon pea, cowpea, dry bean, faba bean, lentil, has increased at the rate of more than 1% per annum. Globally, chickpea has yield levels of about 850 kg/ha. The crop yields in the developing regions are very low. However, in the case of chickpea, some developing regions have exceeded the developed countries in terms of yield levels. The yield level in South and South-East Asia has increased by 13% from 717 kg/ha in 1994–1996 to 812 kg/ha in 2008–2010, growing at an annual rate of 0.8% (Nedumaran et al., Citation2015). Mean annual production share of chickpeas by region from 2008 to 2017 revealed that Asia shares 83% globally (Figure ).

Figure 1. Mean annual production share of Chick peas by region from 2008 to 2017. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

Chickpea is grown all over the world in about 57 countries under varied environmental conditions. South and South-East Asia dominates in chickpea production with 80% of regional contribution. Although developed countries do not contribute much toward chickpea production, the yield is particularly high in some Eastern European countries. China also showed a high yield level at 4,537 kg/ha in 2013–2017. ICRISAT has released high-yielding, short-duration chickpea varieties that are resistant to Fusarium wilt in Southern India. Andhra Pradesh has the highest chickpea yields averaging 1.4 metric tons per ha. Almost 80% of the chickpea area in Myanmar during 2013–2017 was covered by ICRISAT-bred chickpea varieties.

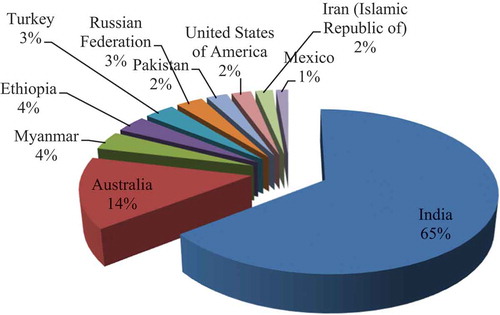

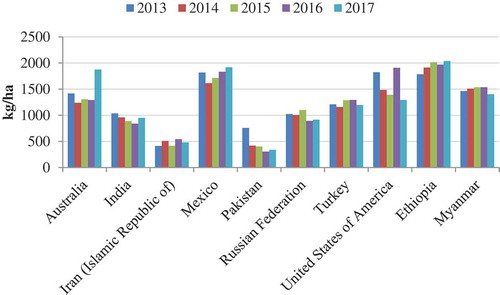

India is the single largest producer of chickpea in the world, accounting for 65% (9.075 million tonnes) of the total production under chickpea (Figure ). Australia is the second leading country over the world in 14% share. The average global chickpea yield is about 1.8 ton/ha, but the average yield in west and south Asia is only 1.46 tons/ha (Table ). Though the production is low in other developing countries, such as Turkey, Myanmar, Ethiopia, and Mexico, the yield levels exceed 1.8 ton/ha (Table ). The yield rates are above 2 tons/ha in Yemen and Russia. Similar or higher yield levels prevail in most developed countries (Table ).

Table 1. Mean annual global production of pulse crops 2008–2017

Table 2. Area harvested (hectares), mean yields (kg/ha), and total production (tons) from chickpea producing countries in important regions from 2013 to 2017

The highest yield increase was observed in sub-Saharan Africa at about 80% between 2013 and 2017 (Table ). West and South Asia showed a strong upward trend in the area under production and, therefore, production also follows suit from a low base. Area decline is observed in South America, and Middle-East and North Africa.

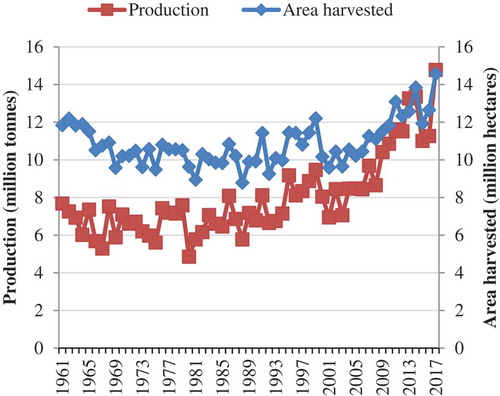

Worldwide, chickpea ranks third among the pulse crops and accounting for 11.67 million tons annually. This ranking places chickpea behind beans (25.66 million tons) and peas (11.69 million tons) with mean annual production of 11.67 million tons from 2013 to 2017 (Table ). Taken together, annual combined production of peas and chickpea is nearly equal to that of beans, an indication of their overall importance. These three pulses (beans, peas, and chickpeas) account for about 64.77% of global pulse production with chickpea accounting for approximately 15.42% of the total annually. Production of chickpea in terms of harvested area from 1961 to 2013 ranged from a low of 11.84 million hectares in 1961 to a high of 14.56 million hectares in 2017 (Figure ). Earlier production trends from 1961 to 2013, in terms of area harvested, was somewhat static or slightly declining; however, yield increases began to have an impact on total production starting in the late 1900s. Steady increases in production appear in the early 2000s and continue to the present, and especially since 2013.

Figure 2. Chickpea worldwide, area harvested (million hectares; filled diamond), and production (million tons; filled square) from 1961 to 2017. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

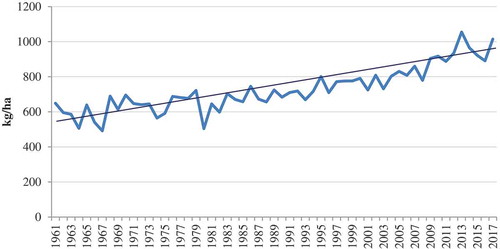

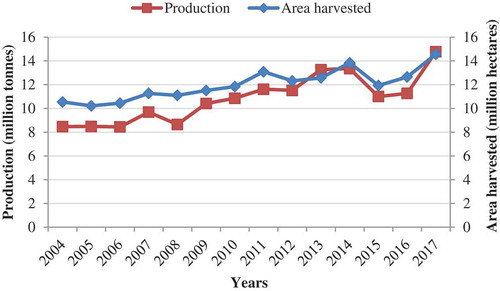

Chickpea yields have been steadily increasing globally since 1961 (Figure ) and trending to increases of over 6 kg/ha per annum. This positive development is likely the result and benefits of sustained research programs toward the development of improved germplasm and higher yielding varieties characterized by improved disease resistance and adaptation to environment. Also important are factors such as improved seed sources, seed supplies, and overall management practices. Expanded production in more productive environments also may account for these consistent yield increases. The expanded production in developed countries such as Australia, Canada, and the USA appears to have had a positive influence on mean yields worldwide. However, with the majority of production centered in South Asia and India in particular, production increases in South Asia have clearly had an impact globally. Production increases have been pronounced in the most recent 10-year period (Figure ). Area harvested and tonnage produced have expanded starting in 2004 leading up to 2017 where global production reached an all-time high of 14.78 million tons from nearly 14.56 million hectares. Gains in yield per hectare and area harvested are positively impacting overall production. Chickpea is produced in over 50 countries with India having the largest production and accounting for over 65% of total world production. Figure illustrates the dominance of India in chickpea production and the relative importance of the next most important producers. Australia, Myanmar, and Ethiopia, the next most important producers, account for 14%, 4%, and 4% of world production, respectively. Other major producing countries such as Turkey and Russia account for equal 3%; while Iran, USA, and Pakistan having an equal share of 2% of world production. Other important producing countries include Mexico, Malawi, Morocco, and Syria. Mean yields of chickpea have varied widely among producing countries and range from relatively low yields averaging 400–700 kg/ha in Iran, Malawi, Morocco, Pakistan, and Syria to relatively high yields in Ethiopia and Mexico (Figure ). India, the largest producer has had stable mean yields of about 935 kg/ha. The high yields in Mexico are largely due to the fact that most of the crop is irrigated and grown over the cool winter season.

Figure 3. Annual worldwide chickpea yields (kg/ha) and trend line from 1961 to 2017. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

Figure 4. Chickpea production worldwide, area harvested (million hectares; filled diamond), and tons (million t; filled square) from 2004 to 2017. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

Figure 5. Relative importance of the 10 leading chickpea producing countries. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

Figure 6. Mean yields (kg/ha) from 2013 to 2017 for the 10 leading chickpea producing countries. Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

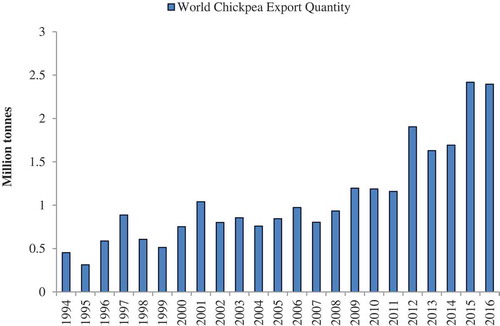

Area harvested, mean yields, and total productivity of chickpea producing countries in regions of the world are shown in Table . Ethiopia has emerged as the major producing country in Africa, while Iran and Turkey predominate the production in West Asia. Spain is the major producing country in Europe. In North America, Mexico predominates followed by USA and Canada. Most of this production is devoted to exports; however, the emergence of hummus as a popular value-added product in the USA has created domestic demand that now consumes over 65% of production. In South America, Argentina has become a major producer. Australia has become a major producer of chickpea with most of the production being exported to South Asia to meet current demand for the commodity in India and Pakistan (Figure ).

Figure 7. World chickpea export quantity from 1994 to 2017. Source Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (Citation2019).

3.2. Exports and from which countries

Considerable quantities of chickpea (estimated at 2.4 million tons) have entered world trade as consuming countries have been unable to meet demand through domestic production. Australia nearly meets half of world export demand and provides an over 926,802 tons to the market annually in the most recent period where data are available (FAOSTAT, Citation2019). Exports had a value of $905.7 million (Australian) in 2016 (Table ). India, while being the largest producer and importer of chickpea is also a major exporter ranking second only to Australia. Mexico, with a large production of high quality and large seeded Kabuli types, is the fifth most important exporter with the commodity being exported to over 50 countries worldwide with Algeria, Turkey, and Spain their most important customers. Turkey, also a major exporter with over 21,615.2 tons annually, with most of the tonnage moving to neighboring countries of Iraq, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia (Table ).

Table 3. Annual exports from major chickpea exporting countries from 2012 to 2016

3.3. Demand and consumption

Chickpea is divided into two distinct classifications. The most prominent type is referred to as “Desi” and is characterized by relatively small seeds that range from light tan to black and with many variations including various markings of anthocyanin pigmentation. The relatively small seeds have rather thick seed coats and yellow cotyledons. The seeds are often decorticated (seed coat removed) and cotyledons split to form a product referred to as “dal.” Dal, which can be made from most pulse crops, is used in soup making and is popular in South Asia. The less prominent type referred to as “Kabuli” is characterized by relatively large seeds that can range up to 22 mm in diameter and larger. Seed coats of Kabuli types lack pigment and are light tan and quite thin. This particular type is preferred in most markets outside of South Asia most likely because it is easier to produce and less expensive. Overall, world production of chickpea is predominated by the Desi type that accounts for 80% of production with the remaining 20% devoted to Kabuli types (Table ).

Table 4. Major chickpea importing countries (mean imports from 2012 to 2016)

3.4. Uses for chickpea

Chickpea is a highly nutritious and an inexpensive source of protein that is estimated at 24% and ranges from 15% to 30% (Hulse, Citation1994) depending on variety and environmental conditions. Chickpea also has estimated 60–65% carbohydrates, 6% fat and is a good source of minerals and essential B vitamins. There are numerous uses for Desi and Kabuli types. They can be boiled, eaten raw as a fresh vegetable, roasted, dehulled to make dal or processed into flour that can be added to bread. Dal made mostly from Desi types, used in making a soup that is served with rice in most areas of South Asia providing a nutritious combination of a cereal grain and a pulse crop. It is well known that the amino acids of pulses, particularly those containing sulfur amino acids compensate for those that are limiting in the cereals (Table ).

Table 5. Top 25 chickpea producing countries in 2017 in terms of tons produced and value ($)

4. Conclusions

Grain legumes are important as it is a source of income and nutrition to billions of smallholder farmers and consumers around the world. The main objective of this report is to examine the global and regional trends in area under cultivation, production, yield, trade, price, and consumption of chickpea. The trend analysis reveals the growing importance of chickpea crop across all economies and the lack of research efforts in the world. In the developed economies, the commercial benefits from expanding chickpea production are being realized more than ever in the past few decades.

Another matter of concern in chickpea production is the yield gap between developing countries and developed countries. This is evident from the fact that production in developed countries has increased due to yield improvements whereas in developing countries it has been primarily due to area expansion. Shifting chickpea cultivation to limited-irrigation zones and improving input usage can have a huge impact on boosting yields. Moreover, the government should take steps policy measures reduce the trade-off between land allocated for cereals and pulses substantially.

Chickpea have a thin and volatile market. A persistent increase in the demand for food chickpea legumes in Asia and Africa has led to a rise in imports. The money that is lost on foreign exchange could well be invested in the domestic market for attaining self-sufficiency. The demand for chickpea pulses spurred by the population and income growth in the developing countries has resulted in some developed countries increasing their domestic production to capture these markets. Therefore, it is high time the developed and developing countries to realize the huge potential of pulses in increasing the soil fertility and nutrition and take steps in increasing the productivity and thus, the production of chickpea.

Remarkable progress has been made in the production of chickpea in the past several decades. Yields have improved considerably which is a likely consequence of sustained research efforts by the international centers, ICARDA and ICRISAT, and national research and breeding programs. Expansion of production in new regions, particularly Australia and North America, has significantly contributed to overall world production and availability of the commodity in international markets. World trade has increased markedly in the past two decades likely due to demands of an increasing population and improving purchasing power of in developing countries. The outlook for chickpea is excellent considering the excellent nutrient concentrations and food value. Expansion of production to meet expanding demand is expected to continue.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mr. Desalegn Yadeta for his friendship and moral support in making this review a success.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bulti Merga

Bulti Merga works in School of Plant Sciences, Haramaya University, Ethiopia currently performing duties of lecturer and researcher. Bultis’ profession is Horticulture and Agronomy, and Coordinator for Highland Crops Research Improvement at Haramaya University, Ethiopia. His key research area is on potato, carrot, chickpea, and other vegetable crops research improvement.

Jema Haji

Jema Haji is a research scientist in the School of Agro-economics and Agri-business at Haramaya University, Ethiopia. His research interest is Development and Agricultural Economics.

References

- Akibode, C. S., & Maredia, M. K. (2012). Global and regional trends in production, trade and consumption of food legume crops (No. 1099-2016-89132).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2019). FAOSTAT Statistical Database of the United Nation Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) statistical division. Rome.

- Hulse, J. H. (1994). Nature, composition, and utilization of food legumes. In F. J. Muehlbauer & W. J. Kaiser (Eds.), Expanding the production and use of cool season food legumes (pp. 77–12). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0798-3_3

- Kumara Charyulu, D., & Deb, U. (2014, October 15–17). Proceedings of the "8th International Conference viability of small farmers in Asia”. International Conference on Targeting of Grain Legumes for Income and Nutritional Security in South Asia, Savar, Bangladesh.

- Latham, M. C. (1997). Human nutrition in the developing world (No. 29). Rome: Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Malunga, L. N., Bar-El, S. D., Zinal, E., Berkovich, Z., Abbo, S., & Reifen, R. (2014). The potential use of chickpeas in development of infant follow-on formula. Nutrition Journal, 13(1), 8. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-8

- Nedumaran, S., Abinaya, P., Jyosthnaa, P., Shraavya, B., Rao, P., & Bantilan, C. (2015). Grain legumes production, consumption and trade trends in developing countries. Working Paper Series No. 60.

- Redden, R. J., & Berger, J. D. (2007). Chickpea breeding and management: History and origin of chickpea. Oxfordshire, UK: CAB International.

- Siddique, K. H. M., Brinsmead, R. B., Knight, R., Knights, E. J., Paull, J. G., & Rose, I. A. (2000). Adaptation of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and faba bean (Vicia faba L.) to Australia. In R. Knight (Ed.), Linking research and marketing opportunities for pulses in the 21st century (pp. 289–303). Dordrecht: Kluwe Academic Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4385-1_26

- Wood, J. A., & Grusak, M. A. (2007). Nutritional value of chickpea. Chickpea Breeding and Management, 101–142.