Abstract

The purpose of the study was mainly to document the farmer’s indigenous knowledge (IK) systems on tree conservation and farming practices. The research further assesses the traditional way of soil acidity amendment in highland (dega) agroecological zone. This study combines broadly qualitative methods of anthropological approach to document farmers’ IK in tree conservation, and acidic soil amendments. Data were collected by using the semi-structured interviews, key informant interviews, participatory observation, and focused group discussion. The semi-structured interviews were conducted with a sample of 60 respondents in different agroecological zones to assess the traditional farming practices and tree conservation. The study revealed that, farmers had entrenched and sound local knowledge of tree conservation and acidic soil amendment practices. The “baabbo” and “Mona” are traditional ways of tree conservation and soil acidity amendment practices in mid-land and highland agroecological zones, respectively. The “baabbo” is native and multipurpose tree conservation and retaining traditions on farms. The farmers are deliberately retained indigenous “baabbo” trees in and around the farms for various benefits (such as shading, soil fertility, flooding control, fuelwood, constructions, and fodder). The main and first benefit of “baabbo” conservation is ”shading for crop productivity’’ ranked followed by uses for “soil fertility’’, “fuelwood’’, and ”construction materials’’ and ”cultural values’’. In addition, “mona” is an indigenous way of soil acidity amendment with indigenous fertilizer (organic) in highland agroclimate area (Dega). It is bedding places for animals (cattle and horses) which built near to farmer’s houses or farm-fields for collection of indigenous fertilizer (animal manure). This traditional approach of acidic soil amendment is enabling the farmers to sustain their livelihoods under unfavorable condition without adversely affecting the environment. Therefore, ‘mona’ as well as ‘baabbo’ is an indigenous farming practice that had used by local people to improve their livelihoods and novel approaches to maintain environmental sustainability.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper deals with the role of indigenous knowledge system for tree biodiversity conservation, soil acidity amendments and environmental conservation. The intent of the paper was to document local practices and farmers experiences in tree conservation and organic farming systems. The research is significant in empowering the indigenous people and their old-dating environmental knowledge. The finding might be interest to academics, policy makers, and scholars to conduct further researches, and the public in general in the area of agriculture, soil, agroforestry, culture, anthropology and environmental conservation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the study

Throughout the world, indigenous peoples are among the most valuable with respect to food production, conservation and management of critical ecosystems (Verschuuren, Mallarach, & Oviedo, Citation2008). Indigenous communities at different parts of the world have adapted and attached their livings with the surrounding physical world (Jafari & Kideghesho, Citation2009). They are interacting with natural ecosystems (such as soil, water, land, forest, trees and wildlife) for various socioeconomic aspects (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), Citation2005). Indigenous peoples’ relationships to their lands, territories and natural resources carry unique social, cultural, spiritual, economic and political dimensions and responsibilities (Adu-Gyamfi, Citation2011). Currently, indigenous communities and their civilizations have contributed greatly to the world’s agricultural diversity and environmental conservation (FAO, Citation2007). Their resource management practices and techniques contribute to the maintenance and adaptation of farm productive, sustainable and resilient approaches of ecosystem conservation (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), Citation2005).

Indigenous peoples’ agricultural, hunting, gathering, fishing, animal husbandry and forestry practices typically incorporate sustainable use of land and natural resources (Tanyanyiwa et al. Citation2011). The recognitions for indigenous people have their own ecological understandings, conservation practices and improving resource management approaches and it has positive impacts on sustaining local environments and its ecosystems for various uses (FAO, Citation2007). Indigenous knowledge (IK) of local people has now recognized as essential tools in environmental conservation, food production system and sustainable developments (UNESCO, Citation2011). IK refers to the perception that people have about their surrounding natural environment, which they use to adopt, adapt and develop technologies to their local context and to sustain their livelihoods (Adu-Gyamfi, Citation2011; Bhattarya & Tripathi, Citation2004). According to Warren (Citation1991), the term local or IK is used to distinguish the knowledge developed by a given community. Entirely, IK is the local knowledge (LK) that is unique to a given culture or society with unique local practices in agriculture, animal husbandry, healing diseases and biodiversity conservations (Warren, Citation1991). LK is contrasted with the international knowledge system generated by universities, research institutions and private firms (Appiah-Opoku, Citation2007). Moreover, it is the basis for local level decision-making in agriculture, health care, food preparation, education, natural resource managementand a host of other activities in rural communities for socioeconomic development (Warren, Citation1991). This LK is currently conceded as best strategies or candidate in the area of development, and conservation as a coping mechanism (World Bank, Citation2015).

Nowadays, the recognitions have been given by many stakeholders for local practices in the conservation of natural resources and solving local problems. Because, the current increasing rate of natural resource degradation is a major threat to both human and animal survival. It has been pressing environmental challenges that nations face collectively (Hibbarda et al., Citation2010; Karanam, Nadipena, Velaga, Gummapu, & Edara, Citation2013). The loss of each species has been causing the loss of potential economic benefits, as well as the cultural values of ecosystems (Attuquayefio & Fobil, Citation2005). As such, there has been much increased interest with issues relating to the environment conservation and call for resilient strategies. Indeed, the international knowledge (scientific) has taken the leading steps in ensuring proper conservation of the environmental resources via formal and professional standards. However, before the introduction of modern forms of natural resource management, the indigenous African communities often developed elaborate and viable traditional environmental conservation approaches (Ostrom, Citation1990; Roe, Nelson, & Sandbrook, Citation2009). For instance, Traditional African societies have environmental ethics that help in regulating their interactions with the natural environment (Shastri, Bhat, Nagaraja, Murali, & Ravindranath, Citation2002).

Local people have developed a variety of consistent resource conservation and management strategies in tropical Africa (Appiah-Opoku, Citation2007). These local practices have been enhancing agricultural productivity, conservation and improving food security. Thus, the increasing attention paid to local ecological knowledge in recent years in various domains of development (Edmundo, Delve, Trejo, & Thomas, Citation2002). Traditional farmers’ throughout the tropics exhibit a deep understanding of their environment and how to utilized local environment for livelihoods (Talawar & Rhodes, Citation1998). Similarly in Ethiopia, farmers have old dating experience and time-tested environmental knowledge of soil and water conservation (SWC), agricultural practices, natural resource management, knowledge of indigenous agroforestry system and biodiversity conservation. Further, the farmers have old experience in local technologies adaptation mechanism in various aspects of agriculture, food production and ecosystem conservation (eg. Konso indigenous terracing, traditional agroforestry system of Gedeo), coping strategies of Borena and Afar pastoralist, local healing systems and food production in many rural area (Ocho, Citation2012). In addition to this, Getahun (Citation2013) in his study stated a variety of indigenous soil fertility management and conservation techniques of Ethiopia farmers. Some of these include crop rotation, manuring, mixed cropping, terracing, fallowingand planting legumes and adaptation of agroforestry.

Similarly, the Gedeo’s (an ethnic group south of Ethiopia) renowned indigenous agroforestry system that combined sustainable practices with viable conservation of endangered woody species, and diversified wildlife (Anon, Citation2014). In fact, Gedeo topography is very rugged (irregular) or undulate shape in nature with up and down landscapes (steeply slope) that highly contributed to soil erosion (Tadesse, Citation2002). Many research findings confirmed that steep slope and undulated geographical features have been highly vulnerable for soil erosion (runoff) and environmental degradation. However, since time immemorial, Gedeo landscape is not yet vulnerable for serious soil erosion and land degradations due to the intensive practicing of an indigenous agroforestry system.

Off course, soil fertility declining and land degradation in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is serious environmental problems (Zingore, Murwira, Delve, & Giller, Citation2007). Diverse shade tree is retained in farming landscapes but recently they are threatening because of tree cutting for firewood, charcoal and associated agricultural problems (FAO, Citation2011).

On the other hand, improving soil fertility has becoming a major issue for low productivity in agriculture in SSA. Similarly, land degradation in the form of soil erosion and environmental degradation is a major challenge in the Ethiopian highlands and it has puts impacts on crop productivity, food security and environments (Adimassu, Langan, Johnston, Mekuria, & Amede, Citation2017; Laekemariam, Kibret, Mamo, Karltun, & Gebrekidan, Citation2016; Teklu, Williams, & Fanuel, Citation2018). In addition to this, low levels of input use, moisture stress, soil chemical degradation in the form of soil acidity and salinity/sodicity are some of the major crop production constraints in Ethiopia (Alemayehu, Dorosh, & Sinafikeh, Citation2011). Indeed, soil acidity is one of the serious problems constraining crop production in small-scale farmers of the central, western and southern highlands of Ethiopia where precipitation is high enough to leach down soluble salts. Haile et al. (Citation2017) estimated that ~43% of the Ethiopian-cultivated land is affected by soil acidity and associated agricultural problems). However, the local people have been adapting and using various practices for improving agricultural as well as environmental problems such as SWC system, soil fertility maintenances measures and practices. These resilient indigenous practices are recognized as coping strategies for small-scale rural farmers in many of tropical africa (Rim-Rukel et al., Citation2013).

In similar cases, the indigenous farmers of Gedeo communities have been protecting and conserving soil resources via local knowledge. These practices are enabling them to produce more foods and to improve their livelihoods in rugged topography without adverse impacts on environments (Tadesse, Citation2002; Messele, Citation2012). Nyonya (et al., Citation2006) argued that, land degradation, soil erosion and nutrient depletion contributing significantly to low agricultural productivity, poverty and food insecurity in many hilly areas. In contrast, the study conducted by (Tadesse, Citation2002) stated that due to the traditional practices and local knowledge, Gedeo farmers have been creating ecological sound and economical attractive land-use systems. They have been sustaining their livelihoods and environmental conservation in rugged and undulated landscapes without exposing themselves to food insecurity, floodingand soil erosion (Tadesse, Citation2002; SLUF, Citation2006). Therefore, the current study is geared to document the IK practices of tree conservation, soil fertility management and acidic soil amendments in highland (dega) and midland (Woina-dega) agroecological zones.

1.2. The objectives of the study

a) To document farmers’ IK of tree conservation traditions and its’ conservation benefits.

b) To assess traditional ways of soil acidity amendment in highland (Dega) agroecological zone.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

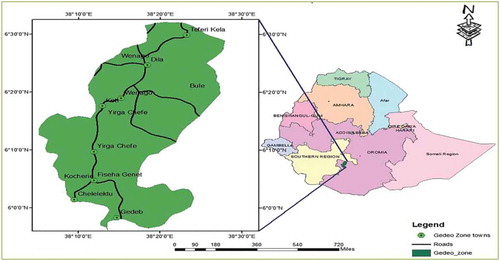

The study was conducted in the Gedeo zone (Gedeo community) which is located 369 km from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, and 90 km from the regional capital Hawassa, to the south on the main highway from Addis Ababa to Moyale toward Kenya (Figure ). Administratively, it lies in the South Nation Nationalities and People Regional State (Southern Region of Ethiopia) one of the nine self-administering regions in Ethiopia. Geographically, Gedeo zone is located north of the equator from 5°53ʹN to 6° 27ʹN latitude and from 38° 8ʹ to 38° 30ʹE longitude (Negash, Yirdaw, & Luukkanen, Citation2012). The altitude ranges from 1500 to 3000 m above sea level.

The Gedeo highland receives both equatorials and monsoons, the two most important trade winds in the region (Tadesse, Citation2002). It is situated in the Rift Valley in Southern Ethiopia. The Gedeo community shares boundaries with the Oromia regional state in the East, West and South, and Sidama zone in the North. The total area of the zone is 134,708 ha. According to the current government administrative division, the zone consists of six woredas (Districts) and two administration towns (Figure ). The Gedeo zone is part of the intertropical convergence zone (Tadesse, Citation2002) and experiences annual rainfall in the range of 800–1800 mm and the mean annual temperature varies from 12.5°C to 25°C (Negash et al., Citation2012).

2.2. The study design and sampling techniques

The study area traditional classified into three agroecological zones (such as Dega, Woinadega and Kolla) (Tadesse, Citation2002; Bogale, 2007).

1. Ensete-coffee- tree-based agroforestry at altitudes ranging above 2300 m.a.sl. (Representing Dega)

2. Ensete-coffee-fruit - tree-based agroforestry at altitudes 1500–2300 m.a.sl. (Representing woina-dega)

3. Fruit-coffee- crop-tree-based agroforestry at altitudes below 1500 m.a.sl. (Representing kolla)

This study was included only two main agroecological zones (which representing Dega and woinadega). A total of three peasant associations (PAs) (kebeles), two from Woinadega (Midland) and one from Dega (Highland) agroecological zones were purposefully selected-based on the presence of intensive practicing of indigenous agroforestry systems, population density and the adversely affecting level of soil acidity. The Gubato-ware, Mokonissa, and wogida were the three selected kebeles (PAs) from each agroecological zone for the current study. The Mokonissa and Wogida kebeles were representing midland (1500–2000 m.a.sl.) and The Gubbato-ware kebele is representing the highland agroecological zone (above 2000 m.a.sl.). It also good representation to document IK of soil acidity amendment practices in this area. Furthermore, the Gubato-ware PA (kebele) is seriously affected site by soil acidity problems and the soil PH-value was measured less than 4 which is categorized as strong acid (BWAO, Citation2016).

Methodological, this study combines broadly qualitative methods with an ethnographic study approaches to document farmers’ IKon tree conservation and soil acidity amendments both in highland (dega) and midland agroclimate zones, respectively. The data were collected through direct interactions with participants (farmers). A short survey also conducted to support qualitative data in the aim of knowledge documentations and to understand the reasons for tree conservation and preservation. Personal interviews, semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions and key informant interviews were conducted at three different study sites. A total of 60 households (farmers) were purposively selected from the three PAs and interviewed with semi-structured questionnaires. The age was also relevant variable regarding the knowledge documentations and gather in-depth information. Hence, the researcher has included all age classes from 20 up to 90 years. During data collection the local name of each of the tree specious, tree conservation reasons, and its benefits, and sources of organic manure were asked and documented based on the research objectives. General, the objective of this study was documenting the traditional farming knowledge and understanding their integral experience on tree conservation and soil amendments.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Trees and cultural importance (bio-cultural associations)

The study revealed that, the farmers of study area had well-sounded IK of tree conservation for cultural purposes. According to the respondent’s perception, trees are crucial and the socioeconomic aspect of local community was well-established on tree conservation and protection. As confirmed by local farmers, ”tree is life provider and bases for various socioeconomic aspects. They further states: In our community, the village lack Elderly men (lumolla gedhee gophekki olla’ii) and the farms not retained big trees are the same and conceded as nakedness’’. Hence, since time immemorial, large trees have been protected in different niches such as songo sacred sites, sacred forest patches, farm fields (fichi giddi baabbo) and roadsides (orri giddixxa lumolla haqqee)’’. For instance, trees were revered in songo sacred places for ritual as well as cultural purposes. Traditional, songo sacred places were revered places with majestic songo totemic trees (dhadachcha). These songo sacred trees were venerated as respectful objectives and setting aside for cultural purpose only.

Songo cultural Elders (songottixxi gedhee) noted that:

“Songo is the well-known public meeting place in Gedeo community and it is regarded as ritualistic as well as public meeting places to perform cultural ceremonies (such as prayer, swearing, pronouncing curses, purification, libations, reconciliation, and rainmaking rituals). It is also acknowledged as sacred place and sacrifices were offered’’. Further, this sacred place serves as a shelter for cultural elders and local congress (yaa’a). The sacredness of these respectful places was assured by existence of songo totemic trees (dhadachcha). In addition to this, not all tree species are setting retained in songo sacred site as songo totemic trees, and selective native tree spp only revered and setting aside for cultural purposes.

According to Gedeo elders, seven tree species were allowed to preserve in songo places as totemic trees (Dhadachcha). Cordia africana, Podocarpus falcatus, Croton macrostachyus, Ficus vasta, Syzygium guineense, Ficus specious and (Dhuggo) were songo sacred tree species used for cultural purposes (Table ).

Table 1. Traditional belief systems associated with songo sacred trees

Table 2. Some selected baabbo tree species and its conservation reasons.

The songo leaders stated that, songo sacred trees are traditional posses the rainmaking and disaster averting spiritual power (Qarro). Therefore, since time immemorial under these respectful trees rain-making rituals (qexxalla) and prayers (kadhdha) have been performed. In terms of conservation, all communities’ members should responsible and compelled to protect sacred trees from injuring. One of the Elderly men revealed that, songo trees are left untouched until they grow old and die. Even, the branches and deadwoods of sacred trees are not allowed to house uses. In case, any mismanagement of the songo sacred trees could cause negative setbacks (such as serious illness, disaster in the village, misfortune and pronouncing curses in offender).

3.2. Indigenous “baabbo” system and tree conservation in mid-land (Woina-Dega) farmers

The interview conducted with respondents revealed that, tree planting is an entrenched part of the cultural, economic and ecological traditions of Gedeo community. Baabbo is a traditional way of tree conservation and utilization tradition for various socioeconomic purposes. These indigenous ways of trees or “baabbo’’ conservation systems have been shaped and regulated by traditional sanctions (seera). The community Elders revealed that, since time immemorial, Gedeo community has ”seera’’ or traditional unwritten rules. This, traditional seera is regulated and guided the individual how to use, utilized and preserve the native trees and other environmental resources. These cultural accepted rules and regulations (seera) basically embraced in traditional beliefs and enforced by prohibition of mass cutting of baabbo trees that retained on the farms. above all, these rules and regulations are compelled the individual person to make perpetaute care and nurture for indigenous trees and other ecosystems on the farms. In addition to this, “seera” (unwritten rules) is not allowed or to cut trees from the grave, sacred sites, and mass-cutting of baabbo native trees from farms and strictly prohibits felling of large tree from roadsides. In case, any disobedience and mismanagement of 'seera' accepted as unethical or rule break, it could bring punishment via misfortune such as (rain shortage, barness, disease-out break and weak acceptance among the communities). General, baabbo culture is a best example of in-situ conservation tree biodiversity, where native tree species retained frequently and found plenty.

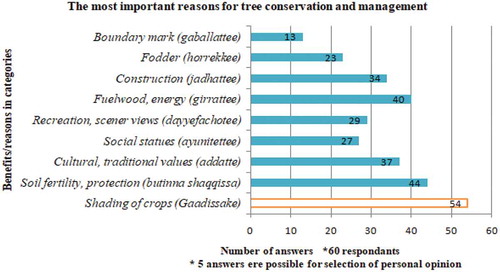

There are several reasons for the conservation of trees (baabbo) in Gedeo community. As illustrated in the below figure the main and first benefit is ”shading for crops (like coffee and enset) and farm productivity’’ ranked followed by uses for ”soil fertility’’, ”fuelwood’’, and ”construction materials’’ and ”cultural values’’. This is in contrast to findings of (Hillbrand, Citation2012) in who ranked ”food supply’’ first followed by uses for ”firewood’’ and ” construction materials’’. General, this indicates that, farmers values different ecological benefits of trees (such as soil fertility, conservation, and erosion control). Above all, the shading is the most important values of trees for crops productivity (enset and coffee), enhancing human and animal health by maintaining fresh and clear air and improving local climatic conditions. the local farmers also percieve high recreational values of large trees (Figure ). for example, the local people during the focused group discussion stated that, " when we views surrounding green environment and scenic landscapes with large trees, we feel excitement, happinnes, and make us more happy. even, in our community, the green (plants, trees, herbs, or grasses) are accepted as blossom and declaration of the upcoming good fortune, hope and prosperities".

On the other hand, farmers indicated that, Baabbo trees also associated with social statues (reputation) in the study area (Figure ). The personal dignity or reputation is highly related with ownership/conservation of large trees (Baabbo) on the farms. The respondents revealed that, the farmers who frequently managed their lands or cultivating farms regularly with intensive care and nurturing of baabbo trees are social recognition as toughest and salute in the villages for their conservation and care for large trees on the farms "baabbo baabbaa". Thus, farmers are carefully protected and conserve trees on the farms and give the perpetuate care and nurture for baabbo species on the farm ecosystems. According to the farmers. this such social recognizing tradition and practices has been discouraging the mass-cutting or clearing of large native trees from farms. Thus, the farmers have entrenched traditional knowledge of tree conservation and preservation for various socio-economic as well as ecological purposes.

Trees are plays a great roles in social affairs, for instance, before marriage proposal acceptance (bride price), the father of daughter has gathering information about the men bride and his background whether he or his family has retained baabbo trees, enset and coffee on their farms or not. Traditionally, the family of bride daughter believed that, the survival of future married couples is perhaps depending on these three basic farming components (trees, coffee, and enset). Hence, apart from economic and ecological significances, trees are playing crucial roles in building social cohesion and harmony in studied community. Dhadhato, Wodessa, Mokenissa, Gudubo, Goribe, Ode'e, and Qillixxa were tree species that mentioned by farmers for social cohesion and aspects (Table ).

A large number of interviewed farmers stated that, "the problem of soil erosion (flooding), landslide, drought, starvation, and other environmental problems have not been happen as a dreadful problems''. The adverse impacts of flooding or soil erosion has insignificant effects on farmers livelihoods and surrounding natural environments. off course, the topography of study area is up and down which is undulated feature landscapes. it is highly exposed to soil erosion and flooding. But, the well-established knowledge of baabbo culture and tree nurturing traditions perhaps contributing not to be exposed to erosion and flooding. This time tested indigenous ecological knowledge of community is contributing to harness and to survive in undulated landscapes without exposing themselves and local environment to such disasters. According to the local farmers, there are many reasons for retaining trees on the farms such as shading crops, soil fertility improvement, litter-fall (copha) and flooding controls (Figure ). This indigenous way of soil and tree biodiversity conservation are enabling them to grow various crops by integrating them with baabbo trees in small size farmlands. According to the farmers perception, baabbo is natural native trees and environmental co-friends, where its litter-fall is quickly decomposes and enhance soil fertility, farm productivity and environmental sustainability apart from soil erosion prevention (Figure ).

This study is evident that the Gedeo indigenous agroforestry system actively included trees as part of their agricultural landscapes and source of livelihoods (Tadesse, Citation2002; Messele, Citation2007). According to the farmer’s interviews, these trees provide various benefits for household livelihoods (such as shade, construction, energy, soil fertility, fodder, cultural and aesthetic values) (Figure ). This is similar acknowledge in the findings of (Messele, Citation2007) that trees are used for a wide range of household uses (such as construction of houses, cooking, heating and household uses). In addition to this, the main forms of soil conservation and crop productivity enhancing mechanism within the study area is through practicing indigenous agroforestry (intercropping) and planting environmental friendly multipurpose trees (baabbo) on the farm landscapes.

Indigenous Gedeo farmers are well-informed about their environment and they know how to protect their ecology for livelihood improvements by using their old-dating traditional knowledge of agroforestry practices. Farmers have indigenously intercropping different perennial crops with multipurpose tree species (Baabbo) to enhance soil fertility, crop yields and farming productivity. Most commonly (wesse) (Ensete vetntricosum), Bunno (Coffea arabica) and fruit trees and native trees are intercropped with multi-purpose trees (Baabbo trees).

Especially in Gedeo indigenous agroforestry systems, trees are essential components and the livelihoods bases for rural farmers who heavily depend on the farming systems. Baabbo is the most ecologically sound and economical attractive tree species and well-established tradition of tree conservation in study area. Literally, Baabbo means native tree species retained or planted on the farms for socioeconomic as well as ecological reasons. Traditionally, Baabbo system is indigenously represents in-situ conservation by integrating native trees with perennial crops (enset and coffee) for ecological as well as economic benefits. The baabbo practice or culture only conceded for indigenous or native tree species as well as multipurpose trees. The baabbo tradition doesn't includes enset, coffee, fruit trees and exotic species. To conceded 'baabbo culture', the trees retained on farming landscapes it shoud be native, multipurpose, environmental friendly, social and economical viable. This is in contrast to findings of (Abiyot, Citation2012) in his finding baabbo is a traditional practice of maintaining the emerging seedlings of indigenous trees, fruits, enset, coffee and progeny of mainly exotic trees.

The farmers are using Baabbo culture for various purposes (such as for soil fertility enhancement, to mount crop productivities, to control pests and flooding and they also use the Baabbo as a source of house energy and construction materials). The local farmers stated that, tree species (baabbo) such as Millettia ferrunginea (dhadhatto), Veronia amygdalina (Ebicha), Cordia africana (Wodessa), Ode'e (Ficus elastica), and Qillixxa (Ficus vasta) were most important and crucial tree species frequently retained by farmers for crop productivity (particularly coffee and enset) (Table ). The farmers are perceived that, the litter-fall of these tree species is quickly decomposes and enhance soil fertility than exotic trees. Whereas, the tree species like croton macrostachy (mokenissa)is describing as having adverse effects on the coffee growing and yields. Because, the farmers perceive, the litter-fall (copha) of this tree species is not ecological good to enhance the soil fertility and its litter-fall also slowly decomposes. But, according to the farmers, this tree species is planting near to the enset plant, they perceived that, the tree residual is good for enset productivity and growth.

Mr. Badhasso Goollee, a local farmer had this to say: “Mixed farming (agroforestry practices) with Baabbo trees is efficiently conserves the soil and reduce crop vulnerability as well as increasing crop yields”.

3.3. Indigenous “Mona” systems or traditional soil acidity amendment practices with indigenous fertilizer in highland area (Dega)

The importance of indigenous practice in Gedeo community is critical to farmers’ livelihoods and environmental conservation. The local farmers have used various indgenous practices to harness the livelihoods sustainability under unfavorable environmental conditions. In the study area, the farmers have been living in highland (Dega) agroecological zone, are heavily depending on the traditional farming practices to lead their live in adverse conditions. This agrooecological climatic zone is highly or adversely affected by soil acidity and low farm yields. The soil acidity and associated agricultural problems are critical to low farm productivity. Particularly the farmers where living in Gubato-ware district were adversely affected with soil acidity and associated soil quality problems. However, Semi-structured interviews conducted with local farmers were indicated that, the indigenous practices have been enabling farmers to sustain their livelihoods under unfavorable environmental conditions. The indigenous farmers were struggling by using their consistence ecological knowledge to harness adverse environmental problems. To avert such a farming problem, the farmers of the study area have used various traditional practices and local-adapted resilient approaches. This environmental friendly practices were includes the traditional mona systems, manure and compost production knowledge and practices to treat acidic soil, crop rotation systems and indigenous copping strategies and resilient approach of farmers.

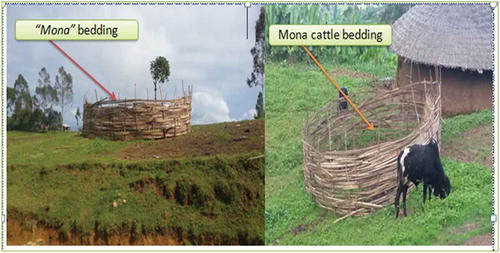

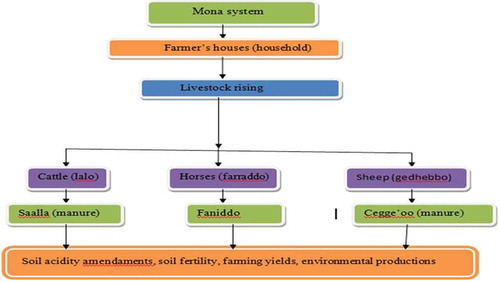

Most of all, Mona system is one of environmental resilient and local adapted indigenous practices used by farmers to amend acidic soil with organic manure for crop productivity and to improve soil quality. The farmers were described that; the “mona” is bedding or sleeping places for domestic animals (particularly for cattle and horses). Factually, “mona” is encircled fences where constructed from bamboo plant near to the farmer’s house or farm fields (Figure ). The main intention of “mona” building near the houses and farm fields is to collect animal dung/manure to produce organic fertilizer. The dung/manure is organic and easily available to every farmer’s family because of their own cattle in the home. Through this practice, they have their own storage of organic fertilizer. In sum, Farmers use to build a separate place for their cattle nearer to their homes in order to watch out for them as well. The dung produced by cattle is not just thrown away rather; it is a valuable product that is later on used as bio-fertilizer to raise the fertility of land and to amend adverse soil acidity.

Figure 3. ''Mona" or bedding place for livestock's (cattle and horses) for manure collections. (Source: The author, 2019).

The farmer revealed that, the mona system is most crucial traditional practice to treat soil acidity via raising livestock’s (like cattle and horses). It is the bedding place (horri galla bonchcho) for cattle and horses at night. According to the farmers, more often, at daytime the livestock (like cattle, horses) were grazing in open fields (pasture) while at night they have gathered together in “mona” (sleeping places as well as manure collection places). The main reasons for constructing or building 'mona' is to collect animal residuals (organic fertilizer) used by farmers to apply on farm crops. According to the farmers, the main intention for application is to make the soil regain the fertility, retain moisture, and to reduce the level of soil acidity (soil PH). Seasonal or based on the farming calendar, the farmers have collecting manure from mona places and applied to prepared farm-fields before planting the seasonal crops to reduce the adverse effects of soil acidity on crop yields and soil fertility (Figure ). The local farmers reported that, this traditional practice of acidic soil amendment or organic manure production approach was dating back and old practices in the area. During interviews, many farmers were repeatedly stated that, mona is indigenously life-sustaining strategies in the highland area (suubbo) to solve the agricultural problems of soil acidity, soil infertility, low yields and land unproductively.

Figure 4. The different sources of organic fertilizers used by farmers to increase soil fertility and acidic soil amendments. (Source: The author, 2019).

The farmer’s interviews repeatedly confirmed that, soil acidity and soil infertility were serious and chronic problems to the area. The woreda agricultural department annual report revealed that, the soil PH value is less than 4 which is categorized as strong acidification and it is difficult even to sustain life without organic/inorganic soil amendments. One of the farmers stated that, “life is hardship and unfavorable to sustain, the soil is too much is acidic and infertile, without mona rotations (dorissa) and practices, we couldn't gain a single unit of product from farms. Hence, to sustain our livelihoods and environments under unfavorable conditions and since time immemorial, we practices the traditional mona system by raising the livestock's to increase the foil fertility by reducing the level of soil acidity”. Similarly (McCauley et.al, Citation2017) support that, the soil is highly acidic (infertile) and the plant/crops couldn’t grow and lack the nutrient availability. In addition to the “mona” system, some farmers were also used the compost and house residuals to boost soil fertility and to support farm productivity (Figure 5). This is because, the farmers who had the small number of livestock’s, they were forced to use additional organic fertilizers such as (house residuals (mini gidi korra), coffee husks, farm compost, and sheep manure) to support mona system by using organic inputs (Figure and Figure ).

Figure 5. the preparation of manure and application system in the farm yields (Source: The author, 2019).

In addition to this, mona system is depends on farming calendar. Farmers’ interviews revealed that, Gedeo traditional climatic conditions are majorly divided into four farming seasons. These are Bonno (dry season), harisso (rain season), B’aa’llessa and adolessa. The traditional cropping calendar show that, Bonoo, from the month of August to January, Baleessa, from January to March and Haarsso, from March to May and Adooleessa from May to August. But, most of time the farming season is divided into two (harisso and bonno). The Harisso (rainy season) includes March to August and Bonno (dry season)includes September to January.

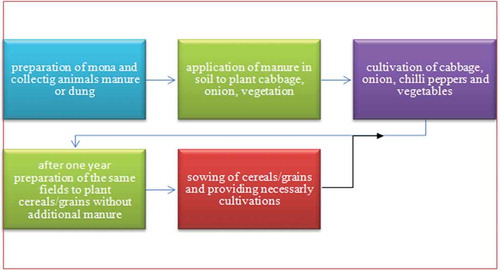

Similarly, the “mona” system is practicing based on the season farming systems and it is seasonal rotate from one place to other based on farming crops. The “mona” fence rotation is depending on climatic conditions. In rainyseason (Harisso) the farmers were rotated or take away “mona” fence to other places weekly to avoid murkiness of manure/dung. Whereas in dry season (bonno) the farmers were rotating the bedding place of livestock’s (mona) once in 3 months and after collection of manure or dung, it was transported to farming crops (Figure ). The most dominate agricultural crops in the studied area were cabbage (yehabesha gomen), onion (yehabesha shinkurt), potato (dinich), barely and other leaf crops. According to the respondents, with help of mona system individual farmer producing the cabbage and onion through the year. Whereas, the farmer cultivating barely (Hoedeum vulgare L.) once in a year at the same farming fields after harvesting the two dominate farming crops (cabbage and onion) (Figure ).

Figure 6. The flow chart showing an indigenous way of soil amendment and crop production systems. (Source: The author, 2019).

As stated earlier, the farmers perceived that, during the rainy season the manure or dung laid by (cattle or horses) could change into mud due to the heavy rain. Thus, in order to avoid the dirtiness of bedding place (mona), the farmers have changed mona places weekly from one place to other within farm fields. For this reason, before the arrival of rain season, the farmers have prepared the farm fields then transport the manure to the fields to enhance land productivity and to treat soil acidity with manure before the cultivation of farming crops/cereals. Final, in treated soil/land the farmers have planted the cabbage, onion, potato and other leaf crops. In addition to this, the crop rotation system is common traditional farming practice in the study area. The same land fields were used for various seasonal crops/cereals after soil treatments with manure or organic fertilizer. For instance, after harvesting cabbage, onion or potato, the farmers had prepared the same farm-fields for sowing cereals like Gebisi (Hoedeum vulgare L.) and Baqqela (Vicia faba L.), and Sinde (Triticum sativum). But, the farmers, weren't used additional organic inputs to treat soil for cereals after harvesting season of leaf or root crops. The farmers were perceived that, the manure applied for cabbage or onion during cultivation had the potential of reducing the level of soil acidity, then the they are directly sowing cereals like gebis (Heodeum vulgare L.) without additional demand for organic inputs (mona rotation) and soil amendments.

Figure 7. The production sources of organic manure or indigenous fertilizer (Source: The author, 2019).

Generally the farmers clearly stated that: “The mona is life provisioning practices in the area. Without mona rotation (mona dorissa), it is difficult to cultivate cabbage (Brassica integrifolia (west)), onion, and other crops due to the adverse of soil acidity. Entirely, life is difficult and thorny to stay alive without traditional farming practices like mona indigenous systems”.

In smallholder farming, women play an important role and their contribution to the farm income, soil fertility management and conservation is often disproportionately high in many rural areas of developing countries (Aryal et al. Citation2014). Similarly, the women of the study area had entrenched knowledge of manure production and its importance’s. The women were well aware of the need for organic materials to maintain soil fertility and land productivity. For instance, as mentioned by participants the women contribution is innumerable and crucial in compost preparation and soil fertility management. Women and their young children have provided the major share of the labor input to livestock keeping, including the transportation of manure and its’ spreading into the prepared fields. The study conducted by (WFDD, Citation2002) also confirmed that, overall, about 65% of the labor force is provided by women especially on farms that depend on subsistence crops and agricultural system.

In general, the women and childrenhave played crucial roles in preparing, managing and distributing the organic manure from mona places to farm fields. In addition to this, the weeding, planting and collection of house residuals as organic compost in house level also performed by women and their children (Figure ). Whenever possible, crop residues, manure and compost are regularly applied. All organic materials that produced house level were transported and carried by the women on their backs. Their role is, hence, not only critical for their families’ livelihoods but also for the long-term maintenance of soil fertility and land productivity.

3.4. Conclusion and recommendation

Traditional indigenous practices have contributed in the conservation of environmental resources and enhancing livelihoods in the study area. The study results show that IKis still valuable in the community. The livelihood of farmers is basically depending on LK involves tree (Baabbo) conservation knowledge for various benefits, soil fertility management and traditional soil amendment practices both in highland (Dega) and midland (woinadega) agroclimate area. For instance, the local farmers in highland (Dega) area have been adapting “mona” traditional soil acidity amendment practices. In this area, the life is unfavorable to sustain due to the soil acidity problems. As coping strategies, the farmers have raised the livestock’s (horse, cattle, sheep) and build a mona system to collect animal manure for soil fertility improvements. Hence, the farmers have been using various organic matters in highland area (such as house residuals, coffee husk residuals and manure and crop residual materials to enhance soil fertility).

Whereas in midland (woin-dega) farmers were using Baabbo system or tree conservation practices for various benefits (such as soil fertility management, crop shading, fodder, fuelwood, construction materials, soil erosion protection and cultural purposes). Millettia ferrunginea (Dhadhatto), gorbe (Albizia gummifera), wodessa (Cordia africana), ebicha (Veronia amygdalina Del.), odee (Ficus vasta), kilta (Ficus sur) and Erythrina aabyssinica Lam Ex. Dc (wollena) were major multipurpose tree species retained on farmland used by local farmers as livelihood strategies as well as environmental conservation benefits . This study also has put the further recommendations based on the research findings. To sustain the soil fertility and crop productivity, the IKof the farmers should integrate with scientific knowledge. The further experimental researches and scientific soil acidity amendment practices should conduct to improve the farmer’s livelihoods. Moreover, in study area, the livelihoods of farmers particularly in the highland area (Dega) basically depending on the bamboo plants for various uses (such as house construction, fencing, roof cover, livestock rearing and mona building. However, due to the age and climatic conditions the bamboo plants under ecological pressure and outright depletion/damages. Therefore, the concerned governmental body should propagate its seedlings scientifically for small-scale farmers. in additional this, the traditional way of farming practices (mona) should support technical with skilled experts (scientific knowledge) to solve the agricultural problems in a sustainable manner and to improve the livelihoods of small-scale farmers.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

We declare that the data and materials presented in this manuscript can be made available as per the editorial policy of the journal.

Consent for publication

All data and information are generated and organized by the authors.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

The people and organizations that were helpful in completing this research article need to be acknowledged. I wish to first express my sincere gratitude to my mentor and academic supervisors, Aster Gebrekristos (PhD) and Getahun Haile (PhD) for their scientific commitments, guidance and support in the preparation of this work. I am also thankful to my friends Abiyot Mebirat (PhD candidate), Fikadu Abebe (BA), Tateki Dori (PhD student) and Tedila Getahun (MA) for their support in diverse ways and encouragements during my research work. My hearty thanks also goes to the Gedeo zone culture and tourism office (Dilla) and Gedeo zone administration main office for financial and material support. I would like to express my deepest appreciation and thanks to Gedeo indigenous farmers for sharing their incredible knowledge and traditions in tree conservation, environmental conservation and acidic soil amendment practices.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yoseph Maru

A PhD student in Department of Natural Resource Management for Sustainable Agriculture in Dilla University, Southern Ethiopia, I have over six years experience of working in culture, tourism, and government communication affaires in Gedeo zone, Southern Ethiopia. Currently, I have conducting my PhD dissertation in topic of Indigenous Ecological Knowledge System as a tool for enhancing tree biodiversity conservation, carbon stocks and cultural values: Experience from Gedeo Community, Southern Ethiopia. I have presenting my different research works in various national and international research conference organized by Ethiopian Universities. I have currently has two journal articles under review in highly regarded journals.

References

- Abiyot, L. (2012). The dynamics of indigenous knowledge pertaining to agroforestry systems of Gedeo: Implication for sustainability. University of South Africa.

- Adimassu, Z., Langan, S., Johnston, R., Mekuria, W., & Amede, T. (2017). Impacts of soil and water conservation practices on crop yield, run-off, soil loss and nutrient loss in Ethiopia: Review and synthesis. Environmental Management, 59, 87–17. doi:10.1007/s00267-016-0776-1

- Adu-Gyamfi, M. (2011). Indigenous beliefs and practices in ecosystem conservation: Response of the church. Scriptura, 107, 145–155.

- Agegnehu, G., Yirga, C., & Erkossa, T. (2019). Soil Acidity Management. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Available from http://www.eiar.gov.et.

- Alemayehu, S. T., Dorosh, P., & Sinafikeh, A. (2011). Crop production in ethiopia: Regional patterns and trends. development strategy and governance division, international food policy research institute, Ethiopia strategy support program II, ESSP II Working Paper No. 0016.

- Anon (2014). ICCA consortium. [Online]. 17 September 2014. ICCA consortium. Available from: http://iccaconsortium.wordpress.com/. [Accessed: 10 March 2019].

- Appiah-Opoku, S. (2007). Indigenous beliefs and environmental stewardship: A rural Ghana experience. Journal of Cultural Geography, 22, 79–88.

- Aryal, K. (2014). Women's empowerment in building disaster resilient communities. Asian Journal of Women's Studies, 20(1), 164–174.

- Attuquayefio, D. K., & Fobil, J. N. (2005). An overview of wildlife conservation in Ghana: Challenges and prospects. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 7, 1–18.

- Bhattarya, S., & Tripathi, N. (2004). Integrating indigenous knowledge and GIS for participatory natural resource management: State of-the-practice. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 17, 1–13.

- Brihanu, A, Enyew, A, & Mekuria, A. (2014). Impacts of land use types on soil acidity in highland of ethiopia. Academia Journal Of Environmental Science, 2(8), 124–132.

- BWAO. (2016). The annual agricultural and natural resource conservation report (unpublished). Bule Woreda.

- Diacono, M., & Montemurro, F. (2010). Long-term effects of organic amendments on soil fertility. A Review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 30, 401–422.

- Edmundo, B., Delve, R. J., Trejo, M. T., & Thomas, R. J., Integration of local soil knowledge for improved soil management strategies, In: Symposium of 17th World Congress of Soil Science, Bangkok, Thailand, 2002

- FAO. (2007). State of the world forest. Rome: Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations.

- FAO. (2011). Women in agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development: The state of food and agriculture. Rome.

- Getahun, F. (2013). Farmers‘ indigenous knowledge: The missing link in the development of ethiopian agriculture: A case study of Dejen district, Amhara region. Social Science Research Report Series No.34

- Haile, H., Asefa, S., Regassa, A., Demssie, W., Kassie, K., & Gebrie, S. (2017). Extension manual for acid soil management (unpublished report). (A. T. A. (ATA), ed.), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Hibbarda, K., Janetos, A., van Vuuren, D. P., Pongratz, J., Rose, S. K., Betts, R., … Feddema, J. J. (2010). Research priorities in land use and land-cover change for the Earth system and integrated assessment modelling. International Journal of Climatology, 30(13), 2118–2128.

- Hillbrand, A. (2012). Indigenous agroforestry systems under pressure-the case of Gedeo agroforestry and its values to farmers livelihoods (MA thesis). Southern Ethiopia, Bangor University.

- Jafari, R., & Kideghesho,. (2009). The potentials of traditional African cultural practices in mitigating overexploitation of wildlife species and habitat loss: Experience of Tanzania. International Journal of Biodiversity Science & Management, 5(2), 83–94.

- Karanam, H., Nadipena, A. R., Velaga, V. R., Gummapu, J., & Edara, A. (2013). Land use/land cover patterns in and around Kolleru lake, Andhra Pradesh, India using remote sensing and GIS techniques. International Journal of Remote Sensing & Geoscience (IJRSG), 2(2), 1–7.

- Laekemariam, F., Kibret, K., Mamo, T., Karltun, E., & Gebrekidan, H. (2016). Physiographic characteristics of agricultural lands and farmers’ soil fertility management practices in Wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research, 5, 24. doi:10.1186/s40068-016-0076-z

- McCauley, A., Clain, J., & Kathrin, J. (2017). Soil PH and organic matter. Montain State University Review: Nutrient Management Module No. 8.

- Messele, N. (2007). Tree management and livelihoods in gedeo agroforests, Ethiopia. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 17(2), 157–168.

- Messele, N., Yirdaw, E., & Luukkanen, O. (2012). Potential of indigenous multistrata agroforests for maintaining native floristic diversity in the southeastern rift valley escrapment, Ethiopia. Agroforestry System, 85(1), 9–28.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA). (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: A framework for assessment. Washington, D.C. USA: Island Press.

- Mol, G., & Keesstra, S. D. (2012). Soil science in a changing world. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4, 473477.

- Negash, M. (2007). “Trees management and livelihoods in Gedeo’s Agroforests, Ethiopia”. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 17(2), 157–168.

- Negash, M., Yirdaw, E., & Luukkanen, O. (2012). “Potential of indigenous multistrata agro forests for maintaining native floristic diversity in the south-eastern Rift Valley escarpment, Ethiopia”. Agroforestry Systems, 85(1), 9–28.

- Nyonya, E. P., Gicheru, J., Woelcke. B., Okoba. D., Kilambya. D & Gachimbi, N. L. (2006). Economic and financial analysis of the agricultural productivity and sustainable land management project. Unpublished progress, Agricultural Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Ocho, D. L. (2012). Assessing the levels of food shortage using the traffic light metaphor by analyzing the gathering and consumption of wild food plants, crop parts and crop residues in Konso, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 8(30).

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Prado, J. A., & Weber, C. (2003). Facilitating the way for implementation of sustainable forest management. The case of Chile.Santiago: Global forest match..

- Rim-Rukel, G., & Irerhievwie, A. E. (2013). Traditional beliefs and conservation of natural resources. Evidence from selected communities in delta state. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 5(7), 426–432. Nigeria.

- Roe, D., Nelson, F., & Sandbrook, C. (eds). (2009). Community management of natural resources in Africa: Impacts, experiences and future directions, natural resource issues No. 18. London, UK: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Scotti, R., Bonanomi, G., Scelza, R. (2015). Organic amendments as sustainable tool to recovery fertility in intensive agricultural systems. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 15, 333–352.

- Shastri, C. M., Bhat, D. M., Nagaraja, B. C., Murali, K. S., & Ravindranath, N. H. (2002). Tree species diversity in a village ecosystem in Uttara Kannada district in Western Ghats, Karnataka. Current Science, 82, 1080–1084.

- Sustainable Land Use Forum (2006). Indigenous agroforestry practices and their implication on sustainable land use and natural resource management: The case of Wonago Woreda, SIDA and OXFAM. (unpublished doc), pp. 15.

- Tadesse, T. K. (2002). Five thousand years of sustainability?A case study on Gedeo land use (Southern Ethiopia). Wageningen: Treemail Publishers.

- Talawar, S., & Rhodes, R. (1998). Scientific and local classification and management of soils. Agriculture and Human Values, 15(1), 3.

- Tanyanyiwa, VI., & Chikwanha, M. (2011). The role of indigenous knowledge systems in the management of forest resources in mugabe area, Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development of Africa, 13(3), 132–149.

- Taye (2007). An overview of acid soils their management in Ethiopia paper presented in the third International Workshop on water management (Waterman) project, September, 19–21, 2007, Haramaya University, Haramaya, Ethiopia.

- Teklu, E., Williams, T. O., & Fanuel, L. (2018). Integrated soil, water and agronomic management effects on crop productivity and selected soil properties in Western Ethiopia. International Soil and Water Conservation Research, 6, 305–316. doi:10.1016/j.iswcr.2018.06.001

- UNESCO. (2011). Promoting and mobilizing local and indigenous knowledge for sustainable development. Jakarta, Indonesia, National workshop 7–8 June.

- Verschuuren, B., Mallarach, J.-M., & Oviedo, G. (2008). Sacred sites and protected areas. In Defining protected areas. Edited by Nigel Dudley and Sue Stolton (pp. 164–169). Gland: IUCN.

- Warren, D. M. (1991). Using indigenous knowledge for agricultural development. World Bank Discussion Paper 127. Washington, D.C.

- WFDD. (2002). Updated progress review of the women farmers development program. Kathmandu, Nepal: Author.

- World Bank, A. (2015). Indigenous latin America in the twenty century. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative common attribution cc by 3.o IGO.

- Zingore, S., Murwira, H. K., Delve, R. J., & Giller, K. E. (2007). Soil type, historical management and current resource allocation: Three dimensions regulating variability of maize yields and nutrient use efficiencies on African smallholder farms. Field Crop Research, 101, 296–305.