Abstract

This study evaluated the sensory properties and general acceptability of textured soy protein (TSP) incorporated into egusi (white seed melon- Cucumeropsis mannii) soup (TSP-soup) and stew-sauce (TSP-stew) consumed in southern Nigeria. Thirty TSP samples of various sizes and colors from different manufacturers (Harvest Innovation TSP crumbles and chunks (6), Wenger TSP from concentrate and flour (6), and ADM Textured vegetable protein (18)) were used for this study, and 20 trained panelists took part in the evaluations of their organoleptic quality and acceptability. The swelling ratio ranged from 2.05 for sample BST (ADM Textured Vegetable Protein, PRODUCT CODE 165,109) to 5.39 for BSP (WENGER TSP from Concentrate); the overall mean value was 2.61. There were significant differences (P < 0.05) in acceptability for both soups and sauces. The samples OST and RST from Harvest Innovation Hisolate Texsoy Chunks provided the most acceptable samples of TSP-stew; IST from ADM Textured Vegetable Protein TVP U–105 was the least rated. Sample RST was the best for TSP-soup, and the Harvest Innovation Hisolate Texsoy Crumbles (sample code ASP) and ADM Textured Vegetable Protein TVPU–814 (sample code GSP) were the best for TSP-stew. In conclusion, TSP granules were accepted by the consumers and can be incorporated as meat substitutes in both researched products.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The study aimed at evaluating the potentials of textured soy protein (TSP) as a substitute for meat in traditional egusi soup and stew consumed as a complementary sauce with “pounded yam,” or “eba (gari)” mostly in the southern part of Nigeria. It provided some necessary information on the sensory properties and general acceptability of these TSP-based products that could help to alleviate protein malnutrition. This condition is prevalent in most developing countries where people are unable to afford meat products in their diets. Promoting the consumption of soy foods may also contribute to a lower incidence of cardiovascular conditions and other related diseases.

Competing Interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

1. Practical application

The study aimed at evaluating the potentials of textured soy protein (TSP) as a substitute for meat in traditional egusi soup and stew consumed as a complementary sauce with “pounded yam,” or “eba (gari)” mostly in the southern part of Nigeria. It provided some necessary information on the sensory properties and general acceptability of these TSP-based products that could help to alleviate protein malnutrition. This condition is prevalent in most developing countries where people are unable to afford meat products in their diets. Promoting the consumption of soy foods may also contribute to a lower incidence of cardiovascular conditions and other related diseases.

2. Introduction

Soybean contains about 35–40% protein on a dry-weight basis with two storage globulins, 11S glycinin, and 7S b-conglycinin, making up 90% of this content (Torres, Torre-Villalvazo, & Tovar, Citation2006). These proteins contain all the amino acids essential to human nutrition and make soy products almost equivalent to animal sources in protein quality but with less saturated fat and no cholesterol (Young, Citation1991). Many potential benefits have been linked to the intake of soy products, according to epidemiological investigations (Anderson et al., Citation1995). For instance, consumption of soy foods may contribute to lower incidence of coronary heart diseases, atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes, and a decreased risk of certain types of carcinogenesis such as breast and prostate cancers, as well as better bone health and the relief of menopausal symptoms (Anderson et al., Citation1995).

Animal sources (i.e., eggs, milk, meat, fish, and poultry) provide high-quality protein; this is primarily due to the “completeness” of proteins from these sources (Hoffman & Falvo, Citation2004) although they are also associated with high intake of saturated fats and cholesterol (Hoffman & Falvo, Citation2004). Vegetable proteins (VP) when incorporated into foods, provide all the essential amino acids; they are an excellent source of protein, and reduce the intake of saturated fat and cholesterol. The available sources of VP are legumes, nuts, and soy (Hoffman & Falvo, Citation2004); it can also be found in a fibrous form called textured vegetable protein (TVP) that is produced from soybean flour in which proteins are isolated and extruded (Wild, Citation2018). TVP also is known as TSP or soy meat, is considered an excellent meat substitute; it is far more economical than first-class protein in addition to absorbing the taste and texture of regular meat (Wild, Citation2018).

Among the various characteristics TVP possesses are incredibly lightweight, availability in flavored and non-flavored forms, speed in preparation, versatile texture, high protein, and fiber content, and low levels of fat and sodium; it is a good source of amino acids and has a long shelf life. Many TVP products do not even contain Monosodium glutamate (MSG) that is mostly used as an additive in commercial foods although the results from both animal and human studies have demonstrated that the administration of even the lowest dose has a long-term toxic effect (Niaz, Zaplatic, & Spoor, Citation2018; Solomon, Gabriel, Henry, Adrian, & Anthony, Citation2015).

TSP refers to the defatted soy flours or concentrates mechanically processed by the extrusion process to obtain a meat-like chewy texture when hydrated and cooked (Singh, Kumar, Sabapathy, & Bawa, Citation2008). This product absorbs at least three times its weight in water when cooked for at least 15 minutes in boiling water (Riaz & Yada, Citation2004).

TVP is made from a process known as “extrusion cooking.” The dough is formed from high nitrogen solubility index (NSI) defatted soy flour and water in a “preconditioner” (mixing cylinder). The dough is cooked during passage through the barrel of a screw-type extruder such as the Wenger. Steam from an external source is usually employed to aid the cooking process. Upon exiting the “Die”, superheated steam escapes rapidly, producing an expanded—spongy yet fibrous—lamination of thermoplastic soy flour which takes on the various shapes of the die as it is sliced by revolving knives into granules, flakes, chunks, goulash, steakettes (schnitzel), etc., and then dried in an oven (Savvy Vegetarian, Citation2018). It is often regarded as a healthy choice because it is cholesterol-free and low in fat and calories (Asgar, Fazilah, Huda, Bhat, & Karim, Citation2010).

TSP is used as a meat extender or replacement in products such as meat sauces and meatballs; these replace up to 30% of the meat without adversely affecting the eating quality of such products (Zeki, Citation1992). Omwamba, Mahungu, and Faraj (Citation2014) reported that the granules obtained from defatted soybean flour were used to replace beef at various levels (up to about 50%) in samosa stuffing without significant differences in sensory attributes. When used as a meat extender, TSP not only offers economic savings but also serves to improve the quality of the product due to its ability to absorb water and fat and results in a juicier product (Zeki, Citation1992). In addition to its utilization as a meat extender, TSP is utilized as a meat analog or meat imitation. Although regarded as a poor man’s food, TSP offers an alternative to meat for vegetarians and a healthy choice for health-conscious consumers demanding low fat and low cholesterol diet. The market for TSP as a meat analogue is rapidly expanding in Western Europe but the same cannot be said of Africa, particularly West Africa, despite the high prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition and the high cost of animal protein sources such as meat and milk which are difficult for low-income populations to afford.

Successful incorporation of TSP into diets of consumers in West Africa as an alternative to meat will depend on the ability of TSP to meet their sensory requirements. Hence, evaluation of its sensory properties when incorporated into existing recipes is a crucial step in its acceptance. In the southern part of Nigeria, staples such as pounded yam and “eba” (cassava granules made into a paste) usually consumed with egusi (white-seed melon—Cucumeropsis mannii) soup with the addition of animal protein such as meat and fish. Egusi soup is a soup thickened with the ground melon seeds, and accessible in West Africa. Egusi is known as “akatoa of agushi” in Ghana and is used for soup and stew respectively as in Nigeria. Staples such as rice are consumed with stew, also with added meat or fish. The meat is mostly cut into chunks in the melon soup; smaller sizes almost like the minced form are used for stews. This study thus aims to evaluate the sensory properties of TSP of different sizes from three different manufacturers incorporated into a typical traditional Nigerian soup and a sauce.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Source and description of materials

Thirty (30) TSP samples, of different colors and shapes, were obtained from the University of Illinois, USA (Table ) as follows:

Table 1. Codes for TSP samples used for the selected dishes

Harvest Innovation TSP crumbles and chunks (6), Wenger TSP from concentrate and flour, (6), and ADM Textured vegetable protein (18).

3.2. Sample preparation

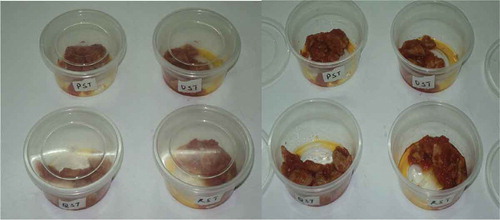

Samples of different sizes, shapes, and colors were used for preparing TSP-soup and TSP-stew. The samples were coded as presented in Table . Samples (in sizes between 70 and 100g, depending on availability) were soaked in a measured quantity of water for 10 minutes for re-hydration until almost doubled in size (Figure ). The remaining liquid was drained, and the soaked TSP samples were used for the preparation of the researched products (Table ). The ingredients and method of preparation are presented below.

Table 2. Rehydration data of textured soy protein (TSP) samples

3.2.1. Recipe for each sample of egusi soup

Blended pepper 5‒7 serving spoons

TSP 70–100 g

Egusi 1½ cups

Palm oil 3 serving spoons

Bouillon cubes 2 cubes

Salt To taste

The soup was made by frying blended pepper in hot palm oil for approximately 10 min. The ground melon seeds were mixed with water to form a paste and poured into the pepper and oil mixture already cooking and allowed to cook for 5 min. The soaked and drained TSP samples, bouillon cubes, and salt were added and cooked for a further 10 min. Total cooking time was approximately 25 min.

The ingredients below, with groundnut oil instead of the red palm oil, were used for the stew samples.

3.2.2. Recipe for each sample of stew sauce

Blended pepper 5–7 serving spoons

TSP 70‒100 g

Groundnut oil 3 serving spoons

Bouillon cube 2 cubes

Salt To taste

The groundnut oil was heated, and the blended pepper was fried for approximately 15 min. The soaked and drained TSP, bouillon cubes, and salt were added, and the stew cooked for an additional 10 min.

3.3. Sensory evaluation of tsp-soup and tsp-stew samples

3.3.1. Training of panelists

The organoleptic evaluation of the TSP samples for consumer acceptance and preference was carried out using 20 trained panelists (staff from various departments of IITA that were used to consuming egusi soup and stew sauces). The panelists were subjected to a basic taste recognition test to establish their taste thresholds for sweetness, saltiness, and sourness (Alamu, Maziya-Dixon, Menkir, & Olaofe, Citation2015). They were to evaluate the sensory properties based on color, aroma, taste, consistency, and general acceptability using a 5-point hedonic scale where 1 represents “dislike very much” and 5 = “like very much.”

Twenty-five panelists (15 females and 10 males) attended the training session for the evaluation process; however, only 20 were finally selected after the training. During sensory evaluation sessions, panelists were provided with water to rinse their mouths and crackers to neutralize the taste of a sample before tasting the next one (Alamu et al., Citation2015). The participation of the subjects in the study was voluntary with their informed consent.

3.4. Sensory evaluation of TSP products

3.4.1. TSP-stew sauce

Eighteen TSP samples were used to prepare sample stews (Figure ). For proper identification of these samples, the stews were coded from AST to RST and prepared over four days: Days 1 and 4 each had four samples tested; Days 2 and 3 each had five samples.

Day 1: AST, BST, CST, and DST

Day 2: EST, FST, GST, HST, and IST

Day 3: JST, KST, LST, MST, and NST

Day 4: OST, PST, QST, and NST

Panelists who did not fully participate over at least three days were removed from the final list. Each remaining participant tasted a minimum of 13 samples. Precisely, one participant had 13 samples; three had 14 samples; 12 tasted all the 18 samples at different testing times.

3.4.2. TSP- egusi soup

Nine TSP samples were used to prepare nine different soup samples. For proper identification, the soups were prepared over two days and labeled from ASP to ISP (nine samples).

Day 1: ASP, BSP, CSP, and DSP

Day 2: ESP, FSP, GSP, HSP, and IST

Panelists who did not fully participate in the sensory evaluation both days were removed from the final list. Each of the remaining 15 participants tested a total of nine samples.

3.5. Statistical analysis

The mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variance of the values were calculated using Statistical Analytical Packages (SAS) software version 9.4. The significant means were separated using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test at 95% confidence level.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Rehydration parameters of TSP samples

Rehydration information on TSP samples before incorporation into the soups and stew sauces is shown in Table . The swelling ratio of the samples ranged from 2.05 for sample BST to 5.39 for BSP, with an overall mean of 2.61. The swelling ratio well above 2.0 indicates that TSP increase in volume (more than doubled) when soaked in water. TSP was reported to absorb at least three times its weight in water (Riaz & Yada, Citation2004). The higher the swelling ratio, the better the TSP when being used as a meat substitute for soup and stew sauces. Zeki (Citation1992) reported that TSP offers not only economic savings but also serves to improve the quality of the product due to the ability to absorb water and fat, which results in a juicier product.

4.2. Sensory properties of tsp-stew

Table shows the results of the sensory evaluation of TSP-stew. The color of all the samples was significantly different (P < 0.05): RST (4.67 ± 0.74) and OST (4.47 ± 0.52) were highly rated; FST (3.31 ± 0.87) and IST (3.31 ± 1.08) showed the lowest ratings. The aroma among the samples was highly significantly different (P < 0.05). Samples PST, OST, and AST were highly rated; MST and IST had average ratings. Sample consistency was also significantly different (P < 0.05). Sample RST was highly rated; IST had the lowest rating in terms of color. Sample taste was significantly different (P < 0.05); RST was highly rated while IST had the lowest rating in terms of consistency. For taste, RST had the highest score that is followed by AST and BST. However, sample IST was the least preferred in terms of taste. The general sample acceptability was also significantly different (P < 0.05). However, OST and RST were the most acceptable samples of TSP stew samples; IST was the least acceptable. It could be that color, aroma, consistency, and taste were the important sensory properties that drive the acceptability of TSP-stew because OST and RST showed ratings above 4.0 on a 5-point hedonic scale for these sensory properties. The results are in close agreement with the findings of Gök, Askın, Özer, and Kılıç (Citation2012) that reports the use of TSP affected the texture, color intensity, firmness, and flavor properties of döner kebab and kebabs manufactured with TSP were the most preferred in terms of taste (P < 0.05).

Table 3. Results of sensory parameters of textured soy protein‒stew sauces

4.3. Sensory properties of TSP- soup

The results of the sensory evaluation of TSP-soup are presented in Table . There were no significant (P > 0.05) changes in the colors of the samples; however, ASP was the most preferred, and DSP had the lowest rating. There was a significant difference in the aroma; ESP scored highest and DSP the lowest. No significant (P > 0.05) difference was observed in the consistency of the samples, but ASP had the highest rating and DSP the lowest. The taste of the samples showed highly significant differences in ratings (P < 0.05). The best-rated samples were ASP, DSP, ESP, and FSP; samples CSP and DSP had the worst ratings. The general acceptability of the samples also showed some significant differences (P < 0.05). The best-rated samples were ASP and GSP; the worst-rated was DSP. It could be that aroma and taste are the significant sensory properties that determined the acceptability of TSP-soup.

Table 4. Results of sensory parameters of textured soy protein–egusi soup)

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the right rehydration of TSP samples gave an excellent swelling ratio and implied that a small quantity could produce enough protein for an average poor household. It is prudent to recommend incorporation of TSP as a meat or fish substitute for the poor households that cannot afford protein from animal sources. For TSP-stew, sample RST with Harvest Innovation Hisolate Texsoy Chunks had general acceptability. For TSP-soup, Harvest Innovation Hisolate Texsoy Crumbles (sample ASP) and ADM Textured Vegetable Protein TVPU–814 CH 12 UNP PRODUCT CODE 165,814 (sample GSP) had general acceptability. TSP could be incorporated as a substitute for meat or fish int both research items to obtain acceptable products and for the improved nutritional quality without affecting their taste. The use of TSP granules in samosa products has been reported without significant differences in sensory attributes (Omwamba et al., Citation2014). The TSP-based soups and stew sauces could help to alleviate the protein malnutrition that is prevalent in most developing countries that cannot afford meat products in their diets. Potential benefits in reducing cardiovascular diseases have been known from the use of TSP and other soy-based foods to replace foods with high animal protein which contain saturated fat and cholesterol.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support received from University of Illinois for the provision of different TSP samples and CGIAR Research Program on Grains, Legumes and Dryland cereals (GLDC) and participation of staff of IITA that participated as sensory panelists.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emmanuel Oladeji Alamu

Alamu Emmanuel Oladeji, a Nigerian, is an Associate Scientist/Food Science and Technology at International Institute of Tropical of Agriculture(IITA), Zambia. He holds a doctorate in Food Chemistry with over 12 years of research experience and strong analytical skills in food science and nutrition and experienced in carrying out nutrition-sensitive agricultural research using different tools and techniques. He has many publications in local and foreign journals to his credit.

Maziya-Dixon Busie

Busie Maziya Dixon, a Swaziland national, is a Senior Scientist with the International Institute of Tropical of Agriculture with headquarters in Ibadan, Nigeria. She has vast expertise and experience in research in the areas of Food Science, Nutrition, Agriculture and Health. She has many publications in local and foreign journals to her credit.

References

- Alamu, E. O., Maziya-Dixon, B., Menkir, A., & Olaofe, O. (2015). Effects of husk and harvesting time on provitamin A activity and sensory properties of boiled fresh orange maize hybrids. Journal of Food Quality, 38(6), 387–12. doi:10.1111/jfq.12158.

- Anderson, J. W., Johnstone, B. M., & Cook, N. (1995). A meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. New England Journal of Medicine, 333, 276–282.

- Asgar, M. A., Fazilah, A., Huda, N., Bhat, R., & Karim, A. A. (2010). Nonmeat protein alternatives that serve as meat extenders and meat analogs. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 9(5), 513{529}.

- Gök, I., Askın, O. O., Özer, C. E., & Kılıç, B. (2012). Effect of textured soy protein and tomato pulp on chemical, physical and sensory properties of ground chicken döner kebab. African Journal of Biotechnology, 11(25), 6730–6738.

- Hoffman, J. R., & Falvo, M. J. (2004). Protein – Which is best? Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 3, 118–130.

- Niaz, K., Zaplatic, E., & Spoor, J. (2018). Extensive use of monosodium glutamate: A threat to public health? EXCLI Journal, 17, 273–278. doi:10.17179/excli2018-1092.

- Omwamba, M., Mahungu, M., & Faraj, K. (2014). Effect of texturized soy protein on quality characteristics of beef samosas. International Journal of Food Studies (IJFS), 3, 74–81.

- Riaz, M. N., & Yada, R. Y. (2004). Texturized soy protein as an ingredient. In R. Y. Yada (Ed.), Proteins in Food Processing (pp. 517–558). England: Woodhead Publishing.

- Savvy Vegetarian Inc. (2018). Soy protein isolate or TVP Pt 1. Retrieved from: https://www.savvyvegetarian.com/articles/textured-vegetable-protein.php.

- Singh, P., Kumar, R., Sabapathy, S. N., & Bawa, A. S. (2008). Functional and edible uses of soy protein products. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 7(1), 14–28.

- Solomon, U., Gabriel, O. O., Henry, E. O., Adrian, I. O., & Anthony, T. E. (2015). Effect of monosodium glutamate on behavioral phenotypes, biomarkers of oxidative stress in brain tissues and liver enzymes in mice. World Journal of Neuroscience, 5, 339–349.

- Torres, N., Torre-Villalvazo, I., & Tovar, A. R. (2006). Regulation of lipid metabolism by soy protein and its implication in diseases mediated by lipid disorders. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 17, 365–373.

- Wild. (2018). TVP: Textured Vegetable Protein - excellent lightweight meat supplement for backpacking. Retrieved from: https://www.wildbackpacker.com/backpackingfood/articles/tvp-textured-vegetable-protein.

- Young, V. R. (1991). Soy protein in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Journal of American Diet Association, 91, 828–835.

- Zeki, B. (1992). Textured soy protein products. technology of production of edible flours and protein products from soybeans. Rome. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin, 97. M-81, ISBN 92-5-103118-5. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/t0532e/t0532e00.htm#con.