?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Mango fruits contribute substantially to the socio-economic wellbeing of fruit value-chain actors in sub-Sahara Africa, but high incidences of post-harvest losses are posing serious threats to the survival and sustainability of the sub-sector. Therefore, this study aimed to provide evidence-based financial analysis of mango chip processing whose capital structure is within the capacity of small-scale processors in Ghana. The study uses a case study approach on a small-scale mango chip facility established at Lower Manya-Krobo district of Ghana. Cost-benefit analysis of investment worth such as net present value (NPV), benefit–cost ratio (BCR) and, internal rate of return (IRR) as well as payback period was used to measure the financial feasibility of mango chips processing. The results indicate that the total capital expenditure to establish a small-scale mango chip enterprise is Gh₵5, 638.60 (US$1,127.72) with an operating cost of Gh₵12, 100 (US$2,400). Using an opportunity cost of capital of 27%, the result reveals an NPV of Gh₵7,392.60 (US$1,478.52), BCR of 1.18 and an IRR of 77%. The payback period is 1 year and 5 months. These financial indicators suggest that investment in small-scale mango chips is profitable and viable. The findings have implications for including small-scale mango chips processing in interventions to partly address mango post-harvest losses in the country for employment creation, especially among the youth and women.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Mango is an important horticultural crop for both domestic and export markets, which contributes significantly to the gross domestic product of Ghana. The mango industry provides employment opportunities to many farmers as well as other value-chain actors, especially women within the mango commodity chain. Besides, the tree fruit is fortified with essential nutrients such as protein, vitamin A, fiber, thiamine and ascorbic acid appropriate for human capital development. Despite this, the mango industry is confronted with high postharvest losses that limit the maximum impact of the sector on the Ghanaian economy. As a result, this study was conducted to explore the possibility of promoting small-scale enterprises that use cheap, viable and efficient postharvest technologies to prolong the shelve life of the mango commodity to meet consumer demands. The result of the study has implications for the promotion of small-scale mango processing technologies to partly address mango post-harvest losses in Ghana for employment creation, especially among the youth and women.

1. Introduction

Mango (Mangifera indica L) is native to the tropical regions which is usually produced for its economic and nutritional significance (Bommy and Maheswari, Citation2016; Okorley et al., Citation2014). Across Africa and Asia, mangoes are regarded as delicacies with the nickname “Fruit of the Gods” or “King of fruits” (Mehta, Citation2017; Reddy & Kumar, Citation2010). In Ghana, the fruit is one of the important non-traditional export crops that contribute significantly to employment creation and poverty reduction in rural and urban economies (Akurugu, Olympio, Ninfaa, & Karbo, Citation2016; Banson & Yawson, Citation2014). The domestic demand of mangoes in Ghana is high while the potential for export is under-exploited as official statistics show an emerging export market in the European Union and other developed economies (Okorley et al., 2014; Zakari, Citation2012). Historically, Ghana’s mango production and export portfolio have increased tremendously from as low as 23,000MT in 1991 to 983, 000MT in 2007 (Yidu, Citation2015). Recent export data shows that the country produced and exported nearly 2,000,000MT of mango fruits, making it the third largest mango supplier to the United Kingdom after Brazil and Peru (Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA), 2017).

Like many African countries, the supply of mangoes in Ghana is seasonal. The production system is characterized by gluts during peak periods (April to June) leading to a large proportion of the fruit going waste before reaching consumers (Akurugu et al., Citation2016; Nyame, Citation2015). Baidoo-William (Citation2017) observed that about 50% of the harvested mango fruits in the country are not consumed or traded mainly due to the high perishability nature of the fruit, poor postharvest handling systems, as well as lack of low-cost and appropriate postharvest management techniques (Reddy & Kumar, Citation2010). The large percentage of mango fruits wasted does not only cost Government in terms of revenue mobilization, but the opportunity to improve smallholder farmers’ income and alleviate poverty in farming communities is also lost (Akurugu et al., Citation2016).

Interventions to transform mango fruits and to reduce high post-harvest losses in mango production in Ghana show low industrial capacity (Akurugu et al., Citation2016). Few large-scale firms (Sunripe, Blue Skies and Integrated Tamale Fruit Company) exist that process mangoes into juice, pulps and ice creams (Okorley et al., 2014; Zakari, Citation2012). The low investment in post-harvest management of mango fruits in the country may be attributed to the high initial capital costs to establish these firms (Banson & Yawson, Citation2014). Besides higher capital requirement, the food safety and standard compliance for some of these mango products (juice and pulp) are usually beyond small-scale business operators who dominate the industrial sector of the country (Asante & Kuwornu, Citation2014; International Trade Center [ITC], Citation2016). As a result, there have been calls for generation and promotion of post-harvest technologies that are cheap, viable and efficient to increase the post-harvest life of the mango commodity to meet consumer demands (Nyame, Citation2015; Wakjira, Citation2010). One of such technologies is to locally produce mango chip value-added products through the development of micro- and small-scale agro-enterprises (International Trade Center, Citation2016; Van Melle & Buschmann, Citation2013; Williams, Babarinsa, & Afolabi, Citation2006). Deepening the utilization of technologies such as mango chip processing technique whose capital structure best suits small-scale operators would contribute to mitigating the seasonal post-harvest losses of the mango fruit sub-sector (Zakari, Citation2012).

Most previous studies on mango processing in Ghana are limited to mango juice (Ampomah-Nkansah, Citation2015; Asante & Kuwornu, Citation2014). The few studies on mango chips, however, did not consider the financial component and feasibility of processing the mango chips. For instance, Oppong, Kumah, and Tandoh (Citation2019) focused on the Physio-chemical quality responses of dried mango chips to different moisture contents, packaged and storage abilities. Similarly, Appiah, Kumah, Idun, and Lawson (Citation2011) also studied the effect of mango ripening on the quality of keitt mango chips in the country. While these studies provided the foundation for mango chips literature in Ghana, little information is available on the financial feasibility of mango chips processing for investment decision-taking. This study, therefore, presents an empirical financial feasibility analysis of mango chip processing technology that would inform investment at the micro-business level to partly address the seasonal postharvest losses within the mango industry by (1) analyzing the costs and returns of mango chips processing for investment decision-making in Ghana, (2) examining the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) of the mango chips processing industry. The findings have implications for reducing mango post-harvest losses through small-scale value addition interventions aimed at employment creation and poverty reduction in Ghana and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa.

2. Literature on financial analysis of mango processing

The common way of assessing the financial viability of agro-enterprise is by the application of investment appraisal analytical tools (Yadav & Yadav, Citation2018). According to Pearce and Susana (Citation2006), various investment appraisal approaches exist, some of which include financial ratios, minimum capital–input ratio, domestic resource cost method, benefit-cost analysis, multi-criteria analysis, among others. However, a review of the literature suggests that cost-benefit analysis (and to some extent financial ratios) is the most ideal methodologies in evaluating the economic components associated with enterprise investments (Ergas, Citation2009). Ergas (Citation2009) further states that cost-benefit analysis is the most important tool that assists investors to make sound and best decisions on investment judgements.

Many empirical studies have applied the cost-benefit approach to analyze the economic returns of many mango value-added products such as juice, pulp and butter (Asante & Kuwornu, Citation2014; Bommy and Maheswari, 2016;Mahalakshmi, Citation1994; Reddy, Citation2010; Reddy & Kumar, Citation2010; Sukla et al., Citation2015) and, less so on mango chip products. For instance, Shukla et al. (2015) employ financial ratio techniques with undiscounted cash flows to evaluate the financial feasibility of mango pulp processing in South Gujarat, India. The results reveal that mango pulp processing is profitable for large-scale firms when compared with medium and small-scale firms. In a similar study, Bommy and Maheswari (2016) also use related financial ratios to estimate the financial viability of various mango value-added products including mango squash, mango jam, mango fruit bar and mango pickle. Even though the study did not include mango chips processing, it concludes that investment in mango product processing is profitable and recommends for more investments in such techniques to curb the seasonal postharvest losses of mango fruit, create more employment and increase farmers’ income. Financial indices used in both studies were capital, expenses, income and asset ratios to ascertain the viability of mango processing in the study areas.

In another study, Reddy and Kumar (Citation2010) used discounted cost-benefit techniques such as net present value, benefit–cost ratio, internal rate of return, and payback period to evaluate the financial feasibility of mango pulp processing plants in Chittor district of India. The authors observe that investment in mango pulp processing is financially rewarding and therefore recommends for more policy in the sector. Karthick et al. (2013) in an appraisal of mango pulp processing in Tamil Nadu, India also use similar financial techniques and conclude that processing of mango pulp is profitable and viable in the district. In a related study for Ghana, Asante and Kuwornu (Citation2014) similarly used the cost-benefit approach to compare the financial viability between pineapple-mango juice and pineapple juice. The authors report higher financial viability for pineapple-mango juice compared with pineapple juice alone in the study area.

Inferences from the work of Bommy and Maheswari (2016) and Shukla et al. (2015) suggest that the cost and benefits captured were undiscounted and did not consider the timing at which the cash inflows and outflows were incurred and received, respectively. Hence, result from such studies might not be a true reflection of the worthiness of the investments undertaken. According to Wongnaa and Awunyor-Vitor (Citation2013), for an investment with multiple year lifespan, as in the case of the mango processing, most of its benefits and costs are to be realized in the future at different times. For that matter, the worthiness of such investment is better assessed by discounting future costs and benefits to their present values for accurate valuation and comparison. Similarly, Ergas (Citation2009) and Björnsdóttir (Citation2010) report that discounted cash flows in the cost-benefit analysis are more reliable and offer a robust ground for investment judgement. Such an approach allows comparison of future cash benefit with an initial investment to ascertain whether future streams of benefits are justifiable of the investment undertaken in the present day. Besides, the discounting cost–benefit analysis also helps to account for uncertainties and risks, price inflation as well as the opportunity cost of money that tends to have a considerable effect on the returns and costs of investments with a longer lifespan (Gittinger, Citation1996).

Even though studies such as Reddy and Kumar (Citation2010), Karthick et al. (2013), and Asante and Kuwornu (Citation2014) considered the discounted benefit and cost approach, the analyses were done for mango products (e.g., juice, pulp, butter, etc.) that demand large-scale investments and high food quality standards. Such a restricted analysis has the tendency to limit investment in the micro- and small-scale fruit processing enterprises due to difficulties in satisfying the capital and food safety demands (Leid & Salvosa, Citation2008). Besides, no attempt was made to analyze the economic viability of mango chips processing, whether using discounted or undiscounted cost–benefit analysis. Against this background, the current study uses the discounting measures of cost-benefit analysis to analyze the financial viability of mango chips processing whose capital requirement and food safety systems are within the remit of small-scale business operators in Ghana.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Description of study area

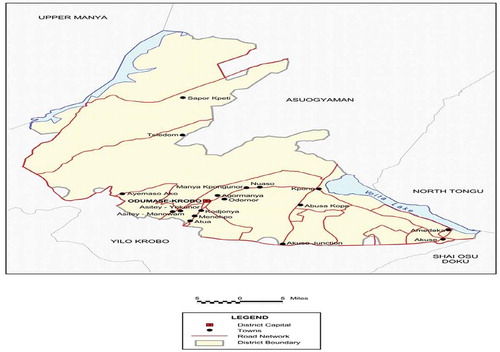

The study was conducted in the Lower Manya Krobo municipality in the Eastern region of Ghana. The municipality lies between latitude 6.05° and 6.30° North and longitude 0.08° and 0.20° West with an altitude of 457.5 m above sea level. Lower Manya Krobo shares boundaries with Upper Manya Krobo district in the north-west, Asuogyaman district in the northeast, North Tongu district in the Southeast and in the South by Dangme West and Yilo districts (Figure ). An area of 304.4 square kilometers is covered by the municipality, with a population density of 293.2 persons per square kilometer. The municipality has a total population of 89,246 with a household population of 87,649 having an average family size of four persons per household. About 35% of the total households’ in the municipal participate in agriculture and its related activities. Crop farming dominates the agricultural production sector but tree crop farming such as mango and livestock management is also high.

The Lower Manya Krobo municipality has rainfall ranges from 900 mm to 11,500 mm annually with relative humidity high in the wet season and low in the dry season. The municipality has a bimodal rainfall distribution with the major season from March to September. The minor season also spans from October to December. The Municipality has the semi-deciduous and savannah ecological zone characteristics suitable for tree cultivation, such as Mango, Neem, Ceiba and Acacia.

Official statistics suggest that nearly 30% of the mango fruits cultivated in Ghana is produced in the Eastern region, of which Lower Manya Krobo contributes significant proportion. Mango production is an important source of livelihoods of the populates in the Manya Krobo municipality since it represents the most important tree crop cultivated in the municipality. The tree has both ecological and economic potential in the area.

3.2. Method of data collection

Both primary and secondary data were used for the study. Primary data were obtained mainly from the administration of structured questionnaires through personal interview. Only one small-scale mango chip processing firm was found in the Eastern region and was located in the Lower Manya Krobo municipality. In fact, to our best of knowledge as at the time of this study, we found only one smallholder mango chip processing firm located in the Lower Manya Krobo municipality in the entire country. Consequently, a case study approach was adopted for the administration of the structured questionnaire on the firm. Information captured includes capital expenditure to establish a mango chip processing firm, annual operating costs and the returns from sales of the final product. The data collected were limited to the 2017/2018 production and marketing season. The main equipment used by the firm is the mango chips dehydrator which has a lifespan of five (5) years. Hence, the cost and returns associated with the mango chip processing dehydrator were projected for 5 years to cover the lifespan of the dehydrator. All costs and benefits are valued on the full capacity of the dehydrator to process 240 kg of mango fruits in a year.

The major capital costs captured include land, building, dehydration machine, power plant/generator, tools and equipment. Labor cost, water, raw mango fruits, packaging materials, transportation and distribution of raw and processed fruits, electricity, and maintenance costs were captured under operating costs. The data on revenue were restricted to only the revenues accrued from the sales of mango chips in urban centers such as Accra and Koforidua. Even though the dehydrator machine could be used to dry other fruits such as plantain, banana, among others, the current operation is limited to only mango chip processing. Hence, the costs and returns of the equipment are limited to mango chips processing.

3.3. Analytical procedure

Discounting measures of investments worth including net present value, the internal rate of return

and the benefit–cost ratio

were used to analyze the economic viability of mango chips dehydrator technology in Ghana. However, an undiscounted method (payback period) was also used to determine how quickly the mango chips dehydrator generates enough funds to cover initial capital investments. Sensitivity analysis was also carried out to ascertain the changes in the viability measures given changes in some key variables in mango chip processing. The analytical tools are described below;

3.3.1. Net present value (NPV)

The NPV simply refers to the present worth of the net cash flow of a firm. It is, therefore, the difference between the present value of an investment cash inflows (benefits) and the present value of its cash outflows (costs) at a given discount rate (Björnsdóttir, 2010). The discount rate used in analysis is usually estimated from the opportunity cost of capital. In this context, the opportunity cost of capital denotes returns on the last or marginal investment made that exhausts the last available capital. Practically, the exact value to represent the opportunity cost of capital is problematic; hence, the lending rates of commercial banks within a project’s locality (Björnsdóttir, Citation2010) are used as an approximation. Mathematically,

is expressed as:

where denotes cash outflows per year, t;

is cash inflows per year, t; n and r are number of years of the investment (1 to 5 years) and discount interest rate, respectively.

3.3.1.1. Decision rule

The selection criterion is to accept all independent projects with of zero or greater, at a specified discount rate. One problem of the NPV is that it cannot be calculated without a satisfactory estimate of the opportunity cost of capital. It is preferred in choosing among mutually exclusive projects.

3.3.2. Internal rate of return (IIR)

This measure of investment worth () is known as the rate of discount which applies to an investment’s cash flow and produces a zero

. Mathematically, it is given as:

Where

Lower discount rate

Higher discount rate

Net present value

3.3.2.1. Decision rule

Accept projects with greater than the interest rate charged by lending banks or prevailing in the open market in the study area. Determination of the exact

is quite laborious that involves via trial and error method. Various discount factors are used until one that equates the net present value almost zero. This is done by increasing the discount factor that renders that net present positive and decreasing it when the net present value is negative. The actual discount factor lies between these two discount factors.

3.3.3. Benefit–cost ratio

The compares discounted costs and benefits of the investment cashflows. Results from the BCR are similar to the NPV, but the former measures the relative profitability of the investment while the latter accounts for total net benefits. BCR, therefore, becomes more relevant over the

when investors are interested in knowing the generated profitability from a cedi (dollar) invested in the business (Gittinger, Citation1984). Mathematically, the BCR is given by:

3.3.4. Payback period

The payback period estimates the number of years an investment used to repay the initial capital invested. In other words, it is the estimated length of time from the beginning of the project until the net value of the incremental production stream reaches the total amount of capital investment. Cash inflows for the PB are undiscounted hence does not consider the time value of money. The payback period is mathematically expressed as;

3.3.5. Sensitivity analysis

The essence of conducting sensitivity analysis is to investigate the impact of changes in key variables of the investment’s NPV, IRR, BCR and payback period (Saltelli et al., Citation2008). The sensitivity analysis tries to measure the effect of achieving investment objectives when the assumptions behind cash flows vary wholly or partially. The analysis, therefore, brings to the fore the consequences of changes in the cash flow and what remedies to be adopted in the event of likely project failure (Csimingad & Iloiu, Citation2009). In this study, the sensitivity analysis was done for a 10% decrease in revenue, a 10% increase in operating cost and a 10% increase in the opportunity cost of capital were considered. The choice of the 10% change in key variables of the investment is informed of the annual inflation rate of about 10% in the Ghanaian economy (Ghana Statistics Service, Citation2019)

3.3.6. Justification of techniques used

The most widely used discounting measures in project appraisal are either the NPV or IRR (Csimingad & Iloiu, Citation2009). However, Conejos and Manzana (2016) reported that it is important to consider a combination of these techniques. This is because each of these criteria has an advantage and disadvantage in empirical applications and the use of more than one tool especially, for a single enterprise evaluation is helpful. For example, Brealey, Myers, & Allen (Citation2011) cautioned that reliant on IRR alone has a tendency to mislead investors in choosing investments. The authors observed that for projects that are mutually exclusive or independent, the use of IRR may favor investments that yield profit faster but may have lower NPV. In order to offset the weakness of each other and also improve the reliability and robustness of results from the financial analysis, it is customary to apply a combination of the tools. In this study, therefore, all three popular discounting measures (NPV, IRR and BCR) and undiscounted payback period are used to appraise the mango chips processing technology.

3.4. Methods of data analysis

Descriptive analytical tools such as frequency table and means were used to characterize the cost and returns of mango chip processing. On the other hand, the discounted measures of investment appraisal explained previously were also used to analyze the data.

3.5. Assumptions

To apply the measures of investment worth (NPV, BCR, IRR and the payback period) the following assumptions were made in the costs and benefit projections. Grounds for the assumptions were based on data, inflation rates and prices obtained from the study area, private and governmental agencies (see Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2019; Trading Economics, Citation2019). Mango fruits are produced in two seasons; the major season spans for 3 months and the minor is limited to 2 months. As a result, the mango chip equipment only operates for 5 months in a year. Other major relative assumptions used in the financial analysis are:

All the amounts are quoted in Ghana Cedi (GH₵) and convert to dollars based on official foreign exchange rates. The base prices for the 2017/2018 mango production season were used for the study.

Revenues and costs are projected over a period of five (5) years based on the life span of the dehydration machine.

The mango chips dehydrator is expected to operate at full capacity for the entire investment period. Therefore, the expected dry mango chips produced are estimated as 160 kg per production cycle.

The cost of capital is 27%. This is based on the average interest rates offered by commercial banks in the country. It is assumed that processors used borrowed funds to set up and operate the dehydrator equipment.

Labor cost is estimated to increase by 10% each year based on the trend of minimum wage in the country.

Cost of electricity is assumed to increase by 5% each year based on the past trend increase in electricity bills.

Cost of transportation of mango fruits to the firm and distribution was estimated to increase by 10% each year based on past increments in transportation fare.

Cost of water is estimated to remain constant for the first 3 years and increase by 5% in the fourth and fifth year based on the rare increment in the cost of a liter of water in the country.

Cost of gloves, packaging materials, and maintenance was assumed to be affected by inflation rate with current inflation rates at 9%.

Rent on land is assumed to increase by 10% each year based on the past land rent increment.

Cost of mango fruits based on past price trend was estimated to increase by 5% each year.

Price of mango chips is also assumed to increase by 10% based on the past price trend of mango chips sold in the country.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Cost analysis of mango chips processing

In this study, the total cash outflows are sub-divided into capital expenditure and operating or maintenance costs. The capital expenditure is the initial cost incurred to establish a small-scale mango chip processing firm in year zero. It comprises the purchases of dehydration machine, furniture, rubber sealer, creates, knife, chopping board, airtight containers, tray and bowls. These assets are expected to last for the entire life span of the dehydration machine which is the main equipment for mango chip processing. A 10% contingency cost allowance was also made to cater for any unforeseen or unaccounted costs for the establishment of the investment (Table ). The data revealed that an estimated cost of Gh₵5,638.60 equivalent to US$1,127.72 is required to establish a small-scale mango chip processing with a dehydrator of five-year lifespan. The highest cost component of the mango chips capital expenditure is an investment in production and storage 10 ⨰ 12 ft room (52.8%) before the purchase of a dehydration machine (26.4%). The overall capital demand is consistent with the figure (less US$100, 000) reported by the World Bank for classification of small-scale enterprises in Africa (Ankomah, Citation2012; Oppong, Owiredu, & Churchill, Citation2014).

Table 1. Capital expenditure of mango chip processing plants

Tables and illustrate the actual and projected operating costs, respectively, for the entire lifespan of the mango chip processing investment. The operating costs represent the costs incurred after the capital expenditure period from year one to the fifth year of the mango chip investment. Generally, the reported operating costs of Gh₵12,100 (US$2,400) include input, management and machinery servicing or maintenance costs. Cost of raw mango fruits which contributes about 49.5% of the total operating cost is considered as the highest among the inputs. The projected operating costs are incremental over the five-year investment period based on the assumptions made above. One crucial factor that causes these price variations among the years is due to price inflation in Ghana. Historically, the prices of goods and services in Ghana have always experienced high inflations with an annual average of 10% (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2012).

Table 2. Annual operating costs

Table 3. Projected operating cost for entire mango chip investment

The mango chips dehydrator is capable of processing 24 kg weight of mango fruits per day. A kilogram of mango fruit costs Gh₵1. 60 (US$0.32). This implies that at full capacity, the dehydrator processes 480 kg of mango fruits per month (20 days) which costs Gh₵768 (US$153.6). Therefore, for the 5-month processing cycle, approximately 2400 kg mango fruits are processed with an annual cost of Gh₵3,840 (US$768). For labor, the mango chips dehydrator is one man-operator machine with two assistances. Prevailing labor cost per person per day is GH₵15 (US$3.0) for 5 days in a week. Hence, the total cost of labor for the three persons per month and the 5-month production cycle are Gh₵900 (US$180) and Gh₵4, 500 (US$900), respectively.

The mango chips dehydration machine is powered by electricity. Therefore, the total electricity cost to dehydrate the 2400 kg of mango fruits for the 5-month period is estimated at Gh₵850 (US$170) (Gh₵0.354 (US$0.071) per 1 kg). Water is also critical in the processing of mango chips. As noted earlier, water is used to wash the mango fruits before dehydration. A total of 7,200 liters of water with each litre costing Gh₵0.0167 (US$0.0034) estimated at Gh₵120 (US$24) per cycle is used in the dehydration processing. Meanwhile, the transportation cost for the 2400 kg fresh mangoes from farm gates to the processing facility is estimated at Gh₵160 (US$32) (Gh₵0.067 (US$0.013) per kg) per the production cycle. Other operating costs incurred are hand gloves for handling and cutting of mango fruits into appropriate sizes for drying. A pair of new gloves costs Gh₵0. 50 (US$0. 10) is used every day for processing. As such, for the 5-month processing cycle, a pair of 100 gloves is used with a total cost of Gh₵50 (US$10).

After the dehydration process, the mango chips are packed in a well-sealed rubber material to prevent contact with atmospheric moisture and air. A single rubber material with size 150mmX100mm is used to package 50 g of dried mango chips at a cost of GH₵0.20 (US$0.04) per package. Meanwhile, the labelling cost per material is also valued at GH₵0.10 (US$0.02). Therefore, the unit packaging cost of a 50 g mango chip is Gh₵0. 30 (US$0. 06). This implies that Gh₵960 (US$192) will be required to package and labelled the 3200 pieces of the 50 g of mango chips produced in a cycle.

An important post-production activity is marketing or distribution of the mango chips to local retail stores in urban markets for sales. Currently, the mango chips processing at Lower Manya Krobo municipal targets the urban domestic markets including Accra and Koforidua. The distribution costs, which include transportation, taxes and search costs are estimated at GH₵80 (US$16) for the total 3200 50 g of the mango chips produced in a cycle. Other important recurrent costs incurred include rent on land and maintenance of the dehydration machine. The rent paid on land for the construction of a 10 × 12 foot store to accommodate all inputs, dehydration machine and processed mango chips before the sale was Gh₵20 (US$4) per month. Therefore, the total rent is Gh₵240 (US$48) for 1 year, whether production is in place or not. To ensure continuing operation at full capacity, the dehydration machine is constantly serviced by changing engine oil, bolts and nuts as well as general servicing. An estimated Gh₵50 (US$10) per month is used to maintain the machine for the entire production cycle.

4.2. Revenue analysis

The dehydration machine has a capacity of producing 1.6 kg mango chips per day, which are packed into a 50 g rubber material for transportation to marketplaces. Per this output, the implication is that 32 pieces of 50g-packed mango chips are produced on a daily basis. The current price per unit of the 50g-packed mango chip is GH₵5 (US$1) which yields GH₵160 (US$32) worth of mango chips per day. Therefore, the total quantity of 50g-packed mango chips, processed is 3,200 (160 kg) corresponding to GH₵16, 000 (US$3,200) worth of mango chips in a productive year. From the assumptions made, the price of mango chips is expected to increase by 10% to match the rise in production costs. Illustrated in Table are the revenues and their projections over the entire investment life.

Table 4. Revenue projections

4.3. Financial viability analysis

Illustrated in Table are the discounted and undiscounted cash inflows, outflows used to calculate the net present value, benefit–cost ratio, internal rate of return, and payback period of the mango chips investments. The adopted discount rate of 27% is the opportunity cost of capital representing the average interest rate charged on loans by commercial banks in Ghana. The discount rate used to account for the time value of money (TVM) by reducing future streams of cash inflows and outflows to their present values. In this regard, the total discounted cash inflow is Gh₵48,244.11 (US$9,648.82). Similarly, the discounted cash outflow is estimated at Gh₵40,851.51 (US$8,170.30).

Table 5. Undiscounted and discounted cash outflows, inflows and financial analytical results

Therefore, the data shows a net present value of Gh₵7,392.60 (US$1,478.52) for mango chips processing in the study area. Since the NPV is positive, it denotes that investment in mango chip processing is profitable and viable in the study area. The NPV also gives an indication of the net worth of the investment over its entire life cycle in present values. The reported BCR (1.18) implies that for every Ghana Cedi or dollar invested in small-scale mango chip processing, there will be a return of Gh₵1. 18 or US$0. 24 on the amount invested. The BCR is greater than one and this depicts that the mango chip investment is financially viable since derived benefits exceed costs incurred. This BCR value is compared with the study of Wongnaa and Awunyo-Vitor (2013) on profitability analysis of cashew plantations in Ghana, in which a BCR greater than one (1.13) was the basis of the conclusion that the cashew project was profitable and viable to invest.

Meanwhile, the internal rate of return which suggests the average earning power of the mango chip investment is reported to be 77% per annum. The IRR denotes the highest rate that the mango chip investment could yield from the resources employed if the investment is to recuperate its capital investment and maintenance costs and still break even. Given that the opportunity cost of capital (27%) is lower than the calculated IRR, the study concludes that investment in mango chip processing is financially viable and profitable. In a related study, Asante and Kuwornu (Citation2014) report an IRR of 23% greater than the discount rate of 21% and concludes that investment in pineapple juice processing in Ghana is profitable and viable.

Lastly, the data shows a payback period of a year and 5 months which proves the liquidity nature of the mango chip investment. Even though the payback period is non-discounting and does not consider the time value of money, the tool gives an indication of when the investment will generate enough funds to repay capital investments of the business.

4.4. Sensitivity analysis

The response of the investment to production risks such as an increase in costs and a decrease in revenue shows mixed results (Table ). With a 10% decrease in expected revenue, the NPV reduced drastically to Gh₵2, 568.19 (US$513. 64), BCR to 1.06 and an IRR of 46%. Even though the financial indicators were reduced as compared to the original calculations, the investment is still viable and profitable since the net present value is positive. Similarly, the benefit–cost ratio is greater than 1 with an internal rate of return more than the opportunity cost of capital in the country. However, the drastic changes in the viability tests provide a glimpse of how sensitive the mango chip processing investment is for a reduction in revenue. Prospective investors may, therefore, have to adopt management strategies that will maintain good returns in operating a small-scale mango chip processing firm.

With a 10% increase in operating costs, the reduction in the profitability measures was relatively smaller compared with the 10% reduction in revenue. The NPV marginally reduced to Gh₵3,871.31 (US$774.26) while BCR and IRR reduced to 1.09% and 54%, respectively. Similarly, there was a slight reduction in profitability indicators when the costs and benefits were subjected to a 10% increase in the opportunity cost of capital. In all the scenario analyses, profitability measures from the investment were generally stable and profitable for the investment.

4.5. Strength, weakness opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis

The result of the mango chips SWOT analysis is shown in Table . High quality of processed mango chip products was ranked first, probably because there were no differences in dry mango chips and fresh mango fruits according to the processor. Another strength of the mango chip industry includes the availability of dehydration equipment for easy access by all investors.

Table 6. Sensitivity analysis of mango chips processing

Table 7. SWOT analysis of mango chips processing

However, the limited capacity of the dehydrator equipment was reported as a key weakness associated with the mango chips processing business. This is so because the dehydration machine spends long hours to process a small quantity of mango chips daily. Despite this problem, the business has a huge opportunity which remains unexploited in the country. The processor reports that fewer large-scale mango chip firms in Ghana operate for exportation with none supplying to the domestic markets. Hence, the supply of mango chips is unable to meet local demand, especially during the off-season mango production periods resulting in minimal competition among processors. However, the threat of seasonality in the supply of mango fruits, because production is reliant on rainfall, suggests that production of mango chips cannot be all year round. The consequences of capital expenditure and other sunk costs incurred in the business are enormous. Other important threats that seem to negatively affect the mango chip business are inconsistent power supply, difficulties in accessing parts of the equipment and certification of agro-processed production in the country.

5. Conclusions

The study applied discounted and undiscounted investment appraisal tools to assess the financial feasibility of small-scale mango chips processing in Ghana. The cost involved in operating the firm includes capital expenditure and operating cost. The financial feasibility was determined using net present value, benefit–cost ratio, internal rate of return and payback period.

With a discount rate of 27%, the empirical result shows mango chip processing had an NPV of Gh₵7,392.60 (US$1,478.52), BCR of 1.18 and an IRR of 77%. The findings suggest that investment in small-scale mango processing in the study area is profitable and viable. Further, the study shows an initial capital outlay of Gh₵5,638.60 (US$1,127.72) which can be recovered within 1 year and 5 months. The capital cost suggests that the mango processing business falls within the remit of small- and micro-scale operators. However, the sensitivity analysis suggests that the mango chip investment is slightly vulnerable to variations in revenue and operating costs.

The study provides the following recommendations. First, the supply of raw mangoes is seasonal and often experience gluts during peak periods. To take advantage of this opportunity, the mango chips dehydrator should be operational for 30 days (also at night) instead of the current 20 days per month in order to process large volumes of mango fruits. This, in turn, equalizes the shortfall of mango supply during the off-season with mango products for consumption. In this respect, the problem of perennial post-harvest losses associated within the mango industry to some extent will be minimized. Second, the government should make efforts to promote investments in small-scale mango chips processing for job creation, particularly for the youth and women in Ghana. In this respect, the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI) should include mango chips processing in its entrepreneurship programs for mentorship and investment. Further, mango chips processing is not popular in the country; therefore, the Food and Drug Board Authority should provide education and guidelines to mango chips processors on safety standards requirement so as to access high-value market.

The results of the study also provide an important addition to the literature on mango chips processing in Ghana. To our best of knowledge, no comprehensive study has been conducted that elicit the financial potential of mango chips processing in Ghana and Africa at large. However, to consolidate and make the recommendations from this study more relevant, technical feasibility studies on the quality of mango chips, its market share and size need research attention.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Faizal Adams

Faizal Adamsis a lecturer at the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He holds Ph.D in Agricultural Economics from the same University. Dr Adams’ research interest includes rural livelihood systems, gender and health, food security and poverty analysis, climate change mitigation, sustainable agriculture, livestock economics, agribusiness development, agribusiness financing and project appraisal.

Kwadwo Amankwah

Kwadwo Amankwah, is a lecturer at the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. He holds Ph.D in Agricultural Extension, Communication and Innovations. Dr Amankwah’s research interest is in examining the transition from knowledge-based education to competency-based education and consequences on employment generation by graduates.

Emmanuel Patrick Honny

Emmanuel Patrick Honny, Douglas Kofi Peters, Barnie Juliet Asamoah, and Bismark Benjamin Coffie are graduate students from the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. They hold BSc. Agribusiness Management from the same University.

References

- Akurugu, G. K., Olympio, N. S., Ninfaa, D. A., & Karbo, E. Y. (2016). Evaluation of postharvest handling and marketing of mango (Mangifera Indica) in Ghana: A case study of Northern Region. Journal of Research in Agriculture and Animal Science, 4(5), 4–16. ISSN: 2321-9459

- Ampomah-Nkansah, E. (2015). Postharvest quality issues in the local marketing of semi-processed mangoes: A case study of three sub-metros in Greater Accra region. Thesis submitted to the award of Master of Philosophy in Postharvest Technology, Kumasi: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

- Ankomah, K. M. (2012). Promoting micro and small-scale industries in ghana for local development: A case study of the rural enterprises project in Asante Akim South District Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Kumasi, Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Appiah, P., Kumah, P., Idun, I., & Lawson, J. R. (2011). Effect of ripening on eating of ‘keitt’ mango chips. Acta Horticulturae, 911, 547–554.

- Asante, M. K., & Kuwornu, J. K. M. (2014). A comparative analysis of the profitability of pineapple-mango blend and pineapple fruit juice processing in Ghana. Agroinform Publishing House, 8(3), 33–42.

- Baidoo-William, J. (2017). Profitability of mangoes and a $66 yearly loss. Reterived from http://tv3network.com/health/profitability-of-mangoes-and-a-66m-yearly-loss

- Banson, K. E., & Yawson, A. E. (2014). Socio-economic impact of fruit flies control in mango production in Ghana, evidence from “Manya Krobo”. Journal of Agriculture Science and Technology, 454–463. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266080477/

- Björnsdóttir, A. R. (2010). Financial Feasibility Assessments. Building and Using Assessment Models for Financial Feasibility Analysis of Investment Projects (Doctoral dissertation). University of Iceland.

- Bommy, D., & Maheswari, S. K. (2016). Preserved products from mango (mangifera indica) and its financial analysis and beneficiaries cost ratio. International Journal of Current Research and Academic Review, 3, 67–73.

- Brealey, A. R., Myers, S. C., & Allen, F. (2011). Principles of coorporate finance (10th Eds). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Irwin.

- Csimingad, D., & Iloiu, M. (2009). Project risk evaluation methods-sensitivity analysis. Annals of the University of Petrosani. Economics, 9(2), 33–38.

- Ergas, H. (2009). In defence of cost-benefit analysis. The Australian National University, 3(1), 181–193.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2019). Consumer price index (CPI). Newsletter Series. Retrieved from https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/marqueeupdater/CPI_Newsletter%20May%20%202019.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2012). Ghana living standard survey: report on the fourth round (GLSS4), 1998/99, Accra-Ghana. doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Gittinger, J. P. (1984). Economic analysis of agricultural products. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Gittinger, J. P. (1996). Economic analysis of agricultural projects (2nd ed.). Baltimore, London: John Hopkins University Press.

- International Trade Center. (2016). Fruit processing boost Ghana’s fruit industry. Retrieved from http://www.intracen.org/itc/blogs/market-insider/Fruit-processing-boosts-Ghana-fruit-industry/

- Leid, J. B., & Salvosa, C. R. (2008). Assessment of government-assisted fruit processing enterprises in Nueva Vizcaya. Research Journal, XV(1&2), 39–44.

- Mahalakshmi, S. P. (1994). Mango butter Financial Feasibility Analysis: Value Added in the Chittor District, Andhra Pradesh, India. A Thesis Submitted at Kansas State University for the Award of Master of Agribusiness, USA.

- Mehta, I. (2017). History of mango – ‘King of fruits’. International Journal of Engineering Science Invention, 6(7), 20–24.

- Nyame, B. (2015). Quality of keitt mango chips as affected by method of drying, package and storage periods (Master’s thesis). Ghana: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

- Okorley, E. L., Acheampong, L., & Abenor, T. E. (2014). The current status of mango farming business in ghana: A case study of mango farming in the dangme west district. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science, 47, 73–80.

- Oppong, D. A., Kumah, P., & Tandoh, P. K. (2019). Physio-chemical quality responses of mango chips dried to different moisture contents, packaged and stored for six months. Advances in Research, 18(10), 1–14. doi:10.9734/AIR/2019/46296

- Oppong, M., Owiredu, A., & Churchill, R. Q. (2014). Micro and small scale enterprises development in Ghana. European Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance Research, 2(6), 84–97.

- Pearce, D. A. G., & Susana, M. (2006). Cost-benefit analysis and the environment: Recent developments. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. ISBN 9264010041.

- Reddy, K. V., & Kumar, P. (2010). An economic appraisal of mango processing plants of Chittoor District in Andhra Pradesh. Industrial Journal of Agriculture Economics, 65(2), 277–297.

- Saltelli, A., Ratto, M., Andres, T., Campolongo, F., Cariboni, J., Gatelli, D., Saisana, M., & Tarantola, S. (2008). Global sensitivity analysis: The primer. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shukla, R., Chaudhari, G., Joshi, B., Leua, A. K., & Thakkar, R. G. (2015). An economic analysis of mango pulp processing in south gurajat. Ind. Agril. Mktg., 29(1).

- Trading Economics. (2019). Ghana inflation rates. Retrieved from https://tradingeconomics.com/ghana/inflation-cpi

- Van Melle, C., & Buschmann, S. (2013). Comparative analysis of mango value chain models in Benin, Burkina Faso and Ghana. In A. Elbehri (Ed.), Rebuilding West Africa’s food potential (pp. 324). Adapppt, Zeist. FAO/IFAD. available at www.fao.org/3/i3222e/i3222e10.pdf

- Wakjira, M. (2010). Solar drying of fruits and windows of opportunities in Ethiopia. African Journal of Food Science, 4(13), 790–802.

- Williams, J. O., Babarinsa, F. A., & Afolabi, I. S. (2006). Mango chips production using multi-purpose drier. Raw Materials Update, 6(2), 30–31.

- Wongnaa, C. A., & Awunyo-Vitor, D. (2013). Profitability analysis of cashew production in wenchi municipality in Ghana. Bots. Journal of Agriculture and Applied Science, 9(1), 19–23.

- Yadav, D., & Yadav, A. (2018). Cost benefits ratio of organic horticultural products and comparison with conventional products. International Journal of Advanced Biological and Biomedical Research, 7(1), 95–102. doi:10.18869/IJABBR

- Yidu, P. K. D. (2015). The Political Economy of Export Crops in Ghana: A study of the Mango Industry. A Thesis Submitted at the University of Ghana for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Degree, Ghana.

- Zakari, A. K. (2012). Ghana national mango study: Support of the PACT II program and the international trade centre (Geneva). Accra.