?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

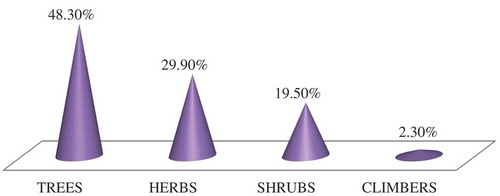

Medicinal and aromatic plants are playing remarkable role in primary health care of human and livestock. This study was conducted in three districts of Eastern Hararghe to identify status and utilization of medicinal and aromatic plants. In the inventory, total of 87 plant species belonging to 50 families were recorded from the study areas distributed in wild, farmland, home gardens and roadsides. Of which 72 (82.8%) were identified for their medicinal value and the rest 15(17.2%) were utilized as both medicinal and aromatic. Fabaceae (18.75%) was the most species‐rich family in the plants used for medicinal purpose. In the medicinal and aromatic plant categories family Lamiaceae and Rutaceae accounts the highest species richness. The average Shannon diversity index (H’) of medicinal plants were 3.68 whereas 2.32 were for medicinal and aromatic plants in the three study areas. ICF value of the identified MAPs used to treat 17 frequently occurring human and 11 livestock health problems showed that the selection is based on well-defined criteria. The most frequently utilized plant parts of the identified plants were the leaf (52.9%), followed by the roots (18.4%) and bark (17.2%). The route of administration for prepared traditional medicine were oral (56%) followed by external application (17%) and nasal (12%). The majority of medicinal and aromatic plant growth forms were identified as trees (48.30%), herbs (29.90%, shrubs (19.50%) and climbers (2.3%). Anthropogenic activities and natural factors were the most prominent factors responsible for reduction of medicinal and aromatic plants in the study areas.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Medicinal an aromaic plants are playing a remarkable role in the primary health care of human and livetock in the Eastern Hararghe. These plants were distributed in wild, farmlands, homegardens and roadsides. The majority of the plants were identified for their medicinal and the others were utilized as both medicinal and aromatic. Fabaceae was the most species rich family in the medicinal plant category.

The most frequently utilized plant parts of the idenified as medicinal and aromatic were the leaves followe by roots and barks. Conservational awreness should be created for the local peoples for better future utilization of medicinal and aromatic plants of the area. In addition, further scientific investigation is required on the phytochemical properites and efficacy of the frequently utilized plant species.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, it is estimated that up to 70,000 species are used in folk medicines (Farnsworth & Soejarto, Citation1991). The number of medicinal and aromatic plant species varies in different countries which makes determining exactly the number of all medicinal and aromatic plant species used worldwide impossible. However, it can be stated, that at least every fourth plant is in use, a calculation based upon the estimated total number of 300–350,000 flowering plants (Lange, Citation2004).

The numbers of medicinal and aromatic plant species used in some regions are impressive: In India, which is said to have probably the oldest, richest and most diverse cultural traditions in the use of medicinal plants, about 7,500 species are used in ethnomedicines (Shankar & Majumdar, Citation1997) which is half of the country’s 17,000 Indian native plant species. In China, the total numbers of medicinal plants used in different parts of the country add up to some 6,000 species according to Xiao (Citation1991). Of these, approximately 1,000 plant species are commonly used in Chinese medicine, and about half of these are considered as the main medicinal plants (He & Sheng, Citation1997). In Europe with its long tradition in the use of botanicals, about 2,000 medicinal and aromatic plant species are used on a commercial basis (Lange, Citation1998). In Spain, it is estimated that 800 medicinal and aromatic plant species are used of which 450 species are associated with commercial use (Blanco & Breaux, Citation1997; Lange, Citation1998). In Africa, over 5,000 plant species are known to be used for medicinal purposes (Iwu, Citation1993).

Ethiopia is rich in biodiversity with presence of rich plant diversity. Medicinal plants are distributed all over the country. In the country, plants have been used as a source of medicine for a long to treat different ailments. Traditional medicine has become an integral part of the culture. About 80% of Ethiopians depends on traditional medicine for health care and more than 95% of traditional medicinal preparations are of plant origin (Kassaye, Amberbir, Getachew, & Mussema, Citation2006). There are about 887 plant species recorded as having medicinal uses for people. The majority of the medicinal plants are herbs, followed by shrubs and trees. Twenty four (2.7 per cent) of the medicinal plant species are endemic to Ethiopia, and most are found in the wild. Therefore, the threats and trends for medicinal plants are similar to those for the forest plant species (Institute of Biodiversity Conservation [IBC], Citation2009). According to Kelbessa, Demissew, Woldu, and Edwards (Citation1992) and Edwards (Citation2001), habitat and species are being lost rapidly as a result of the combined effects of environmental degradation, agricultural expansion, deforestation and over harvesting of species. There is no organized cultivation of plants species for medicinal purposes in Ethiopia except few aromatic species. The reason for this is that the quantities of medicinal and aromatic plants traded are very small, and there is no organized large scale value addition and processing (Bekele, Citation2007). Therefore, this study was conducted to assess current status, utilization and associated challenges to medicinal and aromatic plants in Eastern Ethiopia.

2. Materials and methodology

2.1. Location of the study area

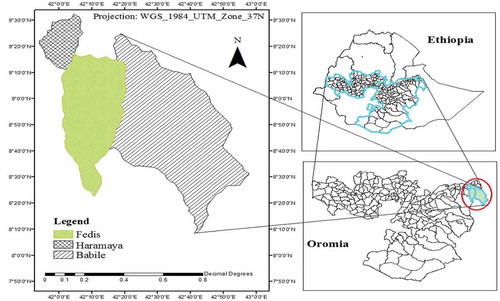

This study was conducted in Eastern Hararghe Zone between December 2016 and August 2018, Oromia Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. The Zone is bordered on the southwest by the Shebelle River which separates it from Bale, on the west by West Hararghe, on the north by Dire Dawa and on the north and east by the Somali Region. The Zone comprises of 18 districts, namely Babille, Bedeno,Chinaksen, Deder, Fedis, Girawa,Gola Oda, Goro Gutu, Gursum, Haramaya, Jarso, Kersa, Kombolcha, Kurfa Chele, Malka Balo, Meyumuluke, Midega Tola and Goro Muti. Haramaya, Babile and Fedis are the three districts of the Zone in which the present study was carried out. In each district, the potential Kebeles (villages) to use medicinal and aromatic plant to treat different human and livestock diseases were selected for detailed data collection (Figure ).

This Zone has a total population of 2,723,850 of whom 1,383,198 are men and 1,340,652 women; with an area of 17,935.40 square kilometers and has a population density of 151.87. A total of 580,735 households were counted in this Zone, which results in an average of 4.69 persons to a household, and 560,223 housing units. The two largest ethnic groups reported were the Oromo (96.43%) and the Amhara (2.26%); all other ethnic groups made up 1.31% of the population. Oromiffa was spoken as a first language by 94.6%, Somali was spoken by 2.92% and Amharic by 2.06%; the remaining 0.42% spoke all other primary languages reported. The majority of the inhabitants were Muslims (96.51%), while 3.12% of the population professed Christianity (CSA, Citation2007).

2.2. Sample size and sampling technique

Preliminary survey was conducted to gather information on the physical features and potentials of medicinal and aromatic plant utilization in the study areas. Out of 18 districts in the zone, three districts; namely, Haramaya, Fedis and Babile were selected based on potential of medicinal and aromatic plant utilization. From each district, four Kebeles were selected due to their plant resources for ethnobotanical data collection. Study participants (132 informants) were selected using the snowball sampling method (Redzic, Citation2006), and we particularly focused on local people who regularly use plants for medicinal purposes. In the processes the Woredas agriculture development offices of the districts have been helped in identifying potential areas (Kebeles) for practicing traditional medicine.

2.3. Ethnobotanical data collection

The data were collected using semi-structured interview questionnaires, focus group discussion and field observation. Semi-structured interviews were then employed to collect ethnomedicinal data with the help of local people and field assistants. Data on human and livestock diseases treated, local names of plants used, degree of management (wild/cultivated), status, parts used, methods of preparation, routes of administration, other uses of the medicinal and aromatic plant species, existing factors to these plants were gathered during the interviews. The interview questionnaires were prepared in English and then translated into local languages (Affan Oromo). Data collectors, based on their educational background and social status, were selected in each Kebele and detail orientation was given for them included the importance of the study, on how data are filled in the questionnaires and interview with the respondents. In focus group discussion key informants (these who have traditional knowledge on medicinal plants) were selected with the help of field assistances in each Kebeles.

During field observation, with the guidance of field assistances, status of medicinal and aromatic plants and their diversity were conducted. All the vernacular names were in the Afan Oromo and Amharic. In the field plant identification was carried out with the help of Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea (Edwards, Demissew, & Hedberg, Citation1997; Hedberg et al., Citation2009; Hedberg, Edwards, & Sileshi, Citation2003, Citation2006) and Useful Trees and Shrubs for Ethiopia (Bekele- Tessema, Citation2007). Some of specimens which were difficult to identify in the field were collected, pressed, dried and brought to Haramaya University for further identification comparing specimen in the herbarium.

2.4. Data analysis

A descriptive statistical method (e.g., percentage, frequency) was employed to summarize ethnobotanical data. The diversities of medicinal and aromatic plants were analyzed using PAST (PAleontological Statistical) software. Informant consensus factor (ICF) will be calculated for categories of human/livestock ailments to identify the agreements of the informants on the reported cures following the approaches used by Teklehaymanot and Giday (Citation2007). ICF will be calculated as follows: number of use citations for categories aliment (nur) minus the number of species used (nt) for that aliment, divided by the number of use citations for each aliment minus one.

Where:

nur = Number of usage-reported by informant.

nt = Number of plant species used.

The ICF values reveal that the strength of reliance of respondents on various plants and plant products for the treatment of different human/livestock diseases and/or ill-health conditions. The ICF values range from 0 to 1. A high value (close to 1) indicates that there is a well-defined selection principle for certain specific plants and plant products traditionally used to treat human/livestock diseases and/or ill-health conditions in the community and/or there is sharing of information amongst the ethno practitioners offering traditional medicine services in that particular community. A low value (close to 0) on the other hand indicate that plants and plant products used for the treatment of human/livestock diseases and/or ill-health conditions are chosen from a wide range of plants and plant products without relying on specific proven ones and/or the ethno practitioners offering traditional medicine services do not share information amongst themselves.

Priority ranking was conducted following Martin (Citation1995), for important medicinal and aromatic plants used to treat most common disease in the study area. Randomly selected informants were participated in this activity in order to identify best preferred medicinal plants for treatment of commonly known disease.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Respondents socio-demographic status

In the present study, a total of 132 respondents were interviewed from the three districts (44 from each) of which the majority were male respondents 108 (81.2%) and the rest 24(18.2%) were female respondents. However, females were engaged largely on production of aromatic plant species around their homestead and utilize these plants in their own house consumption or use as and income source from local markets. With regard to the age, highest age group ranges between 35 and 50 which accounts of 56.8% of the respondent followed by 50–65(27.2%) age categories

The educations of the respondents were poor due to the difficult to access school before 20 years ago in the study areas. Thus, majority of respondents with traditional knowledge on plants resources were not attained their education to tertiary level in the study areas. However, young people have better education than elders and females have lower education than males. Majority of respondents have family size ranging between 5 and 10 which account 53.8% of the total respondents (Table ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

3.2. Medicinal and aromatic plants of the study area

In this study, total of 87 species under 50 families were recorded from the three study districts distributed in wild, farmland, homegardens and roadsides. Of which 72 (82.8%) were identified for their medicinal value and the rest 15(17.2%) were utilized as both medicinal and aromatic (Table ). In addition many of these plant also used for fencing, fuel, shade, bee keeping and food as indicated by the informants in the study areas.

Table 2. Families recorded with more than one plant species and medicinal value in the study area

Table 3. Medicinal and aromatic plants identified in the three districts; scientific and local names, family names, their growth habit, diseases type treated, part used and preparation methods and route of administration

The most frequent plant families with the highest percentage of the total identified plant species in medicinal and medicinal and aromatic plant categories were shown in Tables and . Among the plants used for medicinal purpose the family Fabaceae accounts with 9(18.75%) species, followed by five families (Euphorbiaceae, Rosaceae, Apiaceae, Asteraceae and Solanaceae) each consisting of two species (Table ). In the medicinal and aromatic plant categories family Lamiaceae and Rutaceae accounts with 3(6.25%) species each followed by family Myrtaceae with 2(4.16%) species. Majority 30(60%) of the families were represented by single species each accounting 2.08% of the total families and the remaining 19(38%) of the families were represented by more than one plant species. Similarly, of the total families recorded 10(20.4%) were comprised of medicinal ad aromatic plant species (Table ).

Table 4. Families recorded with medicinal and aromatic plant species

3.3. Diversity of medicinal and aromatic plants

Peoples of the study areas were utilizing diversity of locally available medicinal and aromatic plants for different purposes. One of the uses of these plants was traditionally to treat different human and livestock diseases and provide flavors to food or act as repellent with their odors released from different parts of the plant (Table ). The diversity distribution of the identified medicinal and aromatic plants was indicated in Table below.

The result revealed that there is no a significant variation in terms of Shannon Wiener diversity index of medicinal plants in the study areas (Babile, Haramya and Fedis). However, aromatic plant species diversity is higher in Babile (H’ = 2.37) and Haramaya (H’ = 2.44) as compared to Fedis (H’ = 2.16). The lower index in the Fedis indicates that only few of aromatic plant species were more abundant. This is also true in the dominance index of aromatic plant in Fedis (D = 0.12) which were higher than the other two. The evenness index result showed that it is similar in all the study areas for both medicinal and aromatic plant species (Table ).

Table 5. Diversity of medicinal and aromatic plants identified in the study area

3.4. Common human and livestock diseases

In the present study, total of 22 human and 11 livestock health problems were identified for which peoples of study areas were using traditional medicine to treat it. The most common human diseases were abdominal pain, digestion disorder and vomiting, diarrhea, kidney diseases, evil spirit, pneumonia, cough/common cold, skin diseases and intestinal constipation. Similarly, frequently occurring livestock health problems were skin diseases, bloating, diarrhea, wound and inflammation and constipation.

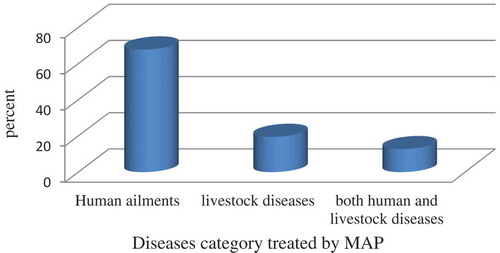

The result revealed that the majority of medicinal and aromatic plants 59(67.8%) were used to treat human health problem, whereas 17(19.5%) were used to treat livestock diseases and the remaining 11(12.7%) were used treat both for human and livestock health problems (Figure ). Among the human health problems, the highest proportions of medicinal and aromatic plants (19.7%) were used to treat abdominal pain followed by diarrhea (6.9%).

3.5. Informants consensus factor (ICF)

Informant consensus factor value of 17 different categories of human health problems and 11 livestock diseases were analyzed. Of the total of 22 human health problems identified in this study, the commonly mentioned 17 were used to find the ICF values (Table ). Human health problems that were found to be popular in the area were treated by different MAPs. Majority of human health problems (82.4%), have (ICF value > 0.80) and only three diseases, common cold, body swelling and digestion disorder and vomiting have ICF value less than 0. 80 (Table ). On the other hand, in the category livestock diseases ICF value is highest (ICF > 0.90) for all the diseases identified (Table ).

Table 6. Common human health problems that treated by MAPs and ICF values

Table 7. Common livestock diseases that treated by MAPs and ICF values

The result revealed that the utilization of specific MAPs to treat human/livestock health problem in study area is based on defined selection criteria and healing potential of the particular plant for the frequently occurring diseases.

3.6. Medicinal and aromatic plant parts used

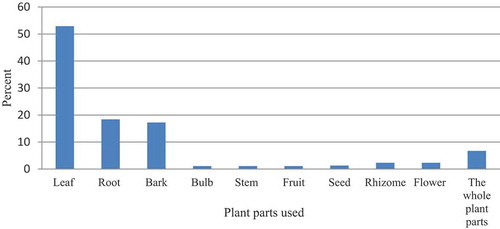

The result of analysis of medicinal and aromatic plants in the three districts showed that 9 plant parts were identified as major parts used to treat different human and livestock health problems. However, in most cases these parts were used in different combination and which is taken as a whole part of the plant. The most frequently utilized plant parts for remedy purpose in the study area is the leaf (52.9%), followed by the roots (18.4%) and bark (17.2%) (Figure ).

The finding of present study agree with the report of Meragiaw, Asfaw, and Argaw (Citation2016) in that leaves were the most frequently used parts (32.6%) used to treat various ailments, followed by roots (21.7%). Similarly, number of works carried out previously on medicinal plants elsewhere in Ethiopia revealed that leaves followed by roots were the common plant parts used to treat various human and livestock health problems (Bayafers, Citation2000; Dawit & Estifanos, Citation1991; Mirutse & Gobana, Citation2003). Such wide utilizing of leaves compared to other parts is important for survival of the plant providing the leaf and has a less negative impact on the survival and continuity of useful medicinal and aromatic plants and hence does not affect sustainable utilization of the plants in the area. However, predominant utilization of root, rhizomes and stem leads for destruction of the whole or the part of the plant and affect the survival of plants underutilization. But, in the present study the utilization of roots, barks, bulk and stem is minimal and not expected much effect on the survival of plants used for MAPs. Dawit and Ahadu (Citation1993) reported that herbal preparation that involves roots, rhizomes, bulbs, barks, stems or whole parts have effects on the survival of the mother plants.

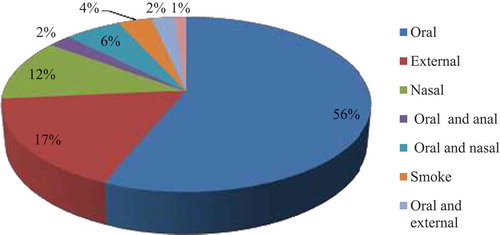

3.7. Route of administration and dosage

The results of analyses of route of administration revealed that majority of prepared traditional medicine were given oral (56%) followed by external application (17%) and nasal (12%). The rests were given by combination of two ways or smoking (3.4%) as well as chewing (1.2%) as indicated in Figure . The findings in the present study agree with the results of various ethnobotanical researchers elsewhere in Ethiopia (Debela, Citation2001; Ermias, Citation2005; Getachew, Dawit, & Kelbesa, Citation2001; Kebu, Ensermu, & Zemede, Citation2004; Meragiaw et al., Citation2016) that indicates oral as the predominant route of application. The key informants indicated that the remedies were prepared through the use of water as a solvent, and sometimes milk and honey for human diseases treatment. In few cases, again, the salt would be used as an ingredient for the effectiveness of the remedy.

Majority of the respondents and the key informants indicated that the measurements units used to determine the dosages are not standardized and more likely estimation which depend on the age and type of health problem, and description of the person who need it. Less dose would be order for children and younger, such as, half a glass or one coffee cup, for adults it would be more, one full glass. The dose also would be measured with the number of leaves, seeds or fruits. Similar finding was reported by Meragiaw et al. (Citation2016) in Delanta, Northern Ethiopia, that units of measurements to determine dosage are not standardized and were coffee cup, finger length and teaspoon. The quantity of plant part used is measured by number of leaves, seeds and fruits and length of root. Amare (Citation1976), Sofowora (Citation1982) and Abebe (Citation1986) have also reported lack of precision and standardization as one drawback for the recognition of the traditional health care system. The present study indicated that there is lack of precision in the determination of doses in the area and it was prepared mainly based on the estimation with the local material.

3.8. Diversity of medicinal and aromatic plants growth form

In this study four major medicinal and aromatic plant growth forms were identified in the study areas. These growth forms were trees (48.30%), herbs (29.90%), shrubs (19.50%) and climbers (2.3%) (Figure ).

The result showed that the parts of MAPs collected for utilization as medicinal purpose comes from tree plants in the study areas. This shows that traditional practitioner harvest leaves and other parts from tree plant without damaging the mother plant for sustainable and continual utilization. The finding of present study agrees with Maiti and Geetha (Citation2007) reported growth form classification of MAPs showed that trees (33%) were the most predominantly utilized growth forms followed by herbs (32%). However, the result is inconsistent with Belayneh, Asfaw, Demissew, and Bussa (Citation2012) report, Erer Valley of Babile Wereda in that majority of growth habit distribution of medicinal plant species fall under shrubs followed by trees.

3.9. Preference ranking

Preference ranking was analyzed for the frequently mentioned seven medicinal and aromatic plant species to treat commonly occurring human health problem, abdominal disorder in the study area. The result revealed that Senecio tropaeolofolius is the most preferred medicinal and aromatic plant to treat abdominal pain followed by Tamarindus indica and Moringa stenopetal in that order (Table ).

Table 8. Preference ranking of frequently used plant species to treat most commonly occurring human health problem, abdominal pain

3.10. Threats to medicinal and aromatic plants of the study area

There are different threats to medicinal and aromatic plants resources availability and indigenous knowledge utilizing these resources in the study area. It was reported by key informants that; less attention is given to medicinal plants by young generation and rather they focus on modern drug. Moreover, majority of respondents agreed that anthropogenic activities were responsible for reduction on the status of MAPs in the study areas. The most common factors identified were agricultural expansion, over harvesting, overgrazing, construction, drought, collection for firewood. All informants were agreed that due to the decrease in plant resources of medicinal value from the study area, they were forced to travel long distances even from one district to the other in search of the plant in use. Similar findings on the factors influencing the medicinal plants were reported from different parts of the country by different authors, Fentalle (Kebu et al., Citation2004), Konso (Tizazu, Citation2005), Gimbi (Etana, Citation2007) and Loma and Gena Bosa area (Mathewos, Sebsebe, & Zemede, Citation2013) confirmed that agricultural expansion, over harvesting, overgrazing, drought and collection for firewood were highly threatened to medicinal plants and indigenous knowledge on them.

4. Conclusion

The present study find out that peoples of eastern Hararghe zone have profound traditional knowledge on the utilization of medicinal and aromatic plants. These plants were collected from wild, farmland, homegardens and roadsides. Elders and traditional healers as a primary source of information participated in the survey and shared their eminent experiences on the utilization of MAPs. In this study, utilization of 87 plant species as medicinal and aromatic that have been used for the treatment of 22 types of major human and 11 types of animal ailments were documented. The finding of this study insights the baseline information on indigenous knowledge and further investigation on phytochemical analysis of MAPs of the study areas and scientific methods to evaluate the safety, efficacy and dosage prescription of the commonly reported medicinal and aromatic plants.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Office of Vice President for Research Affairs of Haramaya University, for providing necessary fund for this study. We would also like to thanks local peoples of the study areas and all field assistances, for their willingness to disclose traditional knowledge and cooperation during the data collection.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Melese Mengistu

Melese Mengistu is lecturer and researcher in Haramaya University. His area of research interest is ethnobotany, biodiversity and conservation of natural resource for better human welfare. Currently, he I conducting research related to ethnobotany.

Dargo Kebede

Dargo Kebede, is lecturer and researcher in Haramaya University. He has research interest on agroforestry, soil conservation and rehabilitation of degraded lands.

Dereje Atomsa

Dereje Atomsa, is lecturer and researcher in Haramaya University. His research interest is on biodiversity conservation, plant ecology and ethnobotany.

Arayaselasie Abebe

Arayaselassie Abebe, is lecturer and researcher in Haramaya University. His research interest area is plant ecology, biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management.

Dinkayehu Alemnie

Dinkayehu Alemnie, is lecturer and researcher in Haramaya University. He has research interest related to the application of biotechnology for better future.

References

- Abebe, D. (1986). Traditional Medicine in Ethiopia: The Attempts being made to promote it for effective and better utilization. SINET: Ethiopian Journal of Science, 9, 61–27.

- Amare, G. (1976). Some common medicinal and poisonous plants used in Ethiopian folk medicine (pp. 63). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Academic press.

- Bayafers, T., 2000. A floristic analysis and ethnobotanical study of the semi-wetland of Cheffa area, South Welo, Ethiopia (M.Sc. Thesis). Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Bekele, E. (2007). Study on actual situation of medicinal plants in Ethiopia. Japan Associaion for International Collaboration of Agriculture and Forestry (JAICAF). Retrieved from http://www.endashaw. com

- Bekele- Tessema, A., 2007. Useful Trees and shrubs of Ethiopia: Identification, propagation and management for 17 Agro climatic zones (Technical manual). World Agro-forestry, 550 pp. doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Belayneh, A., Asfaw, Z., Demissew, S., & Bussa, N. F. (2012). Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Wereda, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 2012(8), 42. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-8-42

- Blanco, E., & Breaux, J. (1997). Results of the study of commercialisation, exploitation and conservation of medicinal and aromatic plants in Spain.

- CSA. (2007). Ethiopian statistical authority. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Dawit, A., & Ahadu, A. (1993). Medicinal plants and enigmatic health practice of North Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Berhanina Selam Printing Enterprise.

- Dawit, A., & Estifanos, H. (1991). Plants as a primary source of drugs in the traditional health practices of Ethiopia. In J. M. M. Engels, J. G. Hawkes, & M. Worede (Eds.), Plant genetic resources of Ethiopia (pp. 101). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Debela, H., 2001. Use and management of traditional medicinal plants by indigenous people of Bosat Woreda, Wolenchiti area: An ethnobotanical approach (M.Sc. Thesis), Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Edwards, S. (2001). The ecology and conservation status of medicinal plants on Ethiopia. What do we know? In M. Zewdu & A. Demissie (Eds.), Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants in Ethiopia, proceedings of national workshop on biodiversity conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants in Ethiopia (pp. 46–55). Addis Ababa: Institute of Biodiversity Conservation and Research.

- Edwards, S., Demissew, S., & Hedberg, I. (eds.). (1997). Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea (Vol. 6). Ethiopia: Addis Ababa.

- Ermias, L., 2005. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and floristic composition of mana angatu moist montane forest, Bale, Ethiopia (M .Sc. Thesis). A ddis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

- Etana, T., 2007. Use and conservation of traditional medicinal plants by indigenous people in Gimbi Woreda, Western Wellega, Ethiopia (M.Sc. Thesis). Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, p. 111. doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Farnsworth, N. R., & Soejarto, D. D. (1991). Global importance of medicinal plants. In O. Akerele, V. Heywood, & H. Synge (Eds.), The conservation of medicinal plants (pp. 25–51). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Getachew, A., Dawit, A., & Kelbesa, U. (2001). A survey of medicinal traditional plants in Shirka district, Arsi Zone, ++++Ethiopia. THe Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Journal, 19, 30–47.

- He S. -A., & Sheng, N., 1997. Utilization and conservation of medicinal plants in China with special reference to Atractylodes lancea. p. 109–115. In eds. G. Bodeker. Rome: FAO.

- Hedberg, I., Edwards, S., Friis, I., Ensennu, K., Mesfin, T., Sebsehe, D., … Gehre, E. (2009). Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea Volume 8. General parts and index to Vols 1–7. Addis Ababa: The National Herbarium.

- Hedberg, I., Edwards, S., & Sileshi, N. (2003). Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea,” Part 1. Apiaceae to dipsacaceae. Addis Ababa: The National Herbarium.

- Hedbergs, I., Kelbessa, E., Edwards, S., & Demissew, S. (2006). Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea, Vol. 5. Gentianaceae to Cyclocheilaceae. Sweden: The National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University and Uppsala University, Department of Systematic Botany, Uppsala University.

- Institute of Biodiversity Conservation (IBC). 2009. Convention on biological diversity (CBD) Ethiopia’s 4th country report institute of biodiversity conservation.

- Iwu, M. M. (1993). Handbook of African medicinal plants. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Kassaye, K. D., Amberbir, A., Getachew, B., & Mussema, Y. (2006). A historical overview of traditional medicine practices and policy in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 20(2), 127–134.

- Kebu, B., Ensermu, K., & Zemede, A. (2004). Indigenous medicinal utilization, managemetn and threats in Fentale area, Eastern Shewa, Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Biological Sciences, 3, 1–7.

- Kelbessa, E., Demissew, S., Woldu, Z., & Edwards, S. (1992). Some threatened endemic plants of Ethiopia. In S. Edwards & Z. Asfaw (Eds.), The status of some plant resources in parts of tropical Africa Botany 2000 East and Central Africa NAPRECA monograph series no. 2 (pp. 35–55). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: NAPRECA, Addis Ababa University.

- Lange, D. (1998). Europe’s medicinal and aromatic plants: Their use, trade and conservation. Cambridge: TRAFFIC International.

- Lange, D. (2004). Medicinal and aromatic plants: Trade, production, and management of botanical resources. German: University of Landau, Institute of Biology.

- Maiti, S., & Geetha, K. A. (2007). Medicinal and aromatic plants in India. National Research Center for Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Boriavi, Anand -, 387, 310.

- Martin, G. J. (1995). Ethnobotany: A method manual (pp. 265–270). London: Chapman and Hall.

- Mathewos, A., Sebsebe, D., & Zemede, A. (2013). Ethno botany of medicinal plants in Loma and Gena Bosa Districts(Woredas) of Dawro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Topclass Journal of Herbal Medicine, Vol.2(9), 194–212.

- Meragiaw, M., Asfaw, Z., & Argaw, M. (2016). The status of ethnobotanical knowledge of medicinal plants and the impacts of resettlement in Delanta, Northwestern Wello, Northern Ethiopia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2016, 24. Article ID 5060247 doi:10.1155/2016/5060247

- Mirutse, G., & Gobana, A. (2003). An ethnobotanical survey on plants of veterinary importance in two woredas of Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiopian Journal of Science, 26, 123–136.

- Redzic, S. (2006). Wild edible plants and their traditional use in the human nutrition in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 45, 189–232. doi:10.1080/03670240600648963

- Shankar, D., & Majumdar, B. (1997). Beyond the biodiversity convention: The challenge facing the biocultural heritage of India’s medicinal plants. In G. Bodeker, K. K. S. Bhat, J. Burley, & P. Vantomme (Eds.), Medicinal plants for forest conservation and health care. Non-wood forest products 11 (pp. 87–99). Rome: FAO.

- Sofowora, A. (1982). Medicinal plants and traditional medicine in Africa (pp. 255–256). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Teklehaymanot, T., & Giday, M. (2007). Ethno botanical study of medicinal plants used by people in Zegie peninsula, north western Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 3, 12. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-3-12

- Tizazu, G., 2005. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Konso Special Woreda (SNNPR), Ethiopia (M.Sc. Thesis). Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa.

- Xiao, P.-G. (1991). The Chinese approach to medicinal plants – Their utilization and conservation. In O. Akerele, V. Heywood, & H. Synge (Eds.), The conservation of medicinal plants (pp. 305–313). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.