?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Sesame is an important cash crop and plays a vital role in the livelihood of many people in Ethiopia. However, a number of challenges hamper the development of the sesame sector along with the value chain. Therefore, this study aims at analyzing the value chain of sesame in Humera district, Tigray region, Ethiopia. The results showed that farmers and processors receive the highest profit share as well as marketing margin in the sesame value chain in the study area. The econometric model results showed that; farmland size, family members within the age group between 16 and 69, sesame yield, use of the improved seed, distance from market, and average selling price are significantly affecting factors of sesame supply. Thus, the government and concerned stakeholders need to give attention to yield increasing technologies in the study area to boost production and productivity, and thereby increase the market supply of sesame.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Sesame is a flowering plant in the genus Sesamum, also called benne. Sesame is widely naturalized in tropical regions and is cultivated for its edible seeds, which grow in pods. Ethiopia is known to be the center or origin and diversity for cultivated sesame. It is among the top producers and exporters of sesame seeds in the world.

However, the market supply potential of sesame is affected by various factors across the value chain. This study has identified major actors in the value chain and factors related to the market supply of sesame, which are of great importance for policymakers and other stakeholders in the subsector who are engaged in improving production and market supply of sesame in the region. By combining both value chain analysis and quantitative analysis of factors affecting sesame market supply, the study also adds to its scientific database to develop and advance the sesame sector in Ethiopia and the world.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Sesame (Sesamum indicum L, 2n = 26) grouped under the Sesamum genus of the Pedaliaceae family; is one of the oldest oil seed known for its quality plant oil and is cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Africa, and South America (Zhang et al., Citation2013). Sesame believed to be the native to the African savanna, however, its domestic production was recorded in the Middle East and India since 4000 years ago (Ayana, Citation2015). Globally, the top largest producers of sesame are Myanmar, India, China, Sudan, Uganda and Ethiopia (Girmay, Citation2018). Evidence also indicated that Ethiopia ranked 3rd in Africa in terms of sesame production (Hagose, Citation2017; Wijnands, Biersteker, & van Loo, Citation2009). In terms of export potential, Ethiopia is the third world exporter of sesame seeds after India and Sudan (Alemu & Meijerink, Citation2010; Temesgen, Gobena, & Megersa, Citation2017). Sesame is the second major export cash crop in Ethiopia, next to coffee (Abebe, Citation2016). According to Food and Agriculture Organizations (FAO) (Citation2015), sesame marketing has significantly increased in Ethiopia. Between 2002 and 2012, the earning from the sesame export increased from 66 to 427 million US dollars and its contributions to the national earnings has increased from 6.7% to 13.8% in the same period. From 2000 to 2016, the total amount of sesame export increased from 31 thousand tones to about 317 thousand tones, an increase of more than tenfold (Kedir, Citation2017).

Regardless of its increased export marketing and economic earnings, the Ethiopian Central Statistical Authority (CSA) and FAOSTAT figures indicate that the sesame area coverage, production, and productivity are not in a constant increment in recent years. For instance, the average sesame area coverage, production, and yield at the national level over the period of 2010 to 2018 were 332,953 ha, 2,486,469 quintals and 7.47 quintals per hectare, respectivelyFootnote1. Between 2010 and 2018, the area coverage decreased from 384,683 to 294,819 ha (23%), production decreased from 3,277,409 to 2,016,646 quintals (38%) and yield declined from 8.25 to 6.83 quintals per hectare (19.83%) (CSA, Citation2019; FAOSTAT, Citation2019). However, the sesame production has registered significant growth over the period from 2000 to 2009. In 2000, the total area cultivated for sesame was 38,190 ha, which produced 156,340 quintals with a yield of 4.09 quintals per hectare. In nearly a decade (2000 to 2009), the total area of sesame production has increased more than eightfold while production and yield increased more than sixteen-fold and double, respectively (Food and Agriculture Organization Statistical Division (FAOSTAT), Citation2019).

On the other hand, different studies claimed that Ethiopia has ample potential for sesame production (e.g. FAO, Citation2015; Gelalcha, Citation2009; Girmay, Citation2018; Kostka & Scharrer, Citation2011; Wijnands et al., Citation2009). This is mainly linked to sesame natural flexibility to adopt different soil types and harsh environments as well as Ethiopian diversified agroecology and potential of arable land, water, labor force, and market opportunities. However, this potential has not been adequately tapped yet due to different production-related problems. For example, studies by Gelalcha (Citation2009); Kostka and Scharrer (Citation2011); FAO, (Citation2015); Girmay (Citation2018); Hagose (Citation2017), and Kedir (Citation2017) indicated that shortage of improved varieties, poor seed supply systems, producers dependence on traditional seeds for many years, poor agronomic practices, pests and disease, drought, poor post-harvest management, weak farmers organization, poor market information system; and little research support to increase yields and erratic rainfalls are among major constraints hindering sesame production in Ethiopia.

Similarly, the sesame value chain in Ethiopia, which links producers to market, is hampered by a variety of constraints; primarily sever coordination challenges (Food and Agriculture Organizations (FAO) for United Nations, Citation2015; Galalcha, Citation2009). Recently, the Ethiopian government has made reform in sesame marketing and regulated Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX), which is a new market auction system in the country, as the only market outlet to sesame export. Hence, ECX collects sesame from different actors involved across the chain. Most of the sesame that is traded at ECX comes from the Humera, Metema, Wollo, Chanka, Wellega and Pawi, districts of the country. Particularly, Humera district is a well-known area in producing quality sesame in the country. About 30% of the country’s total sesame production comes from Humera districts of Ethiopia (CSA, Citation2015). As a result, of its new reforms, Ethiopian Commodity Exchange Authority (ECEA, Citation2013) noticed the shorter market chain for sesame in Humera district. Famers in Humera district sell their sesame to export market through cooperative unions and local collectors’ outlets, which in turn sell to the exporter (ECX) through their respective outlets. This is consistent with a notion that shorter market chains would reduce transaction costs for farmers. However, short-chain alone does not necessarily mean a strong relationship among value chain actors, particularly between farmers and traders. Most recent evidence from Humera district claims that the farmers in that district have no way or access for post-harvest handling rather than selling their sesame at low market price due to limited access to credit, insufficient storage facilities and transportation problems (Hagose, Citation2017). Moreover, sesame yields are continuously decreasing since it is common practice amongst farmers to reuse harvested sesame for replanting in the district. Thus, there is a need for the comprehensive study about sesame value chain in Humera district of Ethiopia.

Using data collected from sesame value chain actors (i.e. input suppliers, farmers, traders, and other actors), this study analyses the sesame value chain in Humera district of Tigray region, Ethiopia. More specifically, the study identifies the actors and their functions across the sesame value chain. It examines the division of the market margins throughout the chain. Moreover, it attempts to analyze the determinants of sesame market supply at farm level in the district.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area and data collection

The study was conducted in Humera district, which is, located in the northwestern part of Tigray regional state, in Ethiopia. The Humera district was purposively selected for this study because of its highest sesame production potential in the country. The study employed two-stage sampling techniques to collect data from actors involved in the sesame chain. In the first stage, from a total of 21 peasant associations (PA) in the Humera district, 4 were purposely selected based on their production level, accessibility, and experience in sesame production. In the second stage, sesame farm households, cooperatives, traders and processors were randomly selected using probability proportional to the size. Accordingly, a total of 129 (100 producers, 5 cooperatives, 20 traders and 4 processors) were interviewed to collect the required data. Alongside the survey, from each peasant association, focus group discussion (5 to 8 participants in each group), key informant interview, and researchers’ direct observation were used to collect detailed data across the sesame chain.

Moreover, the secondary data were collected from Humera district government offices, Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (BoARD), Dedebit Credit and Saving Institution (DECSI), Humera Agricultural Research Center (HuARC), Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) authority, primary cooperatives in the sampled peasant associations and their unions, and other non-governmental organizations such as Sesame Business Network (SBN) which is involved in sesame research and development activities in the study area.

2.2. Methods of analysis

The collected data were subjected to descriptive and econometric methods of data analysis. The descriptive methods such as chain map and economic parameters were used. Analysis specifying functions of each actor across sesame chain described under the map. Economic parameters were used to analyze profit and gross margins across the chain. Econometrics method such as multiple linear regressions was used to analyze the determinants of sesame quantity supplied to the market.

2.2.1. Marketing margin

Marketing margin of the given agricultural commodity is referred as the difference between purchase and sale prices of that commodity through its marketing channel. Gross margin is calculated by dividing the gross income or gross profit to the revenue earned from sales. Then, multiply by 100 to give a percentage. For this study, the gross marketing margin (GMM) of sesame is given as:

The net marketing margin (NMM), which is the percentage of the final price earned by the intermediaries as their net income after their marketing costs are deducted, and is calculated as:

The equation tells us that a higher marketing margin diminishes the producer’s share and vice versa. It also provides an indication of welfare distribution among production and marketing agents.

2.2.2. Sesame marketable supply function

Multiple linear regression model (OLS) was fitted to analyze factors affecting amount of sesame supply to the market. All sampled farmers producing sesame participated in the marketing. The dependent variable is the amount of sesame supplied to the market which is a continuous variable. Hence, OLS model is right fit to the farm household data analysis. Following Gujarati (Citation2004), the multiple linear regression model is specified as:

where, Yi refers the volume of sesame supplied to the market, Xi’s are the vector of explanatory variables, is the intercept,

are parameters of the

explanatory variables, and

is error term. Before fitting the model to the data, the possible multicollinearity among the explanatory variables was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). As a rule of thumb, if the VIF is greater than 10, the variable is said to be highly collinear (Gujarati, Citation2004). Consequently, the VIF for all explanatory variables are less than 10 (1.06–1.35), which indicates that there is no serious multicollinearity problem among explanatory variables included in the model estimation.

2.2.3. Hypothesis and description of the variables

In the case of identifying factors affecting sesame supply to the market at farm household level in the Humera district, the main task was exploring which factors potentially influence and how these factors are related to the dependent variable. Therefore, the following dependent and independent variables hypothesized in Table .

Table 1. Description of the variables included in the model estimation and its hypothesis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sesame value chain map of the Humera district

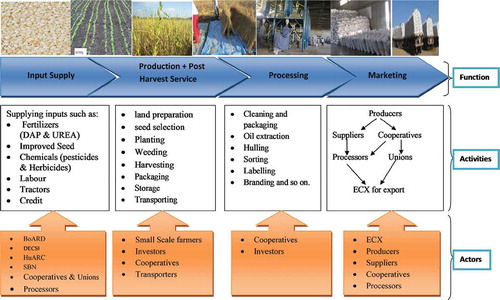

Value chain map is a potential starting point for the inclusion of producers, traders, consumers, and other stakeholders in the chain (Lundy et al., Citation2014). Hence, we start presenting our results by mapping of the sesame value chain in the study area (Figure ). The chain map described in Figure can also be applied for the nation as a whole because sesame production, processing, and marketing situations are almost similar in all regions. The map involves functions, actors and other service providers in the whole value chain.

3.1.1. Main actors in sesame value chain

The main actors in the sesame value chain are an individual or institution directly involved in sesame value chain activities from the points of production to consumption. The main actors of the sesame value chain in Humera district are:

3.1.1.1. Input suppliers

As it is shown in Figure , the main input suppliers in the sesame value chain in Humera district are Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (BoARD), Dedebit Credit and Saving Institution (DECSI), Humera Agricultural Research Center (HuARC), Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) market, Sesame Business Network (SBN), cooperatives, and processors. The major inputs supplied to the farmers in the district include improved seed, chemicals such as pesticides, fertilizers, and finance/credit.

Although Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (BoARD), Humera Agricultural Research Center (HuARC), and Sesame Business Network (SBN) are serving as sources for improved sesame seeds, the majority of farmers use recycled seed that they have saved from their previous production. This is consistent with findings of Kostka and Scharrer (Citation2011) in other areas: “it is common practice among the sesame farmers to use local or recycled varieties in Assosa and Metekel districts of western Ethiopia”. The main reason is that farmers believe that local sesame varieties are better adaptable to their local conditions. As a result, their sesame yields are continuously decreasing in recent years. However, research centers in Humera district have shown that replanting the same sesame can only achieve good yields for two consecutive years. After that, farmers should plant a new variety, or they have to rotate with other crops in order to prevent a decline in yields. On the other hand, farmers rarely use fertilizer for sesame production. All sources of chemical fertilizers supplied to farmers were from the government through cooperative.

Other important inputs for sesame farmers are pesticides, which are often supplied by primary cooperatives and their unions in the district. However, interviews with representatives of several cooperatives revealed that they were often unsatisfied with this service. The pesticides are too expensive in comparison with market prices offered by traders or private dealers, and often arrive too late. Private input dealers exist in Humera town and sell to farmers individually. In addition, plenty of local traders sell pesticides to farmers, sometimes on credit.

Credit, which is one of the essential inputs for sesame producers, is provided by Dedebit credit and saving microfinance institution. Yet, according to interviewed farmers and other stakeholders, loans are too small, ranging from 5,000 to 15,000 Ethiopian birr in total (US$ 259 to777), depending on the collateral and repayment history of farmers. To pay for all the required inputs, as well as land preparation and harvesting, with labor being expensive, loan-size needs to be tripled in order to be effective. Another alternative source of loan is farmers’ cooperatives, which are located at each PA. These cooperatives provide a loan and storage service for members only. Commercial banks also offer loans but only against collateral which farmers usually do not have since cattle and land do not qualify for collateral in Ethiopia. For this reason, Commercial Bank of Ethiopia does not provide loans to individual farmers, but to cooperative unions.

3.1.1.2. Producers

Sesame producers, in the study area, are predominantly small-scale farmers. Majority of farmers apply traditional way of farming including mono-cropping. They use broadcasting for planting and manual weeding, harvesting, drying, and threshing. Some sesame farmers practice a little mechanization that would reduce extensive use of labor force. These farms apply improved seed, fertilizer, and pesticides on their farm. They produce sesame for only commercial purpose. They supply their produce to cooperatives or local traders. In some cases, they sell directly to big traders and exporters at ECX market if they have bulk quantities (usually more than 50 quintals) of sesame produce.

3.1.1.3. Traders

Traders in the district are not allowed to buy or sell sesame other than primary markets established at each PA by ECX. Primary cooperatives through unions are also involved in the collection of sesame. Cooperatives are becoming important stakeholders in sesame sectors by virtue of the various privileges provided to them by the government. There is at least one farmer cooperative at each PA. A number of traders in the sample PAs have great variation based on their potential to supply more quantity of sesame to the market.

3.1.1.4. Processors and exporters

Most processors and exporters are found in Humera town and Addis Ababa city. Exporters screen, clean and bag sesame into 50 kg of bags. According to the bureau of investment of Humera, there are 21 cleaning enterprises in the town, but not hulling. Specifically, the hulling enterprises are located in or around Addis Ababa having branch offices in sesame production regions. Sesame processors are facing problems of impurities such as dirt, branches, and stones. This poor quality of sesame supply with high impurity level needs more cleaning costs to get it ready for export. This lowers the competitiveness of sesame export. Because of the low quality of sesame, importers in many developed countries purchase sesame seeds and resale it at a very high price through adding value in cleaning and hulling. Reducing this wide gap in the selling price of sesame requires quality improvement at all levels.

3.2. Sesame market channel

A marketing channel is the people, organizations, and activities necessary to transfer the ownership of goods from the point of production to the point of consumption. It is the way products get to the end-user, the consumer; and is also known as a distribution channel. There are four main marketing channels for sesame sell in the Humera district. These are:

Channel I Producers →Traders→ Processors/Exporter →Export market

Channel II Producers→ Cooperatives→Processors or Exporters→ Export market

Channel III Producers →Cooperatives →Unions→ Export market

Channel IV Producers→Cooperatives →Unions→Processors/Exporters→ Export market

According to the field survey, urban traders had the highest potential for acquiring sesame directly from farmers in the district. The sampled farmers sold 58% of their produce to traders in primary markets established by the government within their PAs. If producers have more than 50 quintals of sales volume, they will directly sell at ECX central market. Almost all traders traded their sesame to processors and exporters, who directly sell to the international market through EXC market outlet.

3.2.1. Marketing costs and margins

The results from calculations of profit and marketing margins of actors in the sesame value chain in the Humera district showed that producers and processors received the highest profit margin (Table ). This indicates that producers and processors involved in the sesame value chain can make a reasonable profit on their sales as long as they are able to reduce overhead costs such as labour cost. Moreover, the gross marking margin of farmers is highest in the chain followed by processors.

Table 2. Costs, marketing profit and margins of actors in sesame value chain

3.3. Factors affecting sesame supply to the market

The results of multiple linear regressions (Table ) indicate that six of the 13 hypothesized explanatory variables were found to have significantly influenced market supply of sesame in the district. The significant variables were land cultivated to sesame production, yield per hectare, distance to market, average prices of sesame selling, number of family members aged between 16 and 69, and use of improved sesame seed. The signs of the parameter estimated of the significant variables were as expected except selling price and distance to market.

Table 3. OLS results of factors affecting farm-level marketable supply of sesame in Humera district

The overall goodness of fit represented by model count R2 is very good and the adjusted R2 value is 0.806. This result indicates that about 80.60% of the variation in farm-level market supply of sesame was attributed to the hypothesized variables.

The total size of land cultivated to sesame is significantly and positively related to the amount of sesame supplied to the market by the farm households. The positive relationship implies that an increase in land area cultivated to sesame production increases marketable supply of sesame. Increasing in the size of 1 ha of land cultivated results in an increase in marketable supply of sesame by 3.508 quintals, keeping other factors constant. This result is consistent with findings of Goshme, Tegegne, and Zemedu (Citation2018) in Malokoza districts of the southern Ethiopia, who stated that an increase in the size of 1 ha of land allocated under sesame resulted in an increase in farm-level market supply of sesame by 6.80 quintals.

Productivity (yield) of sesame affected market supply significantly and positively as expected at 1% significance level. Since this variable is a proxy variable for amount of sesame produced by households, it indicates that households with high level of yield had also supplied more to the market than those who had a less yield of sesame. The value of the coefficient for the yield of sesame implies that an increase in yield of sesame by one quintal per hectare resulted in an increase in the farm-level marketable supply of sesame by 3.499 quintals, keeping other factors constant. Similar results were also reported by Goshme et al. (Citation2018) and Aysheshm (Citation2007) who studied in southern and western Ethiopia, respectively. Both studies reported that households with high level of yield supplied more to the market than those who had low yield of sesame in their respective study area.

Use of improved seed has positively affected the marketable sesame supply as it was expected. Use of improved seed increases the amount of sesame supplied to the market by 3.329 keeping other factors constant. This result is similar to the findings by Aysheshm (Citation2007) in Metema district of Ethiopia.

Distance from the central market place was assumed to influence marketable supply of sesame negatively, though our current result is in reverse. The assumption here was that the closer a household to the market, the more the household is motivated to produce sesame and supply it to the market. The result indicated that for the household who lives far from the central market by 1 km, quantity sold of sesame increases by 1.939 quintals keeping other things constant. The reason for having a positive relationship with distance from the market place and amount of sesame supplied could be due to richer fertility of land as we go far from the center because those areas were started to be used for farming recently whereas the land around the central market has been used for many years. A research finding conducted by Aysheshm (Citation2007) reported a positive relationship between the two variables, which is similar to our results. However, Tadesse (Citation2011) and Goshme et al. (Citation2018) reported that there is a negative relationship between distance to the market and amount supplied to the market.

The market price of sesame, in 2015, was negatively and significantly related to its supply to market. In economic concept, quantity supplied increases as selling price increases which is not supported by this result. However, our result might be related to the season of the sesame selling. The previous study by Gelalcha (Citation2009) and Hagose (Citation2017) indicated that sesame farmers in Humera district sell immediately after harvest when the price is the lowest. The single most important reason for selling immediately after harvest was farmers’ liquidity constraints related to their credit balance, family need, government tax, and other obligations.

Availability of family members between ages of 16 to 69 years positively affected the amount of sesame supply to the market in the study area. The result implies that as productive age family members increase by one person, sesame supplied to market increases by 1.146 quintals keeping other factors constant. This is because the productive age persons strive to produce and sell more sesame either by renting land or doing effectively on own land. In the study area context, this result is mainly relevant to the larger family members who may provide labor for sesame planting, weeding, and harvesting so as to maximize production and productivity.

4. Conclusions

The results of the current study show that there are various actors across the sesame value chain in Humera district. The major once are input suppliers, producers, traders, processors, and exporters. Producers are gaining a lower yield, compared to the production potentials of the study area. There is a need for increased production and productivity of sesame in the study area. This could be enhanced through extensive use of modern agricultural practices and technologies such as improved quality seed, combine harvester, and improved post-harvest management practices. These practices can enhance quality as well as the increased supply of the sesame product to the export market. Regarding profit share and marketing margins, the producers and processors tend to gain the highest amount of profit share and marketing margin across the sesame chain. This indicates that the sesame market is not well developed, and with small improvements in agricultural practices and use of modern technologies both the producers and processors can add value and make more profit than they receive now. Moreover, the estimates of linear regression model showed that area of land allocated to the sesame production, yield per hectare, distance to market, average market price, use of the improved seed, and the number of family members under productive age group significantly affects the amount of sesame supply to the market. The government and other relevant stakeholders who aim to improve the functioning of sesame market to the export level need to address these factors. They should give more emphasis to the availability and use of improved seeds and other yield enhancing technologies, improved post-harvest practices and handling, options access to credit, possibilities to consolidate land for technology use and economics of scale, and further support value addition through processing.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Aksum University for funding fieldwork of this study through its internally funded project entitled “Promoting Village-based Sesame Seed Enterprise in Humera: A choice for sustainable seed system”.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mengstu Berhe Gebremedhn

Mengstu Berhe Gebremedhn (Mr) is a researcher in Ethiopian Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA). He has MSc in agribusiness and value chain management from Aksum University, Ethiopia.

Worku Tessema

Worku Tessema (Ph.D.) is senior policy officer food security & sustainable development in the Embassy of the Netherlands, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Girma Gezimu Gebre

Girma Gezimu Gebre (Mr) is an academic staff member of the department of agricultural economics at Aksum University. He is a doctoral fellow at the department of agricultural and resource economics at Kyushu University, Japan. His research focus is on the agricultural value chain, gender, technology adoption, agricultural production, agricultural policy, innovation, and food security.

Kahsay Tadesse Mawcha

Kahsay Tadesse Mawcha (Mr) is Assistant professor in plant pathology at the department of plant science in Aksum University.

Mewael Kiros Assefa

Mewael Kiros Assefa (Mr) is an academic staff member of Aksum University and Ph.D. fellow (Plant Sciences) at Lincoln University, New Zealand

Notes

1. Quintal is a unit of weight equal to 100 kg.

References

- Abebe, N. T. (2016). Review of sesame value chain in Ethiopia. International Journal of African and Asian Studies, 19,36–47.

- Alemu, D., & Meijerink, W. G. (2010). Sesame traders and the ECX: An overview with focus on transaction costs and risks, VC4PPD report #8, Addis Ababa. https://www.wur.nl/upload_mm/4/1/8/73de144c-a7e6-45cd-8374-746b25526cc7_Report_8_Alemu__Meijerink_0707102.pdf

- Ayana, G. N. (2015). Status of production and marketing of Ethiopian sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum L.): A review. Agricultural and Biological Sciences Journal, 1(5), 217–11.

- Aysheshm, K. (2007). Sesame market chain analysis: The case of Metema Woreda, North Gondar Zone, Amhara National Regional State. MSc thesis in Agriculture (Agricultural Marketing). 123p. Haramaya (Ethiopia): Haramaya University. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/3165 doi:10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0467B

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia. (2019). Agricultural sample survey 2018/19 (2011 E.C.) report on area and production of major crops for private peasant holdings, Meher season, volume I. Addis Ababa. http://www.csa.gov.et/survey-report/category/373-eth-agss-2018

- Central Statistics Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia. (2015). Agricultural sample survey (2009/10-2013/14) report on area and production of major crops for private peasant holdings, Meher season. Addis Ababa. http://www.csa.gov.et/survey-report/category/131-eth-agss-2015

- Ethiopian Commodity Exchange Authority ECEA. (2013). Crop market assessment study of wheat, maize, sesame and haricot bean, Ethiopia Commodity Exchange Authority (ECEA), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Food and Agriculture Organization Statistical Division (FAOSTAT). (2019). Available online at http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/?#data/QC

- Food and Agriculture Organizations (FAO) for United Nations. (2015). Analysis of price incentives for sesame seed in Ethiopia, 2005-2012. Technical notes series, MAFAP, by Kuma Worako,T., MasAparisi, A., Lanos, B., Rome. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4528e.pdf

- Gelalcha, D. S. (2009). Sesame trade arrangements, costs and risks in Ethiopia: A baseline survey. https://www.wur.nl/upload_mm/9/a/9/59d09a46-b629-4014-b2bd-adf765894adc_Report2Gelalcha170610.pdf

- Girmay, B. A. (2018). Sesame production, challenges and opportunities in Ethiopia. Agricultural Research & Technology: Open Access Journal, 15(5), 555972. doi:10.19080/ARTOAJ.2018.15.555972

- Goshme, D., Tegegne, B., & Zemedu, L. (2018). Determinants of sesame market supply in Melokoza District, Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences (IJRSAS), 4(10), 1–6. doi:10.20431/2454-6224.0410001

- Gujarati, N. D. (2004). Basic Econometrics (4th ed.). USA: McGraw-HiII/Irwin.

- Hagose, L. W. (2017). Strategic analysis of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) market chain in Ethiopia a case of Humera district. International Journal of Plant and Soil Science, 15(4), 1–10, 31928. doi:10.9734/IJPSS/2017/31928

- Kedir, M. (2017). Value chain analysis of sesame in Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, 5(5), 620–631.

- Kostka, G., & Scharrer, J. (2011). Ethiopia’s sesame sector. The contribution of different farming models to poverty alleviation, climate resilience and women’s empowerment. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/ethiopias-sesame-sector-the-contribution-of-different-farming-models-to-poverty-137664

- Lundy, M., Amrein, A., Hurtado, J., Becx, G., Zamierowski, N., Rodríguez, F., & Mosquera, E. (2014). LINK methodology: A participatory guide to business models that link smallholders to markets, 2nd ed. Cali, CO: Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT. (CIAT Publication No. 398) ISBN 978-958-694-114-3 (PDF) http://ciat-library.ciat.cgiar.org/articulos_ciat/LINK_Methodology.pdf

- Tadesse, A. (2011). Market chain analysis of fruits for Gomma Woreda, Jimma Zone, Oromia National Regional State. MSc thesis in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics). Haramaya, Ethiopia: Haramaya University. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/12603

- Temesgen, F., Gobena, E., & Megersa, H. (2017). Analysis of sesame marketing chain in case of Gimbi districts, Ethiopia. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(10), 86–102.

- Wijnands, J. H. M., Biersteker, J., & van Loo, E. N. (2009). Oilseeds business opportunities in Ethiopia 2009. http://edepot.wur.nl/22112

- Zhang, H., Miao, H., Wang, L., Qu, L., Liu, H., Wang, Q., & Yue, M. (2013). Genome sequencing of the important oilseed crop sesamum indicum L. Genome Biology, 14, 401. doi:10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-401