?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The purpose of this article is to analyze the economic impact of participation of parboiled rice stakeholders in contract farming. Data were collected from a random sample of 200 farming households including 150 participants and 50 non-participants in the department of Collines in Benin. The results of econometric estimates show that the participation in contract is mainly determined by membership in a group of rice farmers, technical extension assistance and access to markets, good quality agricultural products, gender and formal education. Findings also reveal that contractualization has a positive effect on the income of the main primary players, in particular producers and processors of parboiled rice. It is therefore urgent that the agricultural contract remains a very important lever in rural areas in Benin. The contracts are likely to improve the economic efficiency of the adopters. Appropriate flexible contract measures are necessary and essential to boost growth in developing countries.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The agricultural sector including the rice sector is key in strengthening the Beninese economy owing to its contribution in economic growth and the role of its stakeholders. In that context, this paper aims at analyzing the economic impact of participation in contract farming on the agricultural income of parboiled rice producers and transformers in Benin. Data were collected from random sample farming households in the Collines department and analyzed using a two-stage model. There was evidence to show that the adoption of contractualization is driving by many factors including mainly the membership of rice farmer group, technical extension assistance, access to markets and good quality of agricultural products, gender as well as formal education. In addition, contractualization has positive effects on agricultural income in the parboiled rice value chain in Benin. It is urgent to define an appropriate institutional framework to support this mode of governance of parboiled rice in Benin.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

The agricultural sector is key for strengthening the Beninese economy because it contributes at 32.7% on average to the GDP, 75% to the export earnings, 15% to the receipts of the state and provides about 70% jobs. It is therefore considered to be one whose much potential must be judiciously exploited to support national economic growth and thus contribute to the effective fight against poverty (MAEP, Citation2013). According to the Strategic Development Plan for the Agricultural Sector PSDSA (Citation2016), the agricultural sector is characterized by the predominance of family-type farms and by high vulnerability to climatic variability. Incomes and productivity are low and the labour force is only partially valued, which makes agricultural products very uncompetitive. Most farmers have very little use of improved inputs and engage in mining practices that further degrade natural resources.

Despite the climatic and seraphic conditions favourable to the diversification of agricultural production, Benin continues to massively import certain products, notably (i) rice from Asia, (ii) counter-season vegetable products from neighboring countries such as Nigeria, Burkina Faso and Togo, (iii) frozen products (poultry and fishery products), table eggs and milk to cover the food needs of the population. In the state agricultural policy, which focuses on green growth, the Agricultural Sector Strategic Recovery Plan has been implemented. The objective of this plan is to promote the most promising agricultural sectors in Benin. Rice production occupies a decisive place. In these two successive documents, the rice sector, by virtue of its economic as well as social importance (household self-consumption and food security), occupied a prominent place. Efforts to promote the sector have been made, through the implementation of several projects/programs which contribute to increase the productivity and incomes of rice producers.

Despite these important efforts, it is clear that the living conditions of producers are struggling to improve due to the problems they regularly face. The difficult access to factors of production, the difficulties linked to the sale of products, the difficult access to agricultural credits, the poor quality of the final products available on the markets, the non-competitiveness of the actors, lack of organization, constitute the most common and recurrent problems. Farmers face considerable transaction costs (high market entry costs) driving small producers into the vicious cycle of subsistence farming (Kpenavoun Chogou & Gandonou, Citation2009). Under these conditions, farming contract, by offering producers a guaranteed market, credit and technical assistance, could allow them to open up to the markets (Olounlade et al., Citation2011).

The rice sector, due to the multiplicity of products and by-products which derive from it, is experiencing the enthusiasm of several farmers. Several value chains are developed (white rice, parboiled rice, paddy rice, etc.). In the Atacora department, the parboiled rice value chain has experienced particularly strong growth. In this area of Benin, women as well as men, individually and/or collectively (groups), adhere to the activity of parboiling rice.

In view of the economic and social importance of this activity, the projects/programs have undertaken initiatives to professionalize the parboiling of rice. The objective of this contractualization is to improve the quality of products, guarantee the production market, facilitate the supply of production inputs, improve actors’ incomes, etc. Introduced for more than five years in the departments of Atacora and Donga by GIZ. This intermediate model of contract farming seems particularly suited to the current context of the rice sector and has definitive implications not only for the governance of the value chain but also for the economic performance of the rice sectors and the improvement of the incomes of adopting actors.

This article analyses the driving factors of contract adoption in the value chain of “parboiled rice” and the effects of this contractualization on their income by link. In the context of Benin as well as that of other developing countries where low agricultural productivity and the instability of agricultural prices are major challenges to be addressed, the study provides important data and insights into rice development policies and the promotion of rice value chains in central Benin. In the literature, there are several works on the rice sector in Benin but few studies have addressed the question of contracts between the actors (Adégbola et al., Citation2014a). Most of these works are oriented towards the analysis of the impact of contractualization on producer performance only (Adégbola et al., Citation2014b; Fiamohe & de FRAHAN, Citation2012; Dossouhoui, Citation2019. The contribution of the paper to literature is twofold; the study: i) provides users with a new survey database on the state of contractual relations between producers and steaming women of rice in central Benin and ii) provides insights into the ways to improve transactions between different actors in the value chain. From a methodological point of view, the study proposes a simple method of analysis of the impact of participation in the contract on the incomes of rice producers and processors. Using the heckprobit econometric model, this study contributes in general to the promotion of the adoption of contracts within value chains as determinants of transactions. These elements then justify the interest of the analysis of factors favouring the adoption of contracts as a mode of governance of agricultural value chains in order to propose orientations for the implementation of agricultural development policies. This study shows that participation in contracts optimizes the income of the two types of actors (producers and processor) and that this positive and significant effect of the adoption of contracts on income is reinforced by the supervision of an extension agent and membership of a group.

The article is structured in five main parts, namely: the justification of the context, the theoretical and empirical literature, the methodology, the results and finally the conclusion.

2. Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

In the process of globalization, local supply chains are increasingly inserted into the supply chains of large companies which are constantly reconfiguring their scope of activities. These large companies, by erecting and applying their own standards, widen their area of influence beyond their countries of origin and thus appear as indisputable key agents governing the value chains that are spreading worldwide (Tozanli & El Hadad, Citation2007). This literature review mobilizes the theoretical framework of the global value chain and theoretical and empirical considerations on the adoption of contractualization as a mode of governance within agricultural value chains.

2.1. The global value chain and governance of the agricultural value chains

In the literature, governance is a key concept in any study on the analysis of value chains. Gereffi and Korzeniewicz (Citation1994) present an approach in the early 1990s as a “commodity chain” analysis which will be then developed as a global value chain (GTC) (Gereffi et al., Citation2005). With this approach, it offers a multidisciplinary tool for analysing the phenomena of globalization and studying the organization of world markets which generates power relations between the various players in the chain and renews the sector approach. Defined as “an inter-organizational network built around a product, which connects households, businesses and States within the global economy”, the CGV revolves around four main dimensions (Palpacuer, Citation2000)—a technical-economic dimension which corresponds to the sequence of activity implemented from conception to marketing of the product (intra- and inter-industry)—a territorial dimension which is characterized by a variable degree of dispersion or concentration of activities according to the observed value chains—a socio-institutional framework which corresponds to the rules, standards and public policies which regulate and influence the activity of firms at the global, macro-regional or local level and thus contribute to structuring the CGV.—a system of governance which is decisive on the organization of the structure of product flows, the territorial extent of the chain and sometimes on the socio-institutional framework.

It is at the level of the “governance system” linked to the notions of barriers to entry that one distinguishes, on the one hand the chains dominated by producers where the actors located upstream of the chain who have technological skills or natural advantages, coordinate and structure the global chain and, on the other hand, the downstream chains where large modern distribution firms control the design, marketing and international development of products and which, by consequently, all of the actors operating in the GSC manage (Arja et al., Citation2004). “Governance” receives particular attention because it seems closely linked to a concept of upgrading which is none other than the learning process allowing the creation or improvement of specific skills by the actors who are in a position of dependence on the key agent (Palpacuer, Citation2000). To position yourself on remunerative links in the chain, it is important to acquire, create and develop specific skills. In order to better understand the management of power and control within the GTC, Gereffi et al. (Citation2005) offer five modes of governance, each bringing a compromise between the benefits and the risks of supplying on the market. In addition to two classic forms of coordination, which are market governance and vertical integration, there are three new modes, based on the balance of power established between the key agent and the other actors.

In the modular chain, the buyer imposes his specific standards concerning the characteristics of the products and the suppliers have full responsibility for the use of the production technology and bear the expenses made to meet the specifications of the customers. Asymmetry in the balance of power remains at a relatively low level and both suppliers and customers work with several partners. The relational chain offers a system where the relationships between suppliers and buyers are complex and are most often characterized by mutual dependence given the high specificity of the partners’ assets. Physical proximity can also be a strong link defining the relationship between suppliers and buyers. Finally, in the captive chain, power is directly exercised by the key player over suppliers with a high degree of explicit coordination and a significant asymmetry between the powers held by the leading firm and its suppliers. Control and coordination of the chain are entirely managed by the leading firm. The integration of new suppliers makes coordination of the supply chains more complex, especially when there are significant differences between the requirements of the key players governing the GTC and local skills and requires considerable efforts to upgrade suppliers from developing countries. This process creates various levels of acquisition of new skills and involves hybrid forms of governance (Tozanli & El Hadad, Citation2007).

2.2. History and importance of contract farming

While sharecropping contracts between lessees and landowners have existed in agricultural economies for millennia (as in ancient Greece or China see Eaton and Shepherd (Citation2001)), contracts between firms and farmers occupying their own land do not seem to go back only a hundred years.

Little (Citation1994), for example, explains that the Japanese used these devices in Taiwan in the last decades of the nineteenth century, as did American companies in Central America in the first decades of the XXV. Vavra (Citation2009) shows that contractualization is important because it can constitute for the sector another governance mechanism often sensitive to the efficiency of supply chains.

There are that these improvements can be explained in particular by market players, thanks to better coordination in the various stages of the supply chain, as well as better information for specific players and also to better management of quality and flow of agricultural products.

Likewise, Masten and Saussier (Citation2000) show that these contracts represent a challenge for the public authorities, since not only do contracts guarantee a level playing field and the rules of the game, but also contracts maintain reliable flows of information on prices. They explain that contract farming is decisive for policymakers, it is essential to understand the functions and implications of contracts in order to be able to distinguish effective practices from anti-competitive practices and to put in place authorized policies in this regard.

The many questions related to the diversity of contractual practices can be grouped into three main categories: (1) what promotes the development of these practices? (2) what are the incentive measures implemented to ensure coordination and control? and (3) what is the impact of contracting on the agricultural sector? These questions are rooted in two very different and more or less competing approaches: the economy of transaction costs, which has contributed to the analysis of the different modes of organization and to the understanding of the trade-offs between these modes, and agency theory, which focuses primarily on how to design incentives that can bring about the convergence of heterogeneous and even opposing interests of interdependent parties. Hart and Holmström (Citation1987) and Salanie (Citation1997) analysed agency theory and related models. They present an overview of the work relating to the economics of transaction costs. A more general analysis of the main approaches to contract theory can be found in the work of Furubotn and Richter (Citation2010) and Brousseau and Glachant (Citation2002).

Efficiency is at the centre of the arguments of transaction cost theory and constitutes one of the main reasons for contracting, given the productivity gains that favour the improvement of management skills, that of transfers of technology and that of coordination. The coordination of investments and the control of processes are essential to guarantee the quality of agricultural products and optimize the use of production capacities and the resulting economies of scale. According to Key and McBride (2003), for example, production contracts in the pork sector are associated with increases in productivity, while Morrison Paul et al. (Citation2004) find that smaller farms and those that make relatively little use of contracts are less efficient than larger farms that use agreements more. These authors believe that efforts to regulate contracts can have significant economic costs, but they also note that limiting environmental damage remains an important regulatory task.

2.3. Theoretical and empirical syntheses on contract theory

The concept of contract farming is used in two areas. First, in the area of land where it designates all the contractual arrangements between landowners and farmers. The second area is that of the marketing of agricultural products where it constitutes a mode of arrangement between buyers of agricultural products and farmers. It is the latter type of arrangement that is studied in this article. According to Binswanger et al. (Citation1995), contract farming is an agreement between a farmer and a buyer, established before the production season, for a specific quantity and quality of the product, with its delivery date at a price. Frequently preset. The contract provides the producer with the assured sale of his production and sometimes with technical and financial assistance (credit, technology, inputs) from the buyer; the buyer guarantees a regular supply of the product (Binswanger et al., Citation1995; Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001; Bijman et al., Citation2012). Glover and Kusterer (Citation1990) make a specification by mentioning that contract farming does not take into account the cases where the buyer is a public or parastatal enterprise. According to Kpenavoun Chogou and Gandonou (Citation2009), contract farming is mainly maintained by traders. The agricultural contract is an agreement, between one or an association of farmers and one or more traders, by which the latter undertake to buy the production of the former under the guarantee of certain clearly predefined terms. This is what we could call the future market. The agricultural contract generally specifies the following elements: the duration of the contract, the quality of the product, the quantity to be supplied, the date of delivery of the product, the sale price or its fixing mechanism and the conflict resolution procedures (Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001; Laramee, Citation1975. Little, Citation1994). The contract tends to reduce the field of uncertainty that arises when two individuals want to cooperate. It usually sets out the responsibilities and obligations of each party, the methods of application and the remedies in the event of breach of contract (Eaton & Shepherd, Citation2001). In agriculture, the buyer is generally a trader or an agro-food company. The contract can be formal or informal. It is said to be formal when it is written and informal when it is verbal. Well-organized contract farming provides these links and would seem to offer an important opportunity for commercial production for smallholders. Likewise, it also offers investors the opportunity to guarantee a reliable supply, both in terms of quantity and quality Jackson and Cheater (Citation1994). Contract farming can be defined as an agreement between farmers and agribusiness or marketing companies, or both, for the production and supply of agricultural products under forward agreements, often at predetermined prices. Invariably, the agreement also commits the purchaser to provide production support to some extent through, for example, input supplies and technical advice (Kinsalla, Citation1987). These agreements are based on a reciprocal commitment: the farmer provides a specific commodity in quantities and according to quality standards determined by the buyer; the company supports the farmer’s production and purchases this commodity (Grossman, Citation1998). Contract clauses: a-) the producer and the buyer agree on the terms of the future sale and purchase of a crop or animal product; b-) Resource clauses: Together with marketing agreements, the buyer agrees to provide selected inputs, sometimes including land preparation and technical advice and c-) management clauses: producer agrees to follow recommended production methods, input regimes and growing and harvesting arrangements. Well managed, contract farming helps develop markets and transfer technical skills with as much benefit for promoters as for farmers. This approach is widely used, not only for tree and cash crops, but also, increasingly, for fruits and vegetables, poultry, pigs, dairy products and even shrimp as well as fish. Contract farming is characterized by its “extreme diversity” which relates not only to contracted products but also to the many ways in which it can be practiced. The contract farming system should be seen as a partnership between the agro-industry sector and farmers. To be successful, it requires a long-term commitment from both parties. Unfair agreements made by leaders are likely to be of limited duration and may jeopardize agro-industrial investments. Likewise, farmers should consider that adhering to contractual agreements will likely benefit them in the long run (Hammer & Muchow, Citation1994; Heald, Citation1988). Indeed, in developing countries, studies have revealed several factors that determine the adoption of agricultural contracts. So, Dubois (Citation2001) shows that agricultural contracts in developing countries highlight the hypotheses and the limits of the theoretical models used, as well as the relative weakness of the empirical questions addressed. The criticisms exposed underline the difficulties of the research but also show some little or not explored avenues that it seems relevant to study. Among the theoretical approaches, the author notes the importance of the hypotheses concerning information asymmetries, preferences with regard to risk, transaction costs, the static or dynamic framework of the model, the multiplicity of tasks, the type of delegation, completeness of contracts and institutional constraints (linear contracts, financial constraints, limited liability, contracts linked to various markets). A relatively concise review of the economic literature on agricultural contracts relating to the market; agricultural productions; producers and contract agents. We try to highlight its advances and shortcomings both theoretical and empirical, offering a very different perspective from existing literature reviews on the subject. Chiappori and Salarié (Citation1996) review a very interesting literature review on empirical tests of contract theory in general, of which agricultural contracts constitute a very important field of application. The other fields of application of contract theory are very diverse, ranging from vertical relationships in the industry with franchise contracts (Slade, Citation1996), forms of remuneration for agricultural work (Foster & Rosenzweig, Citation1994; Paarsch & Shearer, Citation1999) or heads of large companies (Baker et al., Citation1994), regulation of public enterprises, automobile insurance contracts (Chiappori & Salanié, Citation2000a), agricultural contracts between producers and manufacturers (Knoeber & Thurman, Citation1994) or between owners and operators (Allen & Lueck, Citation1992). This is not an exhaustive review of the results obtained in the literature (see Otsuka et al., Citation1992; Singh, Citation1989; Otsuka & Hayami, Citation1988; Bardhan, Citation1984, Citation1989; Hoff et al., Citation1993, for complementary reviews although not incorporating recent developments) but rather to present in a synthetic way the essential approaches of theoretical and empirical articles dealing with agricultural organization, in particular, the land and labor markets in the developing countries. In addition, the various existing journals often lack perspective with respect to this literature and absolutely do not offer the perspective described here aimed at highlighting the (often implicit) hypotheses and limits of theoretical models as well as the relative weakness of the empirical questions discussed. The purpose of the criticisms that we expose is to underline the difficulties of the research but also to show some little or not explored ways that it seems relevant to study. The vast majority of theoretical models use the Principal-Agent model. Most of them show under what conditions and constraints sharecropping or tenant farming contracts are optimal and possibly Pareto effective. The results of all these models depend on course on the assumptions made on the different markets and the concepts of solutions adopted. By placing the models in the more general theoretical framework of contract theory, we can characterize them according to the assumptions concerning information asymmetries, risk preferences, transaction costs, static or dynamic framework of the model, the multiplicity of tasks, the type of delegation: total or partial, considered as exogenous or endogenous, the completeness of contracts and institutional constraints (linear contracts, financial constraints, limited liability, contracts linked in various markets, etc.). With regard to numerous empirical studies, we will summarize the main questions they try to answer, the main results and the limits used, citing the most interesting corresponding studies.

2.4. Choice of variables of interest related to the hypotheses to be tested

Based on the review of previous empirical studies, the study identifies a number of variables as determinants of the decision to participate in the contract by actors in the “parboiled rice” value chain in the commune of Glazoué (Figure ). First, three socio-demographic variables: the farmer’s or processor’s age, level of education and professional experience can be explanatory factors for the adoption of the contract. Regarding the effect of age, there is a divergence in the results obtained by the authors in the literature. According to a study conducted by Arouna et al. (Citation2015) in the same area, age negatively affects the participation in the contract and the income of rice producers, while some authors maintain a positive relationship between age and adoption of rice agricultural innovations. Given the low level of education of rural populations, the latter are not often dynamic in terms of access to information and anticipation of risk. It can therefore be agreed that age reduces the adoption of contracts because elderly head of household (CM) has a shorter planning horizon and has a less long-term vision. In this connection, we will verify the following hypothesis H1: the younger the actor, the more the probability of participation in the contract increases and the effect of participation on income increases.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of contract farming.

The level of education increases the ability to understand risk information and anticipate risk. Nowadays, it is established that, to have a good understanding of the terms of a contract and to guarantee a good performance of the contract, the participant must have a minimum level of education which can promote his “communication skills”. We can consider that the most educated individuals have more information that allows them to better assess the proposals contained in the contract and anticipate possible risks in order to limit their level of uncertainty and risk. Contrary to the result of Arouna et al. (Citation2015) which does not find a significant link between the formal education of producers and the adoption of contracts, the study puts forward the following hypothesis to verify, H2: plus the number of educated value chain actors, the higher the probability of participating in the contract as well as the effect on income.

The importance of the number of years of experience is not enough clear. For some authors, experience plays a positive role in the decision-making process of innovating (while for others the effect is negative). As far as farmers are concerned, we can admit that the farmers most experienced in rice production have already accumulated certain experiences in terms of agricultural risks. Therefore, they will quickly understand the benefits of the contract and easily join. The study therefore verifies hypothesis H3: the more the number of years of experience of the actors in the chain increases, the more the probability of adhesion to the contract increases.

Distance to the nearest market can also influence the desire to participate in the farming’ contract. The transport cost is proportional to the distance from the actor production site to the nearest market. It therefore determines the level of transaction costs that determine the level of rationality of the actor (Arouna et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it can be accepted that the distance which separates the individual from the market is a key decision factor since it determines the transaction costs.

The second wave of variables relates to institutional and informational contexts. It concerns both the presence of a support structure for contracting and contact with extension agents. These variables could negatively or positively influence the decision to contract. One producer or processor supervised and monitored by support and extension institutions would be more favourable to change than the others (Eastwood et al., Citation2017). As a result, the role of extension services in disseminating information is a key factor influencing the likelihood of adoption and the income of actors. Belonging to a cooperative or an association of actors gives you an idea of the advantages and disadvantages of contracting. The collective dissemination of an innovation can encourage certain farmers or processors to adopt contracts in their transactions. So a positive effect would be expected from this variable on adoption and income. The last variables to be tested in this study are the quality of the inputs and products traded the price at which the contract is established.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

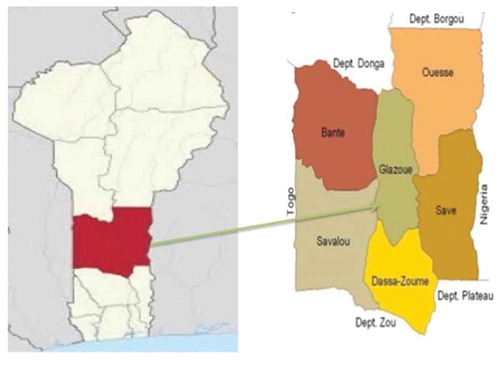

The commune of Glazouè is a rural area located in the heart of the Collines department and the commune is 234 km from Cotonou, the economic capital of Benin. It is limited to the North by Ouèssè and Bassila, to the South by Dassa, to the East by Ouèssè and Savè and to the West by Bantè and Savalou. The Municipality has 48 administrative villages distributed in 10 districts which are Aklampa, Assanté, Glazoué, Gomé, Kpakpaza, Magoumi, Sokponta, Ouèdèmè, Thio and Zaffé. The territory of the Communes covers an area of 1,750 km2 with a density of approximately 51 inhabitants per km2 (Figure ). With a sub-equatorial climate, the commune experiences two rainy seasons including one small and two dry seasons including one small. The mean rainfall varies between 959.56 and 1255.5 mm; the average temperature varies between 24°C and 29°C.

The relief is dominated by plateaus (200 to 300 m) and by hills in places (Sokponta, Gomé, Camaté, Tankossi, Tchatchégou, Thio, Ouèdèmè, Assanté and Aklampa). These hills constituting tourist assets of the departments of the Collines.

3.2. Data collection and sampling procedure

The data used in this study come from a survey that was carried out in the commune of Glazoué in the Collines department in central Benin. It made it possible to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. The random sampling technique was used to build the sample. After identifying the actors, a random selection of respondents was made by the category of the actor. This random choice consists in first having the complete list of actors belonging to each link, assigning them numbers and then, randomly drawing the number of respondents desired. Thus, we surveyed a total of 200 people at the rate of 150 actors using contracts and 50 not using contracts. The configuration of the sample is presented in Table in the appendix:

Table 1. Composition of the sample by link

3.3. Empirical model

The econometric model employed in this study falls within the domain of qualitative variables, more precisely selection models. The effect of contractualization on income only applies to the subsample of actors who have adopted contracts. The model explaining the effect of the adoption of contracts on the income of actors has been schematized below to facilitate understanding (Table ).

Table 2. Model of the empirical analysis

We can consider this model as a two-stage model. At first, the individual chooses to participate in the contracts or not; then, if applicable, it indicates the income obtained from the rice production activity during the marketing year considered. This approach is similar to that of the two-part models. As said above, it is when the respondent has adopted a contract that we can seek to study the effect of this contractualization on their annual income. Using the method developed by Heckman (Citation1997),Footnote1 our model can be formalized as follows for each individual i.

3.4. Decision to adopt the contract (Selection equation)

We observe only if the individual i has adopted the contract

Estimated annual income: (substantial equation)

, observable only if

; (2)

With and

, observable socio-demographic variables,

according to a normal law

,

a normal law

,

correlation coefficient of the error terms. This model developed by Heckman is suitable in the case of selection bias. The advantage of this model is that it allows the adoption and adoption of the income impact model to be estimated simultaneously (Table ).

Table 3. Presentation of the variables

The estimation of these equations is made by the Maximum Likelihood Estimation Method under the Stata13 software.

4. Results

4.1. Characterization of adopters of contract farming

The characteristics of the actors who use the contract as a mode of exchange between them are as follows:

4.1.1. Production link

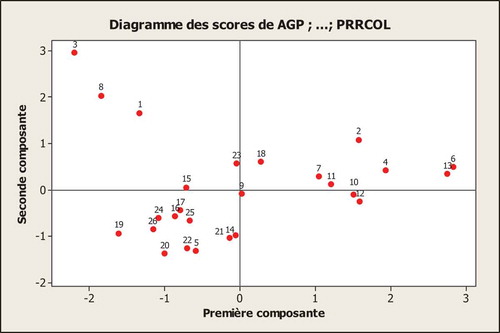

Two main components with a cumulative eigenvalue of 76.9% were chosen. Thus, 76.9% of the variations observed within producers are explained by these two-factor components. The remaining 23.1% would be due to other parameters not taken into account in this classification. Figure (in the appendix) illustrates the presentation in the factorial foreground of the actors concerned. The observation in Figure highlights two categories of producers adopting contract farming. It is:

Category 1: This category is made up of relatively young actors. The average age is 37 years with 7 years of rice production experience. They plant about 1 ha of rice for a yield of 2,126 kg/ha. This category adopts contract farming with the aim of easily accessing the means of production (inputs, training, credit, etc.) in order to increase their holdings.

Category 2: it is made up of older players, with an average age of 62 years with an average experience in rice production of 32 years. They sow small areas (less than 1 ha) for yields fluctuating around one (1) tone per hectare. They mainly use the hired workforce or delegate their responsibilities to their son to conduct operations on the farm. The concern of accessing agricultural credits and production inputs could explain their adherence to contract farming. Note that these producers, whether they belong to category 1 or 2, all belong to the same producer group.

4.1.2. Transformation link

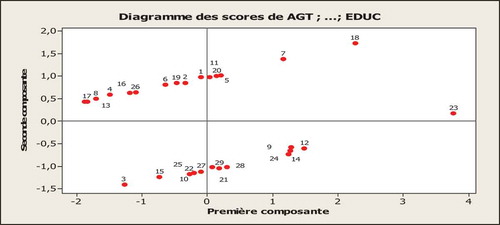

Two factorial components were sufficient at this level to classify the actors adopting contract farming. These components made it possible to explain 85.6% of the variations observed between the two groups of actors highlighted. See the factorial foreground representation of the respondents in Figure (in the appendix). Two groups of female processors adopting contract farming have been identified. The first group is made up of more or less young women processors, with an average age of 42 years; an average experience of 7 years in rice processing. The processors in this category are all educated. They have at least the primary level. The second group is made up of women processors slightly older than their counterparts (47 years old), demonstrating 10 years of experience in rice processing. Most of them are uneducated. Only 7.7% received formal education.

4.2. Results of the econometric analysis

4.2.1. The factors of adoption of the contract

The parameters of the heckprobit model are estimated by the maximum likelihood optimization technique (Table ).

Table 4. Results of binary Logit regressions

One of the basic hypotheses relating to the choice of our estimation method is the independence of the explanatory variables. Violation of this assumption would create a multicollinearity problem which could cause biased estimates of the model coefficients and would risk inflating the values of their respective variances. In order to ensure the absence of this problem, we resorted to the statistical test proposed by Farrar and Glauber (Citation1967) which tests the null hypothesis of the orthogonality of the vectors of the explanatory variables against the alternative hypothesis of the dependence of these variables. The statistic used in this test is: which follows the law of

, where N is the sample size, K the number of explanatory variables and ln (d) is the natural logarithm of the determinant of the correlation coefficient matrix. In our case, the value of

is equal to 103.63. Our results suggest that the empirical value of the Farrar and Glauber statistic is 42.72. This value is lower than the tabulated value of

= 103.63; therefore, we accept the null hypothesis of absence of multicollinearity, which confirms that our variables explanatory statements are statistically independent.

4.2.2. Production link

An analysis of the results (Table ) shows that the model chosen overall seems well specified because the Wald specification test revealed a statistic of chi2 (45) = 21.31 and significant at the 5% level. The independence test of the model equations (selection equation and substantial equation) confirmed the existence of a dependence between the two equations with an insignificant chi2 (1) = 0.38 statistic. This dependence on equations means that the decision to adopt contracts and the effect on income are not independent of each other.

The coefficients of the selection equation (adoption) are interpreted like those of a Probit model. As for the coefficients of the substantial equation (income effect), they represent the change in the dependent variable following a change in the explanatory variable, i.e. a marginal effect. The interpretation of the coefficients of the selection model (adoption) allows us to notice at the level of this link that out of the eight explanatory selection variables introduced, four are significant.

Variables introduced into the model, belonging to a producer group, contact with a supervisor, the desire to access markets, the desire to access good quality products are positively significant at the threshold of 1%.

Membership of a producer group: this variable is positively significant at the 1% threshold (p = 0.0001). We therefore deduce that it positively influences the decision of a producer i to adopt contract farming or not. Thus, when we go from a producer who does not belong to a group to another member of a producer group, the likelihood of adopting contracts increases. This result could be explained by the fact that the producer belonging to a group has an easier time signing a contract than the one who practices individually. This membership leaves a certain guarantee in the eyes of the partner with regard to compliance with the terms of the contract. This result allows the study to emphasize the importance for actors with various links to build networks to facilitate exchanges with other actors. These results diverge from those of Bouzid and Cheriet (Citation2019) who established that membership in an association by producers has no significant influence on the willingness of producers to adopt agricultural innovations. Groupings or Cooperatives are the only ones eligible for campaign credits from formal microfinance institutions, which increase their incentive to contract. This positive effect (expected) on joining a producer organization on the adoption of contracts has also been proven by Diouf Sarr et al. (Citation2018) on the adoption of improved seed in Senegal.

Contact with an extension agent: also positive and significant at the 1% threshold (p = 0.0001), the variable contact with a supervisory agent positively influences the adoption of contractualization at the producer level. Indeed, a producer who has access to a supervisor is more likely to adopt contractualization than one not supported by an extension agent. This could be due to the fact that from the advice this agent would give him, the producer has more confidence in the terms of the contract. This result implies that producers still need technical assistance during the process of adopting agricultural innovations. The adoption of contracts with processors is something new for the producer because it brings a change in his usual behaviour.

The distance to the nearest outlet market to the producer area; this variable is positively significant at the 1% threshold (p = 0.001). The producer who has difficult access to the market is more inclined to sign a contract than the one who sells his products easily. This positive relationship between the signing of a contract and the search for the market is only the consequence of the behaviour of a rational economic agent who is in the permanent search for profit. The more easily he enters the market, the greater his income.

Access to good quality products: it is also positive and significant at the 1% threshold (p = 0.003). A producer who does not have access to good quality raw materials is more likely to sign a contract. On the other hand, those who are already satisfied with the quality of the raw materials used in their operations, no longer find it sufficiently motivated to go for contracts. We deduce that the intention/desire to access good quality products positively influence the adoption of contract farming at the production link level.

The coefficients associated with the age and the experience of the producer are not statistically significant. This result therefore means that these variables do not determine the producer’s decision to contract its transactions with the rice steamers. Consequently, the hypotheses (H1 and H3 are invalidated). This result then confirms those of Bouzid and Cheriet (Citation2019) who showed that the age variables and the experience of the producer have no considerable effect on his predisposition to adopt new technologies. The variable “level of education” as expected has a positive and significant influence on the probability of adoption of contracts. Thus, hypothesis H2 is confirmed. The higher the number of educated value chain actors, the higher the probability of participation in the contract as well as the effect on income. This positive influence is explained by the fact that producers with formal education have more opportunities on the existence of support projects for contracting only those who have not received formal education. The latter showed that young producers in the Senegal River Valley, a higher level of education than we once knew in the world, are open to technological innovations but remain very critical. These ideas are also approved by the work of Diouf Sarr et al. (Citation2018).

As for the results of the income effect, only the variable contact with a supervisor reveals a positive marginal effect on the income of adoptive producers. This result constitutes a strong point of this study which clearly shows the capital importance of the support of a support structure for the contractualization of the different transactions at the producer level. The agricultural policy must therefore take into account this essential aspect, which is the supervision of producers in the process of changing attitudes.

4.2.3. Transformation link

An analysis of the results (Table ) shows that the model chosen seems generally well specified because the Wald specification test revealed a statistic of chi2 (45) = 6.23 and significant at the threshold of 5%. The independence test of the model equations (selection equation and substantial equation) confirmed the existence of a dependence between the two equations with an insignificant chi2 (1) = 0.975 statistic. This dependence on equations means that the decision to adopt contracts and the effect on income are not independent of each other.

The interpretation of the coefficients of the selection model (adoption) allows us to notice at the level of this transformation link that of the seven (07) variables introduced into the model, five (05) were found to be positively significant, including four (4) at 1% threshold and one (01) at the 5% threshold. Membership of a group, access to management, access to the market and the search for good quality products are significant and positive at the 1% threshold. The gender of the respondent is positively significant at the 5% level.

Membership of a women’s group: just as in the previous case, membership of a women’s group has a positive influence on the adoption of agriculture. A woman member of a group of processors is more likely (p = 0.0001) to adopt contractualization than another who is not. This membership of the processor in a group gives it more credibility in the eyes of the partner with whom it plans to contract. In the commune of Glazoué, parboiled women benefited from the support of the Agricultural Diversification Support Project (PADA) and the Agricultural Productivity Project in West Africa (WAAPP) financed by the World Bank. These projects only support activities carried out in a cooperative or in the association between actors. This positive effect of this variable can therefore be justified by the fact that in cooperatives, par boilers are more likely to benefit from the support of development projects and programs to advance in their activity.

Contact with a supervisor: also positive and significant at the 1% threshold. The transformer receiving advice from an extension worker or support structure is more likely to adopt the contacts than one who is not in contact with anyone. This would be due to the different advice that the latter gives him. Contractualization allows processors to guarantee the supply of raw materials regardless of the fluctuations in the real price on the market. This allows them first to continuously conduct the parboiling activity without experiencing stock-outs of raw materials.

Market access: market access is also positively significant at the 1% threshold. Thus, it should be remembered that the processor who finds it difficult to sell her products is more likely to sign a contract than the one who easily sells her products. Likewise, the more difficult it is for the processor to access good quality raw materials, the more likely she is to sign a delivery contract with any supplier who can deliver good quality products to her.

It should be noted that at the level of processors adopting the contracts, three variables revealed positive effects on their income. These are among others the variables belonging to a group, facilitating access to the market, access to good quality products (rice). The interpretation of these results allows us to say that, the more the processors get in the association, they manage to obtain the raw materials at good prices, which significantly increases their net income. The quality of the raw materials which naturally form the subject of the points of the contract significantly influences the income of the processors; this result is easy to understand because the aspect of the quality of the raw materials is based on the elements which motivate them to participate in the contracts.

5. Concluding remarks

The results of this study show that several factors, both intrinsic to contractualization and to the socio-economic characteristics of the actors, influence its adoption. Membership of a producer group, access to the market, access to good quality products and contact with an extension agent and access to formal education are among other factors that determine the adoption of contracting within the parboiled rice value chain of Natitingou. These results confirm the adoption theory which states that the adoption of a technology depends both on the characteristics specific to this technology and those specific to potential adopters.

Also, the results have shown that contractualization has a positive effect on the performance of actors in the value-added parboiled rice chain. It leads to a modest increase in the income of adopters. These results are consistent with those of Arouna et al. (Citation2015) who found that the informal agricultural contract has a positive impact on the income of contract producers in the commune of Glazoué. These results are also similar to those of Sale et al. (Citation2014) who conclude that contract farming has positive effects (benefits) on the economic performance of African producers south of the Sahara. Depieu et al. (Citation2017) also have results similar to ours. At the end of their study, they found that the contracts allow producers of maize in West Cameroon to access good quality inputs at low prices and to access lucrative markets with prices per kg higher than those applied out of the contract. As a result, the contracts signed by maize producers and other actors improve their incomes and consequently their living conditions. The results of this research have shown that it is still possible to improve the rate of adoption of contracts in the Glazoué area and this in a considerable way by implementing a strategy to identify producers and processors likely to adopt contracts. To achieve this, it would therefore be essential to define an appropriate institutional framework to support this mode of governance of the value chain. It would be just as important to favour producers who are affiliated with organizations because it has been shown that membership in an organization is crucial for the adoption of contracts. All these measures must be accompanied by access to incentive credits from financial structures or support structures for producer organizations. Programs to promote improved technologies must also include activities to strengthen education at the level of producer groups with the aim of increasing the chances of adopting contracts and especially at the level of transformers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ichaou Mounirou

Professor Ichaou Mounirou is a Lecturer-researcher at the University of Parakou in Benin and holds a PhD from the University of Abomey Calavi in Benin and the University of “Ouest Timişoara” in Romania. His research interests focus on development economics including mainly agricultural and environmental economics. He published many papers from those fields in international journals. In addition, he was involved in several research and teaching programmes relating to development economics in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Notes

1. For more details, see Heckman (Citation1997), Winship (Citation1992).

References

- Adégbola, P., Ahoyo Adjovi, N., Allagbé, M., Houssou, P., Bankolé, A., Djidonou, S., ... & Guédou, E. (2014a). Étude relative à la filière riz: Elaboration d’un document référentiel. Première partie: Synthèse bibliographique des travaux effectués sur le riz et la riziculture au Bénin. Document Technique et d’Informations. INRAB/MAEP/CTB-Bénin, 412 p. Dépôt légal N° 7513 du 15 octobre 2014, 4ème trimestre. Bibliothèque Nationale (BN) du Bénin. ISBN: 978–99919–0-135-0. Le document technique et d’informations est en ligne (on line) sur les sites web.

- Adégbola, P., Ahoyo Adjovi, N., Allagbé, M., Houssou, P., Bankolé, A., Djidonou, S., ... & Guédou, E. (2014b). Étude relative à la filière riz: Elaboration d’un document référentiel. Deuxième partie: Analyse bibliographique critique des travaux effectués par domaine sur le riz et la riziculture au Bénin. Document Technique et d’Informations. INRAB/MAEP/CTB-Bénin, 69 p. Dépôt légal N° 7514 du 15 octobre 2014, 4èmetrimestre. Bibliothèque Nationale (BN) du Bénin. ISBN: 978–99919–0-136-7. Le document technique et d’informations est en ligne (on line) sur les sites web.

- Allen, D. W., & Lueck, D. (1992). Contract choice in modern agriculture. Cash Rent versus Crop Share, Journal of Law & Economics, 35(2), 397–19.

- Arja, M. R., Tozanli, S., & Palpacuer, F. (2004). Dynamiques des apprentissages inter-enterprises et compétitivité des entreprises régionales: Cas des vins dans le Languedoc-Roussillon. Dynamiques des apprentissages inter-enterprises et compétitivité des entreprises régionales, 1000–1019.

- Arouna, A., Olounlade, O. A., Diagne, A., & Biaou, G. (2015). Evaluation de l‟ impact des contrats agricoles sur le revenu des producteurs du riz: Cas du Bénin. Annales des sciences agronomiques, 19(2), 617–629.

- Baker, G., Gibbs, M., & Holmstrôm, B. (1994). The internal economics of the firm: Evidence from personnel data. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118351

- Bardhan, P. (1984). Land, labor and rural poverty: Essays in development economics. Oxford University Press.

- Bardhan, P. (1989). The theory of agrarian institutions. Oxford Clarendon Press.

- Bijman, J., Iliopoulos, C., Poppe, K. J., Gijselinckx, C., Hagedorn, K., Hanisch, M., Hendrikse, G. W. J., Kuhl, R., Ollila, P., Pyykkonen, P., & van der Sangen, G. (2012). Support for farmers’ cooperatives. Rapport de l’Union européenne.

- Binswanger, H., Deininger, K., & Feder, G. (1995). Power, distortions, revolt and reform in agricultural land relations. In J. Behrman & T. N. Srinivasan (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (pp. 2659–2772). Elsevier Science, and Amsterdam.

- Bouzid, A., & Cheriet, F. (2019). Les déterminants de l’adoption de nouvelles variétés de semences de tomate en Algérie. Systèmes alimentaires/Food Systems, (2019(4), 115–137.

- Brousseau, E., & Glachant, J. M. (Eds.). (2002). The economics of contracts: Theories and applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Chiappori, P. A., & Salanié, B. (2000a). Testing for asymmetric information in insurance markets. Journal of Political Economy, 108(1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/262111

- Chiappori, P. A., & Salarié, B. (1996). « Empirical contract theory: The case of insu rance data ». Document de travail CREST, n° 9639.

- Depieu, M. E., Arouna, A., & Doumbia, S. (2017). Analyse diagnostique des systemes de culture en riziculture de bas-fonds a Gagnoa, au centre ouest de la Cote d’Ivoire. Agronomie Africaine, 29(1), 79–92. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/aga/article/view/164163

- Diouf Sarr, N. S., Basse, B. W., & Fall, A. A. (2018). Taux et déterminants de l’adoption de variétés améliorées de riz au Sénégal. Économie rurale. Agricultures, alimentations, territoires, (365), 51–68.

- Dossouhoui, F. V. (2019). Développement d’un secteur semencier intégré aux chaînes de valeur du riz local au Bénin (Doctoral dissertation), Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech Université de Liège.

- Dubois, P. (2001). Contrats agricoles en économie du développement: Une revue critique des théories et des tests empiriques. In Revue d’économie du développement, 9e année N°3 (pp. 75–106).

- Eastwood, J. P., Biffis, E., Hapgood, M. A., Green, L., Bisi, M. M., Bentley, R. D., Wicks, R., McKinnell, L.-A., Gibbs, M., & Burnett, C. (2017). The economic impact of space weather: Where do we stand? Risk Analysis, 37(2), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12765

- Eaton, C., & Shepherd, A. (2001). Contract farming: Partnerships for growth (No. 145). Food & Agriculture Org.

- Farrar, D. E., & Glauber, R. R. (1967). Multicollinearity in regression analysis: The problem revisited. Review of Economics and Statistics, 49(1), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/1937887

- Fiamohe, R., & de FRAHAN, B. H. (2012). Transmission des prix et asymétrie sur les marchés de produits vivriers au Bénin. Région et Développement, (36-2012).

- Foster, A., & Rosenzweig, M. (1994). A test for moral hazard in the labor market. 7C6o, n t2r1a3c-t2u2a7l. Arrangements, Effort, and Health, Review of Economics and Statistics, 213-227. DOI: 10.2307/2109876

- Furubotn, E. G., & Richter, R. (2010). Institutions and economic theory: The contribution of the new institutional economics. University of Michigan Press.

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290500049805

- Gereffi, G., & Korzeniewicz, M., Eds.. (1994). Commodity chains and global capitalism (No. 149). ABC-CLIO.

- Glover, D., & Kusterer, K. (1990). Small farmers, big business: Contract farming and rural development. Macmillian.

- Grossman, L. S. (1998). The political ecology of bananas: Contract farming, peasants and agrarian change in the Eastern Caribbean. University of North Carolina Press.

- Hammer, G. L., & Muchow, R. C. (1994). Assessing climate risk to sorghum production in water-limited subtropical environments: Development and testing of a simulation model. Field Crops Research, 36(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4290(94)90114-7

- Hart, O. D., & Holmström, B. (1987). The theory of contracts, in (Bewley, T. eds.) advances in economic theory: Fifth world congress.

- Heald, S. (1988). Tobacco, time and the household economy in two Kenyan societies (manuscrit non publié). Department of Anthropology, Lancaster University, Royaume-Uni.

- Heckman, J. (1997). Instrumental variables: A study of implicit behavioral assumptions used in making program evaluations. Journal of Human Resources, 32(3), 441–462. https://doi.org/10.2307/146178

- Hoff, K., Braverman, A., & Stiglitz, J. (1993). The economics of rural organization. Oxford University Press.

- Jackson, J. C., & Cheater, A. P. (1994). Contract farming in Zimbabwe: Case studies of sugar, tea, and cotton. In P. D. Little & M. J. Watts (Eds.), Living under contract: Contract farming and agrarian transformation in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 140–166). University of Wisconsin Press.

- Kinsalla, K. (1987). Problems for sub-contractors. In Common problems with construction contracts (pp. 25–52). College of Law, Sydney..

- Knoeber, C. R., & Thurman, W. N. (1994). Testing the theory of tournaments: A17n9. Empirical analysis of broiler production. Journal of Labor Economics, 12(2), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1086/298354

- Kpenavoun Chogou, S., & Gandonou, E. (2009). Impact of public market information system (PMIS) on farmer’s food marketing decisions: Case of Benin.

- Laramee, P. A. (1975). Problems of small farmers under contract marketing, with special reference to a case study in Chiangmai Province, Thaïlande. Economic Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific, 2(26), 43–57.

- Little, P. D. (1994). The development question. In P. D. Little & M. J. Watts (Eds.), Living under contract: Contract farming and agrarian transformation in sub- Saharan Africa (pp. 216–257). University of Wisconsin Press.

- MAEP. (2013). Plan Stratégique de Relance du Secteur Agricole. Report.

- Masten, S., & Saussier, S. (2000). Econometrics of contracts: An assessment of developments in the empirical literature on contracting. Revue d’économie industrielle, 92(1), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.3406/rei.2000.1048

- Morrison Paul, C. J., Nehring, R., & Banker, D. (2004). Productivity, economies, and efficiency in US agriculture: A look at contracts. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 86(5), 1308–1314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0002-9092.2004.00682.x

- Olounlade, A. O., Aminou, A., Aliou, D., & Biaou, G., (2011). « Evaluation de l’impact des contrats agricoles sur le revenu des producteurs du riz », cas du Bénin. Rapport scientifique, INRAB

- Otsuka, K., Chuma, H., & Hayami, Y. (1992). Land and labor contracts in agrarian economies: Theories and facts. Journal of Economic Literature, 30(4), 1965–2018.

- Otsuka, K., & Hayami, Y. (1988). Theories of share-tenancy: A critical survey. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 37(1), 31–68. https://doi.org/10.1086/451707

- Paarsch, H., & Shearer, B. (1999). The response of worker effort to piece rates: Evidence from the British Columbia tree-planting industry. Journal of Human Resources, 34(4), 643–667. https://doi.org/10.2307/146411

- Palpacuer, F. (2000). Competence-based strategies and global production networks. Competition & Change, 4(4), 1–48.

- PSDSA. (2016). Plan Stratégique de Développement du Secteur Agricole. Report.

- Salanie, B. (1997). the economics of contracts. MIT Press.

- Sale, A., Folefack, D. P., Obwoyere, G. O., Wati, N. L., Lendzemo, W. V., & Wakponou, A. (2014). Changements climatiques et déterminants d’adoption de la fumure organique dans la région semi-aride de Kibwezi au Kenya. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 8(2), 680–694. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v8i2.24

- Singh, N. (1989). Theories of sharecropping, in the theory of agrarian institutions, P. Bardhan (ed). Oxford Clarendon Press.

- Slade, M. (1996). Multitask agency and contract choice: An empirical exploration, international economic review.

- Tozanli, S., & El Hadad, F. (2007). Gouvernance de la chaîne globale de valeur et coordination des acteurs locaux: La filière d’exportation des tomates fraîches au Maroc et en Turquie. Cahiers Agricultures, 16(4), 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1684/agr.2007.0110

- Vavra, P. (2009). Role, usage and motivation for contracting in agriculture. OECD publishing.

- Winship, C., & Mare, R. D. (1992). Models for sample selection bias. Annual review of sociology, 18(1), 327 350. doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001551 1 18 doi:10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.001551