?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes are contractual arrangements where a large farmer (nucleus farmer) who is well-resourced takes charge of smaller farmers by providing them with the necessary training on agronomic practices and some farm inputs for production. The study assesses the effects of nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on profitability among smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana. A total of 330 smallholder farmers made up of 150 outgrowers and 180 non-outgrowers were interviewed using structured questionnaires. A comparative analysis is made between outgrowers and non-outgrowers. The study employs the binary logit regression model to identify the factors influencing participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes and the propensity score matching technique to estimate the effect of nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on profitability of smallholder farmers. The study reveals that the factors that significantly influence smallholder farmers’ participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes are gender, marital status, farm size, membership of an FBO and extension contact. Gender and marital status of a farmer have negative influence on participation whilst farm size, membership of an FBO and extension contact have positive influence on participation. It was also revealed that nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes have significant positive effect on smallholder farmer’s gross margins, net margins and returns on investment. The study recommends that, nucleus farmers and other stakeholders who are involved in developing outgrower schemes or similar initiatives should take into consideration the social and demographic characteristics of the target farmers to enhance participation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The article titled “Effects of Nucleus-Farmer Outgrower Schemes on Profitability among Smallholder Farmers: Empirical Evidence from Northern Ghana” is an academic research article conducted in Ghana which seeks to highlight the importance of participation in Nucleus-Farmer Outgrower Schemes. It has been concluded from the study results that, smallholder farmers who participate in these schemes are more profitable in their farm business due to timely acquisition of production inputs and prudent/efficient utilization of the inputs. The nucleus farmers provide these inputs to the outgrowers at a certain contractual arrangement. The study therefore recommends that stakeholders in the agricultural production value chain should replicate this model to ensure timely and efficient utilization of farm inputs to maximize farmers’ profitability.

1. Introduction

The incidence of poverty worldwide is decreasing drastically among some regions such as the Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Central Asia, Middle East and North Africa, East Asia and Pacific and South Asia (World Bank, Citation2015). The number of poor people in these regions continue to decline annually. However, the situation is different in Sub Saharan Africa where poverty seems not to be declining significantly. It is projected that, the number of poor people in sub-Saharan Africa is likely to increase by 2030 if appropriate measures are not put in place (World Bank, Citation2015). Various local initiatives with support from other donor organizations have been instituted particularly in agriculture and health sectors to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of ending poverty in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030. The effects of these measures have yielded little results as the situation keeps worsening. However, the poverty incidence in Ghana seems to be declining over the years but the number of poor persons and high depth of poverty is marked in districts in the northern half of the country (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], Citation2015).

It is clear that majority of the people in sub-Saharan Africa including Ghana engage in Agriculture for survival where most of them are found in the rural areas. These people constitute majority of the poor people in the region. In view of this, initiatives aimed at ending poverty are often targeted at the agricultural sector (Njogu et al., Citation2017). Farmers in these rural areas can increase their productivity and subsequently increase their profitability through access and the efficient use of input resources (technological change) (Njogu et al., Citation2017). Outgrower schemes have proven to be an effective model of transferring technology to poor farmers and have been implemented across Ghana especially in Northern Ghana (Schüpbach, Citation2014). The outgrower model popularly practiced in recent times across Africa is the nucleus-farmer outgrower model.

The nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme is where a large farmer (nucleus farmer) is well resourced and sometimes supported by development partners such as NGOs and government to take charge of smaller farmers by providing them with the necessary training on agronomic practices and some inputs such as seed, fertilizer, agrochemicals and mechanized services for production (Paglietti & Sabrie, Citation2012). Outgrower schemes are usually adapted to help solve the problems of capital and ready market for farmers (Felgenhauer & Wolter, Citation2009; Hussain & Thapa, Citation2016). The nucleus farmer is often expected to provide some farm inputs (improved seeds, fertilizer, agrochemicals among others) and mechanized services such as tractor services for land preparation, shelling, threshing, harvesting among others to support the farm activities of their outgrowers (Ntsiful, Citation2010; Rudy, Citation2010). This is usually accompanied by extension services whiles linking outgrowers to market opportunities.

Studies such as Ragasa et al. (Citation2017) suggest that smallholder farmers’ participation in outgrower schemes can be a good measure for policy analysis to examine the efficacy of agriculture inputs or credit delivery to farmers. Hussain and Thapa (Citation2016) for instance, found that participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes tend to relax credit fungibility and improve credit repayment. This is due to the direct interpersonal relationship with the creditors (nucleus farmers) and borrowers (outgrower farmers). The cost of credit (input resources) given under these contracts is often not measured to determine its burden on participants which may eventually affect their profitability.

The study focuses on the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes implemented by individual nucleus farmers with support from some agricultural projects in Northern Ghana. The nucleus farmers provide similar services to their outgrowers which are mainly tractor services, inputs provision such as improved seed, fertilizer and agrochemicals and extension services under similar conditions. The crop supported by the nucleus farmers are primarily maize and rice with maize being the predominant crop. Rice farmers are scarcely supported under the schemes. There is little or no spillover from outgrowers to the other farmers because the nature of the outgrower model is such that the nucleus farmers directly supervise the use of the inputs to ensure that outgrowers apply the inputs directly on their maize crops and not given to non-outgrowers or use for other purposes.

1.1. Problem statement

Outgrower schemes have existed for many years in several forms in Ghana. The objective for establishing such schemes is mainly to support smallholder farmers in acquiring productive farm inputs and extension contact. Literature revealed that some outgrower schemes improve farm incomes whiles others do not (Njogu et al., Citation2017; Wendimu et al., Citation2016). Meanwhile, there is limited empirical evidence on the impact of outgrower schemes on profitability of farmers especially with those implemented in Northern Ghana (nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes).

It has not been empirically tested to ascertain whether these outgrower schemes in Northern Ghana provide outgrowers with access to inputs, whether the extension services and inputs given under the schemes are able to improve the input use efficiency of outgrowers and whether the schemes enhance the profitability of smallholder farmers. As outgrower arrangements are very heterogeneous and may have diverse effects, there is a legitimate concern as to whether all kinds of outgrower arrangements offer economic benefits to participating smallholder farmers (Oya, Citation2012; Sivramkrishna & Jyotishi, Citation2008). These raise questions which are unaddressed by existing literature.

Stakeholders are therefore unable to make policy decisions regarding the adoption or rejection or amendments of such schemes to improve the livelihood of rural farmers. There is the need for such work to provide evidence of the various schemes provided to farmers in Northern Ghana. The study therefore performs a comparative analysis to determine the effect of nucleus farmer outgrower schemes on profitability among smallholder farmers.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical review

The theory that underlines the study is the production theory. The production function specifies a combination of factor inputs to produce a desired output. A rational producer will always want to maximise profit with limited combination of factor inputs. A profit maximizing firm chooses both its inputs and outputs levels with the sole goal of achieving maximum profits. Given a production function as:

Where Q is the quantity of output and X1, …, Xn are the quantities of input variables such as seed. With prices of inputs r for X1, then the firm’s profit is given by:

Where p and q are the prices and quantities of output respectively. The optimal set of the production actions on inputs and output is characterised by the condition such that:

For pq = revenue of the firm with its associated cost (C), then:

where R represents Revenue

EquationEquation (2.4)(2.4)

(2.4) specifies the profit maximization point in production where the marginal revenue is equal to the marginal cost. If MR > MC, there exist an optimal condition for the producer to increase production whereas if MR < MC, then the producer should decrease production since the additional cost incurred in producing the additional unit of output is greater than the added revenue obtained from the additional output.

In the firm’s profit maximization strategies there exists technological constraint which concerns the feasibility of the production plan and market constraint which concerns the effect of actions of other agents in the market. Therefore, in a perfect competitive market, a firm will take into consideration the prices of factor inputs to maximise its output. Assume that P is a vector of prices for inputs, then the profit maximization of the firm is expressed as:

If the firm produces only one output, the profit function can be written as:

Where p is the (scalar) price of the output, r is the vector of the factor prices and the inputs are measured by the (non-negative) vectors:

Therefore, the first-order condition which states that the production function with respect to a single input must be non-negative for an efficient production function is expressed as:

The condition expressed in EquationEquation (2.7)(2.7)

(2.7) depicts that the marginal product of each factor input must be equal to its price. Thus, the value addition to the product must be equal to the price of the factor input.

In the long run production, both the first-order condition and the second-order condition must be satisfied for an efficient production where the second-order condition states that the second derivative of the production function with respect to a single input must be non-positive such that:

Therefore, in order for a rational producer to maximize profit, the condition is that the additional revenue derived from increasing production by a unit of input should equal the amount incurred on the input variable to increase production. This implies that a rational producer will not increase production if the cost of such increment is more than its corresponding gain. This theory seeks to guide the producer in making rational decision on the volumes of output it produces. From the context of the study, it is assumed that the smallholder farmers are rational and therefore will seek to maximise their profits through efficient utilization of the input variables available to them (Tocco et al., Citation2013; Miller, Citation2006). Therefore, to maximize their profits, the farmers need to increase their gross margins, net margins and return on investment by either reducing their overall cost of production or increasing output efficiently. When the inputs are utilized efficiently, the farmer is likely to increase his or her gross margin, net margin and return on investment.

2.2. Empirical review

Literature on the effect of outgrower schemes on profitability (gross margin, net margin and return on investment) is scanty but available literature focuses on the effect of outgrower schemes on incomes among smallholder farmers creating a gap in literature (Schüpbach, Citation2014; Bolwig et al., Citation2009; Bellemare, Citation2012; Wendimu et al., Citation2016). The researchers tend to focus on the effect of outgrower schemes on incomes of farmers without dealing with the specific issues that determine income generation such as profitability.

Schüpbach (Citation2014) reports a positive effect of participation in the sugar industry on farm income and (long-term) household wealth. Controlling for a range of factors and taking into account possible non-random selection through the use of the Propensity Score Matching (PMS) technique, Schüpbach (Citation2014) found a significant and sizeable positive effect of participation for both sugar cane outgrower schemes and employment on large-scale sugar estates on farms. In addition, results from propensity matching suggest an increase in the magnitude of 2.9–3.9 index points compared to (similar) small-scale farmers unconnected to the sugar industry (Schüpbach, Citation2014).

Also, Bolwig et al. (Citation2009) in a study on the economics of smallholder organic contract farming in Tropical Africa, found a positive individual effect for participation on net revenues of smallholder farmers. Scheme participation for example, was associated with a 75% increase in net coffee revenue. They attributed the positive effect on net revenues to the incentives given under the schemes and the training given on the processing of coffee (Bolwig et al., Citation2009). Bolwig et al. (Citation2009) employed the OLS regression model and a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation in assessing the effect of smallholder organic contract farming on net revenue among others.

Moreover, Bellemare (Citation2012) in assessing the welfare impacts of contract farming, found a positive effect on household income. Bellemare (Citation2012) employed the contingent-valuation experiment to control for unobserved heterogeneity among smallholders in estimating the impacts of contract farming on household income among others. Schüpbach (Citation2014), Bolwig et al. (Citation2009) and Bellemare (Citation2012) have all reported a positive effect of outgrower schemes on farm incomes using various approaches including the PSM and OLS regression model and FIML estimation. The net positive effect on farm incomes imply that farmers who participate in outgrower schemes experience increment in incomes.

However, Wendimu et al. (Citation2016) on the other hand in assessing the Sugarcane Outgrower Scheme found that participation in outgrower schemes has a huge negative effect on the income of outgrowers. This was due to the fact that farmers already had access to the most limiting resource in producing the sugarcane before the establishment of the contract scheme which did not really offer new technologies. Wendimu et al. (Citation2016) in assessing the sugarcane outgrower scheme employed the PSM to analyze the effects of compulsory participation in the sugarcane outgrower scheme as used by Schüpbach (Citation2014).

Abdulai and Al-hassan (Citation2016) also assessed the effects of contract farming on smallholder soybean farmers’ incomes in the Eastern corridor of the Northern Region of Ghana. Estimation of the effect of contract farming on income shows that participation in contract farming does not necessarily improve smallholder farmers’ income. The study also revealed that the factors positively influencing farmers’ participation in contract farming were; access to ready market, credit and extension service. The treatment effects model was used for the analysis. A sample size of 340 soybean farmers (contract and noncontract) was used in the study. The findings is similar to that of Wendimu et al. (Citation2016). This shows clearly that not all contract farming schemes or outgrower schemes improves the incomes of participants.

The review of literature on the effect of outgrower schemes on farm incomes of participants so far reveals that, outgrower schemes have both positive and negative effects on farm incomes of smallholder farmers participating in them. The point left unaddressed is the cost of participation which leads to profitability. Profitability in farm business goes beyond farm incomes to include profit and loss analysis for which existing literature have not fully addressed. Higher incomes may not necessarily be translated into profitability. It is therefore prudent to address the very issues that affect profitability of farmers for which the current study seeks to address.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection

Data for the study was obtained from smallholder farmers which constitute outgrowers and non-outgrowers. The population for the smallholder farmers constituted all smallholder farmers under selected nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes in selected districts in Northern Ghana and all smallholder farmers (who were non-outgrowers) in the selected districts where nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes operate.

A multistage sampling technique was used to sample the smallholder farmers. The first stage involved the selection of the districts in the region. Three districts were selected from a list of districts where the outgrower schemes operate using the simple random sampling technique. The selected districts were; Gushiegu, Karaga and East Manprusi districts.

The second stage involved the selection of the nucleus farmers. Two nucleus farmers each were purposively selected from each of the selected three districts. The nucleus farmers were purposively selected to include nucleus farmers who were supporting smallholder maize farmers as well as those who were active in operation. The six nucleus farms where the outgrowers were selected from included; Alabani farms (Alabani Ibrahim) and Kharma Farms (Adam Issahaku) from Karaga; Dokorogu farms (Abukari Dokorogu) and Mr Baba farms (Al-Hassan Mumuni Baba) from Gushiegu and Ben Awuni farms (Ben Awuni) and Sulemana Ibrahim farms (Sulemana Ibrahim) from East Mamprusi districts respectively.

The final stage involved the selection of smallholder farmers. The smallholder farmers under each district were stratified into two groups. That is, participants (outgrowers) and non-participants (non-outgrowers) where samples were taken from each stratum. The total sample size for the study was 330 made up of 150 outgrowers and 180 non-outgrowers. The number of non-outgrowers was more than the outgrowers in order to use the propensity score matching technique in estimating the effect of the schemes on smallholder farmers’ profitability since the matching is done such that all members in the outgrower group must find their respective matches in the non-outgrower group. This demands that the control group (non-outgrowers) should be more than the treatment group (outgrowers) for the matching to be done accurately without bias. Also, the non-outgrowers in the study area were more than the outgrowers which necessitated the higher sample size for the non-outgrowers.

Under each nucleus farm, a total of 25 outgrowers were selected. A total of 50 outgrowers were selected from each district making a grand total of 150 outgrowers for the study. The full list of outgrowers was not available from their nucleus farmers and so outgrowers were selected from the communities with the assistance of the nucleus farmers or their agents. Upon visiting a community, enumerators were dispersed to cover the entire community where samples were taken from every part in the community.

For the other non-outgrowers, 60 each of smallholder farmers respectively were selected from each district. The list of non-outgrowers was not available at the time of visit. A total of 30 farmers each were selected from each community where the selected nucleus farmer operates and was done in the same manner as was done in the selection of the outgrowers. A grand total of 180 non-outgrowers were selected from the three districts.

3.2. Methods of analysis

3.2.1. Factors influencing participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes

Some socio-economic characteristics of farmers may influence the decision of smallholder farmers to participate or not to participate in outgrower schemes. The Binary Logit Regression Model was therefore used to identify the factors (socio-economic characteristics of farmers) that significantly influence participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes among smallholder farmers. The logit model is specified as follows:

Where;

Pi is the probability that a farmer (i) will participate in an outgrower scheme

β₀ = constant term

βj = coefficient of explanatory variable Xj, (where j = 1, 2, … 13)

Xj = Regressors variables

εi = error term

The variables used in the logit model are further specified and described on Table .

Table 1. Description of variables used in the binary logit regression model

The coefficients of the explanatory variables from the logit regression model show the likelihood or probability or odds of change in dependent variables versus independent variables. A positive sign shows a likelihood of participation whilst a negative sign shows a likelihood of non-participation.

Gender has a negative expected sign because men are more resourceful than women and may not be much interested in outgrower schemes but women are the less privileged and are likely to be interested in such schemes for support. Age has a positive expected sign because older farmers are likely to have more responsibilities and so are more likely to join the schemes for support. The district has both negative and positive signs because it is any district may have peculiar factors influencing their participation. The rest of the variables have positive expected signs because it is revealed from literature that marriage, higher level of educational, more years of farming experience, larger farm size, larger household size, membership to an FBO and extension contact will positively influence farmers’ participation in outgrower schemes (Njiru et al., Citation2013; Sambuo, Citation2014; Sharma, Citation2008).

Since the coefficients of the explanatory variables from the logit regression results do not explain the effect of a unit change in an explanatory variable on the dependent variable, the marginal effects are computed to measure the effect of a unit change of an explanatory variable on the dependent variable. The marginal effect is estimated as follows:

Where: i = number as in 1, 2 … n, Pi = mean of the regressand variable, Xi = Regressors variables and βi = Coefficients of regression

The marginal effects measure the effect of a unit change in an explanatory variable on the dependent variable. That is, the effects on the likelihood of participation due to a unit change in an explanatory variable such as an increase in age.

3.2.2. Profitability among smallholder farmers

The objective of every farm business is to maximize profit or minimize cost. The farmer in making decisions on the utilization of farm inputs takes into consideration the combination of inputs at minimum cost that will yield the maximum amount of output as captured in the theoretical review. Profit maximization point in production is where the marginal revenue is equal to the marginal cost which can be estimated using profitability indicators such as gross margin, net profit and return on investment. All the profit indicators outlined are estimated taking into accounts the cost and returns from a production process. As captured in the theoretical review, profit which is measured in this case as gross margin, net margin and return on investment is maximized when the input resources used by farmers are efficiently utilize such that minimum inputs could yield the possible maximum yield. Therefore farmers who have access to these inputs and utilizes them efficiently are likely to increase their gross margins, net margins and return on investment.

The profitability indicators that were used in the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to estimate the effect of the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes includes; gross margin, net margin and return on investment. They were calculated per hectare of maize farm.

3.2.2.1. Gross margin

The total revenue component comprised all revenue generated from a hectare of maize farm cultivated. It was calculated by taking into consideration the total output of maize obtained from a hectare of maize farm cultivated whether sold, consumed or given out as gift. The total quantity of maize harvested was multiplied by the average price at which they sold the maize per kg to obtain the total revenue.

For the total cost of production, all the variable cost incurred in cultivating a hectare of maize farm was taken into consideration. They included; input cost, labour cost, marketing cost and mechanized services cost. The quantities and prices of these variables used in the 2016 cropping year was obtained from respondents and subsequently used for the estimations.

3.2.2.2. Net margin

Depreciation of fixed assets was calculated using the straight line method.

3.2.2.3. Assumptions underlining the depreciation of assets

The following assumptions were made in calculating the depreciation values of the various assets identified;

The straight line method of calculating depreciation was used in calculating the depreciation value for each asset. Therefore, the value of the various assets were divided by their respective lifespan to obtain the value of depreciation for each asset category. The lifespan of each asset was determine by taking into consideration how long the asset will be used by the farmer if it is used on the maize farm only at their current production levels. This was done together with each farmer. The assets that were depreciated have not salvage value hence, the salvage value for each the assets were not considered.

The value of the assets were taken based on the price at which the farmer bought the asset and was triangulated with the prevailing market prices of each asset. The assets that were depreciated include hoes, cutlasses and knapsack sprayers. These were the main asset used by farmers in cultivating maize. Tractor was not included because none of the smallholder farmers owned one. The lifespan of these assets ranges between three to six years.

3.2.2.4. Return on investment

The net margin is the value estimated from Equation (4). The total investment for this analysis is the same as the total cost of production estimated for the gross margin analysis.

3.2.3. The Propensity Score Matching (PSM) model

The PSM model was used to estimate the effect of outgrower schemes on profitability. PSM is a statistical matching technique that attempts to estimate the effect of a treatment, or other intervention such as the outgrower schemes by accounting for the covariates that predict receiving the treatment. PSM attempts to reduce the bias due to confounding variables that could be found in an estimate of the treatment effect obtained from simply comparing outcomes among units that received the treatment versus those that did not.

The possibility of bias arises because a difference in the treatment outcome (such as the average treatment effect) between treated and untreated groups may be caused by a factor that predicts treatment rather than the treatment itself. In randomized experiments, the randomization enables unbiased estimation of treatment effects; for each covariate, randomization implies that treatment-groups will be balanced on average, by the law of large numbers. Unfortunately, for observational studies, the assignment of treatments to research subjects is typically not random. Matching attempts to reduce the treatment assignment bias, and mimic randomization, by creating a sample of units that received the treatment that is comparable on all observed covariates to a sample of units that did not receive the treatment. These made the use of the PSM most suitable for the study which estimates the effect of a treatment or the scheme on profitability of farmers. Propensity score methods (matching or weighting) was needed to control for confounding effects.

In order to estimate for the effect of the outgrower schemes on profitability, three average treatments effects are estimated which are specified as follows (Abdulai et al., Citation2018):

The Average Treatment effect on the Treated (ATT) is expressed as:

The average treatment effect on the treated measures the effect of the intervention on the participants. It measures the amount of incremental value in gross margin, net margin or return on investment that participants of the schemes (outgrowers) are able to make as a result of participation in the schemes. It could be negative or positive. A positive ATT shows that the schemes have positive effect on the profitability of participants and vice versa.

Another parameter estimated is the Average Treatment Effect (ATE), which is defined as:

The average treatment effect is the overall effect on the selected variables of both participants and non-participant. It is the mean effect of the outgrower scheme on an individual who participates. It measures the general effect of the scheme on participation. Thus, the amount of incremental value smallholder farmers will make when they participate in the scheme. It could be positive or negative. A positive ATE implies that any smallholder farmer who participates in the schemes will see an increment in his profitability and vice versa.

Finally, the Average Treatment effect for Untreated Individuals (ATU) which is expressed as:

The average treatment effect for untreated individuals measures the effect the intervention would have had on the non-participants if they had participated given their current circumstances (Caliendo & Kopeinig, Citation2005). It measures the incremental value of the profitability indicators that non-outgrowers would have made if they had participated. It is also referred to as the opportunity cost of non-participation. It could be positive or negative. A positive ATU implies that non-outgrowers would have made more gains in terms of their profitability if they had participated whiles a negative ATU implies that outgrowers would have been worse off if they had participated in the outgrower schemes.

In summary, the ATT measures the effect of the schemes on participants, ATT measures the overall effect of the scheme on both participants and non-participants whiles the ATU measure the effect of the scheme on the non-participants.

3.2.3.1. Model choice

The Binary Logit Regression Model is used to estimate the propensity scores by estimating the probability of participation in outgrower schemes versus the probability of non-participation.

3.2.3.2. Choice of variables

The outcome variables were gross margin, net margin and return on investment. The other variables for the logit regression model were gender, marital status, age, level of education and farming experience

3.2.3.3. Choosing a matching algorithm

The next step after estimating the propensity scores is to select a matching technique where outgrowers are matched to non-outgrowers with propensity score values based on the chosen variable used in estimating the propensity score values. The Nearest Neighbour Matching algorithm was used in matching the propensity scores of the outgrowers as against the non-outgrowers. The Nearest Neighbour Matching algorithm randomly orders the treatment (outgrowers) and the control (non-outgrowers) and then selects treatments and finds the control group with the closest propensity (Wainaina et al., Citation2012). The individual from the outgrower group was chosen as a matching partner for a non-outgrower individual that is closest in terms of propensity score using the STATA software. When the propensity scores for both groups are similar, the near neighbour matching method often generates good pairs (Larpar et al., Citation2011). The matching is done with replacement to ensure that there is strong matching especially in situations where there is limited overlap in the distribution of scores.

Results from the PSM particularly with the estimations of the ATT, ATU and ATE were used in determining the effect of the outgrower schemes on the selected profitability indicators (gross margin, net margin and return on investment) of smallholder farmers. The ATE for example, gives the overall effect of the outgrower schemes and that a positive ATE will imply that the outgrower schemes have positive effect on the profitability of farmers with regards to participation whilst a negative ATE implies a negative effect.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Social and demographic characteristics of farmers

It is observed from Table that majority of smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana were males representing 77.3%. For the outgrowers, male represent 68.7% and for the non-outgrowers, they represent 84.4%. Even though female smallholder farmers were in the minority; those who participated in the outgrower schemes were higher than the non-participants. It could be inferred that smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana are dominated my males. This could be attributed to the fact that women in Northern Ghana perform other domestic and economic roles like housekeeping and marketing of agricultural produce in society and may not have equal time for farming like their male counterparts. This finding corroborates those of current studies such as Awunyo-Vitor et al. (Citation2016) and earlier studies such as Amankwah (Citation1996) that suggest that farming in Ghana is male dominated. This result also conforms to the assertion made by Schneider and Gugerty (Citation2010) and World Bank (Citation2014) that outgrower schemes in Ghana are male dominated.

Table 2. Social and demographic characteristics of farmers

Smallholder farmers in Ghana generally have low level of formal education. From the survey, it was observed that majority of the smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana had no formal education representing 82.4%. For those who had formal education, majority had only basic primary education representing 12.1%. However, outgrowers had more primary education (16% respondents) than non-outgrowers (8.8% respondents). For Junior High School (JHS), Senior High/Technical (SHS) School and Tertiary Levels, only few farmers attained those levels which were almost the same for both groups.

It was also observed that the main occupation for outgrowers and non-outgrowers was farming representing 96% and 95.6% of respondents respectively. This implies that the farmers rely on their farming activities for income generation and will endeavour to explore all avenues to improve upon their farming businesses. The other occupations farmers engaged in were mostly trading in animals and other food commodities and serving as tractor operators or labourers on other farms.

For membership of a Farmer Based Organization, (FBO), most farmers in Northern Ghana do not belong to any FBO. However, the proportions of outgrowers who belonged to FBOs other than the nucleus farmer outgrower scheme were higher (44.7%) than that of the non-outgrowers (11.1%). This implies that outgrowers were more interested in joining groups and associations that promote their wellbeing. Most of the FBOs farmers belong to were into welfare issues and mobilizing themselves for support that may come from government or NGOs. Most of these FBOs were formed by NGOs for various projects. They usually become dormant whenever the projects end.

With regards to extension contact, majority of outgrowers had extension contact (93.3%) which was far more than that of the non-outgrowers (45.6%). This is because the nucleus farmers with support from NGOs and other governmental bodies assist outgrowers with extension services which are often not available to the non-outgrowers. The extension services were usually on good agronomic practices and the adoption of new farming technologies.

There is no significant difference in age, farming experience, household size and available labour force between outgrowers and non-outgrowers (Table ). The average ages of the respondents were 40.1 and 39.7 years respectively for outgrowers and non-outgrowers. Smallholder farmers in the study area have relatively much experience in farming. Both groups had an average of 14 years’ experience in the farming. This implies that the farmers were familiar with what they cultivate which is expected to impact positively on their productivity. This finding conforms to that of Awunyo-Vitor et al. (Citation2016) who reported a mean farming experience of 14.07.

Table 3. Other social and demographic characteristics of farmers

The average household size for both outgrowers and non-outgrowers was 13 whilst their available labour force was 10.5 and 10.1 respectively. Outgrowers had slightly higher labour force than non-outgrowers. The farmers use family labour for most of their farm activities including sowing, weeding, fertilizer and agrochemical application, harvesting and on-farm and off-farm transportation of inputs and produce. It was observed from the field that hired labour was often employed by farmers on contract basis mostly for agrochemical application and weeding to supplement the family labour force.

4.2. Factors Influencing the decision of smallholder farmers to participate in a nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme

The results from the logit regression model is used to identify the factors that significantly influence participation in outgrower schemes and their corresponding marginal effects used in explaining the effect of a percentage change in an explanatory variable on participation.

Results from the binary logit regression model are presented in Table . The Pseudo R squared value measure how well variables of the model explain participation in scheme. Therefore the Pseudo R squared value of 0.6389 connotes that the explanatory variables well explained over 60% of the factors influencing the decision of farmers to participate in the outgrower schemes.

Table 4. Binary logit regression model results for factors influencing the decision of smallholder farmers to participate in nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme

It is observed from Table that only gender, marital status, farm size, membership of an FBO and previous extension contact significantly influenced the decision of a farmer to participate in a nucleus farmer outgrower scheme. This implies that the stakeholders involved in designing these schemes will have to take into consideration some socio-economic characteristics of farmers in order to enhance participation.

For gender, it is observed from Table that female farmers were more likely to participate in the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes. A female farmer is 35.5% more likely to be an outgrower than a male farmer. This may be due to the fact that female farmers do not have access to productive resources compared to their male counterparts and hence will take advantage of the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme to enable them have access to them.

In the case of marital status, it had a negative influence on participation which implies that farmers who are not married are more likely to participate in the nucleus farmer outgrower schemes than those who are married. A marginal effect of −0.3808 implies that the probability of a married person participating in the outgrower schemes is decreased by 38.08% and vice versa. It is assumed that married people have their wives and children supporting them in their farming activities both labour wise and financial and hence may not need to participate in the outgrower schemes for any assistance.

Farm size has a positive influence on participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes. This implies that as farmers increase their cultivated land size, they are more likely to be influenced into participating in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme. If for instance, farm size is increased by 1 hectare, the probability of a farmer participating in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme will increase by 7.31% as captured by its marginal effect. This may be due to the fact that as the farm increases, farmers will need more resources in order to cover the resultant cost increment and hence would want to participate to benefit from the credit scheme given by the nucleus farmers.

Also, membership of an FBO and extension contact both have positive influence on participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes. Farmers who belong to FBOs other than the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme are more likely to be influenced into participating in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme than non-members. Again, farmers with previous extension contact are also more likely to participate in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme. This may be due to the fact that extension contact could be a motivation factor for farmers to participate in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme. The results from the logit regression model conform to some of the findings made by Sharma (Citation2008), Sambuo (Citation2014) and Njiru et al. (Citation2013) where they identified factors such as farm size, membership of an FBO, extension contact among others to be influencing participation in outgrower contract schemes.

4.3. Effect of nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on profitability

This section of the study presents the results and discussions on the effect of the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on profitability of smallholder farmers. In estimating the effect, the propensity score matching technique was used which involved the use of logistic regression model to identify the propensity scores, after which matching analysis was done using the propensity scores followed by identifying the treatment effect on the outcome variables being gross margin, net margin and return on investment. The profitability indicators being gross margin, net margin and return on investment were estimated on per hectare of maize crop.

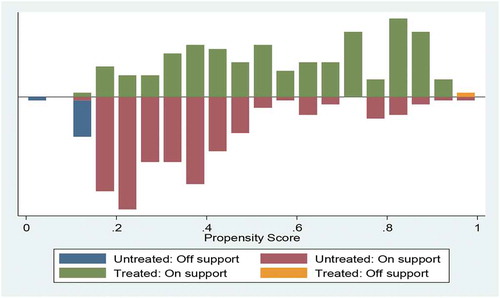

The matching algorithms for all the profitability indicators were the same. The Chi2 before matching (0.004) is significant implying that there was significant difference in the observable characteristics before matching whereas after matching (0.53) implies there are no longer statistically significant. From Table , the mean biases have also reduced (from 15.8 to 8.3) after matching.

Table 5. Covariates balance indicators before and after matching on profitability

Table 6. PSM results for the effect of nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on profitability

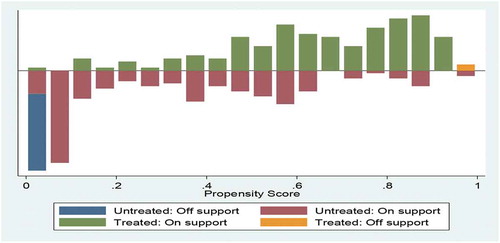

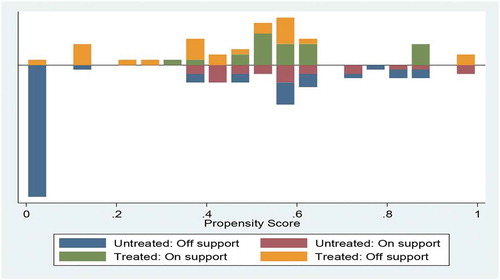

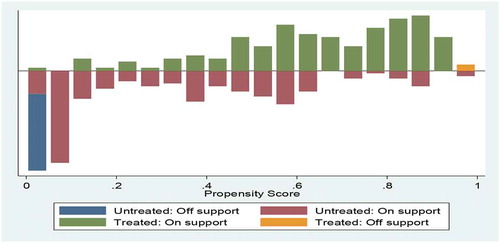

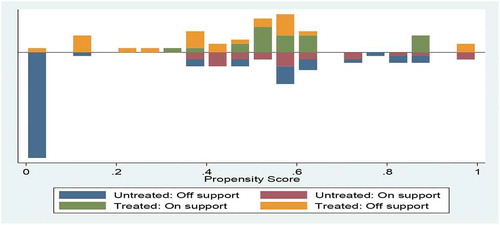

Also the graphs showing the overlap of the treatment and control groups have been presented at the Appendix A. It is observed from the graphs that the covariates of all the three parameters of profitability have passed the balancing tests.

The effect of nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on gross margin, net margin and return on investment were estimated using the near neighbour matching method. ATT of GHC 90.98 represents the effect of the participation in the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on gross margin. Therefore, the gross margin outgrowers’ make per hectare as a result of participation in the scheme is GHC 90.98. Non-outgrowers on the other hand would have made an extra of GHC 81.11 if they had participated. This represents the opportunity cost of non-participation to the non-outgrowers. ATE of GHC 85.56 represents the overall average treatment effect which implies that the general effect of an individual participating in the scheme will be GHC 85.45 in terms of increment in the gross margin. All the estimates are significant.

For the effect on net margin, an ATT of GHC 89.50 represents the gain outgrowers’ make as a result of participating in the scheme whereas an ATU of GHC 79.37 represents the amount of net margin forgone by non-outgrowers for non-participation in the scheme. The overall average treatment effect is GHC 83.94 implying that the effect of participating in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme on net margin is positive and significant.

Also with respect to the effect of the scheme on return on investment, an ATE of 0.040 which is significant suggests a positive effect on return on investment for farmers who participate in the outgrower schemes. This implies that a smallholder farmer who participates in the nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme is likely to increase his return on investment by 0.04. The ATT is also positive and significant whist the ATU is positive but not significant. This implies that the opportunity cost for non-participation is not significant Table .

The results of the effect of the schemes on profitability (gross margin, net margin and return on investment) are positive and statistically significant except for the ATU of the return on investment which is not significant. This suggests that smallholder farmer’ participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower scheme can lead to an improvement in the profitability of farmers such as an increment in their gross margin, net margin and return on investment. These results corroborate the findings of Schüpbach (Citation2014), Wainaina et al. (Citation2012), Larpar et al. (Citation2011) and Bolwig et al. (Citation2009), which indicated that outgrower schemes lead to increase in gross and margins of smallholder farmers.

This positive effect nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes had on smallholder maize farmers may be attributed to the fact that those who participated had more access to inputs, received inputs timely and as well used inputs more efficiently as found earlier in the study.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Participation in outgrower schemes is influenced by certain socioeconomic and demographic factors of farmers. The study concludes that only gender, marital status, farm size, membership of an FBO and previous extension contact significantly influence participation in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes in Northern Ghana. Females, farmers with larger farm size, farmers who belong to FBOs and farmers who had extension contact were more likely to be influenced into participating in nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes. On the effect of nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes on profitability, it is concluded that the positive difference in gross margin, net margin and return on investment between outgrowers and non-outgrowers was as a result of participation in the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes. The nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes have significant positive effect on smallholder farmer’s gross margins, net margins and returns on investment.

Therefore, nucleus famer-outgrower schemes are recommended for vulnerable smallholder farmers to participate in order to benefit from the input credit scheme so as to enhance their level of access to inputs and mechanized services. Participating in the nucleus farmer-outgrower schemes will enhance the timeliness of inputs acquired for production which has effect on productivity and efficiency.

Nucleus farmers and other stakeholders in the agricultural sector such as MOFA and NGOs should focus on providing more extension services to smallholder farmers on the efficient utilization of input resources. Outgrowers are recommended to increase their seed and agrochemical use and reduce labour whilst maintaining their fertilizer use. Non-outgrowers are recommended to increase fertilizer and labour use and reduce seed and agrochemical use so as to increase their output and profitability. Policies by government to support smallholder farmers with fertilizer to increase fertilizer use is recommended since fertilizer significantly influence yield. This will be particularly beneficial for the non-outgrowers since they currently underutilize fertilizer probably due to inadequate access.

Government, NGOs and other private individuals and organizations who work to support farmers are recommended to emulate the nucleus famer-outgrower arrangement. They are also encouraged to support and empower more nucleus farmers to be able to provide the services they give to smallholder farmers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

George Agana Akuriba

George Agana Akuriba is an agribusiness professional with great expertise in entrepreneurship, business development and planning, agricultural project evaluation, agricultural marketing and research. He holds an MPhil in Agribusiness at the University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana. Mr Akuriba lectures at the Agriculture for Social Change Department of the Regentropfen College of Applied Sciences (ReCAS), Kansoe – Ghana. His research interest is in Agribusiness and Agricultural Economics including climate change and food security issues.

References

- Abdulai, S., Zakariah, A., & Donkoh, S. A. (2018). Adoption of rice cultivation technologies and its effect on technical efficiency in Sagnarigu district of Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 4(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1424296

- Abdulai, Y., & Al-hassan, S. (2016). Effects of contract farming on small-holder soybean farmers’ income in the Eastern corridor of the Northern Region, Ghana. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 7(2), 103–113.

- Amankwah, C. Y. G. (1996). The structure and efficiency in resource use in maize production in the Asamankese district of Ghana [MPhil Dissertation]. University of Ghana.

- Awunyo-Vitor, D., Wongnaa, C. A., & Aidoo, R. (2016). Resource use efficiency among maize farmers in Ghana. Agriculture and Food Security, 5(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-016-0076-2

- Bellemare, M. F. (2012). As you sow, so shall you reap: The welfare impacts of contract farming. World Development, 40(7), 1418–1434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.008

- Bolwig, S., Gibbon, P., & Jones, S. (2009). The economics of smallholder organic contract farming in tropical Africa. World Development, 37(6), 1094–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.09.012

- Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2005). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching (Discussion Paper IZA DP Germany).

- Felgenhauer, K., & Wolter, D. (2009). Outgrower schemes – Why big multinationals link up with African smallholders. Policy Analysis and Advocacy Programme (PAAP), Electronic Newsletter, OECD.

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2015). Ghana poverty mapping report.

- Hussain, A., & Thapa, G. B. (2016). Fungibility of smallholder agricultural credit: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. The European Journal of Development Research, 28(5), 826–846. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2015.55

- Larpar, M. L., Toan, N. N., Zou, J., Li, X., & Randolph, T. (2011). An impact evaluation of technology adoption by smallholders in Sichuan, China: The case of sweet potato-pig system [ Paper presented]. 55th annual AARES national conference, Melbourne, Victoria.

- Miller, N. (2006). Notes on microeconomic theory (August, 2006 version).

- Njiru, N., Muluvi, A., Owuor, G., & Langat, J. (2013). Effects of khat production on rural household’s income in Gachoka division Mbeere South district Kenya. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 4(2).

- Njogu, G. K., Njeru, A., & Olweny, T. (2017). Influence of technology adoption on credit access among small holder farmers: A double-hurdle analysis. Africa International Journal of Management Education and Governance (AIJMEG), 2(3), 60–72.

- Ntsiful, A. K. (2010). Outgrower oil palm plantations scheme private companies and poverty reduction in Ghana [A dissertation Presented to St Clements University, in Turks and Caicos Islands in Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy].

- Oya, C. (2012). Contract farming in sub‐Saharan Africa: A survey of approaches, debates and issues. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00337.x

- Paglietti, L., & Sabrie, R. (2012). Ghana outgrower schemes: Advantages of different business models for sustainable crop intensification. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- Ragasa, C., Lambrecht, I., & Kufoalor, D. S., (2017). Limitations of contract farming as a pro-poor strategy the case of maize outgrower schemes in Upper West Ghana (IFPRI Discussion Paper). Development Strategy and Governance Division.

- Rudy, V. G. (2010). Outgrower best practices, field reporting, appraisal and monitoring, and notes on commercial and social dimensions of outgrower arrangement. Competitive African Cotton Initiative, Lusaka.

- Sambuo, D. (2014). Tobacco contract farming participation and income in Urambo; Heckma’s selection model. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(28), 230–237.

- Schneider, K., & Gugerty, M. K. (2010). Gender and contract farming in sub-Saharan Africa–Literature review. Evans School of Public Affairs, University of Washington.

- Schüpbach, J. M. (2014). The impact of outgrower schemes and large-scale farm employment on economic well-being in Zambia [Doctorate Dissertation]. University of Zurich.

- Sharma, V. P. (2008). India’s agrarian crisis and corporate-led contract farming: Socio-economic implications for smallholder producers. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 11(4), 25–48.

- Sivramkrishna, S., & Jyotishi, A. (2008). Monopsonistic exploitation in contract farming: Articulating a strategy for grower cooperation. Journal of International Development, 20(3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1411

- Tocco, B., Bailey, A., & Davidova, S. (2013). The theoretical framework and methodology to estimate the farm labour and other factor-derived demand and output supply systems (Working Paper). Factor Markets.

- Wainaina, P. W., Okello, J., & Nzuma, J. (2012). Impact of contract Farming on smallholder poultry farmers’ income in Kenya [ Paper presented]. Presentation at the international association of agricultural economists (IAAE) triennial conference, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Wendimu, M. A., Henningsen, A., & Gibbon, P. (2016). Sugarcane outgrowers in Ethiopia: “Forced” to remain poor. World Development, 83, 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.002

- World Bank. (2014). The practice of responsible investment principles in large-scale agricultural investments: Implications for corporate performance and impact on local communities (Agriculture and Environmental Services Discussion Paper 08. World Bank Report Number 86175-GLB).

- World Bank. (2015). World Development Indicators; World Economic Outlook; Global Economic Prospects; Economist Intelligence Unit.

Appendix A.

Before and after matching qualities for gross margin, net margin and return on investment.