Abstract

In the south-west of Ethiopia, enset plant has a major role to play in food security and the ability to drought-resistant and multi-purpose in modern lifestyles. The use of traditional fermented kocho has been increased in south Ethiopia as consumers want a healthy dietary food. The microbiology of kocho fermentation ensures the desirable quality of kocho. Existing papers have been organized and reviewed on the dynamics of growth, survival, and biochemical activity of microbes and their importance in the traditional fermentation process of kocho. The quality of kocho depends on the enset processing, fermentation methods, and periods. Few studies have been published on the importance of microorganisms during the kocho fermentation process. In kocho fermentation, LAB is used for the production of metabolites such as acetic acid, propanoic acid, butanoic acid, pentanoic acid, and hexanoic acid. Some of the species of Lactic acid bacteria in kocho fermentation that impart desired protein content, flavor, odor, and degrading anti-nutritional factor. However, there are limitations of studies on the role of microorganisms in kocho fermentation process. In conclusion, some of species of the microorganisms during kocho fermentation are identified and isolated for the purpose of quality, and safety of kocho, but other suitable microorganisms are not well studied in previous researchers. Thus, further investigations may also be needed on the microbiology of kocho fermentation in order to enhance the nutritional quality, sensory properties, and safety of the kocho product.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Enset is indigenous raw materials and used as the staple food. The major populations of Ethiopia are used enset as food options in the case of food security. Enset contains substantial carbohydrate content and other trace minerals. In the fermentation process, the enset is converted by microbes such as Lactic acid bacteria, yeast, and moulds to kocho product. In kocho fermentation, desirable microorganism provides metabolites compound, which imparted the desired flavor, and odor of kocho. Microbial dynamics in traditional kocho fermentation have the main goal of supplying consumers with nutritious and safe food. In the case of kocho microbiology, identification and isolation of suitable microorganisms are restricted to a certain area of Ethiopia. This paper is intended to review the dynamics of microorganisms in kocho fermentation process and their importance for the consumption of dietary food. This paper will provide guidance on kocho microbiology for the future line of study.

1. Introduction

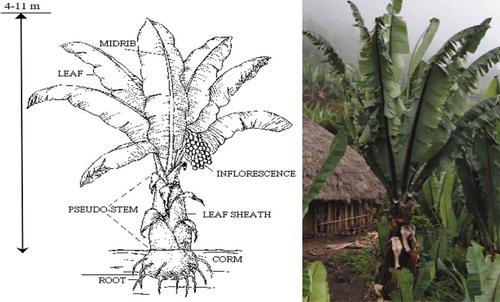

Enset (ventricosum welw Cheesman) is a perennial herbaceous root crop like-false banana. Enset plants growing at height of 4–11 m in height, drought-resistant, and cultivated in the southern and southern western Ethiopia. It is used as a staple food in case of food security in our country (Bosha et al., Citation2016; Brihanu, Citation2015; Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011; Karssa et al., Citation2014). Enset includes significant amounts of starch and other trace elements (Bosha et al., Citation2016; Karssa et al., Citation2014). However, it has a low protein content (Bosha et al., Citation2016). Over 10 million Ethiopian people’s lifestyles are focused on the processing of enset (ventricosum welw Cheesman) plants for the development of fermented kocho (Karssa et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. Role of microbial dynamics in fermented kocho

Most Ethiopians people prepare traditional fermented food from a variety of raw materials such as teff, sorghum, enset, milk, etc. Traditional fermented foods produced from these raw materials are injera, kocho, siljo, and ergo (Ashenafi, Citation2006). Kocho is one of the most popular fermented foods to be found next to injera. It contains a rich starch content of fermented food made from the pseudostem, pulverized corm, and decorticated pulp (Dibaba et al., Citation2018). (Bosha et al., Citation2016) reported that kocho is rich in carbohydrate levels. However, kocho has a low protein content (Yirmaga, Citation2013). Protein content is now a major factor in the traditional fermented kocho food. Previous study has been revealed that fermented kocho by means of the modified method of processing provides nutritional consistency compared to the traditional method of processing (Yirmaga, Citation2013). The fermentation duration of kocho varied from location to location, depending on their incubation temperature. The period of kocho fermentation is one year (Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Yirmaga, Citation2013). However, fermentation times of traditional fermented kocho take place in a pit for two to three weeks (Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Karssa et al., Citation2014). Traditional fermented kocho processing is varied from region to region based on their indigenous knowledge of people (Karssa et al., Citation2014; Tsegaye & Gizaw, Citation2015; Weldemichael et al., Citation2019). The quality of kocho depending on the variety of enset, fermentation period, and processing approaches (Yirmaga, Citation2013). According to (Karssa et al., Citation2014; Yirmaga, Citation2013) as the fermentation period of kocho raised, the quality acceptability of kocho increased. However, lack of experience, technology, infrastructure, and qualified persons have become barriers to improving the quality, safety, hygiene, and acceptability of fermented food (Holzapfel, Citation2002) and kocho (Woldemariam et al., Citation2019).

Fermentation is a process introduced by a variable microorganism that turns raw materials into the desired final product. It is used to impart the desired sensory properties (taste, flavor, texture, and overall appearance), enhance quality, safety, increase shelf-life, inhibit the growth of foodborne, and spoilage of microorganisms. Food fermentation has been used as a preservation technology for at least 6000 years. Several studies have shown that traditional fermented foods are a source of dietary or wholesomeness due to a fermentation technology used for preservation, nutritional enhancement, and sensory aspects (Holzapfel, Citation2002, Citation1997; Steinkraus, Citation1996).

(Andeta et al., Citation2018; Holzapfel, Citation2002; Odunfa & Oyewole, Citation1998) revealed that microorganisms play a significant role in the fermentation process of traditional foods, which can contribute to palatability, wholesomeness, improved nutritional quality, organoleptic characteristics, extended shelf-life, and used as food preservatives, as well as help to maximize and standardize fermentation. In Ethiopia, there are limitations to studies on the role of microbial organisms, microbial activity, and dynamics in kocho fermentation. It is not fully identified and isolated to enhance nutritional quality, organoleptic attributes, hygiene, food safety, and to prevent pathogenic microorganisms as well as standardized process, modernizing traditional fermented kocho, and scaling-up to industrial level. The literature review on the microbiology of kocho is not well performed in depth for future investigations. However, a few authors have observed the characterization, identification, and isolation of microorganisms (Andeta et al., Citation2018; Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Karssa et al., Citation2014). The main objective of this paper is to review the dynamics of microbes during the kocho fermentation process and their role in the food fermentation.

2. “Enset (Ventricosum)”

Enset (ventricosum) is an indigenous raw material capable of overcoming drought, and rising at 4–11 m (Figure ). They are also used as food options in the case of food security (Karssa et al., Citation2014). In Ethiopia, enset cultivation varied from place to place, depending on the type of plant, soil quality, environment, and altitude (Birmeta et al., Citation2019). Enset contains less protein, fat, and vitamin A content (Bosha et al., Citation2016). Enset is preferable to kocho production (Andeta et al., Citation2018). In addition, it is used for the production of bulla, and amicho, and is used as a binding material, packaging material, animal feed, fiber, and house-building materials (Karssa & Papini, Citation2018). Enset is a well-known domestically produced traditional fermented kocho (Andeta et al., Citation2018; Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Karssa et al., Citation2014; Weldemichael et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1. The enset plant (Andeta et al., Citation2018)

3. Enset processing methods

The enset processing period is carried out during the year, but can be affected by climatic conditions. Enset processing is based on their understanding of traditional people, and differs from location to location (Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011). Awareness of traditional cultures in the enset process may have an effect on the quality acceptability of the kocho product. Still, they are used traditional techniques, and equipment for kocho processing.

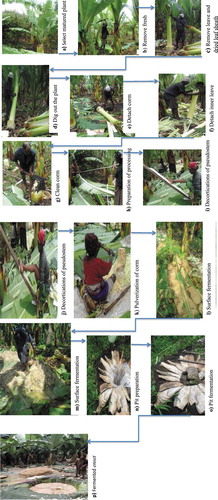

The first step in the process of kocho processing should be the collection of matured enset plants by experienced women (Figure )). An experienced woman classified matured enset plant species by degree of maturity, such as seizure of the central-folded leaf shoot called “Utute”, appearance of inflorescence “Shaha”. According to (Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011) the maturation period depends on soil fertility, amount and pattern of rainfall.

After a mature enset plant has been selected, then leaves are removed, and cleared, and dried leaf sheaths from the plant and the surrounding part of the plant for the next steps (Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011) (Figure ,c)). Dig out the plants and prepare it for further processing (Figure )). The underground corm is detached and cleaned to isolate the true stem from it (Figure ,g)). Then, the inner leaf sheaths separated from the pseudostem down to the real stem, which is a segment between the corm and the pseudostem (Figure )). The true stem is isolated from the underground corm (Yirmaga, Citation2013). Starter culture can be produced from inner corm, which plays a significant role in the initiation of the fermentation process, improves the texture and flavor of kocho product (Dibaba et al., Citation2018). After starter cultures have been prepared, and completed the fermentation process, then prepare a processing area for the decortication and pulverization process. The leaves of the harvested plants are used to line the inner part of the pit and for the processing site (Figure )).

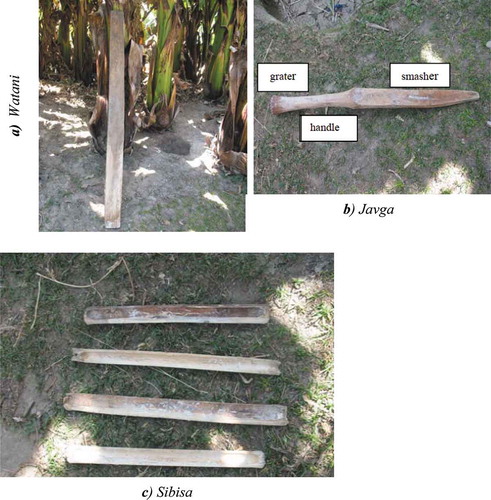

The pseudostem and corm of enset plant are decorticated and pulverized (Figure ,k)). Watani is the traditional equipment used to decorticate the pseudostem (Figure )), and Javga is used to pulverize the corm (Figure )). Sibisa is used to scrap the fleshy portion of the enset leaf sheath (Figure )). Afterward, decorticated and pulverized processing steps, fresh dough prepared for the next processing. The starter culture is chopped and then blended with the fresh dough for further processing. The fermentation method of enset is carried out in the surface fermentation (Figure )). Ingredients used as starter culture are incorporated into the open cavity of scraped corm and mixed with pulverized and decorticated enset. pseudo-stem and corm tightly coated with enset leaves, loaded with heavy material and processed for around two weeks in the processing area (Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011). Finally, the decorticated and pulverized mass of enset or pseudo-stem and corm are stored in the earthen pit (Figure )). Fermentation will take place within three months for the complete fermentation of the kocho product (Dibaba et al., Citation2018) (Figure )). Fermentation methods and times varied from location to location in our country. As a result, variation in these factors can alter the quality of fermented kocho from area to area.

Figure 2. Equipment used for enset processing (Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011)

Figure 3. Diagrammatic representation of enset processing for kocho production (Helen, Citation2019)

4. Kocho fermentation methods

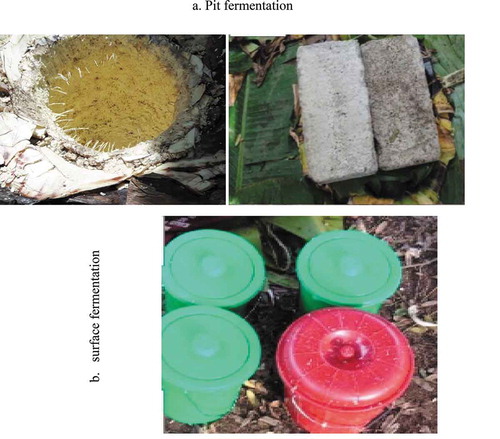

Kocho fermentation methods ranged from location to location (Weldemichael et al., Citation2019). According to (Karssa et al., Citation2014) the traditional kocho fermentation process has carried out two methods, such as surface fermentation and pit fermentation (Figure ,b)). However, traditional small-scale fermentation methods have not maintained well the nutritional quality, safety, and stability of microorganisms (Holzapfel, Citation2002). (Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011) revealed that the enset fermentation approaches performed in the earthen pit, but processing is exhausted, labor-intensive, lack of hygienic and safe, and improper equipment used. Moreover, according to (Weldemichael et al., Citation2019), traditional methods of processing needed more fermentation time, energy-consumption, hard work, and hygienic protection. Similar data reported by (Renes et al., Citation2014). (Yirmaga, Citation2013) has shown that the modified kocho fermentation method has a higher moisture content than traditional fermentation methods, but a lower protein, carbohydrate, fiber, and fat content than traditional fermentation methods. However, kocho fermentation in the pit resulted in a decrease in pH and increased titrable acidity (Karssa et al., Citation2014). Similar findings have been found (Andeta et al., Citation2018). The pH value of kocho product is influenced by the fermentation methods. Nutritional quality of kocho is based on the fermentation methods (Weldemichael et al., Citation2019; Yirmaga, Citation2013). (Weldemichael et al., Citation2019) showed that the culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches were used to characterize the microbiota and volatile compounds. Culture-dependent techniques are deficient in the quality of kocho since they regulate only a part of the microbial population (Birmeta et al., Citation2019). Culture-independent or modern methods with hygienic equipment are preferred to improve the nutritional quality of the traditional fermented kocho.

Figure 4. Kocho processing methods (Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Karssa et al., Citation2014)

5. Kocho fermentation periods

kocho fermentation periods are prolonged from 3 up to 6 months (Gashe, Citation1987), but takes place for one year (Hunduma & Ashenafi, Citation2011; Karssa et al., Citation2014). Variation between fermented, unfermented, and completely fermented kocho is inadequate fermentation period (Gashe, Citation1987). Increased fermentation periods during processing are the most desirable for the quality of kocho (Gashe, Citation1987). (Yirmaga, Citation2013) reported the increased fermentation time of the kocho giving a good texture and overall acceptability of the kocho. In addition, the quality of fermented enset dough is enhanced due to increased fermentation periods of kocho (Karssa et al., Citation2014). The majority of respondents indicated that the appropriate season for enset processing is mainly carried out during the dry season rather than the wet season due to its thickness, low water content, soft, and easy fermentation which gives desirable kocho product (Tsegaye & Gizaw, Citation2015). Processing enset in the Gamo high lands of Ethiopia depends on their traditional knowledge of people and fermentation approaches (Andeta et al., Citation2018). The length of fermentation times can influence the quality of the kocho, shelf-life, palatability, and the safety of fermented food (Yirmaga, Citation2013). (Karssa et al., Citation2014) revealed that the duration of fermentation times depends on the location, environmental temperature, and the fermentation mass of the dough.

6. Food fermentation

Fermentation is a method in food biotechnology that has been used as a preservative agent since ancient times and preserved the quality of food (Holzapfel, Citation2002). Several studies have shown that fermentation is a process of transferring the raw materials to a desirable final product due to the role of microorganism which contribute desired organoleptic attributes, extend the shelf-life of food, consume energy, enhance proximate composition, and functional attributes of food (Akalu et al., Citation2017; Blandino et al., Citation2003; Holzapfel, Citation2002; Kam et al., Citation2011). However, the fermentation process affects the nutritional quality, organoleptic property, and storage of traditional fermented food (Campbell-Platt, Citation1987; Holzapfel, Citation2002). Traditional enset fermentation has resulted in significant losses in protein, ash, and minerals due to the leaching of these nutrients through the permeable fermentation pit (Urga et al., Citation1997). However, it has merit in degrading anti-nutritional factors, inhibiting the growth of the harmful microorganisms, and retardant food-born disease.

The traditional food fermentation process can be categorized into lactic acid fermentation, fungal fermentation, and alkaline fermentation (Terefe, Citation2016). Kocho is a lactic acid fermented food in southern Ethiopia. Fermented food products provide diet food to consumers, practically utilized in developing countries (Terefe, Citation2016). In addition, fermented foods are used as nutritious and balanced food, as well as anti-cancer, anti-aging, anti-obesity, and anti-constipation.

7. Role of microbial dynamics in kocho fermentation

Microbial dynamics are the dynamics of growth, survival, and biochemical activity of microorganisms in fermented kocho and food fermentation, which provide the desired quality of fermented food as shown in table . Besides, microbial dynamics are the driving force of the traditional food fermentation. Microorganisms play a major role in the fermentation process of traditional food, which can contribute the palatability, wholesomeness, enhancing nutritional quality, and extending shelf-life (Holzapfel, Citation1997). According to (Braide et al., Citation2018) beneficial microorganism species in food fermentation are Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Streptococcus, Saccharomyces, Corynebacterium, and Leuconostoc. LAB provides metabolites compounds such as acetic acid, lactic acid, carbon dioxide, ethanol, hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, and antimicrobial peptides (Di Cagno et al., Citation2013). These metabolite compounds have a significant improvement in the flavor and odor of kocho product.

7.1. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB)

According to (Karssa et al., Citation2014) studied during kocho fermentation, all microbial counts gradually decreased in five different traditional fermented methods such as kocho fermentation in the pit, in a bucket with a starter culture, in a bucket without starter culture, with a starter culture in the pit, in a bucket without starter culture buried in pit expects the LAB in kocho fermentation buried in a pit and without starter culture in bucket buried in a pit at days 0 to 4. Maximum counts of LAB 8.9 log CFU/g and yeasts 6.4 log CFU/g are obtained during traditional fermentation of kocho with starter culture in the pit at 4th day and 2nd day (Al‐Mahasneh et al., Citation2014) due to an increase in the fermentation period of kocho and a decrease in pH (Yirmaga, Citation2013). Both are dominant microorganisms during traditional kocho fermentation in the pit. However, the highest and lowest counts of LAB are recorded log 16.11 CFU/g, log 15.11 CFU/g at 10 days to 30 days of fermentation time, respectively. Moreover, the counts of LAB in gamma fermentation increased until 30 days and declined at 60 days (Dibaba et al., Citation2018) due to the inhibitory effect of a low pH (Andeta et al., Citation2018; Gashe, Citation1987).

LAB is the most dominant and beneficial microorganism during traditional kocho fermentation and is also responsible for the production of organic acid (Karssa et al., Citation2014). (Bosha et al., Citation2016; Gashe, Citation1987) revealed that the number of lactic acid bacteria increased during the fermentation of kocho, which significantly decreased the sugar content of kocho due to increasing the fermentation periods of kocho. According to (Urga et al., Citation1997) the concentration of sugar decreased during kocho fermentation because of the metabolism of sugars which imparting lactic acid and other organic acids. Furthermore, lactic acid bacteria present during kocho fermentation contribute to the development of volatile compounds to enhance the flavor and odor of kocho product (Weldemichael et al., Citation2019). Lactic kocho fermentation useful for reducing the content of trypsin inhibitors and tannins that enhance the protein digestibility of kocho and bioavailability of minerals (Urga et al., Citation1997). Similar trends reported by (Gashe, Citation1987) fermented kocho imparted a strong butyrous odor characteristic due to the roles of Clostridium species.

The growth rate of the L. mesenteroides species rapidly increased during kocho fermentation. It is considered as the initiator of kocho fermentation (Gashe, Citation1987). Similar findings have been observed (Dibaba et al., Citation2018). LAB kocho fermentation, mainly Leuconostoc mesenteroides responsible for decreased moisture content, pH, and increased titratable acidity due to acid-producing microorganisms (Andeta et al., Citation2018). Similar findings have been observed (Dibaba et al., Citation2018; Karssa & Papini, Citation2018; Urga et al., Citation1997). In addition, L. plantarum and L. mesenteroides are degraded starch content during the long term of kocho fermentation, which imparts desirable organoleptic properties of kocho, and inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms (Birmeta et al., Citation2019). However, L. plantarum starter strain is important for the good quality of kocho at 2 days of fermentation. Sensory properties of kocho can be affected by the fermentation period, the amount of starter culture, and the starter strain (Woldemariam et al., Citation2019).

7.2. Enterobacteriaceae

Enterobacteriaceae is not detected between 12 and 15 days during fermentation kocho due to adverse condition and reduction of pH over fermentation periods (Karssa et al., Citation2014) and similar findings have been observed (Andeta et al., Citation2018; Dibaba et al., Citation2018). (Steinkraus, Citation1996) revealed that Enterobacteriaceae cannot grow between a pH of (3.5 to 4.0). Elimination of Enterobacteriaceae plays a major role in the safety of kocho and in the reduction of pathogens (Dibaba et al., Citation2018). Increased fermentation periods of kocho may also have inhibited the growth of Enterobacteriaceae microorganisms, with the exception of E.coli O157: H7. It can grow in an acidic environment.

7.3. Yeasts and mould

The highest and lowest amounts of yeasts and molds were obtained log3.98 CFU/g, log 2.60 CFU/g at 10 to 30 days fermentation periods of kocho, respectively. Decrease of these findings indicates the anaerobic condition of kocho fermentation, which leads to a reduction in pH, and a rise in titrable acidity (Yirmaga, Citation2013). Moreover, the yeasts and molds counts are decreased with increased fermentation time due to the anaerobic condition of gamma fermentation or lack of sufficient oxygen during fermentation periods (Dibaba et al., Citation2018). Similar trends have been observed (Andeta et al., Citation2018). According to (Birmeta et al., Citation2019) yeasts are not fully isolated during fermentation of kocho due to none fermenters or the absence of oxygen for growth throughout fermentation periods. This finding has been confirmed (Gashe, Citation1987). However, increase counts of yeast in kocho fermentation that degraded starch and impart anti-microbial metabolites like ethanol, and organic acids. According to (Steinkraus, Citation1996) yeasts afford vitamins and contribute factors in case of growth for the LAB. Adequate oxygen is needed for the growth of the yeast during kocho fermentation.

The role of the yeast in kocho fermentation process has not been well studied by previous researchers (Andeta et al., Citation2018). Therefore, Identification and characterization of species of yeast in kocho fermentation are important for the standardization and scale-up traditional enset fermentation process as well as improve quality, maintaining hygiene, and the safety of kocho product. However, some identified yeast species are harmful microbes to human beings like Filobasidilla neoformans, Candida, and Trichosporon. Safety and hygienic requirements are necessary during enset processing periods (Gizaw et al., Citation2016). This results in agreement with (Birmeta et al., Citation2019). Some of the species of the yeast, such as Cryptococcus albidusVar aerus, Guilliermondella selenospora, Rhodotorula acheniorum and Trichosporonbeigelii Cryptococcus terreus A, Candida zylandase, and Kluyveromycesdelphensis are isolated and identified from kocho, but are not Saccharomyces yeast. According to these findings, species of yeast can produce such as L-glutamic acid, D-gluconic acid, cellobiose, maltose, a-D-glucose, D-galactose+ D-xylose, D-glucuronicacid+ D-xyloses (Gizaw et al., Citation2016). These metabolites have the necessary organoleptic properties of kocho.

7.4. Acetic acid bacteria

The acetic acid bacteria are isolated from the LAB selective media during longer fermentation periods which can enhance the number of metabolites, sensory attributes and maintain hygiene, and wholesome of kocho fermentation (Birmeta et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Weldemichael et al., Citation2019 showed that a higher abundance of AAB is isolated due to the addition of the starter culture immediately at the beginning of the fermentation periods. Correspondingly with the explanation for this finding (Birmeta et al., Citation2019; Bosha et al., Citation2016). Provide aeration at the beginning of kocho fermentation periods a major contribution to the flavor, and odor of kocho product.

In general, the role of microbial dynamics in food fermentation showed the desired sensory attributes (flavor, texture, consistency, appearance, taste), extended shelf-life, elimination of food pathogens and spoilage, decreased cooking time, minimized energy consumption, improved nutritional quality by degrading anti-nutritional factors, and increased protein digestibility (Holzapfel, Citation1997).

8. Conclusion

Enset is the staple food in the case of food security. In the case of nutritional quality, it comprises a rich source of carbohydrate and a low protein and mineral content. The quality of the kocho can be influenced by the enset varieties, fermentation techniques, duration of fermentation times, climatic condition, enset processing equipments, and indigenous knowledge. Traditional fermented kocho varies in fermentation approaches, and periods as well as knowledge of the traditional people. The driving force of kocho fermentation process is “Microbial dynamics”. In the case of the microbiology of kocho, the action of microorganisms in the fermentation of kocho has the advantages of providing the nutritional profiles, and sensory properties of kocho. However, limited studies have been reported on the function of microorganisms in kocho fermentation. Several researchers have reported the role of Lactic acid bacteria in kocho fermentation. In addition, few studies have reported the microbial dynamics of yeast and Acetic acid bacteria in kocho fermentation, which give the flavor and odor of kocho, and anti-microbial metabolites. Moreover, some of the species of LAB are essential for the contribution of the desired flavor, and odor of kocho product. Thus, further investigations may also be needed on the microbiology of kocho fermentation with a view to enhance the nutritional quality, sensory properties, extending the shelf-life, maintaining safety and hygienic of kocho. In addition, more studies are needed to modernize the methods of kocho fermentation and equipment used in traditional kocho fermentation. The hygienic and safety requirements for enset processing are relevant for the contribution of wholesomeness and palatability of the kocho product.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kenenisa Dekeba Tafa

Kenenisa Dekeba Tafa is a Lecturer in the Department of Food Processing Engineering, College of Engineering and Technology, Wolkite University, Ethiopia. His research area includes Food Rheology, New Product Development, and Food Quality and Safety.

Worku Abera Asfaw

Worku Abera Asfaw is a Lecturer in the Department of Food Processing Engineering, College of Engineering and Technology, Wolkite University, Ethiopia. He is working in the area of New Product Development, Food Quality and Safety, and Extraction Technology.

References

- Akalu, N., Assefa, F., & Dessalegn, A. (2017). In vitro evaluation of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional fermented shamita and kocho for their desirable characteristics as probiotics. African Journal of Biotechnology, 16(12), 594–12. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2016.15307

- Al‐Mahasneh, M. A., Rababah, T. M., Amer, M., & Al‐Omoush, M. (2014). Modeling physical and rheological behavior of minimally processed wild flowers honey. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 38(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4549.2012.00734.x

- Andeta, A., Vandeweyer, D., Woldesenbet, F., Eshetu, F., Hailemicael, A., Woldeyes, F., Crauwels, S., Lievens, B., Ceusters, J., & Vancampenhout, K. (2018). Fermentation of enset (Ensete ventricosum) in the Gamo highlands of Ethiopia: Physicochemical and microbial community dynamics. Food Microbiology, 73, 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2018.02.011

- Ashenafi, M. (2006). A review on the microbiology of indigenous fermented foods and beverages of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Biological Sciences, 5, 189–245.

- Birmeta, G., Bakeeva, A., & Passoth, V. (2019). Yeasts and bacteria associated with kocho, an Ethiopian fermented food produced from enset (Ensete ventricosum). Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 112(4), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-018-1192-8

- Blandino, A., Al-Aseeri, M., Pandiella, S., Cantero, D., & Webb, C. (2003). Cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Research International, 36(6), 527–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00009-7

- Bosha, A., Dalbato, A. L., Tana, T., Mohammed, W., Tesfaye, B., & Karlsson, L. M. (2016). Nutritional and chemical properties of fermented food of wild and cultivated genotypes of enset (Ensete ventricosum). Food Research International, 89, 806–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2016.10.016

- Braide, W., Azuwike, C., & Adeleye, S. (2018). The role of microorganisms in the production of some indigenous fermented foods in Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Research and Biological Science, 5(5), 86–94 http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2018.05.05.011

- Brihanu, Z. T. (2015). Community indigenous knowledge on traditional fermented enset product preparation and utilization practice in Gedeo zone. JBES, 5(3)

- Campbell-Platt, G. (1987). Fermented foods of the world. A dictionary and guide. Butterworths.

- Di Cagno, R., Coda, R., De Angelis, M., & Gobbetti, M. (2013). Exploitation of vegetables and fruits through lactic acid fermentation. Food Microbiology, 33(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2012.09.003

- Dibaba, A. H., Tuffa, A. C., Gebremedhin, E. Z., Nugus, G. G., & Gebresenbet, G. (2018). Microbiota and physicochemical analysis on traditional kocho fermentation enhancer to reduce losses (Gammaa) in the highlands of Ethiopia. Microbiology and Biotechnology Letters, 46(3), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.4014/mbl.1801.01010

- Gashe, B. A. (1987). Kocho fermentation. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 62(6), 473–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1987.tb02679.x

- Gizaw, B., Tsegay, Z., & Tilahun, B. (2016). Isolation and characterization of yeast species from ensete ventricosum product; Kocho and bulla collected from Angacha district. International Journal of Advanced Biological and Biomedical Research (IJABBR), 4, 246–252.

- Helen, W. (2019). Development of starter culture for kocho, a traditional fermented food of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University.

- Holzapfel, W. (1997). Use of starter cultures in fermentation on a household scale. Food Control, 8(5–6), 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-7135(97)00017-0

- Holzapfel, W. (2002). Appropriate starter culture technologies for small-scale fermentation in developing countries. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 75(3), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00707-3

- Hunduma, T., & Ashenafi, M. (2011). Traditional enset (Ensete ventricosum) processing techniques in some parts of West Shewa zone, Ethiopia

- Kam, W., Aida, W., Sahilah, A., & Maskat, M. Y. (2011). Volatile compounds and lactic acid bacteria in spontaneous fermented sourdough. Sains Malaysiana, 40(2), 135–138

- Karssa, T., & Papini, A. (2018). Effect of clonal variation on quality of kocho, traditional fermented food from enset (Ensete ventricosum), Musaceae. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, 8(3), 79–85, doi:DOI: 10.5923/j.food.20180803.04

- Karssa, T. H., Ali, K. A., & Gobena, E. N. (2014). The microbiology of Kocho: An ethiopian traditionally fermented food from enset (Ensete ventricosum). International Journal of Life Sciences, 8(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijls.v8i1.8716

- Odunfa, S., & Oyewole, O. (1998). African fermented foods. Microbiology of fermented foods. Springer.

- Renes, E., Diezhandino, I., Fernandez, D., Ferrazza, R., Tornadijo, M., & Fresno, J. (2014). Effect of autochthonous starter cultures on the biogenic amine content of ewe’s milk cheese throughout ripening. Food Microbiology, 44, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2014.06.001

- Steinkraus, K. H. 1996. Handbook of indigenous fermented foods. Rev. and expanded. Food Science And Technology (USA). no. 73.

- Terefe, N. S. (2016). Food fermentation.

- Tsegaye, Z., & Gizaw, B. (2015). Community indigenous knowledge on traditional fermented enset product preparation and utilization practice in Gedeo zone. Journal of Biodiversity and Ecology Science, 5(3), 214–232

- Urga, K., Fite, A., & Biratu, E. (1997). Natural fermentation of enset (Ensete ventricosum) for the production of kocho. The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development (EJHD), 11(1)

- Weldemichael, H., Stoll, D., Weinert, C., Berhe, T., Admassu, S., Alemu, M., & Huch, M. (2019). Characterization of the microbiota and volatile components of kocho, a traditional fermented food of Ethiopia. Heliyon, 5(6), e01842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01842

- Woldemariam, F., Mohammed, A., Fikre Teferra, T., & gebremedhin, H. (2019). Optimization of amaranths–teff–barley flour blending ratios for better nutritional and sensory acceptability of injera. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1565079. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1565079

- Yirmaga, M. (2013). Improving the indigenous processing of kocho, an Ethiopian traditional fermented food. Journal Nutrition and Food Science, 3(1), http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000182