Abstract

This review focused on the livelihood diversification and food security situations in Ethiopia. Hence, the objectives of this review were to identify the determinants of rural household livelihood diversification and food security situations, to compile the major causes of food security of the rural households, to assess the food security status of rural households, and to review the effect of livelihood diversification on improving the food security status of rural households in country. The review was based on reviewing secondary data from journal articles, books, published and unpublished reports of national and international organizations, and policy briefs based on their relevance to the topic. According to the review, the country policy framework has focused only on on-farm agricultural development strategy and has not given adequate attention for non-farm and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies to assure rural households food security in the country. However, non-farm and off-farm strategies are currently the important strategies to rise the income of the rural households for improving the rural households’ food security. Currently, 57% of rural households were engaged in non-farm livelihood strategies. Therefore, this review will provide an adequate information to policymakers, planners, and other concerned bodies to intervene and improve the food security situations of the rural households in the country. Accordingly, future policies, strategies, programs as well as activities in the country should be focused on improving the food security situations in Ethiopia through promoting non-farm and off-farm rural livelihood diversification strategies.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In Ethiopia, where Agriculture is the main livelihood sector, which is highly vulnerable to weather shocks and frequent drought, diversification is becoming inevitable to increase the income of the rural poor and smooth their consumption. To this end, besides, non-farm and off-farm activities may be used as a strategy for coping risks and shocks to enhance their income and ensure food security situations of rural households. Therefore, understanding the main determinants of rural household livelihood diversification strategies and food security situations particularly the rural households is important for government officials and experts to formulate proper plans and strategies that target the different constraints to household livelihoods in terms of poverty reduction and food security. Therefore, this review will be a public interest since it creates a better understanding of the determinants and the dynamic process of rural livelihood diversification and food security situations in Ethiopia.

1. Introduction

Household food security is an issue and one of the major world agenda in 2018 in several contexts that distresses populations around the world today. According to Food Security International Network (FSIN, Citation2018), in 2017 about 124 million people in 51 countries faced a food security crisis. Conflict and insecurity are the major drivers of food insecurity, the number of food-insecure people across the world has been increasing over time (FSIN, Citation2018). Globally, the population has increased through time despite the question of how to feed the increasing number of people becomes difficult. In the world, in 2016, the number of undernourished people increased to an estimated 815 million, up from 777 million in 2015 but still down from about 900 million in the year 2000 (FAO, Citation2017). According to Livelihood and Food Security Technical Assistance (LIFT), between 2014 and 2015, approximately 7.5% of the world population experienced extreme food insecurity (LIFT, Citation2013). Issues of hunger and food security will only be exacerbated as the global population moves toward 10 billion people living on the earth in 2050. The number of people who are malnourished has increased to about 842 million, approximately 12% of the total population of the world (Abdullah et al., Citation2017).

Specifically, Africa remains the region with the highest prevalence of undernourishment with around one in four people out of about one billion estimated to be undernourished. To promote development in Sub-Saharan Africa, this global difference in malnourishment and food insecurity must be improved and addressed in a sustainable manner where agriculture is still largely in its subsistence stage as noted by Todaro and Smith (Citation2014). Therefore, enhancing food security has now become a global concern for world leaders and policymakers (Abdullah et al., Citation2017). As part of sub-Saharan Africa, the Ethiopian economy is predominantly dependent on and heavily concentrated on erratic rain-fed agricultural activities and it has been the least progress in the Sub-Saharan region. Ethiopian agriculture’s productivity is found to be low even though many households are engaged in and the country has implemented various agricultural policies. Since these policies focus mainly on on-farm agricultural development and neglect rich opportunities for non-agricultural livelihood diversification activities (Kassie et al., Citation2017). However, empirical studies consistently show that diversification to non-farm livelihood strategies enables farm households to have better incomes, enhance food security, and increase agricultural production by smoothing capital constraints and help to cope with environmental stresses (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Davis et al., Citation2014; Loison, Citation2015; Udoh & Nwibo, Citation2017). According to Gebru et al. (Citation2018) diversification into non-farm activities plays a significant role in the context of inadequate and rain-fed-dependent agricultural income households. The existing farm size for agriculture couldn’t enable people to generate adequate food required so that many poor households engage in non-farm and off-farm activities when their piece of land does not enable them to supply the required livelihood. Off-farm activities are mostly pursued by food-insecure households due to land shortage to produce sufficient food for consumption (Yishak et al., Citation2014). This implies that to supplement the income that households receive from on-farm activities and fulfill the income and food gap, farm households engage and pursue diverse non-farm and off-farm activities. Farm households that engage in highly productive non-farm activities typically enjoy upward mobility in earnings (Chawanote & Barrett, Citation2013). Diversification is to develop portfolios of income-generating activities with low covariate risk (Asravor, Citation2017). The ultimate goal of livelihood diversification is therefore bringing sustainable livelihood outcomes like securing more income, improved food security, reduced vulnerability, and increased welfare (Dinku, Citation2018).

Currently, diversifying livelihood activities is a common phenomenon in Ethiopia. Farm households engage and pursue diverse non-farm livelihood activities to cope with diverse challenges and risks such as drought (Kassie, Citation2017; Loison, Citation2015). Astonishingly, some rural households were pursuing non-farm and off-farm activities as the primary livelihood strategies rather than agriculture (Yishak et al., Citation2014). Since it is gradually becoming certain that the agricultural sector alone can’t be depended upon as the core activity for rural households as a means for improving business and accomplishing food security. In Ethiopia, empirical studies found that non-farm income accounts for as much as 40–45% of the average household income (Bezabih et al., Citation2010). In this regard, it is obvious that the contribution of non-farm income is immense but varies from place to place and people to people due to different contextual factors.

Therefore, this review has shown the various drivers of rural livelihood diversification strategies that have a distinctive impact on the propensity to enhance and the intensity of expansion at the household level and the food security situations in Ethiopia. It creates a better consideration of the dynamic process of rural livelihood diversification and promotion of rural household food security in Ethiopia and to makes the rural farming community beneficial through generating relevant information. At the country and Africa level, Birara et al. (2010), Sisay (Citation2013), Sarah (Citation2015), Abduselam (Citation2017), and Adem et al. (Citation2018), have reviewed Assessment of Food Security Situations in Ethiopia, Food Security Situations in Ethiopia, Income Diversification and Food Security Situation in Ethiopia, Rural livelihood diversification in Some African Countries, and Rural Livelihood Diversification in Some Sub-Saharan Africa, respectively. However, as far as the author’s knowledge is concerned, there was no single review conducted on the title “Livelihood Diversification and Food Security Situations” at the country level. As discussed above, this review was motivated by determinants of non-agricultural rural livelihood diversification strategies and food security situations in Ethiopia. In this review, the similarities and differences among findings of distinct studies on this issue in different areas of the country were reviewed.

The findings were varied i.e. in some areas the determinants of rural livelihood diversification strategies were found a significantly positive effect on the rural households’ food security situations and a significantly negative effect in the other areas of the country. Besides, while studies conducted on the determinants of livelihood diversification and food security separately found inconsistent results to analyze the effects of livelihood diversification strategies in promoting food security situations of the rural farming households in the Ethiopian context. Therefore, this review tried to compiled results of studies about determinants livelihood diversifications and food security situations of the country to identify research gaps and dissimilarities that significantly contribute to further investigations and interventions. The complied tangible pieces of evidence and information in this review will contribute and deliver a strong basis to understand in depth the determinants of livelihood diversification and food security particularly in rural areas by providing detail and insightful findings from different sources. The review will add in various ways to the body of knowledge on the important subject of determinants of livelihood diversification and food security and the nexus between livelihood diversification and food security in Ethiopia.

1.1. Objectives of the review

To identify the determinants of livelihood diversification and food security situations of rural households in Ethiopia.

To compile the major causes of food security situations of the rural households in Ethiopia.

To assess the food security status of rural households in Ethiopia.

To review the effect of livelihood diversification on improving the food security status of rural households in Ethiopia.

2. Review methodology

Data collection in the review article is undertaken document analysis through an in-depth review of related literature from a different source (Albore, Citation2018). In the same manner, to achieve the review objectives data were collected from the intensive finding review of published and unpublished materials like books, research articles, published and unpublished reports from national and international organizations (governments), non-governmental organizations, policy briefs, and other indexed scholarly materials. The search was executed from 20 March 2020, up to 5 November 2020. In this review, almost all relevant sources that were released between 1996 and 2020 were included. After 310 documents were retrieved, only 166 were included based on their importance to the topic. The review has discoursed some concepts and tangible pieces of evidence about livelihood diversification and food security situations of rural households in Ethiopia with specific topics of concepts and definitions applied in livelihood diversification strategies and food security analysis, determinants of livelihood diversification strategy choices of rural households, the effect of livelihood diversification on the food security status of rural households in Ethiopia, determinants of food security status among rural households, and other related topics have also been enclosed. In addition to the narrative, this review compiled and presented the pieces of evidence and information through employing figures and tables which were adopted from the recognized sources of findings and computed by authors themselves from the whole document review.

3. Review of related literature

3.1. Concepts and definitions applied in livelihood diversification analysis

Livelihood: The term livelihood is often used interchangeably with economic strengthening and refers generally to economic production, employment, and household income. A popular definition is that provided by Chambers and Conway (Citation1992) wherein a livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (including both material and social assets), and activities required for a means of living. Livelihood is a generic term that involves several components (De Haan, Citation2012). Thus, there is no universally endorsed definition to grasp the term livelihood (Scoones, Citation2009). Vital components of this definition are assets, capabilities, and activities required for means of living. According to Krantz (Citation2001) assets are resources that households combine to choose between available options of living for positive outcomes.

Livelihood strategies: It is defined as a process by which household members construct a diverse portfolio of activities and social support capabilities in their struggle for survival and to improve their standards of living (Ellis, Citation1998). It can be defined as the maintenance and continuous alteration of a highly varied range of activities and occupations to minimize household income variability, reduce the adverse impacts of seasonality, and provide employment or additional income (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Loison, Citation2015).

According to DFID (1999) livelihood strategies are defined as the range and combination of activities and choices that people make to achieve their livelihood goals, including productive activities, investment strategies, and reproductive choices, etc. Similarly, livelihood strategies are made out of activities that produce the methods for household endurance and are the arranged activities that people embrace to assemble their livelihoods (Ellis, Citation2000).

Livelihood diversification: Is characterized as a procedure by which household members build various arrangements of exercises and social help capacities in their struggle for survival and to improve their ways of life (Ellis, Citation1998). Livelihood diversification is often defined as a process by which rural households make a more diverse range of activities to survive and advance their standard of living. Livelihood diversification refers to a key system occurring at various degrees of the economy, which are normally however not in every case straightforwardly connected (Start, Citation2001).

3.2. Concepts, definition, and pillars applied in food security analysis

3.2.1. Concepts and definition of food security

Food is both a need and a human right. Enough food regarding amount and quality for all individuals is a significant factor for a healthy and productive life as well as for a nation to sustain its development just as for a country to continue its turn of events (GAO, 2016). Food is both a need and a human right, yet food instability is predominant in this day in general, and sub-Saharan Africa in particular (GAO, 2016). According to Maxwell Daniel (Citation1996), Ehui et al. (Citation2002), and FAO (Citation2007) food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. The concept in which the root concern with food security can be traced back to the world food crises of 1972–74: and, beyond that, at least to the Universal Declaration of Human Right in 1948, which recognized the right to food as a core element of an adequate standard of living (Maxwell & Smith, Citation1992; Stephen, Citation2007). Food security is defined, according to the World Food Summit of 1996, as existing “when all people at all times have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life”. This commonly refers to people having “physical and economic access” to food that meets both their nutritional needs and food Preferences (WHO, Citation2010).

3.2.2. Pillars of sustainable food security

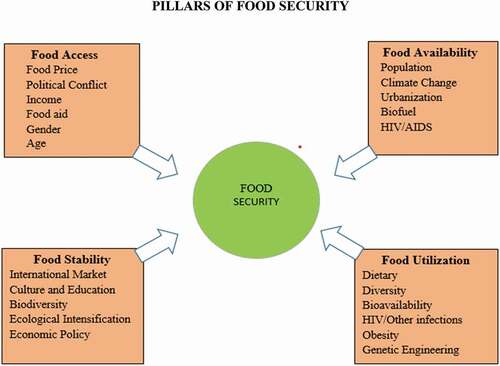

Sustainable food security is a broad phenomenon that requires a wide scope of factors that must be very much considered in structuring a system a strategy to that end. Manageability ought to be considered as a long-term time dimension measurement in the evaluation of food security. According to Kannan et al. (Citation2000), Pinstrup-Andersen (Citation2009), Barrett (2010), and Jennifer (Citation2013) the major pillars of food security that specialties and consultants believed are critical to achieving its sustainability include food Availability, Access, Utilization, and Stability. Based on different literature, this review identified and elaborated on the four dimensions of food security which are food availability, food stability, food accessibility, and food utilization. A brief explanation of the pillars of food security is presented in .

Table 1. Explanation of pillars of food security

3.2.3. Information required in food security and livelihood assessment

A single indicator or several indicators of a single type (e.g., food availability) is akin to having only one piece of the puzzle. At best one has only a partial picture. For example, knowing that there is plenty of food available says little about food accessibility or utilization. The more pieces of the puzzles that are put together the more clearly one can identify the complete picture. Essential indicators to be included in all food security and livelihoods assessments are listed in the table below. This core set of indicators is considered to represent the minimum package to be applied across all contexts and assessment types without which the basic food security and livelihood analysis will be incomplete. Meanwhile, methods for gathering information on each indicator will vary according to the context, assessment timeframe, and depth of analysis that is required. A much larger dynamic range of indicators exists for assessing the many dimensions of a population’s food insecurity and risks to livelihoods (ACF, Citation2020). shows the category, indicators, and description of food security and livelihood indicators.

Table 2. Core food security and livelihhod indictors

3.2.4. Additional factors of food security

During the literature review, other additional factors that have significant effects on sustaining food security were identified. These additional factors as shown in ) were grouped into corresponding sub-factors as they inter-relate with each of the primary pillars of food security. shows a pictorial representation of the relations.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Determinants of rural livelihood diversification

More than 80 percent of people in Ethiopia rely on agriculture and livestock for their livelihoods. Yet the increasing frequency and magnitude of climate disasters and plant pests over the years have left many communities particularly vulnerable to food insecurity (FAO, Citation2020c). According to Zerai and Gebreegziabher (Citation2011b) the participation of households into non-farm and off-farm activities are influenced by complex and yet empirically unidentified factors. The pull factors are favorable factors or opportunity-led and lead to diversification of livelihood strategies, whereas push factors are survival-led or harsh conditions that force farm households to diversify their income activities off their main income-generating activity (Asravor, Citation2017). It is not clear why some households participate in different income-generating activities while others participate in farming only. Most of the determinants of non-farm activity participation relate to household demographic, institutional, and socioeconomic characteristics. According to Zerihun (Citation2016) household size, access to credit, and access to electricity increase the number of non-farm activities in which households participate. As long as smallholders have enough factors of production such as land, labour, and capital (in the form of assets like livestock and oxen) and on-farm income is reliable, they are less likely to engage in non-farm activities. This means that non-farm activities are perhaps considered as an alternative means of securing income during agricultural off-seasons (Zerihun, Citation2016). It is, thus, important to identify the major factors influencing non-farm and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies and their effect on the food security status of rural households through reviewing previous works that are related and relevant to the topic.

According to Gebru et al. (Citation2018), age was found significant to negatively influence smallholder farmers’ livelihood diversification into on-farm + non-farm income-generating activities. The likely reason is that young households are relatively better educated, have better access to technologies, and look for alternative livelihood opportunities. Besides, the age structure of household heads was found to be negatively and significantly affecting pastoralists’ decision choice of pastoral and off-farm combination and pastoral and nonfarm combination. This implies that in comparison with those who use only pastoral livelihood options as their livelihood means (base case), a year increase in age of household heads will likely shift choices of farmers’ livelihood options to off-farm and non-farm activities (Dinku, Citation2018).

Across livelihood diversification strategies, sex has a negative and significant relationship to agriculture plus off-farm and agriculture plus non-farm plus off-farm livelihood strategy choices (Misganaw et al., Citation2019; Nigussie, Citation2017; Shambel & Rajan, Citation2017). On the other hand, the sex of a household head was found to have a significant and positive relation with off-farm and non-farm wage, self, and mixed self-wage employment activities (Demissie, Citation2013). According to Woldenhanna and Oskam (Citation2001), Lanjouw et al. (Citation2007), Kimsun and Sokcheng (Citation2013), and Arega et al. (Citation2013), and Baharu Gebreyesus (Citation2016) the age of the household head affected the level of rural household livelihood diversification negatively and significantly. According to these findings, the age of the household head was adversely identified with farmers’ choice to enhance to non-farm and off-farm activities.

According to Woldenhanna and Oskam (Citation2001), Lanjouw et al. (Citation2007), Kimsun and Sokcheng (Citation2013), Shambel and Rajan (Citation2017), and Misganaw et al. (Citation2019) family size has a positive and significant relationship to livelihood diversification. This result is consistent with other studies in Africa (Canagarajah et al., Citation2001) for Ghana and Uganda and Senadza (Citation2012) for Ghana household size increases participation in non-farm activities with the number of non-farm activities increasing by approximately 8.6% with everyone person increase in the household. This means large family size households were tending to participate more in non-farm and off-farm activities. A large family might be enforced to divert part of its labor force into non-farm activities to generate more income and reduce consumption demands (Tizale, Citation2007). This implies that the household’s family size affects the diversity of household income sources.

Dependency ratio significantly affected the type of diversification strategy practiced (Asravor, Citation2017). An increased dependency ratio will push the household into diversifying into other activities that can bring more income to the household (Khatun & Roy, Citation2012). Similarly, the dependency ratio is found to have a significant and positively correlated with the choice decision of rural livelihood diversification strategies (Khan, Citation2007; Shambel & Rajan, Citation2017). The increase in reliance ratio and the capacity to address subsistence needs declines and the reliance issues make it important in the household to enhance their salary source. On the contrary, households with higher reliance proportions follow less gainful non-farm livelihood strategies (Misganaw et al., Citation2019). This implies that households with a high dependency ratio have a low probability level to participate in off-farm and nonfarm income-generating livelihood diversification strategies. The possible explanation for this could be attributed to the fact that the availability of an increased number of individuals whose age is below 15 and above 64 implies that the availability of a large number of dependents who are unable to engage themselves in non-farm income-generating livelihood activities (Gebru et al., Citation2018).

According to Yishak et al. (Citation2014), Yenesew et al. (Citation2015), and Prowse (Citation2015) the rural household head is highly influential in the decision-making process in the family. Regarding the education level of the household head, the more educated household heads are engaged in non-farm and off-farm diversification strategies. Education is an important determinant to participate in the non-farm sector (Salam et al., Citation2019). This is because the better-educated households are fit for computing the expenses and benefits of income-generating activities and thus, empower them to participate in non-farm and off-farm and activities. As the schooling year of household heads for education increases by one unit, the likelihood of the probability of participation in agriculture plus non-farm income source will increase by 6.5% (Ansho & Shiferaw, Citation2016).

The availability of land is apart from human capital and is also a principal in rural livelihoods (Barbier & Hochard, Citation2014). They have found that area of land owned by the household has a significant and negative association with the probability of selecting a diversified livelihood. This means that the households with large land size are participated less in non-farm and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies and participated more in on-farm strategy only. This is plausible may be due to households with more land tend to follow agricultural extensification rather than diversification. Similarly, (Barrett et al., Citation2001; Corral & Reardon, Citation2001; Escobal, Citation2001; Janvry & Sadoulet, Citation2001; Kimsun & Sokcheng, Citation2013; Lanjouw et al., Citation2007; Reardon et al., Citation1998; Woldenhanna & Oskam, Citation2001) revealed that farmers with large farm size are less likely to diversify the livelihood strategies into non-farm and off-farm than those farmers who have small land size. Since large farm size supports farmers to cultivate and produce more, which in turn increases farm income. On the other hand, decreasing land sizes under population pressure may inspire rural households to diversify their sources of income.

Livestock is the most important indicator of wealth in rural Ethiopia. According to Nigussie (Citation2017) livestock holding has a significant positive correlation with livelihood diversification strategies. Besides, Demissie (Citation2013) found that livestock holding significantly and positively affects participation in wage activities. Households with more livestock holding do have the capacity to participate in profitable non-farm and off-farm employment activities than those households with no or small size livestock holding. Conflicting to this result, livestock holding affected the level of livelihood diversification significantly and negatively (Adugna Eneyew, Citation2008; Yishak et al., Citation2014; Baharu Gebreyesus, Citation2016). The potential reason could be households who attained the required amount of cash from livestock may not need to involve in non-farm and off-farm activities for additional income whereas farmers with lower livestock holding may be obliged to diversify livelihoods into non-farm and off-farm activities to fulfill household assets and achieve their food security.

Demissie (Citation2013) and Gebreyesus (Citation2016) revealed that walking distance to the nearest market yielded a positive and significant influence on the level of livelihood diversification. The likely reason for a positive and significant relationship between market distance and non-farm and off-farm activities could be that residing nearer to the market enables farm households to engage in non-farm and off-farm activities mainly trading and service provision. Nearness to the market center makes access to additional income via non-farm and off-farm employment opportunities, easy access to information on inputs, and transportation (Dorward et al., Citation2003; Gemechu et al., Citation2015). Prowse (Citation2015) revealed that distance to markets and towns and availability of electricity are considering as location variables determinants of non-farm income diversification in rural Ethiopia. On the contrary, the more households are distant from the market center, the more disadvantaged from diversifying their livelihood income into non-farm options (Gebru et al., Citation2018).

According to Yishak et al. (Citation2014) and Seid (Citation2016) incomes of the household were found to have a positive and significant influence on the household’s choice of on-farm plus non-farm, and a combination of on-farm, non-farm, and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies. The conceivable explanation can be farm households with a large total income can invest in alternative livelihood strategies, especially in non-farm activities. Because adequate income sources can overcome financial constraints to engage in alternative non-farm and off-farm activities. Similarly, households with high annual income have a high probability of choosing and diversifying their livelihood into high-income return off-farm and non-farm activities (Gebru et al., Citation2018).

Credit serves as a means to be involved in livelihood diversification activities. Livelihood diversification strategies were significantly influenced by access to credit. The possible reason is with access to credit, households have basic capital to diversify into either farming or non-farming business or both (Amevenku et al., Citation2019). According to Reardon et al. (Citation1998), Barrett et al. (Citation2001), Corral and Reardon (Citation2001), Janvry and Sadoulet (Citation2001), Woldenhanna and Oskam (Citation2001), Lanjouw et al. (Citation2007), Kimsun and Sokcheng (Citation2013), and Gebreyesus (Citation2016) access to formal credit was found to have a positive effect on the level of livelihood diversification. Smith et al. (2001) and Davis (Citation2004) differentiated that lack of access to financial services or the lack of credit as a limitation to the potential expansion into separated from farm economic activities. The decision of households’ participation in rural livelihood diversification is expected to have a positive correlation in the preferred livelihood strategy.

According to Eneyew (Citation2012) have indicated there is a positive relationship between having the opportunity of receiving remittance and sharing in diversified livelihood sources. Even though remittance constitutes a small part of total households’ income, it is proposed to have a positive contribution to the diversification of livelihood activities. The variable had a positive influence on the livelihood strategies apart from agriculture plus non-farm and agriculture plus off-farm activities. This meant that the likelihood of a household receiving remittance from any source increases the choice of livelihood strategy into agriculture plus non-farm plus off-farm activities (Shambel & Rajan, Citation2017).

In Ethiopia, the conflict between bordering ethnic communities within the same region is likely to increase during the transition period as forceful requests for different benefits by different ethnic groups will continue. This could result in temporary disruptions in livelihood activities including agricultural practices, delivery of humanitarian assistance, movement of people for labor activity, and trade flows. According to FAO (Citation2020b) if the conflict between different ethnic groups is sparked, more people will be displaced and the number of Internally Displaced Populations (IDPs) will increase, which will increase the need for humanitarian assistance and the number of people who will be in Emergency would significantly grow. “Social unrest, triggered by longstanding issues that could now be aired in a more open civic and political environment, had led to conflict, the loss of lives and property and, at last count, 1.7 million internally displaced persons,” the assessment, which will inform policies and programs aimed at helping Ethiopia recover (UNDP, Citation2020).

4.2. Determinants of food security status among households

In Ethiopia, the causes and determinants of food security are debatable and there are highly contested viewpoints between the academic disciplines and in development thinking in general. Besides, according to several studies that this review considered, determinant factors that affect the rural households’ food security status are different from one study area from another in the same country because of differences in resource availability, topography, time dimension, and other factors. Besides, the factors for food security involve demographic, socioeconomic, environmental, and other multidimensional causes (Phalkeya et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it is rational to identify the main factors which determined rural households’ food security status in Ethiopia for further investigation and intervention. The following factors are identified as the major determinant factors of rural households’ food security status in Ethiopia.

According to Tolosa (Citation2002), Ramakrishna and Demeke (Citation2002), and Kidane et al. (Citation2005), the livelihood of female-headed households was disadvantaged when compared to their male counterparts. Households headed by females were 2 times more likely to be food insecure than households headed by males. This confirms that households headed by a female were more likely to be food insecure than households headed by males (Shone et al., Citation2017). This is because the researchers justify, female household heads have limited access to livelihood assets like land, education, saving, labor force, and oxen (drought power), livestock, and credit services.

According to Bogale and Shimelis (Citation2009) the socio-economic variable age of the household head had a significant influence on food insecurity in rural areas of Dire Dawa, Eastern Ethiopia. Since improvement in the food security situation requires building household assets, improving the functioning of rural financial markets, and promoting family planning. Households headed by persons aged >65 years were 6.5 times more likely of being food insecure compared to a household headed by persons aged 18–44 years (Shone et al., Citation2017). This fact has supported the study by Mota et al. (Citation2019), that age of household head was significantly and positively associated with food insecurity. This implies the household headed by aged one is more likely to be food insecure than households headed by young or productive age. According to Bezabih et al. (Citation2010), Fikrie (Citation2014), and Agidew and Singh (Citation2018) in their study on determinants of food security and related issues, among rural households of central Ethiopia and Northern Ethiopia respectively, observed that the age of the household head was seen as critical and had a positive effect in deciding household food security of the family. According to Babatunde et al. (Citation2007), Girma (Citation2012), Sisay and Edriss (Citation2012), Siraje and Bekele (Citation2013), and Fikrie (Citation2014) family size has a negative influence on food security and since most of the farm households are smallholder subsistence producers, an increase in the number of individuals in the family will apply more weight on utilization than the work it contributes.

Land size owned by household heads was found to have a significant and positive relationship with the food security status of households. It implies that the larger the land size, the better food secure state of the household (Fekadu & Mequanent, Citation2010; Barbier & Hochard, Citation2014; Hiwot, Citation2014; Muraoka et al., Citation2014; Mohammed, Citation2015; Negera, Citation2018). The possible explanation is that the major source of food comes from its production and there was limited access to other means of income-generating activities. Households with large farmland produce more for household consumption and sale; thus have a higher chance to be food secure than those having a relatively small size of farmland.

According to Muluken (Citation2005) and Fekadu and Mequanent (Citation2010) food production is positively affected and increased extensively through the expansion of livestock that brings not only food for the producers but also, other products which might be sold to provide food or income. The study on determinants of food security among rural households of central Ethiopia observed that livestock ownership, oxen ownership were found to be significant in determining household food security (Aragie & Genanu, Citation2017; Fekadu & Mequanent, Citation2010; Siraje & Bekele, Citation2013). This is consistent to (Tesfaye, Citation2005; Okyere et al., Citation2013; Muraoka et al., Citation2014; Barbier & Hochard, Citation2014; Asmelash, Citation2014; Mohammed, Citation2015; Negera, Citation2018) increasing livestock productivity will immensely contribute to the attainment of food security. This implies that the size of livestock has a positive impact on the food security status of the household. In other words, possession of more livestock implies a higher likelihood of food security. The possible explanation is that livestock has many socio-economic benefits to farm households and is perceived as an indicator of wealth status.

Agbola (Citation2004) and Fekadu and Mequanent (Citation2010) in their study on determinants of food security among rural households of central Ethiopia observed that the use of chemical fertilizer was found to be significant in determining household food security. Amare (Citation2001) verify that agricultural inputs such as improved seeds, fertilizers, herbicides, and farm implements which are vital to increasing production and productivity are not well accessed by most peasants due to the high cost of chemical fertilizers and improved seeds, the poor performance of the market, lack of competitions and monopolization of input supply in the hands of the government, and low market values of agricultural producers. However, there is a positive association between the amount of fertilizer applied in farming and the accomplishment of food security (Fekadu & Mequanent, Citation2010; Stewart & Roberts, Citation2012). This implies that there is a positive association between the amount of fertilizer applied in farming and the achievement of food security.

According to Bogale and Shimelis (Citation2009) the amount of the socio-economic variable of credits received has a significant influence on food security in rural areas of Eastern Ethiopia. Their findings inferred that improvement in food security circumstances requires building a household asset, improving the working of financial markets, and advancing family planning using credit service. Credit service is a critical illustrative variable that affects food security that is a positive effect on household food security. Households who have received the credit could fulfill their food needs and to influence the household food security status positively (Gezimu, Citation2012; Sisay & Edriss, Citation2012; Wali & Penporn, Citation2013; Barbier & Hochard, Citation2014; Hiwot, Citation2014; Mohammed, Citation2015).

The education level of the household head highly influences the food security and nutrition of the household and it is a critical determinant of food security. According to Tolosa (Citation2002) and Negera (Citation2018) low level of education is one of the causes of the occurrence of seasonal food shortages in farm households. Educational achievement by the family head could prompt awareness with the potential advantage of modernizing agriculture by methods for mechanical information sources; empower them to peruse guidelines on compost packs and broadening of family livelihoods which, thus, would improve households’ food security. In other words, the education level of the household head has a negative and significant effect on household food insecurity (Kidane et al., Citation2005; Meskerem & Degefa, Citation2015). This indicates that education is negatively correlated with food insecurity.

Sisay and Edriss (Citation2012) noted that household income determined the food security status of farming households in Ethiopia. Non-farm income was found to have a significant and positive relationship with the food security status of the household that showed farmers occupied with non-farm activities have a better opportunity to be food secure (Asmelash, Citation2014; Barbier & Hochard, Citation2014; Mohammed, Citation2015; Aragie & Genanu, Citation2017; Hussein, Citation2017). This might be because households engaged in non-farm activities are better endowed with additional income and more likely to escape food insecurity. This finding is consistent with the finding of food secure authors (Mulugeta, Citation2002; Muluken, Citation2005; Shemelis, Citation2003; Tesfaye, Citation2005). Besides, total annual income and off-farm income of the household and food security would be positively related (Muluken, Citation2005; Gezimu, Citation2012; Sisay & Edriss, Citation2012). According to Siraje and Bekele (Citation2013) income from livestock production and non-farm income was working against food insecurity.

5. Causes and food security situation in Ethiopia

The failure of Sub- Saharan African countries to feed their population has been attributed to climate shocks, mainly drought and the subsequent water scarcity, resource degradation, bad governance and inefficient policies, widespread epidemic, technological stagnation, and conflict (FAO & WFP, 2010). The food security situation in Ethiopia is highly linked up to severe, recurring food shortage, and famine, which is associated with recurrent drought (USAID, 2012). Currently, there is a growing consensus that food insecurity and poverty problems are closely related in the Ethiopian context. For that reason, poverty reduction and improving food security condition has been a significant part of the Millennium Development Goals (FDRE, Citation2012; MoFED, Citation2010). Empirical evidence on food security in Ethiopia checked the predominance of a higher level of food fragility with huge strange and spatial highlights. The particular food security studies by Zegeye and Hussien (Citation2011), Abebaw et al. (Citation2011), and Hailu (Citation2012) for the most part ecommend that the depth and intensity of food instability are high, impacted by the poor working of showcasing frameworks and other households and socioeconomic factors. Poverty and food insecurity remain widespread and the main challenges in Ethiopia (Mekonnen & Gerber, Citation2017). According to Shone et al. (Citation2017), the overall prevalence of household food insecurity was 38.1%. Even though Ethiopia has made development gains over the last two decades (WFP, Citation2020), 27% of the population, or 30.2 million people, were still living below the poverty line (USD 1.90 a day). Ethiopia is considered by many to be one of the most under-developed nations in the world. It is with a population of more than 100 million is often characterized by structurally food insecure and drought-prone country in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia’s population by 2020, 114,364,556 with one of the highest food insecurity levels in the world (USAID, Citation2017). The food security situation of Ethiopia varies from place to place and it remains the country with the highest prevalence of food security problems in the continent of Africa. According to Stephen and Farmer (Citation2015), a large proportion of the country’s population has been exaggerated by chronic and transitory food insecurity. Empirical evidence of food security in Ethiopia indicates the existence and the prevalence of a high level of food insecurity, with significant individual and spatial characteristics (Hailu, Citation2012). The food security situation in Ethiopia is highly affected by recurring food shortages and famine which are highly linked with recurrent drought, unusual floods, desert locusts, and the combined effects of COVID-19 (FAO, Citation2020c). The proportion of households reporting poor food consumption (Food Consumption Score) has deteriorated slightly from 37 percent in August 2019 to 41 percent in Feb 2020. Besides, the quality of household diet (Dietary Diversity Score) has worsened slightly in February 2020 (3.07) against 3.45 in August 2019 (FAO et al., 2020). Empirical studies confirmed that the main reasons for food security in Ethiopia are conflict, insecurity, crop disease, prolonged drought, etc.

In Ethiopian history, this drought was the strongest drought that has been faced as reported by different agents like Ethiopian CSA, WFP, and FAO (Abduselam, Citation2017). Consequently, the food security situation in Ethiopia deteriorated sharply in 2017. In Ethiopia, the number of food-insecure population was increased from 5.6 million in December 2016 to 8.5 million in August 2017 (ACAPS, Citation2018). An estimated 3.6 million (Approximately 54%) children and women in Ethiopia were acutely malnourished in 2017 (IFRC, Citation2018). Besides, according to the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) report, crop and pasture loss from the current desert locust outbreak, due to ongoing conflict and climatic shocks approximately 6.4 million people will require food assistance during the year (HRP, Citation2020). In Ethiopia, 3.2. Million people were internally displaced due to climatic shocks and conflict. The Government of Ethiopia had returned 2.1 million displaced people to prior areas of residence despite conflict continues to drive displacement, leading to food insecurity (IDPs) (HNO, Citation2019). In Ethiopia prolonged drought conditions are severely affecting the livelihoods in most Southern and South-Eastern pastoral and agro-pastoral areas of Southern Nation, Nationalities and Peoples of Ethiopia (SNNPR), Southern Oromia, and South-Eastern Somali Regions, where cumulative seasonal rainfall was up to 60 % below average (FAO, Citation2018). In the areas, crop production and livestock conditions were severely affected due to the decline of pasture and water availability (FEWS NET and WFP, 2018).

Presently, the household’s ability to engage in their typical livelihood activities like seasonal cultivation and raising of livestock have been disrupted by the displacement and has resulted in a food security crisis in the region where conflict has been reported to be most severe. Moreover, large parts of the country especially maize-producing parts of SNNPR, Western Oromia, Amhara, Gambela, and Benshangul Gumuz were affected by the fall armyworm outbreak (ACAPS, Citation2018; FEWS NET and WFP, 2018). In 2018 with the reduced output of 2017 harvests and decreased food access as a result of poor purchasing power and the exhaustion of coping mechanisms, the food security situations in Ethiopia remain acute (ACAPS, Citation2018). In Ethiopia, the increase in humanitarian assistance is primarily due to increased drought-related needs in the Southern and South-Eastern parts of Ethiopia.

Generally, both human and physical factors are responsible for the persistence of food insecurity in Ethiopia. Human factors like poor environmental management and weak policies also play an important role. Besides, political factors (inadequate response by the government and the international community) play a major role. According to Dagnachew (Citation2012) the major physical factors that are responsible for food insecurity include recurrent drought, environmental degradation, unexpected floods, desert locust, poor soil fertility, crop diseases, and pest infestations, lack of access to technology, credit facilities, lack of alternative sources of income outside agriculture, and increased population pressure.

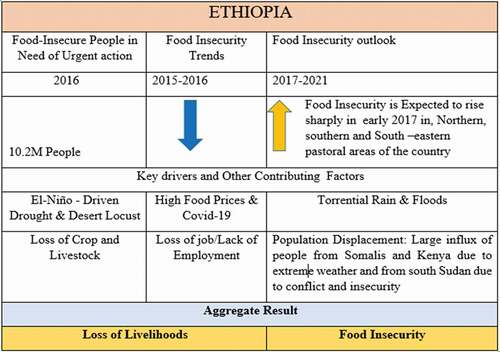

In Ethiopia, household food security largely depends on external factors including rainfall patterns, land degradation, climate change, population density, low levels of rural investment, and the world market (WFP, Citation2011). Practically 50% of rural households in Ethiopia were influenced by the dry season in a five-year time frame from 1999 to 2004 (Dercon et al., Citation2005). Recently drought affected a significant proportion of the population in risk-prone areas of the country (GOV, Citation2016). shows a summary of the status of household food security in Ethiopia.

Table 3. Summary of status of household food security in Ethiopia

5.1. Impact of natural disasters on food insecurity situations in Ethiopia

An estimated 8.5 million people are estimated to be severely food insecure in early 2020, mainly in eastern agricultural areas and in northern and southeastern agro-pastoral areas due to poor 2019 “Karan/Belg/Gu/Genna” seasonal rains between early and mid-2019. Following the failure of rainfall during the 2015 agricultural seasons, estimates suggest that about 10.1 million people required emergency food assistance as of December 2015 (EHRD, Citation2016). On the other hand, as of January, about 512 000 people have been affected by floods triggered by torrential rains since October (FAO, Citation2020a). According to FEWS NET (Citation2020b) natural disasters and extreme weather events were a primary driver of food insecurity in 2020 in Ethiopia due to inadequate capacities to respond to shocks and with a population characterized by low resilience.

The broader economic crisis that is emerging because of the COVID-19 crisis also poses enormous challenges for food security and nutrition in Ethiopia. The COVID-19 pandemic is already affecting food systems directly through impacts on food supply and demand, and indirectly through decreases in purchasing power and in the capacity to produce and distribute food, which will have differentiated impact and will more strongly affect the poor and vulnerable (FAO et al., 2020).

In Ethiopia, COVID-19-related mitigation measures, in combination with recent flooding and crop losses caused by desert locusts, are projected to result in below-average secondary season harvest in June-July. The Deseret locust causes an estimated 3,562,856 quintal cereals losses. Due to this about one million individuals in Ethiopia have been affected by the Desert Locust invasion and require emergency food assistance (Jalata & Mulugeta, Citation2020). This is likely to worsen the food security situations in the country (AGRA, Citation2020). Humanitarian assistance needs in Ethiopia are notably higher than in recent years and months, driven largely by compounding effects of COVID-19 related restrictions, continued drought recovery, atypically high food prices, conflict, floods, and desert locusts (FEWS NET, Citation2020a). According to the World Bank reports; Ethiopia will be the most affected country by desert locust with potential losses valued at up to 2.8 USD billion (World Bank, 2020) and the number of food-insecure people has increased to 16.5 M (AGRA, Citation2020). shows the relationship between food security and its key drivers.

Besides, the effect of climate change risks is resulting from frequent and intense extreme events which include drought, floods, heavy precipitation and snow events, and long-term changes in temperatures and precipitation patterns (Bals et al., Citation2008; FAO, Citation2008, Citation2016a). Yet, farmers’ vulnerability to changes is a function of the magnitude, duration, and frequency of shocks as well as their ability to respond to them (Frankenberger & Nelson, Citation2013). Although agricultural production has increased for decades (Abebe, Citation2017), the effects of El-Niño have caused droughts and heavy rainfall events resulting in loss of harvest in districts of Afar, Amhara, SNNPR, Oromia, Somali, and Tigray Regions since 2015 (FEWS NET, Citation2015/2016; OCHA, Citation2015; ACAPS, 2016; FAO, Citation2016b; IFRC, Citation2016). According to Abate (2017) climatic factors and natural resource availability are critical factors of food security in Ethiopia, where more than 80% of the population makes a living from agriculture. briefly presents the effects of climate change risk on food security.

Table 4. Climate change and food security

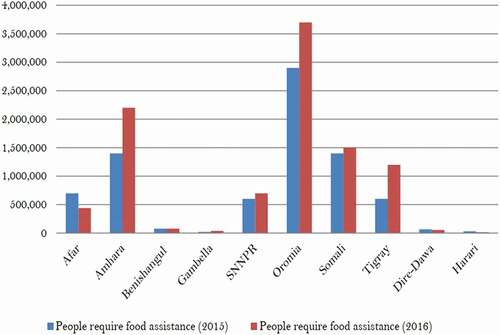

An estimated 10.2 million people required food assistance in 2016 fall back to 5.6 million in 2017 (UNICEF, Citation2017). This source paradoxically indicates the increasing number of hotspot districts in the country that require food assistance from 158 in July 2016 to 192 in January 2017. In Ethiopia, a large number of people need multi-sectoral responses than food security such as health, nutrition, education, water, and sanitation (UNICEF, Citation2017). suggests not only the pervasive effects of drought but also the problematic future of the people. Climate change in the form of prolonged droughts, floods, and failure of rains not only affects food production negatively but also have an impact on the available non-farm wage employment opportunities (FAO, Citation2016a). shows the regional variation in the number of people who required relief food assistance between 2015 and 2016 in Ethiopia.

6. Food insecurity and malnutrition analysis in Ethiopia

Ethiopia is one of the most food-insecure and famine-affected country. A large portion of the country’s population has been affected by chronic and transitory food. Food insecurity is an enduring, critical challenge in Ethiopia which is Africa’s second populous country after Nigeria. In Ethiopia, food insecurity is highly prevalent in the moisture deficit highlands and in the lowland pastoral and agro-pastoral dry land areas. According to (Food Security Information Network[FSIN], 2020), Ethiopia was the most food-insecure country among Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD) countries with 8.1 million food-insecure people in need of urgent action. However, in the food insecurity community, there has been a lack of clarity and common definitions for classifying various food insecurity situations in terms of varying severity. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) is, therefore, designed to fill this critical gap in food insecurity analysis. The IPC is a means to classify varying phases of current food insecurity situations based on outcomes on human lives and livelihoods. IPC 2020, classifies food insecurity into five phases; phase one (People minimally food insecure), phase two (People in Stress), phase three (people in crises), phase four (people in an emergency) and phase five (people in catastrophe) (IPC, Citation2020). Therefore, the food security situations of Ethiopia need to be classified based on outcomes on human lives and livelihoods in Belg, Belg pastoral, agro pastoral, and Meher areas. The food insecurity analysis between July and September 2019 is conducted in six regions of Ethiopia indicates that, despite ongoing assistance, an estimated 8 million people (27% of the 28.7 million people analyzed) were severely food insecure in IPC Phase 3 (Crisis) or worse. Of these, about 6.1 million people were classified in IPC Phase 3 (Crisis) and about 1.9 million people in IPC Phase 4 (Emergency). This result is inconsistent with the analysis which was conducted between October 2019 and January 2020, Ethiopia’s food security situation is likely to improve slightly due to the seasonal (Meher) harvests. However, the below normal Belg season production, conflict and climate-induced displacement, high food prices, and the long dry spell in the northeastern pastoral areas will likely affect the food security situations resulting in about 6.7 million people expected to be in Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse. Food insecurity is influenced by food and non-food related factors. Moreover, the food security situation during the October to December 2020 period indicates that about 8.6 million people (17% of the analyzed population of about 53 million people) require urgent action to save lives, reduce food gaps, save and protect livelihoods, and reduce and prevent acute malnutrition.

The IPC projection conducted during the period from January to June 2021 includes an updated IPC analysis of the August 2020 Belg, pastoral and agro pastoral livelihoods, as well as first projection analysis for Meher livelihoods. During this period, Belg, pastoral and agro pastoral areas will experience the lean season, as well as seasonal rainfall and cropping between February and May. Meanwhile, Meher areas will be in the post-harvest period. According to this analysis, the total of 12,871,469 million people (24% of the analyzed population of about 53,977,213 million) are expected to face high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above) despite planned humanitarian food assistance and other development interventions. This includes 5% of the population (about 2.6 million people) classified in Emergency (IPC Phase 4) and 19% (about 10.3 million people) classified in Crisis (IPC Phase 3) (). At country level, out of 12,871,469 million people in IPC Phase 3 or above, who required urgent action to save lives, reduce food gaps, restore livelihoods and reduce malnutrition, 6 % (784,961) are in Afar, 14% (1,795,303) in Amhara, 38% (4,851,785) in Oromia, 15% (1,978,449) in Somali, 3% (360,758) in Sidama, 18% (2,338,960) in SNNPR, and 6% (761,255) in Tigray (). The higher number of people who required urgent action are live in Amhara region(1,795,303 million people) and the lowest number of people who require urgent action are live in Somali regional state (360,758 million people). However, at region level, the number of millions of people who are expected to face high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above) are live in Afar regional state (784,961, 42% of 1,575,439). Whereas the lowest number of people are expected to face high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above) are live in Sidama region (360,758, 10% of 3,607,577) ().

Table 5. Different phases of current food insecurity situations in seven region of Ethiopia

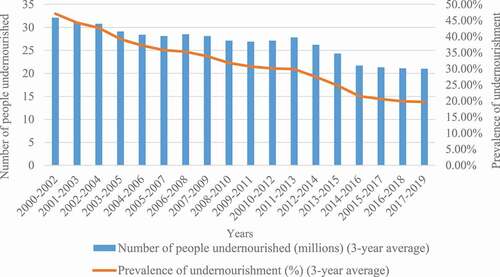

In addition, food and nutrition insecurity of vulnerable households is caused by several factors in Ethiopia. It is a result of interconnected capacity of recurrent drought, conflict prevalence, poor infrastructure, backward agriculture, and population pressure. This implies that political instability, low usage of sanitation services, low basic drinking water services, HIV, and TB infections are an important contributing factor for high prevalence of undernourishment. The trend of prevalence of undernourishment and number of people undernourished in Ethiopia between 2000 and 2019 is displayed in . According to FAO three years average percentage estimation of prevalence of undernourishment between years 2000–2019, the prevalence of undernourishment of Ethiopia fell gradually from 47.1% in first three years average (2000–2002) to 19.7% in the last three years average (2017–2019). This shows that the prevalence of undernourishment of Ethiopia had slightly falling from 2000 to 2019. In the same manner, number of people undernourished slightly declining from 32.1million in first three years average (2000–2002) to 28.1 million in the three years average (2005–2007). But, it is raised to 28.5 million in three years average (2006–2008). It is again declining to 28.1milloion in (2007–2009) to 26.9 million in (2009–2011). In 2010–2012, it is raised to 27.1 and continues to 27.8 in (2011–2013). Finally, it is declined continually from 26.2 million in (2012–2014) to 21 million in (20,017–2019) by almost the same rate with that of prevalence of undernourishment ().

The summary statistics showed that the average prevalence of undernourishment of Ethiopia from 2000 to 2019 was 28.6% with the lowest prevalence of 21.5% in 2017–2019 and the highest prevalence of 47.1% in 2000–2002. Similarly, the summary statistics showed that the average number of people undernourished in Ethiopia from 2000 to 2019 was 24.04 million with the lowest number of people undernourished 21 million in 2017–2019 and the highest number of people undernourished 32.1 million in 2000–2002 ().

7. Effects of livelihood strategies on food security status of rural households

According to Demissie (Citation2013) framing is the main livelihood strategy in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, at a national, regional, and household level, the focus of the policy is to increase agricultural productivity and farm income to attain food self-sufficiency. However, considerable resources have been spent on agricultural research and extension to mitigate food shortage in the country, research and extension activities have not been done enough about business expansion on the issues identified with non-farm or off-activities. In Ethiopia, many farmers are living with a very small plot of land, which couldn’t allow them to drive adequate livelihood outcomes from agriculture. Different livelihood strategies are engaged in by the households’ in-country to improve their livelihoods. This implies expanding livelihood strategies at present is a common phenomenon in Ethiopia. Although agriculture remains the main source of income and employment, rural non-farm income is gaining importance in most rural areas of developing countries including Ethiopia (Haggblade et al., Citation2010).

According to Martin and Lorenzen (Citation2016) the reasons for livelihood diversification are diverse, extending from an attractive choice for accumulation purposes to suffer induced insurance strategy brought on by crises. Non-farm income-generating activities give a significant wellspring of essential work in the rural areas of most developing countries’, and it is assumed that as a farm size because of population pressure becomes smaller, the level of non-farm income increases (Hilson, Citation2016). According to Rigg (2006), Lohmann and Liefner (Citation2009), Cinner et al. (Citation2010), Simtowe et al. (Citation2016), and Martin and Lorenzen (Citation2016) non-farm activities can assume an essential job in diminishing powerlessness to neediness by giving families a type of protection against the risks of farming and reducing reliance on natural resources. As depicted by FAO (Citation2012) regardless of its commitment to the livelihood of the society, the increasing population growth in developing countries, including Ethiopia constrained households to develop and make their living on the small size of land.

Though enhanced agricultural productivity is essential to achieve pro-poor growth through agriculture, poor rural households also depend on a range of non-farm economic activities as part of their livelihood strategies. Livelihood strategies pursued by rural households are at the heart of examining their food security (Oni et al., Citation2012). In Ethiopia, for a long time, undiversified livelihood options and complete dependency on agricultural production are the main problems that exacerbate food insecurity in the rural areas. Therefore, livelihood diversification for a country like Ethiopia is the finest decision that leads to livelihood outcomes consisting of improved food security, increment in income, reduced vulnerability to shocks, and sustainable use of natural resource base. However, the limited available empirical evidence indicates that there is a wide difference between results concerning the share of on-farm and off-farm income in total household income in Ethiopia. Yishak et al. (Citation2014), found that majority of the farm households (57%) engaged in other livelihood strategies besides agriculture. As some studies outlined, off-farm activities are mostly pursued by poor food-insecure households due to land shortage to produce adequate food for consumption. Increasing the number of livelihoods means engaged in by a household, their income level will increase with a consequent tendency towards food security. It is therefore worthy to note that livelihood diversified households are more income stable and food secured than the reverse households.

Various studies indicated that diversified sources of income and food security status have a positive relationship by increasing their total monthly income earning (Agbola et al., Citation2008; Zerai & Gebreegziabher, Citation2011a). Besides, the nature of livelihood strategy has been shown an influence on household food insecurity (Akinboade & Adeyefa, Citation2017; Fekadu & Mequanent, Citation2010). According to Ellis and Freeman (Citation2004) and Simtowe et al. (Citation2016), diversification must be of the approaches that households utilize to ensure a minimum level of income for improving destitution and food security status at the national level and farmers or households’ level. The fact that households engage in different types of activities as livelihood strategies demonstrate that households are trying their best to diversify their portfolios of income rather than depending on food aid alone. Therefore, understanding the food security status of households as an outcome of livelihood strategies is crucial to i mprove the response mechanisms related to food security and livelihood improvement (Yishak et al., Citation2014). indicates the summary of previoues emperical studies which were conducted in Ethiopia.

Table 6. Summary of previous studies on the determinants of food security in Ethiopia

8. Conclusions and recommendations

In Ethiopia, as in many other African countries, there is a pressing need to improve household food security. Food insecurity in Ethiopia derives directly from dependence on undiversified livelihood which is based on low-input and low-output rain-fed agriculture. However, non-farm livelihood diversification strategies play a key role in the food security improvement of households in Ethiopia. Currently, efforts to achieve food security will remain the primary concern of governments and households mainly, those people in lower-income or vulnerable groups in the country through non-farm livelihood diversification strategies. Hence, a review on determinants of livelihood diversification strategies and food security of the rural households in the country context is vital because it will deliver evidence that would enable to promote and undertake effective actions by local and national governments, NGOs, and rural household heads to improve the rural food security situations in the country. In this review, the results obtained from several studies defined different socioeconomic characteristics of the households that significantly influence the level of livelihood diversifications and food security situations, and presented the nexus between livelihood diversifications and food security. Several factors were found to be significantly associated with household livelihood diversification strategies and food security based on the findings of this review.

According to the documents that this review examined, livelihood diversification through non-agricultural income sources has significant impacts on the improvements of rural households’ food security situations. Because the majority of the rural households (57%) engaged in non-farm livelihood strategies. Therefore, this review concluded and recommended in the following way based on various findings of the review.

According to the review, the age of the household head affected the level of rural household livelihood diversification negatively and significantly. This implies that the older the age of household head and the lower the participation of the household heads on non-farm livelihood strategies. Therefore, the productive (young) aged members of the households should be encouraged to participate in non-farm and off-farm activities that help them to escape from the wider state of food insecurity. Large family size was found a positive and significant relationship with livelihood diversification strategies. Hence, households with large family sizes should participate more in non-farm and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies. Similarly, the effect of the educational level of the household heads was found a positive and significant effect on food security and rural livelihood diversification strategies. The possible reason was the more educated household heads possibly engaged in on-farm and off-farm livelihood strategies to improve their own food security status. Hence, the governments and private organizations need to work more and should support the expansion of both formal and informal education for rural households to improve the rural households’ food security situations in the country. This review showed that there was a significant negative relationship between the large land size of the rural household heads with non-farm and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies. The presence of a very small size of land and its negative and significant influence on food security suggests designing appropriate policies and strategies to inspire the engagement of rural household heads with a small size of the land on non-farm and off-farm livelihood diversification strategies to improve their food security status. This review also found a negative and significant relationship between the large livestock size of the household heads and livelihood diversification strategies. This implies that household heads who attained the required amount of cash from livestock did not want to involve in non-farm and off-farm activities for additional income. However, household heads with lower livestock holdings are attracted to diversify their livelihoods into non-farm and off-farm activities to improve their food security status. Therefore, household heads with lower livestock holdings should participate and diversify their income sources from non-agricultural activities to assure their food security status. A significant positive association between walking distance to the nearest market and level of livelihood diversifications calls concerned bodies to provide improved rural market access by rural households to engage in non-agricultural income-generating activities to increase their food security status.

As a strong significant relationship of annual cash income of the household heads with livelihood diversification strategies requests government actions to reduce financial problems through an emerging financial institution, creating credit access, and endorsing viable income-generating options. Because adequate income sources can overwhelm the financial constraints of the rural household heads to engage in alternative non-farm and off-farm activities to ensure their food security. Similarly, access to formal credit was found to have a positive and significant relationship with rural livelihood diversification strategies. Therefore, government and private banks and rural microfinance should be expanded in rural areas and would have roles to play in addressing rural food security through providing credit services with low interest. This review also found that there was a positive significant relationship between having the opportunity of receiving remittance and diversified livelihood sources on non-farm income activities. Therefore, the government should create awareness and provide adequate training for rural households to effectively utilize their remittances and increase their choice of livelihood strategy to improve their food security. This review also revealed that conflict between bordering ethnic communities within the same region results in temporary disruptions in the participation of rural households on non-farm and off-farm livelihood activities and causes the loss of lives and property. Therefore, the central and the local governments should do together and settle and avoid ethnic conflicts in the same region to encourage the engagement of rural household heads on non-farm livelihood diversification strategies to achieve the rural households’ food security in the country.

The overall conclusion of this review was that rural livelihood diversification is a positive undertaken and a remedy to enhance and realize the food security of the households especially in rural areas of the country. Therefore, the government should recognize and give due attention to non-farm livelihood diversification strategies as part of the national objectives to achieve food security in the country instead of solely sticking to the inadequate and drought-prone farm income alone; non-farm income has a significant contribution in moving households to food security. Collective efforts of all actors (governments, stakeholders, and rural households) are needed to work on the aforementioned significant determinant factors of rural livelihood diversification strategies to assure rural households’ food security situations in the country through implementing integrated policies, strategies, and programs that support non-farm livelihood diversification strategies in the most suitable ways of enabling this diversity.

Finally, further studies should be conducted on the area of rural livelihood diversification strategies and food security by considering detailed and accurate information on various factors (socioeconomic factors, climatic and weather, topography, natural disasters, and ecological conditions) which will affect the decisions of the households’ livelihood choice and food security situations. Furthermore, some variables which were found to be different compared with other studies should be further studied.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors write, read, and approved the manuscript equally.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andualem Kassegn

Andualem Kassegn is a full-time lecturer and researcher in the Department of Agricultural Economics, at Woldia University, Ethiopia. He has MSc degree in Agricultural Economics from Wollo University and a BA degree in Economics from Mekelle University. Currently, he has been teaching several courses for Agricultural Economics. His research areas of interest are lie in researching livelihood and income diversifications, impact evaluations, food security, and poverty matters etc.

Ebrahim Endris

Ebrahim Endris is a full-time lecturer and researcher in the Department of Agricultural Economics, at Woldia University, Ethiopia. He has MSc degree in Agricultural Economics from Haramaya University and BSc degree in Agricultural Economics from same University. Currently, he has been teaching several courses for Agricultural Economics. His research areas of interest are lie in conducting research on market analysis, value chain analysis, food security and poverty, livelihood, impact evaluation, entrepreneurship, business performance etc.

References

- Abdullah, Z., Shah, D., Ali, T., Ahmad, S., Din, I. U., W., & Ilyas, A. (2017). Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 18(2), 1-33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2017.05.003

- Abduselam, A. (2017). Food security situation in ethiopia: a review study. International Journal of Health Economics and Policy, 2 (3), 86–32.

- Abebaw, S., Janekarnkij, P., & Wangwacharakul, V. (2011). Dimensions of food insecurity and adoption of soil conservation technology in rural areas of gursum district, eastern ethiopia. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences,33(2), 308–318. http://www.rdi.ku.ac.th

- Abebe, G. (2017). Long-term climate data description in Ethiopia. Data in Brief, 14, 371–392. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.07.052

- ACAPS. (2018). Food Insecurity. https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/slides/files/20180226_acaps_thematic_report_food_insecurity_inal.pdf

- ACAPS. (2016). Drought and food insecurity. Anticipatory briefing note – 05 January 2016. Assessment capabilities project. http://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/acaps-anticipatory-briefing-noteethiopiadrought-and-food-insecurity.

- ACF. (2020) . Food security and livelihood assessments. A Practical Guide for Field Workers.

- Adem, M., Tadele, E., Mossie, H., Ayenalem, M., & Yildiz, F. (2018). Income diversification and food security situation in Ethiopia: A review study. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 4(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1513354

- Agbola, P. O. (2004). Economic Analysis of Household Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in Osun State, Nigeria. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria: Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Ibadan.

- Agbola, P. O., Awotide, D. O., Ikpi, A. E., Kormawa, P., Okoruwa, V. O., & Babalola, D. A. (2008). Effect of income diversification strategies on food insecurity status of farming households in africa: result of analysis from Nigeria. In Paper presented at the presentation at the 12th EAAE congress people, food and environments: global trends and european strategies. Belgium: Gent.

- Agidew, A.M. A., & Singh, K. N. (2018). Determinants of food insecurity in the rural farm households in south wollo zone of ethiopia: the case of the teleyayen sub watershed, 6(10), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-018-0106-4

- Akinboade, O. A., & Adeyefa, S. A. (2017). An analysis of variance of food security by its main determinants among the urban poor in the city of tshwane, South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 137, 61-82. Available at http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11205-017-1589-1.

- Albore, A. (2018). Review on role and challenges of agricultural extension service on farm productivity in Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 4(1), 93–100.