?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In the South Kivu province of the DR Congo, marshes are considered as favorable lands for various crop productions, and these improve food security and livelihood of thousands of households. We analyzed survey data collected from 148 farmers using a binary logit model and descriptive statistics in order to identify the potential threats to agricultural production, and the coping strategies used by farmers in marshlands. Results showed that 65% of respondents were female, and 76% of all farmers claimed perceiving threats to agricultural production in marshes. The perceived potential threats to agriculture included floods, pest infestation (millipede, fall armyworm), crop theft, and unsecure land-holding status as well as the decrease in soil fertility. Moreover, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has also led to the increase in prices of agricultural inputs (pesticides, seeds), and manure that has become increasingly rare and expensive due to the drastic reduction in livestock in that region weakened by several years of civil war and insecurity. In response, farmers were combining several adaptation strategies and these included drainage, mulching, manure application, and crop diversification used by farmers for, respectively, managing floods, maintaining soil fertility, and reducing crop failure. To cope with land scarcity, both female (75%) and male farmers (60%) claimed seeking for lands in highlands and renting extra plots in the same marshes or elsewhere. Despite the strategies implemented, there is still a need to strengthen farmers’ knowledge of flood and pesticide management and promote the integrated pest management practices for a sustainable use of marshlands.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study is one of the very few studies which have addressed farmers’ constraints and coping strategies in the South Kivu’s marshlands in the eastern DR Congo. In the study area, marshland agriculture remains a significant source of food and income-generating activity for many households. However, agriculture is facing climate change shocks and societal stressors, and farmers struggle to access productive resources and sufficient information to adapt and increase agricultural food production, manage pest infestations as well as intermittent floodings within marshes. Therefore, identifying farmers’ issues and the current adaptation strategies used is important to recommend appropriate options to overcome the challenges by focusing on farmers’ priorities.

1. Introduction

Global food security is one of the most pressing issues for humanity, and agricultural production is critical for achieving this (Godfray et al., Citation2010; Sundström et al., Citation2014). In Africa and especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, food insecurity is a multidimensional problem because this region faces several challenges such as rapid population growth, persistent economic inequality, droughts, youth unemployment, diseases and pest outbreaks (Niang et al., Citation2014; Kabirou, Citation2020). In addition, the ongoing pandemic COVID-19 and climate change threats are expected to severely affect smallholder farmers and this will result in reduced farmers’ income as well as in disruption of food supply (Ayanlade & Radeny, Citation2020;); Mushagalusa et al., Citation2021). In the DR Congo, food insecurity and poverty are due to multiple combined causes arising from war and armed conflicts, as detailed by Cox (Citation2011), Vlassenroot (Citation2005), and Tollens (Citation2003), to which today, we can add land degradation, climate change, disease and pest outbreaks (Bationo et al., Citation2015; Bele et al., Citation2014; Heri-Kazi & Bielders, Citation2020; Payne, Citation2010). In the South Kivu province of the DR Congo, agriculture remains the main employment and income-generating activity for many households. Agriculture strengthens farmers’ livelihoods and helps to supply the city of Bukavu with various agricultural food products in that region devastated by many years of civil war and political instability. To date, farmers are more inclined towards vegetable farming for its short production cycle, to access permanent diversified food, and incomes (Balasha & Nkulu, Citation2020; Shakanye et al., Citation2020), and marshlands are considered as promising lands for achieving this (Mushagalusa et al., Citation2021). Marshes have been recognized as valuable land area for food and fodder production because they have fertile soils as a result of regular sediment deposition during flood events (Verhoeven & Setter, Citation2010). They are important lands for poverty reduction and food security in many places where the growing population, in conjunction with efforts to increase food production reclaim more land for agriculture (McCartney et al., Citation2010; Verhoeven & Setter, Citation2010). They are also recognized as a source of water and important ecosystems for the conservation of biodiversity (Halls, Citation1997; Sutton-Grier & Sandifer, Citation2019), provide freshwater and green forage for livestock (Fynn et al., Citation2015; Morris & Reich, Citation2013). A recent survey conducted in Kabare shows that farmers drain, and maintain marshlands in order to grow a range of crops including vegetables, sweet potatoes, beans, taro and sugarcane (Mushagalusa et al., Citation2021). Rapid urbanization, self-consumption, good cash income and high demand in food commodities, particularly vegetables have been considered as drivers of and opportunity for farmers to intensify and diversify crop production (Bellon et al., Citation2020; Pepijn et al., Citation2018; Satterthwaite et al., Citation2010). However, in low income countries like the DR Congo, agriculture is facing many challenges including structural issues (lack of irrigation infrastructures, impassable roads) and societal stressors: land conflict, urbanization, labor shortage that generally affect local food systems (Béné, Citation2020). To these problems are added also other important global issues which include environmental degradation, climate change and diseases and pests of animals and plants (Sundström et al., Citation2014). In other parts of the world, it is the scarcity of resources such as land, water and the high prices of new agricultural technologies as well as the lack of training that hinder agricultural food production. In South Kivu and especially in the territory of Kabare, the Provincial Inspectorate of Agriculture, Fishery and Livestock (IPAPEL) has identified more than 78 marshes varying in size from 5 to 15 hectares where smallholder farmers grow a variety of crops: amaranth, cabbage, beans, eggplants, sugarcane, ect.(Inspection Agricole du Territoire de Kabare, Citation2019). However the challenges and threats that these farmers face are still underreported. In this study, the perception of threats to agriculture refers to a range of socioeconomic issues (land scarcity, unaffordable price of inputs, shortage of labor, lack of information, crop theft) and environmental factors (soil degradation, pest infestation, floods) which are believed by farmers to jeopardize farming activities and result in poor harvest. This study was conducted in order to (1) characterize marshland farmers ‘profile and their farming systems,(2) identify the significant threats to agricultural food production in the marshlands, and (3) explain why and how these threats and farmers ‘socioeconomic characteristics shape farmers’ attention and perception in order to search for coping strategies. The results of this study will provide a better understanding of the threats to agriculture in marshlands and the way farmers deal with them in order to direct future interventions and assistance towards these problems.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

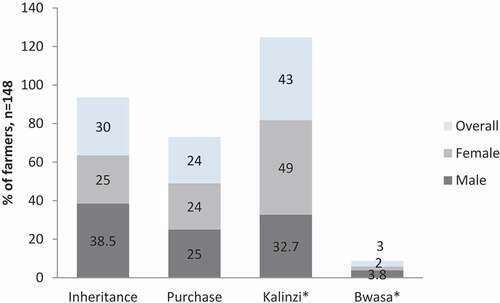

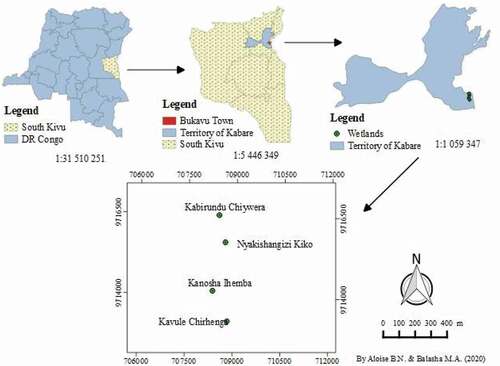

The study was conducted in four marshy sites: Kabirundu, Kanosha, Kavule and Kiko within the territory of Kabare, around the town of Bukavu, in the province of South Kivu eastern DR Congo (). In Kabare, the main sources of livelihood for households are livestock, crop production including vegetables and bananas, coffee, sugarcane, beans and sweet potatoes, often grown in mixed farming systems (Cox, Citation2011; Heri-Kazi & Bielders, Citation2020; Maass et al., Citation2012). In this territory as in the whole Bushi community, the customary land tenure law includes the Kalinzi, Bwigahire, Bwasa and Obuhashe (Kinghombe, Citation2003), but this customary logic is losing its authority because of the increasing competition due to high demand in land, which has introduced another form of accessing land called Bugule i.e. purchase (Ansoms et al., Citation2012; Overbeek & Tamás, Citation2018). In the marshlands investigated, Kalinzi and Bwasa were reported among many respondents (). Kalinzi is a land use right allocated by customary authorities or a landowner after the payment of rent, which may be a goat, a cow, or its monetary value depending on the arrangement of the two parts (Ansoms et al., Citation2012; Overbeek & Tamás, Citation2018). Bwasa is a rental contract which gives the borrower the right to use land for a short duration only for food crops (cassava, beans or vegetables) and the rental price is called Ntumulo, calculated a posteriori in proportion to the profits or harvests collected. Respondents, who used land under this contract, claimed working 8 hours (salongo) within landowners’farms once a week instead of cash.

Figure 1. Map of South Kivu (eastern DR Congo) showing the territory of Kabare and the marshlands investigated

The choice of these marshy sites was motivated by four reasons: first, the sites are large (± 10 hectares each) and exposed to climatic hazards, such as floods. Second, they provide a good part of vegetables and other food commodities consumed in Bukavu. Third, many women and young people work there for their financial autonomy, and finally, no study has so far reported the threats and the challenges farmers face there. The study area has a humid tropical climate characterized by a rainy season from September to May and a dry season from June to August. Heri-Kazi and Bielders (Citation2020) describe the region as one of the hotspots for soil erosion in the world, a phenomenon execrated by demographic pressure. Mathys and Vlassenroot (Citation2016), Ansoms et al. (Citation2012), and Vlassenroot (Citation2005) have reported several cases of land conflicts and land grabbing. Although excellent recommendations related to the resolution of land conflicts have been proposed to non-government organizations and to the DR Congo government (Leeuwen et al., Citation2020), their implementation is encountering structural obstacles in this country where judicial structures has been largely absent after almost two decades of armed conflict and insecurity, law and order have widely been replaced by the right of the strongest (Beck, Citation2012).

2.2. Data collection

Data were collected from marshland farmers through semi-structured interviews and field visits among 148 farmers chosen randomly within the four marshy sites (). These farmers were met on their fields during farming works from April to June 2020. A questionnaire was prepared in French and translated into Mashi, a local language to collect information. Information collected included farmers ‘socio-economic characteristics (gender, age, access to land, contact with extension agents, farm and household size, education, farming objectives), farming systems and practices, and perception of threats to agricultural production. To identify the perceived threats to agriculture among farmers, the time frame considered was 2018–2020. The choice of this short period is explained by our desire to minimize the forgetting bias from farmers. Second, considering this period, we were confident that farmers can still remember the events of the last growing season as well as the current challenges and threats to crops during the ongoing season (period of survey). In addition, field observations helped understand the level of the damage associated with floods and pests whereas farmers’ stories related to the perceived threats increased an understanding of farmers’ vulnerability. We focused our attention on the threats such as the decrease of soil fertility, flooding, and pest infestation, crop theft, and land issues (4) The coping strategies were identified by asking binary questions (1 = yes, 0 = no) on the use of pesticides, organic matter, cleaning up rivers, drainage, crop diversification, mulching, shifting sowing dates, farm inspection, and field inspection as described in our previous paper on climate change (Mushagalusa et al., Citation2021).

2.3. Data analysis

In order to effectively handle and analyze diverse data collected from the field and farmers, we encoded them into Microsoft Excel and crosschecked to clean errors and IBM SPSS Statistical Package Version 21.0 was used to perform data analysis. A chi-square test (χ2) was used to investigate significant differences between male and female farmers regarding their socioeconomic characteristics (gender representation, farming objectives, landholding, use of external labor and education, contact with extension agents). The t -test was also used to assess mean differences (age, experience, household and farm size and amount of money paid to rent a plot) between female and male. Furthermore, a binary logit model was performed to identify the perceived threats to agriculture in marshlands and highlight that these are significant for farmers. The reduced form model that was estimated is as follows:

Where Yi is the dependent variable (Perception of threats). It takes the value 1 if the farmer perceives a threat and fears to lose crops, 0 otherwise. X is the matrix of the variables likely to explain the variation of Y. β0 is the Y intercept; whereas β1- βn is a set of coefficients to be estimated and X1-Xn are explanatory variables hypothesized. presents variables used in the binary logistic regression and effects expected. The choice of the binary logit model is due to its capacity to identify and predict significantly farmers’ perception of the factors threatening their livelihoods (Kabore et al., Citation2019; Kisauzi et al., Citation2012). The choice of these variables is explained by the fact that they include socioeconomic and environmental factors which can have an impact on the perception of farmers.

Table 1. Description of variables used in binary logit model

This study considered α < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-economic characteristics of respondents

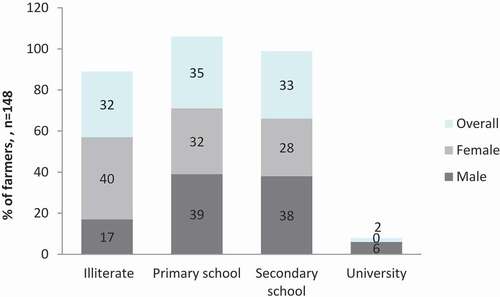

presents the descriptive statistics for the socioeconomic characteristics and gendered differences among marshland farmers surveyed. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the overall gender representation of the sample (p < 0.05). Females represented 65% and males 35% of the sample with a mean age of 43 years. Significant gendered difference was also noticed in education background (ꭓ2 = 12 .316; p = 0.006) where female farmers were likely disadvantaged because 40% were illiterate and only 28% attended the high school ().

Table 2. Farmers’ basic characteristics

While many farmers had a primary school level of education (35%), only 2% claimed having a university level. Results indicated that only a few farmers (14%) had contact with an agronomist or a field agent of a non-governmental organization. Respondents had a good experience in marshland farming, on average 11 years, and worked in their farms more than 6 hours per day.

The average farmland area of the surveyed farmers was 289 m2, and there was no significant difference between male (269 m2) and female (300 m2) farmers regarding the surface cultivated (p > 0.05).

In the study area, farmers access land in four ways: inheritance, purchase, Kalinzi and Bwasa (). The majority of farmers (54%) have owned land through inheritance and purchase, and these two means are believed to provide a secure land ownership. However, many women farmers clarified that the land they cultivated belonged to in-laws or donated by their biological families. This implies that many women do not have land ownership rights in the Bushi community. Although landowning through inheritance was the most popular among male farmers, landless farmers paid a rent averaging 22 US dollars per year for a cropland surface of 289 m2 ().

ͯ*Both are rental practices to access land, see details in the description of the study area section.

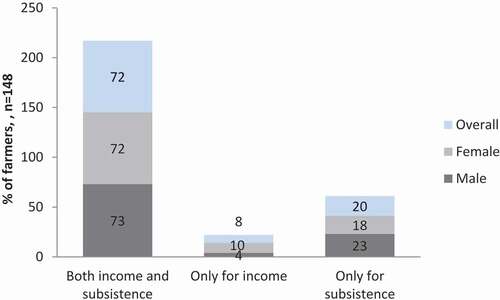

A large majority of farmers (72%) claimed farming for both subsistence and income purposes (). There is a large proportion of male (23%) and female (18%) farming for only subsistence whereas 8% of whole farmers said farming is only for income. However, the chi-square test did not show significant difference between male and female regarding the farming goals (ꭓ2 = 3.225, p = 0.199).

Although all farmers mainly depended on the family workforce, the majority of respondents reported hiring casual agricultural labor for specific duties such as drainage, plowing and clearing field. Many farmers also claimed the labor becomes scarce when children go back to school as explained the respont NO 23 . '' My children weed, water the crops and help to harvest during their vaccations. When they go back to school, I work alone in the farm''. The chi-square test indicates that there was not a significant difference between male and female farmers regarding the use of casual labor (). The results show that 75% of male and 80% of the female farmers hired casual labor, and this represents 78% for the entire sample.

Table 3. Gender and use of casual agricultural labor in marshlands, n = 148

3.2. Farming system and crop management practices

The farming system, planting periods as well as the pest management and soil fertility practices are given in . Marshland farmers’ growing systems are characterized by a mixture of crops (82%), mainly vegetables such as cabbage, amaranth, squash, taro and eggplant were observed in most of the fields. Farmers reported that crops such as taro and sweet potatoes were interesting since they required fewer nutrients and maintenance to thrive. The planting period started between March and April (40%), and more than half of the respondents started their farming works by May and June. This period coincides with the reduction of water after floods. Manure application was the most popular practice to fertilize lands (98%) and mulching helped to control weeds and maintain soil fertility. Most of the farmers interviewed were concerned about the losses due to Millipedes infestation in all crops, and these pests were reported by 88% of the respondents, while worms of Spodoptera frugiperda and Plutella xylostella were increasing worries among maize and cabbage growers. This is because these pests also attacked crops in marshes and highlands, and their broad dispersal capacity and crop damages they cause worry farmers. Respondent No 11 and 132 expressed their fears,“millipedes are going to lead people to a serious famine because they attack all crops, and no pesticide works. if they migrate in highlands where maize is already attacked by fall armyworm, then we will become miserable.” Meanwhile, rats and moles were perceived as dangerous pests among eggplant, sweet potato and cassava growers, but these rodents were easy to control with traps, catch and rodenticides. A farmer who met in Kabirundu marshland explained,“all pests cause important losses, but 3 moles within a sweet potato or cassava field are more dangerous than a cow grazing in there. If these pests are not controlled on time, you can harvest what they have decided to leave you”.

Table 4. Marshland farmers ‘practices and crop management techniques

3.3. Identification of the threats to agricultural food production in marshlands

The large part of farmers (76%) claimed perceiving threats to agriculture in marshlands, and significant differences were observed among sites investigated as shown in . These threats included floods, theft of crops, scarcity of land and increase in price of agricultural inputs such as seeds, manure and pesticides. The chi-square test indicated that both male and female farmers had the same perception regarding the reported threats. However, the highest proportion of farmers affected by these threats was recorded in Kiko (82%) and Kavule (91%) respectively. illustrates how crops are affected with floods and millipedes in marshlands.

Figure 5. A flooded farm of taro and corn in Kiko (left) and taro damaged by millipedes in Kabirundu (right)

Table 5. Gender and perception of threats to agricultural food production in marshlands

presents the results from the binary logit model for the entire sample of 148 marshland farmers surveyed. Results show that the socioeconomic factors that affect farmers ‘perception of threats to crops included household size, land-holding status, farm size, increase in price of agricultural inputs, permanent farm inspection, and theft of crops. On the other hand, the environmental factors such as floods, pest infestation (millipede, fall armyworm) influenced significantly farmers’ perception of the threat to agriculture in marshes. Results showed that flooding and pest infestation increased, respectively, 57 and 10 times farmers’ fears and perception of crop failure, resulting in decreased yields and food shortage. The positive correlations between gender, farm experience, time worked on farms per day, shortage of labor and the perception were also recorded even if these variables were not significant.

Table 6. Socio-economic and environmental factors determining farmers’ perception of threats to agricultural food production in marshlands

Number of observations: 148, −2log- likelihood 81.101; Pseudo R-square(Nagelkerke R2 = 64.1%), Note: n = 148; Sig = significance, B: unstandardized regression weight; Exp(B): exponentiation of the B coefficient, S.E: Standard error; Overall percentage of correctly predicted model = 89.2%; **, * significant level at 5 & 10%.

3.4. Farmers’ coping strategies and challenges

Male and female farmers‘coping strategies to withstand risks associated with the earlier cited threats, are shown in . Both male (100%) and female farmers (98%) drained and cleaned water canals before plowing and planting. Drainage works were recognized as being hard, costly (2-5USD per day for an occasional worker) and dangerous because they were done manually with spades, machetes and hoes, and many farmers claimed facing venomous beasts including snacks and cutting objects. Pesticides such as cypermethrin 5%EC, profenofos 40%+cypermethrin 4%EC, abemectin +acetamiprid 5% EC and fungicides (mancozeb, metalaxyl) were sprayed by both male and female farmers with poor equipment, and this can be risky (health problem) for farmers and threatening natural enemies of crop pest as well as other beneficial entomofauna such as bees. Although many farmers complained about the decline in soil fertility, some farmers resorted to slash-and-burn to open fields, kill millipedes and manage dead grass. This practice can lead to the loss of organic matter and soil microorganisms. Due to the high price of agricultural inputs (seed, pesticide and manure), a high proportion of male (71%) and female (70%) farmers reported selecting and conserving seeds from various crops grown (amaranth, eggplants, squash). Some farmers reported purchasing inputs collectively and made arrangement with inputs sellers in order to pay with interests after selling harvests. In the investigated marshlands, chemical fertilizers were still unknown among many farmers. Manure was used by almost all female farmers (99%) as well as male farmers (98%). The use of manure as the main fertilizer among farmers has motivated more than 50% of the respondents to invest in small livestock (rabbit, Guinea pig, and pork) in order to have more manure. Respondents No3, 67 and 141 explained in these words:” in this area, no one uses chemical fertilizers; we have been told that they exacerbate pest infestation and kill lands. Manure is the most important input in vegetable production, that is why its demand among farmers is increasing and prices are attractive for livestock farmers. I collect more than 3 tons per year from pork, goat and Ginea pigs to grow these crops.” Farmers who recorded a sickness case within households were affected and late to achieve agricultural works, but in worse situations, these farmers had to rent out their fields to fellow farmers for money or share harvest according to their arrangement. The decrease in labor pushed both male (88%) and female (83%) farmers interviewed to involve children in farming operations such as transport of manure, weeding and watering crops and in some cases, children were also used to watch crops and connect farmers to harvest buyers. Crop theft was found to be a significant threat to agricultural food production in the marshlands investigated. To deal with this problem, almost farmers (96% of female) inspected regularly their fields whereas 50% of the male farmers harvested early, and 33% among female farmers had to change crop type in order to discourage crop thieves. Crop theft exacerbated farmers ‘vulnerability, led to food shortage within victim households. Respondents NO 65 and 101 were, respectively, crop theft victims and shared with us their common story; “I lost a whole field of maize from which I was expecting between 50 and 75 USD to pay children school fees, thieves did not leave anything, the next day, I also rushed to harvest immature taro because I was scared to lose everything. I decided not to grow maize anymore and switched to sweet potato and sugarcane”.

Table 7. Gender and main responses to perceived threats to agricultural food production in marshlands

4. Discussion

This section discusses the roles of marshlands and significant threats to agriculture there and examines some of the coping strategies used by farmers to withstand risks to their livelihoods. Diversified crops observed in marshlands of Kabare were designed to meet farmers’ self-consumption and market objectives. Verhoeven and Setter (Citation2010); McCartney et al. (Citation2010) argued that marshlands will play a key role for food production in many places where increasing food demand will oblige farmers to search for more croplands. The proportion of females was high among marshland farmers surveyed and they claimed that vegetable production increased their financial autonomy and vegetable consumption within their households. That is normal because women in Africa and especially in DR Congo are considered as a keystone of the agricultural sector and play a vital role in food production, food distribution, and food utilization—the three components of food security (Balasha & Nkulu, Citation2020; Habtezion, Citation2012; Okonya & Kroschel, Citation2014).

However, agriculture in the marshes faces several socioeconomic and environmental challenges. One of the greatest socioeconomic challenges is the access to land and having ownership rights. Studies conducted in many African countries show that the lack of land ownership rights prevents farmers from engaging in more sustainable practices like agroforestry (Balasha & Nkulu, Citation2020; Mushagalusa & Kesonga, Citation2019) as well as good soil fertility management practices (Cheikh et al., Citation2019a). In Pakistan, Akram et al. (Citation2019) found that landowners involved in agribusiness are more likely to invest in measures to improve soil and increase productivity than land tenants. Other socioeconomic challenges, such as the increase in prices of agricultural inputs and theft of crops are believed to prevent farmers from adopting agricultural technologies. This situation is critical for farming communities in this time of COVID-19 where input markets are affected and trade reduced, and this result in disruption of local food systems and socioeconomic crises (Ayanlade & Radeny, Citation2020; Béné, Citation2020). In the study areas where farmers believe that COVID-19 has worsened crop theft, this situation affects negativelly farmers' decision to invest in agriculture and adopt agricultural technologies. The same situation has been reported in other countries. For example, in Kenya, Dyer (Citation2020) found that the risk of crop theft is perceived to be significantly stronger for farmers who just adopt and cultivate new valuable crops compared to those who grow traditional crops.

Agriculture is also facing environmental challenges such as climate change threats. Findings showed that flooding was considered 57 times more likely than other factors to be the main perceived threat in marshland agriculture (). This is because floods which follow heavy rains destroyed crops on which farmers based their financial and food hopes. In DR Congo, and especially in the province of South Kivu, threat to agriculture cause significant concern among communities because agriculture is still a strategic livelihood and often the main source of income for many households (Chaussé et al., Citation2012; Cox, Citation2011; Mushagalusa & Kesonga, Citation2019; Shakanye et al., Citation2020).

Unfortunately, agriculture evolves in a context of climate change characterized by extreme events which undermines farmers’ hopes and exacerbates their already precarious conditions (Camilla et al., Citation2019; Harvey et al., Citation2014). In sub-Saharan Africa, crop and livestock production losses due to floods were estimated to be up to 9% averaging 1 331 million USD in the last decade(FAO, Citation2016). In Myanmar, for example, 400,000 ha of land was flooded, resulting in severe damage to cultivated crops and food insecurity (FAO, Ministry of Agriculture & Irrigation; Ministry of Livestock et al., Citation2015). Recently, USAID (Citation2020) reported that heavy rains and subsequent flooding have destroyed homes and agricultural fields in South Kivu, adversely affecting at least 90,500 people. Many scholars have argued that such situations will worsen household farmers’ vulnerability (Camilla et al., Citation2019; Harvey et al., Citation2014; Morton, Citation2007) because of the low capacity to adapt to sudden changes (Niang et al., Citation2014; Shimeles et al., Citation2018). The situation is likely critical in the DR Congo because its government has been criticized for not being able to allocate enough resources to support the agricultural sector and farmers (Tollens, Citation2015; Tshomba et al., Citation2020). Farmers have developed strategies to cope with floods, and these strategies included cleaning water canals and regular drainage and adjusting sowing period. Cleaning and drainage works restore canal hydraulic capacity to evacuate water during the rainy season and supply water during the dry season (Anras et al., Citation2007). Drainage makes flooded land usable, and this can help reduce the risk of pollution, flooding stress and loss of crops (Anras et al., Citation2007; Tewari & Mishra, Citation2018) while shifting sowing dates and change in crop type are considered as minimizing risk and adaptive strategy among farmers facing extreme events such as drought or floods due to climate change (Asayehegn et al., Citation2017; Ngigi et al., Citation2017). However, drainage works were perceived fastidious for farmers, and to overcome such challenges, marshland farmers decided to organize these works collectively. This is important because farmers are expected to get encouragement, inspiration and motivation from other fellow farmers when they work in groups (Makate & Mango, Citation2017).Despite farmers’ efforts to manage and maintain marshlands for agricultural food production, pest outbreaks, such as millipede and fall armyworm infestation, were also perceived as apotential threat to crops. on one hand, millipedes destroy seeds; devastate sweet potatoes, cassava and taro fields and cause enormous losses, due to the poor quality of the harvests. Asimilar observation was done in Senegal and Uganda where millipedes attacked various crops including sweet potato and cereal grains (Ebregt, Citation2007; Matthews, Citation2018). Even if we did not quantify the damages and the economic impacts of these pests; nevertheless, studies conducted in Uganda clarified that millipedes were responsible for the loss of up to 84% of the sweet potato cuttings if the crop was planted early in the first rainy season (Ebregt etal., Citation2005), and also attacked all crops used as part of the sweet potato cropping systems (Ebregt, Citation2007; Ebregt etal., Citation2005). On the other hand, fall armyworm was perceived as a devastating pest. A recent study by Cokola et al (Citation2021) shows that fall armyworm constitutes a risk and a potential threat to local food security because of its broad dispersal capacity and its polyphagous character. Mechanical control (killing pests by hand) and insecticides were used to control these pests. Pesticides used by marshland farmers were insecticides and fungicides. Since pesticides were misused in the study area (farmers did not wear protection equipment, and used poor spraying materials, such as brooms and basins), we think that pesticide applications cannot be asustainable way to control pests in marshlands regarding their high price for poor farmers (5–23 USD per cropping season) and the potential risks these farmers are exposed to. Furthermore, millipedes hide underground, under litter and fed mainly on soft roots of crops whereas contact pesticides sprayed could not reach the target. Asimilar challenge and limit in pesticide use was reported among cabbage growers facing Agrotis Ipsilon in Lubumbashi (Balasha & Nsele, Citation2019c) Several studies show that unsafe handling and poor use of pesticides can contribute to acute pesticide poisoning, not only affecting farmers who buy and use these products (Balasha etal., Citation2019; Lekei etal., Citation2014) but also their application affects biodiversity and kills beneficial insects such as bees and natural enemies of pests (Balasha & Nsele, Citation2019c; Bommarco etal., Citation2011). If pesticides sprayed by marshland farmers showed their limits to control millipedes, there is much to learn from Senegal, where farmers are implanting some sustainable practices based on the trapping of millipedes (see Matthews, Citation2018). Results also showed that the decline of land fertility was considered as asignificant issue for farmers (p < 0.05), yet marshlands are recognized to have fertile soils as aresult of regular sediment deposition during flood events (Verhoeven & Setter, Citation2010). Surprisingly, the declining of land fertility was negatively correlated with farmers’ perception of potential threat to agricultural production in marshlands. Some reasons can explain this: First, many farmers link fertility to the yield or productivity, forgetting that other factors like pests and disease attack, poor farming practices, and sudden changes in weather may affect crop output, yet the land is still fertile. That is why Munyuli etal. (Citation2017) believe that there is ahuge confusion between damages (attacks) due to pests, diseases and environmental stress (rains, soil nutrient deficiency, or flood stress) among farmers. Second, while discussing with farmers, they tended to generalize the highland fertility issues to the whole territory of Kabare including marshlands: “our lands are tired, we do not harvest enough even in highlands, we keep farming because we have no alternative,” third, we assume that during floods, marshlands lose an important quantity of organic matter and mulches, which may have an impact on marshlands soil. However, this reason is not consistent with Verhoeven and Setter (Citation2010) who believe that marshland fertility is associated with regular sediment deposition during flood events. For Heri-Kazi and Bielders (Citation2020) whose study focused on highlands, nutrient depletion, and loss of organic matter are due to soil erosion. To restore and maintain soil fertility, most farmers used manure and mulching. Bationo etal. (Citation2015) and Lalljee (Citation2013) reported that the mulching associated with organic matter is agreat and cheap mitigation agricultural technology against land degradation in the wake of climate change. They improve the soil properties, model temperatures, favor good crop growth and prevent erosion (Rajan etal., Citation2017). Although organic matter is essential in agriculture, the problem of its availability in quantity and quality as well as its increasing price are among the main challenges farmers are facing today. Since manure is collected far from the marshland farms, the cost of transport may be important, even if farmers take advantage of children to transport and apply manure. This observation is in agreement with Balasha and Nkulu (Citation2020) and Minengu etal. (Citation2018) who noticed that vegetable producers struggle to transport manure because their farming sites are distant from manure collection points. While farmers used grass for mulching, we observed that some among them burned grass (slash-and-burn), and this practice was also observed by Ntamwira etal. (Citation2014) among farmers in the study area. The latter authors argued that burning grass when preparing land for sowing is acommon practice among local farmers and this result in the loss of 40kg of nitrogen and 10kg of sulfur per hectare each farming season. Such apractice destroys soil microorganisms, leads to changes in soil properties and exacerbates land degradation (Hauser & Norgrove, Citation2013; Kukla etal., Citation2019). To enable sustainable agriculture in marshlands, farmers are expected to use environmental-friendly practices and strengthen their knowledge ad hoc.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed to examine the potential threats to marshland agriculture and the coping strategies used by farmers to withstand risk associated with the perceived threats. Findings suggest that diversified farming systems observed within marshlands of Kabare remain a source of income, risk reduction strategy and mean to strengthen farmers’ livelihoods, despite the risks due to changes in weather and the recrudescence of bioagressors. Marshland farmers cultivated small-sized lands/plots to grow various crops including vegetables, beans, and taro for self-consumption and for marketing. Results from the binary logit model showed that household size, land-holding status, farm size, and the increase in price of agricultural inputs, permanent farm inspection, and crop theft were the significant socioeconomic factors affecting farmers’ perception of threats to agriculture. On the other hand, two environmental factors: floods and pest infestation (millipede, fall armyworm) influenced significantly farmers’ perception of threat to agriculture in marshes. In response, farmers combined various coping strategies to deal with the perceived threats. These strategies included drainage and cleaning water canals to deal with floods, crop diversification and application of pesticides to minimize crop failure and pest damage, permanent farm inspection and crop-type change to discourage crop thieves. However, slash-and-burn (to open field and reduce dead grass) and frequent pesticide sprayings used control millipedes as well as fall armyworm were not sustainable, and these practices are accepted to expose farmers to health risks and kill beneficial entomofauna. Knowing that conventional pesticides do not provide a solution for future sustainable agriculture, the integrated pest management based on trapping of millipedes is a sustainable approach farmers can try (see Matthews, Citation2018). We learn from these results that gathering all the factors of production in agriculture does not always guarantee good harvests because agriculture depends on local meteorology and other environmental factors, on which smallholder farmers have not controlled. In this regard, we recommend empowering farmers by strengthening their knowledge of flood management and improve knowledge of pesticides use (issues, dosage, re-entry period, safety) as well as of integrated pest management. Implementing a policy that improves farmers’ ability to access productive resources and information. Policymakers can also put in place a social safety net program to help farmers cope with income losses resulting from climate change shocks and crop theft.

Competing Interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Cihruza Volonté; Assumani Buhendwa; Akilimali Innocent; Cubaka Nicanor, Bismwa Benoit, and Murhula Benjamin for their participation in data collection. Many thanks to Dr Iva Pesa and the two anonymous reviewers for the valuable comments which enabled us to improve the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mushagalusa Balasha Arsene

Arsene Mushagalusa Balasha is an Agricultural Economist trained at the University of Lubumbashi,DR Congo and holds a Master's degree in the Integrated Production and Preservation of Natural Resources in Urban and Peri-urban Areas from the University of Liege, Campus of Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, Belgium, 2017. He is currently a PhD candidate and researcher at the Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Lubumbashi. His research focuses on smallholder farmers’ access to productive resources and crop management in the wake of climate change.

Jules Nkulu Mwine Fyama (PhD) is an Agricultural Economist and a full-time professor at the faculty of Agronomy, and leads the Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Lubumbashi, DR Congo. His research interest areas include rural development, agribusiness, food security, and small-scale farming.

References

- Akram, W., Ayesha, M., & Ayesha, M. (2019). Does land tenure systems affect sustainable agricultural development? Sustainability, 11(14), 3925. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143925

- Anras, L., Des Touches, H., & Collection. (2007). Curage des canaux et fossés d’eau douce en Marais littoraux “Marais Mode d’emploi” (F. Des Marais Atlantiques Ed.; pp. 76).

- Ansoms, A., Claessens, K., & Mudinga, E. (2012). L’accaparement des terres par des élites en territoire de Kalehe, RDC. L’Afrique des grands lacs, Annuaire 2011-2012, 206–20. L'Harmattan. http://hdl.handle.net/2078/1179784

- Asayehegn, K., Temple, L., Sanchez, B., & Iglesias, A. (2017). Perception of climate change and farm level adaptation choices in central Kenya. Cahiers Agricultures, 26(2), 25003. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1051/cagri/2017007

- Ayanlade, A., & Radeny, M. (2020). COVID-19 and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of lockdown during agricultural planting seasons. Npj Science of Food, 4(13), 1-6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-020-00073-0

- Balasha, M., & Nkulu, J. (2020). Déterminants d’adoption des techniques de production et protection intégrées pour un maraîchage durable à Lubumbashi, République démocratique du Congo. Cahiers Agricultures, 29, 13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1051/cagri/2020012

- Balasha, M., & Nsele, K. (2019). Pesticide use practices by Chinese cabbage growers in suburban environment of Lubumbashi (DR Congo): Main pests, costs and risks. Journal of Applied Economics and Policy Analysis, 2(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12691/jaaepa-2-1-8

- Balasha, M., Seveno, J., Kesonga, N., Kasanda, M., Nkulu, J., & Son, D. (2019). Vegetable farmers’ knowledge and safety practices towards pesticides: Results from field observation in southeastern DR Congo. Current Research in Agricultural Sciences, 6(2), 169–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.68.2019.62.169.179

- Bationo, A., Thomas, F., Ken, G., Valérie, K., Rodney, L., Abdoulaye, M., Mapfumo, P., Oduor, G., Dannie, R., Vanlauwe, B., Wairegi, L., Zingore, S. 2015. In Manuel de gestion intégrée de la fertilité des sols. T. Fairhurst, eds.. Consortium Africain pour la Santé des Sols, (pp. 169). Nairobi.

- Beck, J. (2012). Contested land in the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2(2), 66p. Ruhr University Bochum. http://www.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/ifhv/documents/workingpapers/wp2_2.pdf

- Bele, M., Sonwa,, & Tiani, A. (2014). Local Communities vulnerability to climate change and adaptation strategies in Bukavu in DR Congo. Journal of Environment & Development, 23(3), 331–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496514536395

- Bellon, M., Bekele, H., Azzarri, C., & Caracciolo, F. (2020). To diversify or not to diversify, that is the question. Pursuing agricultural development for smallholder farmers in marginal areas of Ghana. World Development, 125(104682), 104682. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104682

- Béné, C. (2020). Resilience of local food systems and links to food security – A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Security, 12(4), 805–822. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1

- Bommarco, R., Miranda, F., Bylund, H., & Björkman, C. (2011). Insecticides suppress natural enemies and increase pest damage in cabbage. Journal of Economic Entomology, 104(3), 782–791. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1603/ec10444

- Camilla, I., Harvey, C., Ruth, M., Raffaele, V., & Rodriguez, C. (2019). Vulnerability of smallholder farmers to climate change in Central America and Mexico: Current knowledge and research gaps. Climate and Development, 11(3), 264–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2018.1442796

- Chaussé, J., Kembola, T., & Ngonde, R. (2012). L’agriculture: Pierre angulaire de l’économie de la RDC. In J. Herderschee, D. Mukoko Samba, & M. Tshimenga Tshibangu (Eds.), Résilience d’un géant africain: Accélérer la Croissance et Promouvoir l’Emploi en RDC, II: Etudes sectorielles (pp. 97). Medias Paul.

- Cheikh, F., Bouly, S., Dramane, C., & Omar, D. S. (2019a). Structure du maraichage périurbaine et dégradation des ressources (sols et eau) dans la zone de Boutoute à Ziguinchor (Sénégal). Journal D’économie, De Management, d’Environnement Et De Droit, 2(3), 49–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48398/IMIST.PRSM/jemed-v2i3.18456

- Civava, M. R., Malice, M., & Baudoin, J. P. (2012). Amélioration des agrosystèmes intégrant le haricot commun (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) au Sud-Kivu montagneux. Ed. In Harmattan (pp. 69–92).

- Cokola, M., Mugumaarhahama, Y., Grégoire, N., Muzee, K., Basengere, B., Zirhumana, M., Munene, A., Kanyenga, L., & Frédéric, F. (2021). Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in South Kivu, DR Congo: Understanding How Season and Environmental Conditions Influence Field Scale Infestations. Neotropical Entomology (Vol. 50, pp. 145–155). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-020-00833–3

- Cox, P. (2011). Farming the battlefield: The meanings of war, cattle and soil in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Disasters, 35(5). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01257.x

- Dyer, J. (2020). The Fruits and Vegetables of Crime: Protection from Theft and Agricultural Development, Job Market Paper, University of Toronto, 83p.

- Ebregt, E. (2007). Are millipedes a pest in low-input crop production in north-eastern Uganda? Farmers’ perception and experimentation, PhD thesis Wageningen University, 168 p.

- Ebregt, E., Struik, P., Odongo, B., & Abidin, P. (2005). Pest damage in sweet potato, groundnut and maize in north-eastern Uganda with special reference to damage by millipedes (Diplopoda).. In NJAS (pp. 1–53).

- FAO (2016). Damage and losses from climate-related disasters in agricultural sectors: Assessment report, www.fao.org/climate-change

- FAO, Ministry of Agriculture & Irrigation; Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries & Rural Development; and WFP. (2015). Agriculture and livelihood flood impact assessment in Myanmar, Assessment final report, 60p.

- Fynn, R., Dhliwayo, M.-H. M., & Scholte, P. (2015). African wetlands and their seasonal use by wild and domestic herbivores. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 23(4), 559–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-015-9430-6

- Godfray, H., Beddington, R., Crute, R., Lawrence, H., David, L., Muir, F., Pretty, J., Sherman, R., Sandy, M., Thomas, C. T. (2010). Food Security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science, 327(5967), 812–818. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185383

- Habtezion, S. (2012). Gender, agriculture and food security, in gendered and climate change Capacity development series ( pp. 30). United Nations Development Programme.

- Halls, A. J. (ed.). (1997). Wetlands, biodiversity and the ramsar convention: The role of the convention on wetlands in the conservation and wise use of biodiversity. Ramsar Convention Bureau.

- Harvey, C., Rakotobe, Z., Rao, N., Dave, R., Razafimahatratra, H., Rabarijohn, R., Rajaofara, H., & MacKinnon, J. (2014). Extreme vulnerability of smallholder farmers to agricultural risks and climate change in Madagascar. Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society B, 339(369), 2–22. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0089

- Hauser, S., & Norgrove, L. (2013) Slash-and-Burn Agriculture, Effects of. In S. A. Levin (Ed..), Encyclopedia of biodiversity (Vol. 6, 551–562, second). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384719-5.00125-8

- Heri-Kazi, B., & Bielders, L. (2020). Dégradation des terres cultivées au Sud-Kivu, R.D. Congo: Perceptions paysannes et caractéristiques des exploitations agricoles. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ, 2(2), 99–116. doi: https://doi.org/10.25518/1780-4507.18544

- Inspection Agricole du Territoire de Kabare. (2019). Marais récensés dans le territoire de Kabare. Rapport annuel 2019

- Kabirou, D. (2020). Understanding Africa’s Food Security Challenges. I ntechOpen, 1-17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.91773.

- Kabore, P., Bruno, N., Ouoba, P., Kiema, A., Some, L., & Ouedraogo, A. (2019). Perceptions du changement climatique, impacts environnementaux et stratégies endogènes d’adaptation par les producteurs du Centre-nord du Burkina Faso. VertigO - La Revue Électronique En Sciences De L’environnement, 19(1), 28p. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4000/vertigo.24637

- Kinghombe, C. (2003). L’organisation foncière du bushi et ses conséquences négatives sur l’aménagement rural du Kivu montagneux. In Revue de la chaire dynamique sociale,1 (pp. 2–9). Université de Kinshasa.

- Kisauzi, T., Mangheni, M., Seguya, H., & Bashaasha, B. (2012). Gender dimensions of farmers’ perceptions and knowledge on climate change in Teso Sub-Region, eastern Uganda. African Crop Science Journal, 20(20), 275–286.

- Kukla, J., Whitfeld, T., Cajthaml, T., Baldrian, P., Veselá‐Šimáčková, H., Vojtěch N., Jan F. (2019). The effect of traditional slash‐and‐burn agriculture on soil organic matter, nutrient content, and microbiota in tropical ecosystems of Papua New Guinea. Land Degradation & Development, 30(2), 166–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3203

- Lalljee, B. (2013). Mulching as a mitigation agricultural technology against land degradation in the wake of climate change. International Soil and Water Conservation Research, 11, 68–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-6339(15)30032-0

- Leeuwen, M., Mathys, G., Lotje, D. V., & Gemma, V. (2020). From resolving land disputes to agrarian justice -dealing with the structural crisis of plantation agriculture in eastern DR Congo. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(7), 1-26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1824179

- Lekei, E., Ngowi, A., & Leslie, L. (2014). Pesticide retailers’ knowledge and handling practices in selected towns of Tanzania,”. Environmental Heath, 13(79), 2–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-016-0203-3

- Maass, L., Katunga, M., Wanjiku, L., Anja, G., & Peters, M. (2012). Challenges and opportunities for smallholder livestock production in post-conflict South Kivu, eastern DR Congo. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 44,1221–1232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-011-0061-5

- Makate, C., & Mango, N. (2017). Diversity amongst farm households and achievements from multi‑stakeholder innovation platform approach: Lessons from Balaka Malawi. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(1), 37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0115-7

- Martin, G., Moraine, M., Ryschawy, J., Magne, M., Masayasu, A., Sarthou Jean, P. Michel, D., Olivier, T. (2016). Crop–livestock integration beyond the farm level: A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 36(3), 53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0390-x

- Mathys, G., & Vlassenroot, K. (2016). It’s not all about the land’: Land disputes and conflict in the eastern Congo, rift valley institute psrp briefing paper.

- Matthews, J. (2018). L’anthropologie comme outil de facilitation du développement agricole. Echo, 139, 2–11.

- McCartney, M., Rebelo, L.-M., Senaratna Sellamuttu, S., & De Silva, S. (2010). Wetlands, agriculture and poverty reduction. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute. 39p. (IWMI Research Report N° 137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5337/2010.230.

- Minengu, J. D. D., Ikonso, M., & Mawikiya, M. (2018). Agriculture familiale dans les zones péri-urbaines de Kinshasa: Analyse, enjeux et perspectives (synthèse bibliographique. Revue Africaine d’Environnement Et d’Agriculture, 1(1), 60–69. http://rafea-congo.com/admin/pdfFile/RAFEA-Article-Minengu-et-al-2018-ok.pdf

- Morris, K., & Reich, P. (2013). Understanding the relationship between livestock grazing and wetland condition. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 252. Department of Environment and Primary Industry.

- Morton, J. (2007). The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104,50, 19680–19685. United States.

- Munyuli, T., Kana, C., Rubabura, D., Mitima, K., Yajuamungu, K., Nabintu, T., Kizungu, M., Remy T. (2017). Farmers’ perceptions, believes, knowledge and management practices of potato pests in South-Kivu Province, eastern of Democratic Republic of Congo. Open Agriculture, 2(1), 362–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2017-0040

- Mushagalusa, A., & Kesonga, N. (2019). Evaluation de la performance économique des exploitations de chou de Chine (Brassica chinensis L.) en maraîchage à Lubumbashi en République Démocratique du Congo. Rev. Afr. d’Envi. Et d’Agriculture, 2(1), 11–19. http://www.rafea-congo.com/pages/lecture1.php?id_article=20

- Mushagalusa, B., Kitsali, K., Murhula, B., Lebon, H., Aloise, B., Cihruza, V., Asumani B., Akilimali I., Bisimwa B., Cubaka N. (2021). Perception et stratégies d’adaptation aux incertitudes climatiques par les exploitants agricoles des zones marécageuses au Sud-Kivu. VertigO - la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement

- Ngigi, M., Mueller, U., & Regina, B. (2017). Gender Differences in Climate Change Adaptation Strategies and Participation in Group-based Approaches: An Intra-household Analysis from rural Kenya. Ecological Economics, 138(1), 99–108. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.03.019

- Niang, I., Ruppel, C., Abdrabo, M., Essel, A., Lennard, C., Padgham, J., & Urquhart, P. (2014). Africa. In V. Barros, et al. (eds.), Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: regional aspects. contribution of working group ii to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1199–1265). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Ntamwira, J., Pypers, P., Van Asten, P., Vanlauwe, B., Ruhigwa, B., Lepoint, P., Monde, T., Kamira M. & Bloome G. (2014). Effect of banana leaf pruning on banana and legume yield under intercropping in farmers’ fields in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Horticulture and Forestry, 6(9), 72–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5897/JHF2014.0360

- Okonya, J., & Kroschel, J. (2014). Gender differences in access and use of selected productive resources among sweet potato farmers in Uganda. Agriculture & Food Security, 3(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/2048-7010-3-1

- Overbeek, F., & Tamás, P. (2018). Autochthony and insecure land tenure: The spatiality of ethicized hybridity in the periphery of post-conflict Bukavu, DRC. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 12(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2018.1459084

- Payne, W. (2010). Farming Systems and Food Security in Sub- Saharan Africa. In R. Lal & B. A. Stewart (Eds.), Food security and soil quality (pp. 406). CRC Press.

- Pepijn, S., Simmons, B., & Wopereisc, M. (2018). Tapping the economic and nutritional power of vegetables. Global Food Security, 16, 36–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.09.005

- Rajan, P., Manjet, P., & Solanke, K. (2017). Organic mulching: A water saving technique to increase the production of fruit and vegetables. Current Agricultural Research Journal, 5(3), 571–588. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CARJ.5.3.17

- Ryschawy, J., Choisis, J. P., Choisis, A. J., & Gibon, A. (2012). Mixed crop-livestock systems: An economic and environmental-friendly way of farming? Animal, 6(10), 1722–1730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731112000675

- Satterthwaite, D., McGranahan, G., & Cecilia, T. (2010). Urbanization and its implications for food and farming. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010 365, 2809–2820. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0136

- Shakanye, N., Vumilia, K., Ahoton, E., Saidou, A., Bello, D., Mugumaarhahama, Y., Kazamwali, M., & Mushagalusa, G. (2020). Typology and Prospects for the Improvement of Market Gardening Systems in South-Kivu, Eastern DR Congo. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 12(6), 136–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v12n6p136

- Shimeles, A., Verdier-Chouchane, C., & Boly, A. (2018). Understanding the challenges of the agricultural sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. In A. Shimeles et al. (eds..), Building a Resilient and Sustainable Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa (p. 302). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76222-71

- Sundström, F., Albihn, A., Boqvist, S., Karl, L., Håkan, M., Carin, M., Karin, N., Vågsholm, I., Yuen, J. & Ulf, M. (2014). Future threats to agricultural food production posed by environmental degradation, climate change, and animal and plant diseases – A risk analysis in three economic and climate settings. Food Security, 6(2), 201–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-014-0331-y

- Sutton-Grier, E., & Sandifer, A. (2019). Conservation of wetlands and other coastal ecosystems: A commentary on their value to protect biodiversity, reduce disaster impacts, and promote human health and well-being. Wetlands, 39(6), 1295–1302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1039-0

- Tewari, S., & Mishra, A. (2018). Flooding stress in plants and approaches to overcome. In Plant Metabolites and Regulation Under Environmental Stress, Chapter 18 in, 357–366. Academic press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812689-9.00018-2.

- Tollens, E. (2003). L’état actuel de la sécurité alimentaire en R.D. Congo: Diagnostic et perspectives.” Working Paper, n° 77, Département d’Economie Agricole et de l’Environnement, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 76p.

- Tollens, E. (2015). Les parcs agro-industriels et l’agriculture familiale: Les défis du secteur agricole en RDC. In Conjonctures congolaises (pp. 148–158). Conjonctures congolaises.

- Tshomba, K., Nkulu, M., Kalambaie, M., & Lebailly, P. (2020). Analysis of the effects of subsidy programs on the performance of cereal crops (Maize Zea mays L. and Rice Oriza sp.) in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia. Revue Africaine d’Environnement Et d’Agriculture, 2(2), 39–48.

- USAID (2020). Democratic Republic of the Congo - complex emergency fact sheet #3, fiscal year(fy).https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/democratic-republic-congo-complex-emergency-fact-sheet-3-fiscal-7

- Verhoeven, J., & Setter, L. (2010). Agricultural use of wetlands: Opportunities and limitations. Annals of Botany, 105(1), 155–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcp172

- Vlassenroot, K. (2005). Households land use strategies in a protracted crisis context: Land tenure, conflict and food security in eastern DRC.Conflict Research Group University of Ghent, 40p.