?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Understanding the management and breeding practices of indigenous livestock species kept under the traditional management system is very important to design and implement appropriate breeding and management interventions. This study described the goat management and breeding practices in East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. A semi-structured questionnaire was prepared and administered to 202 randomly selected respondents and group discussions were held to triangulate the information. Qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed using the descriptive, and GLM procedures, respectively. In the area, crop-livestock farming was common (100%). The overall average goat flock size was 11.52 ± 9.09. The matured male-to-female goat ratio was 1:3.6. Goats were mainly raised for income (Index = 0.436). Hillside browsing was the first rated feed source in wet (I = 0.390) and dry (I = 0.394) seasons. Rivers were the major water sources in the dry (93.1%) and wet (92.1%) seasons. Most (98.5%) of the respondents reported that they practice buck castration. Most farmers reported the selection of breeding does (98.5%) and bucks (99%). Farmers rated body size as the first selection criteria to select breeding does (Index = 0.341) and bucks (Index = 0.344). About 84.7% of the respondents had their breeding buck(s). However, a natural uncontrolled mating system (86.6%) was common. The overall mean age at first mating of male and female goats were 7.01 ± 1.55 and 6.69 ± 1.64 months, respectively. The overall mean age at first kidding, kidding interval, litter size at birth, and productive life of does were 13.02 ± 2.18 months, 6.47 ± 0.69 months, 2.15 ± 0.38 kids, and 6.93 ± 2.38 years, respectively. The uncontrolled breeding management and low male-to-female ratio in the flock would lead to inbreeding. Thus, designing and implementing an appropriate goat breeding strategy is worthwhile.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In Ethiopia, goats are key assets for rural livelihoods with lots of advantages over large ruminants. Goats play substantial economic and cultural roles in the Ethiopian highlands, mixed crop-livestock, and lowland pastoral production systems. Keeping goats is convenient as financial assetsto generate immediate cash requirements used to meet basic needs including, food, medicine, and school fees. Besides, goats have an important role in the social life of many Ethiopian people being used as gifts, dowry, in religious rituals, and rites of passage. In Ethiopia, goat production is constrained by many biological, environmental, and economic factors, and is subjected to low productivity. Knowledge of the goat management system, breeding practice, and compatibility of the breed genotype with the farmers’ breeding objectives are needed to enhance goat productivity. This research gives insight to readers into the management systems and breeding practices of indigenous goats in Ethiopia.

1. Introduction

In Ethiopia, above 80% of the population gets their sustenance from agriculture, accounting for nearly 34.9% of the national GDP and 83.9% of total exports (NBE, Citation2018). Livestock is an integral part of agriculture, accounting for about 45% of agricultural production. To support livelihoods, nearly 70% of the population keeps livestock owing to small herds made of three cattle, three goats/sheep, and a few chickens (FOASTAT, Citation2019). Besides, providing meat, milk, cash, draft power, hauling services, insurance, and social capital to the population (Wodajo et al., Citation2020), the Ethiopian livestock contributes about 10% to the total export earnings, of which 69% is gained from live animals (cattle and small ruminant) exports (FOASTAT, Citation2019). Nationally, sheep and goats account for about 90% of the live animal meat and 92% of skin and hide export trade value (Wodajo et al., Citation2020).

The Ethiopian livestock herd comprises 52.5 million goats, 42.9 million sheep, 70 million cattle, 57 million poultry, 8.1 million camels, 2.1 million horses, 10.8 million donkeys, 0.38 million mules, and 6.99 million hives (CSA, Citation2021). The CSA (Citation2021) report also showed that from the national goat population, the indigenous, hybrid, and exotic breeds covered about 99.9, 0.05, and 0.05 million heads, respectively, indicating that the indigenous goat breeds have the highest share. These livestock populations are distributed across various agro-ecological zones and managed under mixed crop-livestock, pastoral and agro-pastoral, landless urban and per-urban, and commercial dairy and feedlot production systems (FOASTAT, Citation2019). Despite the presence of a diversified goat genetic pool, huge goat population in the country, and its tremendous economic contribution for rural households, the assistance of the sub-sector to the goat keeping households income and the national economy is relatively low (Haile et al., Citation2019) due to technical, economic, and institutional constraints (FOASTAT, Citation2019; Zewdie & Welday, Citation2015).

Genetic improvement is among the options employed for increasing goat productivity. But, it needs identification and description of the goat breeds, management systems, and compatibility of the breeds’ genotype with the farmers’ breeding objectives. Moreover, research outputs concerning breeding practices of the indigenous goats in Ethiopia are minimal (Aseged et al., Citation2021). To design a breeding program and to improve and conserve the indigenous goat types in their natural production environment, identification of the goat breeds, description of the management systems, knowing the breeding practice and farmers goat breeding objectives at a particular production environment are the first information to be addressed (FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), Citation2011). Thus, this research aimed to describe the management system and breeding practices of the indigenous goats in East Gojjam Zone of the Amhara Region, Ethiopia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study areas

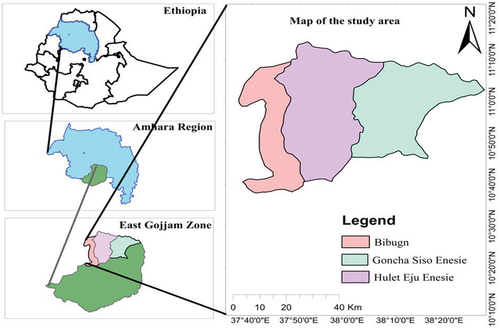

The study was conducted in three adjacent districts (Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts) purposively selected from East Gojjam Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia (Figure ). The study districts were selected based on accessibility, the potential of indigenous goats, the inclusiveness of all agro-ecologies, farmers’ participation in goat production, and the economic contribution of goats in the household income in the areas (Districts’ Agriculture development Offices (DADO), Citation2019). Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts lie between the coordinate points of 11° 00ʹN and 12° 24ʹN latitude and 34° 70ʹE and 37° 35ʹE longitude, 10° 27’ 36” to 11° 53’ 52” N latitudes and 37° 12’ 56” to 38° 43’ 45”E longitudes, and 10° 45’ 00” to 11° 10’ 00” N latitude and 37° 45’ 69” to 38° 10’ 00” E longitudes, respectively. The altitude of the districts ranges from 1480–4160, 1000–3400, and 1290–4036 for Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, respectively. The study districts have an average annual rainfall of 1500, 1000, and 1100 mm in Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, respectively. The average annual temperature in Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts are 16°C, 15°C, and 18.5°C, respectively. In all the study districts, lowland (the altitude is below 180 m.a.s.l.), midland (the altitude rages between 1800 and 2400 m.a.s.l.), and highland (the altitude is above 2400 m.a.s.l.) agro-ecologies are found. But, Bibugn district has “Wurch” agro-ecology, which is characterized by mountain zone elevated above 3800 m a.s.l. (Districts’ Agriculture development Offices (DADO), Citation2019).

2.2. Sampling methods and sample size determination

A purposive multi-stage sampling technique was used to identify the study sites. Based on the information collected from preliminary field surveys and discussions with districts agriculture and rural development bureau experts, Peasant Associations (PA) development agents, and farmers living in the respective PA hierarchically, sample districts, PAss, and households from each PA were selected. Accordingly, three districts and nine PAs (three from each district) were purposively selected considering the selection criteria mentioned in the study area description section. A systematic random sampling technique was used to identify households for the questionnaire interview. First, with the involvement of PAs’ development agents and community leaders, households who have goats and participate in goat production were identified from the selected PAs. Then starting from the first household, sample households were chosen using a fixed interval determined by dividing the number of households identified from each PA by the number of required households until the desired sample size was obtained. Households were taken proportionally from each PA after the total sample size was determined using Yemane’s (Yamane, Citation1967) sample size determination formula indicated hereunder (Table ).

Table 1. Summary of the total number of sample households and PAs by districts

The formula used to determine sampled households for questionnaire interview was:

Where;

n = required Sample size

N = population size

e = error margin (e = 0.07, was considered)

2.3. Data collection and analysis

A semi-structured questionnaire interview was used to generate data on the production system, goat breeding objectives, and breeding practices (FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), Citation2012). To collect both qualitative and quantitative data, a total of 202 households were interviewed (Table ). Qualitative data on household socio-economic characteristics (family size, age, and educational status), socio-economic and cultural importance of goats, management practices of goats comprising herding, housing, feeding and watering, selection and breeding aspects, available livestock feed resource and utilization methods, and data on other related issues were collected. In addition, quantitative data on economically important reproductive traits of indigenous goats including, age at puberty, age at first kidding, kidding interval, litter size, and average productive life of doses were collected. Focused group discussions with farmers were held in each district to triangulate information collected through questionnaires.

The data were checked for completeness and consistency and coded. All quantitative data were entered into the Microsoft office excel worksheet, 2019, whereas all coded qualitative data were entered and analyzed using SPSS, version 22 software application. Before the main data analysis, screening of outliers was employed. Chi-square test (χ2- test), and F-test at (P < 0.05) were used to test the significance level. Quantitative data were analyzed using the general linear model (GLM) procedures of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS, 9.0; SAS, Citation2003) software application. ANOVA checked the significance of the effect of the independent variables on dependent variables, and if significance is declared, means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range mean separation method. Indexes were calculated for ranked variables (purposes of goat keeping, selection criteria of breeding flock, potential feed resources in wet and dry seasons, and common goat disease in the areas) to rank according to the producers’ perception using the formula: Index = Σ of [(n* the number of households ranked first) + (n-1 * the number of households ranked second) + … + (1* the number of households ranked nth)] given for particular qualitative variables divided by Σ of [(n*sum of households ranked first) + (n-1* sum of households ranked second) + … + (1* sum of households ranked nth)] for all qualitative variables considered (Kosgey, Citation2004).

2.4. Ethical clearance

The semi-structured questionnaire and focused group discussion (FGD) checklists utilized to collect the data were reviewed for ethical clearance and approved by Dilla University Agricultural Productivity, Food Security, and Livelihood Research Team. Besides, participant households and members of FGD were informed about the objective of the study to obtain their agreement.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Description of the production system

3.1.1. General household characteristics

Gender, age categories, educational status, and marital status of the interviewed households in the study areas are presented in Table . The proportion of male household heads in Bibugn (96.5%), Goncha Siso Enesie (98.7%), and Hulet Eju Enesie (95.5%) were higher than female household heads in all the study districts. This result slightly agreed with the report of Gatew (Citation2014) and Tesema (Citation2019), who noted that most (93.88%) and (93%) of the respondents were males in Bati area, and in Amhara Sayint, Habru, and Raya Kobo districts, respectively. The smallest proportion of female household heads in all the study districts may be due to males’ dominant role in undertaking outdoor goat management-related activities resulting in the highest probability of getting males with their animals. The majority of the interviewed household heads from all the studied areas were found in an age category of 41–50 years (48%), followed by 31–40 (25.7%) and 51–60 (20.8%) age categories.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the visited goat keeping households in east Gojjam zone

The sample households’ average family size in the study districts were 6.28 ± 1.64 persons, 5.56 ± 1.76 persons, and 5.81 ± 1.74 persons in Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, respectively (Table ). The average family size in Bibugn district was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than that in Goncha Siso Enesie district. The overall average family size (5.85 ± 1.74 persons) in the present study was higher than the average household size in Ethiopia, which is 4.6 persons (3.5 persons in urban and 4.9 people in rural areas; CSA, Citation2016). However, the overall average family size in the present study was almost similar to the average family size in Raya Kobo (5.93 ± 1.59 persons) district (Tesema, Citation2019). In contrast, the overall average family size in the present study was lower than the average family size in Habru district (7.44 ± 4.15 persons; Tesema, Citation2019) and in Borena (8.07 ± 0.26 persons) and Siti (7.68 ± 0.26 persons) areas (Gatew, Citation2014). The variation in the average family size of the households from different areas may be due to the differences in the application of family planning.

Table 3. Family size, and land and livestock holdings of the households in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

The majority (67.8%) of the interviewed households were illiterate, whereas the remaining 22.3%, 7.9%, and 2% of the respondents could read and write and attended primary school and religious school, respectively. The result of the present study agreed with reports of different scholars (Gatew, Citation2014; Tesfahun, Citation2013; Zergaw, Citation2014), who stated that the majority of goat keepers in their respective study areas were illiterate. In contrast, the higher proportion of illiteracy in the present study did not agree with Tesema (Citation2019), who reported that illiterate goat keepers were lower than the educated in Amhara Sayint, Habru, and Raya Kobo districts. The higher proportion of illiteracy in the area covered by this particular study may harm the application of intervention options to improve goat productivity in the area. Regarding the marital status of the interviewed households, most (98%) of the household heads were married.

3.1.2. Land and livestock holdings of the respondents

The average grazing land, cropping land, total landholding, livestock holding, and species composition owned by the respondents in all the study districts are presented in Table . The average total landholdings, including private grazing land of the sampled households in Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, were 1.35 ± 0.59, 1.45 ± 0.49, and 1.21 ± 0.63 hectares, respectively. The average total landholding in Goncha Siso Enesie district was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than the average total landholding in Bibugn and Hulet Eju Enesie districts. Similarly, the average grazing land in Goncha Siso Enesie (0.13 ± 0.16 hectare) district was significantly (P < 0.001) higher than the average grazing landholdings in Bibugn (0.09 ± 0.13 hectare) and Hulet Eju Enesie (0.03 ± 0.09 hectare) districts. However, there was no significant difference between the study districts in terms of cropping landholdings. The result of the present study revealed that from the overall average total hectares of land (1.34 ± 0.57) owned by sampled households in all the study areas, a large part was covered by cropping land (1.25 ± 0.52) than grazing land (0.09 ± 0.13), which agreed with the report of Tesfahun (Citation2013). The use of a large hectare of land for crop production in the present study may be due to the application of crop-livestock farming as the dominant agricultural activity; hence, greater priority is given to crop production than livestock rearing for the livelihood of households in the area.

The study districts’ livestock holding and species composition comprise cattle, goats, sheep, equine, chicken, and beehives. From the total livestock species owned by the respondents in all the study districts, ruminant animals (goats, cattle, and sheep) were covered the highest species composition while chicken and beehives were next to them. Equines took the smallest share of total livestock composition in all the study districts. There was a significant (P < 0.05) difference in the visited households’ livestock holding patterns among the studied districts. Respondents from Hulet Eju Enesie and Goncha Siso Enesie had a more significant average number of goats, cattle, and equine than respondents from Bibugn; whereas, households from Bibugn district had a more significant average number of sheep and beehives than respondents from Hulet Eju Enesie and Goncha Siso Enesie districts.

3.1.3. Farming and non-farming activities

A mixed crop-livestock production system is the dominant agriculture in the rural highlands of Ethiopia; however, one sub-sector has competed with the other in the use of land resources (Mekuria et al., Citation2020). Similarly, in the area, all respondents are engaged in mixed crop-livestock farming activities. There were no households engaged in only crop cultivation or livestock rearing (Table ). The main crops cultivated are maize, teff, and barely in Bibugn, and maize, teff, wheat, peppercorn, and peanut/groundnut in Goncha Siso Enesie and Hulet Eju Enesie districts. Whereas goats, cattle, sheep, poultry, and equines are the dominant livestock species reared in the area. In the area, livestock (cattle and equines) are the primary labour sources for crop production, and crop by-products are essential livestock feed resources. Besides crop-livestock farming, some (7.4%) respondents from all study districts practiced non-farm activities to generate additional household income (Table ). Daily labourer, making handcraft, and miniature trading in the local market are among the non-farm activities implemented by the respondents.

Table 4. The sources of foundation goats, farming, and non-farming activities in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.4. Experience in goat keeping

The overall average goat farming experience (mean ± SD) of the study districts was 13.33 ± 7.91 years, which was lower than the Zergaw (Citation2014), who noted the average goat farming experience in Meta-Robi and Konso districts was 19.42 ± 10.96 years. The average goat keeping experience of goat keepers in Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts were 15.37 ± 9.82, 12.58 ± 6.81, and 12.48 ± 7.05 years, respectively. There was no significant (P > 0.05) difference in goat farming experience between goat keepers from all the study districts.

The average starting goat numbers of the respondents were 2.28 ± 1.46, 2.53 ± 1.33, and 2.66 ± 1.34 for Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, respectively. There was no significant (P > 0.05) difference among the study districts regarding starting goat numbers. Purchase from the local market, gifted by families, and obtained as loans were the commonly reported sources of the first goat(s; Table ). However, the majority of goat keepers (93%) in Bibugn, (83.3%) in Goncha Siso Enesie, and (80.6%) in Hulet Eju Enesie obtained the first goat(s) through purchasing from the local market (Table ), which may be an opportunity to introduce goats with new genetic makeup from the distant market into the areas.

3.1.5. Purpose of goat keeping

The ranks of the purpose of goat keeping in the area are presented in Table . Income sources through live animal sale, for the production of household meat, as a means of saving, skin and manure sources, and socio-cultural reasons (as a symbol of wealth) have been ranked as 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th purposes goat keeping, respectively. However, the index values for each production purpose among the study districts were different. In the visited areas, income source(marketing) was rated as the 1st purpose of goat keeping with index values 0.424, 0.455, and 0.425 for Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, respectively. In comparison, household meat production and a means of saving were the second and third goat production purposes. The present result is similar to the reports of different scholars in Ethiopia (Alemu, Citation2015; Gatew, Citation2014; Tesema, Citation2019), who mentioned a source of cash income as the primary purpose of goat keeping. On the other hand, the present result disagreed with Tesfahun (Citation2013) results’, who reported that the primary purpose of goat keeping in Benatsemay and Hamer districts was to identify pastoralists’ wealth status. The primary purpose of goat keeping was for the source of cash income in the present study may be due to the application of mixed crop-livestock farming in the area, and as a result, farmers used goats to sell at the time of cash needed for the purchase of agricultural inputs, children’s school fee, buying cloth and other household needs.

Table 5. The purpose of keeping goats (ranks) in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.6. Goat flock structure

Knowledge of the flock structure of livestock species in a particular production environment is a prerequisite for maintaining the required male-to-female ratio for effective breeding management. Goat flock structure by their sex and age categories in the study area are presented in Table . From 2,336 goats reared by 202 households, female goats excluding suckling female kids and male goats excluding suckling male kids accounted for 53.9% and 29.9%, respectively. The remaining 15.8% was covered by suckling female and male kids. Percentages of male goats above weaning age (9.8%) for weaned males and (11.3%) for mature males >1 year were lower than the percentage of weaned females (12.8%) and adult females (41.1%). This result was similar to Asefa et al. (Citation2015) report, who documented the percentage of male goats in the flock was 32.42%, and it decreases as their age increases in Bale Zone, Oromia region. The lower portion of males in the flock may be due to male goats being primarily selected for marketing by the farmers when cash was needed and slaughtered during festivals and ceremonial occasions, while females were allowed to breed in the flock till the end of their production life. In this particular study, the ratio of male goats (weaned males and matured males>1 year) and matured male goats with their female counterparts were 1:2.6 and 1:3.6, respectively. This result was similar to the findings of Tesfahun (Citation2013) (1:3) and Zergaw (Citation2014) (1:3) reported for matured males to matured females ratio in the lowlands of South Omo Zone and Konso and Meta-Robi districts, respectively. But, higher male-to-female ratios were reported for Bale Zone (1:8.4; Asefa et al., Citation2015) and pastorals (1:11.23) in Aba’ala district of the Afar region (Gebre et al., Citation2020). The low male-to-female ratio recorded in the present study may aggravate the inbreeding level that resulted in the loss of genetic diversity and hybrid-vigor within the flock.

Table 6. Goat flock structure in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.7. Labour sources and herding

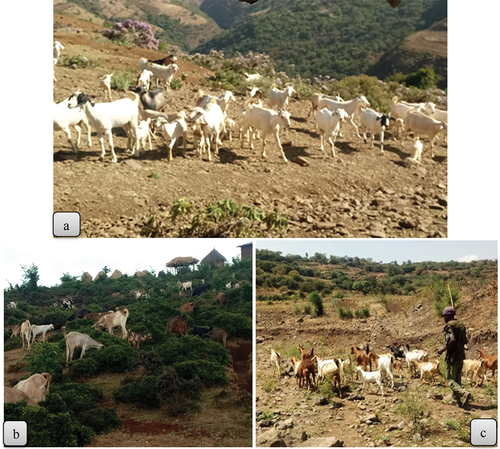

Labour sources for goat herding practice, ways of goat herding, and herding goats for grazing purposes are presented in Table . The majority of the respondents (90.1%) reported that family members are their sources of labour to herd their goats. The remaining (9.9%) respondents herd their goats together with their neighbours in round sequences one after the other. All age and sex groups of goats, except suckling kids less than a month, were herded together in the area. Other researchers from different parts of Ethiopia reported similar goat herding practices (Gatew, Citation2014; Tesfahun, Citation2013; Zergaw, Citation2014). Only 39.1% of respondents herd their goats separately from other livestock species (Figure ).

Figure 2. Goat herding practices in Bibugn district (a), Goncha Siso Enesie (b) and Hulet Eju Enesie (c) districts.

Table 7. Labour source and goat herding practice in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.8. Feed resources and feeding management

The quantity and quality of feeds and the nutritional status of goats determine their reproductive and productive potential since it hinders the full expression of the genetic potential of an individual (Joshi et al., Citation2018). Zewdie and Welday (Citation2015), noted that the feed resource bases for goat production in Ethiopia are natural grazing lands and crop residues that vary highly with seasons. The index values of hillside browsing for Bibugn, Goncha Siso Enesie, and Hulet Eju Enesie districts in the dry season were 0.398, 0.385, and 0.403, while the corresponding index values in the wet season were 0.383, 0.391, and 0.388, respectively. It was the primary feed resource for goats in both dry and wet seasons in the area (Table ). The present result differed from Tesfahun (Citation2013) and Alemu (Citation2015) findings, who reported natural pasture was the primary feed resource for goats in the dry and wet seasons. Communal grazing lands and crop-aftermath were the 2nd and 3rd rated feed resources in Bibugn and Hulet Eju Enesie districts, while in Goncha Siso Enesie district, crop-aftermath was the 2nd rated feed resource in the dry season. In comparison, communal and private grazing lands were the 2nd and 3rd ranked feed resources in all the study districts during the wet season. This result is similar to Asefa et al. (Citation2015) finding, who reported natural pasture was the primary feed resource during the wet season in Bale Zone. Although the index values were lower, goat keepers in the area used non-conventional feeds (brewery by-products and kitchen leftovers) and agricultural by-products (especially by-products from peanut/ground net crop) as goats’ feed.

Table 8. The ranks of feed resources in wet and dry seasons in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

Most (86.1%) respondents in the study area have faced seasonal feed shortages, from which the majority of them have faced the feed-related challenge in the dry season (79.3%) while others (20.7%) were in the wet season (Table ). The result was similar to (Tesfahun, Citation2013) and (Asefa et al., Citation2015) findings, who mentioned that feed shortage in dry seasons of the year caused by erratic rainfall, was a critical challenge for goat keepers in South Omo and Bale Zones. But, the present result was contradicted Tsegaye (Citation2009) finding, who reported feed shortage was not a limiting factor for goat production in Metema area. Seasonal feed shortage in the study areas may be due to the application of intensive crop production, and the presence of stock exclusion areas for soil and water conservation activities resulted in the shrinkage of communal lands for livestock stocking. In the area, farmers have supplemented goats using homemade grains and cut tree branches (78.7%), reduced flock size (11.5%), and used conserved feed (9.8%) at times of feed shortage. Besides, in the area, goats were supplemented to enhance productivity.

Table 9. Feeding practices and management of goats in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.9. Watering management

Table shows water sources for goats in the dry and the wet seasons of the year in the area. Most (93.1%) of respondents were reported river water was the primary water source for goats, followed by spring (5.9%) and underground water (1%) in the dry season. Similarly, the most frequently reported water source in wet seasons was river water (92.1%), followed by spring water (7.9%). This finding was similar to other researchers’ work in Ethiopia (Alemu, Citation2015; Gatew, Citation2014; Zergaw, Citation2014). However, it disagreed with Asefa et al. (Citation2015) report, which stated that spring water followed by borehole water was the primary water source for goats. The overall average hour (mean ± SD) traveled by goat keepers from home to the nearest watering point was 0.39 ± 0.24 hours. The average traveling hour by respondents from Bibugn district (0.29 ± 0.24 hour) was significantly (P < 0.01) lower than Hulet Eju Enesie (0.43 ± 0.25 hour) and Goncha Siso Enesie (0.42 ± 0.20 hour) districts.

Table 10. Familiar water sources in the dry and the wet seasons of the year in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.10. Goat houses and housing systems

A properly constructed house is required to protect goats from extreme environmental weather conditions, diseases, predators, and theft and make management easier (Asefa et al., Citation2015). The type of goat houses varies with the environmental temperature and type of production. In the area, three types of goat housing systems, i.e. separate housing (81.7%), housing with other animals (14.4%), and housing within the human house (4%), were identified (Table ). Goat houses were mainly built from iron sheet (roof) and wood (wall) (89.1%) and grass (roof) and wood (wall) (10.1%). Mixed goat housing may create a conducive environment for infectious diseases transmission from animals to animals and zoonotic disease from animals to humans and vice versa. In Bibugn district, goat keepers have constructed the floor of goat houses 1 cm above the ground and covered it with a Bamboo plant (Figure (a, and b) for adequate drainage of urine and manure away from the laying area. Different scholars from Ethiopia had reported similar results (Asefa et al., Citation2015; Tesfahun, Citation2013; Zergaw, Citation2014),

Figure 3. Common goat houses types in Bibugn for adults (a) and kids (b); Goncha Siso Enesie (c), and Hulet Eju Enesie (d) districts.

Table 11. The goat housing systems in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.11. Castration practice

Castration is part of small ruminant management practices mainly applied to non-breeding males and males not slaughtered at a younger age for controlled breeding and production of the fattened carcass (Abebe & Yami, Citation2008). Ideally, castration should be implemented in less than three weeks, but it is not the case in Ethiopia. Results concerning buck castration practice in the study area are presented in Table . In the study area, the majority (98.5%) of goat keepers have reported castration of male goats, which is similar to the findings of (Tesfahun, Citation2013) and (Gatew, Citation2014) who reported that the majority of goat keepers in South Omo Zone, and Siti and Bati areas practice buck castration. In contrast to this, (Asefa et al., Citation2015) and (Gebreselassie, Citation2015) noted that due to the marketing of male goats at an early age, low market acceptance of castrated bucks, and the presence of cultural influences in the areas, castration was not common in Bale Zone (85.3) and Lare and Jikawo districts of Nuer Zone (85.55%).

Table 12. Buck castration and castration practices in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

The majority (54.3%) of goat keepers have used the traditional castration method that is carried out by experienced individuals in the community using smooth wood, stone, or blunt-sided iron. However, modern (24.1%) and combinations of both modern and traditional (21.6%) castration methods have been applied to castrate male goats. The majority (71.4%) of the respondents were castrating their goat in the wet season (at the start or end of the main rainy season) when feed availability is relatively better. While the remaining (28.6%) castrate goats in the dry season since they thought that wounds created by the castration process would not dry sooner if goats were castrated in wet seasons. Fattening, fattening and controlling unwanted mating, fattening and avoiding goatee smell, and fattening and ease of management were the reported reasons for buck castration. However, fattening and preventing goatee smell (56.8%) was covered the highest proportion, followed by fattening (38.7%). Similarly, fattening was mentioned as the primary reason for buck castration by Arab and Oromo goat keepers (Sheriff et al., Citation2020)

The overall mean castration age of bucks in the study area (2.05 ± 0.24 years) was significantly (P < 0.05) lower for bucks in Bibugn district (2.00 ± 0.22 years) than for bucks in Goncha Siso Enesie (2.05 ± 0.26 years) and Hulet Eju Enesie (2.10 ± 0.24 years) districts. The present result was nearly comparable previous reports (Gatew, Citation2014; Zergaw, Citation2014; Gebre et al., Citation2020), who noted the average castration age of goats in Borena, Konso, and Aba’ala areas were 2.2 ± 0.11, 2.4 ± 0.8, and 2.3 ± 1.9 years, respectively. But, it was lower than the report by Gatew (Citation2014), who recorded an average castration age of 3.17 ± 0.09 years for the Siti area.

3.1.12. Breeding management

3.1.12.1. Selection of breeding flock

Selection, allowing individuals with desirable traits to be parents of the next generation, is usually done within cohorts within a flock, among animals of the same age that have been raised together (Abegaz & Awgichew, Citation2008). In the visited area, almost all goat keepers reported selection of breeding does (98.5%) and bucks (99%) to establish the breeding flock. However, there were also goat keepers who reported selection of either sex (Table ). The present result is similar to Alebel et al.(Citation2020) report, which stated that goat keepers in Mandura district, Metekel Zone practice selection of both does and bucks. The average selection age (mean ± SD) of males and females were (5.00 ± 2.88; 4.88 ± 2.78 months) in Bibugn, (4.88 ± 2.23; 4.56 ± 1.86 months) in Goncha Siso Enesie, and (4.61 ± 1.63; 4.49 ± 1.64 months) in Hulet Eju Enesie districts. The overall selection ages (mean ± SD) for males and females were 4.83 ± 2.26 months and 4.63 ± 2.10 months, respectively. Females were selected at an early age than males, which is likely to be correlated with the early sexual maturity of females than males. There was no significant (P > 0.05) difference among the study districts in the selection age of male and female goats.

Table 13. Selection practices of breeding does and bucks in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.12.2. Breeding does selection criteria

Careful selection of breeding females in small ruminant production enhances the flocks’ productivity, thereby increasing farm profitability. Small ruminants can be selected based on performance records and/or visual appraisal, of which selection based on records (objective selection) is better than selection by physical appraisal (subjective selection). However, selection based on a visual appraisal conducted by looking at the appearance, conformation, and presence or absence of defects in the animal is vital in areas where record-keeping is not practical (Abegaz & Awgichew, Citation2008). The same was true in areas covered by this particular study. Goat keepers were practiced the selection of breeding females by physical observation based on their trait preferences (Table ). Body size (growth), hair coat color, and pigment, and conformation characteristics were rated as 1st, 2nd, and 3rd selection criteria of breeding does with index values of 0.353, 0.225, and 0.205, respectively. Female goats with a good growth rate (large), white coat-colour, and red-pigmented tail line, muzzle, and inner ears, and are structurally correct, are selected as breeding does.

Table 14. The breeding doe selection criteria (rank) in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

Reproduction abilities, adaptation, udder and teat traits, horn traits, tail traits, and ear traits were also considered selection criteria to select breeding does in the area. Good reproducibility (early maturity, multiple births, short kidding interval, and longer productive life), a healthy udder hanging above the hocks, healthy teats, straight horns pointing backward, and wide and long tail and ears are preferred traits to select breeding does. Similar results were reported for Arab and Oromo goat keepers in Assosa Zone, Benishangul Gumuz Region (Sheriff et al., Citation2020), and goat keepers in Aba’ala, Afar Region (Gebre et al., Citation2020).

3.1.12.3. Breeding bucks selection criteria

In small ruminant production, breeding bucks should also be selected to optimize the overall flock productivity since it determines the overall pregnancy rate in the flock and shares 50% of the genetic makeup of kids born. Body size (growth), conformation, coat color, and pigment were the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd rated breeding buck selection criteria, respectively (Table ). Accordingly, male goats with better growth rate, good conformation (structurally correct), and white coat colour (Bibugn district) white, red and white and red mixed colour (Goncha Siso Enesie and Hulet Eju Enesie districts) were selected as breeding bucks than their contemporaries. Besides, goat keepers from Bibugn district were concerned for horn traits, cannon bone perimeter, tail traits, ear traits, adaptation traits, and libido and mating ability of bucks to select breeding bucks. In contrast, goat keepers in Goncha Siso Enesie and Hulet Eju Enesie districts focus more on horn traits, adaptation traits, libido and mating ability, cannon bone perimeter, and tail and ear traits of bucks. Hence, in the area covered by this study, a buck with straight horns pointing backward, fat cannon bone perimeter, wide and long tail and ears, environmentally adaptive, having better libido, and effectively mate with the opposite sex are preferable to be a breeding buck.

Table 15. The breeding buck selection criteria (rank) in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

Generally, goat keepers in the study area were focused more on body size, conformation, and colour traits to select breeding does and bucks. This may be due to goats with these characteristics being preferred by goat producers in the area and creating great bargaining power to the seller and the ability to fetch a better price in the market. The present result was similar to previous reports (Gatew, Citation2014; Gebre et al., Citation2020; Sheriff et al., Citation2020; Zergaw, Citation2014).

3.1.12.4. Possession of breeding buck(s) and mating system

The majority (84.7%) of the visited goat keepers had breeding buck(s) to breed does in the flock. However, few (15.3%) were used breeding bucks available in the neighborhood (8.9%) and at grazing fields (6.4%) to breed does (Table ). This result was similar to Tesfahun (Citation2013) and Gatew (Citation2014) reports, who noted that most goat keepers from the South Omo Zone and Borena and Siti areas had breeding bucks. Goat keepers in the area have kept bucks for multiple purposes, of which the majority (72.8%) were kept bucks for the aim of mating and fattening. Selected bucks are first used for mating, then they were castrated and fattened either for marketing or home consumption. Only 13.4% of goat keepers in the area were reported natural, controlled mating while the majority (86.6%) were used natural, uncontrolled mating. Herding male and female goats on similar grazing/browsing fields (84%), lack of awareness on controlled breeding (0.6%), and combination of the two (15.4%) were the reported reasons for uncontrolled mating. From these herding of both sexes together for grazing/browsing was covered the highest. This result is similar to the reports of other researchers in Ethiopia (Gatew, Citation2014; Gebreselassie, Citation2015; Tesfahun, Citation2013; Zergaw, Citation2014), who reported the natural, uncontrolled goat mating system is the most frequently used goat breeding system in the traditional goat production system. In the area, goat mating was seasonally restricted (93.1%), and in most cases, it was occurred in the short rainy seasons (autumn and spring) (75.2%), while some will mate in summer (17.8%; Table ). Seasonal feed shortage, especially in winter, was the reported reason for the seasonal variation of goat mating. Similarly, Abebe (Citation2008) noted that in the Ethiopian highlands, most conception in sheep and goats occurs during or following the short rain (spring) season.

Table 16. The possession and purpose of keeping breeding buck(s) in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.12.5. Culling and replacement of breeding flock

Culling, removing un-productive goat(s) from the flock, is an important management practice to enhance flock productivity. The reason and method of culling are varied with goat production systems (Abebe & Yami, Citation2008). All visited goat keepers in the study area practice culling of unproductive goats, of which 84.7% of the goat keepers apply culling to reduce management costs. While 15.3% of goat keepers were practice culling for genetic improvement. Old goats (60.9%) and kids attained marketing age (39.1%) were the priority age class of goats most frequently culled. Selling (33.7%), slaughtering (6.9%), and selling and slaughtering (59.4%) were the commonly mentioned methods of culling. Born from own flock, own flock and purchasing, and purchasing from local market and neighbourhood were the main sources of goats to replace the breeding flock (Table ).

Table 17. Culling and replacement of goat breeding flock in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

3.1.13. Reproductive performances of indigenous goats

The recorded reproductive performances of indigenous goat types are presented in Table . The average ages of sexual maturity for male and female goats were 7.01 ± 1.55 and 6.69 ± 1.64 months, respectively. The result indicated that females are more sexually mature early than their male counterparts. The average age at first mating (AFM) of male goats in Bibugn district was significantly (P < 0.001) longer than the AFM of male goats in Goncha Siso Enesie and Hulet Eju Enesie districts. However, there was no significant (P > 0.05) difference in average age at first mating for female goats among the visited areas. The obtained result in this study for male goats was similar to the report of (Sheriff et al., Citation2020), who recorded 7.0 ± 1.0 months average age at sexual maturity of Arab goats. In contrast, it was shorter as compared to the values reported for local goats (11.1 ± 1.5 months) from northwest Amhara (Alemayehu & Kebede, Citation2017) and Maefur goats (9.52 ± 0.60 months; Gebreyowhens & Kumar, Citation2018). The obtained value for female goats was shorter than the values for Maefur goats (12.7 ± 2.1 months; Gebreyowhens & Kumar, Citation2018), Begait goats (7.15 ± 1.04 months; Abraham et al., Citation2019), Arab goats (7.9 ± 0.9 months), and Oromo goats (8.3 ± 0.7 months; Sheriff et al., Citation2020). The shorter age at first sexual maturity of goats in the present study may be due to genetics and management differences.

Table 18. The reproductive performances of indigenous goat types in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

The average age at first kidding (AFK) in this study was 13.02 ± 2.18 months. The recorded value for Bibugn district (14.75 ± 2.83 months) was statistically (P < 0.001) longer than the recorded values for Hulet Eju Enesie (12.34 ± 1.15 months) and Goncha Siso Enesie (12.33 ± 1.53 months) districts. However, there was no significant (P > 0.05) difference in AFK of goats in Hulet Eju Enesie and Goncha Siso Enesie districts. The obtained result in the present study was almost comparable with the AFK of local goats (13.12 ± 0.10 months; Hussein, Citation2018) and Central Highland goats (13.59 ± 1.35 months; Taye et al., Citation2013), recorded under extensive management conditions. However, the present result was shorter than the AFK of Maefur goats (21.1 ± 2.0 months; Gebreyowhens & Kumar, Citation2018), Begait goats (14.30 ± 1.21 months; Abraham et al., Citation2019), and Oromo goats (14.9 ± 2.4 months; Sheriff et al., Citation2020). In contrast, the present result was longer than the value recorded for local goats (12.34 ± 0.25 months) from northwestern Amhara reported under extensive management conditions (Alemayehu & Kebede, Citation2017).

In the present study, indigenous goats’ average kidding interval (KI) was 6.47 ± 0.69 months which is nearly similar to the kidding interval of central highland goats (6.6 ± 1.37 months) recorded under the extensive management condition (Zergaw, Citation2014). But, the present result was shorter than the values recorded for Abergelle goats (12.07 ± 2.73 months; Jembere et al., Citation2019), Oromo goats (7.8 ± 1.1 months; Sheriff et al., Citation2020), and Begait goat (8.09 ± 0.09 months; Abraham et al., Citation2019), recorded under extensive management condition. The differences in kidding interval among Ethiopian indigenous goat types may be due to breed, location, and management differences, which enhance the possibilities of re-conception after parturition.

Litter size at birth (LSB) in the present study was 2.15 ± 0.38 kids per kidding doe. This result is comparable with the values for Sidama goats (2.07 ± 0.13 kids) reported by (Assefa, Citation2007). However, the preset result was higher than the litter sizes of Central Highland goats (1.16 ± 0.04 kids; Taye et al., Citation2013), Begait goats (1.52 ± 0.02 kids; Abraham et al., Citation2019), and Abergelle goats (1.00 ± 0.170 kids; Jembere et al., Citation2019), recorded under extensive management conditions. The higher litter size obtained in this study may be due to genetics, management differences, and farmers’ selection practices that give due attention to prolificacy as a selection criterion of breeding does. In this study, the overall average productive life of does (PLD) was 6.93 ± 2.38 years. This result was longer than the productive age of Woyto Guji goats (4.72 ± 0.08 years; Tesfahun, Citation2013) and shorter as compared with the values of local goats (8.24 ± 0.33 years; Alemayehu & Kebede, Citation2017). The variation in average dos productive life may be due to the variable culling age of goats by goat keepers across locations and production systems.

3.1.14. Common goat diseases and health management

In Ethiopia, small ruminant production in general and communal goat production, in particular, are highly constrained by diseases and parasite incidences (Sissay et al., Citation2006). Sheep (goat) pox, peste des petits ruminants (PPR), fascioliasis, pasteurellosis, and respiratory diseases are the common goat diseases in Ethiopia (Abegaz, Citation2014). Interviewed households from all the study areas have ranked the economically important goat diseases and parasites in the study areas (Table ). Anthrax, goat pox, ovine pasteurellosis, ectoparasites (lice, fleas and tick), contagious ecthyma, and brucellosis were ranked in the visited site as1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th diseases based on the occurrence and economic loss caused by the incidence. Goat keepers were called the economically important goat diseases with local names, most commonly associated with their symptoms, rather than by common names of the diseases. Accordingly, anthrax, goat pox, ovine pasteurellosis, ectoparasites (lice, fleas, and tick), contagious ecthyma, and brucellosis were termed as “Tembes”, “Fentata”, “Mechie”, “Dermen”, “Qitegn/Gumero”, and “Yewureja beshita”, respectively. Farmers in the study areas have identified a particular disease based on the observed clinical signs on the infected goats.

Table 19. The importance (rank) goat diseases in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

More than half (57.4%) of the interviewed households were reported that newborn kids were the most frequently affected age class (Table ). Sabapara and Deshpande (Citation2010) observed that from different age classes of Surti goats managed under field conditions, the mortality rate was the highest in 0 to 3 months age group followed by 3 to 12 months age was least among the adult group. In the area, goat keepers were ought to travel 1.15 ± 0.44 hours to reach the nearest veterinary clinic. The average traveling hour in Goncha Siso Enesie district (1.32 ± 0.49 hours) is significantly (P > 0.001) higher than in Hulet Eju Enesie (1.06 ± 0.37 hours) and Bibugn (1.01 ± 0.38 hours) districts (Table ). This indicated that even though the government established veterinary clinics commonly located at the center of each peasant association, farmers ought to travel long distances may be impossible if the animal is very sick. Some (25.2%) of goat keepers were applied traditional treatments to treat goat diseases. Fumigate with parts of selected herbs (the vegetative part of “Aregressa” and root of “Keberecho”) for ovine pasteurellosis (“Mechie”), fumigate by dried animal dung (dung from monkey and cattle), and herbs (“Keberecho” root) for respiratory disease (“Kuro”), washing by salt solution, smearing by food salt (“Dekuse”) with hot “Injera”, and fumigate by herb root (“Gumero”) for contagious ecthyma (“Qitegn/ Gumero”) were among the reported traditional treatments used by the respondents in the study areas.

Table 20. Veterinary services and treatment of sick goats in east Gojjam zone of Amhara region

4. Conclusion

The study revealed that illiteracy is high, and the mixed crop-livestock production system is the dominant agricultural system. Goats have the highest proportion of all livestock species kept in the area and are mainly raised for income generation. Hillside browsing and river water are the main feed and water sources of goats, respectively. Goats are housed in separate houses built from iron sheets and wood. Farmers use more subjective than objective criteria to select breeding does and bucks, which contradicts the ideal criteria for improved performances. Although most farmers have breeding buck(s), in the area, natural, uncontrolled goat mating is common. Goats in the study areas have better reproductive performances that give opportunities for further improvement of the breed. However, uncontrolled mating, absence of flock mixing, replacing breeding does and bucks from own flock, and low male-to-female ratio in the flock will enhance the inbreeding level within the flock, and result in inbreeding depression. Thus, providing training for goat keepers concerning the purposes of avoiding those issues is needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their great appreciation to the Ministry of Education, Dilla University, and Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia, for facilitating the research process. The authors also duly acknowledge all agriculture development experts and goat keepers in the area for their help during data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mezgebu Getaneh

Mezgebu Getaneh is a Ph.D. student in the department of Animal Genetics and Breeding at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia

Mengistie Taye

Mengistie Taye is an Associate Professor of Agricultural Biotechnology at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia.

Damitie Kebede

Damitie Kebede is an Assistant Professor of Animal Genetics and Breeding at Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia.

References

- Abebe, G. (2008 Reproduction in sheep and goats. Yami , A, Merkel , RC). Sheep and Goat Production Handbook for Ethiopia (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopia Sheep and Goat Productivity Improvement Program (ESGPIP)), p 57–30.

- Abebe, G., & Yami, A. (2008 Sheep and goat management. Yami, A, Merkel, RC). Sheep and Goat Production Handbook for Ethiopia (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopia Sheep and Goat Productivity Improvement Program (ESGPIP)), 34–57.

- Abegaz, S., (2014). Design of community based breeding programs for two indigenous goat breeds of Ethiopia. PhD University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences.

- Abegaz, S., & Awgichew, K. (2008 Genetic improvement of sheep and goats). Sheep and Goat Production Handbook for Ethiopia (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopia Sheep and Goat Productivity Improvement Program (ESGPIP)), p 82–102.

- Abraham, H., Gizaw, S., & Urge, M. (2019). Growth and reproductive performances of Begait goat under semi intensive and extensive management in western Tigray, north Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development 31 3, http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd31/3/hagsa31032.html.

- Alebel, M. G., Wolele, B. W., & Kide, H. A. (2020 Characterization of Goat Production System and Breeding Practices of Goat Keepers for Community-Based Breeding Strategies at Mandura, Metekel, Zone, Ethiopia). International Journal of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Science 5 4 .

- Alemayehu, K., & Kebede, D. (2017). Evaluation of morphometric and reproductive traits of indigenous dairy goat types in North Western Amhara, Ethiopia. Iranian Journal of Applied Animal Science, 7(1), 45–51.

- Alemu, A. (2015). On-farm phenotypic characterization and performance evaluation of Abergelle and Central Highland Goat breeds as an input for designing community-based breeding program. Haramaya University. MSc.

- Asefa, B., Kebede, K., & Effa, K. (2015). Assessment of production and reproduction system of indigenous goat types in Bale Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Academia Journal of Agricultural Research, 3(12), 348–360 doi:10.15413/ajar.2015.0143.

- Aseged, T., Hailu, A., Assefa, A., Getachew, T., Misganaw, M., Sinke, S., Getachew, F., & Abegaz, S. (2021). Goat breeding practice and production constraints in Boset and Minjar Shenkora districts of Ethiopia. Genetics and Biodiversity Journal (Gabj), 5(2), 107–117 https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v9i10.1876-1882.4492.

- Assefa, E. (2007). Assessment on production system and marketing of goats at Dale District (Sidama Zone). MSc, Hawassa University.

- CSA. (2016). Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa. CSA and ICF.

- CSA. (2021). Central Statistical Agency. Agricultural sample survey 2020/2021. Report on livestock and livestock characteristics (private peasant holdings). In Statistical bulletin. Addis Ababa 1–199 .

- Districts’ Agriculture development Offices (DADO). (2019). Livestock censes of Hulet Eju Enesie Enesie, Goncha Siso Enesie Siso and Bibugn districts, unpublished. East Gojjam Zone.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). (2011). Draft guidelines on phenotypic characterization of animal genetic resources Food and Agriculture organization Animal Production and Health Guidelines (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). (2012). Phenotypic characterization of animal genetic resources. In Food and Agriculture organization Animal Production and Health Guidelines no 11 (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) .

- FOASTAT. (2019). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations STAT http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#ata/QC ().

- Gatew, H. (2014). On-farm phenotypic characterization and performance evaluation of Bati, Borena and Short eared Somali goat population of Ethiopia. Haramaya University. MSc.

- Gebre, K. T., Yfter, K. A., Teweldemedhn, T. G., & Gebremariam, T. (2020). Participatory definition of trait preferences and breeding practices of goats in Aba’ala, Afar region: As input for designing genetic improvement program. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 52(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-01968-1

- Gebreselassie, T. (2015). Phenotypic characterization of goat type and their husbandry practices in Nuer Zone of Gambella people regional state. Haramaya University. MSc.

- Gebreyowhens, W., & Kumar, R. (2018). Management and Breeding Objectives of Maefur goat breed type in Erob district eastern Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 9(3), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2017.0423

- Haile, A., Gizaw, S., Getachew, T., Mueller, J. P., Amer, P., Rekik, M., & Rischkowsky, B. (2019). Community‐based breeding programmes are a viable solution for Ethiopian small ruminant genetic improvement but require public and private investments. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 136(5), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbg.12401

- Hussein, T. (2018). Local sheep and goat reproductive performance managed under farmer condition in Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 9(10), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2018.0509

- Jembere, T., Haile, A., Dessie, T., Kebede, K., Okeyo, A. M., & Rischkowsky, B. (2019). Productivity benchmarks for community-based genetic improvement of Abergelle, Central Highland and Woyto-Guji indigenous goat breeds in Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development 31 5 http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd31/5/tjbak31074.html .

- Joshi, A., Kalauni, D., & Bhattarai, N. (2018). Factors affecting productive and reproductive traits of indigenous goats in Nepal. Archives of Veterinary Science and Medicine, 1(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.26502/avsm.003

- Kosgey, I., (2004). Breeding objectives and Breeding strategies for small ruminants in the tropics. PhD, Wageningen University.

- Mekuria, W., Mekonnen, K., & Adugna, M. (2020). Farm diversification in the central highlands of Ethiopia: Patterns determinants and its effect on household income. Review of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 23(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.15414/raae.2020.23.01.73-82

- NBE (2018). Annual report 2017/2018. Addis Ababa

- Sabapara, G., & Deshpande, S. (2010). Mortality Pattern in Surti goats under field condition. Veterinary World, 3(4), 165–166 https://doaj.org/article/b74d80a19db74db78709f915a1089524.

- SAS. (2003). SAS User’s Guide: Statistics. Ver. Vol. 9.1. Statistical Analysis System, Cary.

- Sheriff, O., Alemayehu, K., & Haile, A. (2020). Production systems and breeding practices of Arab and Oromo goat keepers in northwestern Ethiopia: Implications for community-based breeding programs. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 52(3), 1467–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-02150-3

- Sissay, M. M., Asefa, A., Uggla, A., & Waller, P. J. (2006). Anthelmintic resistance of nematode parasites of small ruminants in eastern Ethiopia: Exploitation of refugia to restore anthelmintic efficacy. Veterinary Parasitology, 135(3–4), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.09.005

- Taye, M., Deribe, B., & Melekot, M. (2013). Reproductive Performance of Central Highland Goats under Traditional Management in Sekota District, Ethiopia. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences, 6(5), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2013.271.276

- Tesema, Z. (2019). On-station and on-farm performance evaluation and genetic parameters estimation of Boer x Central Highland crossbred goat in North Wollo Zone, Ethiopia. MSc, Bahir Dar University.

- Tesfahun, B., (2013). Phenotypic and production system characterization of Woyto Guji goats in lowland areas of South Omo zone. MSc Thesis, Haramaya University.

- Tsegaye, T. (2009). Characterization of goat production systems and on-farm evaluation of the growth performance of grazing goats supplemented with different protein sources in Metema woreda, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Thesis. pp48. MSc, Haramaya University

- Wodajo, H. D., Gemeda, B. A., Kinati, W., Mulem, A. A., van Eerdewijk, A., & Wieland, B. (2020). Contribution of small ruminants to food security for Ethiopian smallholder farmers. Small Ruminant Research, 184, 106064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2020.106064

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, an introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Zergaw, N. (2014). On farm phenotypic characterization and performance evaluation of central highland and Woyto guji goat types for designing community based breeding strategies in Ethiopia. Haramaya University. MSc.

- Zewdie, B., & Welday, K. (2015). Reproductive performance and breeding strategies for genetic improvement of goat in Ethiopia: A review. Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 5(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.15580/GJAS.2015.1.080614317