Abstract

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp) is a vital legume crop for Zambia’s urban and rural households. The crop is an important legume used as human and animal food and as a component of the agricultural production system, which improves the fertility of many depleted soils because of its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. Government through the ministries of health and agriculture recommend its’ use. Despite the importance of cowpea in the nation, there is limited information on the crop along with its’ value chain components. This review aims to assemble pertinent information on cowpea and its value chain components in Zambia. A critical look through the food system from production to consumption reveals the prevailing gaps in knowledge and output. The information covered here touches on crop breeding, production, marketing, processing, and consumption. This paper delves into various literature, bringing out the salient issues that are not commonly discussed about on the crop. It is a situation analyses focusing on finding solutions to improving the relevance and appreciation of the crop. There is a need for agricultural policies to promote cowpea production and use with the active participation of relevant actors. This would create a conducive environment for determining user needs, and leading to the development of beneficial impact-related activities at various stages. The country needs to begin incorporating a variety of crops within the food system to complement maize to improve nutrient intake, contribute to climate-smart practices, and sustainability of agricultural practices within communities in Zambia.

1. Background

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.), commonly known as the black-eyed pea, is a legume of significant importance to the livelihoods of millions of people in less developed countries, especially in the drier tropics. It is a relatively drought-tolerant and warm-weather crop that drives well in semi-arid regions of the tropics where other food legumes do not perform well. The crop’s performance is favoured in Zambia, with an average annual temperature of 30°C and rainfall ranging between 800 mm to over 1000 mm (Hamududu & Ngoma, Citation2019). The crop is prevalently grown and produced by small-scale farmers, particularly in the Southern province of Zambia, the most drought-prone area in the country, with parts of it receiving as little as 500 mm of annual rainfall (Kaluba et al., Citation2017). The crop also provides the bulk of highly nutritious, inexpensive dietary protein intake and valuable micronutrients for many poor households, hence the reference to it as a “poor man’s crop” (Gondwe et al., Citation2019). This may change as the crop is currently receiving increased attention from political and development organizations (Ousmane et al., Citation2020). The development of dual-purpose varieties in the country (Munyinda, Citation2020) provides for grain and vegetable consumption, including animal fodder. This complements the feeding options of the prominent traditional animal rearing system, focusing on dairy and cattle in the various provinces. The use of cowpea in the country does not end there; the crop is also an excellent soil infertility remedial crop. Also, it is used in pest and disease control, especially when grown in rotation with cereal crops, a system practiced across the country (IAPRI, Citation2021a). Undoubtedly, cowpea has a great potential for production and use in Zambia, especially as an indigenous climate-friendly crop and cheap protein source with various potential markets. As recently published by multiple authors, the promotion of food and dietary diversity strategies calls for collective efforts to support the production of diverse, healthy, and environmentally sustainable foods, with legumes, among them cowpeas, as crucial complementary crops (Gondwe et al.,Citation2019; FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, W. and W, Citation2017; IAPRI, Citation2021a). Therefore, one question that arises; is cowpea delivering as a crop within the food system in Zambia? Despite all the valuable characteristics that the crop possesses and exhibits, there are several aspects, be it challenges or advances in the cowpea value chain in the country, which have not been extensively discussed and documented. Consequently, the paper presents an overview of potential opportunity areas for the crop which could be useful in years to come for strategic approaches to cowpea and its place in the food system of Zambia. The paper covers a wide range of aspects in the crop’s value chain based on a review of literature and policy documents, with the provision of relevant models and recommendations.

2. Agricultural and nutrition policy outlook

Cowpea is a crop currently being grown and produced primarily by smallholder farmers. To foster crop production, the government has included the crop in the Farmer Input Support Programme (FISP) as a good crop diversity option (among others, such as soybean and rice) in complementing the maize-focused production and consumption systems. Due to historical maize-centric agricultural policies, the Zambian food system has solely relied on maize as the main staple (Alamu et al., Citation2021; Mulenga et al., Citation2020). The dependence on maize production and use is precarious and inimical to improved household and nutritional security (Chilufya & Mulendema, Citation2019). According to developmental policies, such as the Eighth National Development Plan (MFND, Citation2022) and the National Agricultural Policy (2012–2030), diversification of crops, including cowpea, produced, consumed, and their value addition is vital for Zambia. With the current climate change effects (floods and drought) being experienced in Zambia, cowpea is a priority crop being recommended to farmers by the government (Mulungu et al., Citation2021). However, through various situational updates, the government recently identified inadequate capacity for value addition regarding the complementary indigenous crops and a low variety of preparation methods of nutritious meals across Zambia to ensure balanced diets (Mofya-Mukuka & Musonda, Citation2016). The realization that utilization of cowpea was poor among the households and, within markets, was consequently affecting the crop production among the farmers. Therefore, agricultural departments (Zambia Agricultural Research Institute (ZARI), Universities) and various organizations (Food and Agricultural Organisations (FAO), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (GIZ)) began and are fostering research and extension services, particularly on production, consumption, and value addition as critical components for achieving food security within the country. International development organizations (World Food Program (WFP) and GIZ) are supporting deliberate projects where cowpea is being promoted in production and processing as well as utilization within the value chain (Marinda et al., Citation2018; WFP, Citation2020). Zambia Agricultural Research Institute, International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA), and the University of Zambia (UNZA) are playing an active role in research-based advancements within the cowpea value chain, although not at the pace of improvement as the other legumes (i.e. groundnuts; ZRI, Citation2021). More focus is mainly on soybean, beans, and groundnuts. This is disadvantageous to many low-end users as some of these legumes are high input and labor intensive, region specific and many small-scale farmers are not financially able to grow them, for example, soybean. Current policies need to be strengthened, through the implementation process, the proactive use of legumes in our food system, particularly cowpea, to contribute to improved food and nutrition security in Zambia (IAPRI, Citation2021a).

3. Productivity and seed variety development

The average cowpea yields in Zambia have remained low, ranging from 0.2 to 0.8 tons/ha against a potential yield of 3 to 4 tons/ha (Nkhoma et al., Citation2020a). The yield gap is attributable to a low number of improved high yielding cultivars, increased use of local varieties, poor soil fertility, poor agronomic practices, and abiotic and biotic production constraints (Mbuma et al., Citation2021). The development of seed cultivars that are locally adapted has always been seen as a means to improve seed quality, maintain the plant genetic pool and purity and reduce the effects of many stresses that affect crops in various places (Hove & Bakker, Citation2020).

ZARI working with seed companies, universities, have led the way in variety development and research of cowpea. However, almost all the organizations involved in plant breeding in the country have only been using conventional methods (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, W. and W, Citation2017; Maria Figueira Gomes et al., Citation2019). Before the 1980s, Zamseed, a local seed company, spearheaded cowpea variety research using conventional means. In 1984, the seed company released two varieties (Shipepo and Muliana). These varieties are no longer in production. The next variety to be released by the company was Lutembwe, in 1993 and Bubebe was released in 1995. Due to the use of conventional plant breeding methods, it takes a long time before another cowpea variety could be released.

The delay in release of subsequent varieties, results in varieties that are ineffective and less valuable, as at the time of pre-release, many environmental, social, and biological changes and needs would have arisen. With the prevailing changes in climatic conditions and the evolution of different insects and diseases, the outstanding characteristics of these old varieties and agronomic performance would have eventually deteriorated. It has been shown that most legumes, including cowpea, have lost many alleles for high productivity, seed quality, pest, and disease resistance in the process of adaptation to environmental stress (Horn & Shimelis, Citation2020). However, Lutembwe is still a popular variety among farmers, despite being released 29 years ago. It demonstrates high stability for most traits and would be a good source of genes as a parent to introgress into other varieties. However, limited information and awareness about the availability of new varieties may be contributing to the popularity and continual use of older varieties such as Lutembwe. ZARI also bred and released varieties; Musandile, Namuseba, and Mtilizi in 2004, 2011, and 2018, respectively, to increase yields and productivity and mitigate adverse environmental impacts. Furthermore, UNZA, in collaboration with local partners and an external partner (International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)), embarked on crop improvement and development of cowpea varieties with high yield potential and with tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses in 2016 (Munyinda, Citation2020; Simunji et al., Citation2019; Tembo et al., Citation2017). The University of Zambia Breeding program released two varieties, Lukusuzi and Lunkwhankwa, in 2018 (IAEA, Citation2020;Horn, Citation2016; Horn & Shimelis, Citation2020).

Induced mutations with gamma radiation were used to generate novel alleles not previously existing in the local germplasm. At present, some molecular breeding techniques and genomic resources, such as polymerase-chain reaction (PCR), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), and genetic diversity, are being used in the development of varieties by the research institutes and universities in Zambia (FAO, Citation2016; Kirkhouse trust, Citation2022). More genomic tools, such as the use of quantitative trait loci (QTL) in trait selection, linkage mapping, marker-assisted breeding and reference populations (candidate gene associations), and intercountry learning are being used to increase cowpea breeding advancements (Boukar et al., Citation2016).

Variety release in Zambia have shown lapse in seed multiplication, resulting in deficient commercial availability of the released varieties in cowpea and legumes (IAPRI, Citation2021a). Legumes are overlooked in seed multiplication programs by the government and most seed companies, as they are self-pollinating and are not profit earners (low returns on investment). A few seed companies and research departments use smallholder farmer seed systems to maintain (community seed banks) and multiply seeds (contract farming) because smallholder farmers are more prominent in the provinces than commercial farmers, who may not necessarily be interested in growing the crop. More support and promotion of small-scale seed producers is recommended as it empowers the farmers with income and food security (Munyiri, Citation2020). The list of cowpea varieties developed to date in Zambia is shown in .

Table 1. Cowpea varieties released in Zambia

The characteristics of the varieties developed and released are not documented, and the preliminary features are shown in (ZARI, Citation2021).

Table 2. Characteristic traits of the seven released varieties in Zambia

There is limited information on nutrient use efficiencies and toxicities for the varieties in the crop except for a recently released variety, Lukusuzi and the nutritional characteristics of the varieties are also not available. More research still needs to be conducted to identify and improve cowpea trait performance, especially with the current soil fertility challenges that the country is experiencing (Ngoma et al., Citation2021). Nkhoma et al. (Citation2020a) documented that the yield stability of the varieties in various agro-ecological zones. Furthermore, another study by Nkhoma (Citation2011) looked at the anti-nutritional factors in cowpea, and Hachibamba et al. (Citation2013) studied the effect of cooking on phenolic and antioxidant content in cowpea. However, very little information has been generated since then on the nutritional quality of the various varieties (Gerrano et al., Citation2019) and the farmer preferences (Nkhoma et al., Citation2020a).

Farmers in Zambia widely grow unimproved landraces due to the low availability of improved and locally adapted farmer-preferred cultivars (Horn, Citation2016). However, there is no recent information on the prevalence of local and improved seeds among farmers (Tripp et al., Citation1998). Identifying and maintaining diverse sources of cowpea genetic material (including local and wild varieties) is helpful to conserve traits and improve the adaptability of the varieties. Although seven varieties are documented as released, most of them are not commercially available and do not fully carry farmer-preferred quality traits. Hence, the high tendency for farmers to use local varieties. Government as well as private companies need to work together to ensure that the varieties are commercially available, by putting the right-seed access policies and a decentralized seed system in place to complement the commercial seed system. It is also important to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the responsible institutes to carry out their activities and evaluate their performance

3.1. Key: Lt: Lutembwe; Bb: Bubebe; Mt: Mtilizi;Ms:Msandile; Nam:Namuseba;Luk:Lukusuzi;Lkw:Lunkwankwa

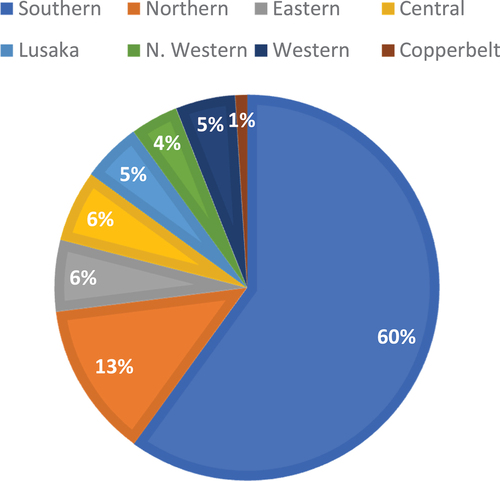

4. Production

The scarcity of recent information on cowpea in Zambia indicates that much work needs to be done on this important crop yet disregarded and overlooked. The world food programme and GIZ have on-going projects in different districts across Zambia (Richards & Bellack, Citation2016; WFP, Citation2020) to improve various aspects of the cowpea value chain. Cowpea productiivity in Zambia varies across the country, although yields are usually very low, <700–800 kg/ha (Munyinda, Citation2020). According to a 2004 supplemental survey (Mofya-Mukuka, Citation2021; Mofya-Mukuka & Musonda, Citation2016), cowpeas were grown in all Zambian provinces, although production was highly concentrated in a few areas (). The national outlook may have changed over the years, but the Southern Province is still the major cowpea producing region of the crop (WFP, Citation2020). The Southern Province is a drought prone area and this demonstrates that cowpea performs relatively well under drought conditions where most crops cannot grow well. In this region, cowpea production complements livestock production. More production figures across the country are needed to be able to provide a status of the crop and possible interventions to be developed accordingly.

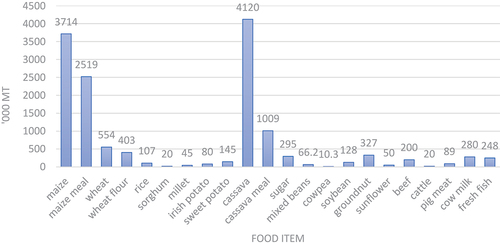

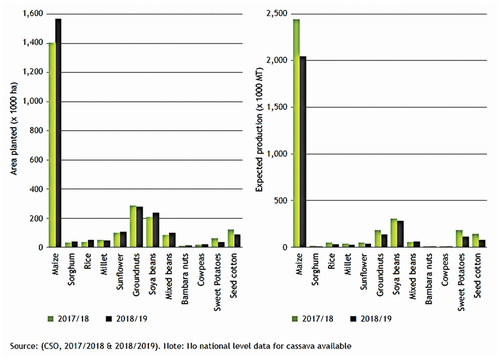

Most of the available data concentrates on beans and groundnuts (IAPRI, Citation2021a), with many instances where the production data for cowpea is pooled with that of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris; Harris, Citation2019). This is probably due to the low yields and use of cowpea among households. In one document by Mwanamwenge and Cook (Citation2019), cowpea production was the second to least (Bambara nuts) for two concurrent seasons, 2017/18 and 2018/19 (). The yields were among the lowest in the two seasons. The data revealed that cowpea had low production and yield in the country. This has been attributed to low market drivers (Mwanamwenge & Cook, Citation2019), inadequate processing capacity, value addition, and business models, and consumption and use (Ministry of Agriculture, Citation2012). Currently, there are a few companies purchasing cowpea grains in various regions, Good Nature (GNA) agro (Eastern Province), Community Markets for Conservation (COMACO) (Eastern Province), and WFP (Southern province). These companies are providing the needed cowpea market, which the farmers are not meeting in terms of supply. Additionally, other countries, such as Botswana, are also potential markets for cowpea producers. Moreover, the produce is usually bought at very low prices, attributed to low quality. Since no appropriate and established value addition processes are in place at the farmers’ community level and financial stresses, lead to sale of produce at low prices.

Figure 2. Area cultivated (1,000 hectares) and production of major crops (1,000 metric tonnes), 2017/2018 and 2018/2019.

During the production cycle, information on the availability of the crops after harvest is collected by the Ministry of Agriculture. This is to monitor the availability of all primary foods consumed by the majority of the population through the national Food Balance Sheet (FBS; NFNC/MoA, Citation2021). The nutritious FBS () is derived from the national FBS by showing food categories and types. In contrast, shows the available supply as of March 2020 (IAPRI, Citation2021a), based on the production and yields of the crops. Although it is encouraging to have cowpea appearing in the FBS, utilization is still low (), showing that there is indeed potential and opportunity for the crop at the national level.

Table 3. Nutrition food balance sheet food items in Zambia

Recent studies conducted through a participatory approach have had farmers indicate that among many constraints faced, they had limited knowledge of cowpea agronomic practices, which was associated with low production and productivity (; Nkhoma et al., Citation2020a; Mwanamwenge & Cook, Citation2019; IAPRI, Citation2021b). The constraint could be perceived two-fold; there being insufficient knowledge on practices that are supposed to be used in farmer fields, or limited information dissemination (via extension systems). Additionally, the lack of improved seed topped the list, suggesting the urgent need for awareness creation on available varieties. To improve seed availability, private and public engagements is encouraged, and engagement of the private and public institutions, as well as use of community seed banks to increase seed multiplication especially among rural communities.

Table 4. Farmer identified constraints in cowpea production

5. Agronomic practices (abiotic considerations)

A look at the available information on cowpea agronomy and production practices suggest sufficient knowledge in the growing and production of cowpea. Recent cowpea growing guides (ZAS, Citation2019) cover a broad range of topics through the production system of cowpea in Zambia. The crop performs well in hotter and drier parts of Zambia, replacing the common bean as a food crop for grain and leaf in those areas. Thus, the suggestion that the Southern province is likely to be still the higher production province and user of the crop is corroborated. Other provinces, such as Eastern and Central provinces, would be good growing locations. The optimum sowing times are December to January. Optimum time sown plants tend to have elongated internodes, more vegetative and have a higher yield than those sown at the very early (ZAS, Citation2019). This is attributable to temperature changes as well as rainfall. The right growing conditions, trigger the production of appropriate hormonal responses to result in phenotypic responses useful for plant growth.

Some cowpea varieties also have some tolerance for waterlogging (Oloruna et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, well-distributed rain is still crucial for the normal growth and development of cowpeas. The frequency and unreliability of rainfall pose problems to cowpea growth in Zambia. In some areas, the frequency of rain is too high, resulting in flooding, while in some other areas, it is so unreliable that moisture conservation and/or loss remain important for crop production. Cowpeas utilizes soil moisture efficiently and are more drought-tolerant than groundnuts and soya beans. In areas where annual rainfall is high (Northern province), cowpeas could be planted at a time to coincide with the peak period of rainfall during the vegetative phase or flowering stage so that pod-drying could take place during dry weather. Adequate rainfall is very important during the flowering/podding stage. Cowpeas react to severe moisture stress by limiting growth (especially leaf growth) and reducing leaf area by changing leaf orientation and closing the stomata.

In terms of soil preference, cowpeas are grown on a wide range of soils but perform better in sandy loam soils, which are less restrictive to root growth. This adaptation to lighter soils is coupled with drought tolerance through reduced leaf growth, less water loss through stomata, and leaf movement to reduce light and heat load under stress. Cowpeas thrive in well-drained soil and less on heavy soils. Additionally, low soil fertility does not deter the crop as it thrives, making it one of the most resilient legume crops suitable for Zambia’s low input and water-limited production systems (Nkhoma et al., Citation2020a).

Cowpea is unique compared to soybean; for example, it has the presence of nodular bacteria specific to cowpea (Bradyrhizobium spp). This characteristic makes it suitable for cultivation in the hot, marginal cropping areas of Southern Africa and the cooler, higher rainfall areas (DPP/ARC, Citation2011). Additionally, the bacteria help fix 70 to 350 kg/ha of atmospheric nitrogen. Some 40 to 80 kg of this is deposited into soils as a natural mineral nitrogen source contributing to soil (Sindhu et al., Citation2019). The crop requires a soil pH of between 5.6 and 6.0. Optimum soil pH and moderate temperatures favor bacterial survival and nodulation (Marsh et al., Citation2006) and improve cowpea crop performance through high N2 fixation. Nodulation potential of the crop is mostly achieved due to poor soil phosphorous fertility. The crop only fixes atmospheric nitrogen when there is sufficient plant available P in the soil.

Based on the information presented, there is sufficient available knowledge on optimum growing conditions and practices within the country. Therefore, extension services (public and private) need to package this information for dissemination to the farmers. Poor institutional linkages in outreach and promotion were reported by Chisanga et al. (Citation2017). It is recommended that more information and extension service interaction with other ministries (Ministry of Health (MOH) and Ministry of Education (MOE)), farmers and public/private organizations should occur. Additionally, harmonization among the actors in the value chain in the messages delivered to the farmer is required. To ensure there is no miscommunication and/or misunderstanding among the farmers, and as a means not to replicate efforts and focus on key information.

6. Biotic production constraints: pests and diseases

Insect pests are the most critical constraints to cowpea production because each phase attracts several insect pests. Cowpea is very attractive to insects (Dingha, Citation2021) due to the biochemical signals that the plant produces. The main pests during the growing season are pod sucking bugs (Riptortus spp., Nezara viridula, and Acantomia sp.), aphis (Aphis fabae, Aphis craccivora), blister beetle (Mylabris spp.), and pod borer (Maruca vitrata; Tembo et al., Citation2017). However, the bruchid weevil (mainly Callosobruchus maculatus) is the leading pest during growing and storage (Tembo et al., Citation2017).

Apart from insect pests, the most important disease of cowpea is stem rot caused by Phytophthora vignae. This disease frequently occurs in wetter areas and heavier soils that may become waterlogged. Bacterial canker, bacterial blight (Xanthomonas vignicola) causes severe damage to cowpeas, while the most frequent virus encountered is the aphid-borne mosaic virus (CabMV). Fungal diseases, are Fusarium wilt, Cercospora leaf spot, rust and powdery mildew. Cowpea is susceptible to nematodes and should not be planted consecutively on the same land. No variety in Zambia () is tolerant to key pests and diseases. Research is underway to identify promising tolerant genotypes for insects and diseases at UNZA and ZARI. This is because chemical control is costly, particularly for small-scale farmers and is not sustainable (FAO & IIBC, Citation1992). There is still a need for continued breeding efforts for cowpea given the evolution of the pathogens that cause the major diseases of cowpea and also the possible emergence of new biotypes of the cowpea pests. These continued breeding efforts are also needed to develop varieties that are more resilient to climate change.

Parasitic weeds such as Striga gesnerioides (Willd.) and Vatke and Alectra vogelii (Benth.) affect cowpea production (Horn et al., Citation2020). Weeds have been reported as a dominant constraint to production by the farmers in Zambia (Chisanga et al., Citation2017; Nkhoma et al., Citation2020a). Striga gesnerioides and Alectra spp. are the principal parasitic weeds attacking cowpeas in Zambia. The most common Striga species pest to cowpea is S. gesnerioides (Jamil et al., Citation2021). There is limited research in this area. As a result, farmers are advised to improve soil fertility where this weed is a problem by using manure. Striga finds an ideal environment for its proliferation with soils low in organic matter and soil biological activity (Ayongwa et al., Citation2011).

7. Pre-Harvest to harvest handling

Finally, in most cases, the harvesting of cowpea coincides with the onset of the dry season, when the dry pods can remain about a week awaiting harvesting without spoilage. However, dry pods are not left in the field longer than 2 weeks after full pod maturity to avoid pest infestation or shattering. Most smallholder farmers are encouraged to harvest with care at the appropriate moisture content (16%) so that there are limited injuries to the grain. Most of the small-scale farmers in Zambia harvest the crop manualy by hand and sundried. At time of harvest, storage facilities should have been prepared and cleaned, which does not happen mostly and these tend to excercabate pre-harvest mismanagement (ARC, Citation2021).

8. PPost-Harvest handlings

The post-harvest handling section covers cowpea shelling, storage and marketing, processing and utilization. Breakages usually occur during the shelling as many farmers hit the cowpea so that separates from its pods. Local seed companies will want the seed cleaned and bagged, while others like the Namibian markets will take the grain in bulk and clean it themselves, at a moisture content of 12%. Local off-takers are encouraged to train farmers on proper harvest methods to reduce damage levels. Grading begins just after harvest and shelling, with grain graded for color, size, insect damage, and firmness. The fresh, tender leaves are usually picked by the women and youth and sold in the local markets. Furthermore, the leaves are dried to store for the dry season, usually, after steaming. Alternatively, they are sun-dried, for 1 to 3 days. With these methods, storage for up to a year is possible because dried and cooked leaves are not damaged to the same extent by insects as dried grains. Excessive losses of Beta carotene, vitamin C, and lysine, amino acid often occur in sun-dried leaves (Ndawula et al., Citation2004). However, minimal cooking can reduce these, followed by drying in the shade. Not many studies have been conducted in this area of preservation. Innovations of improved on-farm storage mechanisms and structures are necessary within the country.

8.1. Storage

Smallholder farmers in Zambia do not have the proper-stage storage facilities and as such most of the crop deteriorates, and complete crop loss is reported due to insect pest damage (Damiri et al., Citation2013; Tembo et al., Citation2017), especially if it is being stored for an extended period. Most storage facilities are not well aerated, and bagged grains are placed on the ground, a breeding ground for attack by pests and rodents. This identifies another key challenge that needs to be addressed: losses mainly caused by financial, managerial and technical constraints in harvesting and handling techniques and storage and cooling facilities. Several studies are being carried out on varieties tolerant to storage pests (Siyunda et al., Citation2022), identifying technologies and methods that would help reduce the losses, such as using hermetic technology commonly known as PICS bags. Hermetic technology refers to the process of storing respiring products—usually durable crops with low moisture content, such as dry pulses, seeds, or grains—in sealed, airtight, or semi-airtight containment systems (Dijkink et al., Citation2022). Implementing organizations (e.g., GIZ and MoA) have developed training modules for postharvest management and integrated them into the curricula of farmer field schools and advertised on interactive radio shows, particularly in Eastern province. By introducing and demonstrating innovative techniques and methods in postharvest processes, producers can be trained and, at the same time, made aware of how to avoid losses.

8.2. Marketing, Processing, and Utilization

Several studies carried out under the Pulse Value Chain initiative, conducted from 2011 to 2015 in Zambia (Amanor-Boadu et al., Citation2015), as well as the Cowpea Collaborative Research Support Programme (2001; Singh, Citation2004), tackled a number of cowpea marketing components. Market participation was an important variable in transforming subsistence cowpea into commercial crops to help address poverty and income challenges that confront many smallholder producers (Moono, Citation2015). Profitability was associated with location, with the Southern province as the most profitable region (Mtchotsa, Citation2014). This scenario might have changed over the years, because of the recent increase in the production and use of cowpea and shows that there is improved demand for cowpea through GNA and COMACO purshases, with more potential for business from marketers and processors (IAPRI, Citation2021a). Additionally, the Northern province has a fair cowpea production (Nkhoma et al., Citation2020a). It would thus indicate that many households produce their own consumption and generally do not buy.

Other studies looked at the profitability of producing cowpea (Zulu et al., Citation2011), supply chain participation in the cowpea value chain (Ngoma et al., Citation2011) and cowpea producers’ choice of marketing channels (Mzyece, Citation2011). Zulu et al. (2011), reported that cowpea was potentially a profitable crop since most of the farmers that grew cowpeas were found to have positive gross margins. The study results further showed that 79% of the farmers produced cowpea, but few farmers (21%) sold their cowpeas. Thus, few participated in the market, which could be due to the lack of market and unattractive prices. Most cowpea is supplied to local markets, such as Soweto, and only 6% had existing contracts with buyers (Mtchotsa, Citation2011). Market opportunities for the crop need to be explored by the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), development organizations and individuals.

In Zambia today, various seed companies, notably GNA and Afriseed, are key in cowpea seed development and as markets (out-grower schemes), dealing with over 500,000 farmers and delivering country wide. Good Nature Agro provides cowpea seed to farmers in the Eastern province with technical extension and advice for improved production. After harvest, the farmers pay for the seed loan with seed (150%) and Good Nature Agro buys the rest of the seeds at a premium (K12/kg ≈ $0.67), package and sell the seed on the market. Furthermore, companies such as COMACO purchase cowpea grain from the farmers at competitive prices, and sells most of it while the rest is processed into food products such as a cowpea snack (CP snack for children) under their “Its’Wild” brand of products (). The seed multiplication for cowpea under COMACO is just commencing.

Cowpea is used both as a vegetable and grain in Zambia (Fanta Fhi, Citation2017). Cowpea leaves are also an important component of the market, where their quality, taste, and color should be maintained. Cowpea leaves are sold and consumed in most African countries, such as Zambia, South Africa, Ghana, Mali, Benin, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi (DPP/ARC, Citation2011). The semi-spreading varieties are suitable for use as a vegetable. Fresh leaves and growth points are often picked and eaten the same way as swiss chard or bean leaves. Dried leaves are preserved and eaten as a meat substitute (ZAS, Citation2019). In many localities across the provinces, cowpea leaves are harvested fresh as a vegetable alone or for peanut soup preparation or cured for future use during the cold dry season when there is no rain to sustain the crop production. Cowpea is commonly consumed as a dried grain in Zambia. It may also be cooked together with other vegetables to make a thick soup or ground into a meal or paste.

Additionally, in the Southern province, the dried grain is boiled and mixed with boiled maize grains (dried) and consumed. The use of fresh (green) cowpea seeds as a seed vegetable provides an inexpensive source of protein in the diet (Carneiro da Silva et al., Citation2019). Similarly, fresh, immature pods may be boiled as a vegetable. The green pod is rarely consumed in Zambia, nor are the grains consumed fresh.

It is envisaged that cowpea meals can be served with various popular maize meals, custard, bread, pap, and rice in Zambia when production is increased, and utilization awareness improves. There are multiple products that the small-scale farmers make in their homes, such as fritters, sausages, and biscuits (CUTS and WFP, Citation2018) but no company has formalized or commercialized any of these products. The trading of seeds and processed foods provide both urban and rural areas with opportunities to earn regular income. A local company (Sylva Food Solutions) purchases fresh leaves from small-scale farmers, sun dries the cowpea leaves (kachesha in the local language), packs them and sells them in retail stores (that serves the urban communities; ).

8.3. Photo credit: sylva food solutions

In addition, information on consumer preferences is vital for informing various actors along the value chain, such as plant breeders, marketers, and processors. Consumer preferences for taste, seed size, seed coat, and eye colors vary from place to place and affect food use (Table 3.3). For example, Ghanaian consumers pay a premium for black-eyed, whereas those in Cameroon discount black-eye. The most common seed coat color preference is white, but consumers prefer red, brown, or mottled grains in some areas. Up to nine different varieties may be on sale in a single domestic market (Ishikawa et al., Citation2019). In Brazil, the commercial varieties include Smooth White, Rough White, Smooth Brown, Evergreen, and Crowder (Martey et al., Citation2021). In Zambia, very little is documented on cowpea’s farmer and consumer preferences; neither is cowpea being marketed at premium places, such as hotels or eating places. Consumer preferences were documented for a cowpea-maize snack (Alamu et al., Citation2021) and a cassava-cowpea snack (Alamu et al., Citation2021), providing valuable information on critical end-user traits that must be considered at various value chain stages. However, much more still needs to be done in many provinces across Zambia and with more food product types, presenting opportunities that business entities can take up and promote. The MoA working together with MoH, would promote the crop as essential for nutrition, particularly for women and children (Ministry of Health Zambia, Citation2006).

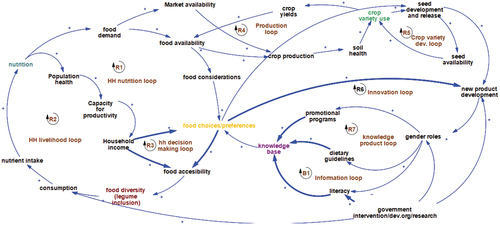

A food systems model analyses focusing on cowpea was created as shown in to have an overall perception of the review. The feedback loop presentation generated in Vensim® software illustrates the interactions of various processes and actors around cowpea’ value chain within the food system. The figure shows the importance of the end-user needs and requirements as they affect and connect with all other operations in the system. The model highlights that cowpea systems just like any other crop, are complex and inter-connected. It includes various key components, such as choices which affect consumer nutrient intake, food demand, market availability, also affecting cowpea production and seed development. At each point of the model, information is being generated into a knowledge outputs, feeding back into the loops to ensure improved liveihoods, nutrition, seed and crop production, plus innovations development. The system operates at optimum when there is interaction among the stakeholders within (researchers, consumers, producers, processors, marketers, government departments, NGO’s) and external (development organizations) to the system.

The developed model depicts the various areas of importance in cowpea development highlighted in this document, with their interactions and associations. The outstanding areas are nutrition, food diversity, choices, markets, production, seed, product development, information, knowledge development and its’ provision, prevailing policy environment for effective implementation and user uptake.

9. Conclusions

Cowpea is definitely an essential crop in Zambia, although known as a poor man’s crop, it has a place at all levels of the Zambian society (rich or poor). As such, messages on cowpea should be adapted to remove the poverty perception in them but show that the production and use of the crop could lead to improved livelihoods and well-being. The proactive implementation of critical hotspot areas along the value chain with key stakeholders spearheading the process and offering checks and balances is needed. It is recommended that cowpea be part of the government’s farmer support programs (as it is for maize). Furthermore, concerted efforts to expand the cowpea industry through price policies, such as high floor prices, are required to cushion farmers as they trade and foster its market. A strong private sector presence and active participation in the production and marketing is necessary. Additionally, deliberate policies to encourage market and processor-oriented actors to participate in marketing and using the crop as part of value addition would also create a demand and a positive ripple effect across the food system.

The local research has dedicated the bulk of studies toward high yielding cowpea cultivar and germplasm development. However, studies on other important traits and improved methods of variety development that are vital to cowpea research programs should be undertaken. Breeding efforts should be focused on climate resilience in its entirety, on pests, disease, water (drought tolerance) and nutrient use efficiency. End user preferences should also be a basis of variety selection to meet their needs. Investment in the commercialization of the already developed seed varieties is necessary to unlocking a lot of potential in the varieties. Other industrial uses of cowpeas need to be identified and look at potential markets that would boost production, consumption and use. This could result in increased demand, leading to increased price incentives for producer market participation. This will in turn also improve the accessibility and availability of cowpea seed and grain.

The extension services in the Ministry of Agriculture with other institutions, such as the central statistical office (CSO), Agricultural Marketing Information Centre (AMIC), MoE and MoH, should focus on strengthening capacities on improved cowpea production and nutrition practices to increase cowpea productivity to ensure up to date information on the crop. Public-private partnerships should develop appropriate, affordable, and simple cowpea farming and utilisation technologies. Accessibility and use of these simple technologies would improve supply chain participation. Ultimately, cowpea is indeed a crop worth investment and promotion in Zambia.

Acknowledgements

The review is motivated by the research work being undertaken by the fellow at the University of Zambia, with financial support from Carnegie Cooperation of New York (CCNY) through the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM); and the Research Excellence Project funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) under the partnership between the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alamu, E. O., Olaniyan, B., & Maziya-Dixon, B. (2021). Diversifying the utilization of maize at household level in Zambia : quality and consumer preferences of. Foods, 10(4), 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040750

- Amanor-Boadu, V., Featherstone, A., Mwiinga, M., Priscilla, H., Dalton, T., & Yesuf, M. (2015). Pulse Value Chain Initiative - Zambia (PVCI-Z) (pp. 3–18). USA: Kansas State University. https://www.canr.msu.edu/legumelab/uploads/files/ksu-1tech.progrptfy11final.pdf

- Pregelj, L., Ed. ARC. 2021. of excellence for integrative legume what are legumes ? %0Awww.cilr.uq.edu.au

- Awika, J., Rooney, L., Singh, B. B., Shindano, J., Muimui, K., & Minnaar, A. (2011). Increasing utilization of cowpeas to promote health and food security in Africa (pp. 4–8). USA: Texas A&M University. http://crsps.net/resource/increasing-utilization-of-cowpeas-to-promote-health-and-food-security-in-africa/

- Ayongwa, G. C., Stomph, T. J., Belder, P., Leffelaar, P. A., & Kuyper, T. W. (2011). Organic matter and seed survival of Striga hermonthica - mechanisms for seed depletion in the soil. Crop Protection, 30 (12), 1594–1600. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2011.08.012

- Boukar, O., Fatokun, C. A., Huynh, B. L., Roberts, P. A., & Close, T. J. (2016). Genomic tools in cowpea breeding programs: status and perspectives. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7(June 2016), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00757

- Carneiro da Silva, A., da Costa Santos, D., Lopes Teixeira Junior, D., Bento da Silva, P., Cavalcante Dos Santos, R., & Siviero, A. (2019). Cowpea: A strategic legume species for food security and health. In Jose C. Jimenez-Lopez and Alfonso Clemente (Eds.), Legume seed nutraceutical research (pp. 10). IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.79006

- Chilufya, & Mulendema. (2019). Beyond maize - Exploring agricultural diversification in Zambia from different perspectives (pp. 1–7). IIED/HIVOS. https://www.iied.org/beyond-maize-exploring-agricultural-diversification-zambia

- Chisanga, K., Kafwamfwa, N., Hamazakaza, P., Mwila, M., Sinyangwe, J., & Lungu, O. (2017). Farmer perceptions of conservation agriculture in maize - legume systems for small-holder farmers in Sub Saharan Africa - a beneficiary perspective in Zambia. International Journal of Horticulture, Agriculture and Food Science, 1(3), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijhaf.1.3.3

- CUTS and WFP. (2018). Identifying food consumption patterns in Lusaka. In CUTS (pp. 9–20). CUTS International. https://cuts-lusaka.org/pdf/Report-Identifying_food_consumption_Patters_in_Lusaka.pdf

- Damiri, B. V., Al-Shahwan, I. M., Al-Saleh, M. A., Abdalla, O. A., & Amer, M. A. (2013). Identification and characterization of Cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus isolates in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Plant Pathology, 95(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.4454/JPP.V95I1.019

- Dijkink, B., Broeze, J., & Vollebregt, M. (2022). Hermetic Bags for the Storage of Maize: Perspectives on Economics, Food Security and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Different Sub-Saharan African Countries. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6(January). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.767089

- Dingha, B. N., Omaliko, P. C., Amoah, B. A., Jackai, L. E., & Shrestha, D. (2021). Evaluation of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) in an intercropping system as pollinator enhancer for increased crop yield. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179612

- DPP/ARC. (2011). Production guidelines for Cowpeas (D. P. Production, Ed.;1st, Vol. 1) Directorate Agricultural Information Services. https://rc.agric.za/arc-gci/Fact_Sheets_Library/Cowpea-Production_guidelines_for_cowpea.pdf

- Drivers of trader participation in bean and cowpea marketing by Lydia mtchotsa. (2009).

- Fanta Fhi, U. (2017). Reducing Malnutrition in Zambia: Estimates to Support Nutrition Advocacy (Zambia nutrition profiles) (pp. 2–3). Ministry of Health/National Food and Nutrition Commission. www.nfnc.org.zm

- FAO. (1992). Bemisia tabaci: A literature survey (IIBC, M. J. W. Cock, Eds.; 1st, Vol. 590).

- FAO. (2016). Role of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Sustainable Food Systems and Nutrition (Issue COAG/2016/INF/5, pp. 1–5). https://www.fao.org/3/mr252e/mr252e.pdf

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, W. and W. (2017). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World; Building resilience for peace and food security (pp. 132–134). https://www.fao.org/3/i7787e/i7787e.pdf

- Gerrano, A. S., Jansen van Rensburg, W. S., Venter, S. L., Shargie, N. G., Amelework, B. A., Shimelis, H. A., & Labuschagne, M. T. (2019). Selection of cowpea genotypes based on grain mineral and total protein content. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B: Soil and Plant Science, 69(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2018.1520290

- Gondwe, T. M., Alamu, E. O., Mdziniso, P., & Maziya Dixon, B. (2019). Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp) for food security: An evaluation of end-user traits of improved varieties in Swaziland. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 15991. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52360-w

- Hachibamba, T., Dykes, L., Awika, J., Minnaar, A., & Duodu, K. G. (2013). Effect of simulated gastrointestinal digestion on phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of cooked cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) varieties. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 48(12), 2638–2649. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.12260

- Hamududu, B. H., & Ngoma, H. (2019). Impacts of climate change on water availability in Zambia: Implications of irrigation development. Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy, 3(August), 25–34. https://www.canr.msu.edu/fsp/publications/

- Harris, M. (2019). SuStainable dietS for all (Hivos, Ed.; 2nd ed.). hivos. https://hivos.org/assets/2020/09/ETE-Sustainable-Diets-for-All.pdf

- Horn, L. N. (2016). Breeding cowpea (vigna unguiculata [L] walp) for improved yield and related traits using gamma irradiation by Lydia ndinelao horn Bsc agriculture (crop science), MSc Biodiversity Management and Research (University of Namibia) A thesis submitted (Issue October). ACCI. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10413/15037/Horn_Lydia_N_2017.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1

- Horn, L. N., & Shimelis, H. (2020). Production constraints and breeding approaches for cowpea improvement for drought prone agro-ecologies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Annals of Agricultural Sciences, 65(1), 83–91. Faculty of Agriculture, Ain-Shams University. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aoas.2020.03.002

- Hove, H., & Bakker, S. (2020). Scaling sustainable nutrition for all (SN4A) in Zambia : report community mapping. Wageningen Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen University & Research. Report WCDI-20-110. Wageningen. https://doi.org/10.18174/528812

- IAPRI. (2021a). 2020 Zambia food security and nutrition. 40. https://www.iapri.org.zm/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020_fns_report.pdf

- IAPRI. (2021b). 83368089_value chain analysis and stakeholder mapping IAPRI draft report-23Feb2021 (pp. 26–55).

- Ishikawa, H., Drabo, I., Joseph, B. B., Muranaka, S., Fatokun, C., & Boukar, O. (2019). Characteristics of farmers’ selection criteria for cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) varieties differ between north and south regions of Burkina Faso. Experimental Agriculture, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S001447971900019X

- Jamil, M., Kountche, B. A., & Al-Babili, S. (2021). Current progress in Striga management. Plant Physiology, 185(4), 1339–1352. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiab040

- Kaluba, P., Verbist, K. M. J., Cornelis, W. M., & Van Ranst, E. (2017). Spatial mapping of drought in Zambia using regional frequency analysis. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 62(11), 1825–1839. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2017.1343475

- Kirkhouse trust. (2022). Genetic resistance using marker-assisted and conventional breeding. https://www.kirkhousetrust.org/zambia

- Maria Figueira Gomes, A., Nhantumbo, N., Ferreira-Pinto, M., Massinga, R., Ramalho, C., & Ribeiro-Barros, A. (2019). Breeding elite cowpea [vigna unguiculata (L.) walp] varieties for improved food security and income in Africa: opportunities and challenges. Legume Crops - Characterization and Breeding for Improved Food Security, 6(3), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.84985

- Marinda, P. A., Genschick, S., Khayeka-Wandabwa, C., Kiwanuka-Lubinda, R., Thilsted, S. H., & Wieringa, F. (2018). Dietary diversity determinants and contribution of fish to maternal and under five nutritional status in Zambia. PLoS ONE, 13(9), e0204009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204009

- Marsh, L. E., Baptiste, R., Marsh, D. B., Trinklein, D., & Kremer, R. J. (2006). Temperature effects on Bradyrhizobium spp. growth and symbiotic effectiveness with pigeonpea and cowpea. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 29(2), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904160500476921

- Martey, E., Etwire, P. M., Adogoba, D. S., & Tengey, T. K. (2021). Farmers’ preferences for climate-smart cowpea varieties: Implications for crop breeding programmes. Climate and Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1889949

- Mbuma, N. W., Gerrano, A. S., Lebaka, N., Mofokeng, A., & Labuschagne, M. (2021). The evaluation of a Southern African cowpea germplasm collection for seed yield and yield components. Crop Science, 61(1), 466–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20336

- MFND. (2022). Eighth National Development Plan 2022-2026. 8th-NDP-2022–2026. https://www.nydc.gov.zm

- Ministry of Agriculture. 2012. National Agricultural Policy.

- Ministry of Health Zambia. (2006). Memorandum of understanding (Mou) between the government of the Republic of Zambia/Ministry of Health and cooperating partners (issue April). Ministry of health, Government Printers.

- Mofya-Mukuka, R., & Musonda, M. (2016). The status of hunger and malnutrition in Zambia: A review of methods and indicators (Vol. 5). International Agricultural Policy and Research Institute (IAPRI). http://www.iapri.org.zm

- Mofya-Mukuka, R. (2021). Monitoring Household Food Security and Nutrition during COVID-19. In B. (Ed.), Scaling up Nutrition National Conferenceational Conference (Issue March). NFNC. https://www.nfnc.org.zm/download/monitoring-household-food-security-and-nutrition-during-covid-19-presenter-rhoda-mofya-mukuka-iapri/

- Moono, L. (2015). An analysis of factors influencing market participation among samllholder farmers (Issue April). University of Zambia.

- Mtchotsa, L. (2014). Drivers of trader participation in bean and cowpea marketing (pp. 20–45). University of Zambia. https://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/16986/LydiaMtchotsa2014.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Mtchotsa, L. (2014). Drivers of trader participation in bean and cowpea marketing. 20–45. https://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2097/16986/LydiaMtchotsa2014.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Mulenga, B. P., Kabisa, M., Chapoto, A., & Muyobela, T. (2020). Agriculture status report 2020 Zambia (pp. 29–32). IAPRI. https://www.iapri.org.zm/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020_asr.pdf

- Mulungu, K., Tembo, G., Bett, H., & Ngoma, H. (2021). Climate change and crop yields in Zambia: Historical effects and future projections. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(8), 11859–11880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01146-6

- Munyinda, K. L. (2020). Mutation led cowpea breeding. Zambia Daily Mail. http://www.daily-mail.co.zm/unza-develops-special-cowpeas-varieties/

- Munyiri, S. (2020). Opportunities for quality seed production and diffusion through integration of the informal systems in sub-saharan Africa. In João Silva Dias, (Eds.),Prime Archives in Agricultural Research, 1–20. Hyderabad, India: Vide Leaf. https://doi.org/10.37247/paar.1.2020.19

- Mwanamwenge, M., & Cook, S. (2019). Beyond maize - Exploring agricultural diversification in Zambia from different perspectives. IIED/HIVOS. https://pubs.iied.org/g04422

- Mzyece, N. (2011). Factors affecting cowpea marketing and supply. [University of Zambia]. http://dspace.unza.zm/bitstream/handle/123456789/4527/AGNESSMZYECE0001.PDF?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Ndawula, J., Kabasa, J. D., & Byaruhanga, Y. B. (2004). Alterations in fruit and vegetable beta-carotene and vitamin C content caused by open-sun drying, visqueen-covered and polyethylene-covered solar-dryers. African Health Sciences, 4(2), 125–130.

- NFNC/MoA. (2021). Zambia food-based dietary guidelines technical recommendations 2021 (K. Zeravica, Ed.; 1st), FAO/EU. https://www.fao.org/3/cb7674en/cb7674en.pdf

- Ngoma, E. (2011). Supply Chain Participation of Cowpea producers in Zambia. Thesis. pp21–33. University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia. http://dspace.unza.zm/bitstream/handle/123456789/4528/NgomaE20110001.PDF?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Ngoma, H., Lupiya, P., Kabisa, M., & Hartley, F. (2021). Impacts of climate change on agriculture and household welfare in Zambia: An economy-wide analysis. Climatic Change, 167(55), 3–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03168-z

- Nkhoma, N. (2013). Stability of Yield and Antioxidant Content of Selected Advancedd Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L] Walp.) Mutation Derived Lines. [University of Zambia]. http://dspace.unza.zm/bitstream/handle/123456789/3413/Nkhoma%27sDissertation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Nkhoma, N., Shimelis, H., Laing, M. D., Shayanowako, A., & Mathew, I. (2020a). Assessing the genetic diversity of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.] germplasm collections using phenotypic traits and SNP markers. BMC Genetics, 21(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-020-00914-7

- Nkhoma, N. (2021). Genetic Improvement of Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L .) Walp .] for Grain Yield and Yield Components in Zambia. Kwa-Zulu Natal. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/19478/Nkhoma_Nelia_2020.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Omomowo, O. I., & Babalola, O. O. (2021). Constraints and Prospects of Improving Cowpea Productivity to Ensure Food, Nutritional Security and Environmental Sustainability. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12(October). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.751731

- Ousmane, B. Fatokun C. A., Togola A., Ongom P., & K. Lopez. (2020). Cowpea receives more research support. In CGIAR Research Program on Grain Legumes and Dryland Cereals (GLDC) GLDC newsletter (pp. 1–2). http://gldc.cgiar.org/cowpea-receives-more-research-support/

- Richards, K., & Bellack, S. (2016). Malnutrition in Zambia for the most vulnerable. London, UK: Save the Children. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/…/malnutrition_in_zambia_-_harnessing_socia

- Simunji, S., Munyinda, K. L., Lungu, O. I., Mweetwa, A. M., & Phiri, E. (2019). Evaluation of Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.Walp) Genotypes for Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Maize-cowpea Crop Rotation. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 8(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v8n1p82

- Sindhu, M., Kumar, A., Yadav, H., Chaudhary, D., Jaiwal, R., & Jaiwal, P. K. (2019). Current advances and future directions in genetic enhancement of a climate resilient food legume crop, cowpea (VIGNA unguiculata L. walp.). Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 139(3), 429–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-019-01695-3

- Singh, B. B., International institute of tropical agriculture., & world cowpea research conference (2nd: 1995: Accra, G. (2004). Advances in cowpea research. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture.

- Siyunda, A., Mwila, N., Mwala, M., & Kamfwa, K. (2022). Laboratory Screening of Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) Genotypes against Pulse Beetle , Callosobruchus maculatus (F .). Medicon Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, 2(3), 4–12.

- Tembo, L., Pungulani, L., Sohati, P. H., Mataa, J. C., & Munyinda, K. (2017). Resistance to callosobruchus maculatus developed via gamma radiation in cowpea. Journal of Agriculture and Crop, 3(8), 65–71. http://arpgweb.com/?ic=journal&journal=14&info=aims

- Tripp, R., Walker, D. J., Miti, F., Mukumbuta, S., & Zulu, M. S. (1998). Seed management by small-scale farmers in Zambia. A study of cowpea, groundnut and sorghum seed in the southern and western provinces (NRI Bulletin 76). University of Greenwich, Natural Resources Institute, UK. https://gala.gre.ac.uk/id/eprint/11101/1/Doc-0165.pdf

- WFP. (2020). Annual Country Report-Zambia. https://www.wfp.org/publications/world-food-programme-zambia-2020-annual-country-report-highlights

- Willis, C. (2020). Drought-Tolerant crops: IAEA and FAO help Zambia improve production and farmers’ income | IAEA. IAEA Office of Public Information and Communication. June.

- Zambia agricultural status report 2016. (2016). http://www.iapri.org.zm/images/TechnicalPapers/IAPRI-Booklet.pdf

- VRC, (Ed.), & ZARI. (2021). Variety book 2021 October 12 serialated (005). ZARI.

- ZAS. (2019). cowpea-production-guidelines-zas (Z. A. Society, Ed.; 1st), Zambia Agribusiness Society. https://zaszambia.wordpress.com/2019/06/14/cowpea-production-guidelines/#:~:text=In_Zambia_cowpea_is_mainly,substance_crop_for_home_use.&text=There_are_a_number_of,and_semi–erect_in_growth

- Zulu, E. (2011). Profitability of Cowpea Production in Zambia [University of Zambia]. http://crsps.net/wp-content/downloads/DryGrainPulses/Inventoried8.23/4-2011-12-172.pdf