Abstract

Human beings have battled with oxidative stress and its related illnesses such as inflammatory diseases, heart diseases, and even cancer for decades. Spices and herbs are known for their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that could mitigate oxidative stress. However, post-harvest loss of such spices make their production seasonal and solar drying could curtail this problem. Solar drying of ginger will add value and reduce post-harvest loss, yet consumer preference needs to be established. This study carried out a survey by administering semi-structured questionnaires to 398 willing respondents in the Accra metropolis to seek information on the knowledge of the health benefits and sicknesses that consumers had used ginger to treat as well as the acceptability of solar dried ginger locally. Respondents enumerated 22 illnesses in the category of anti-inflammatory disorders, stomach discomfort, weight loss, and an aphrodisiac which they had used ginger to cure. More than half of respondents (74.3%) had used ginger to cure upper respiratory infections with an almost unanimous response to the local production of dried ginger for all-year availability.

1. Introduction

In the tropics, staple foods are predominantly carbohydrate-based. These are generally bland tasting, and flavor development is achieved by the application of traditional fermentation technologies and/or the usage of spices to provide variety and zest (Swain et al., Citation2014). Ginger from the Zingiberaceae family has been utilized widely as a spice and medicine (Amoah et al., Citation2020). It has been used for the treatment of several illnesses and as prevention against many conditions, from upper respiratory infections to stomach disorders and inflammatory diseases (Kaushal et al., Citation2017; Mao et al., Citation2019; Si et al., Citation2018). It is also used as a flavoring agent in beverages and as a fragrance in soaps and cosmetics (Alam, Citation2013; Kaushal et al., Citation2017). As popular as it may be, its availability is seasonal in many growing areas. Ginger production in Ghana and many tropical areas is largely by smallholder farmers who sell them in the local markets with little or no processing or value addition. This causes a yearly cycle of a bumper harvest and a resultant glut that usually leads to huge post-harvest losses as with other fruits and vegetables (Kitinoja & Kader, Citation2015). There is a need to improve the efficiency of post-harvest handling, preservation, and/or value addition to realize the full benefits of the produce. Various drying methods such as ‘tray drying, convective hot air drying, freeze drying, heat pump dehumidified drying, microwave drying, and solar drying have been used in drying ginger worldwide (Amoah et al., Citation2020; Jayashree et al., Citation2014). In most developing countries, open-sun drying is used for the commercial processing of ginger especially in India and Nigeria that are among the three top producers and exporters of dried ginger (Deshmukh et al., Citation2014; Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics, Citation2019; Owureku-Asare et al., Citation2016).

In Ghana, sun drying has been the major drying method for most agricultural produce. A few reports have, however, associated sun-dried spices with pathogenic bacteria and toxigenic fungi (Amoah et al., Citation2020). Open-sun drying, however, has many disadvantages such as high microbial load, vast color changes to produce, and contamination by foreign matter such as sand and pieces of twigs and leaves from neighboring flora. Solar drying on the other hand could be a good alternative. Also, studies have shown that some solar dryers dry ginger faster than open-sun drying (Amoah et al., Citation2020). This may pose serious health implications to consumers of such open-sun dried spices. It is, therefore, necessary to determine cost-effective methods of producing high-quality dried ginger. In view of this, solar dryers could be a good and affordable alternative to conventional dryers given the relatively low energy (Deshmukh et al., Citation2014) cost. A survey by Kuwornu et al. (Citation2011), on the views of farmers’ willingness to pay for a solar dryer for food preservation, revealed that they would be willing to pay up to $100.00 for a solar dryer of 50 kg capacity. Though different types of solar dryers exist, the passive type that does not operate with electric energy could be ideal for most tropical communities that enjoy abundant sun energy (Owureku-Asare et al., Citation2016). Whilst solar drying might help reduce postharvest losses and improve the quality and safety of dried ginger, it is also important to understand consumer needs and preferences for ginger as well as their views on whether the dried ginger can be used for the same purposes as the fresh. Furthermore, the willingness of farmers to use solar dryers in adding value to ginger may not necessarily guarantee consumer acceptance of the solar-dried ginger product locally. Expectations of consumers of the dried product to have the same functions as the fresh ginger product is a very important factor that needs to be met. Several factors such as taste, texture, chemical residues (Korzen & Lassen, Citation2010), branding, labeling, packaging, price, and knowledge about the product’s relative importance (Mueller & Szolnoki, Citation2010) affect consumer choice of product. A study on Consumer knowledge, preference, and perceived quality of dried tomato products in Ghana showed that the majority of consumers will choose a well-packaged dried tomato product that has preserved its taste for convenience. Drying decreases volatile compounds and pungent principles of ginger and thereby affects the taste and aroma (Amoah et al., Citation2022; Jayasundara & Arampath, Citation2021) and different drying methods affect the final product differently.

This study thus focuses on consumer knowledge and derived health benefits of ginger, the functionality of both fresh and dried ginger, preferences, and quality of locally produced sliced dried ginger in Ghana.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study location

The Accra Metropolitan area (capital of Ghana) was chosen for the survey based on its cosmopolitan nature. Accra metropolitan area has residents from all parts of the country who consume ginger products (Latitude 5.614818 and longitude—0.205874 coordinates).

2.2. Method of data collection

The sampling process was a random one in which willing respondents were interviewed. In the Accra Metropolis, before the survey of a town, the houses were counted, and the tenth house on each count was chosen. One willing respondent was interviewed in each chosen house. A semi-structured questionnaire was developed and administered to the willing respondents. A sample size of 398 respondents was calculated based on the method described by Moore and McCabe (Citation1993), at a 5% margin of error. The questionnaire was composed of questions designed to evaluate consumers’ knowledge of the health benefits of ginger, the functionality of both fresh and dried ginger, and post-harvest losses. Furthermore, questions to assess consumer preference of quality attributes, dried ginger products, and processing methods were solicited. Again, preferences for ginger products and the basis for such choices were obtained from 52 market females included in the sample size of 398.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis were done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 22.0). Frequencies obtained for variables and significant associations were tested at p ≤ 0.05 using the Chi-square test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

Consumer responses to factors that affect their choice of food products such as gender, level of education, age, occupation, and marital status are shown in Table . In Ghana and Africa, decisions regarding the choice of ingredients for cooking are mostly made by females (Owureku-Asare et al., Citation2016). This was corroborated by this study as it recorded 82.2% females as against 17.8% male respondents who were willing to participate in the survey. More than half (65.1%) of the respondents were below or of the age of 35 years that is a reflection of the country’s young population. Huge portions of the respondents were Ghanaians which may pre-suppose that any inputs made to this study may reflect the food choices of the larger Ghanaian population. Consumers from all the 10 regions of birth in Ghana were represented with the majority from Greater Accra and Volta regions. These results indicated that a larger proportion of respondents were engaged in one form of employment or the other and can generate some financial resources or returns reflecting their capacity to make purchases.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

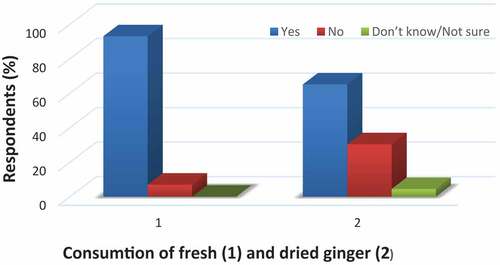

3.2. Uses and consumer opinion on the functionality/usage of both fresh and dried ginger

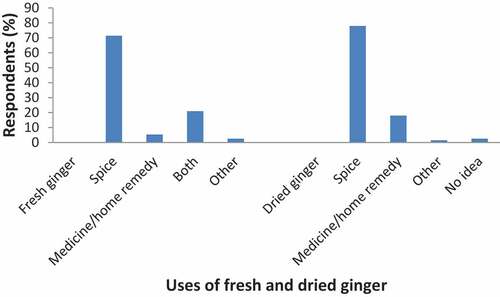

Figure shows that the majority of the respondents (93%) consume fresh ginger with 71.4% using it as a spice and 5.3% for medicinal purposes whilst 20.9% use it for both purposes. The results show that more than half of consumers are willing to use dried ginger if all production processes and quality concerns are addressed with less than 5% being indecisive. This is a positive indication for local production of dried ginger. The concern of the consumers with production processes and quality issues confirms that intrinsic factors including taste, texture, and chemical residues affect consumers’ choice of a product (Bernues & Corcoran, Citation2003; Chrea et al., Citation2011).

Figure 1. A Consumption of fresh ginger (1) (n = 370) and consumer willingness to patronize dried ginger products (2) (n = 259). B Uses of fresh (n = 370) and dried (n = 259) ginger. C Reasons for consuming dried ginger (n = 259). D Consumption pattern of fresh ginger and foods containing ginger (n = 370). Key: Often = 3–6 times in a week. Periodic = once a week

The importance of any product to a consumer is the ability of the product to fit its purpose. Even though the characteristics of dried ginger are somewhat different from that of fresh ginger due to the loss of some essential oils that affects the aroma and reduction of gingerol that affects the taste (Jayasundara & Arampath, Citation2021; Kaushal et al., Citation2017), the findings of this study indicate that dried ginger can be used for similar purposes or functions as the fresh ginger as shown in Figure . Apart from 2.5% of consumers who are indecisive and 1.5% who will use dried ginger for other purposes, the larger proportion will use dried ginger for a home remedy or as a spice according to the different responses just as the fresh ginger. The majority of respondents’ use of both fresh and dried ginger for its spicy property agrees with studies by Kumar (Citation2016) who stated that ginger is mostly used worldwide first for its spicy properties.

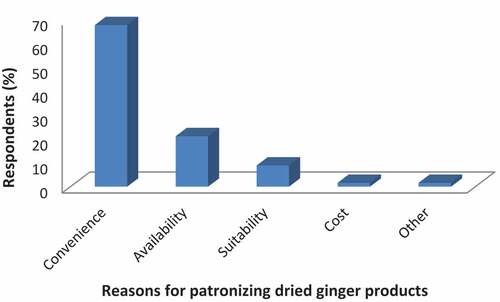

Choices of food products are made based on the price and knowledge about the product’s relative importance (Mueller & Szolnoki, Citation2010). More than half (67.6%) of respondents will use dried ginger based on convenience whilst 21.2% will use it for its availability (Figure ).

The majority of consumers may find the use of dried ginger convenient due to a reduction in processing time during culinary application as compared to the use of fresh ginger. Availability of fresh ginger all year round is not assured due to the lack of proper storage facilities and relatively low shelf-life stability as compared to dried ginger hence a high proportion of respondents choose dried ginger for its availability.

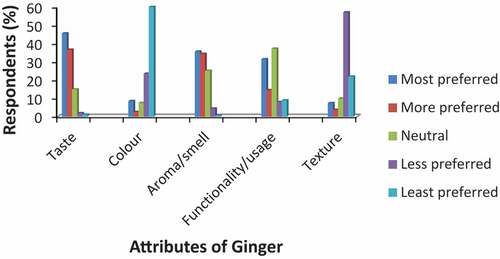

Figure shows the consumption pattern of ginger and frequency of consumption of foods containing ginger, respectively. Higher percentages of respondents consume ginger and foods containing ginger at least 3–6 days a week for either spicing their meals or for medicinal purposes. This makes ginger a very important commodity worth the attention for value addition in the country.

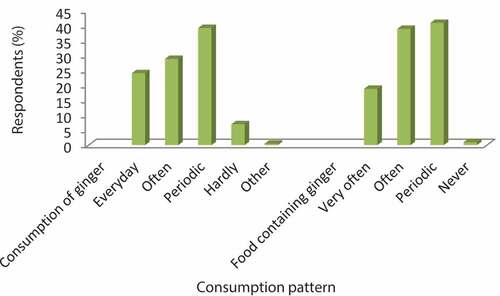

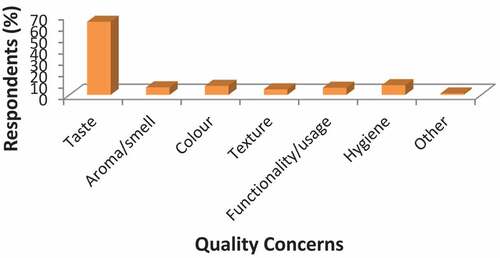

3.3. Consumer preference for quality attributes and familiarity with dried ginger

Consumer ranking of the desirable attributes of fresh ginger is shown in Figure . Five different desirable attributes of ginger, viz taste, aroma/smell, color, functionality/usage, and texture were analyzed in this survey. Respondents were asked to rank these attributes from 1 to 5 where 1 is most preferred and 5 is least preferred. The survey revealed that respondents would choose fresh ginger based on its taste and aroma/smell, as well as its fitness for purpose (functionality/usage) and not necessarily the color and texture.

The choice of quality attributes by respondents of fresh ginger is not unexpected since the two major properties of ginger are the taste and aroma attributed to phenolic pungent compounds and essential oil, respectively (Kaushal et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, studies show that drying, in general, reduces the main phenolic pungent property (gingerol) and the volatile essential oil (Amoah et al., Citation2022) implying the need for a drying system that will maintain these two critical attributes for dried ginger such as a solar dryer.

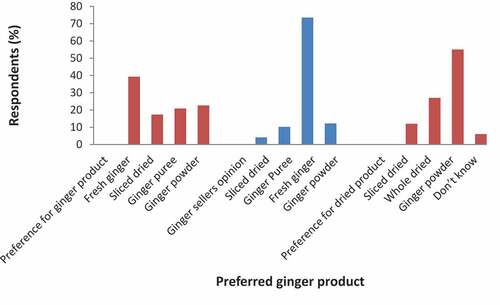

The majority of respondents will choose fresh ginger (39.3%) over dried ginger products as seen in Figure .

Figure 3. Consumer preferred ginger products (n = 389), ginger sellers’ opinion on consumer preferred ginger products (n = 52) and consumer preferred dried ginger product (n = 259).

Ginger powder was the next choice (22.6%) for consumers but the percentage of consumers choosing this over ginger puree or paste (20.8%) was not that momentous making the fresh ginger product the favorite choice. The reason could be that respondents have been traditionally inclined to fresh ginger (Prescott & Bell, Citation1995). The low response to dried sliced ginger (17.3%) relative to ginger powder could be because of the additional responsibility of milling it before use as most respondents will choose the dried ginger based on convenience (Figure ). The respondents’ choice of ginger products was corroborated by the spice sellers including ginger (Figure ). Consumer pattern of choice of ginger product was the same as indicated by the spice sellers. According to the 52 market sellers of various spices including ginger products, 73.5% of respondents will choose fresh ginger over the other ginger products basically for its fresh aroma and pungent taste. Owureku-Asare et al. (Citation2016), reported, that consumers preferred familiar products such as fresh tomatoes and canned tomatoes to cut dried tomatoes. Consumer choice of familiar products is due to traditional and cultural inclinations (Owureku-Asare et al., Citation2016; Prescott & Bell, Citation1995) and experience with usage of the product itself (Bernues & Corcoran, Citation2003). It is possible that the 26.0% of respondents unaware of the dry product might also patronize it if awareness is created and quality concerns addressed. When respondents were asked about their choice of dry ginger products (Figure ), powdered ginger (55%) was the first choice compared to whole dried ginger and dried sliced ginger. The reason for such a choice may be due to convenience. Some consumers (6.0%) are undecided concerning the use of dried ginger products. However, there is the potential that such consumers may use dried ginger when well presented. A large proportion (74%) of respondents were aware of the production of dried ginger slices and ginger powder on the Ghanaian market. Nevertheless, the number of respondents familiar with these products was slightly lesser than the respondents (63.8%) that were aware of its production (Table ).

Table 2. Consumer familiarity with dried ginger slices and powder

Even though 63.8% of respondents were familiar with dried ginger products, only 51.2% had used these products whilst 48.8% had not yet patronized dried ginger on the market (Table ). Out of 387 respondents, a little below half confirmed that they had quality concerns with the dried ginger products sold on the Ghanaian market. Respondents further stated these quality concerns as a change in taste, color, and smell whilst 6.3% alleged that dried ginger could not be used for the same function as fresh ginger (Figure ). Basically respondents’ concerns for not patronizing the dried ginger products were due more to intrinsic factors as asserted by Korzen and Lassen (Citation2010). About 8.5% of respondents out of 189 believed that there were hygienic issues with the dried ginger product that could be from contamination with stone/sand, plant debris, dead whole insect or dead insect parts, and/or microbes; this is more characteristic of the open sun-dried product (Amoah et al., Citation2020). It is possible that when these concerns are addressed by the use of an efficient alternative drying method such as a solar dryer which reduces the hygienic concerns, more respondents may patronize dried ginger products.

Processes employed to extend the shelf-life of a product affect the quality of the final product. In ascertaining the processes that consumers would use in extending the shelf-life of ginger, the majority would use drying whilst 16.1% and 16.4% will use freezing and refrigeration, respectively, (Table ). Furthermore, more than half of consumers would prefer to use the open-sun drying method (58.2%) with 23.9% and 6.0% using solar drying and oven drying, respectively. The higher percentage of consumers who will use open sun drying could be because it is the method they are most familiar with. It is worth noting that 23.9% of consumers will use solar drying; with education and awareness of the advantages of the solar dryer over the open-sun drying method, this percentage could increase. Few (1.3%) consumers would use freeze drying to preserve the fresh ginger (Table ). More than half of consumers will prefer to dry the ginger themselves probably because of the quality concerns they have whilst 43.3% will buy from the supermarket and open market. The percentage of consumers who will buy from the supermarket and open market is encouraging for farmers and industrialists who would venture into this business of locally drying ginger. Of the 43.3% of consumers who will purchase dried ginger from the market and supermarket/shop, 31.5% will purchase from the open market. This could be because products sold in open markets are less priced as compared to the same products in supermarkets or shops (Owureku-Asare et al., Citation2016).

Table 3. Consumer processes to extend shelf life of ginger and preferred source of ginger dried ginger

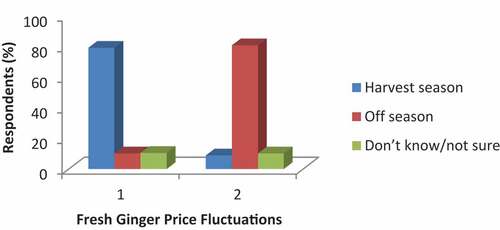

3.4. Price distribution of ginger and product acceptability

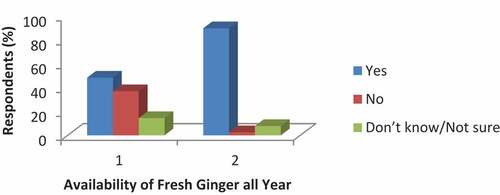

Post-harvest loss with horticultural products is a major problem worldwide especially in most African countries (Kitinoja & Kader, Citation2015) where farming is mostly on small-scale basis and the use of advanced technology for value addition is low. One means by which post-harvest losses are curtailed is by drying. Results of this study show that there is the availability of dried ginger products on the market; however, most of these are imported from Nigeria and China. The Ghanaian ginger farmer and processor can take advantage of the already existing market for dried ginger to curtail losses incurred from spoilage, lack of storage facilities, and value addition by the use of technologies such as solar drying to manage postharvest losses. Products such as ginger oil, oleoresin, ginger candy, ginger puree, dried ginger slices, and powder can be obtained from fresh ginger (Kaushal et al., Citation2017). However, in Africa and Ghana that experience abundant solar energy, ginger slices, and powder will be a more appropriate form of adding value to the fresh ginger to preserve the excess fresh produce. Consumers were aware of the unavailability of ginger all year round and the price fluctuations encountered (Figure ). More than 80% of consumers revealed that the price of fresh ginger on the market changes with time as the price is lowest (79.3%) during the peak production season (November and December) and highest (80.9%) during the off-season (July and August; Figure ); this calls for the preservation of local fresh ginger by solar drying.

Figure 5. Availability of ginger all year (1- availability of fresh ginger all year 2- price change with time) (n = 387). B Seasonal price fluctuation of fresh ginger (1 -least priced fresh ginger 2- highest priced fresh ginger) (n = 387).

In this study, 51.2% of consumers have already patronized the dried ginger on the market (Table ) and 65.1% are willing to use the product if all quality concerns are addressed (Figure ). The positive inclination of consumers to the use of locally dried ginger led to an almost unanimous response to the local production of dried ginger (97%; data not shown). The price of a product affects consumer choice (Korzen & Lassen, Citation2010). Even though a higher percentage of respondents (32%) were willing to pay quite a low amount of GHp 10–50 for 100 g of dried ginger, quite an appreciable number (20.7%) were also willing to purchase the dried ginger at a higher amount of more than GHC 2.0. This means that with proper education and quality concerns addressed, there could be a good market for locally dried ginger in the form of ginger powder using solar drying.

3.5. Respondent’s background and preferences for ginger

The functionality and usage of a product depend largely on the consumers’ culture as well as social situation (Korzen & Lassen, Citation2010). In Ghana, there are ten (10) regions by the birth of respondents that may have imparted peculiar cultures and hence ways of preparing their meals including the choice of ingredients. This study sought to assess the association between respondents’ region by birth and the uses of ginger. There was a significant difference between respondents’ use (x2 = 63.088, p = 0.030) of ginger and the purpose; whether for medicine or for spicing a meal (x2 = 63.088, p = 0.03) (p ≤ 0.05) (Appendix 1). On the other hand, there was no significant difference between respondents’ region by birth and frequency of consumption of ginger, source of preferred dried ginger, method of preparing dried ginger, and quality concerns with dried ginger on the market (Appendix 1). The difference in age of respondents showed significant differences in what they use ginger for and the frequency of consumption (p ≤ 0.05). This is probably because each age determines one’s meal choices and health decisions. There was no significant difference between age and their source of preferred dried ginger, method of preparing dried ginger, and quality concerns with dried ginger on the market.

The level of one’s education influenced the choice and use of food products. The results showed that the level of education significantly influenced the purposes for which ginger is used, frequency of usage, and the source of preferred dried ginger. On the other hand, respondents’ level of education did not have influence significantly on, the method of preparing dried ginger and quality concerns with dried ginger on the market. The outcome of this study is not much different from the findings of Owureku-Asare et al. (Citation2016) on consumer perception of dried tomatoes. According to Owureku-Asare et al. (Citation2016), even though the consumers with tertiary education embraced solar drying more than the consumers with lower education levels, it was not significant. It is not surprising that there was a significant difference between educational background and consumers’ preferred source of ginger in this study. There is a perception that items purchased from the supermarket or shop are of higher quality than in the open market. On the whole, this study revealed that respondents’ region by birth, age, and educational background did not significantly influence their quality concerns with dried ginger on the market.

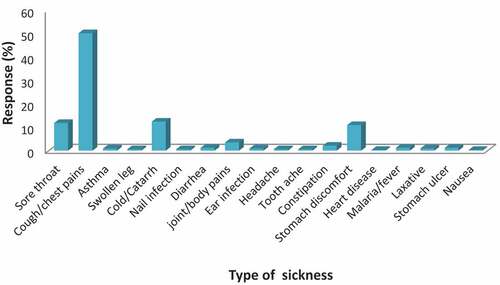

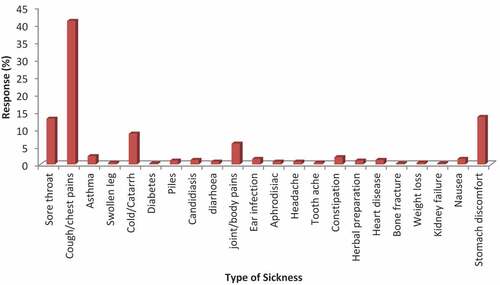

3.6. Knowledge of health benefits of ginger and its curative effect on consumers

Out of the 383 respondents, a vast majority (89.0%) knew about the medicinal efficacy of ginger (Figure ). Findings of this study show that most respondents were up-to-date with the medicinal benefits of ginger. These included upper respiratory infections, inflammatory disorders to stomach discomfort, candidiasis, aphrodisiac, and weight loss among others. In Ayurvedic medicine, ginger has been used in the treatment of diseases such as throat, pulmonary, and catarrhal problems according to Mao et al. (Citation2019) and Jayasundara and Arampath (Citation2021)

Figure 6. Consumer knowledge of the sicknesses ginger cures (n = 339). B Sicknesses that consumers used ginger to cure (n = 306).

Also worth reporting is the knowledge of ginger settling stomach discomfort such as dyspepsia, that is indigestion or bloating of the stomach, piles, and constipation as documented by Singh et al. (Citation2008) and Maroyi (Citation2013). Another 1.1% of respondents also use ginger as part of their herbal preparations. The herbal preparation could be for the amelioration of stomach discomfort which is very common in Ghana and Africa; usually done as an anal application using an enema. It could also be for an oral application for the antioxidant properties as there has been heightened importance of antioxidant benefits from natural sources (Anwar et al., Citation2018). Even though not much work has been done on the aphrodisiac properties of ginger, about 0.8% of the respondents were knowledgeable in this area. Kamtchouing et al. (Citation2002) reported that male rats fed with ginger extract of an approximate concentration of 600 mg/kg/day for 8 days had increased serum testosterone levels and testicular weight.

About 2.9% of respondents indicated their knowledge of the anti-microbial properties of ginger; 1.3% for candidiasis and 1.6% for ear infections. The antimicrobial efficacy of ginger rhizomes has been attributed to gingerol and phenolic metabolites. Studies have also shown that the use of hydroalcoholic extract as well as the oil has also been effective against certain microbes (Mao et al., Citation2019; Sa-Nguanpuag et al., Citation2011).

The anti-emetic property of ginger was among the conditions enumerated by respondents. This property of ginger has received a lot of research attention as scientists seek to solve issues with nausea associated with pregnancy and post-operation. Even though as low as 1.6% of respondents indicated knowledge of ginger’s anti-emetic properties, the reason for the low percentage may be because most respondents did not perceive it as a condition that needed much attention as cough and chest pains. That notwithstanding, Anwar et al., (Citation2018) and Singletary (Citation2010), have shown the positive effect of ginger on nausea during pregnancy and post-operative symptoms even better than anti-emetic drugs.

Respondents also revealed that ginger was used for weight loss agreeing with Mao et al. (Citation2019) on gingers’ ability to inhibit the absorption of dietary fat in the intestine and reduce serum triglycerides. On the contrary, Leal et al. (Citation2019) reported that ginger had no significant effect on blood lipids.

Many consumers are looking for natural remedies for treating various illnesses and conditions and also to augment the use of synthetic drugs because of the dangerous side effects of the continual use of synthetic drugs (Anwar et al., Citation2018; Zia-ur-rehman et al., Citation2003). The results of this study indicate that almost 80% of the respondents were using ginger to cure and prevent various illnesses and conditions.

When respondents were asked to enumerate the various conditions they used ginger to treat, 18 illnesses and conditions were highlighted. This included cold/catarrh, cough/chest pains, asthma symptoms, stomach discomfort, body/joint pains, ear infection, swollen leg, bone fracture, toothache among others as shown in Figure . The responses to the health benefits as shown in Figure were similar to those in Figure . Relatively, respondents were using ginger to cure slightly less number of illnesses, and conditions (Figure ) than were knowledgeable of (Figure ).

Upper respiratory infections are quite common worldwide, especially during cold weather; most people prefer to try several home remedies for such conditions as cold/catarrh, sore throat, cough/chest pains before resorting to orthodox medicine or augmenting the orthodox treatment with the use of ginger. Kaushal et al. (Citation2017), report of the use of ginger in Ayurvedic medicine to prevent and ameliorate catarrhal symptoms is corroborated in this study. More than half of consumers are using ginger for the treatment of upper respiratory infections (74.3%; Figure ). Discussions with respondents revealed that a cough symptom could persist for more than a month and all the orthodox medicine may have failed to mitigate it, ginger is then used to cure it.

4. Conclusion

This study conducted a survey to gather information on consumer knowledge and derived health benefits of ginger, the functionality of both fresh and dried ginger, preferences and quality of locally produced sliced dried ginger to serve as a baseline for producing locally dried ginger using solar drying. The study revealed that both fresh and dried ginger could be used for the same purposes mostly as a spice and treatment of health conditions. Consumers were very knowledgeable in the health benefits of ginger and had used ginger to treat different illnesses and conditions chiefly for upper respiratory infections such as cough and cold. Most of the consumers were willing to patronize dried ginger if quality concerns such as taste, aroma, and hygienic issues are mitigated. Ginger powder was preferred to sliced dried ginger for convenience with unanimous response to locally produced dried ginger. This all-important information will serve as baseline data for the drying of local ginger using drying technologies such as solar dryers to preserve as much as possible the taste and aroma/smell as well as prevent unhygienic issues that arise from open-sun dried ginger products.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author

Ethical Clearance

The study used human subjects; however, their consent was sort, and interviews were conducted. This study did not involve ingestion of any substance or anything that warranted ethical clearance

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.3 KB)Acknowledgements

This work was self-funded. The authors express their gratitude to all respondents in the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) for their willingness to participate in the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2022.2123766.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Roseline Esi Amoah

Dr. Roseline Esi Amoah is a Microbiologist/Food Scientist with expertise in drying of food products especially spices and cereals to ensure safe microbial levels. She has contributed greatly to product developments of health-based foods and value addition of spices through drying. Additionally, trains both industry and farmers on food safety and quality issues for grains, spices, and other food groups with keen interest in Good manufacturing practices and HACCAP.

Faustina Dufie Wireko-Manu

Faustina Dufie Wireko-Manu is an Associate Professor in Food Science and Technology at the KNUST, Ghana. She had her BSc in Food Science and Nutrition from University of Ghana in 1999, Master of Science (MSc) and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Food Science and Technology at the KNUST in 2004 and 2009 respectively.

Ibok Oduro

Ibok Oduro is a Professor of Postharvest Technology at the Department of Food Science and Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Ghana. Prof. Oduro has over 20 years of practical and theoretical experience in food processing, postharvest management, value addition, product development, and sensory analysis.

Firibu Kwesi Saalia

Firibu Kwesi Saalia is the current occupant of the OR Tambo Research Chair in Food Science and Technology. This appointment was in recognition of his pioneering work in food safety and quality and he is one of 10 Research Chairs appointed across Africa by the OR Tambo foundation and sponsored by the National Research Fund (NRF) of South Africa. He obtained BSc in Biochemistry and Food Science and MPhil in Food Science from the University of Ghana in 1990 and 2005 respectively. He later obtained PhD in Food Science and Technology from the University of Georgia, USA in May 2001, and worked in the same Department until 2005 as Post-Doctoral Research Associate. He joined the teaching faculty in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science of the University of Ghana in August 2005 as a Lecturer.

William Otoo Ellis

William Otoo Ellis is an accomplished researcher and academic of international repute, with his research interest spanning Applied Microbiology and Quality Assurance; Food Product Development and Packaging and Food Toxicology and Epidemiology. He has more than 27 years of experience working in academia and relating to organizations and civil society. Of these, more than 10 years have been at the higher echelons of higher education management, serving as Pro Vice-Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor respectively, showing leadership in nurturing the next generation. During his tenure as Vice-Chancellor of KNUST, he brought significant positive changes to the business of the University: https://webapps.knust.edu.gh/woellis/Report-on-the-Stewardship-of-WOE-KNUST-VC-2010-16.pdf.

Ebenezer Owusu

Ebenezer Owusu is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Plant and Environmental Biology, University at Ghana with over nineteen (19) years relevant working experience. He was Head of the Department for four academic years. Dr. Owusu holds BSc and PhD digress from the University of Ghana. He was an exchange student at Tufts University, Boston USA. Dr. Owusu was previously a part time lecturer at Dept. of Community Health, University of Ghana Medical School (UGMS), Univ. of Health and Allied Science, Ho and Ghana Armed Forces Staff College, Accra.

References

- Alam, P. (2013). Densitometric HPTLC analysis of 8-gingerol in Zingiber officinale extract and ginger-containing dietary supplements, teas and commercial creams. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 3(8), 634–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60128-8

- Amoah, R. E., Kalakandan, S., Wireko-Manu, F. D., Oduro, I., Saalia, F. K., & Owusu, E. (2020). The effect of vinegar and drying (solar and open-sun) on the microbiological quality of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) rhizomes. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, 8, 6112–6119. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1902

- Amoah, R. E., Sureshkumar, K., Wireko-Manu, F. D., Oduro, I., Saalia, F. K., Ellis, W. O., & Krishnamorthy, S. (2022). Effect of solar drying and vinegar pretreatment on the antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds of sliced ginger. Journal of Food Quality, 2022, 13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3675626

- Amoah, R. E., Wireko-Manu, F. D., Oduro, I., Saalia, F. K., Ellis, W. O., Dodoo, A., Dermont, C., & Manful, M. E. (2022). Effects of pretreatment and drying on the volatile compounds of sliced solar-dried ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) rhizome. Journal of Food Quality, 2022, 7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1274679

- Anwar, H., Hussain, G., & Mustafa, I. (2018). Antioxidants from natural sources. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.75961

- Bernues, A., & Corcoran, K. (2003). Labelling information demanded by European consumers and relationships with purchasing motives, quality and safety of meat. Journal of Meat Science, 65(3), 1095–1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/50309-1740(02)00327-3

- Chrea, C., Melo, L., Evans, G., Forde, C., Delahunty, C., & Cox, D. N. (2011). An investigation using three approaches to understand the influence of extrinsic product cues on consumer behavior: An example of Australian wines. Journal of Sensory Studies, 26(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-459X.2010.00316.x

- Deshmukh, A. W., Varma, M. N., Yoo, C. K., & Wasewar, K. L. (2014). Investigation of solar drying of ginger (Zingiber officinale): Empirical modelling, drying characteristics and quality studies. Chinese Journal of Engineering, 2014, 7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/305823

- Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics, (2019). Ginger, production quantities (tons) for all countries. https://www.factfish.com/statistic/ginger%2C%20production%20quantity accessed 10 June, 2019

- Jayashree, E., Visvanathan, R., & Zachariah, J. T. (2014). Quality of dry ginger (Zingiber officinale) by different drying methods. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(11), 3190–3198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-012-0823-8

- Jayasundara, N. D. B., & Arampath, P. (2021). Effect of variety, location & maturity stage at harvesting, on essential oil chemical composition, and weight yield of Zingiber officinale Roscoe grown in Sri Lanka. Helion, 7(3), E06560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06560

- Kamtchouing, P., Mbongue, F. G. Y., Dimo, T., & Jatsa, H. B. (2002). Evaluation of androgenic activity of Zingiber officinale and Pentadiplandra brazzeana in male rats. Asian Journal of Andrology, 4(4), 299–301.

- Kaushal, M., Gupta, A., Vaidya, D., & Gupta, M. (2017). Postharvest management and value addition of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): A review. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 2(1), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijeab/2.1.50

- Kitinoja, L., & Kader, A., (2015). Measuring postharvest losses in fruits and vegetables in developing countries. PEF White Paper 15. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.13921.6402

- Korzen, S., & Lassen, J. (2010). Meat in context: On the relation between perceptions and contexts. Journal of Appetite, 54(2), 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.011

- Kumar, M. (2016). Experimental forced thin layer ginger drying. Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 14(1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUME1601101k

- Kuwornu, J. K. M., Mensah-Bonsu, A., & Ibrahim, H. (2011). Analysis of foodstuff price volatility in Ghana: Implications for food security. European Journal of Business and Management, 3(4), 100–118.

- Leal, D. T., Fontes, G. G., Villa, J. K. D., Freitas, R. B., Campos, M. G., Carvalho, C., Pizziolo, V. R., & Diaz, M. A. N. (2019). Zingiber officinale formulation reduces hepatic injury and weight gain in rats feed an unhealthy diet. Health Sciences Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias, 91(4). https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201920180975

- Mao, Q., Xu, X., Cao, S., Gan, R., Corke, H., Beta, T., & Li, H. (2019). Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods, 8(6), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8060185

- Maroyi, A. (2013). Traditional use of medicinal plants in South-Central Zimbabwe: Review and perspectives. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 9(31), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-31

- Moore, D. S., & McCabe, G. P. (1993). Introduction to the practice of statistics 2nd ed. W.H Freeman and Co.

- Mueller, S., & Szolnoki, G. (2010). The relative influence of packaging, labelling, branding and sensory attributes on liking and purchase intent: Consumers differ in their responsiveness. Journal of Food Quality and Preference, 21(7), 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2010.07.011

- Owureku-Asare, M., Ambrose, R. P. K., Oduro, I., Tortoe, C., & Saalia, F. K. (2016). Consumer knowledge, preference and perceived quality of dried tomato products in Ghana. Journal of Food Science &nutrition, 2016, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.439

- Prescott, J., & Bell, G. (1995). Cross-cultural determinants of food acceptability: Recent research on sensory perceptions and preferences. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 6(6), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-2244(00)89055-X

- Sa-Nguanpuag, K., Kankyanarat, S., Sriloang, V., Tanprasert, K., & Techavuthporm, C. (2011). Ginger (Zingiber officinale) oil as an antimicrobial agent for minimally processed produce: A case study in shredded green papaya. International Journal of Agricultural and Biology, 13(6), 895–901.

- Si, W., Chen, Y. P., Zhang, J., & Chen, Z.-Y. (2018). Antioxidant activities of ginger extract and its constituents toward lipids. Food Chemistry, 239(2018), 1117–1125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.055

- Singh, K., Tiroutchelvame, D., & Patel, S. (2008). Drying characteristics of ginger flakes. Journal of Agricultural Engineering, 45(1), 57–61.

- Singletary, K. (2010). Ginger an overview of health benefits. Journal of Nutrition Today, 45(4), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0b013e3181ed3543

- Swain, M. R., Anandharaj, M., Ray, C. R., & Rani, P. R. (2014). Fermented fruits and vegetables of Asia: A potential source of probiotics. Journal of Biotechnology Research International, 2014, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/250424

- Zia-ur-rehman, Salariya, A. M., & Habib, F. (2003). Antioxidant activity of ginger extract in sunflower oil. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 83(7), 624–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.1318

Appendix 1

Table A1. Respondent background and preferences of ginger