?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Post-harvest loss is a historical challenge affecting some of agricultural products including maize which is a vital cereal crop in Tanzania. Enhanced knowledge and training on the use of metal silo and hermetic bags have been among the initiatives introduced to address post-harvest losses. This paper, therefore, assesses the effects of socio-cultural factors on the gendered decision-making process in the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. The paper looks at the role of bargaining power, task division and implications for enhancing the socio-economic status of farming households. The study was cross-sectional and used a multistage sampling method to select villages and respondents in each district. Data were collected through questionnaires, focus groups and key informant interviews. Logistic regression and descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data gathered. The findings revealed that awareness, farming experience, age and beliefs were the key socio-cultural factors that made men and women adopt better storage technologies. The findings further revealed that the division of tasks between gender-specific households was not statistically significant with respect to the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. These findings imply that there is no need for gender mainstreaming in task division and gender-sensitive technologies, even among gender-diverse farmers from diverse socio-cultural communities. Thus, awareness programs need to be expanded and adopt joint decisions through farming households so as to play a key role in balancing bargaining power.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Post-harvest loss is a historical challenge affecting many agricultural products including maize which is a vital cereal crop in Tanzania. Tailor-made training and demonstrations on the use of hermetic bags, metal silos, and insect pest management strategies to improve storage capacity were undertaken for farmers. The training was conducted under the framework of the Grain Postharvest Loss Prevention (GPLP) project. Despite these efforts, gender-based relations was reported have a role regarding decisions on the adoption of the improved maize storage technologies. Scholars also revealed that cultural norms command gender roles, distribute rights and privileges, and manage the ideal post-harvest technology. This cross-sectional study made an in-depth assessment of how socio-cultural gendered decision-making process occurs among households that participated in the training on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. The study areas were Ushetu and Mbulu Districts in Shinyanga and Manyara regions, two culturally diversified districts in Tanzania.

1. Introduction

There is a renewed interest in food security concerning post-harvest losses (Stathers et al., Citation2020) due to an increase in the global population. In the African communities, there are mixed feelings about how decisions are made regarding post-harvest management activities. With the interaction with world culture, things have changed and thus women and men participate in the decision-making regarding family undertakings. In this regard, socio-cultural factors including customs, lifestyles, and values provide dimensions for measuring and comparing the lifestyles of different societies (Sugri et al., Citation2021). These socio-cultural factors have either positive or negative impacts on gender balance on the adoption of a newly introduced storage technology (Nordhagen, Citation2021).

In sub-Sahara Africa (SSA), agricultural productivity is relatively low and food insecurity has persisted for decades (Sibanda & Workneh, Citation2020; Takahashi et al., Citation2019). Agriculture is a driver of the Tanzanian economy, contributing to 66% of the total labour force, employment, 23% of the GDP, 30% of the total export, and 65% of the raw materials needed in the industrial sector (United Republic of Tanzania (URT), Citation2016). Despite the fact that the sector is the main source of income and food for the people, about 20–30% of the food crops produced within the country are reported to be lost due to a shortage of appropriate grain storage technologies (Shee et al., Citation2019). As a result, the country has experienced some periods of food shortages, though national production can meet the national food needs (Mutungi & Affognon, Citation2013). Moreover, an increase in the investment in post-harvest loss reduction noted in developing countries such as Tanzania is meant to increase both food and income security (Omotilewa et al., Citation2018).

Maize, which is among the most important staple food crops in Tanzania, experiences post-harvest loss (PHL) of about 1–4.5% during the harvesting and 2.8–17% during the storage phase (Mutungi & Affognon, Citation2013). PHL creates seasonal and geographical shortage of maize that necessitates maize price fluctuations over time since farmers are forced to sell their products immediately after harvesting (Shee et al., Citation2019). This has put small farmers into a poverty trap. To address this problem, a variety of post-harvest handling techniques were introduced to farmers in different countries (Bokusheva et al., Citation2012; Doss, Citation2001; Gbénou-Sissinto et al., Citation2018; Kiaya, Citation2014; Omotilewa et al., Citation2018). The initiatives introduced include training and demonstration of the use of hermetic bags, metal silos, and insect pest management strategies which aimed at enhancing the storage capacity of both male and female smallholder farmers (Bokusheva et al., Citation2012; Helvetas, Citation2018; Shee et al., Citation2019). These initiatives were mainly implemented under the framework of the Grain Postharvest Loss Prevention (GPLP) project implemented by HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation in collaboration with the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC).

In addition, there is growing evidence of low levels of participation among smallholders in the adoption of collective storage practices (Owach et al., Citation2017). The adoption of improved postharvest practices and technology is assumed to be a social agency whereby men or women need to act independently to make their choices through gender relations in the households (Doss, Citation2001; Sahoo et al., Citation2018; Schaner, Citation2016). Empirical findings from recent studies show that cultural factors have a strong influence on gender roles, distribute rights and privileges, and locate the power to own, access, and manage post-harvest technologies (Helvetas, Citation2018). Such socio-cultural factors include traditions, religions, beliefs, taboos and social occupations. Even though women are more likely to be socially and economically involved in many post-harvest activities than men, it has been observed that males dominate in decision-making on the management of these socio-economic activities (Rugumamu, Citation2012).

A serious research interest in PHL management began in 2008 when investment in agriculture was revised as a means of addressing hunger, poverty and food insecurity (Kiaya, Citation2014). Accordingly, researchers such as Qu et al. (Citation2021) suggested for proper handling practices during harvesting, threshing, winnowing, transporting, and storing as a means of minimising PHL. In Tanzania, PHL is still a threat that not only affects the state of food security but also significantly compromises the livelihood of the majority of the people (Kumar & Kalita, Citation2017). Accordingly, various stakeholders, including farmers, researchers and administrators, have implemented several programs to popularize waste reduction innovations and mitigate PHL, particularly at the storage level. In this regard, the use of PHTs is vital to the adoption of appropriate technologies. Thus, an individual farmer in a household must calculate the likely costs and benefits associated with the technology (Pekmez, Citation2016).

The adoption of these improved PHTs as the social enterprise has mainly been determined by gender relations as an identity of men and women (Doss, Citation2001; Sahoo et al., Citation2018). In this respect, some roles and responsibilities related to post-harvest management (PHM) are dominated by women in some societies and by men in other societies. Despite this reality, there are limited studies on the impact of gender disaggregation on the adoption of PHTs (Bokusheva et al., Citation2012; Omotilewa et al., Citation2019). The knowledge of gender mainstreaming in task division and the adoption of gender-sensitive technologies for PHTs (Rugumamu, Citation2012; Sahoo et al., Citation2018; Shee et al., Citation2019) is still limited. As a result, how gender affects the adoption of PHTs (Gbénou-Sissinto et al., Citation2018; Takahashi et al., Citation2019) is still unclear. This paper contributes to the body of knowledge on gender roles and task division and gender-sensitive storage technologies associated with socio-cultural diversity. This study assesses how socio-cultural gendered decision-making process occurs among households that participated in the training on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies, drawing lessons from Ushetu and Mbulu Districts, Tanzania.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study sites and key variables

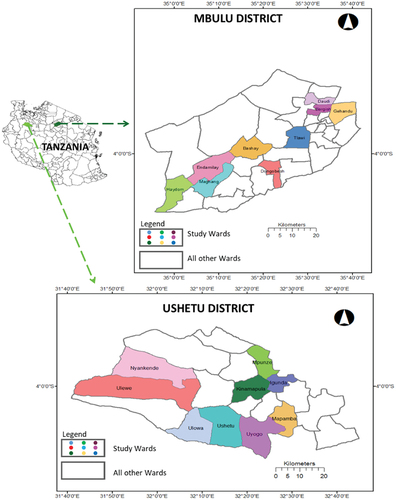

The study was conducted in the Ushetu and Mbulu Districts in Shinyanga and Manyara regions, respectively, in Tanzania (Figure ). The study sites (nine (9) wards at each District) were selected due to similarities in food systems, exposure to training and demonstration of PHTs with significant crop diversity (Mbulu District Council, Citation2018; Ushetu District Council, Citation2018).

The key independent variables considered in the study were bargaining power, socio-cultural factors, and task division (Table ).

Table 1. Measurement and descriptions of variables

Bargaining involves negotiations or agreements that are made by the members of the household to arrive at decisions regarding the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. The bargaining concept was used mainly because the individuals have heterogeneous preferences, specifically the men’s preferences, and influence on the decisions of the adoption of improved maize storage technologies (Wang Sonne, Citation2016).

Socio-cultural factors reflect customs, lifestyles and the values that characterise any society. They generally provide dimensions for measuring and comparing lifestyles of different societies. These socio-cultural factors in society can have either positive or negative gender-based influence on the adoption of a newly introduced technology (Apsalone & Šumilo, Citation2015). Task division was considered along a chain of postharvest activities comparing the roles among the gendered smallholder farmers in the adoption of maize storage technologies. The activities include harvesting, transportation, drying, threshing, cleaning, storing and marketing.

Figure indicates the influence of bargaining power, sociocultural factors and task division among the genders on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. The study assumed that a household contains two rational agents (for simplicity, the rational agents are assumed to be the male and female adults in the household) who participate in decision-making. These rational agents are characterised by variations in preferences towards the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. Therefore, in this case, gender relations at the household determine the adoption of improved maize storage technologies.

2.2. Data collection

A cross-sectional research design was used to collect the study data from the sampled populations at one point. The multi-stage sampling design was adapted. The first stage involved the purposive selection of the study areas, including neighbourhoods and villages, the study areas where those in which improved maize storage technology interventions were implemented. The second stage involved the proportionate stratified sampling which provided a realistic representation of both districts. Finally, a simple random sampling was employed by involving farming households that were introduced to PHT training and demonstrations.

These farming households were represented by either the head or his/her partner. Awareness creation on PHM was carried out to nine (9) wards in each district and targeted 37,280 farming households through either the head or a member of these households. Awareness building was linked to understanding the benefits and risks of using PHM through extension services, field visits, on-farm demonstrations and trials. In this regard, the study used z = 1.96, e = 0.02, and p = 0.02; therefore, based on the estimation, the sample size was supposed to be at least 188 respondents; hence, the actual number of the respondents involved in the study was 120 as shown in Table .

Table 2. Sample size distribution

A combination of surveys, interviews and document reviews was used to gather all relevant data. A total of two (2) focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted comprising 9 and 10 farmers aimed at representing key stakeholders from Mbulu and Ushetu Districts, respectively. The criteria used to select FGD participants include PHTs competencies, power balance among stakeholders regardless of their hierarchical positions, good knowledge of the village/district conditions, gender balance (at least one-third of women), age balance (young-adult-old), and balance of economic status (poor-moderate-rich). Moreover, key informant interviews were done with a few selected respondents (14) that included village and farmer group leaders to collect data beyond the household level, in which involved for instance, community-related taboos, costs of technologies, and how gender featured in the tasks division.

2.3. Analysis of the data

The collected data were coded, cleaned and processed in the meaningful and desired form to achieve the goal of the study. The data were analysed using SPSS. Logistic regression model was used to explore how socio-cultural factors affect a gendered decision on the adoption of improved maize PHTs.

In the model used, the adoption of maize storage technologies was regarded as a dependent variable, whereas, the age of the household head, family size, education level, gender of the household head, beliefs, traditions, farming experience, and awareness were used as independent variables as shown in Table .

Moreover, to compare the impact of task division on technology uptake between the two districts, the independent t-test was used. Then, a comparison was made on the roles of task division in the adoption of maize storage technologies in the study districts. As the independent t-test demands the assumption of normality, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the assumption of normality. In this way, the obtained value was used to compare with the earlier determination of the alpha level in order to reject or maintain the hypothesis. Furthermore, the Levene F-test for equality of variances was used to test the homogeneity of variances in the null hypothesis which assumes no variation between groups.

The decision to adopt the maize storage technologies was a binary choice. This is primarily due to the dichotomous nature of the explained variance, namely the adoption or no adoption of improved maize storage technologies. Measures of bargaining were developed using index values of between 0 and 1. A value of 1 was assigned if a measure had an influence, and 0 was assigned if otherwise. Moreover, the index value was obtained by taking the sum of the values of indicators that a particular household has observed as adding their bargaining power over the values of the entire indicators identified (Table ).

Table 3. Index measures for the indicators of bargaining power

Thus, a logit model was used to analyze the effect of bargaining power on technology adoption. This model was widely used to examine the decision-making process influencing the available alternatives. The model has also been observed by several scholars as having the ability to perform better in discrete studies; hence, it was used in the current study (Gbénou-Sissinto et al., Citation2018; Stathers et al., Citation2020). In summary, a model was given as:

Whereby, is the dependent variable indicating the probability of

farming households to adopt the modern maize storage technologies, and Y = 1 if farming households have adopted the technologies and Y = 0 if otherwise, β1 = coefficient of bargaining power, β0 = intercept, bp = bargaining power, Xi = other control variables, and βi corresponding coefficient of other control variables. As the logit model is more likely to suffer from heteroscedasticity problems and non-normality of the error term, therefore robust standard errors were computed to resolve the heteroscedasticity problem and validate usual t-tests. It is commonly referred to as:

With i = 1, 2 … .n

However, for the sake of the present study, this model has been defined as follows:

Whereby, is the dependent variable indicating the probability of

farming households to adopt the modern maize storage technologies, Y = 1 if farming households have adopted the storage technologies and Y = 0 if otherwise; β0 = intercept, Xi represents the independent variables, such as age, farming experience, gender, cultural traditions, cultural belief, cultural taboos, the wealth of the household, training to PHTs, βi represents the corresponding coefficient of independent variables and n represents the sample size. Table provides the causal pathways for the key variables and how they were measured.

The principle of reliability was respected, that is, the findings were inherently repeatable, to avoid any conflict of interest in intervening in the study. To ensure the reliability of the data gathered, the test–retest method was used. The same questions were asked two times to some of the selected respondents who had initially been interviewed. The draft questionnaire was presented to the experts for their assessment and verification of the validity of the questions. As a result of the use of this validity of the content, a limited number of questions which were found invalid were revised and others removed from the list.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

The demographic characteristics of farmers play an important part in the decision to adopt improved technologies. Some of these factors include age, gender, marital status, beliefs, family size, income level, educational qualifications and the geographic location of the farmer’s residence. The paper focused on the following demographic variables: gender, age, marital status, level of education, family size and physical location of the respondent (Table ).

Table 4. Respondent’s demographic distribution profile

The findings in Table indicate that 90% of those interviewed were between 21 and 60 years. This indicates that the majority of the farmers were capable of making decisions over the adoption of improved maize storage technologies as they belonged to the working-age group with a long farming experience. Furthermore, 48.3% and 51.7% of the respondents were males and females, respectively. On the other hand, a large proportion (87.5%) of the household was headed by males and only 12.5% were headed by females.

Based on family size, 60.9% of the households had an average of 3–6 members. In some societies, women with children thought they could exert influence on decision-making as children need basic needs that are provided by both parents. This can therefore create a means of making joint decisions on the delivery of social services. Almost 88% of the respondents were married, suggesting that there is a relatively good chance of making joint decisions among married couples on the adoption of improved PHTs.

3.2. Use and adoption of storage technologies

Most of the farmers surveyed were familiar with improved maize storage technologies. Community members were also familiar with improved PHTs through training, exhibitions, farmer groups, mass media and community meetings (Figure ). The availability of these different sources of knowledge on PHTs improved the understanding and use of the improved PHTs among farming households.

There is a satisfactory degree of uptake of improved maize storage technology in the two studied districts, but their scale is different. As mentioned earlier, maize storage technologies used by farming households include hematic bags, metal silos, and insect pest management strategies. The adoption rate at Mbulu is higher (67%) than at Ushetu (57%), as shown in Figure . Although the adoption rate is relatively high, some farming households have not adopted the improved maize storage technologies. The study also found that there are similarities between districts that prevent certain households from adopting these improved maize storage technologies. It was observed in both districts that the cost of these improved technologies is the main reason reported by 84% and 75% of the surveyed households in Ushetu and Mbulu Districts, respectively. Thus, FGDs revealed that campaigns to mobilize and appropriately use technology to raise awareness could increase the adoption rate in both districts.

Good maize storage practices go hand in hand with good management of other post-harvest activities. The results in Table present the practices employed in the study area for PHM activities. It was noted that activities such as harvesting, transportation, threshing and cleaning are predominantly dominated by traditional practices. This is primarily explained by the unavailability of modern technology for these practices in the study areas. Traditional methods are still used to dry and store maize. Due to increased awareness and availability of alternative technologies, farming households started to shift from traditional to the improved means as witnessed by most of the farmers using the combinations of the old and improved technologies. Moreover, the use of animal power as a means of transport and drying produce using tarpaulin were highly dominated by men and women at 1% level of significance, respectively. While cleaning of maize produce was mainly done by women. The findings revealed generally that the methods/technologies used to facilitate post-harvest activities between gender-specific households were not statistically significant with respect to the adoption of different PHTs, particularly during harvesting, threshing and storage (Table ).

Table 5. Adoption of different PHTs in the chain of the PHM practices

3.3. Bargaining power and adoption of PHTs

Based on measures of bargaining which were developed by given indicators using index values between 0 and 1, awareness raising, political leadership, parental wealth and formal education are key indicators that contribute to women’s bargaining power to adopt improved maize storage technology. Similarly, the appropriate proxies used such as the wife’s ownership of agricultural resources, the wife’s variations in ethnicity with her husband, and the wife being married in a nearby geographical location have little impact on increasing the women's bargaining power in the adoption of technology (Table ).

To determine the impact of bargaining power on the adoption of PHTs, the logit model was used. The results indicate that bargaining power is not statistically significant towards the adoption of improved PHTs. The findings of the logistic regression model also revealed that the coefficient of bargaining power was not statistically significant different from zero though it was positively related to the adoption of improved maize storage technologies.

However, in the same Table , the adoption was mostly influenced by awareness and gender at 1% and 10% level of significance, respectively. Consequently, to determine the impact of awareness, gender and other independent variables on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies, the average marginal impact was computed and presented in Table .

Table 6. Results of logistic regression analysis and marginal effects of bargaining power on the adoption of technology

The results in Table show that although bargaining power is positively linked to the adoption of improved maize storage technologies, its effect is not statistically significant. To be more specific, the probability of adopting the improved maize storage technologies is higher by 49% for the farming households that received the awareness program compared to their counterparts regardless of their gender.

As indicated in Figure , the level of bargaining power was low among the women. The findings from FGDs revealed further that despite the positive relationship between bargaining power and the adoption of improved maize storage technologies, awareness was the primary cause for most households to adopt improved maize PHTs.

The findings from FGD at Mbulu implied that willingness to adopt improved maize storage technologies within their households were mainly related to the knowledge and awareness they received through different sources including village meetings, mass media, and relatives. Farmers understood the rationale for using improved PHTs and therefore decided to adopt them. This is in contrast with FGD’s observation in the Ushetu District that the adoption of the improved technology is primarily a function of domestic economic control and in that the controller of the economy has the powers to allocate financial resources as he/she deems fit.

Despite the fact that couples in the households sit together and discuss how to store the maize they expect to harvest, the final decision on the kind of technology to be used is left to their husbands. This is mainly because the husbands dictate the spending patterns of the household. A similar observation was made by FGD in the Ushetu District. Participants strongly disagreed with men’s natural heritage powers of having unilateral decisions in the households of undertaking any activity or technology. In that regard, if the husband is not interested in a given technology, then the households would not adopt it.

Similar findings were reported by Extension Officers through key informant interviews regarding the spending decision of the family generated income. One of the Extension Officers of Ushetu district had this to say:

In most cases, our community couples do not usually sit together and discuss expenditures, since expenditures are primarily determined by the husbands of households. However, in most cases, the majority of outreach participants were females. This has been a barrier to the adoption of technology as women have no influence on their household decisions regarding the purchase of improved maize storage technologies.”

Alike findings were also reported by the Ward Extension Officer in Mbulu District who revealed that husbands are the key drivers of the household life, though most of them have not joined social groups existing in the community. Furthermore, the results from logistic regression and content analysis revealed that the bargaining power was not statistically significant towards influencing the households on adopting the improved maize storage technologies. As a result, the adoption has been largely influenced by the awareness farming households have received through village meetings, training and exhibitions, and mass media.

3.4. Socio-cultural factors

Table summarizes the results of the logistic model regarding socio-cultural factors and the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. The adoption of improved maize storage technologies in the male-headed households is mainly associated with traditions, awareness, beliefs, and farming experiences. Based on R2, 53% of the variation in the adoption of improved maize storage technologies has been explained by the model variables, while the remaining 47% has been explained by other variables that have not been included in the model.

Table 7. Logistic regression results

Logistic model also shows that farming experience, awareness, beliefs and the age of the household head were positively statistically significant at 1% and 5% level, respectively, on the adoption of improved maize storage by male-headed households. However, other variables such as family size, traditions, male headed and educational levels were not statistically significantly different from zero.

Similarly, when the content analysis by theme was used to analyze the information collected through FGDs, it was revealed that the adoption was mainly attributed to the awareness, belief on the performance of technology, the impact of extension officers, and the availability of maize storage technologies in the study areas (Figure ).

Figure 6. Content analysis results indicate socio-cultural factors affecting a male-headed household in adopting the improved maize storage technologies.

Decision-making was analyzed based on the understanding of who makes decisions in the household in the study areas. On average, there are similarities and differences among the couples of the farming households in making decisions related to post-harvest activities in the study areas. For instance, in Ushetu District, in most cases, decisions on harvesting, drying, threshing and storage were made jointly by the wife and the husband. While the decisions on the cleaning of maize were generally dominated by females, the decisions on treating maize were largely left to males. However, in some cases, no clear pattern was observed on who usually decides on performing a particular post-harvest activity (Table ).

Table 8. Gendered decision-making in study areas over the adoption of PHTs

Similarly, these observations are consistent with the findings in Mbulu District. In most cases, the decisions on the activities related to transportation, treating, and marketing are made by males, whereas the decisions on harvesting, drying, threshing, selecting storage technologies, packaging, storing, and marketing are made by both males and females. Furthermore, the only decision concerning drying in most cases is made by females. While the study areas are geographically isolated due to cultural differences, the results revealed that there are insignificant variations in how post-harvest activities are decided.

3.5. Task division and adoption of technology

Table presents disaggregated percentages based on gender given post-harvest activities. In Ushetu District, maize is mainly transported, processed, packaged, preserved and marketed by males, while drying and cleaning are usually carried out by females. At the same time, harvesting and threshing are carried out collaboratively by males and females. This was in contrast to what was observed in Mbulu where most of the works were performed jointly by males and females although they differ in the scale of magnitude.

Table 9. Task divisions on the basis of gender towards adoption of PHM practices

In summary, it can be concluded that 27%, 28% and 34% of postharvest tasks at Ushetu were performed by men, women and both, respectively. The remaining 11% of the tasks were carried out collaboratively by males and females. On the other hand, in Mbulu, it was revealed that about 57% of the post-harvest activities were performed jointly, whereas only 10% and 14% were performed by males and females, respectively. However, in both districts, there was no clear delineation of the factors that governed gender distribution regarding these post-harvest activities.

To compare the extent of task division between the districts, the independent t-test was used. In this case, all the post-harvest activities were combined to form a new independent variable named as a set of PHM activities (Table ). The computed variables were then analysed using an independent t-test to determine their effect on the adoption of maize storage technologies.

Table 10. Independent sample test results for PHM practices in Mbulu and Ushetu Districts

The P values in both districts exceed 0.05 (P > 0.05), indicating that post-harvest activities in both districts were not statistically significant regarding the adoption of technology. However, using the t-values, the calculated t-values were less than the values tabulated in the two districts. In addition, for both male and female smallholder farmers, no variation was observed regarding task division on the adoption of improved maize technologies in the study areas.

The results presented in Table are associated with the FGD results regarding task division on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies. In both districts, the respondents argued that there was no association between task division and the adoption of improved maize storage technology, as there was no clear pattern of task division between the genders on the PHM practices in the study areas particularly on harvesting, threshing and packaging (Table ). This is mainly due to significant variations in household members’ participation in farm activities based on gender. Moreover, in some cases, for instance, during FGDs in Ushetu District, limited participation of males on farm activities was reported in some households hence farm activities were carried out by females and children.

In other cases, the division of tasks on post-harvest activities occurs mainly due to the existing tradition that are transmitted from one generation to another. For instance, in the past the task of cleaning maize was carried out by females. This was reported during FGD in Ushetu District. In some cases, there were no uniform criteria governing people’s participation in a particular post-harvest activity. This was confirmed by the findings from key informants. Similar findings were recorded through the use of independent t-test, FGDs and key informants’ interviews, revealing that task divisions had no significant influence on farming households' decisions to adopt the improved maize storage technologies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of bargaining power

In comparison with the findings from other studies, it was noted that the findings of the current study are relatively consistent with and are supported by the findings of past studies. For example, Wang Sonne (Citation2016) found that bargaining power positively influenced household’s decisions to use clean fuels in urban as opposed to rural areas. Farmers who were members of a particular group had a greater chance of using improved storage technologies (Cunguara & Moder, Citation2011) and had improved bargaining power for cost-effective technologies (Okorley et al., Citation2014).

Findings in a study by Schaner (Citation2016) reveal that wives with higher income had higher bargaining power compared to wives with a low level of education and income in the households. Furthermore, Anand (Citation2018) highlighted that most women and men in the developing countries do not have a tradition of sitting together and discuss the adoption of technology, hence affecting the decision-making process in both rural and urban areas, in some cases this is due to peer pressure (Mmbando & Baiyegunhi, Citation2017). Awareness among members of the household was reported to have significant effects on technology adoption. In this regard and to address some of the challenges, farming households in Uganda were given subsidy to enable them experiment new technologies and learn from the experience before the adoption and investing in it (Omotilewa et al., Citation2018).

4.2. Socio-cultural factors and gender

It was noted that one of the factors that motivated farmers into adopting improved maize storage technologies is the belief about the use of such technology. This is directly supported by Rose and Fogarty (Citation2010) who observed that the adoption of technology varies significantly among different groups of people, whereby, young people who had practical training on technology adoption were more receptive to technology than was the case with older people. Moreover, cultural beliefs inherited from elders can be a barrier to the adoption among the youth.

These observations are also supported by Mmbando and Baiyegunhi (Citation2017), who reported that a greater number of older farmers keep on finding the permanent and the best solution for solving the agricultural problems compared to younger farmers who were not settled. Surprisingly, the findings of Apsalone and Šumilo (Citation2015) are in contrast with the findings in the current study. In other words, it was noted that the youth are likely to adopt improved technology practices since they have sufficient knowledge of these technologies. This is the case for rapid learners who have been exposed to improved technologies compared to the slow learners among the elderly.

As far as the contribution of awareness programs is concerned, a study by Achieng’ (Citation2014) observed that regardless of the information farmers had on improving storage technologies, there was an insignificant number of farmers who adopted improved storage technologies. This was mainly attributed by other factors such as the existence of high cost of technology and inaccessibility of the exposed technology, factors which are also reported in the current study.

4.3. Role of task division between the gendered smallholder farmers

In the two districts studied, it was noted that the division of tasks did not have any effect on the household adoption of improved maize storage technologies. This was because in both districts, there was no clear pattern of task division since there were variations in the performance of post-harvest activities among the farming households. Similar findings are reported in a study by López and Maffioli (Citation2008) who revealed that the division of tasks cannot be affected by technology uptake, but the reverse is true.

Similarly, Brukner et al. (Citation2017) observed that the introduction of new technologies into the society has disrupted the existing traditional division of tasks by replacing them with new tasks appropriate to the given technology. This is because the introduction of any technology goes in tandem with the division of tasks for the use of this technology. The new division of task models has been beneficial in that it allows men and women to participate in all tasks. Consequently, the model has made a significant contribution to closing the gender gap, although no country has reported achieving gender equality (Pachauri & Rao, Citation2013). This has been justified by unequal labour force participation based on unequal working conditions and occupational segregation.

As a consequence, Gramm et al. (Citation2020) in their women farmers empowering study found that task division alone does not have any influence on farmer decision to adopt a new technology since the adoption of technology relies on several factors such as the development of research and development skills, trend of education and training to farmers, ways of sharing information, availability of financial resources and the pressures from different development agents including government and non-governmental organizations. To influence the adoption, the environment and policy framework should be supportive (Jacobs et al., Citation2014) and more efficient extension systems should be used (Takahashi et al., Citation2019).

5. Summary and implications

This paper assessed the effects of gender-based decision-making processes on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies, drawing on two culturally diversified districts in Tanzania. The findings revealed that gender had no significant influence on the farming households' decision on the adoption of maize storage technologies. The adoption was observed based on awareness, farming experience, beliefs, and age.

Most of the farming households are aware of the improved maize storage technologies, but the final decision on whether to adopt or not to adopt is left to the husband. This was associated with the fact that in the study areas the socio-economic status of households is under the control of males in the households. In most cases, it has also been revealed that couples in the households participate in joint decision-making; however, men tended to have the final say in most of the family economic undertakings. This is mainly because women, particularly married women, cannot simply make decisions on behalf of the family. The study areas are geographically isolated with cultural differences; however, there are insignificant variations to draw in terms of how post-harvest activities are bargained and hence decided.

Based on the study findings on socio-cultural and gender-based effects on decisions on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies, the study recommends that strategies should target on building the capacity and raising awareness of maize storage technologies to all members of the community regardless of their gender. This can enable more people to acquire better understanding and therefore make decisions to adopt the improved storage technology regardless of their gender.

Both women and men need to be encouraged to engage in social groups that provide training and demonstrations on the use of storage technologies. This would help them understand the merits of storage technologies and thereby enable them to bargain and make joint decisions and therefore adopt the respective storage technologies. Thus, competences and the capability of having more influence on household decisions on the adoption of improved maize storage technologies would be facilitated if women are given leadership positions, particularly at the farmer groups and local community levels.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the University of Dodoma Research and Publication Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents before they were enrolled to participate in the study. All required protocols were observed and followed given country-level guidelines and regulations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by HELVETAS Swiss Interco-operation in collaboration with the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) within the framework of the Grain Postharvest Loss Prevention (GPLP) project. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial and technical support. We appreciate all the participants as well as the anonymous reviewers. The views expressed are those of the authors and cannot be considered to state the official position of the donors and partners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lutengano Mwinuka

Lutengano Mwinuka is an Agricultural Trade Economist who works at the Department of Economics, The University of Dodoma (UDOM) in Tanzania. He has also worked with numerous research institutions within and outside Tanzania at different capacities. He has been a Visiting Researcher at the Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University (TAMU). Currently, Mwinuka is the Visiting Researcher at Roskilde University (RUC) under Privately Managed Cash Transfers in Africa (CASH-IN) research program. Mwinuka has long experience in teaching and his areas of research interests include value-chain upgrading, the economics of new technology, industrial economics, cost-effectiveness, and political settlement. Erasto Osias Hyera is an Academician and Economist. He holds a Master of Arts in Economics from UDOM and a Bachelor of Arts with Education from the University of Dar es Salaam. Erasto and Lutengano worked together through Grain Postharvest Loss Prevention (GPLP) project.

References

- Achieng’, F. O. (2014). Socio-economic factors influencing adoption of improved maize storage systems in Bungoma District, Kenya. Master thesis, University of Nairobi.

- Anand, A. (2018). Examining the role of the intra-household bargaining in the adoption of the green technology. Scripps Senior Theses, 1259. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1259/

- Apsalone, M., & Šumilo, Ē. (2015). Socio-cultural factors and international competitiveness. Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 13(2), 276–21. https://doi.org/10.3846/bme.2015.302

- Bokusheva, R., Finger, R., Fischler, M., Berlin, R., Marin, Y., Pérez, F., & Paiz, F. (2012). Factors determining the adoption and impact of a postharvest storage technology. Food Security, 4(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-012-0184-1

- Brukner, M., Lafleur, M., & Pilterce, I. (2017). The impact of technological revolution on labour markets and income distribution. Frontier issues, no. 1, 31 July 2017, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, [New York]. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/2017/development-policy-seminar-frontier-issuesthe-impact-of-the-technological-revolution-on-labour-markets-and-income-distribution/

- Cunguara, B., & Moder, K. (2011). Is agricultural extension helping the poor? Evidence from rural Mozambique. Journal of African Economies, 20(4), 562–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejr015

- Doss, C. R. (2001). Designing agricultural technology for African women farmers: Lessons from 25 years of experience. World Development, 29(12), 2075–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00088-2

- Gbénou-Sissinto, E., Adegbola, Y. P., Biaou, G., & Zossou, R. C. (2018). Farmers’ willingness to pay for new storage technologies for maize in Northern and Central Benin. Sustainability, 10(8), 2925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082925

- Gramm, V., Torre, C. D., & Membretti, A. (2020). Farms in progress-providing childcare services as a means of empowering women farmers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability, 12(2), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020467

- Helvetas. (2018). Tanzania: Increase food security and income for farming households in Central Corridor of Tanzania. https://www.helvetas.org/en/tanzania/what-we-do/how-we-work/our-projects/tanzania-storage-food-products

- Jacobs, M. T., Broese van Groenou, M. I., de Boer, A. H., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2014). Individual determinants of task division in older adults’ mixed care networks. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12061

- Kiaya, V. (2014). Post-harvest losses and strategies to reduce them. ACF International, pp 1-25. http://www.academia.edu/download/45278162/POST_HARVEST_LOSSES.pdf

- Kumar, D., & Kalita, P. (2017). Reducing postharvest losses during storage of grain crops to strengthen food security in developing countries. Foods, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6010008

- López, F., & Maffioli, A. (2008). Technology adoption, productivity and specialization of Uruguayan breeders: Evidence from impact evaluation. Working Papers OVE/WP-07/08, Office of Evaluation and Oversight (OVE), Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, D.C.

- Mbulu District Council. (2018). Mbulu District Council. www.mbuludc.go.tz/history

- Mmbando, F. E., & Baiyegunhi, L. J. S. (2017). Socio-economic and institutional factors influencing adoption of improved maize varieties in Hai District, Tanzania. Journal of Human Ecology, 53(1), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2016.11906955

- Mutungi, C., & Affognon, H. (2013). Fighting food losses in Tanzania: The way forward for postharvest research and innovations. ICIPE Policy Brief, 3/13. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/52222

- Nordhagen, S. (2021). Gender equity and reduction of post-harvest losses in agricultural value chains. Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), working paper no. 20, Geneva, Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.36072/wp.20.

- Okorley, E. L., Acheampong, L., & Abenor, M. T. E. (2014). The current status of Mango farming business in Ghana: A case study of Mango farming in the Dangme West District. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science, 47(1), 73–80. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/gjas/article/view/107031

- Omotilewa, O. J., Ricker-Gilbert, J., & Ainembabazi, J. H. (2019). Subsidies for agricultural technology adoption: Evidence from a randomized experiment with improved grain storage bags in Uganda. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 101(3), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay108

- Omotilewa, O. J., Ricker-Gilbert, J., Ainembabazi, J. H., & Shively, G. E. (2018). Does improved storage technology promote modern input use and food security? Evidence from a randomized trial in Uganda. Journal of Development Economics, 135, 176–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.07.006

- Owach, C., Bahiigwa, G., & Alepu, G. (2017). Factors influencing the use of food storage structures by agrarian communities in Northern Uganda. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 7, 127–144. http://dx.doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2017.072.003

- Pachauri, S., & Rao, N. D. (2013). Gender impacts and determinants of energy poverty: Are we asking the right questions? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5(2), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.04.006

- Pekmez, H. (2016). Cereal storage techniques: A review. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, B6, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.17265/2161-6264/2016.02.001

- Qu, X., Kojima, D., Wu, L., & Ando, M. (2021). The losses in the rice harvest process: A review. Sustainability, 13(17), 9627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179627

- Rose, J., & Fogarty, G. (2010). Technology readiness and segmentation profile of mature consumers. Conference Proceedings of Academy of World Business, Marketing & Management Development, 4, 57–65.

- Rugumamu, C. (2012). Assessment of post-harvest technologies and gender relations in maize loss reduction in Pangawe village Eastern Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Science, 35, 67–76. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjs/article/view/73533

- Sahoo, L., Arya, M. P. S., Patra, C., Prusty, M., Sahoo, A., & Sahoo, M. (2018). Gender roles in seed storage and management. International Journal of Science, Environment and Technology, 7(1), 219–224. https://www.ijset.net/journal/2035.pdf

- Schaner, S. (2016). The cost of convenience?: Transaction costs, bargaining power, and savings account use in Kenya. Journal of Human Resources, 52(4), 919–945. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.52.4.0815-7350R1

- Shee, A., Mayanja, S., Simba, E., Stathers, T., Bechoff, A., & Bennett, B. (2019). Determinants of postharvest losses along smallholder producers maize and sweet potato value chains: An ordered Probit analysis. Food Security, 11(5), 1101–1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00949-4

- Sibanda, S., & Workneh, T. S. (2020). Potential causes of postharvest losses, low-cost cooling technology for fresh produce farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 16(5), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2020.14714

- Stathers, T., Holcroft, D., Kitinoja, L., Mvumi, B. M., English, A., Omotilewa, O., Kocher, M., Ault, J., & Torero, M. (2020). A scoping review of interventions for crop postharvest loss reduction in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Nature Sustainability, 3(10), 821–835. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00622-1

- Sugri, I., Abubakari, M., Owusu, R. K., & Bidzakin, J. K. (2021). Postharvest losses and mitigating technologies: Evidence from Upper East Region of Ghana. Sustainable Futures, 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2021.100048

- Takahashi, K., Muraoka, R., & Otsuka, K. (2019). Technology adoption, impact, and extension in developing countries’ agriculture: A review of the recent literature. Agricultural Economics, 51(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12539

- United Republic of Tanzania (URT). (2016). Agricultural sector development strategy: 2015/2016 – 2024/2025. Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives.

- Ushetu District Council. (2018). Ushetu District Council. www.ushetudc.go.tz/history

- Wang Sonne, S. E. (2016). Stop the killer in the kitchen: Do women intrahousehold bargaining power trigger clean fuel adoption? Evidence from Senegal. A paper presented at GGKP 4th Annual Conference, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, Union for African Population Studies (UAPS). September 6-7, 2016. https://uaps2015.popconf.org/papers/150769