?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Poor identification of Contagious caprine pleuropneumonia diseases from its signs and symptoms is a major problem to goat farmers which leads to use of wrong method of disease control. The uptake of control strategies like vaccination by farmers depends on many factors while awareness and knowledge become the foundation of the technology adoption processes. This therefore necessitated a study to understand the level of awareness and knowledge of Contagious caprine pleuropneumonia, which is a highly infectious goat disease. The study analysed and used cross-sectional data collected from 342 households interviewed in October, November, and December 2020 in Kajiado County and Taita Taveta County in Kenya. These two counties are dominated by agro pastoralists and goat keeping is predominant. The study examines the factors influencing the agro pastoralists’ knowledge and level of awareness on the six major signs and symptoms of Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia disease differentiating it from other goat diseases. Multivariate probit model was the main data analysis method used. Results show that agro pastoralists’ level of knowledge and awareness on Contagious Caprine Pleuropnemonia disease depend significantly on other factors such as the gender of household head, age, education level, household size, access to extension services, and group dynamics. The findings imply that policymakers and agricultural development partners should increase public and private investment on agro pastoralists’ training and education programmes which is one of the main pathways for increasing public awareness in livestock dominated areas.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Contagious Caprine Pleuropnemonia (CCPP) is a highly infectious disease with equally high mortality rate which has negative economic impact on goat farming in arid and semi-arid regions. The livelihood of the household in these regions greatly depends on livestock keeping especially goats which often are resilient to drought, occasioned by climate change. Farmers’ knowledge and awareness of the disease symptoms will ensure early detection and proper preventive measures which include vaccination, medication, and isolation of sick animals from the herd, which helps to contain and stop the spread of the disease hence healthy goats leading to improved food security, reduced poverty status and increased income of these farm households and cross-boundary communities as they share common routes, grazing fields, and watering points.

1. Introduction

Uptake of a technology by farmers depends on many factors while awareness and knowledge become the foundation on which other technology adoption processes are built on (Heffernan et al., Citation2008). Public health awareness helps to reduce the risk of disease infections in livestock production value chain (Alemayehu et al., Citation2021). Wrong diagnosis leads to loss and spread of disease among the stock (Ozturk et al., Citation2019). A farmer may treat a different disease from the one which infects his/her livestock due to lack of knowledge and awareness. Once a farmer can identify signs and symptoms of the disease then it would be easier to use the right and effective control method (Nyangau et al., Citation2020). Vaccines offer one of the most effective means of management of diseases. The vaccines are known to boost immunity such that in the event the livestock is attacked in future; it remains resilient and strong thereby maintaining its productivity. They have been demonstrated to have environmental, health and economic benefits (Ozawa et al., Citation2012: Stack et al., Citation2011).

Livestock sector especially keeping of goats in semi-arid areas helps to improve livelihoods of rural farmers in many developing nations (Dey et al., Citation2020: Dutta et al., Citation2021). These areas are characterised by unreliable rainfall pattern which suits goat keeping as they can be grazed in a different location in case of harsh weather and environmental conditions. However, goat farming is increasingly facing a serious challenge of attack by Contagious Caprine Pleuropnemonia (CCPP) disease which is highly contagious and fatal with a mortality rate of 70% and morbidity that range from 80% to 100%, an economic loss to farmers and the goat industry (Kipronoh et al., Citation2016; Abd-elrahman & Khafaga, Citation2019). The disease can be prevented and controlled by vaccination. Regular interaction between goats due to common grazing fields and watering points are among factors leading to faster spread of CCPP disease among goat herds. Educating farmers on CCPP can help in the designing and implementation of the effective CCPP control methods among the agro pastoralist communities.

Livestock experts have been reported to play little role in controlling some diseases like CCPP and Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (CBPP) which generally have low prevalence within the country but widespread among pastoralist and specifically agro-pastoralist regions where the survey was conducted (Kipronoh et al., Citation2016). Declining number of extension and livestock experts in Sub-Saharan Africa especially in Kenya coupled with migratory nature of pastoralists results in majority of livestock keepers treating their own animals (Gido et al., Citation2015; Kingiri, Citation2021; Lamuka et al., Citation2017; Onono et al., Citation2013). There is need to diversify a mechanism to educate agro pastoralists so that they can know and easily identify these diseases, prevent their transmission and even report their outbreak to the relevant government offices. This study therefore was undertaken to understand the level of awareness and knowledge of CCPP among agro pastoralists in Kajiado and Taita Taveta Counties in Kenya.

The Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Institute (KALRO) in partnership with Kenyatta University (KU) and Kenya Veterinary Vaccines Production Institute (KEVEVAPI) is promoting uptake of CCPP vaccine by smallholder farmers. The widespread adoption of this technology depends on farmers’ knowledge, attitude and awareness of the disease and means of controlling it. Creating awareness will therefore support the development of policy on improving CCPP disease educational programme in the region which will in turn helps in prevention and reduction of disease incidences in the region.

2. Conceptual framework and econometric estimation strategy

2.1. Conceptual framework

Conceptual framework simplifies the understanding of relationship between dependent and explanatory variables. Change in the independent variable has an influence on the dependent variable. The framework in Figure shows how various variables related and interacted to influence agro pastoralists’ knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease. Agro pastoralists’ CCPP disease knowledge and awareness were influenced by various factors among them were household socio-economic and institutional characteristics which includes age of the household head, education level as it is believed that those with higher level of education understand disease symptoms faster than those with low level of education. The number of household members as well as the main occupation of the household head dictate awareness level. Farm characteristics include farming experience, accessed land size, tropical livestock unit (TLU) also influence awareness. Lastly institutional factors including, credit access, access to extension services and group membership increase the chances of learning as a person interacts with many individuals where farmers discuss matters concerning their livestock welfare and advise one another. There are also some intervening variables which are beyond the control of agro pastoralist’s such as climate variability, government policies among other factors which can affect their knowledge and awareness on CCPP disease. Once farmers are aware and knowledgeable about the disease, they can apply preventive measures for instance, vaccinating their goats against CCPP a service done by experts and putting-up other control measures when goats are attacked by the disease. This positive response by agro pastoralists leads to improved livestock health which translates into increased household income, food security and their wellbeing.

2.2. Model specification

The study employed a multivariate probit (MVP) model to capture agro pastoralists’ knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease in terms of its different signs and symptoms. Rather than relying on a single response of “yes” or “no” for agro-pastoralists aware or not on CCPP symptoms. Multivariate probit model brings out the interconnections between these CCPP disease symptoms and signs in their specific correlations as univariate probit or logit models do not factor in correlation of error terms leading to biased estimates (Kassie et al., Citation2013: Kurgat et al., Citation2018).

Several variables were considered which were likely to influence agro pastoralists’ knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease major signs and symptoms in study regions. Six major signs of CCPP disease (weakness and loss of appetite, coughing, nasal discharge accompanied by fever (high temperature), exercise intolerance progresses to respiratory distress, open mouth breathing, foamy salivation) were tested on farmers who during the interview responded that they were aware of CCPP disease by naming all its signs and symptoms in infected goats.

Description of the Multivariate Probit Model

Let denote a random variable a signed values of (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) for positive integers, representing all the six signs and symptoms of CCPP disease. X denotes a set of conditioning variables that includes household socioeconomic, farm and institutional characteristics and other unobserved factors as shown by the stochastic error term,

. Where

is the corresponding vector of parameters to be estimated and

is the latent variable and, are the error terms distributed as multivariate normal, with each having zero mean and variance-covariance matrix V, where V = 1 on the leading diagonals and correlations as off-diagonal elements (Cappellari & Jenkins, Citation2003).

3. Methodology

3.1. Study sites

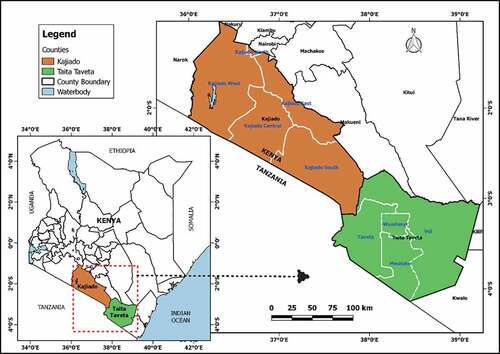

The survey was conducted in two counties in Kenya namely Taita Taveta and Kajiado (Figure ). These are the areas with CCPP disease prevalence and CCPP vaccine had been disseminated before for more than a decade, yet farmers’ adoption rate of the vaccine was low. These two counties are dominated by agro pastoralists which involves growing of crops and livestock rearing. These households are settled and can be traced in case of monitoring exercise or any case of intervention. This study was conducted in October, November, and December 2020.

3.2. Data collection procedures

Data was collected using a structured questionnaire that was developed to capture all the variables needed to answer the objectives of the study. Specifically, the questionnaire covered information on general household socio-economic, farm and institutional characteristics, farmers’ awareness, and knowledge of CCPP disease which was affecting goats. A pre-test was conducted in the selected areas and the questionnaire was corrected and adjusted appropriately. The data obtained was from interviewing either the household head or the spouse. Both spot checks and back checks were appropriately conducted during the survey and data cleaning and analysis were conducted using Excel, SPSS and STATA softwares.

3.3. Sample size and sampling procedures

The sample size was determined based on the Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling method. Both counties had relatively equal number of adopters (those farmers who had vaccinated their goats against CCPP disease within the last one year) from the ministry of livestock reports. Information was collected from a total of 367 household respondents. After data cleaning exercise a total number of 342 respondents were used in the analysis to represent the two counties as data from 25 households were dropped before the analysis because they had inadequate data which was as a result of incomplete response.

The study used Cochran (Citation1963) formula in determining the minimum required sample size as:

Where:

is the preferred sample size

the estimated proportion of agro pastoralists who have used CCPP vaccine.

the estimated proportion of agro-pastoralists who have not used CCPP vaccine (1-

).

the Z-value which is found in the Z table (95% confidence level gives Z value of 1.96).

e is the margin of error.

323

This provided a sample population of 323 respondents.

A multistage sampling procedure was adopted. In stage one, two counties were purposively selected which were Kajiado and Taita Taveta counties. The study counties were purposefully selected with the knowledge of where the CCPP vaccine technology had been disseminated. Next, two sub-counties were randomly selected from each county using Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling method. In each sub-county two wards were sampled but wards in urban and peri-urban areas were dropped from the list. Source lists of old CCPP vaccine adopters also guided village selection criteria though there were challenges of tracking these adopters as GPS data was not available, and systematic random sampling was used. Neighbouring non-adopters of the CCPP vaccine users were also randomly sampled and interviewed.

4. Results and discussions

This section presents results of the descriptive analysis of the data obtained and discussions of results from MVP model presented and further compare findings with other studies.

4.1. Descriptive statistics of variables used in analysis

Table reveals that 90% (n = 342) of the total agro pastoralists interviewed were aware of the disease, while 10% (n = 342) were not aware of the CCPP disease.

Table 1. Agro pastoralists CCPP disease Awareness

Table shows the description of both dependent and explanatory variables as used in the analysis. Dependent variables describe how agro pastoralists differentiate CCPP disease from other diseases in terms of livestock symptoms and signs. The six major symptoms were:

weakness and loss of appetite

coughing

nasal discharge accompanied by fever (high temperature)

goat exercise intolerance progresses to respiratory distress

open mouth breathing, and

foamy salivation

Table 2. Description of both dependent and explanatory variables as used in the multivariate probit model analysis

It is evident that majority of farmers were aware of coughing (84%, n = 309) as a sign of the disease but because most respiratory diseases are displayed through coughing, more signs were necessary for farmers to confirm evidence of CCPP disease. Weakness was known by 50%, n = 309, nasal discharge (42%, n = 309), respiratory distress (43%, n = 309), open mouth breathing (49%, n = 309). However, foamy salivation was mentioned by few farmers (17%, n = 309), this is a clear indication that some CCPP disease signs and symptoms were more pronounced by agro pastoralists than others. The average age of the household heads were 47.4 years. Most of the interviewed agro pastoralists were male and were largely engaging in farming with few in off-farm activities as their main occupation. More than half of agro pastoralists who were aware of the disease adopted CCPP vaccine (51%, n = 309). The average goat keeping experience by dependent farmers was 16.05 years with a minimum value of 1 and maximum of 60 years, respectively. More than half of agro pastoralists (67%, n = 309) have experienced CCPP disease in their own herds. Household membership to a group had a mean of 0.36 and finally, only 23% of agro pastoralists who were aware of the disease received agricultural extension service on goat production.

4.2. Dependent variables correlations

The likelihood ratio test (chi2(15) = 80.3164 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000) of the mutual independence of the disturbance terms for the agro pastoralists knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease was strongly rejected, the indication was the multiple farmers’ awareness in the study area was not mutually independent supporting multivariate probit model. Furthermore, pairwise correlations between error terms for the six awareness CCPP disease signs are presented in Table . Out of 15 coefficients, 7 were significantly correlated though not as substitute but as complements. Most farmers’ knowledge on CCPP disease were positively correlated for instance, nasal discharge and weakness as well as open mouth breathing, and respiratory distress were positively correlated, and this confirmed the study choice of using multivariate probit model.

Table 3. Correlation coefficients of knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease from MPV model (Standard errors in parentheses)

4.3. Factors contributing to agro pastoralists’ knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease

Table indicates that the socioeconomic, farm and institutional factors are important in shaping up the households’ knowledge and awareness in differentiating CCPP disease from other diseases in terms of symptoms and signs in infected goats. Agro pastoralists whose herds had not been attacked by CCPP were more likely to identify weakness and loss of appetite, nasal discharge accompanied by fever (high temperature), exercise intolerance progresses to respiratory distress, and lastly, open-mouth breathing by goats as main signs of CCPP disease. Result revealed that farmers who have previously experienced CCPP disease attacking their goats were aware of more signs and symptoms of the disease than their counterparts whose herds were not attacked. Experience creates more knowledge and awareness as they have the firsthand information on the disease hence easier identification.

Table 4. Parameters of Multivariate Probit Model for estimating farmers’ awareness of CCPP disease signs and symptoms

Gender of the farmer was found to have an influence on farmers’ knowledge and awareness of CCPP disease, male farmers were more aware of the advance signs and symptoms of CCPP disease than women. The gender coefficient was negative and significant for goat exercising intolerance progresses to respiratory distress, open mouth breathing, and foamy salivation. This finding might be attributed to the fact that most goat handling was done by male farmers and because of this close relationship they may have more observation time on livestock to notice more advance symptoms of the disease. According to Mutua et al. (Citation2019), in pastoralist areas men move with large number of livestock to search for pasture as women are left with a considerable number in the homestead and the disease control and management were regarded as men’s responsibility. The role of looking after grazing livestock in the studied communities is an activity majorly conducted by male household members who are able to migrate from one region to another. Mugi-Ngenga et al. (Citation2016) and Ouya et al. (Citation2020) also had a similar finding that control and access to important agriculture resources are dominated by men due to socio-cultural and customs.

Results revealed positive relationship between the education level of the household head and two CCPP disease symptoms which are nasal discharge accompanied by fever as well as goat exercising intolerance progressing to respiratory distress. This implies that farmers with higher level of education were more likely to identify advance symptoms and signs of CCPP disease as they can access resources and information regarding various diseases. Education level of the household head has been reported by many scholars to have a positive relationship on adoption of agricultural technology as well as facilitating farmers’ knowledge and awareness on various livestock diseases. According to Azra Batool et al. (Citation2018), an educated individual gains self-esteem, self- awareness, and self-confidence which is helpful in decision making process. This result is in line with Singh et al. (Citation2019), finding that livestock farmers’ education level significantly associated with their knowledge on zoonotic diseases. This result further concurs with Aryal et al. (Citation2018) who found that educated household heads have better ability and knowledge to access and absorb new ideas and information, which in turn influence their decision to adopt new agricultural technology.

The size of the household has a positive effect on awareness of coughing on goats. The possible explanation is that many household members increase the chance of detecting the disease because least a member would spot the infected goat which might then be separated from the herd, thus reducing chances of healthier livestock contacting the disease. Bigger household size also means more members for labour as livestock keeping especially in these regions is more labour intensive and as more people interact with goats, any disease signs and symptoms are likely to be noticed. Many family members can also take turns in looking after livestock as well as distributing roles to different members making the activity efficient and productive. This finding is also similar to that of Suvedi et al. (Citation2017), who reiterated that larger households have the ability to participate in other activities for instance, attending trainings and taking part in agricultural extension services as they can easily divide roles into various activities than smaller size households.

Membership to a group is essential for farmers as they learn through discussions, share information, advice each other therefore helping in raising their awareness and knowledge (Uaiene & Arndt, Citation2009). Mignouna et al. (Citation2011) found out that farming households belonging to groups have more understanding and adopt agricultural technologies as a social capital thereby strengthening their trust in group membership. The result indicated that agro pastoralists belonging to a group had more knowledge to identify weakness and open breathing as the main signs and symptoms of CCPP disease on goats. With the finding by Kassie et al. (Citation2014), that any member of the household belonging to a group helps in promoting social capital which is a platform for knowledge and experience sharing is a support to this finding.

Furthermore, awareness and knowledge on CCPP varied across different agro-ecological zones. Site dummies Kajiado and Taita Taveta counties model were found to be statistically significant. Taking Taita Taveta county as a base category and the coefficient were negative this implied that agro pastoralists in Taita Taveta County had relatively lower probability of awareness and knowledge on nasal discharge and goat exercising intolerance progresses to respiratory distress than their Kajiado County counterparts. These two counties are homes to different ethnic communities as well as different county governments with varied facilities and expertise. Kurgat et al. (Citation2018) also found that some locations have more developed infrastructures than others which facilitate easier access to farm inputs, information, and technology hence reducing transaction costs.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The results indicated that a good number of agro pastoralists (90%, n = 342) in both counties were aware of CCPP disease signs and symptoms. However, some signs and symptoms of CCPP disease were not well known to farmers a clear indication of minimal extension guidelines in the study regions. Since farmers in these regions are agro pastoralists and majority self-treat their livestock due to scarcity of veterinary officers as well as paravets, and mobilising them becomes a challenge, appropriate sensitization approach should be developed encouraging them to seek proper extension services from government and private extension agents for quality service delivery. These service providers should also be equipped with diagonostic manuals which are simplified to farmers. Educating agro pastoralists on CCPP disease signs and symptoms and benefits of vaccinating goats against the disease should be enhanced by conducting regular trainings, demonstrations, exhibitions and seminars which maybe audio-visual. This collaborative requires farmers to be sensitized by providing timely, reliable and accurate information about CCPP disease and vaccine as the main control method. It can be achieved through increased public and private investment on agro pastoralists’ training and education programmes which is one of the main pathways for increasing public awareness in livestock dominated areas in Kenya. By enforcing awareness campaign measures at farm and village level, the Kenyan livestock sector will be protected against CCPP disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors highly acknowledge Kenya Climate Smart Agriculture Project (KCSAP) for funding the work. Authors also appreciate the technical support offered by Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) Director General, as well as Kenyatta University for providing a conducive environment during the period of writing the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Goat keepers in Kajiado and Taita Taveta Counties for providing information and equally grateful to Kajiado and Taita Taveta County Director of Veterinary Services for sharing the required information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fredrick Ochieng Ouya

Fredrick Ochieng Ouya is a researcher with esteemed competencies in coordinating surveys through designing, planning, executing and supervising data collection, data analysis, presentations, reporting and documentation using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. He was the research assistant in the project which covered Kajiado and Taita Taveta counties in Kenya. The project was implemented by Kenyatta University, KALRO, and KEVEVAPI. The second and the third authors are lecturers from Kenyatta University. The fourth author is a research scientist in KALRO. The fifth author is a senior scientist in KALRO and the project coordinator.

References

- Abd-elrahman, A. H., & Khafaga, A. F. (2019). The first identification of contagious caprine pleuropneumonia (CCPP) in sheep and goats in Egypt : Molecular and pathological characterization. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 52(2), 1179–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-02116-5

- Alemayehu, G., Mamo, G., Desta, H., Alemu, B., & Wieland, B. (2021). Knowledge, attitude, and practices to zoonotic disease risks from livestock birth products among smallholder communities in Ethiopia. One Health, 12(1), 100223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100223

- Aryal, J. P., Jat, M. L., Sapkota, T. B., Khatri-Chhetri, A., Kassie, M., Maharjan, S., & Maharjan, S. (2018). Adoption of multiple climate-smart agricultural practices in the Gangetic plains of Bihar, India. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 10(3), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-02-2017-0025

- Azra Batool, S., Ahmed, H. K., & Qureshi, S. N. (2018). Impact of demographic variables on women’s economic empowerment: An ordered probit model. Journal of Women & Aging, 30(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2016.1256734

- Cappellari, L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2003). Multivariate probit regression using simulated maximum likelihood. The STATA Journal, 3(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0300300305

- Cochran, W. G. (1963). Sampling Techniques (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Dey, A. R., Begum, N., Alim, M. A., Malakar, S., Islam, M. T., & Alam, M. Z. (2020). Gastro-intestinal nematodes in goats in Bangladesh: A large-scale epidemiological study on the prevalence and risk factors. Parasite Epidemiology and Control, 9(1), e00146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00146

- Dutta, P. K., Biswas, H., Ahmed, J. U., Shakif, U. L., Azam, M., Ahammed, B. M. J., & Dey, A. R. (2021). Knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) towards Anthrax among livestock farmers in selected rural areas of Bangladesh. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 7(5), 1648–1655. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.561

- Gido, E. O., Sibiko, K. W., Ayuya, O. I., & Mwangi, J. K. (2015). Demand for agricultural extension services among small-scale maize farmers: Micro-level evidence from Kenya. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 21(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2013.872045

- Heffernan, C., Thomson, K., & Nielsen, L. (2008). Livestock vaccine adoption among poor farmers in Bolivia: Remembering innovation diffusion theory. Vaccine, 26(19), 2433–2442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.045

- Kassie, M., Jaleta, M., Shiferaw, B., Mmbando, F., & Mekuria, M. (2013). Adoption of interrelated sustainable agricultural practices in smallholder systems: Evidence from rural Tanzania. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(3), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.08.007

- Kassie, M., Ndiritu, S. W., & Stage, J. (2014). What determines gender inequality in household food security in Kenya? Application of exogenous switching treatment regression. World Development, 56(1), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.025

- Kingiri, A. N. (2021). Agricultural advisory and extension service approaches and inclusion in reaching out to Kenyan rural farmers. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 13(7), 797–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1823098

- Kipronoh, A. K., Ombui, J. N., Kiara, H. K., Binepal, Y. S., Gitonga, E., & Wesonga, H. O. (2016). Prevalence of contagious caprine pleuro-pneumonia in pastoral flocks of goats in the Rift Valley region of Kenya. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 48(1), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-015-0934-0

- Kurgat, B. K., Ngenoh, E., Bett, H. K., Stöber, S., Mwonga, S., Lotze-Campen, H., & Rosenstock, T. S. (2018). Drivers of sustainable intensification in Kenyan rural and peri-urban vegetable production. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 16(4–5), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2018.1499842

- Lamuka, P. O., Njeruh, F. M., Gitao, G. C., & Abey, K. A. (2017). Camel health management and pastoralists’ knowledge and information on zoonoses and food safety risks in Isiolo County, Kenya. Pastoralism, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-017-0095-z

- Mignouna, D. B., Manyong, V. M., Mutabazi, K. D. S., & Senkondo, E. M. (2011). Determinants of adopting imazapyr-resistant maize for Striga control in Western Kenya: A double-hurdle approach. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 3(1), 572–580. http://www.academicjournals.org/JDAE

- Mugi-Ngenga, E. W., Mucheru-Muna, M. W., Mugwe, J. N., Ngetich, F. K., Mairura, F. S., & Mugendi, D. N. (2016). Household’s socio-economic factors influencing the level of adaptation to climate variability in the dry zones of Eastern Kenya. Journal of Rural Studies, 43(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.11.004

- Mutua, E., de Haan, N., Tumusiime, D., Jost, C., & Bett, B. (2019). A qualitative study on gendered barriers to livestock vaccine uptake in Kenya and Uganda and their implications on Rift Valley Fever control. Vaccines, 7(3), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines7030086

- Nyangau, P., Muriithi, B., Diiro, G., Akutse, K. S., & Subramanian, S. (2020). Farmers’ knowledge and management practices of cereal, legume and vegetable insect pests, and willingness to pay for biopesticides. International Journal of Pest Management, 68(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2020.1817621

- Onono, J. O., Wieland, B., & Rushton, J. (2013). Factors influencing choice of veterinary service provider by pastoralist in Kenya. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 45(6), 1439–1445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-013-0382-7

- Ouya, F., Ayuya, O. I., & Kariuki, I. M. (2020). Effects of agricultural intensification practices on smallholder farmers’ livelihood outcomes in Kenyan hotspots of Climate Change. East African Journal of Science, Technology and Innovation, 2(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.37425/eajsti.v2i1.110

- Ozawa, S., Mirelman, A., Stack, M. L., Walker, D. G., & Levine, O. S. (2012). Cost-effectiveness and economic benefits of vaccines in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Vaccine, 31(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.103

- Ozturk, Y., Celik, S., Sahin, E., Acik, M. N., & Cetinkaya, B. (2019). Assessment of farmers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices on antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance. Animals, 9(9), 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9090653

- Singh, B. B., Kaur, R., Gill, G. S., Gill, J. P. S., Soni, R. K., & Aulakh, R. S. (2019). Knowledge, attitude, and practices relating to zoonotic diseases among livestock farmers in Punjab, India. Acta tropica, 189(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.09.021

- Stack, M. L., Ozawa, S., Bishai, D. M., Mirelman, A., Tam, Y., Niessen, L., & Levine, O. S. (2011). Estimated economic benefits during the ‘decade of vaccines’ includes treatment savings, gains in labor productivity. Health Affairs, 30(6), 1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0382

- Suvedi, M., Ghimire, R., & Kaplowitz, M. (2017). Farmers’ participation in extension programs and technology adoption in rural Nepal: A logistic regression analysis. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 23(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1323653

- Uaiene, R. N., & Arndt, C. (2009). Farm household efficiency in Mozambique ( No. 1005-2016-79054). International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE).