?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study was conducted to describe village-based local chicken performance, major husbandry practices, and product consumption habits of households in an agro ecological base. Multi-stage sampling techniques were applied for this study. Semi-structured questionnaire, field observation, and key informant interview methods of data collection were used. The majority of households (71.00%) were providing supplementary feed for their chickens. Feed supplementation practices in the lowland areas were significantly lower (p < 0.05) and accounted for 46.24% of respondents. In the study area, 57.33% of respondents were faced disease problems which were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in lowland areas. Most of respondents (81.67%) used ethno veterinary to treat their ill chickens. Annual egg production/hen, number of eggs/hen/clutch, number of clutches/hen/year, age of cockerels at first mating, pullets at first egg laying, number of egg set/brooding were 61.91 ± 5.70, 14.34 ± 1.69, 3.44 ± 0.44, 5.76 ± 0.68 months, 6.26 ± 0.26 months, and 11.95 ± 1.55, respectively. The survey also indicated that survived chick to market age (66.45 ± 6.83%), male age at slaughter (9.16 ± 1.02 months), number of eggs hatched per incubation (9.60 ± 1.36), and hatchability percentage were 79.90 ± 4.48%. The number of eggs consumed/per capita/year, and average numbers of slaughtered chickens/year for home consumption were 46.54 ± 29.44, and 1.46 ± 1.50, respectively, which were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in lowland areas. Generally, most of the performances of local chickens and chicken product consumption habits were poor in the areas. Therefore, agro ecological base improvement intervention about breed, feeds and feeding strategies, health care management, and awareness of households on product utilization are vital in the study area.

1. Introduction

Poultry is the largest group of livestock species in the world in which chickens are largely dominant in the flock composition (Alemneh & Getabalew, Citation2019). It includes all domestic birds kept for the purpose of food production (meat and eggs; Yonas, Citation2020). In Ethiopia, the word “poultry” is synonymous with domestic chicken (Gallus domesticus) due to almost non-existent sources of eggs and meat from other types of poultry in Ethiopia (Central Statistical Agency, Citation2021). The world has over 23 billion poultry which were about five times more than 50 years ago (FAOSTAT, Citation2016). Ethiopia possesses nearly 60% of the entire chicken population of the East Africa (Chaimiso, Citation2018). On the other hand, it is estimated to be 56.99 million chickens with 44.94 million indigenous (78.86%), 6.85 million hybrid (12.02%), and 5.19 million exotic breeds (9.12%; Central Statistical Agency, Citation2021). In Ethiopia, different indigenous chickens’ ecotypes are widely distributed in almost every rural family, few in private chicken producers and governmental institutions (Shumuye et al., Citation2018). Particularly, in the Amhara regional state of Ethiopia 19.06 million chickens (33.44% of the national) with 16.30 million indigenous (85.52%), 1.62 million hybrids (8.55%), and 1.13 million exotic (5.93%) were found (Central Statistical Agency, Citation2021).

The chicken industry raises the socio-economic standing of families in low- and middle-income nations and contributes to the involvement of weaker demographics including women, the crippled, orphans, and the unemployed (Kleyn & Ciacciariello, Citation2021; Manyelo et al., Citation2020; Mohamed et al., Citation2022). Similarly, in Ethiopia, chicken is crucial to improving nutrition and food security, domestic product growth, and employment possibilities (Bayesa, Citation2021).

Despite the large population and the great role of local chicken to the livelihood of resource-poor farmers in Ethiopia, the performances of chickens under smallholder production system is poor and varies in different area (Matawork, Citation2018). This is due to low hatchability and high mortality of chicks (Getachew et al., Citation2016). Though different chicken ecotypes are found in Amhara region, their productivity performances were low (Tamir et al., Citation2015). The report of Horst (Citation1989) also revealed that smaller body size, lateness in maturing (up to 36 weeks of age), low performances in egg numbers (20 to 50 per year) and lower egg weight (25 to 45 g), small clutch sizes (two to ten eggs/clutch), and long pauses between clutches and a predominant inclination to broodiness were the main production characteristics or performances of local chickens. It also in line with the finding of Haftu (Citation2016) that the egg production potential of local chicken is 30–60 eggs per year per hen, with an average of 38 g egg weight under village management conditions.

Though, chicken and chicken products are relatively affordable, high nutritional content and high potential for reducing stunting rates (Headey et al., Citation2018; Iannotti et al., Citation2014, Citation2017). Many people and children are facing severe food insecurity or stunted growth rate in different parts of the world particularly in developing countries (Muchenje et al., Citation2001; Ruel & Alderman, Citation2013). More particularly, in the Amhara regional state of Ethiopia about 47% of under 5 children are chronically stunted (Hirvonen & Wolle, Citation2019) and 23% of 15–49 years of age women are underweight (CSA & ICF, Citation2016).

In developing countries, eggs consumed/per capita/year (42 eggs) were very low as compared to 153 eggs in developed countries (FAO, Citation2013). In Ethiopia, the average chicken product consumed/per capita/year is 0.5 kg which is the lowest in the world (14.9 kg) and in sub-Saharan African countries (2.3 kg; Gueye, Citation1998). The consumption of chicken products in the Amhara region is estimated to be 14.8 million kg of meat and 105.7 million kg of eggs (Paulos, Citation2018). This low product consumption of people and the aforementioned problems could be due to the low production potential of chickens, poor management practices, and poor chicken product consumption habits of households.

To date, there were no detailed studies conducted in the region that did answer statements like chicken performances, the function of products, and product consumption habits of households’ in different agro ecologies. But, designing and implementing chicken-based development programs are not applicable without a detailed understanding of the above information (Gueye, Citation1998). Therefore, this study was conducted to describe agro ecological-based comparative performances evaluation of local chicken, major husbandry practices, and households chicken product consumption habits in the Amhara region.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

The study was conducted in Amhara region, Ethiopia. The region is located in the north-western and north-central part of Ethiopia. Amhara region is comprised of 13 administrative zones, 169 districts, and 3429 Kebeles (the smallest administrative units; BoARD (Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development), Citation2020). It is located between 9°20’ and 14°20’ North latitude and 36° 20’ and 40° 20’ East longitude. The area coverage is 170,752 km2 (”Ethiopian Government portal,” Citation2021).

The region has three main agro ecological zones, namely: high altitude (>2500 masl) 25%, mid-altitude (1500–2500 masl) 44%, and low altitude (<1500 masl) 31% (BoARD (Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development), Citation2020). The annual mean temperature for many parts of the region lies between 15 and 21°C. It receives the highest percentage (80%) of the total rainfall in the country (”Ethiopian Government portal,” Citation2021).

2.2. Sampling techniques

Multi-stage sampling procedure were employed namely: stratification, purposive, simple random, and proportionate allocation sampling techniques. From the total of 13 zones, three zones which have the highest chicken population (West Gojjam, Central Gondar, and South Wollo) were selected purposively based on chicken population and distribution patterns. All districts found in selected zones were stratified based on their agro ecological division highland (13), midland (28), and lowland (15) districts. For this study, 13 districts, 45 Kebeles, and 300 households were involved with Yamane (Citation1967) sample size determination formula.

Proportional sampling techniques were used to select study districts from each agro ecology (3 from the highland, 6 from the midland, and 4 from the lowland districts). Kebeles from the district were selected using simple random sampling procedures. Proportional sampling techniques was used for determination of household from the sampled Kebeles. Each respondent was selected with simple random sampling procedures from those households having chickens.

Therefore, the number of districts, Kebeles, and respondents was determined by Yamane (Citation1967) sample size determination formula with 95% confidence interval and 5% precision level.

Where;

N = the total population

n = the required sample size

e = the precision level with the above indicated

To get the distributions of sample size across each agro ecology division were calculate by using the following formula:

n’ = n(N’/N) … … … … … … … … … . (Israel, Citation1992)

2.3. Methods of data collection

Both primary and secondary data sources were used. The primary data was gathered via questionnaires, observation, and key informant interviews. Semi-structured questionnaire was developed to discover socio-economic characteristics of households, purposes of keeping chickens, flock dynamics and structure, feeds and feeding practices, disease management practices, productive and reproductive performance of chickens. Before administration, the questionnaire was translated into local language (Amharic) for easy of understanding. Field observations were also made to assess available chicken feed resource, feed and feeding practices, and other observable parameters of chicken production systems. Key informant interview including village leaders, youth, elders, women, and socially respected individuals were held to verify the collected information through questionnaire.

Secondary data on human and chicken population, agro ecology, topography, and other meteorological data’s were gathered from zonal and district livestock development and promotion offices. Published online accessible information was also used through internet browsing.

2.4. Data management and analysis

The collected data were organized, summarized, and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20.0. Analysis of variance procedure (one-way ANOVA) and descriptive statistics were employed. Least Significant Differences (LSD) tests were applied at 5% significant level to compare mean values of parameters in bases of agro ecology. Moreover, the qualitative data were analyzed with crosstabs χ2 square procedures to determine variation in agro ecology.

The statistical model was:

Yij = μ+Ai+eij;

Where, Yij = response variable (flock composition, management practices, product

utilization, chicken performances)

µ = overall mean,

Ai = the effect due to the itheffect of agro ecology and

eij = random error.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Demographic characteristics of respondents

Household characteristics of respondents including sex, family size, age, and educational background are presented in Table . The majority of the respondents (78.33%) in this study area were females. In all agro ecological division of the study area, the female respondents were numerically higher with compared to male respondents. This shows that the gender balance in house income distribution and chickens productions are closed to housewives in the home. This in line with the reports of Tadesse et al. (Citation2013) in Ada’a and Lume district of East Shewa of Ethiopia, Emebete (Citation2015, Citation2013) in southwest showa zone and Gurage zone of Ethiopia were 65.6% and 79.1% female households, respectively. In the contrary, Gebre Egziabher and Tsegay (Citation2016) reported that 85.40% were male headed in Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia.

Table 1. Respondent households’ characteristics by agro ecologies

The overall average family size of the respondents was 6.4 ±2.28. The current finding is similar to Worku et al. (Citation2012) who reported 6.02 ±24 in the western Amhara region and Fisseha et al. (Citation2010a) 6.19 ±2.17 in Burie district of Northwest Ethiopia. But, this is slightly higher than the national average of 4.6 (Central Statistical Agency, Citation2011) and 4.02 reported by Solomon et al. (Citation2013) in Metekel Zone, Ethiopia. The family size of respondents was significantly higher (p <0.05) in midland and lowland agro ecologies compared with the highland (Table ). But, Gebre Egziabher and Tsegay (Citation2016) reported that family size was no significant differences among agro ecologies in Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia.

The overall average age and major literacy background of respondents were 45.19 ±12.40 years and 54.67% with illiteracy profile, respectively. In lowland agro ecology, the illiteracy figures of respondents were higher (68.82%). This high proportion of illiterate individuals in a farming community could be a drawback for easily adoption of improved technologies (Gebre Egziabher & Tsegay, Citation2016).

3.2. Composition and flock structure

The overall chicken flock size per households in the study area was 7.16 ±3.02 (Table ). This is similar with the report of Gebre Egziabher and Tsegay (Citation2016) who revealed (7.2 ±0.46) in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. The current result was much lower than the report in other country, Myanmar, Yangon district, where the average flock size was 30 birds (Henning et al., Citation2007), BurkinoFaso 33.5 birds (Kondombo et al., Citation2003), and Zimbabwe 30 birds (Mapiye & Sibanda, Citation2005). In areas like Niger and Myanmar, there is a practice of keeping other species of poultry like ducks, turkeys, Guinea fowl, the pigeons (15.51%), and geese (Henning et al., Citation2007; Moussa et al., Citation2019) while there were no other bird species in Ethiopia. Chicken flock sizes per household were in the order of midland ≥ lowland>highland agro ecologies. Chicken holding per households in highland agro ecology (6.22 ±2.51) was significantly lower (P <0.05) than midland (7.62 ±3.28) and lowland (7.28 ±2.89) agro ecologies. Similarly, the average flock size of the midland was ranked first (8.7) in Ethiopia (Minyahel et al., Citation2021). The current finding revealed that the dominant flock composition were hens (2.44 ±0.92) followed by pullets (2.07 ±1.21). This is supported with the finding of Fisseha (Citation2014), who indicated 2.79 ±0.4 hens/households in north-western Amhara region, Ethiopia. But, young chicken were the first dominant flock structure in different parts of Ethiopia (Addis & Malede, Citation2014; Nebiyu et al., Citation2013; Wondu et al., Citation2013). The flock composition of cockerel (0.36 ±0.56) and hens (2.16 ±0.8) in the highland agro ecology were lower significant variation (p <0.05) than midland and highland agro ecology.

Table 2. Chicken holding and flock composition per household

Using of chicken and chicken products as income generation (72.67%), family nutrition (72.00%), and social and religious function (58.33%) were the identified purposes for chicken rearing without significant variation in the three agro ecologies. In line with this finding the main purpose of chicken production in Myanmar was primary to generate cash income from the sale of chickens with a value of 64% followed by for consumption of chickens (Henning et al., Citation2007). A similar study conducted in Niger also found that chickens are primarily produced for selling (38.31%) and self-consumption (37.74%; Moussa et al., Citation2019). In the current study, 12.33% of respondents were depending on chicken rearing as a sole job for their livelihoods. But, the major of respondents (87.67%) practiced chicken rearing as part-time jobs.

3.3. Management practices of chickens

3.3.1. Feed and disease management of chicken

In the study area, the majority of the households (71.00%) were providing supplementary feed(). Similarly, Fisseha et al. (Citation2010a) in Northwest Ethiopia and Henning et al. (Citation2007) in Myanmar reported that 97.5%, and 99% of chicken owners were offered supplementary feeds, respectively. This disagrees with the finding of Moussa et al. (Citation2019), who reported that 11.6% of chicken producers in Niger practiced dietary supplementation. The current study also confirmed that supplementary feeding practices were highly significant difference (p <0.05) on agro ecology bases. In midland (87.69%), highland (72.73%), and lowland (46.24%) respondents were offered supplementary feeds. This low percentage of feed supplementation of households in lowland agro ecology could be due to insufficient grain availability, high cost of commercial ration, lack of awareness, and high level of illiteracy percentage. The high cost of commercial poultry feed discourages farmers for supplementing chicken (Haftu, Citation2016). In the study area, widely used supplementary feed ingredients were maize (65.67%) followed by wheat (48.33%) and sorghum (35.33%), which was not similar with the report of Henning et al. (Citation2007) according to which the main supplementary feeds in Myanmar were rice (91%) followed by food scraps (33%). The types of feed offered were significantly varied (p <0.05) with agro ecologies. The dominant feed in lowland agro ecology were sorghum (62.37%) followed by maize (54.84%), in midland wheat (84.62) followed by maize (61.54%), in highland maize (85.71%) followed by barley (53.25%). This result showed that maize was among the two most supplemented grains in the three agro ecologies.

Table 3. Major management practices of chicken in the study area

The survey revealed that 57.33% of chicken owners were experienced disease problems within six months’ time period especially before and at rainy season (). The challenge of disease problem is significantly sever in lowland (72.04%) and highland (67.53%) than midland agro ecology (40.77%). In the study area, ethno veterinary or traditional medicine treatments of ill chicken were commonly practiced (81.67%). Medicinal plants Feto and Damakessie were the highest used ethno veterinary for chickens (64.33%) without agro ecological base differences. Garlic was significantly used (77.92%) in the highland agro ecology for chicken treatment in the study area. In Niger, among the traditional treatments of parasitosis disease, Ash (56.63%), Pia-pia (insecticide) (16.94%), and Pia-pia and ash mixture (10.17%) are the most commonly used treatment options (Moussa et al., Citation2019).

3.3.2. Productive and reproductive performances of chickens

The study indicated that the annual egg production performance of local chickens was (61.91 ±5.70). Similarly, Fisseha et al. (Citation2010a) and Alemneh and Getabalew (Citation2019) reported that 30–60 eggs/year/hen production in Ethiopia. This study also revealed that the number of eggs/hen/clutch and number of clutch frequency/hen/year were 14.34 ±1.69 and 3.44 ±0.44, respectively. The annual egg production, average number of egg/clutch, and total number of clutch/hen/year in different agro ecology had a significant difference (p <0.05) with the order of midland > lowland ≥ highland, midland > highland > lowland, lowland> highland ≥midland agro ecologies with respective performance parameters. The lower number of eggs per hen per year in the highland and lowland area could be attributed to extended period of time after clutch compared to the midland agro ecology.

The average age of local cockerels at first mating, pullets at first egg laying, average numbers of egg set/brooding hen were 5.76 ± 0.68 months, 6.26 ±0.26 months, and 11.95 ±1.55, respectively (Table ). Similarly, twelve eggs produced per batch were found to be the chicken productive potential in Myanmar (Henning et al., Citation2007). In the midland areas, age at first mating of cockerels (5.49 ±0.62) and number of egg per brooding hen (12.50 ±1.20) were significantly higher (P <0.05) than other agro ecologies. The study indicated that survived chick to market age and male ages at slaughter were 66.45 ±6.83%, and 9.16 ±1.02 months, respectively. These were highly significant different (P <0.05) in the agro ecologies. Lower survival percentage of chicks (64.0 ±45.61) and late ages of male for slaughter (9.86 ±0.75) were found in lowland agro ecologies. Relatively short age (5 months) at slaughtering was recorded in Enebsie Sar Midir district, Ethiopia (Melkamu & Andargie, Citation2014).

Table 4. Production and reproduction performance of local chickens in different agro ecologies of the study area

Number of egg hatched per incubation and hatchability percentage on total egg set were 9.60 ±1.36, and 79.90 ±4.48, respectively. Similarly, the report of Melkamu and Andargie (Citation2014) on number of hatched chicks/brooding in Enebse Sar midr district was 9. This also agrees with Yizengaw et al. (Citation2019) report that indicated hatchability rate of indigenous chicken eggs were 78.6–85.8% in Ethiopia. These were highly significant different (P <0.05) in the agro ecologies. The higher average number of egg hatched (10.35 ±1.23) and the maximum hatchability percentage (83.52 ±2.82) were recorded in midland and highland area, respectively. However, according to the research conducted in Nigeria, the hatchability percentage was found to be higher compared to 55% for FUNAAB Alpha and lowest compared with 89% for Sasso, respectively (Bamidele et al., Citation2020). This difference could be due to breed difference, management practices, and other environmental factors of the areas.

3.3.3. Households consumption of chicken and chicken products

The current finding showed that 77.33% and 32.33% of interviewed households used chicken egg, and meat for household consumption, respectively. In the study area, chicken products also used for celebration of social and religious festival (26.67%; Table ). In line with this finding, Henning et al. (Citation2007) found that overall a large proportion (93%, n =276) of farmers ate their own chicken egg in Myanmar. But in similar research, the authors found that the proportion of home produced meat consumption accounts only 7%. The key informant interview information supported that few households used chicken products in both households (HHS) consumption and festival celebration. Product consumption habit of households (egg and meat) had significant difference (p <0.05) in the agro ecologies. The egg and meat consumption habit of households were higher in midland agro ecologies, 83.08% and 41.54%, respectively. Using of chicken and chicken products for celebration of cultural and religious festival were not significant different in the agro ecologies while there were numerically higher (29.87%) in the highland area. Information from focus group discussion showed that most farmers consume chicken meat at the holiday’s especially Christian festivals like Easter. But, egg consumption habit of household was better in the other days of holiday compared with meat. However there were no any cultural or religious taboos against consumption of chicken meat and eggs in the study area.

Table 5. Household chicken and chicken product consumption habit in the last 12 months

The study found that number of eggs consumed/per capita/year in the family was 46.54 ±29.44. This is far lower than in developed countries which is 153 eggs per year (FAO, Citation2013). The annual number of eggs consumed by individually in the lowland area (34.26 ±25.15) was significantly lower (P <0.05) than other agro ecologies. This finding was relatively higher than the finding conducted in Enebsie Sar Midir district where the average number of eggs utilized by the households for consumption was only 15.7% (Melkamu & Andargie, Citation2014).

The present finding revealed that 1.46 ±1.50 average numbers of chicken were slaughtered for home consumed/per capita/year. However, in southern Ethiopia the annual average number of slaughtered chicken for family consumption was 5.9 (Mekonnen, Citation2007), which is much lower than the report of Yilmaz et al. (Citation2013) which showed the total monthly households’ consumption of chicken meat was 3.31 kg in Turkish. The annual average numbers of slaughtered chicken per household in midland agro ecology (1.70 ±1.64) were highly significantly different (p <0.05) compared with other agro ecologies. Though, highland and lowland agro ecology had no significant differences (P >0.05).

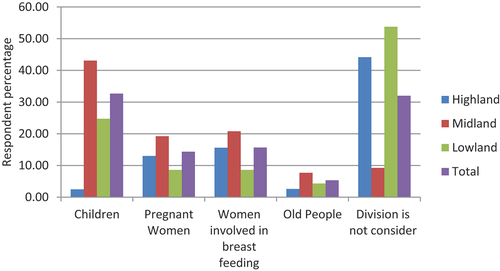

From the total respondents, 32.00% indicated that chicken products consumption is done without giving priority within the family group. Respondents who gave priority for children, women involved in breast feeding, and pregnant women were 32.67%, 15.67%, and 14.33%, respectively (Figure ). This showed that the first prioritized family groups for consumption of chicken products were children. This study indicated that chicken product consumption family groups priority regarding agro ecology division includes highland (44.16%) no priority, midland (43.08%) priority for children, and lowland (53.76%) no division of family group for chicken product consumption. This could be the socio-economic factors like age, income, education and family size significantly determines consumers’ willingness to pay for chicken products in Kenya (Bett et al., Citation2013).

4. Conclusion and recommendation

In the study area, the majority of households practiced chicken rearing as part-time jobs that support their livelihoods. Though flock structures were different in agro ecologies, hens and pullets were dominant in the study area. Disease and feed shortage were also found to be major problems in different agro ecologies of the study area. Ethno veterinary or traditional medical treatments of ill chicken were commonly practiced. The productive and reproductive performances of local chickens were lower compared with the scientific standard, and there were differences in the highland, midland, and lowland agro ecologies of the study region. Most of the performances potential of local chicken in lowland agro ecology were very poor compared with other agro ecologies of the area. Though chicken products were used for income generation, family nutrition, and the celebration of cultural and religious festivals. In the study area, household product consumption was found to be very low compared with standards set by FAO. Therefore, agro-ecological-based improvement training of breed, feeds and feeding strategies, health care management, and awareness of households on product utilization are vital in the study area.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Authors contribution

HA carried out the organization and drafting of the manuscript. All authors were participated in data collection, evaluating and editing the paper, and approval of the final manuscript.(Citation2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge University of Gondar and College of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences for funding the facilities, materials and budget of this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no any conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship or publications of this manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in “figshare” at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20009492.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Habtamu Ayalew

Habtamu Ayalew is an Assistant professor of Animal Production at University of Gondar, Ethiopia. He awarded his MSc degree from Bahir dar University, Ethiopia. He has ample experiences in teaching and research works. He has conducted various research activities, and published more than 17 publications in national and international reputable journals. Other co authors of the manuscript are also working in University of Gondar in different position.

References

- Addis, G., & Malede, B. (2014). Chicken production systems, performance and associated constraints in North Gondar zone, Ethiopia. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 10, 25–15. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wjas.2014.10.1.1768

- Alemneh, T., & Getabalew, M. (2019). Exotic chicken production performance, status and challenges in Ethiopia. International Journal of Veterinary Science and Research, 5(2), 039–045. http://dx.doi.org/10.17352/ijvsr.000040

- Bamidele, O., Sonaiya, E. B., Adebambo, O. A., & Dessie, T. (2020). On-station performance evaluation of improved tropically adapted chicken breeds for smallholder poultry production systems in Nigeria. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 52(4), 1541–1548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-02158-9

- Bayesa, T. (2021). Current status of indigenous and highly productive chicken breeds in Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 8848388, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8848388

- Bett, H. K., Peters, K. J., Nwankwo, U. M., & Bokelmann, W. (2013). Estimating consumer preferences and willingness to pay for the underutilized indigenous chicken products.J. Food Policy, 41, 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.05.012

- BoARD (Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development). (2020). Agricultural sample survey. Report on Livestock and Livestock Characteristics, Vol. II (Accessed February, 2020), Addis Ababa.

- Central Statistical Agency. (2011). Agricultural sample survey report on livestock and livestock characteristics, volume ii, statistical bulletin 532. Addis Ababa.

- Central Statistical Agency. (2021). Agricultural sample survey on livestock and livestock characteristics. volume ii, statistical bulletin 589. Addis Ababa.

- Chaimiso, S. (2018). Review on village/backyard/poultry production system in Ethiopia. Pacific International Journal, 1, 33–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.55014/pij.v1i3.56

- CSA & ICF. (2016). Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016, Addis Ababa. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia and ICF.

- Emebet, M.B. (2015). Phenotypic and Genetic Characterization of Indigenous Chicken in Southwest Showa and Gurage Zones of Ethiopia. PhD Dissertation, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 127.

- Emebet, M., Hareppal, S., Johansson, A., Sisaye, T., & Sahile, Z. (2013). Characteristics of indigenous chicken production system in South West and South part of Ethiopia. British Journal of Poultry Sciences, 2(3), 25–32. https://dx.doi.org/10.5829/idosi.bjps.2013.2.3.7526

- Ethiopian government portal (2021): AMHARA demography and health. http://www.ethiodemographyandhealth.org/Aynalem_Adugna_Amhara_January_2021.pdf .Accessed March 22, 2022

- FAO. (2013). Food and agriculture organization statistical database on livestock. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. Italy.

- FAOSTAT.(2016). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).FAOSTAT Database.http://faostat.fao.org/site/291/default.aspx

- Fisseha, M. (2014). Chicken production and marketing systems in enkulal watershed, dera district, Amhara region. Ethiopia World’s Veterinary Journal, 4, 35–41. https://dx.doi.org/10.5455/wvj.20141043

- Fisseha, M., Abera, M., & Tadelle, D. (2010a). Assessment of village chicken production system and evaluation of the productive and reproductive performance of local chicken ecotype in Bure district, North West Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 5, 1739–1748. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR

- Gebre Egziabher, Z., & Tsegay, L. (2016). Production and reproduction performance of local chicken breeds and their marketing practices in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 11(17), 1531–1537. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2015.10728

- Getachew, B., Kefelegn, K., & Negassi, A. (2016). Study of indigenous chicken production system in bench Maji Zone, South Western Ethiopia. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: D Agriculture and Veterinary, 16, 21–30.

- Gueye, E. F. (1998). Village egg and fowl meat production in Africa. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 54(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1079/WPS19980007

- Haftu, K. (2016). A review exotic chicken status, production performance and constraints in Ethiopia. Asian Journal of Poultry Science, 10, 30–39. https://dx.doi.org/10.3923/ajpsaj.2016.30.39

- Headey, D. D., Hirvonen, K., & Hoddinott, J. F. (2018). Animal sourced foods and child stunting. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(5), 1302–1319. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay053

- Henning, J., Pym, R., Hla, T., Kyaw, N., & Mee, J. (2007). Village chicken production in Myanmar –purpose, magnitude and major constraints. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 63(2), 308–322. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043933907001493

- Hirvonen, K., & Wolle, A. (2019). Consumption, production, market access and affordability of nutritious foods in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa. Alive & Thrive and International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Horst, P. (1989). Native fowl as a reservoir for genomes and major genes with direct and indirect effects on adaptability and their potential for tropically oriented breeding plans. A review. Animal Research Development, 33, 63–69.

- Iannotti, L. L., Lutter, C. K., Bunn, D. A., & Stewart, C. P. (2014). Eggs: The uncracked potential for improving maternal and young child nutrition among the world’s poor. Nutrition Reviews, 72(6), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/nure.12107

- Iannotti, L. L., Lutter, C. K., Stewart, C. P., Riofrío, C. A. G., Malo, C., Reinhart, G., Cox, K., Karp, C., Chapnick, M., Cox, K., & Waters, W. F. (2017). Eggs in early complementary feeding and child growth: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 140(1), e20163459. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3459

- Israel, G. D. (1992). determining sample size. University of florida cooperative extension service. Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, EDIS.

- Kleyn, F. J., & Ciacciariello, M. (2021). Future demands of the poultry industry: Will we meet our commitments sustainably in developed and developing economies? World’s Poultry Science Journal, 77(2), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00439339.2021.1904314

- Kondombo, S. R., Nianogo, A. J., Kwakkel, R. P., Udo, H. M. Y., & Slingerland, M. (2003). Comparative analysis of village chicken production in two farming systems in Burkina Faso. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 35(6), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027336610764

- Manyelo, T. G., Selaledi, L., Hassan, Z. M., & Mabelebele, M. (2020). Local chicken breeds of Africa: Their description, uses and conservation methods. Animals, 10(12), 1–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ani10122257

- Mapiye, C., & Sibanda, S. (2005). Constraints and opportunities of village chicken production systems in the smallholder sector of Rushinga district of Zimbabwe. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 17, 115. https://www.lrrd.cipav.org.co/lrrd17/10/mapi17115.htm

- Matawork, M. (2018). Productive and reproductive performance of indigenous chickens in Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 9(10), 253–259. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2018.0451

- Mekonnen, G. E., (2007). Characterization of the Small Holder Poultry Production and Marketing System of Dale, Wonsho and Lokaabaya Weredas of SNNPRS. MSc Thesis. Hawassa University. Awassa.

- Melkamu, B. Y., & Andargie, Z. (2014). Performance evaluation of local chicken at enebsie sar midir Woreda, Eastern Gojjam, Ethiopia. Global Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences Research, 1, 1–8. https://www.gbjournals.org/journals/global-journal-agriculture-food-sciences-research-gjafsr/vol-1-issue2-june-2014/performance-evaluation-local-chicken-enebsie-sar-midir-woreda-eastern-gojjam-ethiopia/www.gbjournals.org

- Minyahel, T., Mosa, M., & Wondossen, A. (2021). Agro ecology is affecting village chicken producers’ breeding objective in Ethiopia. Hindawi Scientifica, 2022, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9492912

- Mohamed, E., Mohamed, T., Heba, M., Amira, M., Mohamed, M., Gehan, B. A., Taha, A. E., Soliman, S. M., Ahmed, A. E., El-kott, A. F., Al Syaad, K. M., & Swelum, A. A. (2022). Alternatives to antibiotics for organic poultry production: Types, modes of action and impacts on bird’s health and production. Poultry Science, 101(4), 101696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.101696

- Moussa, H. O., Keambou, T. C., Hima, K., Issa, S., Motsa’a, S. J., & Bakasso, Y. (2019). Indigenous chicken production in Niger. Journal of Veterinary and Animal Science, 7, 100040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vas.2018.11.001

- Muchenje, V., Manzini, M. M., Sibanda, S., & Makuza, S. M. (2001). Sustainable animal agriculture and crisis mitigation in livestock-dependent systems in S. Socio-economic and biological issues to consider in smallholder poultry.

- Nebiyu, Y., Berhan, T., & Kelay, B. (2013). Characterization of village chicken production performance under scavenging system in Halaba district of Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 17, 69–80. http://www.ajol.info/…/archive

- Paulos, D. (2018). Poultry value chain in West Amhara. Commissioned by programme for agro-business induced growth in the Amhara national regional state. Bahir Dar. https://www.agrobig.org/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2019/03/Poultry-Value-Chain-Analysis-Sept-2018.pdf. Accessed Mar 26, 2022

- Ruel, M. T., & Alderman, H. (2013). Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? The Lancet, 382(9891), 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60843-0

- Shumuye, B., Resom, M., Haftom, Y. G., & Amare, H. (2018). Production performance evaluation of koekoek chicken under farmer management practice in Tigray region, northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 9(9), 232237. http://dx.doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2017.0436

- Solomon, Z., Binyam, K., Bilatu, A., & Ferede, A. (2013). Village chicken production system in Metekel zone, North West Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Research, 2, 256–262.

- Tadesse, D., Singh, H., Mengistu, A., Esatu, W., & Dessie, T. (2013). Study on management practices and marketing systems of village chicken in East Shewa, Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 22, 2696–2702. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2013.6989

- Tamir, S., Moges, F., Tilahun, Y., & Hile, M. (2015). Determinants of adoption of exotic poultry breeds among smallholder poultry producers in North Western Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Global Science Research Journal, 3, 162–168. https://www.globalscienceresearchjournals.org/

- Wondu, M., Mehiret, M., & Berhan, T. (2013). Characterization of urban poultry production system in Northern Gondar, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America, 4(3), 192–198. https://doi.org/10.5251/abjna.2013.4.3.192.198

- Worku, Z., Melesse, A., & TGiorgis, T. (2012). Assessment of village chicken production system and the performance of local chicken population in West Amhara region of. Ethiopia .journal of Animal Production Advances, 2, 199–207.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, an Introductory Analysis (2nd) ed.). Harper and Row.

- Yilmaz, A., Erol, A., Pınar, D., Ahmet, C. A., Yavuz, C., Çagla, K. K., & Mehmet, A. (2013). Consumer preferences and consumption situation of chicken meat in Ankara Province. Turkey. Turkish JOURNAL OF VETERINARY AND ANIMAL SCIENCES, 37, 582–587. http://dx.doi.org/10.3906/vet-1210-36

- Yizengaw, M., Ewonetu, K., & Ashenafi, G. (2019). Review of chicken productive and reproductive performance and its challenges in Ethiopia. All Life, 15, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895293.2021.2024894

- Yonas, K. (2020). Production performance of chicken under farmers’ management and their roles at urban household economy in Southern Ethiopia. Agricultural Sciences, 11(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2020.112011