?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Smallholder farmers have for a long time preferred to sell at the farm gate, where the prices have been very low compared to market places. This has been fueled by several challenges related to market participation. The purpose of this study is therefore aiming at developing an empirical understanding that uncovers whether digital technology can mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and market participation. Entrepreneurship and digital technology are novel concepts in agriculture, especially for smallholder farmers. Therefore, this study presents new insights on how the challenges of market participation can be solved through entrepreneurial networks and digital technology. The study used validated items adopted from previous studies, from which the structured questionnaires were distributed to 298 smallholder farmers. In addition, structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to analyse relationships in which digital technology was found to be a mediator of the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and market participation among smallholder farmers. Further, the study suggests that smallholder farmers can overcome challenges and increase market participation if they change their attitudes through training conducted by rural extension officers and embrace digital technologies by designing new or joining existing entrepreneurial networks.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The inability of smallholder farmers to participate in markets has been one of the most significant challenges facing developing countries. Because of this, many rural households have poor living standards. Hence, there have been a number of different efforts put forth in order to raise the level of market participation. The purpose of this study is to make a contribution by putting an emphasis on the significance of entrepreneurial networks and digital technologies for enhancing market participation. This is due to the fact that smallholder farmers are characterized by inadequate resource endowments, inadequate technology bases, and a lack of sufficient skills and knowledge. So, being a part of networks can help them to have collective bargaining, which can make it more likely that they will adopt digital technologies and, as a result, give them more opportunities to participate in the market.

1. Introduction

Smallholder agriculture has been the dominant economic activity in the Sub-Saharan region for a long time, and it will continue to be tremendously important for the foreseeable future in the region (Gollin, Citation2014; Ismail, Citation2014; Ismail & Changalima, Citation2019). According to (Geng et al., Citation2022) farming is one among the sustainable practices which can increase the regular sources of income among households. Generally, smallholder farmers are the primary source of income and employment possibilities and the primary source of food security (Ismail, Citation2020; Megerssa et al., Citation2020; Mhagama et al., Citation2021). However, in terms of the supply side, food supply has been a challenge for a very long time (Zhuang et al., Citation2022). This is because, the subsistence nature of the sector, characterized by the low level of market integration, inadequate trade information, inadequate technologies, insufficient infrastructure, inaccessibility, and insufficient mechanisms to enforce contracts, continues to be significant obstacles (Andaregie et al., Citation2021; Hagos & Zemedu, Citation2015; Ismail, Citation2022a; Megerssa et al., Citation2020). Thus, there is a significant food sufficiency gap and food insecurity in households. The move from subsistence to commercial agriculture, commonly called “agricultural commercialization,” has long been seen as a vital component of the low-income economy’s rural transformation.

The concept of commercialization is not confined to the sale of surplus products in marketplaces. It must consider both the inputs and outputs of production and the decision-making behaviour of farmers in both the production and marketing of their products (Ismail, Citation2021). Therefore, commercialized farmers must consider market demand while making production decisions rather than just selling some of the goods owing to a surplus of output (Changalima & Ismail, Citation2022; Raj & Hall, Citation2020). Even more concerning, despite much debate about “agriculture as a business,” there is very little information available in the body of literature about entrepreneurship in the agricultural industry. This is particularly clear in the smallholder sector due to a lack of an entrepreneurial culture and a commercial attitude among smallholder farmers, and the absence of a clear distinction between farm and family operation (Wale et al., Citation2021). Evidence from industrialized countries demonstrates that smallholder farmers can be regarded as business owners and entrepreneurs, notwithstanding the unique circumstances in developing countries (Richards & Bulkley, Citation2011). This suggests that if smallholder farmers receive the necessary support, they have the potential to become successful entrepreneurs in their own right. That means, smallholder farmers’ performance can be improved, and rural development efforts can be scaled up, in part through encouraging entrepreneurial behavior in the sector (Wale et al., Citation2021). Generally, entreprenurial behaviour is considered to be a key human resource for seeing opportunities. As noted by Asad et al. (Citation2017), human resource is important for utilizing other resources such as monetary resources for the uppermost efficiency and effectiveness of business activities.

Entrepreneurial behavior can assist them in reorganizing their farms more efficiently by identifying alternative technologies, diversifying production, being market-oriented and being innovative by identifying and seizing opportunities (Kahan, Citation2012). According to X. Li et al., (Citation2022), entrepreneurship is crucial in creating social value. Nevertheless, a critical entrepreneurial characteristic that smallholder farmers may benefit from is the presence of entrepreneurial networks. Although entrepreneurial networks among smallholder farmers have received little attention in prior research, multiple studies on ordinary networks have discovered that, when implemented effectively, networks can significantly facilitate production and increase market access (Ismail, Citation2022b). In some rural areas, establishing farmer networks is a fundamental method of reducing liquidity and financial risk (Kisaka-Lwayo & Obi, Citation2012).

Additionally, similar to non-agricultural firms, entrepreneurial networks can help smallholder farmers become more dynamic, innovative, and competitive by connecting them with other like-minded individuals. Furthermore, it also helps individuals identify economic opportunities, develop and implement them, share information, and find potential business partners for new ventures (Abbas, Raza et al., Citation2019). A study by Windsperger et al. (Citation2018) on “Governance and strategy of entrepreneurial networks” discovered that entrepreneurial networks are used to reduce transaction costs while simultaneously increasing the strategic value of products. This means that for smallholder farmers, entrepreneurial networks can provide a means of benefiting from collective marketing as well as a means of reducing market challenges such as transportation costs and increasing bargaining power among themselves. Apart from that, networks are associated with technological advancement. Due to complexity of today’s world, technological advancements such as internet applications has been considered to be a vital component for attaining skills (Lebni et al., Citation2020). A study by Hampton et al. (Citation2009) noted that it is feasible to infer that agri-entrepreneurs in networks can gain access to interactions that can supply entrepreneurial resources such as technological-based resources. Likewise, accessing technologies such as social media technology has provided a platform for business firms to interact and communicate with customers, suppliers, retailers, and other stakeholders.

According to the findings of Liu et al. (Citation2022), the enduring global economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic has caused shocks to develop in both the demand and supply sides of various product categories. As a result, digital technology has proven to be an invaluable resource (Al Halbusi et al., Citation2022; Su et al., Citation2022). In a similar vein, Brahmbhatt et al. (Citation2021) posted that the COVID −19 pandemic brought to light the necessity of shifting to technology as a strategic intervention in order to reach full potential outcomes. This technology serves several purposes, including those related to green technology innovations to marketing and communication activities. For instance, a study by Jiakui et al. (Citation2023) suggested that technologies have a significant impact on reducing the deterioration of the environment, particularly by capitalising on practises that are friendly to the environment.

Aside from that, applications for social media marketing typically make the exchange of information and the process of content generation through technological advances easier, both of which have the potential to significantly contribute to an improvement in the performance of businesses (Abbas, Mahmood et al., Citation2019; Yu et al., Citation2022). This is supported by Aman et al. (Citation2019) who suggested that in the recent digital age, policy on digitalization, social media and emerging technologies are crucial for development.

Also, as proposed by Balkrishna and Deshmukh (Citation2017), the use of social media (digital marketing) can assist farmers in obtaining knowledge about farming and marketing their products using mobile applications. Khou and Suresh (Citation2018) also agreed that there is a link between technological-based resources and the marketing of agricultural products in the marketplace. This is maintained by Pittaway et al. (Citation2004) who noted that there is a direct tie between entrepreneurial networks and a firm’s access to innovations through the collective learning and complementary skills available in networks. Similarly, Ge et al. (Citation2022) insisted that entrepreneurship and technological innovation are important concepts for improving skills, creating job opportunities, and executing new ideas. This means, entrepreneurial networks can offer several benefits to smallholder farmers, which can result in the accessibility of digital technology, which can increase chances for market participation.

Specifically, a study by Felzensztein et al. (Citation2010) classified networks into three broad groups. The first type of network is an exchange network, in which entrepreneurs benefit from business partnerships that promote transactions between participants. Secondly, communication networks are the second type of network that entrepreneurs can join to benefit from the flow of business information and connect with other entrepreneurs. The third type of network is social networks, which are based on formal and informal relationships such as family members, friends, and other relationships that support entrepreneurs.

This study has made some contributions to the body of literature. First, the concepts of entrepreneurship and digital technology are novel in agriculture, particularly for smallholder farmers; thus, the presented relationships in this study provide very rare initiatives and new insights into addressing long-standing market participation challenges. Secondly, there is no scientific information on how digital technology can mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and smallholder farmers’ decisions to participate in the market. To do this, the goal of this study is to find out how smallholder farmers in Tanzania can use digital technology to participate in the market through strategic entrepreneurial networking.

1.1. Theoretical review

Entrepreneurial networking serves as the independent variable in this study, with digital technology serving as the mediating variable. When these variables interact, it is likely smallholder farmers’ decisions to participate in markets will be more favorable (Figure ). Several theories can be used to investigate this link in general; however, the researchers chose to use the networking and resource dependency theories.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

1.2. Networking theory

The network perspective on entrepreneurship is a prevalent theoretical perspective in the entrepreneurship literature. Entrepreneurs have access to a wealth of helpful resources through their business networks. Generally, the primary purpose of an entrepreneurial network is to provide entrepreneurs with the capacity to expand their sources of resources, knowledge, guidance, and emotional support. The entrepreneur’s relatives, in particular, are regarded as the most trustworthy network members (Bratkovic et al., Citation2009).

Most smallholder farmers in developing countries work on a small scale and are geographically isolated. This is different from large-scale farmers in developed countries, who have access to well-established infrastructure (Fafchamps & Hill, Citation2005). This means small-scale firms can decrease risks and costs by establishing a proper relationship with their stakeholders (Mubeen et al., Citation2020) in the networks, which can in turn result in high market accessibility. Furthermore, it is important to note that small firms seek to build a knowledge-friendly strategy to help them share, transmit, and reuse valuable insights (Abbas et al., Citation2020). Thus, entrepreneurial networks are critical since they enable the pooling of resources and thus the increased capacity to deal with the obstacles connected to market participation. The theoretical perspective that underpins networking theory, on the other hand, emphasizes the capacity to expand the flow of information, the development of resources, and the provision of support and advice among members. This suggests that networks might be used to strategically assist entrepreneurs (smallholder farmers) in exploring opportunities and expanding their operations (Vasilchenko & Morrish, Citation2011). There is no doubt that accessing technological innovations can help in reducing poverty (Fu et al., Citation2021) among poor households.

As it has already been said, innovative networks are seen as ways to share limited resources, handle complicated innovation processes, deal with technical uncertainty, and give everyone involved a chance to learn something new (Torok et al., Citation2018). This study theorizes that by joining entrepreneurial networks, smallholder farmers can be connected to a variety of benefits that are more likely to bring innovative technological resources, such as the application of digital technology, and, as a result, increase their chances of participating in the market.

1.3. Resource dependency theory

A scarcity of resources characterizes smallholders. This has resulted in poor performance of smallholder agriculture, increasing the likelihood of food insecurity in the future. Smallholder farmers must be organized into networks to enhance productivity while improving their living standards and food security. By doing so, they will be able to increase their resource base. They can compete with large-scale farmers and items imported from other nations by pooling their resources and forming networks of like-minded individuals. This meaning is consistent with resource dependency theory, which asserts that organizations can achieve their objectives through managing their interdependencies with other entities (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978). This indicates that organizations are deficient in resources. Therefore, they are forced to pursue innovations such as joining networks to increase their chances of embracing new alternative resources such as digital technology. However, for resources to be productive communities must adopt and manage them properly (Hussain et al., Citation2017).

This study theorizes that smallholder farmers must rely on outside sources for their inputs and other resources. As a result, they must interact with their fellow smallholder farmers, suppliers of farming materials, financial institutions, and distributors of their products to succeed. It is theorized that by utilizing entrepreneurial networks as the foundation for alliances, smallholder farmers will gain access to digital technology tactics, increasing their chances of success in the marketplace.

1.4. Literature review and hypothesis development

1.4.1. Exchange entrepreneurial network and digital technology

According to Zhang et al. (Citation2022), when making decisions for the business, the primary objective should be to increase its value. The available evidence suggests that entrepreneurs increase the value of their companies by leveraging resources through networks in order to circumvent resource limitations caused by factors such as the progression of technology. It has been demonstrated to be an important determinant of behavior in trading networks for smallholder farmers. Past studies have related exchange networks with digital technologies such as mobile phones, WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other online-based digital media. Smallholder farmers can improve their digital technology through improving connections with traders and customers of their products, thereby increasing their market participation.

A study by Kiprop et al. (Citation2019) noted the connection between networks and technology by posting that networks to farmers are considered as a platform to lower transaction costs through cost-sharing and a means for boosting access to money to lay the groundwork for strengthening farmer-technology connections. It has also been mentioned by Jiang et al. (Citation2018) that the exchange relationships established through networks can assist smallholder farmers in utilizing digital technology by sharing information and experiences among members. This is reinforced by Wolfenden (Citation2020) who pointed out that small businesses, which have the same “small size” problems as smallholder farmers, can use networks to help them deal with problems with digital technology. Also Jones et al. (Citation2014) discovered that business owners (in this case, smallholder farmers) who are enthusiastic about technology can maintain this enthusiasm through a support network where ideas and knowledge can be free and open.

Additionally, O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2009) observed that business networks, whether formal or informal, can lead to incremental innovations in services and procedures, as well as a competitive edge. Further Jones et al. (Citation2013) echoed this fact by admitting that there is a positive relationship between networks and new technology. It can therefore be hypothesized that

Hypotheses H1: Exchange entrepreneurial networks significantly influence digital technology among smallholder farmers

1.4.2. Communication entrepreneurial network and digital technology

Communication networks are primarily intended to aid farmers in managing their information (Negi et al., Citation2018). Intermediaries and traders have historically taken advantage of smallholder farmers’ limited access to market information to exploit them during pricing negotiations. According to Zafar et al. (Citation2022), The provision of accurate information is a crucial component of successful marketing, particularly with regard to the repurchasing decisions of existing clients. Because of this information advantage, dealers and intermediaries can negotiate cheaper rates than they would have if there were no information asymmetries (Negi et al., Citation2018). Although few studies have been conducted, those conducted reveal a positive association between communication networks and agricultural technological developments. According to a study by Wahyuni et al. (Citation2016), agricultural technology innovation adoption is more effective when farmers have communication networks, as communication networks between people and groups result in knowledge sharing among farmers. Also Prasetiyo et al. (Citation2021) discovered that networks improve the likelihood of knowledge and information being disseminated, hence increasing the likelihood of upgrading technologies and the success of agricultural marketing.

Similarly, Ravi Kumar et al. (Citation2015) noted that communication networks are critical for interaction and knowledge sharing among sub-system members. Hence, they can improve the reliability of information and, as a result, enhance the likelihood of employing technologies such as mobile phones and the internet. This is supported by Maertens et al. (Citation2017) who supposed that a few experienced farmers who are part of networks could help farmers learn about new technologies.

Additionally, Okello et al. (Citation2012) provided evidence that ICT-based techniques of information provision (in this case, digital technology) result from the realization of communicating knowledge and information to rural farmers through the realization of communication. However, given their limited resource bases and inability to bargain for better prices effectively, improving networking among smallholder farmers is an essential component. Therefore, it can be hypothesised that

Hypotheses H2: Communication entrepreneurial networks significantly influence digital technology among smallholder farmers

1.4.3. Social entrepreneurial network and digital technologies

Technological advancements have drastically changed business organisations over the past two decades, enabling them to broaden the scope of their inventions (Y. Li et al., Citation2022). Since market competition is critical to achieving any organization’s goals (Mubeen et al., Citation2020; Rahmat et al., Citation2022), social networks can have a direct link with digital technology for market participation and competition. The idea is that social networks provide resources from outside the organization, which have been key entrepreneurial activities (Jiang et al., Citation2018) for technological advancement . Generally, the importance of social networks is built on the ideas of network theory and resource dependency theory. Basically, smallholder farmers cannot overcome challenges related to market participation if they stand alone. So, members can use collective bargaining to achieve their goals with the help of actions they take as a group after joining the networks.

Past studies have noted that social networks are key determinants of agricultural technology adoption (Maertens et al., Citation2017; Matuschke & Qaim, Citation2009; Murendo et al., Citation2018). This is supported by Maertens and Barrett (Citation2013) who stressed that social interactions in social networks positively affect technology adoption via “social learning,” as opposed to “nonsocial learning” interactions. Therefore, social networking platforms are widely regarded as the most reliable source of information on emerging technologies (Murendo et al., Citation2018).

Additionally, a study by Mukong and Nanziri (Citation2021) noted that the use of social networks by family and friends had a beneficial impact on improving the likelihood of adoption and use of mobile money technology in Uganda. This means that getting information from family and friends through networks makes it more likely that a person will use technology. Also as study by Bandiera and Rasul (Citation2006) linked adopting new agricultural technologies with social networks. The study found that social networks can help many people in developing countries get out of poverty because they offer benefits like technology.

Moreover, according to Young (Citation2009), social networks can help agricultural technology spread by allowing farmers to learn more about the technologies from one another rather than merely mimicking their colleagues’ methods. This is supported by Muange et al. (Citation2015) who communicated about how important social networks are for reducing the risks of using new technologies by sharing information about how to use them and what benefits they might have. Apart from that Feder and Umali (Citation1993) and Ramirez (Citation2013) revealed that social networks influence farmers’ technology decisions because they do not act independently; rather, they interact, discuss, and negotiate. These contacts involve a flow of knowledge, ideas, and information, all of which influence their decisions to adopt and use technology. Finally, social networks provide knowledge flows, which affect technology adoption more than other well-established drivers such as landholding size, age, and education (Filippini et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that;

Hypotheses H3: Social entrepreneurial networks significantly influence digital technology among smallholder farmers

1.4.4. Digital technology and market participation decisions among smallholder farmers

The literature has noted a direct relationship between technological advancement and market participation among smallholder farmers. For example, a study by Corallo et al. (Citation2018) has demonstrated how digital-enabled marketing may increase market efficiency and competitiveness among actors. Generally, digital technologies enable farmers to access new opportunities and experiences through digital capabilities and hence help them manage marketing processes (Smidt, Citation2021). Moreover, they give digital solutions to various agricultural difficulties, assisting farmers in achieving agricultural goals. Similarly, Krone and Dannenberg (Citation2018) enlightened that the adoption of digital technology had benefited farmers in enhancing their chances of reaching the market. This is possible because digital tools can make it easier for people to access commercial markets by making information more accessible.

In addition, digital interventions can provide information exchange and analytics that can help increase access to markets (El Bilali & Allahyari, Citation2018; Smidt, Citation2021). Besides this, the use of digital technology can aid in the expansion of businesses into new markets. This is possible because digital technology can assist in the development of creative products (Hrustek, Citation2020). In general, digital technologies can help to improve production efficiency and direct access to the market (FAO, Citation2020). Accordingly, the introduction of digital technology has significantly decreased the information search expenses experienced by farmers, thereby removing an important constraint in the context of inadequate infrastructure (Deichmann et al., Citation2016). To this end, it can be hypothesized that

Hypotheses H4: Digital technology significantly influence market participation among smallholder farmers

1.4.5. The mediating role of digital technology on entrepreneurial network and market participation

Technology addiction such as application of internet is a crucial technological component for development (Lebni et al., Citation2020). According to (Geng et al., Citation2022), adoption of technology is important for combating different challenges which can hinder development. In light of the discoveries made while developing hypotheses about the influence of entrepreneurial networks on digital technology and the relationship between digital technology and market participation, it can be concluded that digital technology may have a mediating effect on the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and market participation. This suggests that entrepreneurship networks offer farmers a foundation to participate in markets (Etriya et al., Citation2019) especially through embracing opportunities such as digital technology.

The technologies used must also give tools for alleviating the difficulties that have prevented smallholder farmers from participating in the market for a lengthy period. The consequence is that smallholder farmers seeking to improve their market involvement are more likely to join entrepreneurial networks that assist them in adopting digital technology as a bridge to greater market participation. Therefore, there might be an exchange relationship between entrepreneurial networks and digital technology, as well as an exchange relationship between digital technology and market participation, which leads to the notion that

Hypotheses H5: Digital technology significantly mediates the relationship between exchange network and market participation among smallholder farmers

Hypotheses H6: Digital technology significantly mediates the relationship between the communication network and market participation among smallholder farmers

Hypotheses H7: Digital technology significantly mediates the relationship between the social network and market participation among smallholder farmers

2. Methodology

2.1. Methods of data collection, sampling technique and sample size

This study was carried out in the Tanzanian region of Dodoma. Dodoma is one of the regions in which smallholder farmers experience low market participation due to various factors, including poor rural infrastructure, high transaction costs, and a lack of market information (Ismail et al., Citation2015). Therefore, pretesting and actual data collection from smallholder farmer households were accomplished using a structured questionnaire. Pretesting enabled the researcher to include the inquiries that were previously excluded as well as to reduce the number of poor proxy inquiries. Finally, the sampled smallholder farmers were interviewed to gather primary data about their operations in the study area. The researchers used a two-stage sampling procedure for this study. First, with the assistance of village officials, the potential smallholder farmer households in Makutupa, Hembahemba, and Njoge villages were identified purposefully from the village register book. The sampled households were then chosen randomly from the identified potential smallholder farmer households in the second stage. Thus, a total of 298 sampled households were selected at random from three villages: 93 (Makutupa), 101 (Hembahemba), and 104 (Njoge).

2.2. Data analysis

Using structural equation modelling (SEM), a statistical technique, it is feasible to assess models of causal links between two or more variables. Structural equations can be modelled to enable direct and indirect examination of relationships between independent and dependent variables. This property makes SEM superior to regression analysis in a variety of circumstances. SEM was used in this study to examine the impact of entrepreneurial networks on digital technology; the exchange network, the communication network, the social network, and the influence of digital technology on market participation. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was done to assess the validity of the items employed, and a path analysis was utilized to evaluate the links between variables. Additionally, a macro process test was conducted to investigate whether digital technology mediates entrepreneurial networking and market participation.

2.3. Measurement items

Several items from pre-existing scales that had previously been validated were used in this study. All of the measurement items adopted to measure the constructs are presented in Table . The exchange networks (ENW), which occur when entrepreneurs participate to benefit from business partnerships to promote transactions between participants, were measured using items. ((Enw1-Enw7) from (Kenny et al., Citation2011). Also, communication networks (CNW), which entrepreneurs join to benefit from the flow of business information and to connect with other entrepreneurs, were measured using items (Cnw1-Cnw5) from (Kenny et al., Citation2011), while social networks (SNW), which are based on formal and informal relationships such as family members, friends, and other relationships that provide support to entrepreneurs, were measured using items (Snw1-Snw8) from (Rodrigues Pinho & Soares, Citation2011). Also, items (Dte1-Det5) of digital technology (DTE) were adopted from (Abou-foul et al., Citation2021). Finally, items (Mpa1-MPa5) of market participation (MPA) were adopted from (Yaseen et al., Citation2018). Minor modifications were done through rewordings to ensure the measurement items fit the study context and setting. A 5-point Likert scale captured all items, with 5 strongly agreeing and 1 strongly disagreeing.

Table 1. Measurement items

2.4. Common method bias

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed on all latent items, and the results revealed that the un-rotated factor accounted for only 47.99% of the total variance. This suggests that there is no common bias problem. According to (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), to be free of common bias, none of the items should explain more than 50% of the variance.

3. Results

3.1. The characteristics of respondents

The information in Table pertains to smallholder farmers’ characteristics. The statistics suggest that most smallholder farmers surveyed are males (215, (68.1%). The most plausible reason is that males head most households in the study area. Furthermore, most smallholder farmers (88.54%) cultivate between 3 and 4 hectares of land, implying the possibility of having surplus crops for marketing. Additionally, the findings indicate that most respondents have between 5 and 15 years of farming experience, with 161 (54.02%) indicating sufficient production and marketing abilities to create surplus products. By contrast, most smallholder farmers possess primary and secondary credentials (certificate level), 187 (62.75%). This demonstrates that they possess fundamental knowledge that enables them to join entrepreneurial networks that facilitate the adoption of digital technologies for market participation. Additionally, most smallholder households contain more than 6 household members (146, 49.01%). This indicates the household’s availability of productive forces.

Table 2. The characteristics of smallholder farmers

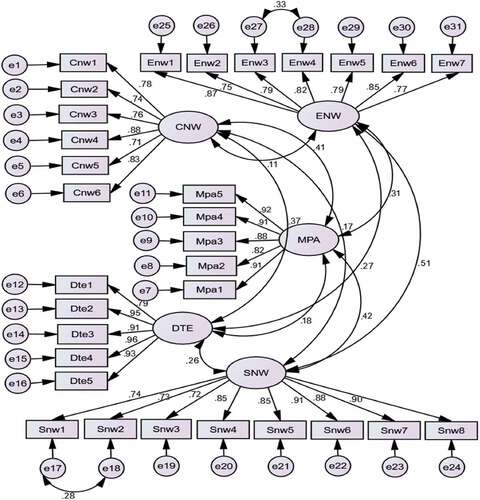

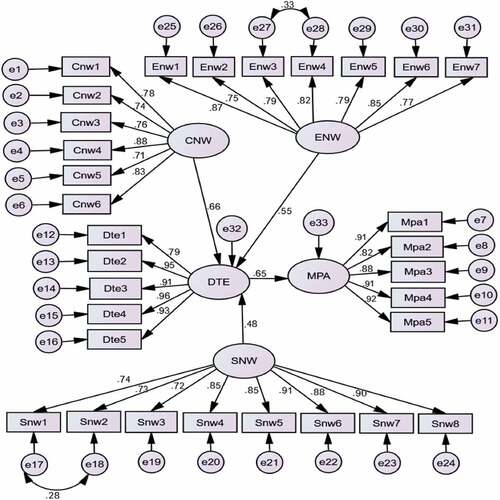

3.2. Assessment of measurement model

First, the factor loading values of measurement items in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were used to determine the convergent validity. This is done to determine whether the measurement items load onto the corresponding construct. The findings revealed that each item’s standardized loading value exceeded the recommended value of 0.6 (Figure ). According to Chin (Citation1998), loadings above 0.6 are regarded as satisfactory values. Secondly, the reliability of each construct was determined using the Cronbach’s α value. Each Cronbach’s α value was determined to have more than the threshold value of 0.7, indicating that they are within the acceptable ranges. Also, composite reliability (CR) was reached because all values were greater than 0.7, which was the highest possible value. A Cronbach’s alpha above 70% threshold was also recommended by (Azadi et al., Citation2021).

Further, it was discovered that the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct was larger than the suggested value of 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Likewise, the findings in Table indicate that discriminant validity was obtained because the square root values of AVE were greater than the inter construct correlation values. Also, the Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) was less than the values of the Average Variance (AVE; Table ). Additionally, findings on mean values are above 3.5, and standard deviations (SD) have small values, indicating that smallholder farmers agree that entrepreneurial networks and digital technology items are important for market participation decisions (Table ).

Table 3. Validity and reliability

Table 4. Discriminant validity

3.3. Goodness of fit for the fitted model

The results show that the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.951, the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.961, the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) = 0.942, and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.971. These values are much larger than the threshold value of 0.9 (Mulaik et al., Citation1989). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was found to be 0.046, smaller than the cutoff value of 0.05. Additionally, Chi-square (/df) was 1.298 less than the threshold. All these results indicate a good fit of the fitted model.

3.4. Hypothesis testing

This study involved both direct and indirect relationships. The direct relationships are presented in Table and Figure . The results revealed that exchange networks positively and significantly influence digital technology (β = 0.548, p < 0.001). This indicates that improving exchange entrepreneurial networks by 1% increases digital technology by 54.8%. Hence, hypothesis H1 was supported. Similarly, the results on the influence of entrepreneurial communication networks on digital technology were found to have a positive and significant relationship with digital technology (β = 0.661, p < 0.001). As a result, improving communication networks by 1% increases digital technology by 66.1%. Thus, hypothesis H2 was supported. Furthermore, the relationship between social entrepreneurial networks and digital technology was positive and significant (β = 0.478, p = 0.041). Consequently, hypothesis H3 was supported. This means if social entrepreneurial networks are improved by 1%, there is a possibility of increasing digital technology by 47.8%. Additionally, the study findings indicate a positive relationship between digital technology and market participation (β = 0.645, p < 0.001). The hypothesis H4 was supported. Hence, a 1% increase in digital technology increases market participation by 64.5%.

Table 5. Regression output

3.5. Process macro–mediation test

In this study, the process macro-mediation test was used to test the mediation effect of digital technology. The study involved three relationships; 1. exchange entrepreneurial networks → digital technology → market participation, 2. communication entrepreneurial networks → digital technology → market participation, and 3. social entrepreneurial networks → digital technology → market participation. Tables present digital technology process mediation results for exchange, communication, and social networking, respectively. The mediation effect of digital technology on the relationship between entrepreneurial exchange networks and market participation indicates that the bootstrap lower (BootLLCI) and upper (BootULCI) were 0.0766 and 0.2278, respectively. Therefore, digital technology was found to be a mediator in the relationship. Hence, hypothesis H5 was supported,

Table 6. Process mediation output for entrepreneurial exchange networks

Table 7. Process mediation output communication for entrepreneurial networks

Table 8. Process mediation output for social entrepreneurial networks

Similarly, the mediation effect of digital technology on the relationship between entrepreneurial communication networks and market participants indicates that the bootstrap lower (BootLLCI) and upper (BootULCI) were found to be 0.0962 and 0.2712, respectively. This also means that digital technology is a mediator in the relationship. Therefore, hypothesis H6 was supported. Finally, the results indicated that digital technology is a mediator of the relationship between social entrepreneurial networks and market participation because the bootstrap lower (BootLLCI) and upper (BootULCI) were 0.0811 and 0.2111, respectively. Thus, hypothesis H7 was supported.

4. Discussion

The study sought to elucidate how digital technology mediates smallholder farmers’ entrepreneurial networks and market participation. The structural model’s findings indicated a positive and statistically significant association between exchange, communication, and social networks in the context of digital technology. The findings revealed that exchange network links facilitate effective knowledge exchange among smallholder farmers, allowing farmers to gain access to digital technology for agricultural production, marketing, and farm management. WhatsApp, histograms, and Twitter all rely heavily on knowledge. Participation in networks facilitates knowledge exchange, ultimately strengthening smallholder farmers’ technology.

Apart from exchange networks, it was discovered that communication networks directly affect digital technology uptake and utilization. The most plausible explanation is that most smallholder farmers lack knowledge of emerging digital technologies. Therefore, by connecting to communication networks, smallholder farmers can gain access to information that will assist them in adopting digital technology to increase market participation. As a result, disseminating relevant and timely information increases the likelihood of new technologies being embraced by individuals, especially those who have previously adopted and seen the benefits of digital technology. Furthermore, the research demonstrates that information quality is critical in enhancing management practices among smallholder farmers from a managerial standpoint. So, the farmer must do everything he or she can to make sure that useful information about farming and selling is easy to find and easy to use

This is in line with Diemer et al. (Citation2020), who insisted that farmers acquire fresh knowledge before making strategic farming decisions. Also Phiri et al. (Citation2019) posted that farmers must establish communication networks to collect data that will aid them in getting digital marketing opportunities. Additionally, social entrepreneurship networks are linked to digital technologies because, by socially connecting with other network members, smallholder farmers can boost their chances of becoming familiar with new technologies such as internet-based farming and agricultural marketing. Bandiera and Rasul (Citation2006) argued that adopting new agricultural technologies, which is crucial for many developing nations, can be connected to social networks. Also Muange et al. (Citation2015) stressed the critical role of social networks in lowering the risks associated with new technology adoption by sharing information about how to use the technology and its anticipated benefits. Apart from that Feder and Umali (Citation1993) and Ramirez (Citation2013) pointed that social networks influence farmers’ technology decisions because farmers do not operate individually; rather, they connect, talk, and negotiate. These encounters result in the transfer of knowledge, ideas, and information, all of which influence their decision to adopt and use technology.

It was also discovered that smallholder farmers would benefit from digital technologies since they would be better positioned to engage in markets. The most likely reason is that smallholder farmers who have access to smart phones, computers, and other digital tools can use WhatsApp, Twitter, histograms, and Facebook to connect with people who want to buy their crops. This makes it more likely for them to sell their goods at markets This is supported by El Bilali and Allahyari (Citation2018) and Smidt (Citation2021), who stated that digital technology could have a positive economic impact by lowering costs, lowering transaction costs, and connecting smallholder farmers to market opportunities. These digital initiatives can facilitate information interchange and analytics, thereby increasing market access. The findings are also in line with Hrustek (Citation2020), who observed that the use of digital technology could assist firms in expanding into new markets, meeting clients’ needs in areas where specialized agricultural goods are in short supply, and assist in the development of innovative products.

Furthermore, digital technologies are particularly advantageous in remote rural areas, where public infrastructure is inadequate to assist rural farmers’ access to local and global markets. Generally, several past studies have related digital technologies such as social media as a key determinant of several areas of development, such as education, tourism, and agriculture. Studies have shown that technologies can help entrepreneurs in these sectors achieve competitive advantages such as market access, even in dealing with pandemic challenges such as COVID-19 (Azizi et al., Citation2021; Rahmat et al., Citation2022; Zhou et al., Citation2022). Similarly, Su et al. (Citation2022), suggested that technology-based interventions are important to play a role in resolving issues that arose during COVID-19.

In general, technological innovations have proven to be essential components in the process of resolving various problems, particularly in the form of connecting customers and producers through the use of online shopping. In this manner, farmers have the opportunity to develop a potential link with their customers, especially through the consumption of established networks that can provide a startup based for their customers.

Finally, the finding that digital technology mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and market participation suggests that market participation can be high among smallholder farmers if networks increase the possibility of adopting digital technologies, which in turn increases the likelihood of adopting various technologies sufficient to increase market participation. This means that smallholder farmers can find customers and grow their customer bases before putting their goods on the market by using digital technology in the right way, such as through entrepreneurial networks.

5. Conclusion

The proposed study problem reflects empirical findings on the mediating effects of digital technology on entrepreneurial networks and market participation. The analysis incorporated survey data from 298 smallholder household heads. The findings indicate that smallholder farmers access digital technology via entrepreneurial networks. To begin with, entrepreneurial networks appeared to have a positive and significant relationship with digital technology. This suggested that, they directly impact the use of digital technologies by smallholder farmers. Furthermore, digital technology was found to have a positive and significant relationship with smallholder farmers’ market participation. Finally, digital technology was found to be a significant mediator of the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and smallholder farmers’ market participation. The condition that digital technology acts as a mediator in the relationship implies that, if enhanced, digital technology can provide the optimal mechanism for expanding market participation. This indicates that entrepreneurial networks cannot significantly impact market participation on their own. Rather than that, they improve market participation through advancements in digital technology. Small-scale farmers need to make sure that important information is easy to find and useful for their daily work

6.1. Practical implication

This study examines the mediating effect of digital technologies on entrepreneurial networks and market participation. In general, the study’s findings imply that digital technologies should not be viewed as difficult to embrace; these technologies may be used even through a cell phone, thereby increasing market visibility and minimizing high transaction costs associated with rural areas’ lack of infrastructure. Smallholder farmers should also recognize that some behaviors are self-created; hence, choosing which network to join should also be a self-initiative. Finally, the findings indicate that the values associated with exchange, communication, and social networks should motivate smallholder farmers to seek out the most effective ways to develop networks that closely match their needs, with the primary goal of increasing their chances of adopting digital technologies and increasing their market participation opportunities.

6.2. Theoretical implication

The study uses networking and resource dependency theories. To begin with, this study established that both theories could coexist more effectively in the context of smallholder farmers. Since all theories emphasize collaboration to increase bargaining power among resource-limited smallholder farmers, they can serve as a foundation for understanding how resource-poor groups can pool their limited resources and compete with resource-rich groups such as large farmers through networking. Additionally, the study contributes to the theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial networks and digital technologies, which are novel concepts in agriculture, particularly for smallholder farmers, by examining digital technology as a mediator of the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and market participation. By combining these two theories, smallholder farmers now have a new theoretical framework for considering how they might network and combine resources to avoid resource dependency. Moreover, the study theorizes that smallholder farmers with entrepreneurial minds might bolster their intentions to adopt digital technology by joining or creating entrepreneurial networks, thus reaping networks’ benefits.

6.3. Policy recommendations

For an extended period of time, the food security and welfare of the majority of households in developing countries have been put in jeopardy by the challenges that smallholder farmers face when trying to participate in markets. As a result, this study provides policymakers with information that they can use to take strategic initiatives that will raise the application of digital technologies and entrepreneurial networks for the purpose of increasing market participation. In general, there is a need for specific policies that address concerns regarding technologies adoption and collective bargaining when it comes to agricultural developments. In addition to this, these policies need to be designed to make it easier for smallholder farmers to receive training that will improve their knowledge and abilities to identify and design proper networks that can help them access important resources such as technologies.

6.4. Limitations and directions for the future studies

Finally, this study has certain limitations. To begin with, this study’s area of study and sample size are limited. Although most smallholder farmers in developing nations share similar features, expanding the study areas increases generality. Second, the sample size is limited to just 298 smallholder farmers. Even though SEM needs sample sizes of more than 100, increasing the size of the sample by adding other groups, like buyers, may make it easier to generalize.

Additionally, it is recommended that future studies apply the model to compare large-scale and smallholder farmers in different sectors and nations. Apart from that, while this study employed a cross-sectional methodology, future research can employ a longitudinal design to ascertain the evolution of entrepreneurial networks and digital technologies for market participation. Also, because this study only uses a quantitative method, future research can use a mix of methods to get a full picture of the things that were looked at in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon a reasonable request

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ismail J. Ismail

Ismail J. Ismail is a senior lecturer and a researcher at the department of business administration and management, University of Dodoma, Tanzania. His areas of research include marketing management and entrepreneurship, small and medium enterprise development, agribusiness development and strategic management. He can be reached at [email protected] or [email protected]

References

- Abbas, J., Mahmood, S., Ali, H., Raza, M. A., Ali, G., Aman, J., Bano, S., & Nurunnabi, M. (2019). The effects of corporate social responsibility practices and environmental factors through a moderating role of social media marketing on sustainable performance of business firms. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(12), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU11123434

- Abbas, J., Raza, S., Nurunnabi, M., Minai, M. S., & Bano, S. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurial business networks on firms’ performance through a mediating role of dynamic capabilities. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(11), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113006

- Abbas, J., Zhang, Q., Hussain, I., Akram, S., Afaq, A., & Shad, M. A. (2020). Sustainable innovation in small medium enterprises: The impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation through a mediation analysis by using SEM approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062407

- Abou-foul, M., Ruiz-Alba, J. L., & Soares, A. (2021). The impact of digitalization and servitization on the financial performance of a firm: An empirical analysis. Production Planning and Control, 32(12), 975–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1780508

- Al Halbusi, H., Al-Sulaiti, K., Abbas, J., & Al-Sulaiti, I. (2022). Assessing factors influencing technology adoption for online purchasing amid COVID-19 in Qatar: Moderating role of word of mouth. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10(1039). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.942527

- Aman, J., Abbas, J., Mahmood, S., Nurunnabi, M., & Bano, S. (2019). The influence of Islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development in Pakistan: A structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(11), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113039

- Andaregie, A., Astatkie, T., Teshome, F., & Yildiz, F. (2021). Determinants of market participation decision by smallholder haricot bean (Phaseolus vulgaris l.) farmers in Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1879715

- Asad, A., Abbas, J., Irfan, M., & Raza, H. M. A. (2017). The impact of HPWS in organizational performance: A mediating role of servant leadership. Journal of Managerial Sciences, 11(3), 25–48.

- Azadi, N. A., Ziapour, A., Lebni, J. Y., Irandoost, S. F., Abbas, J., & Chaboksavar, F. (2021). The effect of education based on health belief model on promoting preventive behaviors of hypertensive disease in staff of the Iran university of medical sciences. Archives of Public Health, 79(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00594-4

- Azizi, M. R., Atlasi, R., Ziapour, A., Abbas, J., & Naemi, R. (2021). Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon, 7(6), e07233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07233

- Balkrishna, B. B., & Deshmukh, A. A. (2017). A study on role of social media in agriculture marketing and its scope. Global Journal of Management and Business Research: E Marketing, 17(1), 33–36.

- Bandiera, O., & Rasul, I. (2006). Social networks and technology adoption in Northern Mozambique. The Economic Journal, 116(512), 869–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01115.x

- Brahmbhatt, D. H., Ross, H. J., & Moayedi, Y. (2021). Digital technology application for improved responses to health care challenges: Lessons learned from COVID-19. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 32(2), 279–291.

- Bratkovic, T., Antoncic, B., & Ruzzier, M. (2009). The personal network of the owner-manager of a small family firm: The crucial role of the spouse. Managing Global Transitions, 7(2), 171–190.

- Changalima, I. A., & Ismail, I. J. (2022). Agriculture supply chain challenges and smallholder maize farmers’ market participation decisions in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 21(1), 104–120.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 22(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/249674

- Corallo, A., Latino, M. E., & Menegoli, M. (2018). From industry 4.0 to agriculture 4.0: A framework to manage product data in agri-food supply chain for voluntary traceability, A framework proposed. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Engineering, 12(5), 126–130.

- Deichmann, U., Goyal, A., & Mishra, D. (2016). Will digital technologies transform agriculture in developing countries? Agricultural Economics (United Kingdom), 4(S1), 21–33. 47 (S1)

- Diemer, N., Staudacher, P., Atuhaire, A., Fuhrimann, S., & Inauen, J. (2020). Smallholder farmers’ information behavior differs for organic versus conventional pest management strategies: A qualitative study in Uganda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 257, 120465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120465

- El Bilali, H., & Allahyari, M. S. (2018). Transition towards sustainability in agriculture and food systems: Role of information and communication technologies. Information Processing in Agriculture, 5(4), 456–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2018.06.006

- Etriya, E., Scholten, V. E., Wubben, E. F. M., & Omta, S. W. F., & Onno. (2019). The impact of networks on the innovative and financial performance of more entrepreneurial versus less entrepreneurial farmers in West Java, Indonesia. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 89 (1), 100308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2019.100308

- Fafchamps, M., & Hill, R. V. (2005). Selling at the farmgate or traveling to market. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 87(3), 717–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8276.2005.00758.x

- FAO. (2020). Digital technology and agricultural markets. Background paper for The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets (SOCO) 2020. https://www.fao.org/policy-support/tools-and-publications/resources-details/en/c/1315007/

- Feder, G., & Umali, D. L. (1993). The adoption of agricultural innovations. A review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 43(3–4), 215–239.

- Felzensztein, C., Gimmon, E., & Carter, S. (2010). Geographical co-location, social networks and inter-firm marketing co-operation: The case of the salmon industry. Long Range Planning, 43(5–6), 675–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.006

- Filippini, R., Marescotti, M. E., Demartini, E., & Gaviglio, A. (2020). Social networks as drivers for technology adoption: A study from a rural mountain area in Italy. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(22), 9392. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229392

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fu, Q., Abbas, J., & Sultan, S. (2021). Reset the industry redux through corporate social responsibility: The COVID-19 tourism impact on hospitality firms through business model innovation. Frontiers in Psychology, (6686).

- Ge, T., Abbas, J., Ullah, R., Abbas, A., Sadiq, I., & Zhang, R. (2022). Women’s entrepreneurial contribution to family income: Innovative technologies promote females’ entrepreneurship amid COVID-19 crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(13). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828040

- Geng, J., Haq, S. U., Abbas, J., Ye, H., Shahbaz, P., Abbas, A., & Cai, Y. (2022). Survival in pandemic times: Managing energy efficiency, food diversity, and sustainable practices of nutrient intake amid COVID-19 crisis. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.945774

- Gollin, D. (2014). Smallholder agriculture in Africa. In IIED Working Paper. IIED, London.

- Hagos, A., & Zemedu, L. (2015). Determinants of improved rice varieties adoption in fogera district of Ethiopia. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 4(1), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.4314/star.v4i1.35

- Hampton, A., Cooper, S., & Mcgowan, P. (2009). Female entrepreneurial networks and networking activity in technology-based ventures: An exploratory study. International Small Business Journal, 27(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608100490

- Hrustek, L. (2020). Sustainability driven by agriculture through digital transformation. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(20), 8596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208596

- Hussain, T., Abbas, J., Li, B., Aman, J., & Ali, S. (2017). Natural resource management for the world’s highest park: Community attitudes on sustainability for central Karakoram national park, Pakistan. Sustainability, 9(6), 972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060972

- Ismail, I. J. (2014). Influence of market facilities on market participation of maize smallholder farmer in farmer organization’s market services in Tanzania: Evidence from Kibaigwa international grain market. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Health Sciences, 3(3), 181–189.

- Ismail, I. J. (2020). Making markets work for smallholder maize farmers through strengthening rural market practices in Tanzania. Journal of Co-Operative and Business Studies (JCBS), 5(2), 54–62.

- Ismail, I. J. (2021). From a loser to a winner: How can collective marketing increase market access among smallholder farmers in Tanzania? Tanzania Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 20(2), 202–216.

- Ismail, I. J. (2022a). Market participation among smallholder farmers in Tanzania: Determining the dimensionality and influence of psychological contracts. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2021-0183

- Ismail, I. J. (2022b). Why did I join networks? The moderating effect of risk-taking propensity on network linkage and the performance of women-owned businesses. Vilakshan-XIMB Journal of Management, ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/XJM-05-2022-0113

- Ismail, I. J., & Changalima, I. A. (2019). Postharvest losses in maize: Determinants and effects on profitability of processing agribusiness enterprises in Tanzania. East African Journal of Social and Applied Sciences (EAJ-SAS), 1, 2.

- Ismail, I. J., Srinivas, M., & Tundui, H. (2015). Transaction costs and market participation decisions of maize smallholder farmers in dodoma region, Tanzania. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Health Sciences, 4(2), 12–20.

- Jiakui, C., Abbas, J., Najam, H., Liu, J., & Abbas, J. (2023). Green technological innovation, green finance, and financial development and their role in green total factor productivity: Empirical insights from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 382, 135131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135131

- Jiang, X., Liu, H., Fey, C., & Jiang, F. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, network resource acquisition, and firm performance: A network approach. Journal of Business Research, 87, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.02.021

- Jones, R., Alford, P., & Wolfenden, S. (2014). Entrepreneurial Marketing in the Digital Age: A study of the SME tourism industry. Cell, 1–14.

- Jones, R., Suoranta, M., & Rowley, J. (2013). Strategic network marketing in technology SMEs. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(5/6), 671–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.797920

- Kahan, D. (2012). Farm management extension guide: 5 Entrepreneurship in farming. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). https://www.fao.org/3/i3231e/i3231e.pdf

- Kenny, B., Fahy, J., & Fletcher, M. (2011). Network resources and international performance of high tech SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18(3), 529–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001111155691

- Khou, A., & Suresh, K. R. (2018). A study on the role of social media mobile applications and its impact on agricultural marketing in Puducherry region. Journal of Management (JOM), 5(6), 28–35.

- Kiprop, E., Okinda, C., Wamuyu, S., & Geng, X. (2019). Factors influencing smallholder farmers participation in collective marketing and the extent of participation in improved indigenous chicken markets in Baringo, Kenya. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 37(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajaees/2019/v37i430283

- Kisaka-Lwayo, M., & Obi, A. (2012). Risk perceptions and management strategies by smallholder farmers in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Management, 1, 28–39. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.149748

- Krone, M., & Dannenberg, P. (2018). Analysing the effects of information and communication technologies (ICTs) on the integration of East African farmers in a value chain context. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 62(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2017-0029

- Lebni, J. Y., Toghroli, R., Abbas, J., NeJhaddadgar, N., Salahshoor, M. R., Mansourian, M., Gilan, H. D., Kianipour, N., Chaboksavar, F., & Azizi, S. A. (2020). A study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health: A study based on Iranian University Students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9.

- Li, X., Abbas, J., Dongling, W., Baig, N. U. A., & Zhang, R. (2022). From cultural tourism to social entrepreneurship: Role of social value creation for environmental sustainability. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925768

- Li, Y., Al-Sulaiti, K., Dongling, W., Abbas, J., & Al-Sulaiti, I. (2022). Tax avoidance culture and employees’ behavior affect sustainable business performance: The moderating role of corporate social responsibility. In Frontiers in Environmental Science (pp. 1081).

- Liu, Q., Qu, X., Wang, D., Abbas, J., & Mubeen, R. (2022). Product market competition and firm performance: Business survival through innovation and entrepreneurial orientation amid COVID-19 financial crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, (5487).

- Maertens, A., & Barrett, C. B. (2013). Measuring social networks’ effects on agricultural technology adoption. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 95(2), 353–359.

- Maertens, A., Deichmann, U., Goyal, A., & Mishra, D. (2017). Who cares what others think (or do)? Social learning and social pressures in cotton farming in India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 99(4), 988–1007. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaw098

- Matuschke, I., & Qaim, M. (2009). The impact of social networks on hybrid seed adoption in India. Agricultural Economics, 40(5), 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00393.x

- Megerssa, G. R., Negash, R., Bekele, A. E., Diriba, & Nemera, B. (2020). Smallholder market participation and its associated factors: Evidence from Ethiopian vegetable producers. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1783173

- Mhagama, J. K., Mmasa, J. J., & Ismail, I. J. (2021). Marketing services for choice of market channels among sesame smallholder farmers in Tanzania: The moderating effect of agricultural marketing co-operative societies. East African Journal Of Social And Applied Sciences (Eaj-Sas), 3, 1.

- Muange, E. N., Gödecke, T., & Schwarze, S. (2015). Effects of social networks on technical efficiency in smallholder agriculture: The case of cereal producers Tanzania [Georg-August-University Göttingen]. In International Conference of Agricultural Economists, Milan Italy. http://197.136.134.32/handle/123456780/4696

- Mubeen, R., Han, D., Abbas, J., & Hussain, I. (2020). The effects of market competition, capital structure, and CEO duality on firm performance: A mediation analysis by incorporating the GMM model technique. Sustainability, 12(8), 3480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083480

- Mukong, A. K., & Nanziri, L. E. (2021). Social networks and technology adoption: Evidence from mobile money in Uganda. Cogent Economics and Finance, 9(1), 1913857. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1913857

- Mulaik, S. A., James, L. R., Van Alstine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.430

- Murendo, C., Wollni, M., De Brauw, A., & Mugabi, N. (2018). Social network effects on mobile money adoption in Uganda. Journal of Development Studies, 54(2), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1296569

- Negi, D. S., Birthal, P. S., Roy, D., & Khan, M. T. (2018). Farmers’ choice of market channels and producer prices in India: Role of transportation and communication networks. Food Policy, 81, 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.10.008

- O’Dwyer, M., Gilmorespi, A., & Carson, D. (2009). Innovative marketing in SMEs: An empirical study. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 17(5), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652540903216221

- Okello, J. J., Kirui, O., Njiraini, G. W., & Gitonga, Z. (2012). Drivers of use of information and communication technologies by farm households: The Case of smallholder farmers in Kenya. Journal of Agricultural Science, 4(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v4n2p111

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. In Harper and Row. Harper and Row: New York. https://doi.org/10.2307/257794

- Phiri, A., Chipeta, G. T., & Chawinga, W. D. (2019). Information needs and barriers of rural smallholder farmers in developing countries: A case study of rural smallholder farmers in Malawi. Information Development, 35(1), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666918755222

- Pittaway, L., Robertson, M., Munir, K., Denyer, D., & Neely, A. (2004). Networking and innovation: A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5/6(3&4), 137–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-8545.2004.00101.x

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Prasetiyo, S., Cahyono, E., & Safitri, R. (2021). An analysis of millennial farmers’ communication networks on hydroponic vegetable marketing topics via whatsapp application (hydroponic farmers in situbondo). HABITAT, 32(2), 01–112. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.habitat.2021.032.2.12

- Rahmat, T., Raza, S., Zahid, H., Abbas, J., Mohd Sobri, F., & Sidiki, S. (2022). Nexus between integrating technology readiness 2.0 index and students’ e-library services adoption amid the COVID-19 challenges: Implications based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_508_21

- Raj, K. G. C., & Hall, R. P. (2020). The commercialization of smallholder farming— A case study from the rural western middle hills of Nepal. Agriculture (Switzerland), 10(5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10050143

- Ramirez, A. (2013). The influence of social networks on agricultural technology adoption. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 79, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.05.059

- Ravi Kumar, K., Nain, M. S., Singh, R., Chahal, V. P., & Bana, R. S. (2015). Analysis of farmers’ communication network and factors of knowledge regarding agro meteorological parameters. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 85(12), 1592–1596.

- Richards, S. T., & Bulkley, S. (2011). Agricultural Entrepreneurs: The First and the Forgotten? SSRN Electronic Journal, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1020697

- Rodrigues Pinho, J. C. M., & Soares, A. M. (2011). Examining the technology acceptance model in the adoption of social networks. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 5(2/3), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/17505931111187767

- Smidt, H. J. (2021). Factors affecting digital technology adoption by small-scale farmers in agriculture value chains (AVCs) in South Africa. Information Technology for Development, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2021.1975256

- Su, Z., Cheshmehzangi, A., Bentley, B. L., McDonnell, D., Šegalo, S., Ahmad, J., Chen, H., Terjesen, L. A., Lopez, E., Wagers, S., Shi, F., Abbas, J., Wang, C., Cai, Y., Xiang, Y.-T., & da Veiga, C. P. (2022). Technology-based interventions for health challenges older women face amid COVID-19: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02150-9

- Torok, A., Toth, J., & Balogh, J. M. (2018). Networking theory of innovation in practice – The Hungarian case. Agricultural Economics (Czech Republic), 64(12), 536–545. https://doi.org/10.17221/60/2018-AGRICECON

- Vasilchenko, E., & Morrish, S. (2011). The role of entrepreneurial networks in the exploration and exploitation of internationalization opportunities by information and communication technology firms. Journal of International Marketing, 4(4), 88–105.

- Wahyuni, S., Sumardjo, L. D., & Sadono, D. (2016). Communication networks of organic rice farmers in Tasikmalaya. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research, 28(2), 54–63.

- Wale, Z. E., Unity, C., & Nolwazi, H. (2021). Towards identifying enablers and inhibitors to on-farm entrepreneurship: Evidence from smallholders in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Heliyon, 7(1), e05660.

- Windsperger, J., Hendrikse, G. W. J., Cliquet, G., & Ehrmann, T. (2018). Governance and strategy of entrepreneurial networks: An introduction. Small Business Economics, 50(4), 671–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9888-0

- Wolfenden, S. F. (2020 ()). Entrepreneurial marketing orientation: the influence on the adoption and use of digital marketing technology in small tourism businesses [Bournemouth]. Bournemouth University. http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/35199/1/WOLFENDEN%2C

- Yaseen, A., Bryceson, K., & Mungai, A. N. (2018). Commercialization behaviour in production agriculture: The overlooked role of market orientation. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 8(3), 579–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2017-0072

- Young, H. P. (2009). Innovation diffusion in heterogeneous populations: Contagion, social influence, and social learning. American Economic Review, 99(5), 1899–1924. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.5.1899

- Yu, S., Abbas, J., Draghici, A., Negulescu, O. H., & Ain, N. U. (2022). Social media application as a new paradigm for business communication: The role of COVID-19 knowledge, social distancing, and preventive attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 903082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903082

- Zafar, M. Z., Shi, X., Yang, H., Abbas, J., & Chen, J. (2022). The impact of interpretive packaged food labels on consumer purchase intention: The comparative analysis of efficacy and inefficiency of food labels. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15098. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215098

- Zhang, X., Husnain, M., Yang, H., Ullah, S., Abbas, J., & Zhang, R. (2022). Corporate business strategy and tax avoidance culture: Moderating role of gender diversity in emerging economy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 827553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.827553

- Zhou, Y., Draghici, A., Abbas, J., Mubeen, R., Boatca, M. E., & Salam, M. A. (2022). Social media efficacy in crisis management: effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions to manage COVID-19 challenges. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626134

- Zhuang, D., Abbas, J., Al‐Sulaiti, K., Fahlevi, M., Aljuaid, M., & Saniuk, S. (2022). Land‐use and food security in energy transition: Role of food supply. frontiers in Sustainable Food systems, 6, 510. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1053031