?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

GLOBAL Good Agricultural Practices (GLOBAL G.A.P.) standards have appeared to increasingly control the exchange of horticultural products in the international market. To make horticulture exports viable and lucrative, smallholder farmers need to invest in GLOBAL G.A.P. While research has focused on the impact of adoption on the welfare of farmers, the factors stimulating the adoption of these standards have been ignored. This study examines the determinants of the adoption of GGAPs (GLOBAL G.A.P.) among smallholder French bean producers in Murang’a South Sub-County. The study used cross-sectional data from a random sample of 215 farmers. The adoption index was used to determine adoption levels per household while a “gologit model” was applied to assess factors influencing the adoption of GGAPs among farmers. The adoption index results indicate that farmers on the contract had higher adoption levels (66%) relative to non-contracted farmers (34%). Based on the gologit findings, the determinants of farmer’s compliance levels were age (P < 0.01), gender (P < 0.1), education (P < 0.01), household size (P < 0.01), training (P < 0.01), extension service (P < 0.05), group membership (P < 0.05), farming experience (P < 0.05), vertical coordination options (VCO) (P < 0.1) and market availability(P < 0.01) and reliability (P < 0.05). Therefore, this study recommends an incentive that will promote the improvement of agricultural extension to facilitate contract farming for the adoption of GGAPs. Additionally, the government should put in place measures to safeguard farmers from market exploitation.

Public interest statement

GLOBAL G.A.P. standards have appeared to increasingly control the exchange of horticultural products in the international market. With the growing demand for safe and quality agricultural products in the global market, the Kenyan government has made substantial efforts to promote vertical coordination options in linking farmers to the global markets. The call for traceability and safety of horticultural food products has necessitated farmers to adopt good farming practices to remain competitive on the global market. Despite the measures taken by farmers in complying with GLOBAL G.A.P., knowledge of the role of vertical coordination options and other factors in stimulating the adoption of these standards is useful to the private sector, county and national government for policy formulation. The empirical findings from this study emphasize the importance of contract farming, training and farmer group organizations in facilitating the adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P.

1. Introduction

Globally, horticulture is the fastest-growing agricultural sector. It contributes to nutrition security, poverty alleviation, employment creation and improved income along the value chain (Krause, Citation2020). China has been ranked as the world’s largest exporter of horticultural products (FAO, Citation2019). In Kenya, Horticultural export production has been accredited for employment and rural community development (Gichuki et al., Citation2020). The sector remains among the four foreign exchange-earners accounting for 19 % of Kenya’s total exports in 2019. This consisted of floriculture at 11% while fruits and vegetables at 4% each. The key destinations for Kenya’s horticultural exports include the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, the United States of America and Germany (Kenya Export Promotion and Branding, Citation2020). With the outbreak of the Covid 19 crisis, Kenya experienced an increment in the export of horticultural products in the first quarter of 2020 surpassing levels of the previous years (Mold & Mveyange, Citation2020).

The call for fresh horticultural products is increasing steadily, in the local and global markets. Consumers in developed nations, such as the European Union desire fruits, vegetables and flowers available all year. Customers in these countries are willing to pay a premium for high-quality horticultural produce. As a result of these tendencies, interest in accessing international markets among traders and producers of horticultural products in developing countries has increased significantly (Krause et al., Citation2016). Besides, vegetable production for export has significantly increased in Sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, Kenya has been ranked second in French beans production after DRC reporting 3.2 tons per acre compared to global production of 5.7 tons per acre (Mwangi et al., Citation2019).

However, the rise in consumer demand for better food quality and safety as well as the difficulty of food safety threats, have increased the burden on compliance with agricultural practices at the farm level. Policies that highlight quality and safety standards along the chain have been developed to improve the productivity and marketability of horticultural produce. The GLOBAL G.A.P. standard has been recognized as the main reference for good agricultural practices in the global market. It covers a wide range of concerns, including food quality, safety, traceability requirements, pesticide use risks, and the environmental sustainability of agriculture. Further, it has social effects as it takes care of workers’ safety, health and welfare (Pandit et al., Citation2017). Therefore, smallholders’ ability to strengthen and remain competitive in the global export market will depend on their capacity to fully comply with these standards.

Nevertheless, the uptake level of GLOBAL G.A.P. standards at the farm level and post-harvest handling remain a global constraint for producers. This has been attributed to inadequate awareness, high investment costs and a lack of market opportunities (Krause, Citation2020). Also, the insufficient capacities and specialized knowledge among public extension service providers to prepare farmers for advancement and compliance with GLOBAL G.A.P. standards have resulted in a transfer in the standard-setting authority from the public to the private sector. Therefore, smallholder farmers rely on buyers or NGOs or International organizations to provide support services to adapt to international standards. In such a scenario, smallholder farmers find themselves on a truncated plane in adopting GGAPs or the adoption could be said to be non-linear meaning that they are not always on the same level of adoption. As a response, vertical coordination strategic options have emerged to provide producers with the necessary support structure to fill this gap (Gichuki et al., Citation2020).

Several studies have examined the potential impacts of vertical coordination options on the adoption of food safety measures at the farm level (Ba et al., Citation2019; Islam et al., Citation2019; Hou et al., Citation2020; Kumar et al., Citation2018, Citation2016; Trifkovic, Citation2014; Wollni et al. (Citation2012). They found that contract farming appeared to have a positive effect on the adoption of food safety standards compared to non-contract options. Other empirical studies have focused on factors influencing the adoption of food safety measures (Ali, Citation2012; Kumar et al., Citation2018; Laosutsan et al., Citation2019; Paraffin et al., Citation2018; Pongvinyoo et al., Citation2014; Terano et al., Citation2015; Tu et al., Citation2018). In these studies, young age was found to be positive and significant in the adoption of good agricultural practices and technology (Moturi et al., Citation2015; Saadun et al., Citation2018; Terano et al., Citation2015). However, (Corallo et al., Citation2020; Krause et al., Citation2016)* found that age had a negative effect on adoption of GGAPs. Also, sustainable agricultural practices were more likely to be employed by educated producers (Anaglo et al., Citation2014; Gao et al., Citation2017; Krause et al., Citation2016; Ma & Abdulai, Citation2019). Moreover, studies have found off-farm income to be correlated with the adoption of improved agricultural techniques. Off-farm income solves credit constraints or acts as a substitute for borrowed credit (Aguilar-Gallegos et al., Citation2015; Cafer & Rikoon, Citation2018; Diiro, Citation2013; Hailu et al., Citation2014; Mariano et al., Citation2012). Inadequate capital has also been found to influence the implementation of farm infrastructure (Annor, Citation2018; Jelsma et al., Citation2019; Panahzadeh Parikhani et al., Citation2015; Tesfaye et al., Citation2021).

Other studies have shown a strong positive correlation between the amount of cultivated land and the adoption of agricultural technologies (Aguilar-Gallegos et al., Citation2015; Anaglo et al., Citation2014; Ngwira et al., Citation2014; Rodthong et al., Citation2020) which contradicts the results found by Ntshangase et al. (Citation2018) and Ali (Citation2012). Additionally, Social capital such as farmer group has been found to play a vital role in helping farmers to adopt good agricultural practices (Connor et al., Citation2020; Kassie et al., Citation2015; Kumar et al., Citation2020; Ngwira et al., Citation2014; Tu et al., Citation2018). Similarly, farming experience has also been found to enhance the adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P. (Paraffin et al., Citation2018; Suwanmaneepong et al., Citation2016) contrary to results by (Kumar et al., Citation2020; Huang & Karimanzira, Citation2018)*. The theory and practical skills provided by extension officers have proven to facilitate the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices (Cafer & Rikoon, Citation2018; Huang & Karimanzira, Citation2018; Kabir & Rainis, Citation2015; Kassie et al., Citation2015; Pongvinyoo et al., Citation2014; Tu et al., Citation2018) as opposed to results by Khin (Citation2016). Therefore, this study investigates the influence of demographic, social-economic and institutional factors on the adoption of Global Good Agricultural Practices at the farm level.

Although studies have provided evidence on the factors that influence the adoption of GGAPs globally, limited research work has been done in Kenya. It is thus crucial to understand the potential determinants of the adoption of good agricultural practices among smallholder farmers.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area

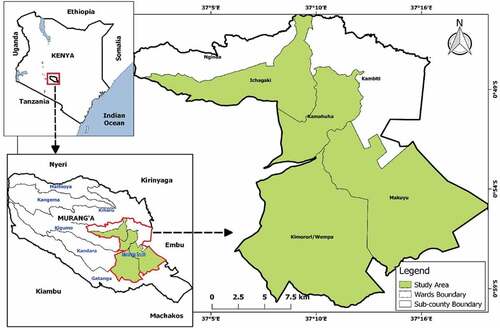

The study was conducted in Murang’a South Sub-County. The total area of Murang’a South Sub-County is 456.9 sq. Kilometers with a population of 184,824 people (KNBS, 2019). The Sub-County is located between Longitude 37 ° 08’ 60” East and Latitude 0 ° 43’ 0” North (See Figure ). Murang’a South Sub-County comprises 6 wards, namely Kimorori, Makuyu, Kamahuha, Ichagaki, Nginda and Kambiti. The area receives an annual average rainfall of 1164 mm and an annual temperature of 19.8 °C. It experiences long rains in March, April and May, with short rains being recorded between October-November. Agriculture is the main economic activity in the region, and it contributes to about 57% of the county’s population income. The major cash crops in the county include tea, coffee, avocados, mangoes and macadamia. Horticultural crops include French beans, tomatoes, cabbages, kales and spinach, while food crops include bananas, maize, sweet potatoes and cassava (County Government of Murang’a, Citation2018).

2.2. Sampling and data collection

The study used primary data collected through a semi-structured questionnaire. A multistage sampling technique was employed in this study. In the first stage, Murang’a County was purposively selected since French beans is one of the three priority value chains that the county is promoting. It is also one of the few counties where horticultural produce exports are a significant economic activity. Murang’a South Sub-County was purposively selected at the second sampling stage because it leads in French beans production and has the highest number of smallholder farmers. In the third stage, four wards, namely, Kamahuha, Makuyu, Kimorori and Ichagaki, were purposively selected based on their production level. In the fourth stage, vertical coordination options (contract and non-contract farming) were purposively selected from each production ecology. Yamane (Citation1967) suggested that when the study area’s population size is known with certainty, the following formula is appropriate to determine the sample size.

where n is the sample size, is the total population of interest and e is the allowable margin of error. This gives a sample size of 215 respondents. French beans farmers were proportionately selected since the population in each ward was not equal in size. Finally, simple random sampling was used to select the respondents.

2.3. Empirical model

To measure the status of adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P. standards, the adoption index was used as developed by Kumar et al. (Citation2018) in the assessment of the influence of contract farming on the uptake of food safety standards in tomatoes. The study did an objective response from producers to determine whether they comply with each of the identified practices at the farm level. The farm practices followed largely related to infrastructure at the farm premise such as grading shade, charcoal coolers, tap, toilet, bathroom and chemical store; hygiene of produce, personnel and farm premise; traceability measures such as production record track, plot labeling, pesticide use record keeping; worker safety measures such as having full protective gear, worker health check, observing pre-harvest intervals, chemical sprayer equipment maintenance, pest and disease scouting, chemical use, disposal of chemical containers, environmental safety, adherence to pesticide residue limits, integrated pest management, water quality assessment, soil management, plant propagation material, plant nutrition management, packaging and transport of produce from the farm to the collection point. An aggregate score of good agricultural practices was then created by summing up all the responses given by a household. This served as a proxy for compliance with GLOBAL G.A.P. standards by a household.

The aggregate score for compliance with good agricultural practices for the household is given as follows:

Where, represents the

G.A.P. followed by the

household. The scores were standardized to calculate the probability of a score occurring.

was calculated as follows:

where is the GLOBAL G.A.P. adoption index,

is the household’s actual score,

is the minimum score for the households surveyed and

is the maximum score among households surveyed. Farmers were divided into three groups based on the adoption levels. Producers with scores 0–30 were termed as low adopters, 31–60 medium adopters and 61–100 as high adopters (Kumar et al., Citation2018). These groups were used to capture the status of compliance to good agricultural practices for all the vertical coordination options. The study also compared the mean

of contracted and non-contracted farmers as well as looked at their distribution by the level of adoption (See Table ).

Table 1. Target population and distribution in each ward

After calculating , the study used a generalized ordered logit model to determine factors influencing the degree of adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P. standards. This model is appropriate for this study because the dependent variable is categorical and ordered that is, the degree of adoption and a set of independent variables that influence the final probability. One major limiting assumption for ordered logistic regression is that the relationship between each pair of outcome groups is the same. The ordered logistic regression model is invariably based on the assumption that the corresponding coefficients (except the intercept) should be identical across different logistic regression (as defined by the level of compliance), with the exception of differences due to sampling variability (Williams, Citation2006). This is known as the proportional odds assumption or parallel regression assumption. However, this assumption is frequently violated and as a result, a generalized ordered model appears to be the most appropriate as it relaxes the assumption. This model was chosen for this study because it allows variable coefficients to vary across variable categories. If this is not true for all explanatory variables, the model is said to be partially constrained (Eluru, Citation2013).

Only a subset of variables has varying coefficients in the partially constrained generalized ordered logit model. The generalized logit model may be econometrically specified as follows:

(4)

where is the number of categories of the ordinal dependent variable, that is 3,

is the categorical variable for compliance degree.

is the intercept,

parameter to be estimated and

is a vector of explanatory variables. The probabilities that

will take on each of the values

or

is shown as follows:

where is the level of compliance to good agricultural practices by a farmer (

high adopter;

medium adopter;

low adopter).

represent the explanatory variables;

is a vector of parameters to be estimated;

represents the intercept while

is the error term.

The partially constrained model can be written as follows:

where the first subset of variables has a non-constrained coefficients across the values, and the second subset has the same coefficient across the values of The generalized ordered logit model corresponds to a series of binary logistic regressions in which the dependent variable’s categories are combined (Williams, Citation2006).

The variables in Table are chosen based on related literature (Gao et al., Citation2017; Jitmun et al., Citation2019; Karidjo et al., Citation2018; Kassie et al., Citation2015; Krause et al., Citation2016; Kumar et al., Citation2020; Ngwira et al., Citation2014; Rodthong et al., Citation2020; Zhao et al., Citation2018) and particular variables of interest hypothesized to influence adoption status of GLOBALG.A.Ps.

Table 2. Model variables hypothesized to influence the degree of Adoption of GLOBALG.A.Ps

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Contract farming stands to have a positive influence on compliance with GLOBAL G.A.P. standards at the farm level. The findings and relevant discussion on adoption levels are presented in Tables as follows; The results in the Table indicates that 61% of the farmers were contracted while 39% were non-contracted. The adoption level of GLOBAL G.A.Ps in French beans was significantly higher for contract farmers (66%) than non-contracted farmers (34%; Table ). Generally, 18% of the farmers were low adopters, 39% medium adopters while 43% were high adopters. The study equally revealed that 65% of the contracted farmers were high adopters, 35% medium adopters and zero percent for low adopters. On the other hand, it was found that 8% of non-contracted farmers were high adopters, 45% medium adopters whereas 47% were low adopters (Table ). The overall adoption of GLOBAL G.A.Ps was at 53% (Table ). The results also indicated that farmers used either one or a combination of options in selling their produce. The adoption level for different combinations was; contract farmers (66%), middlemen (38%), spot market (32%), middlemen and contract (70%), spot market and middlemen (32%) while those using spot market, middlemen and contract combination had an adoption level of 63% (Table ).

Table 3. Proportion of farmers on contract and non-contract options

Table 4. Adoption index for contract and non-contacted farmers

Table 5. Category of users of GLOBAL G.A.Ps

Table 6. Adoption levels for different vertical coordination options

According to Table results, proper disposal of empty chemical containers as an environmental safety parameter was very low (7%) posing a threat to the environment. This result is in line with Pandit et al. (Citation2017) where adoption of proper waste and pollution management was almost zero. Therefore, there is need to create more awareness among farmers on the importance of environmental conservation. Record keeping and plot labeling as a traceability parameters were fairly adopted at 57%. These practices were higher among contracted farmers (80%) than non-contracted farmers (17%). This can be attributed to the fact that export contractors provided labels and ledgers to the majority of the contracted farmers. The results also indicated that farmers had low compliance with health safety with only 8% of the farmers going for annual health checks. This finding is in line with Kassem et al. (Citation2021) However, Annor et al. (Citation2016) noted that farmers fully complied with health safety and welfare requirements. In the case of integrated pest management (IPM), fair adoption levels were reported especially in cultural practices and the use of less toxic chemicals and the overall uptake was 52%. Similarly, Kassem et al. (Citation2021) reported that farmers were partially compliant with IPM due to limited knowledge of environmentally friendly technology.

Table 7. Adoption levels as per GLOBAL G.A.P

Table shows results of the least, average and the most adopted GLOBAL G.A.P. among smallholder farmers. The average adoption rate for farm audit, irrigation water assessment, soil test analysis and charcoal cooler was 0%, which is extremely detrimental. The non-adoption of these practices was a result of the high cost incurred in acquiring these essential services. This result is in line with Panahzadeh Parikhani et al. (Citation2015) who found that economic constraint was one of the major barriers to the implementation of GAPs technologies in livestock units. Labeling of plots, preventing animal activities on the farms, use of safer and less toxic chemicals and use of a hat or scarf personal protective gear were fairly adopted at 59%, 53%, 55% and 54%, respectively. On the high end, the period between last pesticide use and resumption of harvesting, hygiene when handling chemicals, crop rotation and tidiness as site management were adopted at 93%, 95%, 93 and 90% respectively. Farmers were also good in compliance with chemical use prescriptions which contradicts results by Talukder et al. (Citation2017) where farmers relied on their own experience when determining chemical usage. Grading and proper handling of produce were good and the adoption level was 86%. The mean adoption of record-keeping of farm practices was 54%. Farmers were rational in choosing certified seed, and the adoption level was 79%.

Table 8. Adoption of Global Good Agricultural Practices (GGAPs) in French beans (N = 215)

3.2. Empirical results

Table presents results on the factors that influence smallholder farmers’ adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P. The findings show that, the coefficients for group membership and information access could not satisfy the parallel lines assumption. The violation of this assumption makes a generalized ordered logit model more appropriate for this study than the ordered logit or the ordered probit model.

Table 9. Results of the determinants of adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P. by the respondents

Age was negative and statistically significant at 1% level for the adoption of good agricultural practices among producers in the lower and medium user categories. The significant relationship with the intention suggests that younger farmers are more likely to adopt GLOBAL G.A.P. standards. Farmers’ average age was 46 years, indicating that the majority of French bean farmers are still in their productive years. This finding is consistent with the findings of Terano et al. (Citation2015), who found that younger farmers were more likely to adopt sustainable farming practices in rice. Contrary, Corallo et al. (Citation2020) found a negative correlation between young respondents and the adoption of a traceability system for dealing with consumer pressures.

Gender had a positive effect on the uptake of GLOBAL G.A.P. Gender was statistically significant at 10% level. Households with males as the key production decision-makers in the lower and medium user categories had a higher probability of adopting the GLOBAL G.A.P. A possible explanation for this is that majority of males have property rights thus have the discretion to adopt the new practices. Consequently, the majority of female-headed households are mostly widowed or divorced. In such situations, alongside the cultural factors, their likelihood of adopting good agricultural practices becomes negligible. Previous studies have found similar results (Keelan et al., Citation2009; Sennuga et al., Citation2020). However, Gao et al. (Citation2017) noted that female farmers had a higher adoption level of green control techniques relative to male farmers. According to the authors, females are more concerned with agricultural production quality and safety than male farmers.

Education indicates the human capital factor influencing the adoption of GLOBAL G.A.P. Education stock was positive and statistically significant at 1% level in the lower and medium user categories. This study suggests that households with a high number of formal schooling are more equipped with skills to understand the importance of GGAPs and can influence adoption. This result corroborates with previous findings in the adoption studies. For instance, Srisopaporn et al. (Citation2015) noted that education improves producers’ ability to adjust to changes. Additionally, years of schooling among orchid producers positively influenced the adoption of Q-G.A.P. in Thai (Krause et al., Citation2016).

Household size is a proxy variable for the labor force participation and household dependency ratio. Household size was negative and statistically significant at 1% level in the lower and medium user categories. This implies that every additional adult person in a household reduces the probability for the adoption of GGAPs by 11%. This can be explained by the fact that big families have higher expenditures thus more money is spent on family needs than on the farm. Similarly, Nthambi et al. (Citation2013) reported that an increase in the number of people results in a decrease in individual compliance with good agricultural practices in export vegetables. However, Belachew et al. (Citation2020) found that family size positively influenced the uptake of water conservation measures in Ethiopian highlands.

Contact with extension officers was related to an increase in the adoption rate. Extension contact was positive and significant at 5% level in the lower and medium used categories. A probable explanation is that farmers with frequent extension contact are more likely to trust the information received and consider following the idea. Similarly, Tu et al. (Citation2018) found that low uptake levels of good agricultural technologies were linked to inadequate extension contacts.

Farming experience in French beans production was positive and statistically significant at 1% level among farmers in the lower and medium user categories. The number of years involved in farming was positively and significantly associated with the implementation of the GLOBAL G.A.P. This result implies that farming experience has a significant impact on the adoption of good agricultural practices. This finding is consistent with the findings of Suwanmaneepong et al. (Citation2016), who found that implementation of the GAPs at the farm level was based on farming experience. However, Huang and Kamarinzira 2018 found that producers with more years of farming experience were more likely to stick with the original methods that are familiar to them rather than try out newer farming techniques.

The study equally revealed that participation in GLOBAL G.A.P. training was positive and statistically significant at 1% level among producers in the lower and medium user categories. This implies that households that undertake training through either the government or private organizations are correlated with higher adoption levels. This finding suggests the importance of creating awareness among smallholder French beans producers. Similarly, Pongvinyoo et al. (Citation2014) found that conducting a group training program or a workshop effectively influences the adoption of good farm practices. However, Khin (Citation2016) argued that training access had a negative correlation with the uptake of G.A.P. According to Khin, training attendance disappointed once farmers realized the cost and benefits associated with the adoption of the G.A.P. program.

The findings further showed that membership in a group had a positive influence on the uptake of GLOBAL G.A.P. Membership to a group was statistically significant at 5% level among farmers in the lower user category. A possible explanation is that farmers who participated in agricultural groups may have had better access to information about the effectiveness and benefits of the new practices. Moreover, over time, members of a group socialize and develop similar norms and preferences for farm management practices. This result is consistent with that of Tu et al. (Citation2018), where participation in agricultural cooperatives or clubs had a positive impact on the adoption of eco-friendly rice. However, Connor et al. (Citation2020) found that membership in a group reduced farmer’s uptake of rice straw management practices.

Information access was negative and statistically significant at 5% level among households in the lower user category. Information sources such as social media, barazas, neighbors, friends and relatives negatively influenced the adoption of G.A.Ps. This can be attributed to the fact that information provides farmers with cost and benefits and thus producers are likely not to adopt if the threats are higher than opportunities. Likewise, Gao et al. (Citation2017) noted that frequent communication with neighbors had a negative effect on the adoption of green control techniques among farmers. Contrary, Sharma and Peshin (Citation2016) found that information access positively influenced the adoption of IPM in Indian vegetables. The authors argued that information access through media publicity made farmers understand the features and advantages of integrated pest management.

Vertical coordination options was positive and statistically significant at 10% level among farmers in the lower and medium user categories. This implies that participation in contract farming increased the likelihood of adopting the GLOBAL G.A.P. Contract farming is the dominant vertical coordination option conducive for promoting farmer’s safe production behavior (Lu et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Hou et al. (Citation2020) found that contract arrangement significantly increased the adoption of food safety governance in the agri-food supply chain.

Availability of the outlet was negative and statistically significant at 1% level among farmers in the lower and medium user categories. Producers’ perception on the readily available markets reduced their likelihood of adopting good farm practices. This implies that readily available markets made farmers reluctant in employing global good agricultural practices. This could be possible because with or without adoption they could still sell their produce.

The outlet reliability was positive and statistically significant at 5% level among farmers in the lower and medium user categories. The perception of the reliability of the market increased the likelihood of GLOBAL G.A.P. adoption. This suggests that farmers were motivated to adopt good agricultural practices by the market’s reliability in terms of fair prices and timely payment. This finding is consistent with that of Zhao et al. (Citation2018) who argued that the adoption of food safety measures in raw milk was influenced by market incentives.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

The survey results showed that the overall adoption rate of good agricultural practices was fair. Contracted farmers had a higher compliance rate compared to non-contracted farmers. For instance, none of the non-contracted farmers observed environmental safety G.A.P. The adoption rate for some GLOBAL G.A.P. was very low, including annual health checks, proper disposal of chemical containers, soil test analysis, irrigation water analysis, and establishment of charcoal coolers. The Gologit model was applied to study the determinants of adoption of good agricultural practices. Findings from the survey revealed that several factors influenced uptake of GLOBAL G.A.P. which include age, education, gender, household size, vertical coordination options, group membership, training, extension service, farming experience and reliability of the market.

The low level of adoption of some GLOBAL G.A.P. is a cause for concern. The inability of farmers to follow these practices not only reduces their competitiveness in the international market but also exposes local consumers to the risk of eating vegetables and fruits that are below acceptable standards. With contract participation showing prospects of higher compliance, the government through extension officers should create more awareness on the importance of contract farming in enhancing the adoption of GGAPs.

The study makes the following recommendations based on the empirical findings: First, The government should organize more training on the latest GLOBAL G.A.P. trends, especially for smallholder farmers. Training should target the youth since the aging farmers are less likely to comply with GLOBAL G.A.P. standards. Second, the government should consider how to make compliance easier and more affordable for farmers by establishing minimum prices for horticultural produce to cover compliance costs. Third, extension service providers should sensitize farmers on the need to adopt good agricultural practices, essential to assist farmers in remaining competitive in the global market. Fourth, the government should prioritize maximizing smallholder farmers’ production potential by encouraging group formation, subscription and active participation. Finally, both the private and public sectors should invest in the provision of agricultural credit to farmers. This could be improved by establishing rural financial institutions that encourage rural savings while providing farmers with lower-interest loans.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data used in this study is available upon request. We understand the share upon reasonable request data policy https://github.com/Naomi-Chebi/Naomi-Chebiwot-Chelang-a/blob/main/GOLOGIT%20DATA.dta.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Naomi Chebiwot Chelang’a

Naomi Chebiwot Chelang’a PhD student in Agribusiness management at Egerton University, Kenya. The second author is a senior lecturer of Agricultural Economics at Egerton University. The third author is a professor of Agricultural Economics at Egerton University and the Director for Tegemeo Institute of Agricultural policy and Development. The fourth author is a doctor of Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development, Egerton University.

References

- Aguilar-Gallegos, N., Muñoz-Rodríguez, M., Santoyo-Cortés, H., Aguilar-Ávila, J., & Klerkx, L. (2015). Information networks that generate economic value: A study on clusters of adopters of new or improved technologies and practices among oil palm growers in Mexico. Agricultural Systems, 135, 122–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2015.01.003

- Ali, J. (2012). Factors influencing adoption of postharvest practices in vegetables. International Journal of Vegetable Science, 18(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315260.2011.568998

- Anaglo, J. N., Boateng, S. D., Swanzy, F. K., & Felix, K. M. (2014). The influence of adoption of improved oil palm production practices on the livelihood assets of oil palm farmers in Kwaebibirem District of Ghana. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 4(1), 88–94. http://www.iiste.org/

- Annor, P. B. (2018). Smallholder farmers’ compliance with GlobalGAP standard: The case of Ghana. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, 8(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/EEMCS-03-2017-0043

- Annor, B. P., Mensah-Bonsu, A., & Jatoe, J. B. D. (2016). Compliance with GLOBALGAP standards among smallholder pineapple farmers in Akuapem-South, Ghana. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 6(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-05-2013-0017

- Ba, H. A., de Mey, Y., Thoron, S., & Demont, M. (2019). Inclusiveness of contract farming along the vertical coordination continuum: Evidence from the Vietnamese rice sector. Land Use Policy, 87, 104050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104050

- Belachew, A., Mekuria, W., & Nachimuthu, K. (2020). Factors influencing adoption of soil and water conservation practices in the northwest Ethiopian highlands. International Soil and Water Conservation Research, 8(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2020.01.005

- Cafer, A. M., & Rikoon, J. S. (2018). Adoption of new technologies by smallholder farmers: The contributions of extension, research institutes, cooperatives, and access to cash for improving tef production in Ethiopia. Agriculture and Human Values, 35(3), 685–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-9865-5

- Connor, M., Annalyn, H., Quilloy, R., Van Nguyen, H., Gummert, M., & Sander, B. O. (2020). When climate change is not psychologically distant-Factors influencing the acceptance of sustainable farming practices in the Mekong River Delta of Vietnam. World Development Perspectives, 18, 100204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100204

- Corallo, A., Latino, M. E., Menegoli, M., & Striani, F. (2020). What factors impact on technological traceability systems diffusion in the agri-food industry? An Italian survey. Journal of Rural Studies, 75, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.02.006

- County Government of Murang’a. (2018). Murang’a County Integrated Development Plan Report (2018-2022). https://devolutionhub.or.ke/resource/muranga-county-integrated-development-plan-2018-2022

- Diiro, G. M. (2013). Impact of off-farm income on agricultural technology adoption intensity and productivity evidence from rural maize farmers in Uganda.

- Eluru, N. (2013). Evaluating alternate discrete choice frameworks for modeling ordinal discrete variables. Accident Analysis and Preventions, 55, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2013.02.012

- FAO. (2019). FAOSTAT Production Data. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

- Gao, Y., Zhang, X., Lu, J., Wu, L., & Yin, S. (2017). Adoption behavior of green control techniques by family farms in China: Evidence from 676 family farms in Huang-huai-hai Plain. Crop Protection, 99, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2017.05.012

- Gichuki, C. N., Gicheha, S. K., & Kamau, C. W. (2020). Do food certification standards guarantee small-sized farming enterprises access to better markets? Effectiveness of marketing contracts in Kenya. International Journal of Social Economics, 47(4), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-08-2019-0501

- Gichuki, C. N., Han, J., & Njagi, T. (2020). The impact of household wealth on adoption and compliance to GLOBAL GAP production standards: Evidence from smallholder farmers in Kenya. Agriculture, 10(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10020050

- Hailu, B. K., Abrha, B. K., & Weldegiorgis, K. A. (2014). Adoption and impact of agricultural technologies on farm income: Evidence from Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics (IJFAEC), 2(4), 91–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.190816

- Hou, J., Wu, L., & Hou, B. (2020). Risk Attitude, Contract Arrangements and Enforcement in Food Safety Governance: A China’s Agri-Food Supply Chain Scenario. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2733. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082733

- Huang, Z., & Karimanzira, T. T. P. (2018). Investigating Key Factors Influencing Farming Decisions Based on Soil Testing and Fertilizer Recommendation Facilities (STFRF). A case study on rural Bangladesh. Sustainability, 10(11), 4331. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114331

- Islam, A. H. M., Roy, D., Kumar, A., Tripathi, G., & Joshi, P. K. (2019). Dairy contract farming in Bangladesh: Implications for welfare and food safety (Vol. 1833). International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Jelsma, I., Woittiez, L. S., Ollivier, J., & Dharmawan, A. H. (2019). Do wealthy farmers implement better agricultural practices? An assessment of implementation of Good Agricultural Practices among different types of independent oil palm smallholders in Riau, Indonesia. Agricultural Systems, 170, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.11.004

- Jitmun, T., Kuwornu, J. K., Datta, A., & Anal, A. K. (2019). Farmers’ perceptions of milk-collecting centres in Thailand’s dairy industry. Development in Practice, 29(4), 424–436.

- Kabir, M. H., & Rainis, R. (2015). Adoption and intensity of integrated pest management (IPM) vegetable farming in Bangladesh: An approach to sustainable agricultural development. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 17(6), 1413–1429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-014-9613-y

- Karidjo, B. Y., Wang, Z., Boubacar, Y., & Wei, C. (2018). Factors influencing farmers’ adoption of soil and water control technology (SWCT) in Keita valley, a semi-arid Area of Niger. Sustainability, 10(2), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020288

- Kassem, H. S., Alotaibi, B. A., Aldosari, F. O., Herab, A., & Ghozy, R. (2021). Factors influencing smallholder Orange farmers for compliance with GobalGAP standards. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 28(2), 1365–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.070

- Kassie, M., Teklewold, H., Jaleta, M., Marenya, P., & Erenstein, O. (2015). Understanding the adoption of a portfolio of sustainable intensification practices in eastern and Southern Africa. Land Use Policy, 42, 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.08.016

- Keelan, C., Thorne, F., Flanagan, P., & Newman, C. (2009). Predicted willingness of Irish farmers to adopt GM technology. The Journal of Agro Biotechnology Management and Economics, 12(3), 394–403. http://hdl.handle.net/10355/6929

- Kenya Export Promotion and Branding. (2020). Integrated Marketing Communication Strategy to Boost Kenya’s Horticultural Export Report. https://brand.ke

- Khin, Y. O. (2016). Case studies of Good Agricultural Practices (G.A.Ps) of farmers in Thailand. Center for Applied Economic Research. Kasetsart University.

- Krause, H. (2020). Upgrading horticultural value chains for enhanced welfare and food security: Case studies from Thailand and Kenya (Doctoral dissertation Institutionelles Repositorium der Leibniz Universität Hannover). https://doi.org/10.15488/9753

- Krause, H., Lippe, R. S., & Grote, U. (2016). Adoption and income effects of public GAP standards: Evidence from the horticultural sector in Thailand. Horticulture, 2(4), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae2040018

- Kumar, A., Mishra, A. K., Saroj, S., Sonkar, V. K., Thapa, G., & Joshi, P. K. (2020). Food safety measures and food security of smallholder dairy farmers: Empirical evidence from Bihar, India. Agribusiness, 36(3), 363–384. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21643

- Kumar, A., Roy, D., Tripathi, G., Joshi, P. K., & Adhikari, R. P. (2016). Can contract farming increase farmers’ income and enhance adoption of food safety practices in remote areas of Nepal? International Food Policy Research Institute Discussion Paper, 1524, 1–25. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anjani-Kumar-16/publication/301586582

- Kumar, A., Roy, D., Tripathi, G., Joshi, P. K., & Adhikari, R. P. (2018). Does contract farming improve profits and food safety? Evidence from tomato cultivation in Nepal. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 8(3), 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-09-2017-0095

- Laosutsan, P., Shivakoti, G. P., & Soni, P. (2019). Factors influencing the adoption of good agricultural practices and export decision of Thailand’s vegetable farmers. International Journal of the Commons, 13(2), 867–880. http://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.895

- Lu, W., Latif, A., & Ullah, R. (2017). Simultaneous adoption of contract farming and off-farm diversification for managing agricultural risks: The case of flue-cured Virginia tobacco in Pakistan. Natural Hazards, 86(3), 1347–1361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-2748-z

- Ma, W., & Abdulai, A. (2019). IPM adoption, cooperative membership and farm economic performance. China Agricultural Economic Review, 11(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-12-2017-0251

- Mariano, M. J., Villano, R., & Fleming, E. (2012). Factors influencing farmers’ adoption of modern rice technologies and good management practices in the Philippines. Agricultural Systems, 110, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2012.03.010

- Mold, A., & Mveyange, A. (2020). The Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Trade: Recent evidence from East Africa. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/impact-covid-19-crisis-trade-recent-evidence-east-africa/

- Moturi, W., Obare, G., & Kahi, A. (2015). Milk Marketing Channel Choices for Enhanced Competitiveness in The Kenya Dairy Supply Chain: A multinomial Logit Approach (No. 1008-2016-80202). Review in Agricultural and Applied Economics Journal. http://dx.doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.212477

- Mwangi, W. P., Otieno, A., & Anapapa, A. (2019). Assessment of French Beans Production at Kariua in Kandara, Murang’a County-Kenya. Asian Journal of Probability and Statistics, 5(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajpas/2019/v5i430141

- Ngwira, A., Johnsen, F. H., Aune, J. B., Mekuria, M., & Thierfelder, C. (2014). Adoption and extent of conservation agriculture practices among smallholder farmers in Malawi. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 69(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.2489/jswc.69.2.107

- Nthambi, M., Mburu, J. I., & Nyikal, R. (2013). Smallholder Choice of Compliance Arrangements: The Case GlobalGAP adoption by French Bean Farmers in Kirinyaga, Mbooni and Buuri/Laikipia Districts (No. 309-2016-5178). http://dx.doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.161471

- Ntshangase, N. L., Muroyiwa, B., & Sibanda, M. (2018). Farmers’ perceptions and factors influencing the adoption of no-till conservation agriculture by small-scale farmers in Zashuke, KwaZulu-Natal Province. Sustainability, 10(2), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020555

- Panahzadeh Parikhani, M., Razzaghi Borkhani, F., Shabanali Fami, H., Motiee, N., & Hosseinpoor, A. (2015). Major barriers to application of Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) technologies in sustainability of livestock units. International Journal of Agricultural Management and Development, 5(3), 169–178. DOI:/2010.5455/ijamd.161640

- Pandit, U., Nain, M., Singh, R., Kumar, S. H. I. V., & Chahal, V. (2017). Adoption of Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) in Basmati (Scented) rice: A study of prospects and retrospect. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 87(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.56093/ijas.v87i1.66998

- Paraffin, A. S., Zindove, T. J., & Chimonyo, M. (2018). Perceptions of factors affecting milk quality and safety among large and small‐scale dairy farmers in Zimbabwe. Journal of Food Quality, (2018(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5345874

- Pongvinyoo, P., Yamao, M., & Hosono, K. (2014). Factors Affecting the Implementation of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) among Coffee Farmers in Chumphon Province, Thailand. American Journal of Rural Development, 2(2), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajrd-2-2-3

- Rodthong, W., Kuwornu, J. K., Datta, A., Anal, A. K., & Tsusaka, T. W. (2020). Factors Influencing the Intensity of Adoption of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil Practices by Smallholder Farmers in Thailand. Environmental Management, 66(3), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01323-3

- Saadun, N., Lim, E. A. L., Esa, S. M., Ngu, F., Awang, F., Gimin, A., Azhar, B., Firdaus, M. A., Wagimin, N. I., & Azhar, B. (2018). Socio-ecological perspectives of engaging smallholders in environmental-friendly palm oil certification schemes. Land Use Policy, 72, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.12.057

- Sennuga, S. O., Baines, R. N., Conway, J. S., & Angba, C. W. (2020). Awareness and adoption of Good agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in relation to the adopted villages program: The case study of Northern Nigeria. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 10(6), 34–49. http://www.iiste.org/

- Sharma, R., & Peshin, R. (2016). Impact of integrated pest management of vegetables on pesticide use in subtropical Jammu, India. Crop Protection, 84, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2016.02.014

- Srisopaporn, S., Jourdain, D., Perret, S. R., & Shivakoti, G. (2015). Adoption and continued participation in a public Good Agricultural Practices program: The case of rice farmers in the Central Plains of Thailand. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 96, 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.03.016

- Suwanmaneepong, S., Kullachai, P., & Fakkhong, S. (2016). An investigation of factors influencing the implementation of G.A.P. among fruit farmers in Rayong Province. Thailand. International Journal of Agricultural Technology, 12(7.2), 1745–1757. http://www.ijat-aatsea.com/

- Talukder, A., Sakib, M. S., & Islam, M. A. (2017). Determination of influencing factors for integrated pest management adoption: A logistic regression analysis. Agrotechnology, 6(163), 2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9881.1000163

- Terano, R., Mohamed, Z., Shamsudin, M. N., & Latif, I. A. (2015). Factors influencing intention to adopt sustainable agriculture practices among paddy farmers in Kada, Malaysia. Asian Journal of Agricultural Research, 9(5), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajar.2015.268.275

- Tesfaye, M. Z., Balana, B. B., & Bizimana, J. C. (2021). Assessment of smallholder farmers’ demand for and adoption constraints to small-scale irrigation technologies: Evidence from Ethiopia. Agricultural Water Management, 250, 106855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.106855

- Trifkovic, N. (2014). Food Standards & Vertical Coordination in Aquaculture: The Case of Pangasius from Vietnam. (No. 2014/01). IFRO Working paper. Econstor.

- Tu, V. H., Can, N. D., Takahashi, Y., Kopp, S. W., & Yabe, M. (2018). Modelling the factors affecting the adoption of eco-friendly rice production in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 4(1), 1432538. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1432538

- Williams, R. (2006). Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. The Stata Journal, 6(1), 58–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0600600104

- Wollni, M., Romero, C., Saenz, F., & Le Coq, J. F. (2012). Vertical coordination and standard adoption: Evidence from the Costa Rican pineapple sector. https://agritrop.cirad.fr/567288/1/document_567288.pdf

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis (2nd) ed.). Harper and Row.

- Zhao, L., Wang, C. W., Gu, H., & Yue, C. (2018). Market incentive, government regulation and the behavior of pesticide application of vegetable farmers in China. Food Control, 85, 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.09.016