?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Tomato is a major vegetable crop produced in most towns in Ghana, especially in the Offinso-North District of the country, and serves as a means of livelihood in terms of the income to the producers. To critically reduce postharvest losses to help increase the amount of food available for consumption, this study examined the value of postharvest losses among tomato farmers in Ghana. The data, which were obtained from 203 tomato producers, were analyzed using descriptive statistics, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance as well as fractional response and Box Cox regression models. The results revealed the quantity and the financial value of post-harvest losses among the tomato producers to be 3506.3 kg and GH₵3598.7, respectively. We also find that the primary cause of postharvest loss was mainly rot and bruise. This occurred as a result of unavailability of reliable markets. In addition, the results of the fractional response regression model showed that level of education and unavailability of market have significant positive effects on the proportion of tomato lost. Finally, the results of the Box Cox Regression model showed that whereas the value of postharvest losses and transportation cost have negative relationships with the revenue generated from sales, quantity of tomato harvested exerted a positive influence on the revenue obtained. The study recommends the need for stakeholders’ intervention in the building and provision of storage facilities, good road networks, processing factories in tomato producing towns, ready markets, as well as dams to help supply water all year round for continuous tomato production.

1. Introduction

Food production will have to increase by 70% in order to satisfy the world’s estimated population of 9 billion people in 2050 (FAO/OECD, Citation2011). Ensuring food security is one of the major challenges for a growing world population (Kiaya, Citation2014). Meanwhile, in each year, food insecurity remains unbearably high worldwide (FAO, 2012). This is as a result of the substantial amount of food that is lost due to infestation and spoilage before reaching the consumer (FAO, Citation2011). Postharvest loss, a measurable loss in edible food mass (quantity) or nutritional value (quality) of food intended for human consumption, continue to be an issue of concern to farmers and policy makers in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Statistics show that postharvest loss is a major cause of the food insecurity problem adversely affecting an estimated 374 million people in SSA (FAO, Citation2018; Adams et al., Citation2021). The issue of postharvest loss is a systemic one. This includes a range of intertwined activities along the value chain (from time of harvest through to consumer level). Large quantities are lost every year at various stages in the value chain before reaching the final consumer (FAO, Citation2018).

Postharvest losses in Ghana have been estimated at between 20% and 50% (Aidoo et al., Citation2014; Gonzalez et al., Citation2014) and this is attributed to several causes of which poor postharvest handling has been identified as one of the main causes (Zu et al., Citation2014; Aidoo et al., Citation2014; Amicarelli & Bux, Citation2020). Yeboah (Citation2011) also indicated in his report that farmers and traders lack the knowledge and skill in maintaining the quality of fresh tomatoes, and hence, in extending the shelf life of these harvested tomatoes, the trend of high levels of postharvest loss may persist. This high level of losses of tomatoes and other food crops cause random food shortages and severe fluctuations in the prices of food commodities, rendering the impoverished and vulnerable stakeholder food insecure in society (Amoako-Adusei, Citation2020). Furthermore, Ghana News Agency (GNA) identified postharvest loss as one of the major causes of food insecurity and poverty (GNA, Citation2017). Also, farmers become traumatized as a result of their inability to service the debt owed to the input suppliers from the income and proceeds of the sales they make from production.

Tomato made the highest portion (11.6%) of household vegetable expenditure according to Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) 2017. However, in the 2020 GLSS report, tomato maintained its position on the household vegetable expenditure but had reduced significantly to 9.7%. Meanwhile, its consumption increased steadily from around 280,000 tons in 2005 to more than 450,000 tons in 2013 (FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Citation2019; Van Asselt et al., Citation2018).

In Ghana, despite expanding tomato production from 318,000 tons in 2009 to 420,000 tons in 2019 (FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Citation2019; MoFA Ministry of Food and Agriculture, Citation2020) – an average annual output growth rate of 2.8 percent, the country is still regarded as producing low volumes of tomato. The low production volume in tomato production could be attributed to the seasonal nature of the tomato production (Amoako-Adusei, Citation2020). Due to this, there is the importation of tomatoes from neighbouring countries such as Burkina Faso to meet the growing demand (Melomey et al., Citation2019; Robinson & Kolavalli, Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2010c). It is of interest to know that, imported tomatoes are reported to be of high quality than local tomatoes, possibly due to improved varieties (Van Asselt et al., Citation2018). Fresh tomato imports into Ghana are valued at 9 million U.S. dollars annually (Van Asselt et al., Citation2018).

The target of the various stakeholders in the tomato industry in Ghana has mainly been to focus on increasing the capacity of tomato production. However, farmers lose a huge chunk of their investment in tomato production as a result of postharvest losses they encounter along the tomato value chain (Robinson and Kolavalli, Citation2010a; Abera et al., Citation2020). Robinson and Lolavalli (Citation2010a) as well as Pathare et al. (Citation2021) reported that tomato and lettuce led the chart having recorded about 20% of loss 5 days after harvesting. In Ghana, about 15,300 metric tons (30%) of tomatoes harvested are lost from the annual 51,000 metric tons of fresh tomatoes produced. For instance, the Offinso North District in 2011 lost about 6045 metric tons representing 31% of the 19,500 metric tons of fresh tomatoes produced at the postharvest stage (MoFA, Citation2011).

Reducing postharvest loss increases food available for consumption. Evidence from GNA (Citation2017) also suggested that in managing the postharvest loss of a specific food commodity is generally lesser than the cost of producing the same quality of the food commodity. Thus, it is critical to reduce postharvest loss if we are to ensure the food security of the citizens. However, farmers will continue to face postharvest losses if proper methods are not employed to restrain the effects. The various stakeholders along the value chain are negatively affected by these adverse effects in one way or the other. The negative effects of postharvest loss are largely through income loss and food insecurity. This therefore calls for the urgency in dealing with issues of postharvest losses to help address these growing concerns. However, not much attention has been given to valuing the income losses of smallholder farmers who constitute about 90% of tomato producers in Ghana. This study, therefore, seeks to address the following relevant questions; what are the quantities and the corresponding financial value of postharvest losses in tomato production? What are the determinants of postharvest losses? and what are the effects of postharvest losses on the income of producers?

2. Literature review

Tomato remains one of the common horticultural crops in the world (Abera et al., Citation2020). It is very significant in human diets in account of its naturally enriched vitamins and minerals nutrient sources (Yusufe et al., Citation2017). Tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill) belong to the Solanaceae family with such species as pepper, eggplant, tobacco, and potato (van Dam et al., Citation2005). Consumers eventually accepted tomatoes when it was commercialized in 1960 (Anaba, Citation2018). They also indicated that tomato is a short duration crop and requires relatively cool, and dry climate for good yield. According to Horna et al. (Citation2008), Ghana imports tomatoes every six months because of the rise in demand as compared to its supply locally. In Ghana, two towns, Wenchi and Akumadan in the Bono and Ashanti regions, respectively, experience high tomato production (Amartey, Citation2013).

Postharvest loss (PHL) can be defined as the resulting quantitative loss, qualitative loss and food waste from the stage of harvesting to the stage of consumption (Kiaya, Citation2014). According to Anaba (Citation2018), inappropriate harvesting method and how facilities occur during transportation, storage, and even market centers bring about postharvest losses. Food loss is grouped into quantitative and qualitative loss. Qualitative loss measures a decrease in nutritive level and unusual changes in appearance of food. Quantitative only looks at the reduction in volume (Al-Zabir, Citation2020)

Several factors are found to have influence on postharvest losses. In identifying the determinants of postharvest losses, various scholars in their study revealed some factors that influence postharvest losses. These are classified into mechanical, chemical, biological, physiological, physical and environmental factors (Atanda et al., Citation2011; FAO, Citation2011; Kader, Citation2005; Kitinoja & Cantwell, Citation2010; World Bank, FAO and NRI, Citation2011; Mebratie et al., Citation2015). All these factors influence the quantity and quality of the product from production to consumptions levels along the value chain (Kikulwe et al., Citation2018).

Socioeconomic factors such as farm size, age of fruit at harvest, age of respondent, level of education, household size and experience were hypothesized to influence tomato losses both positively and negatively (Aidoo et al., Citation2014; Wongnaa et al., Citation2014; Arah et al., Citation2015). Kulwijira (Citation2021) found that, age, education, age of fruit at harvest, quantity harvested, storage facilities, available markets, and experience had significant effects on the postharvest losses of grapes at the farm level. Kuranen-Joko and Liambee (Citation2017) in the study of determinants of postharvest losses among tomato farmers in Gboko Local Government Area of Benue State found that age, farming experience, years of formal education, farm size, days to storage and market, household size, number of extension visits, and labour type are important in analyzing postharvest losses. Other factors such as storage facilities, available markets, long distance to farm were also identified to influence tomato losses (Munhuweyi et al., Citation2016; Sibomana et al., Citation2016).

Alidu et al. (Citation2016) observed that a farmer with higher experience often has full knowledge of postharvest losses. It was identified that larger household size reduced postharvest losses since there will be an increase in labour use. Similarly, in a research conducted by Woldu et al. (Citation2015), it was found that experience was significant in all the levels (farm, wholesale and retail) of study such as age, market distance, number of days of storage, means of transport as well as storage significantly influenced postharvest losses. In spite of some studies that have been done on drivers of postharvest losses of tomato, to the best of our knowledge no analysis was identified to have estimated the impact of factors such as available market, long distance to market and storage facilities.

Both Ganiu (Citation2019) in a thesis report on assessment of postharvest losses along the fresh tomato value chain in the Upper East region of Ghana and Aidoo et al. (Citation2014) in a research on the determinants of postharvest losses on tomato production in Offinso North district of Ghana computed the quantity of tomato lost in the growing season together with the revenue a farmer obtained in the cropping season. The potential revenue a farmer could have generated in the absence of loss was also calculated alongside the percentage of loss in both the major and minor season. However, analysis on the income a farmer obtained was not done. Following the gap in literature, this study considers the income analysis from the revenue obtained in the cropping season by computing the variable cost incurred during the cropping season.

In estimating the parameters on the effects of postharvest losses on the revenue of producers using the double log regression, Alidu et al. (Citation2016) in the study on the determinants of postharvest losses among tomato farmers in the Navrongo Municipality in the Upper East Region found that farm size, labour cost (cost of labour), cost of fertilizer, cost of agrochemical, cost of transportation) and postharvest value influenced the revenue of the tomato producer.

As posited by Amoako-Adusei (Citation2020) in the economic analysis of tomato postharvest losses and postharvest technologies, he indicated that tomato producers who were members of local associations experienced significantly lower losses. Also, producers had a poor perception about using a postharvest technology. The producers who perceived the cost of the postharvest technologies to be greater than the benefits were less likely to use the technology. It was also found that the white cloth was a better investment option in comparison to the zero-energy cooling chamber. In the analysis of the cash flow of using the white shade cloth investment, the fixed and the variable cost as well as the revenue was computed (Verploegen et al., Citation2021). However, even though earlier studies (Odeyemi et al., Citation2021) did not analyze the cost of transportation as a variable cost, this study considers the cost of transportation as a part of the variable cost incurred.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

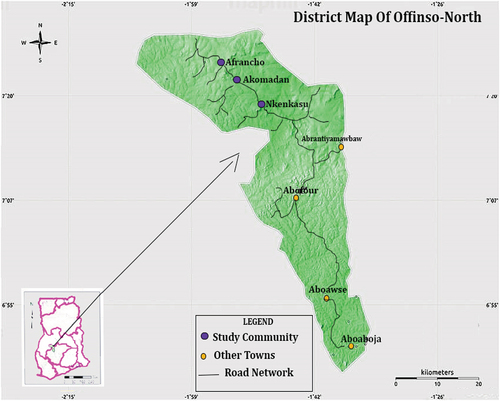

Data for this study is obtained from Offinso North District of Ashanti region of Ghana, see details in Figure . The study was conducted in principal towns including Akumadan, Afrancho, and Nkenkaasu. The district lies in the northern part of the Ashanti region approximately between latitude 7° 15”N and 6° 95”N, and between longitude 1° 35’ and 1° 75’W. It occupies an estimated area of 600 sq km. The 2010 Population and Housing census revealed 76,895 people in the district with an annual growth rate of 1.6%. Out of this, 39832 (51.8%) were females and the remaining 37,064 (48.2) were male folks. However, MoFA (Citation2022) projected the population to be 172,727 out of which 116,477 are female and 56,250 are males. The inhabitants of this district are mostly farmers. The farming population in the district is around 30,000 with 15,030 occupying the male folk and 14,970 being females. Statistics according to MoFA showed that farming activities are dominated by the youth (15–34 years) in the district. They constitute 30% of the farming population (MoFA, Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2022). The district experiences a bimodal rainfall regime with a mean annual rainfall level ranging between 700 mm and 1200 mm. During the rainy season, humidity could rise as high as 90% within the district. The average temperature reading recorded monthly is 27°C. Most parts of the district have moist semi-deciduous forest with thick vegetation cover and undergrowth vegetation. Offinso North District has an undulating topography with the highest elevation of about 585 m above sea level and a low lying plain between 180 cm and 300 cm above sea level. The rich and tremendous arable land in the district supports a wide range of crop and animal production. Both tree and food crops do well in this area. The Offinso North District is notable in vegetable production especially tomato and okra (MoFA, Citation2022).

The population for this study was made up of tomato farmers in the Offinso-North District. The study considered three major towns in the district noted for tomato production. These towns were Akumadan, Afrancho, and Nkenkaasu. The tomato farming population in the district is around 30,000 (MoFA, Citation2022), and therefore the sample size for the study was determined using Yamane’s formula (1967) as follows:

Where;

sample size

the population size (30,000)

the acceptable sampling error (using 0.07)

The application of the Yamane’s formulae yielded a sample of 203. The study employed the multi-stage sampling technique in selecting the 203 tomato producers. The first stage involved the purposive selection of the Offinso North district of the Ashanti Region of Ghana. Offinso North district was selected due to its popularity in tomato production in Ghana. The second and final stage involved the random selection of 68 farming households from each of the aforementioned three (3) communities within the district with the help of agricultural extension agents in the district. Data was collected on socioeconomic characteristics like educational background, age, sex, and the household size of the respondents. Other variables on which data were collected were the cost of labour, cost of fertilizer, cost of transportation, and cost of agrochemical. Secondary information was accessed through a review of articles, research publications, journals, via the internet, and institutions. Secondary information was accessed through a review of articles, research publications, journals, via the internet, and institutions.

The descriptive statistics of characteristics of the sampled tomato producers are presented in Table . It was found from the results that 85.22% of the respondents were males while 15.78% were females (Table ). This result is consistent with the findings of Amoako-Adusei (Citation2020) who studied economic analysis of tomato postharvest losses in Ghana and found 71% of the sampled producers to be males. Abera et al. (Citation2020) in their research article titled assessment of postharvest losses of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) in selected districts of East Shewa zone of Ethiopia using a commodity system of analysis methodology revealed that 69.7% of the respondents were men while 30.3% were women. Tsakpoe (Citation2019) also reported that vegetable production is exclusively done by men in his research on socioeconomic analyses of vegetable production and marketing in Tamale, Northern region. Kuranen-Joko and Liambee (Citation2017) after studying on determinants of postharvest losses among tomato farmers in Gboko Local Government Area of Benue State reported that males constituted 64% of the respondents interviewed.

Table 1. Summary of farmers’ characteristics

In terms of the age of respondents, the age range reported was 25 years and 68 years with a mean age of 43.14 years (Table ). This result agrees with Kulwijira (Citation2021) who found the mean age to be 44.86 years in the study of the socio-economic determinants of postharvest losses in the grape value chain in Dodoma municipality and Chamwino district, Tanzania and that of Amoako-Adusei (Citation2020) who reported that the majority of the respondents interviewed were above 35 years. The household size ranges from 1 to 10 with a mean of 5.29 (Table ). This result corroborates with Kulwijira (Citation2021) who researched and found out that there was an average family size of 6 and 7 for grape farmers. This result is also in line with Abera et al. (Citation2020) who identified the mean family size to be 5.5 from a range of 1 to 10 family members per household. Table 4.1 showed that an interviewed tomato producer with the least years in farming experience is 1 and the maximum number of years is 40 with a mean of 14.66 years. This concurs with Kulwijira (Citation2021) who reported that the respondents had an average experience of 11.58 years in grape production. The outcome of educational level of producers presented in Table shows that 18.95% of the producers received no formal education, 29.47%

had up to primary education, 37.37% ended in the JHS, 11.58% ended at SHS and 2.63% completed tertiary education. The results showed that the majority obtained primary education. These results concur with Kulwijira (Citation2021) who revealed that based on the Tanzanian education system, most of the grape farmers and traders had primary education. Abera et al. (Citation2020) reported that 50.50% of the respondents received primary education in their work on assessment of postharvest losses of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum, Mill) in selected districts of East Shewa zone of Ethiopia using a commodity system of analysis methodology. Results from Table show the proportion of respondents’ response to storage facility, available market and longer distance to farm. 3.45% out of the interviewed respondents used storage facilities, 66.5% of the respondents selected longer distance to farm and 85.22% of them had unreliable market. The average quantity of tomatoes harvested in an average of 6 days by a farmer who cultivates on a mean farm size of 1.68 ha is 9763.16 kg. The mean cost of labour computed from the survey for both major and minor seasons is GH₵ 803.16. Average fertilizer cost calculated is GH₵ 698.18, cost of agrochemical is GH₵ 659.89 and the mean cost of transportation is GH₵ 601.71. The average post-harvest loss value is GH₵ 3598.71.

3.2. Conceptual framework

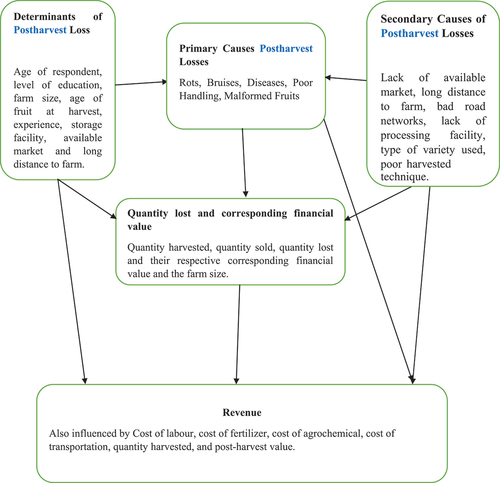

The determinants such as age of respondents, education, farm size, age of fruit at harvest, and experience were hypothesized in this study to exert both positive and negative influences on postharvest loss of tomatoes (Aidoo et al., Citation2014; Arah et al., Citation2015). Other factors include availability of storage facility, available market and long distance to farm (Munhuweyi et al., Citation2016; Sibomana et al., Citation2016) as shown in Figure . The quantitative losses and the corresponding financial value due to losses also considered the quantity harvested, the quantity lost during postharvest, the quantity sold and farm size. The primary causes of postharvest losses in tomato production include rots, bruises, diseases, poor handling and malformed fruits. The secondary causes driving these primary causes were lack of available market, long distance to farm, bad road networks, lack of processing facility, type of variety used and poor handling techniques. The value of postharvest loss was hypothesized to have impacted the revenue of producers (Abera et al., Citation2020; Ali et al., Citation2021; Munhuweyi et al., Citation2016). Other factors that influence revenue include cost of labour, cost of fertilizer, cost of agrochemical, cost of transportation and the quantity harvested (Figure ).

3.3. Analytical framework

Data was analyzed using Descriptive Statistics, Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance, Fractional Response Regression model and Box Cox Regression model. Specifically, descriptive statistics comprising means and summary tables were used to analyze the socioeconomic characteristics and the primary causes of postharvest losses. The economic value of fresh tomato fruits lost was obtained by multiplying the physical quantity of fruits lost by the prevailing market price. A fractional response model was employed to estimate the factors impacting the proportion of income lost owing to postharvest losses; while a Box Cox regression model was employed to analyze the effects of postharvest losses on the income of tomato growers in the research area. In operationalizing the aforementioned method, producers were asked how much tomatoes in terms of boxes were lost during the tomato cropping season. Descriptive statistics and simple arithmetic were used in calculating the quantity of tomatoes lost. The financial value was measured in Ghana cedis. This was achieved by multiplying the physical quantity of tomato lost by the selling price. That is,

where

FV = Financial value of postharvest losses (measured in GH₵)

PHL = Postharvest losses (measured in Kg)

V = Market price (measured in GH₵)

In identifying the causes of such losses, farmers were asked to select from a list of perceived primary and secondary causes. Descriptive statistics were used to identify the primary causes and Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance was used to identify the secondary causes.

The study used the method of Papke and Wooldridge (Citation1996), utilizing a fractional response model to estimate the factors affecting the proportion of income lost owing to postharvest losses as follows:

where is the observed response of share of income lost owing to postharvest losses,

is the expectation operator;

is a vector of the household characteristics;

is a vector of parameters to be estimated; and

is the associated parameter to be estimated. The conclusions above hold true if there is a fractional response with a conditional mean that also happens to have a probit form, according to the literature on quasi-MLE (White, Citation1982 and Wooldridge, Citation2011). The main takeaway from quasi-likelihood estimation is that in order to get reliable parameter estimates, we do not necessarily need to know the real distribution of the entire model. If we model the conditional mean of a probit form, we can also use this probability function in the scenario where there is a fractional response. Because the Bernoulli distribution belongs to the family of linear exponential distributions, despite misspecification in other areas of the distribution, quasi-LIML may identify the parameters in a correctly described conditional mean.

In analyzing the effect of postharvest losses on the income of tomato growers in the research area, Box-Cox regression model was employed. Box-Cox regression model calculates the coefficients on the independent variables, the standard deviation of the normally distributed errors, and the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters of the Box-Cox transformation. Any changed dependent variable or independent variables must strictly be positive. Zarembka was the first to apply the transformation of variables technique to econometrics (1974). He elaborated on the Box and Cox model from 1964 and stated that:

In applied data analysis, Box-Cox, which determines the maximum probability estimates of the Box-Cox transform’s parameters, is frequently employed. The transformation was created by Box and Cox in 1964, who claimed that it might make the residuals more closely normal and less heteroskedastic. In this context, Cook and Weisberg (Citation1982) talk about the transformation as drawing some interest as a tool for evaluating functional forms, in particular because it embeds several well-known functional forms. That is,

Box and Cox (1964) hypothesized that this transformation would result in residuals that more closely resembled those of a normal distribution than those generated by a straightforward linear regression model. Box-Cox regression model calculates the maximum likelihood estimates of the parameters of the Box-Cox transformation and produces maximum probability estimates of the fact that its normality is assumed. That is,

and xi as shown represents the explanatory variables. Since economic theory generally fails to provide economists with useful direction in defining the functional form of an economic relationship, Zarembka (Citation1974) suggests the transformation-of-variables model for determining the appropriate functional form within the context of statistical inference. The transformation aims to approximate compliance with three fundamental requirements of regression models, viz. the existence of an additive error term, the additive error’s constant variance; and (iii) the symmetry, if not near normality, of the error distribution. The traditional normal linear regression can be utilized as a foundation for statistical inference if the outcome variable can be changed to achieve this purpose. Although, the value of the transformation parameter in the leadoff linear model with additive, homoscedastic, and normal errors is unknown, it may be calculated using basic data.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Quantity and financial value of postharvest losses

Table presents a summary on production, quantity of tomato lost, and the financial value of losses during the 2020 cropping season. From the results, the average area of land cultivated was 1.68 hectares during both major and minor seasons. The average quantity of tomato harvested in both the major and minor seasons were 6,625 kg and 3,092 kg, respectively. On average, a 100 kg (box) of tomato was sold for GH₵ 51.61 in the major season and GH₵ 307.70 in the minor season. About 3,821.3 kg of tomatoes were sold in the major season and 2,388.8 kg were sold in the minor season. On average, a tomato farmer made revenue of GH₵1960.80 in the major season and GH₵ 7383.80 in the minor season.

Table 2. Analysis of quantitative losses and financial value of postharvest losses for the 2020 tomato cropping season

The average quantity of tomatoes (kg) that was lost in the major season was 2,803.7 kg with a financial value of GH₵ 1,444.80. This represents 42.4% loss of the harvested produce in the major season. Quantity of tomato lost during the minor season on the average was 703.2 kg with a financial value GH₵ 2153.90, representing 22.6% loss of the harvested produce. These results are in consonance with the study by Kuranen-Joko and Liambee (Citation2017) who found the average postharvest losses in a season to be 41% of the total output. Additionally, Aidoo et al. (Citation2014) also reported in a survey that 40% out of 6,143.46 kg of tomatoes harvested in the major season were lost due to postharvest and 14% out of 4,871.68 kg of tomato harvested were lost in the minor season. However, Anaba (Citation2018) in his study on assessment of postharvest losses along the fresh tomato value chain in the Upper East region of Ghana reported that out of 59,333.32 kg of tomato harvested, only 9.77% were lost in the major season and 12.80% of 81,060.98 kg were lost in the minor season.

The potential revenue that could have been generated in the absence of postharvest losses was estimated to be GH₵ 3405.60 in the major season and GH₵ 9538.70 in the minor season. The difference in the means for major and minor seasons is significant and affects the various stakeholders engaged in tomato production within the area of study. The average variable cost of

production in the growing season is GH₵ 2759.94. This includes the average cost of labour, transportation, agrochemicals and fertilizer (Table ). The total revenue obtained in a cropping season (major and minor) by a tomato producer is GH₵ 9345.60 (Table ). Therefore, a producer after incurring a cost of GH₵ 2759.94 in production gains a gross profit of GH₵ 6585.66.

4.2. Perceived causes of postharvest losses

Table presents the primary causes of postharvest losses. All the respondents (100%) selected rot as one of the primary causes of postharvest losses. About 98.5% of the respondents also selected bruise as a cause. Out of the 203 respondents, 66.5% indicated diseases as a primary cause, 26.6% saw poor handling as a cause of postharvest losses and 54.7% ticked yes to malformed fruits. The farmers reported that, in the major season, fruits tend to rot more than in the minor season because of excessive rains. Our findings were consistent with Amoako-Adusei (Citation2020) and Aidoo et al. (Citation2014).

Table 3. Primary Causes of Postharvest Losses

From the farmers’ point of view, the most critical secondary factors that impacted heavily on postharvest losses in tomato production were lack of available market and longer distance to farm which were ranked as very high. Bad road network was ranked as high, while lack of processing facility and type of variety used were ranked as moderate. Poor handling technique ranked low (Table ). Our findings are consistent with Kikulwe et al. (Citation2018) and Anaba (Citation2018) who revealed that postharvest losses at the farmer level along the tomato value chain resulted largely from mechanical injuries such as rot and bruises.

Table 4. Secondary causes of postharvest losses

4.3. Determinants of postharvest losses

Table presents a summary of the results of the fractional response with quasi maximum likelihood estimates of the determinants of postharvest losses in tomato production. For farmers’ level of education, the coefficient was positive and statistically significant at the 10% level. That is an increase in education will increase the proportion of tomatoes lost by 4.9% the producers even though educational background was hypothesized to have an inverse relationship with the fraction of tomato loss. This might be due to the fact that because educated farmers may be engaged in other off farm activities that may prevent such farmers from having time to harvest and market their produce at the right time. Our finding is consistent with Kuranen-Joko and Liambee (Citation2017) who reported that level of education has a positive influence on the proportion of fruit loss.

Table 5. Fractional response estimates of the determinants of postharvest losses in tomato production

As revealed from the result of this study, unreliable market has a positive relationship with the proportion of postharvest loss and it is statistically significant at the 1% level. This implies that postharvest losses reduce by 2.32% when there is available market for tomatoes. Thus, if tomato producers have access to reliable markets, they are more likely to sell their tomatoes at the right time. This helps tomato farmers reduce excess postharvest losses. The results corroborate with similar findings of Kulwijira (Citation2021) and Aidoo et al. (Citation2014) who found in their respective studies that unreliable market positively influenced tomato losses.

From Table , farm size is statistically significant at the 1% level and has a negative influence on the proportion of postharvest loss. This means that an increase in farm size reduces postharvest losses by 4.2%. Farmers with larger farm sizes tend to have much experience in farming and searching for reliable markets for their produce ahead of production. Hence, they are able to manage postharvest losses. Given the number of resources that would have been injected into managing a large tomato farm, farmers with large farms would have planned for storage and markets for their produce even before the commencement of production and

therefore, will likely not encounter postharvest losses vis-à-vis those with small tomato farms. This finding confirms a similar finding reported by Amoako-Adusei (Citation2020) that the larger the farm size the lower observed postharvest losses in agricultural production.

4.4. Effect of postharvest loss on the revenue of tomato producers

Table presents a summary of the Box-Cox regression estimates for the effects of postharvest losses on the revenue of tomato producers. From Table , the coefficient of transportation cost incurred is negatively related to the revenue obtained at the end of the cropping season and this is statistically significant at the 5% level. This implies that a GH₵ 1 increase in cost of

Table 6. Box-cox regression estimates for the effect of postharvest loss on the revenue of tomato producers

Transportation will decrease the revenue of tomato producers. Quantity harvested is positively related to revenue and is statistically significant at the 1% level. This means that a 1% rise in quantity of tomatoes harvested increases revenue by 42.5%. Even though this result conforms to our a priori expectation, it is contrary to the finding of Alidu et al. (Citation2016) that concluded that quantity harvested had a negative influence on income.

From Table , the value of postharvest loss is negatively related to revenue and statistically significant at the 1% level. This implies that a decrease in the value of postharvest losses will increase revenue of tomato producers by 1.1%. Our finding is consistent with that of Alidu et al. (Citation2016) who reported an inverse relationship between the value of postharvest losses and farm revenue which make tomato producers get less than what they incur in production.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

This study analyzed the value of postharvest losses among smallholder tomato farmers in Ghana. The results of the analysis of the quantitative losses and the corresponding financial value of losses revealed that the quantity of tomatoes harvested in both the major and minor cropping seasons were 6625 kg and 3092 kg, respectively. Out of these harvested quantities, 2803 kg was lost in the major season while the minor season recorded a loss of 703.2 kg. The corresponding values of losses in both seasons were GH₵ 1444.80 and GH₵ 2153.90. From the aforementioned findings, we conclude that farmers lost more tomatoes in the major season than the minor. From the farmers’ perspective, the chief primary cause of postharvest losses of tomato was rot while the most critical secondary factor that impacted heavily on postharvest losses in tomato production was lack of available market. The results from the determinants of postharvest losses indicated that farmers’ level of education and unreliable market were statistically significant and exerted positive influences on the proportion of fruit loss. However, farm size was found to be negatively related to the value of postharvest losses which implies that tomato farmers with large farm sizes will normally encounter fewer postharvest losses since such farmers will normally plan their storage and marketing activities ahead of the commencement of their tomato production. Results from the regression estimates for the effects of postharvest losses on the revenue of tomato producers revealed that whereas the value of postharvest losses and transportation cost had negative relationships with the revenue generated from sales, quantity of tomato harvested exerted a negative effect on revenue.

For policy purposes, the study recommends the need for government and other key stakeholder intervention in the building and provision of storage facilities, good road networks, processing factories in tomato-producing towns, ready markets, as well as dams to help supply water all year round for continuous tomato production. There is also the need for the formation of various cooperative groups to help organize and give training and also assist farmers in dealing with issues of postharvest losses. These will help reduce postharvest losses among the tomato farmers. The study suggests the following for future research in postharvest analysis and most especially in the tomato industry. Firstly, the current study mainly focused on postharvest losses at the farmer level. This does not show the exact quantity of postharvest losses along the value chain. Therefore, the current study suggests that future research should undertake postharvest analysis along the entire economic value chain. Secondly, the current research concentrated on tomatoes. Similar farm-level analysis can be done for other crops, more importantly the perishable vegetables and fruits. Even two or more crops can be included in the study. That is multi-product analysis, which is possible in small-scale crop production.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available by the Corresponding Author on request

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Camillus Abawiera Wongnaa

Dr. Camillus Abawiera Wongnaa Dr. Camillus Abawiera Wongnaa has PhD in Agricultural Economics from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) and currently a Senior lecturer at the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension of the same university. Before joining KNUST in August, 2016, he had worked for five (5) years as a Lecturer and later a Senior Lecturer and a Head of Department of Agropreneurship of Kumasi Technical University, a department he established. Dr. Wongnaa has published over 50 peer reviewed journal articles, two book chapters and an Editorial Board Member of African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics (AfJARE) as well as an Associate Editor of Heliyon-Agriculture, an Elsevier Journal. Camillus has consulted for African Development Bank, Winrock International for Agricultural Development, etc. His research areas are agricultural economics and Agribusiness.

Emmanuel Dapaah Ankomah

Mr. Emmanual Dapaah Ankomah Emmanuel Dapaah Ankomah holds a Bachelor’s degree in Agriculture with specialization in Agricultural Economics from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). He worked as a teaching, research and extension assistant at the Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension of KNUST for the 2021/22 academic year. He assisted and has been acknowledged in many research works in KNUST and abroad.

Temitope Oluwaseun Ojo

Dr. Temitope Oluwaseun Ojo Temitope is an Agricultural Economist, with areas of specialisation in Agricultural Finance and Environmental Economics. His research focus is premised towards planning and implementation of national and local level adaptation programs in account for existing climate change adaptation strategies, climate change financing and CSA practiced by farming households for improved livelihood. He has been involved in a number of funded researches within and outside the University as a research fellow in Consumer Acceptance, Varietal adoption and Profitability Analysis of Investments in Vitamin A Cassava in Nigeria facilitated by IFPRI/Harvest Plus/IITA/OAU. Also, a consultant for the “Survey Monitoring and Implementation of Quality Assurance in the Model Village Qualitative Impact Evaluation Survey on Vitamin A Cassava in Nigeria funded by HarvestPlus; Entrepreneurial risk linked to water quality, water security for urban based farming and agro-processing funded by Water Research Council, South Africa. Temitope has several academic publications indexed in scopus.

Emmanuel Abokyi

Emmanuel Abokyi Dr. Emmanuel Abokyi currently works as a Senior Consultant at the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA). He has hands on experience in econometric modeling as well as analysis of qualitative data. He has great experience in food security issues in Ghana. As a former banker, Emmanuel has a good experience in agricultural finance and credit analysis. He developed and trained several Farmer Based Organizations (FBOs) under the MiDA Credit Facility. He also has expertise in Project Planning, Implementation and Management, Monitoring and Evaluation, Gender Assessment, Baseline Survey, etc. He has developed several survey instruments for many studies and has very good data collection skills.

Gifty Sienso

Dr. Gifty Sienso Dr. Gifty Sienso currently works at the Department of Applied Economics, School of Management Sciences, University for Development Studies. Gifty does research in Resource Economics, Nutrition Economics, Agricultural Economics and Gender and Development.

Dadson Awunyo-Vitor

Prof. Dadson Awunyo-Vitor Prof. Dadson Awunyo-Vitor is a Fellow of Association of Chartered Certified Accountant (ACCA), UK and a member of Institute of Chartered Accountant (ICA) Ghana, Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) and Chartered Institute of Taxation (CIT) Ghana. Dadson obtained PhD in Agricultural Economics from the University of Ghana. He is a graduate of Imperial College, University of London, where he studied for MSc Agricultural Economics. He is currently the head of Department of Agricultural Economics, Agribusiness and Extension of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

References

- Abera, G., Ibrahim, A. M., Forsido, S. F., & Kuyu, C. G. (2020). Assessment on post-harvest losses of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentem Mill.) in selected districts of East Shewa Zone of Ethiopia using a commodity system analysis methodology. Heliyon, 6(4), e03749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03749

- Adams, F., Wongnaa, C. A., & Coleman, E. (2021). 'Profitability and choice of marketing outlets: Evidence from Ghana's tomato production'. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 11(3), 296–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-06-2019-0090

- Aidoo, R. A, Danfoku, R., & Mensah, J. O. (2014). Determinants of postharvest losses in tomato production in the Offinso North district of Ghana. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(8), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.5897/jdae2013.0545.

- Alidu, A. -F., Baba Ali, E., & Aminu, H. (2016). Determinants of post harvest losses among tomato farmers in the navrongo municipality in the upper East region. Journal of Biology, 6(12), 14–20.

- Ali, A., Xia, C., Faisal, I., Mahmood, M., & Faisal, M. (2021). Economic and environmental consequences’ of postharvest loss across food supply Chain in the developing countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 323, 129146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129146

- Al-Zabir, A., Wongnaa, C. A., Islam, M. A., & Mozahid, M. N. (2020). Food security status of farming households in Bangladesh: A comparison of recipients and non-receivers of institutional support. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 1–14.

- Amartey, J. N. A. (2013). Estimation of postharvest losses and analysis of insecticide residues in some selected vegetable crops in the greater accra region of Ghana(Doctoral dissertation. University of Ghana.

- Amicarelli, V., & Bux, C. (2020). Food waste measurement toward a fair, healthy and environmental-friendly food system: A critical review. British Food Journal, 123(8), 2907–2935. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2020-0658

- Amoako-Adusei, R. (2020). Tomato Postharvest Losses in Ghana : An Economic Analysis Tomato Postharvest Losses in Ghana : An Economic Analysis. Unpublished Undergraduate thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

- Anaba, G. (2018). Assessment of postharvest losses along the fresh tomato value chain in the upper East region of Ghana.

- Arah, I. K., Amaglo, H., Kumah, E. K., & Ofori, H. (2015). Preharvest and postharvest factors affecting the quality and shelf life of harvested tomatoes: A mini review. International Journal of Agronomy, 2015, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/478041

- Atanda, S. A., Pessu, P. O., Agoda, S., Isong, I. U., & Ikotun, I. (2011). The concepts and problems of post-harvest food losses in perishable crops. African Journal of Food Science, 5(11), 603–613.

- Cook, R. D., & Weisberg, S. (1982). Residuals and influence in regression. Chapman and Hall.

- FAO. (2011). Global food losses and food waste - Extent, causes and prevention. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- FAO. (2018). Guidelines on the measurement of harvest and post-harvest losses Guidelines on the measurement of harvest and post-harvest losses. A technical handbook (p. 137).

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). (2019). FAOSTAT - The Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database website. FAO. http://www.Fao.org/faostat/en/#home.

- Ganiu, I. (2019). Analysis of Marketing Channels, Gross Margin and Postharvest Losses of Smallholder Irrigated Tomato Farming in Kassena-Nankana Municipality. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Ghana

- GNA. (2017). Post-harvest losses major cause of poverty, food insecurity. A research article. https://www.modernghana.com/news/812633/: Accessed 2021

- Gonzalez, Y. S., Dijkxhoorn, Y., Elings, A., Glover-Tay, J., Koomen, I., van der Maden, E. C. L. J., & Obeng, P. (2014). Vegetables Business Opportunities in Ghana: 2014.

- Horna, J. D., Timpo, S. E., Al-Hassan, R. M., Smale, M., & Falck-Zepeda, J. B. (2008). Vegetable Production and Pesticide Use in Ghana: Would GM Varieties Have an Impact at the Farm Level?. No. 307-2016-4931.

- Kader, A. A. (2005). Increasing food availability by reducing post-harvest losses of produce. Acta Horticulturae (ISHS), 682(682), 2169–2176. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2005.682.296

- Kiaya, V. (2014). Post-harvest losses and strategies to reduce them. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 149(3–4), 49–57. http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract

- Kikulwe, E. M., Okurut, S., Ajambo, S., Nowakunda, K., Stoian, D., & Naziri, D. (2018). Postharvest losses and their determinants: A challenge to creating a sustainable cooking banana value chain in Uganda. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(7), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072381

- Kitinoja, L., & Cantwell, M. (2010). Identification of Appropriate Post Harvest Technologies for Improving Market Access and Income for Small Horticultural farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. World Food Logistics Organization. 321.

- Kulwijira, M. (2021). Socio-economic determinants of post-harvest losses in the grape value chain in dodoma municipality and chamwino district, Tanzania. African Journal of Economic Review, 7(Ii), 295–301.

- Kuranen-Joko, D. N., & Liambee, D. H. (2017). Determinants of postharvest losses among tomato farmers in gboko local government area of Benue State. CARD International Journal of Agricultural Research and Food Production (IJARFP), 2(4), 27–33.

- Mebratie, M. A., Haji, J., Woldetsadik, K., & Ayalew, A. (2015). Determinants of post-harvest banana loss in the marketing chain of central Ethiopia. Journal of Food Science and Quality Management, 37, 53–63.

- Melomey, L. D., Danquah, A., Offei, S. K., Ofori, K., Danquah, E., & Osei, M. (2019). Review on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, L.) improvement programmes in Ghana. Recent Advances in Tomato Breeding and Production, 49.

- MoFA. (2011). Annual report for offinso district, Ministry of Food and Agrculture,

- MoFA. (2019). Ministry of Food and Agriculture: Programme Based Budget Estimates. www.mofep.gov.gh

- MoFA. (2022). Annual report for offinso district, Ministry of Food and Agrculture,

- MoFA (Ministry of Food and Agriculture). (2020). Annual crop estimates. Statistics, Research, and Information Directorate of Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Accra, Ghana.

- Munhuweyi, K., Opara, U. L., & Sigge, G. (2016). Postharvest losses of cabbages from retail to consumer and the socio-economic and environmental impacts. British Food Journal, 118(2), 286–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2014-0280

- Odeyemi, O. M., Kitinoja, L., Dubey, N., Musanase, S., & Gill, G. S. (2021). Preliminary study on improved postharvest practices for tomato loss reduction in Nigeria, Rwanda and India. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 1-6(6), 1500–1505. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2021.1961986

- Papke, L. E., & Wooldridge, J. M. (1996). Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (k) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(6), 619–632.

- Pathare, P. B., Al Dairi, M., & Al-Mahdouri, A. (2021). Effect of storage conditions on postharvest quality of tomatoes: A case study at market-level. Journal of Agricultural and Marine Sciences [JAMS], 20(6), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2021.05.001

- Robinson, E. J., & Kolavalli, S. L. (2010a). The Case of Tomato in Ghana. In Processing (pp. 1–20). Ghana: International Food Program (IFP), Accra.

- Robinson, E. J. Z., & Kolavalli, S. L. (2010b). The Case of Tomato in Ghana: Processing Ghana Strategy Support Program (GSSP) Working Paper No. 21.

- Robinson, E. J., & Kolavalli, S. L. (2010c). The case of tomato in Ghana: Productivity (No. 19). International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Washington, DC, USA.

- Sibomana, M. S., Workneh, T. S., & Audain, K. (2016). A review of postharvest handling and losses in the fresh tomato supply chain: A focus on Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Security, 8(2), 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-016-0562-1

- Tsakpoe, S. (2019). Socioeconomic analyses of vegetable production and marketing in Tamale. Northern Region, 8(5), 55. www.udsspace.uds.edu.gh/

- Van Asselt, J., Masias, I., & Kolavalli, S. (2018). Competitiveness of the Ghanaian vegetable sector: Findings from a farmer survey. GSSP Working Paper 47, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- van Dam, B., Goffau, M. D., van Lidt, D. J. J., & Naika, S. (2005). Hb zoeterwoude [beta23(b5)val-->ala)]: A new beta-globin variant found in association with erythrocytosis. Hemoglobin, 29(1), 11–17.

- Verploegen, E., Sharma, M., Ekka, R., & Gill, G. (2021). Low-cost cooling technology to reduce postharvest losses in horticulture sectors of rwanda and burkina faso. In Vijay, Y. T. & Majeed, M. (Eds.),Cold chain management for the fresh produce industry in the developing world (pp. 183–210). CRC Press.

- White, H. (1982). Maximum likelihood estimation of misspecified models. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 1–25.

- Woldu, Z., Ibrahim, A. M., Belew, D., Shumeta, Z., & Bekele, A. (2015). Assessment of banana postharvest handling practices and losses in Ethiopia assessment of banana postharvest handling practices and Losses in Ethiopia. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 5(October 2016), 82–97. https://bris.on.worldcat.org/atoztitles/link

- Wongnaa, C. A., Mensah, S. O., Ayogyam, A., Asare-Kyire, L., & Seyram Anthony, Z. K. (2014). Economics of tomato marketing in ashanti region, Ghana. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 26(2), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.18551/rjoas.2014-02.01

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2011, July). Fractional response models with endogeneous explanatory variables and heterogeneity. In CHI11 Stata Conference (No. 12). Stata Users Group.

- World Bank, FAO and NRI. (2011). Missing food: The case of post-harvest grain losses in SubSaharan Africa. In: Economic Sector Work Report No. 60371-AFR. World Bank, http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgiT=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=caba6&AN=20153367926https://bris.on.worldcat.org/atoztitles/link

- Yeboah, R. (2011). Assessment of donor funds management: A case study of the Asunafo South District Assembly. Doctoral dissertation. Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

- Yusufe, M., Mohammed, A., & Satheesh, N. (2017). Effect of Duration and Drying Temperature on Characteristics of Dried Tomato (L.) Cochoro Variety. Acta Universitatis Cibiniensis. Series E: Food Technology, 21, 41–50.

- Zarembka, P. (1974). Transformation of variables in economics. Frontiers in econometrics, 81–104.

- Zu, K. S. A., Wongnaa, C. A., & Appiah, F. (2014). Vegetable Handling, Distribution, and Wholesale Profitability in “Abinchi” Night Market, Kumasi-Ghana. Journal of Postharvest Technology, 02(01), 096–106.