Abstract

Health and nutrition service for adolescents, will serve as a future investment for breaking the cycle of intergenerational poor health. Thus, understanding barriers and facilitators for nutrition service utilization is critical to timely address malnutrition problem in this age group. This study was conducted in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Ethiopia. A qualitative study was conducted from April 30/2019 to May 30/2019. Purposively selected health extension workers, school leaders, gender focal persons, health center experts, and youth center leaders from each village were involved in this study as key informants. In addition to this, a total of 6 FGDs were conducted. Eight adolescent girls were included in each focus group discussion. The process of analysis was conducted with open coding, identifying concepts, categories and properties/subcategories. The study was approved by Addis Ababa University (AAU), College of Natural Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee. Official letter of cooperation was written to Wolaita and Hadiya zones, and districts of health offices. The nature of the study was fully explained to the study participants. Informed verbal and written consent was obtained from each participant. The collected data has been kept confidential. Barriers for nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls were lack of awareness for study participants and their families, shortage of iron-folate and deworming tablets, lack of trained experts who were responsible for the nutrition service implementation, low economic status of the family, lack of coordination among different sectors for nutrition service, low educational status of the adolescent girls’ family. Facilitators for nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study area were supplementation of iron-folate and deworming tablets was without payment. In addition, the utilization of social and community networks motivates the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls. Recommendation: Awareness creation training should be given for adolescent girls and their families, and male adolescent before the implementation of nutrition service provision.

1. Background

Investment on adolescent girls is very important to break the cycle of intergenerational malnutrition. Promoting health and nutrition services of adolescent girls and protecting young people from health risks is critical to the future of countries’ health and social infrastructure (Nandan et al., Citation2007). Because adolescent health and nutrition service has an intergenerational effect, hence it is one of the important stages of the life cycle in terms of health interventions. Nutrition intervention during adolescence has a positive outcome for future generations and improves the life of society (Staff, Citation2011). The adverse effect of malnutrition during this period can persist into adulthood and influence future health. Thus, adolescence is a life-stage offering significant potential for shaping the trans-generational effects of nutrition through the prevention of non-communicable diseases (Todd et al., Citation2015).

Nutrition service utilization effectiveness is often limited because of low adherence by the target population. The reasons for noncompliance were inadequate program support, insufficient delivery of services and patient factors (Rosenberg et al., Citation1995). In the case of iron supplementation, low adherence was due to the unavailability of the tablets was the most common reason that participants did not take iron—folate supplements (Galloway & McGuire, Citation1994). Lack of nutrition communication efforts must be solved to increase understanding of the importance of taking supplements and to address any fears or misconceptions related to supplementation (Zoellner et al., Citation2009).

Nutrition services in high-income countries, as well as low- and middle-income countries that targeting adolescents, are highly fragmented, poorly coordinated, and uneven in quality (Chatterjee & Baltag, Citation2015;Otekunrin et al., Citation2022). In addition to these, health expertise faces several challenges with adolescents as they require specialized skills for consultation, interpersonal communication, and interdisciplinary care (Salam et al., Citation2016). Study at Peru indicated that barriers for nutrition service are inadequate program support such as lack of political commitment and financial support, insufficient delivery of services such as lack of supplies, access, training, and motivation of health-care professionals, and participants’ factors such as misunderstanding of instructions and adverse side effects (Gross et al., Citation2006).

Understanding prevailing adolescent nutrition problems and their consequences, the Ethiopian government considered adolescence as a second window of opportunity in the life cycle approach for addressing nutrition problems (Kennedy et al., Citation2015). Even though recently increased interest in adolescent nutrition has been shown as reflected by the inclusion of the term adolescent nutrition in the sustainable development goals (SDGs), there is no information on barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization of adolescent girls (Klapper et al., Citation2016). Similarly, government of Ethiopia officially launched the National Nutrition Program (NNP) in 2009, which aimed to reduce all forms of malnutrition in Ethiopia by integrating adolescents’ nutrition into community-based health and development programs but faced a number of challenges. The Ethiopian national nutrition program II (2016–2020) incorporated initiatives to improve the nutritional status of adolescent girls (Bekele et al., Citation2008). But a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in the northwestern part of the Amhara region of Ethiopia indicated that only 52.7% of adolescent girls are using community-based nutrition services (Wassie et al., Citation2015).

A good understanding of barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls will have many important public health and policy implications to shape and consolidate healthy eating and lifestyle behaviors, thereby preventing or postponing the onset of nutrition-related chronic disease in adulthood (Melaku et al., Citation2015). There was no study documented in the study area regarding barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls. Therefore, this study will fill the information gap on barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in Wolaita and Hadiya zones. The results of this study will give information to community health workers, ministry of health, ministry of agriculture and non-governmental organizations that are interested in the safe and effective implementation of nutrition programs to improve the nutritional status of adolescent girls. The findings can be used to improve existing policies and programs targeting adolescent girls’ nutrition, particularly the prevention and management of stunting and underweight in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, southern Ethiopia.

Thus, understanding barriers and facilitators for nutrition service utilization is critical to timely address malnutrition problem in this age group. The objective of the study was to explore barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, Southern Ethiopia.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study area and period

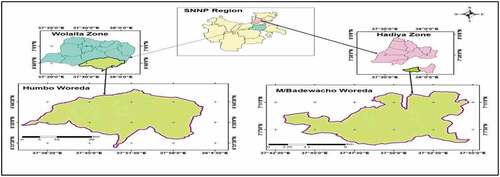

A qualitative cross-sectional study was conducted in Wolaita and Hadiya zones, southern Ethiopia. These zones are predominantly dependent on agriculture, practicing mixed crop-livestock production and living in permanent settlements. Within their landholdings, community members cultivate fruits, vegetables, roots, and tuber crops. The study period was from April 30/2019 to May 30/2019

2.2. Participants

Purposively selected health extension workers, school leaders, gender focal persons, health center expert and youth center leaders from each kebele were involved in this study as key informants. In addition to this, a total of 6 FGDs were also conducted where comprising eight adolescent girls in each group.

2.3. Data collection

Key informant interview (KII) – health extension workers, school leader and gender focal person, health center expert and youth center leader have participated from each kebele. In total, health extension workers (6), primary or secondary school leader (6), gender focal person (2), health center expert (2) and youth center leader (2) were involved for key informant interviews (KIIs). Similarly, for focus group discussion, eight adolescent girls in one group have participated in each kebeles. A total of 6 FGDs were conducted from the two districts. Both FGDs and KIIs were used to triangulate individual and group-level opinions. The KIIs were conducted in an interactive manner, whereby the study participants were encouraged to take an active role in establishing the flow of the interview. FGDs and KIIs were held at the community or nearby health posts or health centers. Qualitative data from FGDS were collected by data collectors who have experience in qualitative data collection procedures. Qualitative data collection key informant interview (KII) was conducted by the participial investigator. All interviews were tape-recorded. Open-ended questions were used to collect relevant information.

2.4. Data analysis

Each audiotape interview was professionally transcribed word by word in wolaitegna and Hadyagna (local language) and then translated to English. The lead author coded all the transcripts followed by conventional content analysis procedure by starting coding categories which derived directly from the text data. The process of analysis was conducted with open coding, identifying concepts, categories, and subcategories. After aggregating and defining concept lead author developed memos that can elaborate on the concepts/categories developed. Finally, the integration of categories was done which was linking categories around a core category. Data were analyzed by using “Open code software.”

2.5. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Addis Ababa University (AAU), College of Natural Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee. Official letter of cooperation was written to Wolaita and Hadiya zones, and districts of health offices. The nature of the study was fully explained to the study participants. Informed verbal and written consent was obtained from each participant. The collected data has been kept confidential.

3. Results of the study

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of qualitative study participants in southern Ethiopia

The study was conducted among 18 KIIs and eight FGDs in two districts of southern Ethiopia. As indicated in Table , Twelve of the key informants were female and six were male. The participants represented a wide age range (24–36 years).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of qualitative study participants in southern Ethiopia, 2019

3.2. Nutrition service provided/implemented in the study area

Nutrition services that were given for the adolescent girls in the study area were weekly iron-folic acid supplementation, school-based nutrition education and deworming tablet supplementation every six months. In addition to this, community-based nutrition education was given for adolescent girls in the study area. This indicated in Table with thematic categories. Iron folic acid supplementation was supported by the Wolaita Kalehiwot Terpeza development association, which supports only the targeted area of Wolaita zone. This supplementation process does not include the Hadiya zone where our study includes. In both zones, school-based deworming tablet supplementation takes place every six months. Deworming tablet was freely supplied by the ministry of health for schooling adolescent girls. Community and school-based nutrition educations were given for adolescent girls in both zones. Health extension workers, woredas health experts, and school teachers were giving nutrition education during outreach programs, at school during orientation time, community mobilization and house to house visits by health extension workers. All nutrition services except community-based nutrition education, provided/implemented at schools. Iron-folate supplementation and deworming tablet were only given for schooling adolescent girls. This indicates that adolescent girls who have no chance to go to school cannot get full nutrition service.

Table 2. Thematic categories with themes, representative quotes from a qualitative study on barriers and facilitators for nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in southern Ethiopia, 2019

3.3. Barriers for nutrition service utilization of adolescent girls in the study area

Barriers for nutrition service utilization of adolescent girls in the study area were lack of awareness of study participants and their families, shortage of IFA and deworming tablets, lack of diagnosing service for anemia and intestinal parasites, lack of coordination among different sectors, low educational status of participant families, low commitments of health extension workers to visit each households and low economic status of the families to implement the knowledge of nutrition education.

When iron-folic acid supplementation was given for adolescent girls, participant’s families were considering the supplementation of iron-folate as a contraceptive method. This affects the utilization of iron-folic acid among adolescent girls in the study area. Similarly, the supplementation of deworming tablets for adolescent girls was considered as the tablet which causes adolescent girls sterile.

we feel fear to take iron-folate and deworming table when our family says as it is contraceptive method because awareness creation training was not given for our family so that they are not volunteering for utilization of iron-folic acid tablet.

14-year-old adolescent girl from shochora ogodama kebele

we were asked many times by participants’ families as iron-folic acid and deworming tablets affect the reproduction of adolescent girls in the future.

32-year-old health extension worker from Kanchera kebele

Shortage of iron-folate, deworming tablets and less coverage of nutrition service supplementation were barriers for utilization of nutrition service among adolescent girls in the study area. The supply of iron-folate and deworming tablets was not enough with the demand of the adolescent girls. In addition to this, supplementation was school-based. So that adolescent girls who were not at school cannot get any supplementation. The school-based nutrition education and supplementation program cannot reach out-of-school adolescent girls.

we supplement iron-folate and deworming table for only schooling adolescent girls at school. Supplements were not enough to supply at the community level for all adolescents girls.

34-year-old health extension worker from Ampo koysha kebele

Lack of diagnosis service for specific nutrient and deficiency diseases among adolescent girls was the barrier to the utilization of nutrition. In the study area, supplementation of iron-folic was implemented without the diagnosis of blood hemoglobin level for iron and folate status. Without the knowledge of blood nutrient status level, participants were not interested to take supplementation. Similarly, supplementation of a deworming tablet was implemented without the diagnosis of a gut parasitic load. So the universal supplementation of a deworming tablet was not effective due to the interest of participants was low.

we supplement iron-folate and deworming tablet for adolescent girls without a diagnosis for specific nutrient and deficiency diseases. We supplement as told from the district health office without knowing the status of adolescent girls.

32-year-old health expert from Humbo woreda health center

Lack of trained experts who were responsible for the nutrition service implementation was the barrier to the utilization of nutrition service. There were no responsible experts for the supplementation of iron-folic acid and deworming tablets in the study area for adolescent girls. Health experts and health extension workers were implementing the supplementation process with other duets without getting enough training. Sometimes school teachers were directly involving in supplementation of tablets and this was affected by class schedules. In addition to this, when students were on semester break or at the end of the class, there was no supplementation program. Some teachers were not volunteers for the supplementation of any tablets.

We did not get enough training for supplementation of an iron-folate and deworming tablets for adolescent girls. In addition to this, we did not get training for nutrition education to give nutrition education services for adolescent girls. Sometimes we are too busy to supplement tablets 28-year-old female school director from Humbo woreda

The low economic status of the family affects nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study area. When nutrition education was given to adolescent girls, the utilization of nutrition education was high among adolescent girls who were from economically well family. From FGDs most adolescent girls have reported that taking nutrition education to eat a diversified diet was not important without having enough food and food choice. Similarly, adolescent girls who were from economically well family can attend school and can get nutrition services that were given only at school. Participation in the nutrition education sessions itself as well as practicing what has been thought by nutrition education can be affected. So that, economical status of the adolescent girls’ families was barriers to nutrition service utilization.

we (adolescent girls) eat what we get at home. We eat kita, injera, Shiro, potato, kale, etc. Even if health extension workers and health experts give nutrition education to eat fruits and vegetables as well as different foods groups, this does not work for adolescent girls who were from poor households … a poor household cannot implement the knowledge of nutrition education … .sometimes we were not attending nutrition education session as it was not important for us.

16-year-old adolescent girl from woyira mazoriya kebele

Most of the adolescent girls were not volunteer to participate in nutrition education sessions by reporting as “we don’t have different food to eat at home to choose.” We have asked them what types of food they were frequently consuming.

30-year-old health extension worker from Shochora Ogodama kebele

Lack of coordination among different sectors for nutrition service was a barrier for nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study area. Health sector experts were implanting nutrition services for adolescent girls at school and community level. During the implementation of nutrition service at the school level, many teachers and school directors were not effectively supporting the implementation process. They were not considering themselves as responsible for the provision of nutrition service. In addition to this agricultural extension, workers were not supporting nutrition work.

We(health extension workers) implement nutrition service without enough support from another sector. Teachers, school directors, and agricultural extension workers were not effectively supporting the implementation process.

30-year-old health extension worker from Ampo koysha Kebele, Humbo woreda

Lack of commitment to health extension workers and health experts was a barrier to the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls in the study area. Some of the health experts are not giving attention to nutrition service provision.

Health extension workers were not visiting every household frequently and not giving nutrition education at the community level. Health extension workers and health experts did not give attention to visit all households that have adolescent girls at the community level. Most of the time they waste their time at their office and sometimes at school.

15 years old adolescent girl from Kanchera kebele, Misrak badawacho worada

The low educational status of the adolescent girls’ family was barriers to the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls in the study area. Uneducated families were not volunteers enough for the utilization of the nutrition service of their adolescent girls.

Uneducated and less educated families were not permitting their adolescent girls for the utilization of nutrition service. They deny permission to their adolescent girls for the utilization of iron-folate and deworming tablet supplements.

32-year-old health extension worker from Ampo koysha Kebele, Humbo woreda

3.4. Facilitator for nutrition service in the study area

Supplementation of iron folate without payment facilitates nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls. Similarly, deworming tablet supplementation was implemented without payments for adolescent girls to encourage the utilization of nutrition services. In addition to this, utilization of social and community networks motivates the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls. Problem-solving approach and active participation of adolescent girls to implement nutrition services among adolescent girls facilitate the utilization process. If there was any problem during nutrition service provision, there was a bidirectional discussion among facilitators, adolescent girls and family to solve the problem.

Supplementation of iron folate and deworming tablet without payment facilitates nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls.

Health extension workers and health experts from all kebele and health centers

health extension workers were not asking payment for supplementation of iron folate and deworming tablet. This encourages us to take supplementation every time.

adolescent girls from all kebeles

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers for nutrition service utilization of adolescent girls in the study area

The present KIIs and FGDs conducted in two zones have identified barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in southern Ethiopia. Barriers to nutrition service utilization of adolescent girls in the study area were lack of awareness of study participants and their families about nutrition service. This finding is in line with the studies conducted in India and Bangladesh among adolescent girls which indicated that awareness creation increases nutrition service utilization (Alam et al., Citation2010;Bhatt et al., Citation2011;Singh, Citation2013). This might be due to awareness creation about the importance of nutrition service improves the utilization status of nutrition service among adolescent girls. The adolescent girls and the family who have awareness about the importance of nutrition service have used nutrition service more effectively (Canavan & Fawzi, Citation2019). Similarly, a study conducted among Latino adolescent girls indicated that misunderstanding of nutrition service for adolescent girls affects nutrition service utilization (Beck et al., Citation2019).

Sometimes a shortage of iron-folate and deworming tablets were barriers for full utilization of nutrition services. Iron-folate and deworming tablet supplementation was implemented only school community. So that adolescent girls who were out of school were not using this supplementation. In addition to this sometimes Iron-folate and deworming tablets were not enough for all adolescent girls in the school. This was due to the supplementation of tablets from stockholders was not proportional to the number of adolescent girls in the area. Similarly, the lack of diagnosis service for specific nutrient and deficiency diseases among adolescent girls was the barrier to the utilization of nutrition. Adolescent girls were supplemented with the iron-folic acid tablet without a diagnosis for blood iron level and hemoglobin status. Similarly, adolescent girls supplemented deworming tablets without a diagnosis for a gut parasitic load. Lack of knowledge for specific nutrient deficiency and gut parasite/microbial load was a barrier to the utilization of supplements. Studies conducted in the deferent area indicated that diagnosis for a microbial load is very important for effective prevention and utilization of deworming tablets (Albonico et al., Citation2006).

Lack of trained experts who were responsible for the nutrition service implementation was the barrier to the utilization of nutrition service. Health extension workers expend their time on other health packages other than nutrition service provision. Guidelines for adolescent preventive services written by the World Health Organization recommend that health and nutrition work and service provision should be implemented by trained experts (WHO, Citation2017). Lack of trained nutrition experts might lead to low nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study area. A study conducted in Nigeria recommended that nutrition education should be intensified among female adolescents to improve their nutritional knowledge and to make them realize the importance of choosing healthy food for healthy living (Olumakaiye, Citation2013).

The low economic status of the family was the barrier to nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study areas. When nutrition education was given for adolescent girls, the utilization of nutrition education was high among adolescent girls who were from economically well family. The study conducted in rural Vietnam indicated that individuals from better economic status were using health and nutrition services more than that of low economic status (Thoa et al., Citation2013). Increases in the cost of food lead to changes in the quantity and type of foods that are purchased. This may result in a reduction in the amounts of foods consumed and the substitution of higher-priced foods for less expensive foods which are often less nutritious. Therefore, educating poor adolescent girls to eat healthy and diversified food does not work (Darmon & Drewnowski, Citation2015;Endevelt et al., Citation2009). This might be due to the availability and accessibility of quality food and food groups affect the utilization of nutrition service among adolescent girls.

Lack of coordination among different sectors for nutrition service was a barrier for nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study area. Health extension workers were providing nutrition services without full support from agricultural and school leaders in the study area. Formative research conducted by Ethiopian public health institution indicated that lack of coordination among different sectors was barriers for nutrition service and program provision (Ayana et al., Citation2017).

The low educational status of the adolescent girls’ family was barriers to the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls in the study area. Low/not educated families were preventing their adolescent girls from nutrition service utilization. Low educated families did not volunteer for their adolescent girls to take nutrition education, iron-folate and deworming tablet supplementation. A review of the deferent study conducted in Selected South-East Asian countries indicated that the educational status of the family affects nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls (WHO, Citation2006).

4.2. Facilitators for nutrition service utilization of adolescent girls in the study area

Supplementation of iron folate and deworming tablet supplementation was implemented without payments for adolescent girls to encourage the utilization of nutrition services. In addition, the utilization of social and community networks motivates the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls. Problem-solving approach and active participation of adolescent girls to implement nutrition services among adolescent girls facilitate the utilization process. If there was any problem during nutrition service provision, there was a bidirectional discussion among facilitators, adolescent girls and family to solve the problem. The availability of drinking water in the community and school compound was a facilitator for the utilization of iron folate and deworming tablet supplementation. Adolescent girls swallow supplemented iron folate and deworming tablets during supplementation by using potable water in the study area.

4.2.1. limitations of the study

Potential effort applied to minimize recall bias may be exposed potentially for nutrition services recall bias and social desirability bias.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

Barriers for nutrition service utilization among were lack of awareness for study participants, family and male adolescents, shortage of iron-folate and deworming tablets, lack of trained experts who were responsible for the nutrition service implementation, low economic status of the family, lack of coordination among different sectors for nutrition service, low educational status of the adolescent girls’ family. Facilitators for nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls in the study area were supplemented and were free from payment. Supplementation of iron folate and the deworming tablet was implemented without payments from adolescent girls to encourage the utilization of nutrition service. In addition to this utilization of community, networks motivate the utilization of nutrition services among adolescent girls. Problem-solving approach and active participation of adolescent girls to implement nutrition services among adolescent girls facilitate the utilization process.

Awareness creation training should be given for adolescent girls and their families, and male adolescent before the implementation of nutrition service provision

Nutrition training should be given for health extension workers, health experts, school directors, agricultural extension workers, and other stockholders experts about nutrition service

Different sectors and stockholders should be coordinated to implement nutrition service for adolescent girls

Trained nutrition experts who are responsible for the nutrition service implementation should be recruited at each kebeles

The economic status of the family should be improved by participating in poor households in income-generating activities

Iron-folate and deworming tablet supplementation should be proportional to the number of adolescent girls in each kebele to cover supplementation for adolescent girls at school and community level.

Supplementation program of an iron-folate and deworming tablet should be both school and community level to address all adolescent girls

Further mixed study design should be conducted in the area to identify the barriers and facilitators of nutrition service utilization among adolescent girls

Acknowledgments

Above all, I want to express my heartfelt thanks to the Almighty God, who helped me to accomplish this work and provides His blessing for me throughout my life. I acknowledge the Wolaita and Hadiya zones health office leaders and experts for their valuable cooperation during data collection and I would like to extend my gratitude to all the data collectors who participated in this research and adolescent girls who were willing to participate in this study. I am also grateful to the center of Food Science and Nutrition, Addis Ababa and Tufts University for facilitation and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information file. English Version Questionnaire and information sheet.docx

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam, N., Roy, S. K., Ahmed, T., & Ahmed, A. S. (2010). Nutritional status, dietary intake, and relevant knowledge of adolescent girls in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 28(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v28i1.4527

- Albonico, M., Montresor, A., Crompton, D., & Savioli, L. (2006). Intervention for the control of soil-transmitted helminthiasis in the community. Advances in Parasitology, 61, 311–12.

- Ayana, G., Hailu, T., Kuche, D., Abera, A., Eshetu, S., Petros, A., Salasibew, M. M. … Salasibew, M. M. (2017). Linkages between health and agriculture sectors in Ethiopia: A formative research study exploring barriers, facilitators and opportunities for local level coordination to deliver nutritional programmes and services. BMC Nutrition, 3(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-017-0189-4

- Beck, A. L., Iturralde, E., Haya-Fisher, J., Kim, S., Keeton, V., & Fernandez, A. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating among low-income Latino adolescents. Appetite, 138, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.04.004

- Bekele, A., Kefale, M., & Tadesse, M. (2008). Preliminary assessment of the implementation of the health services extension program: The case of southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev, 22(3), 302–305.

- Bhatt, R. J., Mehta, H. K., Khatri, V., Chhaya, J., Rahul, K., & Patel, P. (2011). A study of access and compliance of iron and folic acid tablets for prevention and cure of anaemia among adolescent age group females in Ahmedabad district of India surveyed under multi indicator cluster survey. Glob J Med Public Health, 2, 1–6.

- Canavan, C. R., & Fawzi, W. W. (2019). Addressing knowledge gaps in adolescent nutrition: Toward advancing public health and sustainable development. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(7), nzz062. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzz062

- Chatterjee, S., & Baltag, V. (2015). Global standards for quality health care services for adolescents. A guide to implement a standards-driven approach to improve the quality of health-care services for adolescents (Vol. 1). Standards and criteria.

- Darmon, N., & Drewnowski, A. (2015). Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv027

- Endevelt, R., Baron-Epel, O., Karpati, T., & Heymann, A. D. (2009). Does low socioeconomic status affect use of nutritional services by pre-diabetes patients? International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 22(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526860910944647

- Galloway, R., & McGuire, J. (1994). Determinants of compliance with iron supplementation: Supplies, side effects, or psychology? Social Science & Medicine, 39(3), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90135-X

- Gross, U., Valle, C., & Diaz, M. M. (2006). Effectiveness of distribution of multimicronutrient supplements in children and in women and adolescent girls of childbearing age in Chiclayo, Peru. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 27(4_suppl4), S122–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/15648265060274S403

- Kennedy, E., Tessema, M., Hailu, T., Zerfu, D., Belay, A., Ayana, G., Samuel, A. … Samuel, A. (2015). Multisector nutrition program governance and implementation in Ethiopia: Opportunities and challenges. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36(4), 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572115611768

- Klapper, L., El-Zoghbi, M., & Hess, J. (2016). Achieving the sustainable development goals. The Role of Financial Inclusion, 23(5), 2016 Accessed, Available online:. http://www.ccgap.org

- Melaku, Y. A., Zello, G. A., Gill, T. K., Adams, R. J., & Shi, Z. J. A. O. P. H. (2015). Prevalence and factors associated with stunting and thinness among adolescent students in Northern Ethiopia: A comparison to World Health Organization standards. Archives of Public Health, 73(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-015-0093-9

- Nandan, D., Nair, K., & Datta, U. (2007). Human resources for public health in India—issues and challenges. Health and Population; Perspectives and Issues, 30(4), 230–242.

- Olumakaiye, M. F. (2013). Adolescent girls with low dietary diversity score are predisposed to iron deficiency in southwestern Nigeria. ICAN: Infant, Child & Adolescent Nutrition, 5(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941406413475661

- Otekunrin, O. A., Science, F., J, N., & Otekunrin, O. A. (2022). Exploring dietary diversity, nutritional status of adolescents among farm households in Nigeria: Do higher commercialization levels translate to better nutrition? Nutrition & Food Science, 53 (3), 500–520. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/NFS-03-2022-0104

- Rosenberg, M. J., Burnhill, M. S., Waugh, M. S., Grimes, D. A., & Hillard, P. J. (1995). Compliance and oral contraceptives: A review. Contraception, 52(3), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-7824(95)00161-3

- Salam, R. A., Das, J. K., Lassi, Z. S., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Adolescent health interventions: Conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4), S88–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.006

- Singh, P. (2013). Creating awareness on nutrition and health among rural adolescent girls of district Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand. Pantnagar Journal of Research, 11(3), 457–460.

- Staff, U. (2011). The state of the world’s children 2011-executive summary: Adolescence an age of opportunity: Unicef.

- Thoa, N. T. M., Thanh, N. X., Chuc, N. T. K., & Lindholm, L. (2013). The impact of economic growth on health care utilization: A longitudinal study in rural Vietnam. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-19

- Todd, A., Street, S., Ziviani, J., Byrne, N., & Hills, A. (2015). Overweight and obese adolescent girls: The importance of promoting sensible eating and activity behaviors from the start of the adolescent period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(2), 2306–2329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120202306

- Wassie, M. M., Gete, A. A., Yesuf, M. E., Alene, G. D., Belay, A., & Moges, T. (2015). Predictors of nutritional status of Ethiopian adolescent girls: A community based cross sectional study. BMC Nutrition, 1(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-015-0015-9

- WHO. (2006). Working together for health: The World health report 2006: Policy briefs.

- WHO. (2017) . Guideline: Preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups. World Health Organization.

- Zoellner, J., Connell, C., Bounds, W., Crook, L., & Yadrick, K. (2009). Peer reviewed: Nutrition literacy status and preferred nutrition communication channels among adults in the lower Mississippi Delta. Preventing Chronic Disease, 6(4).