Abstract

Nine oilseeds namely noug, gomenzer, linseed, soybean, sunflower, castor, sesame, ground nut and cotton are important in Ethiopia for edible oil consumption. During the last 60 years, 156 varieties with their production practices were registered. Sesame contributes significantly to the foreign currency earnings next to coffee. Despite the revenue from export, 90% of the national demand of edible oil is imported. Among oilseeds, groundnut, sunflower and soybean are the choice of cultivation both in high rainfall Western lowlands and irrigated areas of Awash, Omo and Wabe Shebelle and Dawa Genale valleys. Similarly, sesame exports can be doubled or tripled using irrigated production. In addition, soybean can be cultivated as a source of raw material for food and feed industries. Oil palm occupies small areas compared to other oil seeds but contributes half for global consumption. In the short term, sufficient amount of edible oil to meet the national demand can come from maximizing sesame export and production of sunflower, groundnut and soybean as raw material for local industries. In the long term, oil palm production is indispensable to feed the ever-growing population. Therefore, the ultimate solution for edible oil self-sufficiency for most customers can only come from the high-yielding perennial oil palm with high yield and less production cost.

1. Introduction

Among many plant species that bear oils in their seed in Ethiopia, only nine of them are economically important. These are noug (Guizotia abyssinica), linseed and gomenzer or Ethiopian Mustard (Brassica carinata) classified as highland (>2400 meters above sea level), sesame and groundnuts are classified as lowland (<1500 meters above sea level) oil seeds. Of these oilseeds, noug linseed, gomenzer and sesame are indigenous (Demissie et al., Citation1992). Sunflower, castor and soya beans are cultivated in a wide range of ecologies ranging from mid-altitudes (1500–2400 meters above sea level) to lowlands. Although cotton is cultivated mainly for its fiber the seed remaining after ginning contributes significant amount of edible oil for the nation. Cotton seed is a major raw material for oilseed mills in Addis Abeba (Addis Mojo), Adama and Gonder. These oilseed mills use mechanical extraction followed by refining processes. Linseed, safflower and nougare particularly used to prepare special traditional foods such as Siljue, telba fitfit and suf fitfit during fasting days. A large Coptic Orthodox Christian group uses exclusively vegetable oils up to 214 days a year. Oilseeds are also important in preparing instant foods for various purposes. They are used in food, feed, pharmaceuticals, detergent, cosmetics, ink, lubricant, and textile industries (Nehmeh et al., Citation2022). The industrial as well as the nutritional value of vegetable oil is dependent on its fatty acid composition, which is typical of the plant species.

The meal remaining after the oil extraction is an excellent feed for livestock, laying or meat poultry. Soybean is a versatile and multipurpose industrial raw material used as a source of vegetable oil, high-protein food and feed. The meal can be used as baby and milking mothers’ food additive and feed.

Oilseeds are also the traditional source of foreign exchange earnings since imperial era. Although the list of oilseeds exported from Ethiopia suchas soybean, castor, linseed and noug, sesame remains the most important export commodity next to coffee. Ethiopia is the second exporter of sesame globally next to Myanmar. Although sesame is cultivated in all lowlands, the product from Humera and Metema has prime quality. The crop can also be cultivated in Gode, Gambella, Omo and Awash valleys under irrigation and rainfall. Sesame seed white in color with oil content of 50% or more is classified as grade one in the world market.

Recently, the production of oilseeds such as noug, linseed, Gomenzer and safflower has decreased substantially. The traditional noug growing areas are being replaced by high yielding hybrid maize, rice and bread wheat. Nevertheless, the area coverage and productivity of sesame and soybean are increasing in an exponential order due to their demand in the world market.

The national vegetable oil demands have shown a severe shortfall during the last decade causing a severe foreign currency expense. Current domestic production of vegetable oil is less than 5%, and at least 95% of the demand is imported. The list of vegetable oils imported includes palm oil, sunflower, olive and peanuts. Recently some vegetable oil factories are constructed but in shortfall of raw materials. These factories refine imported crude palm oil or soybean oil, pack and avail for the market. Such business is estimated to decrease the foreign currency expense by 20%. However in doing so, the factories miss oilseed meal as their product to support the meat industry. These factories would prefer to crush oilseeds if raw materials are available.

The shortfall of vegetable oils has forced the cosmetic, pharmaceutical and detergent industries to import their entire raw materials. In other words industries that use vegetable oil as raw material are now at a standstill. In this paper we present the technological options and means to increase the production and productivity of oilseeds and hence edible oil in Ethiopia. The objective of this paper is to analyze the current data on oilseeds and draw short and long term recommendations that will alleviate the edible oil shortage in Ethiopia. The source of data was Central Statistics Agency, Ethiopian Revenue and Customs Authority and, annual reports of Research Centers and publications on oilseeds.

2. Political economy of oilseeds in Ethiopia

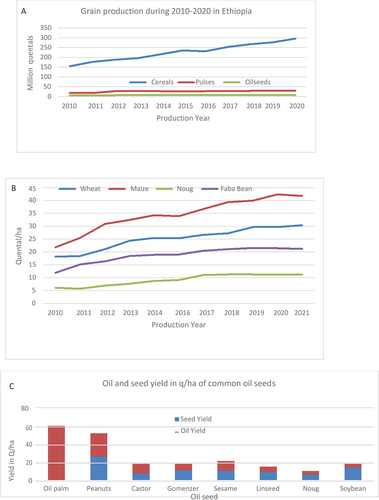

During 2010 to 2020, the total acreage under oil seeds was 0.63 in 2010 and 0.82 million hectares in 2017 (CSA, Citation2010–2020). Farmers tend to cultivate cereals on good land in good years and more pulses and oilseeds in bad years and on less fertile soils. During the same period (2010–2020), total production of grain crops was highest for cereals followed by pulses and oil seeds (Figure ). The productivity followed similar trend being highest for cereals (maize and wheat) followed by pulses (faba bean), and lowest for oilseeds (noug). Annual oilseeds are inherently low in yield compared to cereals, and pulses and perennials like oil palm The productivity of seed and oil yields per hectare based on experimental data of some oil seeds as compared to oil palm is shown in Figure . Oil yield is a function of oil content and seed yield, and crops with higher seed and oil content give a high oil yield. Hence among annual oil seeds, ground nut under irrigation will result the highest oil yield per unit area followed by sesame (particularly under irrigation). Despite that soybean has the lowest oil yield per hectare compared to groundnut, sunflower, and gomenzer, its meal remaining after the oil extraction has the highest protein and lowest fiber content. Therefore, it is preferred for food and feed formulation. The mean palm oil yield from oil palm is 36 q/ha globally, 60q/ha under well-managed plantations and 90q/ha from experimental plots (Donough et al., Citation2009; Murphy, Goggin, Russell, et al., Citation2021; Woittiez et al., Citation2017). Oil palm is a perennial tree, very productive, responsive to inputs with low production cost compared to the annual oilseeds cultivated and managed yearly. During the last 30 years, the global production of oil palm has increased tremendously.

Figure 1. A/Total production of grain crops, B/productivity of cereals (Maize and Wheat), pulses (Faba Bean) and oilseed (Noug) (CSA, Citation2010–2020) and C/productivity of seed and oil yield for some oilseeds (Alemaw, Citation2013).

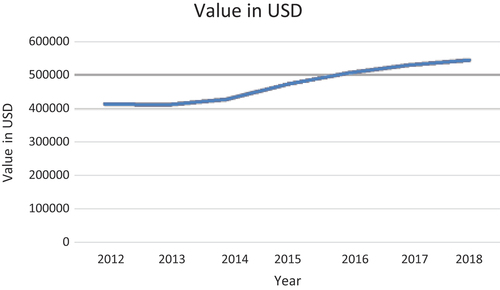

Every month, Ethiopia spends 48 million dollars importing edible oil which is predominantly palm oil (nearly 88%). That means the domestic source covers only 12% of the monthly demand. During the period from 2012 to 2017, the volume of imported edible oil increased from 312,218 tones to 521,707 tones with a 67% increase and during the preceding budget year, Ethiopia spent 576 million USD to import vegetable oil. In the current physical year, the Ministry of Trade announced that 480 million liters will be imported on top of 82.368 million liters that will be locally available. The burden of importing edible oil is increasing (USDA, Citation2018) from year to year due to population and economic growth (Figure ). In recent years, the price of food, particularly bread, has been the cause of public unrest and disobedience in neighboring countries like Egypt and Sudan. Similarly the price of imported edible oil in Ethiopia has the potential to cause public unrest and disobedience

The current demand of vegetable oil is 686,400,000 liters per year and will increase as the population increases at a rate of 2.3% per annum. Of the total demand of 686,400,000 liters of edible oil, 604,032,000 liters is to be imported. In order to cover the demand of edible oil from local production, a sustained increase in production through an increase in productivity and area should be attained. Hence substituting the import with local production should be one of the economic priorities of Ethiopia.

The demand of raw materials for the local industries is enormous as compared to the national production of oilseeds. The capacity of the Addis Mojo edible oil complex is 13,250 metric tons of Refined, Bleached and Deodorized (RBD) edible oil, 5800 metric tons of vegetable ghee and 754 tons of margarine per year. There are also factories in Adama, Gonder and Addis Ababa with various capacities. The capacity of Phibilla at Bure is 1400 tons per day, while WA at Debre Markos is 1350 tons per day (Tables ). The total capacity of these industries is 3205 tons/day or 32,050 quintals/day or 10 736 750 quintals per year (considering full capacity and one month of maintenance) as compared to 7.85 million quintals (2.1 million of this was sesame for export) of total oilseeds produced during 2019. The demand of edible oil factories that require soybean as raw material is shown in Table . The discrepancy is enormous and strengthening of research on oilseeds, enhancing the oilseeds seed system, scaling up of oilseeds production and productivity as well as enhancing the marketing system has a paramount importance. Of these activities strengthening of the oilseeds research and enhancing the oilseeds seed system is very important that it is the starter of the entire system.

Table 1. Number of oilseed varieties released in Ethiopia

Table 2. Seed yield of sesame in quental/ha under three moisture regmes

Table 3. Summary of seed yield in q/ha of two groundnut varieties Shulamith and NC-4× under three moisture regimes

Table 4. Seed yield, oil and protein content of released soybean varieties

Table 5. Oil content and fatty acid composition of Ethiopian oil seeds

3. Suitable areas of oilseed production

Oilseeds are classified as highland (linseed, gomenzer, noug and sunflower) and low lands (sesame, groundnuts, castor and soybean (Alemaw & Alemayehu, Citation1997; Alemaw et al., Citation1996). Of these, sunflower, soybean and castor are adapted from mid lands such as West Gojam and Hawassa to low lands as low as Omorate at an altitude of 360 masl. Linseed and gomenzer are adapted in the highlands with altitudes ranging from 2300 to 3000 masl what is commonly known as Central Ethiopian highlands. Hence, linseed and gomenzer share similar ecology as wheat and malt and food barley. However, wheat and malt and food barley are high yielders than the two oilseeds, one of the reasons why farmers prefer not to grow these oilseeds. Noug is adapted in the mid to high altitude ranging 1800 to 2400 masl and prefers heavy black soil such as the Fogera plain. Taxonomically Noug (G. abyssinica Cass) is a close relative of G. scabra common weed known as “Mech” and they have very similar traits. It is economically irresponsive to fertilizer and is a very excellent precursor to teff and hence crops following noug had less weed infestation.

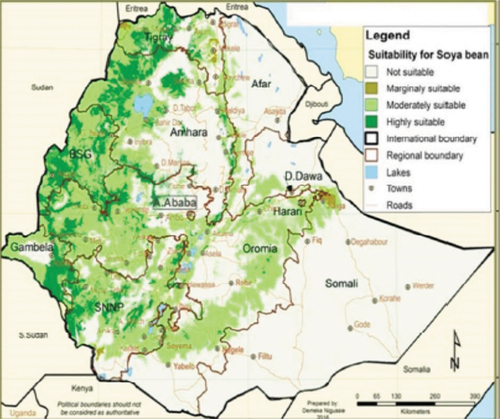

Ground nuts and sesame are adapted in three ecologies namely high rainfall such as Assosa, Gamblla, Metema, Humera and Pawe (Weastern Lowlands) and, irrigated such as Omo and Awash valleys, Gode and Arba Minch. Sesame and ground nuts are also adapted in low moisture stressed areas such as Babile, Bisidemo and Kobo. Normally seed yield and oil content are high under irrigation and low in low moisture stressed areas. Soybean is adapted in high rainfall areas of the Western lowlands stretching from Gambella to Humera (Figure ). Soybean is also high yielder under irrigation and can be a very good rotation crop for irrigated wheat and cotton. The oleo chemical crop castor is adapted in the low moisture stress areas of the rift valley as well as Eastern Ethiopia. The prime important trait, oil content, is affected by growing temperature, hence linseed, noug and gomenzer bear high oil content under low temperature while sesame, groundnuts, castor and soybean bear high oil content under worm temperature. Since oil yield is a function of oil content and seed yield, one has to compromise among the traits.

Figure 3. Suitable areas of soybean in Ethiopia (Demeke, Citation2018).

4. Factors that affect oilseeds production

The production and productivity of field crops are affected by climate, soils, management factors and inputs. In oilseeds, seed and oil yield productivity is affected by research and extension system, variety, inputs, good agricultural practices, improved seed, marketing and processing. Whereas seed yield and oil content are highly affected by growing environment, its quality is genetic and specific to crop species. However, the quality or fatty acid composition is highly heritable and can be modified through plant breeding. Edible oil should be colorless, odorless and tasteless, hence it has to pass through various steps of refining.

5. Research and extension

Increased crop production and productivity are the result of continuous and uninterrupted supply of improved technologies and knowledge to farmers (Alemu & Tekle Wold, Citation2011; Asnake, Citation2011; Mengistu, Citation2016). Research in genetic improvement, improved crop management (Belayneh et al., Citation1982), fertilizer and water management, seed processing and storage are very important for productivity. Oilseeds research should focus on productivity, oil content and quality. Although, the contribution of genetics to productivity on oilseeds is immense, crop and water management ranging from tillage to harvesting have equal influence on productivity and oil content.

Oilseeds research in Ethiopia started at Debre Zeit Experiment Station in the late 1950’s (Asrat, Feleke, Citation1965) and continued on noug, gomenzer and linseed at Holetta, sesame and ground nuts at Werer and Sunflower at Hawassa Research Centers. Later the program on sesame was transferred to Humera and groundnuts to Haramaya University while the program on sunflower somehow disappeared and no longer exits as a viable program. The crossing program of sesame at Werer was discontinued and the breeder seed of elite and released varieties of sunflower and peanuts is lost. It was also unfortunate that the collaboration with the International Crop Research Institute with the Semi-Arid Tropics on groundnut research is not as much as it should be. This signifies how oilseeds were carelessly handled by the research system, which has partly contributed to the status co we are in now regarding the shortage of oilseeds and edible oil in the country. Hence it is a very high priority that the research on crop management and variety development has to continue in a coordinated manner.

The current improved varieties of oilseeds were developed either from selection of introduced or indigenous germplasm. In order to achieve the desired goal, the future variety development should be based on genetic gain or crossing followed by selection, seed multiplication and multi-environment testing both under irrigation and rain fed. The irrigated areas of Gode, Werer, Omorate and Dawa Genale shall be used as testing sites for irrigated testing while Assosa, Gambella, Metema, Pawe and West Oromia as testing sites for rain fed.

The research on crop and water management such as tillage, rotation, planting rate and methods, cropping sequence, insect and disease management should be developed particularly for lowland production systems. The determination of optimum fertilizer rate and type, irrigation amount, methods and frequency on different soil types need to be availed for irrigated agriculture. In the lowlands, weeding and irrigation incur high production cost. Hence it is advisable to use sprinkler for irrigation and tractor mounted herbicides sprayers to control weeds. The low disease and insect incidence as well as low shattering under irrigation enables high seed yield.

Oilseeds research program should be equipped with skilled human recourses as well as Central oil quantity and quality laboratory. The laboratory should be equipped with equipment such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMR) for non-distractive oil content determination, Near Infrared Resonance (NIR) to determine protein content and Gas Chromatography (GC) for fatty and amino acid analysis. Advanced analytical hardware and reagents can be easily purchased as long as resources is available but equipment should only be in place once skilled human resources are acquired.

Currently, oilseeds are cultivated using farm saved seed and traditional farming practices. Oilseeds are usually sown on less fertile land and require minimum care such as weeding. Linseed and noug fields can be observed with heavy weed infestation and farmers rarely weed their oilseed crop. Although the federal Ministry of Agriculture and Regional Agriculture Bureaus have strong extension system for cereals and pulses, oilseeds have not benefited from such experience (Haile, Citation1992). Therefore, extension on oilseeds using full package as practiced for cereals needs to be offered to farmers. Most importantly the extension system should deliver improved varieties along their improved management practices as soon as they are registered. The release of improved varieties and crop and water management methods would be meaningless unless farmers benefit from the recent technology and knowledge timely. Hence, training farmers on improved varieties and cultivation techniques should be offered periodically.

6. Crop varieties

During the last sixty years, research on oilseeds variety improvement and crop management has been carried out throughout Ethiopia. The number of released oilseeds varieties suited for the high, mid and low altitude areas is shown in Table . However, the number of varieties under cultivation is unknown. It appears that the cultivated area under oilseeds in mid to highlands is shrinking and more and more occupied by high yielding cereals such as maize, wheat and malt barley. Farmers tend to earn more from cereals than inherently low yielding oilseeds. Hence the production volume of highland oilseeds is not expected to increase or at least contribute significantly to the national pool. Therefore, it is recommended to intensify oilseeds production in lowlands using irrigation.

Among the lowland oilseeds sesame is an important export commodity next to coffee and will continue to contribute significantly for foreign exchange earnings. The oil content of sesame is close to 50% and the yielding ability under irrigation is close to 18 quintals/hectare (Table ). Hence it is recommended that sesame should be cultivated as much as possible under irrigation than rainfall that causes severe shattering. Groundnut also follows similar trend that it results high yield under irrigation, intermediate in low moisture areas and low under moisture stress areas (Table ). Although the two oilseeds are adapted in the low moisture stress and high rainfall lowlands, they result in high yield under irrigation in lowland areas such as Omo and Awash valleys as well as Wabe Shebelle and Dawa-Genale basins. An important aspect of cultivation of sesame and groundnut under irrigation during the dry season is that there is less disease incidence and shattering. It appears that, groundnut has high yield, high oil content and excellent meal quality hence it should be a prime important oilseed for self-sufficiency. The use of groundnut for peanut butter and confectionery is also an added value.

7. Soybean

Research on soybeans was started in 1956 at Jimma Collage of Agriculture and consequently Debre Zeit experiment station and Chillalo Agricultural Development Unit. The major purpose of the research was to include soybeans in to the diet of Coptic Orthodox Christians who fast up to 214 days in a year. Soybean is adapted in a wide range of ecologies ranging from mid altitude high rainfall areas of Jimma and Pawe to extreme lowlands of Omorate. In lower altitudes such as Omorate (360 masl) and Kangate (390 masl), the crop is cultivated under irrigation resulting in high yield. In Western lowlands such as Gambella, Pawe, and Assossa, it is cultivated under rain fed. Adaptation trials as well as pilot production have shown that soybean can be successfully cultivated under irrigation as a rotation crop for cotton and cereals. Although soybean is considered as an oilseed in the developed world, in Ethiopia it is mostly used as a baby food and protein supplement for milking mothers (Fraanje & Garnett, Citation2020).

There are a total of 35 released soybean varieties equally divided in early, medium and late maturity groups. The seed yield in quintal/hectare at research and farmers field, oil and protein contents as well as year of release and breeder and maintainer centers for soybean varieties are shown in Table . These varieties were released by Pawe (9), Hawassa (12), Bako (9), Jimma (4) and Sirinka one. The seed yield from research plots varies from 18 to 37 quintals with oil content of about 20% and protein content of 40%. However, the seed yields from Metema Wereda in West Gonder Zone were exceptionally as high as 40 q/ha.

8. Sunflower

Sunflower has a similar ecology with maize and soybean and can be grown in wide range of altitudes and soil types (E. Westphal, Citation1975). Sunflower variety trials started in Alemaya College of Agriculture in 1960 with testing of 18 varieties during 1960–1967 (Asrate 1965). Although disease incidence and oil content were not reported, seed yields were 11 to 31 q/ha with an average of 20 q/ha. The performance of sunflower, noug, peanuts and gomenzer was studied at Bako during 1967 to 1970 (A. Westphal & Marquard, Citation1980). Further study on the comparison of noug and sunflower was conducted at Bako, Ambo and Dedessa in with and without fertilizer and two planting dates. The seed yield of sunflower was four to five times higher in seed yield and 7% in oil content than noug. The oil quality of sunflower and noug was similar with linoleic acid of sunflower being 62% and that of noug 76%. During 1982–1985 ten sunflower varieties were studied at seven locations and the seed yield varied 16–19 q/ha with an average of 18 q/ha (Solomon 1987). Although about 17 sunflower varieties have been released in Ethiopia (Table ), however, the production of those varieties and the crop in general is not manifested in the field, which is probably one of the reasons for the severe shortfall of edible oil in Ethiopia. This is because sunflower is one of the largest sources of edible oils in the world, next to soybean and oil palm. As reported by Pilorge(Citation2020), sunflower is the third oilseed produced in the world, the fourth vegetable oil and third oilseed meal among protein feed sources.

9. Oil palm

Oil palm is a very productive perennial crop adapted to 10 N and S of the equator. The crop supplies most of the vegetable oil to the world market with Indonesia and Malaysia being the most producers. It is by far the most important global oil crop, supplying about 40% of all traded vegetable oil. Palm oils are key dietary components consumed daily by over three billion people, mostly in Asia, and also have a wide range of important non-food uses including in cleansing and sanitizing products (Murphy et al, Citation2021).Palm oil has two types palm kernel oil and palm oil with the oil from the kernel containing very high level of saturated fatty acids. This crop was introduced in Ethiopia at Gelesha in Gambella Region (Chapman & Escobar, Citation2003), Omorate and Weito in Southern region and Bako in Oromia region. Although oil palm is the ultimate crop to solve the edible oil shortage, it is not being cultivated at a large scale in Ethiopia.

Based on availability of land and water resources, the seed and oil yield potential as well as the need of industries, it appears that ground nut, sunflower and soybean are good candidates for wider production of oilseeds both under small-scale and large-scale farms. Sesame is irreplaceable export commodity and its production and productivity particularly under irrigation is necessary for foreign exchange earnings. However, oil palm is the ultimate solution for the shortage of edible oil nationally due to its high productivity and low price (Chapman & Escobar, Citation2003). Hence research and development work on oil palm should be reinitiated as soon as possible.

10. Good agricultural practices and yield limiting factors

Oilseed yields are dependent not only on improved seed of recent variety, conducive climate and soils but also crop management practices. Cultural practices such as tillage, sowing methods and period, rotation, pest control, nutrient and water management for major oilseeds were studied. Although optimum agronomic practices are important for high yield, some practices in certain crops are more limiting than others. Linseed is a poor competitor to weeds and requires firm and well-prepared seed bed and uncontrolled weed competition could result up to 90% yield loss (Zewdie, et. al. Citation2009). In addition, linseed is susceptible to Fusarium wilt and hence crop rotation and using resistant variety is important for higher seed yield (Tefefe et. al. Citation2009). In Gomenzer, nutrient management is the sole important factor to a good seed yield and it does not set seed on poor soils without fertilizer. Shattering seems to be the most important trait in noug and sesame. Study on the optimum harvesting stage for noug showed that seed and oil yields were higher if harvested when majority of the plant part turns from green to yellow brown and the bud moisture content is 45% (Belayneh, Citation1987). Sunflower is very susceptible to leaf and root diseases such as powdery mildew, rust, Verticillium wilt and Black stem rot. However, Sclerotinia wilt and head rot is the most serious disease (Figure ). That can be managed using crop rotation that includes susceptible crops.

Figure 4. Wilt on sunflower crop planted after cotton at Gende Woha Metema Woreda in West Gonder Zone in 2020.

In the lowlands, weed control is the major production factor under irrigation or rainfall that incurs high production cost. Therefore, tractor mounted spraying of herbicides to control weeds may help to reduce production cost. Production of oilseeds under irrigation requires optimum frequency and amount of water for various soil types. For ground nut, the optimum amount and frequency of water application was, 125 mm applied every 21 days until 105 days after seedling establishment (Geremew and Fantaw 1992). The crop gets 50% of its requirement moisture from the upper most 0–30 cm of soil layer. The most critical water requirement of the crop was during flowering and seed set stages. Seasonal water requirement of sesame was 450 mm and 150 mm during establishment and three successive 100 mm of water every 21 days for up to 63 days after establishment. At Gode, 100–150 mm of water applied every 14 days gave higher yield.

Under high rainfall such as Western Ethiopia, Cerospora leaf spot and rust on ground nut and bacterial blight in sesame could cause a major loss (Shonga et. el. Citation2009). Sesame varieties tolerant to bacterial blight should be the first choice in humid climate. Over all optimum crop management is very critical for good yield and oil quality of oilseeds.

11. Oil content and quality

The oil content and quality of eight oilseeds are shown in Table . The three indigenous oilseeds namely noug (27–47%), gomenzer (35–46%) and castor (36–58%) have a wide range of oil content with castor having the highest. This is expected as these crops have a wide range of germplasm varying in oil content. The oil content is high for sesame and groundnut, intermediate for linseed and sunflower and low for soybean.

The fatty acid composition of oil determines its nutritional and industrial value (Daun, Citation1984). Fatty acids differ in their carbon number and whether single or double bonds. Fatty acids which are single bonds are saturated while those with one or more double bonds are known as unsaturated fatty acids. Saturated fatty acids with lower carbon atoms and no double bond such as lauric, stearic or palmitic fatty acids found in coconut and palm oils are semi solid at room temperature. Those fatty acids with higher carbon atoms and double bonds such as oleic, linoleic, linolenic fatty acids are liquid at room temperature. Therefore oleic, linoleic and linolenic are preferred as cooking oils while linolenic is essential fatty acid for monogastric animas such as human being. Often vegetable oils are a mixture of several fatty acids. Oils from Compositae family such as noug (Dutta et al., Citation1994), sunflower and safflower have very high linoleic acid content. The traditional oilseed oil from noug has high linoleic acid with pleasant odor and nutty taste. Similarly sesame, soybean and groundnut oils are also high in unsaturated fatty acids. The exception is gomenzer oil which is high in erucic acid and low in linoleic and oleic acids. However, fatty acids are highly heritable and simply inherited and genotypes containing low erucic and high oleic and linoleic have been developed. Rape seed (Brassica napus) genotypes containing low erucic and high oleic are known as canola to mean the trade name Canadian Oil (Daun, Citation1984). However, erucic acid is controlled by two alleles with additive effect and, the pollen has a direct effect on the embryo. Hence the production system requires a wide area of isolation distance and absolutely free from a plant of any other high erucic acid variety, which is impractical and that makes low erucic acid varieties value less in Ethiopia. Similarly sunflower varieties containing high oleic, low linoleic as well as ultra-high linoleic have been developed.

Vernonia and castor have unusual fatty acids namely vernolic and racinoleic fatty acids (Tesfaye 2003, Seegler, Citation1980). The seed and oil yield of vernonia is very low. Although it bears an important industrial oil, its seed yield and consequently oil yield do not encourage for its cultivation. In addition vernoleic acid can be epoxified from other high yielding oleic acid bearing crops such as rapeseed and sunflower. Hence, Vernonia has never been cultivated at economical and wider scale. On the other hand castor contains high oil up 50% or more and high seed yield (Alemaw, Citation2016). Hence its oil yield is one of the highest per unit area with more than 3000 patented applications. India, China, Brazil and USA are the major producers. Ethiopia is a center of origin of castor but never benefited as much as it should be probably due to the low development of the chemical industry.

Oil content of an oilseed crop is its prime trait and hence crops that have higher oil content≥40% are preferred for cultivation. The meal remaining after the oil extraction is also a valuable feed source. The meal of some oilseeds such as sunflower and noug is high in fiber content as compared to soybean and linseed meal. The meal of an oilseed takes one third of the value of the commodity; exception would be soybean where its meal is the most preferred.

12. Improved seed

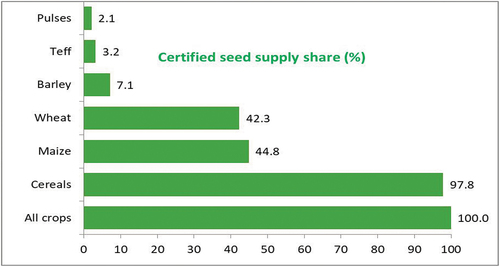

Seed is basic input in farming and unlike other inputs such as fertilizer and pesticides, it can be produced by the farmer himself. Whereas seed can be improved by processing and storage alone, improved seed of recently released varieties is the best input for a higher seed yield (Zewdie and Abebe 2016). The ultimate goal of developing improved variety is to deliver improved seed for the farmer. As indicated above, there are 156 oilseed varieties released by federal and regional research centers so far. However, there is no enterprise that multiplies improved seed of recently released oilseeds varieties in sufficient quantity (Figure ). Some oilseed crops have their inherent constraint for ease of seed multiplication. Groundnut requires digging and shelling while shattering is the major problem in noug and sesame. Although there is tractor mounted, and animal drawn digging implements as well as manual and motorized shelling machines, they incur cost and deter seed growers. Whereas almost all oilseeds can be row planted only sunflower, gomenzer and soybean can be harvested using combiner. In addition, most of the oilseeds such as noug, sesame, gomenzer, castor, sunflower and linseed have high multiplication rate or low seed rate which makes them unattractive for seed growers. Therefore, the regional and federal seed enterprises should multiply and avail improved seed for the farmer at an affordable prices. In other words, multiplication and supply of improved seeds of oilseed varieties should be a government program

Research centers should be encouraged to multiply Early Generation Seed of oilseed varieties while the federal and regional seed enterprises can multiply the basic and certified generations (Wijnands et, Citation2011, Wakjira et al Citation2012, Terefe and Atnaf, Citation2012). The seed multiplied by the Seed Enterprises such as Oromia, Amhara and SNNPR can be distributed like that of cereals. Some of the private farms such as those in Beneshangul Gumz and West Gonder can be licensed as seed growers but they need to get Early Generation Seed. Availability of improved seed in sufficient quantity, quality and appropriate container/storage is one of the prime factors that can contribute to edible oil self-sufficiency.

Agricultural Research Centers such as Pawe, Gonder, Assosa, Jimma and Bako can assist farmers to grow their own seed or cultivate quality declared seeds (Abebe et al. 2017). Soybean Early Generation Seed production and supply at Pawe and Sesame at Gonder Research Centers are a good start.

13. Mechanization

Mechanization plays its own important role in crop production particularly in the lowlands where labor is expensive and unproductive (Kelemu and Getinet, Citation2016). Therefore, one of the factors for high productivity of oilseeds is to use mechanization for tillage, planting and harvesting. Row planting and spacing reduces seed rate and facilitates ease of cultivation. In the lowlands weeding is the major operation and most expensive hence tractor mounted spraying of herbicides improves productivity and reduces production cost.

Among oil seeds sunflower, soybean and gomenzer can be mechanized from planting to harvesting while ground nut in addition to row planter requires Digger and Sheller. Sesame can be planted in row but harvesting should be manual due to shattering. Studies on sesame have shown that row planting, use of fertilizer and thinning resulted in the highest economic return. Therefore, mechanization is one component of the production system as it reduces seed rate, production cost and loss due to shattering.

14. Marketing

In this context the term marketing is defined as “the performance of all business activities involved in the flow of goods and services from the point of initial agricultural production until they are in the hands of the ultimate consumer (Richard, Citation1961). Hence it includes transportation, processing, handling and delivery. Market efficiency is the satisfaction of producers and consumers along the value chain (Elias, Citation2005). A study conducted on oilseeds in 1973 shows that the main oilseed crops cultivated in Ethiopia by then were noug, linseed, gomezer, castor, groundnuts, sesame, sunflower and cotton seed. During the period 1969–1971 the total production of oilseeds was on average 5.23 million quintal per year with noug being the most important followed by sesame. The average area under oilseeds was 924,633 ha. During 1973, Ethiopia imported 1000 tons of edible oil. During the same period, the per capita consumption was 1.04 kg/year for rural and 8.04 kg/year for urban consumers. Similarly, oilseeds were the fourth export commodities with sesame and oilseed cake being the dominant commodities and in 1970 it amounted 32,379,000 birr. During that period 59,085 quintals of oilseed and 340,560 q of oil meal was exported. Farming was traditional and there was little research done on oilseeds.

In addition marketing was unstructured.

A decade later, a study was conducted on “The production and marketing of oil seeds in Ethiopia’ by Tamiru (Citation1984). During 1975–81 the average annual production of oil seeds was not higher than the previous decade but with 67% of domestic consumption. However, it was also estimated that about 17.5 % of the produce is lost to post harvest loss mainly due to poor storage. During the same period Ethiopia exported 35 % of the produce but contributed only 1% to the total global market. Oilseeds cultivation was using traditional cultivation methods and farm saved seed. Oilseed marketing consists of assemblers, whole sellers, possessors and exporters. Marketing was also as a result of government grain marketing corporations that gathers produce from farmers and either deliver for processors or export. It was suggested that the market was not efficient and both the producers and consumers were dissatisfied.

Thirty years later, the average total production of oilseeds during 2017 to 2020 was 9.54 million quintals and had doubled during the last 50 years (CSA 2020). During the last ten years, soybean has also become the major oilseed increasing in production as well as area coverage due to its meal. During the last ten years sesame and soybean are traded in the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) floor and sesame has become the second most important export commodity next to coffee (Negash, Citation2015). During 2018/19 Ethiopia exported 215,190 tons of sesame, 122,642 tons of soybean and 25,596 tons of noug worth of 430 million USD. On the other hand, the local production contributes only about 10% to the national edible oil demand. The revenue from sesame export covers the expense to import palm oil. Economic value of soybean is primarily as raw material for starved feed and food fortification industries. Hence the export of soybean should discouraged to support the meat industry particularly poultry nationally (Hartrichand Berhanu, Citation2021).

At global level, oilseeds marketing is dominated by palm oil, soybean and sunflower (Vinnichek et al, Citation2019). Palm oil and palm kernel oil are extracted from oil palm fruit flesh and seed respectively (Kalyana, et. a. Citation2003). Out of the total palm oil produced in 2016, 72% is used for food, 18% for personal care and detergent and 10% for biofuel (Voora, Citation2020). In 2016, 75% of the total palm oil produced or 48.9 million tons worth of 28.2 billion USD palm oil and 3.7 billion palm kernel oil was exported. The market value of the sector was 65 billion USD.

The global market of soybean is dominated by Brazil, USA and Argentina with China being the major customer (USDA 2018). In 2018/19 out of the total 594 million tons of oilseed produced, 354 million ton was soybean. In the same year, 49.8 million tons of sunflower mainly in Ukraine, Russia, China and Kazakhstan was produced. In addition, one million tons of groundnut was produced in Africa during 2018/19.

15. Processing and packaging

Edible oil should be pressed or extracted from seeds mechanically or using organic chemicals. First seeds should be cleaned from any unwanted materials and conditioned if necessary dehulled. The oil is mechanically pressed to expel the oil from seeds containing≥30% oil. Seeds that contain less than 30% are flanked and the oil extracted using organic chemical like hexane. Mechanical pressing leaves 10–20% oil in the cake depending on the efficiency of the machine and the remaining oil is extracted using hexane. The crude oil is then centrifuged and passed through various steps of refining. Hence the crude oil passes through physical refining, deodorization, neutralization, to make the final product colorless, odorless and tasteless. Gomenzer, cottonseed, sesame, and linseed oils must pass through a full refining process (degumming, neutralizing, washing, drying, bleaching, and deodorization) while, Noug, groundnut and sunflower seed oils need only to pass through a semi-refinery system namely neutralizing, washing, and drying. In many cases vegetable oil is also fortified with vitamins. Once the oil is refined it is fortified with vitamins and packed using appropriate containers.

A recent survey indicates that there are 227 oil factories distributed throughout the country but mostly in and around the capital. These factories were established between 1978 and 2017 but some large factories are established since then in the Amhara region. These factories can process noug, linseed, gomenzer, sesame, groundnut, cotton, soybean and crude palm oil. Of the 227 factories, 220 use mechanical pressing, one solvent extraction and five both. Oils can also be processed in batch or continuous. Of the 227 factories, 8 are large with capacity of ≥ 5000 liters per day, 60 medium with a capacity of 500–5000 liters and the rest are small with≤500 liters. Almost all factories perform≤50% of their capacity and over 30% of them perform≤25% and the average being 38%. Once oil is refined, it is fortified with vitamins and packed in an appropriate container. However, factory should have the technical knowledge and internal quality assurance facility but only few and large factories have quality assurance facility. It appears that shortage of raw materials, shortage of human resources, packaging and lack of internal quality control are the major problems in the processing sector.

16. Food safety and microbial quality

Microorganisms are known to cause chemical changes that lead to quality deterioration of edible oils and hence health problems. Extraction of vegetable oils requires careful processing of raw material free from foreign matters and microbial contamination as well as high level of hygiene of machineries and personnel. In addition, vegetable oils should be handled, packed, transported and stored in hygienic manner. Unfortunately, some of the vegetable oils particularly palm oil is smuggled with poor handling, storage and transportation that results in quality deterioration.

A study was conducted from January 2010 to January 2015 at Ethiopian Public Health Institute, food safety and public health microbiology research laboratory on edible oil collected from all over Ethiopia (Gobena, et. al. Citation2018). One hundred twenty five edible oil samples were examined among which 48% samples were containing a varying number of bacteria and/or Moulds. The aerobic plate count detected in 35.6%, moulds 24.8%, yeasts 3.1%, total coliforms 4.5%. Fecal coliforms, E.coli and S.aureus were found only in one sample and none of the examined edible oil samples contain Salmonella and Shigella organisms. Food safety is related to good agricultural practices, good hygienic practices, good processing practices, hazard analysis and critical control point system. It may be paradoxical to discuss on the subject of food safety when millions are suffering from lack of food and of the most inferior quality. However, at the national level, both food shortage and food safety are problems in the Ethiopian economic development. Organizations involved in food safety system include Ministry of Health, Ministry of Agriculture, Quality and Standards Authority of Ethiopia, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Ethiopian Manufacturing Industries Association.

17. Outlook on edible oil self sufficiency

The national demand of oilseeds is estimated about 906 million liters per year as compared to 1.25 billion liters of oil that can be produced by the 30 large edible oil factories at full capacity. However, the edible oil factories are working below their 50% capacity due to shortage of raw materials. The road towards edible oil self-sufficiency can come from short- and long-term strategies.

18. Short term

In short term, research, extension and production both under rain fed and irrigation on annual oilseeds can assist the availability of raw materials for the local industry and export market. Although, there are several annual oil crops, ground nut, sunflower and soybean that have wider adaptation should be given priority. Sesame should be considered for export. The production of sesame and groundnuts should be promoted under irrigation in order to obtain high yield with high oil content. The yield of sesame under irrigation is three times higher than rain fed hence, production for export can be doubled and even tripled. The extension and production of groundnut should be promoted along with the lifter and Sheller machines. Sunflower has high yield with high oil content and similar quality with noug oil. Hence both sunflower and soybean need a priority. This does not mean that other oilseeds particularly linseed and noug should not be cultivated rather can be grown as a specialty crops. Noug bears yellow color oil with nutty taste and pleasant odor with very high linoleic acid, hence it can be consumed locally or exported as a specialty oil.

Export market for any of the oilseeds particularly sesame and soybean is higher to the extent that the local industry may not afford it. However, the revenue from sesame can be used to import palm oil easing the burden of foreign exchange. The export value of annual oilseeds such as sesame is higher than their possible local value and the value of the oil will be beyond the reach of average Ethiopian. However the value of soybean is primarily as a raw material for the feed and food industries and its value is mainly as protein source and the oil is obtained while extracting the primary product. Probably the shortest and easiest way to ease the current shortage of edible oil in Ethiopia is maximizing sesame export and palm oil import.

19. Long term

In the 1970’s FAO forecasted that there will be edible oil shortage in Eastern Africa and set up experimental plots and pilot production of oil palm at Gelesha; what is now in Mizing Zone of the Gambella Region (Chapman & Escobar, Citation2003 and Alemaw, Citation2011). The experiment consisted of 13 hybrids called cold tolerant oil palm hybrids in three replications. These materials were hybrids between Cameroon and Tanzania genotypes produced in Costa Rica by a private company. The pilot production was on 100 hectare of land with mini processing machine. The idea was to expand oil palm to a large scale both in Ethiopia and neighboring countries. Whereas other countries have taken positive steps towards self-sufficiency, the program in Ethiopia was, discontinued following the down fall of the Derg government. Oil palm is a very high yielding crop with low production cost that results in relatively cheap edible oil. Over 50%

of the world edible oil production comes from palm oil. The research investment on oilseeds should focus on high yielding annual and perennial oilseeds including in human and facility development. The Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research has a Center at Tepi which is not far from Gelesha and can be in charge of the research and Gambella Agriculture Research Institute can be assisted to manage research plots and carry out extension work. Whereas the majority of the population can consume palm oil, the middle class can afford sunflower, soybean and groundnut oils.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Getinet Alemaw

Dr. Fekadu Gurmu has been a senior plant breeder and agricultural research coordinator in the Ethiopian Agricultural Research Council Secretariat. His main research interests are focused on breeding of legumes, oil crops and horticultural crops. He has been working as a national program coordinator for soybean and root crops research in Ethiopia. He is a member of various research for development scientific associations including The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS).

Fekadu Gurmu

Dr. Fekadu Gurmu has been a senior plant breeder and agricultural research coordinator in the Ethiopian Agricultural Research Council Secretariat. His main research interests are focused on breeding of legumes, oil crops and horticultural crops. He has been working as a national program coordinator for soybean and root crops research in Ethiopia. He is a member of various research for development scientific associations including The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS).

References

- Alemaw, G. (2011). Oil palm: The solution for oil crises in Ethiopia. In Geremew Terefe, Adugna Wakjira and Dereje Gorfu, Oilseeds: Engine for Economic Development, Proceedings of Oil Seeds Research in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp. 17–19).

- Alemaw, G. (2013). Review on the challenges for the increased production of oilseeds in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 24(1), 1–44.

- Alemaw, G. (2016). Diversity of (Ricinus communis L.) in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Science, 26(2), 57–67.

- Alemaw, G., & Alemayehu, N. (1997). Highland oil crops: A three decade research experience in Ethiopia. EIAR. Research Report No 30.

- Alemaw, G., Rakow, G., Raney, J. P., & Downey, R. K. (1996). Agronomic and performance and seed quality of Ethiopian Mustard, Can. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 76(3), 387–392. https://doi.org/10.4141/cjps96-069

- Alemu, D., & Tekle Wold, A. (2011). Research and development strategies for oilseeds. In Geremew Terefe, Adugna Wakjira and Dereje Gorfu, Oilseeds: Engine for Economic Development, Proceedings of Oil Seeds Research in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp. 1–7).

- Asnake Fikre. (2011). Enhancing production, productivity, quality and marketing of oilseeds in Ethiopia. In Geremew Terefe, Adugna Wakjira and Dereje Gorfu, Oilseeds: Engine for Economic Development, Proceedings of Oil Seeds Research in Ethiopia Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp. 7–24).

- Belayneh, H. (1987). Determination of optimum harvesting stage for noug (Guizotia abyssinica CASS. Journal of Agriculture Science, 9, 83–94.

- Belayneh, H., Riley, K. W., Tadesse, N., & Alemaw, G. (1982). The response of three oilseed brassica species to different planting dates and seed rates in the high lands of Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, V(1), 22–31.

- Chapman, K. R., & Escobar, R. (2003). Cold tolerant or altitude adapted oil palm hybrid development initiatives in the Asia/Pacific Region. UJT, 6(3), 134–138.

- CSA. (2010-2020). The federal democratic republic of Ethiopia, central statistics agency agricultural sample survey 2019/20(2012 E.C.) (Vol. III). Report on Farm management Practices Peasant Holdings.

- Daun, J. K. (1984). Oilseeds Grading: Quality control in oilseeds marketing. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 61(6), 1117–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02636236

- Demeke Nigussie. (2018). GIS- based land suitability mapping for legume crops technology targeting and scaling up. Ethiopian Journal of Crop Science, 6(3), 180–198.

- Demissie, A., Tadesse, D., Mulat, G., & Beyene, D. (1992). Ethiopia’s oilseed genetic resources in oilseeds research and development in Ethiopia. Proceedings of the First National Oilseeds Workshop, 3-5 December, Addis Abeba Ethiopia, (pp. 13–24).

- Donough, C. R., Witt, C., & Fairhurst, T. H. (2009). Yield intensification in oil palm plantations through best management practice. Better Crops, 93(1), 12–14.

- Dutta, P. C., Helmersson, S., Kebedu, E., Alemaw, G., & Appelqvist, L. A. (1994). Variation in lipid composition of niger seed (Guizotia abyssinica Cass.) Samples collected from different regions in Ethiopia. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 71(8), 839–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02540459

- Elias Gebreselassie Fanta. (2005). The production of oilseeds in Ethiopia: Value chain analysis and the benefit that accrue to the primary producers [ M. Sc. Thesis]. In Development Studies at the Institute for Social Development, School of Government, Faculty of Economics and Management Science. University of the Western Cape.

- Ethiopian Agriculture Authority. (2021). Plant variety release, protection and seed quality control directorate. In Minstry of Agriculture (MoA) (Ed.),Crop variety register (pp. 1–21).

- Feleke, A. (1965). A progress report on cereals, pulses and oilseeds research, branch experiment station. Collage of Agriculture Haile Selassie University.

- Fraanje, W., & Garnett, T. (2020). Soy: Food, feed, and land use change. (Food source: Building Blocks). Food Climate Research Network, University of Oxford.

- Gobena, W., Girma, S., Legesse, T., Abera, F., Gonfa, A., Muzeyin, R., & Fekade, R. (2018). Tigist Yohannes 2018 microbial safety and quality of edible oil examined at Ethiopian public health institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A retrospective study. Journal of Microbiology & Experimentation, 6(3), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.15406/jmen.2018.06.00203

- Haile, A. (1992). Transfer of highland oilseeds Technologies 1992. Proceedings of the First National Oilseeds Workshop 3-5 December 1991, Addis Abeba, Addis Abeba, (pp. 193–201).

- Hartrich, S., & Berhanu, A. (2021). A market systems analysis of the edible oils sector in Amhara, Ethiopia. International Labor Organization.

- Institute of Agricultural Research. (1966-1980). Bako research station, progress report for the period March 1966-April 1979.

- Institute of Agricultural Research. (1973). Gode research station progress report for the period April 1972 to March 1973.

- Institute of Agricultural Research. (1975). Gambella research station progress report for the period March 1973-1976.

- Institute of Agricultural Research. (1982). Proceedings of the 13th National Crop Improvement Conference, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp.331–332).

- Institute of Agricultural Research. (1986). Lowland oil crops progress report for the period bako research station progress report for the period march 1973–1983.

- Kalyana, S., Sanbanthamurthi, R., & Tan, Y. A. (2003). Palm fruit chemistry and nutrition. Asian Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrient, 12(3), 355–362.

- Kelemu, F., & Getinet, B. (2016). Agriculture mechanization research in Ethiopia. Proceedings of the National Conference on agricultural Research for Ethiopian Renaissance held on January 26-27 2016 at UNECA Addsi Abeba, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp. 341–352).

- Mengistu, F. (2016). Fifty years of agricultural research and the need to adapt to evolving agricultural needs. Proceedings of the National Conference on agricultural Research for Ethiopian Renaissance held on januarry 26-27 2016 at UNECA Addis Abeba, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp. 1–10).

- Murphy, D. J., Goggin, K., & Paterson, R. R. M. (2021). Oil palm in the 2020s and beyond: Challenges and solutions. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience, 2(39), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-021-00058-3

- Murphy, D. J., Goggin, K., Russell, R., & Paterson, M. (2021). Oil palm in the 2020s and beyond: Challenges and solutions. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience, 2(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43170-021-00058-3/

- Negash Geleta Ayana. (2015). Status of production and marketing of ethiopian sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum L.): A review. Agricultural and Biological Sciences Journal, 1(5), 217–223.

- Nehmeh, M., Rodriguez-Donis, I., Cavaco-Soares, A., Evon, P., Gerbaud, V., & Thiebaud-Roux, S. (2022). Bio-refinery of oilseeds: Oil extraction, secondary metabolites separation towards protein meal valorisation—a review. Processes, 10, 841. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr10050841

- Pilorgé, E. (2020). Sunflower in the global vegetable oil system: Situation, specificities and perspectives. OCL, 27, 34. Article Number 34, https://doi.org/10.1051/ocl/2020028

- Richard, L. K. (1961). Marketing, agricultural products. The Macmillan company, 1961.

- Seegler, C. J. P. (1980). Oil crops in Ethiopia, their taxonomy and agricultural significance. Center for Agricultural Publication and Documentation.

- Shonga, E., Tertefe, G., Mulat, B., Mahari, Z., & Belay, B. (2009). Review on insect pests of oil crops in Ethiopia. In A. Tadesse (Ed.), Increasing crop production through improved plant protection (Vol. II, pp. 93–116). Plant Protection Society of Ethiopia (PPSE) PPSE and EIAR.

- Tamiru, N. (1984). The production and marketing of oil seeds in Ethiopia. An essay presented to department of economics college of social science in partial fulfilment the requirements for the degree. Bachelor of Arts in Economics, Addis Abeba University.

- Terefe, G., & Atnaf, M. (2012). Importance of Informal seed system in sesame technology scaling up in Ethiopia. In A. T. Wold, A. fIkre, D. Alemu, L. Desalegne, & A. Kirub (Eds.), The defining moments in the Ethiopian seed system (pp. 429–442). EIAR.

- Terefe, G., Gorfu, D., Tesfaye, D., & Abebe, F. (2009). Review on Diseases of oil crops in Ethiopia. In A. Tadesse (Ed.), Increasing crop production through improved plant protection (Vol. II, pp. 253–274). Plant Protection Society of Ethiopia (PPSE) PPSE and EIAR.

- United States Department of Agriculture. (2018). Oilseeds, world markets and trade, Foreign agriculture service. USDA.

- Vinnichek, L., Pogorelova, I. E., & Dergunov, A. (2019). Oilseed market: Global trends. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 274(1), 274. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/274/1/012030

- Voora, V., Larrea, C., Bermudez, S., & Baliño, S. (2020). Global market report: Palm oil. International Institute of Sustainable Development. R3B 0T.

- Wakjira, A., Delesa, A., & Weyossa, B. (2012). Progress and challenge of the informal seed system of high land crops. In A. T. Wold, A. fIkre, D. Alemu, L. Desalegne, & A. Kirub (Eds.), The defining moments in the Ethiopian seed system (pp. 429–442). EIAR.

- Westphal, E. (1975). Agriculture Systems in Ethiopia. Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation.

- Westphal, A., & Marquard, R. (1980). Yield and quality of brassica species in Ethiopia. Plant Research Development, 13, 114–127.

- Wijnands, J. H. M., Wmejierink, G., & Van Lao, E. V. (2011). Soybean and sunflower seeds production opportunity in Ethiopia. In Geremew Terefe, Adugna Wakjira and Dereje Gorfu, Oilseeds: Engine for Economic Development. Proceedings of Oil Seeds Research in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (pp. 7–24).

- Woittiez, L. S., van Wijk, M. T., Slingerland, M., van Noordwijk, M., & Giller, K. E. (2017). Yield gaps in oil palm: A quantitative review of contributing factors. European Journal Agronomy, 83, 57–77.

- Zewdie, K., Amede, T., & Senebo, W. (2009). Review of weed research in oilcrops in Ethiopia. In A. Tadesse (Ed.), Increasing crop production through improved plant protection (Vol. II, pp. 339–354). Plant Protection Society of Ethiopia (PPSE) PPSE and EIAR.