?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We examined factors that influence farm size sustenance and food consumption status of rural farm households. We used survey data comprising a sample size of 390 households. The study employed quantile and ordered logistic models to estimate the impacts of farm sustenance indicators on farm size cultivated and food consumption, respectively. We found that farm size is influenced positively by input expenditures, household sizes, types of crops, farm credits and subsidies. Besides, lack of farm labour adversely affected farm sizes of some categories of farmers. Besides, increasing farm input expenditures, lack of labour, farm credits and subsidies reduce the food consumption status of the households. We recommend that policymakers consider an integrated approach to farm sustenance and specific segregated attention to the individual categories of food consumption status of farm households. These could be achieved through the provision of farm credits and subsidies among other factors that sustain farm sizes and food consumption of the households.

1. Introduction

Strategies for sustaining farm production in developing countries are focused more on farm expansion or conservation of farm sizes than improving crop yields (Lu & Horlu, Citation2019). Investments in farm production are, therefore, directed toward sustaining cultivated farm sizes over a given production period. The reason is that farm sizes under cultivation reflect the level of farm inputs used and the corresponding expenditures over a specific period. Farm sizes and input expenditures might, therefore, point to the quantity of food production and consumption by farm households (Lu & Horlu, Citation2019; Ngema et al., Citation2018; Samberg et al., Citation2016; Wossen et al., Citation2018). However, it is often a challenge to develop farm support strategies that allow easy access to farm credits and subsidies that curb the rising expenditures on farm inputs, among other factors. The scenario may pose some difficulty in sustaining farm sizes under crop production. These difficulties could make farm size sustenance and food consumption status of rural farm households unstable (Ogunniyi et al., Citation2021; Takeshima & Liverpool-Tasie, Citation2015). Rural farm households, therefore, often make some decisions and efforts to harness productive resources to sustainably cultivate expected farm sizes as the basis for sustaining their food production and consumption (Rammohan & Pritchard, Citation2014).

In Ghana, one important factor for sustenance of food consumption is seasonality of crop production with intermittent periods of lean availability of food (Fahey et al., Citation2019; Shukla et al., Citation2021; Wijesinha-Bettoni et al., Citation2013). The situation is dilapidated by lack of agricultural credits and subsidies, which are essentially required during cropping seasons. Hence, one of the strategies adopted by farm households is trading off their resources between food consumption and farm production (Ecker & Hatzenbuehler, Citation2022; Wossen et al., Citation2018). In such cases, farm households often reallocate their scarce resources between food consumption and farm input expenditures that correspond with expected farm sizes cultivated (Gautier et al., Citation2016). Thus, during cropping seasons, a farm size cultivated could be constrained by inadequate resources for sustaining farm production and consumption status (Abu & Soom, Citation2016; Ahmed et al., Citation2017; Ecker & Hatzenbuehler, Citation2022; Tibesigwa & Visser, Citation2016). In particular, cropping seasons bring about households offering temporary sacrifices by lessening their food consumption for farm cultivation or the vice versa (Ecker & Hatzenbuehler, Citation2022), depending on available production resources. The implication is that there may be alterations in farm expenditures as a strategy for the tradeoffs between farm expenditures and households’ food consumption over a specific period.

Some scholars have established that consistent farm input expenditure can be a strategy for farm sizes and food production substance (Ren et al., Citation2019). Meanwhile, improving farm production by access to farm credits and subsidies as strategies that enhance farm input expenditures could increase the food consumption status of rural households (Smale et al., Citation2020). However, in the absence of farm production supports, farm households could skew their little resources towards either expanding their farm sizes with a corresponding rise in input expenditures for farm-size sustenance or reducing the farm sizes to maintain their food consumption status (Lopez-Ridaura et al., Citation2018; Perez et al., Citation2015). In such cases, a farm household may reduce farm production by spending less on farm inputs, to the detriment of sustaining their food consumption status or vice versa.

Further, previous literature has pointed out that external shocks could be adverse to farm production and the food consumption status of farm households (Tan & Thamarapani, Citation2019). These shocks may include drought, floods, pandemics, and pest invasions, which could also affect farm expenditures. In such cases, households may reallocate their resources toward food consumption during external shocks. Some farmers may also resort to accruing incomes from nonfarm work and receiving remittances from relatives to invest in their farming activities (Dzanku, Citation2019; Schmidt et al., Citation2020; Sen et al., Citation2021). Thus, nonfarm work is a critical source of income for sustaining farm production and food consumption in rural areas (Kuwornu et al., Citation2018; Owusu et al., Citation2011). The reason is that farm households’ incomes from nonfarm sources help them to support farm production and food consumption expenditures (Giller, Citation2020). However, discussions on linkages between strategies for sustainable food production and farm expenditures on cultivated farm sizes are limited in the literature. This study has, therefore, examined these linkages using survey data on rural southern Ghana.

The study has specifically answered the following questions which have not been previously answered in the literature. First, is there any complete dominance in the level of food consumption status, cultivated farm sizes, and input expenditures over the periods of the study? Second, what factors influence the sustenance of cultivated farm sizes of the households? Third, what factors determine the food consumption status of the farm households? Thus, we have comparatively tested the dominance of the three categories of food consumption with respect to cultivated farm sizes and farm input expenditure over the study period. Additionally, we have examined factors that influence farm size sustenance and food consumption status of farm households in Ghana.

2. Analytical methods

2.1. Conceptual framework

Farm sizes and input expenditures play essential roles in the food production and consumption of farm households (Lu & Horlu, Citation2019; Wossen et al., Citation2018). Rural farm households, therefore, often make some decisions and efforts to harness productive resources to sustainably cultivate expected farm sizes as the basis for sustaining their food production and consumption (Meyfroidt, Citation2018; Rammohan & Pritchard, Citation2014; Wossen et al., Citation2018). However, discussions on linkages between strategies for sustainable food production and farm expenditures on cultivated farm sizes and input expenditures are limited in the literature. This study has, therefore, examined these linkages using survey data on rural southern Ghana. This study is therefore based on the notion that farm households choose between reducing cultivated farm sizes or reallocating resources to sustain their food consumption (Li et al., Citation2020; Umar, Citation2014). As a strategy, the household solicit farm credits from various sources as buffers for sustaining their farm sizes or food crop production levels (Mamiit et al., Citation2021), as shown in Figure . The farm households also access subsidies on farm inputs as a strategy for the sustenance of farm production. The aim is to improve the food consumption status of farm households. Based on the foregoing literature, we have captured farm sustenance strategies depicting the use of farm labor, credits, subsidies, inputs costs, and type of crops among other factors of production to sustain farm production on a given farm size.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of factors determining farm size sustenance and food consumption status of farm households.

Based based the preceding analytical framework, the current study tested the following hypotheses: 1. A rise in farm input expenditures and lack of farm credits and subsidies have no influence on sustenance of farm sizes. 2. A rise in farm input expenditure, changes in farm sizes, and lack of farm credits and subsidies, among other strategies, have no influence on the food consumption status of rural farm households.

The conceptual framework presented in Figure answers questions on whether factors of farm substance adopted by rural farm households determine their farm sizes cultivated and food consumption status. The figure also includes strategies adopted in sustaining farm production by using consistent farm input expenditures, credits, subsidies, maintaining their farm sizes and types of crops cultivated by the rural farm households (Atube et al., Citation2021; Mamiit et al., Citation2021; Pauw, Citation2022). Besides, the study has identified three main categories of farm households based on their perceived food consumption status. These include 1. Households with “low food consumption status”, and this category embraced households that have lowered their food consumption to spend more on farm production. 2. Households that maintained a “moderate level” of food consumption, which reflects the ability of farm households to maintain or improve their food consumption (Aweke et al., Citation2020). 3. Households that managed to attain “high food consumption status” comprises the households that often have more than their perceived minimum requirement of food consumption.

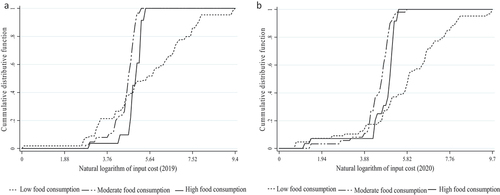

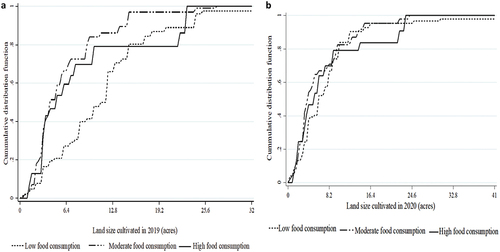

2.2. Dominance and hypothesis tests

This study has adopted cumulative density function curves for validating the presence of first-order stochastic dominance in the distribution of farm sizes and input cost over the study period. The simple first order dominance hypothesis test, therefore, compared degree of dominance in the distribution of farm sizes cultivated and the cost of inputs among the rural farm households across their food consumption status categories of 1. Low food consumption 2. Moderate food consumption and 3. High food consumption using cumulative dominance curves. Thus, one distribution dominates the other at the order n, over the range of if and only if

for

Given that P1 and P2 are the cumulative distribution function of the farm household categories 1 and 2 respectively, and if there is a value of u at which

and that the value of P1 is greater than the value of P2, then none of the distributions completely dominates the others over the interval of

.

2.3. Empirical methods

The paper compares the quantile distributions of differences in farm sizes cultivated over the period of the study. This was based on the distribution of the cumulative function of the dominance curves. We use a quantile regression estimation procedure to investigate the effects of rise in farm input expenditures, farm credits and subsidies among other factors at different points of the average farm size cultivated at the 15th, 50th and the 85th quantiles. Hence, changes in farm sizes (represented by the natural logarithm of average farm sizes) over the study period is the dependent variable.

Further, this study estimates the influence these factors on the food consumption status of the farm households. In this respect, the study took the form of opinion survey based on the rural farm households’ experience of adjusting to food consumption patterns over the study period as follows: 1. Lower food consumption status of the household. 2. Moderate food consumption status and 3. High food consumption status. The expressed experiences by the households as the dependent categorical variables requires an ordered logit model estimation. The reason is that the categories expressed as a dependent variable have been ranked from low through moderate to high in terms of food consumption patterns experienced by the households, particularly during cropping seasons. Hence, the difference between the first and second outcomes might be the same as the difference between the second and third. Thus, an index model for a single latent variable is given by:

Where j = 1, 2 and 3 of the food consumption status categories. Hence, the probability (p) that a farm household could belong to an alternative

is given by

The ordered logit model with alternatives has a set of coefficients with (

intercepts.

With regards to the interpretation of the estimated coefficients, the sign of the parameters shows whether the latent variable increases or otherwise with the independent variables. At the same time, the ordered logit model with

alternatives has

corresponding sets of marginal effects. The marginal effect of an increase in the independent variables

on the probability of a farm household belonging to an alternative

of a food consumption status category could be expressed as

The marginal effects with respect to the explanatory variables means that a unit increase in any of the significant independent variables could lead to an increase or a decrease in the probability of choosing an alternative by the marginal effect expressed as a percentage change. Finally, various statistical tests have been employed to establish significant differences between some variables across the farmer categories classified by their level of food consumption status.

3. Source of data

3.1. Source of data

The study used a data set collected and processed by the Department of Agro Enterprise Development of the Ho technical University, Ghana, The data set is a cross-sectional data set on individual farm households in three (3) regions across southern Ghana. These regions include Greater Accra, Eastern and the Volta. Farm production with respect to main staple food and tree crops have been intensively dominant in the Volta and Eastern regions. The Greater Accra region, on the other hand, serves as the hub of food commodity trade from the two regions, particularly the Eastern. The focus of the study was on these three regions based on this information among others on crop production and farm households estimated population from Ministry of Food and Agriculture of Ghana. The regions were therefore purposively sampled in the first stage due to their diversified crop production per annum in southern Ghana. In the second stage, a simple random sampling technique was used to select 130 rural farm households from each of the 3 sampled regions making a total sample size of 390 households.

We have used the Yamane’s formula, for the sample size determination (Yamane, Citation1967) on the population of 40, 967 farm households. Besides, using a margin of error of e = 5%, we obtained a sample size of 370. Considering the ± 5% level of precision, we have approximated the sample size to 390 rural farm households. The purpose was to accounts for non-response rate and as result, we have randomly selected 130 households from each of the stratified regions. This is to ensure proportional representation of farm households from the three regions. The data was collected using a structured questionnaire and face-to-face interviews. The information collected during the survey include demographic characteristics of the households (e.g. sex, age, household size, literacy level, etc.), farm sizes cultivated and costs of inputs purchased over the two year period (2019 and 2020), main occupation of household members, food consumption pattern over the period, access to farm credits, government subsidies, major external shock at the period (e.g. emergence of COVID−19 pandemic) among other factors.

4. Descriptive statistic results

4.1. Types of crops cultivated by farm sizes over the study period

Table shows the distributions of farm sizes of the major crops produced by the categories of the food consumption statuses of the farm households over the two study periods. The paper has conducted multivariate tests (allowing for homogeneity and heterogeneity, respectively) to test if there is a significant difference between the farm sizes under the main crops cultivated. The results show that, there are significant differences between farm sizes of the tree crops in year 1 of the study period. Likewise, there are significant differences between the farm sizes of the tree crops in the second year of the study, except in the case of mango. Additionally, the rural farm household category that assumes high food consumption status cultivated significantly larger farm sizes under the tree crops (e.g., cocoa and oil palm) and cash crops (e.g., groundnut) than those in the low food consumption category. The reason might be that such farmers generally belong to the high-income group (Dzanku & Tsikata, Citation2022; Giller, Delaune, Silva, Descheemaeker, et al., Citation2021; Singh et al., Citation2021). The implication is that cash crop farmers are better off than food crop farmers in relation to food consumption status.

Table 1. Types of major crops and farm sizes (in acres) cultivated by food consumption status categories of the farm households

The analyses in Table pointed out that the farm size cultivated for cereals (maize and rice) based on food consumption status categories differed significantly during the study periods. Similarly, the farm sizes of the staple food crops (roots, tubers, and plantain), as shown in Table , are significantly distinct from each other. This observation denoted a condition of low food consumption households holding larger farm sizes of staple food crops as high food consumption groups possess larger farm sizes for cash crops. Besides, farm sizes are generally bigger among the high food consumption status of tree crop farmers than the low food consumption household category except for mango, but vice versa for staple crops (cassava, yam, and plantain) and vegetables. The implication might be that low food consumption categories cultivated larger farm sizes of staple food crops than those in higher food consumption categories. This corresponds with the finding that the types of crops produced and farm size allocations by crops might differ between cropping seasons and farm size holdings (Andrieu et al., Citation2021). Hence, low food consumption households might have traded off their food consumption for investing in staple crop farms, unlike those producing cash (tree) crops, that usually belong to higher income groups (Lu and Horlu, Citation2017).

Table 2. Average expenditure on major farm inputs (in Ghana Cedis) by food consumption status categories of the farm households

Concerning legumes (groundnut and cowpea), the results do not show any significant differences in farm sizes cultivated across the categories of food consumption. Besides, farm sizes under the production of vegetables (tomato, okra, and pepper) during year 1, as well as tomato and pepper in year 2, differ significantly across the food consumption categories. Thus, the distributions of the farm sizes per crop cultivated vary across the food consumption categories. Also, on the whole, the findings have rejected the null hypothesis that farm sizes per crop are not significant across the food consumption status categories of rural households. The unequal farm sizes among rural farm households indicate progress toward improving food consumption status (food security) among rural farmers might not be easy to achieve (Lopez-Ridaura et al., Citation2019). Hence, tailored policies that target specific categories should be adopted.

4.2. Major farm input expenditures over the study period

The paper has also investigated whether significant differences exist between farm input expenditures across the household categories based on their food consumption status. These results are in Table . It has been observed from the table that the households with low food consumption status incurred expenditure on farm inputs greater than those belonging to the high food consumption category. This observation is consistent for the study periods (year 1, and year 2). The results, therefore, have failed to reject the null hypothesis that farm input expenditures are inconsistent among the farm households vis a vis their food consumption status. The results have also demonstrated that farm expenditure on inputs has increased during the study period. Though farm input expenditures generally shot up drastically between the study periods, it does not correspond with the changes in farm sizes cultivated by the household categories in Table . This occurrence could be due to some external shocks that could be at play over the study period, in which case, we have considered the emergence of COVID−19, which might be a key influence on the dynamics of inputs expenditures by way of increases in the input prices over the period.

4.3. Types of food consumed by the households over the study period

The distribution of types of food items consumed by rural farm households is presented in Table . We find from the results that, consumption of stable food crops (cereals, roots, tubers, plantains, and bananas) and vegetables are the main items consumed by the households over the two study periods. The highly significant Chi-Square values for cereals, plantain and bananas, fresh fruits, tea and beverages, milk and dairy products, poultry and other meat products adjusted by the Holm Bonferroni p-value, indicates that the consumption of the food items is statistically different among the household categories in year 1 of the study. Likewise, we have observed more statistically significant differences in consumption of all the food items among the household categories in year 2 than in year 1 of the study. The implication is that there were increased gaps in the consumption patterns of the various food items among the households over the two-year study periods.

Table 3. Major food items consumed by the rural farm households over the study period

4.4. Factors of farm sustenance and food consumption

The summary of the descriptive statistics of the variables used in both the quantile and the ordered logistic regressions are presented in Table . The table has indicated that the average number of persons per the farm households is 6 persons and that the natural logarithm of average farm sizes was 1.65. Table has also shown that 54 percent of the households have experienced increases in the farm inputs expenditures and that 18 percent of them have pointed that they had inadequate access to farm labour. In addition, 18 percent of the households have indicated that they had increases in their farm sizes between years 1 and 2 cropping seasons. Meanwhile, 59 percent of the respondents have farming as their primary occupation vis-a-vis nonfarm work as a main work. Besides, 16 and 17 percent of the households considered lack of credit and government subsidies, respectively, to be among the factors that influence changes in their farm sizes cultivated and food consumption status. In terms of external shock that might affect the operations of the farming activities of the households, 40 percent of the respondents have admitted that emergence of COVID−19 have affected their farm operations, hence, likely to have affected changes in their cultivated farm sizes and food consumption status. In all, 47 percent of the farm households cultivated at least one of the tree crops and 23 percent of them receive remittances from their family members.

Table 4. Summary of descriptive statistics of variables used in models

Additionally, the factors of farm sustenance adopted in this study are relevant for the following reasons. Household size could be a primary source of labor and consumption units for rural farmers (Abu & Soom, Citation2016, Lowder et al., Citation2016; Romeo et al., Citation2016; Haq et al., Citation2022). Hence, household size could determine cultivated farm sizes and the food consumption status of the households (Haq et al., Citation2022). Further, expenditures on farm inputs (cost of farm inputs) are essential for the sustenance of farms and food consumption (Adjognon et al., Citation2017; Wossen & Berger, Citation2015). Farm labor also supplements household (family) labor during farm production. The labor supply also contributes to the farm expenditure of the households (Darko et al., Citation2018). Farm labor, therefore, remains a determinant in farm production and food consumption of households (Aryal et al., Citation2021; Unay-Gailhard & Bojnec, Citation2019).

Farm credits and subsidies are also essential for farm financing that support farm expenditure (Anang & Asante, Citation2020). Thus, credits and farm input subsidies are critical for farm sustenance and households’ food consumption (Ndegwa et al., Citation2020; Tadesse & Zewdie, Citation2019). Some past literature has pointed out that if farming is the main occupation of a household, it could be more committed to farm sustenance activities. The implication is that such farm households could have a better food consumption status (Eyasu & Yildiz, Citation2020). Some scholars have also adopted remittances as a source of farm investment and could also be for food consumption of households (Lee & Lee, Citation2021; Moniruzzaman, Citation2022; Veljanoska, Citation2022). Moreover, the types of crops could depend on the farm sizes available to the farmer. Thus, farm size and expenditure requirements for tree (cash) crops differ from food crops (Andrieu et al., Citation2021). The type of crops could determine the income levels of farmers, hence their food consumption levels (Dzanku et al., Citation2021). Lastly, some scholars have indicated that the emergence of COVID−19 affects farm sizes cultivated and farm expenditures. Thus, it could affect the food consumption status of the households (Harris et al., Citation2020; Swinnen & Vos, Citation2021; Weersink et al., Citation2021).

5. Empirical results

5.1. Household categories’ dominance hypothesis tests

In this section, the paper has examined farm size dominance based on the three categories of food consumption status among the rural farm households. These information are contained in Figure for the two study periods, respectively. Although there has not been complete first order stochastic dominance ordering in the cumulative probability distributions over the range of farm sizes, it can be observed that there is greater dominance among the farm households of low food consumption category (Figure ). Thus, whilst the households with low food consumption status have experienced greater dominance in farm sizes, both the high food consumption and moderate food consumption categories generally lack behind. However, the moderate food consumption category has shown the least dominance in farm size ordering over the study period. The implication is that low food consumption household category tends to have more stable farm sizes and food consumption status than the other categories over the study period. Nonetheless, the spread in the farm size distributions has decreased in magnitude in year 2 of the study period, but the trends in dominance basically remain quite stable over the period. Besides, it could be deduced that rural farm households with low food consumption status are more likely to sacrifice food consumption for sustenance of farm sizes than those in the high and moderate food consumption category.

Figure 2. Cumulative distribution of land sizes cultivated in 2019 (year 1). Cumulative distribution of cultivated land sizes in 2020 (year 2).

We have presented the graphical illustration of the first order stochastic dominance test by comparing the plots of the cumulative probabilities of farm inputs costs over the study period (Figure ). The graphical representations have shown that, at some points of the distributions, though the low and high food consumption statuses seem to show some level of dominance, there is no complete dominance in the distributions, particularly at the extreme ends where the curves overlap. Thus, at lower cost range of the distribution, high food consumption status category show some dominance, but as inputs cost increases, low food consumption household category exhibits dominance than the other two categories. This means that rural farm households with low food consumption are more likely to tradeoff their food consumption for spending more on farm inputs than those with high food consumption status category.

5.2. Econometric results

This section presents empirical results on the linkages between farm sizes, farm input expenditures and food consumption status of rural farm households. First, we considered quantile regression results (Table ). The results specifically estimated the models at the 15th, the 50th and the 85th quantiles. The analysis has shown that when a household faces a rise in expenditure on farm inputs, it could lead to a percentage rise in farm sizes. It means that the larger the farm sizes, the more the households spend on required inputs. Hence, the highest impact of farm inputs expenditure at the 85th quantile at a 5 percent significance level. Household sizes exert positive effects on the rate of change in farm sizes across all the quantiles, but the largest effects are experienced at the lower (15th) quantile and among the relatively small farm size holders. On the contrary, lack of access to farm labour impacts negatively on the rate of change in farm sizes at the 85th quantile (among relatively larger farm size holders) only. Also, lack of government subsidies could exert a positive impact on farm sizes only at the lowest (15th) quantile, and even though it exerts a negative impact for higher quantiles (50th and 85th quantiles) the effects are not significant.

Table 5. Quantile regression of factors affecting variations in farm sizes

Moreover, having farming as the main occupation of the farm households affects the rate of change in farm sizes positively than those with nonfarm work as their main occupation. This impact is largest at the 85th quantile (among bigger farm-size holders). The results in Table have also indicated that receipt of remittance influences farm sizes positively at the 15th and 50th quantiles, but the impact at the lower quantile is greater. The implication is that smaller farm holders are more dependent on remittance for farm-size sustenance than the bigger farm-size holders. The results have also indicated that the cultivation of tree (high-value) crops has a higher positive impact on farm sizes than cultivating food crops, and the effects are greater at the 85th quantile but have no significant impact at the 15th quantile. Lastly, based on the results in Table , it has been observed that the emergence of COVID−19 has positive effects on farm sizes cultivated at both 15th and the 85th quantiles, but a greater effect is observed at the 85th quantile (among large farm holders). However, the effect of the pandemic varies significantly across the quantiles. This finding is similar to the earlier assertion by some scholars that farm sizes have increased in northern Ghana, particularly for Soybeans production, as a result of COVID−19 awareness creation in the country (Martey et al., Citation2021). Further, some scholars have indicated that the emergence of COVID−19 affects farm sizes cultivated (Harris et al., Citation2020; Swinnen & Vos, Citation2021; Weersink et al., Citation2021).

Next, in order to examine the effect of farm sizes and other factors on the food consumption status of the rural farm households, ordered logistic regression approach was adopted. Thus, the dependent variable is a categorical variable denoted as follows: 1. Low food consumption status; 2. Moderate food consumption status; 3. High food consumption status. Table presents both ordered logistic model and the corresponding marginal effects on the respective components of the categorical dependent variable. The results have shown a linkage between food consumption status, farm inputs expenditures and farm sizes cultivated among other factors.

Table 6. Ordered logit model of factors determining food consumption status of the households

We first consider the coefficients in Table . The results show that the food consumption status of the households could be better (from low to moderate or to high) with low expenditure on farm inputs. Households’ food consumption could also be better if household sizes are low. This observation is similar to the findings of Haq et al. (Citation2022) that sizes of rural households play essential role in their food and nutrition security. Also, access to farm labour, credit and government subsidies could improve farm households food consumption status. The results also show that food consumption will be better if remittances are lower than required for investing in their farms. Further, the households’ food consumption could improve if farming is the main work of the household members and there is a rise in farm sizes. Besides, food consumption could be better when there are COVID−19 restrictions and households stay more at home. Some scholars have indicated that the emergence of COVID−19 affects farm expenditures. Thus, it affected food consumption status of the households (Swinnen & Vos, Citation2021; Weersink et al., Citation2021).

Second, we consider the marginal effects results. The marginal effects results show an increase in the expenditure of farm inputs the farm households are 19 percentage points more likely to be in the low food consumption category. At the same time, the households are 5 and 14 percentage points less likely to fall into the moderate and high food consumption categories, respectively. The implication is that increases in farm input expenditures generally induce a rise in low food consumption status but reduces moderate food consumption and high food consumption status among farm households. This scenario indicates that farm households are trading off their food consumption resources to sustain their farm input expenditures and farm sizes, as indicated by some past studies on the issues (Lopez-Ridaura et al., Citation2018; Perez et al., Citation2015). In such cases, if a farm household increases spending on farm inputs could imply a reduction in food consumption, at least during planting season, to sustain their food consumption status in the future. Thus, the household might inter-temporarily lessen their food consumption by increasing farm input expenditures on farm sustenance and crop production to sustain their level of food consumption in the future (Ecker & Hatzenbuehler, Citation2022).

Additionally, a unit rise in household size is associated with 3 percentage points more likely to be in the low food consumption status, 1 percentage points less likely to belong to moderate food consumption status and 2 percentage points less likely to be in the high food consumption status. Likewise, lack of access to farm labour could imply 21 percentage points more likely to be in low food consumption status. At the same time, it is associated with 5 and 15 percentage points less likely to belong to moderate and high consumption categories, respectively. Similarly, lack of access to farm credit is associated with 18 percentage points more likely to belong to low food consumption status, 4 percentage points less likely to be in the moderate food consumption category and 13 percentage points less likely to fall into the high food consumption category. This supports a finding by Bidisha et al. (Citation2017) that access to credit improves food security and dietary diversity among rural households. The table has also pointed out that lack of government subsidies is associated with an 18 percent likelihood of households belonging to low food consumption status. Meanwhile, there is 5 and 14 percentage points less chance of being associated with moderate food consumption and high food consumption status, respectively. The findings of some other scholars that investment in farm production, is dependent on farm sizes and input expenditures. It could also be influenced by other factors including, lack of farm labour, credits and subsidies, among others, that are linked with a farm household’s food consumption pattern (Ngema et al., Citation2018; Samberg et al., Citation2016; Wossen et al., Citation2018).

In cases where the households have farming as their main occupation other than nonfarm work, they are associated with a 24 percentage points less chance of belonging to low food consumption status. However, there is a 6 percentage points more likelihood of farm households belonging to the moderate food consumption category and 18 percent more likely of adjoining the high food consumption status. Hence, having farming as the main occupation improves the food consumption status of rural farm households in southern Ghana. Further, a rise in farm sizes could imply 13 percentage points less likely to be associated with low food consumption status. A rise in farm sizes also imply 3 percentage points more likelihood of being associated with the moderate food consumption and 10 percentage points more likely to fall into the status of high food consumption. This finding agrees with some previous studies that in a developing country like Ghana, agricultural policies affecting food production and food security of rural farm households are significantly dependent on farm sizes cultivated (Lu & Horlu, Citation2019). Additionally, households receiving remittances are 8 percentage points more likely to be associated with low food consumption status but 6 percentage points less likely to belong to high food consumption status.

With respect to the emergence of COVID−19 pandemic during the course of the study, we have observed that it induces 17 percentage points less likelihood to be associated with low food consumption status, it has 4 and 12 percentage points more likelihood for greater associations with the moderate and high food consumption statuses respectively. More so, on the whole, the results have proven that the farm households had increases in food consumption pattern due to the pandemic as asserted by some other scholars with reference to other parts of Africa (Devereux et al., Citation2020).

6. Conclusion and policy implications

We have found that the distribution of cultivated farm sizes per crop and farm input expenditures significantly vary among the food consumption status categories of the households. However, the input expenditures do not correspond with changes in farm sizes over the study periods. Further, significant differences exist in the major food items consumed by the households. These results have pointed out that blanket policies for the sustenance of farm production and food consumption might not be appropriate. We, therefore, advocate for tailored policies that target specific households with respect to farm sizes and food consumption status that should be adopted.

Further, we observed no complete dominance in the distributions of food consumption status and farm input expenditures on cultivated farm sizes. This suggests that not every household in each food consumption category whose farm size is small or large is inferior or superior in food consumption status to the others. However, farm households in the low food consumption status category have shown consistent dominance at the upper end of the distributions. Consequently, farmers with large farm sizes might be allocating their resources to sustaining their farm sizes which might influence their food consumption. The large-scale farmers, therefore, might need farm credits and subsidies more than smallholder farmers to sustain or improve their food consumption status.

Besides, limited subsidies exert an increasing impact on the farm sizes of the smallholders. At the same time, remittances exert positive effects on cultivated farm sizes. Contrarily, lack of farm labor induces a reduction effect on farm size sustenance, particularly among large-holder farmers. It requires specific policies that meet the needs of smallholders and large farm owners separately. Additionally, tree crop cultivation implies having large farm sizes compared to food crop cultivation. The implication is that types of crops could determine the land size under cultivation. Thus, crop-specific policy formulation and implementation are necessary for farm sustenance. It, therefore, might require tailored policies on farm size allocations to staple food and cash (tree) crop cultivation.

Further, the results show that the food consumption status of the households could be better with low expenditure on farm inputs. Households’ food consumption could also improve if household sizes are small and also when there are enough farm labour, farm credit and subsidies. The findings also point out that food consumption is better if remittances are lower than required for investing in their farms and if farming is the main work of the household and if farm sizes increase. Besides, food consumption could be better when there is COVID−19 restrictions and the households stay more at home. The results also show that a rise in input expenditure reduced food consumption of the households. Additionally, lack of farm labour, credits and subsidies induce reduction in food consumption of the households. Likewise, households with farming as their main occupation have food consumption level increased than having nonfarm work as a primary occupation. Hence, the study recommends specific policy support for farm credit, subsidies and incentives for farm labour to enhance farm size sustenance and improving food consumption status of farm households.

7. Limitations of the study

This study has a few limitations. They comprise the limited time dedicated to data collection over 2 to this study. Exasperatingly, the COVID−19 outbreak and accompanying restrictions have also distorted data collection procedures. Further, related literature on the topic of the study area is limited. Also, the study is limited to a few districts in three regions in southern Ghana. Hence, the findings generally represent only the southern part of the country. The analyses of the study are therefore limited to the rural south of Ghana. Additionally, financial constraints and the busy schedule of most research team members were some challenges and delays in executing the data collection and analysis protocols. Despite the above-stated limitations, they do not compromise the data collected, the analytical results, and the findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Godwin Seyram Agbemavor Horlu

Godwin Seyram Agbemavor Horlu obtained his PhD in Agricultural Economics and Management from the School of Management, Zhejiang University, China, where he specialised in agricultural and development economics. He obtained M.Phil. in Agricultural Economics from the University of Ghana. Godwin is a researcher and has research interests in rural economic development, environmental and natural resource economics, transition of farm lands, livelihoods, poverty and economic inequality among rural households As well, he a keen interest in agricultural development policies, monitoring and evaluation of development projects. He has published in reputable journals. He currently teaches various courses and supervises students’ dissertations in the Department of Agricultural Sciences and Technology at the Ho Technical University, Ghana.

Kenneth Fafa Egbadzor

Dr. Kenneth Fafa Egbadzor is a Senior Lecturer and the current Head of the Department of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Ho Technical University (HTU). He is also the Vice Dean for the Faculty of Applied Sciences and Technology (FAST). Dr. Egbadzor obtained his PhD in Plant Breeding from the West Africa Centre for Crop Improvement, University of Ghana in June, 2014. He holds MPhil Crop Science (June, 2009) and Bsc. Agriculture (June, 1999) from the University of Ghana and Post Graduate Diploma in Education from the University of Cape Coast (July, 2004). He did his National Service at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Plant Genetic Resources Research Institute (CSIR-PGRRI), Bunso in the Eastern Region during 1999/2000 service year. Dr Egbadzor had trainings in fields related to crop improvement from international centres of excellence such as ICRISAT in India, Sfax in Tunisia and Kew in the UK. His research covers a number of crops, both cultivated and crop wild relatives including shallot (Allium cepa var aggregatum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), wild rice (Oryza species), Cassava (Manihot esculentum), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), citrus (citrus species) and currently, focused on baobab (Adansonia digitata).Dr. Egbadzor had worked with the CSIR-PGRRI, Bunso from 2008 as a Research Scientist and rose to the rank of Senior Research Scientist in 2016. He had also worked as a tutor with the Ghana Education Service from 2002 to 2007. Dr. Egbadzor has attended and presented papers at a number of academic conferences and has over 26 publications to his credit as journal articles, book chapters, and conference proceedings. Dr. Egbadzor’s research has been of interest globally. His work is attracting collaboration within and outside Ghana. He has been engaged by FARA (Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa) as a Think-Tank on under-utilized crops. At Applied Research Conference for Technical Universities of Ghana in 2022, his presentation won the best poster. He is currently leading a project on sanitation and agro-forestry with baobab in the Volta region.

Jones Akuaku

Dr. Jones Akuaku is a Lecturer at the Department of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of the Ho Technical University, Ghana. He obtained his PhD Agricultural Sciences (Agronomy) from Sumy National Agrarian University (Ukraine). Earlier, he obtained his MPhil Crop Science and BSc Agriculture from the University of Ghana. Dr. Akuaku current research focuses on domesticating “Africa’s favourite tree”, the baobab, and its related food and nutritional benefits. He also has special interest in applying eco-friendly and inexpensive climate-smart strategies that will increase yield and quality of crops. Jones has participated in a number of international conferences and has a number of publications to his credit.

Notes

1. F-statistics of multivariate (Pillai’s trace)test allowing for homogeneity.

2. Chi-square value of multivariate test, allowing for heterogeneity.

3. F-statistics of multivariate (Pillai’s trace)test allowing for homogeneity.

4. Chi-square value of multivariate test, allowing for heterogeneity.

5. Chi squared value adjusted by Holm Bonferroni probability for multiple responses.

6. Chi squared value adjusted by Holm Bonferroni probability for multiple responses.

References

- Abu, G. A., & Soom, A. (2016). Analysis of factors affecting food security in rural and urban farming households of Benue State, Nigeria. International Journal of Food and Agricultural Economics (IJFAEC), 4(1128–2016–92107), 55–21. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.231375

- Adjognon, S. G., Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. O., & Reardon, T. A. (2017). Agricultural input credit in Sub-Saharan Africa: Telling myth from facts. Food Policy, 67, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.014

- Ahmed, U. I., Ying, L., Bashir, M. K., Abid, M., Zulfiqar, F., & Mertens, F. (2017). Status and determinants of small farming households’ food security and role of market access in enhancing food security in rural Pakistan. PloS One, 12(10), e0185466. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185466

- Anang, B. T., & Asante, B. O. (2020). Farm household access to agricultural services in northern Ghana. Heliyon, 6(11), e05517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05517

- Andrieu, N., Hossard, L., Graveline, N., Dugué, P., Guerra, P., & Chirinda, N. (2021). Covid-19 management by farmers and policymakers in Burkina Faso, Colombia and France: Lessons for climate action. Agricultural Systems, 190, 103092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103092

- Aryal, J. P., Simtowe, G., Thapa, F., & Simtowe, F. (2021). Mechanisation of small-scale farms in South Asia: Empirical evidence derived from farm households survey. Technology in Society, 65, 101591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101591

- Atube, F., Malinga, G. M., Nyeko, M., Okello, D. M., Alarakol, S. P., & Okello-Uma, I. (2021). Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adaptation strategies to the effects of climate change: Evidence from northern Uganda. Agriculture & Food Security, 10(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-020-00279-1

- Aweke, C. S., Lahiff, E., & Hassen, J. Y. (2020). The contribution of agriculture to household dietary diversity: Evidence from smallholders in East Hararghe, Ethiopia. Food Security, 12(3), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01027-w

- Bidisha, S. H., Khan, A., Imran, K., Khondker, B. H., & Suhrawardy, G. M. (2017). Role of credit in food security and dietary diversity in Bangladesh. Economic Analysis and Policy, 53, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2016.10.004

- Darko, F. A., Palacios-Lopez, A., Kilic, T., & Ricker-Gilbert, J. (2018). Micro-level welfare impacts of agricultural productivity: Evidence from rural Malawi. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(5), 915–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1430771

- Devereux, S., Béné, C., & Hoddinott, J. (2020). Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Security, 12(4), 769–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0

- Dzanku, F. M. (2019). Food security in rural sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the nexus between gender, geography and off-farm employment. World Development, 113, 26–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.017

- Dzanku, F. M., & Tsikata, D. (2022). Gender, agricultural commercialization, and food security in Ghana. In Agricultural commercialization, gender equality and the right to food (pp. 48–72). Routledge.

- Dzanku, F. M., Tsikata, D., & Ankrah, D. A. (2021). The gender and geography of agricultural commercialisation: What implications for the food security of Ghana’s smallholder farmers? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 48(7), 1507–1536. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1945584

- Ecker, O., & Hatzenbuehler, P. L. (2022). Food consumption–production response to agricultural policy and macroeconomic change in Nigeria. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 44(2), 982–1002. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13161

- Eyasu, A. M., & Yildiz, F. (2020). Determinants of poverty in rural households: Evidence from North-Western Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1823652. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1823652

- Fahey, C. A., Chevrier, J., Crause, M., Obida, M., Bornman, R., Eskenazi, B., & Farias, D. (2019). Seasonality of antenatal care attendance, maternal dietary intake, and fetal growth in the VHEMBE birth cohort, South Africa. PloS One, 14(9), e0222888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222888

- Gautier, D., Denis, D., & Locatelli, B. (2016). Impacts of drought and responses of rural populations in West Africa: A systematic review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(5), 666–681. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.411

- Giller, K. E. (2020). The food security conundrum of sub-Saharan Africa. Global Food Security, 26, 100431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100431

- Giller, K. E., Delaune, T., Silva, J. V., Descheemaeker, K., van de Ven, G., Schut, A. G., van Wijk, M., Hammond, J., Hochman, Z., Taulya, G., Chikowo, R., Narayanan, S., Kishore, A., Bresciani, F., Teixeira, H. M., Andersson, J. A., & van Ittersum, M. K. (2021). The future of farming: Who will produce our food? Food Security, 13(5), 1073–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01184-6

- Haq, S. U., Shahbaz, P., Abbas, A., Batool, Z., Alotaibi, B. A., & Traore, A. (2022). Tackling food and nutrition insecurity among rural inhabitants: Role of household-level strategies with a focus on value addition, diversification and female participation. Land, 11(2), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020254

- Harris, J., Depenbusch, L., Pal, A. A., Nair, R. M., & Ramasamy, S. (2020). Food system disruption: Initial livelihood and dietary effects of COVID-19 on vegetable producers in India. Food Security, 12(4), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01064-5

- Kuwornu, J. K., Osei, E., Osei-Asare, Y. B., & Porgo, M. (2018). Off-farm work and food security status of farming households in Ghana. Development in Practice, 28(6), 724–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1476466

- Lee, Y. F., & Lee, Y.-F. (2021). Domestic remittances and household food diversity in Rural Ghana. Journal of Social Economics Research, 8(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.35.2021.81.50.65

- Li, M., Fu, Q., Singh, V. P., Liu, D., Li, T., & Li, J. (2020). Sustainable management of land, water, and fertilizer for rice production considering footprint family assessment in a random environment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120785

- Lopez-Ridaura, S., Barba-Escoto, L., Reyna, C., Hellin, J., Gerard, B., & van Wijk, M. (2019). Food security and agriculture in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Food Security, 11(4), 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00940-z

- Lopez-Ridaura, S., Frelat, R., van Wijk, M. T., Valbuena, D., Krupnik, T. J., & Jat, M. L. (2018). Climate smart agriculture, farm household typologies and food security: An ex-ante assessment from Eastern India. Agricultural Systems, 159, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.09.007

- Lowder, S. K., Skoet, J., & Raney, T. (2016). The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Development, 87, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.041

- Lu, W., & Horlu, G. S. A. (2017). Economic well-being of rural farm households in Ghana: A perspective of inequality and polarisation. Journal of Rural Studies, 55, 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.013

- Lu, W., & Horlu, G. S. A. K. (2019). Transition of small farms in Ghana: Perspectives of farm heritage, employment and networks. Land Use Policy, 81, 434–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.048

- Mamiit, R. J., Gray, S., & Yanagida, J. (2021). Characterizing farm-level social relations’ influence on sustainable food production. Journal of Rural Studies, 86, 566–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.07.014

- Martey, E., Goldsmith, P., & Etwire, P. M. (2021). Farmers’ response to COVID-19 disruptions in the food systems in Ghana: The case of cropland allocation decision. AgriRxiv. https://doi.org/10.31220/agriRxiv.2021.00032

- Meyfroidt, P. (2018). Trade-offs between environment and livelihoods: Bridging the global land use and food security discussions. Global Food Security, 16, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.08.001

- Moniruzzaman, M. (2022). The Impact of remittances on household food security: Evidence from a survey in Bangladesh. Migration and Development, 11(3), 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1787097

- Ndegwa, M. K., Shee, A., Turvey, C. G., & You, L. (2020). Uptake of insurance-embedded credit in presence of credit rationing: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Kenya. Agricultural Finance Review, 80(5), 745–766. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-10-2019-0116

- Ngema, P. Z., Sibanda, M., & Musemwa, L. (2018). Household food security status and its determinants in Maphumulo local municipality, South Africa. Sustainability, 10(9), 3307. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093307

- Ogunniyi, A. I., Omotoso, S. O., Salman, K. K., Omotayo, A. O., Olagunju, K. O., & Aremu, A. O. (2021). Socio-economic drivers of food security among rural households in Nigeria: Evidence from smallholder maize farmers. Social Indicators Research, 155(2), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02590-7

- Owusu, V., Abdulai, A., & Abdul-Rahman, S. (2011). Non-farm work and food security among farm households in Northern Ghana. Food Policy, 36(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.09.002

- Pauw, K. (2022). A review of Ghana’s planting for food and jobs program: Implementation, impacts, benefits, and costs. Food Security, 14(5), 1321–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-022-01287-8

- Perez, C., Jones, E. M., Kristjanson, P., Cramer, L., Thornton, P. K., Förch, W., & Barahona, C. A. (2015). How resilient are farming households and communities to a changing climate in Africa? A gender-based perspective. Global Environmental Change, 34, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.06.003

- Rammohan, A., & Pritchard, B. (2014). The role of landholding as a determinant of food and nutrition insecurity in rural Myanmar. World Development, 64, 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.029

- Ren, C., Liu, S., Van Grinsven, H., Reis, S., Jin, S., Liu, H., & Gu, B. (2019). The impact of farm size on agricultural sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 220, 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.151

- Romeo, A., Meerman, J., Demeke, M., Scognamillo, A., & Asfaw, S. (2016). Linking farm diversification to household diet diversification: Evidence from a sample of Kenyan ultra-poor farmers. Food Security, 8, 1069–1085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-016-0617-3

- Samberg, L. H., Gerber, J. S., Ramankutty, N., Herrero, M., & West, P. C. (2016). Subnational distribution of average farm size and smallholder contributions to global food production. Environmental Research Letters, 11(12), 124010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/12/124010

- Schmidt, T., Cloete, A., Davids, A., Makola, L., Zondi, N., & Jantjies, M. (2020). Myths, misconceptions, othering and stigmatizing responses to Covid-19 in South Africa: A rapid qualitative assessment. PLos One, 15(12), e0244420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244420

- Sen, B., Dorosh, P., & Ahmed, M. (2021). Moving out of agriculture in Bangladesh: The role of farm, non-farm and mixed households. World Development, 144, 105479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105479

- Shukla, S., Husak, G., Turner, W., Davenport, F., Funk, C., Harrison, L., Krell, N., & Chemura, A. (2021). A slow rainy season onset is a reliable harbinger of drought in most food insecure regions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Plos One, 16(1), e0242883. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242883

- Singh, K., Fuentes, I., Fidelis, C., Yinil, D., Sanderson, T., Snoeck, D., Minasny, B., & Field, D. J. (2021). Cocoa suitability mapping using multi-criteria decision making: An agile step towards soil security. Soil Security, 5, 100019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soisec.2021.100019

- Smale, M., Thériault, V., & Mason, N. M. (2020). Does subsidizing fertilizer contribute to the diet quality of farm women? Evidence from rural Mali. Food Security, 12(6), 1407–1424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01097-w

- Swinnen, J., & Vos, R. (2021). COVID‐19 and impacts on global food systems and household welfare: Introduction to a special issue. Agricultural Economics, 52(3), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12623

- Tadesse, G., & Zewdie, T. (2019). Grants vs. credits for improving the livelihoods of ultra-poor: Evidence from Ethiopia. World Development, 113, 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.09.009

- Takeshima, H., & Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. O. (2015). Fertilizer subsidies, political influence and local food prices in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Nigeria. Food Policy, 54, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.04.003

- Tan, C. M., & Thamarapani, D. (2019). The impact of sustained attention on labor market outcomes: The case of Ghana. Review of Development Economics, 23(1), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12553

- Tibesigwa, B., & Visser, M. (2016). Assessing gender inequality in food security among small-holder farm households in urban and rural South Africa. World Development, 88, 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.07.008

- Umar, B. B. (2014). A critical review and re-assessment of theories of smallholder decision-making: A case of conservation agriculture households, Zambia. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 29(3), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170513000148

- Unay-Gailhard, İ., & Bojnec, Š. (2019). The impact of green economy measures on rural employment: Green jobs in farms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 208, 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.160

- Veljanoska, S. (2022). Do remittances promote fertilizer use? The case of Ugandan farmers. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 104(1), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12214

- Weersink, A., von Massow, M., Bannon, N., Ifft, J., Maples, J., McEwan, K., McKendree, M. G. S., Nicholson, C., Novakovic, A., Rangarajan, A., Richards, T., Rickard, B., Rude, J., Schipanski, M., Schnitkey, G., Schulz, L., Schuurman, D., Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K., Stephenson, M., & Thompson, J.… Wood, K. (2021). COVID-19 and the agri-food system in the United States and Canada. Agricultural Systems, 188, 103039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103039

- Wijesinha-Bettoni, R., Kennedy, G., Dirorimwe, C., & Muehlhoff, E. (2013). Considering seasonal variations in food availability and caring capacity when planning complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. International Journal of Child Health and Nutrition, 2(4), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-4247.2013.02.04.7

- Wossen, T., & Berger, T. (2015). Climate variability, food security and poverty: Agent-based assessment of policy options for farm households in Northern Ghana. Environmental Science & Policy, 47, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.11.009

- Wossen, T., Berger, T., Haile, M. G., & Troost, C. (2018). Impacts of climate variability and food price volatility on household income and food security of farm households in East and West Africa. Agricultural Systems, 163, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.02.006

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics. An Introductory Analysis (second ed.). Harper and Row. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajcm.2017.71002