?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The growing exports of European dairy products to West Africa is globally raising concerns with regard to its role in the retarded growth of the local milk sector in recipient nations. The impact of such imports on the local milk value chain and the competitiveness of local products have been extensively researched. However, the demand side, specifically consumer perceptions and preferences has been largely neglected. This study therefore focuses on identifying consumer perceptions, preferences, and attitudes in this context. Specifically, the study identifies factors influencing the choice of dairy products from local, domestic, and imported origins with data gathered from 312 and 532 households in Ghana and Senegal respectively. Focusing on yoghurt as the sole product coming from these three origins, we find a differing influence of consumer attitudes and perceptions on consumption frequencies. Although ethnocentric attitudes were exhibited, it did not limit purchases to local yoghurts, contrasting existing literature. Purchase decision as we find is largely influenced by product availability encouraging the consumption of domestic and imported products. Considering the crucial role of imported dairy products in ensuring a reliable access to affordable dairy products in developing countries, their imports are important.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The end of the European Union’s milk production quotas in Citation2015 coupled with other factors in the global milk market such as favourable prices has resulted in an expansion in the operations of European dairy companies in developing nations, particularly in West Africa (Orasmaa et al., Citation2016). The fast-growing dairy sector in this region makes it one of the most important among other sectors. Products including cheese, ultra-pasteurized milk, evaporated milk, ice creams, yoghurts, and milk powder are imported (Zamani et al., Citation2021). Besides, the processing industry that relies on milk powder has seen a significant growth over the last two decades (Corniaux, Citation2018; Oppong-Apane, Citation2016) and an increase is expected in consumer preferences for more diversified dairy products implying further growth of the sector (e.g. Boimah et al., Citation2021; Broutin et al., Citation2018). Milk and milk products are generally an important source of protein in West Africa, where diets are mainly based on staples such as grains, cereals, roots and tubers (Molina-Flores et al., Citation2020). In contrast, local milk production in these developing nations grew only slightly or even remained stagnant over the years (Zamani et al., Citation2021). The poor state of the milk sector in these nations has drawn the attention of some international organizations and civil society activists who have associated the retarded growth of local milk production and its processing to the operations of European dairies in the region (e.g., Broutin et al., Citation2018; Magnani et al., Citation2019; Orasmaa et al., Citation2016).

Researchers over the years have also placed emphasis on analyzing the dairy value chains in West Africa such as Boimah et al. (Citation2021), Guri et al. (Citation2018) and Oppong-Apane (Citation2016) in Ghana; Corniaux (Citation2018) in Senegal; Corniaux (Citation2017) in Burkina Faso; Corniaux and Duteurtre (Citation2014) and Duteurtre and Corniaux (Citation2013) in West Africa. In their studies, several constraints and challenges of the local milk production and processing sectors are identified, which indicate that the supply of the countries with dairy products will not be possible in the future without imported milk. The studies so far have neglected consumers who are located far downstream the value chain but who play a critical role in the success of actors upstream, particularly in the case of the local dairy value chains.

Food choice is a routine activity for most individuals and is driven by socio-economic factors such as income, age and gender. More so, it is influenced by additional factors of consumers’ food environment and the whole food system (H. Bytyqi et al., Citation2008; Colonna et al., Citation2011; Forbes-Brown et al., Citation2015; Johansen et al., Citation2011; Krešić et al., Citation2010; Rani, Citation2014). In West Africa, dairy consumption is diversified with a more or less segmented market with three different origins of products; (i) those made from fresh local milk, (ii) domestically processed products from imported milk powder, and (iii) imported products. In view of the growing criticisms of European dairy exports to West Africa, the overall aim is to analyze consumption habits with respect to the three different types of dairy products and compare these behaviour as well as their determinants. Precisely, we intend to find answers to the following questions: (1) how often are dairy products generally consumed and what determines this frequency? (2) What influence does origin have on the consumption of dairy products? and (3) Are there differences in the behaviour of consumers in different countries? We consider Ghana and Senegal, two West African countries with high volumes of import and processing, as our case study countries. We chose two countries because according to Gedikoglu and Parcell (Citation2014), geographical locations potentially can influence a variation in consumer behaviour (perceptions and preferences). This implies that the same product can be perceived differently by consumers in two different locations due to different cultures and habits. Furthermore, we focus the analysis on yoghurt because in both countries it is the main dairy product with three origins, i.e., it is produced with local milk and thus referred to as local yoghurt, processed domestically with imported milk powder designated as domestic yoghurt or is purely imported thereby known as imported yoghurt.

In the first stage of our analysis, we identify the frequency at which yoghurt, in general, is consumed in these two countries and the factors that subsequently determine these consumption rates. To verify the influence of origin on consumer behaviour, in the second stage, we identify not only socio-demographic characteristics but also consumer attitudes and perceptions that determine the consumption of local, domestic, and imported yoghurts. Moreover, we assess the results from the two countries to see if notable differences exist in consumer behaviour towards local, domestic, and imported yoghurts. We believe the results will serve as a useful evidence to guide the debate on the importance of product origin to consumers and the role of dairy imports in developing economies.

2. Influence of origin on consumer behaviour: A review

Global commerce continually exposes consumers worldwide to products from varied origins thus increasing the complexity of the process of decision making. Due to this, researchers over the years have focused on identifying factors that drive consumers in the process of decision making. As literature reveals, consumer behaviour is a multi-cue process, meaning it is influenced by several factors including intrinsic and extrinsic factors of the product in question, factors specific to the decision maker (e.g., knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes), culture, and geographic location (Bagga & Bhatt, Citation2013; Forbes-Brown et al., Citation2015; Sama, Citation2019; Shepherd, Citation2001). However, one factor which is drawing the attention of researchers is the concept of Country of Origin (COO) on consumer behaviour, referred to as the country-of-origin effect (Schnettler et al., Citation2008).

Schooler (Citation1965) carried out the first empirical test to ascertain the influence of COO on consumers’ perceptions and attitudes towards products, thereby laying the foundation for studies in the field of international marketing. The country-of-origin phenomenon (Schooler, Citation1965) dwells on the assumption that consumer decision making is a cognitive process based on a consumer’s reliance on a host of information cues used in his/her purchase decisions. Obermiller and Spangenberg (Citation1989) further identifies three different effects of the country-of-origin cue—affective, normative, and cognitive. According to Han (Citation1989) the country image may become a construct which summarizes one’s beliefs about a product’s attributes which can have a direct effect on his/her attitude towards the brand. The affective effect describes the COO cue as an attribute that links a product to symbolic and emotional values. This includes national pride and social status which triggers an emotional response and hence a consumer’s purchase decision. Ethnocentricity/ethnocentrism is relevant to the affective aspect, especially when this factor is triggered by consumers’ pride in their local products. Ethnocentricity is therefore one of the most relevant and interesting aspects of COO and is identified as an important factor that drives consumer perceptions (e.g., Abdalrahman et al., Citation2018; Makanyeza & Du Toit, Citation2017; Nadiri & Tümer, Citation2010). As a concept, ethnocentrism is viewed as the tendency to regard the standards, beliefs, and code of behaviour of one’s “own” as superior to those found in other societies (Nadiri & Tümer, Citation2010).

In terms of the normative effect, the COO cue generates moral reflections which guide consumers’ behavioural intentions. In this case, COO reveals an influence on preferences without a change in overall evaluation or attitude towards a product (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1977). Thus, the COO of a product is seen as intervening between a consumer’s evaluation and behavioral intentions. Consumers object to imported goods because they consider them as the major cause of unemployment (Shimp & Sharma, Citation1987). This reason for rejecting imported goods is relevant to the normative aspect, as consumers may see avoiding being “harmful to local economies” as a type of social norm.

For the cognitive effect, COO does not have a direct effect on a consumer’s evaluation. However, it is used as a reference to infer some other attributes such as product quality that determines their overall attitude. Bilkey and Nes (Citation1982) and Obermiller and Spangenberg (Citation1989) identify the cognitive effect as the most frequent in consumers evaluation of products. As Shimp and Sharma (Citation1987) notes, ethnocentric consumers object to imported goods because they perceive them as inferior to local goods which is relevant to the cognitive aspect of the influence of COO on consumers’ behaviour.

Many studies have shown that ethnocentric consumers are more likely to purchase local foods compared to the purchase of imported ones (e.g., Blazquez-Resino et al., Citation2021; Miguel et al., Citation2022; Schnettler et al., Citation2011, Citation2017). This higher tendency to opt for local products is noted to be related more to consumers’ superior evaluation of local goods over the imported versions (e.g., Blazquez-Resino et al., Citation2021; Bruwer et al., Citation2023; Kilders et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, Sharma et al. (Citation1995) have also identified those group of consumers on the other side who do not care about the origin of products they consume (i.e., whether domestic or imported). In this instance, factors other than ethnocentrism could explain the underlying purchase and consumption behaviour of consumers. As Yang et al. (Citation2022) also point out in their study, the importance of country-of-origin in evaluating dairy products is not necessarily driven by consumer ethnocentrism. However, it is noted that higher levels of consumer ethnocentrism is associated with the importance of country-of-origin in product evaluation only where purchase frequencies are higher.

Several authors have explored the significance of product origin on consumer valuation of product attributes and differentiation (e.g., Abraham & Patro, Citation2014; Berbel-Pineda et al., Citation2018; Nguyen & Alcantara, Citation2022; Norris & Cranfield, Citation2019; Profeta et al., Citation2012). Others such as Balcombe et al. (Citation2016), Kaya (Citation2016), Sckokai et al. (Citation2014), Abraham and Patro (Citation2014), and Holdershaw et al. (Citation2013) have likewise demonstrated the importance of product origin as an important extrinsic credence attribute influencing consumer perceptions. Origin can affect consumer valuation of attributes such as taste and safety (Barbarossa et al., Citation2016; Rezvani et al., Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2018). However, Gedikoglu and Parcell (Citation2014), Rani (Citation2014), Profeta (Citation2008) and Block and Roering (Citation1976) have found that the extent to which “origin” influences consumer purchases depends not only on intrinsic factors but also on extrinsic factors including socio-demographic characteristics, geographic and cultural variations. For instance, origin as an indicator of food quality (Holdershaw et al., Citation2013) is found to be more pronounced among consumers in developing countries (Chung Lo et al., Citation2017; Clipa et al., Citation2017; Makanyeza & Du Toit, Citation2017; Wang & Heitmeyer, Citation2006; Xu et al., Citation2020) than in the developed world where products originating from the west are mostly considered as superior to local products.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data

The study dwelt on primary data collected in March 2021 in Ghana and from January to February 2022 in Senegal. The survey periods are almost a year apart due to the situation of the coronavirus pandemic in the latter country. In Ghana, we conducted the survey in Accra, Kumasi and Tamale, while in Senegal we chose Dakar, Thiès and Kolda. We selected these cities because they are highly urbanised, ethnically diverse and have high pattern of dairy consumption. Moreover, these cities are found in regions—Greater-Accra, Ashanti, and Northern (Ghana) and Dakar, Thiès and Kolda (Senegal)—where many dairy farms are located.

A multistage sampling procedure was used in gathering the data. First, three districts were randomly chosen from each city, while a community each was randomly chosen from the selected districts in the second stage. The third stage involved a random selection of dairy consuming households. To select a household, we used a random walk procedure, interviewing respondents from every third household along the route. If a respondent in a target household did not consume milk, was unavailable (after two visits) or was not interested in participating, the next household was selected. The study targeted consumers of dairy products who were responsible for purchasing or making purchase decisions in the household and were aged 18 years or older. In all, 312 and 532 households were interviewed in Ghana and Senegal respectively. The sample size considerations were based on the importance and popularity of dairy in the two countries and on budget restrictions. A standardized questionnaire was used to conduct face-to-face interviews with the respondents.

4. Methods

The ordered probit and logit models were used to identify socio-economic and psychometric factors influencing the frequency of overall yoghurt consumption and the factors influencing the consumption of local, domestic, and imported yoghurts. The means and standard deviations of socio-economic variables used in the logit and ordered probit model are described in Table .

Table 1. Description of socio-economic variables used in the binary logit and ordered probit models

Prior to the estimation of the models, exploratory factor analysis using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and the Varimax rotation with Kaizer normalization were used to reduce the statements regarding consumer attitudes and perceptions into unrelated factors and included in the econometric models as independent variables.

4.1. Ordered probit model: factors influencing the frequency of yoghurt consumption

The frequency of consuming yoghurts in general varies from one household to the other and depends on certain factors specific to each household. In this case, the consumption frequency is considered as discrete and ordinal, . In literature, ordinal or categorical dependent variables such as those in this study are usually modelled with an ordered logit or probit model, which are an extension of the binary models. Pioneered by McKelvey and Zavoina (Citation1975), the ordered probit model is now widely used for modelling ordinal categorical dependent variables. According to Greene and Hensher (Citation2010) the ordered probit model provides an efficient approach to recover the model parameters. It estimates the probability of an outcome as a linear function of the selected independent variables in addition to the predicted threshold values. For consumer

, we consider

as the unobserved continuous dependent variable so that;

Where is a matrix of known values of the independent explanatory variables for consumer

,

is a vector of parameters reflecting the relationship between

and the variables in

, and

is an unobserved random variable assumed to be independent and identically distributed with a standard normal distribution that is

. While the continuous variable,

, is unobserved, the indicated frequency of consumption,

, with

categories is observed. Therefore, the probability that individual

has a consumption frequency in outcome

is given as;

Where the parameters are the cut points or unknown threshold parameters defining potential ordered outcomes for

, and

is a standard normal cumulative density function. The probabilities enter the log-likelihood function and the thresholds

are estimated simultaneously by an iterative procedure of the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method, which is expressed as;

Maximizing the likelihood function provides estimates of the parameters along the threshold parameters

,

,

, … ,

.

4.2. | the logit model: determining factors influencing local, domestic, and imported yoghurt consumption

We assume that the consumer tries to maximize his/her utility subject to a constrained budget and that the ith household obtains maximum utility (U) from consuming yoghurt from a specific origin given a set of attributes of the household and a random term intended to capture the factors that affect utility but are omitted. A multinomial logit model could be an option in this instance. However, since the consumption of yoghurt from one origin does not limit the consumption from another origin, all possible combinations must be modelled. Considering the size of the data and the interpretation of the results, a binary model is suitable instead. The binary model is rooted in the threshold theory of decision-making (Hill & Kau, Citation1973). Based on utility maximization, the choice of yoghurt from an origin yields a reaction threshold of one (1) if the consumer chooses the product and zero (0) if otherwise and is expressed as;

This means if

is greater than or equal to a critical value,

and

if

is less than a critical value,

represents the combined effects of the independent variables (

) at the threshold level.

EquationEquation (4)(4)

(4) can be expressed as;

The function, F, may take the form of a normal, logistic or probability function taking on values from 0 to 1. The logit model uses a logistic cumulative distributive function to estimate P which is expressed as;

According to Greene (Citation2008) the probability model is a regression of the conditional expectation of on

giving:

The relative effect of each of the independent variables on the probability of opting for yoghurt from a specific origin is obtained by differentiating Equationequation (9)(9)

(9) with respect to

resulting in Equationequation (10)

(10)

(10) (Greene, Citation2008):

The logit was chosen over the probit model because of its mathematical convenience and simplicity (Greene, Citation2008) while the maximum likelihood method was used in the estimation of parameters. The empirical model for the logit estimation is specified as;

Where denotes choice of yoghurt from origin i (i.e., local, domestic, and imported),

is the intercept term,

is the coefficient of the explanatory variables,

is the set of explanatory variables influencing the choice of yoghurt, and

is the error term capturing omitted variables.

5. Results

5.1. Frequency of yoghurt consumption by origin

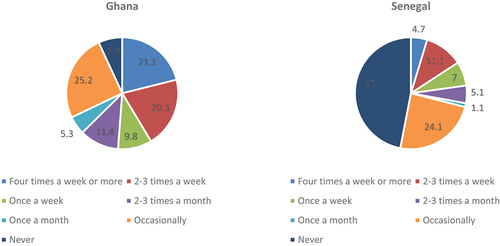

Regarding frequency, yoghurts are generally consumed more often in Ghana compared to Senegal (Figure ). Fifty-one percent (51%) of the Ghanaian respondents consume yoghurt regularly (i.e. once a week and more) and in Senegal, 23%. Interestingly, only 7% of respondents indicated that they never consume yoghurt in Ghana compared to 47% of the Senegalese respondents.

Figure 1. Yoghurt consumption frequency by households.

Consumption of the different origins of yoghurt in both countries are presented in Table . Even though most of the respondents consume yoghurts in Ghana, about 43.2% have never consumed local yoghurts which is significantly higher than the proportion (13.9%) who have never consumed local yoghurts in Senegal. Local yoghurt may therefore be more available, accessible and/or more preferred in Senegal compared to Ghana. Domestic yoghurts on the other hand are consumed more frequently in Ghana. Regarding imported yoghurts, the picture in Ghana and Senegal are similar with around 70% of respondents in both countries consuming it occasionally or never.

Table 2. Yoghurt consumption frequency based on origin

5.2. Exploratory factor analysis of consumers’ attitudes and perceptions

The exploratory factor analysis using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation on the perceptual and attitudinal statements yielded 12 items for Ghana and 13 items for Senegal. Prior to the factor analysis, a test was performed to identify inter-item correlation where items with low coefficients below the acceptable threshold of 0.30 (Hair et al., Citation2010) were not included in the analysis. A total of 5 and 7 factors each were retained for Ghana and Senegal. However, 2 and 3 factors respectively for Ghana and Senegal with Cronbach’s alpha (α) values below the acceptable threshold of 0.6 (Bland & Altman, Citation1997) were dropped. Items retained for each factor are those with Eigen values above 1 and with loadings of 0.5 and above. Tables (Ghana) and 4 (Senegal) present the Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) values, items with their respective factor loadings, percent of explained variance, mean values and Cronbach’s alpha scores. For Ghana, the factors in Table explain 50.8% of the error variance.

Table 3. Exploratory factor analysis of consumers’ attitude and perceptions: Ghana

Table 4. Exploratory factor analysis of consumers’ attitude and perceptions: Senegal

Regarding Senegal, the four factors retained in Table explain 68.6% of the error variance.

The factors generated are included in the probit models as independent psychometric variables and are used to explain the frequency of yoghurt consumption.

5.3. Socio-economic factors influencing the frequency of yoghurt consumption

Factors influencing overall yoghurt consumption in Ghana and Senegal from the univariate ordered probit model are presented in Table . The models are statistically significant (prob.> χ2 = 0.0000). However, the non-linearity of the probit model makes the interpretation of the estimated coefficients difficult (Agresti & Tarantola, Citation2018; Hoetker, Citation2007; Zelner, Citation2009). The marginal effects which are expressions of how the predicted probability outcomes (dairy consumption) change with a change in the explanatory variables are instead interpreted (Tables ).

Table 5. Results of the ordered probit models: Ghana and Senegal

Table 6. Predicted probabilities and marginal effects of factors influencing overall yoghurt consumption frequencies-Univariate ordered probit model: Ghana

Table 7. Predicted probabilities and marginal effects of factors influencing overall dairy consumption frequencies-Univariate ordered probit model: Senegal

Respondents with post-secondary education (tertiary) in Ghana have a higher probability of consuming yoghurts frequently, 2-3 times a week by 6.1% points or four times a week or more by 13.7% points (Table ). The frequency of consumption by this educational group could be linked to the level of incomes. Generally, high levels of education attract higher incomed jobs. Employed households in Ghana consume yoghurts less frequently, once a month by 1.0% or occasionally by 10.0% points. Besides, households with high income levels have a high probability of consuming yoghurts frequently, four times per week or more by 5.6% points. Income is also significant in the case of Senegal. Thus, high-income earning households in Senegal have a significantly high probability of consuming yoghurts occasionally by 1.9% points or more frequently by 2.9% points compared to households with low incomes.

Moreover, children (less than 18 years) additionally contribute to the frequency of yoghurt consumption in Senegalese households either daily (4.7%), 2–3 times per week (7.7%) or at least once a week (3.3%).

The findings are consistent with that of other studies which have investigated dairy consumption and showed that the frequency of dairy consumption is positively influenced by higher educated households (Fuller et al., Citation2007; Guiné et al., Citation2020), higher incomes (Saheeka et al., Citation2013; Tekea, Citation2021) and the presence of children in the household (Fuller et al. (Citation2007).

5.4. Factors influencing local, domestic and imported yoghurt consumption

5.4.1. Ghana

Results from the binary Logit models are presented in Table . The significant influence of post-secondary level education in the case of Ghana—is confirmed for all three origins. With regard to local and imported yoghurt, coefficients are larger and highly significant compared to domestic yoghurt. Thus, households with heads or decision makers with post-secondary level education (tertiary) have a significantly high likelihood of consuming yoghurts from the three origins, particularly local and imported yoghurts. Further, high-income households are more likely to consume local, domestic and imported yoghurts compared to low income households, with the largest effect on the consumption frequency of imported yoghurt.

Table 8. Results of the logit model

Age has a significant and positive influence on the consumption of local yoghurt. Older people are more traditional and accustomed to local foods compared to the modern younger generations. Boniface and Umberger (Citation2012) find similar results in Malaysia where age has a positive influence on the consumption of local dairy products. The presence of children less than 18 years in the household negatively influences the consumption of local yoghurt. This could be due to parents trying to be more cautious considering the safety risks associated with local dairy products, similar to the finding of Yin et al. (Citation2018) in China where parents are safety conscious regarding the milk products they purchase for their children. However, larger households in Ghana are observed to have a high likelihood of consuming local yoghurt compared to smaller households. People who are gainfully employed have a lower likelihood of consuming domestic yoghurts compared to the unemployed, contrary to our expectations. Furthermore, consumers who perceive local dairy products as unhygienically produced and unsafe have a lower tendency of consuming local yoghurts. These consumers are cautious about the risks of exposure to food-borne diseases which is reflected in their consumption behaviour. Therefore, consumers who perceive local dairy products as unhygienic and unsafe have a higher probability of consuming domestically produced yoghurts more frequently.

In contrast, the results show that consumers advocating and expressing a willingness-to-pay for local (dairy) products have a significantly higher likelihood of consuming imported yoghurt revealing a gap between stated attitudes and behaviour. In general, ethnocentric attitudes are said to lead to the objection of imported products (Sharma et al., Citation1995; Shimp & Sharma, Citation1987). However, the cognitive effect of COO on ethnocentrism as seen here is not reflected in consumers’ decisions. The attitude-behaviour gap in this case shows that ethnocentric consumers do not necessarily exhibit a higher likelihood of choosing local over imported yoghurts and confirms the assertion of Sharma et al. (Citation1995) while contrasting the findings of studies such as Blazquez-Resino et al. (Citation2021) and Schnettler et al. (Citation2017). Respondents who perceive local dairy products as less diverse and with low value addition have a lower likelihood of consuming local yoghurts. Generally, local dairy products sold in Ghana are largely not certified, are poorly packed with no traceable information and are limited in product range (Boimah et al., Citation2021). To be on the safe side, cautious consumers may prefer not to patronize products whose production histories are missing. This could explain why consumers with this mindset do not patronize local yoghurts.

5.4.2. Senegal

In Senegal, the regression results show that married households have a lesser likelihood of consuming domestic yoghurts compared to unmarried homes. However, this effect is only significant at the 10% level. Unlike the case of Ghana, higher levels of education and age do not have a significant influence. Households with high income levels are more likely to consume all three origins of yoghurt compared to low-income ones with the largest effect for domestic yoghurt. The presence of children less than 18 years in the household significantly increase the likelihood of consuming yoghurts from all three origins in Senegal. Dairy products are vital to the growth of children, considering their rich source of calcium. It is therefore highly recommended worldwide for infants, toddlers, and young children. Respondents who are skeptical about the hygienic and safety standards of local milk handling, processing and marketing, have a significantly higher likelihood of consuming yoghurts from all three origins. This result is in contrast to the behaviour of concerned Ghanaians who exhibit a lower likelihood of consuming local yoghurt. Comparing item means of Ghana and Senegal (Tables ), it is obvious that on average Senegalese respondents are less bothered. This means concerns regarding hygienic production, sales locations and safety risks associated with dairy products do not influence consumption behaviour. Boimah and Weible (Citation2021) find similar results from their focus group discussion study in Senegal where consumers exhibit a very strong preference for local products over domestic and imported ones although hygienic and safety concerns were mentioned. We can say that Senegalese perceive production and sales locations as unhygienic but might be unaware of the associated health risks, or better still other reasons (e.g., culture, tradition) outweigh food safety as milk is a part of their local diets. According to Sharma et al. (Citation1995) people prefer and choose local goods because they want to support domestic industries. However, in Senegal, ethnocentric tendencies were found to have a high influence on the purchase of yoghurt from all three origins, which contrasts literature. Nevertheless, the coefficient for local yoghurt is the largest and is highly significant which means that ethnocentric consumers have a higher likelihood of purchasing local yoghurt compared to the purchase of domestic and imported yoghurts. Thus, we can say that an attitude-behaviour gap is not so apparent in the case of Senegal as we see in Ghana. Moreover, the results show that other factors beyond ethnocentrism drive consumers in their purchase behaviour.

Consumers with concerns about minimal value addition to local milk are less likely to consume local yoghurts but have a high likelihood of consuming domestic and imported yoghurts. This finding is similar to that of Ghana where those respondents who care most about product diversity and value addition have a lower probability of consuming local yoghurts. Similar to Ghana, local yoghurts in Senegal are not well packaged and do not have traceable information. We can therefore deduce a strong influence of value addition and product diversity on consumer purchases because coefficients for all three origins are highly significant, negative for local yoghurt and positive for domestic and imported yoghurts. Tekea (Citation2021) and N. Bytyqi et al. (Citation2020) in their separate studies in Ethiopia and Kosovo find that traceable information is an important attribute considered by consumers in their choice of dairy products. The variable “comparatively expensive and scarce local dairy products” stand for consumers who perceive imported dairy products as cheaper and local dairy products as scarce and expensive in Senegal. This variable has a significantly positive influence on the likelihood of consuming all three origins of yoghurt. Boimah and Weible (Citation2021) conducted a focus group discussion study in Senegal and found that the participants perceive local milk and its products as more expensive and scarcer. When they are available, consumers buy them irrespective of their comparatively high prices. However, the high accessibility, especially of domestic yoghurts influence their purchase. Ilie et al. (Citation2021) similarly find price and store availability as key factors influencing the purchase of dairy products in Romania. In a country where milk and its products are a significant component of diets, accessibility is very relevant in ensuring food security, and in this aspect, imported milk powder seems to be playing a pivotal role.

6. Discussion

In this study, the effect of “product origin” is demonstrated through consumers’ perceptions and preferences. Ethnocentric attitudes in particular were exhibited in both countries towards local milk which is perceived as fresher, tastier, and healthier. This further impacts on the preference for local milk. In the case of yoghurt, local origin is associated with high quality in terms of taste and freshness and low quality when it comes to food safety, product diversity, packaging, certification and labelling. Despite the positive attributes accorded to local yoghurt, the results show that there is a higher likelihood for consumers to choose domestic and imported yoghurts, and this reveals an “attitude-behaviour gap” in the purchase of dairy products in both countries.

Overall, this study has demonstrated that positive quality perceptions and ethnocentric attitudes do not necessarily influence consumers in their final decision making. Consumers may demonstrate their preference for a specific product but final purchase decisions to a large extent could depend on other factors, and include time restrictions, insufficient information, conflict of interests, price and availability (e.g., Padel and Forster, Citation2005; Vermeir and Verbeke, Citation2006). Also, Solomon et al. (Citation2010) note that consumers sometimes express ethnocentric attitudes and values in their role as citizens but their actions are contrary in their purchase decisions. In this study “availability” and “accessibility” emerged as the main factors. As mentioned by the consumers, imported and domestic dairy products are more available and are more affordable. “Product availability” is therefore assumed to play a central role in the choice and frequency of dairy consumption in both countries, and in this case domestic and imported dairy products are favoured at the point of sale. This is consistent with findings of Boimah and Weible (Citation2021) in Senegal and Karoui and Khemakhem (Citation2019) in Tunisia where consumer ethnocentrism strongly influence the choice of imported goods instead of local ones. Verlegh and Steenkamp (Citation1999) also find origin to have a larger effect on perceived quality of a product than on the purchase intention. We believe low self-sufficiency-rates in both countries for milk and milk products (Zamani et al., Citation2021) underline these results.

Furthermore, consumers in the two countries expressed concerns about the hygienic and safety conditions under which local dairy products are produced and marketed. While this concern decreases the likelihood of purchasing local dairy products in Ghana, the opposite is observed in Senegal. The differing attitudes show that food safety indicators can play minimal roles in food choice in some developing countries. However, safeguarding consumers in both countries against foodborne illnesses is important and mean a significant improvement in local milk handling, processing and marketing which should be enforced by the responsible authorities. Awareness campaigns should be organized for example by the government and the consumer protection association to educate consumers on the indicators of contaminated food and the health risks associated with consuming them.

Also, the likelihood of opting for local products decreases where consumers express concern about the low value-addition to fresh milk and the low diversity of local products. This points to the relevance of product diversity, packaging, certification and labelling in marketing which consumers associate more with domestic and especially imported products. The result further reinforces the significance of value addition to consumer purchases and a relevant entry point for the local dairy sector’s development. Actors in the local dairy value chains should consider these concerns as an opportunity to increase revenues and hence profits noting the positive perceptions of consumers towards local milk and the willingness-to-pay a higher price for local products.

From a theoretical perspective, demand triggers production, and practically stimulates investments that lead to upgrading value chains. The findings from this study highlight one of the reasons behind the retarded growth of the local dairy value chains in West Africa—“low value addition” and “low product diversity”. As the world advances at a fast pace, so are consumer demands, tastes, and preferences for food products. Meeting these needs contributes to the success and development of businesses, and we see it favouring the imported and domestic dairy industries in these developing nations.

Although the findings are insightful, the results should be carefully interpreted. First, the sample was drawn from urbanized areas, meaning that the results could vary if the study were conducted in rural regions where milk consumption is lower. Second, the analysis was based on consumers’ stated preferences instead of data collected on their revealed preferences. Considering the rejection of local dairy products based on poor hygiene and safety reasons, and on low value addition, we encourage further research that examines consumers’ acceptance of improved local dairy products, especially in the case of Ghana.

7. Conclusions

This paper investigates consumer perceptions and preferences for local, domestic and imported yoghurts in Ghana and Senegal with an aim of providing a better understanding on the influence of origin on consumer behaviour in the context of developing countries. The study is timely for two reasons—first, by considering the growing importance of origin as a quality cue in consumer food choices, and second, based on the criticisms of European dairy exports to developing nations.

Our study shows that dairy products in general are consumed on a regular basis particularly in developing countries. However, differences were found in the frequency of consumption and factors influencing consumption in the study countries. In Ghana, factors such as higher education and incomes significantly impact on how often dairy products are consumed while in Senegal these factors were not of importance because milk and its products are traditional components of the diet of Senegalese. Our study therefore provides an insight into the role of culture and tradition in the consumption of food products.

The overarching issue in both countries is that local products are scarce to find. Imported dairy products, especially milk powder as derived from a broader lens contributes to ensuring food security in developing countries by ensuring product (i) availability, (ii) diversity, (iii) affordability, and (iv) safety. On this account, increasing imports particularly of milk powder to developing countries should not be blamed entirely on EU exporters but should be considered as a “necessary evil” in meeting consumer needs and demands.

Acknowledgments

This paper is an outcome of the project “Impact of meat and milk product exports on developing countries” (IMMPEX). The research was supported by funds provided by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) based on a decision of the Parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany via the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (BLE) [Grant number: 28N1800017].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mavis Boimah

Mavis Boimah is a Researcher in the Institute of Market Analysis at the Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute, Germany. Dr. Boimah holds a Ph.D. in Applied Agricultural Economics and Policy from the University of Ghana (2017), an MPhil in Agricultural Economics (2009) and a BSc. in Agriculture (2005). Her research interests include issues in agricultural sustainability, climate change, green economy, gender, agri-food trade, and consumer behaviour.

Daniela Weible

Daniela Weible is a Researcher in the Institute of Market Analysis at the Johann Heinrich von Thünen Institute, Germany. Dr. Weible holds a Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics from the University of Göttingen (2014), a MSc. in Food Economics from the University of Giessen (2009) and a BSc. in Ecotrophology also from University of Giessen (2007). Her research interests include global food security issues, sustainable diets, food environments, consumer and behaviour.

References

- Abdalrahman, M., Fehér, I., & Lehot, J. (2018). The influence of consumer ethnocentrism on consumer purchase intention of domestic food products. Journal of Economy & Society, (3–4), 126–21. https://doi.org/10.21637/gt.2018.3-4.08

- Abraham, A., & Patro, S. (2014). ‘Country-of-Origin’ effect and consumer decision-making. Management and Labour Studies, 39(3), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042x15572408

- Agresti, A., & Tarantola, C. (2018). Simple ways to interpret effects in modeling ordinal categorical data. Statistica Neerlandica, 72(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/stan.12130

- Bagga, T., & Bhatt, M. (2013). A study of intrinsic and extrinsic factors influencing consumer buying behaviour online. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 9(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319510x13483515

- Balcombe, K., Bradley, D., Fraser, I., & Hussein, M. (2016). Consumer preferences regarding country of origin for multiple meat products. Food Policy, 64, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.008

- Barbarossa, C., De Pelsmacker, P., Moons, I., & Marcati, A. (2016). The influence of country-of-origin stereotypes on consumer responses to food safety scandals: The case of the horsemeat adulteration. Food Quality and Preference, 53, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.05.015

- Berbel-Pineda, J. M., Palacios-Florencio, B., Santos-Roldán, L., & Ramírez Hurtado, J. M. (2018). Relation of country-of-origin effect, culture, and type of product with the consumer’s shopping intention: An analysis for small- and medium-sized enterprises. Complexity, 2018, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8571530

- Bilkey, W. J., & Nes, E. (1982). Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations. Journal of International Business Studies, 13(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490539

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1997). Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ, 314(572). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572

- Blazquez-Resino, J. J., Gutierrez-Broncano, S., Jimenez-Estevez, P., & Perez-Jimenez, I. R. (2021). The effect of ethnocentrism on product evaluation and purchase intention: The case of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO). Sustainability, 13(9), 4744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094744

- Block, C. E., & Roering, K. J. (1976). Essentials of consumer behavior. Dryden Press.

- Boimah, M., & Weible, D. (2021). “We prefer local but consume imported”: Results from a qualitative study of dairy consumers in Senegal. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2021.1986453

- Boimah, M., Weible, D., & Weber, S. (2021). Milking challenges while drinking foreign milk : The case of Ghana’s dairy sector. In B (Ed.), System dynamics and innovation in Food Networks (pp. 14–25). https://doi.org/10.18461/pfsd.2021.2003.

- Boniface, B., & Umberger, W. J. (2012). Factors influencing Malaysian consumers ’ consumption of dairy products. Australia Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, 1, 1–30.

- Broutin, C., Levard, L., & Goudiaby, M. (2018). Quelles politiques commerciales pour la promotion de la filière “lait local” en Afrique de l ’ Ouest? Rapport de synthèse. Gret. ( 100 Pages).

- Bruwer, J., Cohen, J., Driesener, C., Corsi, A., Lee, R., Huang, A., & Lockshin, L. (2023). Chinese wine consumers ’ product evaluation: effects of product involvement, ethnocentrism, product experience and antecedents. Australasian Marketing Journal, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/14413582231166066

- Bytyqi, H., Mensur, V., Muje, G., Hajrip, M., Halim, G., Iliriana, M., & Njazi, B. (2008, January). Analysis of consumer behaviour in regard to dairy products in Kosovo. Journal of Agricultural Research, 46(3), 311–320.

- Bytyqi, N., Muji, S., & Rexhepi, A. (2020). Consumer behavior for milk and dairy products as daily consumption products in every household—The case of Kosovo. Open Journal of Business and Management, 08(2), 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2020.82063

- Chung Lo, S., Tung, J., Yuan Wang, K., & Huang, K. (2017). Country-of-origin and consumer ethnocentrism: Effect on brand image and product evaluation. Journal of Applied Sciences, 17(7), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2017.357.364

- Clipa, C. I., Danileț, M., & Clipa, A. M. (2017). Country of origin effect and perception of Romanian consumers. Junior Scientific Research Journal, III(1), 19–29.

- Colonna, A., Durham, C., & Meunier-Goddik, L. (2011). Factors affecting consumers’ preferences for and purchasing decisions regarding pasteurized and raw milk specialty cheeses. Journal of Dairy Science, 94(10), 5217–5226. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2011-4456

- Corniaux, C. (2017). Situation et potentiel du secteur laitier au Burkina Faso. CIRAD-Département ES.

- Corniaux, C. (2018). Etat des filières laitières dans les 15 pays de la CEDEAO, de la Mauritanie et du Tchad Annexe 11 : Fiche Sénégal.

- Corniaux, C., & Duteurtre, G. B. C. (2014). Filières laitières et développement de l’élevage en Afrique de l’Ouest - L’essor des minilaiteries. Karthala. (p. 252). p. 252.

- Duteurtre, G., & Corniaux, C. (2013). Etude relative à la formulation de programme d’action détaillé de développement de la filière lait en zone UEMOA. CIRAD/UEMOA.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 10(2), 130–132. https://doi.org/10.2307/2065853

- Forbes-Brown, S., Micheels, E., & Hobbs, J. E. (2015). Signalling origin: Consumer willingness to pay for dairy products with the “100 % Canadian milk” label. 29th International Conference of Agricultural Economists. Milan, Italy, 8–14.

- Fuller, F., Beghin, J., & Rozelle, S. (2007). Consumption of dairy products in urban China: Results from Beijing, Shangai and Guangzhou. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 51(4), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8489.2007.00379.x

- Gedikoglu, H., & Parcell, J. L. (2014). Variation of consumer preferences between domestic and imported food: The case of artisan cheese. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 45(2), 174–194.

- Greene, W. H. (2008). Econometric analysis. In R. Banister (Ed.), Upper saddle (5th ed) (pp. 1–802). Prentice Hall.

- Greene, W. H., & Hensher, D. A. (2010). Modeling ordered choices: A primer. Modeling Ordered Choices: A Primer, 1–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511845062

- Guiné, R. P. F., Florença, S. G., Carpes, S., & Anjos, O. (2020). Study of the influence of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors on consumption of dairy products: Preliminary study in Portugal and Brazil. Foods, 9(12), 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121775

- Guri, B. Z., Ameleke, G., & Karbo, N. (2018). Etat des filières laitières dans les 15 pays de la CEDEAO, de la Mauritanie et du Tchad Annexe 5 : Fiche Ghana. CIRAD, Campus de Baillarguet, 34(398), 1–21.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. In Upper saddle (7th ed) (pp. 217–221). Prentice-Hall.

- Han, C. M. (1989). Country image: Halo or summary construct? Journal of Marketing Research, 26(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172608

- Hill, L., & Kau, P. (1973). Application of multivariate probit to a threshold model of grain dryer purchasing decisions. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 55(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/1238657

- Hoetker, G. (2007). The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research: Critical issues. Strategic Management Journal, 28(4), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

- Holdershaw, J., Gendall, P., & Case, P. (2013). Country of origin labelling of fresh produce: Consumer preferences and policy implications. Market & Social Research, 21(2), 22.

- Ilie, D. M., Lădaru, G. R., Diaconeasa, M. C., & Stoian, M. (2021). Consumer choice for milk and dairy in Romania: Does income really have an influence? Sustainability, 13(21), 12204. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112204

- Johansen, S. B., Næs, T., & Hersleth, M. (2011). Motivation for choice and healthiness perception of calorie-reduced dairy products. A cross-cultural study. Appetite, 56(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.11.137

- Karoui, S., & Khemakhem, R. (2019). Consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 25(2), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2019.04.002

- Kaya, I. H. (2016). Motivation factors of consumers’ food choice. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 07(3), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2016.73016

- Kilders, V., Caputo, V., & Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. (2021). Consumer ethnocentric behavior and food choices in developing countries: The case of Nigeria. Food Policy, 99, 101973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101973

- Krešić, G., Herceg, Z., Lelas, V., & Jambrak, A. R. (2010). Consumers’ behaviour and motives for selection of dairy beverages in Kvarner region: A pilot study. Mljekarstvo, 60(1), 50–58.

- Magnani, S. D., Ancey, V., & Hubert, B. (2019). Dairy policy in Senegal: The need to overcome a technical mindset. European Journal of Development Research, 31(5), 1227–1245. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-00208-4

- Makanyeza, C., & Du Toit, F. (2017). Consumer ethnocentrism in developing countries: Application of a model in Zimbabwe. Acta Commercii, 17(1), 2413–1903. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v17i1.481

- McKelvey, R. D., & Zavoina, W. (1975). A statistical model for the analysis of ordinal level dependent variables. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 4(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.1975.9989847

- Miguel, L., Marques, S., & Duarte, A. P. (2022). The influence of consumer ethnocentrism on purchase of domestic fruits and vegetables: Application of the extended theory of planned behaviour. British Food Journal, 124(13), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-11-2021-1208

- Molina-Flores, B., Manzano-Baena, P., & Coulibaly, M. D. (2020). The role of livestock in food security, poverty reduction and wealth creation in West Africa. FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8385en

- Nadiri, H., & Tümer, M. (2010). Influence of ethnocentrism on consumers’ intention to buy domestically produced goods: An empirical study in North Cyprus. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 11(3), 444–461. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2010.22

- Nguyen, A., & Alcantara, L. L. (2022). The interplay between country-of-origin image and perceived brand localness: An examination of local consumers’ response to brand acquisitions by emerging market firms. Journal of Marketing Communications, 28(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2020.1840422

- Norris, A., & Cranfield, J. (2019). Consumer preferences for country-of-origin labeling in protected markets: Evidence from the Canadian dairy market. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 41(3), 391–403. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppz017

- Obermiller, C., & Spangenberg, E. (1989). Exploring the effects of country of origin labels: An Information Processing Framework. In I. I. A. I. C. U. K. Srull (Ed.), NA - Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 16, pp. 454–459). Association for Consumer Research.

- Oppong-Apane, K. (2016). Review of the livestock/meat and milk value chains and policy influencing them in Ghana. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

- Orasmaa, T., Duteurtre, G., & Corniaux, C. (2016). The end of EU milk quotas - implications in West Africa: Literature review and future perspectives. CIRAD. Retrieved from https://agritrop.cirad.fr/584599/1/The_end_of_EU_milk_quotas_2016.pdf

- Padel, S., & Foster, C. (2005): Exploring the Gap Chicken Meat Quality in Brasilia, Brazil as a Function Between Attitudes and Behaviour: Understanding Why of Family Income. Proceeding of VIIth International Consumers Buy or Do Not Buy Organic Food British PENSA ConferenceSao Paolo, 107(8), 606–626.

- Profeta, A. (2008). A theoretical framework for Country-of-Origin- Research in the food sector. Discussion Paper 01-2008, Environmental Economics and Agricultural Policy Group, Technische Universität München.

- Profeta, A., Balling, R., & Roosen, J. (2012). The relevance of origin information at the point of sale. Food Quality and Preference, 26(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.03.001

- Rani, P. (2014). Factors influencing consumer behaviour. International Journal of Current Research and Academic Review, 2(9), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.17221/283-agricecon

- Rezvani, S., Shenyari, G., Dehkordi, G. J., Salehi, M., Nahid, N., & Soleimani, S. (2012). Country of origin: A study over perspective of intrinsic and extrinsic cues on consumers` purchase decision. Business Management Dynamics, 1(11), 68–75.

- Saheeka, R. F., Udugama, J. M. M., Jayasinghe-Mudalige, U. K., & Attanayake, A. M. C. M. (2013). Determinants of dairy product consumption patterns: The role of consumer perception on food quality attributes. 12th Agricultural Research Symposium, 419–423. Retrieved from https://mail-attachment.googleusercontent.com/attachment/u/0/?ui=2&ik=97da07a254&view=att&th=15bc97cd766a2d4b&attid=0.1&disp=inline&realattid=1566293671857356800-local0&safe=1&zw&sadnir=1&saddbat=ANGjdJ8ZeCl2tYRxuMfq6d5sTbEGtoSEkYYFpIwX8fxpZTw34YTUZcm1Yt9

- Sama, R. (2019). Impact of media advertisements on consumer behaviour. Journal of Creative Communications, 14(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258618822624

- Schnettler, B., Miranda, H., Lobos, G., Sepúlveda, J., & Denegri, M. (2011). A study of the relationship between degree of ethnocentrism and typologies of food purchase in supermarkets in central-southern Chile. Appetite, 56(3), 704–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.007

- Schnettler, B., Ruiz, D., Sepúlveda, O., & Sepúlveda, N. (2008). Importance of the country of origin in food consumption in a developing country. Food Quality and Preference, 19, 372–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2007.11.005

- Schnettler, B., Sánchez, M., Miranda, H., Orellana, L., Sepúlveda, J., Mora, M., Lobos, G., & Hueche, C. (2017). “Country of origin” effect and ethnocentrism in food purchase in Southern Chile. Revista de La Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, 49(2), 243–267. Retrieved from. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=382853527018

- Schooler, R. D. (1965). Product bias in the central American common market. Journal of Marketing Research, 2(4), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224376500200407

- Sckokai, P., Veneziani, M., Moro, D., & Castellari, E. (2014). Consumer willingness to pay for food safety: The case of mycotoxins in milk. Bio-Based and Applied Economics, 3(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.13128/BAE-12827

- Sharma, S., Shimp, T. A., & Shin, J. (1995). Consumer ethnocentrism: A test of antecedents and moderators. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894609

- Shepherd, R. (2001). Does taste determine consumption? Understanding the psychology of food choice. In (<. <. Frewer, <. <. Risvik, & <. <. Schifferstein.), (Eds.), 2001: Food, people and society: A European perspective of consumers’ food choice (pp. 117–130). Springer-Verlag Berlin Hedelberg. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851990323.0000

- Shimp, T., & Sharma, S. (1987). Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(3), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378702400304

- Solomon, M. R., Bamossy, G., Askegaard, S., & Hogg, M. K. (2010). Consumer behaviour: A European perspective (4th ed.). Prentice Hall/Financial Times.

- Tekea M. E. (2021). Review on consumer preference of milk and milk product in Ethiopia. International Journal of Horticulture, Agriculture and Food Science, 5(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijhaf.5.2.1

- Verlegh, P. W. J., & Steenkamp, J. E. M. (1999). A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. Journal of Economic Psychology, 20(5), 521–546. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429461439-7

- Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer “Attitude-Behavioral Intention” Gap. Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, 19, 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-005-5485-3

- Wang, Y., & Heitmeyer, J. (2006). Consumer attitude toward US versus domestic apparel in Taiwan. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00450.x

- Xu, L., Yang, X., & Wu, L. (2020). Consumers’ willingness to pay for imported milk: Based on Shanghai, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010244

- Yang, R., Ramsaran, R., & Wibowo, S. (2018). An investigation into the perceptions of Chinese consumers towards the country-of-origin of dairy products. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12403

- Yang, R., Ramsaran, R., & Wibowo, S. (2022). Do consumer ethnocentrism and animosity affect the importance of country-of-origin in dairy products evaluation? The moderating effect of purchase frequency. British Food Journal, 124(1), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2020-1126

- Yin, S., Lv, S., Chen, Y., Wu, L., Chen, M., & Yan, J. (2018). Consumer preference for infant milk-based formula with select food safety information attributes: Evidence from a choice experiment in China. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 66(4), 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12183

- Zamani, O., Pelikan, J., & Schott, J. (2021). EU-Exports of livestock products to West Africa: An analysis of dairy and poultry trade data. Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut, 42p, Thünen Working Paper 162.

- Zelner, B. A. (2009). Research notes and commentaries: Using simulation to interpret results from logit, probit, and other nonlinear models. Strategic Management Journal, 30(12), 1335–1348. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj