?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Malnutrition is one of the biggest threats to the global community. At household level, women and children are among the most vulnerable groups. It is expected that farming households will have better food security, owing to food production and income generation from selling agricultural produce. This paper sought to assess the dietary diversity and the associated factors thereof on women and children in farming households in Lesotho. Multivariate regression analysis was used to identify the determinants of the dietary diversity scores. The results showed that only 20.6% of the women of reproductive age consumed a minimum of five food groups or more, with a mean dietary diversity score of 5.63. The majority (78%) of under-five children had low dietary diversity (mean = 2.12), as they consumed less that 4 food groups. The regression analysis indicated that women’s age group, household size, household monthly income and being a beneficiary of an agricultural program were associated with women’s dietary diversity. On the other hand, the determinants identified for children’s dietary diversity were education status, gender and marital status of the caretaker. Interventions that aim to improve women and children’s diet quality are still much needed as levels of dietary diversity are not satisfactory. The determinants must also be further explored and considered in development planning. A nutrition-sensitive approach to agricultural programs is important as it capacitates farming households on both agricultural production and nutrition that are needed. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture maximises the contribution of agriculture to yield nutrition outcomes.

1. Introduction

Malnutrition is a global concern that comes in multiple forms: micronutrient deficiencies, undernutrition, overweight and obesity (Dhuki, Citation2020; Herrera Cuenca et al., Citation2020). Malnutrition refers to deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in an individual’s intake of energy and/or nutrients WHO, 2021). In developing countries, women and children are among the most vulnerable groups within the household (Development Initiatives, Citation2021; Setyawan & Lestari, Citation2021). Anaemia and undernutrition are the most common micronutrient forms in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with an increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity (Christian & Dake, Citation2022). Lesotho has had a clear case of a triple burden of malnutrition, with stunting, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight across all age groups (WFP, Citation2023; WFP, & UNICEF, Citation2019). While there has been progress towards reducing anaemia in women and stunting in under-five children, overnutrition and obesity have risen among children and adults. The prevalence of anaemia among women of reproductive age slightly decreased from 28.3% in 2012 to 27.9% in 2019. Stunting among under-five children also decreased from 37.7% in 2012 to 32.1% in 2020. The frequency of overweight under-five children rose from 7.0% in 2012 to 7.2% in 2020. The prevalence of obesity among the adult population increased from 14.9% in 2012 to 16.6% in 2016 (IFAD et al., Citation2022). Obesity levels among women in Lesotho are above the regional average of 20.7%, and below the regional average of 9.2% in men (Development Initiatives, Citation2021; WFP, Citation2021).

The nutrition and health of women of reproductive age is critical to both their wellbeing and that of the child. The increased need of micronutrient requirements for menstruation, pregnancy and lactation make women of reproductive age vulnerable to micronutrient deficiencies (Custodio et al., Citation2020; Gibson, Citation2016; James et al., Citation2022). It has been established that the maternal nutrition status determines the child’s health and development. Malnutrition in mothers, especially those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, can set up a cycle of deprivation that increases the likelihood of low birth weight, child mortality, serious disease, poor classroom performance and low work productivity (James et al., Citation2022; Myatt et al., Citation2018; Oot et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, adults who were stunted as children are less likely to achieve their expected physical and cognitive development, impacting their productivity (Galasso & Wagstaff, Citation2019; WFP, & UNICEF, Citation2019). Thus, malnutrition induces high social and economic costs (Dhuki, Citation2020; Herrera Cuenca et al., Citation2020).

The governments and impacted families also endure an increasing burden of health costs, which may negatively affect livelihoods (Dhuki, Citation2020; Myatt et al., Citation2018). These costly consequences can often be prevented with appropriate nutrition-sensitive actions. Among others, women’s empowerment on nutrition has been considered as a key pathway to nutrition-sensitive agricultural interventions (Melesse, Citation2021; Sharma et al., Citation2021). This could be attributed to women’s primary role as caregivers, and their responsibilities also include procuring and preparing food for the household (Gibson, Citation2016).

Dietary diversity score is one of the key indicators for individual diet quality, as it reflects nutrient adequacy (FAO, Citation2018; Keno et al., Citation2021). It is a useful measure for household food security and nutrition, as it assesses food access and the socio-economic level of the household (FAO, Citation2018; Nair et al., Citation2016). Diverse diets are critical for meeting dietary requirements and ensuring good health and nutrition. Low diversity in diets result in vulnerability to malnutrition, and makes dietary diversity a good indicator for dietary quality (Aboagye et al., Citation2021; Otekunrin & Otekunrin, Citation2021a). Dietary diversity is also significant to the achievement of the sustainable development goals 1, 2 and 3 that seek to achieve no poverty, zero hunger, good health and wellbeing (Li et al., Citation2020; UNDP, Citation2023).

Lesotho is among the countries that are challenged by poor household dietary diversity (Rantšo et al., Citation2019; Walsh et al., Citation2020; WFP, & UNICEF, Citation2019), which is likely to reflect in the women and children’s dietary diversity. Among others, household dietary diversity is low owing to limited access and availability of fresh fruits and vegetables, and limited consumption of animal products for protein (Ranneileng et al., Citation2023; WFP, & UNICEF, Citation2019). Livestock are rarely used for consumption, as they are mainly kept for commercial activities (WFP, & UNICEF, Citation2019).

Diets are evolving from traditional to refined food with low nutritional quality. This is as a result of the global food system and its effect on homogenising diets across borders and urbanisation among others (Cuevas Garciá-Dorado et al., Citation2019; Fox et al., Citation2019). These changes in diets have contributed largely to the high prevalence of malnutrition. A change in diet is evident, even among women in Lesotho, as sugary, high-fat and processed foods are being increasingly consumed (Rothman et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have contributed significantly to increased food costs and vulnerability to food insecurity and malnutrition. Consequently, the access to healthy diets is challenged, particularly in developing countries (IFAD et al., Citation2022; Otekunrin & Otekunrin, Citation2021a). Economically vulnerable households in Lesotho have felt the effect of the crisis (WFP, Citation2020).

The linkages between agriculture and nutrition have increasingly received attention from researchers (Carletto et al., Citation2017; Ogutu et al., Citation2020). One of the prevailing expectations is for farming households to have better dietary diversity owing to their self-production and income generated from agricultural produce (Ogutu et al., Citation2020; Sonandi, Citation2018; Zezza et al., Citation2017). However, in the recent past, farming in Lesotho has been challenged by erratic climatic events, and its ability to render household food security and nutrition is challenged (FAO, Citation2019; FSIN, Citation2022; Kheleli et al., Citation2021; Muroyiwa & Linakane, Citation2021). Nonetheless, recent studies that explore food security and nutrition within farming households in Lesotho, are limited.

Moreover, the studies that report women and children’s nutrition status in Lesotho mostly used anthropometric tools, which focus on the physical aspects and there is limited empirical evidence on diet quality (Makonnen et al., Citation2003; Ranneileng, Citation2013; Rothman et al., Citation2019). Nutrition status is highly dependent on feeding practices and makes assessment of diet quality an important aspect of nutrition. This study contributes to existing literature by assessing dietary diversity of women of reproductive age and under-five children from farming households. The findings are valuable in understanding nutrition-specific vulnerabilities within farming households in Lesotho. These will be beneficial for providing evidence that will inform interventions and support programs that seek to improve food and nutrition security for farming households.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area

Lesotho is a small low-middle-income country landlocked by South Africa. It has a population of about 2.2 million. The country is faced with high poverty rates that is widespread throughout the country, especially in rural areas (FAO, Citation2019; WFP, Citation2023). More than half (57%) of the population lives below the national poverty line, and 34% fall below the extreme poverty line with the poverty rate at about 49.7%. Agriculture is a major source of livelihood for 70% of the population residing in rural areas and contributes to 7% of the country’s GDP (FAO, Citation2019; World Bank, Citation2020). The country is vulnerable to extreme weather events, particularly floods and drought, which affect the productivity of agriculture. Food insecurity, low agricultural productivity, modifiable disease outbreaks and poverty are among the country’s development challenges. The country is also experiencing a triple burden of malnutrition—high stunting, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight and obesity across all age groups (WFP, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2020).

2.2. Sampling

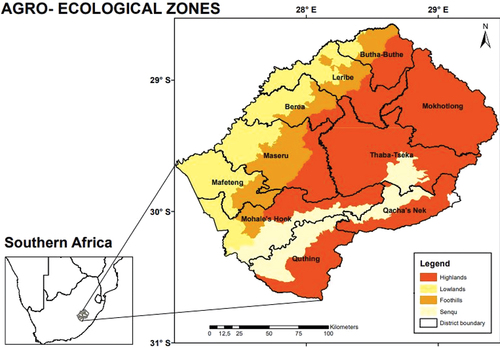

The study was conducted among small-holder farming households in Lesotho. A sample of 236 farming households was drawn, using a multi-stage sampling method. In the first stage, four of the ten districts of Lesotho were selected. Figure shows the four agro-ecological zones in Lesotho. Mafeteng, Berea, Thaba Tseka and Quthing Districts are representative of the four agro-ecological zones in the country: Lowlands, Foothills, Mountains and Senqu River Valley respectively (Bureau of Statistics BOS, Citation2016). The second stage involved a selection of 15 district constituencies, which were determined through the guidance of extension officers focusing on those that were concentrated with active farmers. In the last stage, 20 villages were selected from constituencies and 236 farming households were randomly selected to participate in the study. The farming households had to be involved in farming for at least five years. Both male and female adults (18 years and above) participated in the study. In the 236 farming households, there were 199 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) and 75 under-five children (6 to 59 months).

2.3. Measuring the dietary diversity score for women of reproductive age and under-five children

2.3.1. Minimum Dietary Diversity score for Women (MDD-W)

Dietary diversity among women of reproductive age was determined with the use of a Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDDW). It is a ten-food group indicator that measures variation in diets among women of reproductive age. The score was computed from a 24 hour recall by a scoring of one for each food group and summing it up to determine the number of groups consumed by the women (FAO, Citation2018, Citation2021). The frequency of women who consumed a minimum of five out of ten food groups was determined.

2.3.2. Child Dietary Diversity score (CDDS)

The under-five children dietary diversity score (CDDS) was employed using food consumption data from a 24 hour recall. It is a seven-food group indicator for measuring diet diversity among under-five children. A score of one was allocated to each food group, and all food groups were summed up to determine the dietary diversity score of each child. The frequency of children who had consumed a minimum of four out of seven food groups and more and those who has consumed less than four food groups, was established (FAO, Citation2018; Keno et al., Citation2021).

2.4. Variables of the study

The dependent variables were minimum dietary diversity for women (MDDW) and child dietary diversity score (CDDS). These depict the number of food groups consumed by under-five children and women of reproductive age. The ten food groups for MDDW are: starchy foods, beans and peas, nuts and seeds, all dairy, flesh foods, eggs, vitamin A-rich dark green leafy vegetables, other vitamin A-rich vegetables and fruits, other vegetables and other fruits. The seven food groups for the CDDS are: grains, roots and tubers, legumes and nuts, dairy foods, eggs, vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables and other fruits and vegetables (FAO, Citation2018, Citation2021; Keno et al., Citation2021).

The selected independent variables for women’s dietary diversity included: age of the woman, total members of the household, household monthly income, gender of the household head, receiving nutrition education, access to credit, access to extension services, and being a beneficiary of an agricultural development programme. On the other hand, the selected variables for children’s dietary diversity were: age and gender of the child, caretaker’s highest education status, gender, marital status and employment status of the caretaker, as well as receiving nutrition education.

2.5. Data collection and statistical analysis

Data were collected from March to June 2022, using electronic questionnaires (by Evasys) that consisted of sections related to various social and economic characteristics of the household, food consumption for women and children and agricultural activity. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of the Free State Ethics Committee (UFS-HSD2021/1888/21). Descriptive statistics were used to present dietary diversity scores. ANOVA and multivariate regression were used to analyse the relationship between the dietary diversity scores and possible factors, as is the case in similar studies (Edris et al., Citation2018; Rakotonirainy et al., Citation2018; Sisay et al., Citation2022). Binary logistic regression was used to test for the significance between the individual independent variables and the dependent variables (child dietary diversity score and women’s dietary diversity score). The variables that showed significant association were considered for multivariate logistic regression, where significance was identified using the p-value of 0.05. The following regression models were employed for the determinants of dietary diversity for women and children (Ma et al., Citation2022; Wijaya et al., Citation2020):

Where y = minimum dietary diversity for women, -

= regression coefficient,

= intercept,

= independent variables (age group, total members of the household, monthly income, gender of the household head, being a beneficiary on an agricultural project) and

= error.

Where y = child dietary diversity score, = intercept,

-

= regression coefficient,

= independent variables (education status, gender, marital status of the caretaker) and

= error.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Demographic characteristics

The study surveyed 236 farming households, with 199 women of reproductive age (15–45 years) and 75 children (six to 59 months). Table indicates that the majority (69.9%) of the households did not receive any nutrition-related training. Most (79.2%) of the households were not beneficiaries of any agricultural program. The majority (91.5%) of the households also used their own land for farming. The average household size is 4.46 people per household. On average, households spent monthly R1578.15 (USD79) from their average monthly income of R4606.44 (USD233).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics

3.2. Women’s dietary diversity score

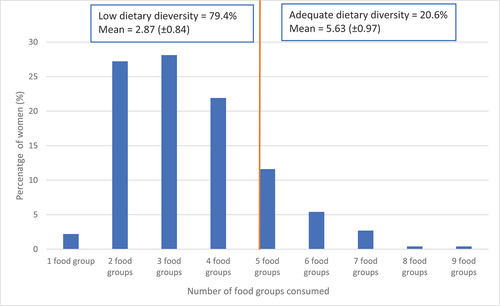

Women who had consumed a minimum of five food groups and more in the past 24 hours were considered to have adequate dietary diversity, and those who consumed less than five food groups had low dietary diversity (FAO, Citation2018, Citation2021). The findings in indicate that only 20.6% of the women of reproductive age from farming households had consumed a recommended minimum of five out of ten food groups. The mean dietary diversity was 3.45 (±1.42). Women of reproductive age in Nigeria had a slightly higher dietary diversity (4.37) (Oluwaseun A. Otekunrin & Otekunrin, Citation2021a), while women in Tanzania had a lower dietary diversity of 3 (Bellows et al., Citation2017). Even though other studies assessed dietary diversity using fewer number of food groups, low dietary diversity among women of reproductive age was evident. Women in South Senegal (Tine et al., Citation2018), Mali (Adubra et al., Citation2019), South Africa (Chakona & Shackleton, Citation2017) and Burkina Faso (Custodio et al., Citation2020) had low dietary diversity. This can be attributed to an inability to afford nutritious diets, in Lesotho in particular, the household cost to meet only energy needs in 2019 ranged from LSL 500–650 (USD25–32)/month, with most districts being around LSL 600 (USD30)/month (WFP, & UNICEF, Citation2019). This cost is likely to have increased with the rise in food prices as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict (Devereux et al., Citation2020; Otekunrin & Otekunrin, Citation2021a; Shaifuddin et al., Citation2022).

3.3. Children’s dietary diversity score

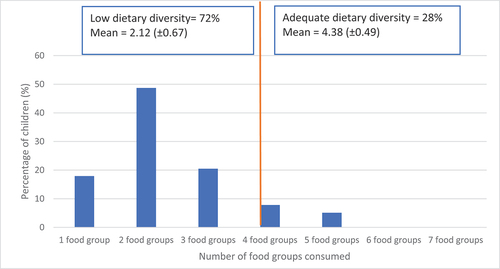

The children’s dietary diversity score (CDDS) has been categorised based on the recommended consumption of a minimum of four food groups for adequate dietary diversity, and low dietary diversity for those who consumed less than four food groups in the past 24 hours (FAO, Citation2018; Keno et al., Citation2021). As seen in Figure , the under-five children who met the minimum dietary diversity of four food groups were 28% of the surveyed children. The mean dietary diversity was 2.76 (±1.19), which was lower than children in Nigeria 3.28 (±1.28) (Otekunrin et al., Citation2022) and higher than children in Ethiopia (West Shoa Zone) with a mean of 1.82 (±0.015) (Keno et al., Citation2021). Other study findings have similar outcomes in Indonesia (Sekartaji et al., Citation2021) and Ethiopia (Bench Maji Zone) (Edris et al., Citation2018).

3.4. Determinants of women’s dietary diversity score

The findings in Table show significant association between the age of the women and their dietary diversity score. An increase of one in the age group of the women leads to an increase of 0.075 of their dietary diversity score. A study in Northern Kenya has similar findings (Gitagia et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Determinants of women’s dietary diversity score

Women from large household sizes were less likely to consume diverse diets. An increase in the total members of the household leads to a decrease in the score by 0.120. Household members from large households are more likely to be vulnerable to food insecurity, as there is an added burden on food consumption than in small sized households. This is especially true for households with low access to and availability of food (Abdullah et al., Citation2019; Drammeh et al., Citation2019). However, in Nigeria (Otekunrin & Otekunrin, Citation2021a), it was found that household size was not significantly associated with women’s diet diversity for women of ages 20–49. While the implication for large households is a need for procuring more nutritious diets, it is evident the relationship must be inferred with caution.

Monthly household income also had a significant association with women’s dietary diversity. An increase in income of 10 000 leads to an increase of 0.844 in score. This is similar to other study findings among women in Southern Ethiopia (Delil et al., Citation2021; Gudeta et al., Citation2022) and Central Ethiopia (Desta et al., Citation2019). Increased income enables economic access to food and may enable procurement of a diverse diet (Carletto et al., Citation2017; Ogutu et al., Citation2020).

Being a beneficiary to an agricultural development project leads to an increase of 0.472 in the score. While the objectives of the particular agricultural program are not known, it is an important positive that involvement is associated with an increased diet diversity. When agricultural programs are nutrition-sensitive, they yield a positive nutrition outcome (Carletto et al., Citation2017; Schönfeldt et al., Citation2017; Sharma et al., Citation2021).

3.5. Determinants of children’s dietary diversity

Children’s reliance on adults for their wellbeing makes them even more vulnerable to malnutrition (Gibson, Citation2016). As seen in Table , the association between the caretaker’s educational status and child dietary diversity is statistically significant. Children whose caretakers have attained a higher level of education, have a higher dietary diversity score than their counterparts. An increase in one level of education of the respondent leads to an approximate increase of 0.377 in score. Consistently, studies in Nigeria (Olutosin Ademola Otekunrin et al., Citation2022), Madagascar (Rakotonirainy et al., Citation2018) and Indonesia (Sekartaji et al., Citation2021) showed that a poor educational status was associated with a less varied diet. Study findings in Ethiopia (Sisay et al., Citation2022) differ as there was no statistically significant association between educational status and children’s dietary diversity score. Thus, a high educational status will not always translate into adequate dietary diversity.

Table 3. Determinants of child dietary diversity score

Gender was also significantly associated with the score. If the caretaker is male, it leads to a decrease in score of 1.342. This can be attributed to women assuming the responsibility of taking care of the children in most communities (Fongjong, Citation2022; James et al., Citation2022). Women are responsible for growing, purchasing, processing and preparing most of the food, which is consumed (Gibson, Citation2016), which could justify their greater influence of children’s consumption of adequately diverse diets.

While study findings in Southern Ethiopia (Lencha et al., Citation2022) and Zambia (Marinda et al., Citation2018) did not show a significant association, the present study shows that marital status was also significantly associated with dietary diversity. If the caretaker is married, then there is an increase of 1.142 in the children’s dietary diversity score. Other study findings in North Ethiopia (Dinku et al., Citation2020) found similar results. It can be assumed that being married may result in shared responsibilities in bringing up a child and thus enable provision for a more diverse diet.

4. Strengths and limitations

The study employed a 24 hour recall only, for the assessment of dietary diversity of women of reproductive age and under-five children from the surveyed farming households. Another limitation is that the responses of the participants were determined by what they could remember. The study has representation of farming household from the four agroecological zones in Lesotho, but the findings cannot be generalised to all women and children in Lesotho. The sample size for under-five children was less than 100, which may not be sufficiently representative. However, the findings contribute to limited literature pertaining to the dietary quality of women and children in Lesotho. It will inform evidence-based decision making for the enhancement of food and nutrition security among farming households.

5. Areas for further studies

Further research for the assessment of dietary diversity among all women of reproductive age and under-five children in Lesotho may be carried out, and that is not limited to farming households.

6. Conclusion

Low dietary diversity among women of reproductive age and under-five children is a concern in Lesotho and other African and Asian countries. It is a concern that majority of the women and children from the surveyed farming households had low diversity in their diets. Household members from farming households are expected to have diverse diets as a result of their agricultural production and/or income generated from the sale of agricultural produce, but it is not the case with the surveyed farming households.

The determinants for women’s dietary diversity score are age group, total members of the household, monthly income and being a beneficiary of an agricultural development program. Child dietary diversity score was significantly associated with educational status, gender and marital status of the respondent/caretaker. Women’s dietary diversity is significant for their own health and that of the children, as it determines the child’s growth and development. These factors must be considered in tailoring interventions for improving food and nutrition security among these groups.

7. Recommendations emanating from the study

There is need for raising awareness among farming households on the importance of diverse diets for women and children. It is recommended that a nutrition-sensitive approach to agricultural interventions be adopted, as it is concerning that farming households are involved in food production and yet they are also vulnerable to malnutrition. To achieve nutrition outcomes through involvement in agriculture, capacitation on agricultural production only is not enough; farming households must also be equipped with nutrition knowledge. There must be strategies to regulate the high cost of food to enable households to afford nutrition and diets that meet the nutritional requirements of all members of the households.

Availability of data

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was made possible through a capacity-building competitive grant: Training the next generation of scientists provided by Carnegie Cooperation of New York through the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM).

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nthabeleng Nkoko

Nthabeleng Nkoko is a doctrate student in Consumer Science specialising in Food and Nutrition Security and Commercial Agriculture, at the University of the Free State. She is a laboratory technician and teaching assistant at the National University of Lesotho. Her research interests include food and nutrition security, nutrition-sensitive food value chains, diversification of livelihood strategies and community development.

Natasha Cronje

Natasha Cronjé is currently a lecturer in the Department of Sustainable Food Systems and Development, University of the Free State. She is responsible for all the undergraduate and postgraduate teaching of Food Security. The vast scope of Food Security research and, her interest in sustainability ultimately lead to research on household food waste practices of South Africans. Other research activities include exploring product development as a possible mitigating tool to reduce food waste, consumer perceptions and attitudes surrounding these topics and the effect of household activities on their food security status.

Jan Willem Swanepoel

Jan Willem Swanepoel The strife to further develop his professional acumen and his passion for making a difference in people’s lives, led him to become part of the University of the Free State. He left the private industry at the end of 2015 and joined the university. Currently, he is an Associate Professor and affiliated to the Department of Sustainable Food Systems and Development at the University of the Free State. Some of his current responsibilities include the leading of the Centre for Sustainable Agriculture and the Development part of the department. His field of expertise include agriculture economics, where he correspondingly developed a new curriculum for Masters and Honors students in Sustainable Agriculture. Furthermore, he is managing all third-stream and community projects of the department and assisting the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences with business planning.

References

- Abdullah, Zhou, D., Shah, T., Ali, S., Ahmad, W., Din, I. U., & Ilyas, A. (2019). Factors affecting household food security in rural northern hinterland of Pakistan. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 18(2), 201–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2017.05.003

- Aboagye, R. G., Seidu, A., Ahinkorah, B. O., Arthur-Holmes, F., Cadri, A., Dadzie, L. K., Hagan, J. E., & Eyawo, O. (2021). Months in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients, 13(3431), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103431

- Adubra, L., Savy, M., Fortin, S., Kameli, Y., Kodjo, N. E., Fainke, K., Mahamadou, T., Le Port, A., & Martin-Prevel, Y. (2019). The Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women of reproductive age (MDD-W) indicator is related to household food insecurity and farm production diversity: Evidence from rural Mali. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzz002

- Bellows, A. L., Canavan, C. R., Blakstad, M. M., Mosha, D., A, N. R., Webb, P., Kinabo, J., Masanja, H., & Fawzi, W. (2017). The relationship between dietary diversity among women of reproductive age and agricultural diversity in rural Tanzania Alexandra. Physiology & Behavior, 176(3), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.014.CagY

- Bureau of Statistics (BOS). (2016). Country report. https://www.bos.gov.ls/Publications.htm

- Carletto, C., Corral, P., & Guelfi, A. (2017). Agricultural commercialization and nutrition revisited: Empirical evidence from three African countries. Food Policy, 67, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.020

- Chakona, G., & Shackleton, C. Minimum dietary diversity scores for women indicate micronutrient adequacy and food insecurity status in South African Towns. (2017). Nutrients, 9(8), 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080812

- Christian, A. K., & Dake, F. A. A. (2022). Profiling household double and triple burden of malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: Prevalence and influencing household factors. Public Health Nutrition, 25(6), 1563–1576. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001750

- Cuevas Garciá-Dorado, S., Cornselsen, L., Smith, R., & Walls, H. (2019). Economic globalization, nutrition and health: A review of quantitative evidence. Globalization and Health, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0456-z

- Custodio, E., Kayikatire, F., Fortin, S., Thomas, A. C., Kameli, Y., Nkunzimana, T., Ndiaye, B., & Martin-Prevel, Y. (2020). Minimum dietary diversity among women of reproductive age in urban Burkina Faso. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 16(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12897

- Delil, R., Zinab, B., Mosa, H., Ahmed, R., & Hassen, H. (2021). Determinants of dietary diversity practice among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Wachemo University Nigist Eleni Mohammed memorial referral hospital, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One, 16(4 April), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250037

- Desta, M., Akibu, M., Tadese, M., & Tesfaye, M. (2019). Dietary diversity and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Shashemane, Oromia, Central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2019, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3916864

- Development Initiatives. (2021). Global nutrition report. https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/2021-global-nutrition-report/

- Devereux, S., Béné, C., & Hoddinott, J. (2020). Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Security, 12(4), 769–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0

- Dhuki, N. (2020). Global prevalence of malnutrition: Evidence from literature. Malnutrition, 32. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.92006

- Dinku, A. M., Mekonnen, T. C., & Adilu, G. S. (2020). Child dietary diversity and food (in)security as a potential correlate of child anthropometric indices in the context of urban food system in the cases of north-central Ethiopia. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 39(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-020-00219-6

- Drammeh, W., Hamid, N. A., & Rohana, A. J. (2019). Determinants of HH F-insecurity and its association with child malnutrition in Africa [Lit. Review].Pdf. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science, 7(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.12944/CRNFSJ.7.3.02

- Edris, M. M., Atnafu, N. T., & Abota, T. L. (2018). Determinants of dietary diversity score among children age between 6-23 months in Bench Maji Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 9(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.21767/2574-2817.100035

- FAO. (2018). Dietary assessment. Dietary Assessment: A Resource Guide to Method Selection and Application in Low Resource Settings. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003210368-2

- FAO. (2019). Contributing to agriculture, food security, nutrition and rural development. https://lesotho.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FAOadvocacybrochure.pdf

- FAO, . (2021). Minimum dietary diversity for women. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb3434en

- Fongjong, L. (2022). The role of women’s nutrition literacy in food security: The case of Africa. Issue 572.

- Fox, A., Feng, W., & Asal, V. (2019). What is driving global obesity trends? Globalization or “modernization”? Globalization and Health, 15(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0457-y

- FSIN. (2022). Global report on food crises 2022. In May. https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/GRFC 2022 Final Report.pdf

- Galasso, E., & Wagstaff, A. (2019). The aggregate income losses from childhood stunting and the returns to a nutrition intervention aimed at reducing stunting. Economics and Human Biology, 34(August), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.01.010

- Gibson, M. (2016) The feeding of the nations redefining food security for the 21st century. First Edit CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11576

- Gitagia, M. W., Ramkat, R. C., Mituki, D. M., Termote, C., Covic, N., & Cheserek, M. J. (2019). Determinants of dietary diversity among women of reproductive age in two different agro-ecological zones of Rongai sub-county, Nakuru, Kenya. Food and Nutrition Research, 63, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.29219/fnr.v63.1553

- Gudeta, T. G., Terefe, A. B., Mengistu, G. T., Sori, S. A., & Chigusa, Y. (2022). Determinants of dietary diversity practice among pregnant women in the Gurage Zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021: Community-based cross-sectional study. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2022, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8086793

- Herrera Cuenca, M., Proaño, G. V., Blankenship, J., Cano-Gutierrez, C., Chew, S. T. H., Fracassi, P., Keller, H., Venkatesh Mannar, M. G., Mastrilli, V., Milewska, M., & Steiber, A. (2020). Building global nutrition policies in health care: Insights for tackling malnutrition from the academy of nutrition and dietetics 2019 global nutrition research and policy forum. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(8), 1407–1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2020.03.011

- IFAD, F. A. O., UNICEF, W. F. P., & WHO. (2022). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable. https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/cc0639en.pdf

- James, P. T., Wrottesley, S. V., Lelijveld, N., Brennan, E., Fenn, B., Menezes, R., & Mates, E. (2022). Women’s Nutrition | A Summary of Evidence, Policy and Practice Including Adolescent and Maternal Life Stages Women’s Nutrition A Summary of Evidence, Policy and Practice Including Adolescent and Maternal Life Stages Acknowledgements Recommended Citation Issue January 2022. www.tnightdesign.com

- Keno, S., Bikila, H., Shibiru, T., & Etafa, W. (2021). Dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6 to 23 months in Chelia District, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatrics, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-03040-0

- Kheleli, R. M., Jing, Z., Mofolo, T. C., & Mwandiringana, E. (2021). Adaptation to climate change: Status, household strategies and challenges in Lesotho. International Journal of Scientific Advances, 2(3), 365–370. https://doi.org/10.51542/ijscia.v2i3.21

- Lencha, F., Zaza, Z., Digesa, L., & Ayana, T. (2022). Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among children under the age of five attending public health facilities in Wolaita Soddo town, Southern Ethiopia, 2021: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14861-8

- Li, X., Yadav, R., & Siddique, K. H. M. (2020). Neglected and underutilized crop species: The key to improving dietary diversity and fighting hunger and malnutrition in Asia and the Pacific. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7(November), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.593711

- Ma, K., Hidayat, S. I., Butula, N., Korzeniowska, M., Föste, M., Sinamo, K. N., Chodaczek, G., & Yang, B. (2022). Factors affecting the young generation reluctance to be farmer. Current Research in Food Science, 5(7), 1955–1964. https://doi.org/10.47191/jefms/v5-i7-13

- Makonnen, B., Venter, A., & Joubert, G. (2003). A randomized controlled study of the impact of dietary zinc supplementation in the management of children with protein-energy malnutrition in Lesotho. II: Special investigations. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 49(6), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/49.6.353

- Marinda, P. A., Genschick, S., Khayeka-Wandabwa, C., Kiwanuka-Lubinda, R., & Thilsted, S. H. (2018). Dietary diversity determinants and contribution of fish to maternal and underfive nutritional status in Zambia. PLoS ONE, 13(9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204009

- Melesse, M. B. (2021). The effect of women’s nutrition knowledge and empowerment on child nutrition outcomes in rural Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics (United Kingdom), 52(6), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12668

- Muroyiwa, B., & Linakane, T. T. (2021). Factors affecting food security of rural farmers in Lesotho: The case of Keyhole Gardeners in Leribe District. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 59(1). https://doi.org/10.17306/j.jard.2021.01397

- Myatt, M., Khara, T., Schoenbuchner, S., Pietzsch, S., Dolan, C., Lelijveld, N., & Briend, A. (2018). Children who are both wasted and stunted are also underweight and have a high risk of death: A descriptive epidemiology of multiple anthropometric deficits using data from 51 countries. Archives of Public Health, 76(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-018-0277-1

- Nair, M. K., Augustine, L. F., & Konapur, A. (2016). Food-based interventions to modify diet quality and diversity to address multiple micronutrient deficiency. Frontiers in Public Health, 3(January), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00277

- Ogutu, S. O., Gödecke, T., & Qaim, M. (2020). Agricultural commercialisation and nutrition in smallholder farm households. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 71(2), 534–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12359

- Oot, L., Sethuraman, K., Ross, J., & Diets, A. E. S. (2016). Effect of chronic malnutrition (stunting) on learning ability, a measure of human capital : A model in profiles for country-level advocacy. In Technical brief, food and nutrition technical assistance III project (Issue February). https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/PROFILES-brief-stunting-learning-Feb2016.pdf

- Otekunrin, O. A., & Otekunrin, O. A. (2021a). Healthy and sustainable diets: Implications for achieving SDG2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69626-3_123-1

- Otekunrin, O. A., Otekunrin, O. A., Ayinde, I. A., Sanusi, R. A., Onabanjo, O. O., & Ariyo, O. (2022). Dietary diversity, environment and health-related factors of under-five children: Evidence from cassava commercialization households in rural South-West Nigeria. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(13), 19432–19446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17221-y

- Rakotonirainy, N. H., Razafindratovo, V., Remonja, C. R., Rasoloarijaona, R., Piola, P., Raharintsoa, C., Randremanana, R. V., & Chen, W. (2018). Dietary diversity of 6- to 59-month-old children in rural areas of Moramanga and Morondava districts, Madagascar. PLoS ONE, 13(7), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200235

- Ranneileng, M. (2013). Impact of a nutrition education intervention on nutritional status and nutrition‐ related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of Basotho women in urban and rural areas in Lesotho. University of the Free State. https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/handle/11660/1796.

- Ranneileng, M., Nel, M., & Walsh, C. M. (2023). Impact of a nutrition education intervention on nutrition-related self-efficacy and locus of control among women in Lesotho. Frontiers in Public Health, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1060119

- Rantšo, T. A., Seboka, M., & Yildiz, F. (2019). Agriculture and food security in Lesotho: Government sponsored block farming programme in the Berea, Leribe and Maseru Districts. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1657300. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1657300

- Rothman, M., Ranneileng, M., Nel, R., & Walsh, C. (2019). Nutritional status and food intake of women residing in rural and urban areas of Lesotho. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 32(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/16070658.2017.1415783

- Schönfeldt, H. C., Pretorius, B., & Hall, N. (2017). Nutrition-sensitive agricultural development for food security in Africa: A case study of South Africa. International Development, 32(1), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.5772/67110

- Sekartaji, R., Suza, D. E., Fauziningtyas, R., Almutairi, W. M., Susanti, I. A., Astutik, E., & Efendi, F. (2021). Dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Indonesia. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 56, 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.10.006

- Setyawan, F. E. B., & Lestari, R. (2021). Holistic-comprehensive approaches to improve nutritional status of children under five years. Journal of Public Health Research, 10(2), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2183

- Shaifuddin, S. N. M., Azmi, A., Ghazali, S. N. F. M., & Shahid, N. S. M. (2022). Food accessibility and movement control order: Analyzing impact of first lockdown on access to food. Malaysian Journal of Medicine and Health Sciences, 18(8), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.47836/mjmhs18.8.24

- Sharma, I. K., DiPrima, S., Essink, D., & Broerse, J. E. W. (2021). Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: A systematic review of impact pathways to nutrition outcomes. Advances in Nutrition, 12(1), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmaa103

- Sisay, B. G., Afework, T., Jima, B. R., Gebru, N. W., Zebene, A., & Hassen, H. Y. (2022). Dietary diversity and its determinants among children aged 6-23 months in Ethiopia: Evidence from the 2016 demographic and health survey. Journal of Nutritional Science, 11(6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2022.87

- Sonandi, A. (2018). Determining the nutritional status of children from agribusiness families in the Easter Cape, South Africa. University of the Free State. https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/handle/11660/9245

- Tine, J. A. D., Niang, K., Faye, A., & Dia, A. T. (2018). Assessment of women’s dietary diversity in Southern Senegal. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 09(10), 1192–1205. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2018.910086

- UNDP. (2023). The sustainable development goals. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals

- Walsh, C. M., Fouché, M. S., Nel, M., & Booysen, F. (2020). The impact of a household food garden intervention on food security in Lesotho. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228625

- WFP. (2020). Lesotho annual country report 2020. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000125447/download/

- WFP. (2021). Conceptual framework on maternal and child nutrition. In Nutrition and child development section, Programme Group 3 United Nations Plaza . www.unicef.org/nutrition

- WFP. (2023). WFP Lesotho Country Brief Issue December 2015. https://reliefweb.int/report/lesotho/wfp-lesotho-country-brief-january-2023

- WFP, & UNICEF. (2019). Fill the nutrient gap Lesotho Issue August 2019. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000107436/download/?_ga=2.103366016.1211658258.1606732957-2124740740.1606732957

- Wijaya, O., Yogyakarta, U. M., Widodo, W., Yogyakarta, U. M., Rubiyanto, C., & Yogyakarta, U. M. (2020). Household dietary patterns in food insecurity areas. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.18196/agr.6298

- World Bank. (2020). Lesotho: Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lesotho

- Zezza, A., Carletto, C., Fiedler, J. L., Gennari, P., & Jolliffe, D. (2017). Food counts. Measuring food consumption and expenditures in Household Consumption and Expenditure Surveys (HCES). Introduction to the special issue. Food Policy, 72, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.08.007