Abstract

The study assessed the overall status of CBRSEM and the potential benefits accrued from the model. The sample comprised 92 respondents selected from a women-led Community-Based Rice Seed Entrepreneurship Model (CBRSEM) located in Taraganj and Shadullapur upazilas of the Rangpur and Gaibandha districts of Bangladesh, respectively, following a stratified proportionate random sampling technique. Membership in CBRSEM developed their communication skills, social relationships, and decision-making abilities while capacitating them in sowing, harvesting, and threshing. Increased access to quality seeds was ensured through easy availability at the right time in proximity. Increased yield, betterment of livelihood, and empowerment were the leading benefits. The concerns that emerged were high production cost, absence of a moisture meter, and timely roguing. Popular suggestions put forward included means to lessen the cost of agricultural inputs, provision of loans with easy terms and conditions, and training programs.

1. Introduction

Community-Based Rice Seed Production (CBRSP) aims to strengthen the production capacity of farmers through community-level seed production, farmer-to-farmer supply of quality seeds, and promotion of local seed markets. Seed is one of the critical inputs in agriculture. Bangladesh increases 10% in rice yield through the use of quality seeds (Haque et al., Citation2012). The yield of almost all crops is low in Bangladesh as compared to other countries. It is necessary to have a sufficient supply of seeds of higher quality in order to increase agricultural output (Dhakal, Citation2013). An inadequate supply of quality seeds for cereal crops is one of the important limiting factors. Currently, less than half of the farmers (46.0%) use quality seeds while the remaining use poor-quality seeds (M. S. Hossain, Citation2019).

The use of good quality seeds of improved varieties is fundamental to ensuring increased crop production and productivity. Other potential benefits accrued to farmers from the use of good quality seeds include a high crop production index, reduced risks from pests and diseases, and higher incomes (Adhikari, Citation2020; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], Citation1999). Timely supply of a sufficient quantity of high-yielding variety quality seeds increases crop yields by 15–25% (Thompson, Citation1979). Sustainable agricultural production growth necessitates the continuous development of improved crop varieties as well as the regular supply of seeds to farmers (Joshi, Citation2015).

The CBRSP approach involves organizing individual farmers and their support organizations into small seed production units to encourage social learning, supply quality seeds for farmers’ own use, and marketing of seeds to other farmers. Seed is now a controversial issue around the world as farmers’ rights are related to basic inputs and production factors. This has led to a debate that farmers must have rightful access to quality seeds (Omanga & Rossiter, Citation2004). Land ownership has been an important criterion in the identification of beneficiaries or participating farmers for various programs, but we tend to forget that historically women have been responsible for preserving the biodiversity and traditional knowledge of seeds like production, processing, storage, and even large-scale farmer-to-farmer exchange. And so, it would not be wrong to say that women own a large part of the seed system as they play a key role in managing the seed at the household level. Since these activities do not involve any cash or value-added transactions, their contributions are ignored. By ignoring their participation, we not only miss out on critical resources but also compromise on the goals of women’s empowerment and their access to income. The seed sector provides an opportunity to organize women and youth in seed production activities and help in income generation.

In this context, community-level seed production enterprises can increase farmers’ access to quality seeds and promote self-reliance in the seed sector with enhanced income opportunities. Institutionalization, value addition, marketing, or transactions need to be linked by taking advantage of the opportunities available through farmer-managed seed production enterprises. There is a dearth of research on such models while we need to understand and evaluate the impact of the seed production and enterprise model on systematic mobilization and capacity building of marginal farmers, especially women; the extent of increase in access to quality seeds by the decentralized seed production hubs; and the challenges faced by the CBRSE model. Therefore, the present study was carried out with the following specific objectives to i) describe the socio-demographic features of the women farmers; ii) assess the current status, challenges and opportunities of CBRSEM in terms of systematic mobilization and capacity building in rice seed production; and iii) evaluate the access to quality seeds as enabled by strengthening decentralized seed production hubs.

2. Methodology

The study was conducted in two Northern districts of Bangladesh, namely Rangpur and Gaibandha. Women-led CBRSE model generated by IRRI as their experimental model was selected for the present study. This rice seed business model was started in 2008 at Taraganj upazila under Rangpur district and in 2011 at Sadullapur Upazila under Gaibandha district. CBRSE model in Taraganj, Rangpur comprised 515 members and that of Sadullapur included 408. It has been implemented by Rangpur Dinajpur Rural Service (RDRS), Bangladesh, and supervised by IRRI. This model has been running guided by a Federation consisting of nine (9) members formed by RDRS. Under this Federation, there are seed management committee and seed producing groups. In each seed producing group, there are 20 general women members. All the members of the Federation are also the members of the “Krishi Kendra”. The Federation provides its members with quality rice seeds, and seed production training with the assistance of RDRS staffs. Moreover, every member of the Federation can directly communicate with the agricultural officials regarding any agricultural activity. At first, the Federation provides seeds to this Seed Management Committee for free of cost. Later on, after making profit, the farmers purchase good quality seeds from the federation. Profits earned by selling seeds are divided into three parts at every 6 months and 70.0 percent of which goes to agri-entrepreneurs, 10.0 percent to Krishi Kendra and 10.0 percent to RDRS. The remaining 10.0 percent of the profit is used for the development of the federation. The community-based rice seed production is a cost-effective approach for disseminating new rice varieties where farmer groups, farmer associations and other community-based institutions provide support to seed-related activities complementary to the public and commercial sectors.

Ninety-two members from the two CBRSEMs (10.0% of the total number of members) were selected as sample of the present study following a stratified proportionate random sampling technique. The sample included respondents from different verticals of the CBRSE program, namely the seed-producing group (62.0%), seed management committee (22.8%), Federation (6.5%), seed entrepreneurs (1.1%), rural cooperative society (6.5%) and ekti bari ekti khamar (“one house one farm” is a government project executed countrywide). The majority (89.1%) of them were general members of the CBRSE model. Both primary and secondary data were collected. Primary quantitative data were gathered through face-to-face interviews using a pre-tested interview schedule. The interview schedule was developed after a preliminary consultation with experts in the domain, field visits, and reviewing the secondary data. Qualitative information was gathered through FGDs. Selected socio-economic descriptions of women farmers included age, education, family size, and occupation, farming experience, farm size, annual family income, organizational participation, social relationship, and knowledge of rice seed production. The seed production status was measured in terms of systematic mobilization and capacity building using five-point Likert-type scales. The rank order of the items of each of systematic mobilization and capacity building was measured by calculating their mean values. Local access to quality seeds was measured using a scale consisting of (10) relevant criteria. Opportunities and challenges were measured by using five-point rating scales because it mostly indicates the opinion of the respondent in five logical continuums (Croasmun & Ostrom, Citation2011).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Socio-economic characteristics

The age of the respondents in the study ranged from 18 to 60 years. The mean age of the respondents was 37 years (Table ) which is above the national average (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [BBS], Citation2010). The highest proportion of the respondents (56.5%) was young-aged; around two-fifths (37.0%) were middle and very few (6.5%) were old-aged. This means that a large share of the respondents (93.5%) was young to middle-aged. Similar results were observed by Amin (Citation2011). It is a general assumption that young and middle-aged people are curious and interested in adopting new technologies and possess high risk-taking abilities. Hence, young and middle-aged women farmers can be motivated to be a part of the community-based rice seed entrepreneurship model.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Respondents’ levels of education varied from illiteracy to graduate levels. Results illustrated in Table indicate that the majority (71.8%) of the respondents had primary to secondary education and only 7.6% had higher secondary education. A mentionable portion (14.1%) of them had not received any education and 5.4% could only sign their names. These findings have the conformity with those of M. S. Rahman et al. (Citation2018) reported on assessment of crop production training needs for farmers in some areas of Bangladesh. The findings are important as the probability of farmers getting engaged in the CBRSE model and using it to meet local demand for seeds is high when they are educated.

The average number of members in a household was 4.9 which is close to the national average (4.26) (Global Data Lab, Citation2020). It was found that about three-fifths (50.0%) of the respondents’ families were medium-sized, 44.6% were small, and only 5.4% were large. These findings are consistent with those of Rahaman et al. (Citation2021) who studied on cost-effectiveness analysis of boro rice production in Bangladesh and reported that 43.75% of respondents had primary education while 26.25% did not have formal schooling. Survey results also indicate that 60%, 27%, 13% of the respondents had small, medium, and large farms, respectively; and the prime occupation of around 77% of them was farming in the study area. On average, farming experience ranged from 21 to 30 years for 42.25% of farmers. As observed during the interviews, the majority of the respondents were middle-aged and their children were married and lived in different houses. So, small to medium-sized families were common.

The farming experience of the respondents was categorized into low, medium, and high (Yasmin et al., Citation2014). From Table , most of the respondents (52.2%) had low experience, about one-third (33.7%) had medium experience, and the rest 14.1% were highly experienced. With nearly half of the respondents in the medium and highly experienced category, it is believed that the information provided by them was valid. Akter et al. (Citation2019) found similar results on a study about factors influencing rice farming profitability in Bangladesh and found that most of the farmers were under the small farmer’s category according to the classification of Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS, Citation2015) and they were extensively experienced (35 years) in rice farming. Small farm size is expected to contribute to lower production, thereby, lower profit, whereas experienced farmers are assumed to be the higher profit earner due to their better skill and management practice in the rice field. All the respondents were actively engaged in agriculture. Also, the majority (66.3%) had no secondary occupation; the rest were involved in business activities (22.8%), livestock rearing (3.3%), and other services (7.6%). Similar results were reported by Akter et al. (Citation2019) in a study on factors influencing the profitability of rice farming in Bangladesh. On the contrary, M. S. Hossain et al. (Citation2021) found dissimilar results in their study about the role of training in the transfer of rice production technologies to farm level.

It is evinced from the data in Table that more than half of the respondent women (55.4%) had marginal landholdings followed by those with small-sized lands (43.5%). It can be assumed that marginal and small farm holders depend much on agriculture. The average farm size of the respondents was 0.22 ha, which was found lower than the national average (0.6 ha) reported by Khan (Citation2021). S. M. Rahman and Al-Amin (Citation2016) obtained a similar pattern of farm holdings by farmers on measuring production cost differences of boro rice farming in Bangladesh and stated that most of the large and solvent farmers are using their own fund by purchasing input in cash which causes lowering the cost of production and these types of farmers are not bound to sell their product immediately after harvesting, keeping the product for the lean period for higher prices.

It can be assumed that small and marginal farmers constitute the predominant group of farmers. The annual income of the respondents ranged from USD200 to 6000. The mean income was USD 1344.67 which is quite close to the per capita annual income (USD1344.4) of Bangladesh (Trading Economics, Citation2021). It shows that the distribution of annual income was skewed. A majority (52.2%) of the respondents had medium annual income, 19.6 percent had medium annual income and 28.3 percent had high annual income. The skewed nature of income may be explained by the cases of large farm holdings and those (more than 30%) engaged in multiple sources of livelihood. This finding has the conformity with those of Basak and Pandit (Citation2011) on farmers’ attitudes toward the use of USG in rice cultivation and reported that the respondents’ annual income ranged from Tk. 29 to 290 thousand where most of the respondents (64.29%) were in medium income category.

Multiple sources of information were used by the respondents for their agricultural needs. The primary sources identified were the federation committee of CBRSE (96.7%), group leaders of CBRSE (92.4%), seed dealers of CBRSE (90.2%), and RDRS employees (89.1%). Other less prominent sources of agricultural information were friends and other agri-input dealers. The more agricultural information indicates the more scope of betterment in agricultural production. More effectively to get agricultural information and farmers with more knowledge expected to be more efficient in regarding agricultural practices. The results had congeniality with the findings of M. S. Rahman et al. (Citation2018) on the study of training needs on crop production for farmers in Bangladesh.

More than four-fifths (83.7%) of the respondent women had received training on subjects related to agriculture. Among the trained respondents, a large share (70.13%) had received training on seed production and 29.9% on seed management who were belonged to medium to long training exposure. The results have the conformity with the study of Basak and Pandit (Citation2011) in their study on farmers’ points of view on the use of USG in rice cultivation. They reported that about 45% of the farmers had low exposure to different agricultural trainings and only 4.76% had medium to high training exposure. However, half of them (50%) had no training exposure. Most of them received training from RDRS (Rangpur Dinajpur Rural Service) and the upazila level agriculture office. More than four-fifths (81.5%) fully utilized their learnings from the training and a very small percentage (2.2%) utilized the knowledge gained only partially. The rest of the them (16.3%) had no utilization of their gathered training outcome. It can be true in two dimensions, i) the wrong personnel were selected as the trainee and ii) the trainings were unable to make them capable in doing the related things efficiently. Noor and Dola (Citation2011) reported the similar results in their study on investigating the effect of training on farmers’ perception and performance.

Results in Table show that the majority (67.4%) of the respondents had a low level of organizational participation while medium and high levels of organizational participation were reported by 17.4% and 15.2%, respectively. As all the respondents were women, it is understood that their involvement in household chores would have led to difficulties in time management. According to the findings, respondents who participated in an organization had higher rice yield and were technically more efficient than farmers who did not participate. These findings have conventionality with those of Bairagi and Mottaleb (Citation2021) who conducted their study on farmers’ participation in organizations and production efficiency. Their findings indicated that farmers who participated in an organization had higher rice yield (11% more) and were technically more efficient (1.4% higher) compared to farmers who did not participate.

The innovativeness score of the respondents ranged from 0 to 50 and the average score obtained was 35.9. According to the findings in Table share of respondents in the high (41.3%) and low (40.2%) innovativeness categories were not very different but 18.5% were moderately innovative. With 59.8% in the moderate-to-high innovativeness category, the findings are similar to those of Prodhan and Afrad (Citation2014). The higher the innovativeness score, the greater the chance of using modern tools and techniques by the respondent women farmers. Innovative farmers are more prone to adopt new technologies and hence they can be motivated for adoption. Shah et al. (Citation2016) in their study on farmers’ innovativeness and hybrid rice diffusion in Bangladesh got the results conformity with this study.

It is evinced from Table that maximum (95.7%) of the respondent possessed high knowledge on quality rice seed. Very few (4.3%) of them had moderate knowledge on the same issue. Generally, substantial knowledge on anything helps an individual for its efficient use. Jaganathan et al. (Citation2016) found different results in their study on knowledge level of farmers on organic farming.

3.2. Status of seed production

Seed production status included was measured in terms of the systematic mobilization of the women seed producers in ten different aspects as presented in Table , and the status of their capacity building in 11 different areas as mentioned in Table . While the capacity-building parameters mostly centered on efficiency in the seed production operations, systematic mobilization was mostly about social and entrepreneurial skills.

Table 2. Rank order of systematic mobilization issues

Table 3. Rank order of capacity building in different operations

3.2.1. Systematic mobilization

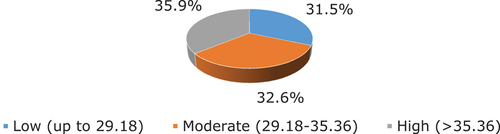

The findings shown in Figure indicate that for more than one-third of the respondents (35.9%) the scale of mobilization was high, and a similar percentage was observed in the moderate (32.6%) and low (31.5%) categories. Thus, for more than two-thirds (68.5%), moderate to high-level mobilization was achieved. The results are in conformity with those of Zappi (Citation1991) who studied the mobilization of women workers in the Italian rice fields.

As a participant in the CBRSE program, the respondents received the necessary support and guidance in developing communication skills and leadership qualities; access to credit, education, health care services, and modern technologies; securing social status and decision-making abilities. Results shown in Table indicate that the highest level of improvement occurred in communication skills with an average score of 3.52 (out of 4.0) followed by social relationships (3.46) and decision-making ability (3.43).

Communication skills might have improved due to their collective involvement in different activities, viz. foundation seed collection, land selection, land preparation, raising seedlings, seedling transplantation, weeding, roguing, harvesting, threshing, processing, drying, optimum moisture determination, preservation, packaging, and marketing. Such group activities improve social relationships and group dynamics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, Citation2014) reported the similar findings with the current study in Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh. Involvement in a range of activities also leads to better awareness and knowledge. So, the participants become confident and take their own decisions promptly and efficiently.

3.2.2. Capacity building

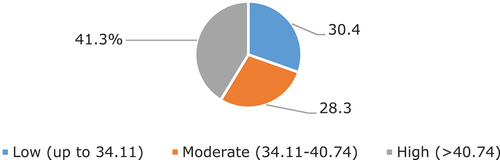

Capacity building is critical for both individual and group-level activities. Based on the scores, the level of capacity building was high for the majority of the women producers (41.3%), moderate for 28.3%, and low for 30.4% (Figure ). The low level of capacity building, as reported by a sizeable section, could be because of the poor respectability of the participants, possibly linked to education, or lack of training in some technical aspects. Capacity building can be a long process and depends on the motivation of the trainees as well as trainers.

The respondents were exposed to different skill enhancement programs that focused on the different operations in the seed production process. Information contained in Table shows the rank order of the skills in different operations.

The average score for almost all the skill sets was around 3.5. Proficiency in threshing, sowing, harvesting, cleaning, and winnowing was marginally higher than for other operations. Overall, the capacity building of the participants was evident in all the operations. Seed production requires more diligence than usual crop production. Adoption of recommended package of practices is essential during the critical stages, processing, and preservation in particular; else quality seeds may not be produced.

The results showed that the women farmers had low-capacity building in land preparation and ranked 11th in position. This may indicate that they are not proficient in preparing the land properly, even when all other activities are carried out correctly. Land preparation is traditionally performed by male farmers, which could explain the low capacity for land preparation among the women farmers. These findings are similar to those of Islam et al. (Citation2010), who conducted a study on policy options for quality seed production and cereal crop preservation at the farmer level to improve food security.

3.2.3. Perceived benefits

The benefits, as perceived by the participants, will affect their long-term engagement in this model. A good percentage of the respondents (67.5%) acknowledged the benefits received in the moderate-to-high category (Table ). This is a positive outcome that can have a long-term impact on the intensity of involvement and success of the program. However, the cases where a low scale of benefits was reported need to be explored for improving the efficiency of the program.

Table 4. Distribution of the respondents according to their perceived benefit accrued from CBRSE

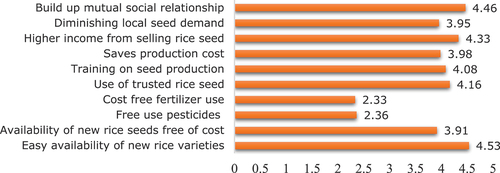

Among the accrued perceived benefits of the respondents shown in Figure , “easy availability of new rice varieties” ranked 1st, followed by “build up mutual social relationship” and “higher income from selling rice seed” ranked 2nd and 3rd, respectively. It means that the respondents of the study benefitted by getting new rice varieties easily. They became very interested in producing new varieties of seeds.

Figure 3. Rank order of perceived benefit accrued through community-based rice seed entrepreneurship model.

This model built up mutual social relationship among the respondents from where they earned high income from selling rice seed. It means that during the production period, they are engaged in intensive communication among them which strengthens their social network essentials for living in the society as human being. These findings have the conformity with those of M. M. Hasan et al. (Citationn.d..) in their study who worked on improving access to quality vegetable seeds for poor farmers.

3.2.4. Challenges

CBRSE model was found to encounter some challenges like other similar models. According to the scores or extent of the problems reported in Table , 38.1% of them perceived the challenges as major, while 30.4% as moderate, and 31.5% as minor. Therefore, more than two-thirds (68.5%) of them encountered moderate-to-high challenges in practicing CBRSEM. Generally, challenges and adoption of any new idea, policy or technology are positively correlated. It means that if there is enormous constraints, there would be less adoption of any new idea, policy, technology and system. On the other hand, low challenge associated idea, policy or technology would be highly adopted by the individuals. Rogers (Citation2003) claimed that if an innovation is perceived to be advantageous; is compatible with existing norms, beliefs, and past experiences; has a relatively low level of complexity; can be experimented with; and use of the innovation has observable results, including being able to see others using the innovation, then there will be an increased likelihood of adoption.

Table 5. Distribution of the respondents based on their perceived challenges encountered in CBRSEM

The average score of each challenge was computed using a four-point rating scale. Results shown in Table indicate that the major constraints were the shortage of moisture meters, high production cost, timely roguing, obligatory line transplanting, and the need for extra labour.

Table 6. Rank order of the challenges identified by the respondents

The moisture meter is used for the frequent determination of the moisture content in rice seeds. For short-term storage of rice seeds, it is essential to maintain 14.0% moisture content but if it is to be preserved for more than 1 year, it is important and obligatory to maintain 12.0% moisture content. The price of a moisture meter ranges from USD100 to 200 based on the functions and brand. Unfortunately, rural women involved in the CBRSE program cannot afford this essential but costly device. Despite lack of moisture meter, they have to store the seeds based on their assumption without checking of moisture content. After some time, they check their stored seeds. If there is any damage to their stored seeds, they have to buy fresh seeds in the following year when required. This increases their production costs. Dey et al. (Citation2022) observed that most seed producer groups experience difficulties in accessing good-quality early generation seed (EGS) on time, like in the formal seed sector in many countries. Second, in most groups packaging and labelling of the seed produced and offered in local markets is suboptimal, hindering further professionalization. Moreover, groups invariably have a poor understanding of applicable seed policy and legislation. Rana and Rahaman (Citation2021) pointed out the analogous results in their study on problems faced by vegetable growers in vegetable production and marketing.

Rice seed production requires a range of inputs, constant care, and extra labor because of the possibility of damage and loss in quality. Processing also requires utmost care. Also, rice seed production consumes more inputs than that normal rice grain production, and the high cost of inputs becomes burdensome for the participants. Again, lack of credit during the production period is also a concern. Roguing is an important activity in rice seed production. Roguing is performed in three stages, viz. seedling, growth, and flowering stages. If roguing is not performed properly in these three stages, there is the possibility of contamination of rice seed by other unwanted seeds which degrades the seed quality and consequently lowers the price of the seed. Hence, they found roguing to be another challenge.

3.2.5. Perceived opportunities

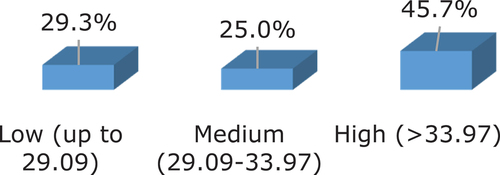

The opportunities offered by a program make the participants optimistic about future benefits. Participants of CBRSEM perceived different kinds of opportunities for themselves. Most of them had high expectations (45.7%) and 25.0% of them felt there could be a moderate level of prospects (Figure ).

Despite the challenges, the members could realize the opportunities like higher yields, secured livelihood, empowerment, higher income, food security, etc. (Table ). All the criteria listed were reported as important from the respondents’ perspective.

Table 7. Rank order of perceived opportunities identified by the respondents

Generally, among the many traits of any crop variety, high yield is of utmost importance. After yield, other traits like shape, aroma, color, resistance to pests, etc. are desirable. Rice is the staple food of Bangladesh; therefore, high yield is an important selection criterion. The benefits of using own seed of a promising variety are high and the CBRSE model offers this opportunity. Higher yield and better livelihood are strongly linked. Participation of women offers the added advantage of women empowerment and a better chance to improved socio-economic conditions. Phala (Citation2019) in a study on farmers’ perceptions of community-based seed production schemes found almost similar results.

3.3. Access to quality seed

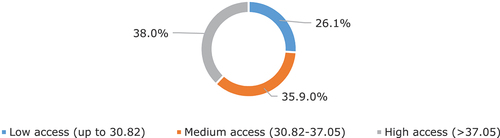

Availability of quality seed in proximity may not ensure its access by farmers. The seed production model is an attempt to address this issue. Information presented in Figure indicates that around three-fourths (73.9%) of the respondents had moderate-to-high access to quality seeds due to their involvement in the CBRSEM. As the CBRSE program is in the early phase, a section of the participants is yet to receive the benefits.

Scores presented in Table reveal that respondents’ access to quality seeds increased in terms of availability of quality seeds within their vicinity, procuring seeds without hassle, choice of quality and quantity, availability at right time and right prices, etc. This facilitates easy access at the time of their use in the subsequent years. Different results were reported by S. Hossain (Citation2020) in a study on farmers of Bangladesh who had lack of access to quality seeds. Overall, in all possible aspects, the model is successful in terms of providing easy access to quality seeds. The impact can be huge in terms of achieving food security.

Table 8. Rank order of access to quality rice seed issues

3.4. Relationship between the independent and predictive variables

Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to investigate the relationships among the selected characteristics of the respondents and seed production issues (Table ). The null hypothesis was

Table 9. Relationship among the selected characteristics of the respondents and their seed production issues

“There is no significant relationship among the selected characteristics of the respondents and their seed production issues generated from the community-based rice seed entrepreneurship model”.

The results shown in Table indicate that there is a significant positive relationship between the age of the respondent women farmers and their perceived benefits from the community-based rice seed entrepreneurship model. The older women respondents had more experience and thus perceived greater benefits from the model compared to the younger one. This indicates that with increasing experience in a particular field, the perception of benefits generated from that field increases. These findings are similar to the results of Sharifuddin et al. (Citation2016) who found that as farmers’ ages increased, so did their experience, leading to an increased perception of benefits from their profession.

The correlation between family size and their systematic mobilization (r = −0.232*) was negatively significant. Therefore, the null hypothesis could not be accepted. This means that women farmers with larger families may face difficulties in participating in activities outside the household due to their responsibilities and may have limited resources, leading to lower mobilization. Thus, it can be concluded that family size may act as a constraint for women farmers in terms of their systematic mobilization and involvement in community-based seed production activities. These findings suggest that initiatives aimed at empowering women farmers should consider the impact of family size on their mobilization and find ways to mitigate its effects. The findings have conformity with the study by Twumasi et al. (Citation2020) who found that farmers with larger family sizes had less credit available to them. As a result, they were less mobilized in any activity, including farming.

The results showed that there was a strong and significant positive relationship between the amount of farming experience and the perceived benefit of CBRSEM. This means that individuals with more farming experience tended to believe that the model was more useful, and they are able to see its value quickly. On the other hand, those with less farming experience found it less beneficial. Similar findings were reported by Sharifuddin et al. (Citation2016).

The results indicate that there was a strong and significant positive relationship between the annual income of the respondents and their capacity building, access to quality rice seed, perceived benefit of the model, and perceived opportunity of the model. This means that if the respondents’ annual income increased, it would likely lead to an increase in their access to quality rice seed, capacity building, perceived benefit, and perceived opportunity, and in turn, improve their socio-economic condition. This aligns with the findings of Kamruzzaman and Takeya (Citation2008), who reported that farmers with high capacity building abilities earn more income and have greater access to quality seed compared to farmers with low capacity building abilities.

There was a strong and significant negative relationship between the sources of agricultural information and capacity building, access to quality rice seed, and perceived opportunity of the model. This means that the more contact the respondents had with sources of agricultural information, the lower their capacity building, access to quality rice seed, and perceived opportunity. Wyss et al. (Citation2018) found similar results in their study on farmers’ access to quality and diverse seed in Nepal, where they discovered that farmers did not gather seeds from a variety of sources, but instead obtained information from a few trustworthy sources and seeds from those sources.

There was a strong and significant positive relationship between the training experience of the respondents and the challenges they faced. This indicates that farmers having more training experience had a better understanding of different aspects of future impacts, and as a result, were better prepared to handle challenges. Noor and Dola (Citation2011) found similar results in their research on the impact of training on farmer perception and performance, where they discovered that farmers who received training became much better farmers, and were more equipped to face challenges when they arose.

The organizational participation of the respondents and their systematic mobilization, capacity building, access to quality rice seed, perceived benefit of CBRSEM, and perceived opportunity of CBRSEM showed positive and significant relationship. This means that as the respondents’ organizational participation increased, so did their systematic mobilization, capacity building, access to quality rice seed, perceived benefit of CBRSEM, and perceived opportunity of CBRSEM. These findings are in line with those of Istaitih et al. (Citation2020), who studied the factors that influence farmers’ participation in informal wheat seed production in Palestine, and found similar results.

The innovativeness of the respondents was negatively related to their perceived benefit of CBRSEM. This means that those who were more innovative were less likely to view the benefits of CBRSEM favorably. Being innovative means that these farmers were familiar with a wide range of innovations and were able to compare the benefits of one innovation to the benefits of another. As a result, they compared the benefits of CBRSEM with those of other innovative ideas, both native and foreign, and concluded that the benefits of CBRSEM were less. These findings contradict the results of Shah et al. (Citation2016), who studied farmers’ innovativeness and hybrid rice diffusion in Bangladesh and found different results.

Knowledge of the respondents and all their seed production issues were found to be strongly positive and statistically significant (r = 0.624** for systematic mobilization, r = 0.605** for capacity building, r = 0.623** for access to quality rice seed, r = 0.552** for perceived benefit of CBRSEM, and r = 0.0587** for opportunity of CBRSEM). This means that the more knowledge of the respondents on quality rice seed production, the higher their systematic mobilization, capacity building, access to quality rice seed, perceived benefit of CBRSEM, and opportunity of CBRSEM. The findings are consistent with those of Janani et al. (Citation2016) and Chithra et al. (Citation2018) who showed a positive relationship between knowledge level and various aspects of seed production.

4. Conclusion

Community-based rice seed entrepreneurship model tries to harness the strength of local systems to address major issues. Systematic participation of the women growers in rice seed production along with functional interaction is the strength of this model. The support of NGOs like RDRS and organizations like IRRI is also an important factor behind the success of this initiative. Insufficient supply of seed and poor training facility are the vital weaknesses which may be addressed and the model can be replicated in other locations of the country. Exposure visits to the existing locations may be arranged to demonstrate the benefits of the model. Motivational campaign on the usefulness of CBRSEM will lead to faster diffusion of the initiative.

5. Policy implications

Women farmers of CBRSEM are with low socio-economic profile but moderately capable of producing quality rice seed. Therefore, they can be motivated to continue the seed production program. Women farmers were being capable in decision-making through communication and trained in threshing, sowing and harvesting of rice seeds. Concerned authority may consider these for dissemination in other places. This model is found suitable for producing new rice varieties and increasing yield of rice; therefore, they can be rewarded to continue their efforts. As the knowledge of the respondents is correlated with their systematic mobilization, capacity building, access to quality seed, perceived benefit, perceived opportunities and challenges, therefore, their knowledge level can be improved through proper training. The present model was only on the basis on rice seed. It can be used for the other cereal crops, vegetables seed, oil seeds, etc. Only 11 variables of the women farmers were considered in this. Further study can be conducted considering other variables such as husbands’ cooperation, training need, commercialization, attitude towards CBRSEM, and aspiration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully recognize the painstaking efforts of the respondents who provided their valuable information to the researchers. The authors would also like to give special thanks to International Rice Research Institution (IRRI), Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University (BSMRAU), and Rangpur Dinajpur Rural Service (RDRS) who extended their all-out efforts for the smooth sailing of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nuruzzaman

Nuruzzaman MS student having expertize in gender issues in post harvest activities.

Afrad Md Safiul Islam

Md. Safiul Islam Afrad working as Professor with expertise in socio-economic study, gender issue, adoption, impact, and KAP survey.

Md. Enamul Haque

Md. Enamul Haque working as Professor in the areas of agricultural extension, sustainable agriculture, and agricultural.

Ashrafun Nahar

Ashrafun Nahar serving as Associate Professor in efficiency and productivity analysis, government policies on development issues, poverty reduction measures, and food security.

Muhammad Ashraful Habib

Muhammad Ashraful Habib possesses extensive knowledge and experience in seed system and product management, firm trial management, climate change, natural resource management, women-led entrepreneurship, and market system.

Swati Nayak

Swati Nayak working on strengthening seed system and enhance access, adoption and awareness new varieties, germplasm with background on technology transfer, livelihood enhancement and sustainable technology adaptation.

Saidul Islam

Saidul Islam serving in Seed Systems and product management on varietal dissemination and development activities.

Md. Mamunur Rashid

Md. Mamunur Rashid has proven experience and expertise on project/program Planning, Management & Implementation and Fund Raising & Donor Relationship Management.

Amlan Biswas

Amlan Biswas having experience in knowledge and skill in rice-based varietal traits preference.

References

- Adhikari, B. B. (2020). Community based seed production through IRRI/IAAS projects in western mid hills of Nepal: A review. Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 3(1), 320–19. https://doi.org/10.3126/janr.v3i1.27184

- Ahmed, M. B. (2003). Impact of shrimp farming on socio-economic agricultural and environmental conditions in Paikgacha upazila of Khulna district [ PhD dissertation]. Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development.

- Akter, T., Parvin, M. T., Mila, F. A., & Nahar, A. (2019). Factors determining the profitability of rice farming in Bangladesh: Profitability analysis of rice farming in Bangladesh. Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University, 17(1), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbau.v17i1.40668

- Amin, M. R. (2011). Accessibility of rural women to family decision-making process. Bangladesh Journal of Extension Education, 23(1&2), 94.

- Bairagi, S., & Mottaleb, K. A. (2021). Participation in farmers’ organization and production efficiency: Empirical evidence from smallholder farmers in Bangladesh. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 11(2), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-09-2020-0203

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2009). Yearbook of agricultural statistics in Bangladesh, ministry of planning. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Bangladesh statistical year book. Bangladesh bureau of statistics. Ministry of planning. Govt. of the Peoples’ Republic of Bangladesh.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2015) . Statistical pocketbook Bangladesh 2015. Statistics and informatics division, ministry of planning. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Basak, N. C., & Pandit, J. C. (2011). Farmers’ attitude towards the use of USG in rice cultivation in three selected villages of Netrakona district. Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University, 9(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbau.v9i2.10983

- Chithra, Y. D., Meti, S. K., Bhawar, R. S., & Maraddi, G. N. (2018). Knowledge level of pigeonpea seed growers about improved seed production technologies-A critical analysis. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 7(9), 876–884. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.709.105

- Croasmun, J. T., & Ostrom, L. (2011). Using likert-type scales in the social sciences. Journal of Adult Education, 40(1), 19–22.

- Dey, B., Visser, B., Tin, H. Q., Laouali, A. M., Mahamadou, N. B. T., Nkhoma, C., Recinos, S. A., Opiyo, C., & Bragdon, S. (2022). Strengths and weaknesses of organized crop seed production by smallholder farmers: A five-country case study. Outlook on Agriculture, 51(3), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/00307270221115454

- Dhakal, S. (2013). Seed producer organization of farmer: An experience of western Terai, Nepal. Agronomy Journal of Nepal, 3, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.3126/ajn.v3i0.9018

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (1999). Sustainable seed system in SSA: Seed production and improvement. Seed Policy and Programs for sub-Saharan Africa. Plant Production and Protection Paper No. 151.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2014). Farmers’ organizations in Bangladesh: A mapping and capacity assessment.

- Global Data Lab. (2020). Average household size of Bangladesh. Institute for Management Research. Radboud University. https://globaldatalab.org/areadata/table/hhsize/BGD/?levels=1+4&years=2019

- Haque, A. H. M. M., Elazegui, F. A., Mia, M. T., Kamal, M. M., & Haque, M. M. (2012). Increase in rice yield through the use of quality seeds in Bangladesh. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(26), 3819–3827. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR12.541

- Hasan, M. M., Ahsan, T., & Kabir, M. M. (n.d.). Mini-packets of quality seeds: Improving poor farmers’ access to quality vegetable seeds.

- Hasan, K., Habib, A. M., Abdullah, D. B., & Afrad, S. I. (2016). Impact of alternate wetting and drying technique on rice production in the drought prone areas of Bangladesh. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 16(1), 39–48.

- Hossain, M. S. (2019, March14). In need of more quality seeds. NEWAGE. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.newagebd.net/article/67281/in-need-of-more-quality-seeds

- Hossain, S. (2020). Farmers in Bangladesh lack access to quality seeds. New age, the most popular outspoken English daily in Bangladesh. Retrieved November 2, 2022, from https://www.newagebd.net/article/119906/farmers-in-bangladesh-lack-access-to-quality-seeds

- Hossain, M. S., Islam, A. K. M. S., Kabir, M. J., Sarkar, M. A. R., Mamun, M. A. A., Rahman, M. C., & Kabir, M. S. (2021). Role of training in transferring rice production technologies to farm level. Bangladesh Rice Journal, 25(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.3329/brj.v25i1.55183

- Islam, M. N., Hossain, S. A., Baksh, M. E., Rahman, M. A., Sarker, M. A. B. S., & Khan, S. T. (2010). Studies on policy option for quality seed production and preservation of cereal crops at farmer’s level for the improvement of food security. Final Report PR, 6, 106–108. http://fpmu.gov.bd/agridrupal/sites/default/files/Najrul_islam-PR6-08.pdf

- Istaitih, Y., Alimari, A., & Jarrar, S. (2020). Determinants of farmers’ participation in informal seed production for wheat in Palestine. Research on Crops, 21(1), 168–176.

- Jaganathan, D., Bahal, R., Burman, R. R., & Lenin, V. (2016). Knowledge level of farmers on organic farming in Tamil Nadu. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 12(3), 70–73.

- Janani, S., Palaniswamy, A., & Balarubini, M. (2016). Relationship between knowledge level and characteristics of pulses seed growers. Journal of Extension Education, 27(1), 5401–5405. https://backup.extensioneducation.org/index.php/jee/article/view/36

- Joshi, G. R. (2015). Seed enterprise development in Nepal: Opportunities and challenges. Thematic paper presented at the Seed Summit, 2015, Seed Quality Control Centre.

- Juthi, S. R., Ahmed, M. B., Billah, M., Amin, R., & Adhikary, M. M. (2019). Extent of adoption of Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) recommended boro rice varieties. Acta Scientific Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.31080/ASAG.2019.03.0688

- Kamruzzaman, M., & Takeya, H. (2008). Capacity building of the vegetable and rice farmers in Bangladesh: JICA intervention. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 31(3), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v31n03_10

- Khan, S. (2021). Checking Bangladesh’s Fast-Shrinking Farmland. The Financial Express. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd

- Nahar, S., & Zulfiker, M. (2021). Socio-demographic characteristics and major problems faced by the farmers in adopting BRRI Dhan29 in the coastal areas of Bangladesh. International Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development Studies, 8(4), 36–52.

- Noor, K. B. M., & Dola, K. (2011). Investigating training impact on farmers’ perception and performance. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(6), 145–152.

- Omanga, P. A., & Rossiter, P. (2004). Improving emergency seed relief in Kenya: A comparative analysis of direct seed distribution and seed vouchers and fairs. In L. Sperling, C. Thomas, T. Osborn, & H. D. Cooper (Eds.), Towards effective and sustainable seed relief activities: Report of the workshop on effective and sustainable seed relief activities (pp. 43–53). Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Phala, M. (2019). Farmers’ perceptions of community-based seed production schemes in Polokwane and Lepelle-Nkumpi Local Municipalities, Limpopo [ Doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of Science and Agriculture, University Of Limpopo. http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10386/2887/phala_m_2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Prodhan, F., & Afrad, S. (2014). Barriers and preparedness of agricultural extension workers towards ICT utilization in Gazipur District Bangladesh. International Journal of Extension Education, 10(1), 1–9.

- Rahaman, M. S., Haque, S., Sarkar, M. A. R., Rahman, M. C., Reza, M. S., Islam, M. A., & Siddique, M. A. B. (2021). A cost efficiency analysis of boro rice production in Dinajpur district of Bangladesh. Fundamental and Applied Agriculture, 6(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.5455/faa.137178

- Rahaman, M. S., Kabir, M. J., Sarkar, M. A. R., Islam, M. A., Rahman, M. C., & Siddique, M. A. B. (2020). Factors affecting adoption of BRRI released Aus Rice varieties in Mymensingh District. Agricultural Economics, 5(5), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijae.20200505.18

- Rahman, S. M., & Al-Amin, S. (2016). Measuring the differences in cost of production: A study on boro rice farming in Bangladesh. Journal of Business Studies, 37(1), 217–237.

- Rahman, M. S., Khatun, M., Rahman, M. L., & Haque, S. R. (2018). Assessment of training needs on crop production for farmers in some selected areas of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research, 43(4), 669–690. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjar.v43i4.39165

- Rana, M. M., & Rahaman, H. (2021). Problem confrontation of vegetable growers in production and marketing of vegetables: Evidence from Northern Region of Bangladesh. Journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment (JAFE)| ISSN (Online Version): 2708-5694, 2(4), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.47440/JAFE.2021.2406

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

- Sakib, M. H., Afrad, M. S. I., & Prodhan, F. A. (2014). Respondent women farmers’ knowledge on aquaculture practices in Bogra district of Bangladesh. International Journal of Agricultural Extension, 2(2), 121–127.

- Shah, M. M., Grant, W. J., & Stocklmayer, S. (2016). Farmers’ innovativeness and hybrid rice diffusion in Bangladesh. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 108, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.04.015

- Sharifuddin, J., Mohammed, Z. A., & Terano, R. (2016). Rice farmers’ perception and attitude toward organic farming adoption. Jurnal Agro Ekonomi, 34(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.21082/jae.v34n1.2016.35-46

- Thompson, J. R. (1979). An introduction to seed technology. Leonard Hill. https://doi.org/10.2307/3898463

- Trading Economics. (2021). Bangladesh GDP per capita 2021. https://tradingeconomics.com/bangladesh/gdp-per-capita

- Twumasi, M. A., Jiang, Y., Danquah, F. O., Chandio, A. A., & Agbenyo, W. (2020). The role of savings mobilization on access to credit: A case study of smallholder farmers in Ghana. Agricultural Finance Review, 8(2), 275–290, , https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-05-2019-0055

- Wyss, R., López Noriega, I., Gauchan, D., & Guenat, D. (2018). Farmers’ access to quality and diverse seed in Nepal: Implications for seed sector development.

- Yasmin, S., Afrad, M. S. I., & Prodhan, F. A. (2014). Socio-economic impact of liming on vegetable production in acid soils of belabo upazilla under Norsingdi district. Ann Bangladesh Agric, 18(1), 87–95.

- Zappi, E. G. (1991). If eight hours seem too few: Mobilization of women workers in the Italian rice fields. Suny Press.