?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The war in Tigray (Northern Ethiopia) that started at the beginning of November 2020 has brought devastating damage to smallholder agriculture and food security. However, empirical evidence on the effect of war on smallholder agriculture has not studied systematically. Thus, this research was initiated to address the knowledge gap. A survey was done on selected 4376 households using systematic random sampling. All the data required for the study was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire, focus group discussions and key informant interview. The study revealed that 81% of the smallholder households lost their crop followed by livestock (75%) and farm tools (48%). Overall, 94% of the households reported that at least one of their agricultural components (crop, livestock and farm tools) was looted and/or destroyed by the belligerents. Of which, 37% of the respondent’s crop, livestock and farm tools were totally damaged. Moreover, farmers have limited access to their farms, agricultural inputs, and services. Consequently, more than 5.2 million people are currently in need of immediate humanitarian assistance. To avert the worsening situation, immediate intervention is needed to deliver food and agricultural input supplies and rehabilitate the agricultural extension system and infrastructure.

1. Introduction

During war time, agriculture can act as a safety net, “providing food and income in a context of insecurity, market closures and damage, and shortages of critical goods and services” (FAO, Citation2017a). However, agricultural production was directly or indirectly damaged by the war. According to Adelaja and George (Citation2019), agriculture directly affects through direct disruption on agricultural outputs, inputs, land, infrastructure and human capital, and indirectly, through disruptions in various aspects of the broader environment of agricultural operations. The main disruption of war on agriculture is physical damage, either through agriculture being systematically targeted as a weapon of war or as a consequence of the violence (Moore, Citation2017; RFSAN, Regional Food Security Analysis Network, Citation2016).

Previous studies have found that war adversely affects agricultural production, farm investments, cropping practices and the output of specific crops (Adelaja & George, Citation2019; Baumann & Kuemmerle, Citation2016, FAO, Citation2017a; George et al., Citation2020). The government troops and rebels have used famine as a weapon to terrorize and control populations (Devereux, Citation2007; Waal, Citation2006) as well as some civilians living in war zones have done the same even if in a much smaller scale when compared to armed groups (Igreja, Citation2019). Besides the immediate consequences of food shortage and starvation, the use of famine as a weapon leaves disastrous social and health impacts that are experienced long after the war conflict and famine has been terminated (Igreja et al., Citation2021). However, the impact of war on agriculture remains very poorly understood, both at local and national levels (George et al., Citation2020; Martin-Shields & Stojetz, Citation2019).

Prior to the war in Tigray, agriculture consisted of crop production and livestock farming was the backbone of the Tigray economy. More than 80% of the rural people in Tigray are primarily engaged in subsistence agriculture, and crop production which is one of the important production systems for food, feed and nutritional security (FAO Citation2021). The agricultural sector in Tigray has been showing an improvement because of significant progress in restoring of the degraded lands and improving its agricultural input use and water security. Growth in the agricultural sector remains highly important to maintaining overall growth of the region. According to Regional Gross Domestic Product (RGDP), the economy of Tigray registered an average growth rate of 8.1% during the last consecutive four years (2015 –2019) of GTP II implementation period (TSA, Tigray Statistical Agency, Citation2021). The agriculture sector in particular had registered an annual growth rate of 4.0%. Among the agriculture sector, crop production activity contributed its greatest share (65%) to the agricultural GDP, which was followed by livestock and forestry by 32% and 3%, respectively. Meanwhile, the contribution of agriculture was 37% to the total real GDP.

However, in 2020, these combined with a plague of desert locusts the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and national-level pressures including macro-economic difficulties affected the growth in agricultural production. Besides, at the beginning of November, 2020, The Ethiopian government declared armed conflict in Tigray, involving the Ethiopian national defense force (ENDF) and its allies—formal and informal military factions of the Amhara region, the Eritrean defense force (EDF) and Somali soldiers (Annys et al., Citation2021; World Peace Foundation, Citation2021). Several international and national reports confirmed that many farms, agricultural offices, farm institutions in rural areas were destroyed, crops burned down and looted, farm equipment and irrigational structures destroyed, and livestock were looted and/or slaughtered (BoARD, (Bureau of agriculture and rural development), Citation2021; Annys et al., Citation2021). Moreover, due to lack of feed, water and health service livestock production has been declined.

The agricultural system in Tigray has been devastated by months of fighting and extensive looting and destruction (World Peace Foundation, Citation2021). The costs of the decline in agricultural output can also have dramatic consequences in terms of food security. Consequently, more than 5.2 million people of Tigrayans have become in dire need of humanitarian aid (food as well as medical supplies and health care services) (USAID, Citation2021). Moreover, they also use siege to cut-off food supplies and productive capacities, starve opposing populations and hijack food aid intended for civilians. The war damage and loss to the agricultural sector had not only the immediate impacts but also lasted over extended periods of time.

Most of the evidence on the war damage on agricultural were based on cross-sectional data that was collected in the post-conflict era (George et al., Citation2020). However, this study was done during the war when the region is under the invaders and before the information was lost. Furthermore, the empirical evidence on the impacts of war damage on smallholder agriculture is scarce. Therefore, this study was done to assess the effect of war on smallholder agriculture in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area description

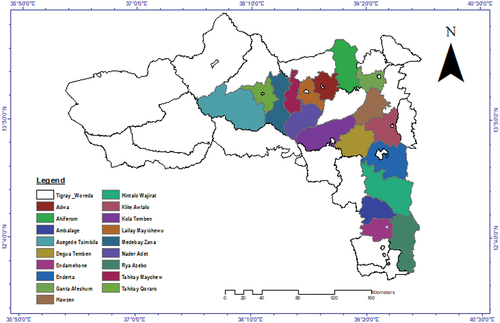

The study area, Tigray National Regional State, is located in the northern most part of Ethiopia. Geographically, it is located between 12° 14’50.50” to 14° 53’48.03” latitude and 36° 26’48.74” to 39° 59’ 0.09” longitude (Figure ).

According to the CSA 2016/17 projection, the population size was 5,247,005 with an estimated area of 54,593 square kilometres. The average annual temperature of the region is between 12°C and 37°C, and the annual rainfall between 500 and 1,000 mm (Abrha et al., Citation2018). Topography of the region from massif highland of 4090 m a.s.l in south Tigray to the north-western lowlands where the elevation is as low as 500 m a.s.l. Agriculture is the main stay of the economy in Tigray. Teff, wheat, corn, sorghum, barley Niger seed, flax seed and sesame are the main crops. Other agricultural products include pulses (beans, lentils), vegetables (onion, tomato and potato) and different fruits such as orange, mango and guava. The region is also known for its export items of cotton, incense, sesame and minerals. The study sites were rural districts such as Adwa, Ahferom, Alaje, Asgede Tsimbla, Degua Temben, Endamehoni, Enderta, Ganta Afeshum, Hawzen, Hintalo Wejirat, Kola Temben, Lealay Maychew, Medebay Zana, Naeder Adet, Raya Azebo, Tahtay Koraro, Tahtay Maychew and Kilte Awlaelo, which are located in five zones across central, eastern, south eastern, southern and north west zones of the region.

However, the study was limited to the most accessible woreda of each Zone. Areas occupied by the Amhara force and the Eritrean defense force, such as the whole Western Tigray, parts of Northwestern, Southern (i.e. Ofla and Raya Alamata), Eastern (i.e. Gule Mekada and Erob) and South Eastern (i.e. Seharti and Samre) Tigray, which are severely affected by the war, could not be incorporated into our sampling due to a worsening security situation.

2.2. Sampling technique and size

A multi-stage sample selection method was employed to select study sites and households. Eighteen Woredas from five zones were selected considering the level of damage, security and accessibility. Then, an average of three tabia’s were selected randomly from each Woreda. In this study, we used 4376 sample households selected using systematic random sampling from the selected tabias based on probability to proportional size. The total sample size were determined using the formula developed by Kothari (Citation2004).

where n = sample size, N = pop size, p = pop proportion, Z = confidence level, e = margin of error.

Thus, by taking confidence interval of 99% (z = 2.58), a margin/degree of error of 2%, the proportion (P) = 69%, the minimum sample size was 3535. We considered 25% of none response rate. The final sample was 4376 households.

2.3. Data collection

Primary and secondary data were collected for this study. The primary data were collected from households using semi-structured questionnaire, focus group discussions (FGD) and observation. The data were collected from 4 May to 4 June 2020. Data collectors were trained for five days to fully understand the data collection instruments. They were all BSc degree holders and above. The questionnaires were administered to household heads. However, in the absence of the head of household, a representative mostly the wife, eldest son, or the daughter was interviewed on his or her behalf.

34 FGD were also conducted with different social groups to collect qualitative data. Each group was composed of about six to eight individuals and the topics for the discussion were related to the type of damage that occurred, unique behavior of the damage and scope of the damage to agriculture and possible solutions taken. Each focus group had a trained facilitator who guided the participants through sets of prepared questions. Women’s groups, farmer groups, indigenous ethnic groups and elderly people who have knowledge of the local situation were the major participants of the FGD in each Kebelle. A total of 18 Key informant interview (KII) were also conducted with agricultural experts and development agents to collect further information.

Secondary data that include the number of tabias in each woreda, the total number of population in the woreda and tabias have been collected from woreda Agriculture and Rural Development Office.

2.4. Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as sum, means and percentages were used to analyze the quantitative data such as demographic, socioeconomic characteristics and quantities and/or values of damaged agricultural products and farm tools. Qualitative data collected through focus group discussion, key informants and observations were analyzed using content analysis. The summaries of the narrations were used in the discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

In this assessment, a total of 4376 small rural households were incorporated. Of which 28% of the respondents were female-headed households. The total average ages of the respondents were 47 ± 14 and the mean family size were 6 ± 2. The average total landholding sizes (Own, rental and share) of households were 1.06 ± 0.86 ha. About 38% of the households in the study area has an average farmland size of 0.5 ha. The majority (>93%) of the household livelihood strategy depends mainly on crop production (Appendix 1).

3.2. Effect of war on crop production

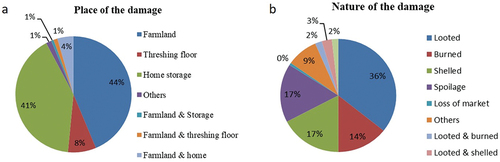

The study determined that more than 81% of the household crop has been deliberately devastated by months of fighting and wide looting, burning and destruction. The average total war damage on crop production from the study households was estimated at about 14.83 quintals. Of which, about 4% of the crop lost were from previous production years stored for the next planting season. Consequently, about 44% of the damage on crop was before harvesting while it was on the farm land, 41% from the home storage and 8% were from the threshing floor (Figure ). The highest disruption of crop was recorded during the month of November (53.4%) followed by March (14.6%). However, 63.3 % of the damage in Endamekoni Woreda was recorded in March.

The main war damage to crops consisted of looting, followed by spoiling (intentionally mix with unwanted materials such as urine, soap, sand etc.Figure ), shelling and burning (Figure ).

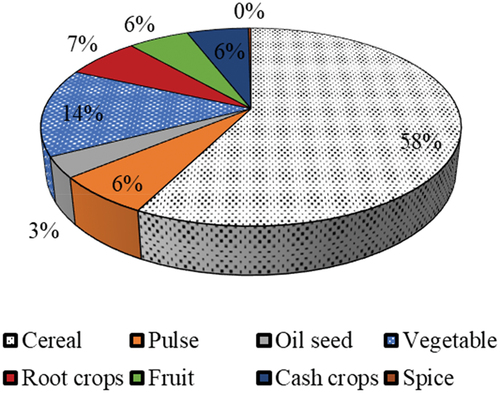

Among the diverse crops grown by smallholder farmers, higher cost of war damage (in quintal) was recorded on cereals followed by vegetables and root crops, respectively (Figure ). In addition to the damage to crop production, 26.5% of households straw/fodder was burnt, and 12.5% of the perennial fruits were cut down/uprooted and destroyed by the invading forces.

Perpetrators of the crop damage comprised of the Eritrean defence force (43%), Ethiopian national defence force (10%), 6% of the damage perpetrator unknown and 25% that can be attributed either to Ethiopian or Eritrean soldiers, as they jointly carried out the damage. The perpetrator for 16% of the crop damage is Amhara force, gangsters and others (Appendix 2). In woredas of Adwa, Laelay Maychew, Tahtay Maychew, Tahtay Koraro and Asgede Tsimbla, over 62% of the damage has been done by Eritrean soldiers only. However, more than 57% of the damage in Raya Azebo and Hintalo Wejerat has been done by Ethiopian national defence force only.

3.3. Effect of war on livestock production

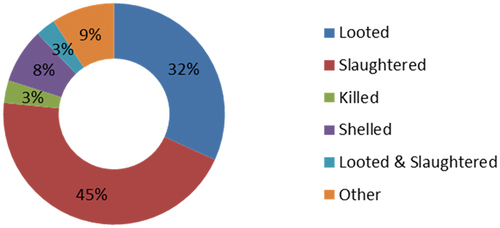

The war has caused major disruption on 75% of households connected to livestock rearing. Overall, in the study households, a total of 41,012 livestock were looted, slaughtered and killed by the belligerents (Figure ). Of the damage, 88% of livestock were killed/looted on the cowshed and 12% were out of the cowshed (on field or during travel).The higher population of war damage on livestock was recorded on poultry followed by goat, sheep and cattle, respectively (Table ). The total number of lost on cattle was higher in Asgede Tsimbla woreda (626) followed by Medebay Zana (483) and Tahtay Koraro (439), respectively. Whereas the large number of sheep were lost from Hawzen (709), followed by Ganta Afeshum (568) and Kilte Awlaelo (453) (Appendix 3).

Table 1. Total war damage on livestock production

Most of animals were mainly slaughtered, looted, killed, shelled and also as a result of lack of fodder and absence of clinic services (Figure ). According to the FGD, with farmers, livestock, veterinary clinics and animal feed were systematically destroyed to starve farmers.

The war perpetrators targeting livestock included Eritrean soldiers (54%), Ethiopian NDF (10%), while 5% of the damage produce were unknown. An additional 27% of the damage could be attributed either to Ethiopian national defence force or Eritrean soldiers, as they jointly carried out the damage. While 4% of the damage was done by Amhara forces, Amhara fano and gangsters (Appendix 4). Similarly to the damage on crop, the vast damage (51%) on livestock is recorded in November, followed by March (18%) and December (10%).

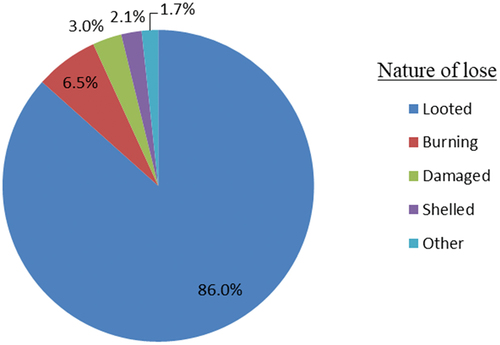

3.4. Effect of war on farm tools

In addition to war damage on crop and livestock production, more than 48% of the respondent farm tools were either looted or damaged. Various plowing tools, irrigation infrastructures and other farm equipment have been deliberately destroyed to hinder future agricultural production and starve farmers. Most of the farm tools (87%) were looted (Figure ). The higher costs of war damage on farm tools were recorded in Woreda Medebay Zana, Tahtay Koraro and Enderta, respectively. About 54 water pump generators and plastic pipes used for irrigation were vanished.

War perpetrators damaged more than 86% of farm tools involved EDF (57%), ENDF (10%) and an additional 19% that can be attributed either to ENDF or EDF, as they jointly carried out the damage (Appendix 5). Similar to the damage on crop and livestock production, the massive damage on farm tools (More than 90%) was recorded in November (54%) followed by March (16%), December (10%) and February (10%), respectively.

3.5. Effect of war on total smallholder agriculture

Although agriculture is the mainstay for the livelihoods of Tigray. However, the agricultural cost of war on smallholder farmers is undoubtedly immense. According to the focus group discussion (FGD) with local community, the Eritrean and Ethiopian NDF systematically looted, burned and disrupted the smallholder assets at least three times during door-to-door raids.

Overall, 94% of the respondents reported that at least one of their agricultural components (crop, livestock and farm tools) was looted and/or destroyed. Of which, 37% of the respondent’s crop, livestock and farm tools were totally damaged (Figure ).

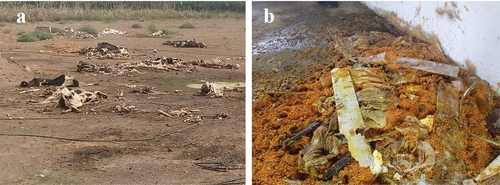

4. Discussion

Although starvation of civilians as a method of war is a war crime and was condemned by the Security Council in resolution 2417 of 24 May 2018 (Zappalá, Citation2019), the Ethiopian government and aligned force systematically destroyed agricultural production and farm tools to starve millions of smallholder Tigray farmers (Figure ). This is also directly against the second global goal of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development to end hunger.

Figure 7. Deliberately killed highbred cattle (a) and mixing crop with oil and fuels (b) in Woreda Raya Azebo.

The consequences of damage on crop have been acute for the rural populations as the conflict intensified during the harvesting season. Consequently, more than 5.2 million people are currently in need of immediate humanitarian assistance (USAID, Citation2021). Above 71% of smallholder farmers crop were systematically looted, burned and spoiled. Of the total disruption to crops, about 53% of the crop disruption was recorded in only one month (November) and similarly, during the Derg regime, 142,000 hectares of land in Tigray were destroyed by ground troops and aerial bombardment of Ethiopian government forces in only 2 months (Hendrie, Citation1994). The reason for higher disruption of crop recorded in November was because the belligerent systematically attacked during the harvesting time. Most of Tigray has only one rainy reason, the kiremt rains lasting approximately June–September. Similar studies under taken using geospatial information technology in agriculture also showed that several farm plots were damaged by the belligerents. For example, more than 50 farm plots burned in Maychew, Southern Tigray (World Peace Foundation, Citation2021).

The disruption of the 2020 harvest left many households waiting roughly 12 months until the first opportunity for another harvest. To extend the pain and as a form of long-term collective punishment, the smallholder farmers’ perennial crops have been deliberately cut down and destroyed by the belligerents. Similarly, the intentional damaging of perennial crop trees was also reported in Iraqi and Syria (FAO, Citation2016; Tull, Citation2017). Over 52% of the study, smallholder farmers have been intentionally restricted to plough their farms. Similarly, the satellite imagery indicates that the rainfed farmlands in Tigray were best ploughed in pre-war and least in 2021 (Biadgilgn et al., Citation2022; Nyssen et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). The ongoing war can lead to reduced mobility as people across agricultural value chains fear to move outside of protected areas because of attacks by combat actors (Wright & Weerakoon, Citation2012).

The livestock husbandry subsector has contributed a substantial portion to the economy of Tigray people before the war, contributing 12% of the regional GDP (TSA, Citation2021). Besides the economic and nutritional value, livestock provides power for the cultivation and crop threshing of the smallholder farmers and is also an essential mode of transport to take them and their families long distances, to convey their agricultural products to the market places and bring back their domestic necessities. Giving their critical role for smallholder farmers, about 76% of the livestock population including poultry was looted, slaughtered and killed by the belligerents. This study is also similar to the report of Tigray Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (Bureau, Citation2021). According to the KI and FGD farmers, besides to the direct slaughtering/killing of livestock by soldiers, farmers were being forced by Eritrean soldiers to slaughter their cattle, sheep and goat and prepare food for soldiers. Similarly, Eritrean soldiers collect and carry away poultry during door-to-door raids by slaughtering and packing as it is in the sack. The highest damage on livestock were recorded on the North-western Tigray because of Eritrean soldiers fully participated and stay for long time there. The study of war damage on the livestock of the Tigray can be differentiated between directly (91%) lost as looted, slaughtered/killed and indirectly (9%), due to lack of feeding, water, access to medicine (outbreaks of foot and mouth disease), the vaccines and other veterinarian services previously available from government are completely destroyed. According to the KII with the regional BoARD, more than 92% of the veterinary clinics have been looted or damaged. The percentage of damage to livestock within a few months was severe as compared to Six years’ damage on Syria. As compared before and after the war, our study reveals that the number of cattle were reduced by 74%, sheep and goats were reduced by 57%, 87% less poultry, 77% fewer beehive and 78% fewer equines. Whereas, in Syria, cattle were reduced by 305, sheep and goats 40%, and poultry 60% less (FAO & WFP, Citation2016). Likewise, In Iraqi, 50% of the population of cattle has been disrupted by ISIS (RFSAN, Citation2016).

For the past three millennia, Tigray’s agriculture has been based on traditional (ox ploughing) cultivation system of predominantly cereal crops. Before the war, the region was making substantial progress in agricultural transformation and improving its food and water security. The destruction and looting of farm tools and equipment have been significant across all the region. As the KII reported and confirmed by FGD, farm equipments from the traditional ploughing tools up to tractors have been deliberately burned, looted and destroyed to hinder the future agricultural production. Similarly, destruction of farm tools and equipment by ISIS as warfare is also reported in Iraq (FAO, Citation2016) and Syria (FAO Citation2017a). Studies on conflict also reported that agricultural infrastructure is purposefully looted or destroyed during the conflict, to disrupt the future irrigation systems, access to veterinary services, storage facilities, market, agroindustry, agricultural extension facilities and mechanized farming through lack of fuel or spare parts (FAO Citation2016c; IMU, Citation2017; Kimenyi et al., Citation2014).

Overall, the higher war damage was recorded on the crop followed by the livestock and farm tools. This is because of 93% of the studied households practiced annual and perennial crop production as the main stay for their livelihood. Similarly, the higher war damage to crop production was reported in Syria (FAO Citation2017a).

While Tigray has experienced several internal wars, the existing war is different in nature and magnitude of the damage happened on civilians, houses, crops, livestock, agricultural offices, farm institutions and farmers’ properties. In the present war, the belligerents purposely knock door-to-door to disrupt farmers agricultural production and assets. Although the nature and level of war damage happened on the Tigray were complicated as compared to other regions, the conflicts such as in Syria, Iraq and Yemen have been reported agriculture being used as a weapon of war (RFSAN, Citation2016). The disruption of the agriculture sector has not only affected the current production year, but it has also a long-term impact on the production and productivity of the smallholder agriculture, if immediate remedy action is not undertaken. War can also create the favourable conditions for outbreaks of pests and diseases, which can be important constraints to agricultural production (FAO Citation2016c; 2016b; 2017b).

5. Conclusion

Prior to the war in Tigray, agriculture-driven growth had the potential to enhance food security, increase self-sufficiency and benefit poor populations in both rural and urban areas. However, the overall vast damage due to the seven months of fighting and extensive looting and disruption confronted to the smallholding rural households of Tigray has been devastating. This study reveals that 94% of the respondents reported that at least one of their agricultural components (crop, livestock and farm tools) was looted and/or destroyed by the belligerents. Of which, 81% of the respondents stated that they lost their crops followed by 75% of livestock that were looted and slaughtered/killed, and 48% of the farm tools were destroyed, burned and/or looted. From the total number of livestock prior to the war, about 76% of the livestock population including poultry was looted, slaughtered and killed by the belligerents. The coalition of Ethiopian national defense force, Eritrean soldiers, Amhara special force and Fano was committed to the war damage to agriculture. The study reveals that agriculture is deliberately targeted as a weapon of war to starve the people of Tigray. The starvation happened due to the disruption of 2020 crop harvest, livestock, farm tools and labour is not only for this production period but it has also a long-term impact on the production and productivity, if immediate action is not taken even under current conditions. This is also against the United Nations Security Council resolution 2417 and the goal of Agenda 2030 for sustainable development to end hunger. Therefore, to avert the worsening situation, an immediate intervention is needed to deliver food and agricultural input supplies and rehabilitate the agricultural extension system and infrastructures.

List of abbreviations

EDF: Eritrean defence forceENDF: Ethiopian national defence forceGTP: Growth and transformation planRGDP: Growth and transformation plan

Author contribution

AM, planned the study, collected data, analysis and prepared the first manuscript. A.A, BM & NS participated on data collection, data entry and revised the draft manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support provided by Tigray Institute of Policy Studies (TIPS). The authors acknowledges Dr. Araya Mebrahtu and the two anonymous reviewers for insights and useful comments. We particularly thank the respondents who accepted and took risk to share their information during the war time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets and questioners used during and/or analyses the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ashenafi Manaye

Ashenafi Manaye is a Researcher in Agricultural Modernization in the Economy sector at the Tigray Institute of Policy Studies. His academic background is climate change and development, and he works on agricultural policy related to issues of Agroforestry, non-timber forest products, industrial plantation and climate change adaptation and mitigation. Previously, he has more than 10 years of work experience in Ethiopian agricultural research system. AD recruited at Ethiopian Agricultural Research Institute (EIAR), as Junior Researcher and Center Forestry Research Process Coordinator and at Ethiopian Environment and Forest Research Institute (EEFRI), Mekelle Environment and Forest Research Center as Assistant Researcher II and Center Climate Science Research Process Coordinator. He holds a B.Sc. degree in General Forestry and M.Sc. in Climate Change and Development from Hawassa University, Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural resource.

Aklilu Afewerk

Aklilu Afewerk is an Associate Researcher in agricultural modernization in the Economy sector at the Tigray Institute of Policy Studies. His academic background is agronomy, and he works on Agricultural modernization policy issues related to horticulture and agronomy. Previously, he has more than 10 years of lecturing experience in agricultural TVET. He holds a B.Sc. degree in horticulture and MSc in Agronomy from Mekelle University,

Belay Manjur

Belay Manjur is the principal assistant researcher in ecology in the technology sector at the Tigray Institute of Policy Studies. His academic background is Environmental Science and Ecological Engineering, and he works on ecology issues related to conducting policy research, giving policy brief for government, providing research-based recommended solutions and advices to the regional government. BM recruited at different Ethiopian Agricultural system as center director, national research case team coordinator and researcher. He holds a B.Sc. degree in Production Forestry, M.Sc. in agroforestry and PhD in Environmental Science and Ecological Engineering.

Negasi Solomon

Negasi Solomon is the principal Associate researcher in ecology, in the Technology sector at the Tigray Institute of Policy Studies. His academic background is Environmental Science, and he works on ecology issues related to conducting policy research, giving policy brief for government, providing research-based recommended solutions and advices to the regional government. NS has more than 10 years teaching and research experience at Mekelle University. He holds a B.Sc. degree in General Forestry, M.Sc. in agroforestry and PhD in Environmental Science.

References

- Abrha, H., Birhane, E., Hagos, H., & Manaye, A. (2018). Predicting suitable habitats of endangered Juniperus Procera tree under climate change in Northern Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 37(8), 842–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2018.1494000

- Adelaja, A., & George, J. (2019). Effects of conflict on agriculture: Evidence from the boko haram insurgency. World Development, 117(May), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WORLDDEV.2019.01.010

- Annys, S., VandenBempt, T., Negash, E., & De Sloover, L. (2021). Tigray: Atlas of the humanitarian situation. Journal of Maps Preprint, (June), 1–72. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349824181_Tigray_Atlas_of_the_humanitarian_situation

- Baumann, M., & Kuemmerle, T. (2016). The impacts of warfare and armed conflict on land systems. Journal of Land Use Science, 11(6), 672–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2016.1241317

- Biadgilgn, D., Nyssen, J., Annys, S., Negash, E., Abay, T., Gebrehiwet, F., & Eleonore, W. (2022). Geospatial solutions for evaluating the impact of the Tigray conflict on farming. Acta Geophysica, 70(3), 1285–1299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-022-00779-7

- BoARD, (Bureau of agriculture and rural development). (2021). Agricultural emergency plan. Mekelle.

- Devereux. (2007). Introduction: From ‘old famines’ to ‘new famines. In Devereux, S. (Ed.), The new famines: Why famines persist in an era of globalization (pp. 1–26). Routledge.

- FAO. (2016). Iraq: Agriculture and livelihoods needs assessment in the newly liberated areas of kirkuk, ninewa and Salahadin, february, 2016. - Iraq | ReliefWeb. Iraq: Agriculture and Livelihoods Needs Assessment in the Newly Liberated Areas of Kirkuk, Ninewa and Salahadin, February, 2016. - Iraq | ReliefWeb. 2016. https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-agriculture-and-livelihoods-needs-assessment-newly-liberated-areas-kirkuk-ninewa

- FAO, 2017a Counting the cost: Agriculture in Syria after six years of crisis (FAO)http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/rne/docs/plan_of_ action_syria_2016_2017.pdf

- FAO & WFP. (2016). Special report FAO/WFP crop and food security assessment mission to the syrian arab republic. https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/special-report-faowfp-crop-and-food-security-assessment-mission-syrian-0.

- George, J., Adelaja, A., & Awokuse, T. O. (2020). The agricultural impacts of armed conflicts: The case of Fulani Militia. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbaa022

- Hendrie, B. (1994). Relief aid behind the lines: The cross-border operation in Tigray. In M. Macrae, J. Zwi, & A. Duffield, and M. Slim (Eds.), War and hunger. Rethinking international responses to complex emergencies, (Vol. 125, p. 139). Zed Books .

- Igreja, V. (2019). Negotiating relationships in transition: War, famine, and embodied accountability in mozambique. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 61(4), 774–804. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417519000264

- Igreja, V., Colaizzi, J., & Brekelmans, A. (2021). Legacies of civil wars: A 14-year study of social conflicts and well-being outcomes in farming economies. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(2), 426–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12802

- IMU. (2017). Syria dynamic monitoring report DYNAMO issue 6, february 2017 - syrian arab republic | ReliefWeb.|Syria dynamic monitoring report DYNAMO issue 6, february 2017 - syrian arab republic | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syria-dynamic-monitoring-report-dynamo-issue-6-february-2017

- Kimenyi, M., Adibe, J., Djiré, M., Jirgi, A. J., & Kergna, A. (2014). The impact of conflict and political instability on agricultural investments in Mali and Nigeria. Brookings Institution. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/the-impact-of-conflict-and-political-instability-on-agricultural-investments-in-mali-and-nigeria/

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. In K., Chakravanti Rajagopalachari (Ed.), New age international publisher, (2nd ed) (p. 418). New Age International Publisher.

- Martin-Shields, C. P., & Stojetz, W. (2019). Food security and conflict: Empirical challenges and future opportunities for research and policy making on food security and conflic. World Development, 119, 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.011

- Moore, A. (2017). Agricultural extension in post-conflict liberia: Progress made and lessons learned. In P. E. McNamara & A. Moore (Eds.), Building agricultural extension capacity in post-conflict settings (pp. 1–22). CAB International.

- Nyssen, J., Negash, E., Van Schaeybroeck, B., & Annys, S. (2021). Ploughing in the Tigray war. 1–32.

- Nyssen, J., Negash, E., Van Schaeybroeck, B., Haegeman, K., & Annys, S. (2022). Crop cultivation at wartime–plight and resilience of Tigray’s Agrarian Society (North Ethiopia). Defence and Peace Economics, 34(5), 618–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2022.2066420

- RFSAN, (Regional Food Security Analysis Network). (2016). The impact of ISIS on Iraq’s agricultural sector - Iraq | ReliefWeb. The Impact of ISIS on Iraq’s Agricultural Sector - Iraq | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/impact-isis-iraq-s-agricultural-sector.

- TSA, (Tigray Statistical Agency). (2021). Annual macroeconomic report of Tigrai Regional state- Regional gross domestic product (2008EFY-2011EFY). Mekelle.

- Tull, K. (2017, June). Agriculture in syria. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13081.

- USAID. (2021). Northern Ethiopia crisis. Fact Sheet # 1. October 29, 2021.

- Waal, D. (2006). Famine crimes: Politics and disaster relief industry in Africa. James Currey.

- World Peace Foundation. (2021). Starving Tigray how armed conflict and mass atrocities have destroyed an Ethiopian region’s economy and food System and are threatening famine. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Starving-Tigray-report-final.pdf.

- Wright, J., & Weerakoon, L. (2012). Taking an agroecological approach to recovery: Is it worth it and is it possible? In R. Roberts & A. Özerdem (Eds.), Challenging post-conflict environments (pp. 103–116). Taylor and Francis.

- Zappalá, S. (2019). Conflict related hunger, ‘starvation crimes’ and UN security Council resolution 2417 (2018). Journal of International Criminal Justice, 17(4), 881–906. https://doi.org/10.1093/JICJ/MQZ047