Abstract

This paper systematically sheds light on the procurement systems, the selection criteria of Supermarket agrifood suppliers, and the impact of procurement systems on producers. A systematic search of literature from 2000 to 2022 was carried out. Fifty-two peer-reviewed research articles were identified from the Scopus database. The review findings revealed a positive impact on the income, productivity, and efficiency of the suppliers of supermarkets. Supermarkets used a combination of procurement systems (modernised and traditional) but primarily used the modernised method. Most studies reported that pricing and quality of food, the safety of produce, quantity, supply stability, delivery timeliness, and trust connections determine whether supermarkets buy from small or large producers. From the study, it is suggested that, to attract and maintain consumers in the underdeveloped areas, supermarket managers have to practice a just-in-time inventory management system where stocks will be kept low and also integrate vendor relationship management to reduce the cost of fresh fruits and vegetables sold at the Supermarket.

1. Introduction

As part of the globalisation process, multinational supermarket chains have risen in popularity in emerging countries in recent decades (Reardon et al., Citation2003). Recently, across Asia and Africa, various households purchase from supermarkets at different rates (Bannor et al., Citation2022; Reardon et al., Citation2003). Small format retail’s early arrival into smaller towns and rural towns, as well as meagre and lower-middle-class food markets and fresh food marketplaces, is credited to the boom (Reardon & Minten, Citation2011). The current market share of supermarkets in China is expected to be over 30% in metropolitan regions, with a growth rate of around 30% per year (Lu et al., Citation2008). By the mid-1990s, one-third of Bangkok’s populace purchased from supermarkets stores regularly (Feeny et al., Citation1996). Vietnam has seen an upsurge in the number of supermarkets during the last decade. Before 1993, Vietnam did not have this modern format (Maruyama & Trung, Citation2006). The surge was triggered by several factors, of which many are interlinked: increased earnings, urbanisation, more women in the workforce, and increased openness to international investment, to name a few (Traill, Citation2006).

Relative to urbanisation, the World Urbanisation Prospects (United Nations, Citation2003) projected that from 2000 to 2030, population growth would be around 2.3 percent per year, with Africa undergoing fast development (United Nations, Citation2003). Changes in eating habits and tastes for high-quality, convenient foods are emerging due to urbanisation (Louw et al., Citation2008).

The rise of supermarkets in developing nations through foreign direct investment (FDI) has also led to the revolution in the agrifood sector, specifically supermarkets’ food retailing (Louw et al., Citation2008), leading to a competition between supermarkets and the traditional markets (D’Haese & Van Huylenbroeck, Citation2005). Thus, supermarkets are surging in most developing nations within specific cities since the domestic retail market was opened to foreign direct investment (Hu et al., Citation2004; Reardon et al., Citation2007). In Taiwan, for example, traditional marketplaces’ market share has been declining at a pace of 3 to 5% annually (Trappey & Kuan Lai, Citation1996). By 2000, the contemporary retail sector had handled more than 60% of all food sales (Cadilhon et al., Citation2003). This evolution has shifted away from traditional marketplaces toward purchasing at supermarkets (Maruyama & Trung, Citation2006).

From recent data, the developing world sees a significant development in supermarkets (Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003). Since the mid-2000s, the number of local supermarkets owned and managed in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has steadily increased (Barrientos et al., Citation2016), and South African supermarkets are leading the way to expansion in Africa (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009). The largest supermarket chains in South Africa have penetrated other markets in the countries by acquiring other supermarkets, franchising, and creating collaborations with other supermarkets firms in host nations (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009). Trade liberalisation, more significant economic growth, beneficial political changes, regional integration, increasing urbanisation, increased per capita income, an enlargement of the middle class, and the liberalisation of foreign direct investment have all aided growth and expansion (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009).

Traditional food vending arrangements such as informal vending and wet marketsFootnote1 are being displaced by this modern supermarket construction (Goldman et al., Citation2002; Reardon & Timmer, Citation2014). For instance, supermarkets in South Africa account for a growing proportion of fresh fruits and vegetables (FFV) retail in South Africa, increasing from 30–40% in 2000 to 50% in 2012, while in Kenya is about 5% of total FFV sales (Barrientos et al., Citation2016). Thus, despite an increasing trend in purchasing agriproductsFootnote2 from supermarkets in Africa, small retailers and wet markets continue to dominate (Das Nair, Citation2018). Fresh produce, for example, accounts for barely 10–15% of store food sales in other emerging countries (Reardon & Gulati, Citation2008). A crucial reason is that consumers in many countries are hesitant to buy FFV outside of wet markets, causing a greater portion of processed food being sold than fresh food in the supermarkets, even though consumers perceive that quality requirements are not compromised in the supermarket (Bannor et al., Citation2022). For example, Nakumatt, a Kenyan supermarket, mandates its primary suppliers to follow KenyaGAP (the local version of GlobalGAP) (Barrientos et al., Citation2016). On the supplier side, the ongoing transformation of retail sectors could either contribute to poverty reduction or have a significant impact on producers’ livelihoods (Shankar et al., Citation2011; Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003).

The importance of supermarkets in developing economies has resulted in an increasing number of studies on supermarket growth in emerging economies (Bannor et al., Citation2022; Boselie et al., Citation2003; Reardon et al., Citation2003; Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003). Yet, the existing studies concentrated on the procurement systems of supermarkets in developed countries (Reardon et al., Citation2003; D’Haese & Van Huylenbroeck, Citation2005; Neven & Reardon, Citation2004; Reardon, Citation2006; Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003). Others on supermarkets and fresh vegetable and fruit growers in China (Goldman, Citation2000) and (Hu et al., Citation2004), India (Reardon & Gulati, Citation2008), Kenya (Neven & Reardon, Citation2004), South Africa (Winter, Citation2007), Namibia (Nickanor et al., Citation2020), and (Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003) Africa. Studies have also been conducted on consumers’ choice of supermarkets for agricultural products (Bannor et al., Citation2022; Dadzie & Nandonde, Citation2018; Gorton et al., Citation2011; Meng et al., Citation2014; Okello et al., Citation2012).

Notwithstanding these studies, there is yet to be a systematically study on the supply of agriproducts to supermarkets. Therefore, the current review seeks to describe the evolution of supermarkets in Africa and Asia, the selection criteria for suppliers of supermarkets, and the effect of the supermarket supply chain on agriproducts suppliers across Asia and Africa. A better understanding of how supermarkets source their agriproducts from suppliers, their supplier’s selection criteria, and the impact of their procurement systems on the agriproduct suppliers will help the producers, especially the rural and urban producers, to benefit from the rapid rise of supermarket (Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003). Given these, the authors systematically discuss the existing and current knowledge to understand the supply of agriproducts to supermarkets in Asia and Africa, identify the gaps, and propose avenues for future studies to fill these gaps.

2. Methodology

This study followed the Oppong et al. (Citation2022) strategy and structure of a systematic review. The process involved: 1. defining the review question, 2. defining the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3. systematic literature search, 4. selecting the studies based on the previous research, 5. assessment of the quality of the included studies, 6. extraction of data from the included studies 7. summarising the evidence, and 8. discussing the review findings and drawing a conclusion.

2.1. Article search and identification strategy

The strategy used for the systematic literature search included: 1. Identifying the themes within the review question 2. Finding keywords for each theme 3. Connecting keywords using the appropriate Boolean operators.

The electronic database used to retrieve the relevant article based on the keywords in Scopus database.

To retrieve articles, scoping search was done using the term “supermarket” which was combined with the terms “Asia” and “Africa”. Asia and Africa were selected as the continent for the study due to the rapid rise of supermarkets in these regions as supermarket has altered the agriproduct markets. Given that several studies have been carried out on supermarket, a large number of studies was retrieved using the electronic database. Therefore, to retrieve relevant studies about the supply of agriproducts to supermarket and the quality standards requirements for the supply of agriproducts, the term “supermarket” which was then combined with various procurement system terms were as follows: “food suppliers”, “producers”, “farmers”, “growers” and with various quality assurance terms such as “food quality”, “food safety”, “food rejection”.

Articles had to be published in English in credible peer-reviewed journals between 2000 and 2022, and the entire text had to be available. Grey literature was excluded from the search. These included governmental papers, reports, research produced by an organisation outside academic publishing, working papers, student dissertations, conference proceedings, editorial notes, book chapters, and reviews.

2.2. Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment

At the preliminary stage of the literature search, appropriate filters were applied to remove irrelevant articles. The study’s selection was done based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria set. Articles were removed if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Duplicates were removed using Zotero. The articles’ titles and abstract were screened, and irrelevant studies were eliminated, which did not meet the inclusion criteria. After that, the studies were subjected to full-text screening to narrow down the list of literature. Cumulatively, 231 articles were identified through electronic databases. 52 articles (refer to Figure ) were coded for inclusion, and 118 articles were excluded. A well-designed spreadsheet was used to retrieve data across the following variables: authors, study title, publisher, year of published articles, major findings, abstract, and country covered. This was done to ensure that the criteria for inclusion were met.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Article distribution

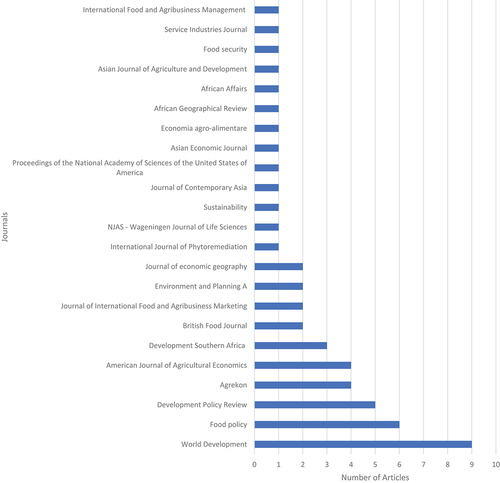

The articles selected for the review emanated from several journals (see Figure ). They are the World Development (9 articles), Food Policy (6 articles), Development Policy Review (5 articles), Agrekon (4 articles), America Journal of Agricultural Economics (4 articles), and Development Southern Africa (3 articles).

3.2. Article distribution in subject areas

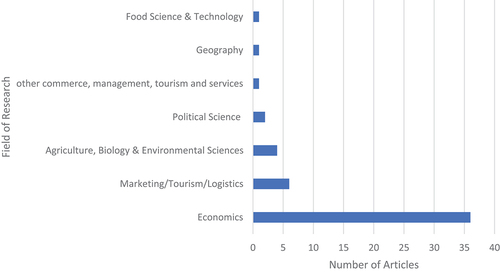

Thirty-six of the researched articles emanated from the economics field, forming the majority of the articles selected for the review. Followed by Marketing/Tourism/Logistics), followed by Agriculture, Biology, and Environmental science (4 articles) (see Figure ). The remaining articles emanated from the field of other commerce/management/Tourism and services, political science, Geography, and Food Science & Technology.

3.3. Volume of articles between 2000 and 2022

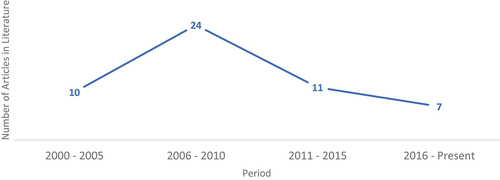

The analysis of the volume of articles used for the review revealed that scholars’ research on issues related to supermarkets between the period 2000 to 2010 increased from ten articles to 24 articles. This points to the rise and spread of supermarkets in emerging economies during the early 2000 (see, Figure ). Scholars conducted research on supermarket evolution issues as a result of the emergence and spread of supermarkets in developing economies. However, supermarkets are now well established in these economies, which has resulted in a decline in research because the primary focus was on supermarket evolution. Therefore, researchers can take up supermarket issues as the analysis has shown a nosedive between the year 2011 and till present.

3.3.1. Themes describing the supply of produce to supermarket

Four themes emerged from the authors’ detailed review as the full text of the 52 journal articles was studied. The subtotal of the number of articles indicated in Tables and 1a (refer to appendix) exceeds 52 as some articles discussed more than one theme. The supply of produce was discussed under these main themes: the evolution of supermarket and sale of agriproducts in supermarket, procurement strategies, the determinants of supermarket as an outlet for producers and consumers, the impact of supermarket on producers.

Table 1. Summary of variables explaining the impact of supermarket

3.4. The evolution of supermarkets in developing countries

A “supermarket revolution” began in emerging economies in the early 1990s and has sustained since then. The fast spread of modern retail shares in food retailing at the expense of traditional shops and wet markets is part of this shift (Reardon et al., Citation2010). In this review, four phases of the supermarket revolution are highlighted. The first phase of the supermarket spread affected major cities in Latin America’s larger and wealthier countries.

The second wave affected East/Southeast Asia and Central Europe; the third hit small or underdeveloped Latin American and Asian countries (including Central America) and southern, then eastern Africa. Secondary cities and towns in the “first wave” zones were being hit by this time. Southern Asia and Western Africa were affected by the fourth wave (Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006; Reardon et al., Citation2004). D’Haese and Van Huylenbroeck (Citation2005) reported that in many developing regions, supermarkets are growing faster, and hence local shops are incapable of competing with supermarkets. The review indicated that supermarkets had spread five times quicker in today’s developing economies. For example, Latin America accomplished what the United States took five decades to achieve in a decade, while retail growth in China was three times as quick in 2003 as it was a decade earlier in Brazil and Argentina (Reardon et al., Citation2003). Comparably, whiles Brazil accomplished the spread in two decades, United State achieved it in eight (Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006), meaning, supermarket penetration varies from country to country (Reardon et al., Citation2003). Supermarkets have spread to the developing countries; South Africa (Dannenberg, Citation2013), China (Zhang & Pan, Citation2013), Vietnam (Mergenthaler et al., Citation2009), Kenya (Neven & Reardon, Citation2004), Africa (Nandonde et al., Citation2018) and Asia (Reardon et al., Citation2007). This trend is characterised by the demand for supermarket services by the buyer and the supply of supermarket services (Reardon et al., Citation2004).

Following market liberalisation, the flow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the retail industry is a crucial supply-side driver (Chowdhury et al., Citation2005; Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006; Reardon et al., Citation2004). Reardon et al. (Citation2003) and Reardon and Berdegué (Citation2002) reported that the spread of supermarkets in Latin and East/South-East Asia was due to FDI. Thus, supermarkets are growing into poor regions of large cities and towns all over the developing countries, including Africa due to the aggressive marketing of supermarket formats as part of international retail expansion (Reardon et al., Citation2003). Apart from Africa, supermarkets also play a significant role in the food retail sector in other emerging economies (Ghezán et al., Citation2002; Gorton et al., Citation2011; Stringer et al., Citation2009). For example, China currently has the world’s fastest expanding supermarket industry. Supermarkets accounted for 48% of Chinese urban food markets in 2001, compared to 30% in 1999 (Reardon & Timmer, Citation2007). In the last four years of the 1990s, 61000 small dairy producers in Brazil were unable to respond quickly enough, and they all went out of business (Reardon & Timmer, Citation2007).

Obviously, supermarkets have successfully penetrated the mass market in numerous countries, including the middle class, lower-middle class, the poor and major cities to rural towns (Codron et al., Citation2004; Das Nair, Citation2018; Neven et al., Citation2008; Reardon et al., Citation2003; Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003) however, the penetration has not reached certain underdeveloped areas (Alita et al., Citation2020). Thus, despite the fast rise of supermarkets via FDIs, traditional food retail establishments continue to dominate in urban poor neighbourhoods. In essence, supermarkets are only used by a limited percentage of households (Wanyama et al., Citation2019). Peyton et al. (Citation2015) revealed in a South African study that there is an uneven spread of supermarkets. The authors asserted that the areas with high-income earners have a higher number of supermarkets whiles areas with low income have a lower number of supermarkets. For example, a Kenyan study reported that most supermarkets are in Nairobi, the capital city of Kenya. A similar situation happened in Latin America 5–7 years ago (Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003) and likewise in Ghana (Bannor et al., Citation2022).

Throughout the supermarket evolution, one theory that has been clear is the Wheel of Retailing Theory which states that, the evolution of retailing begins with the advent of retailers who aim to serve low-income customers, and as they mature, they begin to increase their profit margin which will lead to increase in prices (McNair, Citation1958; Hollander (Citation1960). For example, study in India revealed that products sold in supermarket are the same or lower than the prices of products sold in traditional retail (Minten & Reardon, Citation2009). Minten et al. (Citation2008) agree that supermarkets sell their product at a cheaper price than the traditional market. Contrary to the theory’s assumption, “price has been a key determinant in the emergence of modern retail outlets in most emerging markets” (Nandonde et al., Citation2018). An empirical research indicates that pricing in modern retail outlets is typically greater compared to traditional markets for comparable products (Nandonde et al., Citation2018). Minten et al. (Citation2008) concluded that the procurement system adopted by supermarket helped to sell its products at a cheaper price by taking advantage of economies of scale.

The evolution of supermarket did not happen concurrently. The spread happened first in the developed countries and later in the developing country. Yet, the spread in the developing economies happened at a faster rate in comparison to the developed country. Despite the spread in both developed economies and developing economies, the spread is uneven in these countries as supermarket are mostly situated in the urban areas.

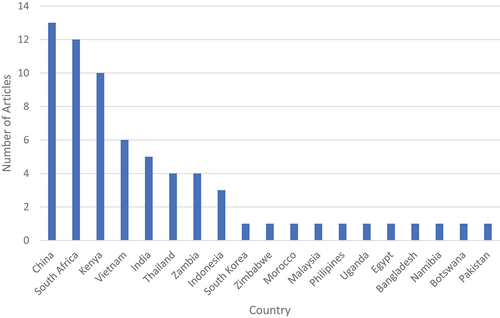

The analysis of the research articles indicated that the chosen papers for the review spread across 19 countries. Thirteen of the papers reviewed were from China, twelve from South Africa, ten from Kenya, six from Vietnam, five from India, four from Zambia, and four from Thailand.

South Africa and Kenya produced the majority of the reviewed papers from Africa. This can be likened to South Africa being the first African country to have seen the rise of the supermarket, preceded by Kenya. China, Vietnam, and Thailand contributed the majority of the reviewed papers from Asia (see, Figure ). This is consistent with the fact that Asia’s supermarket evolution began in the south.

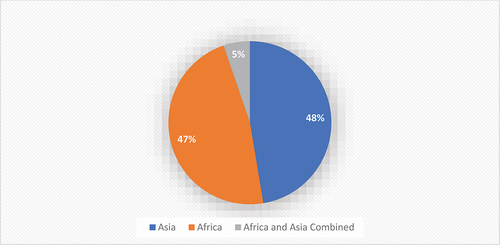

The analysis revealed that 48 percent of the papers selected was from Asia, 47 percent from Africa and 5 percent from both Asia and Africa (see, Figure ). On the global level, scholars investigating supermarket evolution in developing countries received nearly equal concentration.

This can be attributed to Africa having the world’s youngest and fastest increasing population, making the intellectual investment necessary to address rising issues and Asia having a significant impact on the global environment, both economically and politically.

3.5. Emergence of the sales of agriproducts in supermarkets

Supermarkets at the incipient stage penetrated first processed food and non-food products, then semi-processed products such as dairy products, and finally fresh meats, fish, and produce food (Neven et al., Citation2008, Citation2009; Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006; Reardon et al., Citation2003).

Processed food penetrated supermarkets at the earliest, with a far slower and yet recent penetration of fresh fruits and vegetables in Kenya (Neven et al., Citation2008), the USA and Western Europe (Reardon & Hopkins, Citation2006). In comparison to perishables in general, supermarkets were the first to enter the market for processed foods because they are easier to purchase and manage inventories and merchandise. Furthermore, competition from local stores and wet markets is more difficult, as people prefer to purchase FFV regularly (Neven et al., Citation2008). Goldman et al. (Citation2002) revealed that the low retail penetration of fresh food is widespread in many nations. Although a significant proportion of customers shop in supermarkets regularly, consumers do so preferentially, primarily for packaged and processed foods, and they continue to purchase fresh food from traditional retailers (Goldman, Citation2000). Likewise, in Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, and Nicaragua, consumers primarily buy their fresh vegetables from local vendors or the local markets (Wanyama et al., Citation2019).

Despite traditional retail outlets accounting for most fresh fruits and vegetable sales (Gorton et al., Citation2011), reported that their market share has shrunk significantly. Supermarkets only recently initiated fresh fruits and vegetables for numerous reasons. The penetration of agriproducts was triggered by a willingness to purchase the agriproducts at a premium price, knowledge and perceived benefits of products, consumers’ ethnocentrism, availability of the product, packaging, and product characteristics (Bannor & Abele, Citation2021). Recently, there has been an increase in the sale of fresh fruits and vegetables in supermarket.

3.6. Determinants of producers and consumers market channel choice

Supermarkets have become the new face of retailing in developing countries amongst urban consumers. Nonetheless, few studies have made an effort to investigate why consumers buy agricultural products from this modern market outlet (Bannor et al., Citation2022; Gorton et al., Citation2011; Meng et al., Citation2014; Okello et al., Citation2012). A recent study conducted in Ghana focused on consumer’s food shopping outlet choices (Bannor et al., Citation2022). Several authors revealed that consumer characteristics such as age, income, sex, educational level and household size are significant determinants of using supermarkets as a market outlet (Bannor et al., Citation2022; Dadzie & Nandonde, Citation2018; Iton, Citation2017; Maruyama & Trung, Citation2006; Meng et al., Citation2014; Okello et al., Citation2012). Other elements that determine the consumers’ retail outlet are the quality of fresh agricultural products, continuous availability of agricultural produce, diverse fresh and processed agricultural products, social recognition and prestige (Bannor et al., Citation2022). Consumers’ market choices are also influenced by location factors. The distance to the market, the convenience of shopping there, the scenery, and whether or not the market sells a variety of other items are all factors that may influence market selection (Meng et al., Citation2014; Okello et al., Citation2012). The location of the supermarket has an impact on where customers shop. Consumers who buy fresh agricultural products from supermarkets live closer to them (Bannor et al., Citation2022). One other element that influences where consumers shop is accepting alternative means of payment such as master cards, mobile money and other payment methods (Bannor et al., Citation2022). Aside from the variables mentioned earlier, Dadzie and Nandonde (Citation2018) revealed that consumers who visit supermarket look for sales promotions and discounts and excellent customer service.

According to Reardon et al. (Citation2009), several factors influence producers to participate in the supermarket channel. Researchers, in their pursuit, to find out the elements which influence the participation of producers, discovered that off-farm employment, ownership of a means of transportation (Rao & Qaim, Citation2011), irrigation system (Hernández et al., Citation2007; Reardon et al., Citation2009), and access to paved roads (Reardon et al., Citation2009) influences producers market outlet. Producers who are involved in off-farm jobs are more likely to participate in supermarket channels. This could be due to certain capital investments essential for participation, which are facilitated through off-farm earnings, especially when there are credit constraints (Rao & Qaim, Citation2011). Ownership of a means of transportation and availability of public transportation in the village are essential for producers participation as producers have to deliver their produce themselves to the supermarket locations (Rao & Qaim, Citation2011). Farms closer to the village head’s location are more likely to participate, with possible reasons being transaction costs of monitoring, collection, and social net- works (Rao & Qaim, Citation2011; Reardon et al., Citation2009).

Also, Rao and Qaim (Citation2011) discovered that large-scale producers are more likely to partake in supermarket channels, as did Neven et al. (Citation2009), whereas Hernández et al. (Citation2007), did not find farm size significant. Supermarket-channel producers prefer supermarket channel because it offers a lower risk due to contract and lower transaction cost, provision of technical assistance and training (Hernández et al., Citation2007; Reardon et al., Citation2009) transparent price policy, higher price and secured payment (Cadilhon et al., Citation2006; Reardon et al., Citation2009). Nonetheless, some producers are not able to participate (apparently because of higher transaction costs of collection) (Reardon et al., Citation2009).

3.7. Supermarket procurement system

Researchers discussed this theme in terms of how supermarkets source their agriproducts, supplier selection criteria and how the products get to the shelves of supermarkets. Scholars highlighted the change in the procurement system from the traditional method of procuring agriproducts to the modernised way of procuring agriproducts in the supermarket (Louw et al., Citation2006).

This review found several articles that identified the shift from a traditional procurement strategy to a modernised procurement strategy (Alita et al., Citation2020; Alvarado & Charmel, Citation2002; Berdegué et al., Citation2005; Lin & Wu, Citation2011; Neven & Reardon, Citation2004; Reardon & Swinnen, Citation2004; Reardon et al., Citation2003). Researchers pointed out that the modification in procurement strategy were (i) from per store purchase to centralisation through distribution centres, (ii) shift from traditional brokers to specialised/dedicated wholesalers, (iii) development of private standards for quality and safety, and (iv) the shift from sourcing in spot markets to use of preferred supplier programmes (Berdegué et al., Citation2005; Neven & Reardon, Citation2004; Reardon & Swinnen, Citation2004). The modification of the procurement system of supermarket to the current procurement system did not happen concomitantly (Humphrey, Citation2007). At the incipient stage, developing countries use of specialised/dedicated wholesalers and preferred suppliers (Balsevich et al., Citation2003). There was almost complete absence of central distribution and quality standards in developing countries (Codron et al. (Citation2004). For instance, in Central America, Berdegué et al. (Citation2005) reported the non-existence of implementing quality and safety standards by supermarkets when sourcing agriproducts.

Initially, supermarkets in the United Kingdom source their agriproducts through the wholesale market but however, shifted to the use of the modernised strategy. Similarly, supermarkets in developing countries firstly source their agriproducts from wholesale markets and, in recent years, shifted to a modernised procurement strategy (Humphrey, Citation2007). The trend in the shift of the modification of the procurement strategy is to avoid less inventory of the agriproducts and prevent procuring whatever they find at the market when it is needed. Supermarkets purchase their agriproducts from selected preferred suppliers as the traditional wholesalers have low-quality standards and, more importantly, inconsistent in standards. The use of the centralized distribution system enables supermarkets to save transportation cost, transaction costs, save time in ordering and organising products, and enjoy economies of scale (Balsevich et al., Citation2003; Berdegué et al., Citation2005; Humphrey, Citation2007).

Codron et al. (Citation2004) and Goldman (Citation2000) observed that supermarket procurement strategies differ from country to country. For example, a survey in Costa Rica reported that the supermarket chain shifted from solely sourcing their agriproducts from the wholesale market to sourcing their products primarily from preferred suppliers and a limited number of their produce from the wholesale market and selected importers (Balsevich et al., Citation2003). Similarly, a study in Morocco, the use of Centralised distribution system is reported (Codron et al., Citation2004). In South Africa, Louw et al. (Citation2008) reported that supermarkets purchase agriproducts primarily from a small number of preferred suppliers and from the wholesale market. Quality is therefore a crucial factor in the procurement decisions of supermarkets (Balsevich et al., Citation2003). Other elements that determine the procurement system implemented by other countries are the consumer and production geography (Codron et al., Citation2004). For example, a Turkey and Morocco study explains that the cost of implementing the centralised procurement is high when the country’s location of the urban population are widely dispersed and low when the urban population is concentration in a small area (Codron et al., Citation2004). Balsevich et al. (Citation2003) and Bienabe and Vermeulen (Citation2007) concluded that supermarket continue to source from traditional wholesale market however, there is a decline in supermarket sourcing from traditional wholesale systems. Thus, the blend of modernised procurement strategy and traditional procurement strategy is used in sourcing agriproducts from suppliers (Reardon et al., Citation2003).

One other key requirement in the procurement process is for suppliers of supermarkets to meet a variety of specifications (Bienabe & Vermeulen, Citation2007). Several authors reported that supermarket suppliers’ selection criteria were pricing, quality, safety of produce food, quantity, stability of supply, delivery timeliness, and trust connections (Boselie et al., Citation2003; Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009; Humphrey, Citation2007; Louw et al., Citation2006; Michelson, Citation2013; Neven et al., Citation2009; Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003). Balsevich et al. (Citation2003) indicated that supermarkets require their suppliers to have equipment or facilities and execute a series of value-addition operations such as washing, packaging, labelling, and transport. Heijden and Vink (Citation2013) and Louw et al. (Citation2007) on the other hand revealed the need for labels, barcoding and transportation of agriproducts to the supermarket as requirement for procuring from suppliers. Supermarkets shift these costs to the suppliers and contract only with those suppliers who are ready and able to carry these. For example, Homegrown, Kenya requires that all its suppliers have toilet and washing facilities, pesticide stores, spraying equipment, and waste pesticide disposal facilities (Boselie et al., Citation2003). The bottom line is that supermarkets will buy “from any producer (large-scale or small-scale) who meet the essential criteria and quality standards” (Bienabe & Vermeulen, Citation2007) hence there is no indication that supermarkets chain has made a concerted attempt to eliminate smallholder producers from supplying supermarkets (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009).

On contract as part of the procurement arrangements, producers have to prove themselves capable of producing the requisite quantity of products and excellent quality before being added to the “register” of preferred suppliers prior to establishing the contractual agreement (Balsevich et al., Citation2003). From recent data, supermarkets continue to have contractual agreements with their suppliers. For example, a Turkish supermarket contracted with a whole community to produce tomatoes during the warmer months (Codron et al., Citation2004). The rise in the use of contracts between supermarkets has been attributed to preferred suppliers (Andersson et al., Citation2015; Balsevich et al., Citation2003; Hu et al., Citation2004; Ogutu et al., Citation2020; Reardon et al., Citation2004). Since the 1970s, the role of contract farming in underdeveloped nations has been a source of discussion and debate (Miyata et al., Citation2009). Critics of contract farming, however, argue that, large agribusinesses use contracts to take advantage of low-cost labour and shift production risk to producers (Heijden & Vink, Citation2013; Miyata et al., Citation2009).

While reviewing quality standards of supermarket, Berdegué et al. (Citation2005) defined quality mainly in terms of the product’s appearance (i.e., spotless, uniform fruits and vegetables in terms of size, shape, colour, firmness, freshness, ripeness, etc.). Beforehand, the supermarket procurement system was that of the traditional method with the absence or little use of certifications and public or private quality standards (Codron et al., Citation2004; Reardon et al., Citation2003). For a few decades, the review found that supermarkets followed much more strict quality standards than the traditional market in their food procurement system (Ramabulana, Citation2011). For example, supermarkets in developing countries, including Latin America, South Africa, and Kenya, impose quality and safety standards on their agriproducts suppliers (Balsevich et al., Citation2003; Barrientos et al., Citation2016). While some studies in the recent past revealed that supermarket have established private safety to complement the public standards as the government cannot implement the public standards (Hu et al., Citation2004; Reardon & Farina, Citation2002; Reardon et al., Citation2003), other study revealed that supermarket considers this public standard as adequate for their needs, and do not find it critical to invest in their own private standards (Codron et al., Citation2004). Martinez and Nigel (Citation2004) observes that both public standards and private standards of the main supermarket chain are implemented to control regulatory and liability risks and as the basis of product differentiation. Citing additional confirmation, Berdegué et al. (Citation2005) argues that supermarket implements safety standards—public or private standards. For example, a South African study revealed that South African supermarket have established their own private standards that derive greatly from the Global Good Agricultural Practice (GlobalGAP) (Louw et al., Citation2007). Similarly, in Kenya, supermarkets have established their own private food standard recognised as Kenya Good Agricultural Practice (KenyaGAP), following the European food standard GlobalGAP (Dannenberg & Nduru, Citation2013). The rise of meeting quality standards in the procurement process in Africa, in particular, is due consumer demands for food safety, perceived quality of products from supermarkets, rise in income levels, the willingness to pay a premium price for quality and certified products (Alvarado & Charmel, Citation2002; Bannor et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2009).

Supermarkets shifted to a modernised procurement strategy to penetrate the sale of fresh food and vegetables as consumers demand quality products, reduce procurement costs and have a competitive advantage over the wet market

3.8. Impact of supermarket evolution on producers

Food retailing has changed massively over the continent in the last twenty years, and these transformations have had substantial ramifications for agricultural producers in emerging countries (Weatherspoon & Ross, Citation2008). Whether in Europe or Africa, supermarket sourcing have significantly impacted agrarian productivity and employment across the continent (Dolan & Humphrey, Citation2004).

The rising global food procurement has created unprecedented opportunities for developing-country producers to tap into developed-country markets (Weatherspoon & Ross, Citation2008). Until recently, providing supermarkets with vegetables, fruit, and flowers was regarded as a niche sector of African export production involving a limited number of producers. However, European supermarkets have increased their procurement from Africa over the last two decades. In the last ten years, supermarket retailing in Africa has grown significantly, headed by South Africa but increasingly extending to East African countries such as Kenya and Tanzania (Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003). European supermarkets choose to purchase from large-scale producers who can constantly deliver high-quality products on a tight but flexible plan (Dolan & Humphrey, Citation2004).

Various authors in Africa, particularly, South Africa (D’Haese & Van Huylenbroeck, Citation2005) and Kenya (Dannenberg & Nduru, Citation2013), Latin America (Ghezán et al., Citation2002; Reardon & Berdegué, Citation2002), developing countries (Reardon et al., Citation2009) and the world in general (Reardon et al., Citation2003) have exemplified how small scale and large scale farmers have either been excluded or included in the supermarket chain. Recent studies revealed that small-scale producers are involved in the supermarket chain (Bienabe & Vermeulen, Citation2007; Dannenberg & Kulke, Citation2005; Kirsten & Sartorius, Citation2002; Louw et al., Citation2008). For example, a study in India indicated that supermarkets procure their products directly from small-scale producers (Harper, Citation2010). A similar case was reported in China by Wang et al. (Citation2009) with minor roles by medium to large scale producers. A Nicaragua study by Balsevich et al. (Citation2003) reported that supermarkets source leafy greens from small or medium-scale producers whiles they source the staple items such as potatoes, tomatoes, and onions, mangoes, melons, and bananas from medium or large scale producers. It seems to suggest that the type and size of the supermarket and the type of agriproducts (processed, cereal, tubers) may determine the source (small, medium or large-scale producers) of purchase. Generally, supermarket source their products from large scale producers and eschew small scale producers (Reardon et al., Citation2009). However, there were reasons why the supermarket chose to integrate small-scale producers, many of which were country-specific (Peyton et al., Citation2015). The reasons for excluding small scale producers from the supermarket chain included their inability to meet quality and safety standards, unstable supply of produce (Dannenberg, Citation2013; Rao et al., Citation2012), lack of transportation, lack of storage facilities (Weatherspoon & Reardon, Citation2003), lack of irrigation equipment, improved seeds, other modern inputs (Rao et al., Citation2012), inadequate financial and technical skills and a lack of operational knowledge, and the inability to create scale economies (Trebbin & Hassler, Citation2012) human capital (education) (Neven et al., Citation2009) and packaging and barcoding (Louw et al., Citation2007) are the other factors that restrict small scale producers from being integrated in the supermarket chain. The reasons indicate that retailers source from large-scale farmer mainly because, among other reasons, they are able to meet required conditions and quality standards (Bienabe & Vermeulen, Citation2007). It is concluded that both small and large-scale producers are integrated in the supermarket chain (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009; Reardon et al., Citation2009).

While recent research has examined the implications for small-scale producers (Rao et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2009), the impact on productivity and efficiency has received little attention (Wang et al., Citation2009). Rao et al. (Citation2012) revealed that, businesses with supermarkets boosted farm output by 45 percent. Other studies revealed that supermarket contracts have helped increase farm output and livelihoods for small scale farmers (Michelson, Citation2013; Rao & Qaim, Citation2011; Rao et al., Citation2012). For instance, a study in China reported that contractual apple farmers benefit from increased farm outputs (presumably due to technical assistance). Impacts on income in Kenya (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009), is reported in literature. Likewise, producers in Botswana and Zambia who supplied to supermarkets, were reported to have an increase in profits compared to producers who sold at the traditional marketplaces. In Botswana, however, the difference in income between those who sold to supermarkets and producers who sold at the conventional markets was not substantial (Emongor & Kirsten, Citation2009). Nevertheless, the earnings gained from supplying to supermarkets compared to supplying to the traditional marketplace is much greater (Ogutu et al., Citation2020; Reardon & Timmer, Citation2007). Ogutu et al. (Citation2020) further stated that income gains are much larger for the richer than for the poorer households, suggesting that in spite of their poverty-reducing effects—supermarket contracts contribute to rising income inequality. This is plausible, because richer households tend to have larger farms, so they benefit more. Producers who participated in the supermarket channel, had an increase in their assets (Reardon et al., Citation2009), productivity producers (Rao et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2009), efficiency (Ogutu et al., Citation2020; Rao et al., Citation2012).

Given these benefits, Louw et al. (Citation2007) and Louw et al. (Citation2008) elucidated that farmer training, market coordination, logistical support, policy reform, access to credit and inputs are key elements for small-scale farmers’ involvement in trading with supermarkets (Louw et al., Citation2007, Citation2008; Rao et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, Andersson et al. (Citation2015) proposed the need for establishing and solidifying producers’ associations that jointly market and process outputs lowering transaction costs and increasing bargaining power. Thus, producers should be encouraged to join cooperatives, producer associations or other types of associations to receive the benefits of collective action. It was further stated that farmer training, market coordination, logistical support, policy reform and access to credit and inputs as key elements of small-scale producers’ involvement (Louw et al., Citation2007, Citation2008).

The evolution of supermarkets in the developing economies aided in poverty reduction as small-scale and large-scale producers who participated in the supermarket channel increased their farm income, assets, yield, productivity and efficiency.

4. Limitation

Articles were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. As a result, the review may have omitted some research articles that were relevant to the studies. Furthermore, because the study spanned from 2000 to the present, it did not provide the literature on the incipient stages of supermarket evolution. Furthermore, the study strictly restricted its search to articles written in English only, as well as text that was fully accessible. However, the review’s content is very accurate and informative and can be used as literature by other authors.

5. Conclusions, implications for practice and future studies

This study offers an insight into the procurement strategies adopted by supermarkets. Supermarkets at the incipient stage, sourced using the traditional procurement strategies but advanced to using a modernised strategy. Supermarkets shifted (i) from per store purchase to centralisation through distribution centres, (ii) shifted from traditional brokers to specialised/dedicated wholesalers, (iii) developing private standards for quality and safety, and (iv) the shift from sourcing in spot markets to use of preferred supplier programmes. Despite modernised procurement strategies, supermarkets astonishingly continue to source using traditional strategies. However, there is a decline in supermarket sourcing from the traditional market. Supermarket source agriproducts from any producer, whether large-scale or small-scale producer, who can meet the products requirements of the supermarket. The common requirements for suppliers of supermarkets included the quality of the produce, quantity of the produce and the availability of produce all year round or in the lean season. These requirements imply investments and a particular good agricultural practice, which might create a bottleneck for small—scale producers, especially in developing economies.

The study investigated the determinants of producer’s market outlet choice in emerging economies. The common determinants comprised lower risk due to contract, technical assistance and training provision, transparent price policy, and secure payment despite the delayed payment. Location, age, and farm size are important factors influencing the producers’ choice of the market outlet. Producers closer to supermarkets are likely to participate in the supermarket channels as transportation costs will be less. Producers who participated in the supermarket channel increased farm income, assets, total output, productivity, and efficiency. Several factors have been identified in the literature as determinants of consumer market channel choice in emerging countries: demographic factors, location factors, motivation (esteem needs, aesthetic needs), quality of agriproducts, and payment methods and are commonly cited. From the study, aesthetic factors influence African consumers to shop in supermarkets instead of the traditional market. Therefore, to compete, supermarket managers should design a more attractive environment for consumers and enhance their advantage by providing quality, variety, and service.

Consumers in underdeveloped areas want to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables at lower prices in supermarkets. Therefore, to attract and maintain consumers in underdeveloped areas, supermarket managers have to practice a just-in-time inventory management system where stocks will be kept low and also integrate vendor relationship management to reduce the cost of fresh fruits and vegetables sold at the supermarket. As some small-scale producers cannot participate in the supermarket channel due to financial constraints, a tri-partite contract is encouraged among the firm (supermarket), producers, and the financial institution. This means that supermarkets can supply quality planting materials at a subsidised rate to producers whiles financial institutions provide credit facilities, and also farmers will be able to pay back their loans to the financial institutions after payment are being made by supermarkets to the farmers.

Given that supermarkets are displacing traditional markets, a study on the impact of supermarkets on sales, among other performance indices of traditional marketing outlets, will be of tremendous policy importance. This will aid a better strategy to protect traditional markets and ensure supermarkets gain reasonable profits in the marketing of agricultural produce. Additionally, further studies will be needed to analyse the effect of improved design and attractive environment of traditional markets influence on the consumer segment that patronises supermarkets to strategically position the traditional markets in light of the strong emergence of supermarkets.

Author contribution

All authors participated in the conceptualisation, design, analysis, writing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We express our deepest gratitude to Ms Wilhemina Kwabeng Owusu for her proofreading of the draft manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data was searched from Scopus database which is readily available online

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abigail Oparebea Boateng

Abigail Oparebea Boateng is a full-time Assistant Lecturer at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies. She holds a master’s degree in Business Administration, specialising in International Business and Marketing, from PDM University (India) and a Bachelor of Science in Agribusiness from the University of Energy and Natural Resources (UENR), Ghana. Her research interest is Supply Chain Management, Inventory Management and Consumer Behavior. She is result-oriented, dedicated, and a good team player.

Richard Kwasi Bannor

Richard Kwasi Bannor (PhD Agribusiness Management, Institute of Agribusiness Management-SKRAU, India) is currently an Associate Professor of Agribusiness Management (Agribusiness Marketing Specialisation) at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies of the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Dormaa Campus, Ghana. Bannor has extensive experience in agribusiness research coupled with research publications in international peer-review journals focussing on agribusiness, business management, marketing, agriculture and applied economics. For over eight years, he has researched the development and sustaining of Agribusiness MSMEs in Africa, Asia and Europe, mainly in Agricultural and Rural Marketing and Agribusiness Value and Supply Chains. Bannor’s current research focuses on Celebrity and Digital Marketing, Food Standards, Agribusiness Consumers’ Behaviour, Labelling and Packaging), Agricultural Intellectual Property Regimes and TQM practices in Agribusiness Marketing and Supply Chains.

Ebenezer Bold

Ebenezer Bold is a young and dedicated Assistant Lecturer at the University of Energy and Natural Resources, working in the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Agribusiness from the University of Energy and Natural Resources and a Master’s degree in Business Administration with a major in International Business and Marketing from PDM University in India. Mr. Bold’s research interests revolve around Agribusiness, particularly in Total Quality Management, Food Security issues, gender studies, Consumer Behavior, Supply Chain Management, and Marketing.

Oppong-Kyeremeh Helena

Helena Oppong-Kyeremeh (PhD Agribusiness ongoing, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology) currently, is a Senior lecturer in Agribusiness at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies, Dormaa Campus, Ghana. She is a dedicated professional in the field of agribusiness. She is an experienced agricultural commodities value chain analyst trained from The University of Queensland, Australia and also skilled in food security, monitoring and evaluation through practice at Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands. Presently, her research and teaching interests focus on value chain analysis, marketing of agricultural produce, food security, consumer research, monitoring and evaluation, and poverty research.

Notes

1. Wet markets are open-air marketplaces for fresh fruits and vegetables frequently found in Asian countries.

2. Agriproducts are raw cut or fresh products of agricultural crops such as grains and cereals, root and tubers, fruits and vegetables, oilseeds etc.

References

- Alita, L., Dries, L., & Oosterveer, P. (2020). Chemical vegetable safety in China: “supermarketisation” and its limits. British Food Journal, 122(11), 3433–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2019-0627

- Alvarado, I., & Charmel, K. (2002). The rapid rise of supermarkets in Costa Rica: Impact on horticultural markets. Development Policy Review, 20(4), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00184

- Andersson, C. I. M., Chege, C. G. K., Rao, E. J. O., & Qaim, M. (2015). Following up on smallholder farmers and supermarkets in Kenya. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 97(4), 1247–1266. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aav006

- Balsevich, F., Berdegué, J. A., Flores, L., Mainville, D., & Reardon, T. (2003). Supermarkets and produce quality and safety standards in Latin America. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 85(5), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00521.x

- Bannor, R. K., & Abele, S. (2021). Consumer characteristics and incentives to buy labelled regional agricultural products. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 17(4), 872–888. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-12-2020-0173

- Bannor, R. K., Amfo, B., Oppong-Kyeremeh, H., & Chaa Kyire, S. K. (2022). Choice of supermarkets as a marketing outlet for purchasing fresh agricultural products in urban Ghana. Nankai Business Review International, 13(4), 545–566. https://doi.org/10.1108/nbri-08-2021-0059

- Barrientos, S., Knorringa, P., Evers, B., Visser, M., & Opondo, M. (2016). Shifting regional dynamics of global value chains: Implications for economic and social upgrading in African horticulture. Environment & Planning A: Economy & Space, 48(7), 1266–1283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15614416

- Berdegué, J. A., Balsevich, F., Flores, L., & Reardon, T. (2005). Central American supermarkets ’ private standards of quality and safety in procurement of fresh fruits and vegetables. Food Policy, 30(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.05.003

- Bienabe, E., & Vermeulen, H. (2007). New trends in supermarkets procurement system in South Africa: The case of local procurement schemes from small-scale farmers by rural-based retail chain stores.

- Boselie, D., Henson, S., & Weatherspoon, D. (2003). Supermarket procurement practices in developing countries: Redefining the roles of the public and private sectors. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 85(5), 1155–1161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00522.x

- Cadilhon, J. J., Fearne, A. P., Moustier, P., & Poole, N. D. (2003). Modelling vegetable marketing systems in South East Asia: Phenomenological insights from Vietnam. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 8(5), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540310500268

- Cadilhon, J. J., Moustier, P., Poole, N. D., Tam, P. T. G., & Fearne, A. P. (2006). Traditional vs. modern food systems? Insights from vegetable supply chains to Ho Chi Minh city (Vietnam). Development Policy Review, 24(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2006.00312.x

- Chowdhury, S. K., Gulati, A., & Gumbira Said, E. (2005). The rise of supermarkets and vertical relationships in the Indonesian food value chain: Causes and consequences. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 2(1 & 2), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.37801/ajad2005.2.1-2.4

- Codron, J. M., Bouhsina, Z., Fort, F., Coudel, E., & Puech, A. (2004). Supermarkets in low-income Mediterranean countries: Impacts on horticulture systems. Development Policy Review, 22(5), 587–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2004.00266.x

- Dadzie, S. H., & Nandonde, F. A. (2018). Factors influencing consumers’ supermarket visitation in developing economies: The case of Ghana. Case Studies in Food Retailing and Distribution, 2(2007). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102037-1.00005-0.

- Dannenberg, P. 2013. The rise of supermarkets and challenges for small farmers in South African food value chains. (3), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.3280/ECAG2013-003003.

- Dannenberg, P., & Kulke, E. (2005). The importance of agrarian clusters for rural areas - Results of case studies in Eastern Germany and Western Poland. Erde, 136(3), 291–309. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Peter-Dannenberg/publication/259162326_The_Importance_of_Agrarian_Clusters_for_Rural_Areas_-_Results_of_Case_Studies_in_Eastern_Germany_and_Western_Poland/links/0f3175351c2cb6aa29000000/The-Importance-of-Agrarian-Clusters-for-Rural-Areas-Results-of-Case-Studies-in-Eastern-Germany-and-Western-Poland.pdf

- Dannenberg, P., & Nduru, G. M. (2013). Practices in international value chains: The case of the Kenyan fruit and vegetable chain beyond the exclusion debate. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 104(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2012.00719.x

- Das Nair, R. (2018). The internationalisation of supermarkets and the nature of competitive rivalry in retailing in southern Africa. Development Southern Africa, 35(3), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2017.1390440

- D’Haese, M., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2005). The rise of supermarkets and changing expenditure patterns of poor rural households case study in the Transkei area, South Africa. Food Policy, 30(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.01.001

- Dolan, C., & Humphrey, J. (2004). Changing governance patterns in the trade in fresh vegetables between Africa and the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning A, 36(3), 491–509. https://doi.org/10.1068/a35281

- Emongor, R., & Kirsten, J. (2009). The impact of South African supermarkets on agricultural development in the SADC: A case study in Zambia, Namibia and Botswana. Agrekon, 48(1), 60–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2009.9523817

- Feeny, A., Vongpatanasin, T., & Soonsatham, A. (1996). Retailing in Thailand. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 24(8), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590559610150375

- Ghezán, G., Mateos, M., & Viteri, L. (2002). Impact of supermarkets and fast-food chains on horticulture supply chains in Argentina. Development Policy Review, 20(4), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00179

- Goldman, A. (2000). Supermarkets in china: The case of shanghai. International Journal of Phytoremediation, 21(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/095939600342370

- Goldman, A., Ramaswami, S., & Krider, R. E. (2002). Barriers to the advancement of modern food retail formats: Theory and measurement. Journal of Retailing, 78(4), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(02)00098-2

- Gorton, M., Sauer, J., & Supatpongkul, P. (2011). Wet markets, supermarkets and the “Big middle” for food retailing in developing countries: Evidence from Thailand. World Development, 39(9), 1624–1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.02.005

- Harper, M. (2010). Inclusive Value Chains: A Pathway Out of Poverty. World Scientific. https://doi.org/10.1142/7614

- Heijden, T. V. D., & Vink, N. (2013). Good for whom? Supermarkets and small farmers in South Africa–a critical review of current approaches to increasing access to modern markets. Agrekon, 52(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2013.778466

- Hernández, R., Reardon, T., & Berdegué, J. (2007). Supermarkets, wholesalers, and tomato growers in Guatemala. Agricultural Economics, 36(3), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00206.x

- Hollander, S. C. (1960). The wheel of retailing. Journal of Marketing, 25(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296002500106

- Humphrey, J. (2007). The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Tidal wave or tough competitive struggle? Journal of Economic Geography, 7(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm008

- Hu, D., Reardon, T., Rozelle, S., Timmer, P., & Wang, H. (2004). The emergence of supermarkets with Chinese characteristics: Challenges and opportunities for China’s agricultural development. Development Policy Review, 22(5), 557–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2004.00265.x

- Iton, A. C. W. (2017). Do demographics predict shoppers’ choice of retail outlet for roots and tubers in Trinidad and Tobago? Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 7(3), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-05-2016-0035

- Kirsten, J., & Sartorius, K. (2002). Linking agribusiness and small-scale farmers in developing countries: Is there a new role for contract farming? Development Southern Africa, 19(4), 503–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835022000019428

- Lin, P. C., & Wu, L. S. (2011). How supermarket chains in Taiwan select suppliers of fresh fruit and vegetables via direct purchasing. The Service Industries Journal, 31(8), 1237–1255. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060903437568

- Louw, A., Jordaan, D., Ndanga, L., & Kirsten, J. F. (2008). Alternative marketing options for small-scale farmers in the wake of changing agri-food supply chains in South Africa. Agrekon, 47(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2008.9523801

- Louw, A., Vermeulen, H., Kirsten, J., & Madevu, H. (2007). Securing small farmer participation in supermarket supply chains in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 24(4), 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350701577657

- Louw, A., Vermeulen, H., & Mad, H. (2006). Integrating small-scale fresh produce producers into the mainstream agri-food systems in South Africa: The case of a retailer in Venda and local farmers. Proceedings of the International Conference on Management in AgriFood Chains and Networks, Cairo, Egypt (pp. 1–12).

- Lu, H., Trienekens, J. H., Omta, S. W. F., & Feng, S. (2008). Influence of guanxi, trust and farmer-specific factors on participation in emerging vegetable markets in China. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 56(1–2), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-5214(08)80015-2

- Martinez, G. M., & Nigel, P. (2004). The development of private fresh produce safety standards: Implications for developing Mediterranean exporting countries. Food Policy, 29(3), 229–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2004.04.002

- Maruyama, M., & Trung, L. V. (2006). Supermarkets in Vietnam: Opportunities and obstacles. Asian Economic Journal, 21(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8381.2007.00245.x

- McNair, M. P. (1958). Significant trends and developments in the postwar period. In Smith A. B. (Ed.),competitive distribution in a free, high-level economy and its implications for the University. University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Meng, T., Florkowski, W. J., Sarpong, D. B., & Chinnan, M. S. (2014). Consumer ’ s food shopping choice in Ghana. Supermarket or Traditional Outlets?, 17, 107–130. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.164600

- Mergenthaler, M., Weinberger, K., & Qaim, M. (2009). The food system transformation in developing countries: A disaggregate demand analysis for fruits and vegetables in Vietnam. Food Policy, 34(5), 426–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.03.009

- Michelson, H. C. (2013). Small farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart World: Welfare effects of supermarkets operating. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 95(3), 628–649. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas139

- Minten, B., Randrianarison, L., & Swinnen, J. F. M. (2009). Global retail chains and poor farmers: Evidence from Madagascar. World Development, 37(11), 1728–1741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.024

- Minten, B., & Reardon, T. (2009). Food prices and modern retail: The case of Delhi International food Policy research Institute New Delhi food prices and modern retail: The case of Delhi. World Development, 38(12), 0–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.04.002

- Minten, B., Reardon, T., Minten, B., & Reardon, T. (2008). Food prices, quality, and quality’s pricing in supermarkets versus traditional markets in developing countries. Review of Agricultural Economics, 30(3), 480–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2008.00422.x

- Miyata, S., Minot, N., & Hu, D. (2009). Impact of contract farming on income. Linking small farmers, packers, and supermarkets in China. World Development, 37(11), 1781–1790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.025

- Nandonde, F. A., Kuada, J., & Nandonde, F. A. (2018). Perspectives of retailers and local food suppliers on the evolution of modern retail in Africa. British Food Journal, 120(2), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2017-0094

- Neven, D., Odera, M. M., Reardon, T., & Wang, H. (2009). Kenyan supermarkets, emerging middle-class horticultural farmers, and employment Impacts on the rural poor. World Development, 37(11), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.026

- Neven, D., & Reardon, T. (2004). The rise of Kenyan supermarkets and the evolution of their horticulture product procurement systems. Development Policy Review, 22(6), 669–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2004.00271.x

- Neven, D., Reardon, T., Chege, J., Wang, H., & Reardon, T. (2008). Supermarkets and consumers in Africa supermarkets and consumers in Africa: The case of Nairobi, Kenya. October, 2014, 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1300/J047v18n01

- Nickanor, N., Kazembe, L. N., Crush, J., & Wagner, J. (2020). Revisiting the African supermarket revolution: The case of Windhoek, Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 38(2), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1819774

- Ogutu, S. O., Ochieng, D. O., & Qaim, M. (2020). Supermarket contracts and smallholder farmers: Implications for income and multidimensional poverty. Food Policy, 95(October 2019), 101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101940

- Okello, J. J., Lagerkvist, C., Hess, S., & Ngigi, M. (2012). Original article choice of fresh vegetable retail outlets by developing-country urban consumers: The case of Kale consumers in Nairobi, Kenya. 24(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2011.58

- Oppong, D., Bannor, R. K., & Serpa, S. (2022). Gender and power work relationships;: A systematic review on the evidence from Africa and Asia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2031686

- Peyton, S., Moseley, W., & Battersby, J. (2015). Implications of supermarket expansion on urban food security in Cape Town, South Africa. African Geographical Review, 34(1), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2014.1003307

- Ramabulana, T. R. (2011). The rise of South African agribusiness: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Agrekon, 50(2), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2011.589984

- Rao, E. J., Brümmer, B., & Matin, Q. (2012). Farmer participation in supermarket channels, production technology, and efficiency: The case of vegetables in Kenya. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 94(4), 891–912. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas024

- Rao, E. J. O., & Qaim, M. (2011). Supermarkets, farm Household income, and poverty: Insights from Kenya. World Development, 39(5), 784–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.09.005

- Reardon, T. (2006). The rapid rise of supermarkets and the use of private standards in their food product procurement systems in developing countries. In R. Ruben, M. Slingerland, & H. Nijhoff (Eds.), Agro-food Chains and Networks for Development (pp. 79–105). Springer.

- Reardon, T., Barrett, C. B., Berdegué, J. A., & Swinnen, J. F. M. (2009). Agrifood industry transformation and small farmers in developing countries. World Development, 37(11), 1717–1727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.023

- Reardon, T., & Berdegué, J. A. (2002). The rapid rise of supermarkets in Latin America: Challenges and opportunities for development. Development Policy Review, 20(4), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00178

- Reardon, T., & Farina, E. (2002). The rise of private food quality and safety standards: Illustrations from Brazil. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 4(4), 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7508(02)00067-8

- Reardon, T., & Gulati, A. (2008). The rise of supermarkets and their development implications: International experience relevant for India. (no. 589-2016-39798).

- Reardon, T., Henson, S., & Berdegué, J. (2007). Proactive fast-tracking diffusion of supermarkets in developing countries: Implications for market institutions and trade. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(4), 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm007

- Reardon, T., & Hopkins, R. (2006). The supermarket revolution in developing countries: Policies to address emerging tensions among supermarkets, suppliers and traditional retailers. European Journal of Development Research, 18(4), 522–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810601070613

- Reardon, T., & Minten, B. (2011). Surprised by supermarkets: Diffusion of modern food retail in India. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 1(2), 134–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/20440831111167155

- Reardon, T., & Swinnen, J. F. M. (2004). Agrifood sector liberalisation and the rise of supermarkets in former state-controlled economies: A comparative overview. Development Policy Review, 22(5), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2004.00263.x

- Reardon, T., & Timmer, C. P. (2007). Transformation of markets for agricultural output in developing countries since 1950: How has thinking changed? Handbook of Agricultural Economics, 3, 2807–2855. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0072(06)03055-6

- Reardon, T., & Timmer, C. P. (2014). Five inter-linked transformations in the Asian agrifood economy: Food security implications. Global Food Security, 3(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.02.001

- Reardon, T., Timmer, C. P., Barrett, C. B., & Berdegué, J. (2003). The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 85(5), 1140–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2003.00520.x

- Reardon, T., Timmer, C. P., & Berdegue, J. A. (2003). The rise of supermarkets and private standards in developing countries: illustrations from the produce sector and hypothesized implications for trade. Paper presented at the International Conference on Agricultural Policy Reform and the WTO: Where Are We Heading? 23–26 June, Capri.

- Reardon, T., Timmer, P., & Berdegue, J. (2004). The rapid rise of supermarkets in developing countries: Induced organizational, institutional, and technological change in agrifood systems. EJADE: Electronic Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics, 1(2), 168–183. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.12005

- Reardon, T., Timmer, C. P., & Minten, B. (2010). Supermarket revolution in Asia and emerging development strategies to include small farmers. PNAS, 109(31), 12332–12337. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003160108

- Shankar, B., Posri, W., & Srivong, T. (2011). A case study of a contract farming chain involving supermarkets and smallholders in Thailand *. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2010.9669335

- Stringer, R., Sang, N., & Croppenstedet, A. (2009). Producers, processors, and procurement decisions: The case of vegetable supply chains in China. World Development, 37(11), 1773–1780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.027

- Traill, W. B. (2006). The rapid rise of supermarkets? Development Policy Review, 24(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2006.00320.x

- Trappey, C. V., & Kuan Lai, M. (1996). Retailing in Taiwan: Modernization and the emergence of new formats. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 24(8), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590559610150366

- Trebbin, A., & Hassler, M. (2012). Farmers’ producer companies in India: A new concept for collective action? Environment and Planning A, 44(2), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44143

- United Nations. (2003) . Department of international economic, United Nations. Department for economic, social information, policy analysis, & social affairs. Population division, World urbanization prospects. (no. 237). United Nations, Department of International.

- Wang, H., Dong, X., Rozelle, S., Huang, J., & Reardon, T. (2009). Producing and procuring horticultural crops with Chinese characteristics: The case of Northern China. World Development, 37(11), 1791–1801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.08.030

- Wanyama, R., Gödecke, T., Chege, C. G. K., & Qaim, M. (2019). How important are supermarkets for the diets of the urban poor in Africa? Food Security, 11(6), 1339–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00974-3

- Weatherspoon, D. D., & Reardon, T. (2003). The rise of supermarkets in Africa: Implications for agrifood systems and the rural poor. Development Policy, 21(3), 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00214

- Weatherspoon, D., & Ross, A. (2008). Designing the last Mile of the supply chain in Africa: Firm expansion and Managerial Inferences from a Grocer. International Food and Agribusiness Management, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.53625

- Winter, C. (2007). South Africa, Republic of retail-food sector supermarket expansion in South Africa and Southern Africa: Distribution and procurement practices of four supermarket chains. GAIN report. USDA Foreign Agriculture Service.

- Zhang, Q. F., & Pan, Z. (2013). The transformation of urban vegetable retail in China: Wet markets, supermarkets and Informal markets in Shanghai. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 43(3), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.782224