?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study uses evidence gathered from survey responses from 572 rural households in Ghana to examine the link between organic expenditure and off-farm income. To solve the endogeneity problem related to off-farm income, we use the instrumental variable Tobit model. The findings showed that expenditure on organic food was strongly and favorably connected to off-farm income. According to the disaggregated findings, female off-farm income is significantly more positively correlated with organic food expenditure than male off-farm income. The results provide practical implications for facilitating organic food consumption and eliminating food and nutrition insecurity among rural dwellers.

1. Introduction

Organic food consumption is essential to improving the nutritional status of households and enhancing food security, especially for those living in rural areas (Johansson et al., Citation2014; Ueasangkomsate & Santiteerakul, Citation2016; Yadav & Pathak, Citation2016). The demand for organic food has risen worldwide in recent years (Hurtado-Barroso et al., Citation2019; Mohammed, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2019; Yadav & Pathak, Citation2016) due to the increased recognition of nutritional composition in organic food. Compared with conventional food, organic food consumption contributes to optimal health status and reductions in contracting chronic disease risks. Previous research has shown that eating organic foods lowers the risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women as well as the risk of cardiovascular diseases and genital organ problems (De Lorenzo et al., Citation2010; DiDaniele et al., Citation2014; Hurtado-Barroso et al., Citation2019; Juhler et al., Citation1999; Keraita & Drechsel, Citation2015; Torjusen et al., Citation2014). For instance, Johansson et al. (Citation2014) indicated that organic crops have more bioactive compounds that reduce chronic disease risks than conventional crops.

Despite the benefits mentioned above, previous studies have reported that organic food consumption is minute among low-income households (Asif et al., Citation2017; Bryła, Citation2016; Kapuge, Citation2016; Marian et al., Citation2014; Owusu & Anifori, Citation2013). For example, Bryła (Citation2016) found that high price is the critical barrier deterring people from organic food consumption in Poland. Likewise, Marian et al. (Citation2014) revealed that Denmark’s low-income generation is disadvantaged in organic food consumption. In developing countries, Owusu and Anifori (Citation2013) and Kapuge (Citation2016) for Ghana and Sri Lanka argued that household income positively affect consumption of organic food. These findings indicate that the distinction between conventional and organic food prices is conceivably the most significant concern during purchase decisions, i.e., low-level income impedes the poor from consuming organic foods. Thus, improving household income through different channels (e.g., increasing agricultural production, encouraging participation in off-farm works, and accessing credit services and other financial aids) becomes a necessity to promote organic food consumption, especially for those living in poor rural areas (Atakora, Citation2016; Ma et al., Citation2019).

Off-farm generated income is vital in improving rural household income and ameliorating smallholder farmer livelihoods (Bukari et al., Citation2021; Rahman & Mishra, Citation2020). The benefits of off-farm income in increasing agricultural output and reducing rural poverty have been widely shown (Dedehouanou et al., Citation2018; Dzanku, Citation2015; Owusu et al., Citation2011; Zereyesus et al., Citation2017), as well as rural households’ decisions on energy expenditure (Ma et al., Citation2019) and food expenditure (Démurger & Wang, Citation2016; Y; Liu et al., Citation2019; Rahman & Mishra, Citation2020). According to Ma et al. (Citation2019), off-farm generated income is positively related to Chinese rural households’ expenditures on electricity and gas, however, a negative relationship was found regarding spending on coal. The studies by Seng (Citation2015), Mishra et al. (Citation2015), and Liu et al. (Citation2019) showed a significant effect of off-farm income on household consumption expenditure in Cambodia, Bangladesh, and China, respectively. Off-farm income has a beneficial effect on India’s food security, nutrition, and food spending, according to Rahman and Mishra (Citation2020). According to Owusu et al. (Citation2011) and Kuwornu et al. (Citation2018), off-farm income in Ghana has a favorable impact on the food security status of farming households.

No research has been done on how off-farm income affects the price of organic produce. However, prior research that has examined the connections between off-farm income and household spending habits (e.g., total household expenditure, energy expenditure, or food expenditure) has argued that rural households in developing countries cannot patronize organic foods and products due to low income (Liu et al., Citation2019; Owusu & Anifori, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, the significant income-improving effect of off-farm income indicates that it holds considerable potential to facilitate organic food consumption among rural households (Ma et al., Citation2019). Thus, looking at the connection between off-farm income and spending on organic food is crucial.

This study uses data from rural households in Ghana to make the first attempt at analyzing the variations in expenditure on organic food induced by off-farm income. Ghana as a case study present an interesting discussion. First, the national government is putting down measures/policies (e.g., the launching of the “Ghana Green Label Manual” training tool) aimed at promoting organic food production and consumption. Also, Ghana’s organic food production and consumption is booming since more people place high importance on food safety according to the 2015 report of the agricultural sector. However, its consumers are mostly high-income people due to its high price. This implies that inadequate income have a negative impact on food consumption (organic foods). More so, prior studies in Ghana has shown that off-farm income significantly promotes food safety (e.g., Ankrah Twumasi et al., Citation2021). Hence, this research work is timely and appropriate for policy designing programs of the national government aimed at ensuring food safety and development.

We make contributions to the existing literature from two aspects. First, an instrumental variable model is used in this study to handle the endogenous issue of off-farm income. The endogeneity problem emerges as a result of farmers choosing (self-selecting) to engage in off-farm activities and generate revenue. Estimation bias would occur from ignoring the selection bias issue. Second, we examine how gender affects the connection between spending on organic produce and revenue from outside the farm. Notably, we distinguish between income generated by men and women in the overall off-farm income. The disparity in off-farm income between men and women could have an uneven impact on the cost of organic food. Males usually have a higher financial obligation than females (Siaw et al., Citation2020), and they may prefer quantity over quality in food expenditure, thus, indicating the potential heterogeneous off-farm income effects, which previous studies have neglected.

The paper’s organization is as follows: Section 2 overviews organic food production and consumption in Ghana and the data collection procedure. In Section 3, the empirical approach is introduced (i.e., model selection and variable measurement). The empirical findings are the main topic of Section 4. Finally, section 5 presents the conclusion and policy implications.

2. Organic food in Ghana and data collection procedure

2.1. Organic food production and consumption in Ghana

Ensuring food and nutritional security is a big concern worldwide. A vital pathway to promoting sustainable development and improving food security is encouraging organic food consumption, as the benefits of organic food have been widely proved (Kapuge, Citation2016; Marian et al., Citation2014; Raynolds, Citation2004). As of 2015, the world recorded 81.6 billion USD in organic food market globally. By 2015, countries that adopted organic system of agriculture (77 in 1999) had reached 190 (FiBL, Citation2021). In particular, many developing countries have shown great interest in organic food production because of its income creation effect and contributions to economic growth. For example, in developing countries, organic farming land increased from 52 thousand hectares in 2000 to over one million hectares in 2014 (Willer & Lernoud, Citation2016).

According to Ghana’s Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) data from 2015, organic food production and consumption are also increasing in Ghana. The government’s launch of the “Ghana Green Label Manual” training tool in 2015 to encourage organic and green farming or production indicates that organic food demand has increased. Also, Ghana’s food expenditure per capita (including organic foods) increased from 508.9 USD in 2014 to 576.8 USD in 2017 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2018). According to a study by Owusu and Anifori (Citation2013) conducted in Ghana, sales of organic farming products have increased as more people currently place high importance on food safety. However, its consumers are mostly high-income people due to its high price. Prior studies in Africa have revealed that aside from organic food health and environmental benefits, only the elite are significant consumers (Owusu & Anifori, Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2019). Without sufficient funds, rural dwellers will not patronize organic food. Therefore, understanding the bit played by off-farm income (a great contributor to rural household income) in promoting organic food consumption is critical. The analysis for this study was done using survey data from Ghana.

2.2. Data collection procedure

Five hundred and seventy-two (572) rural households were the subject of a survey in Ghana. The survey was done within 3 months (April to June 2020). To choose the regions, districts, villages, and respondents households, we used a multi-stage sampling technique. Four regions were chosen for the first stage: the Eastern region in southeast Ghana, the Central region in southwest Ghana, the Bono East region in the center of Ghana, and the Savannah region in the north of Ghana. Second, one district was chosen at random from each region. They are the East Gonja District in the Savannah area, the Kwahu Afram Plains District in the Eastern region, the Ekumfi District in the Central region, and the Atebubu Amantin District in the Bono East region, and so on. The third stage was the random selection of 30–40 agricultural households from three communities within the identified districts. The process produced a total of 572 responses, of which 246 have organic food consumption experience, and 326 households have no organic food consumption experience.

We gathered information on socioeconomic traits (such as gender, age, and household size), off-farm employment status, organic food spending, and other factors that are relevant to the study’s objective. Ghana’s definition of “organic food” is exclusive to food produced without the use of synthetic pesticides and artificial fertilizers (Keraita & Drechsel, Citation2015). In light of this, we give sampled farmers in-depth information to assist them in differentiating the cost of conventional and organic foods. We conducted a pre-test of the questionnaire to eliminate any potential uncertainty. We were able to conduct a face-to-face interview with the help of enumerators who speak the local languages.

3. Empirical strategy

3.1. Model selection

The expenditure of organic food is a truncated continuous variable in this study since it could take zero value if the respondents do not enjoy any organic food. Previous studies have posited the unsuitability of Ordinary Least Square (OLS) model in evaluating dependent variables that possess zero values or are censored (Foster & Kalenkoski, Citation2013; Wilson & Tisdellt, Citation2002). Expenditure on organic food, in this study, is a continuous variable that has truncated as it may possess zero values in cases where respondents have no organic food consumption experience. Therefore, this study employed the Tobit model for the estimation because it is most appropriate for the study compared to the OLS model.

The Tobit model might accurately predict the effect of income from off-farm job on organic food expenses if all explanatory factors are exogenous. However, as was previously mentioned, there may be a potential endogeneity problem stemming from off-farm revenues due to some reasons. First, rural households choose whether or not to engage in off-farm activities; hence the distribution of off-farm employment among households is not random (Burgess et al., Citation2016; Ma et al., Citation2019; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2009). Second, farmers who do not engage in off-farm employment may find it hard to consume organic foods because of financial constraints. In contrast, farmers who work outside the farm are less likely to experience these problems since they get paid for their off-farm endeavors. Therefore it is worth addressing the endogeneity issue.

Due to the dependent variable’s censored and continuous form and the endogeneity issue associated with the off-farm generated income variable, this study utilized the instrumental variable Tobit (IV-Tobit) approach (Deng et al., Citation2018; Ma et al., Citation2019; Xu et al., Citation2019). The IV-Tobit model consists of a two-stage estimation. Precisely, stage one models off-farm income, and stage two models the expenditure on organic, which can be expressed as:

Where is household

off-farm income;

denotes the latent variable, and

denotes the observed amount that household

spent on organic food;

stands for the explanatory variable index (for example household size, gender, and age);

is an instrumental variable used for identification;

,

,

, and

are parameters that need to be estimated;

and

are two error terms.

The IV-Tobit model requires the inclusion of in EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) for model identification. Following Ma et al. (Citation2018), we select the social network variable as the IV. The social network variable is a binary variable indicating whether the respondents have links with relatives who can help them find an off-farm job. Help from others is predicted to enhance the likelihood of off-farm employment and have an impact on off-farm income, but it has no immediate impact on the cost of organic food. According to Ma et al. (Citation2018), households with friends and family members who work in the city are more likely to find off-farm employment, which could boost household income. The validity of the chosen IV was examined in this study utilizing a Pearson correlation coefficient analysis. The chosen IV and the treatment variable (off-farm income), as shown in Table in the Appendix, are positively and statistically associated; however, they are not substantially correlated with the outcome variable (organic food expenditure). This demonstrates that the IV used in this investigation is suitable.

3.2. Variable measurement

In this study, expenditure on organic food organic food expenditure designates the annual household organic food (vegetables and fruits) consumption value, measured at GH¢ 1,000/capita. We focus on organic vegetable and fruit consumption because vegetables are Ghana’s most common organic food (Owusu & Anifori, Citation2013). Off-farm income refers to annual off-farm wages/salaries, pension, and remittances, which are also measured at GH¢ 1,000/capita. The definition is accurate to Ma et al. (Citation2019). We further distinguish off-farm income earned by males and females, indicated as male-earned and female-earned income.

We follow previous literature (Y. Liu et al., Citation2019; Ma et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Owusu & Anifori, Citation2013; Ueasangkomsate & Santiteerakul, Citation2016; Yadav & Pathak, Citation2016; Zereyesus et al., Citation2017), regarding control variables, by choosing respondents’ gender, age, squared age, education, marital status, members in urban area status, number of children, availability of non-fixed assets (NFA), availability of finance, perception of prices, size of farms, and regions as dummies.

Based on the selected variables, we expect the following outcome. Since female household expenditures are less than males in Africa, we expect male respondents to seek more off-farm work than females and not patronize organic foods. The nutrient-Sant study in France also showed that females consume more organic foods than males (Hercberg et al., Citation2010). Additionally, we anticipate that older people will enjoy more organic food but will be less inclined to participate in activities that are not related to farming. Yadav and Pathak (Citation2016) revealed that older people are more likely to consume healthy food such as organic products than young ones due to health concerns. Besides, we expect the education variable to positively affect off-farm income and organic food expenditure. Education equips individuals to partake in off-farm jobs (Seng, Citation2015). According to Owusu and Anifori (Citation2013), enlightens individuals’ knowledge of the essential benefits of consuming organic food. We anticipate that married persons will look for non-farm occupations to boost household income and expenses. Again, our expectation for respondents with family members in the city is positive for expenditure on organic food and income from off-farm. Ma et al. (Citation2019) posited that household migrant members seek off-farm work for their family members when the need arises.

We expect that having more children will have a negative impact on both the total expenditure on organic food and the revenue from off-farm activities. An increase in family size accompanies a decrease in time spent engaging in non-farm activities. Thus, the farmers must trade catering for children and participate in off-farm activities (Y. Liu et al., Citation2019; Ma et al., Citation2018). Likewise, a large-size household may not consume organic food due to high household expenditure and low-income generation. Accessibility to NFA and credit increases the likelihood that a household’s income will increase (Argaw et al., Citation2017; Hussain & Thapa, Citation2016). Thus, households can establish off-farm work and also be able to consume organic food should income increase. Therefore, we expect access to NFA and credit to positively affect income from off-farm jobs and expenditure on organic foods. Finally, a farmer who perceives organic food expenditure as expensive is less likely to consume them. As a result, it is envisaged that perception and spending on organic food will be negatively correlated.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Descriptive results

Table gives descriptive statistics and variable definitions. According to the data, an average household spends GH 310 on organic food. Sample households’ average annual income from off-farm sources is GH 2,970. The mean age of the sampled group is 42, while the male percentage is 69. About 27 percent of respondents have completed high school or more, and 71 percent of the respondents are married. There are around five children within the sample households. About 41 percent and 55 percent of respondents have access to NFA and credit, respectively. Also, 33% of sample respondents perceive that organic foods are expensive. The average farm size owned by a respondent is 4.34 acres of land.

Table 1. Variable definitions and data description

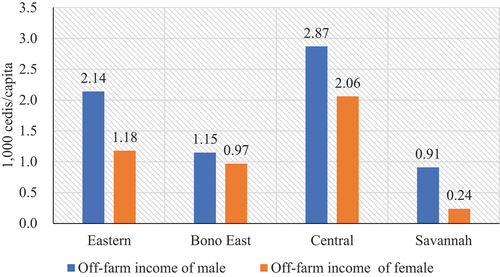

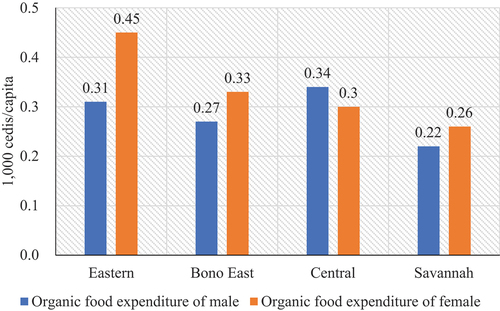

Figure illustrates the average off-farm income by gender in the four regions. The figure shows that males dominate off-farm work across the regions. There are significant variations between male-earned income and female-earned income from off-farm activities at the regional level. For example, the average off-farm income of males in the Central region (GH¢ 2,870/capita) is higher than their female counterparts (GH¢ 2,060/capita). Figure shows significant differences between males and females regarding average organic food expenditure. Specifically, the females’ average organic food expenditure is higher than the males in all the selected regions except the Central region.

4.2. Empirical results

Columns 2 through 5 of Table display the estimation outcomes for the IV-Tobit model, which were jointly calculated using EquationEquations (1(1)

(1) ,Equation2

(2)

(2) ). We also determine and report the associated marginal effects of variables because the coefficients cannot be simply understood. In particular, columns 2 and 3 describe the first stage of the IV-Tobit model, which offers helpful insights into the factors that influence off-farm income. The factors influencing the cost of organic food were displayed in columns 4 and 5. As shown in Table , the Wald

is significant at the 1% level, demonstrating the endogenous nature of off-farm income and the suitability of the IV-Tobit model for this investigation.

Table 2. Off-farm income and organic food expenditure nexus estimation: IV-Tobit and Tobit model estimates

4.2.1. Determinants of off-farm income

The gender variable has a statistically significant marginal effect, as seen in the third column of Table , with males having an 8.1 percent higher off-farm income than females. This conclusion may be explained by the fact that men in Ghana have a higher proportion of off-farm employment options, making them more inclined to engage in such activities to raise their household income. This result backs up Liu et al. (Citation2019)’s assertion that male household heads in China are more likely to earn larger off-farm income. The findings reveal that a higher education level boosts revenue from off-farm activities by 5%, showing that education and off-farm jobs nexus is positive and statistically significant. The findings are consistent with those of Babatunde and Qaim (Citation2010), who demonstrated that household heads levels of education have a favorable impact on their revenues from both agricultural and off-farm sources in Nigeria. Higher education levels aid farmers in acquiring the technical skills necessary for off-farm work and give them a competitive advantage in terms of career options, according to Woldeyohanes et al. (Citation2017).

The results showed that marginal effect of marital status significant and positive, interpretating that farmers who are married earn 1.3% higher off-farm income. The married farmer can observe a labor division, where one partner participates in off-farm work while the other partner concentrates on the farm activities; hence, boosting revenue from off-farm jobs. The outcome agrees with Siaw et al. (Citation2020), who discovered that labor division improves farm households’ income. The result also shows that respondents with family members in the urban area tend to have 1.1% higher off-farm income than their counterparts without such an advantage. Family members in the cities are more likely to help their members in rural areas find a job in the city (Ma et al., Citation2019). The statistically significant and positive marginal effect of the access to credit variable indicates that access to credit raises off-farm income by 4.5 percent. Farmers who have access to loans may be able to start a non-agro business to raise overall household income. This result is in line with Ma et al. (Citation2018), who discovered a considerable beneficial impact of loan availability on off-farm income in China.

Respondents in the Eastern and Central areas are more likely to have an off-farm income that is 12.7 percent and 11.5 percent more, respectively, than respondents who live in Savannah. The results show that spatial heterogeneities (agricultural climate, environment resources, availability, and access to agricultural institutions and infrastructure) impact farmers’ earnings from off-farm sources. Finally, the social network has a positive correlation with off-farm income, suggesting that farmers with relatives who can assist them in finding an off-farm employment are likely to have an off-farm income that is 5.4 percent greater. The findings of Ma et al. (Citation2019) for China and Pfeiffer et al. (Citation2009) for Mexico are in agreement with this outcome.

4.2.2. Determinants of organic food expenditure

The marginal effect of the off-farm income variable is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level, according to columns 4 and 5 of Table . More specifically, a one-unit increase in off-farm income would result in a 1.9 percent rise in the cost of organic food. Low household income limits healthy organic products and food consumption (Owusu & Anifori, Citation2013). Therefore, increasing off-farm income helps expand total household income, enabling households to consume organic foods. These results support earlier research (Dedehouanou et al., Citation2018; Impiglia & Lewis, Citation2019; Y; Liu et al., Citation2019; Rahman & Mishra, Citation2020), which reported participating in off-farm activities increases households’ incomes, which finally enhances household food expenditure. For instance, Liu et al. (Citation2019) made the case that increased income from non-farming pursuits might allow farmers to increase their spending on food, particularly organic goods. The findings (see the last column of Table ) support the hypothesis that income from non-farm employment has a favorable impact on the cost of organic food.

With regard to other control factors, the age variable’s positive and significant marginal effect shows that an increase of one year in age would result in a 0.3 percent rise in organic food intake. This result is in line with research by Yadav and Pathak (Citation2016) and Ghali (Citation2020), which shows that elderly adults consume more organic food than younger people for health-related reasons. The positive relationship between education and organic food expenditure suggests a 1.4% increase in spending on organic foods for educated farmers. Education broadens the individuals’ knowledge to capture organic foods’ health benefits; hence, they patronize them. This result agrees with Owusu and Anifori (Citation2013), who reported that organic food consumption is dominant among highly educated individuals in Ghana. Households with more children spend 0.9% less on organic food, according to a negative and statistically significant marginal effect of the children variable. To reduce excess household expenditure, these farmers may refrain from expensive food consumption, such as organic foods. The result confirms the studies of Annim et al. (Citation2011), who found that larger-sized families prefer food quantity to quality due to budget constraints.

Access to NFA is also significant and positive, indicating that for farmers who have non-fixed assets, organic expenditure is likely to increase by 0.3%. We discover that a 2.1% increase in expenditure on organic food is caused by access to credit; this implies that credit accessibility assists poor households in diversifying into businesses that might increase household income. Also, households facing budget constraints may be financially sound through credit accessibility (Ma et al., Citation2020). Table reveals that farmers spend 1.1% less on organic food if they perceive organic food are expensive. All other things being equal, people are sensitive to pricing and will spend their meager resources on affordable goods. This finding supports the claims by Goldsmith et al. (Citation2010) and Liu et al. (Citation2019) that expensive products are less consumed. Finally, respondents residing in Eastern, Central, and Bono East regions have higher organic food expenditure than those living in the Savannah region.

4.2.3. Disaggregated analysis by gender

We disaggregated the organic food expenditure by gender to extend the understanding of organic food spending caused by income from off-farm work. The findings (see the last column of Table ) indicate a significant increase in male and female organic food expenses caused by income generated from off-farm work. However, the magnitude of female spending on organic food is more significant than that of male-earned off-farm income. The reason may be attributed to women’s primary role as household cooks in many parts of Africa. Therefore, women may increase organic food expenditure to increase the dietary quality of the food. Another reason is that males in developing countries like Ghana have a substantial financial responsibility compared to females (Siaw et al., Citation2020); therefore, they may prefer to spend less on organic food to reduce household expenditure. Finally, women are more concern with their health status and the shape of their body, therefore, more likely to consider quality to quantity food (Gundala et al., Citation2022). This outcome supports Issahaku and Abdulai (Citation2020) study, which found that women are more likely than men to increase the nutritional quality of family foods.

Table 3. Disaggregated analysis by gender: IV-Tobit model estimates

4.2.4. Further analysis

We use two different outcome variables to further deepen our understanding of the connection between off-farm income and organic food spending. Specifically, the status of consuming organic food, which is expressed as a binary variable indicating whether a responder does so, and the frequency with which a household consumes organic food, which is expressed as a count variable. We apply the IV-Probit and IV-Poisson models, respectively, in light of the two variables’ respective characteristics. The outcomes are displayed in Table ‘s columns 2 and 3. It demonstrates how money from employment that is not on a farm positively affects whether or not people consume organic food, suggesting that having an off-farm income boosts one’s likelihood and capacity to do so. The findings in Table are somewhat supported by the outcomes shown in Table .

Table 4. Off-farm income and organic food consumption status and intensity nexus estimation

5. Conclusions and policy implications

In this study, which used household survey data from four areas of Ghana (the Eastern, Central, Bono East, and Savannah), we looked at the relationship between off-farm income and expenditure on organic food. The IV-Tobit was used to overcome the endogeneity problem associated with off-farm revenue. We also did a gender-differential analysis of male and female off-farm generated income.

The IV-Tobit model estimates showed that income from non-farm labor greatly increases spending on organic food. In particular, a unit increase in revenue from sources other than farms would result in a 1.9 percent increase in spending on organic food. In other words, people eat more organic food as their income from outside the farm rises. The disaggregated estimate revealed that female earned income from off-farm labor had a greater impact on the expenses of organic food than male earned income. In addition, we discovered that access to finance, pricing perception, social networks, and regional dummies affect respondents’ off-farm income.

Our findings offered practical implications for facilitating organic food consumption and increasing rural household income. First, the significant positive effect of income from off-farm work on the organic food expense suggests that policymakers could prioritize income earning opportunities through off-farm activities in rural areas. Thus, the government should provide conducive environment (e.g., good infrastructure such as internet connectivity, electricity, and health centers) in rural areas to attract investors to create jobs in such areas for the residents. This will boost rural dwellers’ income diversification, improving rural households’ organic food expenditure. Second, our results revealed that rural residents are less likely to consume organic food because of the perception that organic food is expensive; therefore, the government should subsidize the price of organic foods and products in rural areas. Third, we also found that males’ access to off-farm income is paramount. However, females are more likely to consume organic food. Thus, enhancing off-farm opportunities for women should be mainly considered. Finally, the higher consumption of organic food among older adults compared to younger ones calls for organic food awareness programs in youth dominated areas such as schools and clubs.

The limitation of the study had to do with several issues. First, our results showed that the focused group was fewer, but this could be attributed small sample size we had due to financial constraint. We recommend future studies to consider larger sample size to display a more understanding to this kind of studies. Second, our data only focused on organic fruits and vegetables rather than other kinds of organic products; thus, we suggest that forthcoming studies will look at the other kind of organic product’s effect of off-farm income.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful review and critical comments. The authors also extend enormous gratitude to the rural dwellers who participated in the data collection. Hongyun Zheng acknowledges the financial support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2662022JGQD006).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martinson Ankrah Twumasi

Martinson Ankrah Twumasi is a research fellow in the College of Economics at Sichuan Agriculture University, China. His major interests include Rural Finance, Agricultural Economics, Agricultural Development, Development Economics, Econometrics, Financial Economics, Microeconomics, Macroeconomics, Regional Economics, Sustainable Agriculture and Regional Rural Development. He has good research publications in the world-leading journals databases that having indexing of the Web of Science.

Hongyun Zheng

Hongyun Zheng is an Associate Professor at the College ofEconomics and Management, Huazhong Agricultural University, China. His research areas include ICT adoption, farmer’s well-being, and rural development.

Isaac Owusu Asante

Isaac Owusu Asante is a post doctoral research fellow lecturer in the the School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiatong University, Chengdu, China. His major interests include Strategic Management, Information System Management and E-Business. He has good research publications in the world-leading journals databases that having indexing of the Web of Science.

Evans Brako Ntiamoah

Evans Brako Ntiamoah is an consultant in Ghana and a researcher in the the School of Management at Sichuan Agriculture University, China. He has good research publications in the world-leading journals databases that having indexing of the Web of Science. He is currently working in several fields of economics including Energy Economics; Environmental Economics; Development Economics; Agricultural Economics; Regional Economics; Regional Rural Development and Rural Finance.

Gideon Amo-Ntim

Gideon Amo-Ntim is currently a M.A economics master student at the Department of Economics, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701 United States of America. He holds a masters degree in resource and land management and has authored more than 10 research articles with two first authored publications. He has interest in resource management, environmental economics and agricultural economic management.

References

- Ankrah Twumasi, M., Jiang, Y., Asante, D., Addai, B., Akuamoah-Boateng, S., & Fosu, P. (2021). Internet use and farm households food and nutrition security nexus: The case of rural Ghana. Technology in Society, 65(January), 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101592

- Annim, S. K., Dasmani, I., & Armah, M. (2011). Does access and use of financial Service smoothen household food consumption? MPRA (May 2014), 1–25.

- Argaw, G., Shibru, A., & Zemedu, A. (2017). Analysis of the impact of credit on smallholder farmers’ income, expenditure and asset holding in Edja District, Guraghe Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia _ tariku tagesse - academia. Journal of Poverty, Investment and Development, 35(6), 43–15.

- Asif, M., Xuhui, W., Nasiri, A., & Ayyub, S. (2017). Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Quality and Preference, 63(January), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.08.006

- Atakora, A. (2016). Measuring the effectiveness of financial literacy programs in Ghana. International Journal of Management and Business Research, 3(2), 135–148.

- Babatunde, R. O., & Qaim, M. (2010). Impact of off-farm income on food security and nutrition in Nigeria. Food Policy, 35(4), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.01.006

- Bryła, P. (2016). Organic food consumption in Poland: Motives and barriers. Appetite, 105(October), 737–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.012

- Bukari, C., Peprah, J. A., Ayifah, R. N. Y., & Annim, S. K. (2021). Effects of credit ‘plus’ on poverty reduction in Ghana. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(2), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1797689

- Burgess, S., Dudbridge, F., & Thompson, S. G. (2016). Combining information on multiple instrumental variables in Mendelian randomization: Comparison of allele score and summarized data methods. Statistics in Medicine, 35(11), 1880–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6835

- Dedehouanou, S. F. A., Araar, A., Ousseini, A., Harouna, A. L., & Jabir, M. (2018). Spillovers from off-farm self-employment opportunities in rural Niger. World Development, 105(3), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.005

- De Lorenzo, A., Noce, A., Bigioni, M., Calabrese, V., Della Rocca, D., Daniele, N., Tozzo, C., & Renzo, L. (2010). The effects of Italian Mediterranean Organic Diet (IMOD) on health status. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 16(7), 814–824. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161210790883561

- Démurger, S., & Wang, X. (2016). Remittances and expenditure patterns of the left behinds in rural China. China Economic Review, 37, 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2015.12.002

- Deng, X., Xu, D., Qi, Y., & Zeng, M. (2018). Labor off-farm employment and cropland abandonment in rural China: Spatial distribution and empirical analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091808

- DiDaniele, N., DiRenzo, L., Noce, A., Iacopino, L., Ferraro, P. M., Rizzo, M., Sarlo, F., Domino, E., & De Lorenzo, A. (2014). Effects of Italian Mediterranean organic diet vs. low-protein diet in nephropathic patients according to MTHFR genotypes. Journal of Nephrology, 27(5), 529–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-014-0067-y

- Dzanku, F. M. (2015). Household welfare effects of agricultural productivity: A multidimensional perspective from Ghana. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(9), 1139–1154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1010153

- FiBL. (2021). The World of organic agriculture, 2021.

- Foster, G., & Kalenkoski, C. M. (2013). Tobit or OLS? An empirical evaluation under different diary window lengths. Applied Economics, 45(20), 2994–3010. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2012.690852

- Ghali, Z. Z. (2020). Effect of utilitarian and hedonic values on consumer willingness to buy and to pay for organic olive oil in Tunisia. British Food Journal, 122(4), 1013–1026. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-06-2019-0414

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2018, April) Statistics for development and progress provisional 2017 annual gross domestic product

- Goldsmith, R. E., Flynn, L. R., & Kim, D. (2010). Status consumption and price sensitivity. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 18(4), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679180402

- Gundala, R. R., Nawaz, N., Harindranath, R. M., Boobalan, K., & Gajenderan, V. K. (2022). Does gender moderate the purchase intention of organic foods? Theory of reasoned action. Heliyon, 8(9), e10478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10478

- Hercberg, S., Castetbon, K., Czernichow, S., Malon, A., Mejean, C., Kesse, E., Touvier, M., & Galan, P. (2010). The nutrinet-santé study: A web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-242

- Hurtado-Barroso, S., Tresserra-Rimbau, A., Vallverdú-Queralt, A., & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. (2019). Organic food and the impact on human health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 59(4), 704–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1394815

- Hussain, A., & Thapa, G. B. (2016). Fungibility of smallholder agricultural credit: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. European Journal of Development Research, 28(5), 826–846. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2015.55

- Impiglia, A., & Lewis, P. (2019). Combatting food insecurity and rural poverty through enhancing small-scale family farming in the near East and North Africa. New Medit, 18(1), 109–112. https://doi.org/10.30682/nm1901n

- Issahaku, G., & Abdulai, A. (2020). Can farm households improve food and nutrition security through adoption of climate-smart practices? Empirical evidence from Northern Ghana. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 42(3), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppz002

- Johansson, E., Hussain, A., Kuktaite, R., Andersson, S. C., & Olsson, M. E. (2014). Contribution of organically grown crops to human health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(4), 3870–3893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110403870

- Juhler, R. K., Larsen, S. B., Meyer, O., Jensen, N. D., Spanò, M., Giwercman, A., & Bonde, J. P. (1999). Human semen quality in relation to dietary pesticide exposure and organic diet. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 37(3), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002449900533

- Kapuge, K. D. L. R. (2016). Determinants of organic food buying behavior: Special reference to organic food purchase intention of Sri Lankan customers. Procedia Food Science, 6(1), 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profoo.2016.02.060

- Keraita, B., & Drechsel, P. (2015). Consumer perceptions of fruit and vegetable quality: Certification and other options for safeguarding public health in West Africa. IWMI Working Papers.

- Kuwornu, J. K. M., Osei, E., Osei-Asare, Y. B., & Porgo, M. (2018). Off-farm work and food security status of farming households in Ghana. Development in Practice, 28(6), 724–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1476466

- Liu, K., Lan, Y., & Li, W. (2019). Behavior-based pricing between organic and general food enterprises. British Food Journal, 122(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-08-2018-0500

- Ma, W., Abdulai, A., & Ma, C. (2018). The effects of off-farm work on fertilizer and pesticide expenditures in China. Review of Development Economics, 22(2), 573–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12354

- Ma, W., Grafton, R. Q., & Renwick, A. (2020). Smartphone use and income growth in rural China: Empirical results and policy implications. Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 713–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-018-9323-x

- Ma, W., Nie, P., Zhang, P., & Renwick, A. (2020). Impact of internet use on economic well‐being of rural households: Evidence from China. Review of Development Economics, 24(2), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12645

- Ma, W., Renwick, A., Nie, P., Tang, J., & Cai, R. (2018). Off-farm work, smartphone use and household income: Evidence from rural China. China Economic Review, 52(December), 80–94. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2018.06.002

- Marian, L., Chrysochou, P., Krystallis, A., & Thøgersen, J. (2014). The role of price as a product attribute in the organic food context: An exploration based on actual purchase data. Food Quality and Preference, 37, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.05.001

- Ma, W., Zhou, X., & Renwick, A. (2019). Impact of off-farm income on household energy expenditures in China: Implications for rural energy transition. Energy Policy, 127(December), 248–258. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.12.016

- Mishra, A. K., Mottaleb, K. A., & Mohanty, S. (2015). Impact of off-farm income on food expenditures in rural Bangladesh: An unconditional quantile regression approach. Agricultural Economics (United Kingdom), 46(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12146

- Mohammed, A. A. (2020). What motivates consumers to purchase organic food in an emerging market? An empirical study from Saudi Arabia. British Food Journal, 123(5), 1758–1775. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-2020-0599

- Owusu, V., Abdulai, A., & Abdul-Rahman, S. (2011). Non-farm work and food security among farm households in Northern Ghana. Food Policy, 36(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.09.002

- Owusu, V., & Anifori, M. O. (2013). Consumer willingness to pay a premium for organic fruit and vegetable in Ghana. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 16(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.22004/AG.ECON.144649

- Pfeiffer, L., López-Feldman, A., & Taylor, J. E. (2009). Is off-farm income reforming the farm? Evidence from Mexico. Agricultural Economics, 40(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00365.x

- Rahman, A., & Mishra, S. (2020). Does non-farm income affect food security? Evidence from India. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(6), 1190–1209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1640871

- Raynolds, L. T. (2004). The globalization of organic agro-food networks. World Development.

- Seng, K. (2015). The effects of nonfarm activities on farm households’ food consumption in rural Cambodia. Development Studies Research, 2(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2015.1098554

- Siaw, A., Jiang, Y., Twumasi, M. A., & Agbenyo, W. (2020). The impact of internet use on income: The case of rural Ghana. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083255

- Torjusen, H., Brantsæter, A. L., Haugen, M., Alexander, J., Bakketeig, L. S., Lieblein, G., Stigum, H., Næs, T., Swartz, J., Holmboe-Ottesen, G., Roos, G., & Meltzer, H. M. (2014). Reduced risk of pre-eclampsia with organic vegetable consumption: Results from the prospective Norwegian mother and child cohort study. British Medical Journal Open, 4(9), e006143–e006143. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006143

- Ueasangkomsate, P., & Santiteerakul, S. (2016). A study of consumers’ attitudes and intention to buy organic foods for sustainability. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 34, 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2016.04.037

- Wang, X., Pacho, F., Liu, J., & Kajungiro, R. (2019). Factors influencing organic food purchase intention in Tanzania and Kenya and the moderating role of knowledge. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010209

- Willer, H., & Lernoud, J. (2016). The World of organic agriculture 2016: Statistics and emerging trends. FIBL & IFOAM - Organics International.

- Wilson, C., & Tisdellt, C. A. (2002). OLS and Tobit estimates: When is substitution defensible operationally? (Economic theory, applications and issues (Working paper No. 15)).

- Woldeyohanes, T., Heckelei, T., & Surry, Y. (2017). Effect of off-farm income on smallholder commercialization: Panel evidence from rural households in Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 48(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12327

- Xu, D., Deng, X., Guo, S., & Liu, S. (2019). Labor migration and farmland abandonment in rural China: Empirical results and policy implications. Journal of Environmental Management, 232(November), 738–750. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.136

- Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2016). Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite, 96, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.017

- Zereyesus, Y. A., Embaye, W. T., Tsiboe, F., & Amanor-Boadu, V. (2017). Implications of non-farm work to vulnerability to food poverty-recent evidence from Northern Ghana. World Development, 91, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.015

Appendix

Table A1. Pearson correlation analysis of the selected IV