?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study aimed to comprehensively investigate the key factors influencing farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in the unique context of Sikkim. It extends the theory of planned behavior by incorporating environmental consciousness and knowledge as additional independent variables. It examines their impact on farmers’ intentions, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. A sample of 384 farmers from two districts of Sikkim was selected using a multistage sampling technique. The collected data were analyzed using Smart PLS SEM 4 software, employing path analysis to determine the direct and indirect effects of the independent variables on farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. Environmental consciousness strongly influenced farmers’ attitudes and subjective norms. Knowledge also significantly affects farmers’ perceived behavioral control. Notably, an impactful link was found between environmental consciousness and the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. The findings provide valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners. Targeted interventions and educational programs should be developed to enhance farmers’ environmental consciousness and knowledge, thereby promoting the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim. This study extends the theory of planned behavior by incorporating environmental consciousness and knowledge as additional determinants. It contributes to understanding the behavioral factors influencing farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable agriculture and their interrelationships within the context of Sikkim. This study comprehensively investigated the determinants of farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim. It contributes to the existing literature by incorporating environmental consciousness and knowledge into the theory of planned behavior, providing a nuanced understanding of the adoption process.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Our paper takes you on a journey into the vibrant world of sustainable agriculture, unraveling the secrets behind its transformative power. In a captivating study centered on Sikkim, we unveil the behavioral factors that sway farmers’ intentions to embrace sustainable practices, shedding light on the path towards a greener, more secure future. Join us in unraveling the story of sustainable agriculture, where every decision holds the promise of a healthier planet and more resilient communities.

1. Introduction

With its emphasis on environmental stewardship and long-term viability, sustainable agriculture has emerged as a critical solution to address the global challenges of food security and ecological sustainability. Adopting sustainable agricultural practices offers promising avenues for mitigating the negative impacts of conventional farming systems, such as soil erosion, water pollution, and biodiversity loss. Recognizing the urgency of sustainable development, various regions worldwide have committed to transforming their agricultural practices to align themselves with sustainability goals (Durán Gabela et al., Citation2022; Laurett et al., Citation2021; Šūmane et al., Citation2016; Zecca & Rastorgueva, Citation2017).

Sikkim, a small and picturesque state in northeastern India, has gained significant attention for its progressive approach to sustainability. In 2016, Sikkim was the first state in the world to achieve 100% organic farming (Meek & Anderson, Citation2020). This remarkable accomplishment has made Sikkim a noteworthy case study for investigating the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. By examining the factors influencing farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim, valuable insights can be gained to inform policy interventions and support the broader adoption of sustainable agriculture in similar contexts (Choubey, Citation2016; Upadhyay & Rai, Citation2022).

Sustainable agriculture has emerged as a crucial approach to tackling environmental issues and ensuring the long-term viability of agricultural systems. Comprehending the underlying reasons that drive farmers’ intentions to adopt such practices is pivotal for effective and widespread implementation. This research delves into the intricate fabric of Sikkim’s agricultural landscape to shed light on the determinants shaping farmers’ inclinations toward sustainable agriculture adoption (Choubey, Citation2016; Meek & Anderson, Citation2020; Upadhyay & Rai, Citation2022).

The study builds upon the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which explains how intentions shape behavior through attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Additionally, the study expands the TPB by introducing environmental consciousness and knowledge as variables. Environmental consciousness reflects awareness and concern for the environment, while knowledge pertains to understanding sustainable farming practices. By incorporating these, the study offers a holistic perspective on factors influencing the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture (Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2011, Citation2020; Bosnjak et al., Citation2020).

The significance of this research lies in its focus on a region-specific context like Sikkim, where empirical investigations regarding the intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices are limited. Considering the existing body of work, it is evident that uncovering the intricacies of farmers’ intentions in a region like Sikkim can offer invaluable insights. As the global focus on sustainable agriculture intensifies, understanding the local dynamics that motivate farmers to adopt such practices becomes imperative. This research strives to fill this crucial gap by shedding light on the factors that sway farmers’ intentions in favor of sustainable agriculture. In doing so, we aim to contribute to the existing literature, providing a context-specific lens that enhances the comprehensiveness of the understanding surrounding sustainable agricultural adoption (Šūmane et al., Citation2016; Zecca & Rastorgueva, Citation2017).

The subsequent sections of this paper will delve into a literature review, the theoretical framework of the study, the research objectives and hypotheses, the methodological approach, empirical analysis, and implications for policy and practice. In doing so, we aim to provide a holistic perspective on the factors underpinning farmers’ intentions to embrace sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim.

2. Literature review

The literature review section provides a comprehensive overview of the knowledge related to sustainable agriculture adoption and the determinants influencing farmers’ intentions to adopt such practices. This section is the foundation for understanding the study’s theoretical underpinnings and conceptual framework.

2.1. Sustainable agriculture adoption: A global imperative

Sustainable agriculture has gained significant prominence as a critical solution to address the global challenges of food security, ecological sustainability, and environmental degradation. The conventional agricultural practices that have prevailed over the years often lead to soil erosion, water pollution, and loss of biodiversity (Durán Gabela et al., Citation2022; Laurett et al., Citation2021; Šūmane et al., Citation2016; Zecca & Rastorgueva, Citation2017). As the urgency for sustainable development intensifies, regions worldwide recognize the need to transition their agricultural systems to more sustainable alternatives (Choubey, Citation2016; Upadhyay & Rai, Citation2022).

2.2. The theory of planned behavior: A theoretical lens

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), developed by Ajzen in 1985, offers a robust theoretical framework for understanding the intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. The TPB posits that intention is a central determinant of behavior and is influenced by three key factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude refers to an individual’s evaluation of behavior, subjective norms capture social pressures, and perceived behavioral control reflects the perceived ease of executing a behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2011). This framework provides a structured approach for analyzing the factors driving or hindering the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices.

2.3. Enhancing the TPB framework: Environmental consciousness and knowledge

In addition to the TPB framework, this study integrates two crucial independent variables: environmental consciousness and knowledge. Environmental consciousness denotes individuals’ awareness of and concern for environmental issues. At the same time, knowledge pertains to understanding information about sustainable farming practices. By incorporating these variables, the study aims to capture the influence of individual characteristics and environmental awareness on the intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices (Ajzen, Citation2020; Bosnjak et al., Citation2020).

2.4. Research gap and rationale

Despite the growing importance of sustainable agriculture, empirical research examining the intention to adopt such practices in specific geographical contexts, such as Sikkim, remains limited. This study addresses this gap by comprehensively investigating the factors influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture in Sikkim. By collecting primary data from a diverse sample of farmers, the study provides empirical evidence that enhances the understanding of the intricate dynamics underlying sustainable agriculture adoption decisions (Choubey, Citation2016; Upadhyay & Rai, Citation2022).

2.5. Theoretical and practical implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for both academia and practice. Academically, this study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on sustainable agriculture by shedding light on the multifaceted factors that drive or hinder the adoption of such practices. Integrating the TPB framework with environmental consciousness and knowledge adds depth and comprehensiveness to the existing literature. The insights gained from this study can inform policymakers, agricultural extension agencies, and stakeholders in devising effective strategies to promote sustainable agriculture in Sikkim and beyond (Imani et al., Citation2021; Tama et al., Citation2021).

3. Research questions and hypotheses development

This section outlines the central research question and hypotheses that guide the investigation of the factors influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim. Formulating research questions and hypotheses provides a structured framework for systematically exploring and testing the relationships among variables within the theoretical context.

3.1. Research question

The primary research question that underpins this study is:

How do attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, environmental consciousness, and knowledge impact the intention of farmers in Sikkim to adopt sustainable agriculture?

This overarching research question seeks to unravel the complex interplay of variables contributing to farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in the unique context of Sikkim.

3.2. Research objectives

To examine the individual contributions of attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, environmental consciousness, and knowledge of farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture in Sikkim.

To explore the combined influence of these factors on farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices and understand their interrelationships within the context of Sikkim.

3.3. Hypotheses development

Building upon the research question, hypotheses are formulated to establish specific relationships among the variables. These hypotheses guide the data collection process and subsequent statistical analyses to provide empirical insights into the factors influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. The hypotheses are categorized into direct effects and mediation relationships. Figure shows the conceptual framework with hypotheses.

3.3.1. Attitude

Attitude is a crucial determinant of farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. Positive attitudes towards sustainable farming practices are associated with beliefs about environmental benefits, resource efficiency, and long-term farm productivity gains. Farmers with more positive attitudes toward sustainable practices were more likely to adopt them (Azman et al., Citation2013; Liao et al., Citation2022).

3.3.2. Direct effect hypothesis

H1:

Attitude (AT) influences the intention (IN) to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

3.3.3. Attitude as mediator

H15:

Attitude (AT) mediates the relationship between Knowledge (KN) and the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H16:

Attitude (AT) mediates the influence of Environmental Consciousness (EC) on the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H17:

Attitude (AT) mediates the impact of Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) on the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H18:

Attitude (AT) mediates the relationship between Subjective Norms (SN) and the Intention to Adopt (IN).

3.3.4. Subjective norms

Subjective norms refer to social pressures and expectations that influence an individual’s intention to adopt a particular behavior. Subjective norms in sustainable agriculture can arise from family members, peers, community leaders, and agricultural extension agents. Studies have shown that strong social support and positive feedback from social networks significantly influence farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable farming practices (Bagheri et al., Citation2021b; Faisal et al., Citation2020; Sarma, Citation2022; Tama et al., Citation2021).

3.3.5. Direct effects hypotheses

H13:

Subjective norms (SN) influence attitude (AT).

H14:

Subjective norms (SN) impact the intention (IN) to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

3.3.6. Subjective Norms (SN) as mediator

H23:

Subjective Norms (SN) mediate the influence of Environmental Consciousness (EC) on the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H24:

Subjective Norms (SN) mediate the influence of Environmental Consciousness (EC) on Attitude (AT).

H25:

Subjective Norms (SN) mediate the impact of knowledge on the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H26:

Subjective Norms (SN) mediate the impact of Knowledge on Attitude (AT).

3.3.7. Perceived behavioral control

Perceived behavioral control reflects an individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty of executing a specific behavior. In sustainable agriculture, perceived behavioral control encompasses farmers’ beliefs about overcoming barriers and constraints related to sustainable farming practices. Factors such as access to resources, availability of technical assistance, and knowledge of sustainable techniques influence farmers’ perceptions of their control over adopting sustainable practices. Hence, higher perceived behavioral control is expected to influence Sikkim’s intention to adopt sustainable agriculture positively (Bagheri et al., Citation2021a; Baydur et al., Citation2023; Imani et al., Citation2021; Savari & Gharechaee, Citation2020).

3.3.8. Direct effects hypotheses

H11:

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) influences attitude (AT).

H12:

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) impacts the intention (IN) to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

3.3.9. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) as mediator

H19:

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) mediates the influence of Environmental Consciousness (EC) on the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H20:

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) mediates the influence of Environmental Consciousness (EC) on Attitude (AT).

H21:

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) mediates the effect of Knowledge (KN) on the Intention to Adopt (IN).

H22:

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) mediates the effect of Knowledge (KN) on Attitude (AT).

3.3.10. Environmental consciousness

Environmental consciousness refers to an individual’s awareness of and concern for environmental issues, including recognizing the adverse impacts of conventional farming practices and the importance of adopting sustainable alternatives. Studies have indicated that farmers with higher levels of environmental consciousness are more likely to exhibit positive intentions toward sustainable agriculture (Dong et al., Citation2023; Lazarenko, Citation2022; Ma et al., Citation2021; Pestisha & Bai, Citation2023; Qiao et al., Citation2022; Sarwar & Alsaggaf, Citation2020).

3.3.11. Direct effects hypotheses

H2:

Environmental consciousness (EC) influences attitude (AT).

H3:

Environmental consciousness (EC) affects the intention (IN) to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

H4:

Environmental consciousness (EC) influences perceived behavioral control (PBC).

H5:

Environmental consciousness (EC) impacts subjective norms (SN).

3.3.12. Environmental Consciousness (EC) as mediator

H27:

Environmental Consciousness (EC) mediates the impact of Knowledge (KN) on the intention to adopt (IN).

H28:

Environmental Consciousness (EC) mediates the impact of Knowledge (KN) on Attitude (AT).

H29:

Environmental Consciousness (EC) mediates the effect of Knowledge (KN) on Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC).

H30:

Environmental Consciousness (EC) mediates the impact of Knowledge on Subjective Norms.

3.3.13. Knowledge

Knowledge of sustainable farming practices is crucial to farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. The level of understanding of and information on sustainable techniques, benefits, and outcomes can significantly influence farmers’ decision-making processes. Studies have consistently shown that farmers with higher knowledge levels are more likely to have positive intentions toward sustainable agriculture (Feliciano, Citation2022, Imani et al., Citation2021; Ma et al., Citation2021; Pestisha & Bai, Citation2023).

3.3.14. Direct effects hypotheses

H6: Knowledge influences attitudes.

H7:

Knowledge affects the intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

H8:

Knowledge shapes perceived behavioral control.

H9: Knowledge impacts subjective norms.

H10: Knowledge raises environmental consciousness.

The formulation of these research questions and hypotheses provides a comprehensive framework for investigating the behavioral factors influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim. By systematically testing these relationships, this study aims to contribute valuable insights to both academia and practice in the realm of sustainable agriculture and adoption behavior.

4. Methods

4.1. Study location

This study is centered in Sikkim, India, situated at Latitude 27.5330° N and Longitude 88.5122° E. Sikkim’s unique geography, culture, and agriculture make it an ideal context for investigating the factors driving farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable practices. Notably, Sikkim achieved global recognition in 2016 for becoming the first state to achieve 100% organic farming status (Meek & Anderson, Citation2020). This achievement provides a strong foundation for examining motivations behind sustainable agricultural practices. The study focuses on understanding the behavioral drivers prompting farmers in Sikkim to embrace sustainability, with implications for similar regions.

4.2. Research design and philosophy

The research design employed in this study adheres to a quantitative approach, which allows for systematic examination and analysis of the relationships among variables. This approach aligns well with the pragmatism philosophy, which emphasizes the practical application of research to address real-world issues. Pragmatism recognizes the value of theory and practice, stressing the importance of research that offers actionable insights. By employing a structured questionnaire to collect data, we aim to quantify the various constructs and variables of interest and contribute to the practical understanding of sustainable agricultural adoption (Creswell, Citation2014).

4.3. Sampling procedure

A meticulous multistage sampling technique was employed to ensure a comprehensive representation of farmers in the Sikkim region. The sampling process encompassed two distinct stages: district selection and village selection.

4.3.1. District selection

Two strategically chosen districts, West and South, were selected based on their distinct geographic and socioeconomic characteristics within the Sikkim state. This deliberate choice aimed to capture the diverse spectrum of behavioral factors in sustainable agricultural adoption practices prevalent across different contexts.

4.3.2. Village selection

Within the two selected districts, eight villages were chosen as the second stage of the sampling process using a convenience sampling technique. The selection criterion was based on the presence of key informants with a comprehensive understanding of local agricultural practices and substantial influence over the adoption of sustainable agriculture. These informants comprised agricultural extension officers and village leaders, whose insights were essential for identifying context-specific factors influencing farmers’ intentions.

4.3.3. Farmer selection

Individual farmers within each selected village were thoughtfully chosen using a robust random sampling approach. This method was meticulously employed to ensure an unbiased representation encompassing diverse backgrounds and a wide range of farming systems. The determination of the sample size for this study was conducted using Cochran’s formula, tailored for a finite population:

Where n = sample size

Z = Z value (used 1.96 for 95 % confidence level)

p = an estimate of the proportion of people falling into the group of population in which

the researcher is interested (0.50 used for sample size need)

c2 = the proportion of error we are prepared to accept

Therefore, n = [(1.96)2 * (0.5) * (0.5)]/(0.05)2 = 384

Consequently, considering a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error set at 5%, the calculated sample size amounted to 384. This comprehensive approach ensures that our study’s findings are robust and reflective of the diverse agricultural landscape within Sikkim.

4.4. Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were also considered in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, emphasizing voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the anonymity of the survey. The relevant institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol to ensure the research followed ethical guidelines and standards.

4.5. Questionnaire development

Our structured questionnaire was constructed meticulously and aimed at capturing robust and validated measures of critical constructs. These constructs encompassed farmers’ attitudes, environmental consciousness, intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices, knowledge about these practices, perceived behavioral control, and the influence of subjective norms.

To ensure the reliability and validity of our measures, we drew upon well-established scales from existing literature:

Attitude: The scale developed by Tama et al. (Citation2021) was adopted to measure farmers’ attitudes toward sustainable agriculture. This scale’s robust psychometric properties and adaptability to diverse cultural and agricultural contexts made it an ideal choice.

Environmental Consciousness: We employed the scale Gericke et al. (Citation2018) created to effectively capture farmers’ depth of environmental awareness and their perceived role in environmental conservation through sustainable agricultural practices.

Intention to Adopt SAP: Recognizing the centrality of intention, we utilized the validated scale by Tama et al. (Citation2021), specifically designed to measure farmers’ willingness and intent to adopt sustainable practices.

Knowledge: Our measure of knowledge, intended to gauge farmers’ understanding of sustainable agricultural practices and their associated benefits, was derived from Tama et al. (Citation2021), offering insights into the breadth and depth of respondents’ knowledge.

Perceived Behavioral Control: This construct incorporated items from the scales of Nguyen et al. (Citation2021) and Tama et al. (Citation2021), providing a comprehensive view of farmers’ perceived ease or challenges in adopting sustainable agricultural practices, considering internal and external constraints.

Subjective Norms: The influence of societal and peer perceptions on individual behavior was captured using the scale developed by Nguyen et al. (Citation2021), which was pivotal in understanding societal pressures that influence farmers’ intentions, especially within Sikkim’s closely-knit communities.

This foundation in established scales ensured consistency with prior research while adapting to Sikkim’s unique farming community. It facilitated comparability with existing literature, as evident in the later discussion section.

Furthermore, we conducted a pilot study involving 50 respondents to refine the questionnaire. This preliminary study allowed us to pretest the questionnaire, ensuring clarity, relevance, and cultural sensitivity.

4.6. Data collection

Primary data collection was executed through structured questionnaires administered to the selected farmers. Rigorous training of research assistants ensured uniform administration and effective handling of participant queries.

To mitigate biases, we employed two strategies:

Anonymity and Confidentiality: Participants were guaranteed confidentiality, and data collection forms were designed to prevent the identification of individual respondents. This approach reduced social desirability bias.

Pilot Study: A pilot study involving 50 respondents allowed us to pretest the questionnaire for clarity, relevance, and cultural appropriateness.

The methodology employed in this study aimed to provide a representative sample of farmers from different districts and villages in Sikkim, allowing for a comprehensive analysis of the factors influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture. The utilization of SMART PLS SEM 4 facilitated a rigorous analysis of the data, enhancing the reliability and validity of the study findings and contributing to the overall quality and credibility of the research.

4.7. Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using statistical techniques. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the farmers and the key variables under investigation. The structural equation Modeling (SEM) approach was used for data analysis, specifically the SMART PLS SEM 4 software. SMART PLS-SEM is a powerful tool that assesses complex relationships and latent constructs within a model.

First, to assess the potential presence of common method bias, a Harman single-factor test was conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). The Harman single-factor analysis examined whether a single dominant factor explains a substantial amount of variance in the data, which could indicate the presence of common method bias. The results of the Harman single-factor analysis revealed that a single factor accounted for only 22% of the total variance, suggesting that common method bias was not a significant concern (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model. This step involved examining each construct’s factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). Constructs with satisfactory factor loadings (>0.7), composite reliability (>0.7), and AVE (>0.5) were considered reliable and valid for further analysis (Hair et al., Citation2017).

The structural model was assessed to determine construct relationships and test the hypotheses. The analysis involved examining path coefficients, t-values, and effect sizes. Bootstrapping was employed to determine the significance of path coefficients and estimate their confidence intervals.

Additionally, the analysis assessed goodness-of-fit measures, such as R-squared (R2) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The R2 values indicate the variance the endogenous constructs explain, whereas SRMR measures the model’s overall fit (Hair et al., Citation2017).

The use of SMART PLS SEM 4 as an analytical tool provided a comprehensive assessment of the relationships between the variables within the theoretical framework. This approach allowed us to examine the measurement and structural models, capturing constructs’ complex interactions and interdependencies.

5. Results

The data analysis conducted in this study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture in Sikkim. The results indicate significant direct and indirect effects between various constructs, shedding light on the complex relationships at play.

5.1. Descriptive statistics

The demographic characteristics of the participating farmers provide valuable insights into the social and economic aspects of the population, the distribution of resources, and their various applications. This information facilitates in identifying relevant characteristics and limitations. Table presents a comprehensive overview of the demographic characteristics of the participating farmers. The distribution of these characteristics offers valuable insights into the composition of the sample and its relevance to the study’s objectives.

Table 1. Showing demographic characteristics of participating farmers

The demographic landscape unveils intriguing insights into the agricultural community. A notable gender distribution emerges, with 68.2% (n = 262) of respondents being male and 31.8% (n = 122) being female. This distribution draws attention to the prevailing gender dynamics within agriculture, emphasizing male dominance—a phenomenon echoed in prior studies and warranting gender-sensitive strategies for sustainable agricultural progress (Baylina & Rodo-Zarate, Citation2020).

Examining age groups, the largest group is those aged 34 to 49, constituting 45.8% (n = 176), closely followed by individuals aged 50 and above, accounting for 45.1% (n = 173). This distribution hints at a mature farming populace, potentially signaling generational continuity in agricultural traditions. Such trends align with research associating age with the adoption of innovative farming practices (Handavu et al., Citation2019).

Household composition unfolds as 93.8% (n = 360) with fewer than seven members and only 6.2% (n = 24) with seven or more members. This distribution sheds light on prevalent smaller households, with implications for labor availability, a crucial factor in agricultural activities. Family labor’s vital role in farming productivity resonates with the findings (Santacoloma-Varón, Citation2015).

Shifting to education, 60.2% (n = 231) had secondary schooling, 22.7% (n = 87) had primary schooling, and 17.2% (n = 66) reached high school and beyond. Education’s connection to knowledge acquisition and decision-making underscores the importance of this distribution in deciphering hurdles and facilitators for sustainable agricultural (García et al., Citation2020; Kassie et al., Citation2013).

Farm size variance is compelling, with 81.0% (n = 311) operating plots under two hectares and 19.0% (n = 73) managing farms of two hectares or more. Farm size’s sway over resource allocation and innovation resonates, accentuating its relevance in the context of sustainable practices (Foguesatto et al., Citation2020).

Farming experience distribution reveals 12.2% (n = 47) with less than a decade’s experience, 41.4% (n = 159) within ten to fifteen years, and 46.4% (n = 178) surpassing fifteen years. This distribution hints at a spectrum of familiarity with conventional and novel practices, impacting the inclination toward sustainable methods (Handavu et al., Citation2019; Kassie et al., Citation2013).

Income distribution highlights that 70.6% (n = 271) report earnings under $2,000, whereas 29.4% (n = 113) exceed this threshold. Income’s influence on resource access and technological feasibility magnifies its role in the sustainable agricultural context (Foguesatto et al., Citation2020).

5.2. Measurement model

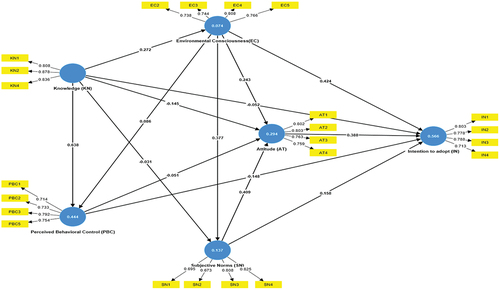

The values for the items related to constructs for loadings above 0.7, Cronbach’s alpha above 0.7, composite reliability above 0.7, and average variance extracted (AVE) above 0.5 met the threshold. Hence, all the values indicated good reliability and validity. Some items loading below 0.7 were removed from constructs of perceived behavior control item 4, knowledge item 3, and environmental consciousness item 1. Figure . Below shows the structural equation modeling with values in circles indicates the r square.

5.3. Reliability and validity

Firstly, the reliability and validity of the constructs were assessed to ensure the robustness of the measurement model. Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the measurement instrument. Validity assesses whether the instrument measures what it intends to measure.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the constructs’ internal consistency. The results indicate that all constructs exhibited satisfactory levels of internal consistency. Attitude (AT) demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.789, indicating high reliability. Environmental Consciousness (EC), intention to adopt (IN), Knowledge (KN), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and Subjective Norms (SN) also displayed strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.762, 0.772, 0.793, 0.745, and 0.742, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler et al., Citation2009).

Composite reliability was used to assess the constructs’ internal consistency and reliability. All constructs surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.7, indicating good reliability. Attitude (AT), Environmental Consciousness (EC), intention to adopt (IN), knowledge (KN), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and Subjective Norms (SN) exhibited composite reliabilities of 0.791, 0.763, 0.776, 0.799, 0.762, and 0.753, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2020; Henseler et al., Citation2009).

Convergent validity was assessed using average variance extracted (AVE), which indicates the amount of variance captured by the construct relative to measurement error. All constructs demonstrated satisfactory levels of convergent validity, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.5 for AVE. Attitude (AT), Environmental Consciousness (EC), intention to adopt (IN), knowledge (KN), Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC), and Subjective Norms (SN) exhibited AVE values of 0.612, 0.584, 0.595, 0.708, 0.560, and 0.567, respectively (Henseler et al., Citation2009).

Discriminant validity was examined using the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. The HTMT ratio assesses whether the constructs are more strongly correlated with their own items than with other constructs. The results indicated satisfactory discriminant validity, as the HTMT ratios for all the construct pairs were below the threshold of 0.9. This suggests that the constructs are distinct and measure different underlying dimensions (Hair et al., Citation2020).

In conclusion, the reliability and validity analyses confirmed the reliability of the measurement model. The constructs demonstrated strong internal consistency, reliability, and convergent and discriminant validities. These findings support the robustness of the measurement instrument and provide confidence in the accuracy of the results.

5.4. Hypothesis testing

Secondly, bootstrapping was conducted using 10,000 resamples to enhance the analysis’s robustness and test for direct and indirect effects in the model. The direct effect is presented in Table and the indirect effects (mediation) are shown in Table .

Table 2. Showing direct effect hypothesis with t statistics and p values

Table 3. Showing mediation hypothesis with t statistics and p values

Regarding direct effects, the findings demonstrate that attitude (AT) has a significantly favorable influence on the intention to adopt (IN) sustainable agriculture (path coefficient = 0.388, p < 0.001). The finding indicates that farmers with more positive attitudes towards sustainable practices are more likely to express a stronger intention to adopt them. Additionally, environmental consciousness (EC) also exerted a significant direct influence on both attitude (path coefficient = 0.243, p < 0.001) and intention to adopt (path coefficient = 0.424, p < 0.001). Farmers with higher levels of environmental consciousness tend to develop more positive attitudes and stronger intentions to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) shows a negative direct effect on attitude (path coefficient = −0.051, p > 0.05) and intention to adopt (path coefficient = −0.148, p < 0.01). The results suggest that when farmers perceive lower control over their ability to adopt sustainable practices, they can negatively influence their attitudes and intentions. However, it is worth noting that the direct effect of perceived behavioral control on attitude was not statistically significant.

Subjective norms (SN) also played a significant role in shaping attitudes (path coefficient = 0.409, p < 0.001) and the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture (path coefficient = 0.158, p < 0.001). Farmers who perceive stronger social norms to support sustainable practices are more likely to develop positive attitudes and intentions.

Moreover, knowledge (KN) had a significant direct influence on attitude (path coefficient = −0.145, p < 0.05). The finding suggests that farmers with higher levels of knowledge are more likely to develop positive attitudes toward sustainable agriculture. However, the direct effect of knowledge on the intention to adopt was not statistically significant.

In addition to direct effects, this study explored the specific indirect effects between the constructs. These indirect effects provide insights into the mediating pathways through which the relationships between variables occur. The statistical analysis revealed the presence or absence of indirect effects between the constructs. Specifically, environmental consciousness (EC) was found to mediate the relationship between knowledge (KN) and subjective norms (SN) on the intention to adopt (IN). It also mediates the relationship between knowledge (KN) and intention to adopt (IN). Attitude (AT) was identified as a mediator between environmental consciousness (EC) and intention to adopt (IN).

The results indicated that knowledge indirectly influenced the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture through the mediating role of environmental consciousness (path coefficient = 0.115, p < 0.001), suggesting that farmers with higher knowledge levels are more likely to develop greater environmental consciousness, positively influencing their intention to adopt sustainable practices.

Environmental consciousness also indirectly influenced the intention to adopt sustainable agriculture through subjective norms (path coefficient = 0.060, p < 0.001). Farmers with higher levels of environmental consciousness perceive stronger subjective norms related to sustainable agriculture, which positively influence their intention to adopt such practices. Furthermore, the indirect pathway from environmental consciousness to attitude to intention to adopt is significant (path coefficient = 0.094, p < 0.001), suggesting that farmers with higher levels of environmental consciousness are more likely to develop positive attitudes, leading to increased intention to adopt sustainable practices.

However, the study did not find significant indirect effects between knowledge and environmental consciousness on perceived behavioral control or between environmental consciousness and perceived behavioral control on attitudes. These pathways did not significantly influence attitude formation or intention to adopt sustainable agriculture.

5.5. Evaluating model fit and explanatory power

The model’s effectiveness in explaining adoption intentions was assessed through the R-square value for the endogenous variable, “Intention to Adopt (IN).” With an R-square value of 0.566, the model accounted for approximately 56.6% of the variability in farmers’ adoption intentions. This substantial proportion underscores the model’s capacity to shed light on the factors shaping farmers’ decisions to embrace sustainable agricultural practices.

While acknowledging the existence of other unmeasured variables contributing to the unexplained variance, the achieved R-square value demonstrates the model’s significance in unraveling the intricate dynamics of sustainable agricultural adoption intentions. The model is a valuable tool for understanding how environmental consciousness, knowledge, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms collectively contribute to forming farmers’ intentions.

The model’s overall fit was further evaluated using the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values. The estimated model exhibited an SRMR value of 0.066, slightly higher than the SRMR value of 0.065 in the saturated model. This marginal difference suggests that despite the model’s complexity, it maintained a relatively close fit to the more saturated model. Generally, SRMR values below 0.08 are deemed acceptable (Hair et al., Citation2017).

In summary, the R-square values offer insights into the model’s ability to explain variations in adoption intentions across different constructs. Additionally, the SRMR values indicate how well the estimated model aligns with the saturated model. These evaluations collectively enrich our understanding of the model’s goodness-of-fit, underlining its significance in capturing the intricate interplay among the examined variables and their roles in driving sustainable agricultural adoption intentions.

5.6. Important Performance Map Analysis (IPMA)

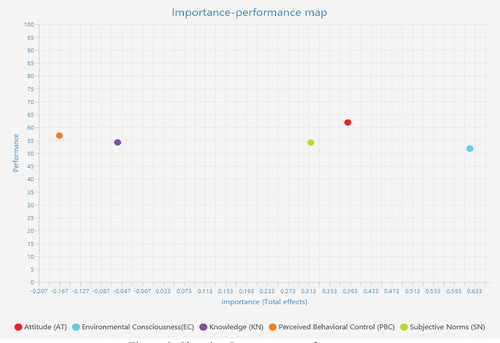

The Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) results in Figure provide valuable insights into the factors influencing Sikkim’s Intention to Adopt (IN) sustainable agricultural practices.

5.6.1. Total effects on Intention to Adopt (IN)

Attitude (AT): Attitude has a positive total effect of 0.388 on the intention to adopt sustainable practices. This suggests that a favorable attitude towards sustainable agriculture positively influences farmers’ intention to adopt such practices.

Environmental Consciousness (EC): Environmental consciousness exerts the most substantial positive total effect of 0.623 on the intention to adopt, implying a strong sense of environmental responsibility, and awareness drives farmers’ intention to embrace sustainable agriculture.

Knowledge (KN) With a negative total effect of −0.056, knowledge seems to have a weaker influence on the intention to adopt, suggesting that knowledge alone might not be a strong determinant of adoption intention.

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC): Perceived behavioral control has a negative total effect of −0.168 on the intention to adopt, implying that factors affecting farmers’ sense of control over adopting sustainable practices might somewhat hinder their intention.

Subjective Norms (SN): Subjective norms have a positive total effect of 0.317 on the intention to adopt, indicating that societal influences and perceived expectations from others play a role in shaping farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable practices.

5.6.2. Construct Performances on Intention to Adopt (IN)

Attitude (AT): The attitude performance is rated at 61.908, suggesting that farmers generally have a favorable attitude towards adopting sustainable practices, but there is room for improvement.

Environmental Consciousness (EC): Environmental consciousness has a performance score of 51.774, indicating a relatively high level of environmental awareness among farmers.

Knowledge (KN): Knowledge performance is rated at 54.179, suggesting that farmers have a moderate knowledge level about sustainable agriculture.

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC): Perceived behavioral control has a performance score of 56.850, indicating that farmers feel moderately confident in their ability to adopt sustainable practices.

Subjective Norms (SN): Subjective norms have a performance score of 54.130, suggesting that farmers perceive moderate societal expectations regarding adopting sustainable practices.

In summary, the IPMA results highlight the significance of environmental consciousness, subjective norms, and attitude in influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices in Sikkim. While knowledge and perceived behavioral control also play a role, they might negatively impact adoption intention. The construct performances indicate that while certain aspects, such as environmental consciousness and subjective norms, are relatively strong, there is still room for improvement in other areas. These findings provide actionable insights for developing targeted interventions to enhance the adoption of sustainable practices among farmers in Sikkim.

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications and insights

The findings from this study hold profound implications for advancing sustainable agriculture in Sikkim. Enhancing farmers’ knowledge regarding sustainable practices and elevating their environmental consciousness emerge as pivotal strategies. It is imperative to nurture positive attitudes toward sustainable agriculture and foster robust subjective norms that endorse its adoption. Additionally, interventions must address the factors shaping perceived behavioral control, aiming to bolster farmers’ confidence and perceived control over integrating sustainable practices.

The analysis accentuates the influential roles of knowledge and environmental consciousness in shaping attitudes and intentions regarding sustainable agriculture. It becomes evident that farmers equipped with greater knowledge and heightened environmental consciousness tend to develop more favorable attitudes and intentions, crucial drivers for promoting sustainable farming practices. These insights offer invaluable guidance to policymakers and agricultural practitioners striving to bolster sustainable agricultural development in Sikkim.

The mediation role of environmental consciousness (EC) in connecting knowledge (KN) and subjective norms (SN) with the intention to adopt (IN) underscores the significance of individuals’ environmental awareness in shaping their perception of social norms. A higher level of knowledge about environmental matters is observed to deepen the internalization of subjective norms related to pro-environmental behaviors. This emphasizes the role of environmental education and awareness campaigns in fostering sustainable behaviors by molding individuals’ understanding of societal expectations.

Furthermore, the mediating impact of environmental consciousness (EC) in the relationship between knowledge (KN) and intention to adopt (IN) highlights the pivotal role of an individual’s environmental concern in bridging the gap between knowledge and behavioral intentions. Thereby suggests that knowledge about environmental issues might not be enough to drive sustainable actions. Instead, a fundamental environmental consciousness, rooted in personal values, beliefs, and an emotional connection to nature, is integral in translating knowledge into actionable intentions. Therefore, initiatives to promote sustainability should target the enrichment of environmental consciousness while providing substantive information.

The identification of attitude (AT) as a mediator between environmental consciousness (EC) and intention to adopt (IN) emphasizes the role of an individual’s overall evaluation of environmentally friendly behaviors in shaping their behavioral intentions. Environmental consciousness significantly influences individuals’ attitudes toward sustainability. This finding underscores the importance of nurturing a positive and encouraging attitude toward sustainable actions, achieved by fostering a sense of environmental consciousness among individuals. Strategies such as highlighting the benefits of pro-environmental behaviors and addressing potential barriers can mold attitudes and propel intentions toward adopting sustainable practices.

The mediating effects offer valuable insights into the intricate interplay of knowledge, environmental consciousness, attitude, and subjective norms, molding individuals’ intentions to adopt sustainable behaviors. These findings advocate for an approach that considers the multifaceted nature of individuals’ cognitive processes and emphasizes the significance of addressing the formation of environmental consciousness and attitudes in the pursuit of sustainable actions. By effectively utilizing these mediating factors, policymakers, educators, and practitioners can tailor interventions to stimulate pro-environmental behaviors, fostering a smoother transition toward a more sustainable future. Further research is encouraged to explore additional mediators and moderators, thus deepening the comprehension of the intricate relationships that govern individuals’ decision-making processes in sustainability.

The intricate relationships underscored by this study within the proposed conceptual model offer a comprehensive view. While some indirect effects may be deemed insignificant, several pathways emerge as meaningful mediators. Notably, the relationships between Environmental Consciousness (EC) and Subjective Norms (SN), as well as their impact on attitude (AT) and intention to adopt (IN), emerge as significant mediating factors. Moreover, the indirect effects of knowledge (KN) on Environmental Consciousness (EC) and attitude (AT) on intention to adopt (IN) are also noteworthy. These findings provide insight into the underlying mechanisms that steer farmers’ intention to embrace sustainable practices (Ataei et al., Citation2021; Coulibaly et al., Citation2021; Damalas, Citation2021; Govindharaj et al., Citation2021; Mohammadinezhad & Ahmadvand, Citation2020).

Analyzing specific indirect effects injects depth into our understanding of the interrelationships between constructs. It casts a spotlight on key mediating pathways within the proposed model. These findings contribute to the existing reservoir of knowledge concerning sustainable agricultural adoption behavior. They serve as guiding beacons for future research endeavors and interventions, poised to cultivate a conscious and eco-friendly behavioral landscape.

6.2. Aligning with prior research

The alignment of our findings with established literature reinforces the robustness of specific theoretical frameworks. As noted by (Li et al., Citation2022; Sarkar et al., Citation2022; Tama et al., Citation2021), the emphasis on attitudes as influential drivers of behavior echoes seamlessly in the Sikkim context. However, our rigorous scrutiny prompts us to ponder whether attitudes in this setting are more adaptable and attuned to contextual intricacies than initially perceived.

The prominence attributed to environmental consciousness resonates with the works of Dong et al. (Citation2023), Ma et al. (Citation2021), Pestisha and Bai (Citation2023), Qiao et al. (Citation2022), and Sarwar and Alsaggaf (Citation2020). However, it invites us to delve deeper into a more nuanced perspective. While Serebrennikov et al. (Citation2020) underlined the role of environmental awareness, our study ushers in a novel view by unraveling the intricate interplay between consciousness, cultural narratives, and policy interventions. This evolutionary discourse redirects our attention to the intricate dynamic between inherent values and nurtured consciousness.

The departure from conventional narratives concerning perceived behavioral control accentuates the imperative of acknowledging regional complexities. The suppositions posited by (Sarkar et al., Citation2022; Tama et al., Citation2021) may not be wholly applicable in regions like Sikkim, where environmental constraints significantly mold farmers’ perception of control. This divergence necessitates examining how local conditions shape these perceptions and how interventions can adeptly navigate these constraints.

The alignment with the findings of (Bagheri et al., Citation2021b; Sarkar et al., Citation2022; Tama et al., Citation2021) regarding subjective norms underscores the influence of collective opinions on behavior. However, our study advances by delving into whether these norms signify group cohesion or exert more intricate societal pressures. This proposition engenders a deeper analysis of the equilibrium between community-driven norms and individual autonomy.

Moreover, our study unveils a nuanced comprehension of the role of knowledge in shaping intention. While our findings align with the significance of knowledge, they simultaneously bring to light its intricate nature. Our research accentuates that the impact of knowledge on intention can be intricate and context dependent. This underscores the importance of not just focusing on disseminating knowledge but also on its practical applicability and contextual relevance.

In harmony with the insights from Tama et al. (Citation2021), our study underscores the paramount role of knowledge in steering farmers’ intentions. However, it equally emphasizes the necessity of actionable and pertinent knowledge. Our findings, echoing Tama et al. (Citation2021), shed light on a pivotal policy implication: the need to shift our focus toward providing knowledge that is not only informative but also actionable and tailored to the unique contexts of farmers’ practices. This strategic approach holds the potential to effectively bridge the gap between intention and action, ensuring that knowledge truly becomes a driving force in the embrace of sustainable agricultural practices.

The findings unfolded within this study signify a substantial stride towards unraveling the intricate interplay of behavioral factors propelling the adoption of sustainable agriculture within the unique tapestry of Sikkim. While certain findings corroborate established literature, they unveil complex relationships and novel insights that challenge conventional assumptions.

6.3. Unveiling gaps and complexities

The positive influences of attitude and environmental consciousness on the intention to adopt sustainable practices open a gateway to a significant consideration: transforming this intention into tangible actions. However, a gap between intention and actual behavior is a persistent challenge.

The intriguing negative direct impact of perceived behavioral control warrants further scrutiny. The agricultural community in Sikkim might be deeply entrenched in traditional farming methods, exhibiting skepticism towards novel sustainable approaches. This finding implies that interventions should transcend mere awareness-building and address the intricate web of ingrained beliefs and established practices.

The ambiguous role of knowledge in shaping intention highlights the importance of ensuring that knowledge is not just disseminated but is also actionable and relevant. The focus should shift toward providing actionable and contextually relevant knowledge that can effectively bridge the gap between intention and action.

Lastly, the significant influence of subjective norms accentuates the potency of collective opinions in the decision-making process. While this can be harnessed as a driving force for sustainable transformation, it also demands a cautious approach, especially if prevailing norms contradict sustainable agriculture principles.

6.4. Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the light of certain limitations. First, the generalizability of the results is limited because of the specific sample size of farmers in Sikkim. Further research with more diverse and representative samples from different regions is necessary to enhance the generalizability of our findings. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures introduces a potential social desirability bias. Participants may provide responses perceived as socially favorable rather than reflecting on their true intentions or behaviors. Future studies should incorporate objective and observational data to mitigate this bias. Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design restricts establishing causal relationships between variables. Longitudinal studies that capture changes in farmers’ attitudes, knowledge, and intentions over time would provide robust insights into the dynamics of sustainable agriculture adoption.

6.5. Implications and recommendations

The study’s implications for policymakers and practitioners are profound. As highlighted by the study’s findings, designing interventions encompassing the multi-dimensional nature of behavior change becomes paramount. Initiatives should focus on changing attitudes, increasing knowledge, and fostering environmental consciousness that resonates with local cultural narratives.

The role of subjective norms in driving intentions mandates interventions that address both individual agency and community cohesion. Striking this balance requires an in-depth understanding of local social dynamics and how collective norms intertwine with personal decision-making.

To foster sustainable agriculture in Sikkim, strategies must address the multifaceted nature of farmers’ decision-making processes, from knowledge acquisition to cultural nuances. Promoting positive attitudes, enhancing environmental consciousness, and bridging the knowledge-attitude-action gap is pivotal. Given the influence of subjective norms, community engagement, and peer-driven interventions might prove particularly effective.

Based on this study’s findings, several recommendations can be made to promote sustainable agricultural adoption among farmers. First, it is crucial to enhance environmental education initiatives that target farmers. These programs should increase awareness, knowledge, and understanding of sustainable agriculture’s environmental benefits and best practices. Second, strengthening extension services is vital for providing farmers with technical guidance, resources, and support. This can improve their perceived behavioral control and increase their likelihood of adopting sustainable agricultural practices. Policymakers should introduce policies and incentives to promote the adoption of sustainable agriculture. Financial incentives, subsidies, and access to eco-friendly inputs, technology, and training programs can enable farmers to embrace sustainable practices.

6.6. Future directions

Our exploration, while detailed, is an initial foray into the vast expanse of sustainable agriculture adoption dynamics. Ethnographic studies could unveil richer narratives, while experimental designs might establish causal pathways. As global paradigms shift and Sikkim evolves, the symbiosis between farmers and sustainable agriculture deserves continuous and critical scholarship.

The complexities unearthed in this study underscore the need for more granular, context-specific research. Future investigations might benefit from exploring other potential mediators and moderators, drawing further comparisons with global trends, and contextualizing findings within the socio-cultural fabric of the region.

Comparative studies across different cultural contexts could unveil broader behavioral patterns, while experimental designs might uncover causal mechanisms. Future research should consider longitudinal studies to capture changes in farmers’ intentions and behaviors over time, provide a deeper understanding of the factors influencing sustainable agriculture adoption, and identify critical intervention points for long-term sustainability in the agricultural sector.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the behavioral factors influencing farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. Delving into the intricate layers of Sikkim’s landscape, this study uncovers how attitudes, environmental consciousness, subjective norms, knowledge, and perceived behavioral control interact. Amidst Sikkim’s unique socio-cultural and geographic backdrop, the study challenges conventional ideas and reveals new pathways. The findings emphasize the roles of environmental consciousness, knowledge, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms in shaping farmers’ attitudes and intentions toward sustainable agriculture.

The study underscores the positive link between environmental consciousness and the desire to adopt sustainable farming practices. This highlights the importance of fostering awareness and a sense of environmental responsibility among farmers. Moreover, the impact of knowledge, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms on farmers’ intention to embrace sustainable practices stresses the need for tailored educational initiatives, technical assistance, and social encouragement to drive the adoption of sustainable agriculture.

This study’s exploration of prior literature offers fresh perspectives, challenging established assumptions. As assumptions crumble, the study questions whether attitudes in Sikkim’s agrarian landscape are not just guiding forces but dormant beliefs awaiting a suitable catalyst. Environmental consciousness takes center stage, raising the profound query of whether it’s innate or nurtured. This study’s narrative suggests that interventions might serve as stimuli to amplify inherent inclinations.

A significant departure emerges when considering perceived behavioral control. Pre-existing notions, as proposed by (Tama et al., Citation2021), undergo a profound transformation in the intricate landscape of Sikkim, where control intertwines with environmental constraints. In this context, perceptions anchored to the challenges posed by nature reshape the influence of this construct, prompting a regional re-evaluation. Amid Sikkim’s closely-knit communities, subjective norms emerge as foundational pillars. Beyond fostering community cohesion, they exert subtle yet discernible societal pressures. The study’s in-depth exploration delves further, raising questions about individual autonomy amidst collective consciousness. The role of knowledge sparks a thought-provoking debate: Is knowledge, on its own, overrated? Sikkim’s context uncovers a different facet, where knowledge is a cornerstone for interconnected constructs to build upon.

The study’s resonance with global literature emphasizes its robustness. Yet, its distinctiveness within Sikkim is evident. It unveils a localized perspective, enlivening the discourse on sustainable agriculture. These findings resonate within academic circles and carry significant weight in policy discussions and among practitioners.

As Sikkim’s agricultural sector embarks on the journey toward sustainability, this study stands as a compass. It paints an intricate portrait, unveiling the nuances that make Sikkim’s journey distinct. The path becomes more evident with each insight—fostering positive attitudes, nurturing environmental consciousness, bridging knowledge-action gaps, and addressing behavioral control barriers.

In this symphony of insights, the study demonstrates that adopting sustainable agricultural practices is not a singular concept but a complex interplay of diverse influences. This study contributes to the growing knowledge of farmers’ intentions to adopt sustainable agricultural practices. By understanding the factors influencing farmers’ attitudes and intentions, targeted interventions and strategies can be developed to promote sustainable agricultural adoption and to drive positive environmental changes in the agricultural sector. Achieving widespread adoption of sustainable practices is crucial for ensuring a sustainable future and the well-being of farmers, communities, and ecosystems.

Ethical approval

This research project, part of the Ph.D. study, obtained ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethical Committee of the KH Manipal (MAHE). Approval was granted under reference number IEC-2021-494. In adherence to ethical standards, informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. The consent process ensured that participants were well informed about their participation’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits before providing their consent.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (60.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We are immensely grateful to the farmers who willingly participated and shared their insights, as their involvement was crucial to the success of this research. We also express our sincere appreciation to the anonymous reviewers whose thoughtful feedback significantly enhanced the quality and rigor of this research. Your contributions have been instrumental in shaping this work and advancing its scholarly impact.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available at: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/4mhjk63xz6/1

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2261212

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Roshan Raj Bhujel

Roshan Raj Bhujel is a passionate researcher dedicated to unlocking the secrets of sustainable agriculture. Our exploration reaches far beyond these pages, intertwining with vibrant research endeavors that delve deep into environmental awareness, community empowerment, and groundbreaking agricultural advancements. This study forms a pivotal piece of our broader puzzle, aiming to inspire both academia and practical solutions that cultivate sustainable growth in the realm of agriculture. Join the mind behind the study, driven by the quest for sustainable solutions. From field to fork, our research dives into the intricate tapestry of farming practices, fueled by a vision of a brighter, eco-friendly future. Beyond these findings, our pursuits extend to nurturing sustainable ecosystems, weaving connections that empower farmers and enrich our natural world.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behavior: Reactions and reflections. Psychology and Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

- Ataei, P., Gholamrezai, S., Movahedi, R., & Aliabadi, V. (2021). An analysis of farmers’ intention to use green pesticides: The application of the extended theory of planned behavior and health belief model. Journal of Rural Studies, 81, 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.11.003

- Azman, A., D’Silva, J. L., Samah, B. A., Man, N., & Shaffril, H. A. M. (2013). Relationship between attitude, knowledge, and support towards the acceptance of sustainable agriculture among contract farmers in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n2p99

- Bagheri, A., Emami, N., & Damalas, C. A. (2021a). Farmers’ behavior in reading and using risk information displayed on pesticide labels: A test with the theory of planned behavior. Pest Management Science, 77(6), 2903–2913. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6326

- Bagheri, A., Emami, N., & Damalas, C. A. (2021b). Farmers’ behavior towards safe pesticide handling: An analysis with the theory of planned behavior. Science of the Total Environment, 751, 751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141709

- Baydur, H., Eser, E., Sen Gundogan, N. E., Ayhan, E., Eser, S., De de, B., Hazneci, E., Öztekin, Y. B., Ekuklu, G., Cevizci, S., & den Broucke, S. (2023). Psychological determinants of Turkish farmers’ health and safety behaviors: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Agriculture (Switzerland), 13(5), 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13050967

- Baylina, M., & Rodo-Zarate, M. (2020). Youth, activism and new rurality: A feminist approach. Journal of Rural Studies, 79, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.08.027

- Bosnjak, M., Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.3107

- Choubey, M. (2016). Organic agriculture in Sikkim: Challenges and future strategy. Agricultural Situation in India, 73(9), 28–33. . https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20173181351

- Coulibaly, T. P., Du, J., Diakité, D., Dabuo, F. T., & Coulibaly, I. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behavior to assess farmers intention to adopt sustainable agricultural practices: Evidence from cocoa farmers in Côte d’Ivoire. Ama, 51(3), 1733–1748. . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354268251_Extending_the_theory_of_planned_behavior_to_assess_farmers_intention_to_adopt_sustainable_agricultural_practices_evidence_from_cocoa_farmers_in_Cote_d'Ivoire

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

- Damalas, C. A. (2021). Farmers’ intention to reduce pesticide use: The role of perceived risk of loss in the model of the planned behavior theory. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(26), 35278–35285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13183-3

- Dong, H., Zhang, Y., & Chen, T. (2023). A study on farmers’ participation in environmental protection in the context of rural revitalization: The moderating role of policy Environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1768. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031768

- Durán Gabela, C., Trejos, B., Lamiño Jaramillo, P., & Boren-Alpízar, A. (2022). Sustainable agriculture: Relationship between knowledge and attitude among university students. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(23), 15523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315523

- Faisal, M., Chunping, X., Akhtar, S., Raza, M. H., Khan, M. T. I., & Ajmal, M. A. (2020). Modeling smallholder livestock herders’ intentions to adopt climate smart practices: An extended theory of planned behavior. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27(31), 39105–39122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09652-w

- Feliciano, D. (2022). Factors influencing the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: The case of seven horticultural farms in the United Kingdom. Scottish Geographical Journal, 138(3–4), 291–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702541.2022.2151041

- Foguesatto, C. R., Borges, J. A. R., & Machado, J. A. D. (2020). A review and some reflections on farmers’ adoption of sustainable agricultural practices worldwide. Science of the Total Environment, 729, 138831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138831

- García, G. A. G., Gutiérrez-Montes, I., Núñez, H. E. H., Salazar, J. C. S., & Casanoves, F. (2020). Relevance of local knowledge in decision-making and rural innovation: A methodological proposal for leveraging participation of Colombian cocoa producers. Journal of Rural Studies, 75, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.01.012

- Gericke, N., Boeve de Pauw, J., Berglund, T., & Olsson, D. (2018). The sustainability consciousness questionnaire: The theoretical development and empirical validation of an evaluation instrument for stakeholders working with sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 27(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1859

- Govindharaj, G.-P.-P., Gowda, B., Sendhil, R., Adak, T., Raghu, S., Patil, N., Mahendiran, A., Rath, P. C., Kumar, G. A. K., & Damalas, C. A. (2021). Determinants of rice farmers’ intention to use pesticides in eastern India: Application of an extended version of the planned behavior theory. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.12.036

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Handavu, F., Chirwa, P. W., & Syampungani, S. (2019). Socioeconomic factors influencing land-use and land-cover changes in the miombo woodlands of the Copperbelt province in Zambia. Forest Policy and Economics, 100, 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.10.010

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing (pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Imani, B., Allahyari, M. S., Bondori, A., Emami, N., & El Bilali, H. (2021). Adoption of organic potato production in Ardabil Plain, Iran: An application of the extended theory of planned behaviour. Potato Research, 64(2), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-020-09471-z

- Imani, B., Allahyari, M. S., Bondori, A., Surujlal, J., & Sawicka, B. (2021). Determinants of organic food purchases intention: The application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Future of Food: Journal on Food, Agriculture and Society, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.17170/kobra-202011192216

- Kassie, M., Jaleta, M., Shiferaw, B., Mmbando, F., & Mekuria, M. (2013). Adoption of interrelated sustainable agricultural practices in smallholder systems: Evidence from rural Tanzania. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(3), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.08.007

- Laurett, R., Paço, A., & Mainardes, E. W. (2021). Measuring sustainable development, its antecedents, barriers and consequences in agriculture: An exploratory factor analysis. Environmental Development, 37, 100583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100583

- Lazarenko, V. (2022). Modern prerequisites for forming social environmental value according to behavioristic approach. Agroecological Journal, 2(2), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.33730/2077-4893.2.2022.263327

- Liao, X., Nguyen, T. P. L., & Sasaki, N. (2022). Use of the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) model to examine sustainable agriculture in Thailand. Regional Sustainability, 3(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsus.2022.03.005

- Li, J., Jiang, R., & Tang, X. (2022). Assessing psychological factors on farmers’ intention to apply organic manure: An application of extended theory of planned behavior. Environment Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02829-y

- Ma, L., Qin, Y., Zhang, H., Zheng, J., Hou, Y., & Wen, Y. (2021). Improving well-being of farmers using ecological awareness around protected areas: Evidence from Qinling region, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189792

- Meek, D., & Anderson, C. R. (2020). Scale and the politics of the organic transition in Sikkim, India. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems, 44(5), 653–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2019.1701171

- Mohammadinezhad, S., & Ahmadvand, M. (2020). Modeling the internal processes of farmers’ water conflicts in arid and semi-arid regions: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Hydrology, 580, 580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124241

- Nguyen, T., Doan, X., Nguyen, T., & Nguyen, T. (2021). Factors affecting Vietnamese farmers’ intention toward organic agricultural production. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(8), 1213–1228. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijse-08-2020-0554

- Pestisha, A., & Bai, A. (2023). Preferences and knowledge of farmers and internet-orientated population about renewable energy sources in Kosovo. International Review of Applied Sciences and Engineering, 14(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1556/1848.2022.00516

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Qiao, D., Luo, L., Zheng, X., & Fu, X. (2022). External supervision, face consciousness, and pesticide safety use: Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7013. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127013

- Santacoloma-Varón, L. E. (2015). The importance of farmers’ economy in contemporary contexts: A look into the Colombian case. Entramado, 11(2), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.18041/entramado.2015v11n2.22210

- Sarkar, A., Wang, H., Rahman, A., Qian, L., & Memon, W. H. (2022). Evaluating the roles of the farmer’s cooperative for fostering environmentally friendly production technologies-a case of kiwi-fruit farmers in Meixian, China. Journal of Environmental Management, 301, 301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113858

- Sarma, P. K. (2022). Farmer behavior towards pesticide use for reduction production risk: A theory of planned behavior. Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy, 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcb.2021.100002