?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Although camel production is the primary source of revenue for pastoralists and agro-pastoralists in the Borana, a number of issues affect camel performance in the area, with one of the most pressing being feed availability. Camel production often involves optimizing available feed availability, which is considered to be the principal limiting factor in a free-browsing environment. The purpose of this study was to investigate the feed resources that are available for dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) and their utilization practices in the Borana Plateau, southern Ethiopia. A household survey questionnaire, a focused group discussion, and key informant interviews were utilized to collect data from 364 camel herders in nine kebeles in the districts of Yabello, Elwaye, and Gomole. The results show that browsing trees and shrubs (53.3%) were the most commonly known feed resources accessible in the study’s areas, followed by herbaceous feed resources (42.3%). The total dry matter (DM) available was 1379.59 tons less than the total dry matter required for camels, which was 5242.71 tons. The total dry matter balance was −3863.12 tons along the studied districts, which was below the requirements. Camel feed is scarce all year, and the survey results show that 90.9% of respondents do not conserve camel feed in any way. Furthermore, 89.6% stated that they have received no training in feed conservation measures. This finding highlighted the significance of raising herder awareness of fundamental feed management and conservation techniques.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

To better focus on the options for providing enough feed resources and alternative nutritional aspects of feeds throughout the dry and rainy seasons, it is important to better understand the availability of feed and current utilization. This can be done by raising pastoralist awareness and informing policymakers about what is available on the ground. The development of unconventional feeding methods has also had an impact on the production of camels, which camel owners must acknowledge. By making the feed situation in the study area accessible, these findings will help improve the feeding system, which is essential for camel farmers in order to maximize productivity.

1. Introduction

Camel herding is growing in popularity around the world, owing to its climatic tolerance, capacity to function effectively in harsh environments, and ability to supply food (Babege et al., Citation2021). The global camel population has nearly tripled in the last 60 years, rising from 13 million in 1961 to around 36 million in 2021 (Faye, Citation2020). The one-humped camel is the best-adapted species to harsh arid and semi-arid environments, where it is managed using indigenous knowledge and in extensive mobile pastoral systems, maximizing geographically and temporally dispersed grazing and water supplies (Alemnesh et al., Citation2020; Hassen et al., Citation2022; Mirkena et al., Citation2018). The availability of feed supplies and the nutritional quality of available feeds influence camel productivity (Hidosa & Tesfaye, Citation2018; Kochare et al., Citation2018).

Due to feed scarcity (both in quality and quantity), camels in Ethiopia are mainly feed on low-nutritional-quality natural pasture (like a browser of a broad spectrum of fodder plants, including trees, shrubs, and occasionally hard-thorny, bitter, and halophytic (salty) plants that grow naturally in the desert and other semi-arid areas). Nonetheless, these poor-quality natural pastures are limited and deteriorate during the dry season. Feed shortages and substantial difficulties in lowland environmental settings are a consequence of seasonality in feed supply, and a lack of understanding about feed conservation mechanisms also impacts feeding systems (Asmare et al., Citation2017; Hassan et al., Citation2020; Raju et al., Citation2017). So, identifying, nutritionally characterization, and maintaining a sufficient supply of both quantity and quality of feed supplies throughout the year is critical for any substantial and sustained increase in camel output (Hassan et al., Citation2020; Kochare et al., Citation2018).

The majority of studies in various parts of the country focused on other farm animals, but the current information on camel feed resources is insufficient to categorize available feed types, carry out usage plans, and determine whether this is enough for the total number of livestock in that area. Because environmental changes are visible and common in the Borana zone, fresh information is required for future planning in the camel production industry. However, depending on agro ecology, animal production techniques, and seasonal factors, the availability and relative importance of various feed resources change from time to time and from place to place.

The unfolded aspects of what is currently available in terms of feed resources in relation to season and location, the utilization practices, and the annual production capacity, as well as the policy issues for future investment in camel production, are significant turning points for this research. Unfortunately, a good estimate of the available camel feed supply in large production areas is still missing. As a result, the semi-humid (Yabello), hot lowland (Elwaye), and semi-arid (Gomole) districts in Borana were the focus of this assessment of camel feed availability, as they fairly represented all of the places where camel rearing is regularly practiced. Therefore, the objective of the study was to identify major available camel feed resources, demand, and feeding practices in three selected agro ecology (districts) of Borana Zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

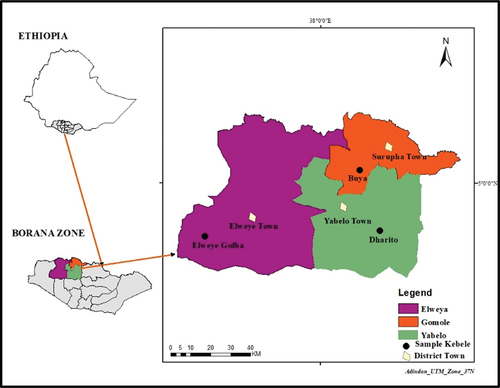

The study was conducted in three areas of the Borana Zone in southern Ethiopia: hot lowland (Gamojji), semi-humid (Badda), and semi-arid (Badda Dare) (Figure ). This classification is based on annual and monthly mean temperature and rainfall, seasonal changes in rainfall, and native vegetation type. Elwaye district represents the hot lowland, which is located at 04° 96.34” latitude, 037° 89.24‘ longitude, and 1379 m elevation; the semi-humid (Yabello district) is located at 04° 89.11’ latitude and 038°10.75‘ longitude, with an elevation of 1687 m. Gomole is located at 05°12.82’ latitude and 038° 29.39” longitude, with an elevation of 1741 m.

2.2. Sampling procedures and sample size

2.2.1. Procedures

The study kebeles and households were chosen using random and on-purpose selection approaches based on their representative character in the study district. The districts were further separated into three zones (strata) based on agro ecology: semi-humid, hot lowland, and semi-arid. Three kebeles from each district were chosen in the same manner.

2.2.2. Sample size

The sample size was determined using Yemane’s (Citation1967) established, simplified procedure for calculating sample size.

In order to determine the necessary sample size at a 95% confidence level, the representative sample size is n, where N is the total number of household heads in the chosen nine kebeles, and e = (5%) is the level of precision. This is because camel herders have a uniform production system and social values. As a result, a total of 364 households from both altitudes of the area (103 from Yabello, 111 from Elwaye, and 150 from Gomole) were chosen as interviewees for this study.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Household survey

The interviews were conducted at the herders residence to allow for cross-checking of the herders’ responses regarding the type of available feed resources, the seasonal calendar of feed resource availability, the types of land use for feed resources available in the study area, seasonality, and locational effects on feed resource availability and utilization practices. The questionnaire was written in English and then translated to “Afaan Oromo”, the local language. Before being given, a systematic questionnaire was prepared, pre-tested, and then refined and corrected based on the responses of the respondents.

2.3.2. Focus group discussion

Twelve people from each of the three locations participated in the discussion, with both sexes from a variety of wealth categories, communities, and education levels specifically chosen to extract data on camel feed resources, seasonal and altitude variations in availability, demand, and feeding practices. Three focus groups were held, one in each kebele, with a total of 32 participants.

2.3.3. Key informant discussion

Key informant interviews were conducted to provide an in-depth understanding of camel feed resources, seasonal and altitude variations in availability, demand, and feeding habits, and the community’s socioeconomics. This study used semi-structured dialogue techniques to produce eight key interview questions. We selected and interviewed eight key informant elders (herders and government officials).

2.4. Estimation of the quantity of available feed resource

Estimates were made of the districts’ total livestock units, available feed resources, and annual maintenance needs. The total annual livestock feed production was divided by the annual feed production and animal requirements in the study areas (Madalcho et al., Citation2019). It was believed that there would be a feed scarcity in the districts unless the amount of feed produced each year was greater than what was needed to maintain the animals (Kochare et al., Citation2018). Using data that was available about the communal Kalo, farmland, open browsing land, and private land, the amount of feed resources was estimated (see Table ). The corresponding district and zone livestock sectors were used to compile the total livestock population. The estimated feed production was calculated. For trees and shrubs, the FAO (Citation1987) multiplier factor of 1.2 t/ha conversion ratios was used (Von Carlowitz, Citation1984).

Table 1. Description local name for landscapes and classification criteria of feed resources

2.5. Estimation of dry matter, crude protein and metabolizable energy contents of feed resources to animal requirements

Using total livestock unit and land area data gathered from respondents and agricultural offices, the amount of feed resources in the study area was estimated, such as total dry matter, digestible crude protein, and metabolized energy feed supply (Bulale, Citation2000). The sum of the maintenance energy requirements for each type of cattle was used to determine the total energy requirements. The livestock population was translated into tropical units (TLU) using conversion factors in order to compare the balance (Kearl, Citation1982). By summing the nutrients provided by each feed resource type, the total amount of dry matter that was accessible, metabolizable energy, and digestible crude protein was calculated. In the demand-side estimation, the total daily DM maintenance requirements from the feed resources were determined to be 6.25 kg/DM, 160 g, and 29.84 MJ, dry matter, digestible crude protein, and metabolized energy, respectively. This is equivalent to 2.5% of the animal’s total body weight for one tropical livestock unit (FAO, Citation1986). (Body mass index: 250 kg) per day for livestock maintenance requirements, a standard method developed by King (Citation1983) for tropical areas was used.

Where, ME is maintenance (MJ day−1animal−1); LW is live body weight; km (MJ kg-1) is the efficiency with which ME is used for maintenance and is related to the average forage metabolizable and always tends to lie between 0.64–0.70 (Ayele et al., Citation2021).

2.6. Statistical analysis

MS Excel was used to manage and organize the collected data, and the statistical package for social science was used to analyze it (SPSS version 25, Citation2017). Descriptive statistics, such as frequency, mean, and percentages, were employed to illustrate qualitative characteristics. The General Linear Model (GLM) technique was used to compare the variations in dry matter yield between locations. Statistics were considered significant if the P value was less than or equal to 0.05. The statistical model that was used to assess the availability and usage of feed resources is described below:

Yijk =μ+ Li + Si + LSij + Ʃij

Where: Yij = the response of the ith agro ecology of the jth supply of feed nutrient;

μ = overall mean;

Li = supply of feed nutrient in the ith agro ecology (i = 1, 2, 3); and

Sj= the jth effect of season on feed supply (j = 1, 2)

εij = random error.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Demographic characteristics of the households

3.1.1. Household characteristics

In Table , each respondent family in the study area is presented by gender, marital status, and level of education, tribe affiliation, and age. The agro-ecology of the study area’s semi-humid, hot lowland, and arid areas are 96.1%, 93.7%, and 82.0% male, respectively, whereas the semi-humid, hot lowland, and semi-arid areas are 6.3%, 3.9%, and 18.0% female, respectively. In semi-humid, hot lowland, and arid areas, respondents with educational statuses of 97.1%, 91.0% and 88.7%, respectively, were unable to read and write. Traditional ways of life were common throughout the study areas, and the majority of interviewees had never attended a formal educational institution. This result is comparable to that of Mengistu et al. (Citation2020), Berhanu et al. (Citation2022), and Jiso and Guja (Citation2022), who observed that the male-headed households covered 90.7% and 9.3% of females, with the majority of people who took part in the same study in the same places being illiterate. The average marital status of respondents in the study areas was 85.4% married, while the rest were single, divorced, or widowed. According to Muluneh et al. (Citation2022), which was conducted in the same district, the respondents (herders) had an average age of 49.79% years, and the majority of them (91%) had never attended formal education. The respondents’ tribal affiliations were 98.7% Gabra in Gomole, 78.6% and 81.1% Borana in Yabello and Elwaye, and 21.4% and 14.4% Dogodi in Yabello and Elwaye.

Table 2. Household characteristics of respondents in study area

3.1.2. Land use coverage and livestock population in the study areas

Table displays the overall land uses and coverage (ha) in the study areas, which are classified as open grazing land, communal kalo, private kalo, and farmland. The total coverage was assessed to be 839,091.81 hectares of land that can support forage production. The largest portion of land uses in the study areas, open grazing areas and communal kalo, were covered by 58% and 27% of total land coverage, respectively. 68% of Gomole land was used as community kalo, whereas 17% of Elwaye was used for farming. Private kalo concerns are lower in all of the study areas than in other land use categories. The majority of tropical livestock units (65% and 18%) consisted of cattle and camels (Table ). The higher proportion of cattle (72%, 67%, and 60%, respectively) in Elwaye, Yabello, and Gomole areas. This data is consistent with Habte et al. (Citation2020), who observed that land use or cover in lowland areas was transitioning from grass to bush or shrub land, followed by woody plant cover. This transition is becoming one of the most pressing challenges for cattle feed; on the other side, it provides excellent prospects for camels, which rely considerably on browsing trees.

Table 3. Land types and area covered in (ha) unit in the study areas

Table 4. Total number of livestock and total number of livestock units within the study areas

3.2. Major feed resource for camels in the study area

Table illustrates seasonal, feed type, and agro-ecological fluctuations in camel feed resources. In semi-arid agro ecology, the high proportion was 75% browsing trees in the dry season. However, in hot lowland agro ecology, browsing feed types scored 60% during the rainy season. Overall, camel herders agreed that browsing trees were the most common sources of feed for camels, followed by trees and shrub species in the study areas. According to the survey findings, 53.3% of respondents reported browsing trees and shrubs during the rainy season, whereas respondents (42.3%) used herbaceous and shrub feed sources. Compared to both seasons, browsing trees contributed significantly to the available forage sources for camel production. Chi-square statistics were employed to investigate the relationship between feed types (browning trees, herbaceous and shrub plants, and others) and agro ecology (semi-humid, hot lowland, and semi-arid). At the 5% significance level, there is a difference between feed source type and respondents’ agro ecology (χ2 = 22.56, df = 2, p = 0.001). Camel are not the primary grazers in this study area, which means they do not consume grass until there is a feed shortage. Alkali et al. (Citation2017) revealed that fodder plants and bushes emerge as critical resources. Camels have traditionally relied mostly on browsing species in the examined locations, with goats serving as the principal competitor for available food resources (Ayele et al., Citation2022). According to the current study, browsing plants such as trees were the main sources of feed for camels. This statement is reinforced by Hassan et al. (Citation2020), who revealed that herbaceous and shrub species were the second-most important source of camel nutrition throughout the year, behind browsing trees and shrubs. This finding is in line with the findings of research conducted in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State, which found that browsing trees and shrubs constitute the majority of camel feed resources, with herbaceous species accounting for only a small proportion (Madalcho et al., Citation2019). The seasonal feed availability in the study area fluctuates, according to Mamo et al. (Citation2023); natural pasture utilization is higher during rainy seasons, while crop remnants are easier to get by during dry seasons. According to Babege et al. (Citation2021), pastures were the predominant source of camel feed, and the camels preferred to eat trees, bushes, and grasses.

Table 5. Diversity of feed types, seasonality, and agro ecology in the study areas

3.3. Source of feeds resources for camels

The seasonal change and agro ecology of the sources of camel feed are shown in Table . While overall feed resources were 46% during the dry season, community kalo contributed the most to the average of all agro ecologies, followed by communal browsing land at 39%. However, during the rainy season, communal browsing land accounted for 84% of the livestock feed that was accessible in the study areas. There is no statistically significant variation in feed use between the research locations during the wet and dry seasons, as shown (P > 0.05). According to Derara and Bekuma (Citation2020), communal grazing land, private grazing land, fallow grazing space, and roadside were the key sources of feeding livestock, with communal grazing land yielding more biomass than legumes and herbaceous land. This finding is consistent with the assumption reported by John and Peter (Citation2019). In some areas, kalo looks to be transforming into de facto private grazing and/or farmed land, raising concerns about the private appropriation of communal territory. This finding aligns with the findings of Alemu et al. (Citation2019), who reported that the position of communal grazing land varies across the agro-ecologies studied, with the majority of respondents (78.65% in the highlands, 86.67% in the midlands, and 83.33% in the lowlands) believing that the size of communal grazing pastures is shrinking over time. This study found that open browsing continues to make a significant contribution to camel feed resources. The traditional dry season feed reservoir has also made an important contribution to the feeds that may be used during the feed scarcity period.

Table 6. Seasonality and agro ecology of camel feed sources in study areas (N = 364)

3.4. Estimated annual available feed supply

The land in the area was largely utilized for open grazing, according to the Borana Zone Agriculture Office (Citation2022). Table shows the anticipated amount of feed needed to keep the total livestock population in every category. Based on their yearly DM production value, available feed resources can be categorized as farmland, private land, communal kalo, and open grazing land. The total yearly DM feed supply available for use in Yabello, Elwaye, and Gomole was 3517.84 metric tons, 531.38 metric tons, and 1195.06 metric tons, respectively. The communal kalo contributed 829.38 metric tons to the total DM in the Gomole, while open grazing land (2374.68 and 374.05 metric tons, respectively) was expected to contribute the most to the total DM in the Yabello and Elwaye. Farmland produced 479.33, 89.05, and 76.5 metric tons in Yabello, Elwaye, and Gomole, respectively. The total DCP received from the main feed suppliers available in the research regions is 90.05 kg, 13.59 kg, and 34.07 kg at Yabello, Elwaye, and Gomole, respectively.

Table 7. Estimated available dry matter production (tonnes), ME (MJ), and DCP (kg) per feed resource in the study areas

According to the findings, there were inadequacies or gaps in feed supply and demand across study areas. Camel protein and energy consumption are projected to be lower than tropical livestock units, which use 6.25 kg, 160 g, and 29.84 MJ (MJ/TLU) DM, CP, and ME, respectively. This finding contradicts previous studies (Yisehak & Janssens, Citation2013). As a result, no dry matter, protein, or energy supplements are necessary for camel production. However, the overall annual demand for camels was determined to be low, as there was not a substantial variance in the quantity in three agro ecologies. In contrast to the current data, Ayele et al. (Citation2021) reported that feed availability did not meet the nutritional needs of livestock in the research area in terms of DM, ME, and DCP. This finding is consistent with Hassan et al. (Citation2020), who confirmed that the total dry matter produced from different feed resources was insufficient to meet the dry matter requirements of livestock in the lowland area. According to Madalcho et al. (Citation2019), browsing trees and shrubs were the primary sources of camel feed in pastoral and agro-pastoral areas. Although the quality and quantity of camel feed vary depending on the season (Ayele et al., Citation2021), According to Hidosa and Tesfaye (Citation2018), the total dry matter produced in the pastoral region from diverse feed supplies was insufficient to meet the dry matter requirements of livestock and enable viable livestock production.

3.5. Estimated annual feed balance between supply and requirements

There were 1379.59 metric tons of TDM available for animals, considerably fewer than the required 5242.7 metric tons. TDM was found to be 3523.49 metric tons across the research districts; however, the required and available annual TDM balance was −3863.12 metric tons, which was less than what livestock need (Table ). The yearly DCP balance of 98,917.66 kg, the annual TLU demand of 35.33 kg, and the reported DCP nutritional needs of 134.25 kg were sufficient for the current camel species. Elwaye production decreased by 13.60 kg, while Yabello output increased by 90.05 tons, according to the districts. The DCP’s yearly TLU standards for 7.95 kg Elwaye were much lower than those for all districts. Gomole had a higher yearly DCP balance (14149.41 kg) than Elwaye (5653.7 kg).

Table 8. Mean estimated annual TDM (tonnes), ME (MJ), and DCP (kg) available, requirement, and balance per study for maintenance of tropical livestock unit in the study area

The total ME availability was 7021.52 MJ, with an annual TLU demand of 1848.12 MJ. Yabello created 479.99 MJ of ME, Elwaye generated 711.46 MJ, and Gomole generated 1600.06 MJ. Elwaye required 415.77 MJ per year, while Gomole and Yabello required 860.04 MJ and 572.30 MJ, respectively. ME annual nutritional balance for Gomole, Yabello, and Elwaye, respectively, was 740.01, 4137.69, and 295.68 MJ.

Hence, the annual utilizable feed dry matter satisfied more than expected amounts of the livestock maintenance requirements in the study locations (Table ). The yearly utilizable DM, DCP, and ME feed supply varied throughout the three agro-ecologies in relation to the overall tropical livestock unit. This finding is congruent with the findings of Hassan et al. (Citation2020), who found that the total dry matter provided by different feed suppliers was insufficient to meet the dry matter requirements of livestock in the lowland area. According to Madalcho et al. (Citation2019), the principal sources of camel feed in pastoral and agro-pastoral ecosystems were browsing trees and bushes. Despite the fact that camel diet quality and quantity vary according to season (Ayele et al., Citation2021), Hidosa and Tesfaye (Citation2018) discovered that the total dry matter produced in the pastoral region by various feed providers was insufficient to meet animal dry matter requirements and allow profitable livestock production. This finding could be compared to Abera et al. (Citation2014) discovery that most readily available feed supplies lower yearly livestock demands, meeting just a smaller percentage of total maintenance needs, which could be due to conversion variables or other feed components not being included. We ran across the same problems when we tried to include alternative feed resources, which may have different conversion factors due to limited access to previous initiatives in relevant fields.

3.6. Feed conservation and feeding practices

Throughout the study areas, camels most frequently use natural browsing as a form of feeding. At times of feed shortage, particularly during the dry season, conservation is employed to assure continuity in feed availability for camel production. According to key informant interviews, there was little discussion of feed conservation or feeding strategies in focus groups with camel herders, despite their use of free grazing. In the Table , the survey’s findings show that 90.9% of participants do not conserve camel feed in any way. Furthermore, 92.9% of respondents were not aware that camels are kept in other places using feed conservation techniques. 89.6% said they had no training on feed conservation techniques. According to the survey’s findings, camels typically fuel themselves through free browsing throughout the year. Almost 80.2% of respondents only ever browse and do not practice feed conservation. When asked why they did not conserve feed, 61.5% cited a lack of knowledge, while 25.5% reported a shortage of supplies for such feed. We took a sample of 364 camel herders to see if the proportion of experienced camel feed conservationists (72 out of 364) and those without such experience (292 out of 364) was equivalent.

Table 9. Feed conservation and experiences of feeding from other sources (N = 364)

The results are in line with those of Duguma and Janssens (Citation2021), who discovered that despite feed constraints and a lack of understanding about forage production and utilization, none of the respondents engaged in unconventional forage production. Hidosa and Tesfaye (Citation2018), who found that free grazing was the main method of feeding cattle and that pastoral communities lacked any tendencies toward conserving feed and giving concentrate supplements to the livestock, confirm this conclusion.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study aimed to examine the present camel feed supply, demand, and feeding practices on the Borana plateau. The expected balance between feed resource supply and feed demand varies by location and season. The available annual dry matter supplies and the camel feed requirements did not coincide in the research region, which was characterized by a smallholder agro-pastoral production system. This study revealed that camel production is entirely dependent on traditional feeding practices in natural habitats. However, the relationship between sustainable camel production and environmental characteristics in regard to feed supply quality, non-traditional feeding practices, and conservation mechanisms must be recognized. This finding indicated that greater focus should be placed on educating, raising awareness, and training camel herders in fundamental feed management and conservation techniques. The available data suggests that the production of camels will be more severely impacted until the feed deficit is eased by improving the availability and quality of feeds and implementing strategic feeding. Furthermore, further studies are required to explore the nutritional qualities of selected feed resources as well as camel adaptation to feed shortages throughout agro ecology and seasons across larger areas.

Consent to participate

Informal verbal consent was obtained from all of the Participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty at Arba Minch University as well as the camel herders who helped with fieldwork. All data numerators, but especially Bule Golicha and Abduba Roba, should be recognized for their work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Roba Jiso

Roba Jiso Wako holds a M.Sc. in livestock production and pastoral development from Mekelle University in Ethiopia as well as a B.Sc. in Animal, rangeland, and wildlife science. Over the course of roughly ten years, he served as a development practitioner for numerous humanitarian organizations. His research focuses on the dynamics of camel feed resources, utilization patterns, production challenges, pastoralists’ coping mechanisms, and various aspects of camel production.

Yisehak Kechero

Professor Dr. Yisehak Kechero taught animal nutrition and feed sciences in the Department of Animal Sciences at Arba Minch University. He has written more than 60 academic publications about animal nutrition and feed sciences.

Asrat Guja

Asrat Guja is an assistant professor and researcher at Arba Minch University, Department of Animal and Range Sciences. He had a wide experience in dairy animal research.

References

- Abera, M., Tolera, A., & Assefa, G. (2014). Feed resource assessment and utilization in Baresa watershed, Ethiopia. International Journal of Science and Research, 3(2), 66–17.

- Alemnesh, Y., Mitiku, E., & Kibebew, B. (2020). Current status of camel dairy processing and technologies: A review. Open Journal of Animal Sciences, 10(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojas.2020.103022

- Alemu, D., Tekletsadik, E., Yirga, M., & Tareke, M. (2019). Feed resources potential and nutritional quality of major feed stuffs in Raya Kobo district, North Wollo zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 3(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijast.20190301.13

- Alkali, H. A., Muhammad, B. F., Njidda, A. A., Abubakar, M., & Ghude, M. I. (2017). Relative forage preference by camel (Camelus dromedarius) as influenced by season, sex and age in the Sahel zone of north western Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 12(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2016.11947

- Asmare, B., Mekuriaw, Y., & Asmare, B. (2017). Assessment of livestock production system and feed balance in watersheds of North Achefer district, Ethiopia. Journal of Agriculture and Environment for International Development, 111(1), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.12895/jaeid.20171.574

- Ayele, J., Tolemariam, T., Beyene, A., Tadese, D. A., & Tamiru, M. (2021). Assessment of livestock feed supply and demand concerning livestock productivity in Lalo Kile district of Kellem Wollega zone, Western Ethiopia. Heliyon, 7(10), 08177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08177

- Ayele, J., Tolemariam, T., Beyene, A., Tadese, D. A., & Tamiru, M. (2022). Biomass composition and dry matter yields of feed resource available at Lalo kile district of Kellem Wollega Zone, Western Ethiopia. Heliyon, 8(2).

- Babege, K., Sale, W., & Latamo, L. (2021). Potential of camel production and management practices in Ethiopia: Review. Journal of Dryland Agriculture, 7(5), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.5897/JODA2020.0070

- Berhanu, D., Melka, Y., & Furo, G. (2022). Determinants of the adaptation mechanisms to the impacts of rangeland degradation: A case of Yabello district, southern Ethiopia. Journal of Forestry and Natural Resources, 1(2), 54–67. https://journals.hu.edu.et/hujournals/index.php/jfnr/article/view/257/

- Borana zone Agriculture office. (2022). Livestock development unit, un published annual report. Yabello.

- Bulale, A. I. (2000). Smallholder dairy production and dairy technology adoption in the mixed farming system in Arsi highland.

- Derara, A., & Bekuma, A. (2020). Study on livestock feed resources, biomass production, feeding system and constraints of livestock production in relation to feeds in Weliso district, South West Shoa zone, Ethiopia. Open Access Journal of Biogenetic Science and Research, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.46718/JBGSR.2020.05.000113

- Duguma, B., & Janssens, G. P. (2021). Assessment of livestock feed resources and coping strategies with dry season feed scarcity in mixed crop–livestock farming systems around the gilgel gibe catchment, Southwest Ethiopia. Sustainability, 13(19), 10713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910713

- FAO. (1986). Forestry department. Forest resources division, and agriculture organization of the United Nations. Forest resources division. Databook on endangered tree and shrub species and provenances (Vol. 77). Food & Agriculture Org.

- FAO. (1987). The State of Food and Agriculture. FAO Agriculture Series, no. 21,

- Faye, B. (2020). How many large camelids in the world? A synthetic analysis of the world camel demographic changes. Pastoralism, 10(25). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-020-00176-z

- Habte, M., Eshetu, M., Legesse, A., Maryo, M., & Andualem, D. (2020). Land use/cover change analysis and its implication on livestock feed resource availabilities in southeastern rangeland of Ethiopia. Authorea Preprints. https://doi.org/10.22541/au.160157507.76047878

- Hassan, H., Beyero, N., & Bayssa, M. (2020). Estimation of major livestock feed resources and feed balance in Moyale district of Boran zone, southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 11(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2019.0623

- Hassen, G., Abdimahad, K., Tamir, B., Ma’alin, A., & Amentie, T. (2022). Identification and chemical composition of major camel feed resources in Degahbur district of Jarar zone, Somali Regional State, Ethiopia. Open Journal of Animal Sciences, 12, 366–379. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojas.2022.123028

- Hidosa, D., & Tesfaye, Y. (2018). Assessment study on livestock feed resource, feed availability and production constraints in Maale Woreda in South Omo zone. Journal of Fisheries Livestock Production, 6(2), 269. https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-2608.1000269

- Jiso, R., & Guja, Y. K. A. (2022). Characteristics and determinants of dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) production in Borana Plateau, Ethiopia. Research on Humanities & Social Sciences, 12(13), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.7176/RHSS/12-13-03

- John, G. M., & Peter, D. L. (2019). Land use and tenure insecurity in the drylands of Southern Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(6), 1307–1324. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1469745

- Kearl, L. C. (1982). Nutrient requirements of ruminants in developing countries. International Feedstuffs Institute. Utah State University.

- King, J. M. (1983). Livestock water needs in pastoral Africa in relation to climate and forage. International Livestock Centre for Africa.

- Kochare, T., Tamir, B., & Kechero, Y. (2018). Livestock-feed balance in small and fragmented land holdings: The case of wolayta zone, southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Livestock Production, 9(7), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLP2017.0430

- Madalcho, A. B., Tadesse, B. A., Gebeyew, K., & Gebresilassie, G. (2019). Camel feed characterization of Ethiopian Somali region rangelands through traditional knowledge. Journal of Agriculture and Ecology Research International, 19(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.9734/JAERI/2019/v19i330083

- Mamo, B., Mengistu, A., & Shenkute, B. (2023). Feed resources potential, and nutritional quality of major feed stuffs in the three agro-ecological zone of mixed farming system in Arsi zone, Ethiopia. Asian Journal of Research Animal Veterinary Science, 6(3), 241–252.

- Mengistu, D., Tefera, S., & Biru, B. (2020). Pastoral farming system and its temporal shift: A case of Borana zone, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 16(9), 1233–1238. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2018.13847

- Mirkena, T., Walelign, E., Tewolde, N., Gari, G., Abebe, G., & Newman, S. (2018). Camel production systems in Ethiopia: A review of literature with notes on MERS-CoV risk factors. Pastoralism, 8(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-018-0135-3

- Muluneh, B., Shiferaw, D., Teshome, D., Al-Khaza’leh, J., & Megersa, B. (2022). Constraints and incidence of camel calf morbidity and mortality in Borana rangeland, southern Ethiopia. Journal of Arid Environments, 206, 104841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2022.104841

- Raju, J., Reddy, P., Reddy, A., Kumar, C., & Hyder, I. (2017). Livestock feed resources in surplus rainfall agro ecological zones of Andhra Pradesh: Requirement, availability and their management. International Journal of Livestock Research, 7(2), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.5455/ijlr.20170209071714

- SPSS (Statistical Packages for Social Sciences). (2017). SPSS (version 25). Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) INC.

- Von Carlowitz, P. G. (1984). Multipurpose trees and shrubs, opportunities and limitations. The establishment of a multipurpose tree data base. ICRAF Working Papers (ICRAF). No. 17.

- Yemane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Yisehak, K., & Janssens, G. P. (2013). Evaluation of nutritive value of leaves of tropical tanniferous trees and shrubs. Livestock Research Rural Develop, 25(2). https://journals.hu.edu.et/hujournals/index.php/jfnr/article/view/257