Abstract

Social surveys were conducted for a duration of 3 months to collect information about cashew producers, their farms and production characteristics, identify their constraints in the cashew production in four villages of each of the South Soudanian and North soudanian zones. Statistical significance is recorded according to climatic zones at 5% probability. More than 60%, 76%, 77% and 94% of cashew producers are 40–60 years old, unschooled, male and autochthons, respectively. The seedling sources of planting material are varied and are statistically different with P = 9.18e−4. The cashew plants spacing, the pesticides used for inter-crops treatment and A. terebrans and D. trifasciata management are significantly different according to climatic zones with respective probabilities as P = 0.05, P = 7.90e−4 and P = 5.93e−3. Too many constraints are encountered to cashew producers and are varying significantly (P = 2.61e−4). Cashew total nuts yield and yield loss estimated by insects and pests infestation are weakly correlated to the number of cashew farms, cashew nuts production time, the attack time of A. terebrans or D. trifasciata and cashew orchards age in the Soudanian and Soudano-Sahelian zones with a probability < 0.05. The results of this study provide an important database for efficient production of cashew nuts and baseline for policy-makers and planers for decision-making in Burkina Faso.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Annual crops and trees crops are contributing to agriculture sustainability for human well-being. Agroforestry is so far addressing environmental problems and contributing to economic income generation for local communities and the entire nation. Cashew has a wide range of usage from environmental management to economic income generation and then suitable for national development. Identifying the associated constraints and management practices are essential for the development of an effective production strategy. Cashew nuts productivity is better in young plants where inter-cropping can be practiced than the old trees that are more suitable for A. terebrans attack which is the most damaging pest of old trees. Insecticide treatments and mechanic control (killing) are useful for D. trifasciata however physical control (suffocation, burning) is appropriated for A. terebrans. Specific insecticides for cashew pests treatment could be necessary instead of cotton insecticides use which are contributing to the selection of resistant population of insects.

1. Introduction

The population of Burkina Faso is on increasing trend, with main activities for livelihood being subsistence’s agriculture, animal breeding, trade and fishing, but the principal activity remains agriculture (RGPH, Citation2022). This increase will require an increase in food production globally and diversification in Burkina Faso varying according to the periods of the season (Lourme-Ruiz et al., Citation2016), although in certain rural zones in West Africa, there was an increase in subsistence agriculture in Mali (Dury & Bocoum, Citation2012) and Burkina Faso (Parent et al., Citation2002) which is always correlated with young children diseases. Food crops and trees crops are complementary for agriculture sustainability providing food and income for communities (Nair, Citation2021), contributing to the economy of countries (Azam-Ali & Judge, Citation2006) and providing benefits for human wellbeing and services for environment management (Asbojornsen et al., Citation2012; Etongo et al., Citation2015; Kroma & Lamien, Citation2017). In Burkina Faso, agriculture contributes to 34% of the gross domestic product (USAID, Citation2012), more than 60% of the population works in agriculture and so far the economy of the country is essentially dependent on rural population (RGPH, Citation2022). Cashew plant provides nuts and apples for growers that have several useful nutrients for human body and is also able to compensate for the lack of nutrients in children (Abrego et al., Citation2018; Semporé et al., Citation2021). This plant is becoming a primordial plant in producing countries and particularly in Burkina Faso which was the sixth exporters of the top 10 countries in West Africa (Bojang & Gibba, Citation2021) and was a source of economic income to 45.5% of producers (Belem, Citation2017). In Burkina Faso, efforts are made by plant breeders to provide good-quality planting materials, improving nut yields (Bognina et al., Citation2019; Konate et al., Citation2022; Tarpaga et al., Citation2020), pathologists identifying the associated diseases to cashew plants (Wonni et al., Citation2017) and entomologists are working on insects attack in cashew plantation or the associated pests in cashew orchards (Nébié et al., Citation2022). Despite these efforts, studies have not been done on constraints encountered by producers in cashew production and management practices in order to elaborate baseline on cashew production in Burkina Faso. The knowledge of constraints and especially insects management practices is essential for the development of an effective production strategy. Therefore, the study aims to characterize the cashew production practices among farmers, determine the insects and pests management strategies in cashew orchards and farmers constraints in cashew production in two agroecological zones of Burkina Faso.

2. Study area

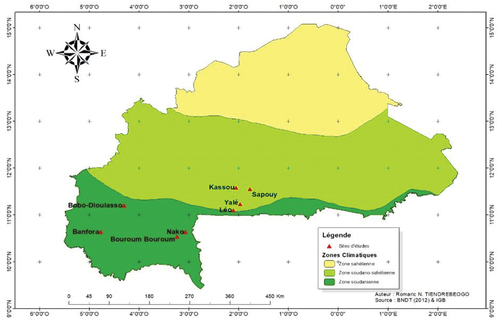

The study was conducted in the southern part of Burkina Faso in two agroecological zones (Figure ), namely, South-soudanian (Soudanian zone) and North-soudanian (Soudano-Sahelian zone), having rainfall more than 900 mm and between 600 and 900 mm/year, respectively (Ibrahim, Citation2013). Although cashew trees could be found in each region of Burkina Faso, more commercial cultivation was seen in these climatic zones within four regions: Cascades, Centre Ouest, Hauts bassin and Sud Ouest (Belem, Citation2017; Wonni et al., Citation2017) in the southern and western parts of the country with more than 95% of the national cashew raw nuts production (Audouin & Gonin, Citation2014). This part of the country has the ideal land where the population is mostly working in subsistence agriculture with trees crops production as cashew and mango (Dembele, Citation2014).

3. Method

A structured questionnaire was used for this social surveys. Preliminary investigation was done in farms with the help of cashew growers in two regions to identify any issues or lacking content. We collected data on socio-demographic variables of participants, information about their cashew farms and farming practices, the age of cashew plantations, the cashew nuts total yield, the associated constraints, the estimated nuts yield loss caused by pests in farms, Apate terebrans and Diastoscera trifasciata infestation in orchards (images and damages of both have been shown to them), their control practices and the types of pesticides used in cashew plantation by showing their container or a photograph. The questionnaire was designed to take a participant roughly 25 minutes to finish and was presented in all the four regions: three regions in the Soudanian zone and only one region in the Soudano-Sahelian zone where cashew is produced. Each respondent was aware of the scope of the project, the anonymity and protection of participant identity, the consent to participate in the study by showing the cover letter of the project and the utilization of participant data strictly for the purposes of academic research. In each of the climatic zones, four villages were randomly chosen with at least 20 to 100 km far from each other with cashew nuts local organization and 20 respondents having cashew farm were interviewed by ourselves physically. Again, focused group discussion with cashew growers in their local organization were also investigated to check the accuracy of the surveyed responses. The farmers local organization provides local services for farmers including technical advice and sale of farming materials. In a total, 160 respondents have been interviewed in this survey based on the region cashew is produced and according to climatic zones.

4. Data analysis

Data processing is done using R software version 4.1.3 (R Core Team, Citation2022). Tables and graphics are established using the package ggstatsplot of R to get the statistical details according to climatic zones and between the subgroups of each parameter of categorical and continuous variables data (Patil, Citation2021). Pearson correlation is done with some of the continuous variables. For statistical decision-making, 0.05 is kept as a significance level.

5. Results

5.1. Distribution of sociodemographic data of cashew growers

Cashew orchards are owned mainly by men than women (95% vs 5%) in the Soudanian zone and (96.25% vs 3.75%) in the Soudano-Sahelian zone. The producers are mainly autochthons (100%) in the Soudanian zone but autochthons (88.75%), migrants (6.25%) and officials (1.25%) in the Soudano-Sahelian zone (Table ). Most of the producers are unschooled in formal education, 73.75% (in Soudanian zone) vs 80% (in Soudano-Sahelian zone). Their age is varying statistically from 27 to 80 years, where 72.5% vs 48.75% of the cashew producers (n = 97, P value = 0.05) are in the interval of 40–60 years and 13.75% vs 41.25% (n = 44, P value = 9.11e−4) are in the interval of 60–80 years in the Soudanian and Soudano-Sahelian zones, respectively (Table ).

Table 1. Statute and gender data of cashew producers in the two zones

Table 2. Age distribution and education levels of cashew producers in the study areas

5.2. Cashew nuts production and orchards characteristics within agroecological zones

5.2.1. Sources of cashew planting materials to producers

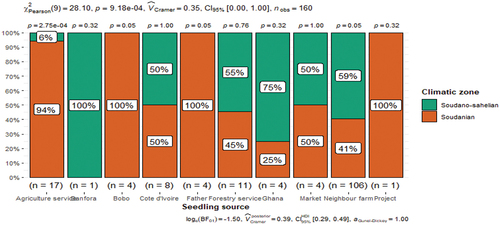

The planting materials sources varied statistically according to climatic zones (n = 160, P = 9.18e−4). About 94% of cashew nuts producers in the Soudanian zone vs 6% in the Soudano-Sahelian zone were getting cashew seedling materials from agriculture services (n = 17, P = 2.75e−4), 100% (Soudanian zone) vs 0% (Soudano-Sahelian zone) from Bobo, either from their father’s farm (n = 4, P = 0.05), and 41% (Soudanian zone) vs 59% (Soudano-Sahelian zone) from their neighbor’s farms (n = 106, P = 0.05) (Figure ).

5.2.2. Cashew plants spacing in orchards

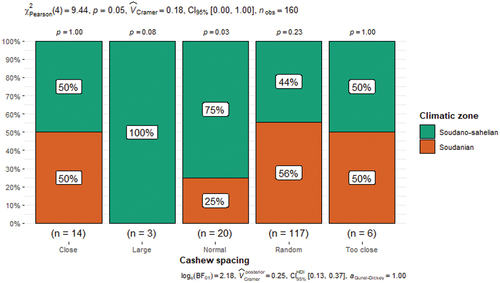

Cashew plants spacing is varying significantly according to climatic zones (n = 160, P = 0.05) (Figure ). Indeed, 75% of producers in the Soudanian zone vs 25% in the Soudano-Sahelian zone were planting cashew plants taking account of the normal spacing of cashew plants in the guideline which is at 10 m, respectively, according to climatic zones (n = 20, P = 0.03) which is not to 87.5% of producers.

5.2.3. Cashew total yield average to producers

Cashew total yield is mostly ranked between 0 and 2,000 kg to 90% of cashew producers (Table ). This total yield can reach 8,000–10,000 kg to some of them in the Soudanian zone. According to climatic zones, this average is statistically significant (n = 160, P = 7.75e−3). In addition, the average of yield between 2,000 and 4,000 kg and between 4,000 and 6,000 kg is also statistically different (n = 8, P = 0.03; n = 5, P = 0.03), respectively, according to the climatic zones.

Table 3. Distribution of cashew total yield average according climatic zones

5.2.4. Annual plants in association with cashew orchards

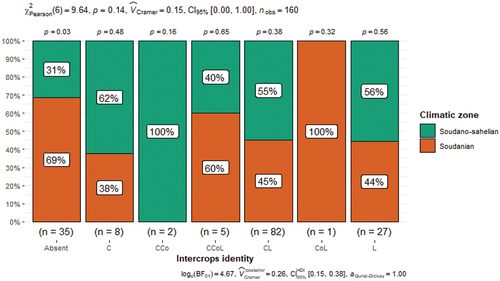

Cashew producers are mainly doing inter-cropping for subsistence farming using several annual crops in cashew orchards (78.125%) but in monoculture to 22% of producers (Figure ). The inter-crops in cashew orchards are not significantly different according to climatic zones. However, the subgroup of cashew producers practicing monoculture is varying significantly according to climatic zones (n = 35, P = 0.03).

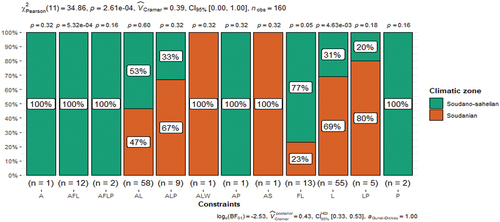

5.2.4. Constraints encountered by producers in cashew production

In cashew production, too many constraints are encountered by producers. These constraints include less marketing price per kg of nuts, animal divination, insects and pests infestation, diseases, price variability; no government role, no support, no intervention, bad organization; absence of land; fire; low production and water. These constraints are varying statistically according to climatic zones (n = 160, P = 2.61e−4). Thus, 23% of cashew producers in the Soudanian zone vs 77% in the Soudano-Sahelian zone are facing constraints like fire, low price, animal divination, insects and pests infestation, diseases and price variability (FL) as main constraints (n = 13, P = 0.05) and 69% (Soudanian zone) vs 31% (Soudano-Sahelian zone) are having low price, animal divination, insects and pests infestation, diseases and price variability (L) as their main constraints (n = 55, P = 4.63e−3) (Figure ).

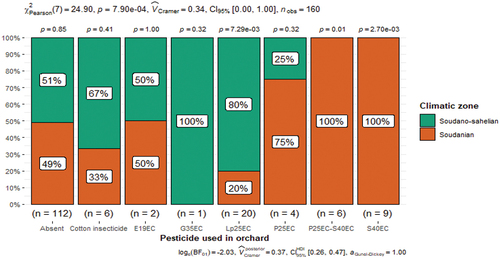

5.2.6. Pesticides used in cashew orchards for annuals plants treatments

Several pesticides are used in cashew orchards for insects and pests management. Most of the cashew producers (70%) were not using pesticides for annual plants treatments looking at the types of inter-crops, which represent 51% and 49% of producers in the Soudano-Sahelian and Soudanian zones, respectively. According to climatic zones, these pesticides are statistically significant and different (n = 160, P = 7.90e−4) (Figure ). Indeed, 20% of cashew producers in the Soudanian zone vs 80% in the Soudano-Sahelian zone are using Lp25EC (Lambdaf plus 25 EC) and 100% (Soudanian zone) vs 0% (Soudano-Sahelian zone) are using P25EC-S40EC (Pacha 25 EC and Somon 40 EC) and even S40EC (Somon 40 EC) with respective pesticides probabilities as n = 20, P = 7.29e−3; n = 6, P = 0.01; n = 9, P = 2.70e−3.

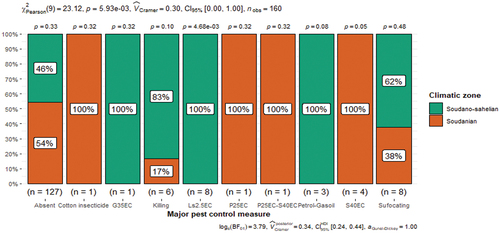

5.2.7. Pesticides and practices used for Apate terebrans and Diastoscera trifasciata management

From the strategies used to control Apate terebrans and Diastoscera trifasciata, cashew producers are using several insecticides (Figure ). Most of the cashew producers (79.38%) were not aware of any control measure of these pests (46% in Soudano-Sahelian vs 54% Soudanian zone), although some control measures were available to some of them which varies statistically according to climatic zones (n = 160, P = 5.93e−3). Then, 100% of producers in the Soudanian zone vs 0% in the Soudano-Sahelian zone are using Ls2.5EC (Lambdaf super 2.5 EC) (n = 8, P = 4.68e−3) and the same proportion with S40EC (Somon 40 EC) (n = 4, P = 0.05).

6. Correlation between cashew nuts total yield and yield loss estimated across some continuous variables

Cashew nuts total yield is weakly correlated with the number of cashew farms (P = 0.004), the time of nuts production (P = 9.683e−5) and cashew orchards age (P = 4.515e−5) in the Soudanian zone and, respectively, P = 0.0237, P = 6.769e−5 and P = 0.0001 in the Soudano-Sahelian zone. In addition, nuts yield loss estimation is also weakly correlated with cashew orchards age (P = 0.0001), the attack time (P = 5.659e−10), nuts production time (P = 0.0002) and cashew farms (P = 0.0036) in the Soudanian zone and, respectively, P = 9.775e−10, P = 2.699e−09, P = 6.303e−11 and P = 0.0349 in the Soudano-Sahelian zone (Table ).

Table 4. Correlation within some continuous variables

7. Discussion

7.1. Socio-demographic characteristics

Most of the cashew producers are autochthon (88.75%), male (77.5%) and in the age group of 40–60 years (60.625%); 11.875% have primary education level, 11.25% secondary school level and 76.875% are unschooled in formal education. Only female (4.375%) had 1–5 years of experience in cashew nut processing. This is in agreement with the results of Dembele (Citation2014), Kotchofa (Citation2014) and Belem (Citation2017) that illustrated that cashew plantations were mainly belonging to autochthon men than women of 32–84-year-old age group and did not have high education level.

7.2. Cashew plants spacing, intercrops and treatment

Most of the cashew plants are randomly planted (to 65% of cashew producers), and 11% of them are planting their cashew plants at a spacing interval less than recommended given high density of plants per ha in Burkina Faso. According to Belem (Citation2017), cashew plants density was around 145/ha, and the normal and large spacing intervals were for inter-cropping with annual plants (Kekele, Citation2015), demonstrating that subsistence agriculture was being practiced in Burkina Faso (Parent et al., Citation2002) where more than 78% of cashew producers were doing inter-cropping in cashew plantations. Plants spacing is a factor contributing to insects and pests impacts on the crops. This observation was done on sunflower having low spacing, causing higher damage to the plants and a reduction in the seed yield (Akessé et al., Citation2020). Regarding the inter-crops in cashew orchards, producers are using insecticides or not taking account of the types of crops and infestation by pests.

7.3. Major insects and pests damages presence and pesticides utilization

Results from this survey showed that the cashew stem girdler (D. trifasciata) and cashew borer (A. terebrans) damages are present at 7.5% and 20.625% infestation levels, respectively, in cashew orchards and are considered the major pests of cashew plants in Burkina Faso. Apate terebrans and D. trifasciata infestation has been reported and linked to only non-managed orchards (Asogwa et al., Citation2011). According to Ouali N’Goran et al. (Citation2020), D. trifasciata infestation levels varied according to years, phenological stages of cashew and periods. It had also been reported that D. trifasciata was linked to orchards age (Diabate & Tano, Citation2020). In addition, in this survey, adults of D. trifasciata infestation were not found girding cashew trees because of the use of its outside feeding habit where it could be easily controlled mechanically by producers. Management practices and orchards age could explain the differences of the damages presence of the two insects pests in term of percentage in farms. Consequently, 72.5% of cashew orchards had more than 5 years old. Again, regarding the use of different types of pesticides in orchards for annual plant treatments (30% of producers) and these pests management (20.625% of producers), the feeding habits of the insect had played a great role: feeding outside the tree for D. trifasciata (Asogwa et al., Citation2011; Binyason et al., Citation2020) and inside the tree for Apate terebrans (Agboton et al., Citation2017). Indeed, Akessé et al. (Citation2020) have demonstrated that mechanic control was giving the best results than insecticides for D. trifasciata control. Producers were using insecticides from Ghana without any information regarding their health impacts in orchards to protect cashew plants from pests which was a contrast for false fruits/juice consumption (Kotchofa, Citation2014). In contrast, D. trifasciata was not found in cashew orchards in Burkina Faso by Nébié et al. (Citation2022), and only A. terebrans was observed; therefore, D. trifasciata was not considered as a threat. In fact, the area covered by their research was only based in one region of cashew-producing region (Hauts-bassins) which was ranked third in cashew nuts production in Burkina Faso (Kotchofa, Citation2014), based only on four sanitized cashew orchards and furthermore where cashew orchards were too old (>14 years).

7.4. Constraints

Biotics disorders such as insects and pests infestation, diseases and governmental insufficiency are the main constraints of cashew production in Burkina Faso (96.9% of cashew producers). These constraints were reached out as poor-quality planting materials, the age of cashew in orchards and low yields (Audouin & Gazull, Citation2014; Etongo et al., Citation2015) in Burkina Faso. In addition, lack of land, infrastructures and commercialization were some constraints of mango and cashew production, with the high price of fertilizers, pests infestation, bad organized or unorganized marketing system and the decrease in rainfall. In Burkina Faso, fruits production was linked with the rainy season, thus influenced by climate change (Kekele, Citation2015). It has been projected that there will be a decline in cashew production in next 5 years in countries such as Nigeria, Togo, Senegal and Burkina Faso due to a reduction in the land under cashew cultivation and an increase in pests and disease expansion, coupled with a decline in genetic improvement and poor extension services (Kolliesuah et al., Citation2020). Climatic factors and management strategies could explain the differences of constraints regarding agroecological zones where cashew is planted.

8. Conclusion

Cashew production in Burkina Faso is still increasing in areas for best incomes generation, even though producers are old, unschooled and autochthons. Orchards characteristics vary in term of age, area and plants spacing. The origin of planting material was multiple, and mostly these plants are in monoculture/inter-cropping with some annual plants. Several constraints are encountered by cashew producers, and some pesticides are used for management that were linked with insects and pests infestation and inter-crops protection. Regarding the climate change that could impact the vulnerable population, efforts could be made to protect this plant for best income generation to local communities.

Effective management strategies and development of potent pesticides for A. terebrans and D. trifasciata control would be necessary to overcome the identified constraints and prevent the threatened cashew extinction in Burkina Faso.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Naamwin Irkoum Zephirin Somda

Somda This paper seeks with environment management program activities. Three authors have contributed to the finalization of the work. SOMDA Zephirin research activities are related to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), Social Environment Assessment (SEA), climate change mitigation, integrated pests management, crops protection, insect ecology and biology and agriculture sustainability.

Juliana Amaka Ugwu

UGWU Juliana Amaka research activities are linked with Insect ecology and biology, Fruit fly monitoring and control, Use of botanicals (plant extracts) for pest control, Vegetable insect pest management, Forest insect ecology and control and Integrated pest management.

Madjelia Cangré Ebou Dao

Madjelia Cangré Ebou Dao research activities are related to the Promotion of best agroforestry practices to protect and restore ecosystems contributing to adaptation to climate change; Promotion of organic farming promoting sustainable production, Integrated Pests management of tree crops.

References

- Abrego, J., Plaza, D., Luño, F., Atienza-Martínez, M., & Gea, G. (2018). Pyrolysis of cashew nutshells: Characterization of products and energy balance. Energy, 158, 72–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.06.011

- Agboton, C., Onzo, A., Korie, S., Vidal, M., & Tamo, S. (2017). Spatial and temporal infestation rates of Apate terebrans (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) in cashew orchards in Benin, West Africa spatial and temporal infestation rates of Apate terebrans (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) in cashew orchards in Benin, West Af. African Entomology, 25(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.4001/003.025.0024

- Akessé, E. N., Mauricette, S.-W., Goran, O. N., Minhibo, Y. M., Misler, K., & Koné, D. (2020). Efficacité d ’ une lutte mécanique associée au biopesticide Neco 50 EC dans le contrôle des adultes de Diastocera trifasciata (Coleoptera : Cerambycidae), ciseleur des branche s d ’ anacardier en Côte d ’ Ivoire Efficacy of mechanical control associated. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 14(3), 1038–1051. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v14i3.30

- Asbojornsen, H., Hernadez-Santana, V., Liebman, M. Z., Bayala, J., & Chen, J. (2012).Targeting perennial vegetation in agricultural landscapes for enhancing ecosystem services. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170512000385

- Asogwa, E. U., TCN, N., & H, A. T. (2011). Distribution and damage characteristics of analeptes trifasciata Fabricius 1775 (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) on cashew (Anacardium occidentale Linnaeus 1753) in Nigeria. Agriculture & Biology Journal of North America, 2(3), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.5251/abjna.2011.2.3.421.431

- Audouin, S., & Gazull, L. (2014). Les dynamiques d ’ un système d ’ innovation à travers le prisme des diffusions spatiales. Le cas de l ’ anacarde au Sud-Ouest du Burkina Faso. In L’Espace geographique. http://www.cairn.info/revue-espace-geographique-2014-1-page-35.htm

- Audouin, S., & Gonin, A. (2014). L’anacarde : produit de la globalisation, moteur de la territorialisation, l’exemple du Sud du Burkina Faso. EchoGéo, 29(29), 13. https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.13926

- Azam-Ali, S. H., & Judge, E. C. (2006). Small-scale cashew nut processing. http://www.fao.org/ag/ags/agsi/Cashew/Cashew.htm

- Belem, B. C. D. (2017). Analyse des déterminants de l’adoption des bonnes pratiques de production de l’anacarde au Burkina Faso. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11794/27700

- Binyason, S. A., Baka, S. D., Marchelo, P. W., Duku, J. S., & Ogwaro, A. (2020). The discovery of a green wood beetle. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 10, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.17265/2161-6256/2020.04.003

- Bognina, A., Guira, M., & Yameogo, J. T. (2019). Essai de multiplication par greffage d ’ une accession d ’ anacardier à grosses pommes à la Station de recherche de Banfora au Burkina Faso Résumé. Afrique SCIENCE, 15(4), 156–168.

- Bojang, B., & Gibba, A. (2021). The global competitiveness of West African cashew exporters the global competitiveness of West African cashew exporters. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 6, 1084–1092. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357222152%0

- Dembele, A. S. (2014). Étude socio-économique des systèmes agroforestiers (saf) à manguier et à anacardier dans le terroir de kotoudéni (province du Kénédougou, Burkina Faso). https://beep.ird.fr/collect/upb/index/assoc/IDR-2014-DEM-ETU/IDR-2014-DEM-ETU.pdf

- Diabate, D., & Tano, Y. (2020). Attaque de Analeptes trifasciata Fabricius 1775 (Coleoptera : Cerambycidae) en culture d’anacarde (Anacardium occidentale). Revue Internationale Des Sciences et Technologie, 36, 1–10. http://www.revist.ci

- Dury, S., & Bocoum, I. (2012). Le « paradoxe » de Sikasso (Mali) : pourquoi « produire plus » ne suffit-il pas pour bien nourrir les enfants des familles d’agriculteurs? Cah. Cahiers Agricultures, 21(5), 334–336. https://doi.org/10.1684/agr.2012.0584y

- Etongo, D., Djenontin, I. N. S., Kanninen, M., & Fobissie, K. (2015). Smallholders’ tree planting activity in the Ziro Province, southern Burkina Faso: Impacts on livelihood and policy implications. Forests, 6(12), 2655–2677. https://doi.org/10.3390/f6082655

- Ibrahim, B. (2013). Caractérisation des saisons de pluies au Burkina Faso dans un contexte de changement climatique et évaluation des impacts hydrologiques sur le bassin du Nakanbé To cite this version : HAL Id : tel-00827764 Docteur ès SCIENCES contexte de changement climat. Universite Pierre et Marie Curie. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00827764

- Kekele, A. (2015). Dynamique des paysages ruraux et systeme de production dans la commune de Orodara (Ouest du Burkina Faso). Universite Paris I Pantheon-Sorbonne. https://www.documentation.ird.fr/hor/fdi:010068448

- Kolliesuah, N. P., Saysay, J. L., Zinnah, M. M., Freeman, T. A., & Chinenye, D. (2020). Trend analysis of production, consumption and export of cashew crop in West Africa. African Crop Science Journal, 28(1), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.4314/acsj.v28i1.14S

- Konate, M., Tarpaga, V. W., Bourgou, L., & Wonni, I. (2022). Genetic diversity assessment among 18 elite cashew tree genotypes (Anacardium occidentale L) selected in Western Burkina Faso. Plant Breeding and Crop Science, 14(March), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPBCS2021.0986

- Kotchofa, R. A. M. (2014). Contraintes et opportunités de création de valeur ajoutée dans les chaînes de transformation des fruits du karité (Vit ellaria paradoxa) et du cajou (Anacardium occident ale) dans les Provinces de la Sissili et du Houet au Burkina. http://www.laboress-afrique.org/ressources/assets/docP/Document_N0.pdf

- Kroma, S., & Lamien, N. (2017). Evation de la rentabilite de la competitivite de la chaine de valeur gomme arabique dans l’amelioration des conditions de vie des populations au sahel du Burkina Faso. Agronomie Africaine, 29(1), 29–40.

- Lourme-Ruiz, A., Dury, S., & Martin-Prével, Y. (2016). Consomme-t-on ce que l’on sème? Relations entre diversité de la production, revenu agricole et diversité alimentaire au Burkina Faso. Cahiers Agricultures, 25(6), 65001. https://doi.org/10.1051/cagri/2016038

- Nair. (2021). Tree crops ( K. P. Nair, V. G3, & M. Pankajakshy (eds.)). Springer N. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62140-7

- Nébié, K., Coulibaly, S. L. C. S., Dabiré, R. A., Sankara, F., & Zida, I. (2022). Insect fauna associated with Anacardium occidentale (Sapindales: Anacardiaceae) in the South Sudanese area of Burkina Faso, West Africa insect fauna associated with Anacardium occidentale (Sapindales: Anacardiaceae) in the South Sudanese area of Bu. Entomological Research, 45(February), 839–850. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-4576.2021.00131.6

- Ouali N’Goran, S.-W. M., Akessé, E. N., Ouattara, G. M., & Koné, D. (2020). Process of attack on cashew tree branches by and the relationship between these attacks and the. Insects, 11(456), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11080456

- Parent, G., Zagré, N., Ouédraogo, A., & Guiguembé, T. R. (2002). Les grands hydro-aménagements au Burkina Faso contribuent-ils à l’amélioration des situations nutritionnelles des enfants? Cahiers Aaricultures 2002, 11(1), 51–57.

- Patil, I. (2021). Visualizations with statistical details: The “ggstatsplot” approach. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(61), 3167. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03167

- RGPH. (2022). Cinquième Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitation du Burkina Faso. https://www.insd.bf/contenu/documents_rgph5/RapportresultatsdefinitifsRGPH2019.pdf

- Semporé, J. N., Songré-Ouattara, L. T., Tarpaga, W. V., Bationo, F., & Dicko, M. H. (2021). Comparison of proximate composition and nutritional qualities of fifty-three cashew accessions from Burkina Faso. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 12(12), 1191–1203. https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2021.1212087

- Tarpaga, W. V., Bourgou, L., Guira, M., & Rouamba, A. (2020). Caractérisation agro morphologique d ’ anacardie rs (Anacardium occidentale L.) en sélection pour le haut rendement et la qualité supérieure de noix brute au Burkina Faso Agro morphological characterization of cashew trees (Anacardium occidental L.). International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 14(9), 3188–3199. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v14i9.17

- Team, R. C. (2022). A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- USAID. (2012). Climate vulnerabilities and development in Burkina Faso and Niger. https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/climate-vulnerabilities-and-development-burkina-faso-and-niger

- Wonni, I., Sereme, D., Kassankagno, A. I., Dao, I., Ouedraogo, L., & Nacro, S. (2017). Diseases of cashew nut plants (Anacardium occidentale L.) in Burkina Faso. Advances in Plants & Agriculture Research, 6(3), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.15406/apar.2017.06.00216