?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Rice is the pillar of the Malagasy diet. This paper provides empirical insights into which rice attributes are preferred in rural Madagascar, taking both producers’ and consumers’ perspectives into account. We conducted an original, interview-based household survey for 596 randomly selected rice-producing households in Vakinankaratra region of Madagascar. As producers, the dominant preference was for high productivity, followed by early maturity, and drought resistance. As consumers, qualities such as cleanliness and purity were important, and sweetness was expressly preferred. We found that consumers’ preferences were diverse, so we employed hierarchical cluster analysis and two-step multiple comparisons for further understanding. Cluster analysis categorized households into four groups, characterized by the respondents’ nature of preferences as consumers: (I) quality, (II) cooking, (III) appearance and texture, and (IV) flavor. Though the increase in productivity remains important, understanding consumer preference is also critical because it is transmitted through markets and affects producers. In addition, we found several unique characteristics of the Malagasy people, such as they tend to prefer local, non-scented rice while many African people prefer imported rice with aroma. Rice preference varies among countries, and this study’s comprehensive findings on Malagasy rice preferences contribute to the development of targeted rice-breeding and marketing strategies in Madagascar.

1. Introduction

Rice is one of the most important staple foods, feeding more than three billion people in the world (Yadav & Kumar, Citation2018). To the people of Madagascar, rice carries a particular significance. They have one of the highest per capita consumption of rice in the world, accounting for approximately 115 kg/year per capita in 2022 (United States Department of Agriculture, Citation2023). The most produced crop in Madagascar is also rice, with more than 4 million tons produced in 2021 (FAOSTAT, Citation2023).

In terms of preference, rice is by no means a “one-size-fits-all” crop (Calingacion et al., Citation2014). Rice preference varies significantly by country and region. Most of the previous studies on producers’ preference have shown that heavy yields are desired, as well as disease resistance, drought tolerance, high market value, early maturity, and aroma (Suvi et al., Citation2021). When it comes to consumers, favored traits can range widely and include taste, price, aroma, ease of cooking, swelling capacity, texture (stickiness or hardness), storage, origin, cleanliness (no dirt or stones), nutritional components, color, size, and shape. In addition to these internal aspects which are related to the properties of rice itself, many external factors may further influence consumers’ food choices including social norms, consumer nutrition knowledge, lifestyle factors such as convenience, personal preferences or tastes, attitudes, culture, and beliefs (Wood et al., Citation2017; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (Citation2017). The importance of these factors depends on the local environment and population.

Domestic rice produced by rural small farmers is mostly for subsistence purposes, with the opportunity to sell at the market. The producers, who decide which rice varieties are produced, desire to increase the production to ensure their household food security and profit. As consumers pay a premium for higher quality (Sakurai et al., Citation2015), their preferences might also affect producers’ profit maximization through market prices. Also, as rural farmers are generally the first to consume the rice they produce, their preferences regarding the variety of rice to be produced might intrinsically depend on their preferences as consumers (Hossain et al., Citation2015). Thus, consumers’ and producers’ preferences interact in diverse ways. However, most preceding studies have completely separated producers’ and consumers’ rice preferences. Studies have rarely utilized the method of asking farmers, through interviews or surveys, about their preferences as producers and as consumers.

In addition, while many studies on producers’ or consumers’ rice-trait preferences have been conducted in Asia (Hossain et al., Citation2015; Laborte et al., Citation2015) and West Africa (Jin et al., Citation2020; Misiko, Citation2013), there is limited existing research focused on Madagascar, even though rice is a dominant Malagasy staple food. The characteristics of rice favored by Malagasy people has received insufficient attention, but such knowledge could contribute to the development of the rice varieties in demand by locals. Therefore, we target rural rice farmers in the Central Highlands of Madagascar in this study. We investigate the Malagasy farmers’ rice trait preferences from both the producers’ and consumers’ perspectives, with the aim of applying our findings to Madagascar’s rice-breeding programs.

1.1. Rice in Madagascar

Rice is the pillar of the Malagasy diet. Regardless of their economic status (Rakotosamimanana et al., Citation2015), the Malagasy people are great consumers of rice. A typical Malagasy meal is composed of a large quantity of rice, accompanied by a side of boiled vegetables and, occasionally, meat. Rice contributes to a high caloric intake, accounting for almost half the intake at the national level (Shiratori et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, the Malagasy people’s nutrient supply is not ideally balanced; their high dependence on rice results in, for example, vitamin A or calcium deficiency (Shiratori & Nishide, Citation2018).

Madagascar struggles with poverty and malnutrition; with a markedly high poverty rate; 80.7% of the population lived on less than $2.15 per day in 2012 (World Bank, Citation2022a). The stunting rate includes about half of Madagascar’s children under five (Local Burden of Disease Child Growth Failure Collaborators, Citation2020). In addition, Madagascar is said to be one of the African countries most severely affected by climate change (World Bank, Citation2022b). One-third of Malagasy households experience food insecurity throughout the year, while recurrent cyclones, droughts, and flooding prevent the building of resilience within rural communities (Food and Agricultural Organization, Citation2017).

Madagascar has more than 1.3 million ha of rice planting area, of which 78.8% is irrigated, 8.4% is rain-fed, and 12.9% is slash-and-burn (World Food Programme (World Food Programme, Citation2019). About 85% of Malagasy farmers grow rice (Global Rice Science Partnership, Citation2013). The main harvest season stretches from May to June, although a second harvest is not uncommon. Agricultural productivity in rice and other key crops remains low in Madagascar due to the use of traditional cultivation methods (WFP & United Nations Children’s Fund, Citation2011), soil infertility, and inefficient use of fertilizer. The average rice yield is approximately 2.5 t/ha (WFP, Citation2019), and the increase in production has been mainly due to an expansion of cultivation areas, rather than improved yield (UNICEF, Citation2011).

While most domestic rice is produced by small farmers for subsistence purposes, rice markets also play an important role in rice consumption. Poor rural households in Madagascar spend two-thirds of their expenditures on food, and half of it (one-third of total expenditure) on rice (UNICEF, Citation2011). Imported rice, which accounts for a maximum of 10% of the domestic demand, is available year-round in major urban markets, especially during the lean season to supplement domestically produced rice (UNICEF, Citation2011; The Famine Early Warning Systems Network, Citation2018). There are some high-quality imported varieties such as Thai jasmine, however, the share of high-grade rice is small (Sakurai et al., Citation2015). The availability of rice varieties on the market could influence Malagasy rice consumption (WFP, Citation2019).

In addition to the traditional varieties widely grown by African rice farmers, improved varieties have become available through considerable research and diffusion efforts. The National Center for Research on Rural Development in Madagascar (FOFIFA) holds more than 6,000 varieties of rice, resulting from research (WFP, Citation2019). Improved varieties have higher potential yield and/or stress tolerance, which increase rice productivity. The adoption of the improved varieties remained low in sub-Saharan Africa for some time; however, its significance increased after the 2008 food crisis and had a positive impact on farmers’ incomes (Arouna et al., Citation2017). To enhance the adoption of improved varieties, farmer participatory varietal selection (PVS) has become popular (Misiko, Citation2013). PVS involves farmers in the breeding process, thus shortening the diffusion time and allowing for direct feedback from the farmers (Tyack et al., Citation2020).

Previous studies have shown that heavy yields, early varieties with profuse tillering, and large grains are consistently the most desired selection criteria for rice in most African countries—although less-frequently mentioned characteristics could differ among countries (Gridley et al., Citation2002). In Madagascar, most farmers prefer using traditional varieties; however, improved varieties with a potential for resilience to climate change, such as X1648, X265, and NERICA, have been gaining increased appreciation (Abel-Ratovo & Razafimbelonaina, Citation2019). Breeders’ preferences can sometimes differ from farmers’ preferences. Short (dwarf) varieties, the driving force behind the Green Revolution in Asia, are normally promoted by breeders because they are more resistant to lodging. In contrast, farmers in Mali prefer tall rice varieties that are easier to harvest by hand and produce longer stalks, which are used as rice straw to build huts (Efisue et al., Citation2008). Tall varieties are also preferred by upland rice farmers in Madagascar, since the longer rice straw is a valued byproduct that can be used as fodder (Raboin et al., Citation2014).

Consumers’ rice preferences vary significantly by country and region, such as the preference for glutinous rice in Laos and its neighboring countries, short grain and low amylose varieties in Japan and Korea, aromatic rice in the Greater Mekong Subregion and India, and long grains with no scent in Europe (Calingacion et al., Citation2014; GRiSP, Citation2013; Hossain et al., Citation2015). In some countries in West Africa, imported rice has gained popularity due to its cleanliness, ease of cooking, taste, availability, and appearance (Fiamohe et al., Citation2015; Hossain et al., Citation2015; Tomlins et al., Citation2005). Malagasy consumers are sensitive to the quality of rice (Dabat et al., Citation2008), and the important quality criteria for them include the cleanliness/purity and cooking properties of the rice (WFP, Citation2019).

2. Materials and methods

From August 2018 to September 2018, we conducted interviews using surveys supplied to rural households in three districts (Mandoto, Betafo, and Antsirabe II) in the Vakinankaratra region, Central Highland, Madagascar. Within these three districts, 60 villages (fokontany) were selected to ensure wide variations in the geographical location (distance from paved roads and market access) and population among villages. The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Malagasy Ethical Committee for Science and Technology (N°014/2020-AM/CMEST/P).

In January 2018, before conducting the survey interviews, we supplied all households in these 60 villages with a census survey to establish a complete list of households. From the resulting list of 5,253 households, we randomly selected 10 lowland rice-farming households from each village. In total, the survey included 600 target households. The pretest was conducted in another rural village close to the target villages, and some unclear points and inconsistencies detected during pretest and interviewer training were corrected before starting the survey. We used a software called “Survey Solutions,” developed by the World Bank, for data collection.

Trained interviewers visited the target households to conduct face-to-face interviews, carrying a tablet terminal on which a pretested, structured questionnaire was implemented. The interviewers explained the survey content and obtained informed consent from all participating households before the survey interviews. After the survey, each interviewer uploaded the data to the server so that their supervisor could check and approve or reject them. The data rejected by the supervisor were sent back to the interviewer with specific comments, and the interviewer revisited the household to obtain the correct data and uploaded it. The supervisors approved all the data used in this study.

The survey questionnaire covered various topics, such as household demographics, crop production, food consumption, dietary habits, and preferences. The aim was to interview the person who seemed to hold the highest level of responsibility in the household or the person preparing the food for the household. If these people were unavailable, we returned to conduct the interview at a later time. If upon our return, they were unable to give interviews, we proceeded to interview the household’s second responsible person instead. In this study, we interpreted the target respondent’s answer as the whole household’s preference.

We asked for the respondents’ opinions on the important attributes of certain rice varieties by differentiating between “to produce” and “to consume.” The participants were able to supply up to three attributes, ranked in order of priority, for each question. Several options determined by pretest were preloaded on the tablet; however, the respondents were not shown or told of these options, so as to avoid response-order effect (Krosnick & Alwin, Citation1987). The respondents answered freely, and the interviewer selected the preset option closest to their answer. If there were no options close enough to the respondent’s answer, the interviewer selected “other” and specified the answer by manually entering the text. The translation of the survey answers from Malagasy to English was done carefully so as not to change the original meanings. A total of 596 households participated in the survey. The participants’ responses were summarized, as presented in the following section.

Preferences can be considered based on the characteristics demand theory developed by Lancaster, in which consumers derive utility and satisfaction from the goods’ attributes, rather than the goods themselves (Lancaster, Citation1966). Any product has a bundle of characteristics that contributes to consumers’ preferences for certain products over others. In the case of rice, favored traits can range widely, from taste and price, to texture, among others. The answers for rice-consumption preferences turned out to be more diverse than those for rice production. Hence, we decided to perform a cluster analysis of the consumers’ preferences. Cluster analysis is a technique that groups similar observations into clusters, based on several variables.

The respondents’ answers were first categorized into nine groups, sorted by attributes, to reduce dimensionality. Then, a hierarchical cluster analysis, using Ward’s method, was performed. After obtaining four clusters for comparison, we explored the differences in the household characteristics within each cluster by performing multiple comparisons. There were both categorical and continuous variables in the household characteristics. For categorical variables, we used Pearson’s chi-squared test to see if there was a significant difference between the clusters, and then we conducted a residual analysis to determine which cluster’s frequency differed significantly from its expected frequency. For continuous variables, we first performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the mean value’s difference in variance between clusters, and then conducted pairwise comparisons, adjusted for multiple comparisons based on the Tukey-Kramer method. These analyses were conducted using the statistical software STATA ver. 16.

3. Results

3.1. Important attributes of rice production

Table shows the households’ original responses and the number of households that identified the respective attributes as their primary importance, secondary importance, and tertiary importance. To interpret the relative importance considering the ranking, the weighted score was calculated as follows: (number of households that ranked the attribute first) 1.5 + (number that ranked it second)

1 + (number that ranked it third)

0.5. The table presents the attributes in descending order of the weighted score. Among the 596 participating households, 466 households provided three answers (78%), 59 provided two answers (10%), and 71 provided only one answer (12%).

Table 1. Important attributes of rice varieties to produce

High productivity is the most important and dominant attribute of rice varieties; 83% of the households selected it as one of the top three in their rankings. According to the weighted score, the second most important attribute is early maturity, followed by drought resistance.

Since several answers in Table appeared to weigh the same or similar aspects, the responses are categorized into seven aspect groups, as shown in Table . The number of households that answered at least one of the attributes in that group, regardless of the priority ranking, is also presented. For example, a household that answered “high productivity, drought resistance, and striga resistance” is counted as one household in a) yield and one in b) tolerance. The attributes are presented in descending order of the number of households in each group.

Table 2. Aspect groups and the number of households

The determined categorizations are not exclusive and could be subject to change according to the interpretation of the answers. The results imply that farmers would undoubtedly like to produce more. The category yield relates to the volume of harvest. It is true that tolerance affects the yield, but here the focus is on the characteristics that allow rice to last long, for example, resistance. Maturity is related to the cycle length. Regarding height, while short height was categorized into tolerance due to its higher lodging resistance, tall height was categorized into labor because it reduces the amount of labor needed for harvest.

Regarding the aspect group, yield is the most important aspect and was mentioned by 512 households (86% of the households). Respondents chose other aspect groups, but these equal less than half of the yield group. The majority of the responses conveyed production perspectives, while responses from 135 households (23%) offered consumption perspectives.

3.2. Important attributes of rice consumption

This section presents the households’ preferences in rice for consumption, which were determined in a manner similar to the production analysis described above. Table shows the households’ original answers and the number of households that selected each as their most important, second important, and third important attribute. The weighted score was calculated in the same way as described for Table . Among the 596 households, 459 households provided three answers (77%), 76 offered two answers (13%), and 61 gave one answer (10%).

Table 3. Important attributes of rice varieties to consume

For this part of the survey, there are no specific attributes that a significant majority of the households selected. However, according to the weighted scores, the most preferred attribute seems to be sweetness, one of the taste aspects. The second most preferred is swells easily, which contributes to a shorter cooking time. The third most preferred is grain purity, which indicates that the proportion of dirt or stones mixed with the rice is low or non-existent. The fourth most preferred attribute is white grain color; there are other answers related to grain color such as red (14th) or red and white (20th). The fifth preferred attribute is not sticky, which is more popular than sticky (15th). Nutritious (6th) also appeals to many people. Long grain (9th) is preferred over short grain (13th), and have on hand (16th) implies that the participants just consume what is available.

It was difficult to summarize the respondents’ choices using the original answers, which is why we decided to conduct a cluster analysis. We grouped these 20 responses into smaller groups to reduce the dimensionality before the analysis. The answers were sorted into nine groups, focusing on the aspects that the households pay particular attention to. Table lists the grouped attributes.

Table 4. Aspect groups and the number of households

We did not differentiate between the specifics of how the attributes were selected within the groups, that is, while some preferred red rice and some prefer white, they all paid notable attention to the appearance of rice. Table is presented like Table ; households that answered at least one of the attributes in the group, regardless of the priority ranking, were added to the count of that group. The attributes are presented in descending number order. The group that contained the largest number of households was appearance, followed by the flavor group, which included the attributes of sweetness and aroma.

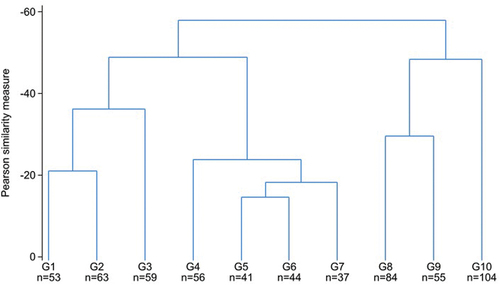

Based on these nine groups, we performed a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method, with the Pearson’s similarity coefficient. The top 10 branches of the dendrogram for this cluster analysis are shown in Figure . The height at which any two objects are joined together reflects their distance. As the clustering does not produce a unique partitioning point, we needed to choose the appropriate number of clusters by drawing a horizontal line below which we identified the reasonable clusters. From the dendrogram, two or four clusters appear to be a reasonable choice. The Calinski-Harabasz stopping rule or Duda-Hart index did not show distinct criteria for the number of clusters. Visualized plot from silhouette analysis suggested four to be a reasonable number of clusters. Based on this, these households were categorized into four clusters.

Figure 1. Top 10 branches of dendrogram for cluster analysis.

The four resulting clusters contain (I) 175, (II) 178, (III) 139, and (IV) 104 households, respectively. Figure illustrates the ratio of the households that selected the attributes within each group. For example, 86% of the households categorized in Cluster (I) chose grain purity and/or uncracked grain (grouped into the quality aspect group) as one of the top three important attributes. All households in Cluster (IV) chose sweetness and/or aroma (grouped into flavor). The households in the clusters most often chose quality (Cluster I), cooking (II), appearance and texture (III), and flavor (IV).

Figure 2. Ratio of the household selected attribute grouped by cluster.

Table presents the descriptive statistics by cluster. The number of households, and their percentage in the cluster in parenthesis, is shown in case of categorical variables, such as district. In addition, the figure presents the mean value in each cluster in the case of continuous variables, such as the respondent’s age. The total field size and total household assets are the values after logarithmic transformation.

Table 5. Statistics and results of multiple comparisons by clustera

A two-step multiple comparison was conducted, with the procedure depending on whether the variable was categorical or continuous. In the case of categorical variables, we first conducted Pearson’s chi-squared test to assess if the likelihood of an observed distribution of the variable differs from expected distribution. Pearson’s chi-squared test is not appropriate if the expected frequency is below five; however, there was no category in which the expected cell frequency was below five (the frequency of the “respondent’s relation to the head” being “other” in Cluster IV was only 2, but the expected frequency was 6.1). In the second step, a residual analysis was conducted to identify the clusters responsible for Pearson’s significant chi-square statistic. Residual analysis allows the determination of the significance level by analyzing the difference between the expected and observed frequencies.

For continuous variables, a two-step comparison was conducted as follows. First, a one-way ANOVA was performed to compare the mean values. As the ANOVA assumes parametric distribution, Bartlett’s test for equal variances was conducted and resulted in no continuous variable that rejected the hypothesis of equal variances. If the F-value generated by ANOVA suggests significance, it rejects the null hypothesis that the mean of the variable is the same across the groups. The second step involved carrying out multiple comparisons using the Tukey-Kramer method. As the observation number is different among clusters, the Tukey-Kramer method was selected for multiple comparisons as post hoc analyses to determine which of the means differed.

Table presents the results of these two-step multiple comparisons in addition to the descriptive statistics. The last column of Table shows the results of the first step, displaying either the p-values generated by Pearson’s chi-squared test or the F-values generated by the ANOVA. The value is presented in boldface if it is significant at the 5% level. Other boldfaced numbers in Table indicate the 5% significance level in the second step, marking the residual analysis or the multiple comparisons made by the Tukey-Kramer method.

From these results, we can identify a set of relatively common features shared by the households in each cluster. Note that the following features are just “relative” features, which only become apparent when compared with other clusters. The households in Cluster (I) tend to appreciate quality, that is, purity and/or uncracked attributes when they choose rice varieties. They are more likely to live in Betafo, have a larger field size, and grow other crops than rice. Meanwhile, the households in Cluster (II) generally favor cooking convenience, are more likely to live in Mandoto, have larger ratio of lowland rice field size, require significant time to fetch water, and purchase rice. The households in Cluster (III) value appearance (color and/or length) and texture (stickiness and softness); their more common features include their involvement in off-farm activities and frequent visits to the market. As for the households in Cluster (IV), they pay notable attention to flavor (sweetness/aroma), are more likely to inhabit Antsirabe II, and are less likely to cultivate upland.

4. Discussion

From the producer perspective, the importance of yield, which was identified as the most critical rice selection criterion in most African countries (Gridley et al., Citation2002), stands out in Madagascar. It is not surprising that rice farmers place importance on the amount they are able to produce. Meanwhile, answers related to heavy grain weight and few empty husks imply that there are some cases in which grain weights are lighter than expected; evidently, not only the number of grains but also their weight is considered an important characteristic.

Another important aspect is tolerance. Tolerance includes resistance to drought, insects, lodging, Striga, wind, and cold. Among these factors, drought resistance was identified as the most important stress, which is consistent with the findings of previous study (van Oort, Citation2018). Drought risk varies locally rather than by large-scale climatic variation (van Oort, Citation2018), so farmers might be aware of the variation of drought risk and care about the aspect. The need for various forms of grain tolerance is mostly a result of current pressing problems. The Vakinankaratra region is located in central Madagascar, where the frequency of cyclones is relatively low compared to that in other regions; however, its high altitude brings cold weather and frequent rice blast. Cold could lead to problems such as a prolonged growing season or sterility, but its importance was relatively low in this study because varieties adapted to the cooler climate in Madagascar may have been already acclimated to cold as mentioned by previous studies (Dingkuhn et al., Citation2017; van Oort, Citation2018). Local households’ selection of endurance (last long) as an important rice production attribute is a direct reflection of their experience of the disruption of rice cultivations before harvest.

Maturity, or cycle length, is also an important aspect from the producer’s perspective. Most households prefer early maturity; in fact, high productivity and early maturity are the most popular combination of answers. Farmers prefer short-duration rice for production as such varieties can be harvested before drought occurs (Efisue et al., Citation2008), which relates to the desire for drought resistance. Especially in upland areas where the growing season is short, varieties with early maturity such as NERICA may play important roles as suggested by previous study (Seck et al., Citation2012). Moreover, the same land can then be used to grow other crops (Efisue et al., Citation2008). In contrast, some answers favor late maturity or simultaneous maturity. We can also see some cases showing that farmers prefer late maturity in previous literature, especially at irrigated area (Efisue et al., Citation2008). Some may regard long duration as high yielding or may attempt to distribute labor and income economically across the production period, considering the other crops they are growing.

Labor-saving attributes are also worthy of consideration. Easy threshing could be problematic as it increases post-harvest losses through grain spillage, but this drawback is clearly outweighed by the labor-saving benefit, as Malagasy farmers usually thresh rice without using machines. As manual threshing is common in many developing countries (Kumar & Kalita, Citation2017), one of the aspects farmers often pay attention to is threshability (Gridley et al., Citation2002). In such cases, promoting mechanization could contribute to post-harvest loss reduction. This labor-saving category is also related to the preference for rice height, as most households preferred tall height over short. Tall varieties are easier to harvest by hand, especially for women who harvest the crop carrying children on their back (Efisue et al., Citation2008). Labor-saving allows farmers to allocate their time to other crops (Kumar & Kalita, Citation2017), thus, leading to the enhancement of agricultural production diversity and dietary diversity.

The characteristics related to consumption, such as good taste or easy swelling, are not as popular as yield or tolerance in terms of production. These attributes, attractive to consumers, are not popular choices among farmers in previous studies as well (Efisue et al., Citation2008; Gridley et al., Citation2002). Farmers prioritize profit over their own consumption preference when selecting the rice variety to produce, even though they are also the consumers of their products in most cases. The profit category includes less required input, high market price, and low seed price. Previously mentioned attributes in yield are certainly related to profit as well. From minority opinions, some believe high seed prices or new seeds to be indicators of the seed’s superiority. Have on hand indicates that availability comes before preference. Note that the varieties available might not necessarily reflect household preference, for example, rice is sometimes given as a gift. Preferences for these attributes are relatively low, and little has been mentioned in previous studies.

While the producers’ preferences are mainly related to the yield of the crop, there is no single dominant answer for the consumers’ preferences. Instead, they provided a variety of answers including taste, swelling capacity, texture, cleanliness, nutrition, and appearance (shape, color, and size). Clearly, even in rural Madagascar, rice is not a “one-size-fits-all” crop, as previous study claimed (Calingacion et al., Citation2014). As signified by the weighted scores, taste is widely preferred, especially sweetness. In previous studies, sweetness rarely stands out as an important attribute, although it might be implicitly included in the “tasty” aspect. In contrast to other African countries, where they tend to cook rice mixed with other ingredients—such as jollof rice in Ghana—Malagasy people are more likely to cook rice on its own and to eat it with accompanying dishes on the side. This tendency could explain their sensitivity to taste; in this case, they value the sweetness of the rice.

Previous studies identified cleanliness/purity and cooking properties as important criteria (WFP, Citation2019). Swelling capacity (swells easily), contributes to reducing cooking time and was consistently prioritized in this study’s results. Grain purity, rice with no stones or dirt, is also an important factor, which is one of the reasons why imported rice is preferred in African countries (Naseem et al., Citation2013). Locally grown rice sometimes contains stones due to the lack of an appropriate filtering process. Stones and/or dirt not only give the rice an unpleasant taste but are also a health risk, as the consumer could, for example, damage their teeth.

In terms of color, white rice seems to carry significant value. Color is one of the rice traits and whiteness is sometimes appreciated compared to yellowish parboiled rice in Ghana (Ayeduvor, Citation2018). In Madagascar, where parboiled rice is not popular, they compare with red rice. In terms of stickiness, non-sticky rice is preferred over sticky rice. Though consumers may prefer white over red rice or non-sticky over sticky rice, we need to note that this priority may be also influenced by the use of different rice varieties for different purposes in accordance with the recipe. Malagasy people tend to prepare rice in one out of two ways: vary maina (dry rice) or vary sosoa (rice porridge). Vary maina is made of white, non-sticky rice and is often eaten during the daytime. Meanwhile, vary sosoa is made from red sticky rice and is most often consumed in the morning (Andrianarison, Citation2006).

Other than what is listed above, there are several other aspects of consumption preference. These include aspects from the four grouped clusters that represent preferences for (I) quality, (II) cooking, (III) appearance and texture, and (IV) flavor. Evidently, Malagasy households have a wide variety of preferences for their rice consumption. Some are health-conscious enough to care about the nutrient content of the rice. Some pay attention to the uncracked shape—although cracking does not cause any proven hazards in terms of eating. While many African people prefer imported rice with aroma (Ayeduvor, Citation2018; Naseem et al., Citation2013; Tomlins et al., Citation2005), Malagasy people seem to prefer locally sourced, non-scented rice. In this sense, Malagasy people’s consumer preferences differ slightly those of from other African countries.

From these results, we were able to identify producers’ dominant preference for attributes that contribute to productivity, while as consumers they favor various aspects such as appearance, flavor, quality, cooking, and texture. Although farmers pay little attention to consumers’ perspectives while selecting rice varieties to produce, understanding consumers’ preferences is beneficial for them as it could lead to sales and profits. We found several unique characteristics of the Malagasy consumers, which may defy the current body of knowledge regarding the preferences of African nations. As rice preferences vary significantly by country and region, understanding local preferences for rice contributes to the development of rice breeding and marketing strategies.

5. Conclusion

We explored rural Malagasy farmers’ preferred rice characteristics from both producer and consumer perspectives by analyzing our interview survey data. This contributes to the literature on the topic since most previous studies considered producer and consumer perspectives separately. Furthermore, even though rice is a dominant staple in Madagascar, there has been limited research on Malagasy rice-trait preferences. We found that farmers as producers showed a strong preference for high productivity, while as consumers they showed diverse preferences that could differ from consumer preferences in other African rice-consuming countries. Our current study is limited in that it only uses a quantitative approach to gaining a detailed perspective of participants’ preferences. Hence, future qualitative research on “why” Malagasy people prefer certain attributes would be valuable.

Most farmers and most previous breeding efforts on rice in Madagascar have mainly focused on increasing productivity, which serves producers’ direct needs, and have not paid enough attention to consumer preferences. Considering the current food insecurity situation in Madagascar, increase in productivity obviously has a priority. Yet, understanding consumer preference is also important because producers are affected by consumer preference transmitted through market. For example, traits related cooking such as swelling capacity is rarely considered by producers, but some consumers appreciate it. Rice preference varies among countries, and this study’s comprehensive findings on Malagasy rice preferences could contribute to developing targeted rice-breeding and marketing strategies in Madagascar.

20230612 optional information.docx

Download MS Word (437 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all interviewees for their time and all those who supported the implementation of the survey. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2281092

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sakiko Shiratori

Sakiko Shiratori is a senior researcher at the Information and Public Relations Office of the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences (JIRCAS), Japan. She has an interest in the linkages between agriculture, food consumption, and human nutrition.

Jules Rafalimanantsoa

Jules Rafalimanantsoa is the Head of the Technical Coordination Unit of the National Office of Nutrition (ONN), Madagascar. He specializes in nutrition, food systems, and process engineering.

Harisoa Sahondra Andriamanana Razafimbelonaina

Harisoa Sahondra Andriamanana Razafimbelonaina is a researcher in the Research and Development Department of the National Center for Applied Research for Rural Development (FOFIFA), Madagascar. Her areas of interest included rural geography, agriculture, rural development, socioeconomics, and gender. Starting with the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) project which primarily aimed to increase rice yields under low-fertility conditions in Madagascar, we have been conducting several collaborative research projects related to agriculture and nutrition in rural Madagascar.

References

- Abel-Ratovo, H. L., & Razafimbelonaina, H. S. A. (2019). Etude de Marché de semences de Riz, incluant la commercialisation des produits (Paddy/Riz blanc) [rice seed market study, including the marketing of products (Paddy/white rice)]. Report for AFRice Projet. French.

- Andrianarison, F. C. H. (2006). Analyse qualitative des critères de choix des consommateurs de riz dans la Commune Urbaine d’Antananarivo, Madagascar [Qualitative analysis of the choice criteria of rice consumers in the Urban Commune of Antananarivo, Madagascar]. Mémoire de fin d’études. Université d’Antananarivo, French.

- Arouna, A., Lokossou, J. C., Wopereis, M. C. S., Bruce-Oliver, S., & Roy-Macauley, H. (2017). Contribution of improved rice varieties to poverty reduction and food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Food Security, 14, 54–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2017.03.001

- Ayeduvor, S. (2018). Assessing quality attributes that drive preference and consumption of local rice in Ghana. GSSP Working Paper, 48. IFPRI. https://doi.org/10.2499/1041943683.

- Calingacion, M., Laborte, A., Nelson, A., Resurreccion, A., Concepcion, J. C., Daygon, V. D., Mumm, R., Reinke, R., Dipti, S., Bassinello, P. Z., Manful, J., Sophany, S., Lara, K. C., Bao, J., Xie, L., Loaiza, K., El-Hissewy, A., Gayin, J., Sharma, N. … Fitzgerald, M. (2014). Diversity of global rice markets and the science required for consumer-targeted rice breeding. PloS One, 9(1), e85106. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085106

- Dabat, M.-H., Pons, B., & Razafimandimby, S. (2008). Des consommateurs malgaches sensibles à la qualité du riz [Malagasy consumers sensitive to rice quality]. Économie Rurale: Agricultures, Alimentations, Territoires, 308(308), 6–18. French https://doi.org/10.4000/economierurale.330

- Dingkuhn, M., Pasco, R., Pasuquin, J. M., Damo, J., Soulié, J. C., Raboin, L. M., Dusserre, J., Sow, A., Manneh, B., Shrestha, S., & Kretzschmar, T. (2017, September). Crop-model assisted phenomics and genome-wide association study for climate adaptation of indica rice. 2. Thermal stress and spikelet sterility. Journal of Experimental Botany, 68(15), 4389–4406. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erx250

- Efisue, A., Tongoona, P., Derera, J., Langyintuo, A., Laing, M., & Ubi, B. (2008). Farmers’ perceptions on rice varieties in Sikasso region of Mali and their implications for rice breeding. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science, 94, 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037X.2008.00324.x

- The Famine Early Warning Systems Network. (2018). Madagascar enhanced market analysis. USAID.

- Fiamohe, R., Nakelse, T., Diagne, A., & Seck, P. A. (2015). Assessing the effect of consumer purchasing criteria for types of rice in Togo: A choice modeling approach. Agribusiness, 31(3), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21406

- Food and Agricultural Organization. (2017). Regional overview of Food Security and Nutrition in Africa 2016. The challenges of building resilience to shocks and stresses. FAO.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. (2023). Food and Agriculture Data [FAOSTAT]. Retrieved February 6, 2023, from http://www.fao.org/faostat/.

- Global Rice Science Partnership. (2013). Rice almanac (4th ed.). International Rice Research Institute.

- Gridley, H. E., Jones, M. P., & Wopereis-Pura, M. (2002). Development of new rice for Africa (NERICA) and participatory varietal selection. Breeding rainfed rice for drought-prone environments: Integrating conventional and participatory plant breeding in south and Southeast Asia. In Proceedings of a DFID Plant Sciences Research Programme/IRRI Conference Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines. 2002 March.

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. [HLPE]. (2017). Nutrition and Food Systems. The High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security.

- Hossain, I., Rahman, N. F., Kabir, S., & Siddique, A. B. (2015). Development and validation of producer and consumer preference models for rice varieties in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Rice Journal, 19(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.3329/brj.v19i1.25223

- Jin, S., Mansaray, B., Jin, X., & Li, H. (2020). Farmers’ preferences for attributes of rice varieties in Sierra Leone. Food Security, 12(5), 1185–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01019-w

- Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1987). An evaluation of a cognitive theory of response-order effects in survey measurement. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 51(2), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1086/269029

- Kumar, D., & Kalita, P. (2017). Reducing postharvest losses during storage of grain crops to strengthen food security in developing countries. Foods, 6(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6010008

- Laborte, A. G., Paguirigan, N. C., Moya, P. F., Nelson, A., Sparks, A. H., Gregorio, G. B., & Wang, Z. (2015). Farmers’ preference for rice traits: Insights from farm surveys in Central Luzon, Philippines, 1966-2012. PLoS One, 10(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136562

- Lancaster, K. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74(2), 132–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/259131

- Local Burden of Disease Child Growth Failure Collaborators. (2020). Mapping child growth failure across low- and middle-income countries. Nature, 577(7789), 231–234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1878-8

- Misiko, M. (2013). Dilemma in participatory selection of varieties. Agricultural Systems, 119, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2013.04.004

- Naseem, A., Mhlanga, S., Diagne, A., Adegbola, P. Y., & Midingoyi, G.-K. (2013). Economic analysis of consumer choices based on rice attributes in the food markets of West Africa—the case of Benin. Food Security, 5(4), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0276-6

- Raboin, L. M., Randriambololona, T., Radanielina, T., Ramanantsoanirina, A., Ahmadi, N., & Dusserre, J. (2014). Upland rice varieties for smallholder farming in the cold conditions in Madagascar’s tropical highlands. Field Crops Research, 169, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2014.09.006

- Rakotosamimanana, R. V., Valentin, D., & Arvisenet, G. (2015). How to use local resources to fight malnutrition in Madagascar? A study combining a survey and a consumer test. Appetite, 95, 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.011

- Sakurai, T., Ralandison, T., Takahashi, K., Arimoto, Y., & Kono, H. (2015). Is there any premium for unobservable quality? A hedonic price analysis of the Malagasy rice market. IDE Discussion Paper, 504.

- Seck, P. A., Diagne, A., Mohanty, S., & Wopereis, M. C. S. (2012). Crops that feed the world 7: Rice. Food Security, 4(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-012-0168-1

- Shiratori, S., & Nishide, A. (2018). Micronutrient supply based on the Food balance sheet and the prevalence of inadequate intakes in Madagascar. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 77, E70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118000745

- Shiratori, S., Nishide, A., & Doi, K. (2018). Nutrition-sensitive agricultural development strategy in Madagascar. Water, Land and Environment Engineering, 86(10), 10881–884. https://doi.org/10.11408/jjsidre.86.10_881

- Suvi, W. T., Shimelis, H., & Laing, M. (2021). Farmers’ perceptions, production constraints and variety preferences of rice in Tanzania. Journal of Crop Improvement, 35(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427528.2020.1795771

- Tomlins, K. I., Manful, J. T., Larwer, P., & Hammond, L. (2005). Urban consumer preferences and sensory evaluation of locally produced and imported rice in West Africa. Food Quality and Preferences, 16(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.02.002

- Tyack, N., Manneh, B., Konate, A., Kessy, T., Traore, S. A., & Sie, M. (2020). Twenty years of participatory varietal selection at AfricaRice. In O. T. Westengen & T. Winge (Eds.), Farmers and plant breeding: Current approaches and perspectives (pp. 65–79). Routledge.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2023). PSD Online. Retrieved February 6, 2023: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/.

- van Oort, P. A. J. (2018). Mapping abiotic stresses for rice in Africa: Drought, cold, iron toxicity, salinity and sodicity. Field Crops Research, 219, 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2018.01.016

- Wood, K., Carragher, J., & Davis, R. (2017). Australian consumers’ insights into potatoes—Nutritional knowledge, perceptions and beliefs. Appetite, 114, 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.038

- World Bank. (2022a). Poverty & Equity Brief, Madagascar. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from October 2022. https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/current/Global_POVEQ_MDG.pdf

- World Bank. (2022b). The World Bank in Madagascar. Retrieved February 6, 2023, from Last updated: Oct 7, 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/madagascar/overview

- World Food Programme. (2019). La filière riz à Madagascar face à la fortification [The rice sector in Madagascar faced with fortification]. Programme Alimentaire Modial. French.

- World Food Programme and UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund. (2011). Rural Madagascar comprehensive food and nutrition security and vulnerability analysis. UNICEF and WFP country offices.

- Yadav, S., & Kumar, V. (2018). Feeding the world while caring for the planet. Strengthening partnerships for sustainable rice production. DSRC Newsletter, IRRI. December 2018, 1(2). Retrieved February 6, 2023, from https://drive.google.com/file/d/15WHxvk9C5xoNlgz-O_n_-Pym69_j3pnq/view.