?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Sheep production in Ethiopia is an important activity for smallholder farmers, but the sector has been challenged by many factors among which feed shortage is the major one. To solve this challenge, farmers traditionally supplement sheep with coffee leaf. This study was conducted at Areka Agricultural Research Center, Wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia, with the objectives of evaluating carcass yield, composition and economic profitability of supplementing powdered coffee leaves to indigenous Wolaita highland sheep fed hay-based diets. This experiment followed the layout of Completely Randomized Design (CRD) on twenty male intact sheep with mean initial body weight 17.4 ± 0.1 kg and five treatments. Treatments were T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5 with powdered coffee leave meal inclusion (CLPMI) proportion of 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20%, respectively with four replications per treatment. Concentrate mix (CM) of 300 gm on dry matter base/head/day was provided for the lambs. The trial was conducted for 90 days followed by digestibility trial of 7 days. Significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed among treatments on slaughter body weight, empty body weight, hot carcass weight and dressing percentage. On partial budget analysis, 20% of coffee leaves powder meal inclusion resulted in optimum DM intakes, weight gain and carcass yield. Higher net income (959.5ETB (17.26USD)/sheep) was obtained from the sheep supplemented with 20% inclusions (T5) of coffee leaves powder meal followed by T4 (15% powder coffee leaves meal inclusion), T3 (10%), T2 (5%) and T1 (0%). Thus, this study highlighted a positive potential of coffee leaves powder meal as a supplement to poor quality roughages.

1. Introduction

Sheep rearing is one of the main cash income sources for the farmers in Ethiopia. Feed shortage in terms of quality and quantity is one of the major bottlenecks facing small holder sheep producers in Ethiopia in general and in the current study site specifically (Mohammed, Citation2020). Farmers use different strategies traditionally to supplement sheep during feed scarcity and complement their productivity throughout the year. In the current study site it is common to use coffee leave in the form of liquid or powder to supplement the growing lambs and fattening rams to improve productivity. No research has been done prior to this on effect of supplementing coffee leave powder meal on carcass characteristics and economic feasibility on Wolaita highland sheep in the current study area. Thus, this study is aimed at evaluating dietary effects of coffee leaves powder meal supplementation on carcass characteristics and economic feasibility of intact male yearling indigenous Wolaita highland sheep fed hay as basal diet.

Sheep production of Ethiopia is characterized by low output in terms of growth rate, meat production and reproductive performance (Adugna et al., Citation2000). The causes for low productivity of sheep are multidimensional that include poor genetic potential, poor veterinary services, inadequate quantity and quality of feed, and poor breeding strategy (Betsha, Citation2005). Among these limiting factors, poor feed supply and feeding system is the most important as the feed resources in different parts of Ethiopia are generally natural pasture and residues of different crops (Adugna et al., Citation2012). The stability of natural pasture as a source of feed is, however, limited to the wet season (Zinash et al., Citation1995). Most of it is depleted and degraded because of overgrazing (Alemayehu, Citation2016).

Ethiopia is the center of origin for highland coffee (Coffee Arabica L), which is one of the most cherished cash crops in the country (ECFF Environment and Coffee Forest Forum, Citation2015). Coffee is intercropped with other buddy crops or multipurpose fodder trees in complex agro forestry systems as low-cost production options to spread food and cash security (Taye, Citation2014). Almost every type of plant that is produced or processed for human food or animal feed yields one or more by-products that can be utilized as feed for animals (Ensminger, Citation2002). Thus, coffee production for human consumption gives rise to a number of byproducts that may be used as ruminant feeds. These include leaves, pulp from the bean, coffee residues, coffee meal and spent coffee grounds (Bouafou et al., Citation2011). Coffee leaves are relished by sheep and have a high nutritive value with high amount of primary nutrients (Nitrogen (47%), Phosphorus (61%), and Potassium (36%) and secondary essential minerals (Calcium (50%), Magnesium (47%), and Sulfur (33%) (Michiel et al., Citation2004). In the current study area, coffee leaf drink locally called (tukkiya-tochiya) and a drink made from the infusion of coffee leaves locally called (haytta-tukkiya) are common feed supplements for livestock especially small ruminants and lactating cows for many years. People traditionally believe that, supplementing coffee leave meal as feed additive to animals improves feed intake, growth rate, milk yield and milk quality and carcass characteristics. However no scientific research has been conducted on its effect on carcass characteristics and economic analysis of its supplementation and has never been supported by any scientific literatures.

In this context, this work aims to evaluate dietary effects of coffee leaves powder meal supplementation on carcass characteristics of intact male yearling indigenous Wolaita highland sheep fed hay as basal diet, as well as to analyze economic feasibility of supplementing coffee leaves powder meal in intact male yearling indigenous Wolaita highland sheep.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design and treatments

The experiment was conducted at Areka Agricultural Research Center, Mante Dubo sub-research site, Ethiopia. The site is located at a distance of about 309 km south of the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa and at an altitude of 1711 masl and situated at N 07’ 06.4312` and E037’ 41.688`. The mean annual temperature of the area was between 22°C and 24°C. The rain falls between 1201 and 1600 mm with highest from July to September.

In the experiment, which lasted for 90 days, 20 male sheep with an average initial body weight of 17.39 ± 0.094 kg were used. The experimental design was a completely randomized design with five treatment diets that corresponded to five levels of coffee leaves powder meal supplementation in the proportion of 0.0, 5.0, 10.0, 15.0 and 20.0% in the daily requirement of concentrate mix with four replications per treatment (Table ). Four sheep were randomly assigned to each of the five treatments. They were allowed to an adaptation period of 2 weeks to the environment and experimental diets. At the end of the adaptation period the sheep were fasted overnight and initial body weight was measured.

Table 1. Treatment layouts of the experiment

2.2. Experimental diet preparation and feeding

Natural pasture was harvested manually from Areka Agricultural Research Center, Mante Dubo sub-research site at November 2021, kept under hay shade to maintain its quality and used as a basal diet thought out the experimental period. During feeding, hay was chopped () to a length of approximately 5–10 cm for ease of feeding. Appropriate matured and green coffee leaves (test feed), were collected by hand stripping and were subjected to air drying under shade for 3–5 days by spreading on plastic sheets. Air dried coffee leaves were chopped by using local mortar to powder form to pass through sieve to get a uniform texture. Processed coffee leaves powder meal was kept in clean sacs thought out the experimental period.

Taro (Boloso-I), a common root crop supplemented commonly to animals in the area as concentrate source was purchased from the neighboring farmers of the study area and it was washed, trimmed, chopped and sun dried for 3–4 consecutive days by thinly spreading on plastic sheets to reduce moisture content and make easy to grind. The chopped and sun dried taro was milled by using milling machine. Wheat bran was purchased from Areka Town administration, TAM flour mill factory. Nuge seed cake and mineral mixture were purchased from Bahir Dar city, Amhara Region State. Finally, the concentrate supplement feed was prepared from Taro Boloso-I, Wheat bran, Nuge seed cake and mineral mixture, which were mixed in the ratio of 45, 29.97, 15.03 and 10%, respectively by using mixing machine. Processed concentrate mix was kept in clean sacs thought out the experimental period. The CP was set based on the recommendation made by Ensminger (Citation2002), who suggested that for moderate growing lambs that weigh 10 to 20 kg body weight, the CP required for supplement would range from 16.3 to 26.4%. The amount of concentrate mixture in this experiment was determined to be 300 g on DM basis based on the recommendations of Zemichael and Solomon (Citation2009) for Arado sheep (Table ). Pure drinking water and natural grass hay were supplied ad libitum for sheep. The concentrate feed was provided twice a day at morning and afternoon in the ratio of 50:50.

Table 2. Composition of concentrate feed in the rations

2.3. Experimental animals and their management

The age of sheep was estimated based on dentition and information obtained from the owners. Before starting the experiment, the sheep were ear tagged and de-wormed against internal parasites (Figure ) with Albendazole 300 mg and Acaridae for external parasite.Thereafter, they were housed individually in pens prepared for sheep experiment in the Areka research center. Body weights of the sheep were recorded at the beginning of the experiment and after 2 weeks by using a hanging scale of 100 kg capacity.

2.4. Data collection

2.4.1. Evaluation of carcass and non-carcass parameters

At the end of the digestibility trial, all of the experimental animals were fasted overnight; two sheep from each treatment group were selected on weight base, taken to a slaughtering slab. On slaughtering, the sheep were killed by severing the jugular vein and the carotid artery with a knife. The blood was drained into bucket and its weight was recorded. The skin was carefully flayed to prevent fat and tissue attachments. The skin was weighed with ears and immediately after the removal of legs below the fetlock joints. The gastrointestinal tract with the exception of the esophagus was removed with its contents and weighed. The gastrointestinal organs were reweighed after emptying its contents. Fat in gastro-intestinal tract and kidney fat were removed and individually weighed. Internal organs, namely, lung, trachea, esophagus, heart, liver, kidney and pancreas, were removed and weighed.

The hot carcass weight (HCW) was estimated after removing weight of the head, thorax, abdominal and pelvic cavity contents as well as legs below the hock and knee joints and was measured after about one hour from slaughter. Next, the rib eye muscle area was obtained by exposing the longisimuss dorssi muscle after a transverse section on the carcass between the 12th and 13th ribs, and the rib eye muscle area was traced first on a transparent paper then by counting the number of squares lying on the traced picture in the square paper and multiplied by the area of Single Square (Müller, Citation1980). The empty body weight was calculated as gut content deducted from slaughter weight. Percentage of total edible offal components (EOC) were taken as the sum of, heart, liver, empty gut, kidney, tail fat and tongue. Percentage of total non- edible offal (NEOC) component were taken as the sum of blood, head except tongue, skin with ears, esophagus,lung, abdominal fat, kidney fat penis, testis, testicle fat, trachea, spleen, gallbladder without bile, pancreas, feet and gut content. Classification of offal’s into NEOC and EOC were based on eating habit of the people residing in and around the study area. Dressing percentage was calculated as weight of carcass divided by either slaughter weight or empty body weight multiplied by 100 according to the procedures of Bonvillani et al. (Citation2010). The dressing percentage is therefore based on:

2.4.2. Partial budget analysis

The partial budget analysis was taken to determine cost benefit (profitability) analysis of supplementing different proportions of coffee leaf powder meal inclusion on sheep feed. The variable costs were calculated from test feed (coffee leaf powder meal), concentrate mix feed, basal feed, sheep and medication costs which are supplied for each experimental treatment costs. The partial budget analysis was calculated from the variable costs and benefits. At the end of the experiment, the selling price of each experimental sheep was estimated by three experienced sheep dealers from Areka Town market and the average of those three-estimation prices was taken. The total returns (TR) were determined by calculating the difference between the estimated selling prices and purchasing price of experimental male intact indigenous Wolaita Highland sheep. Net return (NR) was calculated as:

The change in net return (ΔNR) was calculated as the difference between change in total return (ΔTR) and the change in total variable costs (ΔTVC).

2.5. Statistical analysis

All data collected were analyzed by ANOVA using the general linear model procedures of statistical analysis system (SAS, Citation2002). Means were compared with the Tukey test and considered statistically significant at a P < 0.05.

Where:

Yij = Overall response variable;

μ = Overall mean;

Ti = Treatment effect (ith effect of coffee leave powder meal supplementation);

Eij = Random error.

3. Results

3.1. Carcass and non-carcass characteristics of experimental animals

3.1.1. Carcass characteristics of male intact indigenous Wolaita highland sheep

The result showed that significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed among treatments on slaughter body weight, empty body weight, hot carcass weight and dressing percentage (Table ). Slaughter body weight, empty body weight, hot carcass weight and rib eye area were statistically higher (P < 0.001) in sheep received T5 than the remaining treatments. Whereas, the dressing percentage values (both in slaughter and empty body weight base) were statistically higher in T2 compared to others.

Table 3. Carcass components of male intact indigenous Wolaita highland sheep supplemented different level of coffee leaves powder meal

3.1.2. Non-carcass components characteristics

The heart, liver and kidney contents in this study ranged from 313.6 (T1) to 492 g (T5), 72 (T1) to 179.6 g (T5), 65.3 (T1) to 108.6 g (T5), respectively. Tongue weight of sheep in T4 and T5 was statistically higher (P < 0.001), than sheep in T1 and T2 (Table ). Besides, the gut empty and tail fat contents in the current result ranged from 451.7 g (T3) to 671 (T2) and from 203 g (T1) to 501 g (T5), respectively. The highest (P < 0.05) kidney weight was observed for the sheep in the T5. In the present study, tail fat appeared to be lower for (T1) compared to others.

Table 4. Edible non-carcass components of male intact indigenous Wolaita highland sheep supplemented with coffee leaves powder meal

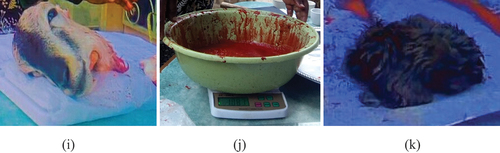

There were significant differences (P < 0.05) among treatments in weight parameters of non-edible offal components (Table ). The head (i), blood (j), testis, gall bladder (without bile, feet spleen and lung, gut contents, kidney fat and abdominal fat were ranged from 1.03 (T2) to 1.2T2) to 994 g (T4), 176 (T1) to 233 g (T5), 19(T2) to 24 g (T5), 413 (T1) to 550 g (T5),40 (T1) to79.6 g (T5) and 134(T2) to 246 g(T5), 12 (T1) to 57.3 g (T4) and 17 (T1) to 65 g (T5), respectively. The gut content of the study was statistically lower (p < 0.05) for sheep in T5, but not statistically different (P > 0.05) among other treatments. Except for blood and gut contents, most of the non-edible offal in the current study were statistically higher (P < 0.05) for coffee leaves powder meal supplemented sheep than the control.

Table 5. Non-edible non-carcass components of male intact Wolaita highland sheep supplemented with coffee leaves powder meal

3.2. Partial budget analysis

The result indicated that higher net income (959.5ETB (17.36USD)/sheep) was obtained from the sheep in (T5) followed by T4, T3, T2 and T1 (Table ). It was also observed that, there was no loss of money in all treatments as a result of supplementation. However, coffee leaves powder meal supplemented sheep showed positive net profit and income than control.

Table 6. Partial budget analysis of male intact indigenous Wolaita highland sheep supplemented with coffee leaves meal powder meal

4. Discussion

Supplementation of powdered coffee leaves meal to male intact indigenous Wolaita highland sheep that fed high as a basal diet has resulted in higher Slaughter body weight, empty body weight, hot carcass weight and rib eye area than control ones. The reason for this could be associated to the differences in the final live body weights as a report of Cloete et al. (Citation2004) found that larger final live body weight results in a higher carcass yield. Even though there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) between the treatments in terms of dressing percentage in empty body weight basis, higher dressing percentage was recorded in T2 relatively than others which could be an indication of the effect of gut fill on dressing percentages. Gut fill constitutes a significant amount of the body weight even when the animals are fasted long hours (Gibb & Ivings, Citation1993). On the other hand, this is good implication for prediction of carcass weight on empty weight basis that seems to be appropriate as the influence of gut fill would be removed. The rib eye area ranged between 8.7 cm2 (T1) and 11.6 cm2 (T1) in current study was higher than the ranges reported by Mulu (Citation2005) (5.20 to 8.80 cm2) for Wogera sheep, and Asnakew (Citation2005) (5.20–8.80 cm2) for Hararghe highland goats. However, the mean rib eye area measured in this study was lower than (29.7 cm2) reported by Gebregziabher et al. (Citation2003) for Horro lambs supplemented with different concentrate mixtures. The lower rib eye area scored in control animals for the current study indicated that, sheep supplemented with different level of powdered coffee leave meal were able to develop a better muscle than control.

Except for blood and gut contents, most of the non-edible offal in the current study were statistically higher (P < 0.05) for supplemented sheep than the control. In line with this result, Tafa et al. (Citation2010) reported higher non-edible offal for supplemented Arsi- Bale sheep than the control group sheep fed basal diet of grass hay. In the contrary, Gebeyew et al. (Citation2015) reported that there was no significant difference for non-edible offal among treatment diets for Hararghe Highland sheep. Differences in fat deposit is highly directly related with plane of nutrition or energy content of the diet and appropriate dietary energy-protein combinations (Archimede et al., Citation2008). On the other hand, the increase in liver weight with supplementation might be related to the storage of reserve substances such as glycogen as described by Lawrence and Fowler (Citation1998). Relatively higher skin weight obtained in T5 might be associated to higher metabolizable energy intakes which has resulted in better subcutaneous layer fat deposition. According to the result of Assefu (Citation2012), skin could be affected by diet, where high level of concentrate feeding resulted in heavier skin weight. The gut content in current study was lower (p < 0.05) for T5, but nearly the same other treatments. The higher gut content for T1 might be due to more feed retention time in the rumen and also reflected in poor digestibility which agrees with the finding of Van Soest (Citation1994).

The higher net income was obtained in supplemented animals than control. Higher net income was recorded in T5 followed by T4, however, there was no net income and loss for T1. This indicates that there was no loss of ETB/sheep in all treatments and supplementation of coffee leaves powder meal has persuaded positive net profit and income. Similarly, Shiferaw et al. (Citation2022) has reported that non-conventional feed supplementation is potentially more practicable and economically cheap for smallholder farmers engaged in sheep fattening in Ethiopia.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, 20% supplementation of powdered coffee leaves meal to indigenous Wolaita highland sheep seem to be positive in terms of carcass characteristics improvement and economic efficiency. Accordingly it is more applicable and affordable for farmers in the study site. However, further study is needed by increasing level of supplementation so that higher net income and improved carcass characteristics could be obtained as it is limited in 20% of concentrate feed in current study but showed no negative impact and higher potential.

Author’s contribution

The research reported on this manuscript is related to a wider project that is focusing on analyzing feeding value and nutritional quality of powder coffee leaves meal on growth, production performance, carcass characteristics and economic efficiency of indigenous Wolaita highland sheep that fed hay as basal diet. The remaining parts will also be prepared and submitted as soon as possible for publication.

• Author 1: Participated in designing the study, data collection, analysis and manuscript writing

• Author 2: Participated in designing the study, experimental works, measuring carcass characteristics and data analysis

• Author 3: Participated in data collection, experimental works, laboratory analysis and manuscript writing

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no competing interests between them and with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Wolaita zone administration for financial support and Areka research center for permission of experimental site/house for the experiment. They also would like to extend their thanks to Hawassa University and their laboratory technicians for facilitating lab works.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tibebu Kochare

Tibebu Kochare, Wolaita sodo University, college of Agriculture, Email: [email protected]

References

- Adugna, T., Alemu, Y., Alemayehu, M., Dawit, A., Diriba, G., Getnet, A., Lemma, G., Seyoum, B., & Yirdaw, W. (2012). Livestock feed Resources in Ethiopia: Challenges, opportunities and the need for transformation. National feed committee report, Ethiopian animal feed industry association (EAFIA) and the ministry of agriculture and rural development (MoARD). Image enterprise PLC, Addis Ababa, 50p.

- Adugna, T., Tilahun, S., Tegene, N., Merkel, R. C., & Goetsch, A. L. (2000). Nutritional constraints and future prospects for goat production in East Africa. Langston University Extension Service.20p.

- Alemayehu, M. (2016, August 10). Country pasture/Forage resource profiles: Ethiopia. Retrieved. http://www.Fao.org/AGp/agpc/doc/counprofEthiopia.Htm.

- Archimede, H., Pellonde, P., Despois, P., Etienne, T., & Alexandre, G. (2008). Growth performance and carcass traits of Ovin Martinik lambs fed various ratios of tropical forage to concentrate under intensive conditions. Small Ruminant Research, 75(2–3), 162–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2007.10.001

- Asnakew, A. (2005). Feedlot fattening performance and carcass characteristics of intact male Hararghe highland goats fed different levels of hay to concentrate ratios. M.Sc. Thesis, Alemaya University,

- Assefu, G. (2012). Comparative feedlot performance of Washera and Horro sheep fed different roughage to concentrate ratio. MSc Thesis, Haramaya University,

- Betsha, S. (2005). Supplementation of graded levels of peanut cake and wheat bran mixtures on nutrient utilization and carcass parameters of Somali goats. MSc. thesis presented to the school of graduate studies of Alemaya University of Agriculture, pp. 75

- Bonvillani, A., Peña, F., de Gea, G., Gómez, G., Petryna, A., & Perea, J. (2010). Carcass characteristics of criollo cordobés kid goats under an extensive management system: Effects of gender and live weight at slaughter. Meat Science, 86(3), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.05.018

- Bouafou, K., Guy, M., André, K. B., Zannou-Tchoko, V., & Kati-Coulibally, S. (2011). Potential Food Waste and by-products of coffee in Animal feed. Electronic Journal of Biology, 7(4), 74–80.

- Cloete, J. J. E., Hoffman, L. C., Cloete, S. W. P., & Fourie, J. E. (2004). A comparison between the body composition, carcass characteristics and retail cuts of South African mutton merino and dormer sheep. South African Journal of Animal Science, 34(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajas.v34i1.4040

- ECFF (Environment and Coffee Forest Forum). (2015). Coffee: Ethiopia’s gift to the World; the traditional production systems as living examples of crop domestication, and sustainable production and an assessment of different certification schemes. Addis Ababa.

- Ensminger, M. (2002). Sheep and goat Science (Animal Agriculture series). Interstate Publishers, Inc. Daville.

- Gebeyew, K., Animut, G., Urge, M., & Feyera, T. (2015). The effect of feeding dried tomato pomace and concentrate feed on body weight change, carcass parameter and economic feasibility on Hararghe highland sheep, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology, 6(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7579.1000217

- Gebregziabher, G., Dirba, G., Lemma, G., Yohannes, G., & Gemeda, D. (2003). Effect of noug cake and sesbania sesban supplement on growth performance and carcass characteristics of Horro lambs. Proceedings of 10th annual conference of Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP) held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, August 21-23, 2003.

- Gibb, M., & Ivings, E. (1993). A note on the estimation of body fat, protein and energy content of lactating HF cows by measurement of condition score and live weight. Journal of Animal Production, 56(2), 281–283. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003356100021383

- Lawrence, T. C. J., & Fowler, V. R. (1998). Growth of farm animals. CABI publishing.

- Michiel, K., Jansen, D. M., & Nguyen Van, T. (2004). Coffee Arabica handbook.

- Mohammed, N. (2020). Sheep fattening, Marketing systems and constraints of Ethiopia: A review. World Applied Sciences Journal, 38, 416–421. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wasj.2020.416.421

- Müller, L. (1980). Carcass characteristics and meat quality of intact or castrated bovines, supplemented or not during the first winter. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782006000600031

- Mulu, M. (2005). Effect of feeding different levels of brewery dried grain on live weight gain and carcass characteristic of Wogera sheep fed on basal diet. MSc Thesis Presented to School of Graduate Study of Alemaya University, 54p.

- SAS. (2002). SAS (r) proprietary software version 9.00 (TS MO). SAS Institute Inc.

- Shiferaw, F., Asmare, B., Melekot, M. H., & Pellikaan, W. F. (2022). Dried-Atella as an affordable supplementary feed resource for a better sheep production: In the case of washera lambs in Ethiopia. Translational Animal Science, 6, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txac146

- Tafa, A., Melaku, S., & Kurtu, J. P. (2010). Supplementation with linseed (linum usitatissimum) cake and/or wheat bran on feed utilization and carcass characteristics of arsi-bale sheep. Tropical Animal Health Production, 42(4), 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-009-9475-8

- Taye K. (2014). Sustainability of coffee environments and genetic resources in Ethiopia (pp. 11–27). In: A. Girma & T. Wube (Eds.). Proceedings of 24th annual conference of the biological society of ethiopia4, coffee production, variety and trading -ways to maximize Ethiopia’s benefits, Dilla,

- Van Soest, P. J. (1994). Nutritional ecology of ruminants (2nd ed.). Cornell University press.

- Zemichael, G., & Solomon, M. (2009). Intake, digestibility, body weight and carcass characteristics of Tigray sheep fed Tef Straw supplemented with sesame seed meal or Wheat bran and their mixtures. East African Journal of Sciences Volume, 3(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.4314/eajsci.v3i1.42784

- Zinash, S., Seyoum, B., Lulseged, G., & Tadesse, T. (1995). Effect of harvesting stage on yield and quality of natural pasture in the central highlands of Ethiopia. In: Proceedings of third National Conference of the Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP), pp. 316–322, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.