?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Agricultural commercialization stimulates the economic growth of developing nations like Ethiopia. Wheat commercialization in Ethiopia is seen as one way of implementing agricultural transformation strategies to enhance the livelihoods of smallholder households. Despite the production potential and importance of wheat, the level of wheat commercialization and its determinants in the Central Ethiopia region have been unheeded, with prior studies primarily focusing on the Oromia region and northern Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in Lemo district, Hadiya zone, Central Ethiopia region. Both primary and secondary data sources were used, and 155 wheat producers were interviewed. The descriptive and inferential statistics, household commercialization index, and Tobit regression model were used to analyze the data. The results of the study indicated that 11%, 57%, and 32% of respondents were subsistence, semi-commercialized, and commercialized farmers, respectively. The overall intensity of wheat commercialization in Lemo District was 48.92%, which indicates that wheat commercialization is semi-commercialized. Besides, the model result revealed that wheat commercialization was significantly determined by the sex of the household head, household size, landholding, technology adoption, access to market information regarding inputs and output prices, credit utilization, and membership in cooperatives. Hence, commercialization policies need to be crafted to incorporate the implementation of family planning, promote gender-inclusive and market-oriented production, support technology adoption among farmers, offer market intelligence services, ensure the establishment of agricultural credit schemes, and increase the participation of farmers in cooperatives to improve smallholder wheat commercialization and their living standards.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Agriculture is the mainstay of the Ethiopian economy. It serves as a livelihood for the majority of the country’s population. The sector generates income, employment, and foreign exchange earnings. Within the sector, cereal crops mainly contribute to households’ food security and income generation. Wheat is one of the major cereal crops growing in Ethiopia, serving as a staple food and source of income. Even though the country is one of the top wheat-producing countries in Africa, there has been a demand-supply gap over the past decades. The current government of Ethiopia places a special emphasis on cluster-based wheat commercialization to improve the livelihoods of smallholders. Despite this, the level of wheat commercialization among farmers is far below its potential in the country. Hence, studying smallholder wheat commercialization is imperative to improve the livelihood of farm households.

1. Introduction

In Ethiopia, the agriculture sector has a crucial contribution to the socioeconomic development of the nation, as most of the population depends on this sector. As the National Bank of Ethiopia (Citation2022) reported, about 77.2% of the country’s total population lives in rural areas and gets jobs from agriculture. Even though the share of the agriculture sector in the gross domestic product (GDP) is declining from time to time, it remains high. The sector accounted for approximately 32.4% of the total GDP of the country. Crop production takes the lion’s share of the sector which accounts for 65.6% (National Bank of Ethiopia, Citation2022).

Agricultural commercialization stimulates the economic growth of developing nations like Ethiopia. It is one of the priority areas that the government of Ethiopia has been making reformation in the agriculture sector to stimulate rural development and poverty reduction (Alemu & Bishaw, Citation2015; Birhanu et al., Citation2021). However, transforming agriculture from an existing scenario to a market-oriented production system is not an easy task in developing countries like Ethiopia as many factors determine its process. The trends of agricultural commercialization require a paradigm shift in agricultural research priority areas and policy formulation (Pingali, Citation1997). Commercialization of agriculture plays an important role in enhancing economic development and poverty reduction in developing nations, especially countries whose development is based on agriculture (Andaregie et al., Citation2021; Rubhara & Mudhara, Citation2019; Tabe Ojong et al., Citation2022; Timmer, Citation1997; Von Braun & Kennedy, Citation1994). Increasing food production per person and raising rural incomes are the biggest challenges in many African countries (Strasberg et al., Citation1999). Consequently, in the past decades, many developing nations have made different reformations in the agriculture sector to boost production and ensure food security (Von Braun, Citation1995).

Various empirical studies implied that boosting agricultural commercialization has enhanced households’ economic growth and reduced vulnerability to poverty (Ayele, Citation2022; Birhanu et al., Citation2021; Carletto et al., Citation2017; Etuk & Ayuk, Citation2021; Haji, Citation2022; Tabe Ojong et al., Citation2022; Von Braun, Citation1995). A recent study conducted by Birhanu et al. (Citation2021) has shown the decreasing effect of commercialization on multidimensional poverty and vulnerability among farmers. The study indicates that the commercialization of cereal crops has contributed to a reduction in poverty. According to Ayele (Citation2022), the welfare status of smallholder farmers can be improved by any policies and strategies aimed at enhancing smallholder commercialization. Also, the income from output commercialization allows smallholders to acquire improved technologies from the input market that raise yield per unit of inputs and thus, increase market supply (Birhanu et al., Citation2021). In addition, agricultural commercialization has a spillover effect on other non-farm sectors like input manufacturers and suppliers by creating income sources and employment, thus, stimulating overall economic growth (Ayele, Citation2022). Furthermore, according to Strasberg et al. (Citation1999), agricultural commercialization has a considerable positive impact on the usage of input and crop productivity. Therefore, the effect of agricultural commercialization on farm households’ livelihood is positive and beneficial.

Within the agriculture sector, cereal crops are mainly contributing to income generation, employment, and households’ food security in Ethiopia. Wheat is one of the major cereal crops growing in the country, serving as a staple food and source of income. As recent studies and reports imply, Ethiopia’s wheat production is ranked first in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Anteneh et al., Citation2020; Hodson et al., Citation2020) and third in the entire African continent following Egypt and Morocco (FAOSTAT, Citation2021). In Ethiopia, wheat (Triticum aestivum) is cultivated on a total of about 2.1 million hectares (ha) (Tadesse et al., Citation2022). Recently, the total wheat production and the area under wheat cultivation have increased in the country (Abate et al., Citation2021; Atinafu et al., Citation2022). Even though the country is one of the top wheat-producing countries in Africa, there has been a demand-supply gap over the past decades (Abate et al., Citation2021; Atinafu et al., Citation2022; Shikur, Citation2022). This is because wheat production in Ethiopia is dominated by smallholders under subsistence and rain-fed production (Anteneh et al., Citation2020; Mihretie, Citation2020). Small-scale production by itself is not economically viable for mechanization and efficient resource utilization (Pingali, Citation1997). The transaction cost is also higher in smallholder production than in large farms, as a result, many farmers are not benefiting from their farm activities. Moreover, wheat productivity in Ethiopia is very low compared to the average productivity of African and world major wheat-producing countries (Atinafu et al., Citation2022; FAOSTAT, Citation2021). The main reasons behind this are subsistence farming, low income, lack of modern technologies and slow adoption, small farm size, lack of agribusiness awareness, and poor postharvest handling. Consequently, many Ethiopian farmers are living below the poverty line and remained in a vicious cycle of poverty for several decades. To break the cycle and transform the farming system, agricultural reform programs like wheat commercialization are one of the proposed strategies for improving the households’ income and thus contributing to the country’s emerging economy (Alemu & Bishaw, Citation2015).

In Ethiopia, the wheat commercialization program is aimed at improving the livelihood of different actors engaged in the wheat value chain. Several studies confirmed that wheat commercialization plays an important role in poverty reduction, job creation, income generation, meeting household consumption needs, and ensuring food security (Abate et al., Citation2021; Mihretie, Citation2020; Muche & Tolossa, Citation2022; Tabe Ojong et al., Citation2022; Tadesse et al., Citation2022). Wheat commercialization involves a shift from subsistence production to a market-oriented production and consumption system that leads to the strengthening of the linkages between the input and output sides of a market (Pingali, Citation1997; Rubhara & Mudhara, Citation2019; Tabe Ojong et al., Citation2022; Von Braun & Kennedy, Citation1994). It is expected to play a direct role in increasing the productivity and profitability of farmers (Von Braun & Kennedy, Citation1994). In another expression, the wheat commercialization start-up in Ethiopia is believed to increase job opportunities, resource use efficiency, households’ income, profitability, and market linkage with producers as well as reduce food insecurity, thus contributing to poverty reduction in Ethiopia. Thus, the government of Ethiopia has emphasized wheat commercialization and export-oriented production based on the comparative advantage the country has on its resource use to improve smallholders’ livelihoods and reduce poverty.

Despite the ample significance of wheat commercialization, smallholder farmers in many parts of Ethiopia, including the Lemo District, are still producing wheat as usual and do not sufficiently engage in a market-oriented production system (Tadele et al., Citation2017). Traditionally, they produce wheat as a staple food and sell whatever quantity remains after fulfilling the needs of household consumption. Consequently, they are not obtaining sufficient incentives from wheat production. Still, they are earning lower net income and suffering from food insecurity. Besides, no previous empirical studies have been done to explore why smallholder farmers in Lemo District could not get the benefits of wheat commercialization over the past years. Some previous wheat commercialization studies, for example, Andualem (Citation2017), Tadele et al. (Citation2017), Endalew et al. (Citation2020), Mihretie (Citation2020), and Abate et al. (Citation2021) were conducted in different parts of Ethiopia. However, these studies were primarily carried out in the Oromia regional state and northern part of Ethiopia and did not cover the south-central part of Ethiopia where the current study was conducted. In this regard, existing studies have limited spatial coverage to provide adequate information to make a sound wheat commercialization policy at the national level that requires different socio-economic, location-specific, institutional, and agroclimatic real information. As indicated by Tabe Ojong et al. (Citation2022), given the heterogeneous and location-specific variation of smallholder agricultural commercialization, new and diverse insights are warranted to effectively offer policy directions to bring the intended agricultural transformation to the whole country. These can be achieved when research is continuously done to discover new knowledge and bring problem-solving solutions for specific problems on the ground. Therefore, the current study was conducted to generate useful information from different socio-economic and spatial backgrounds with updated recent data to examine the smallholders’ wheat commercialization extent and factors determining wheat commercialization in the study area. Hence, the current study is believed to contribute to an additional understanding of the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization and aid in designing smallholder wheat commercialization-enhancement policies and programs at different levels in the country by bringing insights based on the context of the study area.

2. Literature review

2.1. Agricultural commercialization and its role in developing countries

Many countries have seen substantial economic progress as a result of advancement in the agriculture sector. Agriculture serves as a source of generating income, employment, and foreign exchange earnings (Von Braun, Citation1995). The development of the agriculture sector and its commercialization would have crucial effects on poverty reduction and improving the livelihood of the rural population. Various empirical evidence revealed that agricultural commercialization plays a great role in the emerging economies of many nations in the world. The transition from subsistence to commercial production is key to economic growth (Carletto et al., Citation2017). Von Braun and Kennedy (Citation1994) pointed out that farmers’ income can be increased when they engage in export-oriented agricultural production. According to Ochieng et al. (Citation2016), farm intensification, food security, and farm incomes have all been linked to the commercialization of agriculture in Africa. Olwande et al. (Citation2015) said that the commercialization of smallholder agriculture is one of the effective ways to boost rural economies by increasing farmers’ income and employment opportunities in Sub-Saharan Africa. For example, Ochieng et al. (Citation2016) undertook a study to determine whether commercialization might boost the intensification and yield of bananas and legumes in central Africa. The results demonstrate that commercialization has a beneficial impact on increased seed variety use and food crop yields. Consequently, agricultural commercialization is considered one of the reformation policy directions that many African countries including Ethiopia use as a pathway for overall socio-economic development.

2.2. Wheat production and its demand in Ethiopia

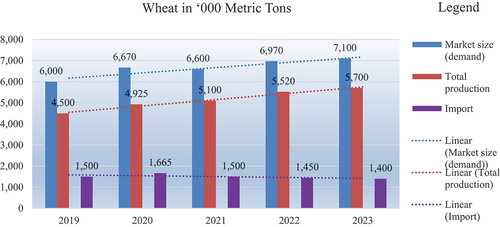

Ethiopia has great potential for wheat production even though its current productivity is far below from world’s average wheat productivity. Through time the country’s total wheat production and productivity are increasing due to start-ups using advanced technologies. The domestic demand for wheat is greater than its domestic supply and the country has been importing wheat from the international market to fill its gap. But currently, the government of Ethiopia has due more attention to wheat production and has an ambitious plan for wheat self-sufficiency and pausing importation. For the 2023 fiscal year, the government promised to begin wheat exporting to neighboring countries. However, based on the estimated volume of domestic demand for wheat, domestic production is not sufficient to meet the need and still 1.4 million metric tons might be imported from abroad (USDA, Citation2022).

As shown in Figure , despite increased wheat production, Ethiopia still may remain a net importer. Wheat domestic demand and production are shown as an increasing trend line while wheat importation decreased steadily. This implies that there is a high domestic demand for wheat due to high population growth that requires more food items for consumption and multipurpose end uses of wheat in emerging agro-processing industries.

Figure 1. Wheat market size, total production, andimport-export estimated volume in Ethiopia.

As the country’s economy expands and the population grows, the demand for wheat and its products like pasta, macaroni, bread, cake, injera, and so on is also expected to increase. This is an indication of the presence of high potential for the commercialization of wheat in Ethiopia. Therefore, identifying the major bottlenecks of commercialization is crucial for giving solutions and bringing market-oriented agricultural production including wheat.

2.3. Empirical studies on commercialization

Commercialization of wheat involves a transition from subsistence-oriented to increasingly market-oriented patterns of production and input use (Rubhara & Mudhara, Citation2019). Separation of a household’s decision of production and consumption begins at the same moment commercialization commences. Household decision-making for production and consumption is non-separable in subsistence farming while it is separable in market-oriented farming. In situations where decisions are non-separable, the objective of the household is to maximize utility and where it is completely separable, the objective is to maximize profit. The behavior of households in between the above two situations is guided by a mixture of two objectives directed at utility, on one side, and profit, on the other side. Commercialization helps not only large-scale farm production but also encourages smallholder farmers to shift their production system toward business-oriented farm ventures through intensive farming. Commercialization of agriculture in general and wheat commercialization in particular inevitably benefits farmers in different dimensions.

However, the process of commercialization of agriculture in most developing countries including Ethiopia is being confined by various factors (Andaregie et al., Citation2021). Low agricultural commercialization in Ethiopia is attributed to poverty, resource degradation, adverse climate, small-scale landholding, insufficient production, lack of mechanization, lack of business awareness, lack of linkage to commodity markets, limited investment in research and development, low government expenditure, and limited access to institutional facilities and advanced technologies (Abate et al., Citation2021; Anteneh et al., Citation2020; Endalew et al., Citation2020; Ketema & Lika, Citation2023; Mihretie, Citation2020; Tadele et al., Citation2017; Yigezu Wendimu & Tejada Moral, Citation2021).

Several studies analyzed agricultural commercialization among farm households (Alemu & Bishaw, Citation2015; Andaregie et al., Citation2021; Ayele et al., Citation2021; Haji, Citation2022; Pingali & Rosegrant, Citation1995; Tabe Ojong et al., Citation2022; Von Braun, Citation1995; Von Braun & Kennedy, Citation1994). The studies were conducted at various places over different periods by employing various analytical methods depending on the objectives and nature of the data set. The results of some of the reviewed studies are presented as follows. Alemu and Bishaw (Citation2015) found that smallholder wheat producers’ commercial behavior is influenced by internal and external factors such as household characteristics, socioeconomic conditions, research outputs, and government expenditure. Andaregie et al. (Citation2021) studied the determinants of market participation decisions by smallholder haricot bean farmers in Northwest Ethiopia. The result implies that haricot bean market participation and market supply are influenced by various demographic, socioeconomic, and institutional factors. Von Braun and Kennedy’s (Citation1994) case studies in developing countries report that agricultural commercialization can boost economic development through employment and income growth, improving nutrition, particularly for the poor. The study by Pingali and Rosegrant (Citation1995) recommends government policy directions for agricultural commercialization and diversification, including investment in rural development infrastructure, research, secure resources, and market liberalization. Olwande et al. (Citation2015) studied Kenyan smallholder agricultural marketing, revealing strong associations between market participation, land access, productive assets, technology adoption, expected prices, and rainfall. They suggested interventions to increase marketable surplus and productivity. Tabe Ojong et al. (Citation2022) found that agricultural commercialization in Ethiopia benefits all farmers, with asset-rich farmers experiencing higher benefits.

Furthermore, many wheat commercialization studies have been carried out by scholars in various parts of the world. For example, in Ethiopia, several studies (such as Tadele et al., Citation2017; Endalew et al., Citation2020; Mihretie, Citation2020; Regasa Megerssa et al., Citation2020, Abate et al., Citation2021; Atinafu et al., Citation2022; Ayele, Citation2022; Ketema & Lika, Citation2023; Tafesse et al., Citation2023) have been conducted on wheat commercialization using different econometric models. However, these studies have unevenly addressed all potential wheat production areas of the country. Despite the production potential and importance of wheat, the level of wheat commercialization and its determinants in the Central Ethiopia region have been unheeded, with prior studies primarily focusing on the Oromia region and northern Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by analyzing the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in the Lemo district of Hadiya Zone, Central Ethiopia region, where high wheat production potential is prevalent and the majority of smallholder farm households are engaging in its production. To attain the study objectives, this study used a maximum likelihood approach called a Tobit regression model in combination with a household commercialization indexing approach and descriptive and inferential statistics.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Description of the study area

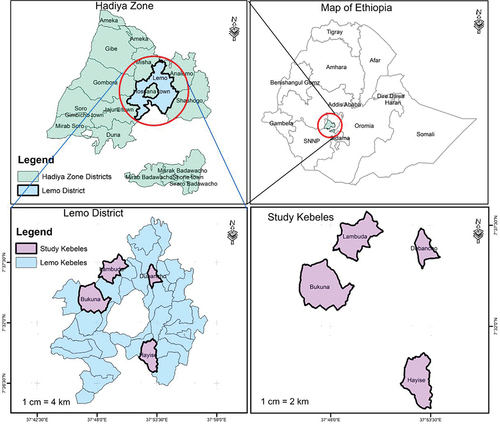

This study was conducted in Lemo District, Hadiya Zone, Central Ethiopia Regional State, Ethiopia. The map of Lemo District and selected sample kebeles are shown in Figure . The district is made up of 33 rural kebelesFootnote1 and 2 rural town administrations. The district is suitable for both crop and livestock production. Given the fact that the district has suitable agroecology for agricultural production, the majority of rural households are engaged in a mixed farming system. Smallholder farmers produce different agricultural commodities including cereal crops, legumes, horticultural crops, livestock, equines, poultry, and beehives. Among the cereal crops, wheat is one of the most grown crops by smallholder farmers in the study area. Wheat serves as a source of income generation, employment, and means of fulfilling household food consumption needs (Abate et al., Citation2021; Tabe Ojong et al., Citation2022; Tadesse et al., Citation2022).

3.2. Sampling technique and sample size determination

A multi-stage sampling technique was used sequentially to select the respondent household heads in the study area. In the first stage, Lemo District was purposefully selected based on its high potential for wheat production and marketing. In the second stage, out of the total rural kebeles of the district, four kebeles namely Bukuna, Dubancho, Hayise, and Lambuda were randomly selected. In the third stage, the total household heads of the district were categorized into two groups: wheat-producing and non-producing smallholder households during the 2021/22 crop production year. Out of 33,101 total households in Lemo District 26,172 households were wheat-producing households, the sampling frame, and the remaining 6,929 households were non-wheat producers in that particular year. Then, the respondents were chosen at random in proportion to the number of wheat-producing household heads in each kebele (Table ). Finally, a total of 155 sampled smallholder household heads were considered for data collection.

Table 1. Sampling procedure

In the study, the sample size was determined using the formula developed by Yamane (Citation1967), as indicated below:

Where, N = Target population; n = Sample size; e = Precision level (for this study it was taken 8%)

3.3. Source and method of data collection

The study was conducted based on both primary and secondary data sources. A cross-sectional household survey was conducted to gather primary data from smallholder wheat producers in the study area. The primary data were collected by preparing a semi-structured questionnaire and with the help of enumerators after giving necessary training. The questionnaire was pre-tested and amended by conducting a pilot survey on 15 farm households in another Misha District since households have more or less similar socioeconomic characteristics to Lemo District. In addition to the survey, key informant interviews and focus group discussions were undertaken to triangulate the data and generate overall information about wheat commercialization in the study area. The secondary data were obtained from published documents, database websites, and annual reports.

3.4. Method of data analysis

The data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics as well as an econometric model. Descriptive statistics like mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, percentage, and frequency were used to explain the respondent households’ demographic and socio-economic characteristics as well as institutional factors included in the study. To test the association between variables, the chi-square test and t-test were used for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively.

The study adopted the household commercialization index (HCI) to determine the level of wheat commercialization by producing households in the study area. The HCI has been widely used in several previous studies of smallholder commercialization involving one or more crops (Abate et al., Citation2021; Ayele et al., Citation2021; Birhanu et al., Citation2021; Carletto et al., Citation2017; Endalew et al., Citation2020; Rahut et al., Citation2010; Rubhara & Mudhara, Citation2019; Strasberg et al., Citation1999; Von Braun & Kennedy, Citation1994). It measures the ratio of the value of wheat sales by farmer in year

to the value of the wheat produced by the same farmer

in the same year

, which can be expressed in terms of a percentage. The HCI can be specified as follows:

The value of the wheat produced by a household can be estimated by multiplying the quantity of wheat produced by the selling price. The value of a wheat crop sold by a household is estimated by multiplying the quantity of wheat sold by the selling price. The index is then calculated for each household and ranked to categorize households into three groups namely subsistence, semi-commercialized, and commercialized (Andualem, Citation2017; Ayele, Citation2022; Ayele et al., Citation2021; Endalew et al., Citation2020). This depends on the value of . The value of

ranges from 0 to 1, which indicates entirely subsistent and fully commercialized farm households, respectively. It captures the variation in terms of the intensity of wheat commercialization across households. There is no fixed uniform way to categorize the commercialization level, and various studies have used their classification categories (Ayele et al., Citation2021; Endalew et al., Citation2020; Tadele et al., Citation2017). In the present study, following the previous studies of Andualem (Citation2017) and Endalew et al. (Citation2020), wheat farmers were categorized into three: subsistence ([0, 25%]), semi-commercialized ((25%, 50%]), and Commercialized (>50%). An index value closer to 0 indicates the smallholder farmer is subsistence-oriented and closer to 100% implies a higher level of commercialization.

In addition, an econometric model was also used to examine the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in Lemo District. In the study, the dependent variable, wheat commercialization is a limited dependent variable that took the value of “0” when a household did not sell any quantity of wheat and a “positive value” when a household did sell a certain quantity of wheat produced. In such conditions, different econometric models like Tobit, Heckman selection, and double hurdle can be employed depending on their relevance after checking the fitness of model tests. Based on the nature of the data set and model test results such as Akaike information criteria, Bayesian information criteria, and likelihood ratio test, the appropriate model considered for this study was the Tobit regression model. The Tobit regression model is a limited dependent variable model that helps to realize the probability of wheat commercialization decisions and the extent of wheat commercialization in the study area. The model is used when the dependent variable assumes the same value for a considerable number of observations and a continuous value for others. The model in the context of this study assumes that both the decision to commercialize and the extent of commercialization are determined by the same variables with the same sign, i.e., the variables that increase the probability of commercialization also increase the extent of commercialization. This model suits such kinds of analysis as it enables one to examine the effect of different explanatory variables on a limited dependent variable. The Tobit model has been used by several previous commercialization studies (Kabiti et al., Citation2016; Mihretie, Citation2020; Rubhara & Mudhara, Citation2019; Tadele et al., Citation2017; Tafesse et al., Citation2020).

The Tobit model is estimated by assuming a correlation between the unobservables affecting households’ decisions to sell and their decisions on how much to sell. The Tobit model uses the maximum likelihood method to execute the estimation. It is specified as follows:

, if

and

, otherwise

Where, is the observed value (i.e., the quantity of wheat sold),

is a latent variable describing factors influencing the quantity of wheat sold by farmers,

is the vector of variables explaining the quantity of sale,

is the vector of estimates of parameters, and

is the disturbance term. The hypothesized variables used in the model are summarized in Table .

Table 2. The summary of explanatory variables used in the model

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Household characteristics

Out of the total respondents about 79% were male-headed households and the remaining 21% were female-headed households. As the result of the study shows, male-headed households had a greater proportion of wheat market participation than female-headed households (Table ). This result is consistent with the finding of Adong et al. (Citation2014) in which male-headed households sold more farm products than female-headed households. The average age of the sample household heads was about 46.3 years with a maximum of 72 years and a minimum of 29 years. The educational level of the respondents has also shown an important effect in the process of wheat commercialization decision-making by the households in the study area. About 23.87% of total respondents and 18.12% of market participants were not formally educated household heads in the survey. The findings in Table show a positive relationship between educational level and commercialization decisions. It was shown that the more educated household heads had relatively better wheat commercialization participation than the less educated household heads. A similar finding was also reported by previous studies (Abate et al., Citation2021; Olwande et al., Citation2015; Tafesse et al., Citation2020).

Table 3. The proportion test of dummy variables

Table 4. An analysis of the t-test for continuous variables

4.2. Socioeconomic factors

Land is one of the most important and scarce resources that need efficient allocation in agricultural production. In the study area, there is an acute land shortage due to high population density. It is the main discriminating variable among farm households. The average households’ landholding in the study area was 0.88 ha which is less than the households’ average national landholding of 1 ha. The land is the main constraint in providing adequate output and farm income, which in turn determines the living conditions of farm households. In the current study, the size of landholding has shown a positive and significant association with wheat participation decisions. A similar finding was also reported by several studies (Abafita et al., Citation2016; Olwande et al., Citation2015; Tafesse et al., Citation2020). The quantity of wheat production has greatly influenced the households’ wheat commercialization decisions. The t-test result showed that the quantity of wheat production had a positive association with wheat commercialization decisions. There was a statistically significant wheat production mean value difference between the two groups at a 1% significance level. Other studies also confirm a positive relationship between quantity production and market participation decisions (Andualem, Citation2017; Kabiti et al., Citation2016; Mihretie, Citation2020; Tadele et al., Citation2017).

The main sources of income for the households in the study area were derived from farm, off-farm, and non-farm income activities. Based on the existing situation and prevailing agricultural price levels, the respondent farm households obtained an average annual income of 73,022.58 ETB in the survey year. The key informant interview revealed that the households’ annual income level has been increasing from time to time for various reasons. The main reasons they pointed out were increasing market demand and rising prices for agricultural products, including wheat; having access to non-farm income sources like remittances from one or more family members; and increasing the engagement of household members in off-farm activities such as petty trade, laborer, carpeting, and so on. As the t-test result indicated, annual household income had a negative and significant effect on the wheat commercialization decision in the study. This reveals that the farm households who could earn a higher income might not sell wheat to generate cash income, but rather they might use it for household consumption.

4.3. Institutional factors

Financial resources are a key input for the commercialization of agriculture in general and the wheat crop. Finances can be obtained either through personal savings or borrowing. In the study area, smallholder farm households can obtain credit either from the semi-formal or informal sectors (Ayele & Goshu, Citation2018). The same source pointed out that microfinance institutions and informal local moneylenders are major sources of credit for farmers. Smallholders require credit mainly for the purchase of farm inputs and for starting small businesses like petty trade. In the current study, the Chi-square test result has shown a positive and significant association between credit utilization and wheat commercialization. Similar findings are also reported by previous studies (Rubhara & Mudhara, Citation2019; Tafesse et al., Citation2023). Market information about product price, product quality, and buyers’ demand plays a vital role in the marketing function. Farm producers cannot get market information with certainty. Price fluctuation and high dependency on biophysical factors like weather conditions limit farmers’ knowledge about marketing functions. In the study, access to market information has shown a positive and statistically significant association with wheat market participation at a 1% significance level. Tafesse et al. (Citation2023) also reported a similar positive relationship between access to market information and maize market participation.

4.4. Wheat commercialization in the study area

In the district, most of the smallholder farm households were producing wheat in the study period. As shown in Table , the average productivity of wheat for the survey year was found to be 27.25 Qt/ha which was lower than the average wheat productivity at the national level of 27.64 Qt/ha and higher than the average productivity of wheat at the regional level of 26.65 Qt/ha (Tadesse et al., Citation2021).

Table 5. The result of the respondents’ wheat production statistics in the study area

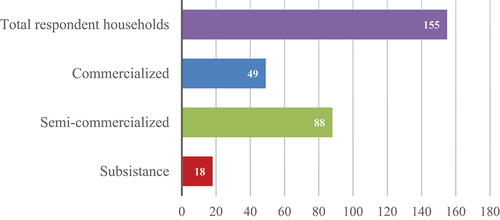

In the study, the respondents were placed in three categories, but the majority were found in the semi-commercialized wheat production category (Figure ). The HCI result revealed that 11%, 57%, and 32% of respondent smallholders were subsistence, semi-commercialized, and commercialized wheat producers, respectively. Other similar studies also use these categories (Andualem, Citation2017; Endalew et al., Citation2020). The overall level of wheat commercialization in the study area was found to be 48.92%. This indicates that the degree of wheat commercialization in the study area was semi-commercialized. It implies that some adjustment towards improving the commercialization level in the study area is essential for the further betterment of farmers’ living standards. It needs the consideration of decision-makers at different levels by giving attention to the key influential factors that encumber wheat commercialization in the study area.

4.5. Determinants of wheat commercialization

The major factors that were hypothesized to influence wheat commercialization in the study area are analyzed using the Tobit regression model (Table ). Out of the fourteen variables included in the model, about six variables were found to be statistically significant in determining wheat commercialization in the study area. There are household-specific characteristics, socio-economic factors, and institutional factors that have significantly influenced wheat commercialization in the study area.

Table 6. Determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization (Tobit regression model results)

The model result indicates that sex of the household head was found to be a statistically significant determinant of smallholder households’ wheat commercialization in the study area. It has shown a positive effect on households’ commercialization decisions indicating that male-headed households are more likely to participate in smallholder wheat commercialization than female-headed households. The marginal effect result indicates that being a male-headed household increases the probability of smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area by 10.03% at a 1% significance level. The result is consistent with the findings of Andaregie et al. (Citation2021), Ayele et al. (Citation2021), and Rubhara and Mudhara (Citation2019). These studies give insight into how being a male-headed household is positively correlated with smallholder commercialization decisions and how male-headed households are more likely to grow more labor-intensive cash crops and participate in the market than female-headed households. Another reason mentioned by Tafesse et al. (Citation2023) for the higher market participation of male-headed households than their counterparts is that female-headed households might have less information access than male-headed households due to the male-dominated culture in developing countries like Ethiopia.

Household size was hypothesized to influence smallholder wheat commercialization either positively or negatively. The household size was found to negatively influence wheat commercialization among smallholder farmers in the study area. As the family size increases, the wheat consumption needs also increase, keeping other things constant. In labor-intensive agricultural production, even though the quantity produced by the larger household size is greater than the smaller household size, the extent of market participation is also lesser than the counterpart smaller household size due to the higher consumption needs of the produced output by the larger size of household members. The marginal effect result shows that an increase of household size by 1 adult equivalent reduces the probability of the smallholder households’ wheat commercialization in the study area by 2.2% and it is significant at a 5% significance level. This result is in line with the previous findings of Regasa Megerssa et al. (Citation2020) and Tadele et al. (Citation2017). In contrast, Tafesse et al. (Citation2023) reported a positive relationship between maize market participation and household size, but they also reported a negative relationship between household size and the amount of maize supplied to the market.

Adoption of modern and improved technologies such as high-yielding varieties of seed, fertilizers, improved production techniques like raw planting, use of irrigation water, use of plant protection measures, modern tools and equipment, and postharvest technologies are very important to increase yield, farm income, and food security. As expected in the prior hypotheses, technology adoption in the Tobit regression model has shown a positive and statistically significant effect on smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area. The marginal effect of this variable indicates being a technology adopter increases the probability of smallholder wheat commercialization by 8.5% at a 1% significance level. As the technology adoption by farm households increases, the yield level also increases and this will result in a larger quantity of market supply and boost wheat commercialization by the smallholder households. This result is in line with the findings of Olwande et al. (Citation2015) in which the use of advanced production technologies such as hybrid maize seed, fertilizer, and improved cattle breeds showed a positive effect on smallholder market participation in Kenya. The result confirmed that the adoption of modern technologies promotes market participation of smallholders.

Agricultural credit is a crucial input for farm households to increase farm production and productivity. Whenever farmers face a shortage of cash for their farm activities, they fulfill it by making use of credit. In the present study, credit utilization was found to be an important determining factor of smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area. As the marginal effect result shows, being a credit user by farm households increases the probability of smallholder wheat commercialization by 6.6%. It is indicated that agricultural credit utilization by farm households is positively and significantly related to smallholder wheat commercialization at a 5% significance level. This is because credit utilization helps farmers acquire essential farm inputs for production and aids in supplying a higher quantity of farm products to the market by enabling them to cover transportation and other related costs. Similar findings reported by Andualem (Citation2017), Tadele et al. (Citation2017), Rubhara and Mudhara (Citation2019), and Tafesse et al. (Citation2023) also indicated that farm households who have access to finance and use credit are more market-oriented than those who do not. This is because credit users can buy better productive inputs and hire more laborers that help the farmers supply higher outputs to the market.

Market information is also another important business-oriented farm production and helps farmers in various ways. Farm households require market information on inputs and output prices to make the right decision at different stages starting from the pre-production stage up to selling the final output. Market information is needed ahead of the production season to decide what crops to produce and how much quantities are to be produced by the farm households. Even after harvesting farm outputs, it is again very important to decide market participation decision and its intensity. In the current study, the model result indicated that smallholder wheat commercialization is positively and significantly related at a 5% significance level. The marginal effect result indicates that having access to market information by farm households increases the probability of smallholder wheat commercialization by 8.6% in the study area. This result is consistent with the findings of Abate et al. (Citation2021) and Regasa Megerssa et al. (Citation2020).

Participation in cooperatives facilitates acquiring farm inputs and selling of output by giving the market bargaining power to the members. In the study, membership in cooperatives was found to be a positively related and statistically significant determining factor of smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area at a 5% significance level. The reason for the positive relationship between membership in cooperatives and smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area is that as households participate in cooperatives for inputs purchasing and output selling, the transaction costs can be reduced and market bargaining power can be also increased which would enable farmers to earn a higher level of farm income. As a result, those households who are members of cooperatives show greater wheat commercialization than their counterparts non-members. The marginal effect result implies that membership in cooperatives increases the probability of smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area by 8.2%. Similarly, Andaregie et al. (Citation2021), Mihretie (Citation2020), Tafesse et al. (Citation2023), and Tasila Konja and Mabe (Citation2023) reported a positive and significant association between membership in cooperatives and market participation.

4.6. Limitations of the study and areas for further research

The present study analyzed the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in Lemo District, Ethiopia using the household commercialization index and Tobit regression model. The study was limited to examining wheat commercialization merely from an output marketing perspective side. In addition, the study analyzed the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization based on cross-sectional survey data which does not allow for consideration of an intertemporal variation of farm households’ commercialization decisions. Hence, the study suggests upcoming research to take into account emphasizing both the input and output sides of measuring commercialization and the use of longitudinal data that show determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in intertemporal periods.

5. Conclusion and policy options

The study was conducted to analyze the determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in Lemo District, Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. A cross-sectional survey was done on randomly selected 155 wheat-producing farm households in the study area. Both descriptive and inferential statistics, HCI, and the Tobit regression model were employed to analyze the data. The results of the study revealed that smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area is not satisfactory as the majority of smallholders’ HCI score is shown on average less than 50 percent. The HCI used as the measure of the extent of smallholder wheat commercialization indicated that about 11%, 57%, and 32% of the total respondents were subsistence, semi-commercialized, and commercialized farmers in the study area, respectively. It indicated that smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area is typically semi-commercialized with an average HCI score of 48.92%. Furthermore, based on the Tobit regression model, the main determinants of smallholder wheat commercialization in the study area are the sex of household heads, household size, technology adoption, credit utilization, market information, and membership in cooperatives. The overall results imply that some corrective measures that would help farmers increase the extent of wheat commercialization in the study area are essential.

Hence, to create an enabling environment for smallholder farmers to enhance wheat commercialization and gain sustainable benefits, the following policy options are put forward to the concerned bodies: (1) promotion and strengthening of market-oriented wheat production, with concurrent support from the government and other development agents, focusing on investment in rural infrastructure development; (2) development and implementation of gender-inclusive and market-oriented wheat production policies aimed at increasing the income levels of female-headed households, thereby reducing poverty and inequality; (3) promotion of technology adoption by bolstering farmers’ training programs and extension services; and (4) emphasis on providing better institutional services, such as timely and updated market information, agricultural financial services, and facilitating the participation of smallholder farmers in cooperatives.

Questionnaire.docx

Download MS Word (27.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2289711

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mahadeo S. Deshmukh

Mahadeo S. Deshmukh (Ph.D.) is a Professor in Economics and Dean of Humanities, at Shivaji University, Kolhapur, India. He is well-recognized for his professional teaching, research, and leadership management affairs. His research interests are sustainable development, livelihood security, agricultural policy analysis, and organic farming.

Amanuel Ayele Gebre

Amanuel Ayele Gebre is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics, at Wachemo University, Ethiopia. He obtained a B.Sc. Degree in Agricultural Resource Economics and Management from Hawassa University and an M.Sc. Degree in Agricultural Economics from Haramaya University, Ethiopia. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. degree in Economics at Shivaji University. His research interests include production economics, agricultural commercialization, food security, efficiency analysis, agricultural finance, value chain analysis, and impact assessment.

Digvijay R. Patil

Digvijay R. Patil (Ph.D.) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics, at Shivaji University, Kolhapur, India. His research interests in Agricultural Economics are agricultural sustainability and livelihood security analysis.

Notes

1. The smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia.

References

- Abafita, J., Atkinson, J., & Kim, C. S. (2016). Smallholder commercialization in Ethiopia: Market orientation and participation. International Food Research Journal, 23(4), 1797–18.

- Abate, D., Mitiku, F., & Negash, R. (2021). Commercialization level and determinants of market participation of smallholder wheat farmers in northern Ethiopia. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation & Development, 14(2), 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1844854

- Adong, A. M., Muhumuza, T., & Mbowa, S. (2014). Smallholder food crop commercialization in Uganda: Panel survey evidence from Uganda. SSRN Electronic Journal, 116, Economic Policy Research Centre. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3902410

- Alemu, D., & Bishaw, Z. (2015). Commercial behaviours of smallholder farmers in wheat seed use and its implication for demand assessment in Ethiopia. Development in Practice, 25(6), 798–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1062469

- Andaregie, A., Astatkie, T., Teshome, F., & Yildiz, F. (2021). Determinants of market participation decision by smallholder haricot bean (Phaseolus vulgaris l.) farmers in Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1879715

- Andualem, G. G. (2017). Determinants of smallholders wheat commercialization: The case of Gololcha District, Bale Zone, Ethiopia [ Master’s thesis]. University of Gonder, National Academic Repository of Ethiopia. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/199937444.pdf

- Anteneh, A., Asrat, D., & Tejada Moral, M. (2020). Wheat production and marketing in Ethiopia: Review study. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1778893. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1778893

- Atinafu, A., Lejebo, M., & Alemu, A. (2022). Adoption of improved wheat production technology in gorche District, Ethiopia. Agriculture & Food Security, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00343-4

- Ayele, T. (2022). Cereal crops commercialization and welfare of households in Guji Zone, Ethiopia. Heliyon, 8(9), e10687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10687

- Ayele, T., Goshme, D., Tamiru, H., & Tejada Moral, M. (2021). Determinants of cereal crops commercialization among smallholder farmers in Guji Zone, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1948249

- Ayele, A., & Goshu, D. (2018). Determinants of microfinance loan utilization by smallholder farmers: The case of omo microfinance in Lemo District of Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 10(7), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.5897/jdae2016.0726

- Birhanu, F. Z., Tsehay, A. S., & Bimerew, D. A. (2021). The effects of commercialization of cereal crops on multidimensional poverty and vulnerability to multidimensional poverty among farm households in Ethiopia. Development Studies Research, 8(1), 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2021.2002704

- Carletto, C., Corral, P., & Guelfi, A. (2017). Agricultural commercialization and nutrition revisited: Empirical evidence from three African countries. Food Policy, 67, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.020

- Endalew, B., Aynalem, M., Assefa, F., & Ayalew, Z. (2020). Determinants of wheat commercialization among smallholder farmers in Debre Elias Woreda, Ethiopia. Advances in Agriculture, 2020, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2195823

- Etuk, E. A., & Ayuk, J. O. (2021). Agricultural commercialisation, poverty reduction and pro-poor growth: evidence from commercial agricultural development project in Nigeria. Heliyon, 7(5), e06818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06818

- FAOSTAT. (2021). https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL

- Haji, J. (2022). Impact of agricultural commercialization on child nutrition in Ethiopia. Food Policy, 113, 102287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102287

- Hodson, D. P., Jaleta, M., Tesfaye, K., Yirga, C., Beyene, H., Kilian, A., Carling, J., Disasa, T., Alemu, S. K., Daba, T., Misganaw, A., Negisho, K., Alemayehu, Y., Badebo, A., Abeyo, B., & Erenstein, O. (2020). Ethiopia’s transforming wheat landscape: Tracking variety use through DNA fingerprinting. Scientific Reports, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75181-8

- Kabiti, H., Raidimi, N., Pfumayaramba, T., & Chauke1, P. (2016). Determinants of Agricultural Commercialization among Smallholder Farmers in Munyati Resettlement Area, Chikomba District, Zimbabwe. Journal of Human Ecology, 53(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2016.11906951

- Ketema, S., & Lika, T. (2023). Determinants of market outlet choice by smallholder wheat producers in Arsi Zone of Oromia National regional State, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2022.2163578

- Mihretie, Y. A. (2020). Smallholder wheat farmers’ commercialization level and its determinants in northwestern Ethiopia. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation & Development, 13(5), 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1773202

- Muche, M., & Tolossa, D. (2022). Comparative analysis of household food insecurity between selected coffee and wheat growers of Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2022.2149134

- National Bank of Ethiopia. (2022). 2021/22 annual report. https://nbe.gov.et/annual-report/

- Ochieng, J., Knerr, B., Owuor, G., & Ouma, E. (2016). Commercialisation of food crops and farm productivity: Evidence from smallholders in Central Africa. Agrekon, 55(4), 458–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2016.1243062

- Olwande, J., Smale, M., Mathenge, M. K., Place, F., & Mithöfer, D. (2015). Agricultural marketing by smallholders in Kenya: A comparison of maize, kale and dairy. Food Policy, 52, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.02.002

- Pingali, P. L. (1997). From subsistence to commercial production systems: The transformation of Asian agriculture. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(2), 628–634. https://doi.org/10.2307/1244162

- Pingali, P. L., & Rosegrant, M. W. (1995). Agricultural commercialization and diversification: processes and policies. Food Policy, 20(3), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(95)00012-4

- Rahut, D. B., Castellanos, I. V., & Sahoo, P. (2010). Commercialization of agriculture in the Himalayas. Discussion Paper No. 265. Institute of Development Economics (IDE)-JETRO.

- Regasa Megerssa, G., Negash, R., Bekele, A. E., Nemera, D. B., & Yildiz, F. (2020). Smallholder market participation and its associated factors: Evidence from Ethiopian vegetable producers. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1783173. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1783173

- Rubhara, T., & Mudhara, M. (2019). Commercialization and its determinants among smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. A case of Shamva District, Mashonaland Central Province. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation & Development, 11(6), 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2019.1571150

- Shikur, Z. H. (2022). Wheat policy, wheat yield and production in Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2079586

- Strasberg, P. J., Jayne, T. S., Yamano, T., Nyoro, J., Karanja, D., & Strauss, J. (1999). Effects of agricultural commercialization on food crop input use and productivity in Kenya. MSU International Development Working Paper No. 71. Michigan State University,

- Tabe Ojong, M. P. J., Hauser, M., & Mausch, K. (2022). Does agricultural commercialisation increase asset and livestock accumulation on smallholder farms in Ethiopia? The Journal of Development Studies, 58(3), 524–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2021.1983170

- Tadele, M., Wudineh, G., Agajie, T., Ali, C., Tesfaye, S., Aden, A. H., Tolessa, D., & Solomon, A. (2017). Analysis of wheat commercialization in Ethiopia: The case of SARD-SC wheat project innovation platform sites. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 12(10), 841–849. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajar2016.11889

- Tadesse, B., Tilahun, Y., Bekele, T., & Mekonen, G. (2021). Assessment of challenges of crop production and marketing in Bench-Sheko, Kaffa, Sheka, and west-omo zones of southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon, 7(6), e07319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07319

- Tadesse, W., Zegeye, H., Debele, T., Kassa, D., Shiferaw, W., Solomon, T., Negash, T., Gelete, N., Bishaw, Z., & Assefa, S. (2022). Wheat production and breeding in Ethiopia: Retrospect and prospects. Crop Breeding, Genetics and Genomics. https://doi.org/10.20900/cbgg20220003

- Tafesse, A., Gechere, G., Asale, A., Belay, A., Recha, J. W., Aynekulu, E., Berhane, Z., Osano, P. M., Demissie, T. D., & Solomon, D. (2023). Determinants of maize farmers market participation in Southern Ethiopia: Emphasis on demographic, socioeconomic and institutional factors. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2191850

- Tafesse, A., Megerssa, G. R., Gebeyehu, B., & Yildiz, F. (2020). Determinants of Agricultural commercialization in Offa District, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1816253. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2020.1816253

- Tasila Konja, D., & Mabe, F. N. (2023). Market participation of smallholder groundnut farmers in northern Ghana: Generalised double-hurdle model approach. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2202049

- Timmer, C. P. (1997). Farmers and markets: The political economy of new paradigms. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(2), 621–627. https://doi.org/10.2307/1244161

- USDA. (2022) . USDA/Foreign Agriculture Service. Addis Ababa.

- Von Braun, J. (1995). Agricultural commercialization: Impacts on income and nutrition and implications for policy. Food Policy, 20(3), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(95)00013-5

- Von Braun, J. V., & Kennedy, E. (Eds.). (1994). Agricultural commercialization, economic development, and nutrition. Johns Hopkins Press.

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics: An introductory analysis (2nd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Yigezu Wendimu, G., & Tejada Moral, M. (2021). The challenges and prospects of Ethiopian agriculture. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1923619