SUMMARY

In Benin, vegetable production contributes significantly to food security and poverty reduction. However, vegetable farming is confronted with declining soil fertility, poor pest and disease management, and climate change. Agroecological farming offers a new paradigm of sustainable agri-food systems that counters these challenges. From August to December 2015, farmer training videos (FTVs) were sold to enable farmers to learn about agroecological techniques. In October 2022, we interviewed a sample of 180 vegetable farmers in four municipalities where the FTVs were sold, to find out which technical and organizational innovations were familiar to, and had been adopted by farmers. The interviews were followed by focus group discussions with farmers to gain further understanding of the social dynamics that contributed to changes in farming practices, as well as to identify relevant socioeconomic and ecological indicators at the household level in relation to the five sustainable livelihood capitals. A field visit was organized to gather further evidence of the changes in practices reported during the interviews and focus group discussions. This study revealed that about seven years after FTVs were distributed, the proportion of conventional vegetable growers decreased from 95.5% to 51%, while agroecological vegetable growers increased from 4.5% to 30% and 19% of the famers started growing organic vegetables. Farmers were motivated to embrace sustainable vegetable methods for financial and health reasons. The study also showed how farmers’ association played a key role in creating favorable conditions for the development of sustainable (agroecological and/or organic) farming. The FTVs taught agroecological knowledge to farmers, many of whom were able to put these ideas into practice.

Introduction

Agriculture is one of the most important sectors of the economy of Benin, employing more than 70% of the people and accounting for about 36% of the country’s GDP (World Bank, Citation2019). Conventional vegetable production across Benin contributes to food security and poverty reduction (MAEP, Citation2017). However, conventional vegetable cultivation is sensitive to pests, diseases and extreme weather, especially high temperatures (Zoundji et al., Citation2018a).

Conventional farmers are now using larger volumes of insecticides, fungicides, herbicides and chemical fertilizers on vegetables than on cotton, which has seriously harmed the environment and human health (Singbo et al., Citation2015; Williamson et al., Citation2008). The excessive use of synthetic pesticides also has negative effects on the effectiveness of pest control (El-Sheikh et al., Citation2022; Williamson et al., Citation2008).

Agroecological or organic agriculture is gaining importance in the international debate on food systems (Pretty & Bharucha, Citation2014). Agroecology and organic farming are sometimes used interchangeably because both strive to reduce the use of synthetic chemical inputs. In this paper, we consider agroecological and organic agriculture to both two different types of ‘sustainable’ farming. Organic agriculture is certified. It is strictly regulated by defined standard that describe which products can be certified and marketed as organically produced (HLPE, Citation2019). Agroecological practices aim ‘to produce significant amounts of food while valuing ecological processes and ecosystem services by integrating them as fundamental elements’ (Wezel et al., Citation2014). Agroecological practices are knowledge-intensive and tailored to local ecological conditions (D’Annolfo et al., Citation2020; Paparu et al., Citation2017; Van den Berg et al., Citation2018). These practices often combine traditional farming practices and modern science, allowing the optimal management of nature’s ecological functions and biodiversity while reducing dependency on external inputs and improving farming systems (D’Annolfo et al., Citation2020; Duru et al., Citation2015; Van den Berg et al., Citation2018). Farmers’ access to, and use of reliable information and knowledge is crucial for successful promotion of agroecology (Zoundji et al., Citation2016). However, the traditional approach of providing agricultural information through under-funded and poorly motivated public extension services is unable to cope with the current challenges of agriculture (Davis, Citation2008; Van Mele et al., Citation2010). Innovative learning tools, such as farmer training videos (FTVs) share information with large audiences and support agricultural extension services (Van Mele et al., Citation2010; Zoundji et al., Citation2020).

From August to December 2015, DVDs titled ‘Improving vegetable production’ were mass distributed to give farmers access to information about agroecology. Our previous study showed that these ‘Improving vegetable production’ videos increased farmers’ knowledge and improved their perceptions of sustainable agriculture in Benin (Zoundji et al., Citation2018a). In Uganda, rice farmers adapted the technologies and practices that they saw in the FTVs to generate new knowledge and technologies (Karubanga et al., Citation2017). The use of FTVs increased farmers’ knowledge and lead to the higher adoption of agricultural technologies in Mali (Sousa et al., Citation2019; Zoundji et al., Citation2018b).

Seven years after distributing the videos, we wanted to do a follow-up study to learn what further changes farmers were making in their work and why. Were farmers continuing to change, to adopt information from the videos? Were they creatively making use of new market opportunities and social opportunities for agroecological and organic agriculture?

Theoretical framework

The decision to adopt agricultural technology is complex and dynamic, as farmers are exposed to changing social, economic, political and ecological conditions (Hayden et al., Citation2021). Farmers’ capabilities, social networks, and decision-making all contribute to successful adoption (Orjuela-Garzon et al., Citation2021; Zoundji et al., Citation2020). Researchers often use decision-making theories, which analyze how people behave under risk and uncertainty, to highlight the main role of extrinsic factors (e.g. the technology and the external environment) and intrinsic factors (people’s knowledge, attitudes and perceptions) of innovation adoption (Meijer et al., Citation2015; Mercer, Citation2004; Schoonhoven & Runhaar, Citation2018; Zossou et al., Citation2020). However, implementing a fundamental change in farming techniques is usually triggered by positive tipping points, which can lead to transformative change (Pascual et al., Citation2022). These tipping points are generally linked to the spreading of norms, behaviours, opinions, and actions through social networks (Pascual et al., Citation2022; Stadelmann-Steffen et al., Citation2021). Yang & Shumway (Citation2020) accessing technology adoption through learning by doing, which is referred to as ‘own experience’. The ‘own experience’ model assumes that farmers’ own experiences have a greater impact than ideas communicated by others. However, even when farmers know about new technologies and want to adopt them, the resources required for adoption may be lacking (Fu & Akter, Citation2016). Runhaar et al. (Citation2016) identified four other conditions that influence changes in farmers’ practices: (i) farmers should be motivated to adopt new practices; (ii) the practices should respond to a particular demand of farmers; (iii) farmers should be able to implement new practices and, (iv) that new farming practices should be legitimized. Our paper uses this framework, which prioritizes motivation and demand as the primary reasons for adopting new technology, while ability and legitimacy (technology production has been respectful of stakeholders) are seen as enabling or facilitating factors.

Materials and methods

A Digital Video Disc (DVD) titled ‘Improving vegetable production’ compiled nine farmer-to-farmer training videos on agroecological vegetable cultivation. The DVD had a language menu, allowing the viewer to watch the videos in French, English or in three West African local languages (Fon, Yoruba and Bambara). The videos showed all the different steps of vegetable production (nursery management, field operations, harvesting and post-harvest). In each video, farmers appear on camera to explain and show the techniques. A short description of the videos is presented in .

Table 1. Short description of farmer training videos on the ‘Improving vegetable production’.

From August to December 2015, agro-input dealers, vegetable sellers, entertainment DVD vendors, and motorcycle-taxi drivers in the southern Benin municipalities of Sèmé-Podji, Cotonou, Abomey-Calavi and Ouidah received copies of the DVD. These four municipalities are the primary vegetable-growing areas in the country where soilborne diseases, thrips, nematodes, leaf miners and aphids are significant pests (Avadi et al., Citation2020; Perez et al., Citation2017). The vendors were invited to sell a DVD for at least $1.00, and asked to register the name, phone number, and address of the DVD buyers for follow-up by the lead author. The aim of selling the DVDs, was to limit distribution to people who were motivated to seek new information.

In October 2022, a snowball sampling technique (Vogt, Citation1999) was used to reach 180 vegetable farmers who watched the videos at least three times a year in the past five years: 45 respondents in each of the four municipalities where the DVDs had been distributed seven year previously (2015). These farmers were also selected based on their willingness to participate in the study and having spent at least five last years in vegetable production. The aim of the research with these 180 farmers was to understand why they adopted agroecological vegetable production, and how these decisions impacted their families’ livelihoods.

In each municipality, we started by collecting qualitative data through focus group discussions (FGD) using a general interview guide and thematic questions with selected farmers in order to: (i) understand the social conditions that contribute to changes in farming practices; and (ii) identify relevant socio-economic and ecological indicators at household level according to DFID’s (1999) five Sustainable Livelihood (SL) capitals (natural, human, social, physical and financial). This SL framework has been widely used as an important tool to assess poverty in the rural area (D’Annolfo et al., Citation2020; Garibaldi et al., Citation2016; Zossou et al., Citation2012; Zoundji et al., Citation2022). Based on information obtained from FGD, we formulated a semi-structured questionnaire on respondents’ access to vegetable growing information, their knowledge, practices, motivations, and the effects of sustainable vegetable growing on respondents’ livelihoods. The questionnaire allowed for broader discussions through a one-on-one interview with the 180 selected farmers.

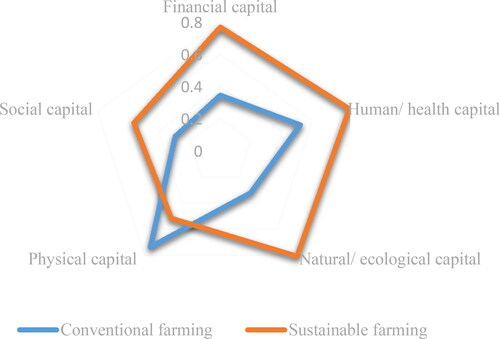

The Sustainable Livelihoods (SL) framework was used to estimate each vegetable farmer’s capital stocks in 2015, the year distribution of the DVD and in 2021, the study year. A recall method exercise (Faulkner & Raybould, Citation1995) was used, and famers were asked to try to remember their past capital assets to estimate capital stocks in the baseline year. The farmers rated the capital stocks identified for the baseline year and the impact year on a 0–1 scale. A spider web diagram was drawn to visualize the five capitals with value 0 (no stock) at the center of the diagram and the value 1 at the other extreme of the axes, indicating a full asset stock. The scores of conventional and sustainable farming (agroecological, or organic practices) in each capital were compared using the t-test in order to determine significant differences between the two farming production modes. However, this study relied more on a qualitative approach and the collected qualitative data was analyzed using a formal method in ethnography, which was based on thematic trends in farmers’ statements (Sanjek, Citation2000). We also used quotes to bring vegetable farmers’ views into the analysis.

Results and discussion

Vegetable farmers’ sociodemographic characteristics

Of the 180 vegetable farmers involved in this study, most (54%) were between 41 and 50 years old, with an average of 44.5 years (). About 31% were young (25–40 years) and 15% were older farmers (50–60 years). Two-thirds were male (64%). Both genders are involved in vegetable growing, but there are more men in the agricultural sector than women in Benin (INSAE, Citation2016). However, two-thirds of farmers who practiced sustainable vegetable farming (agroecological and organic) were women, because they have limited access to cash and to agrochemicals and relied mainly on the use of local inputs (Sodjinou et al., Citation2015; Vodouhe et al., Citation2022). More than half (59%) of the vegetable farmers had attended school, including some who had gone to university, but 41% had no formal education (). The many farmers with little or no formal education may not speak French or English, highlighting the importance of making farmer training videos in the farmers’ own language (Bede et al., Citation2021). Just over half (52%) of respondents in the study area had 11–20 years of experience in vegetable growing.

Table 2. Vegetable farmers’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Farmers in the study area use three major channels to sell their products. About 58% of respondents used the individual sale method. Most of them were conventional vegetable farmers (51%). Ecological vegetable farmers (23%) mainly used the joint sale method to sell their products to consumers who know the difference and appreciate the value. However, all organic vegetable farmers sold their products under contract with the Association pour le Maintien de l’Agriculture Paysanne (AMAP) network which delivers baskets of organic products to consumers, deliver orders to supermarkets, restaurants etc. In addition, AMAP has also a few organic vegetable outlets set up in the major cities such as Cotonou (in front of the French school Montaigne), Porto Novo (Notre Dame Cathedral) etc. where sustainable vegetables are in high demand. Consumers’ propensity to purchase organic products tended to increase with their social status, education land income levels (Monier-Dilhan & Bergè, Citation2016; Wier et al., Citation2008).

Sources of farmers’ information on sustainable agriculture practices

Vegetable farmers’ sources of agroecological and organic information were assessed. Farmer training video is the single most important source of agroecological information used by 94% of respondents. Only 6% mentioned peers and others farmers as sources of agroecological farming information. About 60% of respondents received organic farming information (no synthetic pesticides, fertilizer use and farms are decertified) from vegetable sellers and 40% received such information from other farmers (peers, friends, local associations etc.). The public extension service is not involved in the sustainable agricultural information dissemination since most extensionists have been trained in conventional agriculture with limited knowledge of agroecological practices (Anderson et al., Citation2021). This is in line with Zoundji et al. (Citation2016) who found that private sector actors or informal networking could become ‘new extensionists’ and share useful agricultural information to farmers, mainly in the context of limited number of extension workers.

Vegetable production modes and main drivers of knowledge development

Before distributing the farmer training videos (FTVs) almost all (95.5%) of the vegetable farmers sampled were practicing conventional vegetable cultivation (). Only 4.5% of them were engaged in agroecological farming. Seven years after distributing the FTVs, the number of farmers engaged in conventional vegetable farming had decreased by nearly half, from 95.5% to 51% (), while 44.5% of the farmers had started growing vegetable sustainably (agroecology and organic farming). At the same time, the number of agroecological vegetable farmers have increased from 4.5% to 30% and 19% of respondents famers have started cultivating organic vegetables. In addition, respondent farmers have a clear understanding about the three production systems (). Even the farmers who continue to use the conventional system are able to explain the importance or relevance of each system.

Table 3. Vegetable farming systems.

Table 4. Farmers’ understanding of vegetable production systems.

Farmer training videos (FTVs) in local languages have contributed to farmers’ experiential learning or learning by doing and improved vegetable farmers’ skills and knowledge, motivating them to make changes in their practices towards agroecological farming. For example, a vegetable farmer at Malanville, highlighted how much he had gained from FTV: - With FTVs, we (my wife, children and me) have seen a visual, convincing demonstration and practical explanation on agroecological vegetable growing from other farmers in our own language. It was nice and useful videos, which have stimulated our learning and facilitated the transition towards agroecological or organic farming-.

Organic agriculture is defined by a certification (HLPE, Citation2019), which was beyond the scope of these videos However, some farmers who adopted agroecological practices shown on the videos later went on to grow certified organic vegetables, in part because of advice that they received from vegetable sellers and their social network about the higher prices of certified organic produce. The agroecological information in the videos was a gateway for some farmers to become certified organic producers. Respondents highlighted the key role of vegetable sellers and farmers’ social network in promoting certified organic production. As farmers’ knowledge development about innovation is the first and important phase of the decision-making process for its adoption (Rogers, Citation1995), based on the organic products demanded on the market, vegetable sellers explained the benefit of this production mode to farmers and facilitated their learning opportunities with the Association pour le Maintien de l’Agriculture Paysanne (AMAP) network in Benin. Thus, three out of five persons of organic production were linked to AMAP by vegetable sellers while the rest were oriented by others farmers (friends). Indeed, AMAP organized the ‘Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS)’ certification with farmers.

Reasons motivating sustainable vegetable growing

Farmers cited five main motivations for adopting sustainable vegetable growing: 32% mentioned lower production costs; 21% cited market demand for sustainable products; 17% mentioned product pricing; 16% indicated the products’ quality and 14% referred to health protection.

The motives for converting to agroecological and organic production are related to financial, market demand and health reasons, in line with other studies in sub-Saharan Africa (Glin et al., Citation2012; Sodjinou et al., Citation2015; Zoundji et al., Citation2018a). In addition, agroecological farmers noticed an average a 52% reduction in costs, while organic farmers saved about 74%. The following testimony of a vegetable farmer in Grand Popo explained farmers’ reasons to change from conventional vegetable growing.

- In the conventional system, customers often complained about the storage problems of my products, which rot only two days after harvesting. However, when I watched the videos and started to apply carefully the agroecological practices, my products such as tomato, carrot, and cucumber can be kept up to five days without any problem. Thus, I do not rush to sell my products. I take my time to negotiate the price with the customers. In addition, my health problems, which are often linked to the application of chemical pesticides, have stopped. I can tell you that this self-learning with the videos has encouraged me to adopt agroecological practices in the vegetable growing and has really changed my life-.

Another woman vegetable farmer at Seme-Podji, explained how farmers define the lower production cost:

- In the conventional system, I often used to produce tomatoes on a 500 square meter plot, applying 3 kg to 5 kg of nematicide Diafuran 5G, 1.5 to 2.5 liters of insecticide K-Optimal, 2 kg to 3 kg of fungicide TOPSIN M, and about 50 kg of fertilizer NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium). However, since 2015 I have started applying agroecological knowledge acquired from videos and gradually reducing the agrochemicals. For example, in this vegetable production season, for a 500 square meter plot, I used 1 kg of Diafuran 5G, no K-Optimal, 1kg of TOPSIN M, 6 kg of NPK and my yield of tomato is still the same as before videos, but now they keep longer than before videos-.

Demand for sustainable vegetable growing

The videos motivated many farmers to adopt agroecological practices, for example, to save money and to improve their health. The market demand for organic vegetables stimulated some of the agroecological farmers to take the further step of producing certified organic vegetables, to meet the increase in consumer demand and to earn higher prices (Loconto et al., Citation2016). The main organic vegetables produced in the study areas are tomatoes, carrots, lettuce, cabbage, cucumber, pepper, onion, amaranth, basil, African eggplant, great basil, leeks etc. According to organic vegetable farmers, only about 13% of organic products demand is satisfied. Organic and ecological farmers consistently express their motivation in terms of higher prices paid for sustainably produced vegetables. The price of one basket of organic vegetable was 28.4% higher than conventional, while agroecological vegetables fetched about 15% more than conventional vegetables. Economic benefit is a key motivation for farmers to adopt organic agriculture (Glin et al., Citation2012; Thakur et al., Citation2022; Zoundji et al., Citation2018b).

In spite of these high prices, few young farmers (25–40 years) studied are engaged in sustainable farming, because it requires more physical effort and faces constraints such as difficulties in pest management, accessing organic inputs and requirements for more highly skilled labor. Many authors such as Avadi et al. (Citation2020), Assogba et al. (Citation2022) have also highlighted these constraints and suggested appropriate measures to overcome them in sustainable vegetable production in Benin. Market demand alone is not sufficient for agricultural technology adoption. Pattanayak et al. (Citation2003) and Meijer et al. (Citation2015) found other factors such as resource endowments, preferences, biophysical factors, risk and uncertainty, which also explain technology adoption. Policy and institutional challenges also limit the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices in sub-Saharan Africa because many governments continue to subsidize chemical pesticides and fertilizers (D’Annolfo et al., Citation2020; Jayne & Rashid, Citation2013; Mockshell & Villarino, Citation2019).

Farmers association as a key for the sustainable vegetable promotion

On their own initiative, some the agroecological vegetable farmers who watched the videos organized themselves into a group called the Association des Maraîchers Agroécologiques (AMA, i.e. the Association of Agroecological Farmers). This farmers’ organization was created in the study areas of Abomey-Calavi and Cotonou on 9 March 2019 and 11 July 2020 respectively to facilitate farmers’ learning in agroecology and stimulate their interest towards sustainable vegetable cultivation. AMA’s creation was stimulated by the Association pour le Maintien de l’Agriculture Paysanne (AMAP) network which delivers baskets of organic products to consumers. According to respondents, AMA will be established soon in the study areas of Seme-Podji and Ouidah. However, members of AMA work as volunteers in the main vegetable production areas in the south of Benin in order to promote agroecological and organic practices through knowledge development through FTV shows in the communities, farmer to-farmer exchange sessions, agroecological vegetable farming visits sessions, compost techniques demonstration etc. AMA focused also on the trust building with vegetable sellers. Without any certificate as a proof of ecological products, farmers built trust with vegetable sellers or customers to sell their products with an ecological label. About 87% of agroecological vegetable farmers noticed that the customers trust them because they believed in the production using compost, manure, bio pesticides and with none or limited chemical inputs. This is justified by customers’ experiences with storing and preserving fresh vegetables for a longer time than conventional grown produce. Without any certification, trust is playing a capital role in the customers’ decision-making towards buying sustainable produce since customers or vegetable buyers have not access to complete reliable information on agricultural products or food production (Bernard et al., Citation2021).

Sustainable vegetable growing on farmer livelihoods

shows the entities of the five capitals on which the FTVs have a direct impact on the farmers’ livelihoods. Thus, sustainable vegetable farmers (agroecological and organic farming) have higher score than conventional vegetable farmers in four of the five capitals such as financial, human, natural and social (). The difference observed in these capitals was significant with the use of test () since agroecological practices based on soil fertility, pest and disease management have contributed to the improvement of these capitals for the sustainable vegetable farmers. The conventional vegetable farmers have only a higher score in terms of physical capital because they used less labor-intensive techniques than sustainable vegetable farmers. This is confirmed by many authors (Colting-Pulumbarit et al., Citation2018; D’Annolfo et al., Citation2020; Debie et al., Citation2022), who highlighted that farmers’ adoption of sustainable farming practice has positive effects on their social, natural, financial and human capitals. Thus, agroecological and organic farming offer more sustainable livelihoods than conventional farming. Sustainable vegetable farming can therefore be promoted as a strategy to increase farmers’ livelihood.

Table 5. Main components of the five capitals for sustainable livelihoods with comparison of conventional and sustainable farming.

Conclusion

Before watching the agroecological videos, farmers were dependent on agrochemicals for conventional vegetable growing. The farmers had little knowledge of sustainable vegetable farming since the public extension service was not promoting sustainable agriculture. The FTVs were the most important source of agroecological information used by farmers (94%). These learning tools helped to improve farmers’ skills and knowledge, motivating them to move towards agroecology farming. The videos also stimulated vegetable farmers’ creativity to later engage in organic farming. As changes in farming techniques through the adoption of innovations or new practices are usually triggered by tipping points (Pascual et al., Citation2022), farmers who practiced sustainable vegetable farming were motivated by lower production costs, higher market demand, selling at a premium price, product quality and health consideration. Farmers’ organizations were also important for facilitating learning, and building trust for developing sustainable vegetable farming. In the specific context where farmers’ access to reliable information is limited, scaling up sustainable agricultural farming through FTV can be considered as a strategy to increase farmers’ knowledge and adaptive capacity towards rural livelihood improvement.

This study follows up on our earlier work, which showed that farmers learned about ecological farming and adopted it as a result of watching the FTVs. Seven years after acquiring the videos, farmers still recall the information, have learned more and expanded their livelihood capitals. Many of them, especially women, have improved their incomes by producing organic and ecological vegetables. The lessons learned from watching information videos can have a positive impact on the lives of farmers over many years. This study supports the proposal that FTVs can play a significant role in enabling farmers to implement innovative practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gérard C. Zoundji

Gérard C. Zoundji is an associate professor at Université Nationale d’Agriculture, Benin. He is an agricultural social scientist with a large experience in agricultural innovation, sustainable agriculture, and climate change adaptation.

Florent Okry is a full professor at Université Nationale d’Agriculture, Benin. He is an agricultural scientist with a large experience in rural learning and innovation systems.

Paul Van Mele

Paul Van Mele is an agricultural scientist and managed agricultural R&D projects dealing with sustainable agriculture. Paul has spearheaded farmer-to-farmer training video, coordinated research on video-mediated learning and taken it to scale.

Jeffery W. Bentley

Jeffery W. Bentley is an agricultural anthropologist with a lifelong interest in local knowledge, farmer experiments and videos in agricultural extension.

Charles Kwame Sackey

Charles Kwame Sackey is a lecturer at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. Charles has a large experience in agricultural innovation, and market-oriented agriculture programme development.

References

- Anderson, C. R., Bruil, J., Chappell, M. J., Kiss, C., & Pimbert, M. P. (2021). Agroecology now! Transformations towards more just and sustainable food systems. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Assogba, C. G., Vodouhê, G. T., Adje, B., Dassou, A., Tovignan, S. D., Kindomihou, V., & Vodouhê, S. D. (2022). Agroecological transition in vegetable farming systems in southern Benin. Lessons from a diagnostic analysis. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 123(2), 1–11.

- Avadi, A., Hodomihou, R., & Feder, F. (2020). Maraîchage raisonné versus conventionnel au sud-Bénin: Comparaison des impacts environnementaux, nutritionnels et socio-économiques. Report, INRA Et CIRAD, Métaprogramme GloFoodS, France.

- Bede, L., Okry, F., & Vodouhe, S. D. (2021). Videomediated rural learning: Effects of images and languages on farmers’ learning in Benin Republic. Development in Practice, 31(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1788508

- Bernard, T., Dänzer, P. N., Frölich, M., Landmann, A., Viceisza, A., & Wouterse, F. (2021). Building trust in rural producer organizations: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 50(3), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1017/age.2021

- Colting-Pulumbarit, C., Lasco, R. D., Rebancos, C. M., & Coladilla, J. O, University of the Philippines Los Banos. (2018). Sustainable livelihoods-based assessment of adaptive capacity to climate change: The case of organic and conventional vegetable farmers In La Trinidad, Benguet, Philippines. Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 21(2), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.47125/jesam/2018_2/08

- D’Annolfo, R., Gemmill-Herren, B., Amudavi, D., Shiraku, H. W., Piva, M., & Garibaldi, L. A. (2020). The effects of agroecological farming systems on smallholder livelihoods: A case study on push–pull system from Western Kenya. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 19(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2020.1822639

- Davis, K. E. (2008). Extension in Sub-Saharan Africa: Overview and assessment of past and current models, and future prospects. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 15, 15–28.

- Debie, E., Yayeh, T., & Anteneh, M. (2022). The role of sustainable soil management practices in improving smallholder farmers’ livelihoods in the Gosho watershed, Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 8(1), 2097608. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2022.2097608

- DFID. (1999). Sustainable guidance sheets: Framework. Department for International Development, Report.

- Duru, M., Therond, O., & Fares, M. (2015). Designing agroecological transitions: A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 35(4), 1237–1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0318-x

- El-Sheikh, E. S. A., Ramadan, M. M., El-Sobki, A. E., Shalaby, A. A., McCoy, M. R., Hamed, I. A., Ashour, M. B., & Hammock, B. D. (2022). Pesticide residues in vegetables and fruits from farmer markets and associated dietary risks. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(22), 8072. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27228072

- FAO. (2018). International symposium on agroecology: Scaling up agroecology to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs), April 2018.

- Faulkner, B., & Raybould, M. (1995). Monitoring visitor expenditure associated with attendance at sporting events: An experimental assessment of the diary and recall methods. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 3, 73–81.

- Fu, X., & Akter, S. (2016). The impact of mobile phone technology on agricultural extension services delivery: Evidence from India. The Journal of Development Studies, 52(11), 1561–1576. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1146700

- Garibaldi, L. A., Dondo, M., Hipólito, J., Azzu, N., Viana, B. F., & Kasina, M. (2016). A quantitative approach to the socio-economic valuation of pollinator-friendly practices: A protocol for its use. FAO.

- Glin, L. C., Mol, A. P. J., Oosterveer, P., & Vodouhê, S. D. (2012). Governing the transnational organic cotton network from Benin. Global Networks, 12(3), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00340.x

- Hayden, M. T., Mattimoe, R., & Jack, L. (2021). Sensemaking and the influencing factors on farmer decision-making. Journal of Rural Studies, 84, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.03.007

- HLPE. (2019). Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome.

- INSAE. (2016). Effectifs de la population des villages et quartiers de ville du Bénin (RGPH-4, 2013). Institut National De la Statistique Et De L’Analyse Economique (INSAE), République du Bénin.

- Jayne, T. S., & Rashid, S. (2013). Input Subsidy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: A synthesis of recent evidence. Agricultural Economics, 44(6), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12073

- Karubanga, G., Kibwika, P., Okry, F., & Sseguya, H. (2017). How farmer videos trigger social learning to enhance innovation among smallholder rice farmers in Uganda. Cogent Food & Agriculture (2017), 3(1), 1368105. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2017.1368105

- Loconto, A. M., Poisot, A. S., & Santacoloma, P. (2016). Innovative markets for sustainable agriculture: How innovations in market institutions encourage sustainable agriculture in developing countries. Report, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and Institut National De la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), Rome, Italy, 1–390.

- MAEP. (2017). Stratégie nationale de promotion des filières agricoles intégrant l’outil clusters agricoles. Document Final. Ministère De L’Agriculture De L’Elevage Et De la Pêche.

- Meijer, S., Catacutan, D., Ajayi, O. C., Sileshi, G. W., & Nieuwenhuis, M. (2015). The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 13(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2014.912493

- Mercer, D. (2004). Adoption of agroforestry innovations in the tropics: A review. Agroforestry Systems, 61-62(1-3), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AGFO.0000029007.85754.70

- Mockshell, J., & Villarino, M. E. (2019). Agroecological intensification: Potential and limitations to achieving food security and sustainability. In P. Ferranti (Ed.), Encyclopedia of food security and sustainability (vol. 3, pp. 64–70). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22211-7

- Monier-Dilhan, S., & Bergè, F. (2016). Consumers’ motivations driving organic demand: Between self-interest and sustainability. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 45(3), 522–538. https://doi.org/10.1017/age.2016.6

- Orjuela-Garzon, W., Quintero, S., Giraldo, D. P., Lotero, L., & Nieto-Londoño, C. A. (2021). Theoretical framework for analysing technology transfer processes using agent-based modelling: A case study on massive technology adoption (AMTEC) program on rice production. Sustainability, 13(20), 11143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011143

- Paparu, P., Acur, A., Kato, F., Acam, C., Nakibuule, J., Musoke, S., Nkalubo, S., & Mukankusi, C. (2017). Prevalence and incidence of four common bean root rots in Uganda. Experimental Agriculture, 54(6), 888–900. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479717000461

- Pascual, U., McElwee, P. D., Diamond, S. E., Ngo, H. T., Bai, X., Cheung, W. W. L., Lim, M., Steiner, N., Agard, J., Donatti, C. I., Duarte, C. M., Leemans, R., Managi, S., Pires, A. P. F., Reyes-García, V., Trisos, C., Scholes, R. J., & Pörtner, H.-O. (2022). Governing for transformative change across the biodiversity–climate–society nexus. BioScience, 72(7), 684–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac031

- Pattanayak, S. K., Mercer, D. E., Sills, E., & Yang, J.-C. (2003). Taking stock of agroforestry adoption studies. Agroforestry Systems, 57(3), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024809108210

- Perez, K., Froikin-Gordon, J. S., Abdourhamane, I. K., Levasseur, V., Alfari, A. A., Mensah, A., Bonsu, O., Habsatou, B., Assogba-Komlan, F., Mbaye, A. A., Noussourou, M., Otoidobiga, L. C., Ouédraogo, L., Kon, T., Rojas, M. R., Gamby, K. T., Shotkoski, F., Gilbertson, R. L., & Jahn, M. M. (2017). Connecting smallholder tomato producers to improved seed in West Africa. Agriculture & Food Security, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0118-4

- Pretty, J., & Bharucha, Z. P. (2014). Sustainable intensification in agricultural systems. Annals of Botany, 114(8), 1571–1596. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcu205

- Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed). Free Press.

- Runhaar, H. A. C., Melman Th, C. P., Boonstra, F. G., Erisman, J. W., Horlings, L. G., de Snoo, G. R., Termeer, C. J. A. M., Wassen, M. J., Westerink, J., & Arts, B. J. M. (2016). Promoting nature conservation by Dutch farmers: A governance perspective. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 15(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2016.1232015

- Sanjek, R. (2000). Keeping ethnography alive in an urbanizing world. Human Organization, 59(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.59.3.5473111j42374034

- Schoonhoven, Y., & Runhaar, H. (2018). Conditions for the adoption of agro-ecological farming practices: A holistic framework illustrated with the case of almond farming in Andalusia. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 16(6), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2018.1537664

- Singbo, A. G., Lansink, A. O., & Emvalomatis, G. (2015). Estimating shadow prices and efficiency analysis of productive inputs and pesticide use of vegetable production. European Journal of Operational Research, 245(1), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.02.042

- Sodjinou, E., Glin, L., Nicolay, G., Tovignan, S., & Hinvi, J. (2015). Socioeconomic determinants of organic cotton adoption in Benin, West Africa. Agricultural and Food Economics, 3(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-015-0030-9

- Sousa, F., Nicolay, G., & Home, R. (2019). Video on Mobile Phones as an Effective Way to Promote Sustainable Practices by Facilitating Innovation Uptake in Mali. International Journal of Sustainable Development Research, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijsdr.20190501.11

- Stadelmann-Steffen, I., Eder, C., Harring, N., Spilker, G., & Katsanidou, A. (2021). A framework for social tipping in climate change mitigation: What we can learn about social tipping dynamics from the chlorofluorocarbons phase-out. Energy Research & Social Science, 82 (2021), 1–9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102307

- Thakur, N., Nigam, M., Mann, N. A., Gupta, S., Hussain, C. M., Shukla, S. K., Shah, A. A., Casini, R., Elansary, H. O., & Khan, S. A. (2023). Host-mediated gene engineering and microbiome-based technology optimization for sustainable agriculture and environment. Functional & Integrative Genomics, 23(1) 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-023-00982-9

- Thakur, N., Nigam, M., Tewary, R., Rajvanshi, K., Kumar, M., Shukla, S. K., Mahmoud, G. A. E., Shivendra., & Gupta, S. (2022). Drivers for the behavioural receptiveness and non-receptiveness of farmers towards organic cultivation system. Journal of King Saud University - Science, 34(5), 102107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102107

- Van den Berg, L., Roep, D., Hebinck, P., & Teixeira, H. M. (2018). Reassembling nature and culture: Resourceful farming in Araponga. Brazil. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 314–322.

- Van Mele, P., Wanvoeke, J., & Zossou, E. (2010). Enhancing rural learning, linkages and institutions: The rice videos in Africa. Development in Practice, 20(3), 414–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614521003710021

- Vodouhe, G., Zossou, E., Tossou, R. C., & Vodouhe, S. D. (2022). Déterminants de l’adoption des systèmes de production des légumes biologiques au Sud-Bénin. Annales De L’Université De Parakou - Série Sciences Naturelles Et Agronomie, 12(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.56109/aup-sna.v12i1.46

- Vogt, W. P. (1999). Dictionary of statistics and methodology: A nontechnical guide for the social sciences. Sage Publications.

- Wezel, A., Casagrande, M., Celette, F., Vian, J. F., Ferrer, A., & Peigné, J. (2014). Agroecological practices for sustainable agriculture. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 34(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0180-7

- Wier, M., O’Doherty, K., Andersen, L., Millock, K., & Rosenkvist, L. (2008). The character of demand in mature organic food markets: Great Britain and Denmark compared. Food Policy,.33(5), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.01.002

- Williamson, S., Ball, A., & Pretty, J. (2008). Trends in pesticide use and drivers for safer pest management in four African countries. Crop Protection, 27(10), 1327–1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2008.04.006

- World Bank. (2019). Benin digital rural transformation project. Project Document, World Bank.

- Yang, S., & Shumway, C. R. (2020). Knowledge accumulation in US agriculture: Research and learning by doing. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 54(2-3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-020-00586-6

- Zossou, E., Arouna, A., Diagne, A., & Agboh-Noameshie, R. A. (2020). Learning agriculture in rural areas: The drivers of knowledge acquisition and farming practices by rice farmers in West Africa. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 26(3), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2019.1702066

- Zossou, E., Van Mele, P., Wanvoeke, JAnd., & Lebailly, P. (2012). Participatory impact assessment of rice parboiling videos with women in Benin. Experimental Agriculture, 48(3), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479712000117

- Zoundji, C. G., Okry, F., Vodouhê, D. S., & Bentley, J. W. (2018a). Towards sustainable vegetable growing with farmer learning videos in Benin. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 16(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2018.1428393

- Zoundji, C. G., Okry, F., Vodouhê, D. S., Bentley, J. W., & Witteveen, L. (2020). Commercial channels vs free distribution and screening of learning videos: A case study from benin and mali. Experiemental Agriculture, 56(4), 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479720000149

- Zoundji, C. G., Zossou, E., Vodouhè, F., Sackey, K. C., & Bognonkpe, G. (2022). Participatory evaluation of development projects contribution to poverty reduction in northern benin. European Journal of Sustainable Development, 11(3), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2022.v11n3p340

- Zoundji, G. C., Vodouhe, S. D., Okry, F., Bentley, J. W., & Tossou, R. C. (2018b). Beyond striga management: Learning videos enhanced farmers’ knowledge on climate-smart agriculture in mali. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 7(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.5539/sar.v7n1p80

- Zoundji, G., Okry, F., Vodouhe, S. D., & Bentley, J. W. (2016). The distribution of farmer learning videos: Lessons from non-conventional dissemination networks in Benin. Cogent Food & Agriculture (2016), 2(1), 1277838. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2016.1277838