?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the performance level of agribusiness actors by applying the basic price of Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency and to determine the role and relationship between the subsystems involved. This research used qualitative and quantitative descriptive approaches. Data analysis techniques used interpretive structural modeling (ISM) to determine the key factors in the agribusiness institutional system and used importance–performance analysis (IPA) to measure each institution’s performance level. The performance of Arabica coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency revealed that the actors who have high interests and low performance included farmers, agrochemical industries, companies, collecting traders, agricultural extension workers, and the agriculture office. By contrast, the actors with high interest and good performance include the Department of Agriculture, companies, coffee shops, and farmer groups. Moreover, the actors with low stakes and low performance included farmer groups, MSMEs, and coffee shops. At the same time, the actors with low interest and good performance included the agromechanical industry, farmers, and cooperatives. The findings were used to map the actors with the most important role in the agribusiness system and the linkages between Arabica coffee subsystems in the North Toraja Regency.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Coffee is one of the agricultural products grown in over 80 tropical countries. It provides an income to more than 25 million families, making it one of the most traded commodities on the global market (DaMatta et al., Citation2019; Hunt et al., Citation2020). The genus Coffea has 124 species, which are widespread and adapted to tropical and subtropical areas, particularly in Africa, the center of endemism (Davis et al., Citation2019). In other words, Indonesia also has the potential as a global coffee market supplier through coffee exports in coffee beans, and only approximately 3.46% (13,861 tons) of coffee is exported as processed coffee. Exports of processed coffee products in 2018 reached more than USD 580 million, about a 19.01% increase from the previous year (Ministry of Industry, Citation2018).

Coffee provides a livelihood to millions of smallholder farmers but comes with serious challenges as incomes are often meager, and the climate crisis threatens most coffee-growing areas. Specialty coffee markets reward quality, which can increase farm-gate prices and may enhance shaded and diversified coffee-farming systems (Jacobi et al., Citation2024). Relatedly, alternative forms of organizing coffee value chains have emerged, such as direct-trade platforms (Guimarães et al., Citation2020), or the ‘relationship coffee model’ (Hernandez-Aguilera et al., Citation2018). These developments seem urgent, as current globalized coffee value chains are highly unequal and dominated by a small number of actors (Grabs & Ponte, Citation2019).

Agribusiness has a major role in transforming the agricultural sector (Ume et al., Citation2020). The agricultural development has been implemented by employing an agribusiness system. In this concept, it is essential to have strong and appropriate integration between the upstream and downstream sectors. In other words, all the sub-systems of agribusiness must be interrelated with each other. The sub-systems of agribusiness are: (i) agroinputs and agricultural equipment sub-system; (ii) on-farm sub-system; (iii) processing sub-system; (iv) marketing sub-system; and (v) supporting sub-system. The integration among the subsystems indicates the inclusiveness of agricultural development. The business model established should include the coffee farmers/farmers’ cooperative, coffee buyer/exporter, bank, government, research institution, and independent actors. Among the market actors, they should have mutualism partnerships to obtain economic incentives. This could ensure the sustainability of inclusive business in coffee development (Sedana & Astawa, Citation2019).

As the main actors in Arabica coffee farming, farmers have a crucial role in making decisions on implementing Arabica coffee farming activities. Farmers’ management and technical capabilities are quite limited (Sunanto et al., Citation2019). There are four main actors in the Toraja coffee value chain: coffee farmers, collecting traders who sell coffee to industries in the district, collecting traders who sell coffee to traders outside the district, and home coffee processing industries in the district (Salam et al., Citation2021). The supporting actors in the Arabica coffee value chain in North Toraja are the following: transportation services, providers of inputs or means of production, and consumers (Salam et al., Citation2021).

Agribusiness is an important sector of the global economy, and ESG (environmental, social, and governance) practices are gaining increasing importance in this sector (de Campos Filho & de Oliveira, Citation2024). Agribusiness is important in developing Arabica coffee commodities; agribusiness consists of four subsystems: production facilities, on-farm, processing, and marketing (Febryan et al., Citation2023). In the agribusiness system, every Arabica coffee agribusiness player involved in the upstream, farming, downstream, marketing, and supporting subsystems must have good quality achievements or work performances. Various studies on the performance of agribusiness actors have included the performance of farmers (Malta, Citation2011; Putri et al., Citation2018), the performance of farmer groups (Irawati & Yantu, Citation2015), the performance of agricultural extension workers (Syafii, Citation2017), the performance of supporting institutions (Yasmin et al., Citation2022), the institutional performance of production inputs (Sisfahyuni, Citation2008), and the performance of marketing institutions (Rospa, Citation2022). These studies were still limited to discussing the performance of agribusiness actors in the upstream, agricultural, downstream, marketing, and supporting subsystems, not as a whole as an agribusiness system in Arabica coffee commodities.

Performance is the behavior demonstrated by individuals in carrying out their work to achieve the organizational goals determined by work results and work quality. Performance is the goal achievement of an organization rather than of individuals, with the minimum resources consumed to reach the goal (Ghalem et al., Citation2016). The role of stakeholders is considered very relevant and important to improve the performance of both agribusiness actors and institutions involved to increase their role in agricultural development and farmer welfare (Arsyad & Kusuma, Citation2014). The collaborative efforts among government entities, research institutions, universities, and industry stakeholders in driving innovation within the agricultural sector is necessary (Silva & Palata, Citation2023).

According to Karyani et al. (Citation2018), Arabica coffee agribusiness institutions are reviewed from the perspective of farmers to see the institutional performance of the agribusiness subsystem as a whole, and according to Yasmin et al. (Citation2022), institutional performance is seen by separating the roles of each agribusiness subsystem. Based on the previous research, no research has revealed the institutional aspects related to implementing the basic prices of Arabica coffee commodities, so this is very interesting to be studied further. This study aimed to evaluate the performance level of agribusiness actors with the application of the basic price of Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency and to map the role and relationship between the subsystems involved.

Methods

Location and respondents

This research was conducted in North Toraja Regency as an Arabica coffee production center from October 2021 to March 2022. Qualitative and quantitative descriptive approaches were established in this study. The data used in this study were secondary data published by the Central Statistics Agency and other relevant government agencies, and primary data obtained directly from the respondents. The data collection techniques used were surveys, interviews, focuss group discussion (FGD) and documentation in the form of in-depth interview guidelines for the respondents. The respondents in this study included Arabica coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency in each of the upstream, farming, downstream, marketing, and supporting subsystems. The respondents were determined based on the actors involved in the Arabica coffee agribusiness system in North Toraja Regency. The number of respondents was 7–10 people for each agribusiness actor. This allowed each individual to have the opportunity to express their opinion and to obtain the views of varied group members sufficiently. presents the respondents for each Arabica coffee agribusiness actor in North Toraja Regency.

Table 1. The number of respondents involved in the present study.

Age

In this study, the respondents were sorted into 3 group, including less than 30 years old, 31–40 years old, and over 40 years old. This category followed the previous study that suggested the time before 30 years old is often a period within which individuals explore careers, whereas the time after 40 years old roughly marked the end of establishment years (Super, Citation1980). ADEA also uses 40 as the ‘cutoff age’. The previous research on age and job performance also used decade or half decade benchmarks (Ng & Feldman, Citation2008).

In this study, the respondents aged <30 years were 19 respondents with a percentage of 21%, aged 30–40 years were 45 respondents with a percentage of 47%, and 30 respondents with a percentage of 32% were >40 years old. Thus, it can be concluded that the majority of respondents in this study were aged 30–40 years.

Gender

Respondent characteristics based on gender consisted of men and women. The number of respondents with male gender was 67, with a percentage of 70%, and respondents with female gender were 29, with a percentage of 30%. Thus, it can be concluded that the majority of respondents in this study were men. The number of female respondent was less than men since most of them are housewives.

Education

Respondent characteristics based on education level consisted of high school, bachelor’s degree and master’s degree. The number of respondents with a high school education level was 30, with a percentage of 21%, while the number of respondents with a bachelor’s level education was 45, with a percentage of 47%, and the number of respondents with a master’s education level was 21 respondents with a percentage of 22%. Therefore, it can be said that most respondents have a bachelor’s degree level of education.

Data collection

A survey collects data or information on a large population using a relatively small sample. This method was also conducted by directly observing farmers’ conditions at the research site. The data collection used qualitative data collection techniques used in this research was Focus Group Discussion (FGD) to obtain information on participants’ desires, needs, points of view, beliefs and experiences about a topic, with direction from a facilitator or moderator. The purpose of this survey was to see the performance of coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency.

Research with survey methods must use questionnaires as a guide so that interviews are performed more regularly and purposefully. The questionnaire was a research instrument used to collect research data, containing questions and statements answered by the respondents. Each respondent was given a questionnaire in the form of a statement. Then, the respondent answered according to the circumstances or conditions of the respondent related to the performance indicators of coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency.

Data analysis

Interpretive structural modeling (ISM)

ISM, first proposed by J. Warfield in 1973, is a learning process with the help of tools that allow individuals or groups to develop maps of complex relationships among the various elements involved in complex situations. The basic idea is to use experienced experts and practical knowledge to decompose complex systems into subsystems (elements). In this study, ISM was used to analyze agribusiness actors and the relationship between several key actors or elements involved in the Arabica coffee agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency so that an analytical tool could interpret the complex relationships between various elements involved in complex situations. ISM is often used to provide a basic understanding of complex situations and to devise actions to solve problems (Gorvet & Liu, Citation2007). ISM is also useful for analyzing system elements and solving them in a graphical form from direct relationships between elements and levels of hierarchy. In this study, measurements were used on several elements, including the following:

The steps used to identify the relationship between subelements (Indrawanto, Citation2009) were the following:

Identification of system elements. The elements and subelements of a system were identified and listed. This activity can be conducted through research, brainstorming, or others.

Establishment of contextual relationships between elements. Contextual relationships between elements or subelements were established according to the purpose of the model.

Formation of a structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM).

This matrix results from respondents’ expert perceptions of contextual relationships between elements or subelements. The four kinds of sectors to present the type of relationship were the following: (Element i = Ei; Element j = Ej)

The symbol V expresses the contextual relationship established above between the Ei and Ej elements but not vice versa.

The symbol A expresses the contextual relationship between the Ej and Ei elements but not vice versa.

The symbol X expresses the contextual relationship established above in the reverse sector between the Ei and Ej elements.

The symbol O expresses the absence of the contextual relationship established above between the Ei and Ej elements.

Establishment of a reachability matrix (RM)

This matrix is a binary matrix converted from SSIM. The conversion rules from SSIM to RM were the following:

If the sector in SSIM is V, then the value of Eij = 1 and the value of Eji = 0.

If the sector in SSIM is A, then the value of Eij = 0 and the value of Eji = 1.

If the sector in SSIM is X, then the value of Eij = 1 and the value of Eji = 1.

If the sector in SSIM is O, then the value of Eij = 0 and the value of Eji = 0.

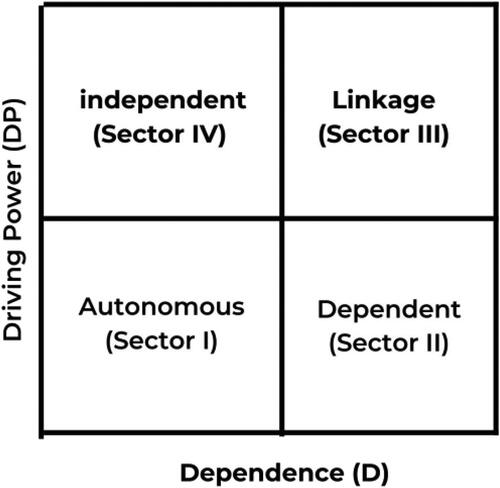

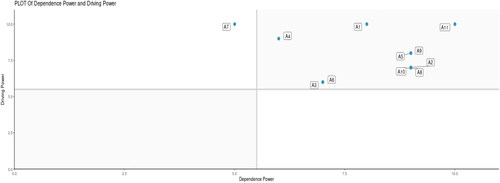

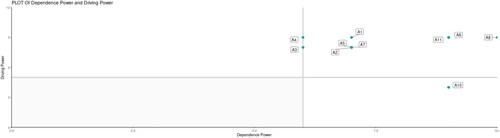

The initial RM matrix needs to be modified to show direct and indirect reachability, i.e. conditions where if Eij = 1 and Ejk = 1, then Eik = 1. Eij is the condition of the contextual relationship between the Ei and Ej elements. The modified RM matrix obtains the driver power value (DP) and dependency value (D). Based on the DP and D values, elements can be classified into the following four sectors ():

An autonomous sector has low DP and D values. The elements in this sector are generally not system related or have little correlation.

Dependent sectors are sectors with low DP and high D values. The system’s elements within this sector are not free and are highly dependent on other elements.

Linkage sector, i.e. the sector with high DP and D values. Elements that fall into this sector must be carefully studied because changes to these elements will have an impact on other elements, which will eventually have an impact on these elements as well.

Independent sectors with high DP and low D values. Elements that fall within this sector can be considered free elements. Any change in this element will affect other elements, so the elements in this sector must also be carefully examined.

Importance–performance analysis (IPA)

Importance Performance Analysis (IPA) was used to analyze agribusiness actors’ importance and performance/satisfaction levels. In addition, IPA was a tool used to analyze the importance and performance levels of a product/service. This analysis was used to answer the problem of the extent of the performance level of agribusiness actors on the services of existing institutions (Rangkuti, Citation2006). Measurements were calculated using a five-level Likert scale to measure importance: very important (5), important (4), moderately important (3), less important (2), and unimportant (1). The Likert scale was also used to measure performance levels: very good (5), good (4), good enough (3), less good (2), and not good (1).

The stages in the IPA method included:

Calculate all respondents’ average performance (Xi) and importance (Yi). The following formula calculates the average performance and importance of all respondents:

Calculate the average importance and performance assessment for each indicator:

(1)

(1)

where

Xi: Average weight of performance appraisal level i-th indicatorYi: Average weight of the importance level assessment of the i-th indicatori: number of respondents.

Calculate the conformity level (TKi) between performance and importance. TKi was calculated by the following formula:

(2)

(2)

where Xi is the performance score of the i-th indicator and Yi is the importance score of the i-th indicator.

Calculate the average performance and importance levels of the overall indicator:

(3)

(3)

where

Xi: average value of indicator performance

Yi: average value of the importance of indicators

K: number of indicators affecting respondents’ satisfaction.

Perpetrator performance indicators

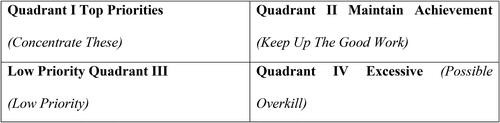

After obtaining the weights of performance and importance as well as the average performance and importance values, data was then plotted into a Cartesian diagram as follows ().

Figure 2. Cartesian diagram (Nasution, Citation2001).

Quadrant I (top Priority)

Quadrant I is an area that makes aspects with a high importance level but low performance. The aspects included in this quadrant must be improved in terms of performance and become a top priority to improve.

Quadrant II (maintain achievement)

Quadrant II shows indicators considered very important by farmers and have been implemented well by related institutions. The aspects included in this quadrant must be maintained and continued to be appropriately managed.

Quadrant III (Priority)

Quadrant III is an area that contains indicators with low importance and performance. The aspects included in this quadrant are considered less important by farmers, and their implementation was considered unfavorable. However, institutions still need to be vigilant and observe and control every aspect of this quadrant because the importance level of farmers can change as needs increase.

Quadrant IV (excessive)

This quadrant shows indicators considered less critical, but the institution has carried them out well, so it is considered excessive.

Results and discussion

Arabica coffee agribusiness in North Toraja regency

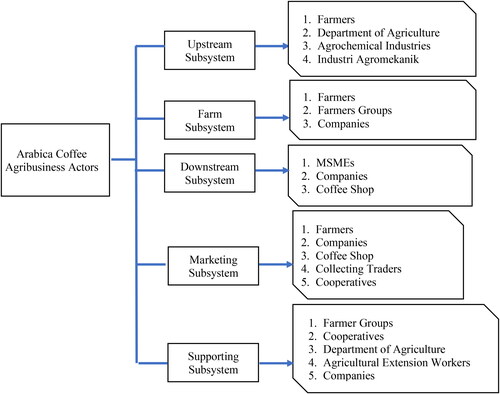

The Arabica coffee agribusiness system requires a harmonious linkage among the agricultural upstream, downstream, marketing, and supporting subsystems. One aspect that supports the success of an agribusiness system is agribusiness actors. Agribusiness actors are any individual or group of organizations active in agricultural businesses integrated into a system, that is, the agribusiness system. The coffee agribusiness system in Luwu Regency is formed from several agricultural subsystems: the upstream, and downstream, including post-harvest and marketing activities, and the supporting service subsystem (Hasnida et al., Citation2021). Based on the ISM analysis results, the following Arabica coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency are in each subsystem.

Upstream subsystem

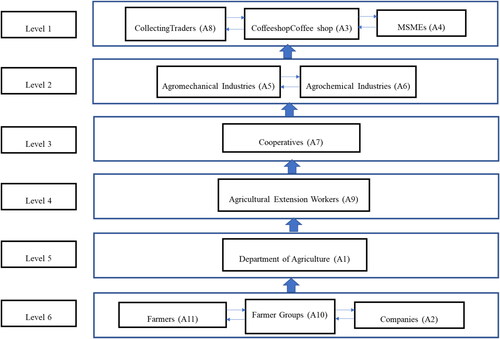

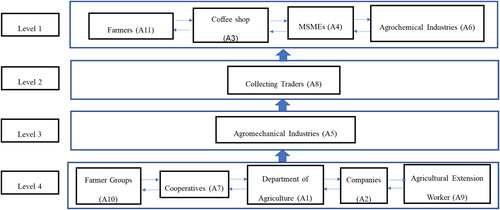

Based on the ISM analysis results, 11 sublements revealed agribusiness actors involved in the upstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in the North Toraja Regency. The following results can be drawn from a hierarchical diagram of the subelements of the upstream subsystem actors.

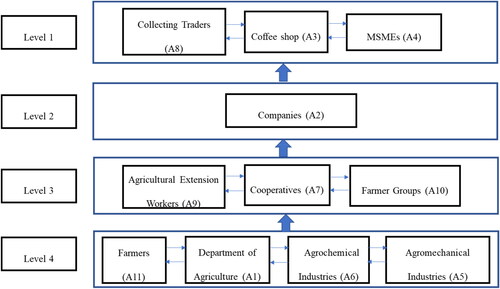

shows that farmers, the agriculture government, the agrochemical industry, and the agromechanical industry were at level 4 or the highest level, indicating that these agribusiness actors were very instrumental in the upstream Arabica coffee subsystem in North Toraja Regency. The strength and influence of the subelements of the agribusiness actors on the Arabica coffee agribusiness system are shown in . The upstream Arabica coffee subsystem includes a series of important steps in the coffee production process, starting from land preparation, planting, care, maintenance and harvesting of plants. At each stage of this activity requires support from various agribusiness actors, such as planting activities requiring support from the chemical and mechanical industry in the context of preparing seeds, pesticides and equipment that supports the Arabica coffee planting process. The agrochemical industry functions on a massive scale in a very intricate setting (Ley et al., Citation2021). Coffee plants are part of a large-scale farming system that requires agrochemicals to maintain its growth and protect it from pests and disease.

Figure 3. Diagram of the hierarchy of the subelements of the upstream agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

Figure 4. Driving power (DP) and dependence (D) matrix of the upstream agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

Moreover, support from the agricultural service is needed to provide education about proper and correct plant care procedures. This is supported by the opinion (Pan et al., Citation2018) that the impact of agricultural extension programs is providing various information and training in increasing agricultural productivity among poor farmers and, indirectly, increasing food security. And the most important thing is the role of farmers in cultivating Arabica coffee. Therefore, efforts are needed to increase the capacity and quality of coffee farmers through formal and informal education as well as institutional support for farmers in Indonesia, this is in accordance with the opinion of Yifru and Miheretu (Citation2022) improving farmers’ education status, strengthening local institutions, and empowering their members are vital for sustainable land management practices in the country.

As shown in , there were no subelements in sector I (autonomous), sector II (dependent), and sector IV (independent). All subelements were in sector III (linkage), namely, the agriculture office (A1), companies (A2), coffee shops (A3), MSMEs (A4), agromechanical industry (A5), agrochemical industry (A6), cooperatives (A7), collecting traders (A8), agricultural extension workers (A9), farmer groups (A10), and farmers (A11). Each subelement or agribusiness actor involved depends on each other, so any changes will affect the balance of the upstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency. Thus, all information should be linked and coordinated to industrialize due to the importance of the linkages between subsystems in the upstream sector (Wijaya et al., Citation2021).

Farm subsystem

Based on the ISM analysis of 11 subelements that showed agribusiness actors involved in the Arabica coffee farming agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency, the following is the result of a hierarchical diagram of the subelements of the agricultural subsystem actors ().

Figure 5. Diagram of the hierarchy of the subelements of the agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

The agribusiness subsystem actors of Arabica coffee farming are shown in .

Figure 6. Driving power (DP) and dependency (D) matrix of the elements of the agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

shows that there were no subelements in sector I (autonomous), sector II (dependent), and sector IV (independent). All subelements were in sector III (linkage), namely, the agriculture office (A1), companies (A2), coffee shops (A3), MSMEs (A4), agromechanical industry (A5), agrochemical industry (A6), cooperatives (A7), collecting traders (A8), agricultural extension workers (A9), farmer groups (A10), and farmers (A11). Each subelement or agribusiness actor involved depends on each other, so any changes will affect the balance of the Arabica coffee farming agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency. However, a limited degree of significance exists between the Arabica coffee agribusiness revenue variable (Y) and the agricultural subsystem variable (X2) (Njonge, Citation2023).

Downstream subsystem

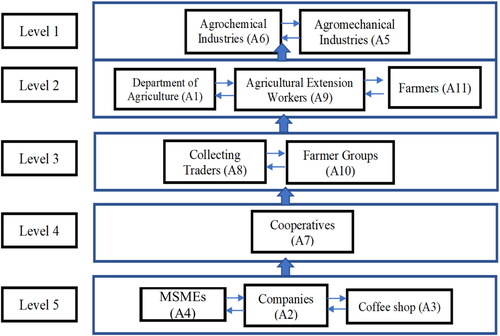

The ISM analysis of 11 subelements shows the agribusiness actors involved in the downstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency. The following is the result of a hierarchical diagram of the downstream subsystem actors.

As shown in , the subelements included at the highest level or level 5 that have a large role in the downstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in the North Toraja Regency are MSMEs, companies, and coffee shops. Abdel-Fattah and Al Hiary (Citation2023) demonstrated that the effects downstream might ultimately become the determining elements of success. The strength and influence of the subelements of the agribusiness actors on the Arabica coffee agribusiness system are shown in .

Figure 7. Diagram of the hierarchy of the subelements of the downstream agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

Figure 8. Driving power (DP) and dependence (D) matrix of the downstream agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

shows a matrix of driving power (DP) and dependence (D) comprising 11 subelements grouped into 4 sectors. shows no subelements in sectors I (autonomous) and II (dependent). There were 10 subelements in sector III (linkage), namely, the agriculture office (A1), companies (A2), coffee shops (A3), MSMEs (A4), agromechanical industry (A5), agrochemical industry (A6), collecting traders (A8), agricultural extension workers (A9), farmer groups (A10), and farmers (A11). The subelements in sector III are interrelated, so subelement changes will affect other subelements. In addition, one subelement was in sector IV (independent): cooperatives (A7). Cooperatives have no relationship with other subelements or agribusiness actors but still influence the downstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in the North Toraja Regency. Darma et al. (Citation2024) stated that the role of cooperatives in the marketing subsystem will be insignificant because they (cooperatives) only provide post-harvest processing assistance. However, sometimes, sales of ordinary products are made in minimal quantities.

Marketing subsystem

The ISM analysis of 11 subelements shows agribusiness actors involved in the Arabica coffee marketing agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency. The following is the results from a hierarchical diagram of the subelements of the marketing subsystem actors.

shows that in the hierarchical diagram, the subelements that occupy the highest level or level 4 were farmers, companies, coffee shops, collecting traders, and cooperatives. The subelements at the highest level have a large role in the agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee marketing in North Toraja Regency. It is in line with Santi et al. (Citation2022) that farmers and collecting traders play a role in marketing coffee which is sold in the form of dry coffee (green beans). The strength and influence of the subelements of the agribusiness actors on the Arabica coffee agribusiness system based on driving power (DP) and dependence (D) are shown in .

Figure 9. Diagram of the hierarchy of the subelements of the Arabica coffee marketing agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency.

Figure 10. Driving power (DP) and dependence (D) matrix of the subelements of the agribusiness marketing subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

shows no subelements in sector I (autonomous) and sector IV (independent). There was one subelement in sector II (dependent): farmer groups. Farmer groups were considered subelements with little power but a large influence on the Arabica coffee marketing agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency. Meanwhile, 10 other subelements were in sector III (linkage), namely, government services (A1), companies (A2), coffee shops (A3), MSMEs (A4), agromechanical industries (A5), agrochemical industries (A6), cooperatives (A7), collecting traders (A8), agricultural extension workers (A9), and farmers (A11). All subelements in sector III (linkage) were interrelated, so changes in one subelement will affect other subelements in the same sector.

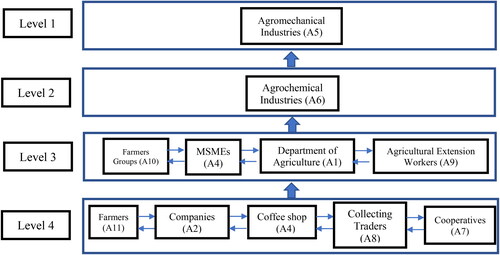

Supporting subsystem

Based on the ISM analysis of 11 subelements showing the agribusiness actors involved in the agribusiness subsystem supporting Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency, a hierarchical diagram of the supporting subsystem actors was built.

shows the subelements that were at the highest level or level 4, namely, farmer groups (A10), agricultural extension workers (A9), cooperatives (A7), agriculture offices (A1), and companies (A2). These subelements or agribusiness actors had the largest role in the agribusiness subsystem supporting Arabica coffee in the North Toraja Regency. In accordance with Dayat (Citation2017), agricultural instructors have a critical role in the supporting subsystem of the agribusiness system. Meanwhile, cooperatives’ important role is in plantation crops in distributing aid, guidance and counseling, and mentoring (Jamil et al., Citation2022). The strength and influence of the subelements of the agribusiness actors on the Arabica coffee agribusiness system based on driving power (DP) and dependence (D) are shown in .

Figure 11. Diagram of the hierarchy of the subelements of the agribusiness subsystem actors supporting Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency.

Figure 12. Driving power (DP) and dependency (D) matrix of the supporting agribusiness subsystem actors in North Toraja Regency.

shows the driving power (DP) and dependency (D) matrix of 11 subelements grouped into 4 sectors. shows no subelements in sectors I (autonomous) and II (dependent). There were 10 subelements in sector III (linkage), namely, government services (A1), companies (A2), coffee shops (A3), MSMEs (A4), agromechanical industry (A5), agrochemical industry (A6), cooperatives (A7), collecting traders (A8), agricultural extension workers (A9), and farmer groups (A10). The subelements in sector III (linkage) had the power to support supporting agribusiness subsystems and influence each other. Meanwhile, one subelement, farmers (A11), was in sector IV (independent), which means farmers had little power to support the subsystem but still depended on the Arabica coffee supporting agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency. The research (Mulyani et al., Citation2018) concludes that there is hope for developing effective farmer institutions that can contribute significantly to the independence and dignity of farmers.

The actors involved in the Arabica coffee agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency are the following ()

Performance of Arabica coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja regency

The following are the results of the IPA to see the performance of Arabica coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency in each subsystem.

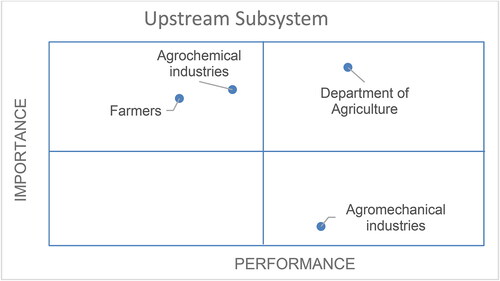

Upstream subsystem

Based on the results of the IPA related to the performance of the actors in the upstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency, the average value of the performance level (x) was 4.02, the average value of the importance level (y) was 4.23, and the average conformity level between the performance and importance levels was 97.82. The average value of performance level (x) and average importance (y) as the centerline in the Cartesian diagram of IPA is depicted in .

Figure 14. Cartesian diagram of the importance–performance analysis (IPA) results of upstream agribusiness subsystem actors. Note: Quadrant I: High-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant II: High-stake actors and good performance. Quadrant III: Low-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant IV: Low-stake actors and good performance.

As shown in , the agribusiness actors in quadrant I were farmers and the agrochemical industry. The agribusiness actors in quadrant I had a low performance with high importance in providing production facilities. The low performance of farmers was caused by the use of agricultural tools and machinery that did not follow the needs of the land and the lack of human resources who can operate these machines. This is supported by the opinion of Ortega et al. (Citation2019). Technology is used as a support for farm production, but it requires expertise from humans (farmers). However, from the observations in the field, the nonoptimal use of assisted agricultural tools and machines is also influenced by the lack of motivation of the management of the agricultural tool and machine service business to optimize the use of assisted agricultural tools and machines, as well as independent agricultural tool and machine service entrepreneurs who obtain agricultural tools and machines at their own expense. There is no reliance on supporting institutions for the upstream agri-industry subsystem, which includes money, land, labor, fertilizers, pesticides, agricultural equipment, and tools (Suoth et al., Citation2019). Even though the government developed an agricultural machinery and tool service unit to accelerate farmers’ adoption of agricultural tools and machines, another thing affecting farmers’ performance is the unaffordable price of fertilizer. The agrichemical industry is performing poorly because of unaffordable seed prices and agricultural tools and machinery used by farmers that are not appropriate. The use of agrochemicals can cause problems in the soil in the form of heavy metals and a decrease in the quality of agricultural products, so the practice must be decreased (Mulyani et al., Citation2018).

The actor in quadrant II was the agriculture office. The Department of Agriculture has performed exceptionally well and has fulfilled its role in providing production facilities for farmers. In addition, the actor in quadrant IV was the agromechanical industry. The agromechanical industry has provided agricultural tools and machinery for farmers, but farm management was not the main need of farmers because most farmers still used simple tools and had limited capital to buy products. Agricultural tools and machinery can replace manual labor and shorten working time on farmland (Purwantoro et al., Citation2019).

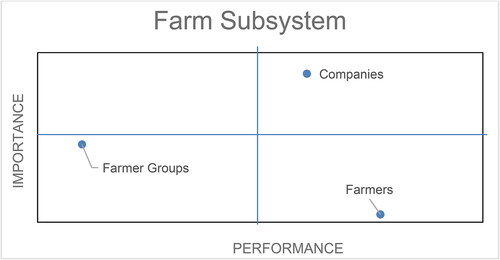

Farm subsystem

Based on the results of the IPA related to the performance of the actors in the Arabica coffee farming agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency, the average value of the performance level (x) was 3.97, the average value of the importance level (y) was 3.88, and the average conformity level between the performance and importance levels was 102.81. The success of agribusiness systems can be reached when the productivity is over 60% (Kurnia et al., Citation2024). The average value of performance level (x) and average importance (y) as the centerline in the Cartesian diagram of IPA is depicted in .

Figure 15. Cartesian diagram of the importance–performance analysis (IPA) results of agribusiness subsystem actors. Note: Quadrant I: High-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant II: High-stake actors and good performance. Quadrant III: Low-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant IV: Low-stake actors and good performance.

shows three agribusiness actors in the farming subsystem: companies, farmer groups, and farmers. The company was in quadrant II, meaning that aspects related to its performance were considered appropriately implemented, so they must be maintained and managed properly. Farmer groups were in quadrant III or were considered to have low importance and performance. The role of farmer groups was considered less important and, in its implementation, has not been maximized because farmer groups were only used as a forum to get assistance from the government, and the role of the administrators of farmer groups was less functioning. This is supported by the findings of Mustika and Sulistyowati (Citation2017) that the performance of the farmer group was in the low category due to the low activeness of the members. Thus, the group did not run as it should and the skills of farmers do not increase due to the lack of training. In addition, establishing these institutions was not participatory, so it could not accommodate the potential and interests of farmers, which should be the capital for collective action. Although the actors in quadrant IV were farmers, it shows that although farmers have managed their farms well, the role of farmers has not been able to support the farming subsystem. This is because the managerial ability of farmers was still relatively low. Community coffee farming results were still low in quality due to the low ability and managerial skills in managing their agricultural land. If the managerial aspects of farmers were improved, it would influence the success of coffee farming (Fitriyani et al., Citation2021; Wahyuni et al., Citation2023).

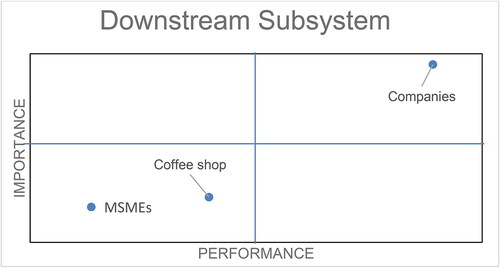

Downstream subsystem

Based on the results of the IPA related to the performance of the actors in the downstream agribusiness subsystem of Arabica coffee in North Toraja Regency, the average value of the performance level (x) was 3.97, the average value of the importance level (y) was 3.95, and the average conformity level between the performance and importance levels was 100.67. The average value of performance level (x) and average importance (y) as the centerline in the Cartesian diagram of IPA is depicted in .

Figure 16. Cartesian diagram of the importance–performance analysis (IPA) results of downstream agribusiness subsystem actors. Note: Quadrant I: High-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant II: High-stake actors and good performance. Quadrant III: Low-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant IV: Low-stake actors and good performance.

As shown in , the agribusiness actor in quadrant II was companies. The company performs fairly well and has carried out its role in managing Arabica coffee production. The agribusiness actors in III were MSMEs and coffee shops, meaning their importance and performance levels were low. MSMEs and coffee shops were considered to play a less important role in the downstream subsystem. This happened because of several problems with MSME actors, namely, the lack of capital and difficulty obtaining a business license. This opinion is supported by Mayningrum and Muhtadi (Citation2021), who stated that the problems faced by MSME actors were declining sales, difficulties in obtaining capital and managing business licenses, minimal coaching, facilities, technology that have not been maximized, difficulties in marketing products online, operating digital platforms, and creating sales materials.

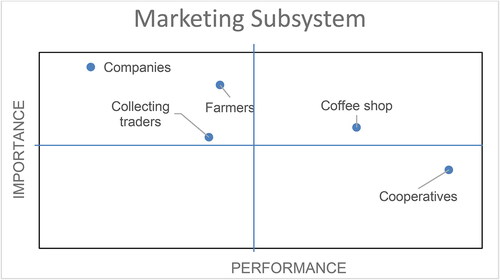

Marketing subsystem

Based on the results of the IPA related to the performance of the actors in the Arabica coffee marketing agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency, the average value of the performance level (x) was 3.81, the average value of the importance level (y) was 4.00, and the average conformity level between the performance and importance levels was 95.97. The average value of performance level (x) and average importance (y) as the centerline in the Cartesian diagram of IPA is depicted in .

Figure 17. Cartesian diagram of the importance–performance analysis (IPA) results of marketing agribusiness subsystem actors. Note: Quadrant I: High-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant II: High-stake actors and good performance. Quadrant III: Low-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant IV: Low-stake actors and good performance.

shows that the agribusiness actors in quadrant I were companies, traders, collectors, and farmers, meaning they have a high importance level but a low performance level. Farmers had the lowest performance level of the three actors in quadrant I because there was no selling price protection for farmers, and the price of Arabica coffee products did not follow the quality offered. Farmers who sell to collectors or via farmer associations will get the lowest price; those who deal with the Joint Business Group will receive the highest price (Noer, Citation2022). Although the agribusiness actor in quadrant II was coffee shops, coffee shops could market Arabica coffee well. In addition, the agribusiness actor in IV was cooperatives. The role of cooperatives was considered less important because farmers usually went directly to collecting traders compared to selling to cooperatives. This is not in accordance with the research of Kansrini et al. (Citation2020), which stated the role of cooperatives as business partners, training providers, marketing facilitators, capital facilitators, and motivators in empowering coffee farmers.

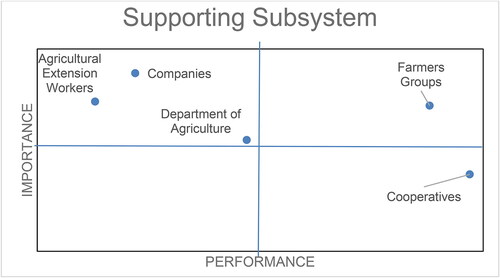

Supporting subsystem

On the basis of the results of the IPA related to the performance of the actors in the Arabica coffee supporting agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency, the average value of the performance level (x) was 3.73, the average value of the importance level (y) was 3.85, and the average conformity level between the performance and importance levels was 97.35. The average value of performance level (x) and average importance (y) as the centerline in the Cartesian diagram of IPA is depicted in .

Figure 18. Cartesian diagram of the importance–performance analysis (IPA) results of supporting agribusiness subsystem actors. Note: Quadrant I: High-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant II: High-stake actors and good performance. Quadrant III: Low-stake and low performance actors. Quadrant IV: Low-stake actors and good performance.

As shown in , the agribusiness actors in quadrant I were agricultural extension workers, companies, and the agriculture office, meaning that they have a high importance level but a low performance level so the aspects involved were a priority to improve their performance, considering the involvement of agribusiness actors in the supporting subsystem was important. The performance of the three actors in quadrant I was low because the agriculture office did not provide enough programs for developing Arabica coffee, and extension workers in their daily lives provided unsustainable training and assistance due to the lack of response from the farmers themselves and long distances to the work area. These results are in line with research conducted by Suprianto et al. (Citation2023); the performance of extension workers was in a low category, in terms of the completeness of the administrative indicators of assisted farmers and the implementation of the main task. These two factors must concern extension workers so that assisted farmers can increase Arabica coffee production and market access. Companies that buy farmers’ Arabica coffee products were not comprehensive because of the difficulty of transportation access to remote areas.

The agribusiness actor involved in quadrant II was farmer groups. Farmer groups play a crucial role in supporting farms, especially as a forum for individual farmers to access various farmers’ needs. In addition, the agribusiness actor in quadrant IV was cooperatives. Cooperatives serve as a forum for farmers in financial institutions, but only a few farmers’ used cooperatives as financial institutions because of complicated administrative requirements and farmers’ motivation in making low capital loans. They did not dare to take the risk of using a large capital for the development of their farms. Cooperatives play a very important role in the financial system, as a safe place to save and as a source of capital (McKillop et al., Citation2020). According to Anania et al. (Citation2020), agricultural marketing cooperatives (AMCOS) have the potential to improve the socioeconomic standing of the local farmers’ community as well as boost government income and fund the operations of organizations that assist the coffee sector.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the analysis of the performance data of Arabica coffee agribusiness actors, the actors who had a high importance level and low performance (Quadrant I) were the upstream subsystem: farmers and the agrochemical industry; marketing subsystem: companies, traders, gatherers, and farmers; and supporting subsystem: agricultural extension workers, companies, and agricultural agencies. The actors with a high importance level and good performance (Quadrant II) were the upstream subsystem: agriculture office; farming and downstream subsystems: companies; marketing subsystem: coffee shop; and supporting subsystem: farmer groups.

The actors with low importance and low performance (quadrant III) were the farming subsystem: farmer groups, and the downstream subsystem: MSMEs and coffee shops. Meanwhile, the actors with low importance and good performance (quadrant IV) were the upstream subsystem: agromechanical industry; farming subsystem: farmers; marketing subsystem: cooperatives; and the supporting subsystem: cooperatives. This study depicted the role of each actor in Arabica coffee agribusiness in North Toraja that should be strengthened to enhance the productivity and the marketing of the sector. The linkage of each activity can be regulated to build a new coordination system.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the coffee farmers, community leaders, coffee companies, government, and related stakeholders in North Toraja Regency; the Chancellor of Hasanuddin University; postgraduate school lecturers and staff; promoters; and copromoters for their participation and cooperation. All errors in this research are the responsibility of the author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [R], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rico

Rico is a doctoral student at the Agriculture Science Program, Graduate School Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. Rico is an Indonesian politician who serves as a member of the People’s Representative Council for the 2019–2024 period. He represents the constituency of West Papua. Rico is a cadre of the NasDem Party. Currently, he sits on Commission VII.

Rahim Darma

Rahim Darma is a professor in the Department of Socio-Economic, Agriculture Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. He obtained his PhD degree from the University of The Philippines at Los Banos in 1993.

Darmawan Salman

Darmawan Salman is a Professor in the Department of Socio-Economic, Agriculture Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. His specialization is in Rural Sociology and Development Planning. He earned his Doctor of Sociology degree (2002) at Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia.

Mahyuddin

Mahyuddin is a lecturer in the Department of Socio-Economic, Agriculture Faculty, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. He obtained his doctoral at Institut Pertanian Bogor, Indonesia in 2012.

References

- Abdel-Fattah, A., & Al Hiary, M. (2023). A participatory multicriteria decision analysis of the adaptive capacity-building needs of Jordan’s agribusiness actors discloses the indirect needs downstream the value chain as “post-requisites” to the direct upstream needs. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1026432

- Anania, P., Rwekaza, G. C., & Bamanyisa, J. M. (2020). Socio-economic benefits of agricultural marketing co-operatives and their challenges: Evidence from selected cases in Moshi District Council (Tanzania). Ager, 2020(30), 97–146. https://doi.org/10.4422/ager.2020.07

- Arsyad, L., & Kusuma, S. E. (2014). Ekonomika industri: Pendekatan struktur, perilaku, dan kinerja [Industrial economics: A structure, behavior and performance approach]. UPP STIM YKPN.

- DaMatta, F. M., Rahn, E., Läderach, P., Ghini, R., & Ramalho, J. C. (2019). Why could the coffee crop endure climate change and global warming to a greater extent than previously estimated? Climatic Change, 152(1), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2346-4

- Darma, R., Salman, D., Rico, & Mahyuddin, (2024). Examining the effect of agribusiness actors’ performance on the performance of Arabica coffee agribusiness subsystem in North Toraja Regency.International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 19(4), 1471–1484. https://doi.org/10.18280/ijsdp.190424

- Davis, A. P., Chadburn, H., Moat, J., O'Sullivan, R., Hargreaves, S., & Nic Lughadha, E. (2019). High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability. Science Advances, 5(1), eaav3473. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3473

- Dayat, D. (2017). Kepuasan petani dalam pelaksanaan penyuluhan berorientasi agribisnis padi di Kabupaten Bogor [Farmer satisfaction in implementing rice agribusiness-oriented extension in Bogor Regency]. Jurnal Penyuluhan Pertanian, 12(2), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.51852/jpp.v12i2.354

- de Campos Filho, E. S., & de Oliveira, E. C. (2024). ESG and agribusiness: A possible combination? In Harmony of knowledge: Exploring interdisciplinary synergie (1st ed.). Seven Editora.

- Febryan, E. I., Winarno, S. T., & Setyadi, T. (2023). Arabica coffee agribusiness in Prigen District, Pasuruan Regency. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 7(7), 1189–1196. https://doi.org/10.47772/IJRISS.2023.70794

- Fitriyani, I., Rahayu, S., & Sudiyarti, N. (2021). Keberhasilan usaha tani kopi Tepal melalui manajerial petani [The success of the Tepal coffee farming business through farmer management]. Jurnal TAMBORA, 5(3), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.36761/jt.v5i3.1317

- Ghalem, Â., Okar, C., Chroqui, R., & Semma, E. (2016). Performance: A concept to define. LOGISTIQUA 2016. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.24800.28165

- Gorvet, R., & Liu, N. (2007). Using interpretive structural modeling to identify and quantify interactive risks. ASTIN Colloquium.

- Grabs, J., & Ponte, S. (2019). The evolution of power in the global coffee value chain and production network. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(4), 803–828. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbz008

- Guimarães, E. R., dos Santos, A. C., Leme, P. H. M. V., & da Silva Azevedo, A. (2020). Direct trade in the specialty coffee market: Contributions, limitations and new lines of research. Internext, 15(3), 34–62. https://doi.org/10.18568/internext.v15i3.588

- Hasnida, H., Nuraeni, N., & Hasan, I. (2021). Analisis sistem agribisnis kopi Arabika di Desa Tolajuk, Kecamatan Latimojong, Kabupaten Luwu [Analysis of the Arabica coffee agribusiness system in Tolajuk Village, Latimojong District, Luwu Regency]. Wiratani: Jurnal Ilmiah Agribisnis, 4(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.33096/wiratani.v4i1.132

- Hernandez-Aguilera, J. N., Gómez, M. I., Rodewald, A. D., Rueda, X., Anunu, C., Bennett, R., & van Es, H. M. (2018). Quality as a driver of sustainable agricultural value chains: The case of the relationship coffee model. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2009

- Hunt, D. A., Tabor, K., Hewson, J. H., Wood, M. A., Reymondin, L., Koenig, K., Schmitt-Harsh, M., & Follett, F. (2020). Review of remote sensing methods to map coffee production systems. Remote Sensing, 12(12), 2041. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12122041

- Indrawanto, C. (2009). Kajian pengembangan industri akar wangi (Vetiveria zizanoides L.) menggunakan interpretative structural modelling [Analysis of vetiver (Vetiveria zizanoides L.) industry development using interpretative structural modelling]. Informatika Pertanian, 18(1), 1–18.

- Irawati, E., & Yantu, M. R. (2015). Kinerja kelompok tani dalam menunjang pendapatan usahatani padi sawah di Desa Sidera Kecamatan Sigi Biromaru Kabupaten Sigi [The performance of farmer groups in supporting the income of lowland rice farming in Sidera Village, Sigi Biromaru District, Sigi Regency]. Agrotekbis, 3(2), 206–211.

- Jacobi, J., Lara, D., Opitz, S., de Castelberg, S., Urioste, S., Irazoque, A., Castro, D., Wildisen, E., Gutierrez, N., & Yeretzian, C. (2024). Making specialty coffee and coffee-cherry value chains work for family farmers’ livelihoods: A participatory action research approach. World Development Perspectives, 33, 100551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2023.100551

- Jamil, M., Budi, S., & Indriana, D. (2022). Peranan koperasi dalam pengembangan sistem agribisnis kakao (Studi kasus: Koperasi perkebunan kakao Bireuen) [The role of cooperatives in developing the cocoa agribusiness system (Case study: Bireuen cocoa plantation cooperative)]. Agrifo: Jurnal Agribisnis Universitas Malikussaleh, 7(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.29103/ag.v7i1.11613

- Kansrini, Y., Zuliyanti, A., Mulyani, P. W., & Pirmansyah, D. (2020). Peran koperasi dalam pemberdayaan petani kopi di Kabupaten Mandailing Natal [The role of cooperatives in empowering coffee farmers in Mandailing Natal District]. JOSETA, 2(2), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.25077/joseta.v2i2.241

- Karyani, T., Djuwendah, E., Sadeli, A. H., Marlina, I., & Supriadi, R. E. (2018). Penumbuhkembangan agribisnis kopi Arabica Java Preanger: Dari pangalengan ke pasar dunia (Studi kasus di koperasi produsen kopi Margamulya) [Growth and development of Java Preanger Arabica coffee agribusiness: From Pangalengan to the world market (Case study of the Margamulya coffee producer cooperative)]. Jurnal Agribisnis Terpadu, 11(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.33512/jat.v11i1.5081

- Kurnia, R., Andrie, B. M., & Aziz, S. (2024). Keragaan usahatani dan kinerja agribisnis jagung di Kabupaten Ciamis [Farming performance and performance of corn agribusiness in Ciamis Regency]. Mimbar Agribisnis, 10(1), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.25157/ma.v10i1.12197

- Ley, S. V., Chen, Y., Robinson, A., Otter, B., Godineau, E., & Battilocchio, C. (2021). A comment on continuous flow technologies within the agrochemical industry. Organic Process Research & Development, 25(4), 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00534

- Malta, M. (2011). Faktor-faktor yang berhubungan dengan kinerja petani jagung di lahan gambut [Factors related to the performance of corn farmers on peatlands]. MIMBAR, 27(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.29313/mimbar.v27i1.313

- Mayningrum, S., & Muhtadi, K. (2021). i-SMARTS: Digitalization of agrotechnopreneurship-based MSME development to support acceleration of East Java economic recovery in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic.East Java Economic Journal, 5(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.53572/ejavec.v5i1.56

- McKillop, D., French, D., Quinn, B., Sobiech, A. L., & Wilson, J. O. S. (2020). Cooperative financial institutions: A review of the literature. International Review of Financial Analysis, 71, 101520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101520

- Ministry of Industry. (2018). Statistika kopi indonesia [Indonesian Coffee Statistics]. Ministry of Industry. https://kemenperin.go.id/

- Mulyani, O., Sofyan, E. T., & Nurbaity, A. (2018). Pengaruh jenis amelioran dalam berbagai taraf pemberian dosis Cd terhadap tanah dan tanaman [The influence of the type of ameliorant at various levels of Cd dosage on soil and plants]. Jurnal Agrotek Indonesia, 3(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.33661/jai.v3i1.1163

- Mustika, I. G., & Sulistyowati, L. (2017). Hubungan tingkat partisipasi anggota dengan kinerja gabungan kelompok tani (Suatu kasus di Gapoktan Kopi Arjuna, Kecamatan Lembang, Kabupaten Bandung Barat) [The relationship between the level of member participation and the combined performance of farmer groups (a case in Gapoktan Kopi Arjuna, Lembang District, West Bandung Regency)]. Mimbar Agribisnis, 3(2), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.25157/ma.v3i2.341

- Nasution, M. N. (2001). Manajemen mutu terpadu [Total quality management]. Ghalia Indonesia.

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 392–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.392

- Njonge, T. (2023). Influence of psychological well-being and school factors on delinquency, during the Covid-19 period among secondary school students in selected schools in Nakuru County: Kenya. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 7(2), 1175–1189.

- Noer, I. (2022). Collective marketing performance of coffee beans in Lampung Province. International Journal of Applied Business and International Management, 7(2), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.32535/ijabim.v7i2.1725

- Ortega, D. L., Bro, A. S., Clay, D. C., Lopez, M. C., Tuyisenge, E., Church, R. A., & Bizoza, A. R. (2019). Cooperative membership and coffee productivity in Rwanda’s specialty coffee sector. Food Security, 11(4), 967–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00952-9

- Pan, Y., Smith, S. C., & Sulaiman, M. (2018). Agricultural extension and technology adoption for food security: Evidence from Uganda. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(4), 1012–1031. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay012

- Purwantoro, D., Dianpratiwi, T., & Markumningsih, S. (2019). Analisis penggunaan alat mesin pertanian berbasis traktor tangan pada kegiatan perawatan budidaya tebu [Analysis of the use of hand tractor-based agricultural machinery in sugar cane cultivation maintenance activities]. Agritech, 38(3), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.22146/agritech.28149

- Putri, R. E., Abidin, Z., & Kasymir, E. (2018). Analisis perbedaan kinerja petani kakao mitra dan non mitra dengan PT Olam Indonesia di Kabupaten Pesawaran [Analysis of differences in the performance of partner and non-partner cocoa farmers with PT Olam Indonesia in Pesawaran Regency]. Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Agribisnis, 6(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.23960/jiia.v6i1.79-86

- Rangkuti, F. (2006). Measuring customer satisfaction: Teknik mengukur dan strategi meningkatkan kepuasan pelanggan plus analisis kasus PLN-JP [Measuring customer satisfaction: Measuring techniques and strategies to increase customer satisfaction plus PLN-JP case analysis]. Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- Rospa, E. A. (2022). Analisis struktur, perilaku, dan kinerja pemasaran komoditas beras di Desa Bontotanga Kecamatan Bontotiro Kabupaten Bulukumba [Analysis of the structure, behavior and marketing performance of rice commodities in Bontotanga Village, Bontotiro District, Bulukumba Regency] [Bachelor’s thesis]. Universitas Muhammadiyah Makassar.

- Salam, M., Viantika, N. M., Amiruddin, A., Pinontoan, F. M., & Rahmatullah, R. A. (2021). Value chain analysis of Toraja coffee. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 681(1), 012115. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/681/1/012115

- Santi, L. P., Nurwiana, I., & Sinu, I. (2022). Strategi pengembangan subsistem pemasaran agribisnis kopi Arabika di Kelurahan Compang Carep Kecamatan Langke Rembong Kabupaten Manggarai [Strategy for developing the Arabica coffee agribusiness marketing subsystem in Compang Carep Village, Langke Rembong District, Manggarai Regency]. Jurnal Excellentia, 11(1), 17–25.

- Sedana, G., & Astawa, N. D. (2019). Establishment of inclusive business on coffee production in Bali province: Lesson from the coffee development project in Nusa Tenggara Timur province, Indonesia. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, 9(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1005/2019.9.1/1005.1.111.122

- Silva, L. C. S., & Palata, L. F. (2023). Innovation in agribusiness as strategic tool in development of the sector in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 18(1), e04105–e04105. https://doi.org/10.24857/rgsa.v18n01-002

- Sisfahyuni, S. (2008). Kinerja kelembagaan input produksi dalam agribisnis padi di Kabupaten Parigi Moutong [Institutional performance of production inputs in rice agribusiness in Parigi Moutong Regency]. Agroland: Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Pertanian, 15(2), 122–128.

- Sunanto, S., Salim, S., & Rauf, A. W. (2019). Analisis kesepakatan peningkatan produktivitas kopi arabika pada pengembangan kawasan di Kabupaten Toraja Utara [Analysis of the agreement to increase Arabica coffee productivity in regional development in North Toraja Regency]. Jurnal Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian, 15(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.20956/jsep.v15i1.6369

- Suoth, V., Loho, A. E., & Ruauw, E. (2019). Keragaan sistem agribisnis kakao (Theobroma cacao) di Kabupaten Bolaang Mongondow Utara [Performance of the cocoa (Theobroma cacao) agribusiness system in North Bolaang Mongondow Regency]. AGRI-SOSIOEKONOMI, 15(2), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.35791/agrsosek.15.2.2019.24500

- Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16(3), 282–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

- Suprianto, A., Lamane, S. A., & Suprayitno, A. R. (2023). Kinerja penyuluh pertanian dalam pelaksanaan administrasi penyuluhan pertanian [Performance of agricultural instructors in implementing agricultural extension administration]. Jurnal Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian, 19(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.20956/jsep.v19i2.26551

- Syafii, A. (2017). Penilaian petani terhadap kinerja penyuluh pertanian (Studi kasus di Kelurahan Bonto Manai Kecamatan Bissappu Kabupaten Bantaeng) [Farmers’ assessment of the performance of agricultural instructors (Case study in Bonto Manai)] [Unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis]. Universitas Muhammadiyah Makassar.

- Ume, C. O., Enete, A. A., Onyekuru, A. N., & Opata, P. I. (2020). Evaluation of agribusiness performance in Nigeria. Africa Journal of Management, 6(4), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2020.1830690

- Wahyuni, L., Hambali, M., Rizal, M. S., Fibrianto, K., Bimo, I. A., & Rahman, K. (2023). Peningkatan kompetensi manajerial petani kopi untuk pengembangan wisata agraris “Lodji” Bromo [Increasing the managerial competence of coffee farmers for the development of Bromo’s “Lodji” agrarian tourism]. Jurnal Pengabdian UNDIKMA, 4(4), 798–806. https://doi.org/10.33394/jpu.v4i4.8938

- Wijaya, O., Rahayu, L., Rokhim, N., Yusmiastuti, T., & Utama, S. A. (2021). Piloting moringa agribusiness to improve villagers’ economic community. Journal of Community Service and Empowerment, 2(3), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.22219/jcse.v2i3.16442

- Yasmin, R. A. S., Lestari, D. A. H., & Marlina, L. (2022). Kinerja sistem agribisnis cabai merah pada kelompok tani tunas harapan [Performance of the red chili agribusiness system in the Tunas Harapan farmer group]. Jurnal Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian, 18(3), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.20956/jsep.v18i3.21620

- Yifru, G. S., & Miheretu, B. A. (2022). Farmers’ adoption of soil and water conservation practices: The case of Lege-Lafto Watershed, Dessie Zuria District, South Wollo, Ethiopia. PLOS One, 17(4), e0265071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265071