?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines how household perceptions of healthy broiler meat influence purchasing behavior in the Greater Jakarta Area. We surveyed 521 households using a multistage random sampling. Data analysis employed Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes models and ordered probit regression. Our key findings reveal that the majority of households fall within the medium perception category of healthy broiler meat. Purchasing practices align with perceptions, with households prioritizing healthier options when they perceive them as such. Furthermore, higher-income households are more likely to purchase healthier broiler meat. The dominance of wives in broiler meat purchase decisions suggests targeting women with educational initiatives that promote healthy food choices. This study highlights the importance of understanding household perceptions and purchasing practices toward healthy broiler meat, which can help support the development of healthy food products.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Indonesian consumers have a diverse selection of poultry options, each with distinct characteristics influencing their choices. However, within the Indonesian poultry landscape, three primary types of chicken meat are commonly consumed: broiler, native and culled layer chickens. Among these three, broiler meat reigns supreme in popularity, becoming one of the most important animal protein sources in Indonesia. Its consumption accounts for 77.3% of the total national meat consumption by 2023, with an average consumption of 7.35 kg/capita. Notably, urban areas exhibit a higher consumption rate (8.58 kg/capita) compared to rural areas (5.60 kg/capita) (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, Citation2023). The dominance of broiler meat is further highlighted by a projected rise to 9.3 kg/capita consumption by 2029 (Statista, Citation2022).

Broiler meat is popular due to its competitive pricing, easy accessibility and well-established production infrastructure. These factors, coupled with affordability and perceived nutritional benefits have fueled a remarkable growth of Indonesia’s broiler industry (Devatkal et al., Citation2019; Mueller et al., Citation2023). This strong foundation has propelled Indonesia to become the fastest-growing producer among the top 10 broiler meat-producing countries (Uzundumlu & Dilli, Citation2023). However, increasing consumer concerns about food quality and safety have led to a growing emphasis on the health aspects of broiler meat (Teixeira & Rodrigues, Citation2021). This shift in consumer perception presents both opportunities and challenges for the Indonesian broiler industry.

Despite its widespread consumption, concerns exist regarding the potential presence of contaminants and unsafe practices in broiler meat production. Studies have documented cases of broiler meat containing microbes, antibiotic residues exceeding permissible limits and even dangerous chemical additives (Ariningsih et al., Citation2023; Lestari, Citation2020). Additionally, concerns regarding non-halal slaughtering practices and the presence of ‘tiren’ chickens (those that died before slaughter) have also been raised.

This situation suggests a potential ‘health gap’ between consumer perceptions and broiler production practices. To bridge this gap, understanding how significant households attach to the health of broiler meat and the specific cognitive processes through which they interpret and understand information related to its health attributes is crucial. This includes aspects such as nutritional value, safety, production methods and ethical considerations. Furthermore, it is crucial to investigate whether these perceptions align with the actual purchasing practices. Understanding this gap can inform policy development related to production standards, pricing strategies, distribution channels that ensure accessibility and the effective sales promotion of healthy options (Neima et al., Citation2023).

By closing the gap between perception and practice, the industry can develop demonstrably healthier and safer poultry products that better meet consumer expectations. This knowledge also provides valuable insights into the importance of household perceptions and purchasing practices toward healthy broiler meat, ultimately supporting the development of a more sustainable and responsible broiler production system. As Zauner et al. (Citation2015) highlighted, understanding customer perceived value is key for businesses to gain competitive advantage. In this context, a focus on demonstrably healthy broiler meat production aligns perfectly with this notion of value creation.

While numerous studies have analyzed consumer preferences and behaviors toward purchasing broiler meat in Indonesia, a gap exists in understanding the specific factors influencing the purchase of healthy broiler meat. Most existing studies have focused primarily on the freshness and quality attributes of broiler meat (Fauzi & Wijaya, Citation2021; Ismanto et al., Citation2018; Mayulu et al., Citation2019; Simarmata et al., Citation2019), while others have addressed safety concerns (Indrawan et al., Citation2021; Setyanovina et al., Citation2021), halal aspects (Rosa et al., Citation2018) and the presence of safety and halal certifications (Indrawan et al., Citation2021; Priyambodo et al., Citation2021). To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have comprehensively examined household perceptions of healthy broiler meat and their impact on purchasing practices.

This study aims to address this gap by (1) examining household perceptions of healthy broiler meat, including the cognitive processes through which they interpret and understand information related to its health attributes and (2) determining the factors that influence households’ purchasing practices for healthy broiler meat.

Methods

Theoretical framework

Perception is the fundamental process by which our brains actively receive, select, process and interpret information from the world around us gathered through all our senses (Franz & Sarcina, Citation2009; Nalindah et al., Citation2022; Qiong, Citation2017). Consumer perception is a complex concept encompassing various factors that influence how consumers view products and services. These factors include perceived value, perceived convenience, perceived risk, customer service and subjective consumer demonstration (Wang et al., Citation2023). Due to various cultural backgrounds, people interpret objects and events differently, leading to diverse verbal and non-verbal behaviors (Qiong, Citation2017).

Consumer perception plays a crucial role in influencing purchase decisions. How consumers perceive products or services shapes their beliefs and attitudes, ultimately impacting their decision to buy (Wang et al., Citation2023). Perception, therefore, is a critical factor in shaping consumer preferences (Mišík, Citation2015). Studies have shown a strong correlation between consumer perception and consumption dimensions (Boada et al., Citation2023). This highlights the significant influence perception has on consumer behavior. However, it is not the sole driver of purchasing decisions. While perception plays a major role, three core factors also significantly influence consumer choices: price, product and place (Akbar & Bakar, Citation2011). Businesses that understand the interplay between consumer perception and these factors can develop effective strategies to target and engage their customer base.

Study area

This study was conducted in the Greater Jakarta Area (Jabodetabek), which is the most populous metropolitan area in Indonesia. It encompasses the capital city, Jakarta Special Capital Region (DKI Jakarta), as its core and several surrounding satellite cities: Bogor City, Depok City, Bekasi City (all in West Java Province) and Tangerang City (Banten Province). Within DKI Jakarta, East Jakarta City was specifically chosen to represent the region.

The Greater Jakarta Area was strategically selected for this study due to its key characteristics: high consumption rates and diverse population. DKI Jakarta and West Java have the highest participation rates for chicken meat consumption in Indonesia, at 54.7% and 49.1%, respectively (Ariani et al., Citation2018). This makes the Greater Jakarta Area a prime location for understanding the national consumption trends. Additionally, encompassing multiple provinces and cities, the Greater Jakarta Area represents a diverse population with potentially varying consumption patterns and preferences. This diversity enriches the generalizability of our study findings. By focusing on this vast urban agglomeration, this study provides valuable insights into consumer behavior within a region, which plays a crucial role in shaping national broiler meat consumption patterns.

Data collection

Data collection for this study was conducted in August and September 2023. The target population consisted of households within the Greater Jakarta Area that consumed broiler meat at least once in the previous month.

A multistage random sampling approach was employed to select the respondents. In the first stage, one sub-district with a medium population density was chosen within each city of the Greater Jakarta Area. Subsequently, one to three villages within each sub-district were selected based on two criteria: a medium population density and the presence of both housing and non-housing estates. Finally, the respondents were randomly selected from each village, resulting in a total sample size of 521 households with couples.

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaires administered by 10 trained enumerators. The questionnaire comprised three sections: (1) household characteristics, including information about household size, income level and demographics; (2) household perceptions of the health aspects of broiler meat, including concerns about freshness, cleanliness and safety and (3) purchasing practices related to broiler meat, including preferred sources, frequency of purchase and factors influencing buying decisions.

Empirical model

Household perception of the healthy broiler meat

Individual and household perceptions of the health aspects of broiler meat are influenced by various factors, including knowledge, experience and personal beliefs. However, ‘perception’ itself is a latent variable, meaning it cannot be directly observed but can be measured through its indicators. The Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) model is employed to estimate this latent variable and understand its underlying structure. This approach, pioneered by researchers like Zellner (Citation1970) and Joreskog and Goldberger (Citation1975), allows us to analyze how multiple observed variables collectively represent and contribute to the overall construct of consumer perception regarding healthy broiler meat. Recent studies have applied this model to the agricultural sector (eg Ibrahim, Citation2022; McLeod et al., Citation2019; Mensah et al., Citation2023).

The MIMIC model consists of two key types of equations: structural and measurement (Richards & Jeffrey, Citation2000). This allows us to analyze the two crucial aspects simultaneously. Structural equations model the relationships between the latent variable (eg consumer perception of healthy broiler meat) and the causal variables (eg knowledge, experience) that influence it. This provides insights into the factors driving changes in the latent variable. Meanwhile, measurement equations describe how the observed indicators (eg responses to survey questions related to safety indicators) reflect the underlying latent variable. This helps us understand how well the chosen indicators capture the intended construct.

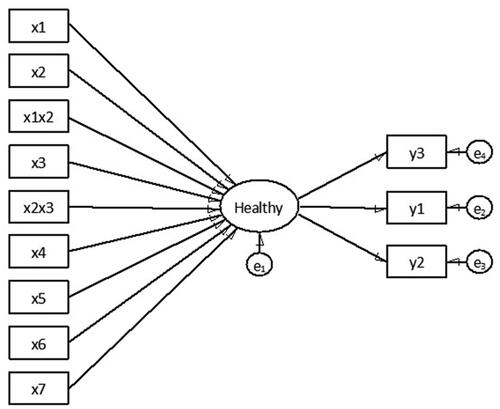

We employed a MIMIC 9-1–3 model to analyze the relationships between nine hypothesized causal factors and the latent variable ‘Healthy’, representing consumer perception of healthy broiler meat (). These factors include variables x1 to x7 and the interaction terms x1x2 and x2x3. This approach allowed us to analyze how these individual factors and their potential interactions contribute to the overall perception of healthy broiler meat. In addition, this model utilized three observed indicators, namely, freshness (y1), cleanliness (y2) and safety (y3), to capture the underlying construct of ‘Healthy’.

The nine causal factor variables employed in this model are listed as follows: x1 is an ordinal variable representing monthly household income categorized into seven levels (1: ≤IDR 5 million, 2: >IDR 5 million − ≤IDR 10 million, 3: >IDR 10 million − ≤IDR 15 million, 4: >IDR 15 − ≤IDR 20 million, 5: >IDR 20 million − ≤IDR 25 million, 6: >IDR 25 million − ≤IDR 30 million and 7: >IDR 30 million), x2 is a variable representing the age of the head of household in years, x1x2 is a variable representing an interaction of household income (x1) and head of household age (x2), potentially capturing potential interactions between these factors, x3 is an ordinal variable representing the highest education level attained by the head of household (1: elementary school (SD), 2: junior high school (SMP), 3: senior high school (SMA), 4: diploma (D3)/undergraduate (S1), 5: postgraduate (S2)/S3), x2x3 is an combination of head of household age (x2) and education level (x3), potentially capturing potential interactions between these factors, x4 is a variable representing spouse’s age in years, x5 is an ordinal variable representing the highest education level attained by the spouse, categorized similarly to x3, x6 is a variable representing the number of different places where household can purchase broiler meat, and x7 is a variable indicating the spouse’s employment status (0: not working/housewife, 1: working).

The values (scores) for freshness (y1), cleanliness (y2) and safety (y3) were formulated as follows:

(1)

(1)

The indicator variables, frshm, clnn and sftyz, represent the perceived freshness, cleanliness and safety of the broiler meat, respectively. These variables are binary, with 0 indicating a negative perception (‘no’) and 1 indicating a positive perception (‘yes’) based on the respondents’ answers to specific questionnaire items in Appendix A. The MIMIC model was estimated using the maximum likelihood method, with respondent residence included as a critical weight to account for potential variations in perceptions across different locations within the Greater Jakarta Area.

Factors influencing household purchasing practices of healthy broiler meat

Field observations and existing research (Cheng et al., Citation2016; Katiyo et al., Citation2020; Kendall et al., Citation2019; Maitiniyazi & Canavari, Citation2021; Wertheim-Heck et al., Citation2019) suggest that the location of purchase can influence perceived broiler meat quality and safety. Supermarkets (modern markets) are generally associated with higher quality and safer meat compared to other outlets.

In Indonesia, broiler meat distribution occurs through both traditional and modern channels (Surni et al., 2021), catering to all income groups. Consumers have access to at least eight types of purchase locations (L), categorized into three main groups: (1) L1: roadside stalls, vegetable/produce kiosks with meat, mobile vegetable/meat vendors, mobile broiler meat vendors and other occasional sellers, (2) L2: traditional markets and (3) L3: modern markets (hypermarts, supermarkets, specialized meat shops, online marketplaces). Observations and government regulations suggest a hierarchy of perceived health guarantees associated with these purchase locations, with L3 (modern markets) having the highest level, followed by L2 (traditional markets) and lastly L1 (other locations) (L3 > L2 > L1).

Consistency in purchasing healthier broiler meat is likely related to the frequency (F) of purchases at higher-guarantee locations (L) and the average purchase volume (V) from those locations. Therefore, the model considers a combined assessment of three dimensions: purchase location (L), purchase frequency (F) and purchase volume (V). These dimensions have varying weights assigned, reflecting their importance in influencing consumer perception. Location (L) receives the highest weight because it represents the initial choice available to all consumers. Frequency (F) has a secondary weight due to its influence on the number of ‘healthy’ purchase actions. Volume (V) receives the lowest weight, as it amplifies the impact of frequency but is not directly related to action consistency. By incorporating the number of broiler meat purchase locations (x6) into the MIMIC model, we can analyze how the diversity of a household’s purchasing options and their choices within that range influence their overall perception of healthy broiler meat.

For example, if yi is the ith consumer action in purchasing healthier broiler meat, then

(2)

(2)

The subscripts in the equation denote the following categories. Location (L): l = 1: L1 (roadside stalls, vegetable/produce vendors, etc.), l = 2: L2 (traditional markets) and l = 3: L3 (modern markets). Frequency of purchase (F): f = 1: purchase 1–3 times per month, f = 2: purchase once per week and f = 3: purchase 2–7 times per week. Average purchase quantity (V): v = 1: purchase ≤1 kg per time, v = 2: purchase >1 kg–2 kg per time and v = 3: purchase > 2 kg per time.

Furthermore, if yj is the grouping of yi into three categories, then:

(3)

(3)

Several factors influence the likelihood of a consumer being classified as y = 1, y = 2, or y = 3. These factors likely include, among others, their perception of the health aspects of the broiler meat they purchase, their accessibility to different purchase locations with varying hygiene standards and household income.

Ordered regression models are appropriate tools when dealing with choices with the natural order, like consumer classifications based on their perception of healthy broiler meat (Long & Freese, Citation2014). These models analyze the factors influencing the probability of falling into a specific category within the ordered sequence. This study employs an ordered probit (oprobit) regression model. This specific choice is based on the assumption that the error terms in the model follow a normal distribution. The model can be expressed as follows:

(4)

(4)

where Φ(·) denotes the standard normal cumulative distribution function.

The log-likelihood is:

(5)

(5)

where wi is the optional weighting, which in this study was assumed to be 1. The model incorporates several independent variables (vector V) that potentially influence consumer classification regarding healthy broiler meat perception. These variables can be categorized as follows: (1) continuous variables: heal represents the predicted latent variable ‘Healthy’ derived from the MIMIC model, reflecting the consumer’s overall perception of healthy broiler meat, v1 is the household size (number of people residing in the household), v2 is the distance (in kilometers) from the household’s residence to the nearest modern market, v3 is the distance (in kilometers) from the household’s residence to the nearest traditional market, v4 is the ratio between the score assigned to favorite broiler meat purchase locations and the total number of usual purchase locations. This potentially indicates a preference for specific types of stores, (2) dummy variables: D1 is a dummy variable for household income, with three categories (1: ≤IDR 5 million per month, 2: >IDR 5 million – IDR 10 million per month, 3: >IDR 10 million per month), D2 is a dummy variable for spouse’s employment status, with two categories (0 = not working/housewife, 1 = working), D3 is a dummy variable of housing type, with two categories (1 = housing estate, 2 = non-housing estate), and D4 is a dummy variable that reflects consumer attitudes toward broiler meat price, with two categories (0 = less concerned about price, 1 = concerned about price).

In general, consumer behavior in purchasing goods and services is influenced by purchasing power. The results of the preliminary analysis also show similar phenomena. To ensure the robustness of our findings, the model was estimated using the rigorous maximum likelihood with variance cluster errors (vce) method. This method accounts for the potential clustering of errors within income groups, further enhancing the reliability of our results.

Stata version 15.1 software was used for data analysis.

Results

A brief picture of the broiler meat market di the Greater Jakarta Area

Most respondents (71.0%) resided in non-housing estates, indicating a potential skew toward a specific housing type. The average household size was 4.2 people. On average, heads of households (HH) were approximately four years older than their spouses. Household heads residing in housing estates tended to have higher education levels than those in non-housing estates. Spouses’ education levels showed less variation between housing types. The dominant occupation for heads of households in housing estates was civil servant (full-time or retired).

Conversely, heads of households in non-housing estates were more likely to be informal employees, with professions including online transportation services, small shops selling daily necessities, sales representatives, carpentry and casual labor. A significant income disparity existed between housing types. Around 70% of households in housing estates had a monthly income exceeding IDR 5 million. In contrast, most households in non-housing estates fell below that threshold (refer to for detailed income distribution).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of households.

This study highlights the wife’s dominant role in determining the quantity and location of broiler meat purchases (). This finding suggests her influence on household decisions regarding broiler meat acquisition. Households residing in housing estates tend to purchase broiler meat more frequently than those in non-housing estates. This difference in purchasing behavior might be related to factors such as income or accessibility. The choice of purchase location varies by residence type. Those in housing estates prefer a mix of traditional and modern markets, while those in non-housing estates favor roadside stalls or vegetable kiosks selling broiler meat. This result suggests a potential influence of factors such as store availability or perceived quality based on location.

Table 2. Purchase characteristics of broiler meat.

Freshness, cleanliness and safety are important aspects considered by households when purchasing broiler meat. The majority of respondents (90–97%) prioritize freshness and cleanliness, while safety receives slightly less emphasis. This highlights the importance of perceived hygiene factors when making purchasing decisions.

Household perception of the health aspects of broiler meat

The MIMIC 9-1–3 model demonstrated good performance in estimating household perceptions of healthy broiler meat. The key findings from the model evaluation are that all indicator variables (y1, y2, y3) representing the latent variable ‘Healthy’ were statistically significant and displayed consistency in the measurement equation (). This indicates that these indicators effectively capture the underlying concept of perceived healthiness. The model also passed a stability test, suggesting that the estimated relationships are reliable and not influenced by minor changes in the data.

Table 3. Structural and measurement estimates of MIMIC 9-1–3 applied in this study.

In addition, overall model goodness-of-fit tests revealed statistically significant likelihood ratios (chi-square values) for both the model versus saturated model (chi2 ms(18) = 47.215; p > .000) and the baseline versus saturated model (chi2 bs(30) = 805.948; p > .000). These results show that the parsimony applied in the MIMIC model in this study is well-fitted with the analyzed data and significantly contributes to explaining the relationship between the cause variables, latent variables and indicator variables in the dataset.

The estimated coefficients of the causal variables in the structural equation reveal several key findings. Variables related to the wife’s experience (x4) and knowledge (x5) regarding broiler meat exhibit positive coefficients, suggesting a positive influence of her knowledge and experience on household perceptions of healthy broiler meat. The number of accessible broiler meat purchase locations (x6) also has a positive coefficient, indicating that greater access to purchase options is associated with higher perceived healthiness. The significant coefficients of all three indicator variables (freshness (y1), cleanliness (y2) and safety (y3)) confirm their effectiveness in capturing the latent variable ‘Healthy’, representing household perceptions of healthy broiler meat. The positive signs of the coefficients for these indicators imply that higher scores on freshness, cleanliness and safety translate to a higher level of perceived healthiness.

To simplify the analysis of household perceptions, the predicted latent variable ‘heali’ was categorized into three levels based on its distribution: (1) low: heali ≤ {mean(heal) – sd(heal)}, (2) medium: {mean(heal) – sd(heal)} < heali ≤ {mean(heal) + sd(heal)} and (3) high: heali > {mean(heal) + sd(heal)}. As shown in , the majority of households (72.9%) fell within the ‘medium’ perception category. Consistent with expectations, the average level of perception was significantly higher for households residing in housing estates compared to those in non-housing estates.

Table 4. Household perceptions of the health aspects of broiler meat by housing type.

Factors influencing household purchasing practices of safe broiler meat

The ordered probit model results () reveal that six out of nine hypothesized variables significantly influence households’ likelihood of purchasing healthier broiler meat. Perception of healthiness positively influenced the likelihood of purchasing healthy broiler meat. This means that households with higher perceptions of healthiness have a higher probability of being classified as purchasing healthier options (higher-ranked Yj category). The same is true for households with larger household sizes and higher household incomes. This suggests that larger families or those with greater financial resources might prioritize or have the ability to afford healthier options. Likewise, greater access to locations selling healthy broiler meat, as captured by the number of accessible purchase locations (x6), increased the likelihood of choosing healthier options. This highlights the importance of having a variety of stores offering healthy broiler meat choices. Similarly, households with working spouses are more likely to purchase healthier broiler meat than those with non-working spouses. On the other hand, the type of housing (housing estate vs. non-estate) shows a negative coefficient, which means that households residing in non-housing estates are less likely to purchase healthier broiler meat than those residing in housing estates.

Table 5. Estimation results of the ordered probit model applied in this study.

The greatest likelihood (0.61 or 61%) of households falls within the Ys category. In addition to its higher mean probability, the coefficient of variation is also significantly lower compared to both Yr and Ys (). Therefore, using a probability threshold of 0.5, this phenomenon indicates that the household likelihood of purchasing healthier broiler meat in Greater Jakarta falls within the ‘moderate’ category. This applies to both housing estate and non-housing estate household communities.

Table 6. Household likelihood of purchasing healthier broiler meat by housing type.

Discussion

The MIMIC model analysis highlights the significant impact of the wife/spouse’s age and education on household perceptions of healthy broiler meat. This finding suggests that as the wife’s age and education level increase, so does her knowledge and experience regarding the health aspects of broiler meat. This finding aligns with a previous study by Utiah et al. (Citation2021), which also recognized age and education as important factors influencing decisions on broiler meat purchasing.

However, it is important to note that the model suggests a stronger influence of the wife’s characteristics compared to the husband’s. This can be partially explained by studies like Kitano and Yamamoto (Citation2020), which suggest that personal experiences are more impactful than information overload in shaping consumer preferences. In this context, the wife’s likely role in purchasing and preparing broiler meat might translate into a closer connection to the product, leading to a stronger influence on household perceptions. Furthermore, these findings echo observations from Yeboah et al. (Citation2023) regarding the wife’s dominant role in decision-making related to beef safety. This consistency across different types of meat suggests a potential pattern of wives playing a key role in household choices concerning the perceived healthiness of meat products.

While husbands traditionally hold the role of head of household (Putri & Lestari, Citation2015), some studies suggest that wives play a significant role in household purchasing decisions, including broiler meat (Priyambodo et al., Citation2021; Utiah et al., Citation2021). This study aligns with these findings, demonstrating that wives are the primary decision-makers regarding broiler meat quantity, location of purchase and likely the actual purchaser (responsible for buying). This prominent role of wives is further supported by research on consumer behavior in broiler meat purchases at traditional and modern markets (Fauzi & Wijaya, Citation2021; Indrawan et al., Citation2021; Priyambodo et al., Citation2021). These studies consistently report that women make up the majority of respondents and are the primary decision-makers. This aligns with the broader observation that grocery shopping for the family often falls under women’s responsibility (Mortimer & Clarke, Citation2011).

While the wife’s age and education influence household perceptions of healthy broiler meat, her employment status also plays a role. Many wives work to contribute significantly to family income, as shown by Tenda et al. (Citation2020), who reported that working wives contribute 40–60% of household income. However, the model suggests a negative effect of a wife’s employment on healthy broiler meat perception. This can be attributed to several factors. Working wives often have less time for shopping due to juggling work and household responsibilities. This might limit their ability to select broiler meat or explore various purchase locations carefully. Some working wives may delegate grocery shopping tasks, including broiler meat purchases, to domestic helpers. The helper’s knowledge or priorities might differ from the wife’s, potentially impacting the selection of broiler meat based on health aspects. Moreover, Lubna and Handayani (Citation2019) found that households with working wives tend to spend more on ready-to-eat meals. This suggests a potential shift toward convenience food options, which might not prioritize perceived health aspects to the same extent as traditional home-cooked meals.

Despite having access to multiple broiler meat purchase options (most respondents had access to more than three places to shop), a strong preference for traditional channels exists. Approximately 84.1% of respondents frequently purchase broiler meat from these traditional markets. This preference for traditional channels might be influenced by factors beyond mere accessibility. While visiting diverse outlets could potentially broaden experience and knowledge about sellers offering healthy broiler meat, the comfort and familiarity associated with traditional markets might outweigh the potential benefits. This aligns with the work of Wertheim-Heck et al. (Citation2014), which suggests that consumer responses to factors like food safety are often shaped by their established shopping routines and the limitations imposed by everyday life.

Several studies (Indrawan et al., Citation2021; Priyambodo et al., Citation2021; Setyanovina et al., Citation2021) highlight a connection between consumer preference for fresh (‘warm’) broiler meat and the popularity of traditional markets. This might be due to the perception that traditional markets offer fresher options. This aligns with the observation by Boateng et al. (Citation2023) that supermarkets are typically located in urban areas, potentially limiting access to ‘warm’ meat for some consumers.

While supermarkets are generally considered to offer higher quality and safer meat (Wertheim-Heck et al., Citation2019), they might also be perceived as more expensive and less fresh. This can lead lower-income consumers to rely more on traditional sellers (Wertheim-Heck & Spaargaren, Citation2016; Wertheim-Heck et al., Citation2015). However, there is evidence of a positive shift. Nugraha et al. (Citation2021) found that with increasing food safety awareness, consumers in traditional markets are paying closer attention to meat cleanliness, freshness and packaging.

Convenience often trumps other factors when choosing where to buy broiler meat (Fauzi & Wijaya, Citation2021). This explains why consumers frequently purchase from nearby vegetable/broiler meat stalls or mobile vendors. While these traditional outlets might raise concerns about hygiene (Ha et al., Citation2021), their accessibility outweighs those concerns for many consumers (Wertheim-Heck et al., Citation2014). However, quality remains a significant consideration. If meat quality at a convenient location falls short of expectations, consumers will switch to other sources perceived as offering better quality (eg supermarkets). In such cases, trust becomes a key factor, leading consumers to seek out established sellers with a reputation for safe and high-quality broiler meat (Kendall et al., Citation2019; Zorba & Kaptan, Citation2011).

This study revealed a higher average perception of healthy broiler meat among households residing in housing estates than those in non-housing estates. This difference might be attributed to factors associated with housing type. In this study, housing estates are related to residents with higher educational levels and incomes (). Additionally, the higher average housing prices within estates can be seen as an indicator of potentially greater economic resources. Education and income have been linked to a higher perception of healthy broiler meat in previous studies (eg Indrawan et al., Citation2021).

This study confirms a strong link between consumer perception and purchasing decisions. Households with a higher perception of healthy broiler meat are more likely to seek out and purchase healthier options. This finding aligns with previous studies demonstrating that consumers who value healthy eating habits are more likely to seek out healthy food options (Kendall et al., Citation2019; Liguori et al., Citation2022; Newson et al., Citation2015; Pham & Turner, Citation2020; Pradana et al., Citation2020; Soon et al., Citation2021).

However, income significantly affects access to these healthier options. As noted by Prokeinova and Hanova (Citation2016) and Fauzi and Wijaya (Citation2021), consumer purchasing power directly impacts behavior. Studies by Indrawan et al. (Citation2021) and Utiah et al. (Citation2021) further suggest a correlation between income and shopping locations, with higher-income households frequenting modern markets that potentially offer healthier broiler meat.

An interesting finding is that working wives might be more likely to purchase healthier broiler meat than non-working wives. This is potentially due to increased income, a working wife’s greater exposure to information about healthy eating habits, or a greater ability to prioritize healthier options during their work schedules. In contrast, households outside housing estates, often reliant on local vendors (vegetable/meat stalls/kiosks or mobile vendors in the housing area) for convenience, might have less access to guaranteed healthy options.

This study reveals a consistency between perception and purchasing behavior to an extent. Most households (72.9%, ) fall into the medium perception category regarding the health aspects of broiler meat. Similarly, households residing in housing estates have greater access to healthier broiler meat options than those in non-housing estates. However, the proportion of households in the Ys category is smaller than that of households whose level of perception is in the medium category.

This finding suggests a gap between perception and action, potentially due to income constraints. Households might prioritize convenience or affordability over perceived health benefits when purchasing power is limited. For some households, despite having a relatively high level of perception, limited purchasing power may lead them to purchase broiler meat from locations that do not guarantee health standards. This action could also involve reducing the volume purchased, slightly lowering their preference for the health level of broiler meat within their tolerance limits or a combination of both.

The findings of this study indicate that as household incomes and consumer knowledge regarding broiler meat health attributes increase, particularly among housewives, the demand for healthier broiler meat will continue to rise. This presents an opportunity to capitalize on supply chain performance improvements through enhanced broiler harvesting and post-harvest handling practices, as well as improved hygiene standards at the most commonly accessed purchasing locations.

Conclusion

This study revealed that most households fell within the medium perception category regarding healthy broiler meat. Interestingly, the findings suggest that spouses/wives play a crucial role in shaping household perceptions. Their experience buying healthy broiler meat positively influences these perceptions.

Based on these findings, we recommend a two-pronged approach: consumer education and improved market access. Awareness programs targeting healthy broiler meat consumption, mainly aimed at women, could be a valuable strategy. These programs could be developed and implemented by the government and private sectors. On the other hand, increasing the availability of healthy broiler meat options near residential areas would likely provide households with a greater chance of purchasing them. This could involve encouraging more retailers to offer healthy broiler meat or exploring alternative distribution channels within these areas.

While income level was not directly linked to perception, higher-income households were more likely to purchase healthy broiler meat. In anticipation of rising consumer income, ensuring a sufficient supply of healthy broiler meat is essential. This necessitates increased production and distribution of healthy broiler meat by producers and traders, overseen by relevant government regulations.

Limitations of the study

While this study offers valuable insights into consumer perceptions of healthy broiler meat, it is important to acknowledge some limitations. The study employed a cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single point in time. This design limits our ability to establish causal relationships between factors influencing consumer perception and how those perceptions change over time. In addition, the study focused on three aspects (freshness, cleanliness and safety) to represent the latent variable ‘Healthy’. Other factors consumers might consider when evaluating the healthiness of broiler meat (eg growth hormones, antibiotics) were not explored. Moreover, the study only included households with spouses, potentially excluding a segment of the population. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to the entire population.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects. All experimental procedures were approved by the National Research and Innovation Agency of the Republic of Indonesia Ethics Committee with ref number 489/KE.01/SK/07/2023 on 12 July 2023.

Consent form

The respondents were informed in writing about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, the confidentiality of the data and their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Author contributions

Ening Ariningsih, Mewa Ariani, Nyak Ilham, Eni Siti Rohaeni, Sri Hastuti Suhartini and Achsanah Hidayatina contributed to the conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. Sumaryanto Sumaryanto and Adang Agustian contributed to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. Suharyon Suharyon, Dwi Priyanto, Dedi Sugandi, Thomas Agoes Soetiarso, Gontom Citoro Kifli, Mat Syukur and Handewi Purwati Saliem contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data, the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content, and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Cogent 243993179 revised clean copy.docx

Download MS Word (336 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our gratitude to all the participants in this study, including the respondents, enumerators, government officers at the municipality, subdistrict, and village levels, and other relevant stakeholders. Additionally, they highly appreciate the contributions, valuable comments and feedback provided by journal editors and anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon request via the corresponding email address.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ening Ariningsih

Ening Ariningsih is a Senior Researcher at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. She holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from the University of the Philippines Los Baños, Los Baños, the Philippines. Her research interests include food security, consumer behavior, agricultural development policy, sustainable agricultural development, agribusiness, and integrated pest management.

Sumaryanto Sumaryanto

Sumaryanto is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. His research interests include econometric modeling, rural dynamics, food systems, climate change, and its implication on irrigation management, agribusiness, and agricultural development policy.

Mewa Ariani

Mewa Ariani is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. She holds an MS from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. Her research interests include agricultural socioeconomics and food security, especially food consumption behavior, sustainable food consumption, food diversification, and food loss and waste.

Nyak Ilham

Nyak Ilham is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. His research focuses on socioeconomic and agricultural policy, especially livestock and animal health economics. He has 11 years of experience working in livestock and forage breeding centers and 30 years of experience as a researcher across several domestic and foreign agencies.

Eni Siti Rohaeni

Eni Siti Rohaeni is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Animal Husbandry, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. Previously, she worked at the Agricultural Research and Development Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Indonesia. She holds a PhD in Agricultural Sciences in the field of Animal Husbandry. Her research interests include livestock production, farming systems, and sustainable agricultural development.

Adang Agustian

Adang Agustian is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. Previously, he had worked at the Indonesian Center for Agriculture and Socio-Economic Policy, Ministry of Agriculture, Indonesia. His research interests include agricultural economics, policies for promoting production efficiency and supply chains in the broiler industry, fertilizer subsidy policies for the agriculture sector, policies and strategies to increase the use of new superior varieties of rice seeds (VUB), and food security policy in Indonesia.

Sri Hastuti Suhartini

Sri Hastuti Suhartini is a Senior Researcher at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. She holds an MS in Agricultural Economics from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. Her research interests include agricultural economics and food security, especially food consumption behavior, sustainable food consumption, and food diversification.

Achsanah Hidayatina

Achsanah Hidayatina is a Junior Researcher at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. She holds an MS in Economics from the University of Otago, New Zealand. Her research interests include behavioral economics, circular economics, fisheries economics, regional economic issues, and empirical modeling using cross-sectional and panel data.

Suharyon Suharyon

Suharyon is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a BS in Farming Systems from Andalas University, Padang, Indonesia. His research focuses on farming systems for food crops, horticulture, and plantations.

Dwi Priyanto

Dwi Priyanto is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds an MS in Agricultural Economics from IPB University, Bogor Indonesia. His research focuses on farming systems, marketing, and agricultural sociology.

Dedi Sugandi

Dedi Sugandi is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Social Economics from Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia. His research focuses on agricultural social economics, agribusiness management, agricultural and livestock business systems, and livestock business management.

Thomas Agoes Soetiarso

Thomas Agoes Sutiarso is a Senior Researcher at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds an MS in Agricultural and Rural Development Communication from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. His research focuses on farming systems, agribusiness management, and circular economics.

Gontom Citoro Kifli

Gontom Citoro Kifli is a Junior Researcher at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Development Communication at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. His research focuses on farming systems, agribusiness, and circular economics.

Mat Syukur

Mat Syukur is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Cooperatives, Corporations and Community Economy, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. He holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia. His research focuses on agricultural socioeconomic policy, especially on agricultural financing and microfinance institutional development.

Handewi Purwati Saliem

Handewi Purwati Saliem is a Research Professor at the Research Center for Behavioral and Circular Economics, National Research and Innovation Agency, Indonesia. She holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from IPB University. Her research interests include agriculture, food, and nutrition policy; agribusiness and value chain; and gender lenses on agricultural development.

References

- Akbar, S., & Bakar, A. H. A. (2011). Factors affecting the consumer’s decision on purchasing power. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 2(3), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v2i3.229

- Ariani, M., Suryana, A., Suhartini, S. H., & Saliem, H. P. (2018). Keragaan konsumsi pangan hewani berdasarkan wilayah dan pendapatan di tingkat rumah tangga. Analisis Kebijakan Pertanian (Performance of animal food consumption based on region and income at household level), 16(2), 147–163. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330476854_Keragaan_Konsumsi_Pangan_Hewani_Berdasarkan_Wilayah_dan_Pendapatan_di_Tingkat_Rumah_Tangga https://doi.org/10.21082/akp.v16n2.2018.147-163

- Ariningsih, E., Ariani, M., Ilham, N., Rohaeni, E. S., Suhartini, S. H., Agustian, A., Hidayatina, A. S., & Suandy, I. (2023). Tinjauan kritis keamanan dan kehalalan daging ayam broiler di Indonesia (Critical review of safety and halalness of broiler chicken meat in Indonesia). Forum Penelitian Agro Ekonomi, 42(2), 97–117. https://fae.perhepi.org/index.php/FAE/article/view/37

- Boada, M., Boada, M., & Morocho, F. (2023). Perception and preferences of consumers in the retail sector: A case study in the City of Loja-Ecuador. Open Journal of Business and Management, 11(03), 1340–1358. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2023.113074

- Boateng, A. O., Bannor, R. K., Bold, E., & Helena, O.-K. (2023). A systematic review of the supply of agriproducts to supermarkets in emerging markets of Africa and Asia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(1), 2247697. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2247697

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia. (2023). Consumption expenditure of population of Indonesia based on the March 2023 SUSENAS. BPS-Statistics Indonesia. https://www.bps.go.id/en/publication/2023/10/20/40a8ad9c5478055fca31e2ca/pengeluaran-untuk-konsumsi-penduduk-indonesia–maret-2023.html

- Cheng, L., Jiang, S., Zhang, S., You, H., Zhang, J., Zhou, Z., Xiao, Y., Liu, X., Du, Y., Li, J., Wang, X., Xin, Y., Zheng, Y., & Shang, K. (2016). Consumers’ behaviors and concerns on fresh vegetable purchase and safety in Beijing urban areas, China. Food Control, 63, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.11.024

- Devatkal, S. K., Naveena, B. M., & Kotaiah, T. (2019). Quality, composition, and consumer evaluation of meat from slow-growing broilers relative to commercial broilers. Poultry Science, 98(11), 6177–6186. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez344

- Fauzi, N. A Wijaya. (2021). Faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi perilaku konsumen dalam pembelian daging ayam broiler di Pasar Celancang (Factors affecting consumer behavior in purchasing broiler chicken meat at Celancang Market). Jurnal Agrijati, 34(1), 69–72. https://jurnal.ugj.ac.id/index.php/agrijati/article/view/4848

- Franz, H. W., & Sarcina, R. (Eds.). (2009). Basic concepts of perception and communication. In Building leadership in project and network management (pp. 25–29). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-93956-6_5

- Ha, T. M., Shakur, S., & Do, K. H. P. (2021). Food risk in consumers’ eye and their consumption responses: Evidence from Hanoi survey. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies, 28(2), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABES-12-2019-0126

- Ibrahim, S. S. (2022). Livelihood transition and economic well-being in remote areas under the threat of cattle rustling in Nigeria. GeoJournal, 88(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10583-x

- Indrawan, D., Christy, A., & Hogeveen, H. (2021). Improving poultry meat and sales channels to address food safety concerns: Consumers’ preferences on poultry meat attributes. British Food Journal, 123(13), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2021-0362

- Ismanto, A., Julianda., & T., Mursidah. (2018). Analisis sikap dan kepuasan konsumen terhadap atribut produk karkas ayam pedaging segar di pasar tradisional Kota Samarinda (Analysis of consumer attitudes and satisfaction towards fresh broiler chicken carcass product attributes in traditional markets of Samarinda City). Jurnal Ilmu Peternakan Dan Veteriner Tropis, 8(2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.30862/jipvet.v8i2.34

- Joreskog, K. G., & Goldberger, A. S. (1975). Estimation of a model with multiple indicators and multiple causes of a single latent variable. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 70(351), 631–639. https://doi.org/10.2307/2285946

- Katiyo, W., Coorey, R., Buys, E. M., & de Kock, H. L. (2020). Consumers’ perceptions of intrinsic and extrinsic attributes as indicators of safety and quality of chicken meat: Actionable information for public health authorities and the chicken industry. Journal of Food Science, 85(6), 1845–1855. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15125

- Kendall, H., Kuznesof, S., Dean, M., Chan, M. Y., Clark, B., Home, R., Stolz, H., Zhong, Q., Liu, C., Brereton, P., & Frewer, L. (2019). Chinese consumer’s attitudes, perceptions and behavioural responses towards food fraud. Food Control, 95, 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.08.006

- Kitano, S., & Yamamoto, N. (2020). The role of consumer knowledge, experience, and heterogeneity in fish consumption: Policy lessons from Japan. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 56(March), 102151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102151

- Lestari, T. R. P. (2020). Penyelenggaraan keamanan pangan sebagai salah satu upaya perlindungan hak masyarakat sebagai konsumen (Food safety handling as one of the community protection efforts as a consumer). Aspirasi: Jurnal Masalah-Masalah Sosial, 11(1), 57–72. https://jurnal.dpr.go.id/index.php/aspirasi/article/view/1523 https://doi.org/10.46807/aspirasi.v11i1.1523

- Liguori, J., Trübswasser, U., Pradeilles, R., Le Port, A., Landais, E., Talsma, E. F., Lundy, M., Béné, C., Bricas, N., Laar, A., Amiot, M. J., Brouwer, I. D., & Holdsworth, M. (2022). How do food safety concerns affect consumer behaviors and diets in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Global Food Security, 32, 100606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100606

- Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata (3rd ed.). Stata Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23799944_Regression_Models_for_Categorical_and_Dependent_Variables_Using_STATA

- Lubna,., & Handayani, D. (2019). Working women and household expenditures on food away from home in Indonesia. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 27(3), 1573–1592. http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/resources/files/Pertanika PAPERS/JSSH Vol. 27 (3) Sep. 2019/12 JSSH(S)-1088-2019.pdf

- Maitiniyazi, S., & Canavari, M. (2021). Understanding Chinese consumers’ safety perceptions of dairy products: A qualitative study. British Food Journal, 123(5), 1837–1852. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2019-0252

- Mayulu, H., Rahman, A., & Yusuf, R. (2019). Consumer preference of broiler meat attributes in traditional markets. Hasanuddin Journal of Animal Science (HAJAS), 1(2), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.20956/hajas.v1i2.9877

- McLeod, E., Jensen, K. L., DeLong, K. L., & Griffith, A. (2019). A multiple indicators, multiple causes analysis of farmers’ information use. Journal of Extension, 57(3), 20. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.57.03.20

- Mensah, N. O., Owusu-Sekyere, E., & Adjei, C. (2023). Revisiting preferences for agricultural insurance policies: Insights from cashew crop insurance development in Ghana. Food Policy, 118(June), 102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2023.102496

- Mišík, M. (2015). The influence of perception on the preferences of the new member states of the European Union: The case of energy policy. Comparative European Politics, 13(2), 198–221. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2013.9

- Mortimer, G., & Clarke, P. (2011). Supermarket consumers and gender differences relating to their perceived importance levels of store characteristics. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(6), 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2011.08.007

- Mueller, A. J., Maynard, C. J., Jackson, A. R., Mauromoustakos, A., Kidd, M. T., Rochell, S. J., Caldas-Cueva, J. P., Sun, X., Giampietro-Ganeco, A., & Owens, C. M. (2023). Assessment of meat quality attributes of four commercial broiler strains processed at various market weights. Poultry Science, 102(5), 102571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.102571

- Nalindah, V., Chan, A., Tresna, P. W., & Barkah, C. S. (2022). Effect of consumer perception on the purchase decision of children’s football clothing products. KINERJA, 26(1), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.24002/kinerja.v26i1.5263

- Neima, H., Sirwan, K., & Hameed, K. (2023). Consumer purchasing intention and behaviour toward chicken meat in Sulaymaniyah City: Empirical evidence from a field survey. Journal of Agribusiness and Rural Development, 68(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.17306/J.JARD.2023.01622

- Newson, R. S., van der Maas, R., Beijersbergen, A., Carlson, L., & Rosenbloom, C. (2015). International consumer insights into the desires and barriers of diners in choosing healthy restaurant meals. Food Quality and Preference, 43, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.02.016

- Nugraha, W. S., Yang, S. H., & Ujiie, K. (2021). The heterogeneity of consumer preferences for meat safety attributes in traditional markets. Foods, 10(3), 624. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10030624

- Pham, T. T. H., & Turner, S. (2020). ‘If I want safe food I have to grow it myself’: Patterns and motivations of urban agriculture in a small city in Vietnam’s northern borderlands. Land Use Policy, 96(March), 104681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104681

- Pradana, M., Huertas-García, R., & Marimon, F. (2020). Purchase intention of halal food products in Spain: The moderating effect of religious involvement. International Food Research Journal, 27(4), 735–744. http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my/27 (04) 2020/DONE - 16 - IFRJ20142.R1.pdf

- Priyambodo, D., Dewi, I., & Ayuningtyas, G. (2021). Preferensi konsumen terhadap daging ayam broiler di era new normal (Consumer preferences for broiler chicken meat in the new normal era). Jurnal Sains Terapan, 10(2), 83–97. https://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/jstsv/article/view/35677 https://doi.org/10.29244/jstsv.10.2.83-97

- Prokeinova, R. B., & Hanova, M. (2016). Modelling consumer’s behaviour of the meat consumption in Slovakia. Agricultural Economics (Zemědělská Ekonomika), 62(5), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.17221/33/2015-AGRICECON

- Putri, D. P. K., & Lestari, S. (2015). Pembagian peran dalam rumah tangga pada pasangan suami istri Jawa (Division of household roles in Javanese couples). Jurnal Penelitian Humaniora, 16(1), 72–85. http://journals.ums.ac.id/index.php/humaniora/article/view/1523

- Qiong, O. U. (2017). A brief introduction to perception. Studies in Literature and Language, 15(4), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.3968/10055

- Richards, T. J., & Jeffrey, S. R. (2000). Efficiency and economic performance: An application of the MIMIC model. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 25(1), 232–251. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40987058

- Rosa, T. S., Ferasyi, T. R., Razali, R., Budiman, H., Fachrurrazi, F., & Nurliana, N. (2018). The consideration of halalan, thayyiban and economic factor of consuming chicken meat in several markets of Aceh Besar district. Jurnal Medika Veterinaria, 12(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.21157/j.med.vet.v12i1.4089

- Setyanovina, S. S., Suryantini, A., & Masyhuri, M. (2021). Characteristics and preferences of chicken meat consumers before and during COVID-19 pandemic in Sleman Regency. Agro Ekonomi, 32(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.22146/ae.60713

- Simarmata, L., Osak, R. E. M., Endoh, E. K., & Oroh, F. N. (2019). Analisis preferensi konsumen dalam membeli daging broiler di pasar tradisional Kota Manado (Studi kasus “Pasar Pinasungkulan Karombasan”) (Analysis of consumer buying preferences in broiler meat at traditional market in Manado City (Case study of the “Pinasungkulan Karombasan market”)). ZOOTEC, 39(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.35792/zot.39.2.2019.24427

- Soon, J. M., Vanany, I., Abdul Wahab, I. R., Hamdan, R. H., & Jamaludin, M. H. (2021). Food safety and evaluation of intention to practice safe eating out measures during COVID-19: Cross sectional study in Indonesia and Malaysia. Food Control, 125, 107920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107920

- Statista. (2022). Poultry consumption per capita in Indonesia from 2017 to 2022, with estimates until 2029. https://www.statista.com/statistics/757796/indonesia-poultry-consumption-per-capita/

- Surni, Nendissa, D. R., Wahib, M. A., Astuti, M. H., Arimbawa, P., Miar, Kapa, M. M. J., & Elbaar, E. F. (2021). Socio-economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic: Empirical study on the supply of chicken meat in Indonesia. AIMS Agriculture and Food, 6(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.3934/agrfood.2021005

- Teixeira, A., & Rodrigues, S. (2021). Consumer perceptions towards healthier meat products. Current Opinion in Food Science, 38, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2020.12.004

- Tenda, H. P. U., Tumengkol, S. M., & Kawung, E. J. R. (2020). Peranan ibu rumah tangga dalam meningkatkan status sosial keluarga di Kelurahan Bahu Kecamatan Malalayang Kota Manado (The role of housewives in enhancing family social status in Kelurahan Bahu, Kecamatan Malalayang, Manado City). Jurnal Holistik, 13(2), 1–15. https://ejournal.unsrat.ac.id/v3/index.php/holistik/article/view/29323

- Utiah, M. P., Kalangi, J. K. J., & Oroh, F. N. S. (2021). Analisis perbedaan perilaku konsumen dalam pembelian daging ayam ras pada pasar tradisional dan modern di kota Manado (The role of housewives in enhancing family social status in Kelurahan Bahu, Kecamatan Malalayang, Manado City). ZOOTEC, 41(2), 479–488. https://doi.org/10.35792/zot.41.2.2021.36809

- Uzundumlu, A. S., & Dilli, M. (2023). Estimating chicken meat productions of leader countries for 2019-2025 years. Ciencia Rural, 53(2), e20210477. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20210477

- Wang, C., Liu, T., Zhu, Y., Wang, H., Wang, X., & Zhao, S. (2023). The influence of consumer perception on purchase intention: Evidence from cross-border E-commerce platforms. Heliyon, 9(11), e21617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21617

- Wertheim-Heck, S. C. O., Raneri, J. E., & Oosterveer, P. (2019). Food safety and nutrition for low-income urbanites: Exploring a social justice dilemma in consumption policy. Regional Environmental Change, 31(2), 397–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247819858019

- Wertheim-Heck, S. C. O., & Spaargaren, G. (2016). Shifting configurations of shopping practices and food safety dynamics in Hanoi, Vietnam: A historical analysis. Agriculture and Human Values, 33(3), 655–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9645-4

- Wertheim-Heck, S. C. O., Vellema, S., & Spaargaren, G. (2014). Constrained consumer practices and food safety concerns in Hanoi. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(4), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12093

- Wertheim-Heck, S. C. O., Vellema, S., & Spaargaren, G. (2015). Food safety and urban food markets in Vietnam: The need for flexible and customized retail modernization policies. Food Policy, 54, 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.05.002

- Yeboah, I., Asante, B. O., Prah, S., Boansi, D., Tham-Agyekum, E. K., Asante, I. S., & Aidoo, R. (2023). Perception and adoption of food safety practices (FSP) among beef sellers and consumers: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 9(2), 2287285. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2023.2287285

- Zauner, A., Koller, M., & Hatak, I. (2015). Customer perceived value—Conceptualization and avenues for future research. Cogent Psychology, 2(1), 1061782. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2015.1061782

- Zellner, A. (1970). Estimation of regression relationships containing unobservable independent variables. International Economic Review, 11(3), 441–454. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2525323 https://doi.org/10.2307/2525323

- Zorba, N. N. D., & Kaptan, M. (2011). Consumer food safety perceptions and practices in a Turkish community. Journal of Food Protection, 74(11), 1922–1929. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-126

Appendix A

Table A1. Questions related to indicators of freshness, cleanliness and safety of broiler meat purchased by respondents.