?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The Moringa stenopetala tree is a highly versatile plant with numerous applications. It serves as a reliable source of food, feed, and income for farming households in Ethiopia. A study conducted in the Southern region of Ethiopia aimed to evaluate the potential of the Moringa stenopetala as a livestock feed resource. The study examined various factors, including year-round availability, usage trends, farmers’ attitudes, and livestock preferences, through a survey of 379 households using diverse techniques. Results revealed that the abundance of Moringa stenopetala trees ranged from 1 to 100 trees per household. Most households (95.5%) supplied the edible parts of the tree to their livestock for sufficient amounts of quality protein. However, the study identified a lack of awareness regarding harvesting, conservation, and processing during ample yield of trees for dry and seasonal fluctuations, limiting the potential of the tree for farming households. The study found that in the Gofa and Gamo zones, 64.8% and 52.73% of households, respectively, supplied cattle with edible parts of Moringa stenopetala, while 56.69% of households in the Konso zone mainly provided for goats. Livestock preferences for tree parts differ, with the earliest leaves being the most popular choice. Providing Moringa stenopetala parts in fresh and dried forms was important in replacing feed quality and quantity gaps during dry seasons. In conclusion, promoting the planting of the Moringa stenopetala tree and raising awareness of its nutritional composition of edible parts could help further utilize this valuable resource in drought-prone areas.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Across the world, most of the livestock feed resources are natural pastures and crop residues which account the largest proportion and they have low feeding value, digestibility and intake. This makes farming community not well-adjusted the supply of feeds to meet their goals for large livestock stockpile. These shows gaps for high-quality concentrate and other optional feed diets to improvement production and productivity of livestock. As a result, calls for alternatively presented feed resources which are not considered as the main is important to replace the limited feed resource bases. So, using year-round rurally available proteins fodder is the best option for closing the current commercial diet gap in the country as a whole and in the study area in particular. Therefore, the study was conducted to assess Moringa stenopetala foliage as optional feed resources and examine farmers’ perceptions and utilization practices.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Moringa species are multi-purpose trees of economic importance; the genus Moringaceae is represented by 14 species, among those Moringa stenopetala is native to Ethiopia, Northern Kenya, and Eastern Somali. It is widely distributed in the Rift Valley of southern Ethiopia and used as vegetable food for human consumption and animal feed resources during dry period. Additionally, the trees have been also planted to provide shade, wind breaks, fence lines, and beneficial green manure in addition to fuel wood (Melesse et al., Citation2011). Moreover, Moringa stenopetala is a critical resource for pastoral and agropastoral communities in most southern part of the Ethiopia, ensuring food security and livelihoods during times of unpredictable weather conditions (Kassahun & Bender, Citation2020). It is a plant with strong potential for producing high amount of fodder in short period, coppicing capabilities, and ease of field cultivation, ability to withstand repeated pruning, and good regeneration (Raj et al., Citation2023). In addition, it grows in soil and climate that are less valuable to its growth, and also it may be possible to harvest vast quantities of high-quality fodder from it without the need for costly inputs (Horn et al., Citation2022).

Moringa stenopetala is a popular human food which is consumed alongside all traditional food and drinks. It can additionally be sold for earning financial resources (Duguma, Citation2020). In addition to its nutritional benefits for human consumption, Moringa stenopetala possesses therapeutic properties and is utilized to treat various illnesses (Kumssa et al., Citation2017). Thus, the tree is now believed to be containing a drug that treats a number of diseases including cancer, high blood pressure, diabetes, and cough, rheumatism, pneumonia in children’s (Seifu & Teketay, Citation2020). For that reason, the dried edible leaves of the Moringa tree are processed and sold for considerable prices across the country and worldwide. It can be consumed early in the morning in the forms of tea and by means of porridge in a number of traditions.

Moringa stenopetala starts its evergreen pleasing at the arrivals of drought season however; its use for human being is not recommendable for the period of rainy season. This is due to its anti-nutritional factor make the plant unpalatable and disagreeable at the time. Its foliage leftover and uneatable parts are used by farming community as supplementary feed resources for livestock particularly for small ruminants (Duguma, Citation2020). It is in the group of high-yielding nutritious plants with every part having nourishment for livestock (Talha & Abbas, Citation2013). The chemical composition of Moringa stenopetala leaves contain 22.1–30.7% CP, 8.2–14.8% ash, 13.2–17.8% NDF and 11.2–16.5% ADF (Melesse et al., Citation2011; Melesse & Berihun, Citation2013, Melesse et al., Citation2015). In vitro organic matter digestibility ranged 72.0–86.2% and metabolizable energy value ranged 9.3–13.8 MJ/kg DM (Melesse et al., Citation2011). The leaf meal not only serve as protein sources but also provide some necessary vitamins, minerals and also oxycarotenoids which causes yellow colour of broiler skin, shank, and egg yolk (Etalem et al., Citation2013).

Despite the numerous advantages of Moringa stenopetala for human and livestock consumption, it is not extensively utilized in farming practices within the country (Guta, Citation2012). This lack of utilization is particularly concerning given the existing shortages of livestock feed in Ethiopia, which are causing significant losses in productivity (Shonde, Citation2017). Inadequate nutrition and insufficient feed supplies negatively impact livestock productivity worldwide (Welay et al., Citation2018; Duguma & Janssens, Citation2021). To address this issue, it is crucial to identify alternative feed resources that are high in quality and quantity (Tolera et al., Citation2012).

Globally, natural pastures and crop residues serve as the main sources of livestock feed, but their feeding value, digestibility, and intake levels remain significantly low (Mebrate & Tewodros, Citation2019). This makes farming community not well-adjusted to the supply of feeds to meet their goals for existing large livestock population and high yield of the livestock productivity. These limitations have prompted the need for exploring alternative feed sources that can improve the nutritional quality of livestock diets. Therefore, to enhance livestock productivity, farmers require access to higher-quality concentrate and other feed diets. However, various challenges, such as limited availability of commercially balanced feeds, difficulty obtaining seeds for environmentally friendly crops, and recurring droughts, hinder progress. Therefore, exploring alternative feed resources, such as Moringa stenopetala foliage, is critical to overcome these obstacles and improve livestock feed supply. This study aims to evaluate the potential of Moringa stenopetala foliage as an optional feed resource and examine farmers’ perceptions and utilization practices.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of study area

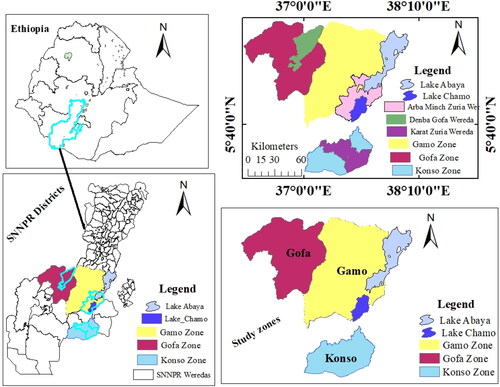

The study was conducted in three zones of Gamo, Gofa and Konso of the southern Ethiopia (). Astronomically, three zone lies between 5°34′16′′-7°20′58′′N, 6°15′-6°20′ N and 5°15′N latitude and; 36°22′13′′37°51′26′′E, 36°51′- 36°56′ E and 37°29′E Longitude, respectively. Gamo, Gofa and Konso zones are found in altitudes of 600–3300, 700–3200 and 501–2000 meters above sea level, respectively. Except, Gamo and Gofa zone practices mixed crop livestock farming practices whereas in Konso zone practices mixed and pastoralist way of life. Moringa stenopetala is cultivated densely planted in farm land, around their home by preparing terraces as soil conservations in Konso zone. In Gamo and Gofa area it is cultivated around home garden and in few on farm lands.

2.2. Sampling procedures and sample size

Multi-stage sampling techniques were applied to identify study area (zones), districts, kebeles (lowest administrative unity in Ethiopia), and households (HHs). Thus, Gamo, Gofa, and Konso zones were selected purposively based widespread cultivation of Moringa stenopetala in southern Ethiopia. Using reconnaissance survey, three districts and nine kebeles (three per districts) were selected purposively. Among the selected districts and kebeles a total of 124 HHs from Gamo, 125 HHs from Gofa and 130 from Konso were considered for the study. Totally, 379 households were randomly selected from the list of exceedingly growers of Moringa stenopetala among all kebeles. The sample size was determined using probability proportional sampling technique (Cochran, Citation1977).

where;

no = desired sample size when study population is > 10,000;

n1 = finite population correction factors when study population size is < 10, 000;

Z = standard normal deviation value (1.96 for 95% confidence level);

P = 0.1 (proportion of population to be included in sample i.e. 10%);

q = is 1-P i.e. (0.9);

N = is total number of population and;

d = is degree of accuracy desired (0.05).

2.3. Data collections

2.3.1. Questionnaire survey

Data were collected using semi-structured questionnaires on feed resource for livestock production, seasonality of feed availability, types of non-conventional feedstuffs, feed shortage and coping strategies and use of Moringa stenopetala as optional animal feed. Moreover, data were collected on types, characteristics, density, and distribution of Moringa tree. Also, mutuality of farmers’ and favorite of Moringa stenopetala tree as livestock feed information’s was gathered.

2.3.2. Focus group discussion

For focus group discussion, 8–12 key and experienced Moringa stenopetala agronomy farmers were used from each selected kebeles. Issues discussed were on Moringa stenopetala species diversity, cultivation/hectare, experiences in use of edible parts for human consumption and livestock feed.

2.4. Morphometric and dry mater yield estimation

For data collection 15 Moringa stenopetala trees per kebele (1–5 years, 6–10 years, and ≥10 years) were chosen at random. Morphometric data were collected using measuring tape and calculated using the allometric equation. The diameters of the plants were calculated using the formula:-

where:

D is the diameter and;

C is the circumference of the plant.

Then, DM yield of fodder trees was estimated using Pet Mark’s (Citation1983) methods.

where:

W = leaf yield in kilograms of dry weight.

DT = Diameter of trunk (cm) at 1.2 meter height (for tree leaf biomass).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using statistical procedures for social science (SPSS, 2016 Vr. 25). Chi-square tests were used to ascertain variations among categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was used for quantitative data. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test was used when F-test declare significance (p < 0.05). Index was computed with the principle of weighted average using the following formula, index = (x/y)/{∑ {(X/y) a + (X/y) b +… (X/y) ith}} (Musa et al., Citation2006), where X = First rank*ith + Second rank*kth + … + six rank*b + seven ranks; Y = First rank + Second rank + ……. + ith rank.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Socio-economic characteristics of respondents

The research findings indicate that the vast majority (90.77%) of households who registered for Moringa stenopetala cultivation and production were male in the study area (). The average age of the households interviewed was 45.18 ± 0.6, and this varied significantly (p < 0.05) across the different study zones. The average family size was 7.08 ± 0.14 individuals per household, with a higher average family size (p < 0.05) in the Gamo zone as compared to the Konso zone. The Konso zone had a higher average number of family members aged five years old, followed by the Gamo and Gofa zones. Similarly, the Gofa and Konso zones had a higher average number of family members aged 5 to 15 than the Gamo zone. The Gamo zone had the highest average number of family members aged 15 to 45, followed by the Gofa and Konso zones. There was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in the average number of family members aged 46 and above across the study zones. It is worth noting that the average family size (7.08 ± 0.14 persons) in this study was slightly lower than the average family size (8.94 ± 0.17 persons) reported by Duguma and Janssens (Citation2021) in four districts around the Gilgel Gibe catchment of Jima zone in Southwest Ethiopia.

Table 1. Socio-economic characteristics of the respondents.

The results of the study indicate that 67.02% of the households interviewed were literate, while 32.98% were illiterate (p < 0.05, χ2 = 98.81) (). The Konso zone exhibited a higher proportion of illiterates compared to the Gamo and Gofa zones. Meanwhile, 28.23% of the interviewed households sent their children to junior secondary school, 12.93% to basic education, and 11.61% to high school (). Notably, the study results showed that the percentage of literacy was significantly higher than the percentage of illiteracy in the area. This high percentage (67.02%) of literacy could have positive implications for the implementation of agricultural practices and the adoption of new innovative technologies, which could ultimately lead to a better livelihood for the people. Interestingly, Duguma and Janssens (Citation2021) reported a high level of illiteracy, with 13.4% of respondents attending primary school in four districts around the Gilgel Gibe catchment of the Jima zone in Southwest Ethiopia.

Table 2. Level of education of the interviewed households.

3.2. Land use pattern of the respondent (ha)

The results of the current study indicate that households in the study area possessed an average landholding of 1.32 ± 0.06 hectares. This was found to be significantly higher in the Gamo zone as compared to the Gofa zone (). Furthermore, the Gamo and Konso zones exhibited higher average land allocation for crop production than the Gofa zone, while a significant difference in land allocation was observed among the study zones for improved forage production and forest cover. In addition, the Konso zone had an average private grazing land per household of 0.03 ± 0.0 hectares, which was found to be significantly higher than that of the Gamo zone. It is noteworthy that the average landholding per household for crop production in the study area was less than the figure of 1.95 ± 0.05 hectares reported by Duguma and Janssens (Citation2021) for the Jima zone of Southwest Ethiopia.

Table 3. Mean ± SE landholding (ha) and use patterns of the households.

3.3. Livestock holding (TLU) and their major use in the family

The survey results indicate that cattle were the predominant livestock species among the participants. In terms of average cattle ownership per household, the Gamo and Gofa zones had higher numbers compared to the Konso zones (). Furthermore, the study suggests that the average herd size per household was 4.30 ± 0.15, which was lower than the average of 6.8 ± 1.1 per respondent in the Jima zone of Southwest Ethiopia (Duguma & Janssens, Citation2021). Interestingly, the average number of sheep, goats, and poultry per household in the Konso zone was higher than that of the Gamo and Gofa zones (p < 0.05). In terms of equine ownership, the Gofa zone had the highest average number of equines per household, followed by the Gamo and Konso zones. The survey results highlight the importance of livestock keeping for draught power, breeding, milk and meat, and as a source of cash income, which is consistent with the existing literature (Duguma & Janssens, Citation2021).

Table 4. Livestock species and ownership (mean ± SE) of the households.

3.4. Livestock feed resources

The availability of natural feed resources varies significantly between wet and dry seasons in terms of quality, quantity of biomass, and species diversity. Additionally, communal rangelands are decreasing due to the expansion of farmland. During the wet season, natural pasture (69.9%), browse trees (45.9%), crop residues (43.8%), and stubble grazing (39.8%) are the most common feed resources. In contrast, the most commonly shared feed sources during the dry season are crop residues (81.8%), browse trees (63.9%), grass hay (53.8%), natural pasture (47.8%), and stubble grazing (45.9%). Non-traditional feeds, such as fruit and vegetable waste (mango, avocado), sweet potato roots and leaves, cassava root and leaves, banana leaves and pseudo-stems, enset leaves and pseudo-stems, sugarcane tops, maize and sorghum tillers, and sludge (Atela), were also identified as viable feed resources according to focus group discussions. Additionally, Duguma and Janssens (Citation2021) suggested that non-conventional feed resources have the potential as extra feeds during the dry season. The study found that 97.9% of households reported a shortage of feed resources across all study zones (χ2 = 4.029, p = 0.133) (). Thus, 60.9% of households forced to rely on crop residues during the critical feed shortage season from January to May. However, coping mechanisms varied across study zones (χ2 = 108.343, p < 0.05) ().

Table 5. Feed shortage and coping strategies.

It is interesting to note that the study found a significant lack of access to commercial diets for livestock in local markets, with 85.2% of households not having this option. However, in the Gamo and Konso zones, there was a higher usage of commercial feeds from markets and homemade mixed diets as additional feed, at 25.0% and 13.1% respectively. Poultry and dairy cows seemed to have the most accessible feed from the market, with concentrated feeds being the most popular. The study also found that supplementary feeding was low overall, at only 8.2% in the areas studied. It was also discovered that 96.6% of respondents did not purchase commercial diets for their goats and sheep, with limited access and lack of awareness being the main reasons cited. This information provides valuable insight into the challenges facing livestock farmers in the region and highlights the need for increased support and education in this area.

3.5. Moringa stenopetala cultivation trends

The Moringa stenopetala tree is a highly valuable asset in the Southern region of the country due to its versatility and economic importance. In fact, it is often compared to a milking cow in terms of its significance. However, participants in a focus group discussion expressed that its value surpasses that of a cow, as it provides a sustainable product. Farmers in the Konso zone have reported that the Moringa stenopetala tree serves as a source of staple food and helps them attain a higher standard of living. Families even refer to it as the ‘mother and dairy plant,’ as they rely on it for food and livelihood. During times of food scarcity, the Moringa stenopetala tree provides much-needed relief for households and helps them overcome poverty. According to a study by Shonde (Citation2017), the Moringa stenopetala tree is a multipurpose tool that increases wealth and serves as a survival tool to resist crop failure. Furthermore, having Moringa stenopetala trees is a significant factor in marriage negotiations in the Konso region, as the presence of these trees is a criterion for families of daughters to accept the relation. In the traditional customs of the Konso people, it is a prevalent practice for the family of the bride to conduct an inquiry regarding the presence of Moringa trees on the farmland owned by the prospective groom when evaluating a marriage proposal (Liyew & Daniel, Citation2015). This tradition illustrates how vital Moringa trees are to the Konso people, who have long understood the advantages of this plant and incorporated it into their social and economic activities. In addition, those without Moringa tree are hated in the community. In line with this, Shonde (Citation2017) indicated that the Konso people assign a high social status to those who own a large number of Moringa trees. Moreover, Demeulenaere (Citation2001) indicated that, a person’s backyard Moringa tree count is positively correlated with their economic standing. The Moringa stenopetala is aged tree which has been passed down through generations via gifts. Also, it has different names in accordance with native calls as ‘Halako’ in the Gamo and Gofa, ‘Talahe’ in the Zeyse, ‘Shelaqta’ in the Konso, and ‘Shiferaw’ in Amharic languages. Per study report, three different planting methods practiced for growing Moringa stenopetala trees: fruits, seedlings, and tree cutting and planting which was similarly reported by Kumssa et al. (Citation2017) for Moringa oleifera in Northern Kenya.

3.6. Purposes of planting Moringa stenopetala

Moringa stenopetala is a highly useful plant that can serve multiple purposes in agriculture, including its ability to serve as a source of food, income, and feed value (Kumssa et al., Citation2017). It can be used for alley cropping, fertilizer production, honey extraction, live fencing, medicinal purposes, and disease prevention. Similarly, Yisehak et al. (Citation2011) also stated different advantages of planting as alley cropping, domestic cleaning agent, dye, nitrogen-rich fertilizer, gum, honey purifier and production, live fencing, medicine, ornamental, plant disease prevention, pulp, rope-making, tanning hides, and pollination control. Additionally, it can even be utilized to hasten the ripening process of fruits like bananas and mangoes. This makes the plant an extremely valuable asset for farmers seeking sustainable and profitable agricultural practices ().

Table 6. Purposes of planting Moringa stenopetala.

3.7. Types of Moringa stenopetala

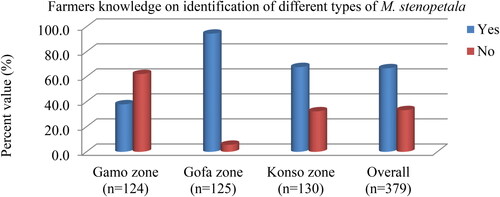

The results of the study revealed that a majority of farmers surveyed, 66.8%, were aware of the varieties of Moringa stenopetala in the study area (). Per study, two types of Moringa stenopetala were identified by farmers, namely Argole/Macha Halako in the Gofa or Shelaqta’a ati in the Konso and Adde Halako in the Gofa or Shelaqta’a bora in the Konso zones, respectively (). The former type is known for its sweet and delicious flavor when consumed as a vegetable. It possesses broad leaves and ripens quickly. In contrast, the latter type is bitter when consumed as a vegetable and has thin leaves that do not ripen quickly. Farmers in the Gofa and Konso zones demonstrated greater experience in identifying Moringa stenopetala varieties compared to those in the Gamo zone. The study also found that sweet and bitter varieties can be distinguished by pressing the leaves with a hand on the market. Sweet leaves turned white when squeezed, while bitter leaves turned black. Most growers supply unripe/bitter leaves for livestock and in the market. These findings are consistent with Seifu (Citation2015) report that different ecotypes and varieties of Moringa stenopetala can be found in Ethiopia.

3.8. Availability and harvesting of Moringa stenopetala

Based on the findings presented in , Moringa stenopetala production can be achieved in both dry and wet seasons, as noted by Abay et al. (Citation2016). Interestingly, Moringa stenopetala cultivation is a year-round event. The study zones differ significantly (χ2 = 89.61, p < 0.05) in terms of biomass/yield production, with varying levels of availability throughout the seasons (). For example, during the wet season, 100% and 66.9% of households (HHs) in the Gamo and Konso zones, respectively, reported high foliage availability. Conversely, during the dry season, 99.2% of HHs in the Gofa zone reported higher availability. Foliage collection practices also varied among study zones, with 54.62% of HHs reporting daily collection for home use (χ2 = 48.24, p < 0.05) (). However, Abay et al. (Citation2016) found that a single tree could yield an average of 3–4 fresh leaf harvests per year. Similarly, Eshete et al. (Citation2022) observed that, the biomass productivity of a Moringa stenopetala can be enhanced by harvesting it up to three times a year.

Table 7. Availability, yield production, and harvesting of Moringa stenopetala.

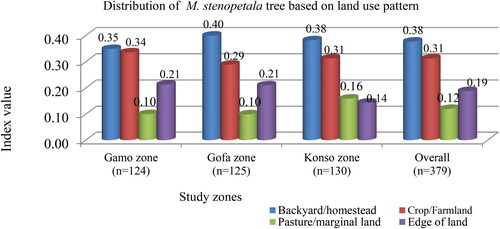

3.9. Distribution and management of Moringa stenopetala per land use patterns

According to the study, Moringa stenopetala trees were most commonly found in homesteads (ranked first), followed by farmland (ranked second), and then the edge of land (ranked third) and pasture or marginal land (ranked fourth). However, the Konso region stood out as having a higher distribution of trees in pasture lands or areas bordering farmland and the edge of the land, ranking third and fourth, respectively (). It could be due to the planting practices of the farmers in the valley region. Jiru et al. (Citation2006) found that Moringa stenopetala is extensively cultivated in the Konso area in home gardens to provide food for densely populated communities. However, Schneemann (Citation2011) noted that Moringa trees are mainly grown in home gardens in the Arba Minch area.

The number of plants per household varied between 1 and 100 trees, surpassing the 1 to 40 trees previously reported in the Tigray region of Northern Ethiopia by Abay et al. (Citation2016). On average, households possessed 18.46 ± 0.84 trees, four times greater than the average reported by Abay et al. (Citation2016). The number of plants per household in the Gamo and Gofa zones was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in the Konso zone. It might be due to high population density (Jiru et al., Citation2006) and smallholding of land (homestead) per HHs in the Konso zone. Based on maturity, about 3.3 ± 0.21 is categorized under five years, while 4.84 ± 0.28 is under age between 6 and 10 years, and the remaining 10.25 ± 0.53 accounted for above 10 (ten) years among total cultivating trees per HHs (). Farmers in the Gamo and Gofa zones possessed significantly (p < 0.05) more mature trees over ten years old than those in the Konso zone. Therefore, the presence of such enormous trees in the area helps to have a constant source of food and fodder for humans and animals, respectively.

Table 8. Average number of Moringa stenopetala trees per household in study area.

3.10. Fodder yield of Moringa stenopetala

In , the fodder yields of Moringa stenopetala are displayed according to the maturity order or age of trees in the study area. In general, the biomass yield of fodder increases as trees mature or age, and this variation is statistically significant (p < 0.05) across the study zones. The variability in biomass yield of fodder, based on the maturity order or age of trees, could potentially be attributed to the increase in the number of branches produced per plant. In congruence with the present study, Eshete et al. (Citation2022) have documented that the biomass productivity of Moringa stenopetala displays an ascending trend across the first, second, and third harvests at individual tree levels, which correlates positively with the tree’s increasing age or maturity level.

Table 9. Mean (±SEM) leaf yields (kg DM/tree) of Moringa stenopetala at 1.2 meter height.

The differences in planting techniques for Moringa stenopetala in the Gofa zone, where stems are used instead of seeds, may have played a role in this variation. Conversely, farmers in the Gamo and Konso zones used seeds for planting.

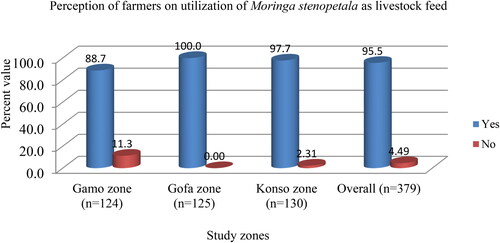

3.11. Perception of farmers on supplementation of Moringa stenopetala as livestock feed

From the data shown in , it can be inferred that 95.5% of households use the edible components of the Moringa stenopetala plant to feed their livestock. However, the study done by Reta (Citation2016) shows that in some Gofa areas, Moringa grower farmers do not place a strong priority on using Moringa stenopetala as feed for livestock. Similarly, Abay et al. (Citation2016) research found that the advantages of using Moringa leaves and pods as a feed source are minor in comparison to other contributions. Despite this, there have been no reported problems with using the edible parts of the tree Moringa stenopetala plant for livestock feed. However, it is important to note that the main constraints to customizing Moringa stenopetala as livestock feed are the lack of awareness, reliable information on nutritional and medicinal values, and low technological advancements in processing. Additionally, Kelemu and Alemu (Citation2013) have observed that poor mass production may arise from manual leaf harvesting of Moringa in rural areas, which is not supported by advanced equipment. As a result, there is a shortage in the supply of Moringa stenopetala as a substitute for commercial concentrate feed in the area. These recommends the need of increasing awareness and training of farmers on efficient harvesting of the Moringa stenopetala in order to take full advantage on the plant’s therapeutic and nutritional qualities.

3.12. Utilization practices and favored part of Moringa stenopetala for livestock

The study found significant variations (χ2 = 48.11, p < 0.05) in the types of edible parts of Moringa stenopetala offered to livestock species among the study area (). The Gofa and Gamo zones had the highest percentage of households (HHs) supplying cattle with edible parts of Moringa stenopetala at 64.8% and 52.73%, respectively. However, in the Konso zone, 56.69% of HHs mainly provided for goats. Totally, 48.07% and 44.75% of HHs supplied edible parts for cattle and goats, respectively. This difference could happen due to the frequency of foliage harvesting. Moreover, in the Konso, Moringa stenopetala foliage is harvested daily for its vegetable value and branches supplied to livestock, while in the Gofa and Gamo, the foliage is left unpicked for a long time while the edible parts supplied (χ2 = 68.72, p < 0.05). The study also found that 93.6% and 76.4% of HHs in the Gofa and Gamo zones primarily supply leaves for their livestock, while 52.76% of HHs received twigs in the Konso zone. Consistently, Abay et al. (Citation2016) also revealed that Moringa stenopetala leaves and pods are a great source of fodder for livestock, including cattle, sheep, pigs, and goats.

Table 10. Utilization practices and favored parts of Moringa stenopetala (MS) as livestock feed.

The focus group discussion participants reported that livestock prefer leaves (1st), followed by twigs (2nd), flower buds (3rd), and pods (4th), with index values of 0.29, 0.27, 0.23, and 0.21, respectively. Observations in the field showed that sheep and goats prefer Moringa stenopetala foliage to other browse trees. Accordingly, 98.1% of HHs supplied their livestock with favored parts of the tree in fresh form (). The results underline how crucial it is to take notice of the variations in edible portions of Moringa stenopetala provided to animals among study zones. Thus, planning measures to increase livestock productivity and food security in the area can be informed by an understanding of these variances.

3.13. Indigenous knowledge of farmers on medicinal value of Moringa stenopetala

Historically, Moringa stenopetala has been utilized as a medicinal remedy for a variety of ailments, as indicated in . Its leaves and other plant parts are highly valued to treat illnesses like high blood pressure, arthritis, diabetes, wounds, eye infections, malaria, bloating, and stomach cramps (Singh & Chaturvedi, Citation2021). Moreover, Kumssa et al. (Citation2017) have documented the significant medicinal properties of the Moringa stenopetala plant parts in the treatment of diverse illnesses. Correspondingly, the study by Jiru et al. (Citation2006), ECHO (Citation2007), Mekete (Citation2008), Yisehak et al. (Citation2011), and Melesse et al. (Citation2011) demonstrate that it is effective in ejecting trapped placentas. Additionally, smoking Moringa leaves and body parts had been utilized for repelling snakes out of homes.

Table 11. Indigenous knowledge of farmers on medicinal value of Moringa stenopetala (MS).

4. Conclusions

Per study, Moringa stenopetala is a valuable and multipurpose tree that serves as an indicator of wealth, provides food, income, feed, and medicinal value. The study shows that, two commonly recognized Moringa stenopetala tree varieties, which have bitter and sweet tastes, are found in farming areas. Even though, the entire tree is utilized as animal feed, there are limitations due to poor improvements in technology and a lack of awareness about the nutritive and medicinal worth of the tree. The majority of farmers are ignorant of the most effective methods to use these protein-rich fodder trees as partial replacements in animal diets. Thus, to minimize existing gap in demand and supply of the commercial supplementary feed resources, awareness creations and technical trainings are required to fully utilize the year-round locally available protein rich Moringa stenopetala fodder trees. Additionally, encouraging plantations of the Moringa stenopetala fodder trees is conclusive in place of expensive agro-industrial supplies to easily boost livestock production. Further, experimental study is recommended on entire tree parts and varieties to determine their optimal nutritional value.

Consent to participate

Informal verbal consent was obtained from all of the participants included in interview and FGD.

Acknowledgements

The authors say the data collectors and participating farmers deserve recognition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Guyo Demisse

Guyo Demisse is lecturer and PhD candidate in Animal Production at Arba Minch University, Ethiopia. He is currently conducted his PhD study on Moringa stenopetala as livestock feed in Southern Ethiopia: farmers’ perception, constraints to adoption and effects of long-term supplementation on livestock performance.

Yisehak Kechero

Yisehak Kechero (PhD) is a Professor, field of specialization is animal nutrition. He was a professor of animal nutrition and feeding in Arba Minch University, Department of Animal sciences. His research interest is the areas of animal feeding.

Nebiyu Yemane

Dr. Nebiyu Yemane (PhD) specialized in animal production. He is lecturer and researcher at Arba Minch University, Department of Animal sciences.

Yoseph Mekasha

Dr. Yoseph Mekasha Gebere obtained his PhD in Animal Sciences from the Swedish University of Agricultural Science.

References

- Abay, A., Birhane, E., Taddesse, T., & Hadgu, M. K. (2016). Moringa stenopetala tree species improved selected socio-economic benefits in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 4(2), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.4314/star.v4i2.10

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley and Sons.

- Demeulenaere, E. (2001). Moringa stenopetala, a subsistence resource in the Konso district. In Proceedings of the International Workshop Development Potential for Moringa Products. October 29-November 2, 2001 (pp. 2–29). DarEs-Salaam.

- Duguma, B., & Janssens, G. P. J. (2021). Assessment of livestock feed resources and coping strategies with dry season feed scarcity in mixed crop–livestock farming systems around the Gilgel Gibe Catchment, Southwest Ethiopia. Sustainability, 13(19), 10713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910713

- Duguma, H. T. (2020). Wild edible plant nutritional contribution and consumer perception in Ethiopia. International Journal of Food Science, 2020, 2958623. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2958623

- ECHO. (2007). ECHO Technical Note: The Moringa Tree. USA. Retrieved May 14, 2021, from www.echonet.org.

- Eshete, A., Yilma, Z., Gashaye, D., & Geremew, M. (2022). Effect of spacing on growth performance and leaf biomass yield of Moringa stenopetala tree plantations. Trees, Forests and People, 9, 100299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100299

- Etalem, T., Getachew, A., Mengistu, U., & Tadelle, D. (2013). Moringa oleifera leaf meal as an alternative protein feed ingredient in broiler ration. International Journal of Poultry Science, 12(5), 289–297.

- Guta, D. D. (2012). Assessment of biomass fuel resource potential and utilization in Ethiopia: sourcing strategies for renewable energies. International Journal of Renewable Energy Research, 2(1), 131–139.

- Horn, L., Shakela, N., Mutorwa, M. K., Naomab, E., & Kwaambwa, H. M. (2022). Moringa oleifera as a sustainable climate-smart solution to nutrition, disease prevention, and water treatment challenges: A review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 10, 100397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100397

- Jiru, D., Sonder, K., Alemayehu, L., Mekonen, Y., & Anjulo, A. (2006). Leaf yield and nutritive value of Moringa stenopetala and Moringa oleifera accessions: Its potential role in food security in constrained dry farming agroforestry system. In Moringa and other highly nutritious plant resources: Strategies, standards and markets for a better impact on nutrition in Africa (pp. 16–18). Ghana.

- Kassahun, T., & Bender, S. (2020). Food security in the face of climate change at Kafa Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia. Handbook of Climate Services, 2020, 463–479.

- Kelemu, K., & Alemu, D. (2013). Commercialization of Moringa production in Ethiopia: Establishing model value chains for Moringa in Ethiopia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316647971

- Kumssa, D. B., Joy, E. J. M., Young, S. D., Odee, D. W., Ander, E. L., Magare, C., Gitu, J., & Broadley, M. R. (2017). Challenges and opportunities for Moringa growers in Southern Ethiopia and Kenya. PloS One, 12(11), e0187651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187651

- Liyew, B., & Daniel, F. (2015). Socio-economic, cultural, food and medicinal significance of Moringa stenopetala (Bak.f) cuf.: A case of Konso Special Woreda, SNNPRs, Ethiopia. RJSSM: Volume: 05, Number: 7.

- Mebrate, G., & Tewodros, A. (2019). The application of biotechnology on livestock feed improvement. Archives in Biomedical Engineering & Biotechnology, 1(5), 522. https://doi.org/10.33552/ABEB.2019.01.000522

- Mekete, E. (2008). Moringa stenopetala seed cake powder: A potential for biogas Production and brewery waste water treatment through Coagulation [Msc thesis] Addis Ababa University.

- Melesse, A., & Berihun, K. (2013). Chemical and mineral compositions of pods of Moringa stenopetala and Moringa oleifera cultivated in the lowland of Gamogofa Zone. Journal of Environmental and Occupational Science, 2(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.5455/jeos.20130212090940

- Melesse, A., H/Meskel, D., Banerjee, S., Abebe, A., & Sisay, A. (2015). The effect of supplementing air-driedMoringa stenopetala leaf to natural grass hay on feed intake and growth performances of Arsi-Bale goats. Agriculture, 5(4), 1183–1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture5041183

- Melesse, A., Tiruneh, W., & Negesse, T. (2011). Effects of feeding Moringa stenopetala leaf meal on nutrient intake and growth performance of Rhode island red chicks under Tropical climate. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 14, 485–492.

- Musa, L., Peters, K., & Ahmed, A. (2006). On farm characterization of Butana and Kenana cattle breed production system in Sudan. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 18, 56–61.

- Pet Mark, M. V. (1983). Primary production, nutrient cycling and OM turnover of tree plantation after agricultural intercropping practices in north east Thailand [PhD Dissertation] (p. 228). University of Philadelphia.

- Raj, A. K., Raj, R. M., Kunhamu, T. K., Jamaludheen, V., & Chichaghare, A. R. (2023). Management of tree fodder banks for quality forage production and carbon sequestration in humid tropical cropping systems–An overview. The Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 93(1), 10–22. https://doi.org/10.56093/ijans.v93i1.120692

- Reta, A. (2016). Consumption pattern and indigenous processing practices of Moringa stenopetala (Bak.F.) Cuf.: A Case of Demba Gofa District SNNPR [M.Sc Thesis]. Arba Minch University.

- Schneemann, J. (2011). Moringa (stenopetala) production and use for water purification in Ethiopia. Fair and sustainable advisory service. The Netherlands.

- Seifu, E. (2015). Actual and potential applications of Moringa stenopetala, underutilized indigenous vegetable of Southern Ethiopia: A review. International Journal of Agricultural and Food Research, 3(4), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.24102/ijafr.v3i4.381

- Seifu, E., & Teketay, D. (2020). Introduction and expansion of Moringa oleifera Lam. in Botswana: Current status and potential for commercialization. South African Journal of Botany, 129, 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2020.01.020

- Shonde, Y. (2017). Livelihood contributions of Moringa tree based agroforestry practices in Konso District, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Resources Development and Management, 36, 1–9.

- Singh, A., & Chaturvedi, N. (2021). Medicinal value, herbal gold to combat malnutrition and health benefit of Moringa leaf and multipurpose uses of all parts-a review. Plant Archives, 21(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.51470/PLANTARCHIVES.2021.v21.no1.176

- Talha, E., & Abbas, F. (2013). The use of Moringa oleifera in poultry diets: Review Article. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, 37, 492–496. https://doi.org/10.3906/vet-1211-40

- Tolera, A., Getnet, A., Diriba, G., Lemma, G., & Alemayehu, M. (2012). Livestock and feed resources in Ethiopia: Challenges, opportunities and the need for transformation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Animal Feed Industry Association, p. 5–36. http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/2918

- Welay, G. M., Tedla, D. G., Teklu, G. G., Weldearegay, S. K., Shibeshi, M. B., Kidane, H. H., Gebrezgiabher, B. B., & Abraha, T. H. (2018). A preliminary survey of major diseases of ruminants and management practices in Western Tigray province; northern Ethiopia. BMC Veterinary Research, 14(1), 293. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1621-y

- Yisehak, K., Solomon, M., & Tadelle, M. (2011). Contribution of Moringa (Moringa stenopetala, Bac.), a highly nutritious vegetable tree, for food security in South Ethiopia: A review. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences, 4(5), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajaps.2011.477.488