Abstract

Entrepreneurship education (EE) is one of the fastest growing fields of education globally, yet the areas of “what” should be taught in these programmes and “how” to teach them have been mentioned by many researchers as ones that lack both consensus and devoted attention. The present paper aims to provide a detailed map of common and best practices in terms of curriculum content and methods of teaching entrepreneurship on the tertiary level, and to explore how they correlate with practices recommended by the entrepreneurial learning field of research, in order to contribute to extracting best practice. This paper uses a systematic literature review (SLR) to help review the literature in a transparent and unbiased way. The review is undertaken through six stages using NVivo computer software. In each stage, the literature on EE is screened and filtered to reduce the size and try to reach the more relevant and useful papers. This process end up with 129 articles divided between EE and entrepreneurship learning. The result of the reviewing process reveals that the curricula content and teaching methods vary depending on the programme’s objectives—from theoretical courses aiming to increase entrepreneurial awareness to practical-oriented ones that aim to produce graduates ready to start a business. Practical-oriented courses correlate with entrepreneurial learning suggestions for practices to engage students in acquiring entrepreneurial competencies. However, to better extract best practice, it would be useful if future research could explore what, exactly, it is that we mean when we use the term “entrepreneurial course” and link it to the entrepreneurship process. Also, it would be useful to explore what are the results of EE programmes in terms of the actual graduates who start or grow a business, and link the findings to the teaching process.

Public Interest Statement

Entrepreneurship education (EE) is one of the fastest growing fields of education globally, yet the areas of “what” should be taught in these programmes and “how” to teach them have been mentioned by many researchers as ones that lack both consensus and devoted attention. This article tries to provide the available information about the methods and curriculum contents of the entrepreneurship education. A systematic literature review is used as a method to handle this problem. By so doing, the paper helps researchers in this area to know the findings of the most important articles in the field of entrepreneurship education. It also helps the entrepreneurship’s instructors to develop their curricula and teaching methods.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, entrepreneurship education (EE) is one of the fastest growing fields of education globally (Solomon, Citation2007). This is an indication for the importance of entrepreneurship for the economy of any society. There is a tacit assumption that links between providing EE and promised economic growth, generating employment opportunity and enhancing economic development at large. This assumption was examined by many researchers and some evidence were found to support it (Dzisi, Citation2008; Ligthelm, Citation2007; Mojica, Gebremedhin, & Schaeffer, Citation2010; Pacheco, Dean, & Payne, Citation2010).

Moreover, there is a debate amongst academics and business people about whether entrepreneurship can be taught in the first place (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2013). Some perceive entrepreneurship as a talent with which one is born and cannot be taught; however, this can also be said of other professions, such as engineering or medicine, and nobody will dispute the need to teach students these subjects (Fayolle, Citation2013).

At the same time as this debate, there is an established recognition about the increasing demand for EE (Jones & Matlay, Citation2011). Hence, the discussion—as Fayolle (Citation2013) suggested—as an attempt to avoid stagnation, should move from whether EE can be taught or not to focus on the basic questions coming from education science: what, how, for whom, why and for which results is the EE programme designed (Jones & Matlay, Citation2011).

The movement of this discussion could help to further design EE programmes that are able to contribute to the challenge of codifying entrepreneurial skills like selling, managing people and product development into a teachable curriculum (Aronsson & Birch, Citation2004). Also, focusing on education science questions could contribute to the design of effective EE programmes that correlate with practices recommended by entrepreneurial learning (Jones, Citation2010), as well as being able to adapt to the resources and timetable constraints of Higher Education institutions (Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008).

This article will use Pittaway and Cope’s (Citation2007) simplification suggested for the complex nature of EE, where it could be understood as systematic in nature. This provides the ability to distinguish the factors of an EE programme into inputs of a system, educational processes, and outputs; where the educational process includes the programme’s objectives, audiences, assessments, contents, and methods of teaching (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2008).

However, this article will focus on the “what” and “how” as areas mentioned by many researchers as ones that lack devoted attention (Bennett, Citation2006; Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2008; Pittaway & Cope, Citation2007; Samwel Mwasalwiba, Citation2010; Solomon, Citation2007). This article aims to provide a detailed map of common and best practices in terms of curriculum content and methods of teaching entrepreneurship on the tertiary level, and correlate the findings with entrepreneurial learning suggestions for EE practices. The value of this research is to contribute to an area that lacks devoted attention—course content and method of teaching entrepreneurship (Solomon, Citation2007)—which needs further in-depth description in order to contribute to the efforts for extracting best EE programme practices (Jones & Matlay, Citation2011).

2. Methodology

As there is a vast amount of research on EE, it seems nearly impossible to undertake a comprehensive review of the literature. As it is very costly and not practical to review all of them, the second option is to adopt a narrative literature review, but it involves many disadvantages and has been subjected to many criticisms. Because of this, the present paper uses a systematic literature review (SLR) to help review the literature in a transparent and clear way. This method is characterised by transparency, clarity, equality and accessibility, unified and focused (Thorpe, Holt, Pittaway, & Macpherson, Citation2006). In addition, it provides an effective method for mapping out thematically the field of study and allows them to be viewed holistically. Moreover, it links the different researches together that have not been linked previously (Pittaway & Cope, Citation2007). Thus, it helps to avoid the pitfalls of a narrative literature review, which can sometimes be vulnerable to criticism that the choice of articles was biased, arbitrary or limited in scope (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006).

Normally, SLR is undertaken at different stages, it varies from one study to another depending on the research purpose. The present study review the literature within six stages, these are outlined in Table . While the vast majority of previous articles discussing EE provision used entrepreneurship and education journals to explore the topic of EE, in this study the SLR methodology aims to search a wider range of journals from different fields including entrepreneurship and education journals, as well as engineering, veterinary science, agriculture and Information technology.

Table 1. Stages of the SLR process

The search boundary includes journals included in the Association of Business Schools (ABS) journals and Journal Citation Report (JCR) 2013 in the time range between 2005 and 2014. Moreover, in order to look at current practices, we will explore the curricula content and teaching methods of the two top-ranked EE programmes—as ranked by the Princeton Review—websites, which are provided in accredited institutions.

The entrepreneurship journals were searched systematically using the phrases “entrepreneurship education curriculum”, “entrepreneurship education pedagogy” and “entrepreneurial learning”. The articles found were reviewed and downloaded into bibliographical software. Afterwards, the initial findings were further expanded via a number of systematic review stages. Finally, the articles were reviewed against the inclusion criteria, which are: “entrepreneurship education for entrepreneurs—as individuals not organisations”, “EE programme on tertiary level” and articles on “entrepreneurship education not business and enterprise education”.

The reason for excluding enterprise and business education is because there is a core difference between typical management and business education and EE: the former two focus more on how to manage a business, while the latter is about business entry and creation (Katz, Citation2003).

3. The review findings

The whole 129 articles were reviewed, and NVivo was used for the content coding and analysis (Pittaway & Cope, Citation2007). This article will divide the review into two parts: (1) “entrepreneurial learning”, to analyse the 32 articles discussing entrepreneurial learning, and whether entrepreneurs learn differently; and (2) “entrepreneurship education”, to analyse what the 97 EE articles indentified as common or best practice in terms of curricula content and teaching methods’ provision at the tertiary level. This analysis is detailed in the following two sections. The final section discusses the detailed findings and conclusions.

3.1. Entrepreneurial learning (EL)

Nowadays, there is an increasing interest in the entrepreneurial learning research field (Harmeling & Sarasvathy, Citation2013). Some studies argue that part of the increasing interest in EL is that the current entrepreneurship educational provision is supply-led and does not fully reflect a demand-led approach that values how entrepreneurs learn (Pittaway & Thorpe, Citation2012). As entrepreneurship courses were first provided in conventional business education (Kuratko, Citation2005), consequently, much early research focused on exploring the already provided programmes (McMullan & Vesper, Citation1987; Vesper & Gartner, Citation1997). Only later did the interest in exploring the learner side emerge that aimed to understand how real-life entrepreneurs learn and acquire entrepreneurial competencies (Morris, Webb, Fu, & Singhal, Citation2013).

The competencies, however, have also been gaining considerable attention in recent years across diverse fields (Sánchez, Citation2013). Generally, competency includes knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours needed to complete an activity successfully (Morris et al., Citation2013; Sánchez, Citation2013). Regarding entrepreneurial competencies, they include, amongst many others: opportunity recognition, opportunity assessment, risk management, creative problem solving, value creation and building, and using networks (Morris et al., Citation2013). Entrepreneurial learning focuses on exploring how entrepreneurs gain the previously mentioned entrepreneurial competencies (Cope, Citation2005). Many entrepreneurial learning articles have drawn on literature from relevant fields like individual learning and adult learning (Cope, Citation2005, Citation2011; Pittaway & Thorpe, Citation2012).

Furthermore, the discussion in EL is centred on the idea of gaining entrepreneurial competencies through experience that entrepreneurs gain from “learning by doing” (Cope & Watts, Citation2000), routinised activities (Reuber and Fischer, 1993 in Cope, Citation2005), contingencies, non-continuous events (Harmeling & Sarasvathy, Citation2013), failure (Minniti & Bygrave, Citation2001), and reflecting (Cope, Citation2005) from experience gained through these life events.

Also, the methods suggested by researchers drawing on how entrepreneurs and adults in general learn assume that a high proportion of active learning is important to enable problem solving, self-reliance and self-reflection (Klapper & Tegtmeier, Citation2010). The educational methods suggested by entrepreneurial learning literature are scenarios, role playing and real business experiences (Corbett, Citation2005), case studies’ discussions and business simulations (Chang & Rieple, Citation2013), live projects that combine traditional teaching with talks from business people Heinonen & Poikkijoki, Citation2006), peer assessment, primary data gathering and reflective accounts (Chang & Rieple, Citation2013).

The focus on studying entrepreneurs as the starting point for designing EE programmes is appreciated as it will contribute to providing learner-centred programmes that better engage students rather than teacher-centred ones (Jones, Citation2010). However, while many studies assert that entrepreneurs are different from non-entrepreneurs, there is no unified description of how they differ (Lee, Chang, & Lim, Citation2005). Also, many researchers refute the question of an entrepreneur as an individual who acts or learns differently, as Ramoglou (Citation2013, p. 433) states: “as there is nothing to be learned from dancers beside they dance, there is nothing unique to be found in individuals who just exercise entrepreneurial action”; hence, entrepreneurs actually learn similarly to how other adults do.

3.2. Entrepreneurship education (EE)

In the 1980s, much EE literature discussed the trend of the increasing number of EE programmes in universities (McMullan & Vesper, Citation1987). Over time, the focus moved towards the actual process and content of EE programmes (Vesper & Gartner, Citation1997). Moreover, more recent works take a rigorous look at course content (DeTienne & Chandler, Citation2004; Fiet, Citation2001; Honig, Citation2004; Shepherd, Citation2004). Each of these articles, with many other recent articles about entrepreneurial learning, are making a serious attempt to merge theory, practice and actual observation of what entrepreneurs do and how they learn (Harmeling & Sarasvathy, Citation2013).

The 97 articles on EE did originate from diverse geographical contexts, mostly in the UK and the USA, some others from European countries and Australia, and very few from Asia, Africa and Latin America. While it might raise doubt on the ability to extract common practice from different contexts, however, as Coviello and Jones (Citation2004) argue, the differences in EE practices originate from authors’ varied definitions of pivotal issues rather the context differences. Hence, while EE programmes might be affected by country-specific issues, the aims of these programmes are universal (Samwel Mwasalwiba, Citation2010), and this article will take advantage of this diversity to map out common and best practices, and try to categorise provision into generic themes.

Moreover, whilst many articles have studied EE provision at the undergraduate level, far fewer have focused on the postgraduate level, and very few on the MBA and PhD level. Furthermore, many articles discuss EE programme provision in various disciplines: mostly in management, business, entrepreneurship or enterprise degrees, many in engineering degrees, and fewer provided elective courses open to many disciplines including agriculture, veterinary science, pharmacy, science, information technology and biomedical diagnostics.

3.2.1. Common practice

In order to analyse the EE articles, NVivo was used to explore which curricula content and teaching methods were discussed in them. While there is a lack of uniformity vis à vis “what” is taught and “how”, causing the courses to vary widely (Bennett, Citation2006), the most discussed curricula content and teaching methods are shown in Table , where word frequency would give a general sense of the repetitiveness of the discussion of a subject (Bazeley & Richards, Citation2000).

Table 2. Content and teaching method word frequency in the EE articles, and the suggested entrepreneurship (E-ship) education themes

Also, as it is inevitable that the course content will depend on the course objective (Pardede & Lyons, Citation2012), in our grouping of different themes of EE provision, we will link the EE content and teaching methods with its proposed objectives.

The three generic themes of EE provision are: theoretical-oriented courses that teach (1) “about” entrepreneurship (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014) and aim to increase awareness about entrepreneurship, encourage students to choose entrepreneurship as a potential career choice (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2013) and consider self-employment (Klapper & Tegtmeier, Citation2010); and practical-oriented courses that teach (2) “for” entrepreneurship (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014) aims to encourage students and enhance their intentions to be entrepreneurs in future and (3) “through” entrepreneurship, which aim to graduate entrepreneurs (Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008), support new venture creation (Lundqvist & Williams Middleton, Citation2013) and develop entrepreneurial competencies (Bridge, Hegarty, & Porter, Citation2010).

3.2.1.1. Teaching “about” entrepreneurship programmes

The most frequently discussed content subject in the articles that discuss theoretical-oriented courses is the business plan (Honig, Citation2004). Also, generally we find the conventional management-related subjects such as marketing and financial management (Kuratko, Citation2005) are mentioned often, as well as small business management courses (Solomon, Citation2007).

Moreover, in this theme there is entrepreneurship theoretical content that includes: entrepreneurial traits; personality characteristics; economic success; how people think entrepreneurially and entrepreneurial awareness (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014). For this theme, teaching is mostly teacher-centred and the learner is passive, and the most used teaching methods are lectures, guest speakers and case studies—usually adopted from textbooks (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2008).

3.2.1.2. Teaching “for” entrepreneurship programmes

Curricula content for this theme takes skills-based approaches where it seeks to train students about the mechanisms of running a business (Bennett, Citation2006). The content of this theme aims to provide a portfolio of techniques to encourage entrepreneurship practice, including: generating ideas; team building; business planning; creativity; innovation; inspiration; opportunity recognition; selling; networking; unpredictable and contingent nature of entrepreneurship; adapting to change; and expecting and embracing failure (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2013; Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014).

Also, from Table , an increasing discussion is noticed about the concept of “learning by doing” and experiential teaching methods (Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2013). Some of the most discussed tools used in this theme were simulations (Honig, Citation2004); other discussed teaching methods ranged from self-directed activities, team teaching of academics and practitioners, mentoring and networking with entrepreneurs (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014).

For the teaching “for” entrepreneurship theme, in most cases students act, role play and pretend to be entrepreneurs rather than really being one, which is the core difference between this theme and the one discussed next, which is teaching “through” entrepreneurship (Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008). Also, one of the least-mentioned courses was sales and selling, which was discussed only in 16 out of 97 articles. However, this is not surprising, as Aronsson and Birch (Citation2004) observed that courses on sales are rarely offered in business schools.

3.2.1.3. Teaching “through” entrepreneurship programmes

Curricula content for this theme is similar to teaching “for entrepreneurship”; however, it suggests learning “with” and “through” real-life entrepreneurship, to enable students to experience “being” entrepreneurs rather than “pretending” to be ones (Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008) and to have a real taste of market forces (Dabbagh & Menascé, Citation2006). These courses focus on pitching business ideas to investors and shareholders, and teaching with real-life entrepreneurs.

Some of the suggested teaching methods for this theme are person-induced business simulation (Klapper & Tegtmeier, Citation2010), incubators (Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008), internships to create and implement innovative products for real clients (Wang & Verzat, Citation2011), and live projects where students collaborate with real business people (Chang & Rieple, Citation2013). While this theme depends heavily on experiential learning and learning by doing, which correlate to entrepreneurial learning suggestions for EE programmes’ best practice, fewer articles discuss the teaching methods explored in this theme (22 out of 97).

A unique example of learning “through” entrepreneurship is a programme in Sweden, where PhD science researchers with inventions are linked with undergraduate entrepreneurship students to create a company that produces the invention. Students start by searching the customers’ needs to make the invention more suitable to the market, building a partnership and applying for seed funding. All of these steps are supported by mentors working for the university’s incubator, and at the end of each project, all students become shareholders in the company (Lundqvist & Williams Middleton, Citation2013).

This Swedish programme is an actual business experience for students, but it did receive a €6 million eight-year grant and plans to gain the commitment of students for five or six years. Hence, the implementation of such programmes will heavily depend on the resources available for the institution and timetable constraints (Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008). Part of the reason for describing this programme as unique is that it was one of the few detailed programmes that educated the students with a programme design that can be considered as a “through entrepreneurship” EE programme. Also, the programme is more of an apprenticeship and less in the classroom, which is suggested by Aronsson and Birch (Citation2004) as the best way to educate students to become entrepreneurs.

Generally, regarding the contents of each course curriculum, very few of the 97 articles discussed these in detail. Of those that did, Liebenberg and Mathews (Citation2012) explained what topics for each lecture were provided in the course, and Vincett and Farlow (Citation2008) even mentioned the teaching material references and books used in the EE programme under study.

For the vast majority of the articles, the curricula contents were mentioned in terms of the course label “name” only. The challenge that arises from this general description of the curricula content is that there is already little consensus about what the words entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial mean in practice (Pittaway & Cope, Citation2007). Hence, mostly the content of the course would vary depending on the teacher’s personal preferences as to definition and scope (Hannon, Citation2006; Sexton & Bowman, Citation1984, p. 21). This level of generic description of curricula contents needs a more elaborate description to enable entrepreneurship educators and curricula designers to access insights from previous experiences (Smith & Paton, Citation2011).

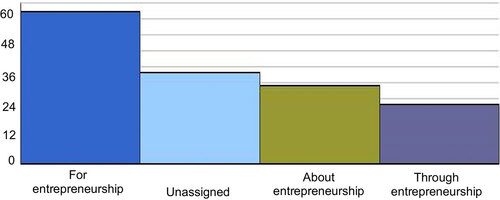

Finally, Figure condenses the number of articles that discussed one or more of the EE curricula content and/or teaching methods mentioned in each of the suggested themes. In general, from the 97 articles discussing EE, we notice that many articles discussed the “what” and “how” of EE programmes, yet mostly in a very general way, while around 34 articles did not discuss curricula content and teaching methods at all.

Figure 1. Number of selected EE articles that discuss one or more course content and teaching methods included in the suggested themes.

Furthermore, Figure shows that most articles discussed the curricula content and teaching methods used in practical-oriented course—“for entrepreneurship” and “through entrepreneurship”—as opposed to theoretical-oriented ones—“about entrepreneurship”. Moreover, while teaching methods used in the teaching “through entrepreneurship” theme correlate the most to entrepreneurial learning suggestions for best practices (i.e. incubators, mentoring and internships), however, these teaching methods were the least discussed in the EE articles (22 out of 97).

4. Conclusion

This paper aimed to contribute to mapping the EE curricula content and teaching methods in the tertiary level. Our conclusion were built upon an extensive SLR for . The result reveals that the common practices of EE programmes’ content and teaching methods could be grouped into three general themes. The first theme excessively uses theoretical content and is a teacher-centred teaching method which is teaching “about” entrepreneurship and aims to increase students’ awareness about entrepreneurship as a career choice (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014). The second and third themes—teaching “for” and “through” entrepreneurship—aim to graduate entrepreneurs and are more learner-centred, and are designed to build entrepreneurial skills rather than only providing content. This happens through either creating an environment where students can imitate real business situations or actually enabling them to start or contribute to venture creation (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2014; Vincett & Farlow, Citation2008).

The process of exploring what do EE curricula provide and how are they taught was challenged by the lack of a clear consensus of the definition of entrepreneurship or what “entrepreneurial” involves in curricula practice (Pittaway & Cope, Citation2007). This caused courses to vary widely and to have little uniformity, limiting the ability to draw any generalisation of what are common or best practices, and opening wide doors for multiple interpretations of the terms entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial (Bennett, Citation2006), and dependence of curricula design and process on the teacher’s experience and preferences (Hannon, Citation2006; Sexton & Bowman, Citation1984, p. 21).

Also, there was a lack of availability of a framework to assess what would be best practice (Fiet, Citation2001) in EE. Moreover, many researchers have underlined a significant lack of studies regarding EE programme outcomes and effectiveness (Honig, Citation2004), where very few articles discuss the output of EE programmes in terms of the actual numbers of graduates who start or grow a business after the programme. This is a question that very few educational institutions were able to answer (Rae, Martin, Antcliff, & Hannon, Citation2012).

Finally, it would be useful if future research could explore many research questions relevant to the EE area, namely what “exactly” do we mean when we use the term “entrepreneurship education” (Pittaway & Cope, Citation2007); what are the detailed contents provided and teaching methods that contribute to achieving the different programmes’ objectives (Smith & Paton, Citation2011); how are the courses that use the label “entrepreneurial” linked in terms of content to the entrepreneurship process (Kuratko, Citation2005); how can the experiential learning programmes be made to be cost-effective (Sullivan, Citation2000); and what results are EE programmes giving in terms of the actual graduates who start or grow a business (Rae et al., Citation2012). Answering these questions might contribute to unfolding the current provision, which will consequently lead to improving provided entrepreneurship programmes (Lee et al., Citation2005).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fatima Sirelkhatim

Fatima Sirelkhatim is an entrepreneur and start-up trainer at Business Growth Centre, graduated with a distinction MSc from Liverpool University. Her main area of interest is entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education.

Yagoub Gangi

Yagoub Gangi is an associate professor of Economics at university of Khartoum, graduated from Manchester Metropolitan University with PhD in Economics. His main research area of interest is entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment.

References

- Aronsson, M., & Birch, D. (2004). Education matters—but does entrepreneurship education? An interview with David Birch. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3, 289–292.10.5465/AMLE.2004.14242224

- Bazeley, P., & Richards, L. (2000). The NVivo qualitative project book. London: Sage.

- Bennett, R. (2006). Business lecturers’ perceptions of the nature of entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 12, 165–188.10.1108/13552550610667440

- Bridge, S., Hegarty, C., & Porter, S. (2010). Rediscovering enterprise: Developing appropriate university entrepreneurship education. Education and Training, 52, 722–734.

- Chang, J., & Rieple, A. (2013). Assessing students’ entrepreneurial skills development in live projects. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20, 225–241.10.1108/14626001311298501

- Cope, J. (2005). Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 373–397.10.1111/etap.2005.29.issue-4

- Cope, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 604–623.10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.06.002

- Cope, J., & Watts, G. (2000). Learning by doing: An exploration of experience, critical incidents and reflection in entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 6, 104–124.10.1108/13552550010346208

- Corbett, A. (2005). Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 29, 473–491.

- Coviello, N., & Jones, M. (2004). Methodological issues in international entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 485–508.10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.06.001

- Dabbagh, N., & Menascé, D. (2006). Student perceptions of engineering entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of Engineering Education, 95, 153–164.10.1002/jee.2006.95.issue-2

- DeTienne, D., & Chandler, G. (2004). Opportunity identification and its role in the entrepreneurial classroom: A pedagogical approach and empirical test. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3, 242–257.10.5465/AMLE.2004.14242103

- Dzisi, S. (2008). Entrepreneurial activities of indigenous African women: A case of Ghana. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 2, 254–264.

- Fayolle, A. (2013). Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 25, 692–701.10.1080/08985626.2013.821318

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2008). From craft to science. Journal of European Industrial Training, 32, 569–593.10.1108/03090590810899838

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 51, 315–328.

- Fiet, J. (2001). The theoretical side of teaching entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 1–24.10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00041-5

- Hannon, P. (2006). Teaching pigeons to dance: Sense and meaning in entrepreneurship education. Education and Training, 48, 296–308.

- Harmeling, S., & Sarasvathy, S. (2013). When contingency is a resource: Educating entrepreneurs in the Balkans, the Bronx, and beyond. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 37, 713–744.

- Heinonen, J., & Poikkijoki, S. (2006). An entrepreneurial-directed approach to entrepreneurship education: Mission impossible? Journal of Management Development, 25, 80–94.

- Honig, B. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: Toward a model of contingency-based business planning. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3, 258–273.10.5465/AMLE.2004.14242112

- Jones, C. (2010). Entrepreneurship education: Revisiting our role and its purpose. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17, 500–513.10.1108/14626001011088697

- Jones, C., & Matlay, H. (2011). Understanding the heterogeneity of entrepreneurship education: Going beyond Gartner. Education and Training, 53, 692–703.

- Katz, J. (2003). The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrepreneurship education. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 283–300.10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00098-8

- Klapper, R., & Tegtmeier, S. (2010). Innovating entrepreneurial pedagogy: Examples from France and Germany. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17, 552–568.10.1108/14626001011088723

- Kuratko, D. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, 577–598.10.1111/etap.2005.29.issue-5

- Lee, S., Chang, D., & Lim, S. (2005). Impact of entrepreneurship education: A comparative study of the US and Korea. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1, 27–43.10.1007/s11365-005-6674-2

- Liebenberg, L., & Mathews, E. (2012). Integrating innovation skills in an introductory engineering design-build course. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 22, 93–113.10.1007/s10798-010-9137-1

- Ligthelm, A. (2007). Survival analysis of small informal businesses in South Africa 2007–2010. Eurasian Business Review, 1, 160–179.

- Lundqvist, M., & Williams Middleton, K. (2013). Academic entrepreneurship revisited—university scientists and venture creation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20, 603–617.10.1108/JSBED-04-2013-0059

- McMullan, W., & Vesper, K. (1987). New ventures and small business innovation for economic growth. R&D Management, 17, 3–13.

- Minniti, M., & Bygrave, W. (2001). A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 25, 5–12.

- Mojica, M. N., Gebremedhin, T. J., & Schaeffer, P. V. (2010). A county-level assessment of entrepreneurship and economic development in Appalachia using simultaneous equations. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15, 3–18.10.1142/S1084946710001452

- Morris, M., Webb, J., Fu, J., & Singhal, S. (2013). A competency-based perspective on entrepreneurship education: Conceptual and empirical insights. Journal of Small Business Management, 51, 352–369.10.1111/jsbm.2013.51.issue-3

- Pacheco, D. F., Dean, T. J., & Payne, D. S. (2010). Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 464–480.10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.07.006

- Pardede, E., & Lyons, J. (2012). Redesigning the assessment of an entrepreneurship course in an information technology degree program: Embedding assessment for learning practices. IEEE Transactions on Education, 55, 566–572.10.1109/TE.2012.2199757

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences. Malden, MA: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470754887

- Piperopoulos, P., & Dimov, D. (2014). Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(2). doi:10.1111/jsbm.12116

- Pittaway, L., & Cope, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. International Small Business Journal, 25, 479–510.10.1177/0266242607080656

- Pittaway, L., & Thorpe, R. (2012). A framework for entrepreneurial learning: A tribute to Jason Cope. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 24, 837–859.10.1080/08985626.2012.694268

- Rae, D., Martin, L., Antcliff, V., & Hannon, P. (2012). Enterprise and entrepreneurship in English higher education: 2010 and beyond. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19, 380–401.

- Ramoglou, S. (2013). Who is a ‘non-entrepreneur’? Taking the ‘others’ of entrepreneurship seriously. International Small Business Journal, 31, 432–453.10.1177/0266242611425838

- Samwel Mwasalwiba, E. (2010). Entrepreneurship education: A review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. Education and Training, 52, 20–47.10.1108/00400911011017663

- Sánchez, J. (2013). The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. Journal of Small Business Management, 51, 447–465.10.1111/jsbm.2013.51.issue-3

- Sexton, D., & Bowman, N. (1984). Entrepreneurship education: Suggestions for increasing effectiveness. Journal of Small Business Management, 22, 18–25.

- Shepherd, D. (2004). Educating entrepreneurship students about emotion and learning from failure. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3, 274–287.10.5465/AMLE.2004.14242217

- Smith, A., & Paton, R. (2011). Delivering enterprise. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 17, 104–118.10.1108/13552551111107534

- Solomon, G. (2007). An examination of entrepreneurship education in the United States. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 14, 168–182.10.1108/14626000710746637

- Sullivan, R. (2000). Entrepreneurial learning and mentoring. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 6, 160–175.10.1108/13552550010346587

- Thorpe, R., Holt, R., Pittaway, L., & Macpherson, A. (2006). Knowledge within small and medium sized firms: A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7, 257–281.

- Vesper, K., & Gartner, W. (1997). Measuring progress in entrepreneurship education. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 403–421.10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00009-8

- Vincett, P., & Farlow, S. (2008). Start-a-business: An experiment in education through entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15, 274–288.

- Wang, Y., & Verzat, C. (2011). Generalist or specific studies for engineering entrepreneurs? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18, 366–383.10.1108/14626001111127124